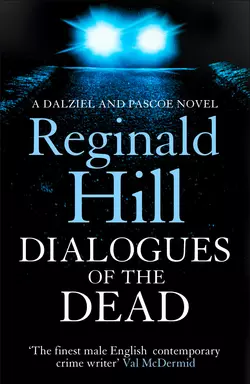

Dialogues of the Dead

Reginald Hill

New Dalziel and Pascoe novel from Britain’s finest male crime writer: ‘Reginald Hill stands head and shoulders above any other writer of homebred crime fiction’ Tom Hiney, ObserverA man drowns. Another dies in a motorbike crash. Two accidents … yet in a pair of so-called Dialogues sent to the Mid-Yorkshire Gazette as entries in a short story competition, someone seems to be taking responsibility for the deaths.In Mid-Yorkshire CID these claims are greeted with disbelief. But when the story is leaked to television and a third indisputable murder takes place, Dalziel and Pascoe find themselves playing a game no one knows the rules of against an opponent known only as the Wordman.

REGINALD HILL

DIALOGUES OF THE DEAD

A Dalziel and Pascoe novel

Copyright (#u776ac008-590a-524d-9fbc-ac6e3a8dfa74)

Harper An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain

in 2001 by HarperCollins

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Copyright © Reginald Hill 2001

Reginald Hill asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780007313198

Ebook Edition © JULY 2015 ISBN 9780007396368

Version: 2015-06-22

Contents

Cover (#ua8468d48-9c7d-5966-bb74-1d9b647d6671)

Title Page (#u6544f443-e6a0-562d-8819-7d658aaeec85)

Copyright

Epigraph (#ud988fcb4-7903-5d82-a393-ae7cb8ab09d5)

Chapter One: the first dialogue

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four: the second dialogue

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine: the third dialogue

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen: the fourth dialogue

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four: the fifth dialogue

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six: the sixth dialogue

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Chapter Thirty-Nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-One

Chapter Forty-Two: the seventh dialogue

Chapter Forty-Three

Chapter Forty-Four

Chapter Forty-Five

Chapter Forty-Six

Chapter Forty-Seven

Chapter Forty-Eight: the last dialogue

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author

Praise for Dialogues of the Dead

By Reginald Hill

About the Publisher

Epigraph (#ulink_b09d9f24-dc5f-56d0-8ed6-5661e0c83491)

paronomania (pəronə

'meInIə) [Factitious word derived from a conflation of PARONOMASIA [L. a. Gr. παρoνoμασια] Word-play + MANIA (see quot. 1823)]

1. A clinical obsession with word games.

1760 George, Lord LYTTELTON Dialogues of the Dead: No XXXV BACON: Is not yon fellow lying there Shakespeare, the scribbler? Why looks he so pale? GALEN: Aye, sir, ’tis he. A very pretty case of paronomania. Since coming here he has resolved a cryptogram in his plays which proves that you wrote them, since when he has not spoken word. 1823 Ld. BYRON Don Juan Canto xviii So paronomastic are his miscellanea, Hood’s doctors fear he’ll die of paronomania. 1927 HAL DILLINGER Through the Mind-Maze: A Casebook So advanced was Mr X’s paronomania that he attempted to kill his wife because of a message he claimed to have received via a cryptic clue in the Washington Post crossword.

2. The proprietary name of a board game for two players using tiles imprinted with letters to form words. Points are scored partly by addition of the numeric values accorded to each letter, but also as a result of certain relationships of sound and meaning between the words. All languages transcribable in Latin script may be used under certain variable rules.

1976Skulker Magazine, Vol 1 No. iv Though the aficionados of Paronomania contested the annual Championships with all their customary enthusiasm, ferocity and skill, the complex and esoteric nature of the game makes it unlikely that it will ever be degraded to the status of a national sport.

OED (2nd Edition)

Du sagst mir heimlich ein leises Bort Und gibst mir den Strauss von Inpressen. Ich wache auf, und der Strauss ist fort, Und’s Bort hab’ ich vergessen.* (#ulink_d7fbf428-71e5-598a-9175-fd031482a154)

Harry Heine (1800–1856)

I fear there is some maddening secret

Hid in your words (and at each turn of thought

Comes up a skull,) like an anatomy

Found in a weedy hole, ’mongst stones and roots

And straggling reptiles, with his tongueless mouth

Telling of murder …

Thomas Lovell Beddoes (1803–1849)

* (#ulink_e01b4905-c1c7-5a9c-be6c-6eb71f8630d1)A word in secret you softly say And give me a cypress spray sweetly. I wake and find that I’ve lost the spray And the word escapes me completely.

CHAPTER ONE (#u776ac008-590a-524d-9fbc-ac6e3a8dfa74)

the first dialogue (#u776ac008-590a-524d-9fbc-ac6e3a8dfa74)

Hi, there. How’re you doing?

Me, I’m fine, I think.

That’s right. It’s hard to tell sometimes, but there seems to be some movement at last. Funny old thing, life, isn’t it?

OK, death too. But life …

Just a short while ago, there I was, going nowhere and nowhere to go, stuck on the shelf, so to speak, past oozing through present into future with nothing of colour or action or excitement to quicken the senses …

Then suddenly one day I saw it!

Stretching out before me where it had always been, the long and winding path leading me through my Great Adventure, the start so close I felt I could reach out and touch it, the end so distant my mind reeled at the thought of what lay between.

But it’s a long step from a reeling mind to a mind in reality, and at first that’s where it stayed – that long and winding trail, I mean – in the mind, something to pass the long quiet hours with. Yet all the while I could hear my soul telling me, ‘Being a mental traveller is fine but it gets you no suntan!’

And my feet grew ever more restless.

Slowly the questions began to turn in my brain like a screensaver on a computer.

Could I possibly …?

Did I dare …?

That’s the trouble with paths.

Once found, they must be followed wherever they may lead, but sometimes the start is – how shall I put it? – so indefinite.

I needed a sign. Not necessarily something dramatic. A gentle nudge would do.

Or a whispered word.

Then one day I got it.

First the whispered word. Your whisper? I hoped so.

I heard it, interpreted it, wanted to believe it. But it was still so vague …

Yes, I was always a fearful child.

I needed something clearer.

And finally it came. More of a shoulder charge than a gentle nudge. A shout rather than a whisper. You might say it leapt out at me!

I could almost hear you laughing.

I couldn’t sleep that night for thinking about it. But the more I thought, the less clear it became. By three o’clock in the morning, I’d convinced myself it was mere accident and my Great Adventure must remain empty fantasy, a video to play behind the attentive eyes and sympathetic smile as I went about my daily business.

But an hour or so later as dawn’s rosy fingers began to massage the black skin of night, and a little bird began to pipe outside my window, I started to see things differently.

It could be simply my sense of unworthiness that was making me so hesitant. And in any case it wasn’t me who was doing the choosing, was it? The sign, to be a true sign, should be followed by a chance which I could not refuse. Because it wouldn’t be mere chance, of course, though by its very nature it was likely to be indefinite. Indeed, that was how I would recognize it. To start with at least I would be a passive actor in this Adventure, but once begun, then I would know without doubt that it was written for me.

All I had to do was be ready.

I rose and laved and robed myself with unusual care, like a knight readying himself for a quest, or a priestess preparing to administer her holiest mystery. Though the face may be hidden by visor or veil, yet those with skill to read will know how to interpret the blazon or the chasuble.

When I was ready I went out to the car. It was still very early. The birds were carolling in full chorus and the eastern sky was mother-of-pearl flushing to pink, like a maiden’s cheek in a Disney movie.

It was far too early to go into town and on impulse I headed out to the countryside. This, I felt, was not a day to ignore impulse.

Half an hour later I was wondering if I hadn’t been just plain silly. The car had been giving me trouble for some time now with the engine coughing and losing power on hills. Each time it happened I promised myself I’d take it into the garage. Then it would seem all right for a while and I’d forget. This time I knew it was really serious when it started hiccoughing on a gentle down-slope, and sure enough on the next climb, which was only the tiny hump of a tiny humpback bridge, it wheezed to a halt.

I got out and kicked the door shut. No use to look under the bonnet. Engines, though Latin, were Greek to me. I sat on the shallow parapet of the bridge and tried to recall how far back it was to a house or telephone. All I could remember was a signpost saying it was five miles to the little village of Little Bruton. It seemed peculiarly unjust somehow that a car that spent most of its time in town should break down in what was probably the least populated stretch of countryside within ten miles of the city boundary.

Sod’s Law, isn’t that what they call it? And that’s what I called it, till gradually to the noise of chirruping birdsong and bubbling water was added a new sound and along that narrow country road I saw approaching a bright yellow Automobile Association van.

Now I began to wonder whether it might not after all be God’s Law.

I flagged him down. He was on his way to a Home Start call in Little Bruton where some poor wage-slave newly woken and with miles to go before he slept had found his motor even more reluctant to start than he was.

‘Engines like a lie-in too,’ said my rescuer merrily.

He was a very merry fellow altogether, full of jest, a marvellous advert for the AA. When he asked if I were a member and I told him I’d lapsed, he grinned and said, ‘Never mind. I’m a lapsed Catholic but I can always join again if things get desperate, can’t I? Same for you. You are thinking of joining again, aren’t you?’

‘Oh yes,’ I said fervently. ‘You get this car started, and I might join the Church too!’

And I meant it. Not about the Church maybe, but certainly the AA.

Yet already, indeed from the moment I set eyes on his van, I’d been wondering if this might not be my chance to get more than just my car started.

But how to be certain? I felt my agitation growing till I stilled it with the comforting thought that, though indefinite to me, the author of my Great Adventure would never let its opening page be anything but clear.

The AA man was a great talker. We exchanged names. When I heard his, I repeated it slowly and he laughed and told me not to make the jokes, he’d heard them all before. But of course I wasn’t thinking of jokes. He told me all about himself – his collection of tropical fish – the talk he’d given about them on local radio – his work for children’s charities – his plan to make money for them by doing a sponsored run in the London marathon – the marvellous holiday he’d just had in Greece – his love of the warm evenings and Mediterranean cuisine – his delight in discovering a new Greek restaurant had just opened in town on his return.

‘Sometimes you think there’s someone up there looking after you special, don’t you?’ he jested. ‘Or maybe in my case, down there!’

I laughed and said I knew exactly what he meant.

And I meant it, in both ways, the conventional idle conversational sort of way, and the deeper, life-shapingly significant sort of way. In fact I felt very strongly that I was existing on two levels. There was a surface level on which I was standing enjoying the morning sunshine as I watched his oily fingers making the expert adjustments which I hoped would get me moving again. And there was another level where I was in touch with the force behind the light, the force which burnt away all fear – a level on which time had ceased to exist, where what was happening has always happened and will always be happening, where like an author I can pause, reflect, adjust, refine, till my words say precisely what I want them to say and show no trace of my passage …

For a moment my AA man stops talking as he makes a final adjustment with the engine running. He listens with the close attention of a piano tuner, smiles, switches off, and says, ‘Reckon that’ll get you to Monte Carlo and back, if that’s your pleasure.’ I say, ‘That’s great. Thank you very much.’ He sits down on the parapet of the bridge and starts putting his tools into his tool box. Finished, he looks up into the sun, sighs a sigh of utter contentment and says, ‘You ever get those moments when you feel, this is it, this is the one I’d like never to end? Needn’t be special, big occasion or anything like that. Just a morning like this, and you feel, I could stay here for ever.’

‘Yes,’ I tell him. ‘I know exactly what you mean.’

‘Would be nice, eh?’ he says wistfully. ‘But no rest for the wicked, I’m afraid.’

And he closes his box and starts to rise.

And now at last beyond all doubt the signal is given.

Down in the willows overhanging the stream on the far side of the bridge something barks, a fox I think, followed by a great squawk of what could have been raucous laughter; then out of the trailing greenery rockets a cock pheasant, wings beating desperately to lever its heavy body over the stonework and into the sky. It clears the far parapet by inches and comes straight at us. I step aside. The AA man steps backwards. The shallow parapet behind him catches his calves. The bird passes between us, I feel the furious beat of its wings like a Pentecostal wind. And the AA man flails his arms as if he too is trying to take off. But he is already unbalanced beyond recovery. I stretch out my hand to the teetering figure – to help or to push, who can tell? – and my fingertips brush against his, like God’s and Adam’s in the Sistine Chapel, or God’s and Lucifer’s on the battlements of heaven.

Then he is gone.

I look over the parapet. He has somersaulted in his fall and landed face down in the shallow stream below. It is only a few inches deep, but he isn’t moving.

I scramble down the steep bank. It’s clear what has happened. He has banged his head against a stone on the stream bed and stunned himself. As I watch, he moves and tries to raise his head out of the water.

Part of me wants to help him, but it is not a part that has any control over my hands or my feet. I have no choice but to stand and watch. Choice is a creature of time and time is away and somewhere else.

Three times his head lifts a little, three times falls back.

There is no fourth.

For a while bubbles rise. Perhaps he is using these last few exhalations to rejoin the Catholic Church. Certainly for him things are never going to be more desperate. On the other hand, he is at last getting his wish for one of those perfect moments to be extended forever, and wherever he finally lies at rest will, I am sure, be a happy grave.

Fast the bubbles come at first, then slower and slower, like the last oozings from a cider press, till up to the surface swims that final languid sac of air which, if the priests are right, ought to contain the soul.

Run well, my marathon messenger!

The bubble bursts.

And time too bursts back into my consciousness with all its impedimenta of mind and matter, rule and law.

I scrambled back up the bank and got into my car. Its engine sang such a merry song as I drove away that I blessed the skilful hands that had tuned it to this pitch. And I gave thanks too for this new, or rather this renewed life of mine.

My journey had begun. No doubt there would be obstacles along my path. But now that path was clearly signed. A journey of a thousand miles must begin with a single step.

And just by standing still and trusting in you, my guide, I had taken that step.

Talk again soon.

CHAPTER TWO (#u776ac008-590a-524d-9fbc-ac6e3a8dfa74)

‘Good lord,’ said Dick Dee.

‘What?’

‘Have you read this one?’

Rye Pomona sighed rather more stentoriously than was necessary and said with heavy sarcasm, ‘As we decided to split them down the middle, and as this is my pile here, and that is your pile there, and as the script in your hand comes from your pile and I am concentrating very hard on trying to get through my own pile, I don’t really think there’s much chance I’ve read it, is there?’

One of the good things about Dick Dee was that he took cheek very well, even from the most junior member of his staff. In fact, there were lots of good things about him. He knew his job as custodian of the Mid-Yorkshire County Library’s Reference Department inside out and was both happy and able to communicate that knowledge. He did his share of work, and though she sometimes saw him working on the lexicological research for what he called his minusculum opusculum., it was always during his official breaks and never spread further, even when things were very quiet. At the same time he showed no sign of exasperation if her lunch hour overflowed a little. He passed no comment on her style of dress and neither averted his eyes prudishly from nor stared salaciously at the length of slim brown leg which emerged from the shallow haven of her mini dress. He had entertained her in his flat without the slightest hint of a pass (she wasn’t altogether sure how she felt about that!). And though on their first encounter, his gaze had taken in her most striking feature, the single lock of silvery grey which shone among the rich brown tresses of her hair, he had been so courteously un-nosey about it that in the end she had got the topic out of the way by introducing it herself.

Nor did he use his seniority to offload all the most tedious jobs on to her but did his share, which would have made him a paragon if in the context of the present tedious job he’d been able to read more than a couple of pages at a time without wanting to share a thought with her. As it was, he grinned so broadly at her putdown that she felt immediately guilty and took the sheets of paper from his hand without further protest.

At least they were typed. Many weren’t and she’d soon made the discovery long known to schoolteachers that even the neatest hand can be as inscrutable as leaves from the Delphic Oracle, with the additional disincentive that when you finally teased some meaning out of it, what you ended up with wasn’t a useful divine pointer to future action but a God-awful dollop of prose fiction.

The Mid-Yorkshire Short Story Competition had been thought up by the editor of the Mid-Yorkshire Gazette and the Head of Mid-Yorkshire Library Services towards the end of a boozy Round Table dinner. Next morning, exposed to the light of day, the idea should have withered and died. Unfortunately, both Mary Agnew of the Gazette and Percy Follows, the Chief Librarian, had misrecollected that the other had undertaken to do most of the work and bear most of the cost. By the time they realized their common error, preliminary notices of the competition were in the public domain. Agnew, who like most veterans of the provincial press was a past mistress of making the best out of bad jobs, had now taken the initiative. She persuaded her proprietor to put up a small financial prize for the winning entry, which would also be published in the paper. And she obtained the services of a celebrity judge in the person of the Hon. Geoffrey Pyke-Strengler, whose main public qualification was that he was a published writer (a collection of sporting reminiscences from a life spent slaughtering fish, fowl and foxes), and whose main private qualification was that being both chronically hard-up and intermittently the Gazette’s rural correspondent, he was in a position of dependency.

Follows was congratulating himself on having come rather well out of this when Agnew added that of course the Hon. (whose reading range didn’t extend beyond the sporting magazines) couldn’t be expected to plough through all the entries, that her team of ace reporters were far too busy writing their own deathless prose to read anyone else’s, and that therefore she was looking to the library services with their acknowledged expertise in the field of prose fiction to sort out the entries and produce a short list.

Percy Follows knew when he’d been tagged and looked for someone on the library staff to tag in turn. All roads led to Dick Dee who, despite having an excellent degree in English, seemed never to have learned how to say no.

The best he could manage by way of demur was, ‘Well, we are rather busy … How many entries are you anticipating?’

‘This sort of thing has a very limited appeal,’ said Follows confidently. ‘I’d be surprised if we get into double figures. Couple of dozen at the very most. You can run through them in your tea break.’

‘That’s a hell of a lot of tea,’ grumbled Rye when the first sackful of scripts was delivered from the Gazette. But Dick Dee had just smiled as he looked at the mountain of paper and said, ‘It’s mute inglorious Milton time, Rye. Let’s start sorting them out.’

The initial sorting out had been fun.

The idea of refusing to read anything not typewritten had seemed very attractive, but rapidly they realized this was too Draconian. On the other hand as more sackloads arrived, they knew they had to have some rules of inadmissibility.

‘Nothing in green ink,’ said Dee.

‘Nothing on less than A5,’ said Rye.

‘Nothing handwritten where the letters aren’t joined up.’

‘Nothing without meaningful punctuation.’

‘Nothing which requires use of a magnifying glass.’

‘Nothing that has organic matter adhering to it,’ said Rye, picking up a sheet which looked as if it had recently lined a cat tray.

Then she’d thought that perhaps the offending stain had come from some baby whose housebound mother was desperately trying to be creative at feeding time, and residual guilt had made her protest strongly when Dick had gone on, ‘And nothing sexually explicit or containing four-letter words.’

He had listened to her liberal arguments with great patience, showing no resentment of her implied accusation that he was at best a frump, at worst a fascist.

When she finished, he said mildly, ‘Rye, I agree with you that there is nothing depraved, disgusting or even distasteful about a good fuck. But as I know beyond doubt that there’s no way any story containing either a description of the act or a derivative of the word is going to get published in the Gazette, it seems to me a useful filter device. Of course, if you want to read every word of every story …’

The arrival of yet another sackful from the Gazette had been a clincher.

A week later, with stories still pouring in and nine days to go before the competition closed, she had become much more dismissive than Dee, spinning scripts across to the dump bin after an opening paragraph, an opening sentence even, or, in some cases, just the title, while he read through nearly all of his and was building a much higher possibles pile.

Now she looked at the script he had interrupted her with and said, ‘First Dialogue? That mean there’s going to be more?’

‘Poetic licence, I expect. Anyway, read it. I’d be interested to hear what you think.’

A new voice interrupted them.

‘Found the new Maupassant yet, Dick?’

Suddenly the light was blocked out as a long lean figure loomed over Rye from behind.

She didn’t need to look up to know this was Charley Penn, one of the reference library’s regulars and the nearest thing Mid-Yorkshire had to a literary lion. He’d written a moderately successful series of what he called historical romances and the critics bodice-rippers, set against the background of revolutionary Europe in the decades leading up to 1848, with a hero loosely based on the German poet Heine. These had been made into a popular TV series where the ripping of bodices was certainly rated higher than either history or even romance. His regular attendance in the reference library had nothing to do with the pursuit of verisimilitude in his fictions. In his cups he had been heard to say of his readers, ‘You can tell the buggers owt. What do they know?’ though in fact he had acquired a wide knowledge of the period in question through the ‘real’ work he’d been researching now for many years, which was a critical edition with metrical translation of Heine’s poems. Rye had been surprised to learn that he was a school contemporary of Dick Dee. The ten years which Dee’s equanimity of temperament erased from his forty-something seemed to have been dumped on Penn, whose hollow cheeks, deep-set eyes and unkempt beard gave him the look of an old Viking who’d ravished and pillaged a raid too far.

‘Probably not,’ said Dee. ‘Be glad of your professional opinion though, Charley.’

Penn moved round the table so that he was looking down at Rye and showed uneven teeth in what she called his smarl, assuming he intended it as a smile and couldn’t help that it came out like a snarl. ‘Not unless you’ve got a sudden budget surplus.’

When it came to professional opinions, or indeed any activity connected with his profession, Charley Penn’s insistence that time equalled money made lawyers seem open-handed.

‘So how can I help you?’ said Dee.

‘Those articles you were tracking down for me, any sign yet?’

Penn had no difficulty squaring his assertion that the labourer was worthy of his hire with using Dee as his unpaid research assistant, but the librarian never complained.

‘I’ll just check to see if there’s anything in today’s post,’ he said.

He rose and went into the office behind the desk.

Penn remained, his gaze fixed on Rye.

She looked back unblinkingly and said, ‘Yes?’

From time to time she’d caught the old Viking looking at her like he was once more feeling the call of the sea, though so far he’d stopped short of rapine and pillage. In fact his preferred model seemed to be that guy in the play (what the hell was his name?) who went around the Forest of Arden, pinning poems to trees. From time to time scraps of Penn’s Heine translations would be put in her way. She’d open a file or pick up a book and there would be a few lines about a despairing lover staring down at himself staring up at his beloved’s window or a lonely northern fir-tree pining for the hand of an unattainably distant palm. Their presence was explained, if explanation were demanded, by inadvertence, accompanied by a knowing version of the smarl which was what she got now as Penn said, ‘Enjoy,’ and went after Dee.

Now Rye gave her full attention to the ‘First Dialogue’, skimming through it rapidly, then reading it again more slowly.

By the time she’d finished, Dee had returned and Penn was back in his usual seat in one of the study alcoves from which he had been known to bellow abuse at young students whose ideas of silence did not accord with his own.

‘What do you think?’ said Dee.

‘Why the hell am I reading this? is what I think,’ said Rye. ‘OK, the writer’s trying to be clever, using a single episode to hint at a whole epic to come, but it doesn’t really work, does it? I mean, what’s it about? Some kind of metaphor of life or what? And what the hell’s that funny illustration all about? I hope you’re not showing me this as the best thing you’ve come across. If so, I don’t want to look at any of the other stuff in your possibles pile.’

He shook his head, smiling. No smarl this. He had a rather nice smile. One of the rather nice things about it was that he used it alike to greet compliment or insult, triumph or disaster. A couple of days earlier for instance a lesser man might have flapped when a badly plugged shelf had collapsed under the weight of the twenty-volume Oxford English Dictionary, scattering a party of civic dignitaries on a tour of the borough’s newly refurbished Heritage, Arts and Library Centre. Only one of the visitors had been hit, receiving the full weight of Volume II on his toe. This was Councillor Cyril Steel, a virulent opponent of the Centre whose voice had frequently been raised in the council against ‘wasting good public money on a load of airy nowt’. Percy Follows had run around like a panicked poodle, fearing a PR disaster, but Dee had merely smiled into the TV camera recording the event for BBC Mid-Yorks and said, ‘Now even Councillor Steel will have to admit that a little learning can be a dangerous thing and not all our nowts are completely airy,’ and continued with his explanatory address.

Now he said, ‘No, I’m not suggesting this as a contender for the prize, though it’s not badly written. As for the drawing, it’s part illustration and part illumination, I think. But what’s really interesting is the way it chimes with something I read in today’s Gazette.’

He picked up a copy of the Mid-Yorkshire Gazette from the newspaper rack. The Gazette came out twice weekly, on Wednesdays and Saturdays. This was the midweek edition. He opened it at the second page, set it before her and indicated a column with his thumb.

AA MAN DIES IN TRAGIC ACCIDENT

The body of Mr Andrew Ainstable (34), a patrol officer with the Automobile Association, was found apparently drowned in a shallow stream running under the Little Bruton road on Tuesday morning. Thomas Killiwick (27), a local farmer who made the discovery, theorized that Mr Ainstable, who it emerged was on his way to a Home Start call at Little Bruton, may have stopped for a call of nature, slipped, and banged his head, but the police are unable to confirm or to deny this theory at this juncture. Mr Ainstable is survived by his wife, Agnes, and a widowed mother. An inquest is expected to be called in the next few days.

‘So what do you think?’ asked Dee again.

‘I think from the style of this report that they were probably wise at the Gazette to ask us to judge the literary merit of these stories,’ said Rye.

‘No. I mean this Dialogue thing. Bit of an odd coincidence, don’t you think?’

‘Not really. I mean, it’s probably not a coincidence at all. Writers must often pick up ideas from what they read in the papers.’

‘But this wasn’t in the Gazette till this morning. And this came out of the bag of entries they sent round last night. So presumably they got it some time yesterday, the same day this poor chap died, and before the writer could have read about it.’

‘OK, so it’s a coincidence after all,’ said Rye irritably. ‘I’ve just read a story about a man who wins the lottery and has a heart attack. I dare say that this week somewhere there’s been a man who won something in the lottery and had a heart attack. It didn’t catch the attention of the Pulitzer Prize mob at the Gazette, but it’s still a coincidence.’

‘All the same,’ said Dee, clearly reluctant to abandon his sense of oddness. ‘Another thing, there’s no pseudonym.’

The rules of entry required that, in the interests of impartial judging, entrants used a pseudonym under their story title. They also wrote these on a sealed envelope containing their real name and address. The envelopes were kept at the Gazette office.

‘So he forgot,’ said Rye. ‘Not that it matters, anyway. It’s not going to win, is it? So who cares who wrote it? Now, can I get on?’

Dick Dee had no argument against this. But Rye noticed he didn’t put the typescript either into the dump bin or on to his possibles pile, but set it aside.

Shaking her head, Rye turned her attention to the next story on her pile. It was called ‘Dreamtime’, written in purple ink in a large spiky hand averaging four words to a line, and it began:

When I woke up this morning I found I’d had a wet dream, and as I lay there trying to recall it, I found myself getting excited again …

With a sigh, she skimmed it over into the dump bin and picked another.

CHAPTER THREE (#u776ac008-590a-524d-9fbc-ac6e3a8dfa74)

‘What the fuck are you playing at, Roote?’ snarled Peter Pascoe.

Snarling wasn’t a form of communication that came easily to him, and attempting to keep his upper teeth bared while emitting the plosive P produced a sound effect which was melodramatically Oriental with little of the concomitant sinisterity. He must pay more attention next time his daughter’s pet dog, which didn’t much like men, snarled at him.

Roote pushed the notebook he’d been scribbling in beneath a copy of the Gazette and regarded him with an expression of amiable bewilderment.

‘Sorry, Mr Pascoe? You’ve lost me. I’m not playing at anything and I don’t think I know the rules of the game you’re playing. Do I need a racket too?’

He smiled towards Pascoe’s sports bag from which protruded the shaft of a squash racket.

Cue for another snarl on the line, Don’t get clever with me, Roote!

This was getting like a bad TV script.

As well as snarling he’d been trying to loom menacingly. He had no way of knowing how menacing his looming looked to the casual observer, but it was playing hell with the strained shoulder muscle which had brought his first game of squash in five years to a premature conclusion. Premature? Thirty seconds into foreplay isn’t premature, it is humiliatingly pre-penetrative.

His opponent had been all concern, administering embrocation in the changing room and lubrication in the University Staff Club bar, with no sign whatsoever of snigger. Nevertheless, Pascoe had felt himself sniggered at and when he made his way through the pleasant formal gardens towards the car park and saw Franny Roote smiling at him from a bench, his carefully suppressed irritation had broken through and before he had time to think rationally he was deep into loom and snarl.

Time to rethink his role.

He made himself relax, sat down on the bench, leaned back, winced, and said, ‘OK, Mr Roote. Let’s start again. Would you mind telling me what you’re doing here?’

‘Lunch break,’ said Roote. He held up a brown paper bag and emptied its contents on to the newspaper. ‘Baguette, salad with mayo, low fat. Apple, Granny Smith. Bottle of water, tap.’

That figured. He didn’t look like a man on a high-energy diet. He was thin just this side of emaciation, a condition exacerbated by his black slacks and T-shirt. His face was white as a piece of honed driftwood and his blond hair was cut so short he might as well have been bald.

‘Mr Roote,’ said Pascoe carefully, ‘you live and work in Sheffield which means that even with a very generous lunch break and a very fast car, this would seem an eccentric choice of luncheon venue. Also this is the third, no I think it’s the fourth time I have spotted you in my vicinity over the past week.’

The first time had been a glimpse in the street as he drove home from Mid-Yorkshire Police HQ early one evening. Then a couple of nights later as he and Ellie rose to leave a cinema, he’d noticed Roote sitting half a dozen rows further back. And the previous Sunday as he took his daughter, Rosie, for a stroll in Charter Park to feed the swans, he was sure he’d spotted the black-clad figure standing on the edge of the unused bandstand.

That’s when he’d made a note to ring Sheffield, but he’d been too busy to do it on Monday and by Tuesday it had seemed too trivial to make a fuss over. But now on Wednesday, like a black bird of ill omen, here was the man once more, this time too close for mere coincidence.

‘Oh gosh, yes, I see. In fact I’ve noticed you a couple of times too, and when I saw you coming out of the Staff Club just now, I thought, Good job you’re not paranoiac, Franny boy, else you might think Chief Inspector Pascoe is stalking you.’

This was a reversal to take the breath away.

Also a warning to proceed with great care.

He said, ‘So, coincidence for both of us. Difference is, of course, I live and work here.’

‘Me too,’ said Roote. ‘Don’t mind if I start, do you? Only get an hour.’

He bit deep into the baguette. His teeth were perfectly, almost artistically, regular and had the kind of brilliant whiteness which you expected to see reflecting the flash-bulbs at a Hollywood opening. Prison service dentistry must have come on apace in the past few years.

‘You live and work here?’ said Pascoe. ‘Since when?’

Roote chewed and swallowed.

‘Couple of weeks,’ he said.

‘And why?’

Roote smiled. The teeth again. He’d been a very beautiful boy.

‘Well, I suppose it’s really down to you, Mr Pascoe. Yes, you could say you’re the reason I came back.’

An admission? Even a confession? No, not with Franny Roote, the great controller. Even when you changed the script in mid-scene, you still felt he was still in charge of direction.

‘What’s that mean?’ asked Pascoe.

‘Well, you know, after that little misunderstanding in Sheffield, I lost my job at the hospital. No, please, don’t think I’m blaming you, Mr Pascoe. You were only doing your job, and it was my own choice to slit my wrists. But the hospital people seemed to think it showed I was sick, and of course, sick people are the last people you want in a hospital. Unless they’re on their backs, of course. So soon as I was discharged, I was … discharged.’

‘I’m sorry,’ said Pascoe.

‘No, please, like I say, not your responsibility. In any case, I could have fought it, the staff association were ready to take up the cudgels and all my friends were very supportive. Yes, I’m sure a tribunal would have found in my favour. But it felt like time to move on. I didn’t get religion inside, Mr Pascoe, not in the formal sense, but I certainly came to see that there is a time for all things under the sun and a man is foolish to ignore the signs. So don’t worry yourself.’

He’s offering me absolution! thought Pascoe. One moment I’m snarling and looming, next I’m on my knees being absolved!

He said, ‘That still doesn’t explain …’

‘Why I’m here?’ Roote took another bite, chewed, swallowed. ‘I’m working for the university gardens department. Bit of a change, I know. Very welcome, though. Hospital portering’s a worthwhile job, but you’re inside most of the time, and working with dead people a lot of the time. Now I’m outdoors, and everything’s alive! Even with autumn coming on, there’s still so much of life and growth around. OK, there’s winter to look forward to, but that’s not the end of things, is it? Just a lying dormant, conserving energy, waiting for the signal to re-emerge and blossom again. Bit like prison, if that’s not too fanciful.’

I’m being jerked around here, thought Pascoe. Time to crack the whip.

‘The world’s full of gardens,’ he said coldly. ‘Why this one? Why have you come back to Mid-Yorkshire?’

‘Oh, I’m sorry, I should have said. That’s my other job, my real work – my thesis. You know about my thesis? Revenge and Retribution in English Drama? Of course you do. It was that which helped set you off in the wrong direction, wasn’t it? I can see how it would, with Mrs Pascoe being threatened and all. You got that sorted, did you? I never read anything in the papers.’

He paused and looked enquiringly at Pascoe who said, ‘Yes, we got it sorted. No, there wasn’t much in the papers.’

Because there’d been a security cover-up, but Pascoe wasn’t about to go into that. Irritated though he was by Roote, and deeply suspicious of his motives, he still felt guilty at the memory of what had happened. With Ellie being threatened from an unknown source, he’d cast around for likely suspects. Discovering that Roote, whom he’d put away as an accessory to murder some years ago, was now out and writing a thesis on revenge in Sheffield where he was working as a hospital porter, he’d got South Yorkshire to shake him up a bit then gone down himself to have a friendly word. On arrival, he’d found Roote in the bath with his wrists slashed, and when later he’d had to admit that Roote had no involvement whatsoever in the case he was investigating, the probation service had not been slow to cry harassment.

Well, he’d been able to show he’d gone by the book. Just. But he’d felt then the same mixture of guilt and anger he was feeling now.

Roote was talking again.

‘Anyway, my supervisor at Sheffield got a new post at the university here, just started this term. He’s the one who helped me get fixed up with the gardening job, in fact, so you see how it all slotted in. I could have got a new supervisor, I suppose, but I’ve just got to the most interesting part of my thesis. I mean, the Elizabethans and Jacobeans have been fascinating, of course, but they’ve been so much pawed over by the scholars, it’s difficult to come up with much that’s really new. But now I’m on to the Romantics: Byron, Shelley, Coleridge, even Wordsworth, they all tried their hands at drama you know. But it’s Beddoes that really fascinates me. Do you know his play Death’s Jest-Book?’

‘No,’ said Pascoe. ‘Should I?’

In fact, it came to him as he spoke that he had heard the name Beddoes recently.

‘Depends what you mean by should. Deserves to be better known. It’s fantastic. And as my supervisor’s writing a book on Beddoes and probably knows more about him than any man living, I just had to stick with him. But it’s a long way to travel from Sheffield even with a decent car, and the only thing I’ve been able to afford has more breakdowns than an inner-city teaching staff! It really made sense for me to move too. So everything’s turned out for the best in the best of all possible worlds!’

‘This supervisor,’ said Pascoe, ‘what’s his name?’

He didn’t need to ask. He’d recalled where he’d heard Beddoes’ name mentioned, and he knew the answer already.

‘He’s got the perfect name for an Eng. Lit. teacher,’ said Roote, laughing. ‘Johnson. Dr Sam Johnson. Do you know him?’

‘That’s when I made an excuse and left,’ said Pascoe.

‘Oh aye? Why was that?’ said Detective Superintendent Andrew Dalziel. ‘Fucking useless thing!’

It was, Pascoe hoped, the VCR squeaking under the assault of his pistonlike finger that Dalziel was addressing, not himself.

‘Because it was Sam Johnson I’d just been playing squash with,’ he said, rubbing his shoulder. ‘It seemed like Roote was taking the piss and I felt like taking a swing, so I went straight back inside and caught Sam.’

‘And?’

And Johnson had confirmed every word.

It turned out the lecturer knew his student’s background without knowing the details. Pascoe’s involvement in the case had come as a surprise to him but, once filled in, he’d cut right to the chase and said, ‘If you think that Fran’s got any ulterior motive in coming back here, forget it. Unless he’s got so much influence he arranged for me to get a job here, it’s all happenstance. I moved, he didn’t fancy travelling for supervision and the job he had in Sheffield came to an end, so it made sense for him to make a change too. I’m glad he did. He’s a really bright student.’

Johnson had been out of the country during the long vacation and so missed the saga of Roote’s apparent suicide attempt, and the young man clearly hadn’t bellyached to him about police harassment in general and Pascoe harassment in particular, which ought to have been a point in his favour.

The lecturer concluded by saying, ‘So I got him the gardening job, which is why he’s out there in the garden, and he lives in town, which is why you see him around town. It’s coincidence that makes the world go round, Peter. Ask Shakespeare.’

‘This Johnson,’ said Dalziel, ‘how come you’re so chummy you take showers together? He fag for you at Eton or summat?’

Dalziel affected to believe that the academic world which had given Pascoe his degree occupied a single site somewhere in the south where Oxford and Cambridge and all the major public schools huddled together under one roof.

In fact it wasn’t Pascoe’s but his wife’s links with the academic and literary worlds which had brought Johnson into their lives. Part of Johnson’s job brief at MYU was to help establish an embryonic creative writing course. His qualification was that he’d published a couple of slim volumes of poetry and helped run such a course at Sheffield. Charley Penn, who made occasional contributions to both German and English Department courses, had been miffed to find his own expression of interest ignored. He ran a local authority literary group in danger of being axed and clearly felt that the creative writing post at MYU would have been an acceptable palliative for the loss of his LEA honorarium. Colleagues belonging to that breed not uncommon in academia, the greater green-eyed pot-stirrer, had advised Johnson to watch his back as Penn made a bad enemy, at a physical as well as a verbal level. A few years earlier, according to university legend, a brash young female journalist had done a piss-taking review of the Penn oeuvre in Yorkshire Life, the county’s glossiest mag. The piece had concluded, ‘They say the pen is mightier than the sword, but if you have a sweet tooth and a strong stomach, the best implement to deal with our Mr Penn’s frothy confections might be a pudding spoon.’ The following day Penn, lunching liquidly in a Leeds restaurant, had spotted the journalist across a crowded dessert trolley. Selecting a large portion of strawberry gateau liberally coated with whipped cream, he had approached her table, said, ‘This, madam, is a frothy confection,’ and squashed the pudding on to her head. In court he had said, ‘It wasn’t personal. I did it not because of what she said about my books but because of her appalling style. English must be kept up,’ before being fined fifty pounds and bound over to keep the peace.

Sam Johnson had immediately sought out Penn and said, ‘I believe you know more about Heine than anyone else in Yorkshire.’

‘That wouldn’t be hard. They say you know more about Beddoes than anyone in The Dog and Duck at closing time.’

‘I know he went to Göttingen University to study medicine in 1824 and Heine was there studying law.’

‘Oh aye? And Hitler and Wittgenstein were in the same class at school. So what?’

‘So why don’t we flaunt our knowledge in The Dog and Duck one night?’

‘Well, it’s quiz night tonight. You never know. It might come up.’

Thus had armistice been signed before hostilities proper began. When talk finally turned to the writing course, Penn, after token haggling, accepted terms for making the occasional ‘old pro’ appearance, and went on to suggest that if Johnson was interested in a contribution from someone at the other end of the ladder, he might do worse than soon-to-be-published novelist Ellie Pascoe, an old acquaintance from her days on the university staff and a member of the threatened literary group.

This version of that first encounter was cobbled together from the slightly different accounts Ellie received from both participants. She and Johnson had hit it off straightaway. When she invited him home for a meal, the conversation had naturally centred on matters literary, and Pascoe, feeling rather sidelined, had leapt into the breach when Johnson had casually mentioned his difficulty in finding a squash partner among his generally unathletic colleagues.

His reward for this friendly gesture when Johnson finally left, late, in a taxi, had been for Ellie to say, ‘This game of squash, Peter, you will be careful.’

Indignantly Pascoe said, ‘I’m not quite decrepit, you know.’

‘I’m not talking about you. I meant, with Sam. He’s got a heart problem.’

‘As well as a drink problem? Jesus!’

In the event it had turned out that Johnson suffered from a mild drug-controllable tachycardia, but Pascoe wasn’t looking forward to describing to his wife the rapid and undignified conclusion of his game with someone he’d categorized as an alcoholic invalid.

‘Mate of Elbe’s, eh?’ said Dalziel with a slight intake of breath and a sharp shake of the VCR which, with greater economy than a Special Branch file, consigned Johnson to the category of radical, subversive, Trotskyite troublemaker.

‘Acquaintance,’ said Pascoe. ‘Do you want a hand with that, sir?’

‘No. I reckon I can throw it out of the window myself. You’re very quiet, mastermind. What do you reckon?’

Sergeant Edgar Wield was standing before the deep sash-window. Silhouetted against the golden autumn sunlight, his face deep shadowed, he had the grace and proportions to model for the statue of a Greek athlete, thought Pascoe. Then he moved forward and his features took on detail, and you remembered that if this were a statue, it was one whose face someone had taken a hammer to.

‘I reckon you need to look at the whole picture,’ he said. ‘Way back when Roote were a student at Holm Coultram College before it became part of the university, he got sent down as an accessory to two murders, mainly on your evidence. From the dock he says he looks forward to the chance of meeting you somewhere quiet one day and carrying on your interrupted conversation. As the last time you saw him alone he was trying to stove your head in with a rock, you take this as a threat. But we all get threatened at least once a week. It’s part of the job.’

Dalziel, studying the machine like a Sumo wrestler working out a new strategy, growled, ‘Get a move on, Frankenstein, else I’ll start to wish I hadn’t plugged you in.’

Undeterred, Wield proceeded at a measured pace.

‘Model prisoner, Open University degree, Roote gets maximum remission, comes out, gets job as a hospital porter, starts writing an academic thesis, obeys all the rules. Then you get upset by them threats to Ellie and naturally Roote’s one of the folk you need to take a closer look at. Only when you go to see him, you find he’s slashed his wrists.’

‘He knew I was coming,’ said Pascoe. ‘It was a set-up. No real danger to him. Just a perverted joke.’

‘Maybe. Not the way it looked when it turned out Roote had absolutely nothing to do with the threats to Ellie,’ said Wield. ‘He recovers, and a few months later he moves here because (a) his supervisor has moved here and (b) he can get work here. You say you checked with the probation service?’

‘Yes,’ said Pascoe. ‘All done by the book. They wanted to know if there was a problem.’

‘What did you tell the buggers?’ said Dalziel, who classed probation officers with Scottish midges, vegetarians and modern technology as Jobian tests of a virtuous man’s patience.

‘I said no, just routine.’

‘Wise move,’ approved Wield. ‘See how it looks. Man serves his time, puts his life back together, gets harassed without cause by insensitive police officer, flips, tries to harm himself, recovers, gets back on track, finds work again, minds his own business, then this same officer starts accusing him of being some sort of stalker. It’s you who comes out looking like either a neurotic headcase or a vengeful bastard. While Roote … just a guy who’s paid his debt and wants nothing except to live a quiet life. I mean, he didn’t even want the hassle of bringing a harassment case against you, or a wrongful dismissal case against the Sheffield hospital.’

He moved from the window to the desk.

‘Aye,’ said Dalziel thoughtfully. ‘That’s the most worrying thing, him not wanting to kick up a fuss. Well, lad, it’s up to you. But me, I know what I’d do.’

‘And what’s that, sir?’ enquired Pascoe.

‘Break both his legs and run him out of town.’

‘I think perhaps the other way round might be better,’ said Pascoe judiciously.

‘You reckon? Either way, you can stick this useless thing up his arse first.’

He glowered at the VCR which, as if in response to that fearsome gaze, clicked into life and a picture blossomed on the TV screen.

‘There,’ said the Fat Man triumphantly. ‘Told you no lump of tin and wires could get the better of me.’

Pascoe glanced at Wield who was quietly replacing the remote control unit on the desk, and grinned.

An announcer was saying, ‘And now Out and About, your regional magazine programme from BBC Mid-Yorkshire, presented by Jax Ripley.’

Titles over an aerial panorama of town and countryside accompanied by the first few bars of ‘On Ilkla Moor Baht ’at’ played by a brass band, all fading to the slight, almost childish figure of a young blonde with bright blue eyes and a wide mouth stretched in a smile through which white teeth gleamed like a scimitar blade.

‘Hi,’ she said. ‘Lots of goodies tonight, but first, are we getting the policing we deserve, the policing we pay for? Here’s how it looks from the dirty end of the stick.’

A rapid montage of burgled houses and householders all expressing, some angrily, some tearfully, their sense of being abandoned by the police. Back to the blonde, who recited a list of statistics which she then précis’d: ‘So four out of ten cases don’t get looked at by CID in the first twenty-four hours, six out of ten cases get only one visit and the rest is silence, and eight out of ten cases remain permanently unsolved. In fact, as of last month there were more than two hundred unsolved current cases on Mid-Yorkshire CID’s books. Inefficiency? Underfunding? Understaffing? Certainly we are told that the decision not to replace a senior CID officer who comes up to retirement shortly is causing much soul searching, or, to put it another way, a bloody great row. But when we invited Mid-Yorkshire Constabulary to send someone along to discuss these matters, a spokesman said they were unable to comment at this time. Maybe that means they are all too busy dealing with the crime wave. I would like to think so. But we do have Councillor Cyril Steel, who has long been interested in police matters. Councillor Steel, I gather you feel we are not getting the service we pay for?’

A bald-headed man with mad eyes opened his mouth to show brown and battlemented teeth, but before he could let fly his arrows of criticism, the screen went dark as Dalziel ripped the plug out of the wall socket.

‘Too early in the day to put up with Stuffer,’ he said with a shudder.

‘We must be able to take honest criticism, sir,’ said Pascoe solemnly. ‘Even from Councillor Steel.’

He was being deliberately provocative. Steel, once a Labour councillor but now an Independent after the Party ejected him in face of his increasingly violent attacks on the leadership, hurling charges which ranged from cronyism to corruption, was the self-appointed leader of a crusade against the misuse of public money. His targets included everything from the building of the Heritage, Arts and Library Centre to the provision of digestive biscuits at council committee meetings, so it was hardly surprising that he should have rushed forward to lend his weight to Jax Ripley’s investigation into the way police resources were managed in Mid-Yorkshire.

‘Not his criticism that bothers me,’ growled Dalziel. ‘Have you ever got near him? Teeth you could grow moss on and breath like a vegan’s fart. I can smell it through the telly. Only time Stuffer’s not talking is when he’s eating, and not always then. No one listens any more. No, it’s Jax the bloody Ripper who bothers me. She’s got last month’s statistics, she knows about the decision not to replace George Headingley and, looking at the state of some of them burgled houses, she must have been round there with her little camera afore we were!’

‘So you still reckon someone’s talking?’ said Pascoe.

‘It’s obvious. How many times in the last few months has she been one jump ahead of us? Past six months, to be precise. I checked back.’

‘Six months? And you think that might be significant? Apart from the fact, of course, that Miss Ripley started doing the programme only seven months ago?’

‘Aye, it could be significant,’ said Dalziel grimly.

‘Maybe she’s just good at her job,’ said Pascoe. ‘And surely it’s no bad thing for the world to know we’re not getting a replacement DI for George? Perhaps we should use her instead of getting our knickers in a twist.’

‘You don’t use a rat,’ said Dalziel. ‘You block up the hole it’s feeding through. And I’ve got a bloody good idea where to find this hole.’

Pascoe and Wield exchanged glances. They knew where the Fat Man’s suspicions lay, knew the significance he put on the period of six months. This was just about the length of time Mid-Yorkshire CID’s newest recruit, Detective Constable Bowler, had been on the team. Bowler – known to his friends as Hat and to his arch-foe as Boiler, Boghead, Bowels or any other pejorative variation which occurred to him – had started with the heavy handicap of being a fast-track graduate, on transfer from the Midlands without Dalziel’s opinion being sought or his approval solicited. The Fat Man was Argos-eyed in Mid-Yorkshire and a report that the new DC had been spotted having a drink with Jacqueline Ripley not long after his arrival had been filed away till the first of the items which had seen her re-christened Jax the Ripper had appeared. Since then Bowler had been given the status of man-most-likely, but nothing had yet been proved, which, to Pascoe at least, knowing how close a surveillance was being kept, suggested he was innocent.

But he knew better than to oppose a Dalzielesque obsession. Also, the Fat Man had a habit of being right.

He said brightly, ‘Well, I suppose we’d better go and solve some crimes in case there’s a hidden camera watching us. Thank you both for your input on my little problem.’

‘What? Oh, that,’ said Dalziel dismissively. ‘Seems to me the only problem you’ve got is knowing whether you’ve really got a problem.’

‘Oh yes, I’m certain of that. I think I’ve got the same problem Hector was faced with last year.’

‘Eh?’ said Dalziel, puzzled by this reference to Mid-Yorkshire’s most famously incompetent constable. ‘Remind me.’

‘Don’t you remember? He went into that warehouse to investigate a possible intruder. There was a guard dog, big Ridgeback I think, lying down just inside the doorway.’

‘Oh yes, I recall. Hector had to pass it. And he didn’t know if it was dead, drugged, sleeping or just playing doggo, waiting to pounce, that was his problem, right?’

‘No,’ said Pascoe. ‘He gave it a kick to find out. And it opened its eyes. That was his problem.’

CHAPTER FOUR (#u776ac008-590a-524d-9fbc-ac6e3a8dfa74)

the second dialogue (#u776ac008-590a-524d-9fbc-ac6e3a8dfa74)

Hi.

It’s me again. How’s it going?

Remember our riddles? Here’s a new one.

One for the living, one for the dead, Out on the moor I wind about Nor rhyme nor reason in my head Yet reasons I have without a doubt.

Deep printed on the yielding land Each zig and zag makes perfect sense To those who recognize the hand Of nature’s clerk experience.

This tracks a chasm deep and wide, That skirts a bog, this finds a ford, And men have suffered, men have died, To learn this wisdom of my Word –

– That seeming right is sometimes wrong And even on the clearest days The shortest way may still be long, The straightest line may form a maze.

What am I?

Got it yet?

You were always a smart dog at a riddle!

I’ve been thinking a lot about paths lately, the paths of the living, the paths of the dead, how maybe there’s only one path, and I have set my foot upon it.

I was pretty busy for a few days after my Great Adventure began, so I had little chance to mark its beginning by any kind of celebration. But as the weekend approached, I felt an urge to do something different, a little special. And I recalled my cheerful AA man telling me how chuffed he’d been on his return from Corfu to discover that a new Greek restaurant had just opened in town.

‘In Cradle Street, the Taverna,’ he said. ‘Good nosh and there’s a courtyard out back where they’ve got tables and parasols. Of course, it’s not like sitting outside in Corfu, but on a fine evening with the sun shining and the waiters running around in costume, and this chap twanging away on one of them Greek banjos, you can close your eyes and imagine you’re back in the Med.’

It was really nice to hear someone being so enthusiastic about foreign travel and food and everything. Most Brits tend to go abroad just for the sake of confirming their superiority to everyone else in the world.

Down there too?

There’s no changing human nature.

Anyway, I thought I’d give the Taverna a try.

The food wasn’t bad and the wine was OK, though I abandoned my experiment with retsina after a single glass. It was just a little chilly at first, sitting outside in the courtyard under the artificial olive trees, but the food soon warmed me up, and with the table candles lit, the setting looked really picturesque. Inside the restaurant a young man was singing to his own accompaniment. I couldn’t see the instrument but it gave a very authentic Greek sound and his playing was rather better than his voice. Eventually he came out into the courtyard and started a tour of the tables, serenading the diners. Some people made requests, most of them for British or at best Italian songs, but he tried to oblige everyone. As he reached my table, the PA system suddenly burst into life and a voice said, ‘It’s Zorba time!’ and two of the waiters started doing that awful Greek dancing. I saw the young musician wince, then he caught my eye and grinned sheepishly.

I smiled back and pointed to his instrument, and asked him what its name was, interested to hear if his speaking voice was as ‘Greek’ as his singing voice. It was a bazouki, he said in a broad Mid-Yorkshire accent. ‘Oh, you aren’t Greek then?’ I said, sounding disappointed to conceal the surge of exultation I was feeling. He laughed and admitted quite freely he was local, born, bred and still living out at Carker. He was a music student at the university, finding it impossible like so many of them to exist on the pittance they call a grant these days and plumping it out a bit by working in the Taverna most evenings. But while he wasn’t Greek, his instrument he assured me certainly was, a genuine bazouki brought home from Crete by his grandfather who’d fought there during the Second World War, so its music had first been heard beneath real olive trees in a warm and richly perfumed Mediterranean night.

I could detect in his voice a longing for that distant reality he described just as I’d seen in his face a disgust with this fakery he was involved in. Yorkshire born and bred he might be, but his soul yearned for something that he had persuaded himself could still be found under other less chilly skies. Poor boy. He had the open hopeful look of one born to be disappointed. I yearned to save him from the shattering of his illusions.

The canned music was growing louder and the dancing waiters who’d been urging more and more customers to join their line were getting close to my table, so I tucked some coins into the leather pouch dangling from the boy’s tunic, paid my bill and left.

It was after midnight when the restaurant closed but I didn’t mind sitting in my car, waiting. There is a pleasure in observing and not being observed, in standing in the shadows watching the creatures of the night going about their business. I saw several cats pad purposefully down the alleyway alongside the Taverna where they kept their rubbish bins. An owl floated between the chimneys, remote and silent as a satellite. And I glimpsed what I’m sure was the bushy tail of an urban fox frisking round the corner of a house. But it was the human creatures I was most interested in, the last diners striding, staggering, drifting, driving off into the night, little patches of Stimmungsbild – voices calling, footsteps echoing, car doors banging, engines revving – which played for a moment against the great symphony of the night, then faded away, leaving its dark music untouched.

Then comes a long pause – not in time but of time – how long I don’t know for clocks are blank-faced now – till finally I hear a motorbike revving up in the alleyway and my boy appears at its mouth, a musician making his entry into the music of the night. I know it’s him despite the shielding helmet – would have known without the evidence of the bazouki case strapped behind him.

He pauses to check the road is empty. Then he pulls out and rides away.

I follow. It’s easy to keep in touch. He stays well this side of the speed limit, probably knowing from experience how ready the police are to hassle young bikers, especially late at night. Once it becomes clear he’s heading straight home to Carker, I overtake and pull away.

I have no plan but I know from the merriment bubbling up inside me that a plan exists, and when I pass the derestriction sign at the edge of town and find myself on the old Roman Way, that gently undulating road which runs arrow-straight down an avenue of beeches all the five miles south to Carker, I understand what I have to do.

I leave the lights of town behind me and accelerate away. After a couple of miles, I do a U-turn on the empty road, pull on to the verge, and switch off my lights but not my engine.

Darkness laps over me like black water. I don’t mind. I am its denizen. This is my proper domain.

Now I see him. First a glow, then an effulgence, hurtling towards me. What young man, even one conditioned to carefulness by police persecution, could resist the temptation of such a stretch of road so clearly empty of traffic?

Ah, the rush of the wind in his face, the throb of the engine between his thighs, and in the corners of his vision the blur of trees lined up like an audience of old gods to applaud his passage!

I feel his joy, share in his mirth. Indeed, I’m so full of it I almost miss my cue.

But the old gods are talking to me also, and with no conscious command from my mind, my foot stamps down on the accelerator and my hand flicks on full headlights.

For a fraction of a second we are heading straight for each other. Then his muscles like mine obey commands too quick for his mind, and he swerves, skids, wrestles for control.

For a second I think he has it.

I am disappointed and relieved.

All right, I know, but I have to be honest. What a weight – and a wait – it would be off my soul if this turned out not to be my path after all.

But now the boy begins to feel it go. Yet still, even at this moment of ultimate danger, his heart must be singing with the thrill, the thrust, of it. Then the bike slides away from under him, they part company, and man and machine hurtle along the road in parallel, close but no longer touching.

I come to a halt and turn my head to watch. In time it takes probably a few seconds. In my no-time I can register every detail. I see that it is the bike which hits a tree first, disintegrating in a burst of flame, not much – his tank must have been low – but enough to throw a brief lurid light on his last moment.

He hits a broad-boled beech tree, seems to embrace it with his whole body, wrapping himself around it as if he longs to penetrate its smooth bark and flow into its rising sap. Then he slides off it and lies across its roots, like a root himself, face up, completely still.

I reverse back to him and get out of the car. The impact has shattered his visor but, wonderfully, done no damage to his gentle brown eyes. I notice that his bazouki case has been ripped off the pillion of the bike and lies quite close. The case itself has burst open but the instrument looks hardly damaged. I take it out and lay it close to his outstretched hand.

Now the musician is part of the night’s dark music and I am out of place here. I drive slowly away, leaving him there with the trees and the foxes and owls, his eyes wide open, and seeing very soon, I hope, not the cold stars of our English night but the rich warm blue of a Mediterranean sky.

That’s where he’d rather be. I know it. Ask him. I know it.

I’m too exhausted to talk any more now.

Soon.

CHAPTER FIVE (#ulink_b09d9f24-dc5f-56d0-8ed6-5661e0c83491)

On Thursday morning with only one day to go before the short story competition closed, Rye Pomona was beginning to hope there might be life after deathless prose.

This didn’t stop her shovelling scripts into the reject bin with wild abandon, but halfway through the morning she went very still, sighed perplexedly, re-read the pages in front of her and said, ‘Oh hell.’

‘Yes?’ said Dick Dee.

‘We’ve got a Second Dialogue.’

‘Let me see.’

He read through it quickly then said, ‘Oh dear. I wonder if this one too is related to a real incident.’

‘It is. That’s what hit me straight off. I noticed it in yesterday’s Gazette. Here, take a look.’

She went to the Journal Rack and picked up the Gazette.

‘Here it is. “Police have released details of the fatal accident on Roman Way reported in our weekend edition. David Pitman, 19, a music student, of Pool Terrace, Carker, was returning home from his part-time job as an entertainer at the Taverna Restaurant in Cradle Street when he came off his motorbike in the early hours of Saturday morning. He sustained multiple injuries and was pronounced dead on arrival at hospital. No other vehicle was involved.” Poor sod.’

Dee looked at the paragraph then read the Dialogue again.

‘How very macabre,’ he said. ‘Still, it’s not without some nice touches. If only our friend would attempt a more conventional story, he might do quite well.’

‘That’s all you think it is, then?’ said Rye rather aggressively. ‘Some plonker using news stories to fantasize upon?’

Dee raised his eyebrows high and smiled at her.

‘We seem to have swapped lines,’ he said. ‘Last week it was me feeling uneasy and you pouring cold water. What’s changed?’

‘I could ask the same.’

‘Well, let me see,’ he said with that judicious solemnity she sometimes found irritating. ‘It could be I set my fanciful suspicions alongside the cool rational response of my smart young assistant and realized I was making a real ass of myself.’

Then his face split in a decade-dumping grin and he added, ‘Or some such tosh. And you?’

She responded to the grin, then said, ‘There’s something else I noticed in the Gazette. Hold on … here it is. It says that AA man’s inquest was adjourned to allow the police to make further enquiries. That can only mean they’re treating it as a suspicious death, can’t it?’

‘Yes, but there’s suspicious and suspicious,’ said Dee. ‘Any sudden death has to be thoroughly investigated. If it’s an accident, the causes have to be established to see whether there’s any question of neglect. But even if there’s a suspicion of criminality, for something like this to have any significance …’

He held up the Dialogue and paused expectantly.

A test, she thought. Dick Dee liked to give tests. At first when she came new to the job she’d felt herself patronized, then come to realize it was part of his teaching technique and much to be preferred either to being told something she already knew or not being told something she didn’t.

‘It doesn’t really signify anything,’ she said. ‘Not if the guy’s just feeding off news items. To be significant, or even to strain coincidence, he’d have to be writing before the event.’

‘Before the reporting of the event,’ corrected Dee.

She nodded. It was a small distinction but not nit-picking. That was another of Dee’s qualities. The details he was fussy about were usually important rather than just ego-exercising.

‘What about all this stuff about the student’s grandfather and the bazouki?’ she asked. ‘None of that’s in the paper.’

‘No. But if it’s true, which we don’t know, all it might mean is that the story-teller did have a chat with David Pitman at some time. I dare say it’s a story the young man told any number of customers at the restaurant.’

‘And if it turns out the AA man had been on holiday in Corfu?’

‘I can devise possible explanations till the cows come home,’ he said dismissively. ‘But where’s the point? The key question is, when did this last Dialogue actually turn up at the Gazette? I doubt if they’re systematic enough to be able to pinpoint it, but someone might remember something. Why don’t I have a word while you …’

‘… get on with reading these sodding stories,’ interrupted Rye. ‘Well, you’re the boss.’

‘So I am. And what I was going to say was, while you might do worse than have a friendly word with your ornithological admirer.’

He glanced towards the desk where a slim young man with an open boyish face and a sharp black suit was standing patiently.

His name was Bowler, initial E. Rye knew this because he’d flashed his library card the first time he appeared at the desk to ask for assistance in operating the CD-ROM drive of one of the Reference PCs. Both she and Dee had been on duty, but Rye had discovered early on that in matters of IT, she was the department’s designated expert. Not that her boss wasn’t technologically competent – in fact she suspected he was much more clued up than herself – but when she felt she knew him well enough to probe, he had smiled that sweetly sad smile of his and pointed to the computer, saying, ‘That is the grey squirrel,’ then to the booklined shelves: ‘These are the red.’

The disc Bowler E. wanted to use turned out to be an ornithological encyclopaedia, and when Rye had expressed a polite interest, he’d assumed she was a fellow enthusiast and nothing she’d been able to say during three or four subsequent visits had managed to disabuse him.

‘Oh God,’ she said now. ‘Today I tell him the only way I want to see birds is nicely browned and covered with orange sauce.’

‘You disappoint me, Rye,’ said Dee. ‘I wondered from the start why such a smart young fellow should make himself out to be a mere tyro in computer technology. It’s clearly not just birds that obsess him but you. Express your lack of enthusiasm in the brutal terms you suggest and all he’ll do is seek another topic of common interest. Which indeed you yourself may now be able to suggest.’

‘Sorry?’

‘Mr Bowler is in fact Detective Constable Bowler of the Mid-Yorkshire CID, so well worth cultivating. It’s not every day us amateur detectives get a chance of planting a snout in the local constabulary. I’ll leave him to your tender care, shall I?’

He headed for the office. Clever old Dick, thought Rye, watching him go. While I’m being a smart-ass, he’s busy being smart.

Bowler was coming towards her. She looked at him with new interest. She knew it was one of her failings to make snap judgments from which she was hard to budge. Even now, she was thinking that him being a cop and possibly motivated in his visits to the library by pure lust didn’t stop him being a bird nerd.

The suit and tie-less shirt were hopeful. Not Armani but pretty good clones. And the shy little-boy-lost smile seemed to her newly skinned eye to have something just a tad calculating in it which she approved too. The way to her heart wasn’t through her motherly instincts, but it was nice to see a guy trying.

‘Hello,’ he said hesitantly. ‘Sorry to bother you … if you’re too busy …’

It would have been entertaining to play along for a while but she really was up to her eyes in work even without this short story crap.

She said briskly, ‘Yes, I’m pretty well snowed under. But if it’s just a quickie you’re after, Constable …’

The shy smile remained fixed but he blinked twice, the second one removing all traces of shyness from his eyes (which were a rather nice dove-grey) and replacing it with something very definitely like calculation.

He’s wondering whether I’ve just invited him to swing straight from boy-next-door into saloon-bar-innuendo mode. If he does, he’s on his way. Bird nerd was bad, coarse cop was worse.

He said, ‘No, look, I’m sorry, I just wanted to ask, this Sunday I was thinking about driving out to Stangdale – it’s great country for birds even this time of year, you know, the moor, the crags and of course the tarn …’

He could see he wasn’t gripping her and he changed tack with an ease she approved.

‘… and afterwards I thought maybe we could stop off for a meal …’

‘This Sunday … I’m not sure what I’ve got on …’ she said screwing up her face as if trying to work out what she was doing seventy-two weeks rather than seventy-two hours ahead. ‘And a meal, you said …?’

‘Yeah, there’s the Dun Fox this end of the moor road. Not bad nosh. And now the law’s changed, they’ve starting having discos on Sunday nights as well as Saturdays …’

She knew it. An old-fashioned road-house on the edge of town, it had recently decided to target the local twenty-somethings who wanted to swing without being ankle-deep in teenies. It wasn’t Stringfellows but it was certainly a lot better than a twitchers’ barn dance. Question was, did she want a date with DC Bowler, E?