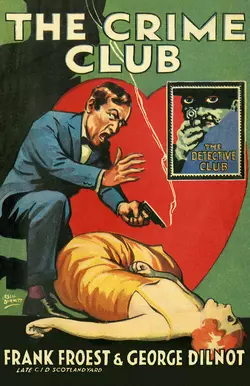

The Crime Club

Frank Froest

George Dilnot

David Brawn

The Detective Story Club’s first short story anthology is based around a London detective club and includes three newly discovered tales unpublished for 100 years, plus a story bearing an uncanny resemblance to a Conan Doyle Sherlock Holmes story but written some seven years earlier.‘You will seek in vain in any book of reference for the name of The Crime Club. Its watchword is secrecy. Its members wear the mask of mystery, but they form the most powerful organisation against master criminals ever known. The Crime Club is an international club composed of men, but they spend their lives studying crime and criminals. In its headquarters are to be found men from Scotland Yard and many foreign detectives and secret service agents. This book tells of their greatest victories over crime and is written, in association with George Dilnot, by a former member of the criminal investigation department of Scotland Yard.’With its highly evocative title, The Crime Club was the first collection of short stories published by the Detective Story Club. Co-authored by CID Superintendent Frank Froëst and police historian George Dilnot, these entertaining mysteries left readers guessing how many were based on true cases.This Detective Story Club classic is introduced by David Brawn, who looks at how the The Crime Club inspired a turning point in British book publishing, and includes three newly discovered stories by Froëst and Dilnot.

Copyright (#u25cd526d-d141-549d-9dbe-989ba0fe2bdb)

Published by COLLINS CRIME CLUB

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street,

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by Eveleigh Nash 1915

Published by The Detective Story Club for Wm Collins Sons & Co. Ltd 1929

Introduction © David Brawn 2016

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1929, 2016

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008137335

Ebook Edition © June 2016 ISBN: 9780008137342

Version: 2016-04-28

Table of Contents

Cover (#ub8d4900a-1af4-580c-831f-bcd409a7a68a)

Title Page (#u001fb172-ef5d-53aa-922b-35d666989d1a)

Copyright (#u0d43507c-5454-5a5c-8ee0-6c10812b5c23)

Introduction (#u491326ab-378a-5c07-94f3-a67b80526b4e)

Chapter I: The Crime Club (#u2903c44b-b51b-5ca9-a33e-232a433583e3)

Chapter II: The Red-Haired Pickpocket (#u4bde2fa6-8d9c-5b08-8821-49daac057687)

Chapter III: The Man With the Pale-Blue Eyes (#u37c6c323-cada-5eb3-9e8f-774ec3ad39fe)

Chapter IV: The Maker of Diamonds (#u33213391-1809-554a-9498-d09fe8f9d7ef)

Chapter V: Creeping Jimmie (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter VI: The Mayor’s Daughter (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter VII: A Meeting of Greeks (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter VIII: The Seven of Hearts (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter IX: The Goat (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter X: Pink-Edged Notepaper (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XI: The String of Pearls (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XII: The ‘Con’ Man (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XIII: Crossed Trails (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XIV: The Dagger (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XV: Found—a Pearl (#litres_trial_promo)

The Crime Club (#litres_trial_promo)

The Detective Story Club (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

INTRODUCTION (#u25cd526d-d141-549d-9dbe-989ba0fe2bdb)

WHEN The Crime Club was first published by Eveleigh Nash in 1915, little did the authors—both of them ex-policemen—know that the book’s title would become synonymous with detective publishing for the next 100 years.

Frank Froëst had risen through the ranks of the Metropolitan Police, attaining the position of Superintendent of the CID in 1906. He had become famous for his involvement in a number of high-profile international incidents, including the mass arrest in South Africa of more than 400 of the Jameson Raiders in 1896—the biggest mass arrest in British history—and for bringing high-profile villains such as society jewel-thief ‘Harry the Valet’ and the notorious Dr Crippen to justice. (More of Froëst’s exploits are discussed in Tony Medawar’s introduction to The Grell Mystery, also in this series.) Froëst retired in 1912, moving to Somerset where he joined the County Council and became a magistrate. Putting his 33-year experience in the police service to good use, he also turned to writing, and his detective novel The Grell Mystery (1913) proved popular with readers, who felt that its author was giving them an authentic insight into the detail of real police work—a genre that would become referred to as the ‘police procedural’.

Speculation that Froëst had help from a professional writer to produce a debut novel as fine as The Grell Mystery is given some credence by his sharing the byline on his two subsequent books with writer George Dilnot. Turning to journalism after six years in the army and subsequent service in the police, Dilnot’s first major book, Scotland Yard: The Methods and Organisation of the Metropolitan Police (1915), owed a great deal for its detailed content to the recently retired Froëst. The book was one of the earliest attempts to make public the inside workings of ‘the finest police force in the world’, which at that time employed 20,000, and must have been an invaluable resource for early detective writers. Froëst himself is name-checked numerous times, and comes across as the epitome of determination, organisation and innovation.

Whether or not Dilnot did ghost-write The Grell Mystery as a favour to his former boss, by the time Froëst’s other detective novel was published, The Rogues’ Syndicate (1916), they were sharing equal billing. First serialised in the US as The Maelstrom in the magazine All-Story Weekly over six weeks in March and April 1916, the book marked the end of Froëst’s short writing career, although his name lived on in reprints and in silent movies of both The Grell Mystery and The Rogues’ Syndicate in 1917, the latter film retaining its magazine title of The Maelstrom.

In between the two novels came The Crime Club, a collection of eleven detective stories (plus a prefatory chapter) that had originally appeared in the monthly The Red Book Magazine between December 1914 and November 1915. The stories were linked by the conceit of a secret London club located off the Strand where international crime fighters would go to help solve and also share tales of their most outlandish cases. Although the idea of a fictional detectives’ club was not entirely new, previous instances—for example Carolyn Wells’ five stories about the International Society of Infallible Detectives, starting with ‘The Adventure of the Mona Lisa’ in January 1912—brought together pastiches of well-known sleuths such as Sherlock Holmes and Arsène Lupin, whereas The Crime Club featured all-new creations, with the exception of Froëst’s own Heldon Foyle from The Grell Mystery, who appeared in ‘The String of Pearls’.

The stories were collected and published in book form as The Crime Club by Eveleigh Nash in 1915, apparently before their run in The Red Book Magazine had ended. In 1929, keen to have a book of short stories in the initial run of their new sixpenny Detective Story Club series, William Collins licensed the rights from Nash to print a cheap edition of the book, which was published in July 1929; The Grell Mystery and The Rogues’ Syndicate would follow within a year. Like many of the other early books in that series, The Crime Club also appeared in Collins’ ‘Piccadilly Novels’ imprint as an exclusive edition for Boots Pure Drug Co. Ltd (who also sold books), using the same typesetting and with the painting from the back of the Detective Story Club jacket transposed to the front.

Frank Froëst gave up writing in 1916 when his wife died, focusing on council work until the onset of blindness forced him into retirement and a convalescent home in Weston-super-Mare, where he died in 1930 at the age of 71. However, his association with George Dilnot continued, helping him to research his landmark book, The Story of Scotland Yard (1927), a completely new and expanded version of his first book. Dilnot continued to write about the police and true crime, including two volumes in Geoffrey Bles’s Famous Trials series, on which he was Series Editor, and revisited the subject of the Yard again with New Scotland Yard in 1938. But he was much more prolific in fiction, writing another 16 novels under his own name, with series characters including Jim Strang, Horace Elver, Val Emery and Inspector Strickland, plus three books for the popular Sexton Blake series.

When the reissue of The Crime Club came out in 1929, George Dilnot was therefore still very active and by then better known to readers than Frank Froëst. The book enjoyed a new lease of life, and within a year there were 19 titles in the Detective Story Club series. One of the secrets of its success, like so many cheap editions being published at that time, was their availability in newsagents and tobacconists as well as traditional bookshops (many of whom frowned upon the concept of cheap editions and would not stock them). Their success convinced Collins to chase more sales from this market by launching its own monthly magazine, and in June 1930 ‘The Detective Story Club Limited’ published a bold offshoot: Hush Magazine.

Like the book series that inspired it, Hush (the word Magazine being added to its title from issue No. 3) sold for just sixpence and sported brightly coloured covers, usually featuring the clichéd dame in distress, and contained in its 128 pages a mixture of fiction stories and non-fiction articles, some with new line drawings, and a small amount of advertising. The covers proudly proclaimed that the monthly magazine was ‘Edited by Edgar Wallace’, and indeed every issue began with a Wallace story—and usually a page advertising his new Collins book The Terror and/or The Educated Man. But like the more famous and longer-running Edgar Wallace Mystery Magazine that began in 1964, Wallace was not involved; the compilation and editing was by an uncredited George Dilnot. He adapted his own The Story of Scotland Yard, serialised every month from issue No. 3, and recycled some of his stories from The Red Book Magazine, interestingly dropping Frank Froëst’s name from them.

Hush Magazine ceased publication after only a year with No. 13 dated June 1931. There was no indication inside that it would be the last, with two ‘Next Month …’ adverts appearing in its pages. Collins was not a magazine publisher, and either the effort of compiling a varied and illustrated monthly collection of stories had got too much for them, or the circulation figures simply dropped below a sustainable level. Over its run, however, George Dilnot and the team had assembled a respectable if increasingly predictable mix of content, with regular reprints of fiction stories by stalwarts including J. S. Fletcher, Arthur B. Reeve, Sydney Horler, H. de Vere Stacpoole, Maurice Leblanc, G. D. H. & M. Cole, Edgar Allan Poe and even H. G. Wells. The most notable inclusion was a run of five Miss Marple stories by Agatha Christie beginning in November 1930, the month following the character’s very first book appearance in The Murder at the Vicarage, and which would not themselves appear in a book until The Thirteen Problems in June 1932. The publication of one-off detective stories by unknown authors in amongst these popular names provided some interesting reading, but this aspect of the magazine was soon curtailed as it was presumably the well-known names, emblazoned on the covers, who guaranteed sales.

Undaunted after a year on the magazine, George Dilnot returned to writing novels with The Thousandth Case (1932), averaging a book a year throughout the 1930s. His final novel was a Nazi war thriller, Counter-Spy, published by Geoffrey Bles in 1942. At almost 60 years old, Dilnot appears like Frank Froëst to have decided to stop writing ahead of retirement, and died nearly a decade later on 23 February 1951 in East Molesey in Surrey, aged 68.

Of all their books, The Crime Club is probably the least well remembered of any by Froëst or Dilnot, such is the fate of collections of short stories in most writers’ careers. Largely typical of detective stories of their era, the most interesting now is ‘The Red-Haired Pickpocket’ (from The Red Book Magazine, February 1915) as a rare example of a plot being ‘borrowed’ by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. The solution to ‘The Problem of Thor Bridge’, published in The Strand Magazine in two parts in February and March 1922, and collected in The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes, is so similar, even down to the small mark on the side of the bridge, that it doesn’t need Sherlock Holmes to deduce that Conan Doyle must have read the Froëst and Dilnot story.

In addition to the dozen stories that comprised The Crime Club, the pair collaborated to write three more in the same vein also for The Red Book Magazine: ‘Crossed Trails’, ‘The Dagger’ and ‘Found—A Pearl’ appeared in the February, August and September issues of 1916. One hundred years later, they are reprinted here for the first time in book form.

If the stories were forgotten, at least their collective title was to live on in another Collins publishing initiative even more ambitious than Hush Magazine—and one with decidedly more success. On 6 May 1930 Philip MacDonald’s detective novel The Noose was the first of the monthly ‘Recommended’ titles to be published by a brand new imprint—the Crime Club. But that is another story.

DAVID BRAWN

March 2016

I (#u25cd526d-d141-549d-9dbe-989ba0fe2bdb)

THE CRIME CLUB (#u25cd526d-d141-549d-9dbe-989ba0fe2bdb)

YOU will seek in vain, in any book of reference, for the name of the Crime Club. Purists may find a reason in the fact that a club without subscriptions, officials, or headed notepaper is no club at all. The real explanation probably is that the club avoids advertisement. It is content to know that even in its obscurity it is the most exclusive club in the world.

No member is ever elected; no member ever resigns. Yet the wrong man is never admitted, the right man rarely excluded. Its members are confined not only to one profession but to the picked men even of that profession. Its headquarters is as unostentatious as its existence—a little hotel handy to the Strand wherein some years ago Forrester and Blake of the Criminal Investigation Department had discovered a discreet manager, a capable chef, and a back dining-room.

The progress of time, and the tact of the manager, had conceded a sitting-room with a dozen or so big and deep arm-chairs. From noon onwards, the two apartments had become sacred to the Crime Club.

Quiet, comfortable-looking men dropped in for luncheon or dinner and a chat that was as likely to cover gardening or politics as murder or burglary. Perhaps the only trait that they showed in common was some indefinable trick of humour that lurked in their faces. An experienced detective has seen too much to take himself too seriously.

The rank and file of the world’s detective services have no entrée to the Crime Club. Only men whose repute is beyond suspicion are among its members. Strictly, it is an international club, for although its most determined frequenters are a dozen Scotland Yard men, there is always a sprinkling of detectives from abroad to be found there. You may see perhaps a thin, hawk-faced Pinkerton man grimly chaffing an excitable, black-bearded little Italian, none other than the redoubtable Cipriano of the Italian Secret Service. In the group about the fire are Kuntze of Berlin—a stolid, bovine-faced man whose looks belie the subtlety of a tempered brain; Heldon Foyle, the tall, urbane superintendent of the Criminal Investigation Department; a jolly-faced, fat officer from the Central Office in New York; the slim-built, grey-moustached commissioner of a great overseas police force—himself an old Scotland Yard hand; a sprucely-dressed Frenchman from the Service de Sûreté; a provincial chief constable; a private inquiry agent so fastidious about the selection of his clients that he is making only a couple of thousand a year instead of the five thousand that could be his if he did not object to dirty hands; and a couple of chief inspectors from the Yard.

Search the newspaper files of the world and you will here and there get a hint of remarkable things done by these men—of supreme feats of organisation in pursuit, of subtleties in unveiling mysteries, of bulldog courage and tenacity, of quick-witted resource in emergencies. You will not find all the truth there because there are sometimes happenings of which it is not well all the truth should be known; but you will gather much from the manner of men they are.

Sometimes, over coffee and cigars, the talk may drift to some of the affairs of the profession. Some of these find a place in the present chronicles.

II (#u25cd526d-d141-549d-9dbe-989ba0fe2bdb)

THE RED-HAIRED PICKPOCKET (#u25cd526d-d141-549d-9dbe-989ba0fe2bdb)

JIMMIE ILES was ‘some dip’. That was how he would have put it himself. In the archives of the New York Central Detective Bureau the description was less concise, but even more plain: ‘James (Jimmie) Iles, alias Red Jimmie, alias, etc … expert pickpocket …’

And Red Jimmie, whose hair was flame coloured and whose indomitable smile flashed from ear to ear on the slightest provocation, would have been lacking in the vanity of the underworld if he had not been proud of his reputation at Mulberry Street. Nevertheless, fame has its disadvantages, and though he was on friendly terms with the headquarters staff individually, he hated the system that had of late prevented his applying his undoubted talents to full profit.

England beckoned him—England, where he could make a fresh start with the past all put behind him. Do not make a mistake: Jimmie had no intention of reform. But in England there were no records, and consequently the police would not be allowed points in the game. It would be hard, therefore, if an energetic, painstaking man could not pick up enough to keep him in bread and butter.

Behold Jimmie, therefore, a first-class passenger on the S.S. Fortunia—‘Mr James Strickland’ on the passenger list—a suit in the Renaissance style of architecture built about him, the skirts of his coat descending well towards his knees, his peg-top trousers roomy and with a cast-iron crease. Behold him explaining for the fiftieth time to one of his sometime ‘stalls’ the reason that had driven him from God’s own country.

‘I’m too good-natured. That’s what’s the matter with me. The bulls are right on to me. If I carried a gun or hit one of ’em, like Dutch Fred, I might get away with it sometimes. But I can’t do it. They’re good boys, though they’ve got into a kind of habit of pulling me whenever they’re feeling lonely. I can’t go anywhere without a fourt’ of July procession of sleuths taggin’ after me— Holy Moses, there’s one there now. How do you do, Mr Murray? Say, shall we find if there’s a saloon?’

Detective-Sergeant Murray grinned affably. ‘Not for mine, Jimmie old lad. I’ve got that kind of lonesome feeling. Won’t you see me home?’

Jimmie thrilled with a tremor of familiar apprehension. ‘Honest to Gawd, I ain’t done a thing,’ he declared earnestly. ‘You’re only jollying, Mr Murray?’

The officer laughed and vanished. Jimmie decided to make himself inconspicuous till the vessel sailed. Luckily for his peace of mind, he did not know that the Central Office was paying him the compliment of a special cable in order that he might receive proper attention when he landed.

Jimmie was ‘good’ on board, though more than once he was tempted. It was not till he was on the boat-train from Liverpool to London that he fell. There was only one fellow-passenger in the compartment with him—a burly, prosperous man of middle age whom Jimmie knew from ship-board gossip to be one Sweeney, partner in a Detroit firm of hardware merchants. There was a comfortable bulge in his right-hand breast pocket—a bulge that made Jimmie’s mouth water. He had no fear but that he could reduce that swelling when he chose. The only trouble was ‘the getaway’. He had no ‘stalls’ to whom to pass the booty. He would have to lift the pocket-book as they got out at Euston if he did it at all. It was too risky to chance it before.

Five minutes before the train drew in at Euston, Sweeney began to collect his hand baggage. He patted his breast pocket to make sure that the pocket-book was still there. Jimmie felt pleased that he had restrained himself. He brushed by Sweeney as the train drew up, and as he passed on to the platform he knew the exultation of the artist in a finished piece of work. The pocket-book was in his possession.

Not until he had reached his hotel, and was safe in the seclusion of his own room did he examine the prize—having first ordered a fire in view of eventualities. There was a bunch of greenbacks and English notes totalling up to forty pounds—not a bad haul. Also there were a score or so of letters. Jimmie dropped the pocket-book itself on the fire, and raked the coals round it. Then he settled himself to read the correspondence before consigning it to the flames. Waste not, want not; and although Jimmie held rigidly to the line of business in which he was so adept, he was not averse to profiting from the by-products. One never knew what information might be in a letter. Jimmie had more than once gained a hint which, passed on to the right quarters, had earned him a ‘rake off’ from a robbery that was decidedly acceptable.

There seemed, however, nothing of that kind here. The letters were merely ordinary business jargon on commonplaces of commerce, and half a dozen or so introductions which a business man visiting Europe might be expected to carry. One by one the flames consumed them. Then he came to the last one and hitched his shoulders as he read. It had been printed by pencil, evidently at some trouble.

‘DEAR SWEENEY,—We are not going to be played with any longer. If you are in earnest you will come over and see us. The Fortunia sails on the seventeenth. The evening following her arrival, one of us will wait for you between ten and twelve at the Albert Suspension Bridge, Battersea. You will make up your mind to come if you are wise. We can then settle matters.—O. J.’

A man may be a pickpocket and retain a certain amount of human nature. A crook who is in business for profit rarely has opportunities to consider romance. If there is anything in the nature of a show, he usually plays the part of the foiled villain. So if he has a taste that way he indulges in fiction, the theatre, or the cinema, so that he can safely gratify his natural sympathies on the side of virtue. Jimmie was fond of the cinema. Often he had been so engrossed by the hair-raising exploits of a detective that he had totally neglected the natural facilities afforded by darkness and entertainment.

Now, however, he was suddenly plunged into an affair that promised real life melodrama. The printed characters, the mysterious appointment late at night, the ambiguous threat, were something for his imagination to gloat over. His fertile brain wove fancies of the Black Hand, the Mafia, and kindred blackmailing societies which the Sunday editions of the New York papers had painted crimson in his mind. He thrust the letter into the fire, and went out in search of one Four-fingered Foster, sometime an associate of his in New York, now established in a snug little business ‘bunco steering’ in London. Foster had been notified in advance of his coming.

He found his four-fingered friend established under the rôle of an insurance agent at a Brixton boarding-house, and Foster was willing and anxious to show the friend of his youth the town. So thoroughly indeed did they celebrate the reunion that ten o’clock had gone before Jimmie recalled the note. He swallowed the remnants of some poisonous decoction while they lounged before the tall counter of an American bar near Leicester Square.

‘Say, Ted,’ he remarked, his pronunciation extremely painstaking. ‘Where’s Albert Bridge?’

‘Search me,’ answered his friend. ‘Who is he? What’s your notion?’

‘It’s a place,’ exclaimed Jimmie. ‘I gotta get there. Got a—hic—’pointment.’

‘We’ll go get a cab,’ said Foster, staggering away from the bar. ‘Taxi driver sure to know.’

Jimmie grabbed him by the lapel of his coat. By this time he had made up his mind that the Black Hand had got its clutches on the prosperous Sweeney, and he had a fancy that he might play the part of hero in the melodrama. Friendship was all very well, but it could be stretched too far.

‘’Scuse me, Ted.’ He rolled a little and steadied himself with one hand on the bar counter. ‘Most particular—private—hic—’pointment.’

‘Aw—if it’s a skirt—’ Foster was contemptuous.

Jimmie did not enlighten him. His wits never entirely deserted him. He moved uncertainly to the door, explained his need to the uniformed door-keeper, and soon was flying south-west in a neat green taxi.

The driver had to rouse him when he reached his destination. Jimmie paid him off and began to walk under the giant tentacles of the suspension bridge, his blue eyes roving restlessly about. It was very lonely. He passed a policeman, and then a stout man came sauntering aimlessly along. Sweeney did not seem to recognise Jimmie, and Jimmie did not wish to attract his attention yet. Apparently the Black Hand emissary—Jimmie was sure it was the Black Hand—had not yet turned up. Out of the corner of his eyes he saw Sweeney standing absently near the iron rail gazing down on the swirling, blackened waters beneath. The pickpocket passed on.

He had gone a dozen paces when a thud as of a heavy hammer falling upon wood brought him about with a jerk. He had recognised the unmistakable report of an automatic pistol. Into his line of sight came a vision of Sweeney, no longer on the pavement, but in the centre of the roadway. He was on his knees, and while Jimmie ran, he fell forward. There was no sign of an assailant.

Jimmie knelt and raised the fallen man till the body was supported by his knee. There was a thin trickle of blood from the temple—such a trickle as might be caused by a superficial surface cut. The American loosened the dead man’s collar.

It had all happened in a few seconds, and even while he was trying to discover if there was life remaining in the limp body, the constable he had passed came running up. ‘What’s wrong here?’ he demanded.

Jimmie, satisfied that the man was dead, laid the body back gently, and brushed the dust from his trouser-knees as he stood up. ‘This guy’s been shot,’ he said. ‘The sport that did it can’t have got far. He must have been hiding behind one of the bridge supports.’

The constable placed a whistle to his mouth in swift summons. Then he in turn knelt and examined the dead man. Jimmie stood by, his hands thrust deep in his pockets, his eyes searching every shadow where an assassin might still be in hiding.

The deserted bridge had suddenly become alive. In the magical fashion in which a crowd springs up in places seemingly isolated, scores of people were concentrating on the spot. Among them were dotted the blue uniforms of half a dozen policemen.

Jimmie had given up any idea of being a hero, but he still saw the tragedy with the glamour of melodrama. He watched with interest the effective way in which the police handled the emergency. A sergeant exchanged a few swift words with the original constable, and then took charge. The crowd was swept back for fifty yards on each side of the murdered man. Jimmie would fain have been swept with it, but a heavy hand compressed his arm and detained him.

The sergeant gave swift orders to a cyclist policeman. ‘Slip off to the station. We want the divisional surgeon and an ambulance. They’ll let the Criminal Investigation people know.’

A murder, whatever the circumstances, is invariably dealt with by the Criminal Investigation Department. The uniformed police may be first engaged, but the detective force is always called in.

‘Now, Sullivan, what do you know about this?’

The constable addressed straightened himself up. ‘I was patrolling the bridge about five minutes ago,’ he said. ‘I passed him’—he nodded to the dead man. ‘He was walking slowly to the south side. I didn’t pay much attention. A little farther on I passed this chap’—he indicated Jimmie—‘but I didn’t pay any particular attention. I had just reached the other end when I heard a shot. I ran back, and found the first man being supported by the other, who was searching him. There were no other persons on the bridge to my knowledge.’

Jimmie’s mouth opened wide. He was thunderstruck. ‘Searching him!’ he ejaculated. ‘Say, Cap’—he was not quite sure of the sergeant’s rank—‘I never saw the guy in my life before. I was taking a look around when I heard a shot. I was just loosening his clothes when this man comes up.’

He was too paralysed to put all he wanted to say into coherent shape. He was sober enough now. A man confronted with a deadly peril can compress a great deal of thinking into one or two seconds. Jimmie could see any number of points that told against him, and he strove vainly to concoct some plausible explanation. The entire truth he rejected as seeming too wild for credit.

‘Better keep anything you’re going to say for Mr Whipple,’ advised the sergeant. ‘Two of you had better take him to the station.’

With his head buried in his hands, Jimmie sat disconsolate on a police cell bed. He was filled with apprehension, and the more he considered things, the more gloomy the outlook appeared. For an hour or more he waited, and at last he heard footsteps in the corridor. A face peered through the ‘Judas hole’ in the cell door, and then the lock clicked.

‘Come on!’ ordered a uniformed inspector. ‘Mr Whipple wants to see you.’

‘Who’s Mr Whipple?’ demanded Jimmie drearily.

‘Divisional detective-inspector. Come, hurry up!’

There were places in the United States where Jimmie had been through the ‘sweat-box’ and though he had heard that methods of that kind were barred in England, he felt a trifle nervous. He preceded the inspector along the cell-lined corridor, through the charge-room, and up a flight of stairs to a well-lighted little office. Two or three broad-shouldered men in mufti were standing about. A youth seated at a table with some blank sheets of paper in front of him was sharpening a pencil. A slim, pleasant-faced man was standing near the fireplace with a bowler hat on his head and dangling a pair of gloves aimlessly to and fro. It was his eyes that Jimmie met. He knew without the necessity of words that the man was Whipple. He pulled himself together for the ordeal of bullying that he half expected.

‘I don’t know nothin’ about it, chief,’ he opened abruptly and with some anxiety. ‘I’m a stranger here, and I never saw the guy before.’

‘Take it easy, my lad,’ said Whipple quietly. ‘Nobody has said you killed him yet. I want to ask you one or two questions. You needn’t answer unless you like, you know. If you can convince us that you were there only by accident, and had no hand in the murder, so much the better. But remember you’re not forced to answer. Everything you say will be written down. Give him a drink, somebody. Now take it quietly, old chap. What’s your name?’

His voice was soothing, almost sympathetic. It gave Jimmie the impression, as it was, intended to, that here was a man who would be scrupulously fair. He drank the brandy which someone passed to him, and for an instant his old, wide-mouthed smile flashed out. The spirit gave him a momentary touch of confidence.

‘That’s all right, boss. James Strickland’s my name. I’m from New York. Come over in the Fortunia and landed this morning.’

‘What are you?’

‘Piano tuner.’ The trade was the first one that occurred to Jimmie. ‘Over here to see if there’s an opening,’ he rattled glibly. ‘Trade’s slack the other side.’ The shorthand writer’s pencil scratched rapidly over the paper. Whipple’s face was expressionless.

Question succeeded question, each one quietly put, each answer received without comment. Jimmie was becoming involved in an inextricable tangle of lies. Had not the horrible fear still loomed over him, he might have avoided contradictions, extraordinary improbabilities, and constructed a connected, if false, story. And he could see, not in his interlocutor’s face, but in the faces of the others, a scepticism which they scarcely troubled to conceal.

The catechism finished, Whipple began drawing on his gloves.

‘That will do. You will be detained till we have made some more inquiries.’

Jimmie shuddered. ‘You don’t really think I done this, boss? You aren’t goin’—’

‘You’re not charged yet,’ said Whipple. ‘You’re only detained till we know more about things.’

It was a poor consolation, but with it Jimmie had to be content. He was taken below, and Whipple turned an inquiring face on one of his sergeants. The man made a significant grimace. ‘Guilty as blazes, sir,’ he said emphatically. ‘What did he want to tell that string of lies for?’

‘I don’t know,’ said Whipple thoughtfully. ‘You’d be thrown a little off your balance, Newton, if you were suddenly up against it. He’s a liar, but he’s not necessarily a murderer.’

Newton grunted, but ventured no open dissent till his superior had gone. He was a shrewd man in dealing with the commonplaces of crime, but he lacked subtlety, and accordingly despised it. ‘The guvnor’s too kid-glove,’ he complained with asperity to the uniformed inspector. ‘What’s the use of mucking about? The bloke’s a Yankee crook. He admits he came over in the Fortunia, and says he don’t know Sweeney, who came over in the same boat. Why, he must have been laying for him. He must have shadowed him till he got a fair chance. Mark me, when we’ve traced those notes we took off Strickland, we shall find that they were originally paid out to Sweeney. Waste of time finicking about, I call it.’

Now some of this reasoning had been in Whipple’s mind, but he liked to feel the ground secure under his feet before he took an irrevocable step. There was no hurry—at any rate for the twenty-four hours during which he was entitled to detain Jimmie on suspicion without making a charge. But there were certain points on which he was not entirely satisfied.

He was on hand at Scotland Yard early next morning. The report of the tragedy was in the morning papers, but they had given it little prominence. From their point of view it was of little news value—just a shooting affray, with a man detained. This was the view the superintendent of the Criminal Investigation Department, to whom Whipple had come to report, took of it.

‘Straightforward case, isn’t it, Whipple?’

‘There are one or two queer points about it, sir. I must admit it looks rather bad for Strickland, but somehow I don’t believe he did it. I can’t say why, but that’s my impression.’

‘You must be careful of impressions, Whipple. They carry you away from the facts sometimes.’

‘I know that. Well, the facts are these: Sweeney, the dead man, was the president of a hardware company at Detroit. I sent a cable off last night. He had come over partly on business, partly on pleasure, and was held in very good repute there. About five minutes ago I got this fresh cable.’ He smoothed out a yellow strip with his hand and read: ‘“News Sweeney’s death precipitated crash his firm. His business unsound for years. Insurance company informs us recently increased life premiums for half-million dollars. Suspect fraud. Request you will make stringent tests of identity, alternatively suspect suicide.” That’s signed by the Detroit Chief of Police.’

The superintendent stretched out a hand and took the cablegram. He read it through twice with puckered brows. ‘That’s a queer development,’ he admitted. ‘I don’t see what they’re getting at. If the murdered man is not Sweeney, that hypothesis assumes that Sweeney got someone else to impersonate him and that the second person knew he was to be killed. That’s ridiculous.’

‘So I think, sir. There’s more to the suicide end. The divisional surgeon says that the dead man’s temple was blackened by the explosion of the pistol. That shows that the weapon, when it was fired, was but a few inches from his face. Of course, when I saw the surgeon I didn’t know what this cable tells us, but luckily I put the point to him. There was no weapon found. I asked him if, supposing that Sweeney had killed himself, he could have thrown the pistol into the water after pulling the trigger—it was a distance of several yards to the parapet of the bridge. He was emphatic that it was impossible.’

‘Then it comes back to murder after all. Yes. it’s certainly curious about the insurance. Who’s the chap you’ve got in?’

Jimmie would have been interested in the reply even had he been less vitally concerned. It would have shown him how vain were his hopes of cutting away from his record. ‘A little red-haired chap with a big mouth, who gave the name Strickland—a Yankee pickpocket, Jimmie Iles, or Red Jimmie. You’ll remember, sir, New York cabled us he had sailed.’

‘Yes, I remember. We ought to have something about him then.’

‘We have. I spent part of last night picking it up. The Liverpool men spotted him in a compartment of the boat-train, alone with a man who fills the description of Sweeney. Sergeant Fuller, who was on duty at Euston, saw him when he arrived and took the number of his cab. He was not with Sweeney then. We found the cabman early this morning. He had driven him to a little hotel off the Strand. The hotel people remember him because he wanted a fire in his bedroom—a fire this weather! He went up there and stayed for over an hour. Then he went straight out.

‘At nine o’clock Tamplin of the West End saw Four-fingered Foster in the Dewville Bar, Coventry Street, with a red-haired American whom he thought was being strung. The Grape Street people recalled this when the tape report of the murder came over to them. I sent a man to rake out Foster, and sure enough his red-haired pal was Jimmie. Foster said they had parted in the Strand about eleven o’clock. Jimmie said he had an appointment at the Albert Bridge—Foster thought with a girl …

‘Those are pretty well all the facts, except this: when Jimmie was searched at the police station there were found on him three five-pound notes. These notes had been issued to Sweeney by a bank at Detroit before he left. I have the man’s own statement here, sir, if you’d care to look at it. It’s a string of lies.’

His chief waved aside the document and fiddled with his pince-nez as he considered the problem for a while. ‘You’re right to go easy, Whipple, but don’t overdo it. There’s almost enough evidence as it is to hang Red Jimmie. Intuition is good, but a jury won’t be interested in your psychology. They’d sooner read a book.’

‘Very good, sir.’ The detective-inspector went away, still far from satisfied. In view of the evidence now accumulated, he would have been inclined to believe Jimmie guilty had it not been for the singular news of Sweeney’s smash and the insurance. Coincidence is a factor in criminal investigation work, but this was straining it. If Sweeney had been murdered, the crime had come just right to provide for his family.

‘There’s some point that I’ve overlooked,’ he murmured to himself. ‘I can’t quite place it.’

He went back over the Albert Bridge to the police station, but no inspiration came to him. There was a bundle of reports awaiting him in his office, but after a casual glance he flung them aside and went down to the cells. He wanted to see Jimmie alone.

Jimmie looked up with pitifully haggard face as the door clanged behind the detective. Whipple nodded cheerfully and sat down.

‘Jimmie,’ he said familiarly, ‘wouldn’t you like to give me the straight griffin? I’ve heard from New York. You’d better let me know exactly what happened. What passed between you and Sweeney in the train coming down from Liverpool?’

He spoke in a quiet, conversational tone, but Jimmie jerked his head back as though to avoid a blow. He had had plenty of time to reflect on the leading points of circumstantial evidence that told against him. It staggered him more than a little that the police had been so quickly able to follow his trail backwards. He was conscious of his innocence of the major crime, conscious also that there was nothing he could do or say which would get away from the deadly array of facts that pointed against him.

‘Well, Jimmie?’ said Whipple persuasively.

Jimmie ran a hand through his dishevelled red hair. Then he shook himself as though trying to throw off the thoughts that possessed him. ‘See here, boss,’ he cried in an impulsive burst, ‘I’ll put you wise to the whole shemozzle. You won’t believe me anyway, but it’s the solemn truth, so help me. The bulls, they wouldn’t give me a rest in New York, so I chased myself over here where I’ve got one or two chums.’

‘Four-fingered Foster?’ queried Whipple absently. His thoughts were quite away from Jimmie, but he was nevertheless keenly following every word.

‘Has he squealed? Never mind, it don’t matter. Well, on the boat I got some chances, but I held myself in. There’d been a Central Office man to see me off, and I didn’t know but what he might have passed the word. I cut out the funny business till I got ashore, but I marked out one or two likely guys, Sweeney amongst them. Of course I steered clear of them on the ship, didn’t talk to ’em or nothing. I didn’t want to be noticed too much—you understand? When we shifted over into the boat-train at Liverpool, I saw Sweeney on his lonesome and got into the carriage with him. I lifted his leather from him—I admit that, boss—just as we reached London.’

‘You picked his pocket?’

‘Yes, his pocket-book. Then I went on to my hotel and sorted out the stuff. Some of them notes they took off me when they brought me in was among them. Then there was a lot of letters.’

‘What did you do with them?’

A flash of cunning crossed Jimmie’s face. ‘What do you think? Burnt ’em. Things like that don’t talk when they’re in the fire. There was one there, though, that I wish I’d saved now. It was written in print, if you understand what I mean, and told Sweeney to meet someone who had wrote it at Albert Bridge.’

‘Wait a minute. Can’t you remember exactly what it said?’

Jimmie wrinkled his brow in cogitation. Slowly he repeated the letter, which Whipple took down in shorthand on the back of an envelope. ‘I thought,’ said Jimmie, a little haltingly, ‘that I might butt in and catch this Black Hand gang and do Sweeney a turn. You see, I never believed in this gun-play myself, and I thought if I could stop it I might put myself right with Sweeney and perhaps he’d put me on to something—’

‘Take you into partnership,’ said Whipple; ‘saviour of his life and all that kind of thing.’

‘That’s it,’ agreed Jimmie.

Whipple smiled inwardly, but his face was grave. ‘And you want me to believe this yarn that you’ve been sitting thinking out, do you? Ah—don’t be a fool.’

Jimmie was utterly unstrung, or he never would have allowed himself a resort to violence which, even if it were successful, must have been futile. He thought he saw that he was still disbelieved, and had leapt at the detective’s throat with a mad idea of escape. Whipple side-stepped quickly, stooped, and the pickpocket felt himself lifted and flung to the other side of the cell.

‘Don’t be a fool, Jimmie,’ repeated Whipple mildly. ‘Even if you did knock me out, you couldn’t do anything. The cell is locked on the outside, and even I can’t get away till I ring. Sit down again quietly—that’s right. Now tell me one other thing: Did you notice anything in particular when you got on to the bridge last night?’

The other rubbed himself tenderly. ‘Nothing in particular,’ he answered. ‘There was a smell of paint—that’s not much good.’

‘Isn’t it!’ said Whipple, and pressed the bell that summoned the gaoler.

Two men sauntered on to the Albert Bridge. Whipple had got an idea, and though he had yet to test it, he was convinced that he was on the right track at last. He nodded as he saw the fresh green paint on the rails, and kept his eye fixed on them till he had passed a dozen yards by the spot where the murder had been committed. Then the two crossed to the other side of the bridge. The inspection of not more than three yards of the rail had taken place when Whipple halted and gave a satisfied chuckle. ‘We’re on it, Newton,’ he declared. ‘Look here.’

He pointed to some marks on the fresh paint-work. Across the top of the upper part of the rail, and continued downwards on the outer side, the paint had been scraped away. On the river side there were a couple of irregular bruises on the paint.

‘Kids been playing about,’ said the sergeant with decision. ‘I remember in the flat murder case we got mucked about by a lot of marks on a doorway. Some bright soul thought they were Arabic characters. It turned out they were boy scout marks.’

The detective-inspector laughed. ‘All right. Seeing’s believing with you. I’ll have a shot at this my own way, though. You might go and phone through to the river division. Ask ’em to send a couple of boats up here with drags.’

Newton spat over the rail into the tide. ‘You’ll not find anything with drags,’ he said, and with this Parthian shot, went to obey his instructions. Whipple remained in thought. Once, when there was a lull in the traffic, he paced out the distance between the marks on the rail and the place where Sweeney had been killed.

‘I’m right,’ he declared to himself; ‘I’d bet on it.’

Within twenty minutes two motor-launches were off the bridge and Newton had returned. Leaving him to mark the spot where the paint had been rubbed on the rail, Whipple went down to be picked up off a convenient wharf. A short discussion with the officer in charge as to the effect of the tide-drift, and they were in mid-stream again.

Then the drags splashed overboard and they began methodically to search the bed of the river. When half an hour had gone, Whipple was beginning to bite his lip. A drag came to the surface with whipcord about its lines. A constable began to unwind it. The detective leaned forward eagerly. ‘Steady, man, don’t let it break, whatever you do.’

They pulled the thing attached to the string on board and steered for the bank, Whipple in the glow of satisfaction that comes to every man who sees the end of his work in sight. He went straight to the police station telegraph room.

‘Whipple to Superintendent C.I.,’ he dictated. ‘Inform Detroit police Sweeney’s insurance void. Absolute proof committed suicide. Details to follow.’

Later, in his own office, his stenographer took down to be typed for record:

‘SIR,—I respectfully submit the following facts in regard to the supposed murder of the man Sweeney—

‘I first gained the impression that it was suicide from the doctor’s report that the explosion of a pistol had scorched the dead man’s face, showing that it had been held very closely to his head. This impression was strengthened by the fact that Iles, the American who was found by the body and at first suspected of the murder, could, if his motive was robbery, have attained this end more simply without violence. He is known to the New York police as an expert pickpocket. I need scarcely add that the knowledge that Sweeney was practically a bankrupt before he left the United States and had insured himself very heavily disposed me still more to the theory of suicide. If Sweeney had it in his mind to kill himself, it was indispensable to his purpose (since practically all life insurances are void in the event of suicide) to make the act appear (1) as an accident; (2) as a murder. He chose the latter.

‘Unfortunately for himself, Iles picked Sweeney’s pocket on the journey to London. Whether the latter discovered his loss before his death it is impossible to say with certainty. I believe not. Among the documents which Iles found was a letter in printed characters (which with others he burnt) demanding an appointment on the Albert Bridge, and conveying indirect threats. It is my belief that this letter was written by Sweeney himself with the idea that it would be found on his body and confirm the appearance of murder. I considered very fully the various means by which Sweeney might dispose of a pistol after he had shot himself. Only one practicable way occurred to me, and this was confirmed by an examination of the bridge rail, which had been newly painted. There were the paint stains on the dead man’s clothes, and Iles had said he noticed him looking over the rails.

‘It seemed to me that if the butt of a pistol were secured to a cord, and a heavy weight attached to the other end of the cord and dropped over the rail of the bridge before the fatal shot was fired, the grip on the pistol would relax and it would be automatically dragged into the water. The river was dragged at my request, and the discovery of an automatic pistol tied by a length of whipcord to a heavy leaden weight proved my theory right … With regard to Iles, I shall charge him with pocket-picking on his own confession, and ask that he shall be recommended for deportation as an undesirable alien … I have the honour to be your humble servant,

‘LIONEL WHIPPLE,

‘Divisional Detective-Inspector.’

‘All the same, sir,’ commented Detective-Sergeant Newton, ‘it looked like being that tough. He’s in luck that you tumbled to the gag.’

‘That’s right,’ agreed Whipple smilingly. ‘It’s luck—just luck.’

III (#ulink_e99d1212-d470-57d7-a7c0-4fd242482c48)

THE MAN WITH THE PALE-BLUE EYES (#ulink_e99d1212-d470-57d7-a7c0-4fd242482c48)

A BLUE haze of smoke which even the electric fans could not entirely dispel overhung the smoking saloon of the S.S. Columbia. With the procrastination of confirmed poker players, they had lingered at the game till well after midnight. Silvervale cut off a remark to glance at his cards. He yawned as he flung them down.

‘She can call herself Eleanor de Reszke or anything else she likes on the passenger list,’ he declared languidly, ‘but she’s Madeline Fulford all right, all right. She’s come on a bit in the last two years, though she always was a bit of a high stepper. Wonder if de Reszke knows anything about Crake?’

Across the table a sallow-faced man, whose play had hitherto evinced no lack of nerve, threw in a full hand, aces up, on a moderate rise. No one save himself knew that he had wasted one of the best of average poker hands. His fingers, lean and tremulous, drummed mechanically on the table. For a second a pair of lustreless, frowning blue eyes rested on Silvervale’s face.

‘So that’s the woman who was in the Crake case? It was her evidence that got the poor devil seven years, wasn’t it? As I remember the newspaper reports, she was a kind of devil incarnate.’

‘I wouldn’t go as far as that,’ observed Silvervale dryly, ‘and I’m a newspaper man myself. I didn’t hear the trial, but I saw her afterwards. It never came out why she gave him away. There must have been some mighty strong motive, for he had spent thousands on her. I guess there was another woman at the bottom of it. Anyway, her reasons don’t matter. She cleared an unpleasant trickster out of the way and put him where he belongs. But for her he might have been carrying on that swindling bank of his now. I’ll take three cards.’

The man with the pale-blue eyes jerked his head abruptly. ‘Yes, he’s where he belongs,’ he asserted, ‘and she—why, she’s Mrs de Reszke and a deuced pretty woman … Hello!’ He broke off short, staring with fascinated eyes beyond Silvervale. The journalist swerved round in his chair, to meet a livid face and furious eyes within a foot of his own.

It was Richard de Reszke himself. He had not made himself popular on ship-board—indeed, it is doubtful if he could ever have been popular in any society. A New Yorker who had made himself a millionaire in the boot trade, he was ungracious both in manner and speech. He had entered the saloon unperceived, and now his tall, usually shambling figure was unwontedly erect. His left hand—big and gnarled it was—fell with an ape-like clutch on Silvervale’s shoulder.

‘You scandal-mongering little ape,’ he snarled, with a vicious tightening of the lips under his grey moustache. ‘By God, you’ll admit you’re a liar, or I’ll shake the life out of you.’

The chair fell with a crash as he pulled the journalist forward. Men sprang to intervene between the two. Cursing and struggling, de Reszke was forced back, but it took four men to do it. Suddenly his resistance relaxed.

‘That’s all right,’ he said quietly. ‘We’ll let it go for now.’ A fresh access of passion shook him, and he shot out a malignant oath. ‘I’ll make you a sorry man yet for this, Mr Silvervale.’

The journalist had picked up the fallen chair. His face was flushed, but he answered coolly. ‘I apologise,’ he said quietly. ‘I had no business to talk of your wife.’

‘Then in front of these gentlemen you’ll admit you’re a liar.’

‘I guess not. I am sorry I said anything, but what I did say was the truth. Mrs de Reszke was Madeline Fulford, and she it was who gave evidence against Crake.’

The little group between the men stiffened in expectation of a new outburst. But none came. The stoop had come back to de Reszke’s shoulders, and he lifted one hand wearily to tug at his moustache. Then without another word he turned and shambled from the room.

There was a momentary silence, broken at last by the scratch of a match as someone lit a cigarette. The embarrassment was broken, and three or four men spoke at once.

‘Look out, Silvervale,’ said Bowen, a young New York banker. ‘Lucky for you we touch Southampton tomorrow. The old man is a-gunning for you, sure. His face meant murder.’

‘Thanks. I’ll look after my own corpse,’ drawled the journalist. He spoke with an ease he did not entirely feel. ‘I suppose the game’s broken up now. I’ve had enough excitement for one night. I’m going to turn in.’

The short remainder of the voyage, in spite of de Reszke’s threat and the prophecy of Bowen, passed without incident. It was not till he was back in London that the episode was recalled to Silvervale’s mind. The boat train had reached Waterloo in the early afternoon, and at six o’clock, Silvervale, for all that his two months’ vacation had yet three days to run, had been drawn into the stir and stress of Fleet Street.

The harrassed news editor of the Morning Wire was working at speed through a basket of accumulated copy. He paused long enough to shake hands and exchange a remark or two, and then resumed his labours with redoubled ardour, for he was eager to hand over the reins to his night assistant.

He snatched irritably at a piece of tape that was handed to him by a boy, and then, adjusting his pince-nez, glanced at Silvervale.

‘Here’s a funny thing, Silver. Didn’t you come back on the Columbia? Read that.’

Silvervale took the thin strip and slowly read it through:

‘5.40: Mrs Eleanor de Reszke, the wife of an American millionaire, was this afternoon found shot dead in her sitting-room at the Palatial Hotel. She had been at the hotel only an hour or two, having arrived by the Columbia from New York this morning.’

Hardened journalist though he was, with a close acquaintance with many of the bizarre aspects of tragedy, Silvervale could not repress a little shudder. Here was a grim sequel for which he was in a degree responsible. He traced the sequence of events clearly in his imagination from the moment when de Reszke first heard that his wife had been the associate and betrayer of a swindler, to the ultimate gust of passion that must have led to the tragedy when it was borne upon him that the statement was the truth.

‘Yes. It’s—it’s queer, Danvers,’ he said unsteadily, ‘deuced queer.’ Then with a realisation that the news editor was regarding him with curiosity: ‘I’m sorry, old man; you mustn’t ask me to handle the story. You’d better put Blackwood on it. It should be a good yarn, but I’m rather mixed up in it. I may be called as a witness.’

Few things are calculated to startle the news editor of a great morning newspaper, but this time Silvervale had certainly succeeded. To tell the truth, the young man was astonished at his own scruples. He made haste to escape before he could be questioned.

Out in Fleet Street he hailed a taxi and was driven straight to the Palatial Hotel. A couple of men were in the big hall, smilingly parrying the questions of half a dozen journalists. One of them shook his head as Silvervale pushed his way to the front.

‘Good Lord! Here’s another vulture. It’s no good, Mr Silvervale. We’ve just been telling your friends here that we don’t know anything. The doctors have not finished their examination yet.’

‘But it looks like suicide, Mr Forrester,’ interposed one of the crowd. ‘You’ve found a pistol.’

A knowing smile extended on Detective-Inspector Forrester’s genial countenance. ‘That won’t work, boys,’ he remonstrated with a reproving shake of his head. ‘You don’t draw me.’

Silvervale managed to get the detective aside. ‘You must give me five minutes,’ he whispered hastily. ‘I know who killed her. I came over in the same boat.’

Forrester thrust his hands deep in his trousers’ pockets. His brow puckered a little, and he studied the journalist’s face thoughtfully. For all his casual unworried air, his instinct rather than anything definite in the preliminary investigations had warned him that the case was likely to prove a difficult one. A detective—the real detective—is quite as willing to take short cuts in his work as any other business man.

‘The deuce you do,’ he said. ‘Come, let’s get out of this. Half a moment, Roker.’

His assistant disengaged himself from the other newspaper men, and Forrester led the way to the lift. At the third floor they emerged. Very quietly the door of the lift closed behind them, and half-unconsciously Silvervale found himself tiptoeing along the corridor, although in any event the soft carpet would have deadened all sound. A man standing stiffly against a white door flung it open as they approached. Within, a couple of men were bending over something on a couch, and two more were busy near the window overlooking the river. No one looked up. Forrester passed straight through to another and smaller room, and fitted his burly form to a basket arm-chair. He waved Silvervale to another one.

‘And now fire away, sonny,’ he said.

Concisely, in quick, succinct sentences, Silvervale told his story. As he concluded, Forrester drew a worn briar pipe from his pocket and packed it with a meditative forefinger.

‘Are you writing anything about this?’

‘Not a word. I know I may be wanted as a witness.’

‘That’s true.’ The inspector puffed contemplatively for a moment. ‘Then there’s this, I don’t mind telling you: That chap downstairs was right. There was a pistol—a five-chambered revolver—found clutched in that woman’s hand. But de Reszke is missing. He never came with her to the hotel.’

‘Then you think it is suicide after all?’

The detective leaned forward and levelled a heavy forefinger at his questioner. ‘You’ve earned a right to know something of this business, Mr Silvervale. It’s no suicide. The body was discovered by the maid just after five o’clock. No one had heard a shot, but that’s nothing—these walls are pretty well sound-proof. The dead woman was lying on a couch with the revolver in her hand—so the girl’s story runs. She thought her mistress was asleep, and it was only when she touched her and the weapon fell to the floor that she discovered she was dead. She was shot through the left eye.’

‘I see. You mean a woman wouldn’t kill herself that way. She’d poison or drown herself—some bloodless death.’

‘There is something in that, but it proves little by itself. But there are not many people who’d shoot themselves deliberately in the eye. It’s curious, but there—But to my mind the conclusive thing is the pistol. Any student of medical jurisprudence will tell you that usually it needs considerable force to relax the grip of a corpse from anything it is clutching at the moment of death. No, Mr Silvervale, this is a carefully calculated murder, if ever there was one. And I think your information will help us to fix the man. Roker’—he addressed his companion—‘you might get hold of the maid again. Get a full description of de Reszke, and there’s bound to be a photograph somewhere. Take ’em along to the Yard and have ’em circulated. We merely want to question him, mind. Now, Mr Silvervale, we’ll see what the doctors say.’

The two doctors, the police divisional surgeon and the medical man who had been first called on the discovery of the murder, had finished their examination as Forrester passed into the next room. He spoke a few words in an undertone to the surgeon, who nodded assentingly.

The two men by the window were still busy. Now Silvervale had an opportunity to see what occupied them. They were busy with scale plans of the room whereon were shown the relative positions of everything in the room, marked out even to inches. Photographs, he surmised, must already have been taken.

Forrester seemed to have forgotten Silvervale’s existence. As soon as the doctors had gone, the inspector had extracted a small bottle of black powder from his pocket and sprinkled it delicately over the open pages of a book resting on a table a couple of yards from the couch. Presently he blew the stuff away. The finger-prints had developed in relief on the white margin.

‘There’s a blotting-pad over there on the writing-table, Mr Silvervale,’ he said; ‘would you mind helping me for a moment?’

Forrester was cool and business-like, yet it was very gently that he lifted the dead white hands and impressed the finger-tips on a sheet of paper on top of the pad. Silently he compared the impressions with those on the book.

‘I’m only an amateur at this finger-print game,’ he said at last. ‘Grant ought to have been here. See if you make these prints agree, Mr Silvervale.’

Silvervale carried the book to the window and bent his brows over it. He found it slow work, but at last he raised his head. ‘These are her thumb-prints on the outer margin,’ he said. ‘The one at the bottom of the book is not hers.’

‘That’s how I make it. Now we can get a fair theory of how the thing was done: Mrs de Reszke was on the couch reading. The murderer entered softly from the corridor, closing the door behind him. She looked up and placed the book beside her. He must have fired point-blank. Then to work out his idea of suicide he placed the pistol in her hand, and, picking up the book, put it on the table. Here’s where we start from—a piece of indisputable proof when we catch the murderer.’

A little contempt at the apparent deliberation of the detective—at the finesse wasted on what seemed an obvious case—had come to Silvervale’s mind. He hazarded a suggestion; Forrester grinned.

‘I’ll bet a dollar I know what you’re thinking. I’m wasting my time meddling with details while the murderer’s escaping. Do you know I had five men here besides these’—he nodded towards the draughtsmen—‘questioning every one who might know anything about the case? Mrs de Reszke has received no one; no one resembling her husband has been seen in the hotel. Do you know that there is not one railway station in London, not one hotel that is not even now being searched for a trace of de Reszke? We are not so slow as our critics think. If de Reszke did this murder he won’t get away, you can take it from me. There’s plenty of people trying to catch him—I’ve seen to that.’

He checked himself suddenly as if he realised that he had for a while lost his wonted imperturbability. ‘I thought you knew better than to run away with the delusion that all we’ve got to do is to arrest a man we’ve fixed our suspicions on. In point of fact it is often more difficult to get material evidence of a moral certainty than to start without any facts at all.’

He moved heavily to the door. ‘I’m going on to the Yard,’ he said. ‘Care to come?’

As they turned under the big wrought-iron arch that spanned the entrance to New Scotland Yard, Silvervale noted that they avoided the little back door that leads to the Criminal Investigation Department and went up by the broad main entrance to those rooms on one of the topmost floors devoted to the Finger-print Department.

Grant, the chief of the department, a black-moustached giant with lined forehead and shrewd, penetrative eyes, was seated at a low table pushing a magnifying-glass across a sheet of paper. Forrester had clapped him heavily on the shoulder, and he wheeled around frowningly.

‘It’s you, is it?’ he growled. ‘One of these days you’ll play that trick too often, my lad. Of course, you come when every one’s gone home. What do you want?’

‘Don’t be peevish, old man,’ smiled Forrester, and seated himself on the table. ‘You’ll be sorry you weren’t more kind to me when the daisies are growing over my grave.’

‘Fungi, you mean,’ retorted Grant acidly. ‘What’s the bother?’

‘This.’ Forrester produced the book he had found at the hotel and the scrap of paper on which he had taken the murdered woman’s finger-prints. ‘It’s the Palatial Hotel business. The prints on the paper are those of Mrs de Reszke. They agree with those on the sides of the book. The one at the bottom of the book is that of the murderer.’

‘H’m.’ Grant glanced at the prints and gave a corroborative nod. ‘You’ll want photographs of these, I suppose?’

‘Yes—as soon as I can get them. I suppose you’ll have to have a search to make sure that the other print isn’t on the records. It’s unlikely, though.’

‘That will have to wait. I’ll have the photographs taken and sent down to you as soon as they’re ready. Now go away.’

He dismissed them abruptly, and they could hear his deep voice thundering into the telephone receiver as they made their exit. He was ordering a wire to be sent recalling one of the staff photographers. As in any other big business firm, the ordinary staff of Scotland Yard goes off duty at six.

Downstairs in his own room, Forrester found three or four subordinates and a handful of reports and messages awaiting him. His leisurely manner dropped from him. He became brisk, official, brusque. A shorthand clerk with open notebook was waiting, and to him the chief inspector poured out the bulk of his instructions to be forwarded by telegraph or telephone. Silvervale realised how vast and complex were the resources that were being handled to solve the mystery.

Forrester dismissed the clerk at last and turned abruptly on the waiting men. There was no waste of words on either side. As the final subordinate left the room, Forrester yawned and stretched himself wearily.

‘That’s all right,’ he said. ‘I guess we can’t do anything more for an hour or two. It may interest you, Mr Silvervale, to know that de Reszke has booked a passage back to New York in his own name, by the boat that leaves Liverpool the day after tomorrow. He called at the White Star offices at five o’clock. It’s a bluff, I guess, and pretty obvious at that. He thinks we’ll concentrate attention on that scent while he slips some other way. Yes—what is it?’

Someone had torn the door open hurriedly. A young man, tall and sparse, whispered a few words into Forrester’s ear. The chief inspector sat up as though galvanised. His hand searched for the telephone.

‘Get him put through here … You have a taxi-cab ready, Bolt. You may have to come with me.’ The young man vanished and Forrester spoke into the telephone. ‘Hello, that you, Gould?… Yes, this is Forrester … At the Metz, you say … How many men have you? All right, I’ll be along straight away. Good-bye.’

‘Located him?’ ventured Silvervale.

‘Yes.’ Forrester’s brow was puckered. ‘He’s at the Metz under his own name. Hanged if I can make it out. He’s either mad or he’s got the nerve of the very devil. Come on!’

Bolt was awaiting them in a taxi-cab outside, which whirled them swiftly away as they took their seats. They drew up in Piccadilly, a hundred yards or so from the severe arches of the great hotel, and walked forward till they were met by a bronzed, well-dressed man of middle age who nodded affably and fell into step with them.

‘Well, Gould?’ queried Forrester.

‘Everything serene, sir. He’s gone in to dinner. There’s two of our men dining at the next table.’

‘That’s all right then. I’ll see the manager and fix things.’

A commissionaire pushed back the revolving door and the four walked in.

Five minutes later a waiter crossed the softly-lighted dining-room with a card. It did not contain Forrester’s name—nor indeed that of anyone he knew. Nor did de Reszke seem to know it, for he frowned as the waiter presented it to him.

‘I don’t know any Mr Grahame Johnston,’ he said. ‘This isn’t for me.’

The waiter was deferential. ‘The gentleman said, “Mr John de Reszke,” sir. He says it’s very urgent, and wants you to spare him a minute in the smoking-room.’

The millionaire slowly divested himself of the serviette, and rising, shambled after the waiter. Curiously enough, one of the diners at the adjoining table seemed simultaneously to have occasion to leave the room by the same exit.

Forrester and his companions were waiting in a small room which had been placed at their disposal. As de Reszke was ushered in, the first face he caught sight of was that of Silvervale. His face lowered and he paused on the threshold.

Quickly and deftly Gould shouldered by him as though to pass out. De Reszke gave way, and the detective closed the door and leaned nonchalantly against it.

‘Mr de Reszke,’ said Forrester quickly, ‘I am a police officer. Your wife has been murdered since her arrival in London. If you wish to make any statement as to your movements you may do so, though I must warn you that unless you can definitely convince me that you had no hand in the murder I may have to arrest you.’

Blankly, uncomprehendingly, de Reszke stared in front of him as though he had not heard. His lean fingers clenched and unclenched, and his eyes had become dull. The police officers, although neither their attitudes nor their faces showed it, had braced themselves to overcome him at the first hint of resistance. But this man had no appearance of being the madman that Silvervale had pictured. The life seemed to have gone out of him.

‘You heard me?’ questioned Forrester sharply.

‘I heard you,’ said de Reszke dully. ‘You say Nell’s dead—no, not Nell—her name’s not Eleanor; it’s Madeline—Madeline Fulford; that’s it—she’s been murdered? I heard—ha! ha! ha!’ He broke into shrill uncanny laughter, and then pressing both hands to his temples pitched forward heavily to the floor.

‘A doctor, someone,’ ordered Forrester, and Gould vanished. Unconscious, de Reszke was lifted to a couch by the other three. Forrester shrugged his shoulders. ‘Looks like a bad job,’ he muttered.

The doctor summoned by Gould confirmed the suspicion. ‘It’s a paralytic stroke,’ he explained. ‘I doubt if he’ll ever get over it. You gentlemen are friends of his?’

Forrester inserted a couple of fingers in his waistcoat pocket. ‘Not exactly,’ he said. ‘We are police officials. There is my card.’

‘Ah!’ The doctor’s eyebrows jerked up. ‘Well, it’s no business of mine. Of course, it’s obvious that he’s had a shock.’

‘Of course,’ agreed Forrester.

The inevitable search of de Reszke’s room and baggage had been conducted with thoroughness, but it yielded nothing that seemed of importance to the investigation. Forrester voiced his misgivings as he walked back to Scotland Yard with Silvervale.

‘This business is running too smoothly. I don’t like it. I feel there’s a smack in the eye coming from somewhere. There’s several little odds and ends to be cleared up. It would have been easier if he hadn’t had that stroke.’

‘There’s the finger-print on the book,’ ventured Silvervale.

‘Yes. I took de Reszke’s and sent Bolt with them to the Yard. Grant will have fixed all that up by the time we get there.’

Grant was waiting for them when they arrived. On his table he had spread out a series of enlargements of finger-prints. He shook his head gravely at Forrester. ‘It’s no good, old chap,’ he said. ‘These things you sent me up by Bolt don’t tally.’

Forrester, suddenly arrested with his overcoat half off, felt his jaw drop. For a second he frowned upon Grant. Then he writhed himself free of the garment. ‘Don’t tally?’ he repeated. ‘You’re joking, Grant. They must.’

‘Well, they don’t.’

The chief detective-inspector brought his fist down with a bang on the table. He laid no claim to the superhuman intelligence of the story-book detectives. Therefore he was considerably annoyed at this abrupt discovery of a vital flaw in the chain of evidence that connected de Reszke with the murder. He had no personal feeling in the matter. It was merely the discontent of the business man at finding that work had been wasted. He brought his fist down with a bang on the table.

‘It beats me,’ he declared viciously. ‘It fairly beats me. Who else could have done it? Who else had a motive?’

Grant stole out of the room, and Silvervale rested his elbows on the table and his chin in his cupped hands, striving to recall some avenue of investigation that he might have overlooked.

Suddenly his face lightened and he jerked himself from his chair with a swift movement of his whole body. Ignoring the journalist, he rushed from the room. It was long before he returned. When he did he was accompanied by Grant.

‘Tell me’—he addressed Silvervale—‘did you ever see Crake?’

The other shook his head. ‘I was out of town when he was tried. It was after the case was over that I interviewed Madeline Fulford.’

Grant was frowning. ‘If I hadn’t seen the records, Forrester, I’d say you were mad. It’s the most unheard-of thing …’

‘We’ll see whether I’m mad or not,’ said the chief inspector grimly. He placed a photograph, the official side and full-face, before Silvervale. ‘Did you ever see that man before?’

‘No.’

‘Nor that?’ The second photograph was a studio portrait with the name of a Strand firm at the bottom. It awoke some vague reminiscence in Silvervale. He held it closer to the light.

‘Wait a minute.’ Grant placed a sheet of paper over the bottom of the face, hiding the moustache and chin. Recollection came to Silvervale in a flash. It was Norman, the man with the lustreless blue eyes who had commented on Madeline Fulford in the smoking-room of the Columbia.

He explained. ‘The hair’s done differently,’ he added, ‘but I can recognise the upper part of the face, though he’s older now than when this photograph was taken. Do you think he’s mixed up in this?’

‘Maybe,’ answered Forrester enigmatically. ‘I’ll have a man motor down to the prison now’—he was speaking to Grant—‘and we’ll go on to the Palatial. If I’m any judge he’ll still be there. His room was No. 472, almost opposite her suite. I had him questioned, of course, but I never dreamed—’

Silvervale lit a cigarette resignedly. ‘It’s all Greek to me,’ he complained. ‘Still, I have no right to ask questions.’

‘You’ll understand in an hour or two,’ said Forrester. ‘It would take too long to explain now. Come on and you’ll see what you’ll see.’

It was back to the Palatial Hotel that he took the journalist and a couple of subordinates. There he remained closeted with the manager for five minutes. He reappeared with that functionary, a master-key dangling on his finger.

‘Our bird’s at home,’ he said. ‘Gone to roost, probably.’

Nothing more was said till they reached the third floor. The manager led the way until they came opposite a door facing the suite which Mrs de Reszke had occupied. ‘This is No. 472,’ he said in a low voice. ‘Shall I knock?’

Forrester made a gesture of dissent and his hand fell coaxingly on the door. He made no sound as he pushed a key in the lock and turned it. With a sharp push the door flew open, and a quick, angry question was succeeded by confused sounds of a struggle. The next Silvervale saw was a pyjama-clad man being held on the bed with Forrester and a colleague at either wrist.

‘I don’t know who you are or the meaning of this outrage,’ he protested angrily. ‘Someone will have to pay for this.’

‘Hold on to his hand a minute, Roker,’ said Forrester, and one of the other detectives seized the wrist he had been grasping.

The chief inspector thrust his hand beneath the pillow and produced a small automatic pistol. ‘I just grabbed him in time,’ he said a little breathlessly.

‘I want to know—’ persisted the prisoner.

Forrester turned sternly upon him. ‘I am a police officer,’ he said. ‘I am arresting you as an escaped convict, one John Crake.’

Something approaching a gleam of interest shot into Crake’s lifeless eyes. ‘So that’s it, is it?’ he said quietly. ‘I wonder how you got on to it. According to official reckoning, John Crake has still got five years to serve.’

It was impossible to doubt that the man knew the real reason of his arrest, but his manner gave no hint of perturbation. He smiled sardonically as a shiver swept over his slight frame. ‘I suppose you aren’t going to take me to the police station in my sleeping-suit? Will these gentlemen allow me to dress?’