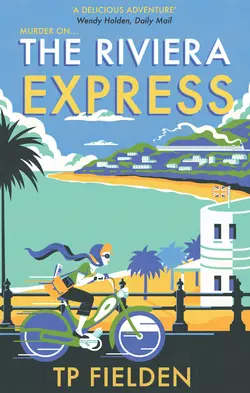

The Riviera Express

TP Fielden

‘A delicious adventure’ – Daily MailMurder on the Riviera ExpressGerald Hennessey – silver screen star and much-loved heart-throb – never quite makes it to Temple Regis, the quaint Devonshire seaside town on the English Riviera. Murdered on the 4.30 from Paddington, the loss of this great man throws Temple Regis’ community into disarray.Not least Miss Judy Dimont –corkscrew-haired reporter for the local rag, The Riviera Express. Investigating Gerald’s death, she’s soon called to the scene of a second murder, and, setting off on her trusty moped, Herbert, finds Arthur Shrimsley in an apparent suicide on the clifftops above the town beach.Miss Dimont must prevail – for why was a man like Gerald coming to Temple Regis anyway? What is the connection between him and Arthur? And just how will she get any answers whilst under the watchful and mocking eyes of her infamously cantankerous Editor, Rudyard Rhys?‘This is a fabulously satisfying addition to the canon of vintage crime. No wonder the author has already been signed up to produce more adventures starring the indefatigable Miss Dimont.’ Daily Express‘Unashamedly cosy, with gentle humour and a pleasingly eccentric amateur sleuth, this solid old-fashioned whodunit is the first in what promises to be an entertaining series.’ The Guardian‘Highly amusing’ Evening Standard‘TP Fielden is a fabulous new voice and his dignified, clever heroine is a compelling new character. This delicious adventure is the first of a series and I can’t wait for the next one.’ Wendy Holden, Daily MailMust have. A golden age mystery.’ Sunday Express‘Tremendous fun’ The Independent

TP FIELDEN is a biographer, broadcaster and journalist. The Riviera Express is the first in the English Riviera Murders series featuring Miss Dimont.

For CRCW

Dei due, la migliore

Contents

Cover (#u8c6f9555-dd62-5a53-b8a5-e0201e3fa25c)

Title Page (#u28691024-4389-545d-8efc-1fc9ec0c4a40)

About the Author (#ulink_9d2b1a5e-6365-5c11-95d0-0df93ef4cbb7)

Dedication (#ua4fc39a5-3528-5d08-a88e-f217704f792e)

ONE (#ulink_afb9114c-9211-50b6-8ae0-b151e73bba14)

TWO (#ulink_34f10e2f-ce13-5cf5-ad64-dda2baae0fd5)

THREE (#ulink_6489c7d4-923d-55fe-a86c-96c859313885)

FOUR (#ulink_536bd8c7-218e-5187-8447-cfcf3fa0af76)

FIVE (#ulink_9c32e7aa-f8ff-5075-b478-726d826646de)

SIX (#ulink_3376524a-026d-5b78-8a19-3e367ae86ff2)

SEVEN (#ulink_93c60002-d31b-55be-b398-c04f7a355082)

EIGHT (#litres_trial_promo)

NINE (#litres_trial_promo)

TEN (#litres_trial_promo)

ELEVEN (#litres_trial_promo)

TWELVE (#litres_trial_promo)

THIRTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

FOURTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

FIFTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

SIXTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

SEVENTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

EIGHTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

NINETEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY-ONE (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY-TWO (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY-THREE (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY-FOUR (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY-FIVE (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY-SIX (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY-SEVEN (#litres_trial_promo)

Extract (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

ONE (#ulink_fdfb71af-b7f3-5b55-b514-3e3859960843)

When Miss Dimont smiled, which she did a lot, she was beautiful. There was something mystical about the arrangement of her face-furniture – the grey eyes, the broad forehead, the thin lips wide spread, her dainty perfect teeth. In that smile was a joie de vivre which encouraged people to believe that good must be just around the corner.

But there were two faces to Miss Dimont. When hunched over her typewriter, rattling out the latest episode of life in Temple Regis, she seemed not so sunny. Her corkscrew hair fell out of its makeshift pinnings, her glasses slipped down the convex nose, those self-same lips pinched themselves into a tight little knot and a general air of mild chaos and discontent emanated like puffs of smoke from her desk.

Life on the Riviera Express was no party. The newspaper’s offices, situated at the bottom of the hill next door to the brewery, maintained their dreary pre-war combination of uprightness and formality. The front hall, the only area of access permitted to townsfolk, spoke with its oak panelling and heavy desks of decorum, gentility, continuity.

But the most momentous events in Temple Regis in 1958 – its births, marriages and deaths, its council ordinances, its police court and its occasional encounters with celebrity – were channelled through a less august set of rooms, inadequately lit and peopled by journalism’s flotsam and jetsam, up a back corridor and far from the public gaze.

Lately there’d been a number of black-and-white ‘B’ features at the Picturedrome, but these always portrayed the heady excitements of Fleet Street. Behind the green baize door, beyond the stout oak panelling, the making of this particular local journal was decidedly less ritzy.

Far from Miss Dimont lifting an ivory telephone to her ear while partaking of a genteel breakfast in her silk-sheeted bed, the real-life reporter started her day with an apple and ‘The Calls’ – humdrum visits to Temple’s police station, its council offices, fire station, and sundry other sources of bread-and-butter material whose everyday occurrences would, next Friday, fill the heart of the Express.

Like a laden beachcomber she would return mid-morning to her desk to write up her gleanings before leaving for the Magistrates’ Court, where the bulk of her work, from that bottomless well of human misdeeds and misfortunes, daily bubbled up.

After luncheon, usually taken alone with her crossword in the Signal Box Café, she would return briefly to court before preparing for an evening meeting of the Town Council, the Townswomen’s Guild, or – light relief – a performance by the Temple Regis Amateur Operatic Society.

Then it would be home on her moped, corkscrew hair blowing in the wind, to Mulligatawny, whose sleek head would be staring out of the mullioned window awaiting his supper and her pithy account of the day’s events.

Miss Dimont, now unaccountably beyond the age of forty, had the fastest shorthand note in the West Country. In addition, she could charm the birds out of the trees when she chose – her capacity to get people to talk about themselves, it was said, could make even the dead speak. She was shy but she was shrewd; and if perhaps she was comfortably proportioned she was, everyone agreed, quite lovely.

Why Betty Featherstone, her so-called friend, got the front-page stories and Miss Dimont did not was lost in the mists of time. Suffice to say that on press day, when everyone’s temper shortened, it was Judy who got it in the neck from her editor. Betty wrote what he wanted, while Judy wrote the truth – and it did not always make comfortable reading. She didn’t mind the fusillades aimed in her direction for having overturned a civic reputation or two, for ever since she had known him, and it had been a long time, Rudyard Rhys had lacked consistency. Furthermore, his ancient socks smelt. Miss Dimont rose above.

Unquestionably Devon’s prettiest town, Temple Regis took itself very seriously. Its beaches, giving out on to the turquoise and indigo waters which inspired some wily publicist to coin the phrase ‘England’s Riviera’, were white and pristine. Broad lawns encircling the bandstand and flowing down towards the pier were scrupulously shaved, immaculately edged. Out in the estuary, the water was an impossible shade of aquamarine, its colour a magical invention of the gods – and since everyone in Temple agreed their little town was the sunniest spot in England, it really was very beautiful.

It was far too nice a place to be murdered.

*

Confusingly, the Riviera Express was both newspaper and railway train. Which came first was occasionally the cause for heated debate down in the snug of the Cap’n Fortescue, but the laws of copyright had not yet been invented when the two rivals were born; and an ambitious rail company serving the dreams of holidaymakers heading for the South West was certainly not giving way to a tinpot local rag when it came to claiming the title. Similarly, with a rock-solid local readership and a justifiable claim to both ‘Riviera’ and ‘Express’ – a popular newspaper title – the weekly journal snootily tolerated its more famous namesake. If neither would admit it, each benefited from the other’s existence.

Before the war successive editors lived in constant turmoil, sometimes printing glowing lists of the visitors from another world who spilled from the brown and cream liveried railway carriages (‘The Hon. Mrs Gerald Legge and her mother, the novelist Barbara Cartland, are here for the week’). At other times, Princess Margaret Rose herself could have puffed into town and the old codgers would have ignored it. Rudyard Rhys saw both points of view so there was no telling what he would think one week to the next – to greet the afternoon arrival? Or not to bother?

‘Mr Rhys, we could go to meet the 4.30,’ warned his chief reporter on this particular Tuesday. ‘But – also – there’s a cycling-without-lights case in court which could turn nasty. The curate from St Margaret’s. He told me he’s going to challenge his prosecution on the grounds that British Summer Time has no substantive legal basis. It could be very interesting.’

‘Rrrr.’

‘Don’t you see? The Chairman of the Bench is one of his parishioners! Sure to be an almighty dust-up!’

‘Rrrr . . . rrr.’

‘A clash between the Church and the Law, Mr Rhys! We haven’t had one of those for a while!’

Rudyard Rhys lit his pipe. An unpleasant smell filled the room. Miss Dimont stepped back but otherwise held her ground. She was all too familiar with this fence-sitting by her editor.

‘Bit of a waste going to meet the 4.30,’ she persisted. ‘There’s only Gerald Hennessy on board . . .’ (and an encounter with a garrulous, prosy, self-obsessed matinée idol might make me late for my choir practice, she might have added).

‘Hennessy?’ The editor put down his pipe with a clunk. ‘Now that’s news!’

‘Oh?’ snipped Miss Dimont. ‘You said you hated The Conqueror and the Conquered. “Not very manly for a VC”, I think were your words. You objected to the length of his hair.’

‘Rrrr.’

‘Even though he had been lost in the Burmese jungle for three years.’

Mr Rhys performed his usual backflip. ‘Hennessy,’ he ordered.

It was enough. Miss Dimont noted that, once again, the editor had deserted his journalistic principles in favour of celebrity worship. Rhys enjoyed the perquisite accorded him by the Picturedrome of two back stalls seats each week. He had actually enjoyed The Conqueror and the Conquered so much he sat through it twice.

Miss Dimont did not know this, but anyone who had played as many square-jawed warriors as Gerald Hennessy was always likely to find space in the pages of the Riviera Express. Something about heroism by association, she had noted in the past, was at the root of her editor’s lofty decisions. That all went back to the War, of course.

‘Four-thirty it is, then,’ she said a trifle bitterly. ‘But Church v. Law – now there’s a story that might have been followed up by the nationals,’ and with that she swept out, notebook flapping from her raffia bag.

This parting shot was a reference to the long-standing feud between the editor and his senior reporter. After all, Rudyard Rhys had made the wrong call on not only the Hamilton Biscuit Case, but the Vicar’s Longboat Party, the Temple Regis Tennis Scandal and the Football Pools Farrago. Each of these exclusives from the pen of Judy Dimont had been picked up by the repulsive Arthur Shrimsley, an out-to-grass former Fleet Street type who made a killing by selling them on to the national papers, at the same time showing up the Riviera Express for the newspaper it was – hesitant, and slow to spot its own scoops when it had them.

On each occasion the editor’s decision had been final – and wrong. But Judy was no saint either, and the cat’s cradle of complaint triggered by her coverage of the Regis Conservative Ball last winter still made for a chuckle or two in the sub-editors’ room on wet Thursday afternoons.

With her raffia bag swinging furiously, she stalked out to the car park, for Judy Dimont was resolute in almost everything she did, and her walk was merely the outer manifestation of that doughty inner being – a purposeful march which sent out radar-like warnings to flag-day sellers, tin-can rattlers, and other such supplicants and cleared her path as if by miracle. It was not manly, for Miss Dimont was nothing if not feminine, but it was no-nonsense.

She took no nonsense, either, from Herbert, her trusty moped, who sat expectantly, awaiting her arrival. With one cough, Herbert was kicked into life and the magnificent Miss Dimont flew away towards Temple Regis railway station, corkscrew hair flapping in the wind, a happy smile upon her lips. For there was nothing she liked more than to go in search of new adventures – whether they were to be found in the Magistrates’ Court, the Horticultural Society, or the railway station.

Her favourite route took in Tuppenny Row, the elegant terrace of Regency cottages whose brickwork had turned a pale pink with the passage of time, bleached by Temple Regis sun and washed by its soft rains. She turned into Cable Street, then came down the long run to the station, whose yellow-and-chocolate bargeboard frontage you could glimpse from the top of the hill, and Miss Dimont, with practice born of long experience, started her descent just as the sooty, steamy clouds of vapour from the Riviera Express slowed in preparation for its arrival at Regis Junction.

She had done her homework on Gerald Hennessy and, despite her misgivings about missing the choir practice, she was looking forward to their encounter, for Miss Dimont was far from immune to the charms of the opposite sex. Since the War, Hennessy had become the perfect English hero in the nation’s collective imagination – square-jawed, crinkle-eyed, wavy-haired and fair. He spoke so nicely when asked to deliver his lines, and there was always about him an air of amused self-deprecation which made the nation’s mothers wish him for their daughters, if not secretly for themselves.

Miss Dimont brought Herbert to a halt, his final splutter of complaint lost in the clanking, wheezing riot of sooty chaos which signals the arrival of every self-regarding Pullman Express. Across the station courtyard she spotted Terry Eagleton, the Express’s photographer, and made towards him as she pulled the purple gloves from her hands.

‘Anyone apart from Hennessy?’

‘Just ’im, Miss Dim.’

‘I’ve told you before, call me Judy,’ she said stuffily. The dreaded nickname had been born out of an angry tussle with Rudyard Rhys, long ago, over a front-page story which had gone wrong. Somehow it stuck, and the editor took a fiendish delight in roaring it out in times of stress. Bad enough having to put up with it from him – though invariably she rose above – but no need to be cheeked by this impertinent snapper. She had mixed feelings about Terry Eagleton.

‘Call me Judy,’ she repeated sternly, and got out her notebook.

‘Ain’t your handle, anyways,’ parried Terry swiftly, and he was right – for Miss Dimont had a far more euphonious name, one she kept very quiet and for a number of good reasons.

Terry busily shifted his camera bag from one shoulder to the other. Employed by his newspaper as a trained observer, he could see before him a bespectacled woman of a certain age – heading towards fifty, surely – raffia bag slung over one shoulder, notebook flapping out of its top, with a distinctly harassed air and a permanently peppery riposte. Though she was much loved by all who knew her, Terry sometimes found it difficult to see why. It made him sigh for Doreen, the sweet young blonde newly employed on the front desk, who had difficulty remembering people’s names but was indeed an adornment to life.

Miss Dimont led the way on to Platform 1.

‘Pics first,’ said Terry.

‘No, Terry,’ countered Miss Dim. ‘You take so long there’s never time left for the interview.’

‘Picture’s worth a thousand words, they always say. How many words are you goin’ to write – two hundred?’

The same old story. In Fleet Street, always the old battle between monkeys and blunts, and even here in sweetest Devon the same old manoeuvring based on jealousy, rivalry and the belief that pictures counted more than words or, conversely, words enhanced pictures and gave them the meaning and substance they otherwise lacked.

And so this warring pair went to work, arriving on the platform just as the doors started to swing open and the holidaymakers began to alight. It was always a joyous moment, thought Miss Dimont, this happy release from confinement into sunshine, the promise of uncountable pleasures ahead. A small girl raced past, her face a picture of joy, pigtails given an extra bounce by the skip in her step.

The routine on these occasions was always the same – if a single celebrity was to be interviewed, he or she would be ushered into the first-class waiting room in order to be relieved of their innermost secrets. If more than one, the likeliest candidate would be pushed in by Terry, while Judy quickly handed the others her card, enquiring discreetly where they were staying and arranging a suitable time for their interrogation.

This manoeuvring took some skill and required a deftness of touch in which Miss Dimont excelled. On a day like today, no such juggling was required – just an invitation to old Gerald to step inside for a moment and explain away his presence in Devon’s prettiest town.

The late holiday crowds swiftly dispersed, the guard completed the task of unloading from his van the precious goods entrusted to his care – a basket of somnolent homing pigeons, another of chicks tweeting furiously, the usual assortment of brown paper parcels. Then the engine driver climbed aboard to prepare for his next destination, Exbridge.

A moment of stillness descended. A blackbird sang. Dust settled in gentle folds and the reporter and photographer looked at each other.

‘No ruddy Hennessy,’ said Terry Eagleton.

Miss Dimont screwed up her pretty features into a scowl. In her mind was the lost scoop of Church v. Law, the clerical challenge to the authority of the redoubtable Mrs March-bank. The uncomfortable explanation to Rudyard Rhys of how she had missed not one, but two stories in an afternoon – and with press day only two days away.

Mr Rhys was unforgiving about such things.

Just then, a shout was heard from the other end of Platform 1 up by the first-class carriages. A porter was waving his hands. Inarticulate shouts spewed forth from his shaking face. He appeared, for a moment, to be running on the spot. It was as if a small tornado had descended and hit the platform where he stood.

Terry had it in an instant. Without a word he launched himself down the platform, past the bewildered guard, racing towards the porter. The urgency with which he took off sprang in Miss Dimont an inner terror and the certain knowledge that she must run too – run like the wind . . .

By the time she reached the other end of the platform Terry was already on board. She could see him racing through the first-class corridor, checking each compartment, moving swiftly on. As fast as she could, she followed alongside him on the platform.

They reached the last compartment almost simultaneously, but Terry was a pace or two ahead of Judy. There, perfectly composed, immaculately clad in country tweeds, his oxblood brogues twinkling in the sunlight, sat their interviewee, Gerald Hennessy.

You did not have to be an expert to know he was dead.

TWO (#ulink_fdac03c3-9daa-59c3-af09-6f297c43da8d)

You had to hand it to Terry – no Einstein he, but in an emergency as cool as ice. He was photographing the lifeless form of a famous man barely before the reality of the situation hit home. Miss Dimont watched through the carriage window, momentarily rooted to the spot, as he went about his work efficiently, quickly, dextrously. But then, as Terry switched positions to get another angle, his eye caught her immobile form.

‘Call the office,’ he snapped through the window. ‘Call the police. In that order.’

But Judy could not take her eyes off the man who so recently had graced the Picturedrome’s silver screen. His hair, now restored to a more conventional length, flopped forward across his brow. The tweed suit was immaculate. The foulard tie lay gently across what looked like a cream silk shirt, pink socks disappeared into those twinkling brogues. She had to admit that in death Gerald Hennessy, when viewed this close, looked almost more gorgeous than in life . . .

‘The phone!’ barked Terry.

Miss Dimont started, then, recovering herself, raced to the nearby telephone box, pushed four pennies urgently into the slot and dialled the news desk. To her surprise she was met with the grim tones of Rudyard Rhys himself. It was rare for the editor to answer a phone – or do anything else useful around the office, thought Miss Dimont in a fleeting aperçu.

‘Mr Rhys,’ she hicupped, ‘Mr Rhys! Gerald Hennessy . . . the . . . dead . . .’ Then she realised she had forgotten to press Button A to connect the call. That technicality righted, she repeated her message with rather more coherence, only to be greeted by a lion-like roar from her editor.

‘Rrr-rrr-rrrr . . .’

‘What’s that, Mr Rhys?’

‘Damn fellow! Damn him, damn the man. Damn damn damn!’

‘Well, Mr Rhys, I don’t really think you can speak like that. He’s . . . dead . . . Gerald Hennessy – the actor, you know – he is dead.’

‘He’s not the only one,’ bellowed Rudyard. ‘You’ll have to come away. Something more important.’

Just for the moment Miss Dim lived up to her soubriquet, her brilliant brain grinding to a halt. What did he mean? Was she missing something? What could be more important than the country’s number-one matinée idol sitting dead in a railway carriage, here in Temple Regis?

Had Rudyard Rhys done it again? The old Vicar’s Longboat Party tale all over again? Walking away from the biggest story to come the Express’s way in a decade? How typical of the man!

She glanced over her shoulder to see Terry, now out of the compartment of death and standing on the platform, talking to the porter. That’s my job, she thought, hotly. In a second she had dropped the phone and raced to Terry’s side, her flapping notebook ready to soak up every detail of the poor man’s testimony.

The extraordinary thing about death is it makes you repeat things, thought Miss Dimont calmly. You say it once, then you say it again – you go on saying it until you have run out of people to say it to. So though technically Terry had the scoop (a) he wasn’t taking notes and (b) he wasn’t going to be writing the tale so (c) the story would still be hers. In the sharply competitive world of Devon journalism, ownership of a scoop was all and everything.

‘There ’e was,’ said the porter, whose name was Mudge. ‘There ’e was.’

So far so good, thought Miss Dimont. This one’s a talker.

‘So then you . . .?’

‘I told ’im,’ said Mudge, pointing at Terry. ‘I already told ’im.’ And with that he clamped his uneven jaws together.

Oh Lord, thought Miss Dimont, this one’s not a talker.

But not for nothing was the Express’s corkscrew-haired reporter renowned for charming the birds out of the trees. ‘He doesn’t listen,’ she said, nodding towards the photographer. ‘Deaf to anything but praise. You’ll need to tell me. The train came in and . . .’

‘I told ’im.’

There was a pause.

‘Mr Mudge,’ responded Miss Dimont slowly and perfectly reasonably, ‘if you’re unable to assist me, I shall have to ask Mrs Mudge when I see her at choir practice this evening.’

This surprisingly bland statement came down on the ancient porter as if a Damoclean sword had slipped its fastenings and pierced his bald head.

‘You’m no need botherin’ her,’ he said fiercely, but you could see he was on the turn. Mrs Mudge’s soprano, an eldritch screech whether in the church hall or at home, had weakened the poor man’s resolve over half a century. All he asked now was a quiet life.

‘The 4.30 come in,’ he conceded swiftly.

‘Always full,’ said Miss Dimont, jollying the old bore along. ‘Keeping you busy.’

‘People got out.’

Oh, come on, Mudge!

‘Missus Charteris arsk me to take ’er bags to the car. Gave me thruppence.’

‘That chauffeur of hers is so idle,’ observed Miss Dimont serenely. Things were moving along. ‘So then . . .?’

‘I come back to furs clars see if anyone else wanted porterin’. That’s when I saw ’im. Just like lookin’ at a photograph of ’im in the paper.’ Mr Mudge was warming to his theme. ‘’E wasn’t movin’.’

Suddenly the truth had dawned – first, who the well-dressed figure was; second, that he was very dead. The shocking combination had caused him to dance his tarantella on the platform edge.

The rest of the story was down to Terry Eagleton. ‘Yep, looks like a heart attack. What was he – forty-five? Bit young for that sort of thing.’

As Judy turned this over in her mind Terry started quizzing Mudge again – they seemed to share an arcane lingo which mistrusted verbs, adjectives, and many of the finer adornments which make the English language the envy of the civilised world. It was a wonder to listen to.

‘Werm coddit?’

‘Ur, nemmer be.’

‘C’rubble.’

Miss Dimont was too absorbed by the drama to pay much attention to these linguistic dinosaurs and their game of semantic shove-ha’penny; she sidled back to the railway carriage and then, pausing for a moment, heart in mouth, stepped aboard.

The silent Pullman coach was the dernier cri in luxury, a handsome relic of pre-war days and a reassuring memory of antebellum prosperity. Heavily carpeted and lined with exotic African woods, it smelt of leather and beeswax and smoke, its surfaces uniformly coated in a layer of dust so fine it was impossible to see: only by rubbing her sleeve on the corridor’s handrail did the house-proud reporter discover what all seasoned railway passengers know – that travelling by steam locomotive is a dirty business.

She cautiously advanced from the far end of the carriage towards the dead man’s compartment, her journalist’s eye taking in the debris common to the end of all long-distance journeys – discarded newspapers, old wrappers, a teacup or two, an abandoned novel. On she stepped, her eyes a camera, recording each detail; her heart may be pounding but her head was clear.

Gerald Hennessy sat in the corner seat with his back to the engine. He looked pretty relaxed for a dead man – she wondered briefly if, called on to play a corpse by his director, Gerald would have done such a convincing job in life. One arm was extended, a finger pointing towards who knows what, as if the star was himself directing a scene. He looked rather heroic.

Above him in the luggage rack sat an important-looking suitcase, by his side a copy of The Times. The compartment smelt of . . . limes? Lemons? Something both sweet and sharp – presumably the actor’s eau de cologne. But unlike Terry Eagleton Miss Dimont did not cross the threshold, for this was not the first death scene she had encountered in her lengthy and unusual career, and from long experience she knew better than to interfere.

She looked around, she didn’t know why, for signs of violence – ridiculous, really, given Terry’s confident reading of the cause of death – but Gerald’s untroubled features offered nothing by way of fear or hurt.

And yet something was not quite right.

As her eyes took in the finer detail of the compartment, she spotted something near the doorway beneath another seat – it looked like a sandwich wrapper or a piece of litter of some kind. Just then Terry’s angry face appeared at the compartment window and his fist knocked hard on the pane. She could hear him through the thick glass ordering her out on to the platform and she guessed that the police were about to arrive.

Without pausing to think why, she whisked up the litter from the floor – somehow it made the place look tidier, more dignified. It was how she would recall seeing the last of Gerald Hennessy, and how she would describe to her readers his final scene – the matinée idol as elegant in death as in life. Her introductory paragraph was already forming itself in her mind.

Terry stood on the platform, red-faced and hopping from foot to foot. ‘Thought I told you to call the police.’

‘Oh,’ said Miss Dimont, downcast, ‘I . . . oh . . . I’ll go and do it now but then we’ve got another—’

‘Done it,’ he snapped back. ‘And, yes we’ve got another fatality. I’ve talked to the desk. Come on.’

That was what was so irritating about Terry. You wanted to call him a know-it-all, but know-it-alls, by virtue of their irritating natures, do not know it all and frequently get things wrong. But Terry rarely did – it was what made him so infuriating.

‘You know,’ he said, as he slung his heavy camera bag over his shoulder and headed towards his car, ‘sometimes you really can be quite dim.’

*

Bedlington-on-Sea was the exclusive end of Temple Regis, more formal and less engagingly pretty than its big sister. Here houses of substance stood on improbably small plots, with large Edwardian rooms giving on to pocket-handkerchief gardens and huge windows looking out over a small bay.

Holidaymakers might occasionally spill into Bedlington but despite its apparent charm, they did not stay long. There was no pub and no beach, no ice-cream vendors, no pier, and a general frowning upon people who looked like they might want to have fun. It would be wrong to say that Bedlingtonians were stuffy and self-regarding, but people said it all the same.

The journey from the railway station took no more than six or seven minutes but it was like entering another world, thought Miss Dimont, as she and Herbert puttered behind the Riviera Express’s smart new Morris Minor. There was never any news in Bedlington – the townsfolk kept whatever they knew to themselves, and did not like publicity of any sort. If indeed there was a dead body on its streets this afternoon, you could put money on its not lying there for more than a few minutes before some civic-minded resident had it swept away. That’s the way Bedlingtonians were.

And so Miss Dimont rather dreaded the inevitable ‘knocks’ she would have to undertake once the body was located. Usually this was a task at which she excelled – a tap on the door, regrets issued, brief words exchanged, the odd intimacy unveiled, the gradual jigsaw of half-information built up over maybe a dozen or so doorsteps – but in Bedlington she knew the chances of learning anything of use were remote. Snooty wasn’t in it.

They had been in such a rush she hadn’t been able to get out of Terry where exactly the body was to be found, but as they rounded the bend of Clarenceux Avenue there was no need for further questions. Ahead was the trusty black Wolseley of the Temple Regis police force, a horseshoe of spectators and an atmosphere electric with curiosity.

At the end of the avenue there rose a cliff of Himalayan proportions, a tower of deep red Devonian soil and rock, at the top of which one could just glimpse the evidence of a recent cliff fall. As one’s eye moved down the sharp slope it was possible to pinpoint the trajectory of the deceased’s involuntary descent; and in an instant it was clear to even the most casual observer that this was a tragic accident, a case of Man Overboard, where rocks and earth had given way under his feet.

Terry and Miss Dimont parked and made their way through to where Sergeant Hernaford was standing, facing the crowd, urging them hopelessly, pointlessly, that there was nothing to see and that they should move on.

The sergeant spoke with forked tongue, for there was something to see before they went home to tea – there, under a police blanket, lay a body a-sprawl, as if still in the act of trying to save itself. But it was chillingly still.

‘Oh dear,’ said Miss Dimont, conversationally, to Sergeant Hernaford, ‘how tragic.’

‘’Oo was it?’ said Terry, a bit more to the point.

Hernaford slowly turned his gaze towards the official representatives of the fourth estate. He had seen them many times before in many different circumstances, and here they were again – these purveyors of truth and of history, these curators of local legend, these nosy parkers.

‘Back be’ind the line,’ rasped Hernaford in a most unfriendly manner, for just like the haughty Bedlingtonians he did not like journalists. ‘Get back!’

‘Now Sergeant Hernaford,’ said Miss Dimont, stiffening, for she did not like his tone. ‘Here we have a man of late middle age – I can see his shoes, he’s a man of late middle age – who has walked too close to the cliff edge. When I was up there at the top last week there were signs explicitly warning that there had been a rockfall and that people should keep away. So, man of late middle age, tragic accident. Coroner will say he was a BF for ignoring the warnings; the Riviera Express will say what a loss to the community. An extra paragraph listing his bereaved relations, there’s the story.

‘All that’s missing,’ she added, magnificently, edging closer to the sergeant, ‘is his name. I expect you know it. I expect he had a wallet or something. Or maybe one of these good people—’ she looked round, smiling at the horseshoe but her words taking on a steely edge ‘—has assisted you in your identification. He has clearly been here for a while – your blanket is damp and it stopped raining an hour ago – so in that time you must have had a chance to find out who he is.’

She smiled tightly and her voice became quite stern.

‘I expect you have already informed your inspector and, rather than drive all the way over to Temple Regis police station and take up his very precious time getting two words out of him – a Christian name and a surname, after all that is all I am asking – I imagine you would rather he did not complain to you about my wasting his very precious time.

‘So, Sergeant,’ she said, ‘please spare us all that further pain.’

It was at times like this that Terry had to confess she may be a bit scatty but Miss Dimont could be, well, remarkable. He watched Sergeant Hernaford, a barnacle of the old school, crumble before his very eyes.

‘Name, Arthur Shrimsley. Address, Tide Cottage, Exbridge. Now move on. Move on!’

Judy Dimont gazed owlishly, her spectacles sliding down her convex nose and resting precariously at its tip. ‘Not the Arthur . . .?’ she enquired, but before she could finish, Terry had whisked her away, for Hernaford was not a man to exchange pleasantries with – that was as much as they were going to get. As they retreated, he pushed Miss Dimont aside with his elbow while turning to take snaps of the corpse and its abrasive custodian before pulling open the car door.

‘Let’s go,’ he urged. ‘Lots to do.’

Miss Dimont obliged. Dear Herbert would have to wait. She pulled out her notebook and started to scribble as Terry noisily let in the clutch and they headed for the office.

Already the complexity of the situation was becoming clear; and no matter what happened next, disaster was about to befall her. Two deaths, two very different sets of journalistic values. And only Judy Dimont to adjudicate between the rival tales as to which served her readers best.

If she favoured the death of Gerald Hennessy over the sad loss of Arthur Shrimsley, local readers would never forgive her, for Arthur Shrimsley had made a big name for himself in the local community. The Express printed his letters most weeks, even at the moment when he was stealing their stories and selling them to Fleet Street. Rudyard Rhys, in thrall to Shrimsley’s superior journalistic skills, had even allowed him to write a column for a time. But narcissistic and self-regarding it turned out to be, and of late he was permitted merely to see his name in print at the foot of a letter which would excoriate the local council, or the town brass band, or the ladies at the WI for failing to keep his cup full at the local flower show.

There was nothing nice about Arthur Shrimsley, yet he had invented a persona which his readers were all too ready to believe in and even love. His loss would be a genuine one to the community.

On the other hand, thought Miss Dimont feverishly, as Terry manoeuvred expertly round the tight corner of Tuppenny Row, we have a story of national importance here. Gerald Hennessy, star of Heroes at Dawn and The First of the Few, husband of the equally famous Prudence Aubrey, has died on our patch. Gerald Hennessy!

The question was, which sad passing should lead the Express’s front page? And who would take the blame when, as was inevitable, the wrong choice was made?

THREE (#ulink_e330081a-4ea5-501a-a953-ccb41607f86f)

It is remarkable, thought Miss Dimont, as her Remington Quiet-Riter rattled, banged, tinged and spat out page after page of immaculately typed copy addressing the recent rise in the death rate of Temple Regis. It really is remarkable . . .

Her typing came to a halt while she completed the thought. It’s remarkable how when there’s an emergency everybody just melts away. Here I am, writing one of the greatest scoops this newspaper has ever been lucky enough to have, and with press day looming, and everyone’s gone home.

She was right to feel nettled. The newsroom resembled the foredeck of the Mary Celeste, with all the evidence of apparent occupancy but none of the personnel. It was barely six o’clock but the crew of this ghost ship had jumped over the side, leaving Miss Dimont and Terry Eagleton alone to steer it to safety. Call it cowardice in the face of a major story, call it what you like, they’d all hopped it.

Around her, tin ashtrays still gave off the malodorous evidence that people once worked here. Teacups were barely cold. Someone had forgotten to put away the milk. Someone else had forgotten to shut the windows – strictly against company regulations – and the soft late summer breeze caused the large sign over the editorial desks to gently undulate, as if a punkah wallah had been employed especially to fan Miss Dimont’s fevered brow.

This sign was Rudyard Rhys’s urgent imprecation to staff to do their duty. ‘Make It Fast,’ he had written, ‘Make It Accurate.’ To which some wag had added in crayon, ‘Make It Up.’

There were wags aplenty at the Express. In the corner by Miss Dimont’s desk was a gallery of hand-picked photographs, a rich harvest of the paper’s weekly editorial content, which showed off the town’s newly-weds. For some reason the office jokers had chosen to pick the ugliest and most ill suited of couples – brides with snaggly teeth, grinning grooms recently released from the asylum. It was called the ‘Thank Heavens!’ board – thank heavens they found each other!

This joke had been running for a good few years and it was remarkable that on this evidence, in beauteous Temple Regis, there could be quite so many people – parents now, grandparents even – making such a lacklustre contribution to the municipality’s gene pool. It was rather a cruel joke of which Miss Dimont did not approve.

Turning away, she ladled in some extra paragraphs of glowing praise to the life and achievements of Arthur Shrimsley, adding a few of her own jokes – ‘His life was enriched by the sight of a good story’ (he stole enough of them from the Express and peddled them to Fleet Street). ‘He enjoyed the very sight of a typeface’ (if it showed his name in big enough print). ‘He was fearless’ (rude), ‘adept’ (as thieves so often are), ‘a consummate diplomat’ (liar) . . . ‘wise’(bore).

Gerald Hennessy she had already dispatched to the printer – a full page, motivated in part by his fame and the shock of the death of one so esteemed in humble Temple Regis, but also from a sense of personal loss: Miss Dimont had of course never met the actor before their recent silent encounter, but like all his fans, she felt she knew him intimately. There was something in his character as a human being which informed the heroic parts he played, her Remington had tapped out – instinctively his many admirers knew him to be the right choice to represent the dead and the dying of the recent war, as well as the nimble, the bold and the picaresque. It truly was a great loss to the nation and Miss Dimont, in writing this first of many epitaphs, captured the spirit of the man con brio.

The tumult from her typewriter finally ceased and, after a reflective pause, Miss Dimont fetched out the oilskin cover to put it to bed for the night. She had missed her choir practice, but then she already knew by heart the more easily accomplished sections of the Fauré Requiem with which the Townswomen’s Guild Chorus would be serenading Temple townsfolk in a fortnight’s time. She went along as much for the company as anything else, for Miss Dimont was a most able sight-reader with a melodious contralto that any choirmaster would give his eye teeth for. She did not need to practise.

She heaved a sigh of relief that it was over. How she would have hated to work on a daily newspaper, where deadlines assail one every twenty-four hours and there is no time to breathe! As she gathered up her things, her eyes travelled round the abandoned newsroom, about the most dreary working environment one could possibly imagine, and yet the very place where history was made. Or if not made, then recorded – for just as there is no point in climbing Mount Everest if there is no one there to chronicle it, so too what pleasure can there be in winning Class 1 Chrysanthemums (incurved) if not to rub their competitors’ nose in it? All human life was here, recorded in detail by the diligent Express.

The room was dusty, untidy, littered, and from the files of back copies lying under the window there rose the sour odour of drying newsprint. Desks were jammed together and covered in all the debris which goes with making a newspaper – rulers, pencils, litter galore, old bits of hot metal used as paperweights. Coats were slung over chairbacks as if their owners might shortly return.

Being a reporter had not been what Miss Dimont was put on this earth for – there had been another career, most distinguished, which preceded her present occupation – but she was a very good one. Except, of course, on occasions like the Regis Conservative Ball last winter, but if ever anyone had the temerity to bring that up, she rose above.

Now she must find Terry, beavering away in the darkroom, and get him to take her back to Bedlington, where, in their rush to get back to the office, her trusty Herbert had been abandoned.

As she made towards the photographic department, she heard the sound of a door opening, followed by a muffled squeak. Miss Dimont stopped dead in her tracks. There was nobody else in the building except her and Terry – what was that rustling sound, that parrot-like noise?

She swung round to be faced by a ghostly apparition – white-faced, grey-haired, long claw-like fingers, a rictus of a smile upon its features.

‘Purple,’ it whispered.

‘Oh, hello, Athene,’ started Miss Dimont, ‘you gave me such a fright.’

Then, like the Queen of Sheba, Athene Madrigale sailed into the room, her aura wafting before her in the most entrancing way. She was rarely seen in daylight – indeed she was rarely seen at all – but despite her advanced age she remained one of the pillars upon which the Riviera Express had built its reputation. For Athene wrote the astrology column.

What most Express readers turned to each Friday morning, immediately after looking to see who’d died or been had up in court, were Athene’s stars. In Temple Regis, you never had a bad day with Athene.

‘Sagittarius: Oh! How lucky you are to be born under this sign,’ she would trill. ‘Nothing but sunshine for you all week!

‘Capricorn: All your troubles are behind you now. Start thinking about your holidays!

‘Cancer: Someone has prepared a big surprise for you. Be patient, it may take a while to appear, but what pleasure it will bring!’

These were not the scribblings of a simpleton but rare emanations from under the deeply spiritual cloak which adorned Athene Madrigale’s person. Though not quite as others – her rainbow-hued costumes set her apart from the average Temple Regent, not to mention the turquoise fingernails and violet smile – she exuded nothing but beauty and calm. It is quite likely her name was not Athene, but nobody felt the need to question it while she predicted such wonderful things for the human race.

Equally, nobody was quite sure where Athene lived – some said in a mystical bubble on the roof of the Riviera Express – but what is certain is that she needed the protection of night to save her from being swamped by an adoring public, her aura too precious to be jostled. It is true Miss Dimont encountered her from time to time, but only because she would return late from council meetings to diligently write into the night until her work was done. Most reporters on late jobs kept it in their notebook and typed it up next day.

‘Purple,’ whispered Athene again.

‘But going green?’ replied Miss Dimont.

‘Mercifully for you, dear.’

‘It’s been a something of a day, Athene.’

‘I can tell, my dear, do you want to sit down and talk about it?’

This was a rare invitation and one not to be denied. The strain of the day’s activities had taken its toll on the reporter and she was grateful for a sympathetic ear. Almost as if by magic a cup of hot, sweet tea appeared in front of her and Athene arranged her rainbow clothes in a most attractive way on the seat opposite, the manner in which she did it suggesting she had all the time in the world. Even though she had yet to write the astrology page!

‘It’s not the first time I’ve seen dead bodies,’ started Miss Dimont.

‘No, dear. That chemist with the pill-making machine.’

‘Yes.’

‘Lady Hellebore and the gardener.’

‘I’d almost forgotten that.’

‘The Temple twins.’

‘So many, oh dear . . .’

Athene knew when to move on. ‘What is it, then, Judy? What’s wrong?’

‘I don’t know,’ came the reply. ‘Maybe it’s seeing two fatalities in one day. Two such different people – one so loved, the other so hated. But both lives at an end, equally, as if God cannot differentiate between good and evil.’

‘That’s not really what’s upsetting you, though,’ said Athene gently, for she was gifted with a greater understanding of people’s travails. ‘It’s something else.’

Miss Dimont stirred her tea. ‘Yes,’ she said finally. ‘I just feel something’s wrong.’

‘Like you did with the twins?’

‘Oh . . . oh yes, something is wrong. I’ve been over it while I was writing my copy but I can’t see what it is. There was something about Gerald Hennessy, he sat there so calmly, but he was pointing – pointing!’

‘At what, dear?’

‘Well, nothing. I thought when I looked at him that he was accusing someone. There was just that look on his face. Somehow trying to say something, but not quite managing it.’

‘Go on.’

‘And then, when we went to Bedlington, the way he – oh, did you know Arthur Shrimsley was dead?’

‘Couldn’t happen to a nicer chap,’ said Athene crisply, her perpetual sun slipping over the horizon for a brief second.

‘Mm?’ said Miss Dimont, not quite believing such harsh words could steal from the benign countenance. ‘Well, anyway, there was just something about it all. It wasn’t just Sergeant Hernaford, though he was obnoxious, it wasn’t even the way the body was lying. Just something about the way Mr Shrimsley had managed to get through that barrier right out on to the cliff edge. It didn’t seem . . . logical. It didn’t add up.’

Athene did not know what Judy was talking about, but she did know how to refresh a teacup. Once done, she sat there expectantly, waiting for the next aperçu.

‘And, er, that’s it really’ said Miss D, disappointingly.

Miss Madrigale was far too conversant in the ways of the parallel universe to see a complete lack of evidence in what she had just heard. There was something here, most certainly. She was glad to see that she had eradicated the purple from Miss Dimont’s aura and that it was almost completely restored to a healthy green.

‘You’ve been such a help, Athene,’ said Judy gratefully, but as the words formed in her mouth, she awoke to the fact that Athene had completely disappeared.

‘Still ’ere?’ barked Terry Eagleton, who had blustered into the room with a time-for-a-pint look on his face, startling Athene away.

‘Yes. And you’ve got to take me back to Bedlington to pick up Herb— the moped.’

‘Want to see what we’ve got?’ asked Terry, eager as ever to show off the fruits of his day’s labours. ‘Some great shots!’

‘Pictures of dead bodies? Printed in the Express?’ marvelled Miss Dimont. ‘Never in a month of Sundays, Terry, not while King Rudyard sits upon his throne!’

‘Yers, well. ’ Terry sniffed. ‘I’ll keep them back for the nationals. Take a look.’

And since Judy Dimont relied on Terry for her lift back to Bedlington, she obliged. The pair walked through into the darkroom, where, hanging from little washing lines and attached by clothes pegs, hung the 10 x 8 black-and-white prints which summed up the day’s events. They were not a pretty sight.

On the other hand, they were: an eery light percolated the first-class carriage containing the body of Gerald Hennessy (‘f5.6 at 1/60th,’ chirped Terry proudly). The image was so dramatic that, honestly, it could have been a publicity still from one of his forthcoming films. Terry had caught the actor in profile, his jaw as rugged as ever, the mop of crinkly hair just slightly ruffled, the tweed suit immaculate.

The hand was raised, index finger extended in imperious fashion. Gerald’s lips appeared to be pronouncing something. It was indeed a hero’s end – until Miss Dimont noticed the litter on the carriage floor. ‘Thank heavens I got rid of that!’ she told herself.

Her eyes switched to the pictures of Arthur Shrimsley, or at least the police blanket which covered Shrimsley – very little to boast about here in pictorial terms, she thought. A blanket – that’s not going to earn Terry a bonus. But, as she moved along the washing line examining the various angles he’d taken, the reality of what she’d seen, with her own eyes, supplanted the prints hanging before her. She recalled the odd feeling she’d had when craning around the obstructive body of Sergeant Hernaford and, as her eyes slid back to Terry’s prints, she realised why. In one shot – and one shot only – Terry had captured a different angle, which showed a hand, as well as the middle-aged man’s shoes, protruding from the blanket.

The hand was clutching a note.

Miss Dimont stepped back. ‘Surely not,’ she said to herself. ‘Surely not!’

‘Surely what?’ said Terry, busy admiring his f5.6 at 1/60th. The light playing over Gerald Hennessy’s rigid form, the etching of the profile, the shaft of light on the extended forefinger . . . surely, a contender for Photographer of the Year?

‘He can’t have committed suicide. Not Arthur Shrimsley. Why, he was the most self-regarding person I ever met!’

‘Speaking ill of the dead, Miss Dim.’

‘That’s as maybe, Terry,’ she snipped, ‘but I don’t remember you ever saying anything nice about him.’

‘Man was a chump,’ but Terry looked again at the picture in question. ‘You’re right,’ he said. ‘Looks like a note in his hand. Has to be a suicide. Unless it was a love letter to himself, of course.’

‘Terry!’

The pair emerged from the darkroom, each wreathed in their separate thoughts. That last portrait of Gerald Hennessy is indeed a work of art, marvelled Terry, which might spring me from a lifetime’s wageslavery at the Express.

Miss Dimont meanwhile was struggling to arrive at a logic which would allow the awful but never less than self-satisfied Arthur Shrimsley to do away with himself.

Then came the moment.

Miss Dim had had them before – for example when she discovered Mrs Sharpham’s long-lost cat safe and well in the airing cupboard, when she suddenly knew why Alderman Jones had really bought that farm.

‘Just a moment, Terry!’

She was back in the darkroom, staring hard at Terry’s masterpiece. Part of her had admired, the other part recoiled from, this undeniable award-winner. When she’d looked before she had concentrated on Hennessy’s face, the pointing finger, the irritating litter which nearly spoilt the picture. Now she concentrated on the light beams filtered by Terry’s use of lens – light beams flooding from outside, throwing shadows on the thick carpet beneath the actor’s feet.

‘Come back here, Terry,’ said Miss Dimont, very slowly. There was something in her tone of voice which made the photographer obey.

‘Do you have a magnifying glass?’ she asked.

‘Got one somewhere. But you don’t need—’

‘Magnifying glass, Terry,’ said Miss Dimont crisply. ‘And another for yourself if you have one.’

He obliged. Both moved forward towards the print.

‘Do you notice Gerald Hennessy’s hand – his index finger?’ she asked.

‘Yes, the way I shot it, the light does a nice job of—’

‘The finger, the finger!’ interrupted Miss Dimont urgently.

‘Yes,’ said Terry, not seeing anything at all.

‘The tip of it is dirty,’ she said slowly. ‘The rest of his hand appears clean.’

‘Ur. Ah.’

‘Now look at the window by his side. D’you see?’

‘What am I looking for?’

‘Where you have been so clever with the light. The light streaming through the window,’ said Miss Dimont. ‘The window is covered in a thin layer of dust. Your f8 at 1/30th has caught something on the window which you couldn’t see – and neither could I – when we were in the carriage. Do you see what it is?’

Terry moved closer to the print, his eyes readjusting to the moving magnifying glass. ‘Ah,’ he said. ‘Yes. Looks like he was writing something on the window.’

‘What does it say?’

‘Not much . . . just three letters as I can make out . . .’

‘And they are?’ asked Miss Dimont, as soft as silk.

‘M . . . U . . . R . . .’

FOUR (#ulink_bb104662-8baf-5da3-8d9d-4332ba24dafb)

It was the fashion to mock the overblown grandeur of Temple Regis Magistrates’ Court, though it was actually rather pretty – redbrick, Edwardian, nicely stained glass and masses of oak panelling. Its solidity added weight to the sentences handed down by the Bench.

Miss Dimont, who had spent more Tuesdays and Thursdays on the well-worn press bench than she cared to recall, approached Mr Thurlestone, the magistrates’ clerk, for a copy of the day’s charge sheet. The bewigged figure turned away his head as she neared his desk and held up the requisite document as if it had recently been recovered from a puddle. He did not acknowledge her.

Curious, because it was hard to ignore such an amiable person as Miss Dimont.

After all, Mr Thurlestone had never been the object of the angry huffing and puffing, and the hefty biffing, from which Miss Dimont’s Remington Quiet-Riter weekly delivered its judgements. He’d never had to submit to a sharp dressing-down in print like the disobliging council officials she sometimes excoriated, nor had he ever been on the receiving end of the occasional furies directed at the judges at the Horticultural Society for the self-serving way they arrived at their deliberations.

In fact, Miss Dimont had always been perfectly sweet to Mr Thurlestone, but still he snubbed her.

Perhaps it was because, though this was his court and he virtually told the magistrates what to think, no mention of his life’s work was ever made in the Express. The daily doings he oversaw in this room, with its heavy gavel and magnificent royal coat of arms, filled many pages of the newspaper, and quite often the stern words of one or other of the justices sitting on the bench behind him made headlines:

‘JP ORDERS MISSIONARY “GO BACK TO AFRICA”’ (at the conclusion of a lengthy case concerning an unfortunate mix-up in the public lavatories behind the Market Square).

‘MOTHER OF SIX TOLD “ONE’S ENOUGH” BY THE BENCH’ (the joys of bigamy).

‘“YOU BRING SHAME TO TEMPLE REGIS,” RULES JP’ (something about Boy Scouts; Miss Dimont rose above).

Mr Thurlestone, for all his legal training, his starched wing collar and tabs, and his ancient and rather disreputable wig, yearned for recognition. But he would wait in vain, for he was no match for the vaulted egos, the would-be hangmen and the retired businessmen who made up his cadre of Justices of the Peace – for they it was who made the headlines.

Chief among their Worships, though not cast in quite the same mould, was Mrs Marchbank, the chairman of the Bench, or, to give her the full roll-call, The Hon. Mrs Adelaide Marchbank, MBE, JP.

In many ways Mrs March, as she was generally known, summed up the aspirations of the town – hard-working, exquisitely turned out, ready always with a smile and an encouraging word. Fortunate enough to be married to the brother of Lord Mount Regis, she gave back to life far more than she ever took. Her tall, grey-haired good looks were tempered by a sharply regal streak, the combination of which went down well in a part of the country largely deprived of real Society. Everyone agreed she wore a hat exquisitely.

Her serene countenance often graced the pages of the Riviera Express, whether as chairman of this, a subscriber to that, or simply for being an Honourable. A lacklustre fashion show, staged by the Women’s Institute in a determined bid to hold down the town’s hemlines, would be sure of coverage if the smiling Mrs March were to grace the front row (though – poor models! – the photograph which accompanied the article would invariably feature the magistrate, not the matrons).

But Miss Dimont found it hard to like her.

And Mrs March did not much like Miss Dimont.

There was something scholarly about the corkscrew-haired reporter, something passionate, something humane – qualities Mrs March, as she peered down into the court, recognised that she herself did not possess. Apogee of correctness and charm though she was, the steely inner core which made her a most excellent magistrate (if too firm on occasion) disallowed her the luxury of these finer attributes.

For her part Miss Dimont hardly helped matters; she did not care for the unquestioning submission to privilege. On a number of occasions, she had pointed out in print where the Bench, under the leadership of Mrs March, had forgotten that old Gilbertian thing of letting the punishment fit the crime. Handing down a week’s custodial sentence simply for having supped too deep in the Cap’n Fortescue did not find favour with this fair-minded reporter, and she did not mind saying so on the Opinion page.

For some reason Mrs March took these lightly worded criticisms badly. Were she less the Queen of Temple Regis, one might almost suppose that she felt threatened, but that could not be – her position in the town outranked the mayor, the rector, the chairman of Rotary, even the chief constable. A lowly reporter on the local rag presented no threat to her standing, no matter what appeared in print, and yet the unfinished business between the pair often had the power to lower the temperature in court by a good few degrees.

‘All rise,’ barked Mr Thurlestone. ‘The court is in session.’

This morning there were usual crop of licensee applications – a form of morning prayers during which one could allow one’s mind to wander – before the main business of the day began. Miss Dimont’s eyes ran down the charge sheet automatically registering the petty thefts, drunken misdemeanours, traffic infringements and insults to civic pride which did nothing to diminish Temple Regis in the eyes of the world, but did not exactly shore up her faith in man’s capacity to find that higher path.

‘Call Albert Lamb!’

A furtive-looking fellow stepped forward, eyeing the court suspiciously as if one of them had stolen his bicycle clips.

‘Are you Albert John Walker Lamb?’

‘Yus.’

‘Albert Lamb, you are charged with drunkenness in a public place. How do you plead?’

‘Just a shmall one, shank you.’

Miss Dimont found, with her combination of immaculate shorthand and a sense of when to rest her pencil, that court reporting was a bit like lying on a lumpy sofa with a box of chocolates – the seating was uncomfortable but the work largely enjoyable. Gradually, as one traffic accident after another resolved itself, she allowed her mind to wander back to the events of the previous day.

All in all, it had been rather wonderful, snatching success as she had from the jaws of defeat – one moment no stories, the next, two – on Page One!

‘Call Ezra Poundale.’

‘Call Gloria Monday.’

‘Call . . .’

What kept coming back to her, however, was the startling discovery she had made with Terry’s magnifying glass. The pointed finger blackened by dust, the secret message left by the dying actor! The thrill of an even better story!! But what seemed certain at first examination seemed less so at second glance, and despite Terry obligingly putting another print through the bath to see if it came up more clearly, it was impossible to say that what was scrawled in the window-dust really was M . . . U . . . R . . .

She had ridden the trusty Herbert back to the railway station this morning in the hope of examining the carriage more closely, but the Pullman coach had been detached from the rest of the train and shunted into a siding where the Temple Regis police had thrown a barrier around it. She was forcefully reminded she was not allowed anywhere near – Hernaford’s revenge for yesterday’s small triumph in Bedlington.

There was no sense, she felt, that the police were treating this as anything other than a routine inquiry. She wondered, not for the first time in her eventful life, whether she wasn’t reading too much into it all, jumping at shadows.

This morning the cases seemed to drag on, and the luncheon recess came as a merciful release. Normally, Miss Dimont joined like-minded members of the court proceedings for lunch in their unofficial canteen, the Signal Box Café, but she needed time to think. She boarded one of Temple’s green and cream tourist buses and took a threepenny ride down to the promenade.

She alighted at her favourite spot by the bandstand and walked towards the shore. Bathed now in late summer sunlight, the turquoise sea stretched out to infinity, its wave-tops like glass beads glittering and cascading over the horizon. The sky was cloudless and a shade of innocent blue. Through the haze she could see fishing boats sliding out to meet the incoming tide while wise old seagulls circled in the heat, lazily awaiting their opportunity.

‘This is why I am here,’ said Miss Dimont, only half to herself. ‘This is paradise.’

When compared to the fusty atmosphere of the Magistrates’ Court, she was right. The irritants which go with any seaside town – late holidaymakers fussing over the price of an ice cream, Teddy boys with nothing better to do than comb their greasy hair and hang about with intent, or the eternal scourge of bottles abandoned on the beach – these things Miss Dimont did not see. The air was still, the only sound that eternal two-part harmony of surf and gulls.

She sat quite still on a bench and dragooned the various components of her considerable intellect into focusing on the events of the past twenty-four hours.

Last night there had been the shock, still with her, of confronting one of the most famous faces in the land so close upon the moment of his death. What she saw, what she had not seen . . . what did it amount to? In the bright hot sun it was hard to believe that in the darkroom with Terry by her side, both with magnifying glasses to their noses, she could smell murder. Apart from anything else there were no signs of violence, nothing to disturb the pristine tranquillity of that Pullman coach compartment – nothing sinister in the atmosphere, nothing disturbed.

But she had seen bodies like that before, and they hadn’t died from a heart attack.

And yet her suspicions no longer seemed quite real, and so she turned instead to the question of Arthur Shrimsley. The fleeting glimpse of the note in his hand gave more than a hint that something was amiss. Miss Dimont had second sight about such things, as in when she found old Mrs Bradley’s lost diamond ring in the clothes-peg basket. It had been a magpie, she deduced. Missing for a fortnight, but Miss Dimont intuited.

She had the same feeling now.

If there was a note, it meant something – the difficulty being, what? Mr Shrimsley, as Terry crisply summarised, loved himself far too much to contemplate self-destruction. What did strike as odd was that Sergeant Hernaford appeared to have done nothing about it. Shrimsley must have fallen down the cliff a good ninety minutes before she and Terry arrived on the scene – wouldn’t he, while searching the man’s wallet to establish his identity, have plucked the note from the man’s lifeless fingers? Was police procedure so strict these days he would leave it to the detectives to pick up the paper and digest its contents? She didn’t think so, in fact if anything the opposite.

Miss Dimont closed her eyes and let the sun do its work.

‘Judy, there you are!’

Miss Dimont struggled for a moment and blinked. She had fallen asleep. There before her was Betty Featherstone, her friend and enemy – the one who was given the best stories, the one whose byline generally graced the front page of the Express. There was little animosity between the two over this – both knew that when it came to ferreting out stories, getting interviewees to confess, or even just how fast one could type or take shorthand, there was no competition. Yet Betty retained her competitive edge by doing no wrong in the eyes of Rudyard Rhys, whereas Miss Dim . . .

‘Where were you last night?’ quizzed the excitable Betty. ‘We had the devil’s own job with the Agnus Dei.’

Miss Dimont was shaken out of her somnolent meditation. ‘Well,’ she said slowly, ‘I don’t know if you heard, Betty, but we had two deaths yesterday. I was quite busy with the—’

‘I know, I know,’ trilled Betty, her blonde bob dancing a tango on top of her head. ‘What a day for all of us! That planning committee went on interminably, and I almost didn’t make the—’

‘Choir practice,’ remembered Miss Dimont. ‘Lord, I forgot all about it! You see, we were late in the office and—’

‘Yes, Rudyard said you left the window open,’ said Betty accusingly. She liked to be in the right, or was it she liked Judy to be in the wrong? ‘You know it’s against regulations. He went on for quite some time about it. I told him it wasn’t my fault when he complained to me, and then Terry said—’

‘Terry could have shut it just as easily as me,’ said Miss Dimont, now thoroughly awake and feeling peppery.

‘Anyway,’ said Betty, smoothing her pink sundress, ‘I’ve been looking everywhere for you. The court, the Signal Box, everywhere . . . you have to come back to the office.’

‘I’ve half-a-dozen cases to cover this afternoon.’

‘Mr Rhys wants you back in the office,’ said Betty smugly. ‘Something about those dead bodies.’

The way she said ‘dead bodies’, you knew Betty had never seen one. Betty didn’t care to think about death.

‘Come on, then,’ she said. And the two set off companionably enough – for in Temple Regis it was not easy to find a friend in their line of work.

Everywhere there were still signs of the conflict whose name populated every other sentence uttered in Temple Regis. Though ‘the War’ had largely passed the town by, its effects had not. Bereaved families were still accorded a special respect, the services held around the War Memorial were well attended, the town’s British Legion club was a thriving concern – and though its brightly lit bar turned out its fair share of over-lubricated fellows on a Friday and Saturday night, they were by common consent not to be subject to the attentions of the police or the Bench.

On the beach, at the far end of the promenade, rolls of rusty barbed wire bore witness to the town’s long-ago preparations for invasion. Since the declaration of peace the gorgeous white sands had been swept again and again in case a defensive mine still lurked below the surface. Fire hydrants, their red paint peeling, dotted the pavements here and there. And military pillboxes, overgrown with buddleia and cracking at the corners, still stood on forlorn sentry duty – tired, overlooked, perceived now as an eyesore where once they had been the very bastions of liberty.

The walk back to the office took in all this, but Judy and Betty were deep into the politics of their choir – Jane Overbeck’s too-strident soprano, how Mabel Attwater came in late at the beginning of every line (‘well, dear, she is eighty-three’), why the tea was always cold when they stopped for a break. Their conductor Geraldine Brent was a short, energetic woman with eyes that burnt like blazing coals – she instilled in her flock such a sense of urgency and importance in their delivery of Gabriel Fauré’s sublime work that the composer himself would have left off his rehearsals with the cherubim and seraphim to smile down, especially upon their forthcoming performance at St Margaret’s Church.

No summons from Rudyard Rhys was so urgent that it could not wait until Judy and Betty had bought their ice-cream from John, the one-armed ‘Stop Me and Buy One’ vendor who strategically placed his tricycle-tub on the corner where the promenade ended and the town proper started – only fourpence-ha’penny a brick. Then a quick dash into the Home and Colonial Stores.

‘Three slices of ham, please.’

‘One and six, madam.’

‘Pound of sugar – can you pour it specially? You never know how long those bags have been sitting there.’

‘Got a new bag of broken biscuits. Fresh in, thruppence to you.’

And then the air filled with the sound and smell of that most glorious luxury – coffee beans being ground – a recent innovation now that rationing was over. Both women sighed over their rough blue-paper prizes with their precious contents.

Fortified by these invigorating delays they arrived at the Riviera Express in excellent spirits, but one sight of Rudyard Rhys striding down the newsroom towards them sent Betty scuttling away.

‘About time,’ rasped Rudyard. ‘I won’t ask where you’ve been,’ he added, eyeing the Home and Colonial bag.

Miss Dimont was unbowed by the glowering presence – she’d seen it too often before.

‘Yes, Mr Rhys? You know there are six cases in court this afternoon? ‘Three traffic, but then there’s—’

‘Inquests!’ snapped Rudyard. ‘Inquests!’

‘Yes, Mr Rhys?’

‘You forgot, Miss Dim—’ he dwelt heavily upon these words ‘—to mention anything in your reports about the inquests on Hennessy and Shrimsley.’

‘Oh!’ said Miss Dimont, colouring visibly.

‘There are inquests to be held, Miss Dim,’ snarled Rhys. ‘Were you thinking these two gentlemen were happy now they were reunited with their Maker? That that was the end of the story?’

‘Well . . .’

‘Because I have heard from the coroner’s clerk, via Miss Featherstone,’ growled Rhys, ‘that there may be evidence of foul play.’

Now why didn’t she tell me THAT? fumed Miss Dimont.

FIVE (#ulink_0f397b94-91b9-5810-a5e5-9a9a276251da)

The weekend was not your own when you worked for the Riviera Express. Saturday mornings were devoted to writing up next week’s wedding reports (and deciding who’d feature in the ‘Thank Heavens!’ board), and turning out the more run-of-the-mill obituaries of the town’s great and good.

Quite often these careless and unthinking citizens would shuffle off the mortal coil without bothering to warn the Express beforehand, which could be irksome when it came to press day. Each new edition of the paper brought with it complaints from readers that their beloved one’s journey to the Other Side had gone unmarked.

Rudyard Rhys did not like complaints. He drummed into Judy and Betty and the other members of staff – Terry, even – how they must keep eyes open and ears firmly to the ground on this fundamental point. Miss Dimont had once asked him, mid-tirade, if her job now was to walk about the town centre stopping people and asking, ‘Know anyone about to die round your way?’ But though this raised a snort of laughter in morning conference, Rudyard simply ordered her to add the town’s undertakers to her lengthy list of morning calls.

Truth to tell, Miss Dimont was rather good at obituaries. Why, only the other month she had written a corker about William Pithers, one of the town’s roughest diamonds, who’d risen from obscurity during the War to become one of its most prominent citizens. His cerise Rolls-Royce, yellow tweed suits and the fat Havana sticking out of his breast pocket did not denote a man of breeding, perhaps, nor yet of great intellect, but Bill Pithers had made his mark all right. His fat-rendering business, though noisy, smelly, and hardly the town’s greatest visual attraction, had made him richer than most. Money allowed him a voice in the community far louder than if he’d been elected to the Town Council or the Bench.

Pithers threw his money around (‘noted for his extraordinary generosity’, typed Miss Dimont pertly) and lorded it down at the golf club (‘a sporting enthusiast’). After a lucrative week’s work rendering fat, he would sit in the bar dishing out drink and opinion in equal measure to a befoozled audience made up of the thirsty, the hard-up, the deaf and the occasional owner of a rhinoceros skin.

‘An enthusiastic conversationalist,’ tapped Miss Dimont, who had bumped into the ancient Pithers when the Ladies’ Inner Wheel invited her to their annual nine-hole tournament dinner, ‘he often encouraged others into lively debate.’ Indeed so; that night the lard-like entrepreneur had treated his audience to a twenty-minute peroration on how Herr Hitler was a much misunderstood man; it led, regrettably, to fisticuffs.

‘Indeed his love of life’ (barmaids) ‘and the Turf’ (he rarely paid his bookies) ‘set him aside in the community’ (he had no friends) ‘and will make him a much-missed figure’ (three people went to his funeral, all of them to make sure he was dead).

Weaving such barbed encomiums was Miss Dimont’s consolation, for through the office window she could see across the red rooftops to the promenade, the beach and the glorious turquoise sea, which this morning was like glass. Young lovers strolled hand-in-hand, children built their dreams in the sand, the Temple Silver Band parped joyfully in the Victorian bandstand.

Miss Dimont sighed and picked up another green wedding form.

‘It was love at first sight in the Palm Court of the Grand,’ she rattled. ‘Waiter Peter Potts and cleaner Avril Smedley met under a glittering chandelier and . . .’

This was an inspired introduction to the lives of two very nice but humdrum Temple Regents employed by the town’s grandest hotel. The rest of her report – the guipure lace, the bouquet of white roses, stephanotis and lily of the valley, the honeymoon spent at a secret location – was standard pie-filling, but Miss Dimont adorned the crust with a little more care because she happened to know Peter. She was often in the Grand on business, and he was always most attentive. She was happy that he had found love with Avril for he was rather a sad boy. She would insist that their picture was not added to the Thank Heavens! board, but in truth it was a prime contender.

Her reports had only to be one hundred and fifty words long – on an average Saturday morning she would get through three or four – but she found it difficult to concentrate. Part of her longed to be set free from her desk so she could enjoy the glorious weather this lazy Indian summer was so generously providing, but another part kept returning to the deaths of Gerald Hennessy and Arthur Shrimsley.

The coroner’s clerk had confirmed to Betty that one of the inquests might be troublesome because of certain suspicious circumstances, but refused to add a name or further clues. She would have to wait till Monday at 2 p.m., when proceedings would be opened and adjourned.

If it was suspicious it had to be Shrimsley, Miss Dimont decided, because of the note in his hand. But then again, as she thought about it, that of itself wouldn’t be suspicious if indeed he’d gone against character and done away with himself – a suicide is a suicide. Where was the ‘foul play’ which Rudyard Rhys had hissed at her last night?

It must therefore be Hennessy. She had definitely felt a frisson of fear when she saw that ‘M . . . U . . . R . . .’ traced in the carriage dust, but distance lends clarity and it was quite clear that with no sign of violence or personal distress Hennessy could have suffered no foul play – and though she was no expert, it did indeed look like a heart attack.

It left her nowhere.

Her morning’s work done, she covered up the Quiet-Riter and gathered up the delectable bunch of asters Mrs Reedy had left at the front desk as a thank you for her glowing report on the Mothers’ Union all-female production of Julius Caesar. It had taken a quite extraordinary suspension of disbelief to see this crinkle-permed bunch of ancients, clad in togas and brandishing knives, posing a serious threat to ancient Rome’s democracy, but Miss Dimont had pulled it off magnificently, and here was her reward.

Such was the exchange of kindnesses in Temple Regis. It made it such a wonderful place to live.