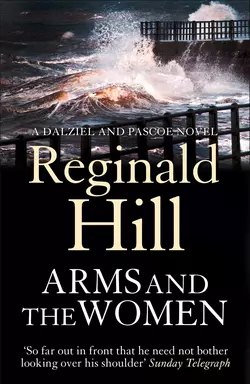

Arms and the Women

Reginald Hill

‘Luminously written, thrilling, unexpectedly erudite, and beautifully structured’ Geoffrey Wansell, Daily MailWhen Ellie Pascoe finds herself under threat, her husband DCI Peter Pascoe and Superintendent Andy Dalziel assume it’s because she’s married to a cop.While they hunt down the source of the danger, Ellie heads out of town in search of a haven… only to get tangled up in a conspiracy involving Irish arms, Colombian drugs and men who will stop at nothing to achieve their ends.Dalziel eventually concludes the security services are involved, but by then it is too late. Ellie’s on her own – and must dig deep down into her reserves to survive…

REGINALD HILL

ARMS AND THE WOMEN

A Dalziel and Pascoe novel

Copyright (#ulink_62262ab0-e763-558b-9777-3a07454d1c9e)

Harper An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2000

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Copyright © Reginald Hill 2000

Extract from ‘Marina’ from the Collected Poems 1909–62 by T.S. Eliot (published by Faber and Faber Ltd) Reproduced by permission of Faber and Faber Ltd

Lines from ‘Girls’ by Stevie Smith from The Collected Poems of Stevie Smith (Penguin) © James McGibbon 1975

Extracts from The Englishman’s Flora by Geoffrey Grigson (Phoenix House 1987)

Extract from A Celtic Miscellany by Kenneth Hurlstone Jackson (Penguin 1971)

Reginald Hill asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780007313181

Ebook Edition © JULY 2015 ISBN: 9780007378548

Version: 2015-06-18

Dedication (#ulink_7abede52-2ed6-5caf-96b7-48c4ae4fa188)

This one’s for

those Six Proud Walkers

in whose company the sun always shines bright

Emmelien

Jane

Liz

Margaret

Mary

Teresa

who most Fridays of the year…on distant hills

Gliding apace, with shadows in their train,

Might, with small help from fancy, be transformed

Into fleet Oreads sporting visibly…

and, of course, laughing and talking and eating

almond slices,

with fondest greetings from

one of the trailing shadows!

Epigraph (#ulink_fd336c42-64a9-5288-bead-3e2922bc78d3)

What song the Syrens sang, or what name Achilles assumed when he hid himself among women, though puzzling Questions, are not beyond all conjecture.

SIR THOMAS BROWNE: Urn Burial

With my own eyes I’ve seen the Sibyl at Cumae hanging in a pot, and when the young lads asked her, what do you want for yourself, Sibyl? she replied, I want to die.

PETRONIUS: The Satyricon

Girls! although I am a woman

I always try to appear human

STEVIE SMITH: Girls!

Contents

Cover Page (#u2f6ceb49-4ff5-5067-87bc-fae8a36833db)

Title Page (#u31ed8494-9bfa-5d58-adc5-6b9d991ade21)

Copyright (#uc08b19f4-b35d-57e8-848b-c0d8ba163db4)

Dedication (#u597a5e52-8b21-5f31-9744-1169d41af957)

Epigraph (#ue6150805-54e2-562b-8669-7d8cdb38ce61)

PROLEGOMENA (#u29229597-eaaa-573a-98af-b715fe13ca77)

BOOK ONE (#uc0d975a5-2f9f-5a48-9cc5-aa26ff7c8fe5)

i spelt from Sibyl’s leaves (#uec1a6971-4043-55eb-854e-15f082e21962)

ii who’s that knocking at my door? (#ubfda9bdf-10b7-5733-8068-1a6d1192ebe7)

iii memories are made of this (#uba2d8726-4604-54d8-93af-db180a744cd3)

iv spelt from Sibyl’s leaves (#u9f4c0437-0ad8-5fbe-b11d-cb9254f57ff7)

v revenge and retribution (#u22a2d5c5-bbbe-5263-8792-4dbcced69961)

vi citizen’s arrest (#ud99b14d7-6460-5b9b-9242-c00a52748179)

vii a pint of guinness (#ub5ea5ac6-d579-5558-8adc-624f3b8e901b)

viii spelt from Sibyl’s leaves (#uf8a18fdd-6552-5d01-8642-eb1de9e13aef)

ix bag lady on a bike (#u100aa0a6-6ac3-5d0f-884c-8797ec1ab551)

x spelt from Sibyl’s leaves (#ub67ff668-7b3a-55cb-969b-d643b2dff8c7)

xi a game of hearts (#litres_trial_promo)

xii doppelgänger (#litres_trial_promo)

xiii the death of Marat (#litres_trial_promo)

xiv a man’s best friend (#litres_trial_promo)

xv spelt from Sibyl’s leaves (#litres_trial_promo)

xvi oats for St Uncumber (#litres_trial_promo)

xvii the juice of strawberries (#litres_trial_promo)

xviii the flowers that bloom in the spring, tra-la! (#litres_trial_promo)

xix pooh on the patio (#litres_trial_promo)

xx the last of the cobblers (#litres_trial_promo)

BOOK TWO (#litres_trial_promo)

i strange encounter (#litres_trial_promo)

ii drudgery divine (#litres_trial_promo)

iii the pavilion by the sea (#litres_trial_promo)

iv spelt from Sibyl’s leaves (#litres_trial_promo)

v realms of gold (#litres_trial_promo)

vi cheated by Protestants (#litres_trial_promo)

vii the sirens’ song (#litres_trial_promo)

viii we galloped all three (#litres_trial_promo)

ix coitus interruptus (#litres_trial_promo)

x belly or bollocks (#litres_trial_promo)

xi spelt from Sibyl’s leaves (#litres_trial_promo)

xii come to dust (#litres_trial_promo)

xiii faery lands forlorn (#litres_trial_promo)

xiv a face from the past (#litres_trial_promo)

xv bloody glass (#litres_trial_promo)

xvi a palomino pony (#litres_trial_promo)

xvii a formal complaint (#litres_trial_promo)

xviii the US cavalry (#litres_trial_promo)

xix I shall wound every man (#litres_trial_promo)

xx liberata liberata (#litres_trial_promo)

xxi an elfin storm (#litres_trial_promo)

xxii spelt from Sibyl’s leaves (#litres_trial_promo)

EPILEGOMENA (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

By Reginald Hill (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PROLEGOMENA (#ulink_90e0b586-a353-5f46-ba19-8497cda3351a)

When I go to see my father, he doesn’t know me.

He’s away somewhere else in a strange land.

I tell myself it’s not all bad. He missed all that suffering when we thought Rosie was going to die. And all those refugees in Africa, and in Europe too, that we see streaming across our television screens, he doesn’t have to worry about them. Global warming, AIDS, the Euro, none of these impinges on his consciousness. He doesn’t even have to feel anxious about his roses when gales are forecast in July.

He sits here in the Home, like ignorance on a monument, smiling at nothing.

At least he’s content, the nurses tell us, and we tell them back, yes, at least he’s content.

Content to be nobody and nowhere.

But I have seen him outside of this room, this cocoon, with memories of somebody and somewhere still intermittent in his mind, staring in bewilderment at the woman who is both his wife and a complete stranger, pausing in the hallway of his own house, unable to recall if he’s heading for the kitchen or the garden and ignorant of which door to use if he does remember, crying out in terror as the dog which has been his most obedient servant for nearly ten years comes bounding towards him, barking its love.

Seeing him like this was bad.

But worse was waking in the night during and after Rosie’s illness, wondering if perhaps what we call Alzheimer’s – that condition in which the world becomes a vortex of fragments, a video loop of disconnected scenes, an absurdist drama full of actors pretending to be old friends and relations – wondering whether perhaps this is not a disease at all but merely a relaxing of some psychological censor which the self imposes to enable us to exist in a totally irrational universe.

Which would mean that dad and all the others are at last seeing things as they really are.

Unvirtual reality.

A sea of troubles.

Confused.

Inconsequential.

Fragments shored against a ruin.

Oh, Mistress Pascoe,

Laud we the gods, and let our crooked smokes climb to their nostrils for glad tidings do I bring and lucky joys. No more I fear the heat of the sun, as time which all these years has wasted me now sets me free, mosthappy news of price, but not for all, for does not time’s whirligig bring in revenges? Thou’rt much in my mind, nor shall I be content till I have seen thy face, when my full eyes shall witness bear to what my full heart feels. May my tears that fall prove holy water on thee! I must be brief, for though my enemies set me free, in freedom lies more danger than in prison, for here through thee and thine the world knows me in their care, but once enlarged, then am I at the mock of all disastrous chances and dangerous accidents by flood and field, with their hands whiter than the paper my obits are writ on and so must wear a mind dark as my fortune or my name. Fate leads me to your side but gives no date, for I must journey now by by-paths and indirect crook’d ways, but sometime sure, when you have quite forgot to look for me, a door shall open, and there shall I be, though you may know me not, but never fear, before I’m done you’ll know me through and through. Till then rest happy while I remain, though brown as earth, as bright unto my vows as faith can raise me.

Close by the margin of a lonely lake, shag-capped by pines that speared a lowering sky from which oozed light unclean whose lurid touch seemed rather to infect than luminate, a deep cave yawned.

Here four men laboured with shovels, their faces wrapped with scarves, not for disguise but as barrier against the stench of the decaying bat droppings they disturbed, while high above them a sea of leathery bodies rippled and whispered uneasily as the sound of digging and the glow of bull-lamps drifted up to the natural vault.

Outside two more men waited silently by a truck which looked almost too broad to have navigated the rutted track curving away like a railway tunnel into the crowding trees. Several yards away on a rocky ledge jutting out over the unmoving, unreflecting waters stood a dusty jeep.

Away to the east, dawn’s rosy fingers were already pulling aside the mists which shrouded the sleeping land, but here the exhalations of the lake still hung grey and heavy over the waters, the vehicle, and the waiting men.

At last from the cave’s black mouth two figures emerged, labouring under the weight of a long metal box they carried between them.

They set it down on the ground behind the truck. One of the waiting men, his thinning yellow hair clinging to his brow like straw to a milkmaid’s buttocks, stooped to unlock the container. Glancing up at the other man from black and bulging eyes, he paused like a vampiricide about to open a coffin, then flung back the lid.

The other man, slim and dark with a narrow moustache, looked down at the oiled and gleaming tubes of metal for a moment, then nodded. The first man snapped his fingers and the diggers closed the box and lifted it onto the back of the truck. Then they returned to the cave, passing en route their two companions staggering out with a second box.

Many times was this journey made, and while the labourers laboured, the watchers went round to the front of the truck and the slim man opened the passenger door, reached inside and picked up a large square leather case which he set on the seat and opened.

The straw-haired, bulging-eyed man produced a flattened cylinder of ivory and pressed a stud to release a long, slightly curved blade. Delicately he nicked two of the plastic containers which packed the case, licked his index finger, inserted it into the first incision, tasted the powder which clung to his damp flesh, repeated the process with the second, and nodded his accord.

The dark man closed the case then took the other’s outstretched hand.

‘Nice to do business,’ said bulging eyes. ‘My best to young Kansas.’

The other looked puzzled for a moment then smiled. The older man too had a speculative look on his face as he held onto the other’s hand rather longer than necessary. Then he too smiled and shook his head as though to dislodge a misplaced thought, let go and took the grip to the jeep where he laid it on the back seat.

By now the loading of the truck was complete and the four diggers stretched their aching limbs in the mouth of the cave and unwound their protecting scarves. Two were ruddy-faced with their exertions, the other two flushed dark beneath their sallow skins.

The first pair went towards the jeep while the second pair joined the slim man who was securing the tailgate of the truck.

These two looked at each other, exchanged a brief eye signal, then reached for the holsters beneath their arms, drew out automatic pistols, and moved towards the jeep, firing as they walked. The two ruddy-faced diggers took the bullets in their backs and pitched forward on their faces while ahead of them the straw-haired man fell backwards, his eyes popping even further in astonishment under the fillet of blood which wrapped itself around his brow.

One of the gunmen continued to the jeep and leaned into it to retrieve the grip. His companion meanwhile turned back to the truck where the slim man was standing as if paralysed.

‘Chiquillo!’ he called. ‘Recuerdo de Jorge. Adiós!’ And let go a long burst.

The slim man felt a whip of hot pain along his ribcage which sent him spinning like a top behind the truck. The rest of the burst went straight through the mouth of the cave where the bullets ricocheted around the granite walls and up into the high vault, triggering first a rustling ripple, then a squeaking, wing-beating eruption of bats.

The gunman paused, looking up in wonderment as the bats skeined out of their rocky roost and smudged the dark air overhead. So many. Who would have thought there would be so many?

Then as they vanished among the trees he resumed his advance.

But the pause had been long enough for the slim man to reach under the truck and drag down the weapon taped beneath the wheel arch.

He shot the gunman through the leg as he passed by the truck’s rear wheel, then through the head as he crashed to the ground.

The second gunman dropped the grip and crouched low with his weapon aimed towards his dying companion.

But the slim man came rolling out of the other side of the truck, and gave himself time to take aim and make sure his first shot found its target.

The second gunman held his crouching position for a moment, then toppled slowly sideways and lay there, gently twitching, his visible eye fixed on the trees’ high vault. The slim man approached carefully, one arm wrapped round his bleeding side, and emptied the clip into the watching eye.

Then he sat down on the grip and pulled open his shirt to examine his wound.

It was more painful than life-threatening, flesh laid bare, a rib nicked perhaps, no deeper penetration. But blood was pouring out and by the time he’d bound it up with strips of shirt torn from the dead gunman at his feet, he’d lost a lot of blood.

He opened the grip, took out one of the packets the pop-eyed man had nicked, poured some of the powder into his hand, raised it to his nose and took a long hard sniff.

Then he took out a mobile phone and dialled.

‘Soy yo… si… I did not think so soon… si…poco… not so wide as a barn door… the CP… it has to be… I am sorry… dos horas… quizá tres… si… at the CP… si, bueno… te quiero… adiós.’

He put the phone away and picked up the grip, wincing with pain. As he moved away, he thought he sensed a movement from the vicinity of the jeep and turned with his gun waving menacingly.

All was still. He hadn’t the strength for closer investigation. And in any case, his gun was empty.

He resumed his progress to the truck.

Getting the grip into the driver’s cab and himself after it was an agony. He sat there for a while, leaning against the wheel. Did something move by the jeep or was it his pain giving false life to this deadly tableau? Certainly in the air above, the bats, reassured by the return of stillness, were flitting back into the mouth of the cave.

He dipped into the grip again, sniffed a little more powder.

Then he switched on the engine, engaged gear, and without a backward glance at the gaping cave, the gloomy lake or the bodies that lay between them, he sent the truck rumbling into the dark tunnel curving away through the crowding trees.

High on the sunlit, windswept Snake Pass which links Lancashire with Yorkshire, Peter Pascoe thought, I’m in love.

Even with a trail of blood running from her nose over the double hump of her full lips to peter out on her charming chin, she was grin-like-an-idiot-gorgeous.

‘You OK?’ he said, grinning like an idiot till he realized that in the circumstances this was perhaps not the most appropriate expression.

‘Yes, yes,’ she said impatiently, dabbing at her nose with a tissue. ‘Is this going to take long?’

The driver of her taxi, to whom the question was addressed, looked from the bent and leaking radiator of his vehicle to the jackknifed lorry he had hit and said sarcastically, ‘Soon as I repair this and get that shifted, we’ll be on our way, luv.’

Pascoe, returning from Manchester over the Snake, had been behind the lorry when it jackknifed. Simple humanitarian concern had brought him running to see if anyone was hurt, but now his sense of responsibility as a policeman was taking over. He pulled out his mobile, dialled 999 and gave a succinct account of what had happened.

‘Better set up traffic diversions way back on both sides,’ he said. ‘The road’s completely blocked till you get something up here to shift the lorry. One injury. Passenger in the taxi banged her nose. Lorry driver probably suffering from shock. Better have an ambulance.’

‘Not for me,’ said the woman vehemently. ‘I’m fine.’

She rose from the verge where she’d been sitting and moved forward on long legs, whose slight unsteadiness only added to their sinuous attraction. She looked as if she purposed to move the lorry single-handed. If it had been sentient, she might have managed it, thought Pascoe.

‘Silly cow’d have been all right if she’d put her seat belt on like I told her,’ said the taxi driver.

‘Perhaps you should have been firmer,’ said Pascoe mildly. ‘Who is she? Where’re you headed?’

No reason why he should have asked or the driver answered these questions, but without his being aware of it, over the years Pascoe had developed a quiet authority of manner which most people found harder to resist than mere assertiveness.

The driver pulled out a docket and said, ‘Miss Kelly Cornelius. Manchester Airport. Terminal Three. She’s going to miss her plane.’

He spoke with a satisfaction which identified him as one of that happily vanishing species, the Ur-Yorkshireman, beside whom even Andy Dalziel appeared a creature of sweetness and light. Only a hardcore misogynist could take pleasure in anything which caused young Miss Cornelius distress.

And she was distressed. She returned from her examination of the lorry and gave Pascoe a look of such expressive unhappiness, his empathy almost caused him to burst into tears.

‘Excuse me,’ she said in a melodious voice in which all that was best of American lightness, Celtic darkness, and English woodnotes wild, conjoined to make sweet moan, ‘but your car’s on the other side of this, I guess.’

‘Yes, I’m on my way home to Mid-Yorkshire,’ he said. ‘Looks like I’ll have to turn around and find another way.’

‘That’s what I thought you’d do,’ she said, her voice breathless with delight, as if he’d just confirmed her estimate of his intellectual brilliance. ‘And I was wondering, I know it’s quite a long way back, but how would you feel about taking me to Manchester Airport? I hate to be a nuisance, but you see, I’ve got this plane to catch, and if I miss it, I don’t know what I’ll do.’

Tears brimmed her big dark eyes. Pascoe could imagine their salty taste on his tongue. What she was asking was of course impossible, but (as he absolutely intended to tell Ellie later when he cleansed his conscience by laundering his prurient thoughts in her sight) it was flattering to be asked.

He said, ‘I’m sorry, but my wife’s expecting me.’

‘You could ring her. You’ve got a phone,’ she said with tremulous appeal. ‘I’d be truly, deeply, madly grateful.’

This was breathtaking, in every sense.

He said, ‘Surely there’ll be another plane. Where are you going anyway?’

Silly question. It implied negotiation.

There was just the hint of a hesitation before she answered, ‘Corfu. It’s my holiday, first for years. And it’s a holiday charter, so if I miss it, there won’t be much chance of getting on another, they’re all so crowded this time of year. And I’m meeting my sister and her little boy at the airport, and she’s disabled and won’t get on the plane without me, so it’ll be all our holidays ruined. Please.’

Suddenly he knew he was going to do it. All right, it was crazy, but he was going to have to go back all the way to Glossop anyway and the airport wasn’t much further, well, not very much further…

He said, ‘I’ll need to phone my wife.’

‘That’s marvellous. Oh, thank you, thank you!’

She gave him a smile which made all things seem easy – the drive back, the phone call to Ellie, everything – then dived into the taxi and emerged with a small leather case like a pilot’s flight bag.

Travelling light, thought Pascoe as he stepped back to get some privacy for his call home. The woman was now talking to the taxi driver and presumably paying him off. There seemed to be some disagreement. Pascoe guessed the driver was demanding the full agreed fare on the grounds that it wasn’t his fault he hadn’t got her all the way to Terminal 3.

Terminal 3.

Last time he’d flown out of Manchester, Terminal 3 had been for British Airways and domestic flights only.

You couldn’t fly charter to Corfu from there.

Perhaps the driver had made a mistake.

Or perhaps things had changed at Manchester in the past six months.

But now he was recalling the slight hesitancy before the sob story. And would a young woman on holiday really travel so light…?

Pascoe, he said to himself, you’re developing a nasty suspicious policeman’s mind.

He turned away and began to punch buttons on his phone.

When it was answered he identified himself, talked for a while, then waited.

In the distance he heard the wail of sirens approaching.

A voice spoke in his ear. He listened, asked a couple of questions, then rang off.

When he turned, Kelly Cornelius was standing by the taxi, smiling expectantly at him. A police car pulled up onto the verge beside him. An ambulance wasn’t far behind.

As the driver of the police car opened his door to get out, Pascoe stooped to him. Screened by the car, he pulled out his ID, showed it to the uniformed constable and spoke urgently.

Then he straightened up, waved apologetically to the waiting woman, flourishing his phone as if to say he hadn’t been able to get through before.

He began to dial again, watching as the policemen went across to the taxi and started talking to the driver and the woman.

‘Hi,’ said Pascoe. ‘It’s me. Yes, I’m on my way but there’s been an accident… no, I’m not involved but I am stuck, the road’s blocked, and I’m going to have to divert… yeah, take me when I come… give Rosie a kiss… how’s she been today?… yes, I know, it’s early days… it’ll be OK, I promise… love you… ’bye.’

He switched off and went back to the taxi.

‘What the hell do you mean, I can’t go?’ the young woman was demanding. Anger like injury did nothing to detract from her beauty.

‘Sorry, miss,’ said the policeman stolidly. ‘Can’t let you leave the scene of an accident where someone’s been injured.’

‘But I’m the one who’s been injured so if I say it doesn’t matter…’

‘Doesn’t work like that,’ said the policeman. ‘Need to get you checked out at hospital. There may be claims. Also you’re a witness. We’ll need a statement.’

‘But I’ve got a plane to catch.’ Her gaze met Pascoe’s. ‘Corfu. It’s my holiday.’

A sharp intake of breath from the policeman.

‘Certainly can’t let you leave the country, miss, that’s definite,’ he said. ‘Here’s the ambulance lads now. Why not let them give you the once-over while I talk to these other gents?’

Pascoe caught her eye and shrugged helplessly. She looked back at him, her face (still beautiful) now ravaged with shock and betrayal, as Andromeda might have looked if Perseus, on point of rescuing her from the ravening dragon, had suddenly remembered a previous appointment.

‘Well, if you’re done with me, Officer, I think I’d better start finding another route home,’ he said, looking away, unable to bear that devastatingly devastated expression.

The constable said, ‘Right, sir. We’ve got your name in case we need to be in touch. Goodbye now.’

As he made his way back to his car, Pascoe reflected on the paradox that now he felt much more guilty about Kelly Cornelius than he had before, when it had just been a question of simple reflexive desire.

Women, he thought as he sat in his car and put the necessary enquiries in train. Women! All of them queens of discord, blessed with the power even on the slightest acquaintance to get in a man’s mind and divide and rule. Look at him now, sitting here when he should be heading home, checking out his vague suspicions like a good professional, uncertain whether he would be bothering if he hadn’t felt so ready to submit to this lovely creature’s control, with part of him hoping even as he started the process that he was going to come out of this looking a real dickhead.

Women. How come they didn’t rule the universe?

COMFORT BLANKET

Arms and the Men they sang, who played at Troy

Until they broke it like a spoiled child’s Toy

Then sailed away, the Winners heading home,

The Losers to a new Play-pen called Rome.

Behind, like Garbage from their vessels flung,

– Submiss, submerged, but certainly not sung –

A wake of Women trailed in long Parade,

The reft, the raped, the slaughtered, the betrayed.

Oh, Shame! that so few sagas celebrate

Their Pain, their Perils, their no less moving Fate!

But mine won’t either, for why should it when

The proper Study of Mendacity is MEN?

BOOK ONE (#ulink_b12c08d2-2b6d-5a29-beca-f77ced5eff70)

‘Your pretty daughter,’ she said, ‘starts to hear of such things. Yet,’ looking full upon her, ‘you may be sure that there are men and women already on their road, who have their business to do with you, and who will do it. Of a certainty they will do it. They may be coming hundreds, thousands, of miles over the sea there; they may be close at hand now; they may be coming, for anything you know, or anything you can do to prevent it, from the vilest sweepings of this very town.’

CHARLES DICKENS: Little Dorrit

i

spelt from Sibyl’s leaves (#ulink_ff097a81-f5b7-5e4d-b4e8-3ec0b1256b90)

Eleanor Soper…

The little patch of blue I can see through the high round window is probably the sky, but it could just as well be a piece of blue backcloth or a painted flat.

licks up the blood from the square where a riot has been…

Distantly I hear a clatter of hooves. They’re changing guard at… I’ve heard them do it thousands of times. But hearing’s as far as it goes. They could be mere sound effects, played on tape. You don’t take anything on trust in this business. Not even your friends. Especially not them.

I who know everything knew nothing till I knew that.

what does it mean?…

The only unquestionable reality lies in the machine.

But while reality hardly changes at all, the machine has changed a lot. It grows young as I grow old.

Shall I like my namesake grow old forever?

My namesake, I say. After so long usage, am I beginning to believe as so many of the young ones clearly believe that my name really is Sibyl? Strange that the name my parents gave me also labelled me as a woman of magic, but an enchantress as well as a seer. Morgan. Morgan Meredith. Morgan le Fay, as Gaw used to call me in the days of his enchantment.

But now my enchanting days are over. And it was Gaw who rechristened me when he saw that I had no magic to counter the sickness in my blood.

A wise man hides his mistakes in plain sight, then over long time slowly corrects them.

My dear old friend Gawain Clovis Sempernel is a wise man. No one would deny it. Not if they’ve any sense.

Aroynt thee, hag. Ripeness is all. And I have work to do.

When I first took on my sacred office, the machine loomed monumentally, like a Victorian family tomb. Thirty years on, it’s smaller than an infant’s casket, leaving plenty of room on the narrow tabletop for my flask and mug, and also my inhaler and pill dispenser, though generally I keep these hidden. Sounds silly when you’re in a wheelchair, but I was brought up to believe you don’t advertise your frailties.

That’s a lesson a lot of folk never learn, which is why so many of them end up frozen in my electronic casket where there’s always room for plenty more.

If I wanted I could ask it to tell me exactly how many people had passed through my hands, or rather my fingertips, for that’s the closest I get to actually handling people. But I don’t bother. This isn’t about statistics, this is about individuals.

Eleanor Soper…

My casket is also an incubator. Here they make their first appearance, often looking completely helpless and harmless. But, oh, how quickly they grow, and I oversee their progress with an almost parental pride as their details accumulate and their files fatten out.

Some live up to their promise. (By which I mean threat!)

Others, apparently, change direction completely. Such converts I always regard with grave suspicion, even if – especially if – they make it to the very top. They’re either faking it, in which case we’re ready for them. Or they’re genuine, which means the contents of these files could be a serious embarrassment.

It’s always nice to know you can embarrass your masters.

But the great majority merely fade away, become ghosts of their vibrant young selves.

married a cop, had a kid, didn’t march any more…

what was it for?

Let’s take a look at your protesting career, Eleanor Pascoe née Soper.

Amnesty – member, non-active; Anti-Fascist Action – lapsed; Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament – lapsed; Gay Rights – lapsed; Graduates Against God – lapsed; Greenpeace – member, non-active; Labour Party –member, non-active; Liberata Trust –member, active; Quis Custodiet? – lapsed; Third World United – lapsed; Women’s Rights Action Group – lapsed; World Socialist Alliance – lapsed.

Once you squawked so loud in your incubator, Eleanor, now you rest so quiet.

Gaw Sempernel (let no dog bark) says there is nothing so suspicious as silence. Must have watched a lot of cowboy films in his youth. It’s quiet out there, Gaw… too damn quiet!

Certainly neither sound nor silence gets you out of my casket. Once inside, there you stay forever. And if your presence is ever needed, you can be conjured up in a trice, like the wraiths of the classical underworld, which, as my classically educated Gawain likes to remind me, were summoned to appear and to speak by the smell and the taste of fresh blood.

For machines may change, and fashions change, and human flesh, God help us, changes most inevitably of all.

But some people, my people, have at their hearts something which refuses to change, despite all that life shows them by way of contra-evidence. Perhaps it is a genetic weakness. Certainly, once established, like the common cold, no one has yet found a way of eradicating it.

Which is why I, practising what I preach, have demonstrated to the world (or that section of it which shares this remote and lonely building in the heart of this populous city), that there is life after death by staying in gainful employment all these years, Sibyl the Sibyl, sitting here in my solitary cell, hung high in my lonely cage, laying the bodies out neatly in my electronic casket, and, when necessary, conjuring them back to life.

My poor benighted ghosts scenting blood once more…

Like Eleanor Soper.

All these looney people, where do they all come from?

All these looney people, where do they all belong?

ii

who’s that knocking at my door? (#ulink_467e279c-433a-5aa9-a6fd-aef9ff753b51)

…why should it, when

The proper study of mendacity is MEN?

Chapter 1

It was a dark and stormy night.

Now, why has that gone down in the annals as the archetype of the rotten opening? she wondered. It’s not much different from It was a bright cold day in April, though, fair do’s, the bit about the clocks striking thirteen grabs the attention. Or how about There was no possibility of taking a walk that day, with all the stuff about the weather that follows? And even Homer’s jam-packed with meteorology. OK, so what follows in every case is a lot better book than Paul Clifford, but even if we stick to the same author, surely the dark and stormy stuff isn’t in the same league as the opening of The Last Days of Pompeii (which, interestingly, I found on Andy Dalziel’s bedside table when I used a search for the loo as an excuse to do a bit of nebbing! Riddle me that, my Trinity scholar!).

How does it go? ‘Ho, Diomed, well met! Do you sup with Glaucus tonight?’ said a young man of small stature, who wore his tunic in the loose and effeminate folds which proved him to be a gentleman and a coxcomb. Now that is positively risible, while the dark and stormy night is simply a cliché which, like all clichés, was at its creation bright new coin.

So up yours, all you superior bastards who get on the media chat shows. I’m sticking with it!

It was a dark and stormy night. The wind was blowing off the sea and the guard commander bowed into it with his cloak wrapped around his face as he left the shelter of the grove and began to clamber up to the headland.

The darkness was deep but not total. There was salt and spume in the wind giving it a ghostly visibility, and now a huge flock of white sea birds riding the blast went screeching by only a few feet over his head.

The superstitious fools huddled round their fires in the camp below would probably take them as an omen and argue over which god was telling them what and pour out enough libations to get the whole of Olympus pissed. But the commander didn’t even flinch.

As he neared the crest of the headland, hescrewed up his eyes and peered ahead, looking for a darker outline against the black sky which should show where the wind wrapped itself around the sentry. There’d been grumblings among the weary crewmen when he’d insisted on posting a full contingent of perimeter guards. In the forty-eight hours since they made landfall, they’d found no sign of human habitation, and with the storm which had made them run for shelter blowing as hard as ever, the threat of a seaborne attack seemed negligible. With the democracy of shared hardship, they’d even appealed over his head to the Prince.

‘So you feel safe?’ he’d said. ‘Is that more safe or less safe than when you saw the Greek ships sail away?’

That had shut them up. But the commander had resolved to make the rounds himself to check that none of the posted sentries, feeling secure in the pseudo-isolation of the storm, had opted for comfort rather than watch.

And it seemed his distrust was justified. His keen gaze found no sign of any human figure on the skyline. Then a small movement at ground level caught his straining eyes. Cautiously he advanced. The movement again. And now he could make out the figure of a man stretched out on his stomach right at the cliff’s edge.

Silently he drew his sword and moved closer. If the idle bastard had fallen asleep he was in for a painful reveille. But when he was only a paceaway, his foot kicked a stone and the sentry’s head turned and their eyes met.

Far from showing alarm, the man looked relieved. He laid a finger over his lips, then motioned to the commander to join him prostrate.

When they were side by side, the sentry put his mouth to his ear and said, ‘I think there’s someone down there, Commander.’

It didn’t seem likely, but this was a battle-scarred veteran who’d spent ten years patrolling the Wall, not some fresh-faced kid who saw a bear in every bush.

Cautiously he wriggled forward till his head was over the edge and looked down.

He knew from memory that the rocky cliff fell sheer for at least eighty feet down to a tiny shingly cove, but now it was like looking into hellmouth, where Pyriphlegethon’s burning waves drive their phosphorescent crests deep into the darkness of woeful Acheron.

Nothing could live down there, nothing that still had dependence on light and air anyway, and he was moving back to give the sentry a tongue-lashing when suddenly the wind tore a huge hole in the cloud cover and a full moon lit up the scene like a thousand lanterns.

Now he saw, though he could hardly believe what he saw.

The waves had momentarily retreated to reveal the figure of a man crawling out of the sea. Then the gale sent its next wall of water rushing forwardand the figure was buried beneath it. Impossible to survive, he thought. But when the sea receded, it was still there, hands and feet dug deep into the shingle. And in the few seconds of respite given by the withdrawing waters, the man scrambled forward another couple of feet before sinking his anchors once again.

Sometimes the suction of the retreating waves was too strong, or his anchorage was too shallow, and the recumbent body was drawn back the full length of its advance. But always when it seemed certain that the ocean must have driven deep into his lungs, or the razor-edged shingle must have ripped his naked chest wide open, the figure pushed itself forward once more.

‘He’ll never make it,’ said the sentry with utter assurance.

The guard commander watched a little while longer then said, ‘Six to four he does. In gold.’

The veteran looked down at the sea which now seemed to be clutching at the body on the beach with a supernatural fury. It looked like a sure-fire bet, but he had a lot of respect for the commander’s judgement.

‘Silver,’ he compromised.

They settled to watch.

It took another half-hour for the commander to win his bet, but finally the crawling man had dragged himself right up to the foot of the cliff where a couple of huge boulders resting on the beach formed a protective wall against which thesea dashed its mountainous missiles in vain. For a while he lay there, still immersed in water from time to time, but no longer at risk of being either beaten flat or dragged back into the depths. Then, just when the sentry was hoping he might claim victory in the bet by reason of the man’s death, he sat upright.

‘That sod must be made of bronze and bear hide,’ said the sentry with reluctant admiration. ‘What the fuck’s he doing now?’

For the figure on the beach had pushed himself to his feet, and as the waters drew back, he emerged from his rocky refuge and, to the observers’ amazement, began a kind of lumbering dance, following the receding waves, then backpedalling like mad as they drove forward once more. And all the while he was gesticulating, sometimes putting his left hand in the crook of his right elbow and thrusting his right fist into the air, sometimes putting both his thumbs into his mouth, then pulling them out with great force and stabbing his forefingers seawards, and shouting.

‘I’ve seen that before,’ said the sentry. ‘That’s what them bastards used to do under the Wall.’

‘Hush! I’m trying to hear what he’s saying,’ said the commander.

As if in response, the wind fell for a moment and the sea drew back to its furthest point yet, still pursued by the dancing man whose shouts now drifted clearly up the cliff face.

‘Up yours, old man!’ he yelled. ‘Call yourselfearthshaker? You couldn’t shake your dick at a pisspot! So what are you going to do now, you watery old git? Ha ha! Right up yours!’

‘You’re right. He’s a Greek,’ said the commander.

‘Better still, he’s a dead Greek,’ said the veteran with some satisfaction.

For in his growing boldness, the dancing man had allowed himself to be lured far away from his protective wall by this moment of comparative calm, so when the ocean suddenly exploded before him, he had no hope of getting back to safety. An avalanche of water far greater than anything before descended on him, driving him to the ground, then burying him deep. And at the same time the renewed fury of the wind sewed up the rent in the cloud and darkness fell.

‘If he was talking to who I think he was talking to, he was a right idiot,’ said the sentry piously. ‘You gotta give the gods respect else they’ll chew you up and spit you out.’

The commander smiled.

‘Let’s see,’ he said.

They didn’t have long to wait. As though the storm also wanted to look at the results of its latest onslaught, it tore aside the clouds once more.

‘Well, bull my bollocks and call me Zeus!’ exclaimed the sentry, his recent piety completely forgotten.

There he was again, almost back where he’d started but still alive. Once more he started tostruggle back over the beach. Only now as the waves retreated, they didn’t leave any area of visible shingle but a foot or so of water. This made the anchoring process much more difficult, but at the same time, by permitting the man to take a couple of swimming strokes with his muscular arms, it speeded his return to the safety of the boulders. Here he squatted, his head slumped on his broad chest which rose and fell as he drew in great breaths of damp air.

‘He’s game,’ said the sentry grudgingly. ‘Got to give him that. But he’s not out of trouble yet. How high do you reckon the tide comes in here, Commander?’

‘Normally? I think it would just about reach the bottom of the cliff, a foot up at its highest. But this isn’t normal. I don’t know whether it’s a very angry god or just very bad weather, but I’d say the way this wind’s blowing the sea in, it will be thirty feet up the cliff face in an hour.’

‘So that really is it,’ said the sentry with some satisfaction.

‘Not necessarily. He can climb.’

‘Up that rock face? Get on! It’s smooth and it’s sheer and there’s an overhang at the top. I wouldn’t fancy my chances there at my peak on a fine day, and that old bugger must be completely knackered.’

‘Double or quits on what you owe?’ said the commander casually.

The sentry turned his head to look at the officer’sprofile, but it was as blank and unreadable as the cliff face, and not a lot more attractive either.

Then he looked down. The man was up to his knees in water already.

‘Done,’ said the sentry.

Below, the Greek was examining the cliff face. His features were undiscernible through a heavy tangle of beard, but even at this distance they could see the eyes shining brightly in the reflection of the moonlight. He rubbed his hands vigorously against the remnants of his robe in what had to be a vain attempt to get them dry, then he reached up and began to climb.

He got about three feet above the water level before he lost his grip and slithered back down. Three more times he tried, three more times he fell. And each time he hit the water, it was higher than before.

‘Looks like we’re quits, Commander,’ said the sentry.

‘Maybe.’

‘What’s the silly old sod doing now?’

The silly old sod was ripping the sleeves off his tattered robe, and tying them to form a rough sack which he hung on a jag of rock protruding from one of his protective boulders. Next he knelt down in the water facing the boulder, took a deep breath, and plunged his head beneath the surface. When he emerged, he tossed what looked like a stone into the dangling sack. Again and again he did this.

‘I know,’ said the sentry. ‘He’s digging a tunnel.’

He laughed raucously at his own wit till the guard commander said coldly, ‘Shut up. You might learn something.’

The sentry stopped laughing. Shared hardship might relax the bonds of discipline slightly, but he and his comrades knew just how far they could go.

Finally the Greek stood upright once more, slung the sack around his neck, put both hands into it, then reached up the cliff face. He seemed to lean against it for a long moment, almost as if he were praying. Then he began to climb again.

The sentry waited for him to fall. But he didn’t. From time to time he dipped into his sack, then reached up again in search of another handhold. As on the beach, progress was painfully slow, and occasionally one of his holds failed and he’d slip back a little, but still he kept coming.

‘How in the name of Zeus is he doing that?’ said the sentry. ‘It’s just not possible!’

‘Molluscs,’ said the commander.

‘No need to be like that, sir,’ said the sentry resentfully. ‘I was only asking.’

‘I said, molluscs. Clams, mussels, oysters, anything he could find. He’s holding them against the wall till their suckers take a hold. Then he uses them as a ladder.’

‘Clams, you say? Them things couldn’t hold a man, surely?’

‘Three might. He only moves one foot or hand at a time. And he’s using any holds he can find in the rock face too. He’s a truly ingenious fellow.’

The sentry shook his head in reluctant admiration. As if taking this as confirmation that their prey was close to escaping them, the waves hurled themselves with renewed force against the cliff, breaking over the climbing man and spraying flakes of spume over the watchers above.

A harsh grating noise reached them also.

‘The bugger’s laughing!’ said the sentry.

‘Of course he’s laughing. He wants the cliff face to be as wet as possible. That’s the way the molluscs like it. The wetter the surface, the tighter their grip.’

The wind closed the gap in the clouds once more. This, coupled with the fact that the climber was now approaching the overhang, took him out of the watchers’ sight. The sentry pushed himself back from the edge, squatted to his haunches and drew his sword.

‘Let’s see if he’s still laughing when he sticks his head over the top and I cut his throat,’ he said, testing the metal’s edge with his thumb.

The guard commander said nothing but squatted beside him. They had to lean into the wind to avoid being blown backwards and from time to time their faces were lashed with salt water as the ocean rose to new heights of fury in its efforts to wash the climber free.

Minutes passed. The watchers didn’t move. Theyhad had years to learn that patience too is one of the great military arts.

Finally the sentry’s face began to show his suspicion that the sea must after all have won its battle against the climbing Greek. He glanced at the guard commander. But his was a face as jagged and pocked as a city wall after long siege, and quite unreadable at the best of times, so the sentry didn’t risk speaking and returned to his watch.

A few moments later he was glad of his self-restraint. A new sound drifted up the cliff face amidst the lash of water and howl of wind. It was the noise of laboured breathing, getting closer.

The sentry began to smile in happy anticipation. He decided not just to slit the throat but to have a go at taking the whole head off. It would be fun to go back into the camp and toss it down among his half-waking comrades and say negligently, ‘Got myself another Greek while you idle sods were sleeping.’

The breathing was loud now. The sentry moved his position so that he was right above it. An arm like a small tree trunk was swung up to rest on the edge of the cliff, and then a shag of salt-caked hair appeared, and finally the man’s head came fully into view and a pair of deep-sunk, intensely blue eyes took in the waiting men.

‘How do, chuck,’ said the Greek.

The sentry rocked forward on his toes and shot out his left hand to grab the grizzled hair. Butquick as he moved, the Greek was quicker. His other hand came into view, grasping a large jagged clamshell. It snaked out almost faster than the eye could follow, and the next moment the sentry’s left wrist was slit through to the bone.

He fell backward, shrieking. His right hand released his sword as he grasped the gaping wound to staunch the spurting blood. The Greek dropped the shell and reached out to pick up the fallen weapon. Then a heavy-shod foot crashed down on his forearm and pinned it to the ground.

He looked up at the unreadably rugged face of the guard commander and smiled through his tangle of beard.

‘Thanks, chuck,’ he said. ‘Saved me from a nasty fall.’

‘Kill the bastard, Commander,’ urged the ashen-faced sentry. ‘Chop his fucking arm right off!’

The commander was aware of the blue eyes fixed quizzically on his face as he debated the matter.

‘Not yet,’ he said finally. ‘Not till we know if there are any more of his kind about. Besides, the men need cheering up after what’s happened recently, and I reckon a clever old Greek like this will take a long time dying.’

‘Long as you like, Captain,’ said the Greek. ‘I’m in no hurry whatsoever. I’ll

‘Shit,’ said Ellie Pascoe.

Through the open window of the boxroom which she refused to dignify with the name study she had heard a car turning into their short drive.

She finished reading, take as long as ever you like.’, pressed Save to preserve her corrections and went to the window.

A man and a woman were getting out of the car and heading for the front door.

‘Hello,’ called Ellie.

This voice from above made them start like guilty things surprised, and the woman dropped her car keys.

Perhaps they think it’s the voice of God, thought Ellie.

Or perhaps (one thought leading to another) they think they are the voice of God.

‘If you’re Witnesses,’ she called, ‘I think I should tell you we’re all communist satanists here. I’ll be happy to send you some of our literature.’

‘Mrs Pascoe?’ said the woman. ‘Mrs Ellie Pascoe?’

She didn’t look like a Witness. And Witnesses didn’t drive big BMWs.

A pair of assertions as unsupported as a Hottentot’s tits (she plucked the phrase from her collection of Andy Dalziel memorabilia), but evidence is what we look for when intuition fails (one of her constabulary-baiting own).

‘Hang on. I’ll come down,’ she said.

By the time she got downstairs and opened the front door, the couple had recovered their composure. Now they just looked concerned.

‘Mrs Pascoe?’ said the man, who was slim, thirtyish, not bad-looking and wearing a rather nice Prince of Wales check suit which looked like it had been cut in Savile Row. Would look even nicer on Peter. ‘You are Mrs Pascoe?’

‘I thought we’d established that.’

‘My name’s Jim Westcombe. I’m with the council’s Education Welfare Department. It’s about your daughter, Rose. She’s at Edengrove Junior, isn’t she?’

‘Yes, but not today. I mean, it’s their end-of-term trip to Tegley Hall Theme Park… look, what’s this about?’ Ellie demanded.

The man and woman looked at each other, then the man went on, ‘Honestly, there’s nothing to worry about, she’s fine, you’re not to worry, really…’

‘What?’

There are few things more worrying to a mother than being told not to worry, especially a mother who a few short weeks ago was sitting by a hospital bed, not knowing if her child was going to recover from meningitis or not.

The woman gave her a look which combined empathy of her feelings and exasperation at her companion’s heavy-handedness.

‘Jim, shut up,’ she said. ‘Mrs Pascoe, the coach taking the children to Tegley has broken down. There’s a replacement coach on the way, but it seems your little girl wasn’t feeling too well and the head teacher thought it best to make arrangements to get her home, only when he tried to ring you he couldn’t get through…’

Ellie turned and grabbed the hall phone. It was dead. In the mirror hanging above the phone, she saw an unrecognizably pale face whose pallor shone through her summer tan like a corpse-light through muslin. This was it. This was the punishment she deserved. She had brought it on herself… worse… on Rosie… on Peter…

‘… so he tried your husband but he wasn’t available, so then he rang into the Education office and as Jim and I were coming out this way and would be passing your road end, we said we’d call and check if you were in.’

‘Oh God,’ said Ellie.

I’m confused, she thought. I’m not hearing properly.

She leaned against the door frame to steady herself and the woman reached forward to rest her hand on Ellie’s arm and said, ‘Really, it’s OK, Mrs Pascoe. You know how it is, end of term, kids getting excited, rushing around like mad. I’ve got two myself, I know how they can keep us frightened, believe me. It’s just a matter of getting out there to pick the little girl up. Have you got your car here? Jim can go with you, he knows where the breakdown happened. I can’t come myself, I’m afraid. I’ve got an urgent appointment, but Jim can spare a couple of hours, can’t you, Jim? He’ll even drive if you don’t feel up to it.’

‘Surely,’ said the man. ‘No problem at all. Let’s get started, shall we? Sooner we’re on the way, sooner you can get your little girl home.’

Ellie took a deep breath. It wasn’t enough. She took another. It was like squirting oil onto a piece of rusty machinery. She could almost hear the gears of her mind starting to grate against each other as she reviewed everything that had been said to her.

She said, ‘Sorry. This has knocked me out. I’m not usually so slow. It was just a bit of a shock. I thought you were trying to tell me there’s been an accident…’

‘Nothing like that,’ said the woman. ‘Really.’

‘And did you talk to Mr Johnson, the head, yourself? You’re sure he said it was nothing to worry about?’

‘Yes, I spoke direct with Mr Johnson,’ said the woman firmly. ‘Just a tummy bug, he reckoned. But she really wants to be home rather than bumping around on a bus all day.’

‘And if it was anything more serious, the sooner we get out there, the better, eh?’ said the man heartily.

‘Jim, please!’ said the woman reprimandingly.

‘No, it’s OK,’ said Ellie, stepping forward and smiling at the man. ‘It’s always best to be ready for the worst. Are you ready, Mr Westcombe?’

Then she brought her knee up as hard as she could between his legs.

It was good to see his face drain pale as her own.

Now she swung her right arm round hard at the woman’s neck. The blow would probably have felled her, but she was quick and ducked low, though not low enough to avoid all contact. Ellie’s hand caught her on the temple just above the right eye with enough force to send her reeling back into the Climbing Pompon de Paris growing up the pillar to the left of the front porch.

When Ellie had bought it, Peter had grumbled that nowadays it was surely possible to get a less prickly, more user-friendly rose, but she’d been unrepentant. The tiny pink pompom blossoms had been her father’s favourite before Alzheimer’s robbed him of even that. And now, as she heard the woman scream, Ellie knew she’d always love the thorns too.

She retreated over her threshold and slammed the door shut. Ramming the bolts home, she became aware of pain in her right wrist, and as she slid to the floor with her back against the door, in her right knee too. She sat there, breathing deep, as if she’d just run a hundred metres up a steep hill. Outside she heard car doors shut and an engine start up and reverse away.

She sat there till there was nothing to hear but her own harsh breathing, and when that too finally faded, she rose and went to an upstairs window and looked down at the empty driveway.

Whatever had happened was over. So why did she feel it had just begun?

iii (#ulink_2642bfb3-8c8d-510c-a73f-736d87642bda)

memories are made of this (#ulink_2642bfb3-8c8d-510c-a73f-736d87642bda)

‘And you kneed him in the balls?’ said Detective Superintendent Andy Dalziel gleefully. ‘Well done, lass.’

‘Sure. Except they must have been made of brass,’ said Ellie, who was sitting sideways on a sofa with a large pack of frozen oven chips draped over her knee and a smaller pack of fish fingers pressed against her wrist. Having a non-gourmet kid sometimes came in useful. ‘Have they got hold of Peter yet?’

This was aimed at Detective Sergeant Edgar Wield who’d just entered the room, carrying a mobile phone.

‘No, but they’re still there, they’ve located the coach. I’ve sent Seymour down there. He’ll spot them eventually, but Tegley Hall Theme Park’s a big place. And you said you didn’t want him paged over the speakers.’

‘No,’ said Ellie firmly. ‘Softly, softly. I don’t want him getting the kind of shock I had.’

The two detectives exchanged glances, then Dalziel said, ‘Talking of which, lass, as you won’t let us take you to the quackery, I’ve got Wieldy here to organize the quack to come to you. And afore you start sounding off again, I reckon you could do with a bit more than fish and chips for them joints of yours. Also, I don’t like your colour.’

‘And I bet you’ve arrested people for less than that. Sorry, Andy. That was stupid. I’m still feeling so angry. As for my colour, you should have seen me half an hour ago. I was grey. Not as grey as that bastard, though, after I’d kneed him.’

‘Aye, that’s where we’d got to, wasn’t it?’

‘Second time round!’

‘Aye, well. You were a bit excitable, first time.’

‘Hysterical, you mean?’

‘Nay, lass. You know me, if I’d meant hysterical, I’d have said it. Wieldy, you’re lurking. Summat else?’

‘Checked with the Education Department. No one there called Westcombe or fitting the descriptions.’

‘Christ, you’re checking up on me!’ exclaimed Ellie angrily. ‘You think maybe I just lose it when I’m confronted by stupid officials? Well, you could be about to find out you’re right.’

Wield went on as if she hadn’t spoken. ‘The car’s number. How sure are you you got it right?’

‘As sure as I could be considering it was going through my mind these two wanted to abduct me in order to do God knows what to me. So if I got a figure wrong, it wouldn’t be surprising, would it? But it was definitely a dark-blue BMW, one of the big ones. Look, why’re you wasting time grilling me like this? I scribbled everything I could remember down soon as I could. Christ, I haven’t been married to the Force all these years without picking up some of your nasty habits. Why aren’t you out there looking for these people?’

‘You’d be surprised how often I get asked that question and I’ve not worked out a smart answer yet,’ said Dalziel. ‘Can’t even say it’s raining. Why’re you asking about the car, Wieldy?’

‘Did a check, sir. And according to Swansea, what Ellie gave us isn’t a number in use.’

‘False plates then,’ said Dalziel. ‘But try the obvious variations just in case.’

‘Yes, sir. By the way, phone wire was shorted with a pin where it goes into the hall window. Pull it out, it should be OK, but we won’t touch it till Forensic’s finished out there. Oh, and Novello’s here.’

‘Ivor? Good. Send her in.’

‘Hang about,’ said Ellie. ‘If you’re thinking I need a friendly female copper to unburden my heart to…’

‘Nay. I brought her for the strip search but I’ll do it if you like,’ said Dalziel.

Wield made for the door.

Ellie said, ‘Wieldy, sorry I snapped at you. I think I may still be a bit… excitable.’

The sergeant’s generally inscrutable features which, in Dalziel’s words, were knobbly enough to make a pineapple look like a pippin, smoothed momentarily into a warm smile, and he said, ‘I’ll let you know soon as we get a hold of Pete.’

‘By God,’ said Dalziel after the sergeant had gone. ‘Was that a smile, or has he got toothache? Nearest yon bugger ever came to cracking his face at me was the time I fell into the swimming pool at the mayor’s reception. Oh aye. I see you remember that too.’

A smile had touched Ellie’s lips, and she forced it to broaden as she saw the Fat Man observing her closely. Anything was better than having a womanly weep in front of Andy Dalziel. And even more, in front of Detective Constable Shirley Novello, who had just slipped into the room. Five-four, sturdy frame, minimum make-up, dark-brown hair neat but nothing fancy, baggy sweatshirt and matching slacks, she should have been two steps from invisible, which was presumably her intention. Down-dressing did not deceive Ellie Pascoe’s expert eye, however. She’d heard her husband talk a little too appreciatively of the girl’s professional qualities, and she saw the way even Fat Andy’s spirits perked up a notch or two at her entry. This was definitely one to watch.

‘You going to make an old man happy, lass?’ said Dalziel.

‘Don’t think so, sir. Just a first take on house-to-house. We’ve got two people who noticed the BMW. Confirmation of colour, but nothing extra on the numberplate. One of them thought it had an unusually long aerial compared with her husband’s car, which is the same model.’

‘Well-heeled neighbours you’ve got, Ellie,’ said the Fat Man. ‘Mebbe we’re paying Pete too much. That it, Ivor?’

‘Except for an old lady lives at the corner, towards town, that is, says she looked out to see what all the fuss was when she heard the sirens and saw a car doing a three-point turn and going back the way it came. Metallic-blue, sounds like a Golf. Driver looked swarthy and sinister, she says.’

‘Watch a lot of telly, does she? Ivor, it’s what happened before we came that I’m interested in. Afterwards, any poor sod driving along and seeing the street full of flashing fuzz is going to find another route, specially if he’s had a swift snort or two at a business meeting.’

The notion was suggestive. Ellie looked longingly at the bottle of Scotch which the Fat Man had dug out as soon as he arrived. At the time it had seemed virtuously sensible to quote what her first aid course said about avoiding alcohol in cases of shock, but now it seemed merely priggish.

She said, ‘OK, Andy. Let’s do it one more time. Then I don’t care if it brings on complete amnesia, I’m going to have that drink you prescribed.’

‘I’m feeling better already,’ said Dalziel. ‘No, Ivor, don’t sneak off. Got your short stubby pencil ready? I want you taking notes. Everything, not just what you think’s important, OK?’

‘Sir,’ said Novello.

Her eyes met Ellie Pascoe’s and she gave a little smile. All she got in return was a small frown. Confirming what she’d felt on their previous few meetings, that La Pascoe didn’t much like her. Couldn’t blame her, the WDC thought complacently. When I’m her age, I’ve no intention of liking good-looking women ten years my junior who work with my husband. Not that her own husband, if she ever bothered, would be anything like Chief Inspector Pascoe. It would probably be a comfort to Ellie Pascoe to know that her fantasies featured chunky, hairy men on surf-pounded beaches, not slim, nice-mannered introverts who would feel it necessary to buy you a decent French meal before checking into a good four-star hotel. But it was not a comfort she was about to offer.

The Great God Dalziel was speaking.

‘Right, lass. One more time. You were really taken in at first?’

‘Damn right I was. All I could think was, not again, oh God, it’s not all happening again. You know, Rosie in hospital, me camping out there, all the fears…’

The memory of that time was still so powerful, it had the therapeutic effect of reducing her present aftershock to manageable size, and she went on more strongly, ‘She’d only gone back to school for this final week before the summer hols… she insisted, and you know Rosie, when she makes up her mind…’

‘Can’t think who she takes after,’ said Dalziel. ‘Wanted to see all her mates, did she? And not miss this end-of-term outing.’

‘Both of those. Also to get out from under me, I suspect.’

‘Eh?’

Ellie said, ‘Andy, I’m ready for that drink now. Please.’

She took the proffered tumbler and said scornfully, ‘That wouldn’t drown a tall gnat. Cheers.’

It went down in one. Dalziel, who’d poured himself a good three inches, poured her another millimetre.

‘God Almighty, man! And it’s not even your whisky,’ she said.

‘Not my stomach either,’ said Dalziel. ‘You said something about Rosie getting out from under you. Never had you down as the clinging-mother type.’

‘No? Perhaps not.’

She brooded on this for a moment, glanced at Novello, then, with an effort at matter-of-factness, went on, ‘Since we got her back, after the meningitis, I’ve hardly been able to bear letting her out of my sight. She goes in the garden to play and two minutes later I have a panic attack. I think in the end I just began to get on her nerves, so school seemed a desirable alternative.’

‘Nay, you know what kids are like about missing things…’

‘The trip to Tegley Hall, you mean? Well, there’s another thing. They invite any parents who feel like giving a hand to go along. It’s a big responsibility, ferrying that number of kids around somewhere like that. I was going to go, but last night Rosie suddenly said, “Why can’t Daddy go? Miss Martindale says it doesn’t just have to be mummies.” Peter, bless his heart, said, why not? He’d like nothing better than a day in the company of his daughter and a hundred other kids. And he rang you and you kindly said that considering how hard you’d been working him for the past hundred years or so, he was long overdue a bit of time off…’

‘Don’t recollect them as my exact words,’ said Dalziel.

‘Peter is one of nature’s paraphrasers. So, nothing for me to do but say, “Great. It’ll give me the chance to get on with some work,” and smile through my tears.’

‘So you worried?’

‘Of course I worried. I worried about what kind of mother I was. And I worried about them out there in the big wide world without me to look after them. And I worried about myself for worrying about them!’

Plus the other worries she wasn’t about to air in front of Novello. Or Dalziel either, for that matter. Or indeed herself if she could help it. Worries like damp patches on a kitchen wall, that you could stand a chair in front of, or hang a wallchart over, or even just ignore, but you knew that sometime you were going to have to deal with them.

‘So I went upstairs, switched my laptop on and started working,’ she concluded.

‘That help with worries, does it?’ He sipped his Scotch and looked at her doubtfully.

Something else she wasn’t going to lay out in present company.

‘The poet Cowper managed to keep religious mania at bay for several decades by dint of writing,’ she said spiritedly.

‘God moves in a mysterious way His wonders to perform,’ said Dalziel, whose capacity to surprise should have ceased to surprise her. ‘Then the doorbell rang?’

‘No. I heard their car and spoke to them out of the window. Then I went downstairs and opened the door.’

‘Oh aye, you said. No print on the bellpush then. Pity.’

‘I’m sorry. I should have thought on.’

He smiled at her sarcasm, then said seriously, ‘When they mentioned Rosie, it must have been right bad.’

‘Bad? It felt like the bottom had fallen out of the universe. It was like getting the worst news you could imagine, and knowing it was all your own fault.’

She spoke with a vehemence which came close to being excessive.

‘All your fault? Nay, luv, can’t see how you could ever think that,’ he said, viewing her closely.

If Dalziel had been by himself, she might have stumbled into an explanation.

Maybe something like, I felt so relieved that morning not to be going with Rosie, to know she was in Peter’s care, to have a day at last when I could stop worrying about her. But not just for her sake, and not even because I could probably do with the rest myself, but because when we nearly lost her, I knew then what I must have known before but never had occasion to look straight in the eye, that my single-handed sailing days were over forever, that I’d been pressed as part of a three-man crew on a lifelong voyage over what were hopefully oceans of absolute love. Except if it’s so absolute, how come there’s a little part of me somewhere which, like Achilles’s heel, didn’t get submerged? Forgive me muddling my metaphors, it’s probably this story I’m writing. But that’s another story. No, what I’m trying to say is, no matter how I try to hide it from myself, there’s something in me that sometimes yearns to be free, that gets nostalgic for the long-lost days of free choice, that comes close to seeing this love I feel not as a gift but as a burden, not as a privilege but a responsibility. Perhaps I’m simply a selfish person who knows now she can never be selfish again. Does anyone else feel like this? Am I a monster? That’s why I was so ready to believe them, that’s why I felt so guilty. It was like God had decided I hadn’t got the message loud and clear last time and I needed another dose of the same to get me straight.

Something like that, maybe. But probably not, even if Novello and her little notebook hadn’t been there.

‘Just a figure of speech, Andy,’ she said.

‘So you’d have gone with this pair?’ asked the Fat Man.

‘Anywhere they wanted. If they’d kept it vague I’d have got in that car and…and what, Andy? What did they want with me?’

‘That’s for them to know and us to find out,’ said Dalziel. ‘So what put you onto them?’

‘I’ve told you!’

‘Aye, but telling’s like peeing to a man with a swollen prostate, you think you’ve got it all out but there’s often a bit more to come.’

‘Who speaks so well should never speak in vain,’ said Ellie. ‘OK. At first I couldn’t think of anything except Rosie being ill again. Then when they said about trying to contact Peter and being told he wasn’t available, I nearly said, of course he wasn’t available because he’s on the coach!’

‘But you didn’t? Why not?’

‘I don’t know. I reckon to start with it was just a case of being too shocked to speak, and that gave me time to think, I suppose. And suddenly it was like fireworks going off in my brain. I found myself thinking, it’s not just Jehovah’s Witnesses that don’t drive thirty thousand pound BMWs. I mean, I know the council tax has gone up, but surely the Education Department doesn’t kit its employees out like this? Sorry. It makes sense to me, I assure you. At the same time I registered that two or three times they said he when they were talking about the head at Edengrove. Now, one thing anyone in our local Ed Department will know is that the head of Edengrove is Miss Martindale. Not to know her argues yourself braindead. So I thought I’d just give them a little test. I made up a Mr Johnson as head teacher. And when they didn’t respond to that, I knew something very funny was going on.’

‘So you decided to assault them?’

‘No. I thought of challenging them, but there were two of them and only one of me and if their purpose was as nefarious as I was beginning to imagine, I didn’t like the odds. Time to retreat and lock the door, I thought.’

‘So what brought out the beast in you?’ asked Dalziel.

‘It was the man. The woman was trying to play it cool, very reassuring, nothing to worry about. She could probably see that I was already sick to guts with worry. But he decided that the more worried I got, the less trouble I’d be, and he said something about getting a move on just in case it turned out to be more serious than they thought. God, that really got to me. I thought, you callous bastard! The woman tried to calm things down, but it was too late. I was so angry that I must have been the best advert for gun control you ever saw. Because if I’d had one, I would have shot him, no problem.’

‘Not then,’ said Dalziel. ‘Might have had one now, but. On the other hand, we’d have had a body to work on. Nowt like a body when you’re short of a lead.’

‘Are you saying you’d rather I’d killed one of them?’

He considered.

‘No,’ he said finally. ‘Gets boring interrogating corpses. Serious wound, but, now that would have been nice. Something that would need hospital treatment. How hard did you say you kneed him?’

‘I shouldn’t think he’ll be troubling his wife for a few nights, but I doubt if he’d go for treatment.’

‘Wife? You reckon he was married?’ said Dalziel casually.

‘Well, he wore a big gold ring on his wedding finger… Andy, that was clever. I’d forgotten that. I mean, I didn’t think I’d noticed that.’

‘Not all rubber-truncheon work down the nick. Anything else come to mind, apart from what you scribbled down?’

He looked at the piece of paper Ellie had scribbled her notes on.

‘Man was six feet,’ he read. ‘About thirty – slim build – light-brown hair – bushy – needed a cut – left-hand parting – brown eyes, I think – not blue – squarish face – open honest expression – God the bastards were good!…’

He looked enquiringly at Ellie.

‘Yeah, sorry about that.’

‘Nay, it’s useful what you felt. By good, you mean…?’

‘Saying they were with the Education Welfare Service. That’s the council department that helps deal with problems like absenteeism, truancy, bullying, parental complaint, anything that a school finds it can’t cope with internally. But what I mean is, at first they came over perfect for it. Nice, caring, positive people…’

‘Bumbling do-gooders, you mean? Sorry. Just trying to put it in terms my lads would understand. Clothing – suit – Prince of Wales check – light-blue shirt – blue and yellow diagonal striped tie – could have been Old Boys or a club – on his feet dark-brown sandals…’

‘Did I put that? No, he was wearing a sort of soft leather moccasin, no laces, dark-tan, casual but elegant, in fact, they looked rather expensive, come to think of it. Which is what you’ve made me do, you cunning sod. I never mentioned sandals!’

Dalziel grinned.

‘No. You put nowt. But shoes are important. Change everything else, but you want your feet to stay comfy.’

‘So if he changes into something else because he’s worried that I can describe him, he might keep the same shoes on?’

‘Aye, but don’t get excited. Not the kind of info we pass on to Interpol. Voice – light-baritone range – Irish accent…’

‘No, that one’s not going to work, Andy,’ said Ellie firmly. ‘I said no distinguishable accent, and that’s what I mean.’

‘So not a Yorkshireman.’

‘Not like you, no.’

‘Not deep and musical then. But there’s all sorts of Yorkshire voices. There’s that high squeaky one, like yon journalist fellow who used to shovel shit for Maggie Thatcher. And there’s that one like a circular saw –’

‘No, not northern at all,’ interrupted Ellie.

‘So, not northern and not Irish. We’re getting somewhere. Scottish? Welsh? Cockney? The Queen? Michael Caine? Maurice Chevalier?’

‘You’re getting silly. No, he didn’t have any accent at all, really. Like an announcer on Radio Four.’

‘You think Radio Four announcers don’t have accents?’ said Dalziel. ‘No, hang about, I think I’m with you. It’s you you think doesn’t have an accent! What you mean is this guy spoke the same way you do? Middle-class posh, but not so much it gets up your nose.’

Ellie, faced as so often with a choice between laughing at Andy Dalziel or thumping him, decided she’d been involved in enough violence for the day and laughed.

‘Yes, I suppose that is what I do mean,’ she said.

‘Grand. Now the woman. How’s she for injury, by the way?’

‘She might have a black eye, and a few scratches,’ said Ellie, thinking affectionately of the Pompon de Paris. ‘Hey, and there could be a few threads from her dress hooked on the rose bush by the front door.’

‘We’ll check. So. Age thirties – five-eight or -nine – dark eyes – long face – not bad-looking – expensive make-up –what’s the difference between expensive and not so expensive?’

‘The more you pay, the less you see.’

‘Like sending your kids to public school. Hair black – natural – short – classy stylist – I won’t ask – build slim – good figure – there’s that good again. Know what I mean by good, but what’s it signify to you?’

Ellie threw an exasperated glance at Shirley Novello who returned it blankly.

‘Well, I’m sure that to you, Andy, a good figure suggests something like two footballs in a gunny bag, but what I mean is something you can see’s there but all in proportion, back, front, and middle, OK?’

‘Like you, you mean?’ said Dalziel, looking at her appreciatively. ‘In fact, sounds a lot like you, except mebbe for the expensive make-up. Joke. Now, clothing – olive-green cotton dress – sleeveless – leather shoulder bag – no stockings – pale-green sling-back shoes. Was she married?’

Ellie thought then said, ‘Yes, she was wearing a wedding ring. And she had a ring on her right-hand middle finger too. Green stone. Plus a wristwatch. Expanding bracelet, gold, I think. Sorry, I should have put that down.’

‘You’re doing fine. The watch on the same hand as the ring?’

‘Yes. The right. Hey, that means…’

‘She could be left-handed. That’s summat. Voice husky – accent Midlandish. Birmingham? Wolverhampton? Black Country?’

‘Any. It was just a patina, so to speak, not a full-blown accent.’

‘Might have made it to Radio Four, eh? Hello, here comes Smiler again.’

Wield had re-entered the room.