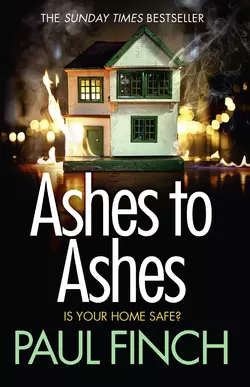

Ashes to Ashes: An unputdownable thriller from the Sunday Times bestseller

Paul Finch

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 288.34 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 25.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: The Sunday Times bestseller returns with his next unforgettable crime thriller. Fans of MJ Arlidge and Stuart MacBride won’t be able to put this down.John Sagan is a forgettable man. You could pass him in the street and not realise he’s there. But then, that’s why he’s so dangerous.A torturer for hire, Sagan has terrorised – and mutilated – countless victims. And now he’s on the move. DS Mark ‘Heck’ Heckenburg must chase the trail, even when it leads him to his hometown of Bradburn – a place he never thought he’d set foot in again.But Sagan isn’t the only problem. Bradburn is being terrorised by a lone killer who burns his victims to death. And with the victims chosen at random, no-one knows who will be next. Least of all Heck…