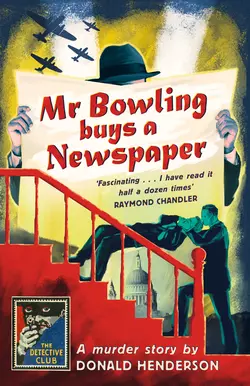

Mr Bowling Buys a Newspaper

Martin Edwards

Donald Henderson

In Raymond Chandler’s favourite novel, Mr Bowling buys the newspapers only to find out what the latest is on the murders he's just committed…Mr Bowling is getting away with murder. On each occasion he buys a newspaper to see whether anyone suspects him. But there is a war on, and the clues he leaves are going unnoticed. Which is a shame, because Mr Bowling is not a conventional serial killer: he wants to get caught so that his torment can end. How many more newspapers must he buy before the police finally catch up with him?Donald Henderson was an actor and playwright who had also written novels as D. H. Landels, but with little success. While working for the BBC in London during the Second World War, his fortunes finally changed with Mr Bowling Buys a Newspaper, a darkly satirical portrayal of a murderer that was to be promoted enthusiastically by Raymond Chandler as his favourite detective novel. But even the author of The Big Sleep could not save it from oblivion: it has remained out of print for more than 60 years.This Detective Club classic is introduced by award-winning novelist Martin Edwards, author of The Story of Classic Crime in 100 Books, who reveals new information about Henderson’s often troubled life and writing career.

‘THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB is a clearing house for the best detective and mystery stories chosen for you by a select committee of experts. Only the most ingenious crime stories will be published under the THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB imprint. A special distinguishing stamp appears on the wrapper and title page of every THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB book—the Man with the Gun. Always look for the Man with the Gun when buying a Crime book.’

Wm. Collins Sons & Co. Ltd., 1929

Now the Man with the Gun is back in this series of COLLINS CRIME CLUB reprints, and with him the chance to experience the classic books that influenced the Golden Age of crime fiction.

Copyright (#ulink_81788b9e-826e-57e9-9d8d-2dbf8c156352)

COLLINS CRIME CLUB

an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by Constable & Co. 1943

Introduction © Martin Edwards 2018

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008265311

Ebook Edition © February 2018 ISBN: 9780008265328

Version: 2017-12-14

Dedication (#ulink_af91fcc9-c9d0-5cf1-bf61-8fb3bc2cd905)

With love

to Roses

Contents

Cover (#ua7748335-9eea-57d1-84c4-bae395b82fe1)

Title Page (#u07f8b083-2371-5ebe-a7ad-7276637bfb03)

Copyright (#uc02e588d-ce48-5236-8a34-0120fb414899)

Dedication (#u2c9dd47c-4571-59ff-8256-9f1d5dc73f87)

Introduction (#u63f2c305-cd53-5234-b77b-5e4e6b3138b6)

Note (#ua1f5202a-2854-5797-ae71-22eba3f656ea)

Chapter I (#u903f47b3-48d8-5aa9-bd96-38baaca0685b)

Chapter II (#u5e5ce95d-d4aa-5188-8c3b-45d79e7b29ea)

Chapter III (#u8c8c2532-fc77-54a9-880b-e67407caf5a1)

Chapter IV (#u28d263e7-1516-5e9e-90ee-b47e4a1072eb)

Chapter V (#u3758277c-244f-5218-950c-088aa0d865c4)

Chapter VI (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter VII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter VIII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter IX (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter X (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XI (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XIII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XIV (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XV (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XVI (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XVII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XVIII (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XIX (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XX (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XXI (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter XXII (#litres_trial_promo)

The Detective Story Club (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

INTRODUCTION (#ulink_d3753329-dc04-55e1-9419-f2b9a1270d53)

DONALD HENDERSON’S Mr Bowling Buys a Newspaper earned considerable acclaim when it was first published in 1943, but for many years the book has been out of print. This neglect seems unaccountable, given that its admirers included Raymond Chandler. As readers of this welcome reissue will find, Henderson crafted a distinctive work of fiction; what is more, the story behind it is equally intriguing, while the tale of the author’s life is not only thought-provoking but also poignant.

Chandler wrote ‘The Simple Art of Murder’, his critical essay about the crime genre, which famously proclaims ‘down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid’, for the Atlantic Monthly. It appeared in December 1944, not long after Henderson’s book was published. Having flayed several leading writers of classic whodunits, Chandler talked at length about Dashiell Hammett’s gift for writing realistic crime fiction, before saying: ‘Without him there might not have been … an ironic study as able as Raymond Postgate’s Verdict of Twelve … or a tragi-comic idealization of the murderer as in Donald Henderson’s Mr Bowling Buys a Newspaper …’

To have one’s book name-checked by such a major author, and in an essay which has been much-quoted over the years, would be a fillip to any struggling novelist’s career. Tragically, Henderson did not gain any long-term benefit from it; less than three years later he was dead, at the age of 41. In the course of his short and often troubled life, however, he published fourteen novels, as well as non-fiction books, stage plays and radio plays.

Until recently, little was known about Henderson, and even less had been written about him and his work. Thanks to the diligent and invaluable research of Paul T. Harding, much information has come to light, and Henderson’s fragmentary archive has been presented to the University of Reading. Paul Harding has also edited an unpublished memoir written by Henderson; its title The Brink comes from the final sentence, which sums up the author’s bleak worldview: ‘There is always a chasm gaping at one’s feet, and although merry enough about it, most people finally get a little tired of hovering on the brink.’

Donald Landels Henderson was born in 1905; he had a twin sister, but their mother died four days after giving birth. Henderson’s twin, Janet, also died in childbirth, when she was 28. Their father re-married when the twins were four, and Henderson was to say, ‘I cannot pretend to have enjoyed anything very much about my childhood or adolescence.’ He was educated at public school, and under pressure from his businessman father he took up a career in farming. But agricultural life didn’t suit Henderson, and a stint as a publisher’s salesman brought only misery. He enjoyed better fortune working for a stockbroker, but he abandoned the City in his mid-twenties during a turbulent period when he suffered a nervous breakdown.

Since his teens, he had enjoyed acting, and had also dreamed of becoming a writer. He joined a touring repertory company, and married an actress called Janet Morrison, a single parent who later gave up her son for adoption. The marriage soon failed, and the couple separated, although they did not divorce for some years.

Henderson began to combine writing with his acting career, but this was a period of worldwide economic depression—‘the Slump’—and money was always short. Chapter titles in The Brink such as ‘Poverty Street’, ‘Another Failure’, ‘Disaster’, and ‘The Awfulness of Everything’ give unequivocal clues to his melancholy during much of the Thirties. He had parts in plays such as Rope by Patrick Hamilton, a writer with whose dark thrillers his own work is sometimes bracketed.

After a failed theatrical venture in London, ‘I was not in a fussy mood … I got a room in Surbiton … and in a fearful burst of enthusiasm I sat down and wrote three novels running, scarcely leaving myself time to think them out, so anxious was I to get farther and farther away from the brink of the precipice. The books in question were Teddington Tragedy, His Lordship the Judge and Murderer at Large, and they were published between October 1935 and October 1936. In his memoir, Henderson supplies little detail about the influences on his crime fiction, although he acknowledges that the nineteenth-century case of the serial killer William Palmer was an inspiration for Murderer at Large.

Henderson’s account in his memoir of his time in farming gives, perhaps unintentionally, a hint about the dark side of his mind: ‘There were a lot of rats on the farm and I enjoyed many a rat hunt with the dogs. Sometimes you didn’t need dogs … We were constantly rat trapping, at which I became really expert, and I know of few greater thrills, including getting a book accepted, than hurrying along next morning to see if you have caught anything and finding that two angry, terrified little eyes are staring at you murderously. Or even more than two.’ His account of the homicidal career of Erik Farmer (was the surname a nod to his previous profession?), the loathsome protagonist of Murderer at Large, is equally chilling.

Procession to Prison, a crime novel about a ‘trunk murderer’, appeared in 1937; it was well received, but thereafter Henderson ‘could sell nothing I wrote for fully two years … The irony of the literary life, as I have experienced it, seems to lie in the fact that, when you are all but down and out, you can write well, but your luck is never any good from the selling point of view. Poverty breeds more poverty.’ Henderson tramped the streets of London and Edinburgh looking for work ‘with my press cutting book under my arm’, but without success. He had lost his nerve as an actor, and seems—although the chronology of his memoir is vague—to have spent two summers camping out in the open. After a spell in hospital, he tried to put together a book of famous trials, but failed to interest a publisher in the project.

He had better luck with a comedy thriller play called The Secret Mind, but his attempts to enlist for military service were rebuffed, and he became an ambulance driver, only to be badly injured during the blitz in September 1940. The following year, deemed unfit even for work in civil defence, he started to write a new novel—Mr Bowling Buys a Newspaper.

Henderson’s explanation in The Brink of the concept he had for the book was striking: ‘It was to be a religious novel, but because publishers and everyone were always so terrified of religion, or bitter about it, unless very delicately presented, I would also make it a murder novel, to help the sales. It had a magnificent plot—though I am bad at plots—and of course I should be told I had written a “detective” story because there happened to be a detective in it. But that didn’t matter, as long as I sold it. It would be, for a change, about a man who wanted to get caught, and hanged, because he was rather browned off about life in general … I broke my rule and started this book without knowing for certain what the end would be … I decided that there must be plenty of humour in the book, to take the edge off the sombre, brooding background … I wrote the book with fearful haste and enthusiasm … in about a week and a half, straight onto the typewriter.’

The book struggled at first to find a publisher, and after another spell of acting, Henderson joined the BBC. Finally, things began to look up. He again came across Rosemary (‘Roses’) Bridgwater, who had been his girlfriend many years earlier, and once he had secured a divorce from his first wife, they married and moved into a flat in Chelsea. The novel eventually sold both in Britain and the US, and attracted positive reviews. Not everyone, however, was as impressed as Raymond Chandler. In The Brink, Henderson quoted a letter sent to his publishers by someone from Edinburgh who signed themselves as ‘Lover of Clean-Minded Literature’ which began:

‘I have read Mr Bowling Buys a Newspaper and paid 8/6d for it. With the exception of Mrs Agatha Christie and also Miss Anna Buchan, I will never again buy a book without first hearing it recommended by a friend. This book is the last word in filth and should never have been printed by you …’

For Henderson, though, the popularity of the book ‘made up to me for years of despair’. He wrote a new crime novel, Goodbye to Murder, in about ten days, and adapted Mr Bowling Buys a Newspaper for the stage. His wife gave birth to a son in January 1945, although a second son, born in December of the same year, died when only a few days old. The play of the book was staged in 1946, achieving critical success, and the film rights were sold. At this point, the manuscript of The Brink comes to a rather abrupt end. Henderson’s health was failing, and he died of lung cancer on 18 April 1947. Although Mr Bowling Buys a Newspaper was televised live by the BBC in 1950, and again in 1957, inevitably his reputation began to fade.

Yet his writing, at its best, is distinctive enough to deserve reconsideration. The principal influences on his crime fiction are surely not Hammett, as Chandler suggested, but rather C. S. Forester, author of Payment Deferred (Henderson’s memoir mentions the homicidal protagonist, William Marble, in the context of a discussion about Charles Laughton, who played Marble in the stage and film versions of the book) and Francis Iles, author of Malice Aforethought and Before the Fact. Forester and Iles wrote with a chilly irony that also runs through Henderson’s work, and that of other occasional crime novelists of the period, such as C. E. Vulliamy, Bruce Hamilton and Raymond Postgate. ‘I would not like to say where my fascination for murder and disturbed mental conditions came from,’ Henderson said. Whatever its origins, it resulted in his producing a handful of books as unorthodox as they are powerful.

MARTIN EDWARDS

July 2017

www.martinedwardsbooks.com (http://www.martinedwardsbooks.com)

NOTE (#ulink_48948dbb-beb7-5c16-9b2b-e486d803569e)

THE characters in this book are fictitious; no portrayal of any person, living or dead, is intended.

CHAPTER I (#ulink_b722a0eb-4885-588c-b24e-fe12c87f009d)

MR BOWLING sat at the piano until it grew darker and darker, not playing, but with Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto in D Flat Minor opened before him at the first movement, rubbing his hands nervously, and staring across the shadowy room to the window, to see if it was dark enough yet. The window was wide open, and at first the evening was a kind of green, such as you would expect in a London summer, then it got grey, then it got muddy brown; then it turned black and safe. It was not that he was going to do anything very special, but he got into moods when he didn’t care to talk to people. In just the same way, he often got into desperately lonely moods; moods which might have been called suicidal, had he not been a man incapable of committing suicide, for he had too much of a sense of humour for such a cold and deliberate act. He went quietly past the little telephone cupboard, paused outside his door and listened. Then he stole past the two doors and the thin staircase which led to the top floor, taking the broader staircase down to the second, and then the first floor. He passed various doors on the ground floor and slipped out into the square and was soon in Notting Hill Gate. In his public school accent, he asked for an Evening Standard. When there wasn’t one left, he said he would take anything, he didn’t care, on this occasion, what the paper was. It wasn’t war news he was after, he had put the war out of his mind, so far as it was possible. He was bored with war and felt entitled to be. You could regard it as peace time if you liked, if you had a good imagination. He stumbled along in the blackout to the Coach and Horses, where it was cheery, and where one of the barmaids wasn’t too bad, though seeing her made him decide once again: ‘I’ll never kill a woman again! Not on your life! Things happen you don’t expect!’ All the same, he’d had to do it, it was a Heaven-sent chance. There was something about the bachelor feeling, after those dreadful years, that dreadful woman, poor thing, whatever you do, don’t marry too young. He ordered a large whisky, two shillings, but who cared, drank it neat and ordered a pint of Burton and Mild, made a few mumbling remarks and gave his quick, head-jerking expression, like a polite man not really listening, and went along to the sandwich counter. He ordered soup and some ham sandwiches and started in at his paper. He peered all over it, up and down and round about. There was nothing. It was all right. There was nothing at all. He had another look, saw a Standard discarded on a seat, pinched it and looked all through it, and set to at his sandwiches. He tossed back his beer in two gusts. There was the shadow of him on the white wall. His head going back, his thick hands holding the tankard, his blue jacket rather solid. His second murder, and he’d got away with it. Perhaps the body had been found, and perhaps it was in the morgue, but there was nothing whatever about Mr Watson in the papers, after three whole days. He ate his sandwiches and soup together, sipping at the brown soup, and then biting at a sandwich. Then he ordered some more beer, he liked beer, though it gave him a bit of a pot belly. Then he ordered a cigar. He paid one-and-six for it. Then he went out and fumbled along up the hill to the pub he liked called The Windsor Castle. He liked the public bar there, it was like a country pub, there were benches and two lots of darts going on. He sat and had a bit of a think. He got a glimpse of himself in the mirror there and thought: ‘Well, I dunno, I think I look rather decent.’

Across the bar, a girl sat with a soldier and said about Mr Bowling: ‘There’s that man who often comes in here. Doesn’t he look awful? There’s something about him.’

But over in Ebury Street, Victoria, the crowd thought he was marvellous. Queenie often said: ‘Oh Lor’, I’m fed up, let’s ring up poor old Bill! He’ll cheer us up, and at least he’s a gentleman!’ She’d get busy dialling Park 4796. She did it now and the others sat around with the Watney bottles. ‘Hallo? Oh, could I speak to Mr Bowling, please? Is it a trouble?’ Only, sometimes one of the other tenants answered the telephone, instead of the maid, thinking it was for them most likely, and they got snooty when it wasn’t for them. ‘He’s out,’ they’d say without going to knock.

‘I wonder if you could be so kind as to give him a message when he comes in? It’s Queenie Martin, he’ll know. We’d love him to come over?’

… Stumbling back from The Windsor Castle, Mr Bowling went in to Number Forty and hurried up to his room. He was just beginning to feel pretty good. Regular practice during the blitz had given him a pretty good head, and all that subsequently boring time in the Ambulance Service, until he got himself invalided out with his queer heart, so it needed a good deal now to feel really good. He told himself he felt perky. He was just beginning to get the feeling of being a bachelor again, and living alone in a room in the old way which he so used to hate. A man married for reasons of loneliness, and so as to make love regularly, in his view, more often than for any other reason. Sometimes, if he was lucky, for money. If he was really lucky, he married for love. But there, some people had the luck, others didn’t. He put on the light and sat on the divan thinking: ‘I expect I look rather nice, sitting here, rather a quiet sort of chap, sad.’ He smiled in the way he would have smiled had someone been watching who was prepared to say: ‘Poor old Bill! There, there! There, there!’ He started to have a little cry. He cried into his thick hands. There were so many reasons for those tears, they started so very long ago. He thought: ‘I’m not a sinner at all, really. No worse than the next chap. I’d help anyone. I jolly soon started in at war work. It was partly the change, we all like change, and I got fed up with insurance. I never thought of this new line, not then. Not until we got a direct hit and we got buried, and she started up that awful screaming. And I put my hand on her mouth, close to her nose. My, she went out quickly, like a snuffed candle. It was only murder if you analysed it. There were worse things. Blackmail was worse. Homosexuality was worse. Who said murder was the only capital crime? It wasn’t so in the old days. You got stoned to death for all sorts of things. Poor old girl, but she was a cow, a real cow, what a cow she was. Poor old dear. And if it hadn’t been me, it might have been the roof falling in. Who could tell? Anyway, it’s between me and my God.’ And he thought: ‘And for the first time, I got a bit of money out of something! Insurance! I’d never even thought of that!’

The maid had done the pink curtains and the blackout. He was moving to the piano when he saw the note under the door. Queenie. May as well go over, she might have some gin. He got his bowler hat again and lost no time in going out and across to the District Railway. He found Queenie and the crowd full of larks, all the Services represented, military and civil defence, and hardly room to breathe. ‘Struth,’ he said in his public school accent. ‘No air at all! I shall pass out!’

‘You pass out,’ Queenie said. ‘Here, dear, have some gin. I saved it.’ Queenie’s husband was tight and lay on the bed. He was a very boring man who had a job in the M.O.I. They all looked like him up there.

There were a pair of twins, kids in the A.T.S.

Mr Bowling thought:

‘I wonder what this crowd would think if they knew.’

And he thought:

‘Perhaps they will know soon. I’m doing my level best.’

But perhaps this train of thought was the gin.

CHAPTER II (#ulink_9df2afd8-bf01-5405-816f-189ef2b2c1ae)

BEFORE he killed his wife, which in a sense had not been premeditated, not really, Mr Bowling had reached such an intense pitch of despair about life, that he had thought of doing a murder and more or less making it reasonably easy for the police to catch him and arrest him. It was quite an honest thought, and it recurred now and then when he had had a drop of gin. After all he had been through since leaving school, all the bitter disappointments, and above all the drabness and the poverty, and his awful marriage, he had frequently and honestly felt that to get into the public eye in this way would be better than dying at last utterly unknown and exhausted spiritually. His music had failed to get him into the public eye, and goodness only knew how hard he had worked for many years, why not make a sensation of this sort? Repression, no doubt. And sex starvation. Soul starvation. Ordinary starvation, too. To hang, would at least end it and be better than suicide. And to win the appeal and get twenty years, even that would be better. Twenty years rent free and all found wasn’t so bad, ask anyone who knew about these things, these years between wars? Ask them! What a joy this new war was, after the disappointment of Munich! ‘It’s Peace,’ the placards all said. Hell, the same old humdrum, on we go as before! And then September the third. And then at last the bombs. Frightening, yes, but thrilling. Change. Who looked forward to the next peace, and the cold, starving agony nobody knew how to prevent?

He started up a coughing fit.

He swore. Somebody tapped angrily on a wall. ‘Bitch,’ he said. A man couldn’t even cough in his own home.

Suddenly it dawned on him that this wasn’t much of a home. The one thing which had made him stick his marriage was the bit of a home, it was the carpet, a nice red one. And then a direct hit, and the whole lot gone, how glad he was. Coughing, then, in the dust and mess, he’d thought, well, thank God, now a wealth of ugly memories are gone forever, photographs, books, ornaments, yes, even the bloody carpet, you can have the lot! They stood imprisoned together in a kind of black pit and she’d started up that screaming right in his ear, and he’d put out his hand. ‘Are you hurt?’

‘No …!’

‘Well, shut up screaming, we’re not trapped, there’s a light, it’s the street!’ It was the Fulham street. ‘See?’

But she screamed like a maniac.

It was easy to stop it.

The insurance money came to a thousand quid.

Not surprising a chap began to get ideas. And you could say it was for art?

He stumbled from pub to pub and liked to say:

‘I’ll get somewhere with my music now! No more worry! No more drabness! And nobody can say I’ve done nothing for the war? Two years in the Civil Defence? My home hit, everything gone? I’ve lost the lot, my dear chap, but I’m not grumbling! I’ll pick up again! Watch me!’

He kept on with the firm and went to see ‘the office’ just as usual, and was just as patient with Mr Watson, his most self-centred client. Mr Watson depressed him very much, a dreary fellow in a brown trilby hat, with a brownish outlook. He thought we should lose the war, because he didn’t think any Empire had the right to rule for more than a thousand years. He wasn’t a conchie, but on his own admission, only because he had not the moral strength to face a tribunal. All he thought about was whether his money was safe, and whether his various bits and pieces were safely covered by insurance policies. He never missed a premium, never had a drink, never had a woman. He said so. It was the way he put it. Women were a sort of meal. But he was never hungry. He’d been married, but you could only imagine what it must have been like. Perhaps just at Christmas, just to cheer the old woman up.

Mr Watson lived in Fulham too, Number Ten, Peel Road, one of a row of little red houses. At the back was a row of little gardens, mostly full of potatoes and cabbages now, the war effort. Quite a lot of houses had been hit in Fulham, so that London looked like a dirty old woman who had had a lot of her teeth out. She grinned, waiting for the dentist to come back again and pull out a few more. Perhaps the dentist would come again and perhaps he wouldn’t, for the present her agony was almost forgotten. The neighbours thought: ‘Yes, but she looks tidy again. More or less.’ Mr Watson had a married daughter called Mrs Heaton who came up from Kingston about twice a year. She wore rather cheap furs and ran a baby Austin. Mr Bowling was very interested because he knew she wouldn’t get a penny when Mr Watson died, although she fondly thought she was going to get everything. Mr Watson had one day confided his will. The money was going to a dogs home. Mr Watson had been so fond of a spaniel which had passed on, he would not purchase another dog. But he liked to visit various doggie establishments, and in the parks would stop all and sundry and enquire of the owners their endearing habits. So there was something human about him, like there was about everyone if you searched really hard. After his wife’s funeral in Fulham, and after he had got his affairs a little in order, War Damage Claim safely listed and sent in, and his furnished room in Notting Hill Gate chosen, a nice long way off, Mr Bowling sat on his divan and had a bit of a think about Mr Watson. He thought how awful he was about money, it was dreadful wanting money just for the sake of having it in the bank, better to collect fag cards, for all the good it did you or anybody else. You could forgive a decent motive. You could not forgive miserliness. It was, he confessed to himself, a little like trying to find a reason for murdering Mr Watson, but it had to be admitted he was a fair and sporting choice. If he was a happy, generous man, one would not dream of plotting against him, it wouldn’t be cricket. And then, another sound reason, he’d fled from town when the Huns started coming, and crept back when the Huns had gone again. The man simply asked for it. Asked for it. He must die for Art! That was what it would amount to. His death would get a bit of good music printed and published. He would leave something to posterity after all.

He sat and tried to think about money. He was not good at it. He was too artistic, too creative, if you wanted to know. The mere thought of insurance made him shudder, but a chap had had to do something. Salary and commission, that’s what it had boiled down to. ‘Oh, I tootle round,’ was what he explained to friends. ‘See what I can pick up. What about you, old man? Your life insured? Why not come to my people?’ There wasn’t much in it. But it scraped up a living. Hardly enough to get tight on, though, let alone keep a wife. As for kids! ‘No, siree! No bally fear!’

In his new room at Number Forty, he thought:

‘If old Watson wrote out a policy saying that if he kicked the bucket he’d leave a couple of thousand quid to me, then it would be worth bumping him off. That’s the ticket, I think?’

Yes, but how to make him do that? Forgery? No, that wouldn’t be cricket, a chap wasn’t a criminal.

He thought:

‘A pot of paste. If I pasted the policy he thought he was signing—over the real one, allowing only the bottom for the signature? Then he’d sign the one that mattered to me, and a steaming kettle would do the rest. By jove, yes! Think it would work? Or would he spot it?’

He kicked off his shoes and lay down flat. ‘I wonder,’ he thought.

Mr Bowling’s background was in reality so little a background at all, that to paint one at all needs a cycloramic effect. It was a colourful fusion of people in shabby places. Had they homes, it would have been a Dickensian background; but these homes were, in the main, furnished, single rooms, occasional flats. Sir Hugh Walpole wrote of duchesses and balls and stately houses, of the hills and lakes of Cumberland. Mr Bowling had had relations with a substantial background once, but his story removed him from it as a child, and placed him, for want of a better description, with the Moderns, though not the Moderns who belonged to Noel Coward. They didn’t drink cocktails, they drank mild and bitter, or draught cider when really hard pressed, and fell about Hammersmith’s houses filled with it and Red Biddy. No mansion-flats for them, and less and less evening dress. They didn’t go to theatres. They went to pubs and concerts, dodged or seduced landladies, and remained the people who mattered when England went to war. They knew the Labour Exchange and the Army Medical Board better than most. They had no influence, no wires to pull, and told each other: ‘I hear they’re taking on men, four quid a week, dear. Why not pop along and see? I know it’s not you—but it’s better than this?’ You went along and the chap was decent, but he saw you were a gentleman and he was slightly embarrassed. He was afraid the work was dirty and rough. ‘No clerical jobs, you see, they’re all taken.’ They thought at the Labour Exchange that an actor, author or musician temporarily a bit desperate for cash, could only fit into clerical work, and there was none. ‘Would you drive a Sainsbury’s van?’ they sometimes asked. ‘But it’s hardly you, it is. I don’t suppose they’d take you on.’ You couldn’t even draw the dole, because you hadn’t been a salaried worker for at least six months. You had to queue up with the scum of the earth (which you never did) and be ‘on the Parish’. Very tasty. But how different when the same government who thus humiliated you decided to go to war! ‘Bloody heroes now,’ Mr Bowling laughed good-naturedly at Queenie about it. ‘Nothing too good for us now, what?’ He was perfectly good-tempered about it. In just the same way, when he had sent in his War Damage Claim, he realised with something of a latent shock that he had lost every one of his musical compositions, the accumulated work of years. ‘Why, there was a bally thing there I wrote at school, when I used to play the organ in chapel,’ he laughed sadly. ‘I’ve lost the lot … But, good Lor’, what value can I put on them? I never had them published, modern stuff and classical stuff. They’re worth only the paper they’re written on—for the Salvage Campaign! Look here,’ he decided whimsically, ‘I’ll make a present of my life work to my country, I’ll claim nothing. And if that isn’t patriotism, I dunno what is!’ He roared with good-natured laughter and the clerk seemed rather to admire him, he hadn’t liked the look of him at first, people rarely did.

‘Very well, sir,’ he said. ‘This is the lot, then.’

‘Yes. We only rented the house. I’ve got all I can think of in the list. Tots up to a jolly old four hundred and seventy-eight quid. And I’m not cheating you,’ he challenged.

He hadn’t cheated at all. He’d been warned all round: ‘They aren’t giving full value, you know. I should pile it up a bit. After all, remember you’ve got to wait till after the war—twenty years’ time!’

Roars of laughter.

When they wrote and asked him to accept two-thirds of his claim, he accepted at once, regardless of genuine loss, and also the loss of his music. Who cared? There was three hundred odd quid to look forward to after the bally old war, if we won, what, and if one lived through the night’s blitz. It was comfortable and one had never been fussy. Not for shillings and pence. It was the general idea of wide security, no more shabbiness, that was what one hungered for. A chap wanted something really substantial. No more of this bloody messing about. A really decent house, cottage perhaps, but in town, of course, you could have your huntin’, fishin’ and shootin’; a cottagey house in Knightsbridge or Belgravia, yes, Belgravia (what was left of it), or else a really decent flat. That was the ticket.

Lying flat on his divan, and plotting the demise of Mr Watson, he tried to work out how much money he must get before he could chuck the game. It was really easier to deal with one or two of his dear old lady clients, they were gullible and often fell for him, and they had pots of dough. But he was through with killing women. It had been frightful, one never thought of ugly detail. Watson was a bit of a sly customer, but that rather gave it a fillip and made it more sporting. To get him to sign the bally policy would be tricky enough, and then there was the office to think about. He would have to kill Watson the same day, or at any rate the next day, before the office could write and confirm things. And what were the office going to say? ‘You’re a lucky chap, aren’t you, Mr Bowling? Most astonishing bit of luck, what?’ Yes it wasn’t going to be too simple, was it. There were mugs about, but the office weren’t mugs, and Mr Watson wasn’t a mug. Had he had some gin, he would have thought queerly: ‘What does it matter, anyway? If I’m caught, I am! Who cares? … I’d rather like to be tried at the Old Bailey, honestly I would!’ He heard himself assuming gin and thinking this—and wondered why, and if he really meant it deep down. Men are queer things, he thought. He whispered it to the empty room. ‘Men are queer things.’ Then he whispered: ‘How much money shall I want, to make life real and worth while, to get stuff published, you can get these things done if you can dangle a bag of gold in the right quarters? How many must I kill?’ He was vague. He thought he’d better try and get hold of ten thousand pounds, but it sounded such a large sum, when you were more used to odd ten bob notes. Money bored him and never stayed in his mind for long. Detail bored him too. It ought to be easy for the police, he thought. If they can’t spot me, they’ll never spot anyone. He forgot about money and the details of Watson’s murder and suddenly thought: ‘By jove, can I remember all my compositions? What a sweat, writing them out again? I’m not as energetic as I was.’ Mr Bowling was thirty-seven. On the day he murdered Mr Watson in Fulham, he was thirty-eight. At Queenie’s that same night, when she asked him what sort of a birthday he had had, he roared with laughter. But she commented that his hands were clammy.

His hands went clammy when anything really moved or excited him; it was nothing. Nerves, you called it. On his wedding day they’d been clammy, and on his first day at his public school. When his father had died, a week before that fourteenth birthday, his hands had turned clammy while he thought how unfortunate it was, now he was stuck with his stepmother, who loathed him. There were two kinds of stepmothers—which people tended to forget—the brilliantly successful, and the sadistically cruel. She was one of the latter, or he would not have criticised her for loathing him. Well, they loathed each other, there was a polite and very strained tolerance. His father had been vague as his son still was, and had left no will, so stepmother collared everything. She was a woman of ‘ideas,’ so she let him carry on with the public school education, but she packed him off to live permanently with a relative who had a house where the school was. She wasn’t a bad old girl and was fond of the bottle. He infinitely preferred it to being with his stepmother. A severe and rather cruel snag was the enforced severance from his sister, they were genuinely fond of each other, and she was the only real affection in his life then or now. She ran away from home, married and died in childbirth, but she was as real to him now as if she was still bobbing about in the sordid world, especially when he had a go at the Moonlight Sonata. She’d stand by the piano, nearly enough, and he’d smile sadly at her and talk to her. Anyone coming in thought he was nuts. At school they thought he was nuts, he would do mad things, it was really in order to try and become popular, he had what was called an inferiority complex, a silly but useful phrase meaning he’d been kicked around as a child, mentally or physically, and hadn’t found his feet yet; perhaps he wouldn’t find his feet until he was forty or so, or at all, a chap like that naturally needed help. He needed love. It was no good sneering at it, it just showed your bally ignorance. Well, which was worse, to have that, or to have a superiority complex? The first suited creative art quite well—you could work ferociously in the dark, without an audience and in time maybe get away with it, emerging to find your complex gone; the second suited actors and politicians, you needed all the ego and conceit you could manage—and Heaven help you if you couldn’t get away with it then. At school he would do whatever the other chaps dared him, like climbing up the tower, or creeping past the Housemaster’s bedroom to tap on the servant’s door and moan: ‘Whoooooo!’ like a ghost. When she screamed, and he got caught and flogged, he showed his marks proudly and roared with laughter. He had rather a big head, like a tadpole, and rather a pink face. The other chaps admired him, in a way, he had guts, was generous when he had anything to be generous with, but they didn’t ‘like’ him. He didn’t make a friend. He was mostly to be seen sitting over a magazine, beaming round hopefully to see if he was in favour today or not. He was hopeless at maths, good at French, plucky at boxing and swimming and P.T., a good long-distance runner, and oddly religious. His music master took a fancy to him, but it was difficult because the old chap had peculiar pawing habits with boys. It was dangerous to be up there with the bellows. ‘Bowling,’ he liked saying, ‘you’re a nice boy, I like you. You should learn to play the organ.’ This he did, with easy agility, and giggling with laughter when he was kissed and fondled, it was all so silly. He composed an organ solo which was performed on Speech Day, a huge moment in his life. He beamed round at everyone that day with much success, and he heard Colton Major, a scraggy youth he had always hated, saying to his mother:

‘That’s Bowling, he wrote it, I was telling you, mater! He’s really rather decent!’

Later, in fun, he got hold of scraggy Colton in the bushes and put a hand behind his neck and turned his scraggy frame round. It was easy. He put his hand over Colton’s mouth, and rather close to his nose, and it was amusing to hear Colton’s smothered screams. They were more like squeals. His face turned a dusky red, and then very slightly black. He thought he’d better let go.

Colton stood panting and gasping for breath.

‘You are a … swine, Bowling,’ he panted.

‘I suppose I am.’

‘… Why did you do that?’

‘I dunno. Because we’re leaving this term! Some such vague reason!’

‘You are a queer fellow. I think you’re a cad. You might have killed a man.’

‘What of it?’

‘It would have been murder.’

‘Well, there’s worse things than murder, Colton? Cheating. And running down a man’s parents. Things like that.’

‘I shan’t speak to you again,’ Colton panted and decided. ‘For the rest of our time here.’

Bowling roared with laughter.

In bed that night he was in the dock. He was smiling confidently and the jury were looking at him, all thinking:

‘He’s not guilty. Can’t you see—he’s a gentleman.’

The judge liked him too.

But the evidence went against him, and although he and the judge had gone to the same school (he was Mr Justice Colton), he put on the Black Cap and sentenced him to be hanged by the neck. It didn’t matter much, everyone knew he was not the usual criminal type, and when the last hours came and there was no reprieve there was still Angel to come and say goodbye to him, for she loved him.

Angel had lovely fair hair and warm ways with her. She was too lovely to be touched, even if you married her. You just sat at her feet, and only just dared to stroke her like a cat.

CHAPTER III (#ulink_6cbdf4b6-f83b-5179-989a-e94d4e853acd)

ANGEL went to the high school up the road. The boys got speaking to her over the wall. She had long golden hair and a lacrosse stick and a blue gym dress. One day Bowling trailed her all the way home, but she was too wonderful to talk to, he was too frightened, it was much safer to talk to God. So he trailed the two miles back and went into the chapel and prayed. He was afraid to pray in the proper pew, in case any of the chaps thought him a goody-goody, so he went up to the organ-loft and pretended he was about to play the organ—which he could not do in any case unless somebody worked the bellows. He felt God was real, an actual person, and that He was sorry for having to make people come down here for seventy years or so—less if you deserved it—as a sort of obscure punishment. Bowling could never see that death was a hard thing, despite all the beauties and happinesses which were to be found here; how could it be anything but a real ease from hard labour and worry, with our wars and our struggles? Yet there were people afraid of it. He honestly was not afraid of it, and he saw some vast scheme behind it all, which our inadequate mentalities were unfitted to imagine. There was some very good reason for suffering and hardship, we should probably never know what it was, we were perhaps not meant to. We just had to get along as we thought best, and try not to feel too tired after a bit. He early saw that love was the thing, marriage the nearest approach to happiness while we were here. He modelled this idea on Angel, the little girl over the wall. Up in the chapel he felt glad he had never thought or said coarse things about her, like the other chaps did, and he prayed to have somebody like that for himself. He was hungry for love, spiritual love, and loving God didn’t seem quite adequate, you wanted long, feminine, golden hair to stroke. He hadn’t even had a mother to love. She had quickly died. ‘At the sight of you, I expect,’ his stepmother had jested, a jest which hurt, as it was meant to. He grew up worried about his looks, trying to think he looked all right. He was afraid: ‘Nobody will love me, I’m afraid!’ That was why he smiled and laughed such a lot; hoping people would think he was nice.

‘Hallo,’ he always said, smiling broadly. He rubbed his hands together slowly. ‘Nice to see you! By jove, what?’

People were either embarrassed, or bored.

‘O, good morning, Mr Bowling. How are you?’

Not: ‘How are you?’

Except Queenie. She was different.

Queenie hated prudes. She’s had lots of men, and was even courageous about the colour bar. She’d give you Hell if you started up that topic. She said it was just as bad as the Nazis’ race creed. Humanity was the thing, we were all flesh and blood, and either our flesh and blood was feeling pretty good, or it was feeling pretty bad, and if the latter you should do something about it for folks. She got stranded for cash when she was in her ’teens and answered a friendship advertisement. ‘And I’ve been friendly ever since,’ she challenged. ‘So what?’ She liked to wink. ‘Finally I ran into a bit of regular money and married it. So what? My heart’s in the right place?’

He didn’t bump into Queenie and her crowd until he was about thirty. He’d had a pretty sordid time until then. He left public school with literally nothing. The Great War—so called—was over, and now it was the bitter, workless peace.

Work? There was no work. Unless you were a factory hand, or a grocer, or a machine tool maker.

The only faint possibility for a gentleman was a frightful thing called Salesmanship.

When he was desperate, he got on to this. Writing music? ‘Don’t make me laugh,’ he said to everyone. ‘It’s who you know—not what you know.’ He was a fairly good pianist, but he went to agents in vain. As for selling anything!

‘This won’t do,’ he thought, shabby and hungry. ‘Is this all my education means?’

He wished he’d been apprenticed to a garage all those school years. Mending punctures and things.

He had a peep down the Morning Post. There was nothing. Yes, there was, there was Salesmanship. Vacuum cleaners. Trade journals. Itinerary for housewives. Doors slammed in your face, Margate, Sheffield, Maidstone and Tunbridge Wells. You could have it. There was no food in it, no clothes, no beer, no fags, no pictures, no women.

Life was complete Hell. Only those who had been through it knew what complete Hell on earth it really was, to an educated man with a sense of humour, a sense of patience, and a sense of God—which meant a sense of courage. And an artistic man, at that, whose mind and heart responded to the hidden chords of good music.

He would lie on his back on shabby divans and think about it. He’d try to laugh.

‘It’s no bally good giving in, you know? No blessed good at all, don’t you know! What?’

He first met Queenie in a pub. It was the Plumber’s Arms off Ebury Street. She wasn’t married then, she was friendly. He only had fourpence, what was the good of keeping it? He’d just tumbled on to the insurance racket, commission only, and maybe things would soon brighten up a bit. He digged up the road a bit, a bed-and-breakfast place, where he owed five weeks’ rent, but the old girl saw he was a gentleman and honest and down on his luck. She said openly she liked his smile and his laugh. Still, things couldn’t go on like this, you know, what? He saw Queenie looking at him and smiling. He smiled too, but regretted she would be unlucky if she wanted a drink. She was a bit blowsy, but she had a nice face and a smooth skin. She used the usual technique and said hadn’t she seen him somewhere before? He said the usual, yes, where was it now, but hastily adding he was flat broke, he was terribly sorry. ‘That’s all right, my dear,’ she said at once, ‘you must have one with me. Double Haig?’

‘I say, doubles, eh?’ he queried, wishing she’d buy a double sandwich instead.

‘Why not?’ she said sympathetically.

He saw her give his clothes a polite once-over.

‘Married?’ she said.

‘Yep,’ he said.

They got talking. With some people it was easy as winking. He told her about his marriage, how he’d cleared out, and how he already felt beaten and ready to go back.

‘I miss my piano. And the carpet,’ he laughed.

‘Where?’

‘Oh, Fulham.’

‘Poor old you.’

‘It’s hers, you see. Nearly everything. It was her money when we got married, that was my big mistake. She’s a lady, but she’s odd. Oh, I dunno. I was only twenty-one.’

‘Oh!’

‘She’s a bit older than me, quite a bit. Her parents cut her off, didn’t like me. She drags it up. I’m never allowed to forget. She goes on and on. Year after year, you know. I dunno, at last I blew right up in the air. You have to, sooner or later, don’t you?’

He laughed.

‘Let’s have another,’ she said.

He laughed again. Very ashamed, he went pink and said, ‘My dear, quite honestly, will you buy me a sandwich?’

She got half a whisky bottle, a couple of quarts of Bass, some fags, a cigar and marched him out.

‘There’s food at home. Come along.’

‘You’re a darling. This is ripping. Oh, my God, I feel a complete cad.’

‘You dry up.’

‘You’re a perfect pet.’

‘It’s in here …’

‘I wish there’d be a bally war or something, what?’

He laughed and she laughed and they stumbled up the narrow stairs to the top floor. It was rather theatreish, the hangings were like red plush. There was a not unpleasant suggestion of onions. There were two rooms, overcrowded with furniture and clothes chucked about, and the bath was in the kitchen with a board on it, the board crowded with vegetables and things. She showed the geyser, saying she’d given it a proper old polish this morning, and he could have a bath later on, just as he liked. She slipped into a white dressing gown affair and he sat smoking while she shoved something in the oven. When she finished that he gave her a kiss and they stood smiling at each other, she standing, he sitting on the edge of the bath, sort of amused, rueful expressions saying: ‘This old world, what can you do with it, short of making a complete hash of it?’ When he’d eaten they got talking about prudery and hypocrites, and discussing what the devil sin really was, where it began and where it ended, and what morals really were, poor old Hatry got landed, while old So and So, a complete rogue if ever there was one, remained M.P. for West Ditherminster, with packets of dough in armaments. Then they got down to whether, once agreed what sin was, you got punished for it on this earth—or later. It was very absorbing, and had always fascinated him very particularly; but Queenie dropped asleep on the sofa with his arm round her warm, plump body, and as she didn’t believe in God it was unlikely they would ever reach a conclusion. Being strong as a lion, despite all the undernourishment he had gone through, he carted her into bed and got himself undressed. The effort upset him strangely, but she was dead out, so he knelt by the bed and stared at her, quaintly saying the Lord’s Prayer out loud. The stuff she put on her hair was a bit faded at the roots, but she looked fair and he thought of Angel again. When he got into bed, she didn’t leave much room, and he had to get out to go and switch off the light. After that, he had to get out again twice in the night, forgetting the light both times, so the night was like a kind of steeple chase, treading over Queenie’s plump body, and trying not to kneel on her stomach in the dark. He made love to her in the morning when she woke up, a sudden impulse it was, and an impatient one, and afterwards he felt a bit worried. But she said:

‘My dear boy, don’t you worry about me!’

At breakfast, she used common sense.

‘Be a sensible boy and go back home. You can stick it, my dear. It’s better than this? Come over and see me whenever you get too fed up. Will you?’

He told her earnestly that he would never have been unfaithful to his wife if only she’d played the game.

‘I can assure you I’m being eminently fair,’ he told her. ‘I can assure you I never thought there could be anything worse than an unfaithful wife, Queenie. But there is.’

‘Never mind,’ she said. ‘The Hell you know’s never so bad as the Hell you don’t know. That’s a true enough saying. Be a good boy and go back. Or I shall worry.’

‘It’s immoral to live with a woman you don’t love.’

‘But you don’t make love to her, do you? Be like neighbours! Friendly enemies!’

And they laughed again.

Later in the morning, he took the tube and went home. But there was a strange new happiness in his heart, the feeling of having both found love and made a friend. He already felt it so strongly that he wanted to divorce Ivy and marry Queenie. He was far from sure that Queenie was the kind for marriage, and in any case she had told him she would marry for security when she got the chance, and for nothing else, she would be insane not to. But he had been so happy with her, he was vain enough to think he could break this down. His feelings about it were strong, although he had got over it by evening, when he realised she was not a lady. This was a practical thought, not a snobbish one, it was whether a gentleman could live happily married to somebody a bit different. Ivy was a lady, and look what that meant?

What a mess it all was.

He let himself in.

She was there, as he knew jolly well she would be there, and she behaved in the way he jolly well knew she would behave; she said and did simply nothing at all: she just sat around with that particular expression on her face.

Her face was pinched and had always been a bit sallow, a sort of brown that was not sunburn. There was that about her which made the name Ivy seem dry and hard and right. Her hair was black and dry. She was thirty-eight at that time, his present age, and she looked more than that. Poor old Ivy. It wasn’t her fault, any more than anything was anyone else’s fault. And she was every bit as unhappy. Hardly any friends, only a few callers, and cut off from her parents. It was bad luck. But they were long past the stage of trying to console one another, it had all been run through before, and was threadbare. There were deep wounds, and any words now only lead to louder words, and which made for nothing. He just let himself in, and there she was, and she sat and sewed and he wandered about. He finished up at the piano. About late evening they would have a fine old bust up, he’d have to say about the money owed to the landlady, and she’d have to fork it out; then she’d say the old one about how she always thought he was going to do such wonders with his music, and he’d trot out about how a woman ought to be an inspiration to a man, and not a hindrance. And all the rest of it. Then he’d trot out the divorce topic again, and get the usual defiant No. She challenged his religion with it, ‘I thought you said you were religious?’ and that was always that. Whom God hath joined together, let no man put asunder. ‘We were married in church, weren’t we?’

‘Yes, Ivy. But the marriage has never been consummated, has it? And do you know that even the Pope is impressed by that?’

‘Well,’ she said then in her quiet voice, ‘why don’t you do something about it, then?’

‘No money.’

‘What about the Poor People’s Act?’

‘Now, Ivy, you know quite well I’ve applied. They refused my application.’

‘There you are, then.’

‘Now, Ivy, I have it on good authority they only accept a small percentage of applications, they get so many. It does not mean I have not got a case.’

Her expression continued the dialogue, triumphantly, without the need of words. He thought her cruel about it, and he was not cruel himself, always wondering what would happen to her if he did get a bit of cash together, and divorced her. Where would she go?

On this occasion, the bust up was much as usual. There were no tears, it was past that. She’d known he would come back with his tail between his legs, she supposed he was starving, she supposed he’d been sleeping with other women.

Then she slammed the door and went to bed with her Bible.

He hadn’t any money to get tight with, so he played the piano furiously for an hour, and then slammed a door himself and went to bed, not with the Bible, but with a box of matches and twenty Gold Flake. In earlier days, there would have been tears from the next room. He’d have gone in.

‘Now, Ivy, this won’t do, my dear child. Can’t we straighten this thing out?’

But there was nothing to straighten out. She just wasn’t meant for men.

When he first met her—and they only met at all by the merest chance, a tragedy in itself—she’d looked so kind and well-bred and quiet, he’d fallen for her at once. ‘That’s the girl for me.’ Her smile was a tiny bit pinched, and her lips inordinately thin, with a dark down on top, but her eyes were straight and bright, they were dark blue. It wasn’t Angel, but it was perhaps Angel with dark hair. He’d been taken to a musical show by the aunt he stayed with during his school days, not many months before the old girl died. She was to meet a friend at the theatre, and when they got there this friend had just bumped into a Mr and Mrs Faggot, and their daughter. ‘This is our daughter—Ivy.’ They’d made a party of it, getting the seats changed at the box office so they could all sit together. And if they hadn’t just chanced to see the Faggots, he would never have seen Ivy. But there, wasn’t history made up of these ifs? He and Ivy seemed to have got on fine. He hadn’t fancied the old birds much, but you couldn’t get on with everyone. ‘No, I’ve got musical ambitions, really,’ he confided in Ivy in the interval. ‘Not this kind of thing, I’m afraid. The more’s the pity. There’s money in it.’

‘Classical?’ she asked, sounding interested.

‘Well, yes. I’m not saying I spurn the other. That will sound young. But I want to write. And play, too, of course.’

‘The violin?’

‘No. Piano.’

They went to several concerts, and one summer night at the back of the Albert Hall he discovered she’d never been kissed. She was rather shocked at being set upon in the street, so to speak, but he laughed.

‘You mustn’t mind, Ivy. What other chance do I get? Your people watch me like a pair of hawks, I’m afraid they don’t approve of me at all.’

‘Yes, they do,’ she lied.

‘Well, won’t you kiss me? I mean, there’s nobody about?’

‘Don’t be so common, William. I know you aren’t common, but we oughtn’t to behave like servants.’

He laughed.

‘Why not? If we don’t feel like servants?’

Their very first row was when he slapped her bottom good-humouredly, never a habit of his with ladies, but solely in an effort to make her a bit more human. To his astonishment, she turned pale with anger and humiliation and fainted. When she came round, he couldn’t help laughing because, if she wanted the truth, she never let him touch her anywhere else. He laughed and told her.

The first shock of realising she literally knew nothing, was a pretty stiff one. Victorian novels and all that, he thought. And he thought of her stiff and starchy and exceedingly stupid old mother, and felt no longer surprised, only angry. Poor kid.

‘Look,’ he sat on the bed and said, ‘Don’t you worry, old dear? I’m not a lout, I’d simply no idea, honestly.’

He could see she believed him, but she was too embarrassed to do anything other than huddle in the hotel sheets, like a wan and rather too old fairy who has just been assaulted by a hitherto virtuous gnome. ‘Look, Ivy, we’ll just talk. Or, shall I clear out? Whatever you say, my pet? I’ll dress again and go for a bit of a tootle by the sea, what?’ They were at St Leonards, of all Godforsaken places, The Hotel Criole, a fearful affair up the hill. Her mother had known of it, needless to say, and practically insisted. The old crab. But he’d laughed—you knew what that kind of woman was. ‘Whatever you say, Mrs Faggot!’

‘It is what my daughter says, I should hope,’ the silly cow said. My word, to think that kind of person lived safely through her seventy years and then died comfortably in her bed.

But he laughed.

‘Hastings,’ Ivy confirmed, so Hastings it was, at least, they seemed to call it St Leonards down there, though it looked all one to most people.

It was a bit of a job explaining to Ivy, in one’s best public school manner, where babies came from. She seemed to know, and yet she didn’t. She vowed she did know. ‘Of course I do, Bill, but …!’

‘But what, my dear child?’ he smiled. ‘Silly old thing!’

She sniffed and sobbed.

‘Never mind. Don’t even think about it,’ he said kindly, he went out of his way to be kind and considerate for months and months. ‘It’s quite unimportant,’ he pretended.

When he decided it was time to stop pretending, they were in the half-house in Blythe Road, Fulham, a basement, ground floor, first floor affair, some other family living upstairs. The marriage was already gravely threatened; quarrels, hair falling out in the bath, and other nervous disorders too despairing to mention, he thought. It dawned on him that he ought to have seen Doctor Elliot about her ages ago, though Dr Elliot was usually too fuddled to be seen about anything except elbowitis. But he tootled along and tackled him in the saloon. ‘Look,’ he said, ‘confidentially, old man, I want to talk to you about the wife. She’s driving me balmy.’ He laughed, being slightly embarrassed, but old Elliot wouldn’t send a bill in, this interview would only cost a pint of bitter, eightpence.

He returned home quite jubilant, and although they’d had a bit of an Upandowner in the early afternoon, he was very kind and considerate.

‘Ivy, my dear,’ he said gently, sitting beside her. ‘I’ve got this for you. I think we might save our marriage even yet.’ He gave her the admission card Elliot had given him, to a local hospital. ‘Will you go? You will, won’t you? It’s your duty, surely, isn’t it?’

She gave one look at the card, coloured, swung round and gave him a fearful welt round the face.

He got straight up and walked out of the house.

His face was hot one side, cold the other. His heart was icy cold all over, all round inside and out. Bloody Hell! Women. Well, well! there was something to be said for homosexuality after all. He was through with women. Through with them? He’d never started with them. Merely married one of them, one who wouldn’t even go to a hospital and be examined, perhaps have a small bit of an operation. This was the end.

He strode about Kensington Gardens, not knowing how he had got there, but realising slowly he hadn’t the fare back and must walk, in shoes which let the snow through.

The park looked sad and nice. It was white, the trees were stark and white, and the people like cold, uncertain shadows, moving about the ice of the Round Pond.

The sun was blurred red and shapeless up there in the grey-black of more snow to come, it looked like a half-healed wound.

When he got back, his feet were wet and cold and he was worn out. He was too tired to say any of the things he had decided to say. What was the use of saying he was going to leave her? Where would he go? Where would she go?

And what would God say about his obligations?

What God might not say about hers, were not his affair. He was full of self betterment, and spiritual theories, and liked to feel that marriage led two people towards a goal.

What could he feel now?

She sewed and she said:

‘I’m sorry I lost my temper. I ought not to have done that. I apologise.’

This time it was he who sat and said nothing.

She said:

‘You must realise, William, a woman is different, physically, mentally, and spiritually, from a man.’

‘I do begin to realise it,’ he said quietly.

CHAPTER IV (#ulink_25b2e4c8-2891-56f3-addf-f5d786947f92)

THERE was a fearful shindy the first time it came out that he had made love, as she called it, to a girl who came in to dust up the old homestead. She was a naughty little thing, and he found her methods irresistible. In vain did he tell himself he was not playing cricket, and he loyally refused to allow himself to think: ‘It’s entirely Ivy’s fault.’ It wasn’t. It was his fault, and it was Elsie’s fault. Elsie was sixteen and her trouble was she had elder brothers. She kept getting in his way in the passage, and smiling up at him and going red. She had a floppy little body which it was impossible to ignore. When Ivy cleared out Up West one winter afternoon, he went up to Elsie, who beamed round and upwards, and, as she put it later, ‘Let him take a liberty with me, but I didn’t mind, at least Mr Bowling is a gentleman.’ On the bed, there was no difficulty about clothes, because the wretched child didn’t seem to go in for them. She had soft lips and elegant teeth and Cleopatra appeared to have nothing on her. And although he condemned himself for a cad, and thought about the old school and all that sort of thing, he repeated the performance at teatime, and many teatimes afterwards. It was a bit of a strain, craning the neck up at the basement window, to see if old Ivy was coming up the road yet. And needless to say the poor child clicked, as she called it, dead on the three months to the minute. This at least threw off a certain amount of reserve, and they went at their love affair hammer and tongs while the going was good. His health at once recovered, he liked women again, thought about Angel, and even contemplated marriage with dirty little Elsie. This didn’t last long, however, and he started in at insurance with new zest, now and again varying it by crowd work at Elstree, whence his accent very occasionally got him a line to say, or his dinner jacket got him a sitting part in a cabaret scene. Then he came home one day and heard, smelt and saw the fat sizzling in the fire. He couldn’t resist:

‘Well, my dear Ivy, you’ve asked for it, you know, I must say!’

Needless to say, she said:

‘How like a man! You’re a cad and a brute, and I hope you go to prison!’

‘Prison?’ he said, startled, and had quite a turn when it became apparent Elsie had lied about her age, and was really only a pullet-like fifteen, or had been ‘at the time of the alleged incident’. This was going back a bit, and he did some anxious arithmetic. Elsie stood about, sniffing and sobbing, and looking more like a slut than she ever had before, as if to increase his shame, and he thought: ‘Well, now perhaps I’ve achieved a divorce, which will be something!’ But not a bit of it. There was to be no freedom, and the threat of prison hovered for some time, together with the unpleasing rumour that Elsie’s dad, from the docks, was coming along presently to tear his block off. Unnerved by the general prospect, he hurried along to Queenie, confessed all, and was well ticked off for his lack of caution. However, it was worth it, for she took on her shoulders the entire matter, going to fix up for Elsie where she was to have the baby, firmly insisting that she got it adopted immediately afterwards, and the outlook began to look a little safer. Life with Ivy was then grim indeed. She threw it up at him for each meal, and she threw his music up at him, ‘not that you do any,’ and she threw money items up at him, ‘not that you earn any.’ They had frenzied scenes, and slammed doors at each other, and hated the very sight and thought of each other. Sometimes he went to the piano in a state of exhaustion, and composed a sad little tune which he knew was rather good. But when he saw music publishers about it, they just smoked cigars at him, said nice things, but were clearly thinking about something totally different. One winter he got a nice little job playing in a concert party at Eastbourne, but something or other happened, a quarrel or something, and he was soon back picking up the crumbs from insurance magnates’ tables.

‘I dunno, I’m sure,’ was what he thought about life. And he laughed helplessly. ‘I dunno, I’ll tootle along and see old Queenie. See if she’s really going to be married.’

Having had a good time with old Queenie, and learned that she was going to marry a crashing bore because he had a fiver coming in certain, apart from his job, he went out with the quid she pressed down his shirt, and had a couple at Victoria Station. He returned home to Ivy and silence, read a bit of If Winter Comes, the only book in the place, and chain-smoked in bed with it.

Life crept by, Ivy got older, he felt now older, now younger, and wondered what on earth the whole thing was about. Why be born a gentleman if you weren’t allowed to live like one? It was the most frightful punishment in the world.

He felt this most when he had to visit the office. He always sensed that it was resented. When he finally got on the salary list up at the office, he felt his particular department resented that too. Apart from the manager, who was usually too important to be talked to, there were only two blokes who concerned his little affairs at all, Mr Nash and Mr Rosin. They were two beauties. They both had hilariously witty things to say about his old school tie, and about Lord Baldwin and Mr Chamberlain. The things they had to say somehow seemed to appear to be Mr Bowling’s fault. Mr Nash was thin and sour, and Mr Rosin had a flat, stupid face like an uncut cheese. The really common man, Mr Bowling decided, was a nice chap, but these two belonged to the half-and-half species; they were really sprung from the common man but they thought they were old school tie whilst resenting that sorry class. They loved it when a public school man got sent to gaol, and took care to cut the bits of news out of their paper for when he next came in. ‘There you are, Mr Bowling,’ they pushed it forward, winking at each other, ‘there’s your old school tie for you. H’r! H’r!’ too stupid to realise that at any moment he could cut out a bit of news about Winston Churchill and say, ‘And there you are, Mr Rosin, and Mr Nash, there’s another of your old school ties for you! H’r H’r?’ But a chap wouldn’t stoop to it.

Coming in to collect the thousand quid, Messrs Rosin and Nash had appeared very different, almost admiring.

Such was the pitiful power of filthy lucre.

‘Money, money,’ he sighed time and again. You just could not ignore that miserable subject.

It was tough if a chap was bad at it.

He liked to ponder upon the illogical, in respect of money. You got paid for doing what was called ‘a job,’ but which was often and often nothing but sitting around. But for real hard work, like thinking out and writing something, more often than not you got Sweet Fanny Adams.

And they said when you had got money, you thought about it even more—in case you should lose it.

It was true of Mr Watson, at any rate.

The day he murdered Mr Watson, he got up early. Thinking about it had deprived him of a good deal of sleep, yet he felt a kind of exhilaration. He’d pasted the policy carefully on top of the other one, and it didn’t look too bad. There was the ridge at the bottom, of course, which old Watson would at once spot, but he’d explain to him: ‘Paper economy, old chap, if you don’t mind?’ and Mr Watson wouldn’t mind, because he liked to try and give the impression that he was doing something for the war effort, it was so obvious he was doing nothing. ‘All right,’ he’d say. If he didn’t, the deal was off. Something else would have to be thought out.

At breakfast, Mr Bowling felt a bit restive. He was a man of leisure, these days. He’d eaten into his thousand quid a bit, nothing much, but a bit, it was so nice being able to give old Queenie bits and pieces, after all her kindnesses when he was down. He gave her a nice bit of cat, thirty quid it cost, and she was so pleased. She kissed him and he laughed: ‘Just a bit of cat!’

‘And you be careful who you marry next time, my dear,’ she told him. ‘Come and see me first!’

And he’d thrown a bit of a party, here at Number Forty, yes, with the bombs still whistling down, you only died once, didn’t you. There was a din, and he played the piano and they sang, and the chap came down from upstairs to complain. He played about with chemistry or something of the kind, he’d been to Oxford and he was interested in Mr Bowling. He was a bit of a bore, that first day stopping him in the hall downstairs.

‘My name’s Winthrop. Alexandra Winthrop. I hear you’re joining us.’

‘Yes. Bowling’s the name.’

‘Miss Brown was telling me, Mr Bowling. I hear you were blitzed. Bad luck! Yes, she told me about it. I’m very sorry.’

‘Oh, well.’

‘You mustn’t be lonely. I’ll pop in, may I? And you must pop up.’ He frowned. ‘Usually busy. Eton?’ he guessed.

‘No.’

‘Ah. H’m. Well, I shall hope to see you. Bath water’s always hot,’ Mr Winthrop informed, and went out with a friendly nod.

Mr Bowling went up to his room. He didn’t want to know any of these people. Winthrop already seemed to know about Ivy having been killed.

He frowned and shut the door, wondering who else lived in the place.

With the plans forming in his mind, he preferred solitude.

On the day of Watson’s murder, Winthrop knocked at the door and came in without waiting. He smoked his pipe and wore a Norfolk jacket.

‘Ah. H’m. ’Morning, Bowling?’

Mr Winthrop was just a lonely and middle-aged man. And he was a bit inquisitive.

He chattered and peered about. He was already insured, so he was sheer waste of time. He gave peeping looks all over the shop. He chattered about the furnishings here being better than most places of the kind, said Miss Brown was a dear, ‘she’s a lady, you know,’ and remarked that Mr Bowling seemed to have made a lot of purchases, suits and shirts, and said he believed there would very shortly be coupons for clothes. He said it must be awful to lose your things, and he said the various things he thought about the Ambulance Service, the Home Guard, the Fire Service, and the F.A.P. He swayed to and fro on little brown shoes, but looking overweighted with fat. His face was round and his mouth disgruntled. He was a flabby man. He said all about the people who came to live in the house, they changed weekly sometimes, but that Miss Brown preferred people to stay, providing they were, ‘gentlemen like ourselves’. He dragged Mr Bowling up to his ‘den’, which appeared to be a square room with a wide view of blitzed London, and crammed with wires and cables and acid bottles and chemistry books. When he got out at last, it was eleven o’clock, and the strain of being civil to Mr Winthrop had made him nervy. With his policies, he went along by bus to Fulham, for his interview with Mr Watson. On the bus, he thought: ‘Is this I who am doing this? Am I really going to do this?’ It was certainly quite a nice bright morning for a murder.

He no longer thought he was going to do it at all.

He’d just go along.

‘Good morning, old man?’ he hailed Mr Watson as he went up the little tiled path. Old Watson was in his doorway looking up at the sky. He was looking singularly well and alive. His grey moustache was very neat and trim, as if he was back from the barber’s.

‘Oh,’ he said, ‘good! How are you, Mr Bowling? Haven’t seen you for some time. Sorry to hear about your little affair.’

‘Oh, well …’

Mr Watson had a habit of chewing some real or imaginary morsel, as if the last meal had been singularly pleasant and recent. His eyes gleamed, while he did it.

He kept his caller in the little porch for a time, talking about various things, how he didn’t like the Welsh, and how he didn’t really like the English much either, and then jumping from that in a mentally restless manner, to geraniums. He pointed at various green plants in boxes, as if Mr Bowling was sure to be fond of flowers, never mind whether they were in flower or not.

Mr Bowling kept going.

‘By jove, really, how interesting,’ when being told about various bugs which ate leaves and so on. ‘Well, I’m blowed, what?’

‘I spray them,’ Mr Watson went on, endlessly.

Mr Bowling was wondering whether Mr Watson’s teeth would be likely to fall out, they might get to the back of his throat, and choke up the epiglottis. It might not look like murder, then.

The conversation veered round towards the blitz again.

‘Yes,’ Mr Watson said, ‘I was very shocked indeed to hear about your poor wife.’

‘Oh, well …’

‘I know what it’s like. I lost my wife suddenly one Saturday afternoon,’ he said, rather as if he’d taken her shopping, and it had happened that way.

‘Really?’

‘A bus …’

‘I say! I’m sorry, a beastly thing, that!’

‘But these things happen! Sad! Sad! But we’ve all got to go sometime.’

‘That’s true enough.’

‘Well, now, come into the dining room. There are various things to go into. And I expect you want my signature.’

They went into the dining room. It was very neat, and there was a picture of Mr Watson’s married daughter sitting in a deck chair at Margate and showing the most hideous legs. She really looked a corker. There was a plant in the firegrate, and on the table were Mr Watson’s pens and bits of blotting, all very fussy and neat, everything at right angles to everything else. He was like an old hen with his things. He sat busily down in his salt-and-pepper suit and started frowning about his money and his policies and his views on the Stock Exchange in general. The moment he saw the policy Mr Bowling had planned to try and get him to sign, he seized it in his bony fingers and stared.

Mr Bowling got to his left side, a little behind him.

‘Whatever’s this?’ Mr Watson exclaimed. ‘This won’t do at all,’ he said, and suddenly tore it up into little pieces.

He turned round towards Mr Bowling as if for another form, and Mr Bowling put his thick hand out. He suddenly and rather thoughtfully put his hand on Mr Watson’s moustache, and pressed Mr Watson’s head back so that it rested on his own chest, and the chair tilted and came back, and he quite easily dragged Mr Watson backwards out of sight of the little bay window. He felt the back of his legs touching the red plush settee, and he allowed himself to say quietly: ‘Take it easily, then it won’t take at all long,’ to Mr Watson, whose expression, if it was possible to judge it, was that of a startled child being forced to play a game he had never played before, and didn’t really like.