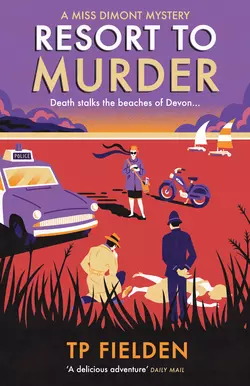

Resort to Murder: A must-read vintage crime mystery

TP Fielden

‘A fabulously satisfying addition to the canon of vintage crime’ DAILY EXPRESS‘One of the best in the genre’ THE SUN‘Tremendous fun’ THE INDEPENDENTNo 1 Ladies Detective Agency meets The Durrells in 1950s DevonDeath stalks the beaches of DevonWith its pale, aquamarine waters and golden sands, the shoreline at Temple Regis was a sight to behold. But when an unidentifiable body is found there one morning, the most beautiful beach in Devon is turned into a crime scene.For Miss Dimont – ferocious defender of free speech, champion of the truth and ace newspaperwoman for The Riviera Express – this is a case of paramount interest, and the perfect introduction for her young new recruit Valentine Waterford. Even if their meddling is to the immense irritation of local copper Inspector Topham…Soon Miss Dimont and Valentine are deep in investigation – why can nobody identify the body, and why does Topham suspect murder? And when a second death occurs, can the two possibly be connected?

PRAISE FOR TP FIELDEN (#ulink_c3df81b6-ae2e-51ef-ad87-46030f4add7a)

‘A fabulously satisfying addition to the canon of vintage crime’

Daily Express

‘Unashamedly cosy, with gentle humour and a pleasingly eccentric amateur sleuth’

The Guardian

‘Highly amusing’

Evening Standard

‘TP Fielden is a fabulous new voice and his dignified, clever heroine is a compelling new character’

Wendy Holden, Daily Mail

‘A golden age mystery’

Sunday Express

‘Tremendous fun’

The Independent

TP FIELDEN is a biographer, broadcaster and journalist. Resort to Murder is the second in the English Riviera Murders series featuring Miss Dimont.

For Laurel Wilson Voyager, forager

CONTENTS

Cover (#udaba1b94-6094-5019-93fb-c1d977e11d78)

Map (#u523fa4a4-3ad6-5808-8637-4bc8626bcced)

PRAISE FOR TP FIELDEN (#ulink_d3c3691e-da05-5774-9c8d-7297e2231419)

Title Page (#uac1603c3-dd5b-5072-b8fe-aac9624289b8)

About the Author (#u0bba4159-d678-5d6f-a840-bcd354e890d9)

Dedication (#u539b8502-e7ed-56ca-bf1d-3d2ef8f8937b)

ONE (#ulink_d50c2af2-e0e7-53ee-84ff-8a72ca85a3cb)

TWO (#ulink_d3a618e7-36df-5e98-880d-7fa1e52b9417)

THREE (#ulink_e68e0198-f096-53a0-92db-6bb0453bee9c)

FOUR (#ulink_6134f420-69cc-5ac1-8a98-41d35fa190ab)

FIVE (#ulink_6b55538b-41e7-53ff-824b-6321b12d53e4)

SIX (#ulink_bb3b97cd-6d40-5740-bb8f-4ec727e918dd)

SEVEN (#ulink_4abd52ff-f58f-515e-bd30-8f05e8e88c8e)

EIGHT (#litres_trial_promo)

NINE (#litres_trial_promo)

TEN (#litres_trial_promo)

ELEVEN (#litres_trial_promo)

TWELVE (#litres_trial_promo)

THIRTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

FOURTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

FIFTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

SIXTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

SEVENTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

EIGHTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

NINETEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY-ONE (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY-TWO (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY-THREE (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY-FOUR (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY-FIVE (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY-SIX (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY-SEVEN (#litres_trial_promo)

Extract (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

ONE (#ulink_ff0a57e5-d1a2-5032-a26e-144ee9f64be5)

Pale aquamarine and milky like the waters of Venice, the sea moved slowly inland. The shoreline at Todhempstead welcomed the advance reluctantly, giving up its golden sands inch by inch, unwilling to concede a single yard of the most beautiful beach.

The body lay some way distant from the incoming tide, but sooner or later it would have to be moved.

For the moment, though, it lay there, surrounded by a frozen tableau – a small group of people immobilised by what lay at their feet. Death changes behaviour patterns, imposes a protocol of its own.

She was young, she was blonde, and she may have been pretty but for the hideous open wound that claimed half her face. Her dress was glamorous in an inexpensive sort of way, arranged around her decorously enough. It was still dry, a sure indicator it had not been here too long.

Frank Topham looked down with some discomfort. The long shallow beach had at its furthest end a high embankment, surely too far away for the victim to have fallen from and landed here. The injuries which claimed her life were too severe – that much was evident – for her to have walked or crawled to her final resting place, yet there were no footprints around the body apart from those made sparingly by the small group of eyewitnesses.

Nor was there any blood.

These contradictions jarred Inspector Topham’s usually tranquil state of mind, but were swept aside for the moment as he looked down on the wretched girl.

‘Twenty, I should say,’ he murmured to the two faceless acolytes standing at his shoulder.

‘No shoes,’ said one.

‘No handbag,’ replied Topham.

The other lit a cigarette and looked up at the sky. He didn’t seem terribly interested.

Whatever passed next between these custodians of the peace was drowned by the arrival of the up train from Exbridge, a billowing, grunting triumph of the steam engineer’s art, slowing as it made its long approach into Todhempstead Spa station.

‘Better get her away,’ Topham said to the police doctor. The man on his knees looked over his shoulder at the advancing waves and nodded.

‘No evidence,’ said Topham wretchedly. ‘No clues. We’re moving the body and there’s no clues.’

Taking his cue, the second man moved vaguely away and came back. ‘Tizer bottle.’

‘Is the label wet?’ asked Topham without even looking at it.

‘Yer.’

‘Chuck it,’ snapped the inspector. ‘No use to us.’

He moved swiftly off to the slipway where the car was parked, not wanting the men to see his face. There had been too many deaths back in the War, but wasn’t that why he had fought? So there wouldn’t be any more? It was a man’s job to die, not a woman’s.

For a moment he turned to look back at the scene below. The dead body claimed his focus, but, beyond, it was as if nobody cared that the world had lost a soul this morning. In the distance two sand-yachts raced each other across the broad beach, and overhead an ancient biplane trailed a long banner flapping from its tail. Smith’s Crisps, according to its message, gave you a wholesome happy holiday.

Far in the distance he could see a solitary female figure, dressed in rainbow colours, standing perfectly still and looking out to sea as if what it had to offer was somehow more interesting than a dead body. It was as if nobody cared.

Inspector Topham got in the car and pulled out on to the empty road. He reached Todhempstead Spa station in a matter of minutes, but already the Riviera Express was pulling out, heading on towards Exeter at a slow roll – huffing, grinding, thumping, clanging. He could get it stopped at Newton Abbot to check if there was evidence on the front buffers of contact with human flesh from the downward journey, to quiz the train guard and the driver. But they’d all be back again this afternoon on the return trip, and he doubted, given the distance of the body from the railway embankment, that this was a rail fatality. Though, with death, you could never be sure about anything.

As he drove back to the Sands, his eyes lifted for a moment from the road ahead. It was already mid-June and the lanes running parallel to the beach were bursting with joy at summer’s arrival. Though the bluebells and primroses had retreated, the hedgerows were noisy with young blackbirds testing their beautiful voices, while, beneath, newly arrived wild roses and cow parsley reached out, begging to be noticed.

How, asked the policeman, could anyone wish a young girl dead at this season, when hope is in the air and the breeze is scented with promise? His years in the desert, those arid wastes of death, might be long behind but still they cast their shadow. He drove down the slipway on to the beach, got slowly out, and nodded to his men.

‘Body away,’ said one.

‘Come on then.’

Topham removed his hat and got back in the car. His square head, doughty and in its own way distinguished, grazed the ceiling because of his ramrod-straight back. Despite the rising heat he still wore the raincoat he’d donned in the early morning when he got the call. He’d been too distracted by what he’d seen to take it off.

Too honest a man, too upright, perhaps too regimented in his thinking to see life the way criminals do, Frank Topham was both the very best of British policing and, some might argue, the worst. There was a dead woman on the beach, but if it was murder – if – the culprit might never be caught. No clues, no arrest.

No hope of an arrest.

The car approached Temple Regis, the prettiest town in the whole of Devon, and, as the inspector drove up Cable Street and over Tuppenny Row, his eyes took solace in the elegant terrace of Regency cottages whose pink brickwork blushed in the summer sunshine. Further down the hill he could hear the clanking arrival of the 10.30 from Paddington, its sooty steamy clouds shooting upwards from Regis Junction station. Life was carrying on as if nothing had happened.

Topham entered the police station at his regulation quick-march. The front office was empty apart from the desk sergeant.

‘Frank.’

‘Bert.’

‘Anything for the book?’ The sergeant had his pen poised.

Topham hesitated. ‘Accidental. Woman on T’emstead Beach.’

The other man gazed shrewdly at him. ‘You sure? Accidental?’

Topham returned his gaze evenly. ‘Accidental.’ He tried to make it sound as though he believed it.

‘Only I got a reporter in the interview room. Saying murder.’

‘Reporter?’ barked Topham nastily. ‘Saying murder? Not – not that Miss Dimont?’

‘Nah,’ said Sergeant Gull. ‘This ’un’s new. A kid.’

Topham’s features turned to granite at the mention of the press. Though Temple Regis boasted only one newspaper, it somehow managed to cause a disproportionate amount of grief to those police officers seeking to uphold the law. Questions, questions – always questions, whether it was a cycling without lights case or that unpleasant business with the curate of St Cuthbert’s. As for Miss Dimont …

To Frank Topham’s mind – and in the opinion of many other Temple Regents too – the local rag was there to report the facts, not to ask questions. So often the stories they printed showed a side to the town which did little to enhance its reputation. What good did it do to make headlines out of the goings-on the Magistrates’ Court? Or ask questions about poorly paid council officials who enjoyed elaborate and expensive holidays?

And how they got on to things so quickly, he never knew. What was this reporter doing asking questions about a murder? It was only a couple of hours ago he himself had clapped eyes on the corpse – how had word spread so fast?

‘So,’ said Sergeant Gull, picking up his pencil and scratching his ear with it, ‘the book, Frank. Murder or accidental?’

‘Like I said,’ snarled his superior officer, and strode into the interview room.

You can be the greatest reporter in the world but you are no reporter at all if people don’t tell you things. A dead body on the beach is all very well but if you’re out shopping, how are you supposed to know?

In fact Miss Judy Dimont, ferocious defender of free speech, champion of the truth and the thorn in the side of poor Inspector Topham, hardly looked like Temple Regis’ ace newspaperwoman this afternoon. As she ordered a pound of apples in the Home and Colonial Stores in Fore Street she might easily be mistaken for a librarian on her tea break: the sensible shoes, the well-worn raincoat and the raffia handbag made it clear that here was a no-nonsense, serious person who had just enough time to stock up on the essentials before heading home to a good book.

‘One and sixpence, thank you, miss.’

The reporter reached for her purse, smiled up at the young shop assistant, and suddenly she looked anything but ordinary. Her wonderfully erratic corkscrew hair fell back from her face and her sage-grey eyes peeped over the top of her spectacles, which had slithered down her convex nose. The smile itself was joyous and radiant – the sort of smile that offers hope and comfort in a troubled world.

‘Tea?’

‘Not today thank you, Victor.’ She didn’t like to say she preferred to buy her tea at Lipton’s round the corner. ‘I think I’ll just quickly go over and get some fish.’

‘Ah yes.’ The assistant nodded knowledgeably. ‘Mulligatawny.’

This was how it was in Temple Regis. People knew the name of your cat and would ask after his health. They knew you bought your tea at Lipton’s and only gently tried to persuade you to purchase their own brand. They delivered the groceries by bicycle to your door and left a little extra gift in the cardboard box knowing the pleasure it would bring.

‘I tried that ginger marmalade,’ said Miss Dimont, with perfect timing. ‘Delicious! In fact it’s all gone. May I buy some if you have any left?’

The assistant in his long white apron hastened away and, as she wandered over to the marble-topped fish counter, she marvelled again at the interlocking cogwheels which made up Temple Regis’ small population. Over by the coffee counter the odd little lady from the hairdresser’s was deep in conversation with the secretary of the Mothers’ Union in that old toque hat she always wore, winter and summer. Both were looking out of the window at a pair of dray horses from Gardner’s brewery, their brasses glinting in the late sunlight as they plodded massively by.

They’d all meet again at the Church Fete on Saturday, bringing fresh news of their doings to share and deliberate upon. While the rest of Britain struggled with its post-war identity crisis – move forward to the brave new world? Or go back to the comfortable past? – life in Devon’s prettiest town found its stability in the little things of here and now.

‘Do you have any cods’ heads? If not, some coley? And a kipper for me, please,’ just in case anybody should think she was reduced to making fish soup for herself, delicious though that would be!

It had been a perplexing day, and the circular rhythms of the Home and Colonial had a way of putting everything back in perspective. The Magistrates’ Court, the one fixed point in her week which always guaranteed to provide a selection of golden nuggets for the front page of the Riviera Express, had failed her – and badly. Quite a lot of time today had been taken up with the elaborate appointment of a new Chairman of the Bench, and that had been followed by a dreary case involving the manager of the Midland Bank and a missing cheque.

It shouldn’t have come to court – everyone has the occasional lapse! – and under the previous chairman the case would have been thrown out. But the Hon. Mrs Marchbank was no longer with us, her recent misdeeds having taken her to a greater judge, and in her place was the pettifogging Colonel de Saumarez, distinguished enough in his tweed suit but lacking in grey matter.

‘Anything else, miss?’

‘That’s all, thank you.’

‘Put on your account?’

‘Yes please.’

‘Young Walter will have it round to your door first thing.’

‘I’ll take the fish with me, if I may.’

The world is a terrible place, thought Miss Dimont, as she emerged into the early evening sunlight, what with the Atom Bomb and the Suez Crisis, but not here. She waved to Lovely Mary, the proprietress of the Signal Box Café, who was coming out of Lipton’s with a wide smile on her lips – how aptly she was named!

‘All well, Judy?’

‘Couldn’t be better, Mary. Early start tomorrow though, off before dawn. A life on the ocean wave, tra-la!’’

‘See you soon, then, dear. Safe journey, wherever you’m goin’.’

Miss Dimont walked down to the seafront for one last look at the waves. After the kipper, she would sit with Mulligatawny on her lap and think about the bank manager and the missing cheque. It had been a long day in court and she needed a quiet moment to think how best the story could be written up.

Things were less tranquil back at her place of work, the Riviera Express.

‘What about this murder?’ roared John Ross, the red-faced chief sub-editor. It was the end of the day, the traditional time for losing his temper. He stalked down the office to the reporters’ desks. ‘Who’s on it? What’s happening?’

Betty Featherstone clacked smartly over from the picture desk in her high heels. She was looking particularly radiant today though the hair bleach hadn’t worked quite so well this time, and her choice of lipstick was, as usual, at odds with the shade of her home-made dress. The way she carried a notebook, though, had a certain attraction to the older man.

Betty was the Express’s number two reporter though you wouldn’t know that if you read the paper – her name appeared over more stories, and in larger print, than Judy Dimont’s ever did, but that was less to do with her journalistic skills than with the fact that the editor liked the way she did what she was told.

You could never say that about Miss Dimont.

‘Who’s covering the murder?’ demanded Ross heatedly.

‘The new boy,’ sighed Betty.

The way she said it carried a wealth of meaning in an office that was accustomed to the constant stream of new talent washing through its revolving doors – in, and then out again. Either they were so good they were snapped up by livelier papers, or else they were useless and posted to a district office, never to be seen again.

‘Another rookie?’ snapped Ross, the venom in his voice sufficient to quell a native uprising. ‘When did he arrive?’

‘This morning,’ said Betty. She’d yet to try out her charms on the newcomer, but as ever she was willing to give it a try – he looked rather sweet, though of course those nasty photographers would be calling her a cradle-snatcher again.

‘Where’s your Townswomen’s Guild story?’ growled Ross, for Betty was not his cup of tea and her bouncy figure left him unmoved.

‘Here you are,’ she trilled, handing over three half-sheets of copy paper bearing all the hallmarks of an afternoon’s attention to the nail-varnish bottle.

‘A stimulating talk was given by Miss A. de Mauny at Temple Regis TWG on Tuesday,’ it began, one might almost say deliberately masking the joys ahead.

‘Titled Lady Rhondda and the Six Point Group it gave a fascinating account of the post-war women’s movement, taking in the …’

She could see Ross’s eyes glaze over as he read on. In truth, she’d found it difficult herself to stay awake during the earnest but dense peroration by the town’s only clock-mender. There weren’t too many jokes in her talk.

‘For … pity’s … sake …’ groaned Ross, a man ever-hungry for sensation. ‘We’re short on space this week. The Six Point Group? Naaaah!’

‘Husbands of TWG members advertise extensively in this newspaper,’ said Betty, primly parroting the words of her editor when she’d protested at having to attend the dreary event.

‘I’ll have to cut it.’

‘Do what you like,’ said Betty. Her mind was already on the evening ahead. A drink perhaps with that new reporter, the start of something new?

And maybe, this time, it could be for ever?

TWO (#ulink_7fd1b120-ef9f-50eb-85db-5e0219f5dcfd)

Miss Dimont sat in the public bar of the Old Jawbones, a beaker of rum on the stool in front of her, surrounded by a group of men – bulky, muscular, unshaven and with the occasional missing tooth – who roared their approval as she raised the glass to her lips and drank.

It was 10 o’clock in the morning.

This scene of depravity had an explanation but not one that could ever find the approval of her editor, the fastidious Rudyard Rhys. A stickler for decorum among his staff, he would shudder at the thought of his chief reporter behaving in so abandoned a fashion. In a filthy old fishermen’s pub! At ten o’clock in the morning!

Miss Dimont didn’t care. She shot a waspish remark at her fellow-drinkers and they burst once more into laughter. One more swig of rum and then, picking up her notebook, she moved slowly and almost steadily towards the door.

‘Whoops-a-daisy, Miss Dimmum!’

‘Don’t you fall down now, Miss Dimmalum!’

‘And doan fergit y’r turbot!’

The Jawbones was unused to entertaining female company at this hour, reserving its best seats for the men who filled their nets quickly and sneaked back into harbour for a quick one before breakfast. But there she was, a beauty in a haphazard sort of way, with her grey eyes, convex nose, beautiful smile and unmanageable corkscrew curls. The fishermen liked what they saw.

Miss Dimont emerged onto the street and took a deep breath of the fishy, salty air. Across the quay lay the rusty beaten-up old fishing vessel which had so recently put her life in peril. The memory made her sit down quite sharply.

‘Awright, missus?’ A handsome old seadog in faded blue overalls and battered cap came over and settled himself next to her.

His countenance was like a road map, all lines and detours, and his hands were ingrained with dirt. But he had charm – not like those men she encountered when she arrived before dawn to join the Lass O’Doune. She thought she’d never met such a band of brigands, strangers to the scrubbing brush and razor alike, unfamiliar with the finer points of etiquette.

By the end of her treacherous journey, though, they had acquired other attributes – they had become handsome. They had become warm, and kind. And they were undoubtedly heroes.

But it had not started well. ‘We were tol’ to expect a reporter,’ said the captain, Cran Conybeer, eyeing her with disfavour in the predawn darkness.

‘I am a reporter,’ snapped Miss Dimont, pushing her spectacles up her rain-spattered nose and standing ever so slightly up on her toes.

Captain Conybeer wasn’t listening. ‘We don’t ’ave wimmin aboard,’ he said firmly. ‘Send a reporter an’ we’ll take ’un out.’

Miss Dimont had experienced worse rebuffs. ‘You’ve just won the Small Trawler of the Year Award,’ she said, her words almost lost by the screeching of the davits as they hauled the nets up. ‘You’re the first Devon crew ever to win it. My newspaper has reserved two whole pages to celebrate your courage and skill, to tell Temple Regis how brilliant you are and – just as important, I’d have thought – to let your competitors know how much better you are at the job than they are.’

This last point hit home, but even so the captain remained reluctant.

‘Yers but …’

‘The article has to be written by the end of the day if it’s to get into next week’s newspaper. It’s 4.30 in the morning and there is no other reporter available to come with you on this trip.’

‘We doan allow wimmin.’

Miss Dimont slowly pushed back her hair and looked up into the captain’s wrinkled eyes, sparkling in the gas lamp which illuminated the ship’s bridge.

‘Perhaps this will help,’ she added quietly. ‘I was an officer in the Royal Navy – the Wrens, you would call it. I served my country and I served the sea.’

This last bit was not strictly accurate but it was enough for the wavering Conybeer.

‘Come on then, overalls on, we’m late as ’tis.’

And so, before the dawn light rose, the Lass O’Doune set out down the estuary and straight into a force nine gale – unseasonable in June, but that is the sea. The next four hours were a terrifying combination of chaos and noise, of unforgiving waves crashing across the decks and the ocean rampageously seeking the lives of those who sought to draw nourishment from it. Clad, pointlessly, in hooded oilskins – the sea had a way of finding its way underneath the stoutest protection within minutes – the men fought nature valiantly as they reeled in the nets and deposited their wriggling silvery spoils on the deck.

Fearless under fire, thought Miss Dimont, as she clung uncertainly to a rail inside the bridge – like soldiers in battle. Then, shouting to the captain, she weaved her way towards the deck so she could experience at first hand what his men had to do to make their living.

With a lifeline attached to her waist, she stepped out into the roaring, rushing hell and hauled on the nets alongside the other men. The job was not difficult, she discovered, it just required nerve and strength.

Arranged as a special demonstration for the press, the voyage out into the ocean lasted a mere three hours, though to Miss Dimont it seemed like four days. No wonder she’d found herself in the snug of the Old Jawbones with a jigger of rum in front of her!

And now, the battle done, she sat outside on a bench taking in the sun while Old Jacky shared his thoughts with her.

‘Just goin’ on me ’olidays,’ he was saying.

‘Oh,’ said Miss Dimont, rallying. ‘Anywhere nice?’

‘Down ’oo Spain,’ said Jacky. ‘See if I can get some deckhand work.’

‘You mean – you fish all year, then when you go on holiday … you fish?’

The wrinkled old sailor smiled at her and shifted his cap. ‘’Bout right.’

Just then Cran Conybeer came out of the Jawbones and saw his most recent crew member marooned on her bench.

‘Lan’lubber,’ he said, laughing. ‘You carn walk, can you?’ ‘Of course I can,’ said Miss Dimont in her peppery voice, rising unsteadily to her feet.

‘You come along a me,’ said the captain, hoisting Miss Dimont up gently and putting his arm through hers. ‘You come along a me, I’ll make sure you’re safe.’

At the landward end of the pier at Temple Regis stood the Pavilion Theatre, a crumbling structure with precious little life left in it whichever way you looked at it. If there was one thing the town cried out for it was a cultural centre where visitors could congregate at the end of an exhausting day’s holidaymaking to be entertained and where locals, too, could pick up some crumbs of artistic comfort at the bookends of the season. This was not it.

For years the Pavilion had been run – first successfully, then gradually less so – by Raymond Cattermole, a former actor. Occasionally, a star from London would descend for a short season in support of their old friend, but Cattermole’s homegrown fare was proving less appetising as the years went by. He looked for comfort to his current squeeze, Geraldine Phipps, and sometimes beyond – for after a lifetime of ups and downs on the stage the old Gaiety Girl would rather have a glass of gin than a spot of pillow talk. And so, after a particularly disastrous performance of his one-man show My West End Life, the actor-manager came to the conclusion there was no point in sharing his genius with the oafs in the one-and-thruppennies, and for some days now his doors had been shut.

This afternoon, however, a side door creaked open a crack and from within came a rasping but cultured voice.

‘Come in, dear. Mind the rubbish.’

The young man mooched down the long corridor towards the large back room which, though lacking home comforts, had at least the consolation of a bottle of Plymouth gin.

Mrs Phipps, who had commandeered the only glass, swilled out a mug under the cold tap and placed it before her guest. ‘Pour away to your heart’s content. He left a crate of it behind.’

Her guest made himself a cup of tea.

‘So tell me again, dear, what are they called?’

‘Danny Trouble. And The Urge.’

The ancient Mrs Phipps blenched. ‘Are you sure?’ She lit a Navy Cut and her hands shook slightly as she did so.

‘They’re cool,’ said her grandson. ‘Just what’s needed in a dead-and-alive hole like this.’

‘You know,’ said Mrs Phipps sourly – the gin had not yet mellowed the edges – ‘I learned what entertainment was more than half a century ago, but from what you tell me these young men are far from entertaining, just rude. I’ve seen their sort on TV – no finesse, no culture, no style. They may look sweet onstage in their matching suits and their shiny guitars but from the way they curl their lips and waggle about I’d say they neither seek the adulation of their audience, nor do they even try to charm them.’

‘That’s the point!’ exclaimed Gavin Armstrong. ‘It’s the love-’em-and-leave-’em principle. The girls adore it.’ Mrs Phipps took refuge in the gin.

‘You should see them – they’re positively electric! Onstage it’s like November the Fifth and the 1812 Overture all rolled into one.’

‘There’s another thing,’ said Mrs Phipps sharply, ‘the electricity. They all have these electric guitars, don’t they? That must use up an awful lot of juice. What I need to do here now Ray’s hopped it is get costs down and …’

‘What you need is The Urge, Granny.’

‘What I need, Gavin,’ continued Mrs Phipps, who in her time had experienced more urges than her grandson could possibly imagine, ‘what I need to do is keep this theatre open – and to do that I’ve got to find an act which is cheap and a guaranteed box-office success. Not something that’s going to eat up the profits with sky-high electric bills and frighten the locals away at the same time.’

‘They won’t need all those spotlights you’ve got. They don’t need a stage set. They don’t need make-up – though one or two could do to cover up their spots, I’ll admit – and the last thing they need is people ushering the punters into their seats. In fact the fans’d probably tear out the seats if they did.’

‘Disgusting,’ spat Mrs Phipps, pouring herself another. ‘Nothing but louts and Teddy boys. Don’t you see what people want on a nice night out? They want glamour, they want to be carried away on wings of song.’

‘No they don’t, Gran. These days what they want is deafening noise.’

Mrs Phipps shuddered. ‘To think we fought our way through two wars to end up like this,’ she said. ‘Once upon a time and not so long ago, gentlemen would wait at the stage door of the Adelphi with a gardenia, a bottle of perfume and a taxi waiting to whisk me off to supper at the Café Royal.’

‘Darling thing,’ sighed Gavin, ‘the days of the Gaiety Girl are long gone. The war’s been over for an age, and there’s a whole new generation that wants something different, something original. Danny Trouble and The Urge are it.’

‘They’re noisy and uncouth,’ said Mrs Phipps, who had no idea whether they were or not.

‘They’re definitely that all right,’ said Gavin, with pride.

‘But what will the townsfolk say? The council? The press?’

‘Ah,’ said Gavin, a wily smile on his lips, ‘you can’t fail with the press. They’ll have to write about them, one way or the other. That’s guaranteed! Either it’ll be “Disgrace to Temple Regis” or else “Britain’s Top Beat Group Come to Town”, and hopefully both. The theatre will be full. Every night.’

‘No,’ said Mrs Phipps, exhaling a hefty cloud of nicotine, ‘no, Gavin. It really won’t do.’

‘It’s the new religion!’

‘Then you’re a poor missionary, and I am no convert,’ said Mrs Phipps, absently peering into her glass.

‘Look,’ said Gavin, ‘we both have an opportunity here, Granny. Raymond’s scarpered and you don’t know when or if he’ll be back …’

‘Oh, he’ll be back,’ said Mrs Phipps, ‘he can’t live without me.’

‘You didn’t say that last time he ran off with Suki Raffray.’

‘Don’t mention that Jezebel’s name!’ screeched Mrs Phipps. It had been an ugly business.

‘You don’t know when or if he’ll be back,’ repeated Gavin, seizing his moment. ‘The theatre has to open for the new season next week – what are you planning to put on? I’ve got Danny and the lads on a contract until the end of the year, but that’s all. They’ve just had their first Number One and pretty soon some manager will come along who knows what they’re doing, and that’ll be curtains for me.

‘Bringing them down here, they’ll be the first beat group ever to do a summer residency in a British seaside resort. That’ll give them headlines, it’ll give Temple Regis headlines, and people will come flocking to this …’ he paused, searching sarcastically for the word ‘. . . er, delightful town.’

‘Plus,’ he added ingratiatingly. ‘you can pay them less than you paid Alma Cogan last year. They’d have a regular income, and I’d get paid.’

Mrs Phipps looked across at her grandson and shook her head. ‘You father had such hopes for you, Gavin. The Brigade … maybe the Foreign Office afterwards …’ She sighed. ‘But since you ask, what I had in mind was Sidney Torch and his Light Orchestra. I know Sidney, and he’d come down here for me in an instant, I feel sure of that. They have such beguiling music, darling, just the sort of thing to attract the traditional holidaymaker. He came down here once before, years ago, and you know, they even got up in the aisles and danced!’

‘With Danny Trouble they’ll never sit down,’ said Gavin tartly. ‘What this place desperately needs is something for the younger crowd.

‘You know, Granny’ he went on, ‘this is 1959 – people don’t want to dance cheek to cheek any more, they want rock and roll!’

‘I suppose you may be right,’ conceded his grandmother, who was becoming alarmed at the prospect of having to confess to Temple Regis that the Pavilion Theatre would remain dark through the summer season. ‘We do need something new. People got fed up with Arthur doing his West End Life – that’s why he ran away, you know. They got up and started catcalling.’

‘It wasn’t Suki Raffray, then? Why he ran away?’

‘IT WAS NOT SUKI RAFFRAY!’ shouted Mrs Phipps. ‘Don’t mention that name again!’

‘Then you agree, Granny? That Danny and the boys can come for the six-week season?’

‘What else can I do?’ said Mrs Phipps, shaking her head so hard her fine silvery hair escaped its pinnings. ‘I have no alternative.’

‘You won’t regret it, Gran.’

Mrs Phipps shuddered as she reached again for Plymouth’s most famous export.

‘I feel as though someone just walked over my grave,’ she said.

THREE (#ulink_7f69e0d3-b33d-52ae-b09b-90c0a56e33fc)

The atmosphere in the editor’s office at the Riviera Express was as it always was – dusty – but the moment the newspaper’s chief reporter walked in it got dustier.

Judy Dimont was everything an editor could wish for – a brilliant mind, a dazzling shorthand note and charm enough to entice whole flocks from the trees. Yet, as Rudyard Rhys raised his eyes from the task in hand, a particularly recalcitrant briar pipe, he could see none of this. Before him stood a striking woman of indeterminate age dressed vaguely in a macintosh with its belt pulled tight at the waist, and with a waft of corkscrew curls slipping joyously from the restraints of a silk scarf. A faint scent of rum entered the room with her.

‘Got the fishermen,’ said Judy Dimont, a trifle dreamily. ‘What extraordinary men they are! Why, do you know …’

‘Rr … rrrr,’ growled her editor, whether by way of approval or dissent it was hard to tell, but enough to douse Miss Dimont’s tribute to those in peril on the sea.

Rhys returned to his pipe. ‘There was a murder while you were out on your jolly boating trip,’ he said, a nasty edge to his voice. ‘As my chief reporter I should have liked you there.’

‘There was a force nine out beyond the headland,’ said Miss Dimont, not a little proud of her early morning exploits. ‘Rather difficult to spot a murder from there. Anyway, who …’

‘Had to send him,’ said Rhys, nodding towards a corner of the room. A young man half rose from his seat and, with a slight smile, gently inclined his head. In a second the chief reporter had it summed up – wet-behind-the-ears recruit, probably the son of a friend of the managing director, going to be useless, a dead weight, another failed experiment in attracting the nation’s young talent into local journalism.

Miss Dimont was not without prejudice but in general she was kind. She did not feel kind this morning.

‘Well then, let him write it up,’ she said, eyeing not without prejudice the item which hung round his neck and which looked suspiciously like an old school tie. ‘I’ve got this feature to write and then, if it’s OK with you, Mr Rhys, I’m going home. I was up at three this morning to catch the tide.’

For a man who once had worn Royal Navy uniform himself, Rhys showed a surprising lack of interest over the vicissitudes of the ocean. ‘Give him a hand,’ he ordered, and dismissed them both with the swish of a damp page-proof.

Pushing up the spectacles which adorned her glorious nose, Miss Dimont stepped, with an audible sigh, out into the corridor. The last thing she wanted – another trainee reporter dumped on her!

‘Have you found yourself a desk?’ she inquired shortly, not even bothering to look over her shoulder as she strode into the newsroom.

‘They … they told me to sit opposite you,’ said the young man. ‘The other lady, er …’

‘Betty.’

‘Yes, Betty’s … um … I think she’s … er, not quite sure. I think she’s been sent elsewhere.’ The words seemed hesitant but he appeared pretty self-assured. ‘Newbury something.’

‘Newton Abbot?’ she said.

‘That’s about the size of it,’ said the young man. ‘She didn’t seem too happy.’

This did not please Miss Dimont one bit. Betty Featherstone was effectively her number two and, though uninspired, was a useful reporter who did her share of filling the copious news pages which made up the weekly digest of events in Devon’s prettiest town. Having her dispatched to the district office was a blow. It would increase the chief reporter’s workload and, at the same time, require her to shepherd this innocent lamb through his first weeks on the paper until he got the hang of it.

Or disappeared.

The young man sat down opposite her. ‘Erm, we haven’t been introduced. Valentine is the name.’

‘Judy Dimont, Mr Valentine. Welcome to the Riviera Express.’ The words didn’t have quite the cheery ring they might, but then she was not used to rum for breakfast. She felt tired and wanted to go home to Mulligatawny.

‘Er, Valentine’s the first name,’ the boy said.

‘Surname?’

‘Waterford.’

‘Well, that’ll look pretty as a front-page byline,’ she said, not entirely kindly. ‘Raise the tone a bit.’

‘I was thinking of shortening it to Ford. It’s a bit of a mouthful,’ he said apologetically.

‘Well, you won’t need to do anything with it if you don’t write up your murder,’ said Miss Dimont crisply. ‘No story, no byline. You do know what a byline is?’

‘Window dressing,’ said Waterford. ‘For the reporter, it’s compensation for not being paid properly. A bun to the starving bear.’

His words caused Miss Dimont to look at him again. Could, for once, the management have recruited some young cannon fodder who actually had a few brains?

‘Makes the page look nice, makes the reading public think they know who wrote the story,’ he went on, smiling. ‘A byline makes everybody happy.’

Good Lord, thought Miss Dimont, her head clearing rapidly. He’s what, twenty-two? Obviously just finished National Service. How come he knows so much about journalism?

‘How come you seem to know so much about …’

‘Uncle in the business,’ said Valentine, looking with unease at the large Remington Standard typewriter in front of him. He carefully folded a sheet of copy paper into the machine, took out a brand-new notebook and started to tap. Very slowly.

Obviously he does not need my help, thought Miss Dimont, and set about her own preparations to bring to life the world of Cran Conybeer and his lion-hearted friends.

Just then Betty Featherstone wafted by, attracted by the mop of tousled hair atop Valentine Waterford’s handsome young head. Despite her marching orders she was evidently in no hurry to catch the bus to Newton Abbot.

It was a sight to behold when Miss Dimont got to work. She hunched over her Quiet-Riter and the words just flowed from her flying fingers. Her corkscrew hair wobbled from side to side, her right hand turned the pages of the notebook while the left continued to tap away, and her lovely features sometimes pinched into an unattractive scowl when she found herself momentarily lost for a word or phrase. But as the paper in her typewriter smoothly ratcheted up, line by line, the story of the extraordinary events of her pre-dawn foray in the English Channel came gracefully to life.

‘. . . single?’ Betty was saying, adjusting the broad belt which held in her billowing skirt – how lovely he looked with his slim figure, borrowed suit and polished shoes! She was not one to waste time on irrelevancies.

‘Been in the Army,’ said the young man, ‘not much time for all that.’ It was clear to Miss Dimont, though not to Betty, that this was not the moment to turn on her headlights.

‘Can I help?’ Judy interrupted, nodding Betty away.

‘Matter of nomenclature,’ said Valentine.

‘What’s the difficulty?’

‘It’s supposed to be a murder. But it’s an accidental death. Though it could be a murder,’ he said. He went on to explain his arrival at Temple Regis Police Station, his briefing by the ever-garrulous Sergeant Gull (murder) followed by a second briefing by the taciturn Topham (accidental).

‘Which do I call it? Murder? Or accidental?’

‘Well, just wait a minute now,’ said Miss Dimont, suddenly very interested. ‘Who is it who’s supposed to have been murdered?’ She had, after all, some experience in such matters.

‘Young lady, possibly early twenties. Bad head injuries, found in the middle of a big wide beach.’

This sounded very odd.

‘Mystery death,’ ordered Miss Dimont crisply. ‘If even the police can’t find the word for it, then it’s a mystery. Tell me more.’

Waterford described the discovery of the body, details kindly supplied by Sergeant Gull. Then he reported the deliberate downplaying by Inspector Topham: ‘Rather angry about it he was, actually. Reminded me of my sergeant-major.’

‘He was a sergeant-major.’

‘That would explain it.’

‘When’s the inquest?’ ‘Inquest?’

He’s rather sweet, thought Miss Dimont, but he knows nothing. ‘Anything unusual about a death,’ she explained, ‘there’s a post-mortem. The coroner opens a public investigation into the circs.’

‘Excellent. There’s a lot to learn, isn’t there? And my journalism training course doesn’t start until I’ve been here three months.’

So you’re going to be a dead weight until then, thought Miss Dimont. ‘You know how to make a cup of tea?’

‘Er, yes.’

‘Jolly good,’ she said briskly. The boy wonder took the hint and slid away.

Miss Dimont paused for a moment to consider what she’d just been told. Though she made little of it, she was no stranger to death; and since her arrival in Temple Regis she’d figured significantly in the detection of a number of serious crimes. Within recent memory there was the case of Mrs Marchbank, the magistrate, who had managed to do away with her cousin in the most ingenious fashion. The fact that the police couldn’t make up their minds whether this new case was murder or accidental set the alarm bells ringing, but first she must finish the job in hand.

It took less than an hour to turn out six hundred words on the Lass O’Doune’s battles against nature, her triumphant victory in bringing food to the mouths of the nation, and the safe return from tumultuous seas. Miss Dimont made no mention of her own part in hauling in the rough and seething nets, her drenching by the ocean deep, the souvenir piece of turbot which she and Mulligatawny would share tonight – she did not believe in writing about herself.

Betty had no such qualms: she was always ready to illustrate her stories with a photograph or two of her digging a hole, baking a cake, riding a bicycle or anything else the photographer demanded. Actually she had one of those faces which looked nicer in photographs than in real life, and her editor often took advantage of her thirst for self-publicity. By comparison Judy Dimont was disinclined to make a display of herself: her elusive beauty was more difficult to capture, though Terry Eagleton, the chief photographer, had taken some gorgeous portraits of her only recently.

While she’d been finishing the fishermen piece, Valentine Waterford was having his copy rewritten by the chief sub-editor. He returned to discover Miss Dimont’s tea cold and untouched. ‘Perhaps a cup of coffee instead?’ he asked anxiously. ‘I’ll get the hang of it, I expect.’

‘Well,’ said Miss Dimont, ‘you better had. We all take turns to make the tea and,’ she added pointedly, ‘some people round here are quite fussy.’

‘I’ve decided on Ford,’ he replied, looking again as all young reporters do at his first story in print, and marvelling. ‘It fits into a column better.’

‘Good idea. Now come and tell me more about this dead body.’

The drab, bare hall behind St Margaret’s Church had never seen anything like it. Where normally baize-topped card tables were laid out for the Mothers’ Union weekly whist drive there were racks of clothes and a number of long mirrors. The hooks containing the choir’s cassocks and surplices had been cleared, in their place a selection of skimpy bathing costumes. Hat boxes littered the floor, the smell of face powder filled the air, and a number of young ladies in various states of undress could be seen bad-temperedly foraging for clothing, hairpins and inspiration.

‘Season gets earlier and earlier,’ said one grumpily. ‘Ain’t going down well with my Fred.’

‘Lend us your Mum rolette, dear.’

‘Certimly not. That’s personal.’

‘Oh go on, Molly, I always pong otherwise. Nerves, you know.’

‘Shouldn’t have nerves, the length of time you’ve been at this malarkey.’

They’d all been at it too long, if truth be told. But fame is a drug, and the acquisition of fame just as addictive. You had to look – and smell – your best at all times.

Molly Churchstow was looking a little long in the tooth today. Her life had become a triumph of hope over experience, for the longed-for crown which came with the title Queen of the English Riviera continued to elude her. But she remained determined: so determined, in fact, that her Fred had given up hope of ever marrying her, for the rules clearly stated that a beauty pageant contestant must be single. Even the merest glimpse of an engagement ring meant she would be jettisoned in the early rounds, once the maximum publicity of her enforced departure had been squeezed out of the local newspapers. Beauty queens must forever be single and available to their adoring public!

Molly hoped to be this year’s Riviera queen, having previously triumphed in the hotly-contested title fights for Miss Dawlish, Miss Teignmouth, and Miss Dartmouth, but it had been a long struggle with diminishing rewards. It would unkind to suggest that over the years she’d become a prisoner of her ambition – for Molly had a bee in her bonnet about being loved, being admired, and becoming famous.

Most of the girls in the grey-painted hall had a similar tale to tell. Each had tasted the mixed blessing of being a beauty queen: you got your photograph in the paper, people stopped you in the street for your autograph, you got a better class of boyfriend, usually with a car, and your love life was destined always to be a disaster.

But oh the thrill! The parades with mounted police, the brass bands, the motorcades through the town! The popping flashbulbs and your name in the papers!

‘Oh Lord, my corns,’ said Eve Berry, and sat down heavily. ‘How long are Hannaford’s giving you off? Or are you havin’ to do overtime to make up for the days off?’

‘Stocktaking in the basement with that lecher Mr French. It’s never very pleasant. You?’

Molly did not reply to this but hissed back, ‘Watch out, here comes The Slug.’

Looking not unlike like his nickname, Cyril Normandy elbowed his way through a dozen girls, his heavy feet crushing girdles, make-up bags, lipsticks and anything else which had fallen to the floor in the melee. Another man of his age and girth might dream and dream of sharing a room so filled with temptation, but not Normandy. Greed was etched into every line on his fat face and he looked neither to left nor right.

‘Stuff something into that top, Dartmouth,’ he said roughly to Molly. ‘You’re flat as a pancake.’

Molly was used to this.

‘As for you Exmouth,’ he said, referring to Eve’s title – he never used Christian names – ‘those shoes!’

‘You’ll have to let me have some on tick,’ said Eve, unsurprised by this attack on her battered high heels. ‘Can’t afford a new pair.’

The fat man looked at her meanly. ‘Borrow some,’ he snapped. ‘And get a move on, you’re due out there in two minutes.’

Altogether twenty-one girls were entered in this eliminating heat. Up for grabs was not only the Riviera queen title, but also the chance to go through to the next round of Miss Great Britain. And, after that, Miss World! Here in the church hall in Temple Regis there was a lot at stake, even if most of the girls were experienced enough to predict the outcome.

Normandy moved away towards the door, blowing a whistle as he went. The prettiest girls in Devon – those at least who were prepared to take part in this fanciful charade – lined up by the door, giving each other the once-over. They were uniformly clad in one-piece bathing suits, high heels, lacquered hair and bearing a cardboard badge on their right wrist signifying their competition number. Their elbows were as sharp as their mutual appraisals.

The Slug launched into his usual pre-pageant routine like a football manager before the match.

‘Just remember,’ he barked, ‘smile. You’re all walking advertisements for Devon so smile, damn you!

‘You’re all about to become famous. And rich. Watch your lip when you’re interviewed, keep smiling, and don’t fall over. There’s expenses forms on the table in the corner you can fill in afterwards.’

‘That’s a laugh,’ whispered Eve to Molly bitterly, thinking about the shoes.

‘“Smile”,’ parrotted Molly, but she did not suit the action to the word.

Normandy was adjusting his bow tie and smoothing his hair prior to sailing forth into the sunshine. His fussy self-important entrance into the Lido would cause the gathered crowds to cease their chatter and crane their necks. This was part of the joy of seaside life, the beauty pageant – an opportunity to sit in the sun and make catty comments about the size of the contestants’ feet.

‘I hadn’t expected this on my first day,’ said Valentine Waterford. ‘A murder and a beauty competition.’

‘Don’t get too excited,’ said Judy, putting on dark glasses with a dash of imperiousness. The bench they were sitting on was extremely hard. ‘And move over, you’re sitting on my dress.’

The young man edged apologetically away. ‘Look, it’s good of you to come,’ he said, ‘I rather expected to have to fend for myself.’

‘I wanted to go out to Todhempstead Beach. Just to take a look at where they found the girl.’

‘Wasn’t anything to see,’ said Valentine. ‘I drove out there after talking to the Inspector.’ His account faltered as the bathing belles made their entrance to a round of wild applause; Eve Berry wobbled slightly in her borrowed heels but managed to avert disaster. ‘By the time I got there it was all over, bit of a waste of time.’ He was betting with himself who would win.

‘That’s where you’re wrong,’ snipped Miss Dimont. ‘If you’re going to be a journalist you must learn to use your eyes.’ Why was she behaving like this? Rude, short, when really he was very charming. It must be the girls.

‘Empty beach, almost nobody there,’ he replied. ‘Only a couple of markers where presumably they found the body, but the tide was in and so you couldn’t see the sand. What else was there to see?’

Miss Dimont considered this.

‘Your story, the one you wrote this morning, said “mystery death”’ she said. ‘If you’re going to be a reporter and you’re going to write about mysteries, don’t you think it’s part of your job to try to get to the bottom of them?’

‘I see what you’re getting at,’ replied Valentine, ‘in a way. But surely that’s the police’s job? We just sit back and report what they find, don’t we, and if they mess it up we tell the public how useless they are?’

He certainly has got a relative in the business, thought Miss Dimont. A lazy one.

‘Tell me, Valentine, who’s your uncle, the one who’s in newspapers?’

‘Gilbert Drury.’

‘Oh,’ said Miss Dimont, wrinkling her nose. ‘The gossip columnist. That makes sense.’

‘Well,’ said Valentine, beating a hasty retreat, ‘not really my uncle. More married to a cousin of my mother’s.’

A wave of applause drowned Miss Dimont’s reply as the contestants for the title of Queen of the English Riviera 1959 were introduced one by one.

The master of ceremonies introduced his menagerie. ‘Ladies and gentlemen,’ he boomed into the microphone, ‘you do us a very great honour in being here today to help select our next queen from this wondrous array of Devon’s beauty.’

Something in his tone implied however that he, Cyril Normandy, was the one conferring the honour, not the paying public. The hot June sunlight was gradually melting the Brylcreem which held down his thinning hair and at the same time it highlighted the dandruff sprinkled across the shoulders of his navy blazer.

‘As you know, it has fallen to Temple Regis to host these important finals this year, and let me remind you, ladies and gentlemen, the winner of today’s crown will go on to compete in Miss Great Britain in the autumn. So this is a huge stepping stone for one of these fine young ladies, on their way to fame and fortune, and, ladies and gentlemen, it will be you who is to be responsible for their future happiness!

‘Just take a very close look at all these gorgeous girls, because, ladies and gentlemen, it is your vote that counts!’

‘Are you taking notes?’ said Miss Dimont crisply from behind the dark glasses.

‘I, er …’

‘You’ll find it an enormous help as you go along to have a pencil and notebook about your person. Sort of aide-memoire,’ she added with more than a hint of acid. ‘For when you’re back at the office searching your memory for people’s names. You’ll find they come in handy.’ Maybe the hot sun was reacting badly to the lost sleep and the early-morning rum, not to mention the force nine. This was not like Miss Dimont!

The well-padded MC had a microphone in his hand now and was interviewing the girls by the pool’s edge, apparently astonished by the wisdom of their answers. But while he debriefed them on how proud they were to be an ambassador for Britain’s most-favoured county, about their ambitions to do well for themselves and the world, and, most importantly, what a thrill it was to support the town whose sash they had the honour to wear, they were thinking of the free cosmetics and underwear, the trips to London, the boys they might yet meet, and how their feet hurt.

‘Don’t seem to have the full complement,’ puzzled Valentine, looking down the flimsy programme.

‘What was going on back at the police station,’ pondered Miss Dimont, ignoring this and returning to her earlier theme, ‘about whether it was murder or misadventure?’

‘One missing. Erm, what?’

‘Inspector Topham.’

‘He was definite it was accidental.’

‘Something has to account for the fact that Sergeant Gull told you it was murder. I’ve never known him wrong.’

‘But the Inspector outranks him. It was the Inspector who went out to view the scene. So it must be the inspector who’s right.’

‘Never that simple in Temple Regis,’ murmured Miss Dimont, thinking of Dr Rudkin, the coroner, and how he always liked to sweep things under the carpet. ‘No, for the word to have got back to the sergeant that it could be murder must mean that’s what the first call back to the station said.’

‘But why were the body markers so far away from the railway embankment?’ Valentine was suddenly more interested in this conversation than he was in the girls who were parading up and down the pool edge. ‘She couldn’t have fallen, or been pushed, that far away from the railway line.’

‘There you have it—’ Miss Dimont smiled and, lifting her dark glasses, turned to face the trainee reporter ‘—in a nutshell. A mystery death. Needs looking into, wouldn’t you say?’

Valentine Waterford smiled back. He had no idea what a time he was in for.

FOUR (#ulink_c9240db8-1d13-511d-b046-eccb2b2ca1ea)

Perched high on the cliffs at the tip of the estuary, Ransome’s Retreat boasted the most beautiful gardens in the west of England, its terraces tumbling over the rocks into apparent infinity and its borders filled with a dazzling year-round display.

Palm trees wafted. Magnolias, a century old, lined the paths between terraces and from the branches above hung heavy Angel’s Trumpets. The glasshouses were filled with ripening peaches and pineapples, and the newly shaved lawns gave off a honeyed scent which made visitors feel they had arrived at the gates of Eden.

‘Some more tea, Mr Larsson?’ ‘I’m exhausted.’

‘No more visitors today, sir,’ the manservant said soothingly. ‘All gone now.’

‘Just too tiring,’ complained the old man. ‘Debilitating. And such a bore.’

The world-famous inventor of Larsson’s Life Rejuvenator looked as if he could use a touch of his own medicine. Though the contraption had made him a rich man, keeping it before the public eye these days sapped his energy. His hand fluttered slightly as he reached for the teacup.

There was a time, before the War, when his factory could not make enough of them. The little leather-covered boxes containing a complex electrical device had been shipped all over the world. Larsson’s clients included royalty, film stars, cabinet ministers, and a wide range of society figures, especially ladies of a certain age. It was guaranteed to put a spring back in everyone’s step.

Post-war, however, when most people felt lucky just to be alive, there seemed to be less of a thirst to have one’s life rejuvenated – maybe just waking up and finding one was breathing was enough. And certainly, in these straitened times, even the rich were finding better things to do with their money.

‘No more phone calls, Lamb,’ he said. ‘I’m going to take a nap.’ Bengt Larsson – Ben to that small circle who called themselves his friends – was rich. Very. But his estate in Argentina bled money, the Cote d’Azur mansion similarly, and his two private airplanes – one in Deauville, one in Devon – cost a packet to keep going. Fame is a furnace which needs constant stoking.

Fame can also be a fickle friend: left half-hidden among the pillows on the terrace bench the great man had just vacated was a crumpled copy of the Daily Herald the dutiful Lamb had tried his best to hide at breakfast. Larsson’s face, still handsome after all these years, stared out from a page whose headline screamed:

THE LARSSON LEGACY:

DEATH, DEPRESSION, DEGRADATION

– this is what you can expect

when you buy his famous Rejuvenator

This morning the Daily Herald exposes the truth behind the world-famous Larsson Life Rejuvenator, which has made its Swedish-born inventor one of the country’s richest men.An investigation by this newspaper proves beyond all doubt that Bengt Larsson’s promises that yourlife will be healthier, longer and livelier by the use of his machine are false.The inventor, who started his career in a chemist’s shop in Hull, has made repeated promises about the efficacy of the Rejuvenator. It has been endorsed by actors, radio stars and other famous figures, but a laboratory trial conducted by the (turn to p.5)

From the sun-dappled lawns blackbirds collected their worms and flew up into the eucalyptus trees to nourish their young, oblivious to the crisis unfolding beneath. The manservant Lamb collected the tea things and moved indoors out of the hot sun. Calm, of a sort, descended.

In the garden room Pernilla Larsson was writing a letter. Or, more exactly, not writing a letter. This latest press attack on her husband was not only bad for business, it unsettled life at Ransome’s Retreat. And though as the inventor’s fourth wife, she had brought a new stability to his restless life, Larsson was an unpredictable man given to violent mood swings and she could never be sure where things would go with him. It made concentrating very difficult.

‘Lamb.’

‘Yes, madam?’

‘Have you given my husband his sedative?’

‘In the second cup, madam.’ Mistress and servant looked steadily at each other.

‘Ask Gus to come in.’

‘Very well, m’m.’

Just then an array of ancient clocks positioned across the ground floor of the ancient house raggedly signalled their agreement that it was four o’clock, and a confident-looking young man entered with a sheaf of papers in his hand.

‘What worries me,’ he said, ‘is not the Herald. It’s those idiots at the Doctors’ Medical Journal. They’re determined to get him.’

‘They’ve always hated him. Ever since he published A New Electronic Theory of Life.’

‘Quacks,’ uttered Gus Wetherby with a sneer. ‘Just because they’ve got medical qualifications they think they know everything. There are people on that journal who are out to get him, no matter what. Medics! Wouldn’t surprise me if they weren’t behind this latest press attack.’

Pernilla Larsson took off her glasses and looked at her son. ‘There are a lot of people,’ she said slowly, ‘who might be behind this latest attack. People have turned against Ben, they really have.’

‘Not altogether – we still have the daily visitors. The pilgrims to the shrine.’

‘I wish he hadn’t started that movement. It’s an embarrassment in the present circumstances – it was supposed to be about health and vitality, but they turned it into a religion! It’s one thing to say your invention can extend human life, quite another to allow people to believe there’s something mystical attached to it.’

‘They’re nuts. They think his book is the Bible.’

Wetherby picked up a biscuit off the tea tray. ‘That was all before the War,’ he went on. ‘People looking for something that couldn’t be found. Hoping to contact loved ones, trying to make sense of that lost generation after the First War. People who didn’t believe in spiritualism and Ouija boards and all that junk, but were looking for something …’

‘That couldn’t be found,’ said Pernilla, completing his sentence. The two often thought as one, it was uncanny.

‘So where are we?’ she said, collecting her thoughts. ‘Are the specifications right?’

‘I had them checked. We can go ahead.’

‘There’s just the matter of convincing Ben.’

The conspirators paused. ‘Look,’ said Gus, ‘even Ben knows the game’s up. Once upon a time people believed the Rejuvenator really did what it’s supposed to do but …’

‘You know he won’t accept criticism,’ warned Pernilla. ‘And he can’t accept the idea of change.’

‘That’s the problem, he’s a one-trick pony. All that publicity at the beginning – “Hope for the Aged – Electricity to Make Old Folk Young” – that kind of thing, it went to his head. And all he’d invented was a dolled-up and very expensive box of tricks, something that you plugged yourself into when you felt low which delivered a weak electric current and made you think you felt better.’

‘Don’t be disloyal!’ snapped Pernilla, though her response seemed automatic rather than anything else. ‘HE believed in it, THEY believed in it, therefore we must believe in it too.’ She paused for a moment, pulled in two directions. ‘Though I must confess the letters which are rolling in these days – people don’t want to believe any more. They want their money back.’

‘He shouldn’t have charged so much.’

Pernilla looked around the long, low room, its walls dotted with Impressionist paintings. ‘It bought all this,’ she reminded him quietly.

‘It can be done again,’ said Gus forcefully. ‘Now that we’ve found the formula for a Rejuvenator which really does work.’

Pernilla nodded. ‘All those old men,’ she sighed. ‘All wanting to be young again. All thinking, with the Rejuvenator I can have a younger model.’

Gus raised an eyebrow and smiled. Didn’t his mother become the fourth Mrs Larsson for precisely that reason?

‘Oh yes!’ she said, catching his meaning. Her cigarette holder described an elegant parabola as she laughed, her salt-and-pepper hair glowed, and her jewellery flashed in the sunlight. She looked expensive.

‘We still have to find a way to kill the kind of publicity we’re getting in the press,’ said Gus. ‘Have to announce the new model. Different name, fresh start.’

He warmed to his theme. ‘Got to stop those attack dogs at the Medical Journal. It would make sense for us to tell them, look, the Rejuvenator is a thing of the past, a creature of its time, whatever they want to hear – stopping short, of course, of saying that it never actually worked.’

Wetherby broke his biscuit in half but left its tumbling crumbs to disappear into the folds of the sofa while he thought. ‘We say it’s a new idea with a new inventor – me. Push Ben back into the shadows. For heaven’s sake, he’s eighty. Time to take a back seat!’

‘It’s been his whole life.’

‘Let him enjoy what’s left of it. Look,’ said Wetherby, standing up, ‘this is possibly the most idyllic place anywhere in the world – this house, these gardens, this climate. Back seat!’

‘He won’t agree.’

‘He’ll have to agree,’ said Gus Wetherby harshly, ‘or we’re all dead.’

The sun made its slow descent behind the Temple Regis skyline, gilding the rooftops, casting long black shadows across the greensward towards the broad open sands.

‘There are five hundred stars,’ sighed Athene Madrigale, the famous astrologer, looking upwards, ‘all competing with each other for my attention.’

Her companion did not take much notice of this. Athene often spoke like that.

‘I have been listening to the waves shuffling the stones. I have been watching the moon pulling the waves. Can you hear?’

There was a pause.

‘A shame about the dead girl,’ said Judy Dimont slowly. ‘Horrible, really.’

Athene nodded. They understood each other’s preoccupations.

Night was Athene’s daytime. It allowed her the space to clear her mind for the impossible task of telling Temple Regents what lay ahead in their lives. Her column in the Riviera Express was the most important part of the newspaper, foretelling events in readers’ lives with startling accuracy:

Pisces: an event of great joy is about to occur – to you, or your loved ones.

Sagittarius: look around and see new things today! They are glorious!

Cancer: never forget how kind a friend can be to you. Do the same for them and you will be rewarded threefold!

People read her column and felt better. Those very few who had been privileged to actually meet Athene were struck by her special radiance, and it was only a fool who dismissed her outpourings as ingenuous nonsense.

Tonight, she was wearing a lemon top, pink skirt and purple trousers. The plimsolls on her feet were quite worn and of differing hues, but one of them matched perfectly the blue paper rose she wore in the bun on the back of her head. In the half-light the overall effect was strangely soothing.

‘I can’t believe it was an accident,’ said Miss Dimont. They had walked over to a bench on the promenade and sat to watch the last golden light slowly disappear from the horizon.

‘The girl?’ asked Athene.

‘Yes, the girl.’

‘I was there,’ said Athene. ‘On the beach.’

‘Todhempstead Sands?’

‘Yes.’

‘Good Lord, why didn’t you say sooner, Athene? This could be murder, you know.’

Athene turned her head slowly to her companion. ‘She didn’t die there.’

Miss Dimont, the veteran of many a similar inquiry, was bemused. How could Athene Madrigale be witness to a murder – or an accidental death, whichever it was – and not tell anyone?

‘Why …?’ she started.

‘I was counting the clouds, dear. It’s very difficult – have you ever tried? Altostratus, cumulonimbus, dear sweet cirrus – I was too busy to really see what happened.’

‘But …’

‘I only noticed when those policemen came down onto the beach. Then I saw the girl’s body.’

‘So how could you know whether she died there or not?’

‘The clouds told me.’

Miss Dimont kicked her raffia bag in frustration. On the one hand she had an eyewitness, on the other she did not. Then again, most things Athene said turned out to be true – but if this was a murder, if the girl had died on or near the beach, as evidence it was valueless.

For the time being, at least.

‘I’m going back to the office,’ said Judy. ‘Coming?’ Home and Mulligatawny were going to have to wait tonight.

‘Have to think carefully about my column,’ said Athene. ‘I’ll make you some of my special tea if you’re still there later.’

Miss Dimont walked over to the kerbside where Herbert, her faithful moped, stood expectantly awaiting their next expedition. At the kick of a pedal, he sprang cheerfully into action and together they made their way back up the promenade towards the Riviera Express.

Though during the day the newspaper office was like a ship’s engine room, a positive maelstrom of movement and drama, by the time dusk fell the place was usually empty – as if news only happened during the day! She walked up the long corridor to the newsroom, past the mousetraps laid down to capture nocturnal visitors, but as she approached she could hear the slow, almost ghostly, tapping of a typewriter.

She pushed open the door and looked down the long office to her desk. Seated with his back to her was the new boy, Valentine whatsisname. He appeared to be writing something up, and was taking his time about it.

Miss Dimont was not pleased. She wanted the place to herself.

‘Hello, Valentine,’ she said, not entirely kindly. ‘Don’t you have a home to go to?’

The young man swung round and delivered a rueful smile. ‘Actually there was a bit of a palaver over accom,’ he replied. ‘They parked me in the oddest place – a bed and breakfast done up to look like a castle, only the inside walls of the house were painted like the outside of the castle. Not quite the home from home.’

From this light mockery might be deduced the young Waterford once actually lived in a castle. He’d been quite evasive about where he came from.

‘They all go there,’ said Judy. ‘Usually last longer than you before making a bolt for it.’

‘Actually there’s a cottage belonging to the family. Thought it better to go there. Bedlington.’

Miss Dimont looked over his shoulder at the paper in Valentine’s typewriter. ‘So what are you writing now?’

‘I was given a word of advice by Mr Ross,’ he said, nodding amiably towards the old Scotsman. ‘He said the first thing you should do when you join a newspaper is write your own obituary.’

‘Are you thinking of dying any time soon, Valentine?’

‘You never know.’

‘How old are you?’

‘Twenty-three soon.’

Miss Dimont sat down at her desk. It had been her intention to write a Comment piece about the award-winning fishermen – brave, hardy men bringing lustre to Temple Regis along with their rich daily harvest – but it was getting late and she’d had an early start. Her return to the office was more a delaying tactic because by now she was exhausted – and the thought of kick-starting Herbert, who could be obstructive if left waiting too long in the dark, suddenly drained her of the will to go home.

‘How are you getting on?’ she asked, more out of good manners than with any real interest.

‘It’s difficult. School, army, one day on the newspaper. Not a lot to write about. Then I thought, well, I could add a bit about my family background so I started doing that. But then it seemed rather boastful so I …’

Miss Dimont’s eyes travelled down to the wicker bin by Valentine’s ankle and saw that he must have been at his task for some time – it was overflowing with rejected copy paper, scrumpled and torn and trodden on. This young man is very keen, she observed.

‘What is there of interest about your, er, the Waterfords?’ she asked.

‘Well, rather ancient. Been around a long time, quite a few of us. None of them journalists.’

‘Except your uncle.’

‘Mmm. Wish I’d never mentioned him. I can see he’s not popular down here. In London, of course …’

‘People down here don’t often go to Mayfair,’ said Judy, quite sharply. ‘Your uncle Gilbert never seems to leave it if you believe what he writes in his column.’

‘I shan’t be following in his footsteps.’

‘I’m going home,’ she said. ‘Don’t take all night with the obituary. It’s helpful if you set yourself a deadline and then stick to it. Look,’ she said, pointing at the great newsroom clock, ‘it’s 8.30. Give yourself until 9.30.’

The young man ran his hands despairingly through his wavy blond hair. He was going to be a handful to train up, she could see.

On the other hand, he really was quite pleasant to look at.

FIVE (#ulink_69227a5a-117d-5e19-adc4-3279852d6b38)

‘Morning, Mr Rhys.’ It was nine o’clock and the sun’s rays were already unbearably hot through the newsroom windows. The journey into town atop the trusty Herbert, hair blowing in the breeze, had been sheer joy for Miss Dimont, but indoors the atmosphere seemed suddenly oppressive.

‘I said, good morning, Mr Rhys.’

‘Rr …rrr.’ The editor did not even have a briar pipe to argue with this morning; instead the point of contention had apparently been the Daily Herald on the telephone.

‘Come in, Miss Dim.’

He would call her that, and really there was no need – especially on such a fine day, so full of promise.

‘Please don’t.’

‘Miss Dimont. What are you doing this morning?’

‘In court,’ said his chief reporter. ‘Do you want me to take along Mr, er, Ford?’

‘Ford? Who’s Ford?’

‘The new recruit. Wants to shorten his name for byline purposes.’

‘There’ll be no bylines round here,’ snorted the editor, ‘until he starts pulling in some stories. Anyway that’s not what I wanted to talk to you about.’

Uninvited, Miss Dimont sat down opposite her employer. There was, after all, a time when he’d stood before her desk while she sat and issued instructions, but that had been long ago. It was one of life’s ironies that the War had a way of changing things for the better and the peace, for the worse. Life was peculiar that way.

‘Ben Larsson,’ said the editor. ‘You saw the piece in the national press yesterday.’

‘Well deserved. The man’s a mountebank,’ said Miss Dimont firmly. ‘A fraud. I thought they treated him with kid gloves, considering.’

‘He is – without doubt Miss Dimont, without a shadow of a doubt – the most famous resident of Temple Regis,’ hissed the editor. ‘While he remains at Ransome’s Retreat we treat him with the respect that position demands.’

Miss Dimont laughed aloud. ‘Oh yes!’ she hooted, ‘just think of the number of complaints we’ve had in the past couple of years about the Rejuvenator – how it claims to do everything, and manages to do nothing! How people have been diddled out of their money. That’s quite apart from all those sad souls who make their pilgrimage to the Retreat because they believe Larsson is somehow skippering the advance party of the Second Coming. They make Temple Regis a laughing stock.’

‘That’s not the point.’ If Rhys sought a quiet life, sheltered from controversy, he really had chosen the wrong profession, thought Miss Dimont. ‘I don’t want anything about Larsson in the paper, d’you understand, and if the Daily Herald calls again asking for more details, as they did just now, just say we are not at home to sensationalism.’

‘It was a perfectly legitimate story. They did an investigation and it proved beyond all doubt that …’

‘I know what the paper did,’ snapped Rhys. ‘I can read, Miss Dim! I just don’t want that rubbish in my pages so I called you in here – because you can stir up trouble, once you get going – to tell you to leave this one alone. No stories about Larsson in the paper, and no help to Fleet Street.’

‘They’ll come down here anyway and camp in your office, like they always do when there’s a big story.’

Her words hit home. When in the past the national press had paid a call, they invariably left the good people of Temple Regis thinking what a weak and flabby offering they had for a weekly newspaper – even if it did have Athene Madrigale as its star columnist. Rhys hated the Fleet Street pressmen with their trilby hats and big coats and lingering cologne and expense accounts taking up the desks in his newsroom, a privilege he could not deny them if he were still to call himself a newspaperman. They came like cuckoos to the nest, sucking up the nourishment, making a nuisance, and destroying the sense of calm and harmony Mr Rhys tried hard to maintain throughout the year. He really should have chosen another job, but there it was; a failed novelist doesn’t have that many career choices.

The windows in his office were wide open and you could hear the swooping seagulls mocking him outside.

‘Stay away from the Retreat and get on with what you’re supposed to be doing,’ warned the editor. ‘Hear me?’

‘This murder,’ Judy said, artfully changing tack. ‘The girl on the beach.’

‘Rr … rrrr. Accident, the police are saying. Don’t go mucking about in things. You know what people will say.’

Indeed Miss Dimont did know. On the one hand the townsfolk lapped up anything a bit unusual in their weekly newspaper, and a murder certainly made a nice change, on the other, the city fathers hated it: bad for business. If Temple Regis was to maintain its claim to being the handsomest resort in Devon, the last thing they wanted was holidaymakers thinking they might trip over a body or two on the beach. Rudyard Rhys unequivocally sided with this position.

Miss Dimont sat back and said nothing more. To a large extent Rhys had to rely on what he was given, editorially, by his staff – and if his chief reporter came up with something newsworthy, it would inevitably find its way into the paper. Newspapers are like that: they don’t want you doing things but when you do them, they’re grateful.

Only they never say so.

‘However,’ said Rhys, for he felt he had to show initiative as a leader, ‘this piece of Betty’s, about the woman and the Six Point Group.’

‘Yes, Mr Rhys?’

‘I think we can do better than that. Go and see this Miss de Mauny. For heaven’s sake, how many women do you know who fix clocks for a living?’