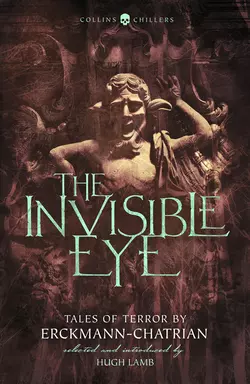

The Invisible Eye: Tales of Terror by Emile Erckmann and Louis Alexandre Chatrian

Hugh Lamb

Emile Erckmann

Louis Chatrian Alexandre

A collection of the finest supernatural tales by two of the best Victorian writers of weird tales – Erckmann–Chatrian, authors who inspired M. R. James, H. P. Lovecraft, and many others.Emile Erckmann and Louis Alexandre Chatrian began their writing partnership in the 1840s and continued working together until the year before Chatrian’s death in 1890. At the height of their powers they were known as ‘the twins’, and their works proved popular translated into English. After their deaths, however, they slipped into obscurity; and apart from the odd tale reprinted in anthologies, their work has remained difficult to find and to appreciate.In The Invisible Eye, veteran horror anthologist Hugh Lamb has collected together the finest weird tales by Erckmann–Chatrian. The world of which they wrote has long since vanished: a world of noblemen and peasants, enchanted castles and mysterious woods, haunted by witches, monsters, curses and spells. It is a world brought to life by the vivid imagination of these authors and praised by successors including M.R. James and H. P. Lovecraft. With an introduction by Hugh Lamb, and in paperback for the first time, this collection will transport the reader to the darkest depths of the nineteenth century: a time when anything could happen – and occasionally did.

Copyright (#u178dcf7c-9018-52e6-8797-b16226043927)

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Collins Chillers edition published 2018

First published in Canada by Ash-Tree Press 2002

Selection, introduction and notes © Hugh Lamb 2018

Cover design by Mike Topping © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Cover photographs © Shutterstock.com (http://www.Shutterstock.com)

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008265380

Ebook Edition © October 2018 ISBN: 9780008265397

Version: 2018-09-06

Dedication (#u178dcf7c-9018-52e6-8797-b16226043927)

To my wonderful family:

Richard and Maggie

My grandson Jack

Andrew, Tamar, Dylan and Ezra

Contents

Cover (#uff59a6de-d9c6-545d-a2e6-7524d4714f4f)

Title Page (#u02737a9a-e146-5def-9361-3d668b97bce5)

Copyright (#u1602ec46-3b74-5aaa-9b7c-133b06fad33a)

Dedication (#u6d6fea29-1fba-522d-b403-4b22bac71581)

Introduction (#u6d856a3b-55a7-5910-96de-438db6ddf4df)

The Invisible Eye (#uad5bf0dd-ab9c-50ee-8a93-e705b27490b5)

The Owl’s Ear (#u3360de06-4da6-5632-b3ac-693d60ab87fe)

The White and the Black (#u9dfa7cf1-cd29-5cec-a064-e274e220a753)

The Burgomaster in Bottle (#ue607afa0-6924-545d-8742-f518d9e540dc)

My Inheritance (#u856f5ce1-50bc-54b7-9eee-87a44981d06b)

The Wild Huntsman (#u45ef9314-9ae4-5e6d-a9e0-02fd99c58cde)

Lex Talionis (#litres_trial_promo)

The Crab Spider (#litres_trial_promo)

The Mysterious Sketch (#litres_trial_promo)

The Three Souls (#litres_trial_promo)

A Legend of Marseilles (#litres_trial_promo)

Cousin Elof’s Dream (#litres_trial_promo)

The Citizen’s Watch (#litres_trial_promo)

The Murderer’s Violin (#litres_trial_promo)

The Child-Stealer (#litres_trial_promo)

The Man-Wolf (#litres_trial_promo)

Sources (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Also in This Series (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

INTRODUCTION (#u178dcf7c-9018-52e6-8797-b16226043927)

It is still uncommon to find the names of Erckmann–Chatrian in studies of Continental literature, a sad reflection on the obscurity suffered by these fine writers for more than a century.

While their main writing efforts – military history and fiction – are now unread and unavailable, their tales of terror have managed to survive in part, even seeing a revival in the early 1970s. The Invisible Eye – the first collection of their stories in Britain since 1981 – will, I hope, introduce more readers to their masterful talent for the macabre.

Emile Erckmann (b. 20 May 1822) and Louis Alexandre Chatrian (b. 18 December 1826) were both natives of Alsace–Lorraine, the border region for so long a bone of contention between France and Germany. Erckmann was born in Phalsbourg, the son of a bookseller, and it is possible that his being surrounded by books from an early age did much to inspire him to his own imaginative works. Chatrian was born in Soldatenthal, the son of a glass-blower. He did not follow his father’s trade, instead becoming a teacher at Phalsbourg college.

It was here that Erckmann met Chatrian, while the former was studying law (a profession he never followed), and the two hit it off very well. It seems that Erckmann was the more literary and imaginative of the two, while Chatrian was of a much more practical and energetic mind. Their writing style seems to have been adapted to this difference between them, with Erckmann writing and Chatrian revising (a working system which was later to produce the most awful trouble).

They started writing together almost immediately, and had the distinction of seeing one of their first efforts, a play on the invasion of Alsace in 1814, banned in 1848 because of its effects on the volatile state of public opinion in the province at the time. They did manage to publish Histoires et Contes Fantastique in 1849, two years after their writing partnership commenced. It was ironic that the first work by the dynamic duo should so neatly sum up their writing career and later obscurity. It was an awful failure, and must have made them wonder if it was all worth the effort. They fared so badly in those early years that, by all accounts, they nearly starved. Thoroughly discouraged, Erckmann resumed his legal studies, and Chatrian took a job in the Eastern Railway Company in France.

It took some time, but they finally cracked the market in 1859 with their novel The Illustrious Doctor Matheus. Four years later, they struck the vein that was to bring them national renown with Madame Therese, a novel about Alsace at the time of the French revolution. They specialised in French history, particularly of the Napoleonic era; a time still alive in the memories of older French citizens, who supplied them with much detail. The books flowed out: Waterloo (1865), La Guerre (1866), Le Blocus (1867), Histoire d’un Paysan (1868) – the list was impressive.

As well as military fiction, they tried their hand at drama, and one result was the interesting Le Juif Polonais, published in English in 1871 as The Polish Jew. This was high drama on the psychological decline of a murderer. It became the stage play The Bells, and gave Sir Henry Irving his most celebrated role. Oddly, it also gave Boris Karloff one of his first horror film roles (five years before Frankenstein) as a hypnotist in the 1926 Chadwick production, directed by James Young from his own screenplay based on the Erckmann–Chatrian work.

Their most interesting book, Contes Fantastiques (not to be confused with their first collection), appeared in 1860. It contains some of their finest tales of terror (several of which are included here), and remains their best work in the genre.

The pair were known as ‘the twins’ at the height of their fame. According to one source, they worked out the plots of their stories while they sat drinking and smoking; and there is certainly plenty of both activities in their tales.

In Britain they fared very well. Their first book appeared in 1865 – Smith Elder’s translation of The Conscript – and the same firm issued The Blockade four years later. Various publishers issued Erckmann–Chatrian books, including Richard Bentley, J. C. Hotten and Tinsley Brothers, but the writers really struck gold with Ward, Lock & Co. Starting with The Great Invasion of 1813–14 (1870), Ward, Lock & Co. were to publish nineteen of their titles, fourteen of them between 1871 and 1874, which were big sellers. Luckily for us, Ward, Lock’s catalogue was to include nearly all of Erckmann–Chatrian’s short story collections.

Their happy working relationship did not last, however. In 1889 they quarrelled violently and it seems that Chatrian arrogantly claimed the copyright of their work. (Remember that Chatrian had spent the past forty years as the revising half of the partnership.) Erckmann went to court and recovered damages from Chatrian’s secretary (I am unable to find out exactly why). Chatrian went into an immediate decline and died on 3 September 1890. Erckmann lived on for nine years, dying on 14 March 1899. They must have been rather sad years; he does not seem to have written anything of importance on his own following the split.

Within a few years of their deaths, the two writers had slipped into obscurity in Britain. The golden era of Ward, Lock had ended around 1880, and no new title by Erckmann–Chatrian appeared in Britain after 1901. There was a Blackie edition (in French) of Contes Fantastique in 1901 (somewhat late in the day, it must be said), and there were one or two French study editions of their novels, including one, Le Blocus (1913), with a fine introduction by Arthur Reed Ropes, a friend of M.R. James and himself the author of a splendid macabre novel, The Hole of the Pit (1914). But that was it for eighty years.

However, Erckmann–Chatrian did live on, even if only as pale and wan shapes in the corner, thanks to weird fiction. They had attracted the attention of two famous writers in the genre, as different as two authors could ever be – H. P. Lovecraft and M. R. James.

It is entirely due to these two that this book exists at all. If I may be allowed a little personal history, I first encountered the names Erckmann–Chatrian in M. R. James’s Collected Ghost Stories. Being very scared of spiders, I was fascinated to read in his introduction that ‘Other people have written of dreadful spiders – for instance, Erckmann–Chatrian in an admirable story called L’Araignée Crabe’. I spent many years wondering what terrors lay hidden behind that French title. Then, much later, I came across H. P. Lovecraft’s Supernatural Horror in Literature (a superlative researcher’s primer), and was fascinated to read more about Erckmann–Chatrian. Lovecraft noted that ‘“The Owl’s Ear” and “Waters of Death” are full of engulfing darkness and mystery, the latter embodying the familiar over-grown spider theme so frequently employed by weird fictionists’. It was a good bet that ‘Waters of Death’ was the same story as that mentioned by M. R. James. But how to get a copy? The British Museum catalogue did not mention either title, and I found that the Lovecraft version only appeared in an obscure American edition from the turn of the century, which was impossible to obtain. However, the British Museum catalogue did list several books of short stories by Erckmann–Chatrian and, on the assumption that one of them would contain this intriguing spider story, I set about tracking them down.

I never found an English book version of ‘L’Araignée Crabe’, much to my annoyance (in the end I got the French translated). What I did find was a set of splendid stories, forgotten for a century, which I duly reprinted in several of my anthologies. Then a chance encounter in 1978 with Thomas Tessier, who was an editor at Millington, led to his suggestion of an Erckmann–Chatrian collection. That Millington book was the original of this much expanded edition.

Erckmann–Chatrian stand apart from most of their contemporaries in European fiction who wrote in this vein. They did not essay the conte cruel, like Villiers de l’Isle Adam, or go in for paranoid fantasies, like Guy de Maupassant. Their tales are simple and straightforward, with all the effects up front. By rights, they should have dated severely. The pleasant surprise for modern readers is that they haven’t.

They wrote two fine, long tales: ‘The Wild Huntsman’, an essay on teratology with a sunshine-filled forest for a setting, and ‘The Man-Wolf’, a chilling story of lycanthropy, set in a winter-shrouded Black Forest castle. Their weirdest tales deal with metaphysics. ‘The Three Souls’ postulates that man is made up of three stages of development: vegetable, animal, and human. An enterprising Heidelberg scholar decides to bring them all out in the hero by starvation. Another seeker after wisdom tries to eavesdrop on the whole world through a freak of geology called ‘The Owl’s Ear’. In neither case are the results successful or happy.

‘The Invisible Eye’ is a remarkable tale of an old woman who induces suicide in the tenants of a hotel room through dummies on which she bestows magical powers. Like all of Erckmann–Chatrian’s work, the story’s florid style (probably exaggerated by the awkward translation of the day) only adds to the marvellous atmosphere. Their most memorable tale is ‘The Crab Spider’, and it is easy to see why M. R. James liked it so much. He borrowed its structure – mysterious deaths, terrible cause discovered, fiery climax – for his ‘The Ash-tree’.

In the works of Erckmann–Chatrian, we are able to step back over one hundred and fifty years, to the lost world of mid nineteenth century Europe, full of eminently believable characters – young men wooing, old men reminiscing, drinkers, smokers, noblemen, woodmen, peasants, witches, monsters, murderers, ghosts. Nothing like this is written today. Compared to their contemporaries – authors like Le Fanu or Bulwer-Lytton – Erckmann–Chatrian offer an easy target to critics, with their light touch and often bucolic tales. But these are stories with imagination second to none, and modern readers will not be disappointed. Welcome to the world of Erckmann–Chatrian.

Hugh Lamb

Sutton, Surrey

January 2018

THE INVISIBLE EYE (#u178dcf7c-9018-52e6-8797-b16226043927)

I

When I first started my career as an artist, I took a room in the roof-loft of an old house in the Rue des Minnesängers, at Nuremberg.

I had made my nest in an angle of the roof. The slates served me for walls, and the roof-tree for a ceiling: I had to walk over my straw mattress to reach the window; but this window commanded a magnificent view, for it overlooked both city and country beyond.

The old second-hand dealer, Toubec, knew the road up to my little den as well as I knew it myself, and was not afraid of climbing the ladder. Every week his goat’s head, surmounted by a rusty wig, pushed up the trap-door, his fingers clutched the edge of the floor, and in a noisy tone he cried: ‘Well, well, Master Christian, have we anything new?’

To which I answered: ‘Come in: why the deuce don’t you come in? I’m just finishing a little landscape, and want to have your opinion of it.’

Then his long thin spine lengthened itself out, until his head touched the roof; and the old fellow laughed silently.

I must do justice to Toubec: he never bargained with me. He bought all my pictures at fifteen florins apiece, one with the other, and sold them again at forty. He was an honest Jew.

This kind of existence was beginning to please me, and I was every day finding in it some new charm, when the city of Nuremberg was agitated by a strange and mysterious event.

Not far from my garret-window, a little to the left, rose the auberge of the Boeuf-gras, an old inn much frequented by the country-people. The gable of this auberge was conspicuous for the peculiarity of its form: it was very narrow, sharply pointed, and its edges were cut like the teeth of a saw; grotesque carvings ornamented the cornices and framework of its windows. But what was most remarkable was that the house which faced it reproduced exactly the same carvings and ornaments; every detail had been minutely copied, even to the support of the signboard, with its iron volutes and spirals.

It might have been said that these two ancient buildings reflected one another; only that behind the inn grew a tall oak, the dark foliage of which served to bring into bold relief the forms of the roof, while the opposite house stood bare against the sky. For the rest, the inn was as noisy and animated as the other house was silent. On the one side was to be seen, going in and coming out, an endless crowd of drinkers, singing, stumbling, cracking their whips; over the other, solitude reigned.

Once or twice a day the heavy door of the silent house opened to give egress to a little old woman, her back bent into a half-circle, her chin long and pointed, her dress clinging to her limbs, an enormous basket under her arm, and one hand tightly clutched upon her chest.

This old woman’s appearance had struck me more than once; her little green eyes, her skinny, pinched-up nose, her shawl, dating back a hundred years at least, the smile that wrinkled her cheeks, and the lace of her cap hanging down upon her eyebrows – all this appeared strange, interested me, and made me strongly desire to learn who this old woman was, and what she did in her great lonely house.

I imagined her as passing there an existence devoted to good works and pious meditation. But one day, when I had stopped in the street to look at her, she turned sharply round and darted at me a look the horrible expression of which I know not how to describe, and made three or four hideous grimaces at me; then dropping again her doddering head, she drew her large shawl about her, the ends of which trailed after her on the ground, and slowly entered her heavy door.

‘That’s an old mad-woman,’ I said to myself; ‘a malicious, cunning old mad-woman! I ought not to have allowed myself to be so interested in her. But I’ll try and recall her abominable grimace – Toubec will give me fifteen florins for it willingly.’

This way of treating the matter was far from satisfying my mind, however. The old woman’s horrible glance pursued me everywhere; and more than once, while scaling the perpendicular ladder of my lodging-hole, feeling my clothes caught in a nail, I trembled from head to foot, believing that the old woman had seized me by the tails of my coat for the purpose of pulling me down backwards.

Toubec, to whom I related the story, far from laughing at it, received it with a serious air.

‘Master Christian,’ he said, ‘if the old woman means you harm, take care; her teeth are small, sharp-pointed, and wonderfully white, which is not natural at her age. She has the Evil Eye! Children run away at her approach, and the people of Nuremberg call her Fledermausse!’

I admired the Jew’s clear-sightedness, and what he had told me made me reflect a good deal; but at the end of a few weeks, having often met Fledermausse without harmful consequences, my fears died away and I thought no more of her.

One night, when I was lying sound asleep, I was awoken by a strange harmony. It was a kind of vibration, so soft, so melodious, that the murmur of a light breeze through foliage can convey but a feeble idea of its gentle nature. For a long time I listened to it, my eyes wide open, and holding my breath the better to hear it.

At length, looking towards the window, I saw two wings beating against the glass. I thought, at first, that it was a bat imprisoned in my chamber; but the moon was shining clearly, and showed the wings of a magnificent night-moth, transparent as lace. At times their vibrations were so rapid as to hide them from my view; then for a while they would lie in repose, extended on the glass pane, their delicate articulations made visible anew.

This vaporous apparition in the midst of the universal silence opened my heart to the tenderest emotions; it seemed to me that a sylphid, pitying my solitude, had come to see me; and this idea brought the tears to my eyes.

‘Have no fear, gentle captive – have no fear!’ I said to it; ‘your confidence shall not be betrayed. I will not retain you against your wishes; return to heaven – to liberty!’

And I opened the window.

The night was calm. Thousands of stars glittered in space. For a moment I contemplated this sublime spectacle, and the words of prayer rose naturally to my lips. But then, looking down, I saw a man hanging from the iron stanchion which supported the sign of the Boeuf-gras; the hair in disorder, the arms stiff, the legs straightened to a point, and throwing their gigantic shadow the whole length of the street.

The immobility of this figure, in the moonlight, had something frightful in it. I felt my tongue grow icy cold, and my teeth chattered. I was about to utter a cry; but by what mysterious attraction I know not, my eyes were drawn towards the opposite house, and there I dimly distinguished the old woman, in the midst of the heavy shadow, squatting at her window and contemplating the hanging body with diabolical satisfaction.

I became giddy with terror; my strength deserted me, and I fell down in a heap insensible.

I do not know how long I lay unconscious. On coming to myself I found it was broad day. Mingled and confused noises rose from the street below, I looked out from my window.

The burgomaster and his secretary were standing at the door of the Boeuf-gras; they remained there a long time. People came and went, stopped to look, then passed on their way. At length a stretcher, on which lay a body covered with a woollen cloth, was brought out and carried away by two men.

Then everyone else disappeared.

The window in front of the house remained open still; a fragment of rope dangled from the iron support of the signboard. I had not dreamed – I had really seen the night-moth on my window-pane – then the suspended body – then the old woman!

In the course of that day Toubec paid me his weekly visit.

‘Anything to sell, Master Christian?’ he cried.

I did not hear him. I was seated on my only chair, my hands upon my knees, my eyes fixed on vacancy before me. Toubec, surprised at my immobility, repeated in a louder tone, ‘Master Christian! – Master Christian!’ then, stepping up to me, tapped me smartly on the shoulder.

‘What’s the matter? – what’s the matter? Are you ill?’ he asked.

‘No – I was thinking.’

‘What the deuce about?’

‘The man who was hung—’

‘Aha!’ cried the old broker; ‘you saw the poor fellow, then? What a strange affair! The third in the same place!’

‘The third?’

‘Yes, the third. I ought to have told you about it before; but there’s still time – for there’s sure to be a fourth, following the example of the others, the first step only making the difficulty.’

This said, Toubec seated himself on a box and lit his pipe with a thoughtful air.

‘I’m not timid,’ said he, ‘but if anyone were to ask me to sleep in that room, I’d rather go and hang myself somewhere else! Nine or ten months back,’ he continued, ‘a wholesale furrier, from Tubingen, put up at the Boeuf-gras. He called for supper, ate well, drank well, and was shown up to bed in the room on the third floor which they call the “green chamber”. The next day they found him hanging from the stanchion of the sign.

‘So much for number one, about which there was nothing to be said. A proper report of the affair was drawn up, and the body of the stranger buried at the bottom of the garden. But about six weeks afterwards came a soldier from Neustadt; he had his discharge, and was congratulating himself on his return to his village. All the evening he did nothing but empty mugs of wine and talk of his cousin, who was waiting his return to marry him. At last they put him to bed in the green chamber, and the same night the watchman passing along the Rue des Minnesängers noticed something hanging from the signboard-stanchion. He raised his lantern; it was the soldier, with his discharge-papers in a tin box hanging on his left thigh, and his hands planted smoothly on the outer seams of his trousers, as if he had been on parade!

‘It was certainly an extraordinary affair! The burgomaster declared it was the work of the devil. The chamber was examined; they replastered its walls. A notice of the death was sent to Neustadt, on the margin of which the clerk wrote – “Died suddenly of apoplexy”.

‘All Nuremberg was indignant against the landlord of the Boeuf-gras, and wished to compel him to take down the iron stanchion of his signboard, on the pretext that it put dangerous ideas in people’s heads. But you may easily imagine that old Nikel Schmidt didn’t listen with the ear on that side of his head.

‘“That stanchion was put there by my grandfather,” he said; “the sign of the Boeuf-gras has hung on it from father to son, for a hundred and fifty years; it does nobody any harm, it’s more than thirty feet up; those who don’t like it have only to look another way.”

‘People’s excitement gradually cooled down, and for several months nothing happened. Unfortunately, a student from Heidelberg, on his way to the University, came to the Boeuf-gras and asked for a bed. He was the son of a pastor.

‘Who would suppose that the son of a pastor would take into his head the idea of hanging himself to the stanchion of a public-house sign, because a furrier and a soldier had hung themselves there before him? It must be confessed, Master Christian, that the thing was not very probable – it would not have appeared more likely to you than it did to me. Well—’

‘Enough! Enough!’ I cried; ‘it is a horrible affair. I feel sure there is some frightful mystery at the bottom of it. It is neither the stanchion nor the chamber—’

‘You don’t mean that you suspect the landlord? – as honest a man as there is in the world, and belonging to one of the oldest families in Nuremberg?’

‘No, no! Heaven keep me from forming unjust suspicions of anyone; but there are abysses into the depths of which one dares not look.’

‘You are right,’ said Toubec, astonished at my excited manner; ‘and we had much better talk of something else. By-the-way, Master Christian, what about our landscape, the view of Sainte-Odile?’

The question brought me back to actualities. I showed the broker the picture I had just finished. The business was soon settled between us, and Toubec, thoroughly satisfied, went down the ladder, advising me to think no more of the student of Heidelberg.

I would very willingly have followed the old broker’s advice, but when the devil mixes himself up with our affairs he is not easily shaken off.

II

In solitude, all these events came back to my mind with frightful distinctness.

The old woman, I said to myself, is the cause of all this; she alone has planned these crimes, she alone has carried them into execution; but by what means? Has she had recourse to cunning only or really to the intervention of the invisible powers?

I paced my garret, a voice within me crying, ‘It is not without purpose that Heaven has permitted you to see Fledermausse watching the agony of her victim; it was not without design that the poor young man’s soul came to wake you in the form of a night-moth! No! all this has not been without purpose. Christian, Heaven imposes on you a terrible mission; if you fail to accomplish it, fear that you yourself may fall into the toils of the old woman! Perhaps at this moment she is laying her snares for you in the darkness!’

During several days these frightful images pursued me without cessation. I could not sleep; I found it impossible to work; the brush fell from my hand, and shocking to confess, I detected myself at times complacently contemplating the dreadful stanchion. At last, one evening, unable any longer to bear this state of mind, I flew down the ladder four steps at a time, and went and hid myself beside Fledermausse’s door, for the purpose of discovering her fatal secret.

From that time there was never a day that I was not on the watch, following the old woman like her shadow, never losing sight of her; but she was so cunning, she had so keen a scent that without even turning her head she discovered that I was behind her, and knew that I was on her track. But nevertheless, she pretended not to see me – went to the market, to the butcher’s, like a simple housewife; only she quickened her pace and muttered to herself as she went.

At the end of a month I saw that it would be impossible for me to achieve my purpose by these means, and this conviction filled me with an inexpressible sadness.

‘What can I do?’ I asked myself. ‘The old woman has discovered my intentions, and is thoroughly on her guard. I am helpless. The old wretch already thinks she sees me at the end of the cord!’

At length, from repeating to myself again and again the question, ‘What can I do?’ a luminous idea presented itself to my mind.

My chamber overlooked the house of Fledermausse, but it had no dormer window on that side. I carefully raised one of the slates of my roof, and the delight I felt on discovering that by this means I could command a view of the entire antique building can hardly be imagined.

‘At last I’ve got you!’ I cried to myself; ‘you cannot escape me now! From here I shall see everything. You will not suspect this invisible eye – this eye that will surprise the crime at the moment of its inception! Oh, Justice! It moves slowly, but it comes!’

Nothing more sinister than this den could be imagined – a large yard, paved with moss-grown flagstones; a well in one corner, the stagnant water of which was frightful to behold; a wooden staircase leading up to a railed gallery, to the left, on the first floor, a drain-stone indicated the kitchen; to the right, the upper windows of the house looked into the street. All was dark, decaying, and dank-looking.

The sun penetrated only for an hour or two during the day the depths of this dismal sty; then the shadows again spread over it – the light fell in lozenge shapes upon the crumbling walls, on the mouldy balcony, on the dull windows.

Oh, the whole place was worthy of its mistress!

I had hardly made these reflections when the old woman entered the yard on her return from market. First, I heard her heavy door grate on its hinges, then Fledermausse, with her basket, appeared. She seemed fatigued – out of breath. The border of her cap hung down upon her nose, as, clutching the wooden rail with one hand, she mounted the stairs.

The heat was suffocating. It was exactly one of those days when insects of every kind – crickets, spiders, mosquitoes – fill old buildings with their grating noises and subterranean borings.

Fledermausse crossed the gallery slowly, like a ferret that feels itself at home. For more than a quarter of an hour she remained in the kitchen, then came out and swept the stones a little, on which a few straws had been scattered; at last she raised her head, and with her green eyes carefully scrutinised every portion of the roof from which I was observing her.

By what strange intuition did she suspect anything? I know not; but I gently lowered the uplifted slate into its place, and gave over watching for the rest of that day.

The day following Fledermausse appeared to be reassured. A jagged ray of light fell into the gallery; passing this, she caught a fly, and delicately presented it to a spider established in an angle of the roof.

The spider was so large, that, in spite of the distance, I saw it descend then, gliding along one thread, like a drop of venom, seize its prey from the fingers of the dreadful old woman, and remount rapidly. Fledermausse watched it attentively; then her eyes half-closed, she sneezed, and cried to herself in a jocular tone: ‘Bless you, beauty! – bless you!’

For six weeks I could discover nothing as to the power of Fledermausse: sometimes I saw her peeling potatoes, sometimes spreading her linen on the balustrade. Sometimes I saw her spin; but she never sang, as old women usually do, their quivering voices going so well with the humming of the spinning-wheel. Silence reigned about her. She had no cat – the favourite company of old maids; not a sparrow ever flew down to her yard, in passing over which the pigeons seemed to hurry their flight. It seemed as if everything were afraid of her look.

The spider alone took pleasure in her society.

I now look back with wonder at my patience during those long hours of observation; nothing escaped my attention, nothing was indifferent to me; at the least sound I lifted my slate. Mine was a boundless curiosity stimulated by an indefinable fear.

Toubec complained.

‘What the devil are you doing with your time, Master Christian?’ he would say to me. ‘Formerly, you had something ready for me every week; now, hardly once a month. Oh, you painters! As soon as they have a few kreutzer before them, they put their hands in their pockets and go to sleep!’

I myself was beginning to lose courage. With all my watching and spying, I had discovered nothing extraordinary. I was inclining to think that the old woman might not be so dangerous after all – that I had been wrong, perhaps, to suspect her. In short, I tried to find excuses for her. But one fine evening, while, with my eye to the opening in the roof, I was giving myself up to these charitable reflections, the scene abruptly changed.

Fledermausse passed along her gallery with the swiftness of a flash of light. She was no longer herself: she was erect, her jaws knit, her look fixed, her neck extended; she moved with long strides, her grey hair streaming behind her.

‘Oh, oh!’ I said to myself, ‘something is going on!’

But the shadows of night descended on the big house, the noises of the town died out, and all became silent. I was about to seek my bed, when, happening to look out of my skylight, I saw a light in the window of the green chamber of the Boeuf-gras – a traveller was occupying that terrible room!

All my fears were instantly revived. The old woman’s excitement explained itself – she scented another victim!

I could not sleep at all that night. The rustling of the straw of my mattress, the nibbling of a mouse under the floor, sent a chill through me. I rose and looked out of my window – I listened. The light I had seen was no longer visible in the green chamber.

During one of these moments of poignant anxiety – whether the result of illusion or reality – I fancied I could discern the figure of the old witch, likewise watching and listening.

The night passed, the dawn showed grey against my window-panes, and, slowly increasing, the sounds and movements of the re-awakened town arose. Harassed with fatigue and emotion, I at last fell asleep; but my repose was of short duration, and by eight o’clock I was again at my post of observation.

It appeared that Fledermausse had passed a night no less stormy than mine had been; for, when she opened the door of the gallery, I saw that a livid pallor was upon her cheeks and skinny neck. She had nothing on but her chemise and a flannel petticoat; a few locks of rusty grey hair fell upon her shoulders. She looked up musingly towards my garret; but she saw nothing – she was thinking of something else.

Suddenly she descended into the yard, leaving her shoes at the top of the stairs. Doubtless her object was to assure herself that the outer door was securely fastened. She then hurried up the stairs, three or four at a time. It was frightful to see! She rushed into one of the side rooms, and I heard the sound of a heavy box-lid fall. Then Fledermausse reappeared in the gallery, dragging with her a life-size dummy – and this figure was dressed like the unfortunate student of Heidelberg!

With surprising dexterity the old woman suspended this hideous object to a beam of the over-hanging roof, then went down into the yard to contemplate it from that point of view. A peal of grating laughter broke from her lips – she hurried up the stairs, and rushed down again, like a maniac; and every time she did this she burst into fresh fits of laughter.

A sound was heard outside the street door, the old woman sprang to the dummy, snatched it from its fastening, and carried it into the house; then she reappeared and leaned over the balcony, with outstretched neck, glittering eyes, and eagerly listening ears. The sound passed away – the muscles of her face relaxed, she drew a long breath. The passing of a vehicle had alarmed the old witch.

She then, once more, went back into her chamber, and I heard the lid of the box close heavily.

This strange scene utterly confounded all my ideas. What could that dummy mean?

I became more watchful and attentive than ever. Fledermausse went out with her basket, and I watched her to the top of the street; she had resumed her air of tottering age, walking with short steps, and from time to time half-turning her head, so as to enable herself to look behind out of the corners of her eyes. For five long hours she remained abroad, while I went and came from my spying-place incessantly, meditating all the while – the sun heating the slates above my head till my brain was almost scorched.

I saw at his window the traveller who occupied the green chamber at the Boeuf-gras; he was a peasant of Nassau, wearing a three-cornered hat, a scarlet waistcoat, and having a broad laughing countenance. He was tranquilly smoking his pipe, unsuspicious of anything wrong.

About two o’clock Fledermausse came back. The sound of her door opening echoed to the end of the passage. Presently she appeared alone, quite alone in the yard, and seated herself on the lowest step of the gallery-stairs. She placed her basket at her feet and drew from it, first several bunches of herbs, then some vegetables – then a three-cornered hat, a scarlet velvet waistcoat, a pair of plush breeches, and a pair of thick worsted stockings – the complete costume of a peasant of Nassau!

I reeled with giddiness – flames passed before my eyes.

I remembered those precipices that drew one towards them with irresistible power – wells that have had to be filled up because of persons throwing themselves into them – trees that have had to be cut down because of people hanging themselves upon them – the contagion of suicide and theft and murder, which at various times has taken possession of people’s minds, by means well understood; that strange inducement, which makes people kill themselves because others kill themselves. My hair rose upon my head with horror!

But how could this Fledermausse – a creature so mean and wretched – have made discovery of so profound a law of nature? How had she found the means of turning it to the use of her sanguinary instincts? This I could neither understand nor imagine. Without more reflection, however, I resolved to turn the fatal law against her, and by its power to drag her into her own snare. So many innocent victims called for vengeance!

I hurried to all the old clothes-dealers in Nuremberg; and by the evening I arrived at the Boeuf-gras, with an enormous parcel under my arm.

Nikel Schmidt had long known me. I had painted the portrait of his wife, a fat and comely dame.

‘Master Christian!’ he cried, shaking me by the hand, ‘to what happy circumstance do I owe the pleasure of this visit?’

‘My dear Mr Schmidt, I feel a very strong desire to pass the night in that room of yours up yonder.’

We were on the doorstep of the inn, and I pointed up to the green chamber. The good fellow looked suspiciously at me.

‘Oh! don’t be afraid,’ I said, ‘I’ve no desire to hang myself.’

‘I’m glad of it! I’m glad of it! for frankly, I should be sorry – an artist of your talent. When do you want the room, Master Christian?’

‘Tonight.’

‘That’s impossible – it’s occupied.’

‘The gentleman can have it at once, if he likes,’ said a voice behind us; ‘I shan’t stay in it.’

We turned in surprise. It was the peasant of Nassau; his large three-cornered hat pressed down upon the back of his neck, and his bundle at the end of his travelling-stick. He had learned the story of the three travellers who had hung themselves.

‘Such chambers!’ he cried, stammering with terror; ‘it’s – it’s murdering people to put them into such! – you – you deserve to be sent to the galleys!’

‘Come, come calm yourself,’ said the landlord; ‘you slept there comfortably enough last night.’

‘Thank Heaven! I said my prayers before going to rest, or where should I be now?’

And he hurried away, raising his hands to heaven.

‘Well,’ said Master Schmidt, stupefied, ‘the chamber is empty, but don’t go into it to do me an ill turn.’

‘I might be doing myself a much worse one,’ I replied.

Giving my parcel to the servant-girl, I went and seated myself among the guests who were drinking and smoking.

For a long time I had not felt more calm, more happy to be in the world. After so much anxiety, I saw approaching my end – the horizon seemed to grow lighter. I know not by what formidable power I was being led on. I lit my pipe, and with my elbow on the table and a jug of wine before me, and sometimes rousing myself to look at the woman’s house, I seriously asked myself whether all that had happened to me was more than a dream. But when the watchman came, to request us to vacate the room, graver thoughts took possession of my mind, and I followed, in meditative mood, the little servant-girl who preceded me with a candle in her hand.

III

We mounted the window flight of stairs to the third storey; arrived there, she placed the candle in my hand, and pointed to a door.

‘That’s it,’ she said, and hurried back down the stairs as fast as she could go.

I opened the door. The green chamber was like all other inn bedchambers; the ceiling was low, the bed was high. After casting a glance round the room, I stepped across to the window.

Nothing was yet noticeable in Fledermausse’s house, with the exception of a light, which shone at the back of a deep obscure bedchamber – a nightlight, doubtless.

‘So much the better,’ I said to myself, as I re-closed the window-curtains; ‘I shall have plenty of time.’

I opened my parcel, and from its contents put on a woman’s cap with a broad frilled border; then, with a piece of pointed charcoal, in front of the glass, I marked my forehead with a number of wrinkles. This took me a full hour to do; but after I had put on a gown and a large shawl, I was afraid of myself; Fledermausse herself was looking at me from the depths of the glass!

At that moment the watchman announced the hour of eleven. I rapidly dressed the dummy I had brought with me like the one prepared by the old witch. I then drew apart the window-curtains.

Certainly, after all I had seen of the old woman – her infernal cunning, her prudence, and her address – nothing ought to have surprised even me; yet I was positively terrified.

The light, which I had observed at the back of her room, now cast its yellow rays on her dummy, dressed like the peasant of Nassau, which sat huddled up on the side of the bed, its head dropped upon its chest, the large three-cornered hat drawn down over its features, its arms pendant by its sides, and its whole attitude that of a person plunged in despair.

Managed with diabolical art, the shadow permitted only a general view of the figure, the red waistcoat and its six rounded buttons alone caught the light; but the silence of night, the complete immobility of the figure, and its air of terrible dejection, all served to impress the beholder with irresistible force; even I myself, though not in the least taken by surprise, felt chilled to the marrow of my bones. How, then, would a poor countryman taken completely off his guard have felt? He would have been utterly overthrown; he would have lost all control of will, and the spirit of imitation would have done the rest.

Scarcely had I drawn aside the curtains than I discovered Fledermausse on the watch behind her window-panes.

She could not see me. I opened the window softly, the window over the way softly opened too; then the dummy appeared to rise slowly and advance towards me; I did the same, and seizing my candle with one hand, with the other threw the casement wide open.

The old woman and I were face to face; for, overwhelmed with astonishment, she had let the dummy fall from her hands. Our two looks crossed with an equal terror.

She stretched forth a finger, I did the same; her lips moved, I moved mine; she heaved a deep sigh and leant upon an elbow. I rested in the same way.

How frightful the enacting of this scene was I cannot describe; it was made up of delirium, bewilderment, madness. It was a struggle between two wills, two intelligences, two souls, one of which sought to crush the other; and in this struggle I had the advantage. The dead were on my side.

After having for some seconds imitated all the movements of Fledermausse, I drew a cord from the folds of my petticoat and tied it to the iron stanchion of the signboard.

The old woman watched me with open mouth. I passed the cord round my neck. Her tawny eyeballs glittered; her features became convulsed.

‘No, no!’ she cried, in a hissing tone; ‘no!’

I proceeded with the impassibility of a hangman.

Then Fledermausse was seized with rage.

‘You’re mad! you’re mad!’ she cried, springing up and clutching wildly at the sill of the window; ‘you’re mad!’

I gave her no time to continue. Suddenly blowing out my light, I stooped like a man preparing to make a vigorous spring, then seizing my dummy slipped the cord about its neck and hurled it into the air.

A terrible shriek resounded through the street; then all was silent again.

Perspiration bathed my forehead. I listened a long time. At the end of an hour I heard far off – very far off – the cry of the watchman, announcing that midnight had struck.

‘Justice is at last done,’ I murmured to myself; ‘the three victims are avenged. Heaven forgive me!’

I saw the old witch, drawn by the likeness of herself, a cord about her neck, hanging from the iron stanchion projecting from her house. I saw the thrill of death run through her limbs and the moon, calm and silent, rose above the edge of the roof, and shed its cold pale rays upon her dishevelled head.

As I had seen the poor young student of Heidelberg, I now saw Fledermausse.

The next day all Nuremberg knew that ‘the Bat’ had hung herself. It was the last event of the kind in the Rue des Minnesängers.

THE OWL’S EAR (#u178dcf7c-9018-52e6-8797-b16226043927)

On a warm evening in July 1835, Kasper Boeck, a shepherd of the small village of Hirchwiller, presented himself before the burgomaster, Pétrus Mauerer, who had just finished his supper and was having a glass of Kirsch to help his digestion.

The burgomaster, tall and wiry, with his upper lip covered with a huge grey moustache, had in days gone by served in the armies of the arch-duke Charles. His was a bantering disposition, he had the village under his thumb, it was said, and ruled it with a rod of iron.

‘Mr Burgomaster!’ exclaimed the shepherd.

But Pétrus Mauerer, without waiting for the end of his speech, frowned and said to him: ‘Kasper Boeck, start by removing your hat, remove your dog from the room, and then speak clearly, intelligibly, without stammering, so that I can understand you.’

Kasper took out his dog and returned with his hat off.

‘Ah well!’ said Pétrus, seeing him silent. ‘What’s going on?’

‘What’s going on is that the “ghost” has appeared again in the ruins of Geierstein!’

‘Ah! I suspected it. Did you get a good look at it?’

‘Very good, Mr Burgomaster.’

‘Without shutting your eyes?’

‘Yes, Mr Burgomaster. I had my eyes wide open. It was a fine moonlit night.’

‘What shape did it have?’

‘That of a small man.’

‘Good!’ And turning towards a glass door on his left, ‘Katel!’ the burgomaster shouted.

An old female servant half-opened the door.

‘Sir?’

‘I am going to take a walk on the hill. You will wait for me till ten o’clock. Here is the key.’

‘Yes, master.’

Then the old soldier took down a gun from above the door, checked its priming, and slung it across his shoulder; then addressing Kasper Boeck: ‘You will alert the constable to meet me in the small holly bush lane behind the mill,’ he said. ‘Your “ghost” must be some marauder … but if it turns out to be a fox, I will have myself a magnificent hat with long flaps made of it.’

Mauerer and the humble Kasper went out. The weather was splendid, the stars clear and innumerable. While the shepherd went and knocked at the constable’s door, the burgomaster disappeared up a small lane of alder trees, which wound its way behind the old church. Two minutes later Kasper and the constable Hans Goerner, a pistol at his hip, ran to join Master Pétrus in the holly-lined lane. The three of them proceeded together to the ruins of Geierstein.

These ruins, situated some twenty minutes from the village, seemed quite insignificant; they were some pieces of dilapidated walls, four to six feet high, which stretched out in the midst of the heather. Archaeologists call them the aqueducts of Seranus, the Roman camp of the Holderlock, or the remains of Théodoric, according to their whim. The only thing which was really remarkable in these ruins was the stairway of a chamber hewn from the rock.

In a manner contrary to spiral stairs, instead of concentric circles narrowing at each step, the spiral of this one got wider, so that the bottom of the cistern was three times wider than the entrance. Was it a whim of architecture, or rather some other reason which gave rise to this bizarre structure? Little does it matter! The fact is that there resulted from it in the cistern this vague roaring such as can be heard by pressing a seashell to one’s ear, and that one can hear the steps of the travellers on the gravel, the stirring of the air, the rustling of the leaves, and even the distant words of those passing along at the foot of the hill.

And so our three characters climbed the little path, between the vines and the kitchen-gardens of Hirchwiller.

‘I can see nothing,’ said the burgomaster, raising his nose mockingly.

‘Nor I,’ repeated the constable, imitating the tone of the other.

‘It is in the hole,’ murmured the shepherd.

‘We shall see, we shall see,’ took up the burgomaster.

Thus it was that after a quarter of an hour they arrived at the entrance to the chamber. The night was bright, clear, and perfectly calm. As far as the eye could see the moon outlined nocturnal landscapes of bluish lines, studded with slender trees, whose shadows seem sketched in black pencil. The heather and the broom in blossom perfumed the air with their sharp smell and the frogs of a neighbouring pool sang their full-throated chorus, interrupted with silences. But all these details escaped our fine countrymen. Their sole thoughts were of catching the ‘spirit’.

When they reached the stair, all three stopped and listened, then looked into the darkness. Nothing appeared, nothing stirred.

‘Confound it,’ said the burgomaster. ‘We have forgotten to bring a candle. You go down, Kasper, you know the way better than me. I’ll follow.’

At this suggestion the shepherd stepped back suddenly. If left to his own devices the poor man would have taken flight. His woeful countenance made the burgomaster burst out laughing.

‘Ah well, Hans, since he doesn’t want to go down, you show me the way,’ he said to the constable.

‘But, master burgomaster,’ said the latter, ‘you are well aware that there are steps missing. We would risk breaking our necks!’

‘Well then, what are we to do?’

‘Yes, what are we to do?’

‘Send your dog,’ resumed Pétrus.

The shepherd whistled for his dog, showed him the stairs, urged him down; but he was no more willing than the rest to try his luck.

At that moment a bright idea struck the constable.

‘Hey, Mr Burgomaster,’ he said. ‘If you were to fire a shot into it …’

‘Indeed,’ exclaimed the other, ‘you are right. One will see clearly, at least.’

And without hesitation the good fellow approached the stair, levelling his gun.

But because of the acoustic effect described earlier, the ‘spirit’, the marauder, the individual, who was actually in the chamber, had heard everything. The idea of being shot at didn’t appeal to him, for in a piercing, high-pitched voice he shouted out: ‘Stop! Don’t shoot! I’m coming up!’

Then the three dignitaries looked at each other, chuckling, and the burgomaster, leaning forward again into the opening, exclaimed in a coarse voice: ‘Hurry up, you rogue, or I’ll shoot! Hurry up!’

He cocked his gun. The click appeared to hasten the ascent of the mysterious character. Stones could be heard rolling. However it took another minute before he appeared, the chamber being over sixty feet deep.

What was this man doing in the midst of such darkness? He must be some great criminal! Thus at least thought Pétrus Mauerer and his assistants.

At last a vague shape emerged from the shadow, then slowly a small man, four and a half feet tall at the most, thin, in rags, his face wizened and yellow, his eyes sparkling like those of a magpie and his hair untidy, came out shouting: ‘What right have you to come and trouble my studies, you wretches?’

This grandiloquence hardly matched his clothes and his appearance, so the indignant burgomaster replied: ‘Try and show some respect, you rogue, or I’ll start by giving you a thrashing.’

‘A thrashing!’ said the little man, hopping with anger and standing right under the burgomaster’s nose.

‘Yes,’ resumed the former, who couldn’t help but admire the courage of the pygmy, ‘if you don’t answer satisfactorily the questions that I am going to put to you. I am the burgomaster of Hirchwiller, here is the village constable and the shepherd with his dog. We are stronger than you … be sensible and tell me who you are, what you are doing here, and why you don’t dare appear in broad daylight. Then we can see what shall be done with you.’

‘All that’s none of your business,’ answered the little man in his curt voice. ‘I shall not answer you.’

‘In that case, march,’ said the burgomaster, grasping him by the nape of the neck. ‘You’ll spend the night in prison.’

The little man struggled but in vain. Completely exhausted, he said (not without some nobility), ‘Let me go, sir. I yield to force. I shall follow you.’

The burgomaster, who wasn’t lacking in manners himself, became calmer in his turn.

‘Your word?’ he said.

‘My word!’

‘Fine … Quick march!’

And that is how on the night of 29 July 1835 the burgomaster captured a small red-haired man, as he emerged from the cave of Geierstein.

On their return to Hirchwiller, the vagabond was double-locked in, not forgetting the outside bolt and the padlock. Afterwards everyone went to recover from their exertions. Pétrus Mauerer, once in bed, pondered over this strange adventure till midnight.

The next day, about nine o’clock, Hans Goerner, the constable, having received orders to bring the prisoner to the town-hall, so that he could undergo a new examination, went with four sturdy lads to the cell. They opened the door, quite curious to look at the will-o’-the-wisp. They saw him hanging by his tie from the bars of the skylight. Several say that he was still kicking … others that he was already stiff. Whichever it was, someone ran off to get Pétrus Mauerer, to inform him of the fact. What is certain is that at the arrival of the latter, the little man had breathed his last.

The magistrate and the doctor of Hirchwiller drew up a formal report of the catastrophe. The unknown man was buried and all was settled.

Now about three weeks after these events, I went to see my cousin Pétrus Mauerer. I am his closest relative and, consequently, his heir. This circumstance maintains an intimate relationship between us. We were dining together, chatting of this and that, when the burgomaster told me the little story as I have just related it.

‘It’s strange, cousin,’ I said to him, ‘really strange. And you have no other information on this unknown man?’

‘None.’

‘Have you found anything that could put you on the track of his intentions?’

‘Absolutely nothing, Christian.’

‘But after all, what could he have been doing in the chamber? What was he living on?’

The burgomaster shrugged his shoulders, filled our glasses, and answered me: ‘Your health, cousin.’

‘And yours.’

We remained silent for some moments. It was impossible for me to accept the sudden end of the adventure. In spite of myself I gloomily pondered over the sad fate of certain men who appear and disappear in this world, like the grass in the fields, without leaving the slightest memory or the slightest regret.

‘Cousin,’ I resumed, ‘how long would it take from here to the ruins of Geierstein?’

‘Twenty minutes at the most. Why?’

‘Because I would like to see them.’

‘You know that today we have a meeting of the town council and I cannot accompany you.’

‘Oh! I shall be able to find them on my own.’

‘No, the constable shall show you the way, he has nothing better to do.’ My dear cousin called his servant.

‘Katel, get Hans Goerner … make him hurry up … It’s two o’clock. I must go.’

The servant went out and the constable wasn’t long in coming. He received orders to guide me to the ruins.

While the burgomaster was making his way solemnly to the council chamber, we were already going up the hill. Hans Goerner pointed out the remains of the aqueduct. At this point the rocky ridges of the plateau, the bluish distances of the Hundsrück, the dismal dilapidated walls, covered in a dark ivy, the tolling of the bell of Hirchwiller, summoning the dignitaries to the meeting, the constable panting, clinging to the brushwood … took on in my eyes a sad, harsh hue. It was the story of this poor hanged man which stained the horizon.

The stairway to the chamber appeared very strange, its spiral elegant. The prickly bushes in the clefts of each step, the deserted appearance of the surroundings, all were in harmony with my sadness. We descended. Soon the bright point of the opening which seemed to grow narrower and narrower and to assume the form of a star with curved rays, alone sent us its pale light.

When we reached the bottom of the chamber what a superb view awaited us of those stairs lit up underneath, throwing their shadows with wonderful regularity. Then I heard the buzzing which Pétrus had told me about; the huge granite conch had as many echoes as stones!

‘Since the little man, has anyone come down here?’ I asked the constable.

‘No, sir. The peasants are afraid. They think that the hanged man will return.’

‘And you?’

‘Me, I’m not curious.’

‘But the magistrate … his duty was …’

‘Humph! What would he be doing in the “Owl’s Ear”?’

‘They call this the Owl’s Ear?’

‘Yes.’

‘It is almost that,’ I said, looking up. ‘This inverted vault forms the outer ear very well, the underneath part of the steps represents the drum, and the bends of the stairway the cochlea, the labyrinth and the opening of the ear. That then explains the murmuring that we can hear: we are at the bottom of a colossal ear.’

‘That is very possible,’ said Hans Goerner, who seemed to understand nothing of my observations.

We were on our way back up. I had already taken the first steps when I felt something snap beneath my foot. I bent down to see what it could be and I noticed at the same time a white object in front of me. It was a sheet of torn paper. As for the hard matter that had been pulverized, I recognized a sort of pot made of glazed stoneware.

‘Ho! Ho!’ I said to myself, ‘this will be able to throw some light on the burgomaster’s story for us.’

And I joined Hans Goerner, who was by now waiting for me at the kerb of the cistern.

‘Now, sir,’ he shouted to me, ‘where would you like to go?’

‘First of all let us sit down a little, we shall see presently.’

And I found a place on a large stone, while the constable let his hawk-like eyes gaze all around the village, to discover marauders in the gardens, if there were any.

I carefully examined the stoneware vessel, of which no more than a fragment remained. This fragment took the shape of a funnel, lined with down on the inside. It was impossible for me to make out its purpose. Next I read the piece of paper, which was written on in a very steady hand. I transcribe it here according to the text. It seems to be a continuation of another sheet, for which I have since searched in the vicinity of the ruin, but in vain.

My ‘microeartrumpet’ has therefore the double advantage of multiplying ad infinitum the intensity of sounds, and of being able to fit the ear, which in no way impedes the observer. You cannot imagine, my dear master, the charm that one feels on hearing these thousands of imperceptible sounds which, on fine summer days, blend into one mighty buzzing. The bee has his song like the nightingale, the wasp is the warbler of the mosses, the cicada is the lark of the tall grasses, in this the mite is the wren – it has only a sigh, but this sigh is melodious!

This discovery which, from the sentimental point of view, makes us live the life of universal nature, surpasses in its importance all that I could say about it.

After so many sufferings, privations, and worries how happy it is in the end to gather the rewards of our labours! With what leaps the soul rises up to the divine author of these microscopic worlds, whose splendour is revealed to us. What then are these long hours of anguish, hunger, scorn which overwhelmed us in the past? Nothing, sir, nothing! Tears of gratitude wet our eyes. One is proud to have bought through suffering new joys for humanity and to have contributed to its improvement. But however vast, however admirable are the first results of my ‘microeartrumpet’, its advantages are not limited to that alone. There are others more positive, more material in some respects, and which can be translated into figures.

Just as the telescope causes us to discover myriads of worlds, completing their harmonious revolutions in the infinite, so too my ‘microeartrumpet’ extends the sense of hearing beyond all the limits of possibility. Thus, sir, I shall not stop at the circulation of the blood and vital fluids in the living body; you hear them running with the impulsiveness of cataracts, you perceive them with a distinctness which terrifies you, the slightest irregularity in the pulse, the lightest obstacle strikes you and has on you the effect of a rock against which break the waves of a torrent.

It is undoubtedly a tremendous conquest for the development of our physiological and pathological knowledge, but it is not on this point that I insist.

By pressing your ear to the ground you hear the hot springs surging at immeasurable depths, you assess their volume, the currents, the obstacles.

Would you like to go any further? Enter an underground chamber sufficiently large to pick up a considerable quantity of sounds; then, at night, when all is asleep, when nothing disturbs the inner sounds of our globe, listen!

Sir, all that it is possible for me to tell you at present, because in the midst of my abject misery, my privations, and often my despair, I have only a few lucid moments left to gather together geological observations, all that I can assert for you is that the bubbling incandescent lava, the glow of boiling substances is something terrifying and sublime, and which can only be compared to the impression of the astronomer sounding the endless depths of the universe with his telescope.

However, I must admit that these impressions need to be studied further and classified methodically, so as to draw from them fixed conclusions. Consequently as soon as you condescend, my dear and worthy master, to send to me at Neustadt the small sum that I ask to provide for my basic needs, we shall see that we agree with a view to establishing three subterranean observatories, one in the valley of Catania, the other in Iceland, and the third in one of the valleys of Capac-Uren, Songay, or Cayembé-Uren, the deepest of the Cordilleras, and as a consequence …

Here the letter stopped.

I was dumbfounded. Had I read the ideas of a madman, or rather the fulfilled inspirations of a genius? What was I to say? or think? Thus this man, this wretch, living at the bottom of a den like a fox, dying of hunger, had perhaps been one of those chosen people, whom the Supreme Being sends to earth, to enlighten future generations.

And this man had hanged himself out of disgust and despair! His request had not been answered when he only asked for a piece of bread in exchange for his discovery. It was horrible.

A long time, a very long time, I stayed there, dreaming, thanking heaven for having limited my intelligence to the everyday needs for life, for not having wanted to make myself superior to the common crowd. Finally the constable seeing me staring, my mouth wide open, ventured to touch my shoulder: ‘M. Christian,’ he said to me, ‘look it is getting late. The burgomaster must have returned from the meeting.’

‘Ah! That’s right!’ I exclaimed, crumpling up the paper. ‘On our way.’

We climbed down the hill again.

My worthy cousin received me, his face beaming, on the threshold of his house: ‘Well, well! Christian! Have you found anything of this idiot who hanged himself?’

‘No.’

‘As I suspected. He was some madman who escaped from Stefansfeld or elsewhere. Indeed he did well to hang himself. When one is good for nothing, it’s the simplest thing.’

The following day I left Hirchwiller. I shall never go back.

THE WHITE AND THE BLACK (#u178dcf7c-9018-52e6-8797-b16226043927)

I

At that time we passed our evenings at Brauer’s alehouse, which opens upon the square of Vieux-Brisach. After eight o’clock there used to drop in, one by one, Frederick Schultz the notary; Frantz Martin the burgomaster, Christopher Ulmett the magistrate; the counsellor Klers; the engineer Rothan; the young organist Theodore Blitz; and some others of the chief townsfolk, who all sat around the same table and drank their foaming bok-bier like brothers.

The apparition of Theodore Blitz, who came to us from Jena with a letter of recommendation from Harmosius – his dark eyes, his brown dishevelled hair, his thin white nose, his metallic voice, and his mystic ideas – occasioned us some little disquiet. It used to trouble us to see him rise abruptly and pace two or three times up and down the room, gesticulating the while, mocking with a strange air the Swiss landscapes with which the walls were adorned – lakes of indigo-blue, mountains of an apple-green, paths of brilliant red. Then he would seat himself down again, empty his glass at a gulp, and commence a discussion about the music of Palestrina, about the lute of the Hebrews, about the introduction of the organ into our churches, about the shophar, the sabbatic epochs, etc. He would knit his brows, plant his sharp elbows on the edge of the table, and lose himself in deep thought. Yes, he perplexed us not a little – we others who were grave and accustomed to methodical ideas. However, it was necessary to put up with it; and the engineer Rothan himself, in spite of his bantering spirit, in the end grew calm and no longer continued to contradict the young organist when he was right.

Theodore Blitz was plainly one of those nervously organised beings who are affected by every change of temperature. The year of which I speak was extremely warm; we had several heavy storms towards the autumn, and folk began to fear for the wine harvest.

One evening all our little world was gathered, according to custom, around the table, with the exception of the magistrate Ulmett and the organist. The burgomaster talked about the weather and great hydraulic works. As for me I listened to the wind gamboling without amongst the plane-trees of the Schlossgarten, to the drip of the water from the spouts, and to its dashing against the windows. From time to time one could hear a tile blown off a roof, a door shut to with a bang, a shutter beat against a wall. Then would arise the great clamour of the storm, sweeping, sighing, and groaning in the distance, as if all the invisible powers were seeking and calling on one another in the darkness, while living things hid themselves, sitting in corners, in order to escape a fearful meeting with them.

From the church of Saint-Landolphe nine o’clock sounded, when Blitz hurriedly entered, shaking his hat like one possessed, and saying in his husky voice: ‘Surely the Evil One is about his work! The white and the black are having a tussle. The nine times nine thousand nine hundred and ninety thousand spirits of Envy battle and tear themselves. Go, Ahriman! Walk! Ravage! Lay waste! The Amschaspands are in flight! Oromage veils her face! What a time, what a time!’

And so saying he walked round the room, stretching his long skinny limbs, and laughing by jerks.

We were all astounded at such an entry, and for some seconds no one spoke a word. Then, however, the engineer Rothan, led on by his caustic humour, said: ‘What nonsense is that you are singing there, M. Organist? What do Amschaspands signify to us? or the nine times nine thousand nine hundred and ninety thousand spirits of Envy? Ha! ha! ha! It is really comic. Where on earth did you pick up such strange language?’

Theodore Blitz stopped suddenly short in his walk and shut one eye, while the other, wide open, shone with a diabolic irony.

When Rothan had finished: ‘Oh, engineer,’ said he; ‘oh! sublime spirit, master of the trowel, and mortar, director of stones, he who orders right angles, angles acute, angles obtuse, you are right – a hundred times right.’

He bent himself with a mocking air, and went on: ‘Nothing exists but matter – the level, the rule, and the compass. The revelations of Zoroaster, of Moses, of Pythagoras, of Odin – the harmony, the melody, art, sentiment, they are all dreams, unworthy of an enlightened intellect such as yours. To you belongs the truth, the eternal truth. Ha! ha! ha! I bow myself before you: I salute you; I prostrate myself before your glory, imperishable as that of Nineveh and of Babylon.’

Finishing his speech, he made two little turns on his heels, and uttered a laugh so piercing that it was more like the crowing of a cock at daybreak.

Rothan was getting angry, when at the moment the old magistrate Ulmett came in, his head protected by a great otter-skin cap, his shoulders covered by his bottle-green greatcoat bordered with fox-skin. His hands hung down beside him, his back was bent, his eyes were half-closed, his big nose was red, and his large cheeks were wet with rain. He was as wet as a drake.

Outside the rain fell in torrents, the gutters gushed over, the spouts disgorged themselves, and the ditches were swollen into little rivers.

‘Ah, heavens!’ cried the good fellow. ‘Perhaps it was foolish to come out on such a night, and after such work too – two inquests, verbal processes, interrogatories! The bok-bier and old friends, though, would make me swim across the Rhine.’

And muttering these words he put off his otter-skin cap and opened his great pelisse to take out his long tobacco-pipe and his pouch, which he carefully laid down upon the table. After that he hung his greatcoat and his hat up beside the window, and called out: ‘Brauer!’

‘Well, M. Magistrate, what do you want?’

‘You would do well to put to the shutters. Believe me, this storm will wind up with some thunder.’

The innkeeper went out and put the shutters to, and the old magistrate, sitting down in his corner, heaved a deep sigh.

‘You know what has happened, burgomaster?’ he asked in a solemn voice.

‘No. What has occurred, my old Christopher?’

Before he replied M. Ulmett threw a glance around the room.

‘We are here alone, my friends,’ said he, ‘so I am able to tell you. About three o’clock this afternoon some one found poor Gredel Dick under the sluice of the miller at Holderloch.’

‘Under the sluice at Holderloch?’ cried all.

‘Yes; a cord round her neck.’

In order to understand how these words affected us it is necessary that you should know that Gredel Dick was one of the prettiest girls in Vieux-Brisach; a tall brunette, with blue eyes and red cheeks; the only daughter of an old anabaptist, Petrus Dick, who farmed considerable portions of the Schlossgarten. For some time she had seemed sad and melancholy – she who had beforetime been so merry in the morning at the washing-place, and in the evening at the well in the midst of her friends. She had been seen crying, and her sorrow had been ascribed to the incessant pursuit of her by Saphéri Mutz, the postmaster’s son – a big fellow, thin, vigorous, with an aquiline nose and curling black hair. He followed her like a shadow, and never let her off his arm at the dances.

There had been some talk about their marriage, but old Mutz, his wife, Karl Bremer his son-in-law, and his daughter Saffayel, were opposed to the match, all agreeing that a ‘heathen’ should not be introduced into the family.

For three days past nothing had been seen of Gredel. No one knew what had become of her. You may imagine the thousand different thoughts which crowded upon us when we heard that she was dead. No one thought any longer of the discussion between Theodore Blitz and the engineer Rothan touching invisible spirits. All eyes were fixed on M. Christopher Ulmett, who, his large bald head bent, his heavy white eyebrows knit, gravely filled his pipe, with a meditative air.

‘And Mutz – Saphéri Mutz?’ asked the burgomaster. ‘What has become of him?’

A slight flush coloured the cheeks of the old man as he answered, after some seconds of thought: ‘Saphéri Mutz? He has gone.’

‘Gone!’ cried little Klers. ‘Then he acknowledges his guilt?’

‘It certainly seems so to me,’ said the old magistrate simply. ‘One does not scamper off for nothing. As for the rest, we have searched his father’s place, and found all the house upset. The folk seemed struck with consternation. The mother raved and tore her hair; the daughter wore her Sunday clothes, and danced about like a fool. It was impossible to get anything out of them. As to Gredel’s father, the poor fellow is in the deepest despair. He does not wish to say anything against his child, but it is certain that Gredel Dick left the farm of her own accord on Tuesday last in order to meet Saphéri. The fact is attested by all the neighbours. Now the gendarmes are scouring the country. We shall see, we shall see!’

Then there was a long silence. Outside the rain fell heavily.

‘It is abominable!’ cried the burgomaster suddenly. ‘Abominable! To think that every father of a family, even such as bring up their children in the fear of God, are exposed to such misfortunes.’

‘Yes,’ replied Ulmett, lighting his pipe. ‘It is so. They say, no doubt rightly, that heaven orders all things; but the spirit of darkness seems to me to meddle a good deal more than is necessary in them. For one good fellow how many villains do we find, without faith or law? And for one good action how many evil ones? I tell you, my friends, if the Evil One were to count his flock—’

He had not time to finish, for at that moment a terrific flash of lightning glared in through the chinks of the shutters, making the lamp burn dim. It was immediately followed by a clap of thunder, crashing, jerky – one of those claps which make you tremble. One might have thought that the world was coming to an end.

The clock of the church of Saint-Landolphe just then struck the half-hour. The tolling bells seemed to be just hard by one. From far, very far off, there came a trembling plaintive voice, crying: ‘Help! Help!’

‘Some one cries for help,’ said the burgomaster.

‘Yes,’ said the others, turning pale, and listening.

While we were all thus in fright, Rothan, curling his lips in a joking fashion, broke out: ‘Ha! ha! ha! It is Mademoiselle Roesel’s cat singing its love story to Monsieur Roller, the young first tenor.’

Then dropping his voice and lifting his hand with a tragic gesture, he went on: ‘The time has sounded from the belfry of the chateau!’

‘Ill-luck to those who laugh at such a cry,’ said old Christopher, rising.

He went towards the door with a solemn step, and we all followed him, even the fat innkeeper, who held his cotton cap in his hand and murmured a prayer very low. Rothan alone did not stir from his seat. As for me, I was behind the others, with outstretched neck, looking over their shoulders.

The glass door was scarcely opened when there came another flash of lightning. The street, with its white flags washed by the rain, its flushed gutters, its multitude of windows, its old gables, its signboards, glared out from the night, and then was swallowed up in the darkness.

That glance of the eye allowed me to see the steeple of Saint-Landolphe with its innumerable little carvings all clothed in white light. In the steeple were the bells hanging to black beams, with their clappers, and their ropes hanging down to the body of the church. Below that was a stork’s nest, half torn in pieces by the wind – the young ones with their beaks out, the mother at her wits’ end, her wings extended, while the male-bird flew about the shining steeple, his breast thrown forward, his neck bent, his long legs thrown out behind as if defying the thunder peals.

It was a strange sight, a veritable Chinese picture – thin, delicate, light, something strange, terrible, upon a black background of clouds broken with streaks of gold.

We stood, with open mouths, upon the threshold of the inn, and asked: ‘What did you hear, M. Ulmett? What can you see, M. Klers?’