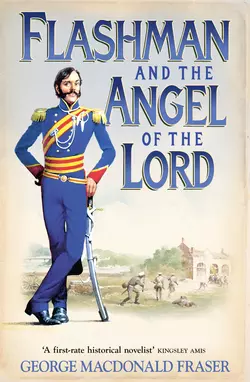

Flashman and the Angel of the Lord

Flashman and the Angel of the Lord

George MacDonald Fraser

Coward, scoundrel, lover and cheat, but there is no better man to go into the jungle with. Join Flashman in his adventures as he survives fearful ordeals and outlandish perils across the four corners of the world.A hasty retreat from the boudoir would normally suffice when caught with a wanton young wife. But when her husband turns out to be a high court judge, a change of continents is called for, as Flashman sets off to America again.

Copyright (#u827aa438-3e08-5add-bd24-a5af0611f347)

Harper

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by Harvill 1994

Copyright © George MacDonald Fraser 1994

How Did I Get the Idea of Flashman? © The Beneficiaries of the Literary Estate of George MacDonald Fraser 2015

Map © John Gilkes 2015

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

Cover illustration © Gino D’Achille

George MacDonald Fraser asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it, while at times based on historical events and figures, are the work of the author’s imagination.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780007217205

Ebook Edition © 2015 ISBN: 9780007325696

Version: 2015-07-14

The following piece was found in the author’s study in 2013 by the Estate of George MacDonald Fraser.

How Did I Get the Idea of Flashman? (#u827aa438-3e08-5add-bd24-a5af0611f347)

‘How did you get the idea of Flashman?’ and ‘When are we going to get his U.S. Civil War memoirs?’ are questions which I have ducked more often than I can count. To the second, my invariable response is ‘Oh, one of these days’. Followed, when the inquirer is an impatient American, by the gentle reminder that to an old British soldier like Flashman the unpleasantness between the States is not quite the most important event of the nineteenth century, but rather a sideshow compared to the Mutiny or Crimea. Before they can get indignant I add hastily that his Civil War itinerary is already mapped out; this is the only way of preventing them from telling me what it ought to be.

To the question, how did I get the idea, I simply reply that I don’t know. Who ever knows? Anthony Hope conceived The Prisoner of Zenda on a walk from Westminster to the Temple, but I doubt if he could have said, after the calendar month it took him to write the book, what triggered the idea. In my case, Flashman came thundering out of the mists of forty years living and dreaming, and while I can list the ingredients that went to his making, heaven only knows how and when they combined.

One thing is sure: the Flashman Papers would never have been written if my fellow clansman Hugh Fraser, Lord Allander, had confirmed me as editor of the Glasgow Herald in 1966. But he didn’t, the canny little bandit, and I won’t say he was wrong. I wouldn’t have lasted in the job, for I’d been trained in a journalistic school where editors were gods, and in three months as acting chief my attitude to management, front office, and directors had been that of a seigneur to his serfs – I had even put Fraser’s entry to the House of Lords on an inside page, assuring him that it was not for the Herald, his own paper, to flaunt his elevation, and that a two-column picture of him was quite big enough. How cavalier can you get?

And doubtless I had other editorial shortcomings. In any event, faced with twenty years as deputy editor (which means doing all the work without getting to the big dinners), I promised my wife I would ‘write us out of it’. In a few weeks of thrashing the typewriter at the kitchen table in the small hours, Flashman was half-finished, and likely to stay that way, for I fell down a waterfall, broke my arm, and lost interest – until my wife asked to read what I had written. Her reaction galvanised me into finishing it, one draft, no revisions, and for the next two years it rebounded from publisher after publisher, British and American.

I can’t blame them: the purported memoir of an unregenerate blackguard, bully, and coward resurrected from a Victorian school story is a pretty eccentric subject. By 1968 I was ready to call it a day, but thanks to my wife’s insistence and George Greenfield’s matchless knowledge of the publishing scene, it found a home at last with Herbert Jenkins, the manuscript looking, to quote Christopher MacLehose, as though it had been round the world twice. It dam’ nearly had.

They published it as it stood, with (to me) bewildering results. It wasn’t a bestseller in the blockbuster sense, but the reviewers were enthusiastic, foreign rights (starting with Finland) were sold, and when it appeared in the U.S.A. one-third of forty-odd critics accepted it as a genuine historical memoir, to the undisguised glee of the New York Times, which wickedly assembled their reviews. ‘The most important discovery since the Boswell Papers’ is the one that haunts me still, for if I was human enough to feel my lower ribs parting under the strain, I was appalled, sort of.

You see, while I had written a straightforward introduction describing the ‘discovery’ of the ‘Papers’ in a saleroom in Ashby-de-la-Zouche (that ought to have warned them), and larded it with editorial ‘foot-notes’, there had been no intent to deceive; for one thing, while I’d done my best to write, first-person, in Victorian style, I’d never imagined that it would fool anybody. Nor did Herbert Jenkins. And fifty British critics had recognised it as a conceit. (The only one who was half-doubtful was my old chief sub on the Herald; called on to review it for another paper, he demanded of the Herald’s literary editor: ‘This book o’ Geordie’s isnae true, is it?’ and on being assured that it wasn’t, exclaimed: ‘The conniving bastard!’, which I still regard as a high compliment.)

With the exception of one left-wing journal which hailed it as a scathing attack on British imperialism, the press and public took Flashman, quite rightly, at face value, as an adventure story dressed up as the memoirs of an unrepentant old cad who, despite his cowardice, depravity and deceit, had managed to emerge from fearful ordeals and perils an acclaimed hero, his only redeeming qualities being his humour and shameless honesty as a memorialist. I was gratified, if slightly puzzled to learn that the great American publisher, Alfred Knopf, had said of the book: ‘I haven’t heard this voice in fifty years’, and that the Commissioner of Metropolitan Police was recommending it to his subordinates. My interest increased as I wrote more Flashman books, and noted the reactions.

I was, several critics agreed, a satirist. Taking revenge on the nineteenth century on behalf of the twentieth, said one. Waging war on Victorian hypocrisy, said another. Plainly under the influence of Conrad, said yet another. A full-page review in a German paper took me flat aback when my eye fell on the word ‘Proust’ in the middle of it. I don’t read German, so for all I know the review may have been maintaining that Proust was a better stand-off half than I was, or used more semi-colons. But there it was, and it makes you think. And a few years ago a highly respected religious journal said that the Flashman Papers deserved recognition as the work of a sensitive moralist, and spoke of service not only to literature and history, but to the study of ethics.

My instant reaction to this was to paraphrase Poins: ‘God send me no worse fortune, but I never said so!’ while feeling delighted that someone else had said it, and then reflecting solemnly that this was a far cry from long nights with cold tea and cigarettes, scheming to get Flashman into the passionate embrace of the Empress of China, or out of the toils of a demented dwarf on the edge of a snake-pit. But now, beyond remarking that the anti-imperial left-winger was sadly off the mark, that the Victorians were mere amateurs in hypocrisy compared to our own brainwashed, sanctimonious, self-censoring and terrified generation, and that I hadn’t read a word of Conrad by 1966 (and my interest in him since has been confined to Under WesternEyes, in the hope that I might persuade Dick Lester to film it as only he could), I have no comments to offer on opinions of my work. I know what I’m doing – at least, I think I do – and the aim is to entertain (myself, for a start) while being true to history, to let Flashman comment on human and inhuman nature, and devil take the romantics and the politically correct revisionists both. But my job is writing, not explaining what I’ve written, and I’m well content and grateful to have others find in Flashy whatever they will (I’ve even had letters psychoanalysing the brute), and return to the question with which I began this article.

A life-long love affair with British imperial adventure, fed on tupenny bloods, the Wolf of Kabul and Lionheart Logan (where are they now?), the Barrack-Room Ballads, films like Lives of aBengal Lancer and The Four Feathers, and the stout-hearted stories for boys which my father won as school prizes in the 1890s; the discovery, through Scott and Sabatini and Macaulay, that history is one tremendous adventure story; soldiering in Burma, and seeing the twilight of the Raj in all its splendour; a newspaper-trained lust for finding the truth behind the received opinion; being a Highlander from a family that would rather spin yarns than eat … I suppose Flashman was born out of all these things, and from reading Tom Brown’s Schooldays as a child – and having a wayward cast of mind.

Thanks to that contrary streak (I always half-hoped that Rathbone would kill Flynn, confounding convention and turning the story upside down – Basil gets Olivia, Claude Rains triumphs, wow!), I recognised Flashman on sight as the star of Hughes’ book. Fag-roasting rotter and poltroon he might be, he was nevertheless plainly box-office, for he had the looks, swagger and style (‘big and strong’, ‘a bluff, offhand manner’, and ‘considerable powers of being pleasant’, according to his creator) which never fail to cast a glamour on villainy. I suspect Hughes knew it, too, and got rid of him before he could take over the book – which loses all its spirit and zest once Flashy has made his disgraced and drunken exit.

[He was, by the way, a real person; this I learned only recently. A letter exists from one of Hughes’ Rugby contemporaries which is definite on the point, but tactfully does not identify him. I have sometimes speculated about one boy who was at Rugby in Hughes’ day, and who later became a distinguished soldier and something of a ruffian, but since I haven’t a shred of evidence to back up the speculation, I keep it to myself.]

What became of him after Rugby seemed to me an obvious question, which probably first occurred to me when I was about nine, and then waited thirty years for an answer. The Army, inevitably, and since Hughes had given me a starting-point by expelling him in the late 1830s, when Lord Cardigan was in full haw-haw, and the Afghan War was impending … just so. I began with no idea of where the story might take me, but with Victorian history to point the way, and that has been my method ever since: choose an incident or campaign, dig into every contemporary source available, letters, diaries, histories, reports, eye-witness, trivia (and fictions, which like the early Punch are mines of detail), find the milestones for Flashy to follow, more or less, get impatient to be writing, and turn him loose with the research incomplete, digging for it as I go and changing course as history dictates or fancy suggests.

In short, letting history do the work, with an eye open for the unexpected nuggets and coincidences that emerge in the mining process – for example, that the Cabinet were plastered when they took their final resolve on the Crimea, that Pinkerton the detective had been a trade union agitator in the very place where Flashman was stationed in the first book, that Kipling’s The Man Who Would Be King had a factual basis, or that Bismarck and Lola Montez were in London in the same week (of 1842, if memory serves, which it often doesn’t: whenever Flashman has been a subject on Mastermind I have invariably scored less than the contestants).

Visiting the scenes helps; I’d not have missed Little Big Horn, the Borneo jungle rivers, Bent’s Fort, or the scruffy, wonderful Gold Road to Samarkand, for anything. Seeking out is half the fun, which is one reason why I decline all offers of help with research (from America, mostly). But the main reason is that I’m a soloist, giving no hints beforehand, even to publishers, and permitting no editorial interference afterwards. It may be tripe, but it’s my tripe – and I do strongly urge authors to resist encroachments on their brain-children, and trust their own judgment rather than that of some zealous meddler with a diploma in creative punctuation who is just dying to get into the act.

One of the great rewards of writing about my old ruffian has been getting and answering letters, and marvelling at the kindness of readers who take the trouble to let me know they have enjoyed his adventures, or that he has cheered them up, or turned them to history. Sitting on the stairs at 4 a.m. talking to a group of students who have phoned from the American Midwest is as gratifying as learning from a university lecturer that he is using Flashman as a teaching aid. Even those who want to write the books for you, or complain that he’s a racist (of course he is; why should he be different from the rest of humanity?), or insist that he isn’t a coward at all, but just modest, and they’re in love with him, are compensated for by the stalwarts who’ve named pubs after him (in Monte Carlo, and somewhere in South Africa, I’m told), or have formed societies in his honour. They’re out there, believe me, the Gandamack Delopers of Oklahoma, and Rowbotham’s Mosstroopers, and the Royal Society of Upper Canada, with appropriate T-shirts.

I have discovered that when you create – or in my case, adopt and develop – a fictional character, and take him through a series of books, an odd thing happens. He assumes, in a strange way, a life of his own. I don’t mean that he takes you over; far from it, he tends to hive off on his own. At any rate, you find that you’re not just writing about him: you are becoming responsible for him. You’re not just his chronicler: you are also his manager, trainer, and public relations man. It’s your own fault – my own fault – for pretending that he’s real, for presenting his adventures as though they were his memoirs, putting him in historical situations, giving him foot-notes and appendices, and inviting the reader to accept him as a historical character. The result is that about half the letters I get treat him as though he were a person in his own right – of course, people who write to me know that he’s nothing of the sort – well, most of them realise it: I occasionally get indignant letters from people complaining that they can’t find him in the Army List or the D.N.B., but nearly all of them know he’s fiction, and when they pretend that he isn’t, they’re just playing the game. I started it, so I can’t complain.

When Hughes axed Flashman from Tom Brown’s Schooldays, brutally and suddenly (on page 170, if I remember rightly), it seemed a pretty callous act to abandon him with all his sins upon him, just at the stage of adolescence when a young fellow needs all the help and understanding he can get. So I adopted him, not from any charitable motives, but because I realised that there was good stuff in the lad, and that with proper care and guidance something could be made out of him.

And I have to say that with all his faults (what am I saying, because of his faults) young Flashy has justified the faith I showed in him. Over the years he and I have gone through several campaigns and assorted adventures, and I can say unhesitatingly that coward, scoundrel, toady, lecher and dissembler though he may be, he is a good man to go into the jungle with.

George MacDonald Fraser

Dedication (#u827aa438-3e08-5add-bd24-a5af0611f347)

For Kath, ten times over

Contents

Cover (#ub9d1f6ca-8810-5d24-b22b-e786a8f4e253)

Title Page (#uf45bb02e-35ce-5bd3-92cb-4c061814c664)

Copyright

How Did I Get the Idea of Flashman?

Dedication

Explanatory Note

Map (#u2a4e976f-5851-5f1e-80f6-ab7897847347)

Chapter 1 (#ue4d85b5a-43eb-5a16-952b-51f93fb70856)

Chapter 2 (#u83c3e6c2-2182-5b6e-a6df-adff5b6891b1)

Chapter 3 (#u6a5b8e02-5f9d-5106-b9ce-df1318d7cd83)

Chapter 4 (#u2c9bf375-ab6b-5201-8fe4-d9194d1816e7)

Chapter 5 (#u6ae784e5-23d2-5f11-8cd9-6a3fe58de7f3)

Chapter 6 (#u02f25e1b-4297-5b6e-be7b-0f658ebf58da)

Chapter 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Appendix I

Appendix II

Appendix III

Footnotes

Notes

About the Author

The FLASHMAN Papers: In chronological order

The FLASHMAN Papers: In order of publication

Also by George MacDonald Fraser

About the Publisher

EXPLANATORY NOTE (#u827aa438-3e08-5add-bd24-a5af0611f347)

Of all the roles played by Sir Harry Flashman, V.C., in the course of his distinguished and deplorable career, that of crusader must seem the least likely. The nine volumes of his Papers which have been presented to the public since their discovery in a Midlands saleroom in 1966 make a scandalous catalogue in which there is little trace of decent feeling, let alone altruism. From the day of his expulsion from Rugby School in the late 1830s (memorably described in Tom Brown’s Schooldays), Flashman the man fulfilled the disgraceful promise of Flashman the boy; the toadying bounder and bully matured into the cowardly profligate and scoundrel who, by chance and shameless opportunism, became one of the most renowned heroes of the Victorian age, unwilling leader of the Light Brigade, fleeing survivor of Afghanistan and Little Big Horn, tarnished paladin of Crimea and the Mutiny, and cringing chronicler of many another conflict, disaster, and intrigue in which he bore an inglorious but seldom unprofitable part.

So it is with initial disbelief that one finds him, in this tenth volume of his memoirs, not only involved but taking a lead in an enterprise which, if hopeless and misguided, still shines with the lustre of heroic self-sacrifice and occupies an honoured niche in the pantheon of freedom. John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry was a dreadful folly which ended in bloody and inevitable failure and helped to bring on the most catastrophic of all civil wars, yet its aim was a great and worthy one; the road to hell was never paved with nobler intentions. Needless to say, they were not Flashman’s. He came to Harper’s Ferry with the utmost reluctance, through the malice of old enemies and the delusions of old friends, and behaved with characteristic perfidy in every way but one: his eye for events and people was as clear and scrupulous as ever, and it may be that his narrative casts a new and unexpected light on a critical moment in American history, and on notable figures of the ante-bellum years – among them the President Who Never Was, a legendary detective and secret agent, and the strange, terrible, simple visionary, known to the world only by a name and a song, who set out to destroy slavery with twenty men and forty rounds apiece.

It is an amazing story, even for Flashman, but my confidence in that honesty which he brought to his writing (if to nothing else) seems to be justified by the exactness with which his account fits the known facts. As with previous packets of the Papers, I have observed the wishes of their custodian, Mr Paget Morrison, and confined myself to amending the author’s spelling and providing footnotes and appendices.

G.M.F.

As I sat by the lake at Gandamack t’other day, sipping my late afternoon brandy in the sun, damning the great-grandchildren for pestering the ducks, and reflecting on the wigging I’d get from Elspeth when I took them in to tea covered in dirt and toffee, there was a brass band playing on a gramophone up at the house, a distant drowsy thumping that drifted down the lawn and under the trees. I guess I must have hummed along or waved my flask to the old familiar march, for presently the villain Augustus (a frightful handle to fix on a decent enough urchin, but no work of mine) detached himself from the waterweed and came to stand snottering before me with his head on one side, thoughtful-like.

‘I say, Great-gran’papa,’ says he, ‘that’s Gory Halooyah.’

‘So it is, young gallows,’ says I, ‘and Gory Halooyah is what you’ll catch when Great-grandmama sees the state of you. Where the devil’s your other shoe?’

‘Sunk,’ says he, and gave tongue: ‘“Jombrown’s body lies a-moulderin’ inna grave, Jombrown’s body lies –”’

‘Oh! Gweat-gwampapa said a wicked word!’ squeals virtuous Jemima, a true Flashman, as beautiful as she is obnoxious. ‘I heard him! He said “d—l”!’ She pronounced it ‘d’l’. ‘Gweat-gwanmama says people who say such fings go to the bad fire!’ Bad fire, indeed – my genteel Elspeth has never forgotten the more nauseating euphemisms of her native Paisley.

‘He shan’t, so there!’ cries my loyal little Alice, another twig off the old tree, being both flirt and toady. She jumped on the bench and clung to my arm. ‘’Cos I shan’t let him go to bad fires, shall I, Great-grampapa?’ Yearning at me with those great forget-me-not eyes, four years old and innocent as Cleopatra.

‘’Fraid you won’t have a vote on the matter, m’dear.’

‘“Devil” ain’t a bad word, anyway,’ says John, rising seven and leader of the pack. ‘The Dean said it in his sermon last Sunday – devil! He said it twice – devil!’ he repeated, with satisfaction. ‘So bad scran to you, Jemima!’ Hear, hear. Stout lad, John.

‘That was in church!’ retorts Jemima, who has the makings of a fine sea-lawyer, bar her habit of sticking out her tongue. ‘It’s all wight in church, but if you say it outside it’s vewwy dweadful, an’ God will punish you!’ Little Baptist.

‘What’s moulderin’ mean, Great-gran’papa?’ asks Augustus.

‘All rotten an’ stinkin’,’ says John. ‘It’s what happens when you get buried. You go all squelchy, an’ the worms eat you –’

‘Eeesh!’ Words cannot describe the ecstasy of Alice’s exclamation. ‘Was Jombrown like that, Great-grampapa, all rottish –’

‘Not as I recall, no. His toes stuck out of the ends of his boots sometimes, though.’

This produced hysterics of mirth, as I’d known it would, except in John, who’s a serious infant, given to searching cross-examination.

‘I say! Did you know him, Great-grandpapa – John Brown in the song?’

‘Why, yes, John, I knew him … long time ago, though. Who told you about him?’

‘Miss Prentice, in Sunday School,’ says he, idly striking his cousin, who was trying to detach Alice from me by biting her leg. ‘She says he was the Angel of the Lord who got hung for freeing all the niggers in America.’

‘You oughtn’t to say “niggers”.’ Jemima again, absolutely, removing her teeth from Alice and climbing across to possess my other arm. ‘It’s not nice. You should say “negwoes”, shouldn’t you, Gweat-gwampapa? I always say “negwoes”,’ she added, oozing piety.

‘What should you call them, Great-grandpapa?’ asks John.

‘Call ’em what you like, my son. It’s nothing to what they’ll call you.’

‘I always say “negwoes” –’

‘Great-gran’papa says “niggers”,’ observes confounded Augustus. ‘Lots an’ lots of times.’ He pointed a filthy accusing finger. ‘You said that dam’ nigger, Jonkins, the boxer-man –’

‘Johnson, child, Jack Johnson.’

‘– you said he wanted takin’ down a peg or two.’

‘Did I, though? Yes, Jemima dearest, I know Gus has said another wicked word, but ladies shouldn’t notice, you know –’

‘What’s a peggatoo?’ asks Alice, twining my whiskers.

‘A measure of diminution of self-esteem, precious … yes, Jemima, I’ve no doubt you’re going to peach to Great-grandmama about Gus saying “damn”, but if you do you’ll be saying it yourself, mind … What, Gus? Yes, very well, if I said that about the boxer-man, you may be sure I meant it. But you know, old fellow, when you call people names, it depends who you’re talking about …’ It does, too. Flash coons like Johnson

and the riff-raff of the levees and most of our Aryan brethren are one thing – but if you’ve seen Ketshwayo’s Nokenke regiment stamping up the dust and the assegais drumming on the ox-hide shields, ‘’Suthu, ’suthu! ’s-jee, ’s-jee!’ as they sweep up the slope to Little Hand … well, that’s black of a different colour, and you find another word for those fellows. And God forbid I should offend Miss Prentice, so …

‘I think it best you should say “negroes”, children. That’s the polite word, you see –’

‘What about nigger minstrels?’ asks Alice, excavating my collar.

‘That’s all right ’cos they’re white underneath,’ says John impatiently. ‘Shut your potato-trap, Alice – I want to hear about John Brown, and how he freed all the … the negro slaves in America, didn’t he, Great-grandpapa?’

‘Well, now, John … no, not exactly …’ And then I stopped, and took a pull at my flask, and thought about it. After all, who am I to say he didn’t? It was coming anyway, but if it hadn’t been for old J.B. and his crack-brained dreams, who can tell how things might have panned out? Little nails hold the hinge of history, as Bismarck remarked (he would!) the night we set out for Tarlenheim … and didn’t Lincoln himself say that Mrs Stowe was the little lady who started the great war, with Uncle Tom’s Cabin? Well, Ossawatomie Brown, mad and murderous old horse-thief that he was, played just as big a part in setting the darkies free as she did – aye, or Lincoln or Garrison or any of them, I reckon. I did my bit myself – not willingly, you may be sure, and cursing Seward and Pinkerton every step of the way that ghastly night … and as I pondered it, staring across the lake to the big oak casting its first evening shadow, the shrill voices of the grandlings seemed to fade away, and in their place came the harsh yells and crash of gunshots in the dark, and instead of the scent of roses there was the reek of black powder smoke filling the engine-house, the militia’s shots shattering timber and whining about our ears … young Oliver bleeding his life out on the straw … the gaunt scarecrow with his grizzled beard and burning eyes, thumbing back the hammer of his carbine … ‘Stand firm, men! Sell your lives dearly! Don’t give in now!’ … and Jeb Stuart’s eyes on mine, willing me (I’ll swear) to pull the trigger …

‘Wake up, Great-grandpapa – do!’ ‘Tell us about Jombrown!’ ‘Yes, wiv his toes stickin’ out, all stinky!’ ‘Tell us, tell us …!’

I came back from the dark storm of Harper’s Ferry to the peaceful sunshine of Leicestershire, and the four small faces regarding me with that affectionate impatience that is the crowning reward of great-grandfatherhood: John, handsome and grave and listening; Jemima a year younger, prim ivory perfection with her long raven hair and lashes designed for sweeping hearts (Selina’s inevitable daughter); little golden Alice, Elspeth all over again; and the babe Augustus bursting with sin beneath the mud, a Border Ruffian in a sodden sailor suit … and the only pang is that at ninety-one

you can’t hope to see ’em grown …

‘John Brown, eh? Well, it’s a long story, you know – and Great-grandmama will be calling us for tea presently … no, Alice, he didn’t have wings, although Miss Prentice is quite right, they did call him the Angel of the Lord … and the Avenging Angel, too …’

‘What’s ’venging?’

‘Getting your own back … no, John, he was quite an ordinary chap, really, rather thin and bony and shabby, with a straggly beard and very bright grey eyes that lit up when he was angry, ever so fierce and grim! But he was quite a kindly old gentleman, too –’

‘Was he as old as you?’

‘Heavens, child, no one’s that old! He was oldish, but pretty spry and full of beans … let’s see, what else? He was a capital cook, why, he could make ham and eggs, and brown fried potatoes to make your mouth water –’

‘Did he make kedgewee? I hate howwid old kedgewee, ugh!’

‘What about the slaves, and him killing lots of people, and getting hung?’ John shook my knee in his impatience.

‘Well, John, I suppose he did kill quite a few people … How, Gus? Why, with his pistols – he had two, just like the cowboys, and he could pull them in a twinkling, ever so quickly.’ And dam’ near blew your Great-grandpapa’s head off, one second asleep and the next blasting lead all over the shop, curse him. ‘And with his sword … although that was before I knew him. Mind you, he had another sword, in our last fight – and you’ll never guess who it had once belonged to. Frederick the Great! What d’you think of that?’

‘Who’s Frederick the Great?’

‘German king, John. Bit of a tick, I believe; used scent and played the flute.’

‘I think Jombrown was howwid!’ announced Jemima. ‘Killing people is wrong!’

‘Not always, dearest. Sometimes you have to, or they’ll kill you.’

‘Great-gran’papa used to kill people, lots of times,’ protests sturdy Augustus. ‘Great-gran’mama told me, when he was a soldier, weren’t you? Choppin’ ’em up, heaps of –’

‘That’s quite diffewent,’ says Jemima, with an approving smile which may well lead me to revise my will in her favour. ‘It’s pwoper for soldiers to kill people.’ And pat on her words came an echo from half a century ago, the deep level voice of J.B. himself, recalling the slaughter of Pottawatomie … ‘They had a right to be killed.’ It was a warm afternoon, but I found myself shivering.

‘Great-grandpapa’s tired,’ whispers John. ‘Let’s go in for tea.’

‘What – tired? Not a bit of it!’ You can’t have grandlings taking pity on you, even at ninety-one. ‘But tea, what? Capital idea! Who’s for a bellyful of gingerbread, eh? Tell you what, pups – you make yourselves decent, straighten your hair, find Gus’s other shoe, put your socks on, Alice – yes, Jemima, you look positively queenly – and we’ll march up to tea, shall we? At least, you lot will, while I call the step and look after remounts. Won’t that be jolly? And we’ll sing his song as we go –’

‘Jombrown’s body? Gory Halooyah?’

‘The very same, Gus! Now, then, fall in, tallest on the right, shortest on the left – heels together, John, eyes front, Jemima, pull in your guts, Augustus, stop giggling, Alice – and I’ll teach you some capital verses you never heard before! Ready?’

I don’t suppose there’s a soul speaks English in the world who couldn’t sing the chorus today, but of course it hadn’t been written when we went down to Harper’s Ferry – J.B.’s army of ragamuffins, adventurers, escaped slaves, rustlers and lunatics. ‘God’s crusaders’, some enthusiast called us – but then again, I’ve read that we were ‘swaggering, swearing bullies and infidels’ (well, thank’ee, sir). We were twenty-one strong, fifteen white (one with pure terror, I can tell you), six black, and all set to conquer Dixie, if you please! We didn’t make it at the time, quite – but we did in the end, by God, didn’t we just, with Sherman’s bugles blowing thirty miles in latitude three hundred to the main …

Not that I gave a two-cent dam for that, you understand, and still don’t. They could have kept their idiotic Civil War for me, for (my own skin’s safety apart) it was the foulest, most useless conflict in history, the mass suicide of the flower of the British-American race – and for what? Black freedom, which would have come in a few years anyway, as sure as sunrise. And all those boys could have been sitting in the twilight, watching their Johns and Jemimas.

Still, I’ve got a soft spot for the old song – and for J.B., for that matter. Aye, that song which, the historian says, was sung by every Union regiment because ‘it dealt not with John Brown’s feeble sword, but with his soul.’ His soul, my eye – as often as not the poor old maniac wasn’t even mentioned, and it would be:

Wild Bill Sherman’s got a rope around his neck,

An’ we’ll all catch hold an’ give-it-one-hell-of-a-pull!

Glory, glory, hallelujah, etc …

Or it might be ‘our sergeant-major’, or Jeff Davis hanging from a sour apple tree, or any of the unprintable choruses that inspired the pious Mrs Howe to write ‘Mine eyes have seen the glory’.

But all that’s another story, for another day … in the meantime, I taught my small descendants some versions which were entirely to their liking, and we trooped up to the house, the infants in column of twos and the venerable patriarch hobbling painfully behind, flask at the high port, and all waking the echoes with:

John Brown’s donkey’s got an india-rubber tail,

An’ he rubbed it with camphorated oil!

followed by:

Our Great-grandpa saved the Viceroy

In the – good – old – Khyber – Pass!

and concluding with:

Flashy had an army of a hundred Bashi-bazouks

An’ the whole dam’ lot got shot!

Glory, glory, hallelujah …

Spirited stuff, and it was just sheer bad luck that the Bishop and other visiting Pecksniffs should already be taking tea with Elspeth and Miss Prentice when we rolled in through the french windows, the damp and dirty grandlings in full voice and myself measuring my ancient length across the threshold, flask and all. Very well, the grandlings were raucous and dishevelled, and I ain’t at my best sprawled supine on the carpet leaking brandy, but to judge from his lordship’s, disgusted aspect and Miss Prentice’s frozen pince-nez you’d have thought I’d been teaching them to smoke opium and sing ‘One-eyed Riley’.

The upshot was that the infants were packed off in disgrace to a defaulters’ tea of dry bread and milk, Gus was sent to bed early – oh, aye, Jemima ratted on him – and when the guests had departed in an odour of sanctity, withdrawing the hems of their garments from me and making commiserating murmurs to Elspeth, she loosed her wrath on me for an Evil Influence, corrupting young innocence with my barrack-room ribaldry, letting them get their feet wet, and did I know what shoes cost nowadays, and she was Black Affronted, and how was she ever going to look the Bishop in the face again, would I tell her?

Contrition not being my style, and useless anyway, I let the storm blow itself out, and later, having ensured that La Prentice was snug in her lair – polishing her knout and supping gin on the sly, I daresay – I raided the pantry and smuggled gingerbread and lemonade to the grandlings’ bedroom, where at their insistence I regaled them with the story of John Brown (suitably edited for tender ears). They fell asleep in the middle of it, and so did I, among the broken meats on John’s coverlet, and woke at last to the touch of soft lips on my aged brow to find Elspeth shaking her head in fond despair.

Well, the old girl knows I’m past reforming now, and that Jemima’s right: I’ll certainly go to the bad fire. I know one who won’t though, and that’s old Ossawatomie John Brown, ‘that new saint, than whom nothing purer or more brave was ever led by love of men into conflict and death’, and who made ‘the gallows glorious like the Cross’. That’s Ralph Waldo Emerson on J.B. ‘A saint, noble, brave, trusting in God’, ‘honest, truthful, conscientious’, comparable with William Wallace, Washington, and William Tell – those are the words of Parker and Garrison, who knew him, and they ain’t the half of his worshippers; talk about a mixture of Jesus, Apollo, Goliath and Julius Caesar! On the other hand … ‘a faker, shifty, crafty, vain, selfish, intolerant, brutal’, ‘an unscrupulous soldier of fortune, a horse-thief, a hypocrite’ who didn’t care about freeing slaves and would have been happy to use slave labour himself, a liar, a criminal, and a murderer – that’s his most recent biographer talking. Interesting chap, Brown, wouldn’t you say?

A good deal of it’s true, both sides, and you may take my word for it; scoundrel I may be, but I’ve no axe to grind about J.B.’s reputation. I helped to make it, though, by not shooting him in the back when I had the chance. Didn’t want to, and wouldn’t have had the nerve, anyway.

You might even say that I, all unwitting, launched him on the path to immortal glory. Aye, if there’s a company of saints up yonder, they’ll be dressing by the right on J.B., for when the Recording Angel has racked up all his crimes and lies and thefts and follies and deceits and cold-blooded killings, he’ll still be saved when better men are damned. Why? ’Cos if he wasn’t, there’d be such an almighty roar of indignation from the Heavenly Host it would bust the firmament; God would never live it down. That’s the beauty of a martyr’s crown, you see; it outshines everything, and they don’t come any brighter than old J.B.’s. I’m not saying he deserves it; I only know, perhaps better than anyone, how he came by it.

You will wonder, if you’re familiar with my inglorious record, how I came to take part with John Brown at all. Old Flashy, the bully and poltroon, cad and turncoat, lecher and toady – bearing Freedom’s banner aloft in the noblest cause of all, the liberation of the enslaved and downtrodden? Striking off the shackles at the risk of death and dishonour? Gad, I wish Arnold could have seen me. That’s the irony of it – if I’d bitten the dust at the Ferry, I’d have had a martyr’s crown, too, on top of all the honours and glory I’d already won in Her Majesty’s service (by turning tail and lying and posturing and pinching other chaps’ credit, but nobody knew that, not even wily old Colin Campbell who’d pinned the V.C. on my coat only a few months before). Oh, the Ferry fiasco could have been my finest hour, with the Queen in mourning, Yankee politicos declaiming three-hour tributes full of ten-dollar words and Latin misquotations (not Lincoln, though; he knew me too well), a memorial service in the Rugby chapel, the Haymarket brothels closed in respect, old comrades looking stern and noble … ‘Can’t believe he’s gone … dear old Flash … height of his fame … glorious career before him … goes off to free the niggers … not for gold or guerdon … aye, so like him … quixotic, chivalrous, helpin’ lame dogs … ah, one in ten thousand … I say, seen his widow, have you? Gad, look at ’em bounce! Rich as Croesus, too, they tell me …’

There’d have been no talk of roasted fags or expulsion for sottish behaviour, either. Die in a good cause and they’ll forgive you anything.

But I didn’t, thank God, and as any of you who have read my other memoirs will have guessed, I’d not have been within three thousand miles of Harper’s Ferry, or blasted Brown, but for the ghastliest series of mischances: three hellish coincidences – three, mark you! – that even Dickens wouldn’t have used for fear of being hooted at in the street. But they happened, with that damned Nemesis logic that has haunted me all my life, and landed me in more horrors than I can count. Mustn’t complain, though; I’m still here, cash in hand, the grandlings upstairs asleep, and Elspeth in her boudoir reading the Countess of Cardigan’s Recollections (in which, little does my dear one suspect, I appear under the name of ‘Baldwin’, and a wild night that was, but no mention, thank heaven, of the time I was locked in the frenzied embrace of Fanny Paget, Cardigan himself knocked on the door, I dived trouserless beneath the sofa, found a private detective already in situ, and had to lie beside the brute while Cardigan and Fanny galloped the night away two feet above our heads. Dammit, we were still there when her husband came home and blacked her eye. Serve her right; Cardigan, I ask you! Some women have no taste).

However, that’s a far cry from the Shenandoah, but before I tell you about J.B. I must make one thing clear, for my own credit and good name’s sake, and it’s this: I care not one tuppenny hoot about slavery, and never did. I can’t say it’s none of my biznai, because it was once: in my time, I’ve raided blacks from the Dahomey Coast, shipped ’em across the Middle Passage, driven them on a plantation – and run them to freedom on the Underground Railroad and across the Ohio ice-floes with a bullet in my rump, to say nothing of abetting J.B.’s lunatic scheme of establishing a black republic – in Virginia, of all places. Set up an Orange Lodge in the Vatican, why don’t you?

The point is that I was forced into all these things against my will – by gad, you could say I was ‘enslaved’ into them. For that matter, I’ve been a slave in earnest – at least, they put me up for sale in Madagascar, and ’twasn’t my fault nobody bid; Queen Ranavalona got me without paying a penny, and piling into that lust-maddened monster was slavery, if you like, with the prospect of being flayed alive if I failed to give satisfaction.

I’ve been a fag at Rugby, too.

So when I say I don’t mind about slavery, I mean I’m easy about the institution, so long as it don’t affect me; whenever it did, I was agin it. Selfish, callous, and immoral, says you, and I agree; unprincipled, too – unlike the Holy Joe abolitionist who used to beat his breast about his black brother while drawing his dividend from the mill that was killing his white sister – aye, and in such squalor as no Dixie planter would have tolerated for his slaves. (Don’t mistake me; I hold no rank in the Salvation Army, and I’ve never lifted a finger for our working poor except to flip ’em a tip, and employ them as necessary. I just know there’s more than one kind of slavery.)

Anyway, if life has taught me anything, it’s that the wealth and comfort of the fortunate few (who include our contented middle classes as well as the nobility) will always depend on the sweat and poverty of the unfortunate many, whether they’re toiling on plantations or licking labels in sweatshops at a penny a thousand. It’s the way of the world, and until Utopia comes, which it shows no sign of doing, thank God, I’ll just rub along with the few, minding my own business.

So you understand, I hope, that they could have kept every nigger in Dixie in bondage for all I cared – or freed them. I was indifferent, spiritually, and only wish I could have been so, corporally. And before you start thundering at me from your pulpit, just remember the chap who said that if the union of the United States could only be preserved by maintaining slavery, that was all right with him. What’s his name again? Ah, yes – Abraham Lincoln.

And now for old John Brown and the Path to Glory, not the worst of my many adventures, but just about the unlikeliest. It had no right to happen, truly, or so it strikes me when I look back. God knows I haven’t led a tranquil life, but in review there seems to have been some form and order to it – Afghanistan, Borneo, Madagascar, Punjab, Germany, Slave Coast and Mississippi, Russia and the back o’ beyond, India in the Mutiny, China, American war, Mexico … and there, you see, I’ve missed out J.B. altogether, because he don’t fit the pattern, somehow. He’s there, though, whiskers, six-guns, texts, and all, between India and China – and nought to do with either, right out o’ the mainstream, as though some malevolent djinn had plucked me from my course, dipped me into Harper’s Ferry, and then whisked me back to the Army again.

It began (it usually does) with a wanton nymph in Calcutta at the back-end of ’58. But for her, it would never have happened. Plunkett, her name was, the sporty young wife of an elderly pantaloon who was a High Court judge or something of that order. I was homeward bound from the Mutiny, into which I’d been thrust by the evil offices of my Lord Palmerston, who’d despatched me to India on secret work two years before;

thanks to dear old Pam, I’d been through the thick of that hellish rebellion, from the Meerut massacre to the battle of Gwalior, fleeing for my life from Thugs and pandies, spending months as a sowar of native cavalry, blazing away at the Cawnpore barricade, sneaking disguised out of Lucknow with a demented Irishman in tow, and coming within an ace of being eaten by crocodiles, torn asunder on the rack, and blown from a gun as a condemned mutineer – oh, aye, the diplomatic’s the life for a lad of metal, I can tell you. True, there had been compensations in the delectable shape of Lakshmibai, Rani of Jhansi, and a Victoria Cross and knighthood at the end of the day, and the only fly in the ointment as I rolled down to Calcutta had been the discovery that during my absence from England some scribbling swine had published his reminiscences of Rugby School, with me as the villain of the piece. A vile volume entitled Tom Brown’s Schooldays, on every page of which the disgusting Flashy was to be found torturing fags, shirking, toadying, lying, whining for mercy, and boozing himself to disgraceful expulsion – every word of it true, and all the worse for that.

It was with relief that I learned, by eavesdropping in Calcutta’s messes and hotels, that no one seemed to have heard of the damned book, or weren’t letting on if they had. It’s been the same ever since, I’m happy to say; not a word of reproach or a covert snigger, even, although the thing must have been read in every corner of the civilised world by now. Why, when President Grant discovered that I was the Flashman of Tom Brown he just looked baffled and had another drink.

The fact is, some truths don’t matter. I’ve been seventy years an admired hero, the Hector of Afghanistan, the chap who led the Light Brigade, daredevil survivor of countless stricken fields, honoured by Queen and Country, V.C. and Medal of Honour – folk simply don’t want to know that such a paladin was a rotter and bully in childhood, and if he was, they don’t care. They put it from their minds, never suspecting that boy and man are one, and that all my fame and glory has been earned by accident, false pretence, cowardice, doing the dirty, and blind luck. Only I know that. So my shining reputation’s safe, which is how the public want it, bless ’em.

It’s always been the same. Suppose some learned scholar were to discover a Fifth Gospel which proved beyond doubt that Our Lord survived the Cross and became a bandit or a slave-trader, or a politician, even – d’you think it would disturb the Christian faith one little bit? Of course not; ’twouldn’t even be denied, likely, just ignored. Hang it, I’ve seen the evidence, in black and white in our secret files, that Benjamin Franklin was a British spy right through the American Revolution, selling out the patriots for all he was worth – but would any Yankee believe that, if ’twas published? Never, because it’s not what they want to believe.

I reached Calcutta, then, to find myself feted on all sides – and there was no shortage of heroes to be worshipped after the Mutiny, you may be sure. But no other had the V.C. and a knighthood (for word of the latter had leaked out, thanks to Billy Russell, I daresay), or stood six feet two with black whiskers and Handsome Harry’s style. I’d had my fill of fame in the past, of course, and was all for it, but I knew how to carry it off, modest and manly, not too bluff, and with a pinch of salt.

I’d supposed it would be straight aboard and hey for Merry England, but I was wrong. P. and O. hadn’t a berth for months, for the furloughs had started, and every civilian in India seemed to be leaving for home, to say nothing of ten thousand troops to be shipped out; John Company was hauling down his flag at last, India was passing under the rule of the Crown, everything was topsy-turvy, and even heroes had to wait their turn for a passage to Suez and the overland route – at a pinch you could get a ship to the Cape, but that was a deuce of a long haul. So I made myself pleasant around the P. and O. office, squeezed the buttocks of a Bengali charmer who wrote letters for the head clerk and had her dainty hands on his booking lists, tempted her with costly trinkets, and sealed the bargain by rattling her across his desk while he was out at tiffin (‘Oh, sair, you are ay naughtee mann!’). And, lo, ben Flashy’s name led all the rest on a vessel sailing two weeks hence.

I was dripping with blunt, having disposed of my Lucknow loot and banked the proceeds, but there wasn’t a bed to be had at the Auckland. Outram pressed me to stay with him – nothing too good for the man who’d smuggled his message through the pandy lines to Campbell – but I shied; only the fast set stayed up after ten in ‘Cal’ in those days, and I guessed that chez Outram it would be prayers at nine and gunfire and a cold tub at six, and I didn’t fancy above half scrambling out in the dark to seek vicious diversion. I played it modest, saying I knew his place would be full of Army and wives, and I’d rather keep out o’ the way, don’t you know, sir, and he looked noble and patted my shoulder, saying he understood, my boy, but I’d dine at least?

I put up at Spence’s, a ‘furnished apartment’ shop with a table d’hôte but no bearers even to clean your room, so bring your own servant or live like a pig. It served, though, and I could haunt the Auckland of an evening, seeking what I might devour.

I’d been two years without Elspeth, you see, and while they hadn’t been celibate quite, what with Lakshmi and various dusky houris here and there, and only the buxom Mrs Leslie at Meerut by way of variety, I was beginning to itch for something English again, blonde and milky for preference, and not reeking of musk and garlic. So the moment I saw Lady Plunkett (for her husband had a title) on the Auckland verandah, I knew I’d struck gold, which was the colour of her hair, with complexion to match. Beside Elspeth you’d not have noticed her, but she was tall and plump enough, with a pudding face and a big mouth, drooping with boredom, and once I’d caught her eye it was plain sailing. Believe it or not as you like, she dropped her handkerchief by my chair as she sailed out of the dining-room that evening (a thing I thought they did only in comic skits on the halls), so I told a bearer to take it after the mem-sahib, satisfied myself that her husband was improving his gout with port in company with other dodderers, and sauntered up to her rooms on the first floor.

To cut a long story short, we got along splendidly, and I had slipped her gown to her hips and was warming her up, so to speak, when the door opened at my back, her eager whimpers ended in a terrified squeak, and I glanced round to see her lord and master, who shouldn’t have been up for hours, tottering across the threshold, apparently on the verge of apoplexy. Well, I’d been there before, but seldom in more fortunate circumstances, for I was still fully clad, we were both standing up, and she was half-hidden from his gooseberry gaze. I hastily surrendered her tits, and glared at him.

‘What the devil d’ye mean by this intrusion, sir?’ cries I. ‘Begone this instant!’ And to my paralysed beauty I continued: ‘There is only the slightest congestion, marm, I’m happy to say; nothing to occasion alarm. You may resume your clothing now. I shall have a prescription sent round directly … Sir, did you not hear me? How dare you interrupt my examination? Upon my word, sir, have you no delicacy – out, I say, at once!’

He could only gobble in purple outrage while I chivvied her behind a screen. ‘That’s my wife!’ he bawls.

‘Then you should take better care of her,’ says I, whipping out a dhobi-list and scribbling professionally. ‘Fortunately my room is close at hand, and when I was summoned your lady was suffering an acute palpitation. Not uncommon – close city climate – nothing serious, but unpleasant enough … h’m, three grains should do it, I think … Has she had these fits before?’

‘I … I don’t know!’ cries he, wattling. ‘What? What? Maud, what does this mean? Who – why – are you a doctor, sir?’

‘MacNab, surgeon, 92nd,’ says I, mighty brisk, ignoring the mewlings from behind the screen and his own choking noises. ‘Complete rest for a day or two, you understand; no undue exertion. I shall send this note to the apothecary.’ I pocketed my paper, and sniffed, looking stern. ‘Port, sir? Well, it’s no concern of mine if you choose to drink yourself under ground, but I’d say one invalid in the family is enough, hey?’ I addressed the screen. ‘To bed at once, marm! Two teaspoonfuls when the boy brings the medicine, mind. I shall call in the morning and look to find you much improved. Good night – and to you, sir.’

Never let ’em get a word in, you see. I was out and downstairs before he knew it, reflecting virtuously that that was another marriage I’d saved by quick thinking – if he believed her, which I’d not have done myself. But, stay … even if he did, he’d find out soon enough that there was no Dr MacNab of the 92nd, and start baying for the blood of the strapping chap with black whiskers, and Calcutta society being as small as it was, he was sure to run me down – and then, scandal, which would certainly tarnish my newly won laurels … my God, if Plunkett roared loud enough it might even reach the Queen’s ears, and where would my promised knighthood be then? But if I could slide out now, undetected – well, you can’t identify a man who ain’t there, can you?

All of a sudden, Westward ho! without delay seemed the ticket – and scandal wasn’t the only reason. Some of these ancients with young high-stepping consorts can be vicious bastards, as witness the old roué who’d sicked his bullies after me for romping Letty Lade in the cricket season of ’45 – and he hadn’t even been married to her.

So now you see Flashy at the Howrah docks in the misty morning, with his dunnage on a hand-cart, dickering for a passage to the Cape with a Down-east skinflint in a tile hat who should have been flying the Jolly Roger, the price he demanded for putting into Table Bay. But he was sailing that day, and since tea for New York was his cargo it would be a fast run, so I stumped up with a fair grace; after all, I hadn’t put cash down for the passage arranged by the Bengali bint, and I didn’t grudge her the trinkets; my one regret was that I hadn’t boarded the Plunkett wench … I hope he believed her.

It was about a month to the Cape, with the taffrail under most of the way, but not too bad until we neared Algoa Bay, when it began to blow fit to sicken Magellan. I’ve never seen so much green water; even less cheering was the sight of a big steamer lying wrecked on a reef off Port Elizabeth,

and I was a happy man when we’d rounded the Cape and opened up that glorious prospect which is one of the wonders of the seas – the great bay glittering in the sunlight with a score or more of windjammers and coasters and a few steamers at anchor, and beyond them the ‘table-cloth’ of cloud rolling down the flank of the Mountain to Signal Hill, and guns booming from the Castle to salute a man-of-war putting out, with crowds fluttering hats and scarves from Green Point.

Once ashore I engaged a berth on the Union mail steamer sailing the following week, put up at the Masonic, and took a slant at the town. It was busy enough, for the Australian gold rush of a few years back, and the Mutiny, had set the port booming, but the town itself was a damned Dutch-looking place with its stoeps and stolid stucco houses, most of which are gone now, I believe, and the great church clock tower which looks as though it should have an Oom Paul beard round its face. It had been a wild place in the earlies, the ‘tavern of the seas’, but now it was respectable and dull, and the high jinks were to be had at Grahamstown, far away up the coast, where the more sensible Britons lived and the Army was quartered – what there was of them, for the Governor, George Grey, had stripped the colony of men, guns, and stores for the Mutiny, and the old Africa hands in the hotel were full of foreboding over their pipes and stingo, with the country arse-naked, as one of them put it, and the usual trouble brewing to the north.

‘We’ll have the Kaffirs at our throats again ere long, see if we don’t,’ says one pessimist. ‘Know how many wars they’ve given us, colonel, thanks to the damned missionaries? Eight – or is it nine? Blessed if you don’t lose count! To say nothin’ o’ the Dutch – not that they haven’t got their hands full, by all accounts, an’ serve the miserable beggars right! They’ll be howlin’ for you redcoats presently, mark my words!’

‘You never saw a Boer ask help from a Briton yet!’ scoffs another. ‘Nor they needn’t – they’ll give the Basutos the same pepper they gave John Zulu, if Moshesh don’t mind his manners.’

‘You never know,’ laughs a third, ‘maybe the dear Basutos’ll do the decent thing an’ starve themselves to death, what?’

‘Not old Moshesh – that’s a Bantu who’s too smart by half, as we’ll find out to our cost one o’ these days.’

‘Oh, Grey’ll see to him, never fear – an’ the Boers, if only London will let him alone. Any more word of his goin’?’

‘You may bet on it – if the Colonial Office don’t ship him home, the doctor will. I don’t like his colour; the man’s played out.’

‘Well, he can go for me. We bade good riddance to Brother Boer years ago – why should we want him back?’

These are just scraps of talk that I remember, and no doubt they’re as Greek to you as they were to me, but being a curious child I listened, and learned a little, for these fellows – English civilians and merchants mostly, a Cape Rifleman or two, and a couple of trader-hunters down from the frontiers – knew their country, which was a closed book to me, then, bar my brief visit to the Slave Coast, and that was years ago and a world away from the Cape. Truth to tell, Africa’s never been my patch, much; I’ve soldiered on veldt and desert, and seen more of its jungle than I cared for, but like our statesmen I’ve always thought it a dam’ nuisance. Perhaps Dahomey inoculated me against the African bug which has bitten so many, to their cost, for it breeds grand dreams which often as not turn into nightmares.

It was biting hard at this time, not least on Grey, the Governor, and since he was to play a small but crucial part in my present story, I must tell you something of him – but I can’t do that without first telling you about South Africa, as briefly as may be. It won’t explain the place to you (God Himself couldn’t do that), but it may lead you to wonder if two damned dirty and costly wars mightn’t have been avoided (and who knows what hellish work in the future?) if only those Reform Club buffoons hadn’t thought they knew better than the man on the spot.

You have to understand that in ’59 Africa was the last great prize and mystery, an unmapped hinterland twice the size of Europe where anything was possible: lost civilisations, hidden cities, strange white tribes – they were no joke then. Real exploration of the dark heart of the continent had just begun; Livingstone had blazed his trails up and down it and across, farther north Dick Burton was making an ass of himself by not finding the source of the Nile, but the broad steady inroad was from the south, where we’d established ourselves. The Dutch settlers, not caring for us much, had trekked north to found their own Boer republics in lands where they met hordes of persevering black gentlemen coming t’other way; they fought the Zulus and Basutos (and each other) while we fought the Kaffirs to the east, and everything was dam’ confused, chiefly because our rulers at home couldn’t make up their minds, annexing territories and then letting ’em go, interfering with the Boers one minute and recognising their independence the next, trying to hold the ring between black and white and whining at the expense, and then sending out Grey, who brought the first touch of common sense – and, if you ask me, the last.

His great gift, I was told, was that he got on splendidly with savages – even the Boers. He’d been a soldier, explored in Australia, governed there and in New Zealand, and saw at once that the only hope for southern Africa was to reunite Briton and Boer and civilise the blacks within our borders, which he’d begun to do with schools and hospitals and teaching them trades. In this he’d been helped by one of those lunatic starts which happen among primitive folk: in ’57 a troublesome warrior tribe, the ’Zozas, had got the notion that if they destroyed all their crops and cattle, the gods would send them bumper harvests and even fatter herds, and all the white men in Africa would obligingly drown themselves; accordingly, the demented blighters starved themselves to death, which left more space for white settlement, and the surviving ’Zozas were in a fit state to be civilised.

Meanwhile Grey was using his persuasive arts to charm the Boers back under the Union Jack, and since our Dutch friends were beginning to feel the pinch of independence – isolated up yonder, cut off from the sea, worn out with their own internal feuding, and fighting a running war against the Basutos (whose wily chief, Moshesh, had egged on the ’Zozas’s suicide for his own ends) – they were only too ready to return to Britannia’s fold.

That was the stuff of Grey’s dream, as I gathered from my fellow-guests at the hotel – a united South Africa of Briton, Boer, and black. Most of my informants were all for it, but one or two were dead against the Boers, which put one grizzled old hunter out of all patience.

‘I don’t like the Hollanders any better’n you do,’ says he, ‘but if whites won’t stand together, they’ll fall separately. Besides, if we don’t have the Boers under our wing, they’ll go on practisin’ their creed that the only good Bantu’s a dead one – or a slave, an’ we know where that leads – bloody strife till Kingdom Come.’

‘And what’s Grey’s style?’ asks a fat civilian. ‘Teach ’em ploughing and the Lord’s Prayer and make ’em wear trowsers? Try that with the Matabele, why don’t you? Or the Zulu, or the Masai.’

‘You’ve never seen the Masai!’ snaps the old chap. ‘Anyway, sufficient unto the day. I’m talkin’ about settlin’ the Bantu inside our own borders –’

‘We should never ha’ given ’em the vote,’ says a Cape Rifleman. ‘What happens when they outnumber us, tell me that?’ This was an eye-opener to me, I can tell you, but it’s true – every man-jack born on Cape soil had the vote then, whatever his colour; more than could be said for Old England.

‘Oh, by then all the Zulu and Mashona will be in tight collars, talking political economy,’ sneers the fat chap. He jabbed his pipe at the hunter. ‘You know it’s humbug! They ain’t like us, they don’t like us, and they’ll pay us out when they can. Hang it all, you were at Blood River, weren’t you? Well, then!’

‘Aye, an’ I back Grey ’cos I don’t want Blood River o’er again!’ cries the hunter. ‘An’ that’s what you’ll get, my boy, if the Boers ain’t reined up tight inside our laager! As for the tribes … look here, I don’t say you can civilise a Masai Elmoran now … but they’re a long way off. Given time, an’ peaceful persuasion when we come to ’em – oh, backed up by a few field pieces, if you like – things can be settled with good will. So I reckon Grey’s way is worth a try. It’s that or fight ’em to the death – an’ there’s a hell of a lot o’ black men in Africa.’

There were murmurs of agreement, but my sympathies were all with the fat chap. I don’t trust enlightened proconsuls, I’d heard no good of the Boers, and fresh from India as I was, the notion of voting niggers was too rich for me. Can’t say my views have changed, either – still, when I look back on the bloody turmoil of southern Africa in my lifetime, which has left Boer and Briton more at loggerheads than ever, the blacks hating us both, and their precious Union fifty years too late, I reckon the old hunter was right: Grey’s scheme was worth a try; God knows it couldn’t have made things worse.

But of course it never got a try, because the home government had the conniptions at the thought of another vast territory being added to the Empire, which they figured was too big already – odd, ain’t it, that the world should be one-fifth British today, when back in the ’fifties our statesmen were dead set against expansion – Palmerston, Derby, Carnarvon, Gladstone, aye, even D’Israeli, who called South Africa a millstone.

While I was at the Cape, though, the ball was still in the air; they hadn’t yet scotched Grey’s scheme of union and called him home, and he was fighting tooth and nail to get his way. Which was why, believe it or not, I found myself bidden to dine with his excellency a few days later – and that led to the first coincidence that set me on the road to Harper’s Ferry.

When I got the summons, aha, thinks I, he wants to trot the Mutiny hero up and down before Cape society, to raise their spirits and remind ’em how well the Army’s been doing lately. Sure enough, he had invited the local quality to meet me at a reception after dinner, but that wasn’t his reason, just his excuse.

We dined at the Castle, which had been the Governor’s residence in the days of the old Dutch East India Company, and was still used occasionally for social assemblies, since it had a fine hall overlooked at one end by a curious balcony called the Kat, from which I gather his Dutch excellency had been wont to address the burghers. I duly admired it before we went to dinner in an ante-room; it was a small party at table, Flashy in full Lancer fig with V.C. and assorted tinware, two young aides pop-eyed with worship, and Grey himself. He was a slim, poetic-looking chap with saintly eyes, not yet fifty, and might have been a muff if you hadn’t known that he’d walked over half Australia, dying of thirst most of the time, and his slight limp was a legacy of an Aborigine’s spear in his leg. The first thing that struck you was that he was far from well: the skin of his handsome face was tight and pallid, and you felt sometimes that he was straining to keep hold, and be pleasant and easy. The second thing, which came out later, was his cocksure confidence in G. Grey; I’ve seldom known the like – and I’ve been in a room with Wellington and Macaulay together, remember.

He was quiet enough at dinner, though, being content to watch me thoughtful-like while his aides pumped me about my Mutiny exploits, which I treated pretty offhand, for if I’m to be bongered

let it be by seniors or adoring females. I found Grey’s silent scrutiny unsettling, too, and tried to turn the talk to home topics, but the lads didn’t care for the great crusade against smoking, or the state of the Thames, or the Jews in Parliament;

they wanted the blood of Cawnpore and the thunder of Lucknow, and it was a relief when Grey sent them packing, and suggested we take our cigars on the verandah.

‘Forgive my young men,’ says he. ‘They see few heroes at the Cape.’ The sort of remark that is a sniff as often as not, but his wasn’t; he went on to speak in complimentary terms of my Indian service, about which he seemed to know a great deal, and then led the way down into the garden, walking slowly along in the twilight, breathing in the air with deep content, saying even New Zealand had nothing to touch it, and had I ever known anything to compare? Well, it was balmy enough with the scent of some blossom or other, and just the spot to stroll with one of the crinolines I could see driving in under the belfry arch and descending at the Castle doorway beyond the trees, but it was evidently heady incense to Grey, for he suddenly launched into the most infernal prose about Africa, and how he was just the chap to set it in order.

You may guess the gist of it from what I’ve told you already, and you know what these lyrical buggers are like when they get on their hobby-horses, on and on like the never-wearied rook. He didn’t so much talk as preach, with the quiet intensity of your true fanatic, and what with the wine at dinner and the languorous warmth of the garden, it’s as well there wasn’t a hammock handy. But he was the Governor, and had just fed me, so I nodded attentively and said ‘I never knew that, sir,’ and ‘Ye don’t say!’, though I might as well have hollered ‘Whelks for sale!’ for all he heard. It was the most fearful missionary dross, too, about the brotherhood of the races, and how a mighty empire must be built in harmony, for there was no other way, save to chaos, and now the golden key was in his hand, ready to be turned.

‘You’ve heard that the Orange Volksraad has voted for union with us?’ says he, taking me unawares, for until then he’d apparently been talking to the nearest tree. Not knowing what the Orange Volksraad was, I cried yes, and not before time, and he said this was the moment, and brooded a bit, à la Byron, stern but gleaming, before turning on me and demanding:

‘How well do you know Lord Palmerston?’

Too dam’ well, was the answer to that, but I said I’d met him twice in the line of duty, no more.

‘He sent you to India on secret political work,’ says he, and now he was all business, no visionary nonsense. ‘He must think highly of you – and so he should. Afghanistan, Punjab, Central Asia, Jhansi … oh, yes, Flashman, news travels, and we diplomatics take more note of work in the intelligence line than we do of …’ He indicated my Cross, with a little smile. ‘I have no doubt that his lordship values your opinion more than that of many general officers. Much more.’ He was looking keen, and my innards froze, for I’d heard this kind of talk before. You ain’t getting me up yonder disguised as a Zulu, you bastard, thinks I, but his next words quieted my fears.

‘I am not persona grata at home, colonel. To be blunt, they think me a dangerous dreamer, and there is talk of my recall – you’ve heard it bruited in the town, I don’t doubt. Well, sir,’ and he raised his chin, eye to eye, ‘I hope I have convinced you that I must not be recalled, for the sake of our country’s service – and for the sake of Africa. Now, Lord Palmerston will not be out of office long, I believe.

Will you do me the signal favour, when you reach home, of seeking him out and impressing on him the necessity – the imperative necessity – of my remaining here to do the work that only I can do?’

I’ve had some astonishing requests in my time – from women, mostly – but this beat all. If he thought the unsought opinion of a lowly cavalry colonel, however supposedly heroic and versed in political ruffianing, would weigh a jot with Pam, he was in the wrong street altogether. Why, the thought of my buttonholing that paint-whiskered old fox with ‘Hold on, my lord, while I set you right about Africa’ was stuff for Punch. I said so, politely, and he fixed me with that steely gazelle eye and sighed.

‘I am well aware that a word from you may carry little weight – all I ask is that … little. His lordship has not inclined to accept my advice in the past, and I must use every means to persuade him now, do you not see?’ He stared hard at me, impatient; there was a bead of sweat on his brow – and suddenly it came to me that the man was desperate, ready to snatch at anything, even me. He was furious at having to plead with a mutton-headed soldier (he, Sir George Grey, who alone could save Africa!), but he was in that state where he’d have tried to come round Palmerston’s cook. He tried to smile, but it was a wry grimace on the pale, strained face. ‘Decisions, you know, are not always swayed by senators; a word from the slave in the conqueror’s chariot may turn the scale.’ Gad, he could pay a compliment, though. ‘Well, Colonel Flashman, may I count on you? Believe me, you will be doing a service to your country quite as great as any you may have done in the past.’

I should have spat in his eye and told him I didn’t run errands for civil servants, but it’s not every day you’re toadied by a lofty proconsul, patronising jackanapes though he may be. So I accepted his hand-clasp, which was hard (but damp, I noted with amusement), marvelling at the spectacle of a proud man humbling himself for the sake of his pride, and ambition. All wasted, too, for they did recall him – and then Pam reinstated him, not at my prompting, you may be sure. But his great African dream came to nothing.

That’s by the way, and if I’ve told you of Grey and Africa at some length, well, I’m bound to record these things, and it was a queer start altogether, and he was an odd bird – but the point is that if he hadn’t thought he could use me, he’d never have dined me that night, or shown me off to Cape society … and I’d never have heard of Harper’s Ferry.

The last carriages had arrived while we talked, so now it was Flashy on parade in the hall before society assembled. Grey made me known from the Kat balcony, to polite applause, and led me down the little staircase to be admired and gushed over; there must have been thirty or forty under the chandeliers, and Grey steered me among them; I gave my bluff manly smile, with a click of the heels or an elegant inclination, depending on their sex, but when we came to a group by the piano, I thought, hollo, this is far enough.

She was seated at the keyboard, playing the last bars of a waltz, tra-la-ing gaily and swaying her shoulders to the music; they were the colour of old ivory, flaunting themselves from a silvery-white dress which clung to her top hamper in desperation. She laughed as she struck the final flourish, and as those nearest patted their palms she bowed and turned swiftly on the stool, smiling boldly up at me and extending a slim gloved hand as though she had timed the action precisely to Grey’s introduction. I didn’t hear the name, being intent on taking stock: bright black eyes alight with mischief, that dark cream complexion (touch o’ the tar brush, I fancied), glossy black hair that swung behind her in a great fan – a shade too wide in the mouth for true beauty, and with heavy brows that almost met above a slim aquiline nose, but she was young and gay and full of sauce, and in that pale, staid assembly she was as exotic as an orchid in a bed of lettuce, with a shape to rival Montez as she sat erect, sweeping her skirt clear of the piano stool.

‘Oah, I should have played a march in your honour, Sir Harree – nott a waltz!’ cries she. Chi-chi, beyond doubt, with that shrill lilt to her voice, and mighty pert for a colonial miss. I said gallantly ’twas all one, since in her presence I was bound to look, not listen – and I knew from the way she fluttered her lids, smiling, and then raised them, wide and insolent, that we were two of a mind. Her hand tightened, too, when I pressed it, nor did she withdraw it as Grey made another introduction, and I saw she was glancing with amusement at the chap who’d been turning her music, whom I hadn’t noticed. ‘My father,’ says she, and as I faced him I realised with an icy shock where I’d seen her dark brows and arched nose before, for I was staring into the pale terrible eyes of John Charity Spring.

It’s a shame those books on etiquette don’t have a chapter to cover encounters with murderous lunatics whom you’d hoped never to meet again. I could have used one then, and if you’ve met J. C. Spring, M.A., in my memoirs, you’ll know why. This was the mad villain who’d kidnapped me to the Slave Coast on his hell-ship in ’48 (on my own father-in-law’s orders, too), and perforce I’d run black ivory with him, and fled from she-devil Amazons, and been hunted the length of the Mississippi, and lied truth out of Louisiana to keep both our necks out of a noose.

The last time I’d seen him he’d been face down in a bowl of trifle in a New Orleans brothel, drugged senseless so that he could be hauled away and shanghaied – to Cape Town, bigod! Had he been here ever since – how long was it? Ten years almost, and here he was, brooding malevolently at me from those soulless eyes, while I gaped dumbstruck. The trim beard and hair were white now, but he was as burly as ever, the same homicidal pirate whom I’d loathed and dreaded; the weal on his forehead, which darkened whenever he was preparing to spill blood or talk about Oriel College, was glowing pink, and he spoke in the old familiar growl.

‘Colonel and sir, now, eh? You’ve risen in rank since I saw you last – and in distinction, too, it seems.’ He glowered at my medals. ‘Bravely earned, I daresay. Ha!’

Grey wasn’t a diplomat for nothing. ‘You are acquainted?’ says he, and Spring bared his fangs in his notion of a smile.

‘Old shipmates, sir!’ barks he, glaring as though I were a focsle rat. ‘Reunited after many years, eh, Flashman? Aye, gratis superveniet quae non sperabitur hora!’

He wheeled on his daughter – Spring with a daughter, my God! – and I dropped her hand like a hot rivet. ‘My dear, will you not play your new Scarlatti piece for his excellency, while the Colonel and I renew old acquaintance – charming, sir, I assure you! Such delicacy of touch!’ And in an aside to me: ‘Outside, you!’

He had my arm in a grip like a steel trap, and I knew better than to argue. Maniacs like Spring don’t stand on ceremony for mere governors – four quick strides and he had me on the verandah, and as he almost threw me down the steps to the shadowy garden my one thought was that he was going to set about me in one of his berserk rages – I could guess why, too, so I wrenched clear, babbling.

‘I’d nothing to do with your being shanghaied! It was Susie Willinck – I didn’t even know she was going to –’

‘Shut your gob!’ Oriel manners still, I could see. He shoved me against a tree and planted himself four-square, hands thrust into pockets, quarter-deck style. ‘You needn’t protest innocence to me! You’d never have the spine to slip me a queer draught – aye, but you’d sit by and see it done, you mangy tyke! Well, nulla pallescere culpa,