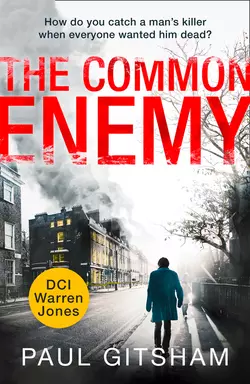

The Common Enemy

Paul Gitsham

‘Highly recommended. Crime Writing at its very best’ – Kate Rhodes on The Last Straw, book 1 in the DCI Warren Jones seriesHow do you catch a man’s killer when everyone wanted him dead?In Middlesbury, a rally is being held by the British Allegiance Party – a far-right group protesting against the opening of a new Mosque.When the crowd disperses, a body is found in an alleyway. Tommy Meegan, the loud-mouthed leader of the group, has been stabbed through the heart.Across town, a Muslim community centre catches fire in a clear act of arson, leaving a small child in a critical condition. And the tension which has been building in the town for years boils over.DCI Warren Jones knows he can’t afford to take sides – and must solve both cases before further acts of violent revenge take place. But, in a town at war with itself, and investigating the brutal killing of one of the country’s most-hated men, where does he begin?Don’t miss Paul Gitsham’s ingenious new DCI Warren Jones novel, The Common Enemy - pre-order now!Readers LOVE Paul Gitsham:‘Mr Gitsham is fast becoming one of my favourite authors’‘I love this series and hope Gitsham writes another book soon’‘Paul Gitsham never fails to produce a good story’‘I love the characters that Paul Gitsham has created’‘Will definitely read more from Paul Gitsham.’

About the Author (#ua15f5ee8-d4cd-56d1-9eff-784e71adba3d)

PAUL GITSHAM started his career as a biologist, working in such exotic locales as Manchester and Toronto. After stints as the world’s most over-qualified receptionist and a spell making sure that international terrorists and other ne’er do wells hadn’t opened a Junior Savings Account at a major UK bank (a job even less exciting than being a receptionist) he retrained as a Science teacher. He now spends his time passing on his bad habits and sloppy lab-skills to the next generation of enquiring minds.

Paul has always wanted to be a writer and his final report on leaving primary school predicted he’d be the next Roald Dahl! For the sake of balance it should be pointed out that it also said ‘he’ll never get anywhere in life if his handwriting doesn’t improve’. Over twenty-five years later and his handwriting is worse than ever but millions of children around the world love him.*

You can learn more about Paul’s writing at www.paulgitsham.com (http://www.paulgitsham.com) or www.facebook.com/dcijones (http://www.facebook.com/dcijones)

*This is a lie, just ask any of the pupils he has taught.

Also by Paul Gitsham, featuring DCI Warren Jones (#ua15f5ee8-d4cd-56d1-9eff-784e71adba3d)

The Last Straw

No Smoke Without Fire

Blood is Thicker than Water (A DCI Warren Jones novella)

Silent as the Grave

A Case Gone Cold (A DCI Warren Jones novella)

The Common Enemy

PAUL GITSHAM

HQ

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2018

Copyright © Paul Gitsham 2018

Paul Gitsham asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

E-book Edition © 2018 September ISBN: 9780008301170

Version: 2018-09-06

Table of Contents

Cover (#u867e6f03-eacf-5ac7-8db7-47d84645f24f)

About the Author (#u98f66646-60a1-597a-bd39-d78eb0158c78)

Also by Paul Gitsham, Featuring Dci Warren Jones (#u65ff4a97-4934-5669-9fb0-41af34d48854)

Title Page (#u1c914feb-df57-559f-b5c9-5f7b313d36de)

Copyright (#u9080b2f2-f789-55b9-893e-6f35878706b0)

Dedication (#u3c12aa36-b6f6-52cb-ac35-bcfc748afecf)

Saturday 19th July (#udfd9d79f-c1a0-5ec0-9afe-1f9632b61f89)

Prologue (#u2fbb83c0-2579-58ca-af2b-59f361e28de8)

Sunday 20th July (#u854986d1-400e-510e-a202-10c38e33f476)

Chapter 1 (#uc983f5cc-b80f-54e0-8dce-cb19dc8b82cb)

Chapter 2 (#ud951befe-7075-58db-baa5-6e9c1700c672)

Chapter 3 (#ueeaa1e08-e2f0-50ff-bfc2-f3005b5648de)

Chapter 4 (#u0c8536e8-ee41-5731-bf00-d71297881a66)

Chapter 5 (#uc364311f-f097-5586-8841-c7bbea6f2f56)

Chapter 6 (#u09be812d-96f0-5a63-94ce-7a8d168eeac2)

Chapter 7 (#u72770218-bb6d-5792-adda-3e5f081424d2)

Chapter 8 (#ud1241e85-c9ed-58d6-834b-20dcf010176a)

Chapter 9 (#u7af77cab-83d9-5c1c-93f7-938e4db25bf2)

Chapter 10 (#u184ed85b-87dc-5eaf-afeb-16bf7d87c4bb)

Chapter 11 (#ud47d8949-6d61-5a22-9bfa-fe4833af9271)

Chapter 12 (#u1aa845fa-9980-5bae-b3b3-51742ee7a3b9)

Monday 21st July (#ub0e37db5-f58d-50ff-9a9d-093d8118c81e)

Chapter 13 (#u19c248a6-fc44-596e-8229-4bf507b32377)

Chapter 14 (#u02a5667c-9399-509e-8437-38c290b46c47)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Tuesday 22nd July (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Wednesday 23rd July (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Thursday 24th July (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 36 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 37 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 38 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 39 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 40 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 41 (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday 25th July (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 42 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 43 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 44 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 45 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 46 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 47 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 48 (#litres_trial_promo)

Saturday 26th July (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 49 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 50 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 51 (#litres_trial_promo)

Sunday 27th July (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 52 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 53 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 54 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 55 (#litres_trial_promo)

Monday 28th July (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 56 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 57 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 58 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 59 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 60 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 61 (#litres_trial_promo)

Tuesday 29th July (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 62 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 63 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 64 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 65 (#litres_trial_promo)

Wednesday 30th July (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 66 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 67 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 68 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 69 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 70 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 71 (#litres_trial_promo)

Thursday 31st July (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 72 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 73 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 74 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 75 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 76 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 77 (#litres_trial_promo)

Friday 1st August (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 78 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 79 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 80 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 81 (#litres_trial_promo)

Saturday 2nd August (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 82 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 83 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 84 (#litres_trial_promo)

Monday 11th August (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 85 (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Read on (#litres_trial_promo)

Dear Reader (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

To Cheryl – with me every step of the way!

Saturday 19th July (#ulink_bd7c74e1-a479-56ff-92c7-b73eb03fd829)

Prologue (#ulink_fe25b104-ee42-568a-8cea-518531fd5efb)

Waste containers with sliding lids made the narrow alleyway even harder to navigate. Tommy Meegan bent over, hands on knees, breathing heavily. Behind him he could hear the sounds of fighting continuing. He smiled, baring his teeth, his blood singing from the adrenaline surging around his body.

It had gone better than he could have hoped for. He’d seen crews from the BBC, Sky News and ITN, all perfectly poised to capture the action when it finally kicked off.

Untucking his T-shirt, he bunched it up and used the front to wipe the sweat from his shaved head, leaving a red smear on the white of the St George’s flag. He reached up, wincing as his fingers found the cut above his temple. He hoped the TV cameras had caught that. He had no idea what it was that had actually struck him, just that it had come from the crowd of anti-fascists loosely corralled behind the cordon of under-prepared riot police.

Already he was planning the evening’s tweets and a press release for the website. A two-pronged strategy, he decided: they’d pin the attack on the Muslims and claim that the police hadn’t done enough to protect their right to free speech.

He touched his head again, another idea forming. The cut was still bleeding, but it was little more than a nick. He’d need to do something about that. If he was going to garner any sympathy on the evening news he’d need some real war wounds.

He squinted at his watch; he was actually a few minutes early. It had been touch and go with the timing after the police had kept them on the bus. He’d been worried that he’d get to the alleyway too late. Fortunately, the protestors had finally broken through the police line and the party members had scattered every which way.

He’d found himself running alongside Bellies Brandon and been concerned that he wouldn’t be able to find his way to his rendezvous unseen; his contact had made it very clear that he was to come alone. Fortunately, the fat bastard was so unfit Tommy had soon left him behind.

A whoop of sirens in the distance finally signalled the arrival of more riot police. Tommy smiled again. Assuming that all had gone to plan and everyone had done as they were told, all the party members should have left the scene long ago. The only fighting should be between the Muslim-lovers and the police. Even the left-wing, mainstream media couldn’t bury that.

The alleyway remained silent. He pulled the battered Nokia from his back pocket – no new messages. He’d made certain to empty the inbox; he didn’t want to make things too easy for the pigs if he got arrested.

The lack of any communications irritated him and worried him in equal measure. The promised reinforcements hadn’t transpired, meaning he’d had to scrap some of his speech. And what if his contact had changed their meeting point or the time of their rendezvous? He wished he had his smartphone with him so he could access his email or Facebook, but everyone knew that the little devices would betray you in a million different ways if they fell into the wrong hands. He’d have to trust that any changes to their plans would be sent the old-fashioned way, by text or phone call.

He wiped the back of his hand across his mouth, the adrenaline had made it dry. As excited as he was about the meeting, he hoped it wouldn’t drag on. The beers on the coach that morning seemed a long time ago and he’d worked up a thirst. The landlord of The Feathers was an old mate, sympathetic to the cause. He’d treat them right until the bus arrived to take them home.

The sound of a boot scraping the tarmac behind him caused him to spin quickly, bringing his hand up into a boxer’s stance. He squinted at the newcomer.

‘Why are you dressed like that?’ Tommy asked. ‘What’s that in your hand?’

Sunday 20th July (#ulink_bb8d4e9b-fd80-5586-afa5-71a4e37f1699)

Chapter 1 (#ulink_2dd91235-a3da-5304-9560-0e811913912b)

‘Tommy Meegan, leader of the British Allegiance Party, found stabbed in the alleyway between the Fry and Tuck chip shop and the Sparkles nail bar.’

DCI Warren Jones pointed to the mugshot glaring across the crowded briefing room. The face was that of a shaven-headed, middle-aged white man sporting a few days of dirty yellow stubble. The man’s file on the Police National Computer didn’t detail if the missing front tooth was a casualty of the same incident that that had left a three-inch scar on his cheek or the same fight that had re-shaped his nose. The headshot extended to shoulder level, showing the top of a Union flag tattoo poking out of his T-shirt.

The 8 a.m. briefing was even more crowded than usual, with many of the evening shift still in attendance. The update was the third that Warren had given in the past twelve hours. The snatched sleep between two and five had been supplemented by several cups of strong coffee, but his brain was starting to feel mushy.

He glanced at the front row, then wished he hadn’t. Ordinarily the only uniform visible in Middlesbury CID belonged to his immediate superior, Detective Superintendent John Grayson, and even he reserved his dress jacket and flat cap for formal events such as press conferences and visits by senior brass. Assistant Chief Constable Mohammed Naseem certainly qualified as senior brass, as did the two chief superintendents, tablet computers resting on their laps.

Warren took a sip of water and continued.

‘Mr Meegan spent thirty-nine years on this planet, with a total of eleven residing at Her Majesty’s pleasure for football hooliganism and racially aggravated assault. For the past three years he has been chief spokesperson for the British Allegiance Party. I’ll not go into too much background detail about that for the moment, I’ll leave that to Inspector Theodore Garfield of the Hate Crime Intelligence Unit.’

Warren switched slides, immediately noticing a small typo on the second line of the timeline. He cringed inside, hoping nobody else saw it – or if they did, that they were generous enough to see it in the context of almost twenty-four hours on shift.

‘These are the facts as we know them.

‘At midday yesterday morning a coach containing forty-three supporters of the British Allegiance Party, including Meegan, his younger brother, Jimmy, and other senior members, arrived in Middlesbury after setting out from Romford, Essex. As you are no doubt aware, they were due to hold a protest and march against the proposed Middlesbury Mosque and Community Centre, referred to by some as a “super mosque”.’

Warren switched briefly to a photograph of twenty or so men posing in front of a single-decker coach, like a touring pub football team. All were white, most with shaven heads, and they sported a remarkable collection of tattoos between them. All wore England football shirts or T-shirts with the stylised version of the Union flag that had been filling the rolling news channels for the past few hours. If nothing else, the British Allegiance Party had brand recognition now.

‘They tweeted this along with the hashtag #NoSuperMosque on several of their social media accounts.’ Warren used the laser pointer to circle a face in the centre. ‘There’s Tommy holding the banner with Jimmy, his brother next to him. These are the less camera-shy members; there are a similar number out of shot.’

He flicked back to the timeline. ‘They were met on arrival by riot control police and led to the agreed rally point. As I am sure you already know, their plans to march down Sparrow Hawk Road, where the current Middlesbury Islamic Centre is located, were blocked by the city council, so they agreed to a symbolic march to the council offices before holding a rally then dispersing. As I’m sure you also already know, the Islamic Centre caught fire yesterday afternoon at the same time that the BAP were holding their rally. I don’t believe in coincidences and so DI Sutton will be running a separate but linked investigation that he’ll brief you on after this one is concluded.’

Warren took another sip of water.

‘The demonstration was supposed to start at midday but was delayed after there were problems clearing the route of protestors.’ Warren moved on quickly. The blame game for what happened later had already started and he wanted nothing to do with it. As far as he was concerned Tommy Meegan’s murder, and the fire, were where the responsibility of CID started and ended.

‘Eventually they made it to the front of the council building where they set up their stall.’ Another photograph, this time the image was time-stamped and had the constabulary’s logo in the corner. ‘As you can see, a number of those present, including Tommy Meegan and his brother, addressed their supporters with loudhailers.’ Another photograph, taken at a wider angle, showed the gathering encircled by a ring of fluorescent-jacketed officers, arms linked against a much larger crowd of protestors.

‘As you know, there was a vigorous counter-protest held by a wide range of anti-fascist and anti-racism groups.’ Vigorous was an understatement. ‘Unfortunately, protestors managed to breach the police line and confronted the BAP supporters directly.’ The next photograph was taken from a helmet-mounted camera.

‘This is the last photo we currently have of Tommy Meegan before he disappeared and his body was found.’

The image was blurry, but showed the man brawling with a masked protestor. His face was split by a huge toothy grin and despite the cut on his forehead, it was obvious that the former football hooligan was loving every second of the confrontation. The time stamp read 14:36:11.

‘As you can imagine, the scene was pretty chaotic and it was some hours before order was restored. Eight BAP supporters and seventeen protestors were arrested at the scene, with the rest disappearing into the surrounding streets.

‘It looks as though there was some contingency planning on the part of the BAP as they eventually regrouped at The Feathers pub.’ The bar was a dive frequented by the sort of clientele that would welcome members of the BAP with open arms.

‘When did they realise Tommy Meegan was missing?’

As usual it was Detective Sergeant David Hutchinson who asked the first question.

‘Apparently his brother tried to ring him at about 4 p.m., but the phone went straight to voicemail. He wasn’t worried at first, he figured he was either in custody or taking cover somewhere. He and a couple of others rang him again between four and five and eventually assumed that he had been arrested. They already knew that at least some of their friends were in the back of a police van.’

‘So nobody raised the alarm?’

‘No, although I don’t think that’s too surprising. I doubt their first instinct would be to call the police. Besides which, they were enjoying the hospitality of The Feathers. They weren’t planning on going anywhere for a few hours.’

‘When was the body found?’

‘The switchboard received a call at 6.31 from the owner of the chip shop to the left of the alleyway. They’d closed for a few hours when the trouble kicked off and were putting the bins out prior to reopening when they found him.’

Warren changed slide to one showing a wide angle shot of a narrow gap between a fish and chip shop and a nail and hair bar. Large waste bins took up three quarters of the width, leaving barely enough room for a large man to squeeze past. Blue and white crime scene tape demarked the entrance. A large pool of dark red blood was clearly visible.

‘So we have a gap of almost four hours between the last known photograph of him and his body being discovered. Do we have a time of death yet?’ This time it was Detective Constable Gary Hastings who asked the question. The young officer was currently applying for promotion to sergeant and was no doubt desperate to ask a question in the presence of senior officers. Unfortunately, he was standing at the back and nobody bothered to turn around to see who had spoken.

‘I’m afraid the weather was so warm that his core temperature had yet to fall by a significant amount, DC Hastings. The pathologist may be a bit more helpful after the post-mortem is completed, but I doubt we’ll narrow the window of opportunity very much.’

Even if ACC Naseem didn’t know Hastings’ face, Warren could at least name-drop the young officer.

‘What about cause of death?’ asked DC Karen Hardwick.

‘Preliminary finding is stabbing; you can see how much blood was lost. He has some other superficial cuts and bruises that may have arisen during the riot. Again, the PM will tell us more.’

‘What about CCTV?’ DSI Grayson was the questioner now.

‘We’ve pulled the footage from all of the cameras on the high street and all the businesses in the vicinity, but, as you can see, there are significant blind spots.’

A simple, top-down line drawing of the alleyway and the surrounding street replaced the photograph. The locations of fixed cameras were marked, along with arcs showing their fields of view.

‘Unfortunately, there was only one camera covering the opening of the alleyway and none at the rear. Irritatingly that camera was broken a couple of days ago and hadn’t been repaired.’

ACC Naseem shifted slightly in his chair. ‘Premeditation?’

‘A good question, sir. It was taken out by a brick on Thursday night. Since there were no break-ins or crimes reported in the area, it was logged as petty vandalism and no one attended.’

‘I hope that oversight has been addressed, DCI Jones.’

Warren let the implied rebuke slide; pointing out that the unit’s strategic priorities placed low-level criminal damage well down the list would have been unwise, given that several of the people responsible for deciding those priorities were seated in the room.

‘Yes, sir. We’re looking at other cameras in the vicinity from that time period to see if we can identify the culprit.’

‘What is the status of the crime scene?’

‘The crime scene investigators are still there, doing a fingertip search for the murder weapon. We’ve blocked off most of the town centre because we aren’t sure what route Mr Meegan took to the alleyway. Sunday trading laws mean we have the area to ourselves for another couple of hours, but I’ll need authorisation to keep the area closed much longer.’

Naseem nodded to Grayson.

Warren clicked to the blank slide that signalled the end of the presentation.

‘It’s going to be a big investigation, people. We have a team from HQ down in Welwyn Garden City joining us later to boost our numbers. In addition, the fire that broke out at the Islamic Centre at about the same time has been confirmed as suspicious. It looks as if it might also be upgraded to homicide if two victims sheltering in the centre when it caught fire don’t pull through.’

‘How likely do you think it is that the fire was linked with Tommy Meegan’s murder?’ asked the Superintendent sitting to the left of ACC Naseem. ‘Could it have been tit-for-tat?’

‘Based on the timings, it looks as though a direct retaliation either way is unlikely, ma’am. However I believe that some sort of link is likely.’

‘Thank you, DCI Jones.’ Naseem stood up and turned to address the assembled officers.

‘As you all know, it takes a lot to get me out of my office.’ A few polite chuckles passed around the room. ‘Unfortunately, this is going to be a big deal. I think we can all agree that the death of Tommy Meegan is no great loss to humanity, but his murder is going to cause us significant problems going forwards. Middlesbury’s a small town, with pretty good community relations for the most part, but this could cause all manner of trouble. You don’t need me to tell you that what is likely to happen if it transpires that the fire at the Islamic Centre and the protest march are linked. You also don’t need me to tell you that yesterday’s counter-protest policing didn’t go to plan. Clearly, not enough resources were deployed. The decision was then made to reassign other resources, leaving the Islamic Centre vulnerable.

‘The press are all over us. We’ll be announcing a review in due course but in the meantime I want to make it absolutely clear that all communication with the media goes through the press office.’ He fixed the room with a glare. ‘Anybody caught going off-message with members of the fourth estate will be in my office explaining themselves. That includes social media. Keep your mouths shut and stick to posting pictures of kittens on Facebook.’

A mutter of assent rippled around the room. Warren hoped the rebuke would have effect, these days one ill-thought tweet could go viral and end a career.

With that, Naseem retook his seat and the next speaker stood up.

‘Morning, everybody, I’m Theo Garfield from Hertfordshire Constabulary’s Hate Crime Intelligence Unit. I liaise with the National Crime Agency and other groups such as the Football Intelligence Unit and the Social Media Intelligence Unit. I’m here to make sure that you have all the information you need about the late Mr Meegan and his band of merry men and to place some of yesterday afternoon’s events into context for you.’

Theo Garfield was a whip-thin man with a shaved head and dark olive complexion. His accent remained resolutely Merseyside, although it was clear that he had been living in the south for some years. He too was armed with a PowerPoint presentation, although his was a lot slicker than Warren’s.

‘As you are aware, Mr Meegan was the spokesperson for the British Allegiance Party, or BAP as it is commonly known; apparently all the good names were taken.’ Garfield smiled briefly. ‘They tried a couple of other three letter acronyms, but were threatened with legal action if they didn’t stop using them. Not that their current name is without its problems Allegiance is a difficult word to spell and so Unite Against Fascism have bought the web domain names with the most common misspellings and redirect lost visitors to their own site.’

Laughter rippled around the room.

‘BAP are a motley bunch. As always with these organisations, the hardcore wouldn’t fill more than a minibus, but they can muster a coachload for special occasions, and their numbers appear to be increasing. Pretty much everyone who turned up yesterday was already in our files. Almost everyone on that bus has at least one conviction for violent assault.’

The slide changed to a photograph of Tommy Meegan and his brother in a pub, arm-in-arm, wearing England football shirts and holding half-empty pint glasses aloft.

‘This was taken a few years ago, probably during the 2012 European Championships – we know it’s not this year’s World Cup because they are celebrating a win.’ This prompted more laughter. ‘The driving force behind the party are the two brothers, Tommy and younger brother Jimmy. Local boys, they went to school in Middlesbury before they moved down to Essex. This weekend was supposed to be a bit of a homecoming for them.

‘Tommy has multiple arrests for racially aggravated assault, but he’s an absolute charmer compared to Jimmy who has spent more time since his eighteenth birthday inside than out. Like father, like son. Football hooliganism, racially aggravated assault, beating up homosexuals… you name it, he’s been done for it and there’s almost certainly a whole lot more besides.’

The slide switched to a photograph of an older man. Even without the bent features of his two sons, the family resemblance was immediately clear. ‘Meet the late, unlamented Ray Meegan. A veteran of the Seventies’ and Eighties’ hooligan scene he also did time for armed robbery. In fact, he was wanted in connection with an attack on a post office when he dropped dead of a heart attack seven years ago.’

He smiled. ‘The family tried to talk down the far-right connections and play the victim when the local paper interviewed them after anti-fascist protestors gatecrashed the funeral, but a half-page photograph of the coffin in the background draped in swastika-shaped wreaths kind of scuppered that.’

Garfield was an engaging speaker and the team were enjoying the break from the typical dry presentations, however Warren got the impression that if he let him, the man would chatter on all day.

‘You said that we know who the hardcore of the party are?’

‘Yeah. The party has only existed in its current form for about five years and most of its founding members came from other organisations that we were tracking. Ideologically it is not a political party and is unashamedly racist. The far-right scene has been undergoing serious ructions in the past decade or so with many of the slightly more moderate believers joining quasi-political parties such as the BNP, the EDL or, more recently, UKIP.

‘BAP on the other hand claims to have no belief or faith in the democratic process and draws support from the real nasty end of the political spectrum, including former members of Combat 18 and the National Front. They are openly affiliated to some of the European neo-Nazi parties, such as the Austrian Freedom Party and populist anti-Islamist movements, such as Pegida.

‘Yesterday’s march was their biggest event to date. Apart from a few so-called “direct action” events, most of their presence is internet-based.’

Garfield switched slides. ‘They may be uneducated thugs for the most part, but somebody in the party has clearly been on a few social media training courses. Their website is pretty slick, but their main strength lies in their use of Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and the like.

‘The big social media firms remove some of their more racially charged and offensive posts, but for the most part they stick within the rules. Perhaps more insidious are their subtler campaigns. This is typical…’ He clicked to another slide, a picture of a homeless person and a banner urging viewers to ‘share if you think it’s a disgrace that former soldiers starve whilst immigrants get free housing’. Warren recognised the image from his own Facebook feed. He’d deleted it without sharing.

‘They have several dozen known accounts, some with openly provocative names such as “Keep Britain British” and others with more innocuous titles such as “Proud to be British”, sharing harmless patriotic fare. The First World War commemorations have been a real party for them, with lots of pictures of poppies and young Tommies. We’re expecting a major offensive in the run-up to Remembrance Sunday with attempts to hijack the poppy appeal.’

‘Why? Surely most of the people sharing these posts have no idea who’s behind them and would be appalled if they knew?’ The tone of the questioner, sat somewhere towards the back, suggested that they may be reconsidering some of the pages that they had personally liked or shared.

Garfield gave a shrug, ‘Nobody’s really sure. Some of it’s plainly propaganda and the number of shares – which is in the tens of thousands for some of these posts – probably helps them claim to be on the side of the “silent majority”. We think it might also be a form of market research, using the number of likes, shares and retweets as a means of gauging popularity for different causes. They might also get a bit of click-through revenue from people visiting their websites. As to its effectiveness in terms of active members, it’s hard to tell. They operate a lot of sock puppets – fake accounts – so it appears as if they have more supporters than they actually do.’

Warren cleared his throat slightly, he didn’t want to end up spending all morning discussing the far-right’s social media strategy.

Taking his cue, Garfield switched to the next slide.

‘On the opposite side of the argument to the BAP, we have the counter-protestors. It’s early days, but part of my team is also trying to identify as many of them as possible. Somebody killed Tommy Meegan and it’s as good a place to start as any. There were a lot more there than we expected, so we’ll have our work cut out for us.’

That was something of an understatement. From what Warren had gleaned so far, the number of BAP supporters was as predicted, but the counter-protest was significantly larger than anticipated. It had been sheer weight of numbers that had caused the lines to collapse and it was little more than good luck that more people hadn’t been injured or even killed.

‘We’re compiling a list and scrutinising CCTV for known faces, but we know that a lot of attendees were either concerned locals, or not known to us. We have a couple of super-recognisers helping us, but the seasoned veterans were wearing masks or had their faces and tattoos covered. Aside from the usual agitators there were also protestors from more mainstream leftist groups, people showing solidarity with the local Muslim community, and lots of students, none of whom are likely to be in our files.’

‘Any indicators from social media about who may have wanted to kill Meegan?’ asked Warren.

‘It’s hard to tell. BAP members, particularly the Meegans, get so many death threats posted on their blogs, Facebook pages and Twitter feeds they hardly bother to block them anymore. Where possible, we’re identifying and cross-referencing accounts with the list of attendees, but it’s slow going.’

Warren thanked him, feeling slightly dejected. The power of the internet had transformed policing in recent years, with many officers like Mags Richardson in his own unit becoming experts in its use. However, that power was also its downfall. The chances were good that buried amongst the vast amounts of data being collected were hints to the identity of Tommy Meegan’s killer. But finding those clues could take months or even years of sifting. Quite aside from the huge budget implications, Warren didn’t have months or years. The local and national media were already reporting a spike in inflammatory social media posts, from the far-right, the Muslim community and anti-racism campaigners. Even if Warren and his team had yet to find a direct link between the fire and the protest march and its aftermath, the public at large were already conflating the two events. Unless something was done soon Middlesbury was facing a bloodbath.

Chapter 2 (#ulink_af68f9f5-3699-5836-9cdd-b8b01bb0561e)

After the briefing, Warren was summoned to DSI Grayson’s office. The privacy blinds were drawn on the door, so he had no idea who or what was awaiting him when he entered.

‘Sirs,’ Warren greeted the seated officers. There were no spare chairs, so Warren found himself standing like a naughty schoolboy.

‘Coffee?’

That was a good sign, the Assistant Chief Constable didn’t offer you some of John Grayson’s finest roast if you were in trouble.

‘That’d be lovely, sir.’

As one of the ACC’s assistants poured Warren a cup, he got down to business.

‘Let’s be blunt, Warren. Yesterday was a colossal cock-up on several levels, not least the murder of Tommy Meegan. We massively underestimated the number of counter-protestors and had to pull in reinforcements from across the region. The riot was bad enough, but a politically charged murder and an arson attack on a vulnerable target that we should have been protecting… we dropped the ball big-time.’

Warren stole a glance at DSI Grayson, who looked grim. The problem had landed squarely in his lap – which by extension meant Warren’s. The subtext was clear. Hertfordshire Constabulary was already looking foolish; now it was time to clean up the mess, and do it quickly. The grapevine was already buzzing with speculation that the officer in charge was likely to fall on her sword. Would the same be expected of Grayson – even Warren – if he failed to deliver?

‘Monitoring from the Social Media Intelligence Unit indicated tensions were already running high before the march, and now the far-right have gone ballistic,’ continued Naseem. ‘They’re already deciding how to capitalise on yesterday’s events. These buggers couldn’t decide on the colour of the sky normally, they hate each other almost as much as they hate non-whites and homosexuals, but yesterday’s killing is uniting them. The same goes for a lot of the anti-fascist organisations; we’re already seeing calls for mass protests if we don’t start making arrests over the Islamic Centre fire soon. More than a few keyboard warriors have said that what happened to Tommy Meegan was long overdue and have started naming other far-right activists as potential targets.’

The room settled into a leaden silence; eventually Garfield spoke up.

‘This time of year is full of significant dates for the far-right. They were originally planning on marching on the seventh of July, the anniversary of the London bombings. I guess they figured they could try and make a link between the proposed new mosque and Islamic extremism. We blocked that as too provocative. Then they tried to march on the first of August. Obviously we’re wise to that and said no.’

Warren evidently didn’t hide his ignorance fully.

‘The first of August, written 1/8 represents the initials of Adolph Hitler. It’s where Combat 18 get their name from.’

‘I see.’

‘So they suggested the next day. We almost let them have it, until we ran it through the computer – the eightieth anniversary of Hitler’s rise to Fuhrer. Finally, we settled on Saturday the nineteenth of July as comparatively harmless.’

‘OK.’

Warren didn’t quite see what they were so concerned about, surely the issue had been fixed?

‘The problem is that whilst we could stop a march through town on the grounds that it was likely to cause a breach of the peace, they’re already calling for his funeral to be held on August the first.’

‘Shit.’

‘Exactly. It’ll be a magnet for every right-winger in Europe. He’s already being eulogised as some sort of bloody martyr.’

‘Can we block the funeral?’

ACC Naseem snorted. ‘That’d be political dynamite. Can you imagine the reaction – “Police block grieving family’s funeral”? No, that’s a decision well above the pay grade of anyone in this room.’

‘Home Secretary?’ asked Grayson

‘You’d think, but we’re less than a year away from a general election, I wouldn’t bet on a speedy decision. Nevertheless, Mrs May has let it be known that she is following events closely.’

Warren’s head spun. He’d known the repercussions of the previous day’s murder were likely to be significant but he’d had no idea what was at stake. And he really wasn’t happy about the Home Secretary taking an interest. That sort of interest could end an officer’s career pretty quickly.

‘So where does that leave us?’

‘We need to know who was responsible for the murder as soon as possible to manage the fallout. If it was one of the protestors, it’ll be bad enough. If it turns out it was a member of the local Muslim community seizing an opportunity, the consequences don’t bear thinking about.’ He paused. ‘Without wanting to pre-empt DI Sutton’s briefing, are we treating the fire as arson?’

‘From witness reports, it’s looking that way.’

‘Great, that’s all we need.’

Naseem removed his glasses and rubbed the bridge of his nose. Warren watched him carefully over the top of his coffee cup.

At first glance it seemed strange that a small, first-response unit like Middlesbury would be taking the lead in such a politically sensitive operation, but it didn’t surprise him. Ostensibly, Middlesbury was most suited to coordinate investigations on its own turf; the CID unit’s intimate local knowledge made it ideal for dealing with crimes taking place at this end of the county, miles away from the Major Crime Unit’s headquarters in Welwyn Garden City. But there was more to it. Yet more cutbacks to the policing budget were making Middlesbury CID’s special status harder and harder to justify. A successful resolution to such a big, high-profile case would do wonders for the unit’s long-term future. The question was, were they being given an opportunity to prove themselves or handed enough rope to hang themselves?

Naseem’s face was unreadable. Beside him, Grayson looked similarly impassive, but his knuckles were slightly white as they gripped his coffee mug. Naseem turned to Grayson. ‘Blank cheque, John.’ His mouth twisted in disgust. ‘This needs sorting in the next ten days or we’re looking at the Brixton riots all over again.’

So there it was: make or break time for Middlesbury CID – and the career of John Grayson. Solve the murder quickly and efficiently and Grayson was one step closer to his next promotion; mess it up and it was the end of Middlesbury CID’s independence and perhaps John Grayson. And, quite possibly, Warren Jones.

Chapter 3 (#ulink_d63f9e05-ef98-5cd6-8a06-a662bc9dda4a)

DI Tony Sutton dropped wearily into the comfy chair opposite Warren’s desk.

‘The fire at the Islamic Centre is almost certainly arson; I’ll be meeting the fire investigators later today.’

‘Is there a final casualty count?’

‘There were about thirty in the centre at the time, almost all women and children or older folk. They managed to get upstairs, where the fire service rescued them. A total of eight were treated for smoke inhalation, with two remaining in hospital. An eighty-nine-year-old woman already in poor health is in intensive care alongside a three-year-old boy.

‘Fortunately, lunchtime prayers had finished a couple of hours before and it wasn’t a Friday. Karen and I will be visiting the imam in charge later, but he’s already said that ironically they were in there because of the trouble brewing in town. The centre has invested heavily in security in recent years.’

‘Speaking of security, do we have any CCTV?’

Sutton smiled humourlessly. ‘It’s funny you should ask that. The CCTV at the front of the building wasn’t working.’

Warren sat up slightly straighter. ‘Really? Can I guess what happened?’

‘Be my guest.’

‘It was broken by a brick on Thursday evening.’

‘Half right, Wednesday evening.’

* * *

Tommy Meegan’s body had been found almost eighteen hours ago, but this was Warren’s first opportunity to visit the crime scene. Even in a small, specialist CID unit like Middlesbury, with its unique role as a first responder to local crimes, most of the legwork was performed by those with the rank of Inspector or below. Warren’s immediate superior, DSI Grayson, seemed to only leave his office to play golf or schmooze with the senior ranks at the force’s headquarters in Welwyn Garden City.

At Warren’s last appraisal, it had been suggested that he needed to practise delegating more. His wife, Susan, had certainly been pleased; Warren’s first few cases at Middlesbury had placed him – and his loved ones – directly in the firing line and she had questioned on more than one occasion why he needed to be so hands-on.

The problem was that Warren missed the excitement that came with solving a case. When he’d moved to Middlesbury three years previously, it had been to further his career. There were precious few DCI opportunities on the horizon in the West Midlands Police and the sudden vacancy at Middlesbury had seemed too good to be true. He’d applied and then accepted the post immediately.

The unit’s unusual position would provide Warren with a perfect mix of both smaller, community-style policing and management, with the safety net of a senior officer directly above him. A couple of years in that sort of environment and he would be ready to move on.

It hadn’t quite worked that way. Even assuming he hadn’t permanently blotted his copybook after the Delmarno case two years ago, he’d realised that he liked Middlesbury. His predecessor, Gavin Sheehy, had once described leading the unit as the best job he’d ever had. Warren had disagreed with Sheehy over much – but he was being won over on that score.

It had been made clear that solving the death of Tommy Meegan was to be Warren’s number one priority and he had interpreted that to mean ‘leave the office and get your hands dirty’.

But not literally. The body might have been removed, but the alleyway was still an active crime scene and Warren wasn’t getting a close look without appropriate precautions. The CSIs were still looking for trace evidence and so gloves and booties weren’t enough, particularly when TV camera crews with zoom lenses were in attendance. The last thing they needed was for some defence solicitor to claim evidence gathering procedures weren’t properly followed and use TV footage to demand that key exhibits be declared inadmissible.

The plastic-coated paper suits were far from ideal attire on a hot July day. The face mask trapped the heat from his breath and within moments he was licking sweat off his top lip. Suddenly his air-conditioned office seemed a lot more attractive…

Stepping out from the police van that he’d changed in, Warren glanced towards the gathered news crews. Thankfully, nobody seemed to have registered his presence. Warren was hardly a celebrity but a few of the local hacks would recognise him and he had no particular desire to have his face splashed all over the Middlesbury Reporter’s online edition, with the attendant excuse to rehash old stories from years ago. Perhaps the face mask had its uses after all.

‘DCI Jones, what brings you out here on such a fine day?’

As always, the jollity of Crime Scene Manager Andy Harrison conflicted with the sombre nature of his job. But given what he saw on a daily basis, Warren figured it was probably a survival mechanism. Naturally, the burly Yorkshireman didn’t offer to shake his hand.

‘I’m here to make sure you aren’t cutting any corners, Andy.’

To Warren’s surprise, the man’s eyes – the only part of him visible above his mask – narrowed slightly.

‘It’s not us who’s cutting corners, sir.’

Warren paused before realising what the man was referring to.

‘DetectIt Forensic Services?’

‘I caught one of them using a box of out-of-date saline swabs to take blood samples from the patch next to the body.’

‘How can a saline swab be out-of-date?’

‘That’s exactly what he said. And of course he’s right, but any defence counsel worth his salt would move to have that evidence ruled inadmissible.’

Warren shuddered. ‘What happened?’

‘Fortunately, the victim bled like a stuck pig so there was plenty of blood to go around and the lad hadn’t started taking samples from some of the tiny specks we found further up the alleyway. I got him to fetch a fresh box and retake the swab.’

‘Shit.’ Warren lowered his voice. ‘Is this going to be a problem, Andy?’

The veteran CSI sighed. ‘At the scene I can keep an eye on the newbies and we’re whipping them into shape, but God only knows what happens when the samples go off to the lab. The Forensic Science Service might not have been perfect, but at least we knew who was doing the testing. Some of these new private companies didn’t even exist eighteen months ago. Their only qualification seems to be that they’re cheap.’

Warren felt a tightening in his gut. The thought that such a high-stakes case could be scuppered by a cut-rate CSI with a box of out-of-date swabs wasn’t worth contemplating.

‘Thanks for the heads up, Andy. In the meantime, talk me through what you’ve got.’

‘The victim was probably standing close to those bins when he was stabbed. There’s some spatter consistent with arterial spurt and from the blade when it was pulled out.’ He picked up a tablet computer with a removable plastic coating and started scrolling through images on its screen.

‘See this picture of that bin over there? The angle of the droplets suggests they were probably flicked off the tip of the blade when it was withdrawn. The droplets then continue in that direction—’ he pointed down the alleyway in the opposite direction to the shop front, where a series of numbered markers had been placed on the tarmac ‘—with a pattern consistent with dripping—’ he turned a half-circle on the spot, gesturing back towards the main road ‘—and our victim appears to have crawled in that direction, presumably away from his attacker. He didn’t get far; that big patch of blood behind that bin is where we found the body.’

The blood smears were no more than three metres in length and thick. Warren pictured the victim dragging himself away from the person who’d just stabbed him. Another few metres and he’d have been visible to passers-by in the high street. Could he have survived if somebody had found him and called for help? Without realising, he’d asked the question out loud.

‘That’s the sort of question that can only be answered by a pathologist, sir. But if I had to speculate… it’s doubtful. I think it’s a miracle he got as far as he did.’

Warren felt a brief flash of sympathy. Tommy Meegan had been a deeply unpleasant individual, but in those last few moments he was nothing more than a human being facing death – and probably terrified. Did he feel any remorse for the life he’d led? Warren shook off the feeling and turned to point back at the waste container with the blood spatter.

‘Is that where you think the murder weapon is?’

Harrison nodded. ‘We’ve finished sweeping the area around it for trace and we’re about to get in and start looking for it. Unfortunately, somebody from the nail bar dumped a load of rubbish in there shortly before the owners of the chippy discovered the victim behind their own bin. If the weapon was dumped in there it will be buried under half a ton of hair clippings and fake nails.’

Warren sighed.

‘Great, that screws the hair and fibre analysis.’

Visiting the scene probably hadn’t told him anything that he didn’t already know, and the high-resolution photographs that Harrison promised to send him would tell him far more than his eyes ever could, but it gave him a sense of what had taken place.

‘What about clothing?’

‘It was an arterial cut and he would have been pumping blood under high pressure, so I doubt the killer got away without at least some transfer. We’ll be looking for any discarded clothing. Failing that, find me a suspect and give me access to his laundry bin and shoe collection. We’ll find something.’

Chapter 4 (#ulink_df77f71a-c4b9-5b98-8a32-23ec9ef18524)

Imam Danyal Mehmud’s eyes were bloodshot and the shaking of his hands attested to the adrenaline he was running on. Karen Hardwick and Tony Sutton were seated in the imam’s living room, two streets over from the remains of the community centre. The air in the street still smelled of smoke. The house was a two-bedroom affair with a modest front room whose walls were covered in a mixture of family pictures and framed scripture.

‘Is that the Frozen fan?’ Sutton nodded towards a picture of a smiling infant in a light summer dress. She hadn’t been smiling ten minutes ago when her father had switched the cartoon off and sent her upstairs so they could speak in peace.

‘Yes, that’s Fatima. If I hear “Let it Go” one more time… she’s obsessed.’

‘My niece is about the same age,’ said Hardwick. ‘At least choosing a birthday present was easy this year.’ She paused. ‘Is the little boy in the picture with her the other victim, Abbas?’ Both children were dark-haired, with light brown skin and faces smeared with ice cream.

‘Yes, they’re cousins. My sister’s little boy. They’re almost exactly the same age.’

‘So that means Mrs Fahmida must be your grandmother?’

Mehmud nodded sadly.

‘I’m very sorry, I had no idea.’

The man in front of them was in his late thirties, wearing a white dishdasha over his jeans and trainers. By all accounts he’d been awake for pretty much the entire past twenty-four hours, comforting his congregation and, Sutton now realised, dealing with his own shock and grief. He was clearly running on adrenaline and little else, given that he was still fasting during daylight hours to mark the Muslim holy month of Ramadan.

‘Have you heard anything more from the hospital?’ asked Hardwick.

Mehmud shrugged helplessly. ‘Nani is in intensive care. They aren’t very hopeful. Abbas is poorly but stable. We are praying for his recovery, inshallah.’

Mehmud stood up suddenly as if filled with an energy he didn’t know what to do with.

‘I haven’t told Fatima anything yet. I’ll wait to see what happens in the next twenty-four hours or so. If he… well, she’ll be devastated. My sister and I are very close and Fatima and Abbas are like brother and sister.’

‘I realise that it’s been a trying time but could you take me through what happened that day,’ asked Sutton after a respectful pause.

‘We knew all about the BAP march of course, but I’d tried to persuade people to keep their heads down and not get involved.’ Mehmud shrugged. ‘Not everyone listened. We found out that the BAP were due to arrive about midday. It was easy enough to find their plans on the internet. We’d spoken about it the day before at Friday prayers. We had a higher than usual attendance; there were some brothers and sisters that I didn’t recognise.’

‘People from outside Middlesbury?’ asked Hardwick.

‘I think so. Not many, but I got the feeling that they weren’t there by chance.’

‘You think they’d arrived specifically to join the counter-protest?’

‘Yes. I tried to counsel against it – the last thing we as a community need is to be involved in violence, especially with the planning hearing for the mosque and community centre coming soon.’

‘So what happened on Saturday?’

‘There was an informal gathering here after dawn prayers. Some of the more fiery members of the congregation wanted to take part in the protest marches. A few went off to join in, but most stuck around until midday prayers.’

‘What happened then?’

‘A few more went to the protest and about half went back to lock up their shops and businesses. In the end there were about thirty, mostly women and children, who chose to stay here. I decided to lead by example and stick around.’

‘Why did they stay?’ asked Hardwick.

‘They were scared. There were all sorts of rumours on the internet about Muslims being targeted on the street or having their houses vandalised. All nonsense, of course, but I decided that anybody who wanted to remain was welcome.’

He closed his eyes briefly. ‘They should have been safe here. We locked the doors and there was a police car outside.’ His voice cracked and his bottom lip started to tremble. ‘But they weren’t, were they? We were trapped like rats.’

‘Tell us what happened inside the centre.’

‘It was pretty tense. As the protests got more violent the BBC started to cover it and there was loads of activity on Twitter. We moved the older children upstairs with some toys and the rest of us stayed downstairs to watch the telly.’ His voice hardened, and for the first time an edge of anger crept into his tone. ‘We still thought we were safe. There was a police car up the street, and all of the action was happening in the town centre. Nobody told us the police car had…’ He stopped, unable to continue the sentence.

‘We haven’t been able to get inside the centre yet,’ said Sutton, ‘so you’ll have to help us with the layout. Where were you watching TV?’

‘In the kitchen area, out the back. As you enter through the front door there are shelves for footwear and some sinks for ablutions, straight on is the kitchen, to the left the musallah, the prayer hall.’

‘And where are the stairs?’

‘To the right of the entrance.’

‘And what do you have upstairs?’

‘There are several rooms. The largest is a function room, then there is a storeroom, some bathrooms and another couple of rooms that we use for wedding guests to get changed etc.’

‘Did you know everybody?’ asked Hardwick.

‘Yes, the visitors had all gone off to the march.’

‘Did you see anybody strange hanging around outside?’

‘There were a few brothers outside, but they left eventually.’

‘What do you mean by brothers?’ questioned Sutton.

‘Other Muslims.’

‘How did you know they were Muslims if you didn’t know them?’

Mehmud blinked. ‘Well, they were dressed in thawb with full beards and well, you know, they were Asian.’

Sutton decided to move on.

‘When did you realise the building was on fire?’

‘About two-thirty we heard breaking glass out the front. I told everyone to head into the musallah, since it doesn’t have any windows. However, as we went into the hallway, we saw that the area in front of the door was on fire. I told the women to go through the kitchen and leave through the back door, whilst me and the men ran to get the children.’

The man’s eyes took on a faraway cast.

‘The mats in front of the stairs were starting to catch, so I sent the rest of the men upstairs whilst I tried to put the blaze out with a fire extinguisher. And then my wife came back through to tell me that the back door wouldn’t open.’

He closed his eyes briefly and his voice dropped to a whisper.

‘I didn’t know what to do. We couldn’t stay downstairs and I couldn’t put the fire out. So I sent them all upstairs to join the others. We’d called the fire brigade and I figured they’d be able to rescue us from the top floor more easily.’ His voice broke slightly. ‘The smell was horrible. Some of the shoes had caught fire and there was thick black smoke everywhere. Nani couldn’t get up the stairs unaided though, she’s almost ninety, I had to carry her. By the time we got to the top floor she’d passed out and Abbas was having an asthma attack.’

He looked imploringly at Sutton. ‘Did I do the right thing? Perhaps I should have gone and tried to force the back door open instead. Then she could have got out. But if I’d done that, maybe we’d have ended up trapped downstairs.’

‘I don’t know,’ said Sutton softly, ‘but I do know that your quick thinking made a big difference. You bought everyone valuable minutes for the fire service to arrive.’

It was the best he could offer.

Mehmud smiled his thanks.

‘Before we go any further, do you have any thoughts about who might be responsible?’

For the first time since they’d arrived, the man’s politeness slipped.

‘Bloody obvious, isn’t it? A coach-load of fascists and Islamophobes turn up in the town centre and distract the police, then we get torched. It doesn’t take a rocket scientist.’

‘We’re keeping an open mind at the moment,’ said Sutton, cautiously.

Mehmud took a deep breath. ‘Of course, you’re right. I apologise.’

‘Have you had any other incidents recently?’ Hardwick took over.

Mehmud shrugged helplessly. ‘Some graffiti appeared a couple of nights ago. I didn’t have any paint to cover it up. Before that, nothing really. We get on pretty well with the neighbours. I know that some of my brothers and sisters have been insulted in the street, especially if they are wearing the veil, but Middlesbury is a lot better than some places. The community centre hasn’t been attacked in years, not since nine-eleven or the London bombings.’

Sutton looked at his notes. ‘Can you remember what night the graffiti appeared?’

He thought for a moment. ‘Wednesday night or Thursday morning, I think. We hosted a meal after sundown to celebrate breaking the day’s fast. I locked up about midnight and there was nothing on the wall then.’

The same night the CCTV cameras had been vandalised.

Chapter 5 (#ulink_792c46e6-5468-5351-9cba-01413002dcb4)

Visiting the newly bereaved was something that Warren never found easy. Today promised to be even trickier than usual.

To the casual observer, Middlesbury was a quiet, prosperous market town, populated by well-to-do professionals attracted by its semi-rural location, close proximity to Cambridge and Stevenage, and trains that could get you to central London in less than an hour.

All that was true – the house prices certainly favoured the upper-middle classes – but you only had to scratch the surface of anywhere to see its true character. A closer look showed the town’s real inhabitants, its beating heart.

Just under half of Middlesbury’s inhabitants earned less than the median adult wage for the UK. The proportion of residents claiming out-of-work or disability benefits were broadly in line with the regional average and the number of households requiring housing benefit was typical for a town of its size. But as is often the case, such raw statistics obscured the real story.

Three-quarters of Middlesbury’s poorest households lived in a single area, known locally as the Chequers estate – the six tower blocks being named after Prime Ministers from the first half of the twentieth century.

The name was the grandest thing about Churchill Towers, the ten-storey block that Mary Meegan lived at the top of. Had it not been for the two uniformed officers standing conspicuously at the entrance to the building, Warren would have thought twice about leaving his car unattended in the only parking bay not occupied by either a police car or dumped furniture.

Warren peered up at the balconies jutting out of the side of the building. Some had washing on clothes horses, a few had pot plants. Most had people staring at him.

‘Fuck the pigs!’ spray-painted across the doors completed the montage.

‘Ever get the feeling we aren’t welcome here?’ muttered Gary Hastings as he joined Warren.

The call button for the lift remained unlit and it was only the loud clanking and whining from the mechanism that reassured Warren that the stairs wouldn’t be necessary. He almost wished he’d opted for the exercise when the elevator finally arrived. A potent smell of urine, stale beer and cigarette smoke – somebody had tried to burn the no smoking sticker – engulfed the two men as they climbed into the empty lift. Hastings beat him to the number ten button. Turning so that he could face the doors, Warren felt the soles of his shoes sticking to the linoleum flooring.

‘Do you think that’s dog?’ asked Hastings, his face an even sicklier colour under the harsh fluorescent lighting. Warren eyed the sticky brown mess at the edge of the lift. ‘I hope so.’

Apartment ten-fourteen was a dozen steps down the corridor. The uniformed police officer standing outside greeted Warren and Hastings politely, before ringing the doorbell and stepping to one side.

Warren didn’t know what to expect when the door opened into the two-bedroom flat that Mary Meegan, her husband and their two boys had lived in since the late Seventies. Before he’d arrived, Warren had been prepared for everything from Nazi memorabilia and a swastika carpet to snarling Rottweilers and St George’s flag wallpaper. Then upon arrival at the tower block he’d feared he’d be stepping into a dwelling from one of those dreadful ‘how clean is your home’ filler programmes that Channel Four seemed so fond of.

He wasn’t expecting tasteful floral-patterned wallpaper, deep, shag pile carpet and shelves of carefully chosen miniature porcelain figurines. The leather couch was plainly well used, but the polished wooden arms were evidence that the glass drinks coasters weren’t just because Mrs Meegan had visitors. The building around her might be filthy and neglected but she clearly had her standards.

Mary Meegan was a smoker – that much was evident from the thick crevices that lined her face and the staining of her teeth. Nevertheless, the room smelt of air-freshener and furniture polish. A faint breeze carried the smell of cigarette smoke from the open balcony, where Mrs Meegan no doubt partook of her habit and banished similarly addicted visitors.

Through the window, Warren could see the backs of two men seated at a metal table, flanked by large earthenware flower pots containing lovingly maintained bonsai trees. Both had shaven heads. Both of them, he’d want to speak to.

‘Mary, this is Detective Chief Inspector Jones.’ The Family Liaison Officer was a young man with sympathetic eyes.

Mary Meegan turned her head slowly, almost dreamily. The FLO flicked his eyes towards the breakfast counter, where a bottle of whisky sat, half empty.

‘Hello, Mrs Meegan. I’m DCI Jones and this is my colleague Detective Constable Hastings, we’re part of the team that are investigating the death of your son. We’re very sorry for your loss.’

‘Bollocks.’

The speaker had emerged from a doorway that Warren assumed led to the bathroom.

Even without seeing the mugshots that morning, it was clear that this was the brother of the murdered man. Dressed in a white England football shirt and black tracksuit bottoms, he did nothing to hide the tattoos crawling up the side of his neck and covering his sinewy forearms. He stepped forward and Warren caught the whiff of cigarettes and whisky on his breath. He forced himself not to recoil.

‘Jimmy Meegan, I presume?’

The man ignored him.

‘Why are you around here, harassing my mum? You should be out there on the streets arresting the bloke that killed my brother.’

It wasn’t exactly how Warren had planned to open the questioning, but he decided that since Meegan had brought it up, he may as well go with the flow.

‘That’s what we are intending to do. Perhaps you could help us with that. Do you have any suggestions about who may be responsible?’

Meegan stepped even closer.

‘Take your pick, there’s fucking hordes of them.’

Warren had to ask, but he already knew what the answer was going to be.

‘The fucking Pakis. The Muslims, the Sikhs, the Jews, the place is full of them. Half the bastards live in this building. Go out there and start arresting them, you’ll find who did it quick enough. Fingerprint them all and you’ll probably solve most of the unsolved crimes in town.’

Out of the corner of his eye, he could see Hastings trying to keep a blank face. The Family Liaison Officer looked bored; no doubt he’d been hearing this all morning. Unfortunately, Jimmy Meegan was only just getting started.

Warren had dealt with racists a lot over his career. You didn’t spend your early uniform years in such racially diverse cities as Coventry and Birmingham without encountering your fair share of bigots, from all communities. Sometimes it could be dealt with as a public order offence; a verbal warning about use of abusive and racially charged language would usually quieten most of the people he encountered. If that didn’t work, and especially if alcohol was involved, handcuffs and the back of a police van would at least remove them from the scene and ultimately make them the custody sergeant’s problem.

In circumstances such as this, the heavy-handed approach wasn’t really appropriate. Warren recognised that Jimmy Meegan was grieving the death of his big brother. Furthermore, the dilated pupils, reddening of the nostrils, and the obsessive scratching of his left forearm suggested that a presumptive cocaine test on the traces of powder on the man’s top lip would come back positive.

Warren chose his next words carefully, but before he could mouth them he was interrupted by an unexpected source.

‘I’ve told you not to use that language in this house.’

Mary Meegan’s voice was rough, but had the edge of one used to being obeyed. Jimmy Meegan’s eyes flicked towards his mother. For a moment he looked as though he was going to protest, before he shrugged and stalked across the room to one of the armchairs, where he grabbed a grey hoodie.

‘You know I’m right,’ he muttered. ‘Pigs don’t care about us. They don’t care who killed Tommy. We’re an endangered species in our own country.’ He sounded as if he was about to start again, but his mother silenced him with a glare.

‘Boys, we’re going to the pub.’

Ideally, Warren would have liked to interview them there and then, but he could see that Jimmy Meegan was not going to be any help and he decided he’d rather have him and his two cronies out of the way for the time being.

‘Jimmy, I’d like to talk to you later. Do you have a number I can contact you on?’

Warren tried to make his tone as conciliatory as possible.

‘He’ll be here,’ said Mary Meegan.

‘And what about you gentlemen? I’m sure you have plenty of information you’d like to share.’

The two men entering the apartment from the balcony obviously shopped at the same clothing outlet as Jimmy Meegan, and shared his tastes in hair styling and body art. But that was where the similarities ended. The first of the men was hugely obese, his enormous belly straining through the T-shirt. His florid, sweat-spotted face and wheezing made Warren mentally bump him to the top of the interview list, if only so they could speak to him before he dropped dead of a massive coronary. He walked past Warren and Hastings without even looking at them.

His companion was exactly the opposite, the man looked almost emaciated. A gold earring in his right earlobe matched his right incisor, which flashed as he sneered at Warren. ‘I’ll make sure my assistant contacts your office to compare diaries.’

Warren resisted the urge to respond in kind. It didn’t really matter if they refused to give their addresses, he recognised both men from the briefing notes he had read that morning. Harry ‘Bellies’ Brandon and Marcus ‘Goldie’ Davenport were well known and could easily be picked up for questioning back in Romford if necessary.

The police officers waited until the three thugs swaggered out the door, before turning back to Mary Meegan.

‘As I was saying, Mrs Meegan, I’m very sorry for your loss and I promise you that my colleagues and I are doing everything we can to catch your son’s killer.’

The older woman stared at the floor for a few moments without saying anything and Warren debated whether or not he needed to repeat himself. Perhaps a little louder – he’d just noticed the discreet hearing aid.

‘Sit down and take the weight off. Can I get you boys a cup of tea?’

She started to get up. Warren blinked in surprise; he hadn’t expected this. Before he could respond, the Family Liaison Officer spoke up.

‘I’ll get it, Mary.’

As the officer busied himself in the kitchen, Warren mentally changed tack. He’d been anticipating a hostile reception from Mrs Meegan – a woman who it was reported had experienced more than her fair share of run-ins with the police, albeit indirectly through her late husband and wayward sons. An offer of a sit down and a cup of tea was the last thing he’d expected.

‘You know, they aren’t bad boys. Not really.’ The old woman’s voice was gravelly and slightly wistful, but it had lost its dreamy quality. Warren detected no slurring and he suspected that whilst Mary Meegan may have had a glass of whisky to settle her nerves, most of the bottle had been consumed by her visitors.

She indicated towards a picture on the wall. ‘It was him that made them the way they are.’ The photograph of Ray Meegan enjoyed a prominent place above the three-bar electric fire. On the mantelpiece, flanked by yet more porcelain statuettes, a colour wedding photograph showed far younger versions of the man in the portrait and somebody immediately recognisable as Mary Meegan. Whilst Ray Meegan was never what you would call handsome, something that his lank moustache and purple velvet suit hardly helped, Mary Meegan had been a real head-turner back then. Even her thick-rimmed NHS glasses could do little to hide her pretty features; in the same way that the large bouquet of flowers barely concealed her large bump. A shotgun wedding, it would seem.

‘I knew he liked a drink with the boys when he went to the football on a Saturday, but it wasn’t until he was arrested that I realised the truth, silly bastard.’ She shook her head. ‘The first time, it was for knocking a policeman’s helmet off. He thought it was all a bit of a laugh. A night in the cells and that was it.’

She sighed. ‘Or so I thought. The next time he got arrested, it was more serious. He glassed someone in the pub. He claimed it was self-defence. He and his mates were celebrating a win when the losers attacked them.’

Now her expression turned to derision. ‘I took his word, if you can believe that?

‘I went to court expecting him to get off, but the prosecution produced a dozen witnesses, some of them supporting his own team, who claimed that Ray and his mates started the fight. That they’d spotted the two lads on their own and started calling them names. One of the lads was Asian and he reckoned Ray called him a “Paki” and told him to go home. Nobody else heard that, so the magistrate dropped the racially aggravated bit, but he still got six weeks for assault.’

Warren had only skimmed the file on Ray Meegan, since he was more interested in his son, but his gut told him that Mary Meegan had things to say worth listening to.

‘When he came out, he claimed he was done with the football and the violence, but it didn’t last. He used to be a taxi driver, but the council were tightening the rules and didn’t think he was suitable. He drove minicabs for a while, but there were too many foreigners prepared to work for peanuts and he couldn’t earn enough to put food on the table.’

Warren could see where the story was going now.

‘I guess it colours your view of folks when you think they’re out there taking your job. It certainly did for my Ray.’

She sniffed. ‘By the time the boys were at secondary school a load of immigrants had turned up to work on the building sites. My Ray kept on applying – he was a big bloke and not scared of a hard day’s work – but they turned him down. Reckoned he was too expensive. The Asians would do it cheaper.’

She sniffed again. ‘At least that’s what he said. I reckon it was because he had a criminal record. Besides, these young lads were half his age and twice as fit. Still, he blamed it all on the Indians or the Pakistanis. He used to talk about it all the time at the dinner table. I told him not to use the P word in front of the boys, but he ignored me.

‘And then he started taking the boys to the football. I didn’t want him to, but he promised me he’d keep away from any trouble and said that he wouldn’t be a real dad if he didn’t take the boys to the footie. For some of his mates Saturday at the match followed by the chippie was the only time they spent with their kids. I was just glad that we weren’t like that.’

She paused again, taking a mouthful of her tea, grimacing at the cold temperature.

‘Let me get you a top-up, Mrs Meegan,’ interjected Hastings.

She smiled at him and handed him her teacup, which he carried back to the kitchen.

‘Do you think their father’s employment situation helped form the boys’ political views?’ Warren asked carefully.

Mary Meegan laughed throatily. ‘By “forming their political views”, do you mean “is that why they are nasty racists?”’ She answered her own question. ‘’Course it is. I believed Ray when he said he was keeping the boys away from any trouble at the football, but you tell me where the hell a nine-year-old learns to throw a banana at the TV when a black player comes on the pitch? I threatened to tan Tommy’s backside if he ever used that language again, but Ray laughed and said it was just a bit of fun.’

Mary Meegan slumped into her seat, as if the wind had been let out of her, and for the first time Warren saw the pain in her eyes.

‘Mrs Meegan, do you have any idea who might have attacked your son?’

Warren wasn’t expecting any great insights, but Mary Meegan was a lot more clued-in than she might at first seem.

‘It’s like Jimmy said – take your pick. They think I’m a fool, that I don’t know what they get up to. Until today they’d never really made the news and I don’t think they had any idea how much I know about them.’ She smiled sadly. ‘I don’t exactly bring it up over Sunday lunch – not that I ever see them for Sunday lunch these days.’ The smile disappeared and her bottom lip trembled. ‘I just want my boys with me. The way it used to be.’

She cleared her throat loudly and fished a handkerchief from out of her sleeve. Warren picked up his own teacup and joined Hastings and the Family Liaison Officer in the kitchenette. Mary Meegan was a proud woman and would want a few moments to compose herself. By the time they returned a minute later, it was as if nothing had happened. She took the fresh cup of tea from Hastings with a grateful smile.

She pointed at the laptop on the dining table.

‘They think I just use that for online shopping. It was an old one that Tommy gave me. But there’s a silver surfer club at the library. One of the boys that helps out upgraded it. Now I can use it for looking at Facebook and surfing the web.’ Her face darkened. ‘I’m not an idiot. I know exactly what they’re involved in. I even follow them on Twitter. I see what people post on there. The language they use… the threats…’ Again, her bottom lip trembled. ‘They used to try and hide it from me – still scared of their old mum,’ she barked. ‘But by the time they’d both been to prison it was obvious. They started showing off their tattoos, horrible things.’ She shuddered. ‘It’s as if they want to be unemployed. They’re supposed to be painters and decorators, but who’d let someone looking like that into their house?’

‘So they aren’t working?’

‘Not really. Tommy moved down to Romford about five years ago, the last time he was released. He said it was to set up as a decorator – he completed a City and Guilds in prison – as a mate had some work on. But I’m not daft. That part of Essex is full of right-wingers. Jimmy joined him three years ago when he got out and they were supposed to set up a business together.’

‘But they didn’t?’