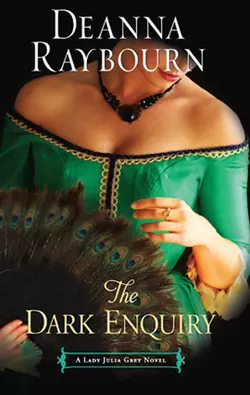

The Dark Enquiry

Deanna Raybourn

Partners now in marriage and in trade, Lady Julia and Nicholas Brisbane have finally returned from abroad to set up housekeeping in London. But merging their respective collections of gadgets, pets and servants leaves little room for the harried newlyweds themselves, let alone Brisbane's private enquiry business.Among the more unlikely clients: Julia's very proper brother, Lord Bellmont, who swears Brisbane to secrecy about his case. Not about to be left out of anything concerning her beloved–if eccentric–family, spirited Julia soon picks up the trail of the investigation.It leads to the exclusive Ghost Club, where the alluring Madame Séraphine holds evening séances…and not a few powerful gentlemen in thrall. From this eerie enclave unfolds a lurid tangle of dark deeds, whose tendrils crush reputations and throttle trust.Shocked to find their investigation spun into salacious newspaper headlines, bristling at the tension it causes between them, the Brisbanes find they must unite or fall. For Bellmont's sakeâ € " and moreâ € " they'll face myriad dangers born of dark secrets, the kind men kill to keep….

The DARK ENQUIRY

The Dark Enquiry

Deanna Raybourn

www.mirabooks.co.uk (http://www.mirabooks.co.uk)

To Pam, agent, friend, and fairy godmother. Thank you.

CONTENTS

THE FIRST CHAPTER

THE SECOND CHAPTER

THE THIRD CHAPTER

THE FOURTH CHAPTER

THE FIFTH CHAPTER

THE SIXTH CHAPTER

THE SEVENTH CHAPTER

THE EIGHTH CHAPTER

THE NINTH CHAPTER

THE TENTH CHAPTER

THE ELEVENTH CHAPTER

THE TWELFTH CHAPTER

THE THIRTEENTH CHAPTER

THE FOURTEENTH CHAPTER

THE FIFTEENTH CHAPTER

THE SIXTEENTH CHAPTER

THE SEVENTEENTH CHAPTER

THE EIGHTEENTH CHAPTER

THE NINETEENTH CHAPTER

THE TWENTIETH CHAPTER

THE TWENTY-FIRST CHAPTER

THE TWENTY-SECOND CHAPTER

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

QUESTIONS FOR DISCUSSION

The FIRST CHAPTER

I will sit as quiet as a lamb.

—King John

London, September 1889

“Julia, what in the name of God is that terrible stench? It smells as if you have taken to keeping farm animals in here,” my brother, Plum, complained. He drew a silk handkerchief from his pocket and held it to his nose. His eyes watered above the primrose silk as he gave a dramatic cough.

I swallowed hard, fighting back my own cough and ignoring my streaming eyes. “It is manure,” I conceded, turning back to my beakers and burners. I had just reached a crucial point in my experiment when Plum had interrupted me. The table before me was spread with various flasks and bottles, and an old copy of the Quarterly Journal of Science lay open at my elbow. My hair was pinned tightly up, and I was swathed from shoulders to ankles in a heavy canvas apron.

“What possible reason could you have for bringing manure into Brisbane’s consulting rooms?” he demanded, his voice slightly muffled by the handkerchief. I flicked him a glance. With the primrose silk swathing the lower half of his face he resembled a rather dashing if unconvincing highwayman.

“I am continuing the experiment I began last month,” I explained. “I have decided the fault lay with the saltpeter. It was impure, so I have decided to refine my own.”

His green eyes widened and he choked off another cough. “Not the black powder again! Julia, you promised Brisbane.”

The mention of my husband’s name did nothing to dissuade me. After months of debating the subject, we had agreed that I could participate in his private enquiry investigations so long as I mastered certain essential skills necessary to the profession. A proficiency with firearms was numbered among them.

“I promised him only that I would not touch his howdah pistol until he instructed me in the proper use of it,” I reminded Plum. I saw Plum glance anxiously at the tiger-skin rug stretched on the floor. Brisbane had felled the creature with one shot of the enormous howdah pistol, saving my life and killing the man-eater in as quick and humane a fashion as possible. My own experiences with the weapon had been far less successful. The south window was still boarded up from where I had shattered it when an improperly cured batch of powder had accidentally detonated. The neighbour directly across Chapel Street had threatened legal action until Brisbane had smoothed his ruffled feathers with a case of rather excellent Bordeaux.

Plum gave a sigh, puffing out the handkerchief. “What precisely are you attempting this time?”

I hesitated. Plum and I had both taken a role in Brisbane’s professional affairs, but there were matters we did not discuss by tacit arrangement, and the villain we had encountered in the Himalayas was seldom spoken of. I had watched the fellow disappear in a puff of smoke and the experience had been singularly astonishing. I had been impressed enough to want some of the stuff for myself, but despite numerous enquiries, I had been unsuccessful in locating a source for it. Thwarted, I had decided to make my own.

“I am attempting to replicate a powder I saw in India,” I temporised. “If I am successful, the powder will require no flame. It will be sensitive enough to ignite itself upon impact.” Plum’s eyes widened in horror.

“Damnation, Julia, you will blow up the building! And Mrs. Lawson dislikes you quite enough already,” he added, a trifle nastily, I thought.

I bent to my work. “Mrs. Lawson would dislike any wife of Brisbane’s. She had too many years of keeping house for him and preparing his puddings and starching his shirts. Her dislike of me is simple feminine jealousy.”

“Never mind the fact that you have created a thoroughly mephitic atmosphere here,” Plum argued. “Or perhaps it is the fact that you keep blowing out the windows of her house.”

“How you exaggerate! I only cracked the first lot and the smoke damage is scarcely noticeable since the painters have been in. As far as the south window, it is due to arrive tomorrow. Besides, that explosion was hardly my fault. Brisbane did not explain to me that sulphur is quite so volatile.”

“He is a madman,” Plum muttered.

I pierced him with a glance. “Then we are both of us mad, as well. We work with him,” I reminded him. “Why are you here?”

Plum snorted. “A happy welcome from my own sister.”

“We are a family of ten, Plum. A visit from a sibling is hardly a state occasion.”

“You are in a vile mood today. Perhaps I should go and come again when you have sweetened your tongue.”

I carefully measured out a few grains of my newly formulated black powder. “Or perhaps you should simply tell me why you are here.”

He gave another sigh. “I need to consult with your lord and master about the case he has set me. He wants me to woo the Earl of Mortlake’s daughter with an eye to discovering if she is the culprit in the theft of Lady Mortlake’s emeralds.”

I straightened, intrigued in spite of myself. “That is absurd. Felicity Mortlake is a thoroughly nice girl with no possible motive to stealing her stepmother’s emeralds. I am sure she will be vindicated by your efforts.”

“That may be, but in the meantime, I have to secure for myself an invitation to their country seat to make a pretense of an ardent suitor. This would have been far easier during the season,” he complained.

“Can you put the thing off?” I asked, wiping the powder from my hands with a dampened rag.

“Not likely. The emeralds are still missing, and Brisbane said Mortlake is getting impatient. Nothing has been proved of Felicity, but until his lordship knows something for certain, he cannot be assured of her innocence or guilt. One feels rather sorry for him. Of course, one ought rather to feel sorry for me. Felicity Mortlake detests me,” he said, pulling a woeful face.

I felt a smile tugging at my lips. “Yes, I know.” I remembered well the time she upended a bowl of punch over Plum’s head in a Mayfair ballroom. Not his finest moment, but very possibly hers.

I bent again to my experiment. “The French now have a smokeless gunpowder,” I mused, sulking a little, “and yet I still cannot manage to perfect this wretched stuff.”

Plum edged towards the door. “You do not mean to light that,” he said as I took up a match.

“Naturally. How else will I know if I am successful? You needn’t worry,” I soothed. “I have taken precautions this time,” I added, gesturing towards the heavy apron I had tied over my oldest gown. I had already ruined three rather expensive ensembles with my experiments and had finally accepted the fact that fashion must give way to practicality when scientific method was employed.

“I am not thinking of your clothes,” he protested, his voice rising a little as I struck the match and the phosphorus at the tip flared into life.

“If you are nervous, then wait outside. Brisbane will return shortly,” I said.

“Brisbane has returned now,” came the familiar deep voice from the doorway.

I looked up. “Brisbane!” I cried happily. And dropped the match.

The fact that the resulting explosion broke only one window did nothing to ameliorate my disgrace. Brisbane put out the fire wordlessly—or at least I think it was wordlessly. The explosion had left a distinct ringing in my ears. His mouth may have moved, but I heard nothing of what he might have said until we returned to our home in Brook Street that evening. Brisbane had ordered dinner served upon trays in our bedchamber, and I was glad of it. A long and fragrantly steamy bath had removed most of the traces of soot from my person, and as I approached the table, I realised I was voraciously hungry.

“Ooh! Oysters—and grouse!” I exclaimed, taking a plate from Brisbane. I settled myself happily, and it was some minutes before I noticed Brisbane was not eating.

“Aren’t you hungry, dearest?”

“I had a late luncheon at the club,” he said, but I was not deceived. He plucked a bit of meat from one of the birds and tossed it towards his devoted white lurcher, Rook. For so enormous a dog, he ate daintily, licking every bit of grease from his lips when he was finished with the morsel.

I laid down my fork. “I know you are not angry or you would be shouting still. What troubles you?”

He passed a hand over his eyes, and I felt a flicker of alarm lest one of his terrible migraines be upon him. But when he opened his eyes, they were clear and fathomlessly black and focused intently upon me.

“I simply do not know what to do with you,” he said. For an instant, I felt sorry for him.

“Four explosions in a month’s time are a bit excessive,” I conceded.

“Five,” he corrected. “You forgot the house party at Lord Riverton’s estate.”

“Oh, would you call that an explosion? I should have called it a detonation.” I picked up my fork again. If we were going to retread the same ground in this argument, I might as well enjoy my meal. “The oysters are most excellent. Pity about Cook giving notice in order to live in the country. We shall never find another half so skilled with shellfish.”

Brisbane was not distracted by my domestic chatter. “Regardless. We must do something about your penchant for blowing things up, my lady.”

The fact that Brisbane used my title was an indication of his agitated state of mind. He never used it in conversation, preferring instead to employ little endearments, some of which were calculated to bring a blush to my cheek.

He poured out the wine and took a deep draught of it, then loosened his neckcloth, an act of dinner table impropriety that would have affronted most other wives, but which I strongly encouraged. Brisbane had a very handsome throat.

I applied myself to the grouse again. “It is the same dilemma that always afflicts us,” I pointed out. “I want to be involved in your work. You permit it—against your better judgement—and somehow it all becomes vastly more complicated than you expected. Really, I do not know why it should surprise you anymore.” After four cases together, including unmasking the murderer of my first husband, it seemed ludicrous that Brisbane could ever think our association would be simple.

He sighed deeply. “The difficulty is that I seem entirely unable to persuade you that dangers exist in the world. You are more careless of your personal safety than any woman I have ever met.”

Considering how many times I had directly approached murderers with accusations of their crimes, I could hardly fault Brisbane for thinking me feckless.

I put a hand to his arm. “You understand I do not mean to be difficult, dearest. It is simply a problem of enthusiasm. I find myself caught up in the moment and lose sight of the consequences.”

His witch-black eyes narrowed dangerously. “Then we must find you another enthusiasm.”

I knew that half-lidded look of old, and I crossed my arms over my chest, determined not to permit myself to be seduced from the discussion at hand. Brisbane was adept at luring me out of difficult moods with a demonstration of his marital affections. Afterward, I seldom remembered what we had been discussing, a neat trick which often provided him a tidy way out of a thorny situation. But not this time, I promised myself.

I tore my glance from the expanse of olive-brown throat and met his gaze with my own unyielding one.

“We cannot spend the whole of our marriage having the same argument, although I realise there are one or two issues which remain to be settled,” I conceded.

We had been married some fifteen months, but our honeymoon had been one of long duration. We had returned to London several weeks past. Since then, we had found a house to let and moved many of his possessions from his bachelor rooms in Chapel Street and mine from the tiny country house on my father’s estate in Sussex. We had hired staff, ordered wallpaper, purchased furniture and bored ourselves silly in the process. We wanted work, worthwhile occupation, cases to solve, puzzles to unravel. He had retained his flat in Chapel Street as consulting rooms and space for experiments with an eye to keeping our professional endeavours separate from our private lives, but I was growing restless. He had already tidied away three major cases since our return, and I had been given nothing more engaging to solve than the mystery of why the laundress applied sufficient starch to only five of the seven shirts he sent out.

“But you promised to let me take part in your work,” I reminded him. “I am doing my best to learn as much as I can to make you a good partner.” I hated the pleading note that had crept into my voice. I stifled it with a bit of bread roll as he considered my words.

“I know you have,” he said at length. “No one could have worked harder or with greater enthusiasm,” he conceded, his lips twitching slightly as he held back a smile. “And that is why I think it is time you embarked upon your first investigation.”

“Brisbane!” I shot to my feet, upsetting the little table, and in an instant I was on his lap, showering him with kisses. Rook took advantage of the situation to browse amongst the litter of china and food. He dragged away a grouse to gnaw upon, but I did not scold him. I was far too happy as I pressed my lips to Brisbane’s cheek. “Do you mean it?”

“I do,” he said, somewhat hoarsely. “Plum must pursue the Mortlake girl, and I want you to go with him. You are acquainted with the family. It will seem more natural if you are there. And Lord Mortlake suspects the theft of the emeralds to be a feminine crime. You will be invaluable to Plum as a finder-out of ladies’ secrets.”

I ought to have been thoroughly annoyed with him that he considered me fit only for winkling out backstairs gossip, but I was too happy to care. At last, Brisbane had accepted me as a partner in the fullest sense of the word.

“You will not regret it,” I promised him. “I shall recover the emeralds and unmask the villain for Lord Mortlake.”

“I shall hold you to that,” he murmured, pressing his mouth to the delicate pulse that fluttered at my neck. Dinner was forgot after that, and some time later, as I drifted off to sleep, Brisbane’s heavily muscled arm draped over me, I mused on how successfully we were learning to combine marriage with business. It wanted only a little patience and a little understanding, I told myself smugly. I had proven myself to him, and he had full faith in my abilities to assist in an investigation.

I ought to have known better.

Things had already begun to unravel the next morning. I hurried down to breakfast in high spirits, brimming with plans for my time at the Mortlakes’. I could hardly wait to discuss them with Brisbane over a delectable meal in our pretty breakfast room. With robin’s-egg-blue walls and thick velvet draperies hung at long windows that overlooked the back garden, it made a calm and pleasant room to begin one’s day. Only the enormous cage that housed our raven, Grim, struck an incongruous note, but I was very fond of the fellow, and he in turn was very fond of the titbits I passed along.

I descended to the hall just as our butler emerged from the green baize door separating the kitchens from the rest of the house.

“Good morning, Aquinas.”

“My lady,” he returned with a bow from the neck. Even carrying a rack of toast, he managed a grave dignity.

“How is the hiring coming along? Have you found a replacement for Cook yet?” Aquinas had been with me for years, first as butler at Grey House during my previous marriage, and later as my own personal retainer. My faith in him—and my boredom with domestic arrangements—was immense. I had left the staffing of the new house entirely in his hands, instructing him to use Mrs. Potter’s, one of London’s most fashionable agencies, to supply us. The results had been middling at best.

“I have engaged a replacement for Cook, and she has prepared breakfast,” he informed me with a little moue of distaste at the slightly burnt toast in the rack.

I raised my brows. “I have never known you to bring burnt toast to the table, Aquinas. I gather this is not her first attempt?”

“Fourth,” he said tightly, “and this was by far the best. I did not wish to delay you or Mr. Brisbane by pressing the matter further, but I will speak with her directly breakfast is over. I have also taken the liberty of engaging another chambermaid in light of Mr. Eglamour March’s arrival.”

I went quite still at the mention of my brother. “Mr. Eglamour?” Eglamour was Plum’s Christian name and one that was never used except by the staff and polite society.

“Mr. Brisbane informed me yesterday that Mr. Eglamour March will be taking up residence here shortly. I thought perhaps the Chinese Room would do nicely for him as it has its own dressing room. I also thought the southern light would be quite suitable should he care to pursue his painting.”

Southern light indeed, I thought with pursed lips. As the fourth—and therefore almost entirely useless—son of an earl, Plum had amused himself with art before taking up detection, and privately I thought him quite talented. But neither of those pursuits called for him to live under my roof.

I plucked the toast rack out of Aquinas’ hands. “I will take this in, if you don’t mind. I should like to have word with Mr. Brisbane.”

Aquinas withdrew to fetch the tea and I girded myself for battle. I did not have long to engage. One look at my face when I entered the breakfast room and Brisbane threw up his hands.

“I know. It is not ideal. He did not like to tell you, but Plum has had a falling out with your father.”

A little of the wind ebbed out of my sails then. I put the toast rack onto the table and went to open Grim’s cage. He gave me a polite bob of the head.

“Good morning,” he said in his odd little voice. I returned the greeting, and Grim dropped to the floor to pace the room, peering into corners and making his morning inspection. I broke up a piece of toast for him and put it onto a saucer on the floor before helping myself. I turned to Brisbane. “They have quarrelled over his role in your business, I presume?”

Brisbane nodded. “His lordship does not find the endeavour suitable to one of Plum’s elevated birth,” he said lightly, but I wondered if he felt the sting of Father’s disapproval. It was terribly ungrateful of Father, really. Brisbane had saved his life upon one occasion and the family honour more times than I could count.

“I did warn you he would be difficult,” I murmured. “Particularly just now. Portia says he has been feuding terribly with Auld Lachy.” Father’s quarrels with his hermit had become so heated Homer could have written an epic poem upon the subject. It had not helped matters when I put it to Father that it was an absurd notion to keep one’s hermit in town in the first place. But it was no more than Father ought to have expected. He had hired Auld Lachy from a newspaper advertisement, and as I had reminded him, one ought never to hire a hermit without proper references.

I took up a knife and a piece of toast and began to scrape off the burnt bits. Grim had studiously ignored his. I dolloped a bit of quince jam onto his saucer and he bobbed his head happily. “That’s for me,” he said, before applying himself to tearing into his breakfast. He had none of Rook’s dainty ways when it came to food. I added some jam to my own sad, sooty piece of toast and resumed the theme of the conversation.

“The thing you must remember about Father is that he is the most terrible hypocrite. He reared us all with his Radical ideals, and yet he does not actually believe them, at least not as they apply to his children.”

“He gave his blessing to our union,” Brisbane pointed out calmly.

I gave him a fond smile. “Father doesn’t care overmuch what the girls do so long as we are happy and don’t make too much of a scandal. It is his sons he frets about. Between Bellmont’s turning out Tory and Valerius practicing medicine, he feels the disapppointment of his heirs keenly.”

Poor Father had not had an easy time of it with his sons. For the most part, those who had married had married well, but his eldest and the heir to the earldom—Viscount Bellmont—was a force for the Tories. The youngest, Valerius, had taken up as a consulting physician, and Lysander and Plum dabbled in the arts. Only Benedick who ran the Home Farm at the family seat in Sussex was a source of pride and comfort to him. Father admired Brisbane’s dash and cleverness, but their relationship was a prickly one, with Father blowing hot then cold, and Brisbane always maintaining a courteous—if advisable—distance.

I bit into my toast, chewing thoughtfully. “And I suspect it was your ducal connections that allayed any doubts he might have had. He really is the most frightful snob, the poor darling.”

Brisbane’s elderly great-uncle was the Duke of Aberdour, a connection that served to ameliorate the fact that his mother had been a Gypsy fortune-teller and his father—well, the less said about him, the better.

I went on. “But Father’s disapproval is not the issue at hand. Why is Plum moving in with us? There is the small bedchamber in the consulting rooms in Chapel Street. He can stay there,” I suggested. Grim quorked impatiently for another piece of toast and I obeyed.

Brisbane picked up his newspaper. “I am afraid that won’t do. Monk is using the room at present.”

I sighed at the mention of Monk. Once Brisbane’s tutor and later his batman—a connection I still meant to explore, as neither of them would ever speak of their time in the army—Monk served as Brisbane’s right-hand during investigations. He had taken a liking to me upon our first meeting. Since then, our relationship had been coolly polite. I had supplanted his role as Brisbane’s confidant and I think he felt the loss of their former closeness sharply. It was entirely supposition on my part, for the subject was never discussed, but Monk had made a habit of absenting himself as much as possible and treating me with detached cordiality when our meeting was unavoidable.

Brisbane had an uncanny ability to intuit my thoughts at times. “He will come round,” he said, his voice gentle. I gave him a weak smile.

“I hope so. It is quite lowering enough that Mrs. Lawson has decided to hate me.”

Brisbane did not dispute the point, and I made a mental note to be more discreet during my visits to Chapel Street. I really had made life very difficult for Mrs. Lawson with my experiments, and it would not do to alienate everyone from Brisbane’s bachelor days.

“Well, Aquinas said he will put Plum in the Chinese Room and he has already engaged another maid, so I suppose it is a fait accompli. Although,” I added, brightening, “I do not see why he could not take the attics in Chapel Street.” Upon our return from abroad, we had taken over the floor above Brisbane’s rooms. It was admirable space for storage, but could easily be fitted out for Plum’s comfort, and the place would be far larger than what we could offer him.

“Impossible,” Brisbane said, folding his newspaper with a snap. “I have plans for the attics.”

“But, Brisbane, really—”

He rose and dropped a kiss to the top of my head. “I thought it would make the perfect space for you to pursue photography. In fact, the equipment is due to arrive whilst you are at the Mortlakes’. By the time the case is concluded and you return to town, you will have your own photographic studio complete with darkroom.”

“Brisbane!” I flung my arms about his neck for the second time in as many days. “You astonish me. I have not mentioned photography in weeks.” I had been intrigued by the work of a lady photographer we had met during our last investigation and had longed for a camera of my own. I admired the ease with which it combined both science and art, and with my extensive family I knew I should never lack for subjects or inspiration.

He kissed me firmly. “Yes, well, I knew you would enjoy it, and I think it will prove quite useful during investigations to have our own means of taking photographs. If you have a talent for it, it may well provide you with a part of the business that is entirely your own.”

I was dazzled at the notion of having something that was both useful and completely mine. I could contribute now, really contribute, and I promised myself that I would succeed. I had applied myself diligently to the other subjects Brisbane had set me, but that would be nothing to my study of photography. I would earn my position in the agency, I vowed, and so delirious was I at the prospect, I scarcely listened as he went on.

“There will be workmen about, partitioning off the space for the darkroom and fitting tables and shelves and whatnot, so you will want to keep clear of the place today. When you return from the country, you can make a proper inventory and if there is anything I have missed out, you can order it.”

I said nothing for a moment. I rose to survey the dishes on the sideboard and found them distinctly uninspiring. I took a kidney for Grim, as they were a special treat, but the rest of the dishes did not tempt me. I placed the kidney on Grim’s saucer and clucked to him. He trotted to it and applied himself greedily. I ran a finger down his silky dark head, studying the flash of green in the depths of his black feathers. “When do Plum and I leave for the country, dearest?”

“The Mortlakes are hosting a house party beginning tomorrow. The country house is just in Middlesex. Take the late-afternoon train out of Victoria Station, and you should easily arrive at Mortlake’s estate by teatime. Does that suit?”

I turned back to stare into those guileless, handsome black eyes and smiled widely. “Of course, but if I am to leave tomorrow, I must shop! I will likely be quite late to dinner tonight. And I must call in on Portia before I go.”

He kissed the top of my head again and left, and as he quit the room, I could not help feeling the relief rolling from him in waves. Aquinas entered then with a pot of tea.

“Mr. Brisbane has left then, my lady?”

“He has,” I said, musing quietly. Aquinas puttered for a moment, returning Grim to his cage and tidying up the dishes upon the sideboard.

“The eggs are watery and the porridge was a lump,” I told him. “Give the new cook another day, and if she does not improve, you must return to Mrs. Potter’s and find us another,” I instructed.

“She has already given notice,” he informed me.

“What notice? She only started this morning.”

“She means to leave by luncheon today.”

“She has given us three hours’ notice?”

“It would appear so, my lady.”

I sighed heavily. “What was the trouble with this one?”

“She was frightened of the new stove.”

I suppressed the urge to snort. The stove had been an extravagance, the latest in domestic technology and Brisbane had insisted upon it. He adored gadgetry of any kind, and as soon as he had clapped eyes upon the great rusting monstrosity in the kitchen, he had demanded it be ripped out and replaced with the very newest and most expensive model. The difficulty was that most cooks were an old-fashioned lot and did not care for change. For a woman trained to prepare meals upon a coal or wood fire, cooking upon a gas stove was a terrifying proposition. I flapped a hand at Aquinas. “I will leave it to you to send to Mrs. Potter’s for another. I have much to do today.”

“Very good, my lady.”

I turned my past two conversations with Brisbane over carefully in my mind, then directed Aquinas to find my maid.

“Send Morag to me, would you? I must discuss the packing list with her.”

“For the trip to the country? Very good, my lady.”

“Not at all,” I said, holding up my cup for more tea and baring my teeth in a smile. “I have absolutely no intention of going to the country.”

The SECOND CHAPTER

If it be a man’s work, I’ll do it.

—King Lear

That afternoon, my errands accomplished, I took refuge in my sister Portia’s town house. She gave me tea and brought out her newly adopted daughter for me to see. The infant, Jane, was carried by her very competent Indian nurse who had come from Darjeeling with us, and I greeted Nanny Stone warmly. Of course, her real name was nothing like Stone, but she had been delighted with all things English, and had put off her beautiful silken saris and her lovely Hindi name in favour of a black bombazine gown with a starched pinafore and the appellation of Nanny Stone. She had mastered the fundamentals of English before leaving her native land, but she had applied herself diligently to perfecting it by engaging anyone who would speak to her in lengthy conversations. The result was a curious mixture of interesting grammar and street slang, spoken in her lovely lilting accent.

She had dressed the baby in emerald-green, an inspired choice against the child’s fluffy halo of ginger hair. The baby clutched a coral teething ring in one plump fist and drooled excessively as the nurse held her out.

I returned the smile, albeit with an effort. “I don’t think I will take her just now, Nanny. She seems a bit moist.”

Nanny Stone plucked a handkerchief from her pocket and began to wipe at the child, crooning some soft cradlesong.

“Nanny, I think her gums are paining her again. Perhaps a bit more of the oil of clove?” Portia suggested.

What followed was a painfully dull debate on the merits of oil of clove for a toothache as compared to Nanny’s native remedies, and in the end Nanny prevailed, bearing her charge off to the nursery to apply some mixture of her own devising.

When they had gone, Portia fixed me with a reproachful glance. “She is your goddaughter, Julia. You will have to hold her sometime.”

I clucked my tongue. “I am very well aware she is my goddaughter. If you will recall, I gave her a lovely set of Apostle spoons to mark the occasion. Now, she is a love, Portia, and I am very fond of her, but you must admit, she is a very damp child. There is always something moist about her mouth or her nose or other places,” I added primly. She glowered, and I hurried on. “I am just not terribly comfortable with babies. Perhaps when she is a bit older and I can take her to the shops or the theatre,” I said brightly.

Portia gave me a little push and we settled in to her morning room to discuss my husband’s duplicity.

“You really think he means to get rid of you?” she asked, eyes wide. Portia loved few things in life so much as a good bit of gossip. She curled onto the sofa with her ancient pug, Mr. Pugglesworth, a flatulent old lapdog who ought to have been dead at least five years past.

“For a few days, at least. Plum is entirely capable of managing the Mortlake case on his own,” I added with a meaningful look. Plum was a handsome fellow, and when he exerted himself, the most charming of our brothers. Wooing a young lady, even one as ill-disposed towards him as Lady Felicity Mortlake, would be child’s play to him. “No, Brisbane had some other purpose in putting me out of London. And not just out of London,” I told her, drawing down my brows significantly. “He is trying to keep me away from Chapel Street altogether.”

Portia looked at me reprovingly. “One cannot entirely blame him, dearest. You have attempted to burn down the place on at least three separate occasions.”

“Four,” I corrected, thinking of the previous day. “And I know I could master the self-igniting black powder if I had enough time.”

“But you think Brisbane had another reason for wanting to be rid of you,” she said, leading me gently back to the subject at hand.

“Hmm? Yes. He was quite artful about it, but he most definitely indicated that I should not visit the consulting rooms before I left town.”

“Because there was something there he did not want you to see?” she hazarded.

“Someone,” I corrected. Quickly, I related to her my activities that afternoon. I had stationed myself in a nondescript hackney cab on Park Street with a careful view to anyone who approached the consulting rooms from Park Lane. Some two hours into my watch, I had seen something—someone—most unexpected.

“Bellmont!” Portia cried. Her colour was high and her eyes bright, and I was glad of it. She had suffered the tragic loss of her dearest companion earlier in the year, and the child, Jane, had come to her as a result of this death. Unexpected motherhood and the loss of her beloved had been difficult burdens, and I was happy to see her so peaceful within herself that she could be engaged in my little problems.

“Yes, dearest. And I put it to you, what business could our eldest brother possibly have with my husband?” Bellmont had made his disapproval in the match clear. Brisbane’s livelihood touched too near the bone of being in trade, and Bellmont, while perfectly cordial, had never behaved with anything like true warmth towards my husband. But then, Bellmont was not known to show warmth towards anyone in particular. He adored his wife, Adelaide, but we often snickered in the family that the extent of their physical warmth was a yearly handshake. How they managed to beget a family of six was a question to twist the sharpest wits. He was a creature of politics and propriety, devoted to his own ideals and wildly at odds with the eccentricity for which our family was famed. It was often said that the expression “mad as a March hare” was coined at the antics of our forebears, whose heraldic badge was a hare. Bellmont did everything in his power to distance himself from that reputation.

“Perhaps blood will out,” Portia suggested wickedly. “What if he has got himself a dancing girl and wants Brisbane to destroy the evidence before Adelaide gets word of it!”

I snickered. “Lord Salisbury, more like. Bellmont is far more concerned with the Prime Minister’s opinion than his wife’s.” Since Lord Salisbury’s last rise to power, Bellmont had assumed a significant role in the government, often introducing legislation in the Commons crafted to further his mentor’s policies.

“Oh!” Portia sat up quickly, disturbing the dog. “Hush, Puggy,” she soothed as he gave an irritable growl. “Mummy didn’t mean it.” She turned to me. “Perhaps Virgilia is being pursued by a questionable sort.”

I blinked at the mention of Bellmont’s eldest daughter. “Virgilia came out two years ago. Is she still on the loose? I rather thought Bellmont would have arranged something for her by now.”

“You know Bellmont has a blind spot where she is concerned.” Puggy emitted a foul noise, followed hard by an even fouler odour, but Portia ignored him. “He has grown quite sentimental of late about Gilly. He has been very worried about an attachment she has formed with Lord Fairbrother’s heir. He promised if she made no formal arrangements with the lad, he would consider the match.”

I lifted a brow. “The season ended three months ago. Has he really prevented her from entering into an engagement? I must credit him with greater powers of persuasion than I thought.”

Portia shrugged. “Gilly has always been his favourite, I suspect because she resembles Mother.” I said nothing. Our mother had died in childbed with our youngest brother when I was very small. I did not remember her at all; I carried only the vaguest recollection of the rustle of yellow skirts and the scent of lemon verbena. But Portia remembered more, and sometimes, when she fell silent and brooding, I knew she was thinking of our mother, who had laughed and danced and left us far too soon. As the eldest, Bellmont would have remembered her better than any. He had been almost grown at her death, and I sometimes thought he had felt it most keenly.

“All the more reason for him to forbid the match entirely if he truly objects to the Fairbrother boy. What is wrong with the fellow?”

Portia gave me a little smile. “He is a devoted follower of Mr. Gladstone.” We laughed aloud then to think of our priggish elder brother forced to spend the rest of his natural life with a son-in-law who was entirely committed to the Liberal cause. Bellmont loathed Gladstone, not the least because Sir William had been a frequent visitor to our house during our formative years. Our devoted Aunt Hermia had been so moved by Gladstone’s work with prostitutes that she had formed her own Whitechapel house of reform for teaching ladies of the night the domestic trades. Most of our ladies’ maids had come from her refuge, including my own Morag. I ought to have applied to Aunt Hermia to help me staff my new home, but one reformed prostitute in my employ was quite my limit.

“Poor Bellmont,” I said at last. “Still, I wonder if he would stoop to asking Brisbane to ferret out something unsavoury to keep poor Gilly from an engagement.”

“If there is something unsavoury about the fellow, Bellmont has a right to know it,” Portia pointed out rather primly. I stared at her. Since becoming a mother, her own priggish tendencies, once entirely smothered, were coming occasionally to the fore.

“Yes, but I hope he has not taken it in his head to ask Brisbane to create some fiction of impropriety to prevent the marriage.”

“Would Brisbane do such a thing?”

“Of course not!” I returned hotly. “Brisbane has a greater sense of integrity than any man I have ever known, including any of our family.”

“Then you have nothing to worry about,” she said, her voice honey smooth. Portia was convinced, but I was not. Something about the set of his shoulders as he walked away from Chapel Street told me something was very wrong with our eldest brother. His usual arrogance had been taken down a bit, and the aristocratic set of his chin—quite natural in a man who was heir to an earldom of seven hundred years’ duration—had softened. Was it merely the thought of losing his beloved daughter to a political opponent that gnawed at him? Or did he wrestle with something greater?

I meant to find out. I turned to Portia. “In any event, you must see that it is impossible for me to go away. I have to know what Bellmont is about.”

“Why?” she demanded. She wore a mantle of calm as easily as any Renaissance Madonna, and I suppressed a sigh of impatience at her newfound serenity.

“Because either Bellmont is in trouble or Brisbane is,” I told her with some heat.

“Brisbane? What sort of trouble? And why would he look to Bellmont for aid?”

I spread my hands. “I do not know. But if Brisbane were in some sort of trouble, his first inclination, his very first, would be to see me safely out of the way. You know how annoying he is upon the point of my personal safety.” The issue was one—the only one, in fact—that caused dissension in our marriage, but it was a common refrain. “And once I was safely out of the way, he might well turn to Bellmont. Our brother is superbly connected, one of the most trusted men in government, and he has the ear of the Prime Minister. One snap of the fingers from Lord Salisbury, and whatever trouble Brisbane might have found himself in goes away.” I snapped my fingers for emphasis, rousing Puggy who promptly flatulated again.

“True,” Portia said, somewhat reluctantly. “But I cannot imagine a situation Brisbane couldn’t extricate himself from. The man is as clever and elusive as a cat,” she added, and I knew she meant it as a compliment.

“Yes, but even cats need more than one life,” I reminded her. “And this particular cat now has a partner to look after him.” I took a deep breath and lifted my chin. Whatever difficulty beset my husband, I was determined to see it through by his side, offering whatever aid and succour I could.

I fixed my sister with a deliberate look. “And that is why I have formed a plan…”

I arrived home to find Brisbane busily engaged in a project that required a pair of workmen wearing leather aprons, endless spools of wires and significant alterations to the cupboard under the stairs.

“Brisbane?”

He backed out of the cupboard, shooting his cuffs. “You are rather earlier than I expected. I had hoped to present you with a surprise.”

He gave me a bland smile and I narrowed my eyes in suspicion. I had reason to be cautious of his surprises, I reflected.

“What is this?” I asked, collecting the workmen and their wires with a sweep of my arm.

“A telephone,” Brisbane informed me.

I stared, blinking hard. “A telephone? To what purpose?”

“To the purpose of being able to speak upon it,” he explained with exaggerated patience.

“Yes, but to whom? In order to speak upon the telephone, one must know someone else with a telephone.”

“We do.” He wore an air of satisfaction. “I am having a second one installed in Chapel Street. We shall be able to communicate with the consulting rooms from here and vice versa.”

“We are paying for two telephones?” I asked, sotto voce. I had no wish to quarrel with Brisbane, particularly over money, and most particularly in front of workmen. Still, the expense was staggering. “Whatever would possess you?”

“It will be extremely convenient for my work,” he replied smoothly. “I am surprised you are not more enthusiastic, my dear. I should have thought the notion that we could speak with one another at any time would have appealed to you.”

“Of course it does,” I told him in full sincerity. “I was simply taken by surprise. It does seem a rather complicated enterprise.”

“Not at all,” he assured me. “In fact, Bellmont has had a device for some weeks and says it is quite the most useful invention.”

“Bellmont?” My pulses quickened. “Have you spoken with him recently?”

Brisbane was skilled at cards, and with a gambler’s sense of timing, he did not pause for an instant. He merely lifted one broad shoulder into a shrug. “Not since the last dinner at March House. But Bellmont and I spoke at length about it then. Surely you heard us. And you were supposed to ask your Aunt Hermia to give you the recipe for the persimmon sauce she served with the duck that night. It was particularly good.”

Brisbane’s lie had taken the warmth out of the room. I felt a chill seep into my bones, and when I spoke, it was through lips stiff with cold. “I am afraid I forgot. I will send a message to March House to ask her for it. We will have it when I return from the country,” I added, twisting my lips into a semblance of a smile. “I must see if Morag has finished the packing if I am to leave tomorrow,” I told him, turning towards the stairs.

“Pity Lord Mortlake doesn’t have one of these,” he said, nodding to the device being fixed to the wall. “I would have been able to speak to you even in the country.”

I silently blessed the fact that the expense of telephones had kept most of our acquaintances from their use. The last thing I needed was Brisbane telephoning the Mortlake country house only to find I had never arrived.

I gave him a brilliant, deceitful smile. “A pity indeed, my love.”

The next morning, I dispatched my trunk and Morag to the country with very specific instructions.

“It will never work,” she warned me. “That Lady Mortlake might have less sense than a rabbit, but even she will notice a missing guest.”

“Not if you do precisely as I have ordered,” I retorted. “It is very simple, really. I have already left a note for my brother that I mean to take the early train. He is a late riser, and by the time he reads the note, the early train will have already departed with you and my trunk. When you arrive at the Mortlake house, it will be far earlier than expected. They will be at sixes and sevens,” I continued. “You have only to request my trunk be sent to my room and explain that I had a headache from the train and wished to walk in the garden before I saw anyone.”

Morag was listening closely, the tip of her tongue caught between her teeth. But disapproval lurked at the back of her gaze, and I hurried on. “You will say that my headache has not improved, and you will make my excuses tonight at dinner. I am unwell and wish to see no one as I mean to retire early. I have already written a note of apology to Lady Mortlake, which you will send down when the dinner gong is sounded. It explains that I am dreadfully sorry but I am simply too ill to meet with anyone, and that I am quite certain the fresh country air will revive me by breakfast.”

“And when it doesn’t? What then? Shall I tell them you’ve gone for a walk and fallen in the carp pond?” she asked nastily.

I took her firmly by the elbow. “This is not for me,” I hissed at her. “This is for Mr. Brisbane, of whom I need not remind you, you are inordinately fond.”

I struck a nerve there. Morag, with her common ways and her flinty heart, had formed an attachment to Brisbane. Perhaps it was the shared link of Scottish blood—or perhaps it was simply that he was a very easy man to idolize—but Morag adored him. She insisted upon referring to him as the master and had taken it upon herself to do his mending, as well as my own. I had little doubt she liked him more than she did me, and the disloyalty rankled, but only a bit. The truth was she had been somewhat easier to live with since Brisbane had entered our lives. At least she was now occasionally in a tractable mood.

“Very well,” she said, rubbing at her arm. “I will do it, but only for the master. Still, it is a pretty state of affairs when a lady must lie to her own husband.”

She gave me a look of injured reproof and I pushed her. “Do not be absurd. I am not betraying him. But I fear he may be in trouble, and he will not confide in me. I must discover the truth on my own, and then I will be in a position to help him.”

To my astonishment, tears sprang to her eyes. She dashed them away with the back of her hand and before I could prepare myself, she dropped a kiss to my cheek. “Forgive me, my lady. I ought not to have thought you would ever be disloyal to the master.”

“Disloyal!” I scrubbed at my cheek. “Morag, could you possibly have a lower opinion of me?”

“Well, you did mean to sneak about like a common trollop,” she pointed out. “How was I to know you had no plans to meet a lover?”

She adopted an expression of wounded indignation and would have kissed me again, but I waved her off. “Oh, leave it,” I snapped at her. “I should have thought that after so many years together, you would know me better.”

Morag raised her chin with a sniff. “You’ve no call to be so high and mighty with me, my lady. Many a finer lady than you has been tempted from the path of righteousness.”

I narrowed my eyes at her. “Have you been reading improving tracts again? I told you I will not have Evangelicalism in my house. You are free to practise whatever religion you like, but I will not be preached at like a Sunday mission,” I warned her.

She patted my hand. “I shall pray for you anyway, my lady. I shall ask God to give you a humble heart.”

I suppressed an oath and handed her the note I had prepared for Lady Mortlake. “Take this and do exactly as I have said. I will send further instructions by telegram when I have plotted my next move.”

Morag tucked the note into her sleeve and gave me an exaggerated wink. “I am your man,” she promised. “Where will you be whilst I am pretending to attend you at the Mortlakes’?”

“I shall be staying with Lady Bettiscombe,” I informed her. Portia had agreed to supply me with a bolthole and any other necessities I should require.

“And what shall you give me to ensure I do not relate that information to Mr. Brisbane or Mr. Plum should they ask it of me?”

I squawked at her. “You cannot seriously think you can extort money from me to purchase your silence!”

She gave me a calm, slow-lidded blink. “It might be worth rather a lot to your plans to keep me silent, and I think it is not the job of a lady’s maid to enter into intrigues.”

I smothered a bit of profanity I had learned from Brisbane and rummaged in my reticule. “Five pounds. That is all, and for that, you will persuade everyone—everyone—that I am rusticating in the country.”

I brandished the note in front of her, and her eyes lit with avarice. “Oh, yes, my lady! I will make them all believe it, even if I have to lie to the queen herself,” she promised.

“Good.” She reached for the banknote and I held it just out of reach. At the last moment, I tore it sharply in half and gave one of the halves to her.

“What bloody use is this?” she demanded.

“Do not swear,” I told her. “Aunt Hermia would be most disappointed if I told her you still spoke like a guttersnipe.”

“If you don’t want me to swear, don’t steal my bloody money,” she returned bitterly.

I tucked the other half of the note into my reticule.

“You may have the other half when the task is completed to my satisfaction. If you exchange both halves at the bank, they will give you a crisp new banknote in its place,” I informed her. She brightened.

“I suppose that’s all right then,” she conceded. “Mind you don’t lose the other half.”

“Shall I give it to the Tower guards to look after with the Crown Jewels?” I asked.

She waggled a finger at me. “I shall speak to God about that tongue of yours, as well.”

“Do, Morag, I beg you.”

The THIRD CHAPTER

I had the gift, and arrived at the technique

That called up spirits from the vasty deep…

—“The Witch of Endor” Anthony Hecht

With my maid and my trunk safely dispatched to the country and my web of lies coming along nicely, I took myself off to my sister’s house on foot, approaching through the back garden. I thought to make an unobtrusive entrance, but when I arrived, I found the entire household standing outside, admiring a cow. A man stood at the head, holding its halter and nudging its nose towards a box of hay.

Portia waved me over to where she stood with Jane the Younger and Nanny Stone.

“Isn’t she divine?” Portia crooned.

I sighed. “Yes, she is quite the loveliest baby,” I assured her, although truth be told, she had the rather unformed look of most children that age, and I suspected she would be much handsomer in another year or two.

“Not the baby,” she sniffed. “The cow.”

I turned to where the pretty little Jersey was being brushed as it munched a mouthful of fresh hay. “Yes, delightful. Why, precisely, do you have a cow in London?”

“For the baby, of course. Jane the Younger will require milk in a few months, and I mean to be ready. She cannot have city milk,” she informed me with the lofty air of certainty I had observed in most new mothers. “City milk is poison.”

I said nothing. Portia could be rabid upon the subject of the infant’s health and I had learned the hard way not to offer an opinion on any matter that touched the baby unless it concurred with hers in every particular. In this case, I could not entirely fault her. Adulterated milk had been discovered in some of the best shops, much of it little better than chalky water and full of nasty things. It was difficult to believe that in a city as grand as London we should resort to keeping cows in the garden to feed children, but I suppose the greater evil was that not everyone could afford to do so.

I studied the animal a moment. It was a sound, sturdy-looking beast, with velvety brown eyes and a soft brown coat. It paused occasionally to give a contented moo, and in response, Jane the Younger gurgled.

“Well, congratulations, my dear,” I told her. “You have just acquired the largest pet in the City.”

We both subsided into giggles then, and Portia passed the baby off to Nanny Stone and escorted me to my room for the night. I had brought with me only a carpetbag, but the contents had been carefully selected. Her eyes widened as she watched me extract the garments, a short wig and a set of false whiskers.

“Julia! You cannot possibly go about London dressed like that,” she objected, lifting one garment with her fingertips.

“Leave it be! You will wrinkle it, and I will have you know I am very particular about the state of my collars,” I added with an arch smile.

But Portia refused to see the humour in the situation. “Julia, those are men’s clothes. You cannot wear them.”

“I cannot wear anything else,” I corrected. “If I am to sleuth the streets of London undetected, I can hardly go as myself, nor can I take my carriage. It is recognisable. I must take a hansom at night, and that means I must travel incognita.”

“Is it ‘incognita’ if you are disguised as a boy? Perhaps it should be ‘incognito’?” she wondered aloud.

“Do not be pedantic. I knew this costume would prove useful,” I exulted. “That is why I ordered it made up some weeks ago. I have been waiting for the chance to wear it.”

I had ordered the garments when I had commissioned a new riding habit from Brisbane’s tailor, using an excellent bottle of port as an inducement to his discretion upon the point. He was well-accustomed to ladies ordering their country attire from his establishment, but the request for a city suit and evening costume had thrown him only a little off his mettle. “Ah, for amateur theatricals, no doubt,” he had said with a grave look, and I had smiled widely to convey my agreement.

In a manner of speaking, I was engaging in an amateur theatrical, I told myself. I was certainly pretending to be someone I was not. I had last adopted masculine disguise during my first investigation with Brisbane, and the results had not been entirely satisfactory. But this time, I had ordered the garments cut in a very specific fashion, determined to conceal my feminine form and suggest an altogether more masculine silhouette. And I had taken the precaution of ordering moustaches, a rather slender arrangement fashioned from a lock of my own dark chestnut hair. The moustaches did not match the plain brown wig perfectly, but I was inordinately pleased with the effect, certain that not even Brisbane would be able to penetrate my disguise.

I spent the rest of the day in my room, finding it difficult to settle to anything in particular. I skimmed the newspapers, ate a few chocolates and attempted to read Lady Anne Blunt’s very excellent book, The Bedouin Tribes of the Euphrates. At length, Portia had a tray sent up with dinner, but I found myself far too excited to eat. I rang for the tray to be cleared and applied myself to my disguise. I observed, not for the first time, that gentlemen’s attire was both oddly liberating and strangely constricting. The freedom from corsets was delicious, but I found the tightness of the trousers disconcerting, and when Portia came to pass judgement, she shook her head.

“They are quite fitted,” she pronounced. “You cannot take off the coat at any point, or you will be instantly known for a woman.”

I tugged on the coat. “Better?”

She gestured for me to turn in a slow circle. “Yes, although you must do something about your hands. No one will ever believe those are the hands of a young man.”

I pulled on gloves and took up my hat, striking a pose. “Now?”

Portia pursed her lips. “It will not stand the closest inspection, but since you mean to go out at night, I think it will do. But why did you chose formal evening dress? Surely you do not intend to travel in polite circles?”

I shrugged. “I may have no choice. Everything depends upon where Brisbane is bound. If I am in a plain town suit, I cannot follow, but if I am in evening attire, I might just gain entrée. At worst, I can pretend to be an inebriated young buck on the Town.”

She hesitated. “It seemed a very great joke at first, but I am not at ease. The last time you did this, you took Valerius. Could you not ask one of our brothers to accompany you? Or perhaps Aquinas. He is entirely loyal.”

I nibbled at my lip, catching a few hairs of the moustaches. I plucked them out and wiped them on my trousers. “I cannot ask any of our brothers. They are as peremptory as Brisbane. Although I do wish I had thought of Aquinas,” I admitted. “He would have been the perfect conspirator, but it is too late now. Besides, I am not certain I could afford it,” I added, thinking of the five-pound bribe I had promised Morag.

I tugged the hat lower upon my head and flung a white silk scarf about my neck, just covering my chin. I collected a newspaper in case I grew bored during my surveillance and tipped my hat with a flourish. “Wish me luck.”

Portia linked smallest fingers with me and I was off, slipping out of the house on quiet feet. Too quiet, I reminded myself. Men walked as if they owned the earth, and I should have to walk the same. I slowed my pace, my heels striking hard against the pavement. On the corner, the lamplighter had just scaled his ladder. After a moment’s work, a comforting glow shone from the lamp. I smiled, and the lamplighter touched his cap.

“A cab for you, madam? There’s a hansom just coming now.”

I cursed softly, then called up to him. “What betrayed me?”

He gave me a broad smile. “A gentleman would never smile at a lamplighter. But the effect is not bad. For a moment, you had me quite deceived,” he reassured me.

I sighed and gave him a wave before hailing the hansom. Struck with a sudden inspiration, I adopted a thick French accent to address the driver. It was a point of national pride for Englishmen to consider Frenchmen womanly and effeminate, and it occurred to me that I could manage a far better job of impersonating a Frenchman than an English fellow.

“Where to, me lad?” he asked, but not unkindly. I hesitated. Brisbane could be departing from either our home or the consulting rooms, but I could not be certain which. On a hunch, I called out our home address in Brook Street. Whatever business Brisbane was about, he would most likely have gone home to bathe and dress for the evening and shave for the second time. His beard was far too heavy to permit him to go out for the evening without secondary ablutions.

I jumped lightly into the hansom, beginning to enjoy myself. I instructed the driver that I meant to hire him for the night. He demurred until we settled on an extortionate rate for his services, at which point he was my man. He threw himself into our surveillance with an admirable enthusiasm, holding the hansom at some distance from the house itself, but still near enough I could see the comings and goings. I think he thought me involved in a romantic intrigue, for I heard several mutterings about Continentals and their wicked ways, but I ignored him, preferring to keep a close watch upon my house instead.

And while I watched, I discovered an interesting fact—surveillance was the dullest activity imaginable. I had not been there a quarter of an hour before I was prodding myself awake, but my evening was not in vain. Some half an hour after we arrived, I saw Brisbane emerge, elegantly attired in his customary evening garments of sharp black and white and carrying a black silk scarf. Just as he emerged, another hansom happened by, or perhaps Brisbane had arranged for its arrival, for he stepped directly from the kerb to the carriage without a break in his stride, tucking the scarf over his shirtfront as he moved. I rapped upon the roof of my own carriage to alert the driver, and after a few moments, we followed discreetly behind.

My man was a marvel, for he never permitted Brisbane’s hansom out of his sight, but neither did he draw near enough to bring attention to us. He held the cab at a distance as Brisbane alighted in front of an imposing old house on a respectable if not fashionable street. A lamplighter had been here, as well, and by squinting, I could just make out the sign, marked in imposing letters. The Spirit Club.

There came a low whistle from the hansom driver and I put my head through the trap. “I know. Give me a minute.” I banged the trap back down and sat for a moment, thinking furiously. I knew I had encountered the name of this particular club recently, very recently, in fact. I scrabbled through the newspaper until I found the notice I sought.

The Spirit Club hosts the acclaimed French medium, Madame Séraphine for an indefinite engagement. Ladies may consult with Madame during the Ladies’ Séance held every afternoon at four o’clock. Gentlemen will be welcomed for the evening sessions, held at eight and ten o’clock. Places must be secured by prior arrangement.

I ought to have known. When Spiritualism had become fashionable, several dozen such clubs had sprung up around London like so many toadstools after an autumn rain. Usually they were maintained with a tiny staff and a resident medium to hold sessions for paying clients. Depending upon the talents of the particular medium, the sessions might involve a séance or automatic writing or some other sort of spiritual manifestations. Some clients went purely for the purpose of entertainment, viewing the mediums as little better than fortune-tellers. Others went from desperation, and it was sometimes the most surprising people who turned to Spiritualism to give them comfort or answer their questions. Sometimes perfectly rational men of business became so dependent upon their medium of choice that they refused to stir a step with regard to their investments without the advice of the spirits. Engagements could not be announced, children could not be named, houses could not be purchased until the spirits had been consulted.

For my part, I found the entire notion of Spiritualism baffling. It was not so much that I felt it impossible the spirits could revisit this life as I thought it vastly disappointing they should want to. If the afterlife could promise no greater entertainment than visiting a club of clammy-handed strangers, then what pleasure was there to be had in being dead?

I blessed the instinct that had caused me to kit myself out as a man, but puffed a sigh of irritation when I realised that without prior arrangement, I could hardly expect to gain entrée into the club.

Still, nothing ventured, nothing gained, I told myself brightly, and I dropped to the pavement. I tossed a substantial amount of money to my driver with instructions to wait some distance farther down the street, then made my way to the Spirit Club. There was no sign of Brisbane, and I realised that he had disappeared as I was tearing through the newspaper for information. I had broken the cardinal rule of surveillance and taken my eyes from my subject, I thought with a stab of annoyance. But the Spirit Club was the only likely destination for him, I decided, and taking the bull firmly by the horns, I rang the bell and waited. After a long moment, an impossibly tall, impossibly thin gentleman opened the door. He had a lugubrious face and a sepulchral manner.

“May I help you?” He gave me a forbidding glance, and I knew instinctively that I should have to put on a very good performance indeed to gain entrance to the club.

I coughed and pitched my voice as low as I could as I adopted an air of bonhomie. “Ah, bonsoir, my friend. I come to see the great medium—Madame Séraphine!” I cried in my Continental accent. I swept him a low, theatrical bow.

The lugubrious expression did not flicker. “Have you an appointment?”

“Ah, no, alas! I have only just this day arrived from France, you understand.” I smiled a conspiratorial smile, inviting him to smile with me.

Still, the face remained impassively correct. “Have you a card?”

I felt my heart drop into my throat. How I could have been so stupid as to forget such an essential component of a gentleman’s wardrobe was beyond me. I did not deserve to be a detective, I thought bitterly.

The porter noted my dismay and took a step forward as if to usher me from the premises. But I had come too far to be turned back.

I flung out my arms. “I should have, but the devils at the station, they pick my pockets! My card case, my notecase, these things they take from me!” I cried. “It is a disgrace that they steal from me, the Comte de Roselende, the great-nephew of the Emperor!”

Napoléon III had been deposed for the better part of two decades, but an innate snobbery lurked within most butlers and porters, and I depended upon it. “I am here in England to visit my beloved great-aunt, the Empress Eugénie,” I pressed on. “She lives in Hampshire, you know.”

This much was true. The Empress lived in quiet retirement in Farmborough, and had once taken tea with my father. It was a particularly brilliant stroke of inspiration as it was well-known that the Empress had once hosted the famous medium Daniel Douglas Home who had conjured the spectre of her father. I watched closely, to see if my connections with royalty swayed the porter at all, but he seemed unmoved.

“I am sorry, Monsieur le Comte, but without a prior appointment, I cannot admit you to the Spirit Club,” he intoned sadly. He made to shut the door upon me, but just then a woman appeared, her plain face alight with interest.

“Monsieur le Comte?” she asked, coming forward to put a hand to the porter’s sleeve as she peered closely at me. “You are a Frenchman?”

Her own accent was smoothly modulated, perhaps from long travels out of her native land, for I detected French as her native tongue, but touched with a bit of German and a hint of Russian in her vowels. “Oui, mademoiselle! St. John Malachy LaPlante, the Comte de Roselende, at your service.” I sprang forward to press a kiss to her hand, praying my moustaches would not choose that moment to desert me. But they held fast, and I released the little hand to study the lady herself. She was dressed plainly, and it occurred to me that I had erred grievously in paying her such lavish attentions.

But she merely ducked her head, blushing. “You are very kind,” she murmured in English for the porter’s benefit. “My sister will be very happy to find a place for you.”

“Ah, you are the sister of the great Madame Séraphine!” I proclaimed grandly.

She gave me a shy, gentle smile. “Yes, I am Agathe LeBrun. Please, come in. You will be our special guest. Beekman, let the gentleman pass.”

The porter, Beekman, stepped aside, not entirely pleased at the development. I smiled broadly at him as I passed and followed the kindly Agathe as she conducted me down a dimly lit corridor. She stopped at a closed door and inclined her head. “This is where the gentlemen gather before the séance. Please sign the guestbook and make yourself comfortable. There are cigars and whisky.”

I pretended to shudder and she gave me a look of approbation. “I understand,” she mumured in French. “Whisky is so unsubtle, is it not? I will see if I can find something more palatable for you.”

“You must not exercise yourself on my behalf,” I protested.

She ducked her head again, glancing up at me, a thin line of worry creasing her brow. I put her at somewhat older than my thirty-three years, perhaps half a dozen years my senior, and her plain face would have been more attractive had she not worn an expression of perpetual harassment.

“I wonder if you are troubled, monsieur,” she said softly.

I started, then forced myself to relax as I realised how clever the arrangement was. Doubtless she was meant to extract information from me in the guise of a simple conversation—information that would be conveyed to her sister for use in the séance. The opening gambit was such that could have been used upon anyone at all, and I marvelled at its simplicity.

“It is kind of you to notice,” I murmured back. “Money troubles. It is for this reason that I come to England.”

Her expression sharpened then, and I knew I had said the wrong thing. My entrée had doubtless been because I had neatly dropped the Empress’ name into conversation. The notion that I was rich and well-connected—and therefore could prove valuable to Madame Séraphine—was my only attractiveness. I hastened to reclaim it.

“Of course, I have expectations, excellent expectations,” I confessed. “But I am a little short at present. I would like to know how long I am expected to wait for my hopes to be realised.”

I tried to adopt a suitable expression, but I found it difficult. How did one manage to convey respectable avarice?

It must have worked, for her features relaxed again into faint worry, and she dropped a curtsey. “I understand, monsieur. May I take your hat? Please make yourself comfortable. The séance will begin in a moment.”

I handed over my hat and she gestured towards the door, leaving me to do the honours as she disappeared back down the darkened hall. I took a deep breath and steeled myself before opening the door. By the window stood an older gentleman of rigid posture and decidedly military bearing. His clothes were costly enough, but his shoulders sported a light dusting of white from his unwashed hair, and his chin was imperfectly shaven. He stared out the window at nothing, for the garden was shrouded in blackness, and I suspected he stood there as a stratagem to avoid conversation.

In contrast to him was a second gentleman, who occupied himself with the whisky and a gasogene. He was sleekly polished, with a veneer of good breeding that I suspected was precisely that—a veneer. His lips were thin and cruel and his brow high and sharply modeled. He put me in mind of a bird of prey, and he eyed me dismissively as I entered. The third gentleman looked a bit less certain of himself, a trifle rougher in his dress and decorum, and only he gave me a smile as I entered. He was dressed in an evening suit that I guessed to be second-hand, and his bright ginger hair had been slicked down with a heavy hand.

I nodded politely towards them all and made my way to the guestbook, where I took up the pen and signed with a flourish. Just as I finished the last scrolling vowel of Roselende, the door opened, and I gave a start. For one heart-stilling instant, I thought it was Plum, but instantly I saw my mistake. Like the newcomer, Plum was an elegant fellow, but I daresay if the pair of them had been placed side by side, few eyes would have fallen first upon my brother. They were of a size, both being tall and well-made, and both of them had green eyes and brown hair shading to the exact hue of polished chestnuts. But Plum lacked this fellow’s predatory grace, and there was something resolute about the set of this gentleman’s jaw, as if he seldom gave quarter or asked for it. His eyes flicked briefly around the room, lingering only a fraction longer upon me than the rest of the company. He inclined his head and advanced to where I stood next to the guestbook. I stepped back sharply and held out the pen.

“Thank you,” he murmured in a pleasant drawling baritone. I flicked my eyes to the page as he scrawled his signature with a flourish.

Sir Morgan Fielding. I had heard the name once or twice in society gossip, but I did not know him, and I relaxed a little as I realised he doubtless did not know me, either.

He replaced the pen, and although he did not look at me, he must have been aware of my scrutiny, for his shapely mouth curved into a slow smile, and I felt a blush beginning to creep up my cheeks.

Hastily, I turned away and picked up the latest copy of Punch. I flicked unseeing through the pages, grateful when the door opened to admit another visitor. To my surprise, this one was a woman, thickly veiled and silent. She was dressed in unrelieved black, at least twenty years out of date, and the severity of her costume was a trifle forbidding. She moved well, but it was impossible to place her age. She might have been twenty or forty or anywhere between, for she was slender enough and her step was light. She approached the guestbook, but before she could sign, the door opened again and Agathe LeBrun appeared in the doorway.

“It is time,” she intoned, and to my surprise, I found myself shivering. I wondered briefly where Brisbane was, but I trotted along obediently as Agathe herded us out.

The military gentleman cast a quick look at the veiled lady and grumbled at Agathe. “I thought this was a gentlemen’s only session,” he began.

Agathe shrugged. “Madame makes exceptions when it suits her. This lady has come several times to commune with the spirit of her dead child, and it is not the practise of Madame Séraphine to turn away those in need of her services.”

“Still, I do not like it,” he said, his mouth mulish.

“The lady’s presence means there will be seven at the table. It is a most auspicious number for Madame.”

He opened his mouth to argue, but Agathe turned with a snap of her skirts and beckoned for us to follow. The veiled lady inclined her head towards the military fellow to show she bore him no ill will. He gave a harrumph and strode off behind Agathe. As he passed me, I caught a whiff of old dust and unwashed flesh and wrinkled my nose. The sleek and hawkish gentleman who had stood by the whisky offered the veiled lady his arm and she took it. The rest of us fell in line like a crocodile of children just out of the nursery.

Agathe led us down a long, narrow corridor, off which opened several rooms set aside for various purposes. Small signs directed vistors. Automatic Writing Room. Lecture Hall. Summoning Room. Room of Special Examinations. It all sounded faintly alarming, and instinctively I crept nearer to the fellow in front of me. The ginger-haired young man gave me a sharp look, and I fell back again, muttering an apology in French.

The walls of the corridor were very dark and the lighting almost nonexistent, lending an otherworldly effect. Over it all, I detected the thick floral scent of incense, the smoky fumes of funeral flowers burnt to ash. It did not seem to disturb the others, but I found it increasingly difficult to breathe, and my head grew light and oddly disconnected from my body.

At last, we came to the final door in the corridor, marked Séance, and Agathe stood by to let us enter. As we passed her in turn, she gave each of us a meaningful look. The general was first, and he rummaged in his pockets, producing a bit of money, which he pressed into her palm. She murmured her thanks and the rest of us followed suit. I had no idea what the expected donation might be, so I handed over a guinea as I entered the room, and it must have been acceptable, for Agathe nodded and said softly, “Monsieur le Comte is very generous.”

The chamber was of modest size, the walls hung with black, and illuminated by a single lamp near the door. A heavy round table, also draped in black, stood in the centre of the room, and about it were ranged a series of chairs. The black hangings were velvet, dull and weighty, and the room felt oppressive. More of the thick aroma hung in the air, and a small brazier smoked upon the cold hearth. There were no paintings or decorations of any sort, only the web of unrelieved black, robbing the room of all light and movement, and a single clock upon the mantel. The timepiece was a strange affair of black enamel with a figure of Death looming over the clock’s face and gesturing to it with his scythe. I supposed it was meant to warn us of the fleeting nature of time, but the hands never moved, and I shivered at the ghoulishness of it and turned my attention to the rest of the room.

At the opposite end from the door stood a cupboard of sorts, and I realised with a start that it was a spirit cabinet, a place for manifesting souls that did not rest. It was some seven feet high but quite narrow and only some two or three feet deep. A heavy velvet curtain closed it off from the rest of the room, and I wondered what mysteries it concealed. Would Madame claim it was a portal to the other side, a ghostly no-man’s land of disembodied voices and spirits that could not sleep? I felt a quickening of my pulse, a sudden longing to be quit of the place. But before I could act upon it, we were instructed to take any chairs save the one in the centre, and we seated ourselves quickly. As near as I could tell, the chair in the centre was the same as the rest, but my suspicions had been raised. I took the chair next to it, the ginger-haired man on my other side, whilst the chair opposite mine was taken by the handsome latecomer, Sir Morgan. On either side of him sat the other gentlemen, and the veiled lady took the chair across from that reserved for the medium.

We had been seated only a moment when Agathe appeared again in the doorway, now wearing a black shawl over her plain gown, and proclaimed, “Honoured guests, I present your guide to the spirit world, Madame Séraphine!”