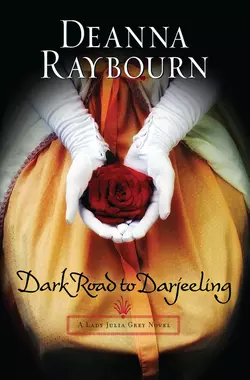

Dark Road to Darjeeling

Deanna Raybourn

After eight idyllic months in the Mediterranean, Lady Julia Grey and her detective husband are ready to put their investigative talents to work once more. At the urging of Julia's eccentric family, they hurry to India to aid an old friend, the newly widowed Jane Cavendish.Living on the Cavendish tea plantation with the remnants of her husband's family, Jane is consumed with the impending birth of her child–and with discovering the truth about her husband's death. Was he murdered for his estate? And if he was, could Jane and her unborn child be next?Amid the lush foothills of the Himalayas, dark deeds are buried and malicious thoughts flourish. The Brisbanes uncover secrets and scandal, illicit affairs and twisted legacies. In this remote and exotic place, exploration is perilous and discovery, deadly. The danger is palpable and, if they are not careful, Julia and Nicholas will not live to celebrate their first anniversary.

Dark Road to Darjeeling

Dark Road to Darjeeling

Deanna Raybourn

www.mirabooks.co.uk (http://www.mirabooks.co.uk)

This book is dedicated to my daughter.

All the best of what I am is because I am your mother.

I have done a thousand dreadful things

As willingly as one would kill a fly,

And nothing grieves me heartily indeed

But that I cannot do ten thousand more.

—Titus Andronicus

William Shakespeare

Contents

The First Chapter

The Second Chapter

The Third Chapter

The Fourth Chapter

The Fifth Chapter

The Sixth Chapter

The Seventh Chapter

The Eighth Chapter

The Ninth Chapter

The Tenth Chapter

The Eleventh Chapter

The Twelfth Chapter

The Thirteenth Chapter

The Fourteenth Chapter

The Fifteenth Chapter

The Sixteenth Chapter

The Seventeenth Chapter

The Eighteenth Chapter

The Nineteenth Chapter

The Twentieth Chapter

The Twenty-First Chapter

The Twenty-Second Chapter

The Twenty-Third Chapter

Acknowledgments

Book Club Questions for Dark Road to Darjeeling

A Conversation with the Author

The First Chapter

Mother, let us imagine we are travelling,

and passing through a strange and dangerous country.

—The Hero

Rabindranath Tagore

Somewhere in the foothills of the Himalayas, 1889

“I thought there would be camels,” I protested. “I thought there would be pink marble palaces and dusty deserts and strings of camels to ride. Instead there is this.” I waved a hand toward the motley collection of bullocks, donkeys, and one rather bored-looking elephant that had carried us from Darjeeling town. I did not look at the river. We were meant to cross it, but one glance had decided me firmly against it.

“I told you it was the Himalayas. It is not my fault the nearest desert is almost a thousand miles away. Do not blame me for your feeble grasp of geography,” my elder sister, Portia, said by way of reproof. She gave a theatrical sigh. “For heaven’s sake, Julia, don’t be difficult. Climb onto the floating buffalo and let’s be off. We are meant to cross this river before nightfall.” Portia folded her arms across her chest and stared at me repressively.

I stood my ground. “Portia, a floating buffalo is hardly a proper mode of transport. Now, I grant you, I did not expect Indian transportation to run to plush carriages and steam trains, but you must own this is a bit primitive by any standards,” I said, pointing with the tip of my parasol to the water’s edge where several rather nasty-looking rafts had been fashioned by means of lashing inflated buffalo hides to odd bits of lumber. The hides looked hideously lifelike, as if the buffalo had merely rolled onto their backs for a bit of slumber, but bloated, and as the wind changed I noticed they gave off a very distinctive and unpleasant smell.

Portia blanched a little at the odour, but stiffened her resolve. “Julia, we are Englishwomen. We are not cowed by a little authentic local flavour.”

I felt my temper rising, the result of too much travel and too much time spent in proximity to my family. “I have just spent the better part of a year exploring the most remote corners of the Mediterranean during my honeymoon. It is not the ‘local flavour’ that concerns me. It is the possibility of death by drowning,” I added, nodding toward the ominous little ripples in the grey-green surface of the broad river.

Our brother Plum, who had been watching the exchange with interest, spoke up with uncharacteristic firmness. “We are crossing the river and we shall do it now, even if I have to put the pair of you on my shoulders and walk across it.” His temper had risen faster than my own, but I could not entirely blame him. He had been ordered by our father, the Earl March, to accompany his sisters to India, and the experience had proven less than pleasant thus far.

Portia’s mouth curved into a smile. “Have you added walking on water to your talents, dearest?” she asked nastily. “I would have thought that beyond the scope of even your prodigious abilities.”

Plum rose to the bait and they began to scrap like a pair of feral cats, much to the amusement of our porters who began to wager quietly upon the outcome.

“Enough!” I cried, stopping my ears with my hands. I had listened to their quarrels since they had run me to ground in Egypt, and I was heartily sick of them both. I summoned my courage and strode to the nearest raft, determined to set an example of English rectitude for my siblings. “Come on then,” I ordered, a touch smugly. “It’s the merest child’s play.”

I turned to look, pleased to see they had left off their silly bickering.

“Julia—” Portia began.

I held up a hand. “No more. Not another word from either of you.”

“But—” Plum started.

I stared him down. “I am quite serious, Plum. You have been behaving like children, the pair of you, and I have had my fill of it. We are all of us above thirty years of age, and there is no call for us to quarrel like spoiled schoolmates. Now, let us get on with this journey like adults, shall we?”

And with that little speech, the raft sank beneath me and I slipped beneath the chilly waters of the river.

Within minutes the porters had fished me out and restored me to dry land where I was both piqued and relieved to find that my little peccadillo had caused my siblings so much mirth they were clasped in each other’s arms, still wiping their eyes.

“I hope you still find it amusing when I die of some dread disease,” I hissed at them, tipping the water from my hat. “Holy Mother Ganges might be a sacred river, but she is also a filthy one and I have seen enough dead bodies floating past to know it is no place for the living.”

“True,” Portia acknowledged, wiping at her eyes. “But this isn’t the Ganges, dearest. It’s the Hooghly.”

Plum let out a snort. “The Hooghly is in Calcutta. This is the Rangeet,” he corrected. “Apparently Julia is not the only one with a tenuous hold on geography.”

Before they could fly at one another again, I gave a decided sneeze and a rather chaotic interlude followed during which the porters hastily built up a fire to ward off a chill and unpacked my trunks to provide me with dry clothing. I gave another hearty sneeze and said a fervent prayer that I had not contracted some virulent plague from my dousing in the river, whichever it might be.

But even as I feared for my health, I lamented the loss of my hat. It was a delicious confection of violet tulle spotted with silk butterflies—entirely impractical even in the early spring sunshine of the foothills of the Himalayas, but wholly beautiful. “It was a present from Brisbane,” I said mournfully as I turned the sodden bits over in my hands.

“I thought we were forbidden from speaking his name,” Portia said, handing me a cup of tea. The porters brewed up quantities of rank, black tea in tremendous cans every time we stopped. After three days of the stuff, I had almost grown to like it.

I took a sip, pulling a face at my sister. “Of course not. It is the merest disagreement. As soon as he joins us from Calcutta, the entire matter will be resolved,” I said, with a great deal more conviction than I felt.

The truth was my honeymoon had ended rather abruptly when my brother and sister arrived upon the doorstep of Shepheard’s Hotel the first week of February. The end of the archaeological season was drawing near, and Brisbane and I had thoroughly enjoyed several dinners with the various expeditions as they passed through Cairo to and from the excavations at Luxor. Brisbane had been to Egypt before, and our most recent foray into detection had left me with a fascination for the place. It had been the last stop on our extended tour of the Mediterranean and therefore had been touched with a sort of melancholy sweetness. We would be returning to England shortly, and I knew we would never again share the sort of intimacy our wedding trip had provided. Brisbane’s practice as a private enquiry agent and my extensive and demanding family would see to that.

But even as we were passing those last bittersweet days in Egypt, I was aware of a new restlessness in my husband, and—if I were honest—in myself. Eight months of travel with only each other, my maid, Morag, and occasional appearances from his valet, Monk, had left us craving diversion. We were neither of us willing to speak of it, but it hovered in the air between us. I saw his hands tighten upon the newspaper throughout the autumn as the killer known as Jack the Ripper terrorised the East End, coming perilously close to my beloved Aunt Hermia’s refuge for reformed prostitutes. I suspected Brisbane would have liked to have turned his hand to the case, but he never said, and I did not ask. Instead we moved on to Turkey to explore the ruins of Troy, and eventually the Whitechapel murders ceased. Brisbane seemed content to make a study of the local fauna whilst I made feeble attempts at watercolours, but more than once I found him deftly unpicking a lock with the slender rods he still carried upon his person at all times. I knew he was keeping his hand in, and I knew also from the occasional murmurs in his sleep that he was not entirely happy with married life.

I did not personally displease him, he made that perfectly apparent through regular and enthusiastic demonstrations of his affections. Rather too enthusiastic, as the proprietor of a hotel in Cyprus had commented huffily. But Brisbane was a man of action, forced to live upon his wits from a tender age, and domesticity was a difficult coat for him to wear.

Truth be told, the fit of it chafed me a bit as well. I was not the sort of wife to darn shirts or bake pies, and, indeed, he had made it quite clear that was not the sort of wife he wanted. But we had been partners in detection in three cases, and without the fillip of danger I found myself growing fretful. As delightful as it had been to have my husband to myself for the better part of a year, and as glorious as it had been to travel extensively, I longed for adventure, for challenge, for the sort of exploits we had enjoyed so thoroughly together in the past.

And just when I had made up my mind to address the issue, my sister and brother had arrived, throwing Shepheard’s into upheaval and demanding we accompany them to India.

To his credit, Brisbane did not even seem surprised to see them when they appeared in the dining room and settled themselves at our table without ceremony. I sighed and turned away from the view. A full moon hung over old Cairo, silvering the minarets that pierced the skyline and casting a gentle glow over the city. It was impossibly romantic—or it had been until Portia and Plum arrived.

“I see you are working on the fish course. No chance of soup then?” Portia asked, helping herself to a bread roll.

I resisted the urge to stab her hand with my fork. I looked to Brisbane, imperturbable and impeccable in his evening clothes of starkest black, and quickly looked away. Even after almost a year of marriage, a feeling of shyness sometimes took me by surprise when I looked at him unawares—a feyness, the Scots would call it, a sense that we had both of us tempted the fates with too much happiness together.

Brisbane summoned the waiter and ordered the full set menu for Portia and for Plum, who had thrown himself into a chair and adopted a scowl. I glanced about the dining room, not at all surprised to find our party had become the subject not just of surreptitious glances but of outright curiosity. We Marches tended to have that effect when we appeared en masse. No doubt some of the guests recognised us—Marches have never been shy of publicity and our eccentricities were well catalogued by both the press and society-watchers—but I suspected the rest were merely intrigued by my siblings’ sartorial elegance. Portia, a beautiful woman with excellent carriage, always dressed cap-apie in a single hue, and had elected to arrive wearing a striking shade of orange, while Plum, whose ensemble is never complete without some touch of purest whimsy, was sporting a waistcoat embroidered with poppies and a cap of violet velvet. My own scarlet evening gown, which had seemed so daring and elegant a moment before, now felt positively demure.

“Why are you here?” I asked the pair of them bluntly. Brisbane had settled back in his chair with the same expression of studied amusement he often wore when confronted with my family. He and Portia enjoyed an excellent relationship built upon genuine, if cautious, affection, but none of my brothers had especially warmed to my husband. Plum in particular could be quite nasty when provoked.

Portia put aside the menu she had been studying and fixed me with a serious look. “We are bound for India, and I want you to come with us, both of you,” she added, hastily collecting Brisbane with her glance.

“India! What on earth—” I broke off. “It’s Jane, isn’t it?” Portia’s former lover had abandoned her the previous spring after several years of comfortably settled domesticity. It had been a blow to Portia, not least because Jane had chosen to marry, explaining that she longed for children of her own and a more conventional life than the one they had led together in London. She had gone to India with her new husband, and we had heard nothing from her since. I had worried for Portia for months afterward. She had grown thinner, her lustrous complexion dimmed. Now she seemed almost brittle, her mannerisms darting and quick as a hummingbird’s.

“It is Jane,” she acknowledged. “I’ve had a letter. She is a widow.”

I took a sip of wine, surprised to find it tasted sour upon my tongue. “Poor Jane! She must be grieved to have lost her husband so quickly after their marriage.”

Portia said nothing for a moment, but bit at her lip. “She is in some sort of trouble,” Brisbane said quietly.

Portia threw him a startled glance. “Not really, unless you consider impending motherhood to be trouble. She is expecting a child, and rather soon, as it happens. She has not had an easy time of it. She is lonely and she has asked me to come.”

Brisbane’s black eyes sharpened. “Is that all?”

The waiter interrupted, bringing soup for Portia and Plum and refilling wineglasses. We waited until he had bustled off to resume our discussion.

“There might be a bit of difficulty with his family,” Portia replied, her jaw set. I knew that look well. It was the one she always wore when she tilted at windmills. Portia had a very old-fashioned and determined sense of justice. If she were a man, one would have called it chivalry.

“If the estate is entailed in the conventional manner, her expectations would upset the inheritance,” Brisbane guessed. “If she produces a girl, the estate would go to her husband’s nearest male relation, but if she bears a son, the child would inherit and until he is old enough to take control, Jane is queen of the castle.”

“That is it precisely,” Portia averred. Her face took on a mulish cast. “Bloody nonsense. A girl could manage that tea plantation as well as any boy. One only has to look at how well Julia and I have managed the estates we inherited from our husbands to see it.”

I bristled. I did not like to be reminded of my first husband. His death had left me with quite a generous financial settlement and had been the cause of my meeting Brisbane, but the marriage had not been altogether happy. His was a ghost I preferred not to raise.

“How is it that she does not already know the disposition of the estate?” Brisbane asked. “Oughtn’t there to have been a reading of the will when her husband died?”

Portia shrugged. “The estate is relatively new, only established by her husband’s grandfather. As the estate passed directly from the grandfather to Jane’s husband, no one thought to look into the particulars. Now that her husband has died, matters are a little murky at present, at least in Jane’s mind. The relevant paperwork is somewhere in Darjeeling or Calcutta and Jane doesn’t like to ask directly. She thinks it might seem grasping, and she seems to think the matter will sort itself out when she has the child.”

I turned to Portia. “I thought her husband was some sort of wastrel who went to India to make his fortune, but you say he has inherited it. Is the family a good one?”

Angry colour touched Portia’s cheeks. “It seems she wanted to spare me any further hurt when she wrote to tell me of her marriage. She neglected to mention that the fellow was Freddie Cavendish.”

I gasped and Brisbane arched a thick black brow interrogatively in my direction. “Freddie Cavendish?”

“A distant—very distant—cousin on our mother’s side. The Cavendishes settled in India ages ago. I believe Mother corresponded with them for some time, and when Freddie came to England to school, he made a point of calling upon Father.”

Plum glanced up from his wine. “Father smelled him for a bounder the moment he crossed the threshold. Once Freddie realised he would get nothing from him, he did not come again. It was something of a scandal when he finished school and refused to return to his family in India. Made a name for himself at the gaming tables,” he added with a touch of malice. Brisbane had been known to take a turn at the tables when his funds were low, usually to the misfortune of his fellow gamblers. My husband was uncommonly lucky at cards.

I hurried to divert any brewing quarrel. “How ever did Jane meet him? He would have left school at least a decade ago.”

“Fifteen years,” Portia corrected. “I used to invite him to dinner from time to time. He could be quite diverting if he was in the proper mood. But I lost touch with him some years back. I presumed he had returned to India until I met him in the street one day. I remember I was giving a supper that evening and I needed to make the numbers, so I invited him. I thought a nice, cosy chat would be just the thing, but a thousand details went wrong that evening, and I had to ask Jane to entertain him for me. They met again a few months later when she went to stay in Portsmouth with her sister. Freddie was a friend to her brother-in-law and they were often together. Within a fortnight they were married and bound for India.”

I cudgeled up whatever details I could recall. “I seem to remember him as quite a handsome boy, with a forelock of dark red hair that always spilled over his brow and loads of charm.”

“As a man grown he was just the same. He could have charmed the garters off the queen’s knees,” Portia added bitterly. “He ended up terribly in debt and when his grandfather fell ill in India, he thought he would go back and take up residence at the tea plantation and make a go of things.”

We fell silent then, and I glanced at Plum. “And how did you come to attach yourself to this expedition?” I asked lightly.

“Attach myself?” His handsome face settled into sulkiness. “Surely you do not imagine I did this willingly? It was Father, of course. He could not let Portia travel out to India alone, so he recalled me from Ireland and ordered me to pack up my sola topee and here I am,” he finished bitterly. He waved the waiter over to refill his wineglass and I made a mental note to keep a keen eye upon his drinking. As I had often observed, a bored Plum was a dangerous Plum, but a drunken one would be even worse.

I returned my attention to my sister. “If Father wanted you to have an escort so badly, why didn’t he come himself? He is always rabbiting on about wanting to travel to exotic places.”

Portia pulled a face. “He would have but he was too busy quarrelling with his hermit.”

I blinked at her and Brisbane snorted, covering it quickly with a cough. “His what?”

“His hermit. He has engaged a hermit. He thought it might be an interesting addition to the garden.”

“Has he gone stark staring mad? Who ever heard of a hermit in Sussex?” I demanded, although I was not entirely surprised. Father loved nothing better than tinkering with his country estate, although his devotion to the place was such that he refused to modernise the Abbey with anything approaching suitable plumbing or electricity.

Portia sipped placidly at her soup. “Oh, no. The hermit isn’t in Sussex. Father has put him in the garden of March House.”

“In London? In the back garden of a townhouse?” I pounced on Plum. “Did no one try to talk him out of it? He’ll be a laughingstock!”

Plum waved an airy hand. “As if that were something new for this family,” he said lightly.

I ignored my husband who was having a difficult time controlling his mirth and turned again to my sister. “Where does the hermit live?”

“Father built him a pretty little hermitage. He could not be expected to live wild,” she added reasonably.

“It isn’t very well wild if it is in the middle of Mayfair, now is it?” I countered, my voice rising. I took a sip of my wine and counted to twenty. “So Father has built this hermitage in the back garden of March House. And installed a hermit. With whom he doesn’t get on.”

“Correct,” Plum said. He reached for my plate and when I offered no resistance, helped himself to the remains of my fish.

“How does one even find a hermit these days? I thought they all became extinct after Capability Brown.”

“He advertised,” Plum said through a mouthful of trout grenobloise. “In the newspaper. Received quite a few responses, actually. Seems many men fancy the life of a hermit—and a few women. But Father settled on this fellow from the Hebrides, Auld Lachy. He thought having a Hebridean hermit would add a bit of glamour to the place.”

“There are no words,” Brisbane murmured.

“They started to quarrel about the hermitage,” Portia elaborated. “Auld Lachy thinks there should be a proper water closet instead of a chamber pot. And he doesn’t fancy a peat fire or a straw bed. He wants good coal and a featherbed.”

“He is a hermit. He is supposed to live on weeds and things he finds in the ground,” I pointed out.

“Well, that is a matter for debate. In fact, he and Father have entered into negotiations, but things were at such a delicate stage, he simply could not leave. And the rest of our brothers are otherwise engaged. Only dearest Plum was sitting idly by,” Portia said with a crocodile’s smile at our brother.

“Sitting idly by?” He shoved the fish aside. “I was painting, as you well know. Masterpieces,” he insisted. “The best work of my career.”

“Then why did you agree to come?” I asked.

“Why did I ever agree to do anything?” he asked bitterly.

“Ah, the purse strings,” I said quietly. It was Father’s favourite method of manipulation. The mathematics of the situation were simple. A wealthy father plus a pack of children with expensive tastes and little money of their own equalled a man who more often than not got his way. It was a curious fact in our family that the five daughters had all achieved some measure of financial independence while the five sons relied almost entirely upon Father for their livelihoods in some fashion or other. They were dilettantes, most of them. Plum dabbled in art, fancying himself a great painter, when in fact, he had only mediocre skill with a brush. But his sketches were very often extraordinary, and he was a gifted sculptor although he seldom finished a sculpture on the grounds that he did not much care for clay as it soiled his clothes.

“If I might recall us to the matter at hand,” Brisbane put in smoothly, “I should like to know more about Jane’s situation. If it were simply a matter of bringing her back to England, you could very well do that between the two of you. You require something more.”

Portia toyed with her soup. “I thought it might be possible for you to do a bit of detective work whilst we are there. I should like to know the disposition of the estate. If Jane is going to require assistance, legal or otherwise, I should like to know it before the moment is at hand. Forewarned is forearmed,” she finished, not quite meeting his eyes.

Brisbane signalled the waiter for more wine and we paused while the game course was carried in with the usual ceremony. Brisbane took a moment to make certain his duck was cooked to his liking before he responded.

“A solicitor could be of better use to you than I,” he pointed out.

“Than we,” I corrected.

Again he raised a brow in my direction, but before we could rise to battle over the question of my involvement in his work, Portia cut in sharply.

“Yes, of course. But I thought it would make such a lovely end to your honeymoon. Jane’s letters are quite rapturous on the beauties of the Peacocks.”

“The Peacocks?” My ears twitched at the sound of it. Already I was being lured by the exoticism of the place, and I suspected my husband was already halfway to India in his imagination.

“The Peacocks is the name of the estate, a tea garden on the border of Sikkim, outside of Darjeeling, right up in the foothills of the Himalayas.”

“The rooftop of the world,” I said quietly. Brisbane flicked his fathomless black gaze to me and I knew we were both thinking the same thing. “Of course we will go, Portia,” I assured her.

Her shoulders sagged a little in relief, and I noticed the lines of care and age beginning to etch themselves upon her face. “We will make arrangements to leave as soon as possible,” I said briskly. “We will go to India and settle the question of the estate, and we will bring Jane home where she belongs.”

But of course, nothing that touches my family is ever so simple.

The Second Chapter

On the seashore of endless worlds children meet.

—On the Seashore

Rabindranath Tagore

It was not until we were almost halfway to India that I manoeuvred enough time alone with Portia to pry the truth from her. Plum was busily occupied sketching a pretty and penniless young miss bound for India to marry an officer, and Brisbane was closeted with the ship’s captain, both of them behaving mysteriously and pretending not to. Portia had evaded me neatly during our preparations for leaving Egypt, but I knew her well enough to know she had not made a clean breast of matters at the dinner table at Shepheard’s, and I meant to winkle the truth from her once and for all.

She settled herself upon the small private deck attached to my cabin where I had lured her with the promise of a luscious tea en famille. She glanced about. “Where are the menfolk?” she asked, her voice touched by the merest shade of anxiety.

“Plum is flattering an affianced bride and Brisbane is very likely doing something which will result in our quarrelling later.”

“I thought we were taking tea together,” she commented, watching me closely.

I narrowed my eyes. “No, we are quite alone.”

She made to rise.

“Sit down, Portia. And tell me everything.”

Portia subsided into the chair and gave a sigh. “I ought to have known you would find me out.”

“I have every right to be furious with you. I know you have intrigued to get us to India under false pretenses, but you might at least have told me why. I presume it does have to do with Jane?”

She nodded. “That much is true, I promise you. And I am worried about the estate. Nothing I told you in Egypt was a lie,” she said, lifting her chin.

“Yes, but I suspect you left out the most important bits,” I protested.

She clamped her lips together, then burst out, “I think Freddie Cavendish was murdered.” She buried her face in her hands and did not look at me.

I swallowed hard against my rising temper and strove to speak gently. “What makes you believe Freddie was murdered?”

She lifted her head, spreading her hands. “I do not know. It is a feeling, nothing more. But Jane’s letters have been so miserable. She felt so wretched after Freddie died, so low that she felt compelled to write to me even though she feared I would not reply.” Her expression softened. “As if I could refuse her anything. After the first few months, she began to feel a little better, but there was always a sadness to her letters, a sort of melancholia I had never seen in her before.”

“Of course she is melancholy,” I burst out in exasperation. “Her husband is dead! She is all alone in a strange land with people whom I suspect would just as soon not see her safely delivered of her child.”

Portia shook her head slowly. “I could not pry too deeply. I did not want to raise fears in her that she might not have, but the more I read, the more troubled I became. She does not feel safe there, nor happy. And if there is a chance that Freddie was murdered, it is most likely he was killed for the inheritance.”

“And if Freddie was killed for the inheritance,” I began.

“Do not say it,” she ordered, her green eyes cold with fear.

“Then his child may be in danger,” I finished. “I think you may ease your mind upon one point. Jane is in no immediate peril.”

She bristled. “How can you possibly know that?”

“Think, dearest. Murder is a tricky business. One tiny detail missed, one vital clue dropped, and it’s the gallows. No, a clever murderer would only strike when absolutely necessary. With Freddie out of the way, there is no need to harm Jane. She might well be carrying a daughter, in which case, whoever meant to put Freddie out of the way need only wait and let time and nature and the law take their proper course. But if the child is a boy, well, killing an infant seems vastly easier than killing a grown person. One need only smother the child in its cradle and everyone would put it to natural causes. Even if the worst has been done and Freddie was murdered, there is no call for any harm to come to Jane. It is only the child, and then only a male child, who might be in danger,” I reassured her.

Portia shook her head slowly. “I cannot be convinced. Let us presume for a moment that Freddie was murdered. What if his killer grows impatient? What you say is logical, but murderers are by nature impetuous. What if he grows tired of waiting and decides to settle matters now? No, Julia, I cannot be at ease about Jane, not until I have seen her for myself. I mean to be on hand when Jane delivers her child, and I mean to protect the pair of them,” she said fiercely.

I put my hand to hers. “And in the meanwhile, you want us to find out what happened to Freddie?”

“If Freddie was not murdered, then Jane and her child will be safe,” she said simply. She hesitated. “There is something more.”

I sighed. “I ought to have known there would be.”

“I do not want Jane distressed. If it has not occurred to her that Freddie might have been murdered, I do not want to put thoughts into her head. You must exercise discretion.”

“So I am to investigate a possible murder without actually revealing it to the widow?” I asked, gaping a little.

“Only until I have had a chance to broach the subject gently with her. Give me a little time to determine her state of mind, and then you may involve her, but not before.”

Portia’s expression had turned mulish, and I knew that look well. I threw up my hands. “Very well. I will be as discreet as I am able until you tell me otherwise.”

Portia nodded in satisfaction. “I knew I could depend upon you, dearest.”

We lapsed into silence then, listening to the slap of the waves against the side of the ship. I gave her a look of reproof. “You might have told us the truth. Brisbane and I still would have come.”

She slanted me a curious glance. “Are you so certain? Brisbane is a husband now. He will have lost all common sense.”

I bridled. “He has not,” I began, but even as I said the words, I wondered. Brisbane had been mightily protective of my involvement in his detective work before our marriage. I had little doubt he would prove more difficult now that I was his wife. “You may be right,” I conceded.

Portia rolled her eyes heavenward. “Of course I am right. I did not even dare to tell Plum the truth, and he is only a brother. A husband cannot be trusted to think clearly in any situation that touches his wife’s safety.”

“That may be, but at some point he will notice we are investigating a murder,” I pointed out waspishly. “He is not entirely devoid of the powers of observation.”

“I should hope not. I depend upon him to join the investigation.”

“When did you intend to present him with the real reason for our being in India?”

Portia nibbled her lower lip. “When we have arrived in Calcutta,” she said decisively. “It will be far too late for him to do anything about it at that point.”

Our arrival in the colourful port of Calcutta ought to have been the highlight of our voyage. In fact, it had been ruined by the prickling of my guilty conscience. I had thrilled to the exoticism of the place, but even as I stood next to my husband at the railing of the ship watching the city draw ever closer, I had been consumed with remorse at not telling him what Portia was about as soon as she had made her confession to me. Calcutta smelled of flowers and woodsmoke, and above it all the air simmered with spices, but to me it would always be soured by the bitterness of my own regret.

Of course, Brisbane had done nothing to ease those feelings once I had revealed all to him. Fearing his reaction, I had waited until several days after our arrival in Calcutta to unburden myself, and to my astonishment, his only response had been, “I know.” Where or how he had divined our true purpose, I could not imagine. I only knew I felt monumentally worse. We did not speak of it again, but a slight froideur sprang up between us, imperceptible to others, but almost palpable to us. In company little seemed to have changed. Brisbane was courteous to a fault, and I exerted myself to be charming and winsome. It was only when we were alone that the cracks told. Once the door closed behind us, we said little, and it was only when we put out the light that harmony was once more restored, for our demonstrations of marital affections continued on as satisfying as ever. In fact, though I blush to admit it, they tended to be somewhat more satisfying on account of Brisbane’s mood. His irritation with me prompted him to defer some of the usual preliminaries and proceed with even greater vigour and demand. I do not know if he intended to put me off with his insistent attentions, but he seemed content at my response. Perhaps our concord reassured him—as it did me—that this was simply a short run of troubled waters we should pass safely over in time. I did not like to be at odds with him, and I did not believe he enjoyed our disagreement any more than I, but I promised myself everything would be set to rights when we reached the Peacocks. Brisbane loved nothing so much as a good mystery to sink his teeth into, and I loved nothing so much as Brisbane.

“What do you mean you are not going?” I demanded of Brisbane. It was the last evening of our stay in Calcutta and our suite was in a state of advanced disarray. Morag had left off packing for our departure to help ready us for a farewell dinner being given in our honour. “Brisbane, you must go. I know the viceroy is a terrible bore, but surely you can think of something to say to him,” I urged. “He’s quite keen on irrigation works. Ask him about that and you won’t have to say another word the whole of the evening.”

I peered at the gown Morag was holding out for my inspection. “No, we are quite late enough. There is no time to heat the pressing irons,” I said, waving away the creased peacock-blue silk. “My pink will suffice.”

She pursed her lips and jerked her head towards the bathroom door. “The master’s bath is ready,” she intoned solemnly.

I puffed out a sigh of impatience. “Morag, I have told you before, there is no need to refer to him as the master. It is positively feudal.”

“I rather like it,” Brisbane put in.

Morag gave him a nod of satisfaction. “You’ll want your shoes shined,” she told him. “The hotel valet’s made a pig’s breakfast of it, and no master of mine will go about in dirty shoes. I will see to that at once.”

“Very well, Morag,” Brisbane said kindly.

I cleared my throat. “Yes, very well, Morag, but do you think you might manage to help me dress? You are actually my maid, you know. Mr. Brisbane does have the hotel valet to assist him.”

Morag sniffed. “Foreign devils. As if they knew how to take care of a proper Scottish gentleman. I shall have to find the pink. Keep your wig on,” she finished saucily.

She left, banging the door behind her, and I turned to Brisbane. “She was impossible enough before you came along. Now she is thoroughly unmanageable. I ought to let you take her on as valet and find a new lady’s maid for myself,” I added in some irritation.

Brisbane said nothing, but began to divest himself of his clothing. I gave him a broad smile. “I am glad you changed your mind about coming tonight,” I told him.

“I haven’t,” he said, dropping his coat. The waistcoat and neckcloth followed swiftly and he began to work his way out of his collar and cuffs. “When I said I was not going, I was not referring to dinner with the viceroy, although you are quite right, as it happens. The fellow has a positive mania for drains. And railways,” he added, dropping his shirt onto the growing pile.

With perfect immodesty, he began to disrobe his lower half and I let my gaze slide to the clothes upon the floor. Even after so many months of marriage, I was still somewhat shy about such things. Of course, I had spent the first few weeks of our honeymoon simply staring, but it had finally occurred to me that this was impolite and I had made a devoted effort to afford him some measure of privacy, although he seemed thoroughly unconcerned. I put it down to his Gypsy blood. In my experience, Gypsies could be quite casual about nudity.

Brisbane, now completely unclothed, went into the bathroom and flung himself into the tub with a great slosh. He was something of a sybarite, and I had discovered that although he could be remarkably relaxed about domestic arrangements in general, he insisted upon a scalding hot bath before dinner, an activity we sometimes shared with vastly interesting results. But there would be no such goings-on afoot this evening. I followed him, tightening the sash of my dressing gown.

“Then perhaps you will be good enough to clarify. If you are content to dine with the viceroy, then where precisely are you not going?” I asked.

Brisbane took up a washcloth and cake of soap and began to scrub vigorously. “I am not leaving Calcutta,” he said.

The sight of his broad, muscular chest was a diverting one, and it took a moment for the words to register completely. I blinked at him. “I beg your pardon?”

He stopped soaping himself and fixed me with that implacable black stare. “I. Am. Not. Leaving. Calcutta.”

“Yes, I did hear you the first time,” I said with exaggerated politeness. “But it makes no sense. We are supposed to depart for Darjeeling tomorrow,” I protested. “The arrangements have been made.”

“Without my knowledge,” he pointed out.

I felt a thorn-prick of guilt and thrust it aside. I ought not to have waited until almost the end of our sojourn in Calcutta to explain about Portia’s suspicions, but it had never occurred to me that he might simply refuse to oblige us. “What am I supposed to tell Jane? The Cavendishes are expecting us.”

Brisbane curled a lip. “The domestic arrangements of your hostess are not my foremost concern.”

“Pray, what is your foremost concern?” I demanded.

“That my wife and her sister think they can twitch the puppet strings and make me dance to their tune,” he replied. His tone was light, but there was a hard gleam in his black eyes that I did not like.

“I have apologised for that,” I replied evenly. “I myself did not know of Portia’s plans until well after Aden. What was I supposed to do then? I could not very well confess the truth to you and demand to be let off at the next port. Calcutta was the next port.”

“You might have trusted me enough to tell me the truth as soon as you learned of it,” he said in a reasonable tone that lashed my conscience.

I considered for a moment, then drew the sharpest weapon in my arsenal. “I understand you are put out with me,” I began. He curled his lip again and I ignored it. “But I should like to remind you that you have not always been forthright yourself.”

He stopped scrubbing and speculation dawned in his eyes. “You know,” he said flatly, and—I thought smugly—with a trace of admiration.

“Yes, I do know you apprehended a jewel thief on board the ship. I know the captain consulted you and requested your help and I know you unmasked the culprit at considerable personal risk. I understand the fellow was armed with an Italian stiletto dagger,” I finished.

“As it happens, it was Japanese,” he corrected.

“Near enough,” I retorted. “But none of those facts were related to me by you.”

He had the grace to look a trifle less adamant than he had a moment before. “I was in no real danger,” he said finally, his expression softening. He thrust a hand through his long black hair, tousling the hair damply and causing a wet lock to drop over his brow. “And if I were, it is my lot. You cannot protect me.”

“And you cannot protect me,” I returned. I went to him and sat upon the edge of the bathtub, putting a hand to his cheek, just touching the crescent moon scar that rode high upon one cheekbone. “I know you wish to wrap me in cotton wool and leave me on the highest shelf when you go off adventuring, but that simply will not do. I mean to be your partner in every sense of the word.”

He rose from the steaming water and wrapped his arms about me, wetting me as he kissed me thoroughly. I put my arms about his neck, happy that he understood.

He pressed his lips to my cheeks, my eyelids, grazed them over the curve of my ear. And whispered firmly, “No.”

I jumped back. “What do you mean, ‘no’? You cannot just dismiss me out of hand.”

“And neither will I recklessly expose you to danger. You are my wife. It is my place to protect you.” He stepped from the bath and strode across the marble floor to reach for a towel, rubbing himself briskly. His sleek black head disappeared into the folds of the towel, but I kept up my part of the conversation, no easy thing with the view he presented me. It was a testament to my state of mind that I scarcely noticed the long, hard stretch of the muscles of his thighs.

“Good God, Brisbane, is that what we have become? Conventional? Normal? Is that what you want from me, an ordinary marriage to an ordinary wife? I thought my boldness was what drew you to me!”

He dropped the towel so that just his eyes showed above it. “To be precise, it is among your most attractive and most maddening qualities,” he said.

“You cannot expect me to sit quietly at the fireside whilst you see the world,” I told him, hating the pleading note that had crept into my voice.

He dropped the towel and wrapped it about his waist, securing it low upon his hips. “I have given you the world these last months, have I not?”

“A honeymoon is not the same. Your work is the greatest part of who you are, and if you will not share that with me, then you have locked me away from what is most important.”

“You do not understand,” he began.

I broke in, my voice harsh. “No, I do not. And I cannot. It seems the cruelest trick to offer me marriage under pretenses you knew were false.” I regretted the words as soon as I had uttered them, but of course I could not call them back. They had flown at him, and I had only to look at his face to see they had flown true and pierced him.

“Do you regret marrying me?” His voice was deadly calm. If he had raged at me, I would have been at my ease. But this cool detachment was a mood I had seen once or twice before and I knew to be wary of it. He could not be touched when he was in the grip of one. He was polished and hard as an ebony chess king, implacable and immovable.

“Of course not,” I said, deliberately gentling my tone. “You know the depth of my feeling for you. But I also esteem what I become when I am with you, when we are working, hand in hand. And you seem determined never again to let that happen.”

“And you are determined to press the matter until I do,” he countered. It was astonishing to me that he could stand before me wearing nothing but a bath towel and yet preserve as much dignity as if he’d been draped in a judge’s robes. But then Brisbane wore anything well, I reflected.

I gave him a rueful smile. “You know me well enough to know that.”

“Then we are at an impasse,” he observed.

“And you will not leave Calcutta?” I asked one last time.

“Not now,” he said gravely. “I have business here.”

I gaped at him. “Business? What manner of business? I know nothing of this.”

“As it happens, the viceroy has invited me to join a hunting party he is putting together. He is heading out after tigers. There is a man-eater preying upon a village near Simla. It promises to be excellent sport.”

My mouth gaped farther still, and I shut it with a decisive snap. “You do not hunt,” I said after I had recovered myself.

He lifted one heavy shoulder in a careless shrug. “People do change.”

“Not you!” I cried. “It is one of the things I depend upon.”

His expression did not alter, but I smelled something of savagery in him just then. “You will have your secrets, Julia. You must leave me mine. I will see you soon enough, I promise you that. And so we will leave it.”

Even then I could have mended it. I could have conceded his concerns for my safety and his outrage at my sister’s manipulations, his sudden need for convention and normalcy. I could have trimmed myself to fit the mould of a proper wife. It would have taken but a phrase, gently spoken, and a smile, sweetly offered. But I had been such a wife once before, and I had vowed never again.

So I did not offer him either the gentle phrase or the sweet smile. I merely turned on my heel and left him then, closing the door firmly behind me.

And so I set my gaze toward Darjeeling and left with my sister and brother, my maid, Morag, and a party of porters that would have put Stanley’s expedition to shame.

“Is it absolutely necessary to travel with so many men?” I demanded of Portia. “It looks as if we mean to claim Darjeeling in the name of the March family and establish a colony of our own. For heaven’s sake, Portia, the porters are laughing at us.”

Portia shrugged. “They’re being paid well enough to carry Buckingham Palace on their backs if we ordered it.” I continued to needle her about the size of our party, but she did not rise to the bait. She knew Brisbane and I had quarrelled over the investigation and that her methods had been at the centre of our disagreement. Nothing more need be said upon the matter, at least not yet. Once my anger had burnt itself to cinders, no doubt I would have need of her sisterly bosom for a good weep, but for the present, I was content to embark upon the adventure we had set ourselves. I could not worry over Brisbane, I told myself sternly. He had sent his trunks with us as he required only a small bag on his trip, and I held on to the sight of those trunks as proof I would see him again soon. Besides, I reflected, there was quite enough to do just to navigate into the foothills of the Himalayas with an increasingly bitter Plum on our hands. As it happened, he had taken Portia’s manipulations no better than Brisbane had, and it had only been her pointed threats to dispatch a telegram to Father that had persuaded him to continue on with us.

Our unwieldy party left Calcutta behind and began to wind its way slowly up the road to Darjeeling. We might have boarded the train, but Portia had taken one look at the tiny railway and stated flatly that she would not put a foot onto such a toy. Plum grumbled exceedingly at the extra time and trouble it required to travel by road, but in the end I was glad of it, for the air grew thinner and colder outside of Darjeeling, and the scenery changed as we wound our way ever upward. The first high peaks of the Himalayas hove into view, and I nearly fell from my horse when I saw at last the great snow-capped peaks of Kanchenjunga. It was the most beautiful, most majestic sight I had ever seen, and everything I had ever known before paled in comparison to that one extraordinary horizon.

We lingered a number of days in Darjeeling town organising the rest of our journey before pressing on, passing through villages and skirting tea plantations and falling into rivers. The children were plump and friendly, and I noticed their parents were very unlike the Indians of Calcutta, for here the native folk were much shorter and with a coppery cast of complexion and broad, flat cheekbones. Portia, who had armed herself with every bit of information she could find upon the area, informed me that the people of Sikkim blended Bengali Indian with Tibetan and Nepalese, and that the language was a peculiar patois of Hindustani liberally laced with the mountain tongues. The result was a nearly indecipherable but pleasant-sounding language that rose and fell with a musical lilt.

“Yes, but are we actually in Sikkim?” I asked.

Portia wrinkled up her nose and pored over the map. “I think we may actually have crossed into Nepal.”

“Nepal? Are you delirious?” Plum demanded. “We are still in Darjeeling district.”

I peered over Portia’s shoulder. “I think we might have crossed into Sikkim, just there,” I pointed.

“You have the map upside down. That is Madagascar,” Plum said nastily.

“We could ask a porter,” I ventured.

“We cannot ask a porter,” Portia hissed, “any more than we can ask the Cavendishes. It would be rude and impossibly stupid of us not to know where we are. Besides, so long as the porters know, that is all that needs be said upon the matter.”

The one point we did agree upon was the beauty of our surroundings, wherever they might be. The landscape seemed to have taken what was best from many places and combined it to great effect, for I saw familiar trees and plants—ferns and roses and elms—and mingling with them the exotic blooms of orchids and towering, fragrant deodars. Here and there a cluster of native bungalows gave way to neat English cottages, sitting like curiosities among the orderly undulations of the tea fields. And over it all hovered the scent of the tea plants, rising above the serried rows to perfume the air. It was captivating, and more than once Plum very nearly walked off the side of a mountain because he was busily sketching scenes in his notebook.

At last, a few days’ ride out of Darjeeling town—possibly in Sikkim, although possibly not—we crested a small mountain and looked down into as pretty and tidy a valley as I had ever seen. A small river debouched into a lake thick with lilies and water hyacinths at the mouth of the valley, and the only means of entrance was by way of a narrow stone bridge that seemed to beckon us forward.

The head porter said something in his broken English to Portia and she nodded to me. “This is it. It is called the Valley of Eden, and just there,” she said, pointing with her crop, “that cluster of low buildings. That is the Peacocks.” Her voice shook a little, and I realised she must have been nervous at seeing Jane again. She had loved her so devotedly, and to be cast aside was no small thing to Portia. Yet though she was a prodigious holder of grudges, she would have travelled a hundred times as far to help her beloved Jane. But now, hovering on the edge of the precipice, she must have felt the awkwardness of it keenly, and I offered her a reassuring smile.

“It is time, Portia.” I spurred my mount and led the way down the winding path into the Valley of Eden.

Portia need not have worried. Before we had even ridden into the front court, the main doors of the plantation house had been thrown back upon their hinges and Jane, moving as quickly as her condition would permit, fairly flew down the steps.

Portia dismounted and threw her reins to me, gathering Jane into her arms and holding her tightly. Plum and I looked away until Portia stepped back and Jane turned to us.

“Oh, and, Julia, you as well!” I dismounted and offered her another embrace, although not so ferocious as that of my sister, and after a moment I ceded my place to Plum. We had all of us been fond of Jane, and not just for the happiness she had brought to our sister.

Several minutes of confusion followed as the porters unlashed our trunks and sorted what was to be carried inside and what could be taken directly to the lumber rooms and stored, and through it all, Jane beamed at Portia. Anyone who knew her only a little would think her happiness undimmed, but I knew better. There were lines at her mouth and eyes that matched my sister’s, and a new quickness to her motions spoke of anxiety she could not still.

“We have already had tea,” she said apologetically, “but if you would like to rest and wash now, I will have something brought to your rooms and you can meet the family at dinner. They are engaged at present, but they are very keen to meet you.” She showed us to our rooms then, scarcely giving us a chance to remark upon the elegance of the house itself. As we had seen from the road, it was low, only two floors, but wide, with broad verandahs stretching the length of both storeys. Staircases inside and out offered easy ingress, and windows from floor to ceiling could be opened for fresh air and spectacular views of the tea garden and the mountains beyond. I had not expected so gracious a home in so remote a spot, but the house was lovely indeed and I was curious about its history.

I was given a pretty suite upstairs with a dressing room, and it was quickly decided that Morag should sleep there. Morag sniffed when she saw the narrow bed, but she said nothing, which told me she was far more exhausted than I had realised. I felt a stab of guilt when I thought of Morag, no longer a young woman, toiling up the mountain roads, clutching the mane of her donkey and muttering Gaelic imprecations under her breath.

“I do hope you will be comfortable here, Morag,” I said by way of conciliation.

She fixed me with a gimlet eye. “And I hope you will enjoy living out your life here, my lady. There is nothing on earth that would induce me to undertake that journey again.”

And as she unpacked my things with a decidedly permanent air, I realised she meant it.

I lay for some time upon my bed, intending to rest, but assaulted by questions. I rose at length and took up a little notebook, scribbling down the restless thoughts that demanded consideration. First, there was the matter of the estate. I wanted to make certain that the dispositions of Freddie’s legacy were as we suspected. It was impossible to determine if the tea garden was profitable, but the house itself spoke eloquently upon the point of prosperity and perhaps there was a private income attached to the estate as well. If nothing else, the land itself must be worth a great deal and many have been killed for less. Establishing the parameters of the inheritance would go some distance towards establishing a motive, I decided.

Second, I considered the dramatis personae. Who lived at the Peacocks and what had been their relationships with Freddie Cavendish? Were they characterised by pleasantry? Or something darker? I thought of all the possible personal motives for murder—betrayal, revenge, jealousy—and was momentarily discouraged. I had not met Freddie Cavendish for years and already I could imagine a dozen reasons for wanting him dead. This would never do.

I applied myself to thinking logically, as Brisbane would have done, and returned to the question of establishing the players and the question of money. The rest would have to wait, I decided firmly. I put aside my notebook and lifted the bell to ring for Morag. As I did so, I heard the rise and fall of voices, soft murmurs through the wall. I crept close, pressing my ear against it.

“Nothing,” I muttered, cursing the thick whitewashed plaster. I tiptoed to the bedside table and took up a water glass and returned to my listening post. I could hear a little better now, two voices, both feminine, and as I listened, I made out Portia’s distinctive laugh and Jane’s low tones. They were together then, I decided with satisfaction. Whatever had been broken between them could still be mended. And whatever Jane’s fears, she had the Marches at her side to battle her foes.

In spite of Morag’s incessant grumbling about the lack of space in the little dressing room, she managed to unearth my peony-pink evening gown again and the pink pearl bracelets I wore with it. The bracelets were set with unusual emerald clasps and the effect was one of burgeoning springtime, blossoms springing forth from lush green leaves. I left my room feeling rather pretty, particularly after Plum met me on the stairs to give me his arm and look me over with approval.

“A lovely colour. There is the merest undertone of grey to save it from sweetness,” he remarked. I forbore from remarking on the sweetness of his own ensemble, for his taffeta waistcoat was primrose, embroidered with a daisy chain of white marguerites.

He escorted me in to the drawing room where the rest of the household had gathered, and as we entered, Portia looked pointedly at the clock. I ignored her as Jane came forward, a little ungainly with her newly-enhanced figure, but still lovely in her own unique way. She had always favoured loose smocks, and now she wore them to better advantage, a dozen necklaces of rough beads looped about her neck and her dark red hair flowing unbound over her shoulders.

“Julia, you must allow me to introduce you. This is Freddie’s aunt, Miss Cavendish,” she said, indicating the somewhat elderly lady who had risen to shake my hand. Her grip was firm and her palm calloused, and I realised that in spite of her iron-grey hair, Miss Cavendish was something of a force of nature. She had a tall, athletic figure without a hint of a stoop, and I fancied her sharp blue eyes missed nothing. She was dressed in severely plain, almost nunlike fashion in an ancient gown of rusty black, and at her belt hung a chatelaine, the keys of the estate literally at her fingertips.

“How do you do, Miss Cavendish, although I am reminded we are kinswomen, are we not?”

“We have just been discussing the connection,” Portia put in, and I could see from her expression that the conversation had not been entirely pleasant.

“Indeed,” said Miss Cavendish stoutly. “Always said it was a mistake for Charlotte to marry your father. A nice enough man, to be sure, but classes shouldn’t mix, I always say, and Charlotte was gentry. Besides, the March bloodline is suspect, I am sure you will agree.”

I struggled to formulate a reply that was both pleasant and truthful, but before I could manage it, a voice rang out behind me.

“I for one am very pleased to own the connection.” I turned to find a personable young man standing in the doorway, smiling slightly. He extended his hand. “We do not stand upon ceremony here. I am Harry Cavendish, Freddie’s cousin, and yours, however distant. Welcome to the Peacocks.”

I took his hand. Like his aunt’s it was calloused, which spoke of hard work, but he was dressed like a gentleman and I noticed his vowels were properly obedient.

“Mr. Cavendish. I am Lady Julia Gr—Brisbane,” I corrected hastily. After nine months, I was still not entirely accustomed to my new name. “My sister, Lady Bettiscombe, and my brother, Eglamour March.”

He shook their hands in turn, and I noticed his aunt’s gaze resting upon him speculatively.

“Are you missing someone?” Miss Cavendish asked suddenly. “Seems like there ought to be another. I thought Jane said to expect four.”

A moment of awkward silence before I collected myself. “My husband. I am afraid he was detained in Calcutta at the viceroy’s request,” I explained hastily.

Just then a native man, a butler of sorts I imagined, appeared with a tiny gong, and I blessed the interruption. He was dressed in a costume of purest white from his collarless coat to his felt-soled slippers, with an elaborately-wound turban to match. He wore no ornamentation save a pair of heavy gold earrings. He was quite tall for a native of this region, for he stood just over Plum’s height of six feet, and his cadaverous frame seemed to make him taller still. His profile was striking, with a noble nose and deeply hooded black eyes which surveyed the company coolly.

With a theatrical gesture, he lifted his arm and struck the little gong. “Dinner is served,” he intoned, bowing deeply.

He withdrew at once, and Portia and Plum and I stared after this extraordinary creature.

“That is Jolly,” said Miss Cavendish, pursing her mouth a little. “I have told him such dramatics are not necessary, but he will insist. Now, we are too many ladies, so I am afraid each of you gentlemen shall have to take two of us in to dinner.”

I was surprised that the customs should be so formal in so distant a place—indeed, it seemed rather silly that we must process in so stately a fashion into the dining chamber, but I took Mr. Cavendish’s left arm and kept my eyes firmly averted from Portia’s. I knew one look at her was all that would be required to send us both into gales of laughter. Fatigue often had that effect upon us, and I was exhausted from the journey.

But all thoughts of fatigue fled as soon as I stepped into the dining room.

“Astonishing,” I breathed.

Beside me, Harry Cavendish smiled, a genuine smile with real warmth in it. “It is extraordinary, isn’t it? My grandfather always kept pet peacocks, and he commissioned this chamber in honour of them. It is the room for which the house was named,” he explained. The entire room was a soft peacock blue, the walls upholstered in thin, supple leather, the floors and ceiling stencilled and painted. Upon the ceiling, gold scallops had been traced to suggest overlapping feathers, and upon the walls themselves were painted pairs of enormous gilded birds. Most were occupied with flirtation or courtship it seemed, but one pair, perched just over the fireplace, were engaged in a battle, their tails fully opened and their claws glinting ominously. Each eye had been set with a jewel—or perhaps a piece of coloured glass—and the effect was beautiful, if slightly malevolent. A collection of blue-and-white porcelain dotted the room in carefully fitted gilded alcoves, and provided a place for the eye to rest. It was a magnificent room, and I murmured so to Harry Cavendish.

“Magnificent to be sure, but I have always found it a bit much,” he confessed, and even as I smiled in response, I saw Miss Cavendish draw herself upright, her stays creaking.

“This room was my father’s pride and joy,” she said sharply. “He had it commissioned when he married my mother, as a wedding present to her. It is the jewel of the valley, and folk are mindful of the honour of an invitation to dine within its walls.”

Before I could form words, Harry Cavendish cut in smoothly. “And well they ought, Aunt Camellia. But even you must admit the artist meant us to fear that fellow just there,” he said, nodding toward the largest of the peacocks, whose great ruby eye seemed to follow me as I took my chair. “Just look at the nobility of his profile,” Harry went on. “He is a fellow to be reckoned with. Just as Grandfather Fitz was.”

At this mention of her father, Miss Cavendish seemed mollified. She gave Harry a brisk nod of approval. “That he was. He carved this plantation from the wilderness,” she informed the rest of us. “There was nothing here save a ruined Buddhist temple high upon the ridge. No planters, no village, nothing as far as the eye could see to the base of Kanchenjunga itself. A new Eden,” she told us, her eyes gleaming. “It was my father who named this place, for he said so must have the earth itself appeared to Adam and Eve.”

She left off then to ring for Jolly and dinner was served. To my astonishment, there was not a single course, not a single dish, to speak to our surroundings. We might have been dining in a rectory in Reading for all the exoticism at that table. The food was correctly, rigidly English, from the starter of mushrooms on toast to the stodgy bread pudding. It had been cooked with skill, to be sure, but it lacked the flavour I had come to appreciate during my long months of travel. I had learnt to love oily fishes and pasta and olives and any number of spicy things on my adventures, and I had forgot how cheerless British cooking could be.

Harry gave me a conspiratorial nod. “It is deliberately bland because we must preserve our palates for tasting the tea. There are bowls of condiments if you require actual flavour in your food,” he added. I spooned a hearty helping of chutney upon my portion to find it helped immeasurably.

Over dinner, Miss Cavendish related to us the disposition of the valley.

“We are the only real planters in the valley,” she said proudly. “There is a small tea garden at the Bower, but nothing to what we have here. Theirs is a very small concern,” she added dismissively. “Almost the whole of the valley is entirely within the estate, and we employ all of the pickers hereabouts. Doubtless you will see them along the road, although I will warn you they can be importunate. Do not give them anything.”

Portia bristled. “Surely that is a matter best left to one’s own conscience,” she said as politely as she could manage.

“It is not,” Miss Cavendish returned roundly. “With all due courtesy, Lady Bettiscombe, you do not have to live amongst them. Our policies towards the local people have been developed over the course of many decades, and we cling to them because they work. Money is of no use to them for there is nothing to buy.” She warmed to her theme. “There have been planters, English planters, who have been foolish enough to meddle with the ways of the mountain folk. When it has gone awry, they have found themselves without pickers. The natives simply vanished, passing on to the next valley and leaving them with a crop and no one to pick it. They have failed and lost everything because of one moment of misguided compassion,” she said sternly. “That will not happen at the Peacocks.”

I noticed Jane said little, simply picking at her food. I wondered if she felt poorly, or if her nerves had simply gotten the better of her, and I was as relieved for her sake as mine when the meal was over, signalled by Jolly ringing his gong and announcing, “Dinner is finished.”

We rose and Miss Cavendish turned to us. “We keep planters’ hours here, I am afraid. We seldom engage in evening entertainments, and you are doubtless tired from your journey. We will say good-night.”

Upon this point we were entirely agreed, and the party broke up, each of us making our way upstairs with a single candle, shielded with a glass lamp against sudden draughts. A sharp wind had risen in the evening, and the house creaked and moaned in the shadows and every few minutes, a piercing shriek rent the night. “Peacocks,” I reassured myself, but I shivered as I made my way to my room where Morag was sitting, wide-eyed upon the edge of the bed.

“Devils,” she muttered.

“Nonsense. The place was named for peacocks. Doubtless there are still some about. They put up a terrible fuss, but they will not hurt you.”

She fixed me with a sceptical eye and I knew capitulation was my only hope if I expected to sleep.

I sighed. “Very well. You may sleep in here tonight,” I told her. If I had expected her to make up a sleeping pallet at the hearth, I was sadly mistaken, for no sooner had she helped me out of my gown and locked away my jewels than she dropped her shoes to the floor and climbed into the great bed, taking the side closest to the fire.

I sighed again and took the other, colder side, burrowing into the covers and pulling my pillow over my head. Sleep did not come easily, perhaps from the heaviness of the meal. But I lay for some time in the dark, thinking of everything I had seen and heard and listening to Morag’s snores. At last, I fell into a deep and restless sleep. I dreamed of Brisbane.

The Third Chapter

Thou hast made me known to friends whom I knew not.

Thou hast given me seats in homes not my own.

Thou hast brought the distant near and made a brother of the stranger.

—Old and New

Rabindranath Tagore

The next morning dawned bright and cool, the mountain air sweeping down from the snowy peaks and scouring away all my heaviness of the night before. I opened the shutters to see the sun shimmering opal-pink against the flank of Kanchenjunga, and Miss Cavendish below in her garden, a trug looped over one arm, a pair of sharp secateurs in the other hand. She was pruning, making things neat and tidy, and if the garden was an example of her handiwork, she was expert. I had not noticed on our arrival, but the grounds were rather extensive, lushly planted with English cottage flowers in the first flush of spring. She kept their exuberance reined in with a firm hand, but the effect was one of refreshment, and I fancied the garden would provide an excellent spot for reflection during my investigation.

And for conversation, I decided, spying Harry Cavendish just emerging from a pair of garden doors opposite the wing where I was lodged. He looked up and caught sight of me. His mouth curved into a smile, and he waved his hat by way of greeting. I lifted a hand and scurried back into my room. Married ladies did not hang from windows in their night attire to wave at bachelors, I told myself severely. Particularly when their husbands were not at hand.

A tea tray had been left at the door and in short order I was washed and dressed and ready for the day, determined to make some headway in my investigation. I wanted a tête-à-tête with Jane, but when I made my way to the breakfast room, she was not in evidence.

“I heard Aunt Camellia say Jane had a bad night,” Harry explained as he helped himself to eggs and kidneys from the sideboard. “She is still abed and Lady Bettiscombe is breakfasting with her.” If I was disappointed at missing the chance to speak with Jane, it occurred to me that Harry Cavendish might prove a worthwhile substitute. I likewise helped myself to the hot dishes on the sideboard and took a seat at the table. Jolly appeared at my elbow with a pot of tea and a rack of crisp toast, and when he departed, I turned to Harry Cavendish.

“Have you lived here all your life, Mr. Cavendish?”

He nodded. “Almost. My father was Fitzhugh Cavendish’s youngest son, Patrick.”

I smiled at him. “A bit of Irish blood in the family, is there?”

He returned the smile, and I thought of the string of heart-broken young ladies he might have left behind had he ever travelled to London. “Grandfather Fitz’s mother was an Irish lass from Donegal. He was named for her family, and he carried the Irish on to the next generation. His eldest son was Conor, then came Aunt Camellia, then my father, Patrick.”

“Surely Camellia is not an Irish name,” I put in, helping myself to a slice of toast from the rack.

“No, Grandfather Fitz had a bit of the poet about him, no doubt a relic of his Irish blood. He called her Camellia after the plant upon which he meant to build his fortune—the camellia sinensis. Tea,” he explained, lifting his cup.

“What a charming thought,” I said, even as I reflected to myself that anyone less flowerlike would be difficult to imagine.

“Yes, well.” His lips twitched as if he was suppressing the same thought. “Uncle Conor married and Freddie came along shortly after. Then Uncle Conor and his wife were killed in a railway accident in Calcutta.”

“How dreadful! Was Freddie very old?”

Harry Cavendish shrugged. “Still in skirts. He had no memory of them. Grandfather Fitz fetched him here to be brought up, the same as he did for me when my parents died.” A faint smile touched his mouth. “Nothing so dramatic as a railway accident, I’m afraid. An outbreak of cholera. Within the span of two years, Grandfather Fitz had two orphaned grandsons to bring up. If Aunt Camellia ever had the opportunity to marry, she gave it up to stay at the Peacocks and keep matters in hand.”

“A noble sacrifice,” I observed.

Harry pitched his voice lower. “If you promise not to repeat it, I will tell you I think she has been quite contented with her lot as a spinster. She has ruled this particular roost with a very firm hand. She had the sole running of the tea garden for a few years when Grandfather Fitz began to fail.”

“When Freddie was still in England?”

“Yes. They sent him to school at fifteen and he made up his mind not to come home again.”

“I remember. He called upon my father,” I commented, deftly omitting Father’s response to his visit. “But surely fifteen was rather late to leave it. Oughtn’t he have been sent much earlier?”

“Oh, yes, most folk here send their boys back home at age six or seven for schooling. Freddie made do with Grandfather Fitz’s library and the odd bit of tutoring here and there.”

He pressed his lips together again, and suddenly I became more interested in what he was not saying.

“And you never went home to England?”

“Never. My home is here,” he said simply. “I am a planter. Tea is all I know and all I care to know. Aunt Camellia left the place in my hands when she went to England to fetch Freddie home. It was the happiest time of my life,” he said, his tone touched with something more than wistfulness.

“When was that?” I spoke softly. He seemed to be slipping into a reverie, and I had watched Brisbane question enough people to know that in such a state all a subject requires is the gentlest nudge to reveal rather more than he might have preferred.

“Two years past. Freddie was in trouble—gambling, I am afraid. Aunt Camellia had almost persuaded Grandfather Fitz to cut him off entirely, but he was still the heir. Aunt Camellia hoped he would learn to love the business if he were brought home and made to apply himself. So she went to England to persuade him to return with her. She failed. She returned home without him, and it took only a little more persuasion to convince Grandfather Fitz to withdraw Freddie’s allowance until he had proven himself worthy of the inheritance. Grandfather Fitz issued an ultimatum. Freddie was to marry and return to India as soon as possible if he held any hope of inheriting the estate.”

“That is why he married Jane so hastily,” I murmured.

Emotions warred upon his face. “I confess, I did not think them well suited,” Harry Cavendish said. “I like Jane—immensely. But she is so different from what Freddie was. There is something fine about Jane.”

“Yes, that’s it precisely. She is simple and plain and good. Like water or earth,” I agreed.

“That is why I am glad you have come, you and Lady Bettiscombe, particularly. A lady should have the comfort of old friends about her at such a time.” Whether he meant during her widowhood or confinement, I could not say, but it was a pretty sentiment either way.

The conversation turned—rather naturally, I supposed—to tea then, and the coming harvest. The picking was very likely going to commence in a day or two, and I could see from his rising excitement that tea did indeed flow through his veins. But as we spoke, I sensed again an undercurrent of melancholy in him. It was nothing I could have pointed out to another, no peculiarity of manner or speech, but it was there, hovering just behind his eyes, some fear or sense of loss. And as I listened to him enthuse about the harvest, I wondered precisely how far this charming young man would go to become master of the land he loved.

After breakfast I excused myself to the garden where I found Miss Cavendish still busily decapitating plants. She was dressed in a curious fashion, her costume cobbled together from bits of native dress, traditional English garments, and a pair of gentlemen’s riding breeches. It was a thoroughly strange, but eminently practical ensemble, I supposed, and when she bent, I noticed her chatelaine still jangled but there was no telltale creak of whalebone. She had forgone the corset, and I envied her.

The garden itself was a glory, neatly planned and beautifully maintained. At the heart of it was a pretty arbour covered in climbing roses just about to bud. As lovely as it was in spring, I could imagine how enchanting it would be in full summer, with the heavy blossoms lending their lush fragrance to the air as velvety petals spangled the seat below.

“You must be quite proud,” I told Miss Cavendish. “Have you a gardener as well to help with the heavy labour?”

“Half a dozen,” she answered roundly. “It is a planters’ obligation to give employment to as many folk as possible, like young Naresh there,” she added with a nod toward a youth who had just come into the garden pushing a barrow. He responded to his name with a broad smile, and I was startled to see how handsome he was. One does not expect a young Adonis to appear in the guise of a gardener’s boy. He was tall for his age, perhaps sixteen or seventeen and very nearly six feet tall, and his features were regular, with a wide smile and a shock of sleek black hair. He looked like a young rajah, and as we regarded him, he gave us an exaggerated, courtly bow before he departed.