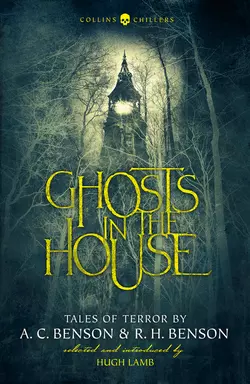

Ghosts in the House: Tales of Terror by A. C. Benson and R. H. Benson

Hugh Lamb

A. C. Benson

R. Benson H.

A collection of rare ghosts and horror stories by the brothers of one of the finest writers of the genre, E. F. Benson.The Benson brothers – Arthur Christopher, Edward Frederic and Robert Hugh – were one of the most extraordinary and prolific literary families, between them writing more than 150 books. Arthur alone left four million words of diary, although his most lasting legacy is the words to Elgar’s Land of Hope and Glory, while Fred is acknowledged as one of the finest writers of Edwardian supernatural fiction: the name E. F. Benson is mentioned in the same breath as other greats such as M. R. James and H. R. Wakefield.In fact, all three brothers wrote ghost stories, although the work of Arthur and Hugh in this field has long been overshadowed by their brother’s success. Now the best supernatural tales of A. C. and R. H. Benson have been gathered into one volume by anthologist Hugh Lamb, whose introduction examines the lives and writings of these two complex and fascinating men. Originally published between 1903 and 1927, the stories include A. C. Benson’s masterful ‘Basil Netherby’ and ‘The Uttermost Farthing’, and an intriguing article by R. H. Benson about real-life haunted houses.

Copyright (#ub7144a74-5945-5c9d-b42e-54d02844188e)

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Collins Chillers edition published 2018

First published in Great Britain by Ash-Tree Press 1996

Selection, introduction and notes © Hugh Lamb 2018

Cover design by Mike Topping © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Cover photographs © Shutterstock.com (http://www.Shutterstock.com)

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008249038

Ebook Edition © October 2018 ISBN: 9780008249045

Version: 2018-09-06

Dedication (#ub7144a74-5945-5c9d-b42e-54d02844188e)

To Sheil Bramdaw – good friend and great company.

Contents

Cover (#ub96de4bc-0e9e-52f7-8d58-d592e1600300)

Title Page (#u4392f530-1ac9-58a5-9fb1-8d956c4b5ce6)

Copyright (#ufc45cb54-ba82-54de-a266-ac4764f449d6)

Dedication (#u41104b0e-7c84-50ab-b9c7-85a9c2550af7)

Introduction (#u536e1197-6535-51f7-a596-ea874747fe73)

Out of the Sea (#u6c60d81e-7427-5452-a749-0f1e2e909434)

Mr Percival’s Tale (#u11dd838c-0e5d-5d0e-996d-fcd558c226dd)

The Traveller (#uf78f2267-f72b-500b-818d-cac9e2bcf57c)

Basil Netherby (#uafe6168d-4957-5d80-a4c5-0631c698d671)

Father Brent’s Tale (#u9a6e2f7d-6270-5324-bd98-e838c0003be4)

The Snake, the Leper and the Grey Frost (#litres_trial_promo)

Father Bianchi’s Story (#litres_trial_promo)

The Gray Cat (#litres_trial_promo)

Father Maddox’s Tale (#litres_trial_promo)

The Watcher (#litres_trial_promo)

The Hill of Trouble (#litres_trial_promo)

Haunted Houses (#litres_trial_promo)

The Uttermost Farthing (#litres_trial_promo)

Father Macclesfield’s Tale (#litres_trial_promo)

The Red Camp (#litres_trial_promo)

My Own Tale (#litres_trial_promo)

The Closed Window (#litres_trial_promo)

The Blood-Eagle (#litres_trial_promo)

The Slype House (#litres_trial_promo)

Father Meuron’s Tale (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Bibliography (#litres_trial_promo)

Footnotes (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Also in This Series (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

INTRODUCTION (#ub7144a74-5945-5c9d-b42e-54d02844188e)

No other family has approached the Bensons for sheer volume of printed words. Between them, Arthur Christopher Benson (1862–1925), Edward Frederic Benson (1867–1940) and Robert Hugh Benson (1871–1914) published over one hundred and fifty books, and their unpublished works include Arthur’s four-million word diary. Were that to be published in its entirety, it would occupy thirty-six volumes the size of this one.

Ghost stories formed the merest fraction of their output, yet they produced some of the finest in the genre, Fred becoming one of the best ghost story writers Britain has produced. But it was not without good cause that these three very different brothers – teacher, socialite and priest – found themselves producing literary terrors. Horror for the Bensons really began at home.

Arthur, Fred and Hugh were the surviving sons of Edward White Benson, one of Queen Victoria’s favourite Archbishops of Canterbury. Another son, Martin, died in his teens. The whole family was, to put it mildly, odd. To all appearances the epitome of an upper-class Victorian family, their history reads like a TV soap opera – a child bride, a ruthless patriarch, lesbianism, homosexuality, child death, religious mania and homicidal lunacy.

Edward Benson married Mary Sidgwick when she was eighteen (he’d had his eye on her since she was eleven). They produced six children, two of whom died young. The surviving daughter, Maggie, was to become totally insane and attempt to murder her mother, who was embroiled in a lesbian affair with one of Maggie’s friends.

The father became an ogre to his children, who spent much time in their copious autobiographical works trying to allay his ghost. None of them married and the Benson line died out with them.

With this gloriously dotty background, it is amazing that the brothers managed to keep both feet on the ground, though Arthur and Hugh had some alarming one-legged patches.

As Fred’s life is so well known, and his ghost stories very familiar and not included here, I do not propose to dwell on his career any more, but turn instead to his brothers, who are less familiar and still unjustly neglected.

Arthur became a schoolmaster, teaching first at Eton in 1892 and moving to Cambridge in 1903, where he rose to become Master of Magdalene College. He seems to have attracted some curious circumstances in his life. His main literary fame was founded on a string of books consisting of somewhat scholarly homilies, full of sweetness and light, which brought him a huge audience. One of his admiring readers was an anonymous American woman, wealthy in her own right, who had married an equally rich man. Touched by Benson’s description of the penury of Magdalene College, in 1915 she offered him, out of the blue, a large sum of money to improve the college. Understandably taken aback, Arthur eventually agreed, provided he was a trustee only, and over the next few years the American lady’s largesse enabled him to turn Magdalene into one of Cambridge’s leading colleges. Strange as it may seem, Benson and the American lady never met.

Arthur suffered from depression, often for years at a time, and this affliction was made doubly crippling for him as it was such depression that heralded his sister Maggie’s descent into madness (happily, not the case with Arthur). In one of his books, Fred recounts how Arthur, in the grip of depression, thought he had locked his servants into the house and that they would be starving to death. He urged Fred to investigate, but it was a baseless alarm: he had made provision for them and then forgotten all about it.

On a happier note, Arthur Benson is unwittingly celebrated every year at the Last Night of the Proms, when a rapturous audience bellows out his words to Elgar’s Pomp and Circumstance March No. 1, better known as Land of Hope and Glory.

Known to the world at large as the serene author of his rather sickly essays, he was in real life very big, very jovial and a born mickey-taker. His lifelong friend was M.R. James, our finest ghost story writer, and like Benson, large and inclined to a good laugh.

It is not unlikely that they both had a quiet snigger from time to time at the antics of Hugh Benson. He seemed to have found a good antidote to the Benson blues: religion. Despite being the son of the head of the Church of England, and being ordained by his father into that church, Hugh Benson turned to the Roman Catholic church and was ordained into that faith in 1904. He did well; he rose to become a private chamberlain to Pope Pius X in Rome, returning to England in 1914 when Pius died (and dying himself soon after).

While Arthur was happy with his small Cambridge circle, Hugh Benson became famous as a public speaker and went on tours preaching the faith all around the world. He was a fiery convert indeed – as is shown in his ghost stories – and his passion for all things Catholic is perhaps the greatest flaw in his writing. He was not without human failings: he became involved with the unsavoury Frederick Rolfe (Baron Corvo). The fascination of this seedy character is hard to understand, yet he excites the interest of writers to this day. Rolfe latched on to Benson as Hugh was a Catholic priest and a famous author – the two things Rolfe most coveted – and a plan to write a book together was to turn sour in the extreme. For reasons not too clear at this late date, but more to do with Rolfe’s lack of balance than Benson’s lack of judgement, the project fell through. Rolfe saw this as one more stage in his imagined persecution by the Catholic church, and the result was a very long hate campaign against all the Bensons. Rolfe was quite prepared to include the odd brother or two in his war against Hugh, and both Fred and Arthur got vitriolic letters from him.

Like Fred, Arthur and Hugh wrote extensively and sold well. They may not have matched their brother’s output, or achieved his more enduring fame, but he had more time on his hands than they did.

Arthur churned out his books of essays and a few novels; he edited Queen Victoria’s letters for publication; and he produced books of Benson family autobiography and biography, including a book each on his father, Hugh Benson and Maggie Benson.

Hugh wrote books on religious practice and thought; some novels, both historic and prophetic, with lots of religion included; and contributed to the Benson catalogue of family history. For a line which died out, the Bensons left behind a vast amount of personal history which makes interesting reading now. There is certainly much left unwritten which would make even more interesting reading; and it should never be forgotten that the Bensons were supreme self-publicists – we read what they wanted us to know and nothing more, true or not.

And all three of them wrote ghost stories. Their individual aims in writing them, however, varied enormously. Fred wrote his for money and entertainment. Arthur wrote his, in the main, as allegorical tales for his pupils, and kept fairly private some darker stories that were only published after his death. Hugh wrote his as glorifications, often unctuous, of his new Catholic faith. That Arthur and Hugh managed to produce such good material despite all this speaks worlds for their talent.

The family and its background provided much overt influence. For instance, all three brothers wrote of rooms in towers: Fred in the title story of his 1912 collection, Arthur in ‘The Closed Window’, and Hugh in ‘Father Maddox’s Tale’. The tower room was a feature of their home in Truro, Lis Escop, when Edward Benson was Bishop of Truro from 1877 to 1882.

Fred Benson was by far and away the most successful ghost story writer of the three and was not interested in moral lessons or religious tracts. He wrote his stories to frighten, and said so. Yet Arthur’s and Hugh’s stories contain some pretty scary stuff, and if Arthur wrote his for his pupils, they must have had a few nasty moments when he read them aloud. Hugh seems to frighten us almost in spite of himself at times.

Arthur had met M.R. James in 1873, when they were both pupils at Temple Grove School, East Sheen (the setting for MRJ’s ‘A School Story’), and they stayed close friends until Benson’s death. Arthur would sit in on James’s Christmas readings of his stories, with friends such as Herbert Tatham, E.G. Swain and Arthur Gray, all of whom also wrote ghost stories. James’s influence on this genre is quite remarkable; it is possible to trace his influence in the work of over sixty writers.

While neither Benson nor James overtly copied each other, there are some interesting parallels. In ‘The Uttermost Farthing’, Benson introduces a phantom that could have stepped from the pages of James. ‘The Red Camp’ bears an interesting resemblance in tone to MRJ’s later work ‘A Warning to the Curious’, where archaeological treasure hunting brings a grim reward.

Arthur’s published ghost stories were written to entertain his pupils, and collected into book form later. One of his Eton pupils, E.H. Ryle, has described a typical Benson reading:

We used to assemble in his dark and deserted study … exactly at the appointed moment [Benson] would emerge from his writing room … He would turn up the light in a green-shaded reading lamp on a little table, bury himself in his great, deep armchair … and then, in a low, conversational tone of voice, he would narrate an absorbing tale. I loved those Sunday evenings. The darkened room, the little pool of light … a silence which could be felt, the blurred outline of the huddled-up figure of the big man, the quiet, even flow of words …

Considering the still sharp scenes of terror in some of those stories, that ‘low, conversational tone’ of Benson must have caused quite a few nightmares! These stories for his pupils were collected into two volumes, The Hill of Trouble (1903) and The Isles of Sunset (1905).

Another book of A.C. Benson stories had quite a different origin. When Arthur joined in James’s reading sessions, he would contribute one or two himself. We know of at least one by name, ‘The House at Trehele’, which Benson read out in 1903. When Arthur died, E.F. Benson went through his papers and came across a file of ghost stories. He quite liked the look of two of them and duly got them published by one of his own publishers, Hutchinson, in January 1927 (under the dreadfully nondescript title Basil Netherby, which might explain the volume’s neglect since). The title story was a renamed ‘The House at Trehele’. There is no record of what happened to the others.

Arthur Benson suffered from extraordinary dreams all his life, extraordinary both in their content and the clarity with which he recalled them, and described some in his diary. He dreamed of an execution: ‘A man with an axe cut pretty deep into [Lord Morton’s] neck. I saw into the cut, it was like a currant tart.’ Then he had this vision some years later:

… a terrible dream of the hanging of some person nearly related to me at Eton; the scaffold, draped with black, stood in Brewer’s Yard; and I can’t describe the speechless horror with which I watched little black swing-doors in it push open at intervals, and faces look out. The last scene was very terrible … the prisoner stood close to me … I could see his face twitch and grow suddenly pale. When the long prayers were over, he got up and ran to the scaffold, as if glad to be gone. He was pulled in at one of the swing-doors – and there was a silence. Then a thing like a black semaphore went down on the top of the scaffold – (which was nothing but a great tall thing entirely covered with black cloth) – and loud thumps and kicks were heard inside, against the boards, which made me feel sick.

There is an odd little essay by Benson in his book Escape (1915) which merits a mention. In ‘The Visitant’ he tells of a recurring vision of a house and its occupants. He can see them and the rooms with great clarity, but is unable to see past some doors or into the hall or passage. It is not sinister in itself but it does bear an uncanny resemblance to the recurring dream in E.F. Benson’s ‘The Room in the Tower’. Fred was not averse to the occasional lifting of his brother’s material, as with The Luck of the Vails.

E.H. Ryle recalled that ‘shortly after its publication in 1903 I started to read The Luck of the Vails, by E.F. Benson, my Tutor’s brother. I wondered why it seemed familiar, and then it flashed upon me that the story, no doubt in a less elaborate form, had been spun out to us on the ten or eleven Sunday evenings of (I think) the winter half of 1899–1900. I imagine that A.C.B., after realising the pleasure it had given to a youthful audience, passed on the plot to E.F.B. – but I write subject to correction.’

It would seem that Arthur Benson wrote no more ghost stories for publication that we know of. He did write a mildly interesting novel, The Child of the Dawn (1912), dealing loosely with reincarnation. Its significance here lies in its introducing, in the midst of the hero’s wanderings in the afterlife, the unnamed figure of Herbert Tatham, a fellow ghost story writer of Benson, and his greatest friend, who had died in 1909, and to whom the novel was dedicated. According to Hugh Macnaghten, Eton Vice-Provost at the time of Arthur’s death, Herbert Tatham suggested the plot of ‘The Gray Cat’ to Benson.

It was Arthur’s ‘pupil’ stories that inspired Hugh Benson to try his luck at ghost story writing, albeit of a much more different sort. He records that he started writing the stories in The Light Invisible (1903) in the summer of 1902 and that they were of a semi-mystical and imaginative nature. They were that all right, but more besides. Purporting to be the narratives of an old priest and the writer himself, the fifteen tales vary wildly from genuinely creepy stories, such as ‘The Traveller’, to quite unpalatable religious maunderings. One story, which I have not included here, invites us to witness a spiritual being pushing a child under a horse and cart as evidence of God’s love for humanity. If Benson’s religious convictions led him in this direction, we can only be grateful he never wrote any more stories for that volume.

The book was nonetheless a huge success, being reprinted nine times within four years of its first appearance in March 1903. Hugh’s religious leanings deprived him of the enormous royalties that flowed from all this. At the time he wrote and published the book, he was a member of the Community of the Resurrection, a religious order based near Bradford. As such, he was obliged to donate to the order all his worldly goods – book royalties and all!

His other book of ghost stories, A Mirror of Shalott (1907), was a different kettle of fish altogether. It was the book form of a set of stories he had published over the years in the Ecclesiastical Review and the Catholic Fireside, which purported to be stories told by a group of priests in Rome. Stronger than the earlier book, A Mirror of Shalott suffers in large part from a bit too much Catholicism, but makes up for it with some genuinely scary tales. ‘Father Meuron’s Story’ is an old favourite with editors, and ‘My Own Tale’ is not without reprinting over the years, but in the main, the stories used here should be refreshingly unfamiliar.

His only other essay in the supernatural is the novel The Necromancers (1909), an openly stated warning against the dangers of Spiritualism, which has been reprinted in paperback in the past forty years. I think it is also the only piece of work by A.C. or R.H. Benson to be dramatised in any form: it was filmed in 1940 under the title Spellbound, directed by John Harlow and featuring Derek Farr and Vera Lindsay. The film has also been titled Passing Clouds and The Spell of Amy Nugent.

Hugh Benson was also interested in real-life hauntings, as shown by his article ‘Haunted Houses’, written for the Pall Mall Magazine, January 1913. He takes the view that it would be foolish to ignore what he calls the ‘overwhelming’ weight of human evidence for haunted houses; an eminently satisfactory attitude for a ghost story writer. The article has not been reprinted since it first appeared, and makes an interesting counterpoint to Hugh Benson’s fictional ghost stories.

It is surprising that the E.F. Benson revival of the past thirty years has not sparked interest in the work of his brothers. All three were best sellers and all three wrote equally interesting ghost stories (though perhaps not equally entertaining). I hope this selection from Arthur Benson and Robert Hugh Benson will help restore them to their rightful place in the history of the English ghost story.

Hugh Lamb

Sutton, Surrey

January 2018

OUT OF THE SEA (#ub7144a74-5945-5c9d-b42e-54d02844188e)

A.C. Benson

It was about ten of the clock on a November morning in the little village of Blea-on-the-Sands. The hamlet was made up of some thirty houses, which clustered together on a low rising ground. The place was very poor, but some old merchant of bygone days had built in a pious mood a large church, which was now too great for the needs of the place; the nave had been unroofed in a heavy gale, and there was no money to repair it, so that it had fallen to decay, and the tower was joined to the choir by roofless walls. This was a sore trial to the old priest, Father Thomas, who had grown grey there; but he had no art in gathering money, which he asked for in a shamefaced way; and the vicarage was a poor one, hardly enough for the old man’s needs. So the church lay desolate.

The village stood on what must once have been an island; the little river Reddy, which runs down to the sea, there forking into two channels on the landward side; towards the sea the ground was bare, full of sand-hills covered with a short grass. Towards the land was a small wood of gnarled trees, the boughs of which were all brushed smooth by the gales; looking landward there was the green flat, in which the river ran, rising into low hills; hardly a house was visible save one or two lonely farms; two or three church towers rose above the hills at a long distance away. Indeed Blea was much cut off from the world; there was a bridge over the stream on the west side, but over the other channel was no bridge, so that to fare eastward it was requisite to go in a boat. To seaward there were wide sands, when the tide was out; when it was in, it came up nearly to the end of the village street. The people were mostly fishermen, but there were a few farmers and labourers; the boats of the fishermen lay to the east side of the village, near the river channel which gave some draught of water; and the channel was marked out by big black stakes and posts that straggled out over the sands, like awkward leaning figures, to the sea’s brim.

Father Thomas lived in a small and ancient brick house near the church, with a little garden of herbs attached. He was a kindly man, much worn by age and weather, with a wise heart, and he loved the quiet life with his small flock. This morning he had come out of his house to look abroad, before he settled down to the making of his sermon. He looked out to sea, and saw with a shadow of sadness the black outline of a wreck that had come ashore a week before, and over which the white waves were now breaking. The wind blew steadily from the north-east, and had a bitter poisonous chill in it, which it doubtless drew from the fields of the upper ice. The day was dark and overhung, not with cloud, but with a kind of dreary vapour that shut out the sun. Father Thomas shuddered at the wind, and drew his patched cloak round him. As he did so, he saw three figures come up to the vicarage gate. It was not a common thing for him to have visitors in the morning, and he saw with surprise that they were old Master John Grimston, the richest man in the place, half farmer and half fisherman, a dark surly old man; his wife, Bridget, a timid and frightened woman, who found life with her harsh husband a difficult business, in spite of their wealth, which, for a place like Blea, was great; and their son Henry, a silly shambling man of forty, who was his father’s butt. The three walked silently and heavily, as though they came on a sad errand.

Father Thomas went briskly down to meet them, and greeted them with his accustomed cheerfulness. ‘And what may I do for you?’ he said. Old Master Grimston made a sort of gesture with his head as though his wife should speak; and she said in a low and somewhat husky voice, with a rapid utterance, ‘We have a matter, Father, we would ask you about – are you at leisure?’ Father Thomas said, ‘Ay, I am ashamed to be not more busy! Let us go within the house.’ They did so; and even in the little distance to the door, the Father thought that his visitors behaved themselves very strangely. They peered round from left to right, and once or twice Master Grimston looked sharply behind them, as though they were followed. They said nothing but ‘Ay’ and ‘No’ to the Father’s talk, and bore themselves like people with a sore fear on their backs. Father Thomas made up his mind that it was some question of money, for nothing else was wont to move Master Grimston’s mind. So he had them into his parlour and gave them seats, and then there was a silence, while the two men continued to look furtively about them, and the goodwife sate with her eyes upon the priest’s face. Father Thomas knew not what to make of this, till Master Grimston said harshly, ‘Come wife, tell the tale and make an end; we must not take up the Father’s time.’

‘I hardly know how to say it, Father,’ said Bridget, ‘but a strange and evil thing has befallen us; there is something come to our house, and we know not what it is – but it brings a fear with it.’ A sudden paleness came over her face, and she stopped, and the three exchanged a glance in which terror was visibly written. Master Grimston looked over his shoulder swiftly, and made as though to speak, yet only swallowed in his throat; but Henry said suddenly, in a loud and woeful voice, ‘It is an evil beast out of the sea.’ And then there followed a dreadful silence, while Father Thomas felt a sudden fear leap up in his heart, at the contagion of fear that he saw written on the faces round him. But he said with all the cheerfulness he could muster, ‘Come, friends, let us not begin to talk of sea-beasts; we must have the whole tale. Mistress Grimston, I must hear the story – be content – nothing can touch us here.’ The three seemed to draw a faint content from his words, and Bridget began:

‘It was the day of the wreck, Father. John was up betimes before the dawn; he walked out early to the sands, and Henry with him – and they were the first to see the wreck – was not that it?’ At these words the father and son seemed to exchange a very swift and secret look, and both grew pale. ‘John told me there was a wreck ashore, and they went presently and roused the rest of the village; and all that day they were out, saving what could be saved. Two sailors were found, both dead and pitifully battered by the sea, and they were buried, as you know, Father, in the churchyard next day; John came back about dusk and Henry with him, and we sate down to our supper. John was telling me about the wreck, as we sate beside the fire, when Henry, who was sitting apart, rose up and cried out suddenly, “What is that?”’

She paused for a moment, and Henry, who sate with face blanched, staring at his mother, said, ‘Ay, did I – it ran past me suddenly.’ ‘Yes, but what was it?’ said Father Thomas trying to smile; ‘a dog or cat, methinks?’ ‘It was a beast,’ said Henry slowly, in a trembling voice – ‘a beast about the bigness of a goat. I never saw the like – yet I did not see it clear; I but felt the air blow, and caught a whiff of it – it was salt like the sea, but with a kind of dead smell behind.’ ‘Was that all you saw?’ said Father Thomas; ‘Belike you were tired and faint, and the air swam round you suddenly – I have known the like myself when weary.’ ‘Nay, nay,’ said Henry, ‘this was not like that – it was a beast, sure enough.’ ‘Ay, and we have seen it since,’ said Bridget. ‘At least I have not seen it clearly yet, but I have smelt its odour, and it turns me sick – but John and Henry have seen it often – sometimes it lies and seems to sleep, but it watches us; and again it is merry, and will leap in a corner – and John saw it skip upon the sands near the wreck – did you not, John?’ At these words the two men again exchanged a glance, and then old Master Grimston, with a dreadful look in his face, in which great anger seemed to strive with fear, said ‘Nay, silly woman, it was not near the wreck, it was out to the east.’ ‘It matters little,’ said Father Thomas, who saw well enough this was no light matter. ‘I never heard the like of it. I will myself come down to your house with a holy book, and see if the thing will meet me. I know not what this is,’ he went on, ‘whether it is a vain terror that hath hold of you; but there be spirits of evil in the world, though much fettered by Christ and his Saints – we read of such in Holy Writ – and the sea, too, doubtless hath its monsters; and it may be that one hath wandered out of the waves, like a dog that hath strayed from his home. I dare not say, till I have met it face to face. But God gives no power to such things to hurt those who have a fair conscience.’ – And here he made a stop and looked at the three; Bridget sate regarding him with hope in her face; but the other two sate peering upon the ground; and the priest divined in some secret way that all was not well with them. ‘But I will come at once,’ he said, rising, ‘and I will see if I can cast out or bind the thing, whatever it be – for I am in this place as a soldier of the Lord, to fight with works of darkness.’ He took a clasped book from a table, and lifted up his hat, saying, ‘Let us set forth.’ Then he said as they left the room, ‘Hath it appeared today?’ ‘Yes, indeed,’ said Henry, ‘and it was ill content. It followed us as though it were angered.’ ‘Come,’ said Father Thomas, turning upon him, ‘you speak thus of a thing, as you might speak of a dog – what is it like?’ ‘Nay,’ said Henry, ‘I know not; I can never see it clearly; it is like a speck in the eye – it is never there when you look upon it – it glides away very secretly; it is most like a goat, I think. It seems to be horned, and hairy; but I have seen its eyes, and they were yellow, like a flame.’

As he said these words Master Grimston went in haste to the door, and pulled it open as though to breathe the air. The others followed him and went out; but Master Grimston drew the priest aside, and said like a man in a mortal fear, ‘Look you, Father, all this is true – the thing is a devil – and why it abides with us I know not; but I cannot live so; and unless it be cast out it will slay me – but if money be of avail, I have it in abundance.’ ‘Nay,’ said Father Thomas, ‘let there be no talk of money – perchance if I can aid you, you may give of your gratitude to God.’ ‘Ay, ay,’ said the old man hurriedly, ‘that was what I meant – there is money in abundance for God, if he will but set me free.’

So they walked very sadly together through the street. There were few folk about; the men and the children were all abroad – a woman or two came to the house doors, and wondered a little to see them pass so solemnly, as though they followed a body to the grave.

Master Grimston’s house was the largest in the place. It had a walled garden before it, with a strong door set in the wall. The house stood back from the road, a dark front of brick with gables; behind it the garden sloped nearly to the sands, with wooden barns and warehouses. Master Grimston unlocked the door, and then it seemed that his terrors came over him, for he would have the priest enter first. Father Thomas, with a certain apprehension of which he was ashamed, walked quickly in, and looked about him. The herbage of the garden had mostly died down in the winter, and a tangle of sodden stalks lay over the beds. A flagged path edged with box led up to the house, which seemed to stare at them out of its dark windows with a sort of steady gaze. Master Grimston fastened the door behind them, and they went all together, keeping close one to another, up to the house, the door of which opened upon a big parlour or kitchen, sparely furnished, but very clean and comfortable. Some vessels of metal glittered on a rack. There were chairs, ranged round the open fireplace. There was no sound except that the wind buffeted in the chimney. It looked a quiet and homely place, and Father Thomas grew ashamed of his fears. ‘Now,’ said he in his firm voice, ‘though I am your guest here, I will appoint what shall be done. We will sit here together, and talk as cheerfully as we may, till we have dined. Then, if nothing appears to us,’ – and he crossed himself – ‘I will go round the house, into every room, and see if we can track the thing to its lair; then I will abide with you till evensong; and then I will soon return, and sleep here tonight. Even if the thing be wary, and dares not to meet the power of the Church in the daytime, perhaps it will venture out at night; and I will even try a fall with it. So come, good people, and be comforted.’

So they sate together; and Father Thomas talked of many things, and told some old legends of saints; and they dined, though without much cheer; and still nothing appeared. Then, after dinner, Father Thomas would view the house. So he took his book up, and they went from room to room. On the ground floor there were several chambers not used, which they entered in turn, but saw nothing; on the upper floor was a large room where Master Grimston and his wife slept; and a further room for Henry, and a guest-chamber in which the priest was to sleep if need was; and a room where a servant-maid slept. And now the day began to darken and to turn to evening, and Father Thomas felt a shadow grow in his mind. There came into his head a verse of Scripture about a spirit who found a house ‘empty, swept and garnished’, and called his fellows to enter in.

At the end of the passage was a locked door; and Father Thomas said, ‘This is the last room – let us enter.’ ‘Nay, there is no need to do that,’ said Master Grimston in a kind of haste; ‘it leads nowhither – it is but a room of stores.’ ‘It were a pity to leave it unvisited,’ said the Father – and as he said the word, there came a kind of stirring from within. ‘A rat, doubtless,’ said the Father, striving with a sudden sense of fear; but the pale faces round him told another tale. ‘Come, Master Grimston, let us be done with this,’ said Father Thomas decisively; ‘the hour of vespers draws nigh.’ So Master Grimston slowly drew out a key and unlocked the door, and Father Thomas marched in. It was a simple place enough. There were shelves on which various household matters lay, boxes and jars, with twine and cordage. On the ground stood chests. There were some clothes hanging on pegs, and in a corner was a heap of garments, piled up. On one of the chests stood a box of rough deal, and from the corner of it dripped water, which lay in a little pool on the floor. Master Grimston went hurriedly to the box and pushed it further to the wall. As he did so, a kind of sound came from Henry’s lips. Father Thomas turned and looked at him; he stood pale and strengthless, his eyes fixed on the corner – at the same moment something dark and shapeless seemed to slip past the group, and there came to the nostrils of Father Thomas a strange sharp smell, as of the sea, only that there was a taint within it, like the smell of corruption.

They all turned and looked at Father Thomas together, as though seeking a comfort from his presence. He, hardly knowing what he did, and in the grasp of a terrible fear, fumbled with his book; and opening it, read the first words that his eye fell upon, which was the place where the Blessed Lord, beset with enemies, said that if He did but pray to His Father, He should send Him forthwith legions of angels to encompass Him. And the verse seemed to the priest so like a message sent instantly from heaven that he was not a little comforted.

But the thing, whatever the reason was, appeared to them no more at that time. Yet the thought of it lay very heavy on Father Thomas’s heart. In truth he had not in the bottom of his mind believed that he would see it, but had trusted in his honest life and his sacred calling to protect him. He could hardly speak for some minutes, – moreover the horror of the thing was very great – and seeing him so grave, their terrors were increased, though there was a kind of miserable joy in their minds that some one, and he a man of high repute, should suffer with them.

Then Father Thomas, after a pause – they were now in the parlour – said, speaking very slowly, that they were in a sore affliction of Satan, and that they must withstand him with a good courage – ‘And look you,’ he added, turning with a great sternness to the three, ‘if there be any mortal sin upon your hearts, see that you confess it and be shriven speedily – for while such a thing lies upon the heart, so long hath Satan power to hurt – otherwise have no fear at all.’

Then Father Thomas slipped out to the garden, and hearing the bell pulled for vespers, he went to the church, and the three would go with him, because they would not be left alone. So they went together; by this time the street was fuller, and the servant-maid had told tales, so that there was much talk in the place about what was going forward. None spoke with them as they went, but at every corner you might see one check another in talk, a silence fall upon a group, so that they knew that their terrors were on every tongue. There was but a handful of worshippers in the church, which was dark, save for the light on Father Thomas’s book. He read the holy service swiftly and courageously, but his face was very pale and grave in the light of the candle. When the vespers were over, and he had put off his robe, he said that he would go back to his house, and gather what he needed for the night, and that they should wait for him at the churchyard gate. So he strode off to his vicarage. But as he shut to the door, he saw a dark figure come running up the garden; he waited with a fear in his mind, but in a moment he saw that it was Henry, who came up breathless, and said that he must speak with the Father alone. Father Thomas knew that somewhat dark was to be told him. So he led Henry into the parlour and seated himself, and said, ‘Now, my son, speak boldly.’ So there was an instant’s silence, and Henry slipped on to his knees.

Then in a moment Henry with a sob began to tell his tale. He said that on the day of the wreck his father had roused him very early in the dawn, and had told him to put on his clothes and come silently, for he thought there was a wreck ashore. His father carried a spade in his hand, he knew not then why. They went down to the tide, which was moving out very fast, and left but an inch or two of water on the sands. There was but a little light, but, when they had walked a little, they saw the black hull of a ship before them, on the edge of the deeper water, the waves driving over it; and then all at once they came upon the body of a man lying on his face on the sand. There was no sign of life in him, but he clasped a bag in his hand that was heavy, and the pocket of his coat was full to bulging; and there lay, moreover, some glittering things about him that seemed to be coins. They lifted the body up, and his father stripped the coat off from the man, and then bade Henry dig a hole in the sand, which he presently did, though the sand and water oozed fast into it. Then his father, who had been stooping down, gathering somewhat up from the sand, raised the body up, and laid it in the hole, and bade Henry cover it. And so he did till it was nearly hidden. Then came a horrible thing; the sand in the hole began to move and stir, and presently a hand was put out with clutching fingers; and Henry had dropped the spade, and said, ‘There is life in him,’ but his father seized the spade, and shovelled the sand into the hole with a kind of silent fury, and trampled it over and smoothed it down – and then he gathered up the coat and the bag, and handed Henry the spade. By this time the town was astir, and they saw, very faintly, a man run along the shore eastward; so, making a long circuit to the west, they returned; his father had put the spade away and taken the coat upstairs; and then he went out with Henry, and told all he could find that there was a wreck ashore.

The priest heard the story with a fierce shame and anger, and turning to Henry he said, ‘But why did you not resist your father, and save the poor sailor?’ ‘I dared not,’ said Henry shuddering, ‘though I would have done so if I could; but my father has a power over me, and I am used to obey him.’ Then said the priest, ‘This is a dark matter. But you have told the story bravely, and now will I shrive you, my son.’ So he gave him shrift. Then he said to Henry, ‘And have you seen aught that would connect the beast that visits you with this thing?’ ‘Ay, that I have,’ said Henry, ‘for I watched it with my father skip and leap in the water over the place where the man lies buried.’ Then the priest said, ‘Your father must tell me the tale too, and he must make submission to the law.’ ‘He will not,’ said Henry. ‘Then I will compel him,’ said the priest. ‘Not out of my mouth,’ said Henry, ‘or he will slay me too.’ And then the priest said that he was in a strait place for he could not use the words of confession of one man to convict another of his sin. So he gathered his things in haste, and walked back to the church; but Henry went another way, saying, ‘I made excuse to come away, and said I went elsewhere; but I fear my father much – he sees very deep; and I would not have him suspect me of having made confession.’

Then the Father met the other two at the church gate; and they went down to the house in silence, the Father pondering heavily; and at the door Henry joined them, and it seemed to the Father that old Master Grimston regarded him not. So they entered the house in silence, and ate in silence, listening earnestly for any sound. And the Father looked oft on Master Grimston, who ate and drank and said nothing, never raising his eyes. But once the Father saw him laugh secretly to himself, so that the blood came cold in the Father’s veins, and he could hardly contain himself from accusing him. Then the Father had them to prayers, and prayed earnestly against the evil, and that they should open their hearts to God, if he would show them why this misery came upon them.

Then they went to bed; and Henry asked that he might lie in the priest’s room, which he willingly granted. And so the house was dark, and they made as though they would sleep; but the Father could not sleep, and he heard Henry weeping silently to himself like a little child.

But at last the Father slept – how long he knew not – and suddenly brake out of his sleep with a horror of darkness all about him, and knew that there was some evil thing abroad. He looked upon the room. He heard Henry mutter heavily in his sleep as though there was a dark terror upon him; and then, in the light of the dying embers, the Father saw a thing rise upon the hearth, as though it had slept there, and woken to stretch itself. And then in the half-light it seemed softly to gambol and play; but whereas when an innocent beast does this it seems a fond and pretty sight, the Father thought he had never seen so ugly a sight as the beast gambolling all by itself, as if it could not contain its own dreadful joy; it looked viler and more wicked every moment; then, too, there spread in the room the sharp scent of the sea, with the foul smell underneath it, that gave the Father a deadly sickness; he tried to pray, but no words would come, and he felt indeed that the evil was too strong for him. Presently the beast desisted from its play, and looking wickedly about it, came near to the Father’s bed, and seemed to put up its hairy forelegs upon it; he could see its narrow and obscene eyes, which burned with a dull yellow light, and were fixed upon him. And now the Father thought that his end was near, for he could stir neither hand nor foot, and the sweat rained down his brow; but he made a mighty effort, and in a voice which shocked himself, so dry and husky and withal of so loud and screaming a tone it was, he said three holy words. The beast gave a great quiver of rage, but it dropped down on the floor, and in a moment was gone. Then Henry woke, and raising himself on his arm, said somewhat; but there broke out in the house a great outcry and the stamping of feet, which seemed very fearful in the silence of the night. The priest leapt out of his bed all dizzy, and made a light, and ran to the door, and went out, crying whatever words came to his head. The door of Master Grimston’s room was open, and a strange and strangling sound came forth; the Father made his way in, and found Master Grimston lying upon the floor, his wife bending over him; he lay still, breathing pitifully, and every now and then a shudder ran through him. In the room there seemed a strange and shadowy tumult going forward; but the Father saw that no time could be lost, and kneeling down beside Master Grimston, he prayed with all his might.

Presently Master Grimston ceased to struggle and lay still, like a man who had come out of a sore conflict. Then he opened his eyes, and the Father stopped his prayers, and looking very hard at him he said, ‘My son, the time is very short – give God the glory.’ Then Master Grimston, rolling his haggard eyes upon the group, twice strove to speak and could not; but the third time the Father, bending down his head, heard him say in a thin voice, that seemed to float from a long way off, ‘I slew him … my sin.’ Then the Father swiftly gave him shrift, and as he said the last word, Master Grimston’s head fell over on the side, and the Father said, ‘He is gone.’ And Bridget broke out into a terrible cry, and fell upon Henry’s neck, who had entered unseen.

Then the Father bade him lead her away, and put the poor body on the bed; as he did so he noticed that the face of the dead man was strangely bruised and battered, as though it had been stamped upon by the hoofs of some beast. Then Father Thomas knelt, and prayed until the light came filtering in through the shutters and the cocks crowed in the village, and presently it was day. But that night the Father learnt strange secrets, and something of the dark purpose of God was revealed to him.

In the morning there came one to find the priest, and told him that another body had been thrown up on the shore, which was strangely smeared with sand, as though it had been rolled over and over in it; and the Father took order for its burial.

Then the priest had long talk with Bridget and Henry. He found them sitting together, and she held her son’s hand and smoothed his hair, as though he had been a little child; and Henry sobbed and wept, but Bridget was very calm. ‘He hath told me all,’ she said, ‘and we have decided that he shall do whatever you bid him; must he be given to justice?’ and she looked at the priest very pitifully. ‘Nay, nay,’ said the priest. ‘I hold not Henry to account for the death of the man; it was his father’s sin, who hath made heavy atonement – the secret shall be buried in our hearts.’

Then Bridget told him how she had waked suddenly out of her sleep, and heard her husband cry out; and that then followed a dreadful kind of struggling, with the scent of the sea over all; and then he had all at once fallen to the ground and she had gone to him – and that then the priest had come.

Then Father Thomas said with tears that God had shown them deep things and visited them very strangely; and they would henceforth live humbly in His sight, showing mercy.

Then lastly he went with Henry to the store-room; and there, in the box that had dripped with water, lay the coat of the dead man, full of money, and the bag of money too; and Henry would have cast it back into the sea, but the priest said that this might not be, but that it should be bestowed plentifully upon shipwrecked mariners unless the heirs should be found. But the ship appeared to be a foreign ship, and no search ever revealed whence the money had come, save that it seemed to have been violently come by.

Master Grimston was found to have left much wealth. But Bridget sold the house and the land, and it mostly went to rebuild the church to God’s glory. Then Bridget and Henry moved to the vicarage and served Father Thomas faithfully, and they guarded their secret. And beside the nave is a little high turret built, where burns a lamp in a lantern at the top, to give light to those at sea.

Now the beast troubled those of whom I write no more; but it is easier to raise up evil than to lay it; and there are those that say that to this day that a man or a woman with an evil thought in their hearts may see on a certain evening in November, at the ebb of the tide, a goatlike thing wade in the water, snuffing at the sand, as though it sought but found not. But of this I know nothing.

MR PERCIVAL’S TALE (#ub7144a74-5945-5c9d-b42e-54d02844188e)

R.H. Benson

When I came in from Mass into the refectory one morning, I found a layman breakfasting there with the Father Rector. We were introduced to one another, and I learned that Mr Percival was a barrister who had arrived from England that morning on a holiday and was to stay at S. Filippo for a fortnight.

I yield to none in my respect for the clergy; at the same time a layman feels occasionally something of a pariah among them: I suppose this is bound to be so; so I was pleased then to find another dog of my breed with whom I might consort, and even howl, if I so desired. I was pleased, too, with his appearance. He had that trim academic air that is characteristic of the Bar, in spite of his twenty-two hours journey; and was dressed in an excellently made grey suit. He was very slightly bald on his forehead, and had those sharp-cut mask-like features that mark a man as either lawyer, priest, or actor; he had besides delightful manners and even, white teeth. I do not think I could have suggested any improvements in person, behaviour, or costume.

By the time that my coffee had arrived, the Father Rector had run dry of conversation and I could see that he was relieved when I joined in.

In a few minutes I was telling Mr Percival about the symposium we had formed for the relating of preternatural adventures; and I presently asked him whether he had ever had any experience of the kind.

He shook his head.

‘I have not,’ he said in his virile voice; ‘my business takes my time.’

‘I wish you had been with us earlier,’ put in the Rector. ‘I think you would have been interested.’

‘I am sure of it,’ he said. ‘I remember once – but you know, Father, frankly I am something of a sceptic.’

‘You remember—?’ I suggested.

He smiled very pleasantly with eyes and mouth.

‘Yes, Mr Benson; I was once next door to such a story. A friend of mine saw something; but I was not with him at the moment.’

‘Well; we thought we had finished last night,’ I said, ‘but do you think you would be too tired to entertain us this evening?’

‘I shall be delighted to tell the story,’ he said easily. ‘But indeed I am a sceptic in this matter; I cannot dress it up.’

‘We want the naked fact,’ I said.

I went sight-seeing with him that day; and found him extremely intelligent and at the same time accurate. The two virtues do not run often together; and I felt confident that whatever he chose to tell us would be salient and true. I felt, too, that he would need few questions to draw him out; he would say what there was to be said unaided.

When we had taken our places that night, he began by again apologising for his attitude of mind.

‘I do not know, Reverend Fathers,’ he said, ‘what are your own theories in this matter; but it appears to me that if what seems to be preternatural can possibly be brought within the range of the natural, one is bound scientifically to treat it in that way. Now in this story of mine – for I will give you a few words of explanation first in order to prejudice your minds as much as possible – in this story the whole matter might be accounted for by the imagination. My friend who saw what he saw was under rather theatrical circumstances, and he is an Irishman. Besides that, he knew the history of the place in which he was; and he was quite alone. On the other hand, he has never had an experience of the kind before or since; he is perfectly truthful, and he saw what he saw in moderate daylight. I give you these facts first, and I think you would be perfectly justified in thinking they account for everything. As for my own theory, which is not quite that, I have no idea whether you will agree or disagree with it. I do not say that my judgment is the only sensible one, or anything offensive like that. I merely state what I feel I am bound to accept for the present.’

There was a murmur of assent. Then he crossed his legs, leaned back and began:

‘In my first summer after I was called to the Bar I went down South Wales for a holiday with another man who had been with me at Oxford. His name was Murphy: he is a J.P. now, in Ireland, I think. I cannot think why we went to South Wales; but there it is: we did.

‘We took the train to Cardiff; sent on our luggage up the Taff Valley to an inn of which I cannot remember the name; but it was close to where Lord Bute has a vineyard. Then we walked up to Llandaff, saw St Tylo’s tomb; and went on again to this village.

‘Next morning we thought we would look about us before going on; and we went out for a stroll. It was one of the most glorious mornings I ever remember, quite cloudless and very hot; and we went up through woods to get a breeze at the top of the hill.

‘We found that the whole place was full of iron mines, disused now, as the iron is richer further up the country; but I can tell you that they enormously improved the interest of the place. We found shaft after shaft, some protected and some not, but mostly overgrown with bushes, so we had to walk carefully. We had passed half-a-dozen, I should think, before the thought of going down one of them occurred to Murphy.

‘Well, we got down one at last; though I rather wished for a rope once or twice; and I think it was one of the most extraordinary sights I have ever seen. You know perhaps what the cave of a demon-king is like, in the first act of a pantomime. Well, it was like that. There was a kind of blue light that poured down the shafts, refracted from surface to surface; so that the sky was invisible. On all sides passages ran into total darkness; huge reddish rocks stood out fantastically everywhere in the pale light; there was a sound of water falling into a pool from a great height and presently, striking matches as we went, we came upon a couple of lakes of marvellously clear blue water through which we could see the heads of ladders emerging from other black holes of unknown depth below.

‘We found our way out after a while into what appeared to be the central hall of the mine. Here we saw plain daylight again, for there was an immense round opening at the top, from the edges of which curved away the sides of the shaft, forming a huge circular chamber.

‘Imagine the Albert Hall roofless; or better still, imagine Saint Peter’s with the top half of the dome removed. Of course it was far smaller; but it gave an impression of great size; and it could not have been less than two hundred feet from the edge, over which we saw the trees against the sky, to the tumbled dusty rocky floor where we stood.

‘I can only describe it as being like a great, burnt-out hell in the Inferno. Red dust lay everywhere, escape seemed impossible; and vast crags and galleries, with the mouths of passages showing high up, marked by iron bars and chains, jutted out here and there.

‘We amused ourselves here for some time, by climbing up the sides, calling to one another, for the whole place was full of echoes, rolling down stones from some of the upper ledges: but I nearly ended my days there.

‘I was standing on a path, about seventy feet up, leaning against the wall. It was a path along which feet must have gone a thousand times when the mine was in working order; and I was watching Murphy who was just emerging on to a platform opposite me, on the other side of the gulf.

‘I put my hand behind me to steady myself; and the next instant very nearly fell forward over the edge at the violent shock to my nerves given by a wood-pigeon who burst out of a hole, brushing my hand as he passed. I gripped on, however, and watched the bird soar out across space, and then up and out at the opening; and then I became aware that my knees were beginning to shake. So I stumbled along, and threw myself down on the little platform on to which the passage led.

‘I suppose I had been more startled than I knew; for I tripped as I went forward; and knocked my knee rather sharply on a stone. I felt for an instant quite sick with the pain on the top of jangling nerves; and lay there saying what I am afraid I ought not to have said.

‘Then Murphy came up when I called; and we made our way together through one of the sloping shafts; and came out on to the hillside among the trees.’

Mr Percival paused; his lips twitched a moment with amusement.

‘I am afraid I must recall my promise,’ he said. ‘I told you all this because I was anxious to give a reason for the feeling I had about the mine, and which I am bound to mention. I felt I never wanted to see the place again – yet in spite of what followed, I do not necessarily attribute my feelings to anything but the shock and the pain that I had had. You understand that?’

His bright eyes ran round our faces.

‘Yes, yes,’ said Monsignor sharply, ‘go on please, Mr Percival.’

‘Well then!’

The lawyer uncrossed his legs and replaced them the other way.

‘During lunch we told the landlady where we had been; and she begged us not to go there again. I told her that she might rest easy: my knee was beginning to swell. It was a wretched beginning to a walking tour.

‘It was not that, she said; but there had been a bad accident there. Four men had been killed there twenty years before by a fall of rock. That had been the last straw on the top of ill-success; and the mine had been abandoned.

‘We inquired as to the details; and it seemed that the accident had taken place in the central chamber locally called “The Cathedral”; and after a few more questions I understood.

‘“That was where you were, my friend,” I said to Murphy, “it was where you were when the bird flew out.”

‘He agreed with me; and presently when the woman was gone announced that he was going to the mine again to see the place. Well; I had no business to keep him dangling about. I couldn’t walk anywhere myself: so I advised him not to go on to that platform again; and presently he took a couple of candles from the sticks and went off. He promised to be back by four o’clock; and I settled down rather drearily to a pipe and some old magazines.

‘Naturally I fell sound asleep; it was a hot, drowsy afternoon and the magazines were dull. I awoke once or twice, and then slept again deeply.

‘I was awakened by the woman coming in to ask whether I would have tea; it was already five o’clock. I told her Yes. I was not in the least anxious about Murphy; he was a good climber, and therefore neither a coward nor a fool.

‘As tea came in I looked out of the window again, and saw him walking up to the path, covered with iron-dust, and a moment later I heard his step in the passage; and he came in.

‘Mrs What’s-her-name had gone out.

‘“Have you had a good time?” I asked.

‘He looked at me very oddly; and paused before he answered.

‘“Oh, yes,” he said; and put his cap and stick in a corner.

‘I knew Murphy.

‘“Well, why not?” I asked him, beginning to pour out tea.

‘He looked round at the door; then he sat down without noticing the cup I pushed across to him.

‘“My dear fellow,” he said. “I think I am going mad.”

‘Well; I forget what I said: but I understood that he was very much upset about something; and I suppose I said the proper kind of thing about his not being a qualified fool.

‘Then he told me his story.’

Mr Percival looked round at us again, still with that slight twitching of the lips that seemed to signify amusement.

‘Please remember—’ he began; and then broke off. ‘No – I won’t—

‘Well.

‘He had gone down the same shaft that we went down in the morning; and had spent a couple of hours exploring the passages. He had found an engine-room with tanks and rotten beams in it, and rusty chains. He had found some more lakes too, full of that extraordinary electric-blue water; he had disturbed a quantity of bats somewhere else. Then he had come out again into the central hall; and on looking at his watch had found it after four o’clock; so he thought he would climb up by the way we had come in the morning and go straight home.

‘It was as he climbed that his odd sensations began. As he went up, clinging with his hands, he became perfectly certain that he was being watched. He couldn’t turn round very well; but he looked up as he went to the opening overhead; but there was nothing there but the dead blue sky, and the trees very green against it, and the red rocks curving away on every side. It was extraordinarily quiet, he said, the pigeons had not come home from feeding, and he was out of hearing of the dripping water that I told you of.

‘Then he reached the platform and the opening of the path where I had had my fright in the morning; and turned round to look.

‘At first he saw nothing peculiar. The rocks up which he had come fell away at his feet down to the floor of the “Cathedral” and to the nettles with which he had stung his hands a minute or two before. He looked around at the galleries overhead and opposite; but there was nothing there.

‘Then he looked across at the platform where he had been in the morning and where the accident had taken place.

‘Let me tell you what this was like. It was about twenty yards in breadth, and ten deep; but lay irregular, and filled with tumbled rocks. It was a little below the level of his eyes, right across the gulf; and, in a straight line, would be about fifty or sixty yards away. It lay under the roof, rather retired, so that no light from the sky fell directly on to it; it would have been in complete twilight if it hadn’t been for a smaller shaft above it, which shot down a funnel of bluish light, exactly like a stage-effect. You see, Reverend Fathers, it was very theatrical altogether. That might account no doubt—’

Mr Percival broke off again, smiling.

‘I am always forgetting,’ he said. ‘Well, we must go back to Murphy. At first he saw nothing but the rocks, and the thick red dust, and the broken wall behind it. He was very honest, and told me that as he looked at it, he remembered distinctly what the landlady had told us at lunch. It was on that little stage that the tragedy had happened.

‘Then he became aware that something was moving among the rocks, and he became perfectly certain that people were looking at him; but it was too dusky to see very clearly at first. Whatever it was, was in the shadows at the back. He fixed his eyes on what was moving. Then this happened.’

The lawyer stopped again.

‘I will tell you the rest,’ he said, ‘in his own words, so far as I remember them.

‘“I was looking at this moving thing,” he said, “which seemed exactly of the red colour of the rocks, when it suddenly came out under the funnel of light; and I saw it was a man. He was in a rough suit, all iron-stained; with a rusty cap; and he had some kind of pick in his hand. He stopped first in the centre of the light, with his back turned to me, and stood there, looking. I cannot say that I was consciously frightened; I honestly do not know what I thought he was. I think that my whole mind was taken up in watching him.

‘“Then he turned round slowly, and I saw his face. Then I became aware that if he looked at me I should go into hysterics or something of the sort; and I crouched down as low as I could. But he didn’t look at me; he was attending to something else; and I could see his face quite clearly. He had a beard and moustache, rather ragged and rusty; he was rather pale, but not particularly: I judged him to be about thirty-five.” Of course,’ went on the lawyer, ‘Murphy didn’t tell it me quite as I am telling it to you. He stopped a good deal, he drank a sip of tea once or twice, and changed his feet about.

‘Well; he had seen this man’s face very clearly; and described it very clearly.

‘It was the expression that struck him most.

‘“It was rather an amused expression,” he said, “rather pathetic and rather tender; and he was looking interestedly about at everything – at the rocks above and beneath: he carried his pick easily in the crook of his arm. He looked exactly like a man whom I once saw visiting his home where he had lived as a child.” (Murphy was very particular about that, though I don’t believe he was right.) “He was smiling a little in his beard, and his eyes were half-shut. It was so pathetic that I nearly went into hysterics then and there,” said Murphy. “I wanted to stand up and explain that it was all right, but I knew he knew more than I did. I watched him, I should think for nearly five minutes, he went to and fro softly in the thick dust, looking here and there, sometimes in the shadow and sometimes out of it. I could not have moved for ten thousand pounds; and I could not take my eyes off him.

‘“Then just before the end, I did look away from him. I wanted to know if it was all real, and I looked at the rocks behind and the openings. Then I saw that there were other people there, at least there were things moving, of the colour of the rocks.

‘“I suppose I made some sound then; I was horribly frightened. At any rate, the man in the middle turned right round and faced me, and at that I sank down, with the sweat dripping from me, flat on my face, with my hands over my eyes.

‘“I thought of a hundred thousand things: of the inn, and you; and the walk we had had; and I prayed – well, I suppose I prayed. I wanted God to take me right out of this place. I wanted the rocks to open and let me through.”’

Mr Percival stopped. His voice shook with a tiny tremor. He cleared his throat.

‘Well, Reverend Fathers; Murphy got up at last, and looked about him; and of course, there was nothing there, but just the rocks and the dust, and the sky overhead. Then he came away home, the shortest way.’

It was a very abrupt ending; and a little sigh ran round the circle.

Monsignor struck a match noisily, and kindled his pipe again.

‘Thank you very much, sir,’ he said briskly.

Mr Percival cleared his throat again; but before he could speak Father Brent broke in.

‘Now that is just an instance of what I was saying, Monsignor, the night we began. May I ask if you really believe that those were the souls of the miners? Where’s the justice of it? What’s the point?’

Monsignor glanced at the lawyer.

‘Have you any theory, sir?’ he asked.

Mr Percival answered without lifting his eyes.

‘I think so,’ he said shortly, ‘but I don’t feel in the least dogmatic.’

Father Brent looked at him almost indignantly. ‘I should like to hear it,’ he said, ‘if you can square that—’

‘I do not square it,’ said the lawyer. ‘Personally I do not believe they were spirits at all.’

‘Oh?’

‘No. I do not; though I do not wish to be dogmatic. To my mind it seems far more likely that this is an instance of Mr Hudson’s theory – the American, you know. His idea is that all apparitions are no more than the result of violent emotions experienced during life. That about the pathetic expression is all nonsense, I believe.’

‘I don’t understand,’ said Father Brent.

‘Well; these men, killed by the fall of the roof, probably went through a violent emotion. This would be heightened in some degree by their loneliness and isolation from the world. This kind of emotion, Mr Hudson suggests, has a power of saturating material surroundings and under certain circumstances, would once more, like a phonograph, give off an image of the agent. In this instance, too, the absence of other human visitors would give this materialised emotion a chance, so to speak, of surviving; there would be very few cross-currents to confuse it. And finally, Murphy was alone; his receptive faculties would be stimulated by that fact, and all that he saw, in my belief, was the psychical wave left by these men in dying.’

‘Oh! did you tell him so?’

‘I did not. Murphy is a violent man.’

I looked up at Monsignor and saw him nodding emphatically to himself.

THE TRAVELLER (#ub7144a74-5945-5c9d-b42e-54d02844188e)

R.H. Benson

‘I am amazed, not that the Traveller returns from that Bourne, but that he returns so seldom.’

The Pilgrims’ Way

On one of these evenings as we sat together after dinner in front of the wide open fireplace in the central room of the house, we began to talk on that old subject – the relation of Science to Faith.

‘It is no wonder,’ said the priest, ‘if their conclusions appear to differ, to shallow minds who think that the last words are being said on both sides; because their standpoints are so different. The scientific view is that you are not justified in committing yourself one inch ahead of your intellectual evidence: the religious view is that in order to find out anything worth knowing your faith must always be a little in advance of your evidence; you must advance en échelon. There is the principle of our Lord’s promises. “Act as if it were true, and light will be given.” The scientist on the other hand says, “Do not presume to commit yourself until light is given.” The difference between the methods lies, of course, in the fact that Religion admits the heart and the whole man to the witness-box, while Science only admits the head – scarcely even the senses. Yet surely the evidence of experience is on the side of Religion. Every really great achievement is inspired by motives of the heart, and not of the head; by feeling and passion, not by a calculation of probabilities. And so are the mysteries of God unveiled by those who carry them first by assault; “The Kingdom of Heaven suffereth violence; and the violent take it by force.”

‘For example,’ he continued after a moment, ‘the scientific view of haunted houses is that there is no evidence for them beyond that which may be accounted for by telepathy, a kind of thought-reading. Yet if you can penetrate that veneer of scientific thought that is so common now, you find that by far the larger part of mankind still believes in them. Practically not one of us really accepts the scientific view as an adequate one.’

‘Have you ever had an experience of that kind yourself?’ I asked.

‘Well,’ said the priest, smiling, ‘you are sure you will not laugh at it? There is nothing commoner than to think such things a subject for humour; and that I cannot bear. Each such story is sacred to one person at the very least, and therefore should be to all reverent people.’

I assured him that I would not treat his story with disrespect.

‘Well,’ he answered, ‘I do not think you will, and I will tell you. It only happened a very few years ago. This was how it began:

‘A friend of mine was, and is still, in charge of a church in Kent, which I will not name; but it is within twenty miles of Canterbury. The district fell into Catholic hands a good many years ago. I received a telegram, in this house, a day or two before Christmas, from my friend, saying that he had been suddenly seized with a very bad attack of influenza, which was devastating Kent at that time; and asking me to come down, if possible at once, and take his place over Christmas. I had only lately given up active work, owing to growing infirmity, but it was impossible to resist this appeal; so Parker packed my things and we went together by the next train.

‘I found my friend really ill, and quite incapable of doing anything; so I assured him that I could manage perfectly, and that he need not be anxious.

‘On the next day, a Wednesday, and Christmas Eve, I went down to the little church to hear confessions. It was a beautiful old church, though tiny, and full of interesting things: the old altar had been set up again; there was a rood-loft with a staircase leading on to it; and an awmbry on the north of the sanctuary had been fitted up as a receptacle for the Most Holy Sacrament, instead of the old hanging pyx. One of the most interesting discoveries made in the church was that of the old confessional. In the lower half of the rood-screen, on the south side, a square hole had been found, filled up with an insertion of oak; but an antiquarian of the Alcuin Club, whom my friend had asked to examine the church, declared that this without doubt was the place where in pre-Reformation times confessions were heard. So it had been restored, and put to its ancient use; and now on this Christmas Eve I sat within the chancel in the dim fragrant light, while penitents came and knelt outside the screen on the single step, and made their confessions through the old opening.

‘I know this is a great platitude, but I never can look at a piece of old furniture without a curious thrill at a thing that has been so much saturated with human emotion; but, above all that I have ever seen, I think that this old confessional moved me. Through that little opening had come so many thousands of sins, great and little, weighted with sorrow; and back again, in Divine exchange for those burdens, had returned the balm of the Saviour’s blood. “Behold! a door opened in heaven,” through which that strange commerce of sin and grace may be carried on – grace pressed down and running over, given into the bosom in exchange for sin! O bonum commercium!’

The priest was silent for a moment, his eyes glowing. Then he went on.

‘Well, Christmas Day and the three following festivals passed away very happily. On the Sunday night after service, as I came out of the vestry, I saw a child waiting. She told me, when I asked her if she wanted me, that her father and others of her family wished to make their confessions on the following evening about six o’clock. They had had influenza in the house, and had not been able to come out before; but the father was going to work next day, as he was so much better, and would come, if it pleased me, and some of his children to make their confessions in the evening and their communions the following morning.

‘Monday dawned, and I offered the Holy Sacrifice as usual, and spent the morning chiefly with my friend, who was now able to sit up and talk a good deal, though he was not yet allowed to leave his bed.

‘In the afternoon I went for a walk.

‘All the morning there had rested a depression on my soul such as I have not often felt; it was of a peculiar quality. Every soul that tries, however poorly, to serve God, knows by experience those heavinesses by which our Lord tests and confirms His own: but it was not like that. An element of terror mingled with it, as of impending evil.

‘As I started for my walk along the high road this depression deepened. There seemed no physical reason for it that I could perceive. I was well myself, and the weather was fair; yet air and exercise did not affect it. I turned at last, about half-past three o’clock, at a milestone that marked sixteen miles to Canterbury.

‘I rested there for a moment, looking to the south-east, and saw that far on the horizon heavy clouds were gathering; and then I started homewards. As I went I heard a far-away boom, as of distant guns, and I thought at first that there was some sea-fort to the south where artillery practice was being held; but presently I noticed that it was too irregular and prolonged for the report of a gun; and then it was with a sense of relief that I came to the conclusion it was a far-away thunderstorm, for I felt that the state of the atmosphere might explain away this depression that so troubled me. The thunder seemed to come nearer, pealed more loudly three or four times and ceased.

‘But I felt no relief. When I reached home a little after four Parker brought me in some tea, and I fell asleep afterwards in a chair before the fire. I was wakened after a troubled and unhappy dream by Parker bringing in my coat and telling me it was time to keep my appointment at the church. I could not remember what my dream was, but it was sinister and suggestive of evil, and, with the shreds of it still clinging to me, I looked at Parker with something of fear as he stood silently by my chair holding the coat.

‘The church stood only a few steps away, for the garden and churchyard adjoined one another. As I went down carrying the lantern that Parker had lighted for me, I remember hearing far away to the south, beyond the village, the beat of a horse’s hoofs. The horse seemed to be in a gallop, but presently the noise died away behind a ridge.

‘When I entered the church I found that the sacristan had lighted a candle or two as I had asked him, and I could just make out the kneeling figures of three or four people in the north aisle.

‘When I was ready I took my seat in the chair beyond the screen, at the place I have described; and then, one by one, the labourer and his children came up and made their confessions. I remember feeling again, as on Christmas Eve, the strange charm of this old place of penitence, so redolent of God and man, each in his tenderest character of Saviour and penitent; with the red light burning like a luminous flower in the dark before me, to remind me how God was indeed tabernacling with men, and was their God.