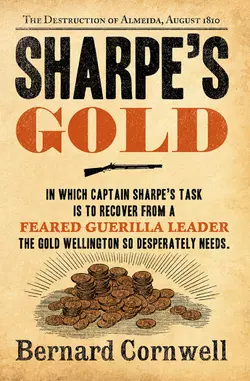

Sharpe’s Gold: The Destruction of Almeida, August 1810

Bernard Cornwell

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 2073.62 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Captain Sharpe’s task is to recover from a feared guerilla leader the gold Wellington so desperately needs.The enemy he faces strikes terror into the hearts of all around –a renegade guerilla band whose leader has a particular loathing for Sharpe who has stolen his woman.Soldier, hero, rogue – Sharpe is the man you always want on your side. Born in poverty, he joined the army to escape jail and climbed the ranks by sheer brutal courage. He knows no other family than the regiment of the 95th Rifles whose green jacket he proudly wears.