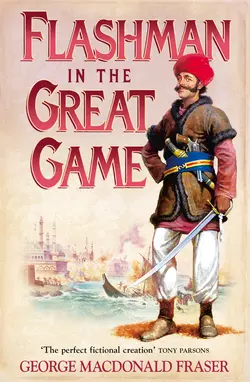

Flashman in the Great Game

George MacDonald Fraser

Coward, scoundrel, lover and cheat, but there is no better man to go into the jungle with. Join Flashman in his adventures as he survives fearful ordeals and outlandish perils across the four corners of the world.What caused the Indian Mutiny? The greased cartridge, religious fanaticism, political blundering, yes – but one hitherto unsuspected factor is now revealed to be the furtive figure who fled across India in 1857 with such frantic haste: Flashman.Plumbing new depths of anxious knavery in his role as secret agent extraordinaire, Flashman saw far more of the Great Mutiny than he wanted. How he survived Thugs and Tsarist agents, Eastern beauties and cabinet ministers and kept his skin intact is a mystery revealed here in this volume of The Flashman Papers.

Copyright (#ud4f79fc7-67ab-5766-9cc7-2dad5adb6134)

Harper

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by Barrie & Jenkins 1975

Copyright © George MacDonald Fraser 1975

How Did I Get the Idea of Flashman? © The Beneficiaries of the Literary Estate of George MacDonald Fraser 2015

Map © John Gilkes 2015

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

Cover illustration © Gino D’Achille

George MacDonald Fraser asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it, while at times based on historical events and figures, are the work of the author’s imagination.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007217199

Ebook Edition © 2015 ISBN: 9780007449514

Version: 2015-07-14

The following piece was found in the author’s study in 2013 by the Estate of George MacDonald Fraser.

How Did I Get the Idea of Flashman? (#ud4f79fc7-67ab-5766-9cc7-2dad5adb6134)

‘How did you get the idea of Flashman?’ and ‘When are we going to get his U.S. Civil War memoirs?’ are questions which I have ducked more often than I can count. To the second, my invariable response is ‘Oh, one of these days’. Followed, when the inquirer is an impatient American, by the gentle reminder that to an old British soldier like Flashman the unpleasantness between the States is not quite the most important event of the nineteenth century, but rather a sideshow compared to the Mutiny or Crimea. Before they can get indignant I add hastily that his Civil War itinerary is already mapped out; this is the only way of preventing them from telling me what it ought to be.

To the question, how did I get the idea, I simply reply that I don’t know. Who ever knows? Anthony Hope conceived The Prisoner of Zenda on a walk from Westminster to the Temple, but I doubt if he could have said, after the calendar month it took him to write the book, what triggered the idea. In my case, Flashman came thundering out of the mists of forty years living and dreaming, and while I can list the ingredients that went to his making, heaven only knows how and when they combined.

One thing is sure: the Flashman Papers would never have been written if my fellow clansman Hugh Fraser, Lord Allander, had confirmed me as editor of the Glasgow Herald in 1966. But he didn’t, the canny little bandit, and I won’t say he was wrong. I wouldn’t have lasted in the job, for I’d been trained in a journalistic school where editors were gods, and in three months as acting chief my attitude to management, front office, and directors had been that of a seigneur to his serfs – I had even put Fraser’s entry to the House of Lords on an inside page, assuring him that it was not for the Herald, his own paper, to flaunt his elevation, and that a two-column picture of him was quite big enough. How cavalier can you get?

And doubtless I had other editorial shortcomings. In any event, faced with twenty years as deputy editor (which means doing all the work without getting to the big dinners), I promised my wife I would ‘write us out of it’. In a few weeks of thrashing the typewriter at the kitchen table in the small hours, Flashman was half-finished, and likely to stay that way, for I fell down a waterfall, broke my arm, and lost interest – until my wife asked to read what I had written. Her reaction galvanised me into finishing it, one draft, no revisions, and for the next two years it rebounded from publisher after publisher, British and American.

I can’t blame them: the purported memoir of an unregenerate blackguard, bully, and coward resurrected from a Victorian school story is a pretty eccentric subject. By 1968 I was ready to call it a day, but thanks to my wife’s insistence and George Greenfield’s matchless knowledge of the publishing scene, it found a home at last with Herbert Jenkins, the manuscript looking, to quote Christopher MacLehose, as though it had been round the world twice. It dam’ nearly had.

They published it as it stood, with (to me) bewildering results. It wasn’t a bestseller in the blockbuster sense, but the reviewers were enthusiastic, foreign rights (starting with Finland) were sold, and when it appeared in the U.S.A. one-third of forty-odd critics accepted it as a genuine historical memoir, to the undisguised glee of the New York Times, which wickedly assembled their reviews. ‘The most important discovery since the Boswell Papers’ is the one that haunts me still, for if I was human enough to feel my lower ribs parting under the strain, I was appalled, sort of.

You see, while I had written a straightforward introduction describing the ‘discovery’ of the ‘Papers’ in a saleroom in Ashby-de-la-Zouche (that ought to have warned them), and larded it with editorial ‘foot-notes’, there had been no intent to deceive; for one thing, while I’d done my best to write, first-person, in Victorian style, I’d never imagined that it would fool anybody. Nor did Herbert Jenkins. And fifty British critics had recognised it as a conceit. (The only one who was half-doubtful was my old chief sub on the Herald; called on to review it for another paper, he demanded of the Herald’s literary editor: ‘This book o’ Geordie’s isnae true, is it?’ and on being assured that it wasn’t, exclaimed: ‘The conniving bastard!’, which I still regard as a high compliment.)

With the exception of one left-wing journal which hailed it as a scathing attack on British imperialism, the press and public took Flashman, quite rightly, at face value, as an adventure story dressed up as the memoirs of an unrepentant old cad who, despite his cowardice, depravity and deceit, had managed to emerge from fearful ordeals and perils an acclaimed hero, his only redeeming qualities being his humour and shameless honesty as a memorialist. I was gratified, if slightly puzzled to learn that the great American publisher, Alfred Knopf, had said of the book: ‘I haven’t heard this voice in fifty years’, and that the Commissioner of Metropolitan Police was recommending it to his subordinates. My interest increased as I wrote more Flashman books, and noted the reactions.

I was, several critics agreed, a satirist. Taking revenge on the nineteenth century on behalf of the twentieth, said one. Waging war on Victorian hypocrisy, said another. Plainly under the influence of Conrad, said yet another. A full-page review in a German paper took me flat aback when my eye fell on the word ‘Proust’ in the middle of it. I don’t read German, so for all I know the review may have been maintaining that Proust was a better stand-off half than I was, or used more semi-colons. But there it was, and it makes you think. And a few years ago a highly respected religious journal said that the Flashman Papers deserved recognition as the work of a sensitive moralist, and spoke of service not only to literature and history, but to the study of ethics.

My instant reaction to this was to paraphrase Poins: ‘God send me no worse fortune, but I never said so!’ while feeling delighted that someone else had said it, and then reflecting solemnly that this was a far cry from long nights with cold tea and cigarettes, scheming to get Flashman into the passionate embrace of the Empress of China, or out of the toils of a demented dwarf on the edge of a snake-pit. But now, beyond remarking that the anti-imperial left-winger was sadly off the mark, that the Victorians were mere amateurs in hypocrisy compared to our own brainwashed, sanctimonious, self-censoring and terrified generation, and that I hadn’t read a word of Conrad by 1966 (and my interest in him since has been confined to Under WesternEyes, in the hope that I might persuade Dick Lester to film it as only he could), I have no comments to offer on opinions of my work. I know what I’m doing – at least, I think I do – and the aim is to entertain (myself, for a start) while being true to history, to let Flashman comment on human and inhuman nature, and devil take the romantics and the politically correct revisionists both. But my job is writing, not explaining what I’ve written, and I’m well content and grateful to have others find in Flashy whatever they will (I’ve even had letters psychoanalysing the brute), and return to the question with which I began this article.

A life-long love affair with British imperial adventure, fed on tupenny bloods, the Wolf of Kabul and Lionheart Logan (where are they now?), the Barrack-Room Ballads, films like Lives of aBengal Lancer and The Four Feathers, and the stout-hearted stories for boys which my father won as school prizes in the 1890s; the discovery, through Scott and Sabatini and Macaulay, that history is one tremendous adventure story; soldiering in Burma, and seeing the twilight of the Raj in all its splendour; a newspaper-trained lust for finding the truth behind the received opinion; being a Highlander from a family that would rather spin yarns than eat … I suppose Flashman was born out of all these things, and from reading Tom Brown’s Schooldays as a child – and having a wayward cast of mind.

Thanks to that contrary streak (I always half-hoped that Rathbone would kill Flynn, confounding convention and turning the story upside down – Basil gets Olivia, Claude Rains triumphs, wow!), I recognised Flashman on sight as the star of Hughes’ book. Fag-roasting rotter and poltroon he might be, he was nevertheless plainly box-office, for he had the looks, swagger and style (‘big and strong’, ‘a bluff, offhand manner’, and ‘considerable powers of being pleasant’, according to this creator) which never fail to cast a glamour on villainy. I suspect Hughes knew it, too, and got rid of him before he could take over the book – which loses all its spirit and zest once Flashy has made his disgraced and drunken exit.

[He was, by the way, a real person; this I learned only recently. A letter exists from one of Hughes’ Rugby contemporaries which is definite on the point, but tactfully does not identify him. I have sometimes speculated about one boy who was at Rugby in Hughes’ day, and who later became a distinguished soldier and something of a ruffian, but since I haven’t a shred of evidence to back up the speculation, I keep it to myself.]

What became of him after Rugby seemed to me an obvious question, which probably first occurred to me when I was about nine, and then waited thirty years for an answer. The Army, inevitably, and since Hughes had given me a starting-point by expelling him in the late 1830s, when Lord Cardigan was in full haw-haw, and the Afghan War was impending… just so. I began with no idea of where the story might take me, but with Victorian history to point the way, and that has been my method ever since: choose an incident or campaign, dig into every contemporary source available, letters, diaries, histories, reports, eye-witness, trivia (and fictions, which like the early Punch are mines of detail), find the milestones for Flashy to follow, more or less, get impatient to be writing, and turn him loose with the research incomplete, digging for it as I go and changing course as history dictates or fancy suggests.

In short, letting history do the work, with an eye open for the unexpected nuggets and coincidences that emerge in the mining process – for example, that the Cabinet were plastered when they took their final resolve on the Crimea, that Pinkerton the detective had been a trade union agitator in the very place where Flashman was stationed in the first book, that Kipling’s The Man Who Would Be King had a factual basis, or that Bismarck and Lola Montez were in London in the same week (of 1842, if memory serves, which it often doesn’t: whenever Flashman has been a subject on Mastermind I have invariably scored less than the contestants).

Visiting the scenes helps; I’d not have missed Little Big Horn, the Borneo jungle rivers, Bent’s Fort, or the scruffy, wonderful Gold Road to Samarkand, for anything. Seeking out is half the fun, which is one reason why I decline all offers of help with research (from America, mostly). But the main reason is that I’m a soloist, giving no hints beforehand, even to publishers, and permitting no editorial interference afterwards. It may be tripe, but it’s my tripe – and I do strongly urge authors to resist encroachments on their brain-children, and trust their own judgment rather than that of some zealous meddler with a diploma in creative punctuation who is just dying to get into the act.

One of the great rewards of writing about my old ruffian has been getting and answering letters, and marvelling at the kindness of readers who take the trouble to let me know they have enjoyed his adventures, or that he has cheered them up, or turned them to history. Sitting on the stairs at 4 a.m. talking to a group of students who have phoned from the American Midwest is as gratifying as learning from a university lecturer that he is using Flashman as a teaching aid. Even those who want to write the books for you, or complain that he’s a racist (of course he is; why should he be different from the rest of humanity?), or insist that he isn’t a coward at all, but just modest, and they’re in love with him, are compensated for by the stalwarts who’ve named pubs after him (in Monte Carlo, and somewhere in South Africa, I’m told), or have formed societies in his honour. They’re out there, believe me, the Gandamack Delopers of Oklahoma, and Rowbotham’s Mosstroopers, and the Royal Society of Upper Canada, with appropriate T-shirts.

I have discovered that when you create – or in my case, adopt and develop – a fictional character, and take him through a series of books, an odd thing happens. He assumes, in a strange way, a life of his own. I don’t mean that he takes you over; far from it, he tends to hive off on his own. At any rate, you find that you’re not just writing about him: you are becoming responsible for him. You’re not just his chronicler: you are also his manager, trainer, and public relations man. It’s your own fault – my own fault – for pretending that he’s real, for presenting his adventures as though they were his memoirs, putting him in historical situations, giving him foot-notes and appendices, and inviting the reader to accept him as a historical character. The result is that about half the letters I get treat him as though he were a person in his own right – of course, people who write to me know that he’s nothing of the sort – well, most of them realise it: I occasionally get indignant letters from people complaining that they can’t find him in the Army List or the D.N.B., but nearly all of them know he’s fiction, and when they pretend that he isn’t, they’re just playing the game. I started it, so I can’t complain.

When Hughes axed Flashman from Tom Brown’s Schooldays, brutally and suddenly (on page 170, if I remember rightly), it seemed a pretty callous act to abandon him with all his sins upon him, just at the stage of adolescence when a young fellow needs all the help and understanding he can get. So I adopted him, not from any charitable motives, but because I realised that there was good stuff in the lad, and that with proper care and guidance something could be made out of him.

And I have to say that with all his faults (what am I saying, because of his faults) young Flashy has justified the faith I showed in him. Over the years he and I have gone through several campaigns and assorted adventures, and I can say unhesitatingly that coward, scoundrel, toady, lecher and dissembler though he may be, he is a good man to go into the jungle with.

George MacDonald Fraser

Dedication (#ud4f79fc7-67ab-5766-9cc7-2dad5adb6134)

For the Mad White Woman of Papar River

Contents

Cover (#ubebd8a63-e19c-5ddc-90a1-d41b68c7bbc4)

Title Page (#u761cd722-dfc4-5bd1-b364-94dc5c304246)

Copyright

How Did I Get the Idea of Flashman?

Dedication

Explanatory Note

Map (#u26732358-9e17-50ab-b0f3-b44901b65ed2)

Chapter 1 (#u03d0c984-5268-5cec-9cbf-5491b8f2fc3f)

Chapter 2 (#ube983702-2a61-514c-9b46-4ef3fa715be0)

Chapter 3 (#u7977cd8e-94b4-58b2-9238-cf67cd775cf2)

Chapter 4 (#u0eed7f75-1207-5597-80e7-ff9f7dd9ab5f)

Chapter 5 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 6 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Appendix I

Appendix II

Footnotes

Notes

About the Author

The FLASHMAN Papers: In chronological order

The FLASHMAN Papers: In order of publication

Also by George MacDonald Fraser

About the Publisher

EXPLANATORY NOTE (#ud4f79fc7-67ab-5766-9cc7-2dad5adb6134)

One of the most encouraging things about editing the first four volumes of the Flashman Papers has been the generous response from readers and students of history in many parts of the world. Since the discovery of Flashman’s remarkable manuscript in a Leicestershire saleroom in 1965, when it was realised that it was the hitherto-unsuspected autobiographical memoir of the notorious bully of Tom Brown’s Schooldays, letters have reached the editor from such diverse places as Ascension Island, a G.I. rest camp in Vietnam, university faculties and campuses in Britain and America, a modern caravanserai on the Khyber Pass road, a police-station cell in southern Australia, and many others.

What has been especially gratifying has been not only the interest in Flashman himself, but the close historical knowledge which correspondents have shown of the periods and incidents with which his memoirs have dealt so far – the first Afghan War, the solution of the Schleswig-Holstein Question (involving as it did Count Bismarck and Lola Montez), the Afro-American slave trade, and the Crimean War. Many have contributed interesting observations, and one or two have detected curious discrepancies in Flashman’s recollections which, regrettably, escaped his editor. A lady in Athens and a gentleman in Flint, Michigan, have pointed out that Flashman apparently saw the Duchess of Wellington at a London theatre some years after her death, and a letter on Foreign Office notepaper has remarked on his careless reference to a ‘British Ambassador’ in Washington in 1848, when in fact Her Majesty’s representative in the American capital held a less exalted diplomatic title. Such lapses are understandable, if not excusable, in a hard-living octogenarian.

Equally interesting have been such communications as those from a gentleman in New Orleans who claims to be Flashman’s illegitimate great-grandson (as the result of a liaison in a military hospital at Richmond, Va., during the U.S. Civil War), and from a British serving officer who asserts that his grandfather lent fifty dollars and a horse to Flashman during the same campaign; neither, apparently, was returned.

It is possible that these and other matters of interest will be resolved when the later papers are edited. The present volume deals with Flashman’s adventures in the Indian Mutiny, where he witnessed many of the dramatic moments of that terrible struggle, and encountered numerous Victorian celebrities – monarchs, statesmen, and generals among them. As in previous volumes, his narrative tallies closely with accepted historical fact, as well as furnishing much new information, and there has been little for his editor to do except correct his spelling, deplore his conduct, and provide the usual notes and appendices.

G.M.F.

They don’t often invite me to Balmoral nowadays, which is a blessing; those damned tartan carpets always put me off my food, to say nothing of the endless pictures of German royalty and that unspeakable statue of the Prince Consort standing knock-kneed in a kilt. King Teddy’s company is something I’d sooner avoid than not, anyway, for he’s no better than an upper-class hooligan. Of course, he’s been pretty leery of me for forty-odd years (ever since I misguided his youthful footsteps into an actress’s bed, in fact, and brought Papa Albert’s divine wrath down on his fat head) and when he finally wheezed his way on to the throne I gather he thought of dropping me altogether – said something about my being Falstaff to his Prince Hal. Falstaff, mark you – from a man with piggy eyes and a belly like a Conestoga wagon cover. Vile taste in cigars he has, too.

In the old Queen’s time, of course, I was at Balmoral a great deal. She always fancied me, from when she was a chit of a girl and pinned the Afghan medal on my manly breast, and after I had ridden herd on that same precious Teddy through the Tranby Croft affair and saved him from the worst consequences of his own folly, she couldn’t do enough for me. Each September after that, regular as clockwork, there would come a command for ‘dear General Flashman’ to take the train north to Kailyard Castle, and there would be my own room, with a bowl of late roses on the window-sill, and a bottle of brandy on the side-table with a discreet napkin over it – they knew my style. So I put up with it; she was all right, little Vicky, as long as you gave her your arm to lean on, and let her prattle on endlessly, and the rations were adequate. But even then, I never cottoned to the place. Not only, as I’ve said, was it furnished in a taste that would have offended the sensibilities of a nigger costermonger, it had the most awful Highland gloom about it – all drizzle and mist and draughts under the door and holy melancholy: even the billiard-room had a print on the wall of a dreadful ancient Scotch couple glowering devoutly. Praying, I don’t doubt, for me to be snookered.

But I think what really turns me against Balmoral in my old age is its memories. It was there that the Great Mutiny began for me, and on my rare excursions north nowadays there’s a point on the line where the rhythm of the wheels changes, and in my imagination they begin to sing: ‘Mera-Jhansi-denge-nay, mera-Jhansi-denge-nay’, over and over, and in a moment the years have dropped away, and I’m remembering how I first came to Balmoral half a century ago; aye, and what it led to – the stifling heat of the parade ground at Meerut with the fettering-hammers clanging; the bite of the muzzle of the nine-pounder jammed into my body and my own blood steaming on the sun-scorched iron; old Wheeler bawling hoarsely as the black cavalry sabres come thundering across the maidan towards our flimsy rampart (‘No surrender! One last volley, damn ’em, and aim at the horses!’); the burning bungalows, a skeleton hand in the dust, Colin Campbell scratching his grizzled head, the crimson stain spreading in the filthy water below Suttee Ghat, a huge glittering pile of silver and gold and jewels and ivory bigger than anything you’ve ever seen – and two great brown liquid eyes shadowed with kohl, a single pearl resting on the satin skin above them, open red lips trembling … and, blast him, here’s the station-master, beaming and knuckling his hat and starting me out of the only delightful part of that waking nightmare, with his cry of ‘Welcome back tae Deeside, Sir Harry! Here we are again, then!’

And as he hands me down to the platform, you may be sure the local folk are all on hand, bringing their brats to stare and giggle at the big old buffer in his tweed cape and monstrous white whiskers (‘There he is! The V.C. man, Sir Harry Flashman – aye, auld Flashy, him that charged wi’ the Light Brigade and killed a’ the niggers at Kau-bool – Goad, but isnae he the auld yin? – hip, hooray!’). So I acknowledge the cheers with a wave, bluff and hearty, as I step into the dog-cart, stepping briskly to escape the inevitable bemedalled veteran who comes shuffling after me, hoping I’ll slip him sixpence for a dram when he assures me that we once stood together in the Highlanders’ line at Balaclava. Lying old bastard, he was probably skulking in bed.

Not that I’d blame him if he was, mark you; given the chance I’d have skulked in mine – and not just at Balaclava, neither, but at every battle and skirmish I’ve sweated and scampered through during fifty inglorious years of unwilling soldiering. (Leastways, I know they were inglorious, but the country don’t, thank heaven, which is why they’ve rewarded me with general rank and the knighthood and a double row of medals on my left tit. Which shows you what cowardice and roguery can do, given a stalwart appearance, long legs, and a thumping slice of luck. Aye, well whip up, driver, we mustn’t keep royalty waiting.)

But to return to the point, which is the Mutiny, and that terrible, incredible journey that began at Balmoral – well, it was as ghastly a road as any living man travelled in my time. I’ve seen a deal of war, and agree with Sherman that it’s hell, but the Mutiny was the Seventh Circle under the Pit. Of course, it had its compensations: for one, I came through it, pretty whole, which is more than Havelock and Harry East and Johnny Nicholson did, enterprising lads that they were. (What’s the use of a campaign if you don’t survive it?) I did, and it brought me my greatest honour (totally undeserved, I needn’t tell you), and a tidy enough slab of loot which bought and maintains my present place in Leicestershire – I reckon the plunder’s better employed keeping me and my tenants in drink, than it was decorating a nigger temple for the edification of a gang of blood-sucking priests. And along the Mutiny road I met and loved that gorgeous, wicked witch Lakshmibai – there were others, too, naturally, but she was the prime piece.

One other thing about the Mutiny, before I get down to cases – I reckon it must be about the only one of my campaigns that I was pitched into through no fault of mine. On other occasions, I’ll own, I’ve been to blame; for a man with a white liver a yard wide I’ve had a most unhappy knack of landing myself neck-deep in the slaughter through my various follies – to wit, talking too much (that got me into the Afghan débâcle of ’41); playing the fool in pool-rooms (the Crimea); believing everything Abraham Lincoln told me (American Civil War); inviting a half-breed Hunkpapa whore to a regimental ball (the Sioux Rising of ’76), and so on; the list’s as long as my arm. But my involvement in the Mutiny was all Palmerston’s doing (what disaster of the ’fifties wasn’t?).

It came out of as clear and untroubled a sky as you could wish, a few months after my return from the Crimea, where, as you may know, I’d won fresh laurels through my terrified inability to avoid the most gruelling actions. I had stood petrified in the Thin Red Streak, charged with the Heavies and Lights, been taken prisoner by the Russians, and after a most deplorable series of adventures (in which I was employed as chief stud to a nobleman’s daughter, was pursued by hordes of wolves and Cossacks, and finally was caught up in a private war between Asian bandits and a Ruski army bound for India – it’s all in my memoirs somewhere) had emerged breathless and lousy at Peshawar.

There, as if I hadn’t had trouble enough, I was restoring my powers by squandering them on one of those stately, hungry Afghan Amazons, and she must have been a long sight better at coupling than cooking, for something on her menu gave me the cholera. I was on the broad of my back for months, and it took a slow, restful voyage home before I was my own man again, in prime fettle for the reunion with my loving Elspeth and to enjoy the role of a returned hero about town. And, I may add, a retired hero; oxen and wainropes weren’t going to drag Flashy back to the Front again. (I’ve made the same resolve a score of times, and by God I’ve meant it, but you can’t fight fate, especially when he’s called Palmerston.)

However, there I was in the summer of ’56, safely content on half pay as a staff colonel, with not so much as a sniff of war in sight, except the Persian farce, and that didn’t matter. I was comfortably settled with Elspeth and little Havvy (the first fruit of our union, a guzzling lout of seven) in a fine house off Berkeley Square which Elspeth’s inheritance maintained in lavish style, dropping by occasionally at Horse Guards, leading the social life, clubbing and turfing, whoring here and there as an occasional change from my lawful brainless beauty, and being lionised by all London – well, I’d stood at Armageddon and battled for the Lord (ostensibly) hadn’t I, and enough had leaked out about my subsequent secret exploits in Central Asia (though government was damned cagey about them, on account of our delicate peace negotiations with Russia) to suggest that Flashy had surpassed all his former heroics. So with the country in a patriotic fever about its returning braves, I was ace-high in popular esteem – there was even talk that I’d get one of the new Victoria Crosses (for what that was worth) but it’s my belief that Airey and Cardigan scotched it between them. Jealous bastards.

I suspect that Airey, who’d been chief of staff to Raglan in Crimea, hadn’t forgotten my minor dereliction of duty at the Alma, when the Queen’s randy little cousin Willy got his fool head blown off while under my care. And Cardigan loathed me, not least because I’d once emerged drunk, in the nick of time, from a wardrobe to prevent him cocking his lustful leg over my loving Elspeth. (She was no better than I was, you know.) And since coming home, I hadn’t given him cause to love me any better.

You see, there was a deal of fine malicious tittle-tattle going about that summer, over Cardigan’s part in the Light Brigade fiasco – not so much about his responsibility for the disaster, which was debatable, if you ask me, but for his personal behaviour at the guns. He’d been at the head of the charge, right enough, with me alongside on a bolting horse, farting my fearful soul out, but after we’d reached the battery he’d barely paused to exchange a cut or two with the Ruski gunners before heading for home and safety again. Shocking bad form in a commander, says I, who was trying to hide under a gun limber at the time – not that I think for a moment that he was funking it; he hadn’t the brains to be frightened, our Lord Haw-Haw. But he had retreated without undue delay, and since he was never short of enemies eager to believe the worst, the gossips were having a field day now. There were angry letters in the press, and even a law-suit,

and since I’d been in the thick of the action, it was natural that I should be asked about it.

In fact, it was George Paget, who’d commanded the 4th Lights in the charge, who put the thing to me point-blank in the card-room at White’s (can’t imagine what I was doing there; must have been somebody’s guest) in front of a number of people, civilians mostly, but I know Spottswood was there, and old Scarlett of the Heavies, I think.

‘You were neck and neck with Cardigan,’ says Paget, ‘and in the battery before anyone else. Now, God knows he’s not my soul-mate, but all this talk’s getting a shade raw. Did you see him in the battery or not?’

Well, I had, but I wasn’t saying so – far be it from me to clear his lordship’s reputation when there was a chance of damaging it. So I said offhand:

‘Don’t ask me, George; I was too busy hunting for your cigars,’ which caused a guffaw.

‘No gammon, Flash,’ says he, looking grim, and asked again, in his tactful way: ‘Did Cardigan cut out, or not?’

There were one or two shocked murmurs, and I shuffled a pack, frowning, before I answered. There are more ways than one of damning a man’s credit, and I wanted to give Cardigan of my best. So I looked uncomfortable, and then growled, slapped the pack down as I rose, looked Paget in the eye, and said:

‘It’s all by and done with now, ain’t it? Let’s drop it, George, shall we?’ And I went out then and there, leaving behind the impression that bluff, gallant Flashy didn’t want to talk about it – which convinced them all that Cardigan had shirked, better than if I’d said so straight out, or called him a coward to his face. I had a chance to do that, too, a bare two hours later, when the man himself came raging up to me with a couple of his toadies in tow, just as Spottswood and I were coming out of the Guards Club. The hall was full of fellows, goggling at the sensation.

‘Fwashman! You there, sir!’ he croaked – they were absolutely the first words between us since the Charge, nearly two years before. He was breathing frantically, like a man who has been running, his beaky face all mottled and his grey whiskers quaking with fury. ‘Fwashman – this is intolewable! My honour is impugned – scandalous lies, sir! And they tell me that you don’t deny them! Well, sir? Well? Haw-haw?’

I tilted back my tile with a forefinger and looked him up and down, from his bald head and pop eyes to his stamping foot. He looked on the edge of apoplexy; a delightful sight.

‘What lies are these, my lord?’ says I, very steady.

‘You know vewy well!’ he cried. ‘Bawacwava, sir – the storming of the battewy! Word George Paget has asked you, in pubwic, whether you saw me at the guns – and you have the effwontewy to tell him you don’t know! Damnation, sir! And one of my own officers, too—’

‘A former member of your regiment, my lord – I admit the fact.’

‘Blast your impudence!’ he roared, frothing at me. ‘Will you give me the lie? Will you say I was not at the guns?’

I settled my hat and pulled on my gloves while he mouthed.

‘My lord,’ says I, speaking deliberately clear, ‘I saw you in the advance. In the battery itself – I was otherwise engaged, and had no leisure nor inclination to look about me to see who was where. For that matter, I did not see Lord George himself until he pulled me to my feet. I assumed –’ and I bore on the word ever so slightly ‘– that you were on hand, at the head of your command. But I do not know, and frankly I do not care. Good day to you, my lord.’ And with a little nod I turned to the door.

His voice pursued me, cracking with rage.

‘Colonel Fwashman!’ he cried. ‘You are a viper!’

I turned at that, making myself go red in the face in righteous wrath, but I knew what I was about; he was getting no blow or challenge from me – he shot too damned straight for that.

‘Indeed, my lord,’ says I. ‘Yet I don’t wriggle and turn.’ And I left him gargling, well pleased with myself. But, as I say, it probably cost me the V.C. at the time; for all the rumours, he was still a power at Horse Guards, and well insinuated at Court, too.

However, our little exchange did nothing to diminish my popularity at large; a few nights later I got a tremendous cheer at the Guards Dinner at Surrey Gardens, with chaps standing on the table shouting ‘Huzza for Flash Harry!’ and singing ‘Garryowen’ and tumbling down drunk – how they did it on a third of a bottle of bubbly beat me.

Cardigan wasn’t there, sensible fellow; they’d have hooted him out of the kingdom. As it was, Punch carried a nasty little dig about his absence, and wondered that he hadn’t sent along his spurs, since he’d made such good use of them in retiring from the battery.

Of course, Lord Haw-Haw wasn’t the only general to come under the public lash that summer; the rest of ’em, like Lucan and Airey, got it too for the way they’d botched the campaign. So while we gallant underlings enjoyed roses and laurels all the way, our idiot commanders were gainfully employed exchanging recriminations, writing furious letters to the papers saying ’twasn’t their fault, but some other fellow’s, and there had even been a commission set up to investigate their misconduct of the war.

Unfortunately, government picked the wrong men to do the investigating – MacNeill and Tulloch – for they turned out to be honest, and reported that indeed our high command hadn’t been fit to dig latrines, or words to that effect. Well, that plainly wouldn’t do, so another commission had to be hurriedly formed to investigate afresh, and this time get the right answer, and no nonsense about it. Well, they did, and exonerated everybody, hip-hip-hurrah and Rule, Britannia. Which was what you’d have expected any half-competent government to stage-manage in the first place, but Palmerston was in the saddle by then, and he wasn’t really good at politics, you know.

To crown it all, in the middle of the scandal the Queen herself had words about it with Hardinge, the Commander-in-Chief, at the Aldershot Review, and poor old Hardinge fell down paralysed and never smiled again. It’s true; I was there myself, getting soaked through, and Hardinge went down like a shanghaied sailor, with all his faculties gone, not that he had many to start with. Some said it was a judgement on the Army and government corruption, so there.

All of which mattered rather less to me than the width of Elspeth’s crinolines, but if I’ve digressed it is merely to show you how things were in England then, and also because I can never resist the temptation to blackguard Cardigan as he deserves. Meanwhile, I was going happily about my business, helping my dear wife spend her cash – which she did like a clipper-hand in port, I’m bound to say – and you would have said we were a blissful young couple, turning a blind eye to each other’s infidelities and galloping in harness when we felt like it, which was frequent, for if anything she got more beddable with the passing years.

And then came the invitation to Balmoral, which reduced Elspeth to a state of nervous exultation close to hysterics, and took me clean aback. I’d have imagined that if the Royal family ever thought of me at all, it was as the chap who’d been remiss enough to lose one of the Queen’s cousins – but mind you, she had so many of ’em she probably didn’t notice, or if she did, hadn’t heard that I was to blame for it. No, I’ve puzzled over it sometimes, and can only conclude that the reason we were bidden to Balmoral that September was that Russia was still very much the topic of the day, what with the new Tsar’s coronation and the recent peace, and I was one of the most senior men to have been a prisoner in Russia’s hands.

I didn’t have leisure to speculate at the time, though, for Elspeth’s frenzy at the thought of being ‘in attendance’, as she chose to call it, claimed everyone’s attention within a mile of Berkeley Square. Being a Scotch tradesman’s daughter, my darling was one degree more snobbish than a penniless Spanish duke, and in the days before we went north her condescension to her middle-class friends would have turned your stomach. Between gloating, and babbling about how she and the Queen would discuss dressmaking while Albert and I boozed in the gunroom (she had a marvellous notion of court life, you see), she went into declines at the thought that she would come out in spots, or have her drawers fall down when being presented. You must have endured the sort of thing yourself.

‘Oh, Harry, Jane Speedicut will be green! You and I – guests of Her Majesty! It will be the finest thing – and I have my new French dresses – the ivory, the beige silk, the lilac satin, and the lovely, lovely green which old Admiral Lawson so admired – if you think it is not a leetle low for the Queen? And my barrege for Sunday – will there be members of the nobility staying also? – will there be ladies whose husbands are of lower rank than you? Ellen Parkin – Lady Parkin, indeed! – was consumed with spite when I told her – oh, and I must have another maid who can manage my hair, for Sarah is too maladroit for words, although she is very passable with dresses – what shall I wear to picnics? – for we shall be bound to walk in the lovely Highland countryside – oh, Harry, what do you suppose the Queen reads? – and shall I call the Prince “highness” or “sir”?’

I was glad, I can tell you, when we finally reached Abergeldie, where we had rooms in the castle where guests were put up – for Balmoral was very new then, and Albert was still busy having the finishing touches put to it. Elspeth by this time was too nervous even to talk, but her first glimpse of our royal hosts reduced her awe a trifle, I think. We took a stroll the first afternoon, in the direction of Balmoral, and on the road encountered what seemed to be a family of tinkers led by a small washerwoman and an usher who had evidently pinched his headmaster’s clothes. Fortunately, I recognised them as Victoria and Albert out with their brood, and knew enough simply to raise my hat as we passed, for they loathed to be treated as royalty when they were playing at being commoners. Elspeth didn’t even suspect who it was until we were past, and when I told her she swooned by the roadside. I revived her by threatening to carry her into the bushes and molest her, and on the way back she observed that really Her Majesty had looked quite royal, but in a common sort of way.

By the time we were presented at Balmoral, though, the next day, she was high up the scale again, and the fact that we shared the waiting-room beforehand with some lord or other and his beak-nosed lady, who looked at us as though we were riff-raff, reduced my poor little scatterbrain to quaking terror. I’d met the royals before, of course, and tried to reassure her, whispering that she looked a stunner (which was true) and not to be put out by Lord and Lady Puffbuttock, who were now ignoring us with that icy incivility which is the stamp of our lower-class aristocracy. (I know; I’m one myself nowadays.)

It was quite handy that our companions kept their noses in the air, though, for it gave me the chance to loop a ribbon from the lady’s enormous crinoline on to an occasional table without her knowing, and when the doors to the royal drawing-room were opened she set off and brought the whole thing crashing down, crockery and all, in full view of the little court circle. I kept Elspeth in an iron grip, and steered her round the wreckage, and so Colonel and Mrs Flashman made their bows while the doors were hurriedly closed behind us, and the muffled sounds of the Puffbuttocks being extricated by flunkeys was music to my ears, even if it did make the Queen look more pop-eyed than usual. The moral is: don’t put on airs with Flashy, and if you do, keep your crinolines out of harm’s way.

And, as it turned out, to Elspeth’s lifelong delight and my immense satisfaction, she and the Queen got on like port and nuts from the first. Elspeth, you see, was one of those females who are so beautiful that even other women can’t help liking ’em, and in her idiot way she was a lively and engaging soul. The fact that she was Scotch helped, too, for the Queen was in one of her Jacobite moods just then, and by the grace of God someone had read Waverley to Elspeth when she was a child, and taught her to recite ‘The Lady of the Lake’.

I had been dreading meeting Albert again, in case he mentioned his whoremongering Nephew Willy, now deceased, but all he did was say:

‘Ah, Colonel Flash-mann – haff you read Tocqueville’s L’Ancien Régime?’

I said I hadn’t, yet, but I’d be at the railway library first thing in the morning, and he looked doleful and went on:

‘It warns us that bureaucratic central government, far from curing the ills of revolution, can actually arouse them.’

I said I’d often thought that, now that he mentioned it, and he nodded and said: ‘Italy is very unsatisfactory,’ which brought our conversation to a close. Fortunately old Ellenborough, who’d been chief in India at the time of my Kabul heroics, was among those present, and he buttonholed me, which was a profound relief. And then the Queen addressed me, in that high sing-song of hers:

‘Your dear wife, Colonel Flashman, tells me that you are quite recovered from the rigours of your Russian adventures, which you shall tell us of presently. They seem to be a quite extraordinary people; Lord Granville writes from Petersburg that Lady Wodehouse’s Russian maid was found eating the contents of one of her ladyship’s dressing-table pots – it was castor oil pomatum for the hair! What a remarkable extravagance, was it not?’

That was my cue, of course, to regale them with a few domestic anecdotes of Russia, and its primitive ways, which went down well, with the Queen nodding approval and saying: ‘How barbarous! How strange!’ while Elspeth glowed to see her hero holding the floor. Albert joined in in his rib-tickling way to observe that no European state offered such fertile soil for the seeds of socialism as Russia did, and that he feared that the new Tsar had little intellect or character.

‘So Lord Granville says,’ was the Queen’s prim rejoinder, ‘but I do not think it is quite his place to make such observations on a royal personage. Do you not agree, Mrs Flashman?’

Old Ellenborough, who was a cheery, boozy buffer, said to me that he hoped I had tried to civilise the Russians a little by teaching them cricket, and Albert, who had no more humour than the parish trough, looked stuffy and says:

‘I am sure Colonel Flash-mann would do no such thing. I cannot unner-stend this passion for cricket; it seems to me a great waste of time. What is the proff-it to a younk boy in crouching motionless in a field for hours on end? Em I nott right, Colonel?’

‘Well, sir,’ says I, ‘I’ve looked out in the deep field myself long enough to sympathise with you; it’s a great fag, to be sure. But perhaps, when the boy’s a man, his life may depend on crouching motionless, behind a Khyber rock or a Burmese bush – so a bit of practice may not come amiss, when he’s young.’

Which was sauce, if you like, but I could never resist the temptation, in grovelling to Albert, to put a pinch of pepper down his shirt. It was in my character of bluff, no-nonsense Harry, too, and a nice reminder of the daring deeds I’d done. Ellenborough said ‘Hear, hear’, and even Albert looked only half-sulky, and said all diss-cipline was admirable, but there must be better ways of instilling it; the Prince of Wales, he said, should nott play cricket, but some more constructiff game.

After that we had tea, very informal, and Elspeth distinguished herself by actually prevailing on Albert to eat a cucumber sandwich; she’ll have him in the bushes in a minute, thinks I, and on that happy note our first visit concluded, with Elspeth going home on a cloud to Abergeldie.

But if it was socially useful, it wasn’t much of a holiday, although Elspeth revelled in it. She went for walks with the Queen, twice (calling themselves Mrs Fitzjames and Mrs Marmion, if you please), and even made Albert laugh when charades were played in the evening, by impersonating Helen of Troy with a Scotch accent. I couldn’t even get a grin out of him; we went shooting with the other gentlemen, and it was purgatory having to stalk at his pace. He was keen as mustard, though, and slaughtered stags like a Ghazi on hashish – you’ll hardly credit it, but his notion of sport was that a huge long trench should be dug so that we could sneak up on the deer unobserved; he’d have done it, too, but the local ghillies showed so much disgust at the idea that he dropped it. He couldn’t understand their objections, though; to him all that mattered was killing the beasts.

For the rest, he prosed interminably and played German music on the piano, with me applauding like hell. Things weren’t made easier by the fact that he and Victoria weren’t getting on too well just then; she had just discovered (and confided to Elspeth) that she was in foal for the ninth time, and she took her temper out on dear Albert – the trouble was, he was so bloody patient with her, which can drive a woman to fury faster than anything I know. And he was always right, which was worse. So they weren’t dealing at all well, and he spent most of the daylight hours tramping up Glen Bollocks, or whatever they call it, roaring ‘Ze gunn!’ and butchering every animal in view.

The only thing that seemed to cheer up the Queen was that she was marrying off her oldest daughter, Princess Vicky – the best of the whole family, in my view, a really pretty, green-eyed little mischief. She was to wed Frederick William of Prussia, who was due at Balmoral in a few weeks, and the Queen was full of it, Elspeth told me.

However, enough of the court gossip; it will give you some notion of the trivial way in which I was being forced to pass my time – toadying Albert, and telling the Queen how many acute accents there were on ‘déterminés’. The trouble with this kind of thing is that it dulls your wits, and your proper instinct for self-preservation, so that if a blow falls you’re caught clean offside, as I was on the night of September 22, 1856: I recollect the date absolutely because it was the day after Florence Nightingale came to the castle.

I’d never met her, but as the leading Crimean on the premises I was summoned to join in the tête-à-tête she had with the Queen in the afternoon. It was a frost, if you like; pious platitudes from the two of ’em, with Flashy passing the muffins and joining in when called on to agree that what our wars needed was more sanitation and texts on the wall of every dressing-station. There was one near-facer for me, and that was when Miss Nightingale (a cool piece, that) asked me calm as you like what regimental officers could do to prevent their men from contracting certain indelicate social infections from – hem-hem – female camp-followers of a certain sort; I near as dammit put my teacup in the Queen’s lap, but recovered to say that I’d never heard of any such thing, not in the Light Cavalry, anyway – French troops another matter, of course. Would you believe it, I actually made her blush, but I doubt if the Queen even knew what we were talking about. For the rest, I thought La Nightingale a waste of good womanhood; handsome face, well set up and titted out, but with that cold don’t-lay-a-lecherous-limb-on-me-my-lad look in her eye – the kind, in short, that can be all right if you’re prepared to spend time and trouble making ’em cry ‘Roger!’, but I seldom have the patience. Anywhere else I might have taken a squeeze at her, just by way of research, but a queen’s drawing-room cramps your style. (Perhaps it’s a pity I didn’t; being locked up for indecent assault on a national heroine couldn’t have been worse than the ordeal that was to begin a few hours later.)

Elspeth and I spent the following evening at a birthday party at one of the big houses in the neighbourhood; it was a cheery affair, and we didn’t leave till close on midnight to drive back to Abergeldie. It was a close, thundery night, with big rain-drops starting to fall, but we didn’t mind; I had taken enough drink on board to be monstrously horny, and if the drive had been longer and Elspeth’s crinoline less of a hindrance I’d have had at her on the carriage-seat. She got out at the lodge giggling and squeaking, and I chased her through the front door – and there was the messenger of doom, waiting in the hall. A tall chap, almost a swell, but with a jaw too long and an eye too sharp; very respectable, with a hard hat under his arm and a billy in his hip-pocket, I’ll wager. I know a genteel strong man from a government office when I see one.

He asked could he speak to me, so I took my arm from Elspeth’s waist, patted her towards the stairs with a whispered promise that I’d be up directly to sound the charge, and told him to state his business. He did that smart enough.

‘I am from the Treasury, Colonel Flashman,’ says he. ‘My name is Hutton. Lord Palmerston wishes to speak with you.’

It took me flat aback, slightly foxed that I was. My first thought was that he must want me to go back to London, but then he said: ‘His lordship is at Balmoral, sir. If you will be good enough to come with me – I have a coach.’

‘But, but … you said Lord Palmerston? The Prime … what the deuce? Palmerston wants me?’

‘At once, sir, if you please. The matter is urgent.’

Well, I couldn’t make anything of it. I never doubted it was genuine – as I’ve said, the man in front of me had authority written all over him. But it’s a fair start when you come rolling innocently home and are told that the first statesman of Europe is round the corner and wants you at the double – and now the fellow was positively ushering me towards the door.

‘Hold on,’ says I. ‘Give me a moment to change my shoes’ – what I wanted was a moment to put my head in the wash-bowl and think, and despite his insistence I snapped at him to wait, and hurried upstairs.

What the devil was Pam doing here – and what could he want with me? I’d only met him once, for a moment, before I went to the Crimea; I’d leered at him ingratiatingly at parties, too, but never spoken. And now he wanted me urgently – me, a mere colonel on half pay. I’d nothing on my conscience, either – leastways, not to interest him. I couldn’t see it, but there was nothing but to obey, so I went to my dressing-room, fretting, donned my hat and topcoat against the worsening weather, and remembered that Elspeth, poor child, must even now be waiting for her cross-buttocking lesson. Well, it was hard lines on her, but duty called, so I just popped my head round her door to call a chaste farewell – and there she was, dammit, reclining languorously on the coverlet like one of those randy classical goddesses, wearing nothing but the big ostrich-plume fan I’d brought her from Egypt, and her sniggering maid turning the lamp down low. Elspeth clothed could stop a monk in his tracks; naked and pouting expectantly over a handful of red feathers, she’d have made the Grand Inquisitor burn his books. I hesitated between love and duty for a full second, and then ‘The hell with Palmerston, let him wait!’ cries I, and was plunging for the bed before the abigail was fairly out of the room. Never miss the chance, as the Duke used to say.

‘Lord Palmerston? Oooo-ah! Harry – what do you mean?’

‘Ne’er mind!’ cries I, taking hold and bouncing away.

‘But Harry – such impatience, my love! And, dearest – you’re wearing your hat!’

‘The next one’s going to be a boy, dammit!’ And for a few glorious stolen moments I forgot Palmerston and minions in the hall, and marvelled at the way that superb idiot woman of mine could keep up a stream of questions while performing like a harem houri – we were locked in an astonishing embrace on her dressing-table stool, I recall, when there was a knock on the door, and the maid’s giggling voice piped through to say the gentleman downstairs was getting impatient, and would I be long.

‘Tell him I’m just packing my baggage,’ says I. ‘I’ll be down directly,’ and presently, keeping my mouth on hers to stem her babble of questions, I carried my darling tenderly back to the bed. Always leave things as you would wish to find them.

‘I cannot stay longer, my love,’ I told her. ‘The Prime Minister is waiting.’ And with bewildered entreaties pursuing me I skipped out, trousers in hand, made a hasty toilet on the landing, panted briefly against the wall, and then stepped briskly down. It’s a great satisfaction, looking back, that I kept the government waiting in such a good cause, and I set it down here as a deserved tribute to the woman who was the only real love of my life and as the last pleasant memory I was to have for a long time ahead.

It’s true enough, too, as Ko Dali’s daughter taught me, that there’s nothing like a good rattle for perking up an edgy chap like me. It had shaken me for a moment, and it still looked rum, that Palmerston should want to see me, but as we bowled through the driving rain to Balmoral I was telling myself that there was probably nothing in it after all; considering the good odour I stood in just then, hob-nobbing with royalty and being admired for my Russian heroics, it was far more likely to be fair news than foul. And it wasn’t like being bidden to the presence of one of your true ogres, like the old Duke or Bismarck or Dr Wrath-of-God Arnold (I’ve knocked tremulously on some fearsome doors in my time, I can tell you).

No, Pam might be an impatient old tyrant when it came to bullying foreigners and sending warships to deal with the dagoes, but everyone knew he was a decent, kindly old sport at bottom, who put folk at their ease and told a good story. Why, it was notorious that the reason he wouldn’t live at Downing Street, but on Piccadilly, was that he liked to ogle the good-lookers from his window, and wave to the cads and crossing-sweepers, who loved him because he talked plain English, and would stump up a handsome subscription for an old beaten prize-pug like Tom Sayers. That was Pam – and if anyone ever tells you that he was a politically unprincipled old scoundrel, who carried things with a high and reckless hand, I can only say that it didn’t seem to work a whit worse than the policies of more high-minded statesmen. The only difference I ever saw between them and Pam was that he did his dirty work bare-faced (when he wasn’t being deeper than damnation) and grinned about it.

So I was feeling pretty easy as we covered the three miles to Balmoral – and even pleasantly excited – which shows you how damned soft and optimistic I must have grown; I should have known that it’s never safe to get within range of princes or prime ministers. When we got to the castle I followed Hutton smartly through a side door, up some back-stairs, and along to heavy double doors where a burly civilian was standing guard; I gave my whiskers a martial twitch as he opened the door, and stepped briskly in.

You know how it can be when you enter a strange room – everything can look as safe and merry as ninepence, and yet there’s something in the air that touches you like an electric shock. It was here now, a sort of bristling excitement that put my nerves on edge in an instant. And yet there was nothing out of the ordinary to see – just a big, cheerful panelled room with a huge fire roaring under the mantel, a great table littered with papers, and two sober chaps bustling about it under the direction of a slim young fellow – Barrington, Palmerston’s secretary. And over by the fire were three other men – Ellenborough, with his great flushed face and his belly stuck out; a slim, keen-looking old file whom I recognised as Wood, of the Admiralty; and with his back to the blaze and his coat-tails up, the man himself, peering at Ellenborough with his bright, short-sighted eyes and looking as though his dyed hair and whiskers had just been rubbed with a towel – old Squire Pam as ever was. As I came in, his brisk, sharp voice was ringing out (he never gave a damn who heard him):

‘… so if he’s to be Prince Consort, it don’t make a ha’porth of difference, you see. Not to the country – or me. However, as long as Her Majesty thinks it does – that’s what matters, what? Haven’t you found that telegraph of Quilter’s yet, Barrington? – well, look in the Persian packet, then.’

And then he caught sight of me, and frowned, sticking out his long lip. ‘Ha, that’s the man!’ cries he. ‘Come in, sir, come in!’

What with the drink I’d taken, and my sudden nervousness, I tripped over the mat – which was an omen, if you like – and came as near as a toucher to oversetting a chair.

‘By George,’ says Pam, ‘is he drunk? All these young fellows are, nowadays. Here, Barrington, see him to a chair, before he breaks a window. There, at the table.’ Barrington pulled out a chair for me, and the three at the fireplace seemed to be staring ominously at me while I apologised and took it, especially Pam in the middle, with those bright steady eyes taking in every inch of me as he nursed his port glass and stuck a thumb into his fob – for all the world like the marshal of a Kansas trail-town surveying the street. (Which is what he was, of course, on a rather grand scale.)

He was very old at this time, with the gout and his false teeth forever slipping out, but he was evidently full of ginger tonight, and not in one of his easygoing moods. He didn’t beat about, either.

‘Young Flashman,’ growls he. ‘Very good. Staff colonel, on half pay at present, what? Well, from this moment you’re back on the full list, an’ what you hear in this room tonight is to go no further, understand? Not to anyone – not even in this castle. You follow?’

I followed, sure enough – what he meant was that the Queen wasn’t to know: it was notorious that he never told her anything. But that was nothing; it was his tone, and the solemn urgency of his warning, that put the hairs up on my neck.

‘Very good,’ says he again. ‘Now then, before I talk to you, Lord Ellenborough has somethin’ to show you – want your opinion of it. All right, Barrington, I’ll take that Persian stuff now, while Colonel Flashman looks at the damned buns.’

I thought I’d misheard him, as he limped past me and took his seat at the table-head, pawing impatiently among his papers. But sure enough, Barrington passed over to me a little lead biscuit-box, and Ellenborough, seating himself beside me, indicated that I should open it. I pushed back the lid, mystified, and there, in a rice-paper wrapping, were three or four greyish, stale-looking little scones, no bigger than captain’s biscuits.

‘There,’ says Pam, not looking up from his papers. ‘Don’t eat ’em. Tell his lordship what you make of those.’

I knew, right off; that faint eastern smell was unmistakable, but I touched one of them to make sure.

‘They’re chapattis, my lord,’ says I, astonished. ‘Indian chapattis.’

Ellenborough nodded. ‘Ordinary cakes of native food. You attach no signal significance to them, though?’

‘Why … no, sir.’

Wood took a seat opposite me. ‘And you can conjecture no situation, colonel,’ says he, in his dry, quiet voice, ‘in which the sight of such cakes might occasion you … alarm?’

Obviously Ministers of the Crown don’t ask damnfool questions for nothing, but I could only stare at him. Pam, apparently deep in his papers at the table-head, wheezing and sucking his teeth and muttering to Barrington, paused to grunt: ‘Serve the dam’ things at dinner an’ they’d alarm me,’ and Ellenborough tapped the biscuit box.

‘These chapattis came last week from India, by fast steam sloop. Sent by our political agent at a place called Jhansi. Know it? It’s down below the Jumna, in Maharatta country. For weeks now, scores of such cakes have been turning up among the sepoys of our native Indian garrison at Jhansi – not as food, though. It seems the sepoys pass them from hand to hand as tokens—’

‘Have you ever heard of such a thing?’ Wood interrupted.

I hadn’t, so I just shook my head and looked attentive, wondering what the devil this was all about, while Ellenborough went on:

‘Our political knows where they come from, all right. The native village constables – you know, the chowkidars – bake them in batches of ten, and send one apiece to ten different sepoys – and each sepoy is bound to make ten more, and pass them on, to his comrades, and so on, ad infinitum. It’s not new, of course; ritual cake-passing is very old in India. But there are three remarkable things about it: firstly, it happens only rarely; second, even the natives themselves don’t know why it happens, only that the cakes must be baked and passed; and third –’ he tapped the box again ‘– they believe that the appearance of the cakes foreshadows terrible catastrophe.’

He paused, and I tried to look impressed. For there was nothing out of the way in all this – straight from Alice in Wonderland, if you like, but when you know India and the amazing tricks the niggers can get up to (usually in the name of religion) you cease to be surprised. It seemed an interesting superstition – but what was more interesting was that two Ministers of the Government, and a former Governor-General of India, were discussing it behind closed doors – and had decided to let Flashy into the secret.

‘But there’s something more,’ Ellenborough went on, ‘which is why Skene, our political man at Jhansi, is treating the matter as one of urgency. Cakes like these have circulated among native troops, quite apart from civilians, on only three occasions in the past fifty years – at Vellore in ’06, at Buxar, and at Barrackpore. You don’t recall the names? Well, at each place, when the cakes appeared, the same reaction followed among the sepoys.’ He put on his House of Lords face and said impressively, ‘Mutiny.’

Looking back, I suppose I ought to have thrilled with horror at the mention of the dread word – but in fact all that occurred to me was the facetious thought that perhaps they ought to have varied the sepoys’ rations. I didn’t think much of the political man Skene’s judgement, either; I’d been a political myself, and it’s part of the job to scream at your own shadow, but if he – or Ellenborough, who knew India outside in – was smelling a sepoy revolt in a few mouldy biscuits – well, it was ludicrous. I knew John Sepoy (we all did, didn’t we?) for the most loyal ass who ever put on uniform – and so he should have been, the way the Company treated him. However, it wasn’t for me to venture an opinion in such august company, particularly with the Prime Minister listening: he’d pushed his papers aside and risen, and was pouring himself some more port.

‘Well, now,’ says he briskly, taking a hearty swig and rolling it round his teeth, ‘you’ve admired his lordship’s cakes, what? Damned unappetisin’ they look, too. All right, Barrington, your assistants can go – our special leaves at four, does it? Very well.’ He waited till the junior secretaries had gone, muttered something about ungodly hours and the Queen’s perversity in choosing a country retreat at the North Pole, and paced stiffly over to the fire, where he set his back to the mantel and glowered at me from beneath his gorse-bush brows, which was enough to set my dinner circulating in the old accustomed style.

‘Tokens of revolution in an Indian garrison,’ says he. ‘Very good. Been readin’ that report of yours again, Flashman – the one you made to Dalhousie last year, in which you described the discovery you made while you were a prisoner in Russia – about their scheme for invadin’ India, while we were busy in Crimea. Course, we say nothin’ about that these days – peace signed with Russia, all good fellowship an’ be damned, et cetera – don’t have to tell you. But somethin’ in your report came to mind when this cake business began.’ He pushed out his big lip at me. ‘You wrote that the Russian march across the Indus was to be accompanied by a native risin’ in India, fomented by Tsarist agents. Our politicals have been chasin’ that fox ever since – pickin’ up some interestin’ scents, of which these infernal buns are the latest. Now, then,’ he settled himself, eyes half-shut, but watching me, ‘tell me precisely what you heard in Russia, touchin’ on an Indian rebellion. Every word of it.’

So I told him, exactly as I remembered it – how Scud East and I had lain quaking in our nightshirts in the gallery at Starotorsk, and overheard about ‘Item Seven’, which was the Russian plan for an invasion of India. They’d have done it, too, but Yakub Beg’s riders scuppered their army up on the Syr Daria, with Flashy running about roaring with a bellyful of bhang, performing unconscious prodigies of valour. I’d set it all out in my report to Dalhousie, leaving out the discreditable bits (you can find those in my earlier memoirs, along with the licentious details). It was a report of nicely judged modesty, that official one, calculated to convince Dalhousie that I was the nearest thing to Hereward the Wake he was ever likely to meet – and why not? I’d suffered for my credit.

But the information about an Indian rebellion had been slight. All we’d discovered was that when the Russian army reached the Khyber, their agents in India would rouse the natives – and particularly John Company’s sepoys – to rise against the British. I didn’t doubt it was true, at the time; it seemed an obvious ploy. But that was more than a year ago, and Russia was no threat to India any longer, I supposed.

They heard me out, in a silence that lasted a full minute after I’d finished, and then Wood says quietly:

‘It fits, my lord.’

‘Too dam’ well,’ says Pam, and came hobbling back to his chair again. ‘It’s all pat. You see, Flashman, Russia may be spent as an armed power, for the present – but that don’t mean she’ll leave us at peace in India, what? This scheme for a rebellion – by George, if I were a Russian political, invasion or no invasion, I fancy I could achieve somethin’ in India, given the right agents. Couldn’t I just, though!’ He growled in his throat, heaving restlessly and cursing his gouty foot. ‘Did you know, there’s an Indian superstition that the British Raj will come to an end exactly a hundred years after the Battle of Plassey?’ He picked up one of the chapattis and peered at it. ‘Dam’ thing isn’t even sugared. Well, the hundredth anniversary of Plassey falls next June the twenty-third. Interestin’. Now then, tell me – what d’you know about a Russian nobleman called Count Nicholas Ignatieff?’

He shot it at me so abruptly that I must have started a good six inches. There’s a choice collection of ruffians whose names you can mention if you want to ruin my digestion for an hour or two – Charity Spring and Bismarck, Rudi Starnberg and Wesley Hardin, for example – but I’d put N. P. Ignatieff up with the leaders any time. He was the brute who’d nearly put paid to me in Russia – a gotch-eyed, freezing ghoul of a man who’d dragged me half way to China in chains, and threatened me with exposure in a cage and knouting to death, and like pleasantries. I hadn’t cared above half for the conversation thus far, with its bloody mutiny cakes and the sinister way they kept dragging in my report to Dalhousie – but at the introduction of Ignatieff’s name my bowels began to play the Hallelujah Chorus in earnest. It took me all my time to keep a straight face and tell Pam what I knew – that Ignatieff had been one of the late Tsar’s closest advisers, and that he was a political agent of immense skill and utter ruthlessness; I ended with a reminiscence of the last time I’d seen him, under that hideous row of gallows at Fort Raim. Ellenborough exclaimed in disgust, Wood shuddered delicately, and Pam sipped his port.

‘Interestin’ life you’ve led,’ says he. ‘Thought I remembered his name from your report – he was one of the prime movers behind the Russian plan for invasion an’ Indian rebellion, as I recall. Capable chap, what?’

‘My lord,’ says I, ‘he’s the devil, and that’s a fact.’

‘Just so,’ says Pam. ‘An’ the devil will find mischief.’ He nodded to Ellenborough. ‘Tell him, my lord. Pay close heed to this, Flashman.’

Ellenborough cleared his throat and fixed his boozy spaniel eyes on me. ‘Count Ignatieff,’ says he, ‘has made two clandestine visits to India in the past year. Our politicals first had word of him last autumn at Ghuznee; he came over the Khyber disguised as an Afridi horse-coper, to Peshawar. There we lost him – as you might expect, one disguised man among so many natives—’

‘But my lord, that can’t be!’ I couldn’t help interrupting. ‘You can’t lose Ignatieff, if you know what to look for. However he’s disguised, there’s one thing he can’t hide – his eyes! One of em’s half-brown, half-blue!’

‘He can if he puts a patch over it,’ says Ellenborough. ‘India’s full of one-eyed men. In any event, we picked up his trail again – and on both occasions it led to the same place – Jhansi. He spent two months there, all told, usually out of sight, and our people were never able to lay a hand on him. What he was doing, they couldn’t discover – except that it was mischief. Now, we see what the mischief was –’ and he pointed to the chapattis. ‘Brewing insurrection, beyond a doubt. And having done his infernal work – back over the hills to Afghanistan. This summer he was in St Petersburg – but from what our politicals did learn, he’s expected back in Jhansi again. We don’t know when.’

No doubt it was the subject under discussion, but there didn’t seem to be an ounce of heat coming from the blazing fire behind me; the room felt suddenly cold, and I was aware of the rain slashing at the panes and the wind moaning in the dark outside. I was looking at Ellenborough, but in his face I could see Ignatieff’s hideous parti-coloured eye, and hear that soft icy voice hissing past the long cigarette between his teeth.

‘Plain enough, what?’ says Pam. ‘The mine’s laid, in Jhansi – an’ if it explodes … God knows what might follow. India looks tranquil enough – but how many other Jhansis, how many other Ignatieffs, are there?’ He shrugged. ‘We don’t know, but we can be certain there’s no more sensitive spot than this one. The Russians have picked Jhansi with care – we only annexed it four years ago, on the old Raja’s death, an’ we’ve still barely more than a foothold there. Thug country, it used to be, an’ still pretty wild, for all it’s one of the richest thrones in India. Worst of all, it’s ruled by a woman – the Rani, the Raja’s widow. She was old when she married him, I gather, an’ there was no legitimate heir, so we took it under our wing – an’ she didn’t like it. She rules under our tutelage these days – but she remains as implacable an enemy as we have in India. Fertile soil for Master Ignatieff to sow his plots.’

He paused, and then looked straight at me. ‘Aye – the mine’s laid in Jhansi. But precisely when an’ where they’ll try to fire it, an’ whether it’ll go off or not … this we must know – an’ prevent at all costs.’

The way he said it went through me like an icicle. I’d been sure all along that I wasn’t being lectured for fun, but now, looking at their heavy faces, I knew that unless my poltroon instinct was sadly at fault, some truly hellish proposal was about to emerge. I waited quaking for the axe to fall, while Pam stirred his false teeth with his tongue – which was a damned unnerving sight, I may tell you – and then delivered sentence.

‘Last week, the Board of Control decided to send an extraordinary agent to Jhansi. His task will be to discover what the Russians have been doing there, how serious is the unrest in the sepoy garrison, and to deal with this hostile beldam of a Rani by persuadin’ her, if possible, that loyalty to the British Raj is in her best interest.’ He struck his finger on the table. ‘An’ if an’ when this man Ignatieff returns to Jhansi again – to deal with him, too. Not a task for an ordinary political, you’ll agree.’

No, but I was realising, with mounting horror, who they did think it was a task for. But I could only sit, with my spine dissolving and my face set in an expression of attentive idiocy, while he went inexorably on.

‘The Board of Control chose you without hesitation, Flashman. I approved the choice myself. You don’t know it, but I’ve been watchin’ you since my time as Foreign Secretary. You’ve been a political – an’ a deuced successful one. I daresay you think that the work you did in Middle Asia last year has gone unrecognised, but that’s not so.’ He rumbled at me impressively, wagging his great fat head. ‘You’ve the highest name as an active officer, you’ve proved your resource – you know India – fluent in languages – includin’ Russian, which could be of the first importance, what? You know this man Ignatieff, by sight, an’ you’ve bested him before. You see, I know all about you, Flashman,’ you old fool, I wanted to shout, you don’t know anything of the bloody sort; you ain’t fit to be Prime Minister, if that’s what you think, ‘and I know of no one else so fitted to this work. How old are you? Thirty-four – young enough to go a long way yet – for your country and yourself.’ And the old buffoon tried to look sternly inspiring, with his teeth gurgling.

It was appalling. God knows I’ve had my crosses to bear, but this beat all. As so often in the past, I was the victim of my own glorious and entirely unearned reputation – Flashy, the hero of Jallalabad, the last man out of the Kabul retreat and the first man into the Balaclava battery, the beau sabreur of the Light Cavalry, Queen’s Medal, Thanks of Parliament, darling of the mob, with a liver as yellow as yesterday’s custard, if they’d only known it. And there was nothing, with Pam’s eye on me, and Ellenborough and Wood looking solemnly on, that I could do about it. Oh, if I’d followed my best instincts, I could have fled wailing from the room, or fallen blubbering at some convenient foot – but of course I didn’t. With sick fear mounting in my throat, I knew that I’d have to go, and that was that – back to India, with its heat and filth and flies and dangers and poxy niggers, to undertake the damnedest mission since Bismarck put me on the throne of Strackenz.