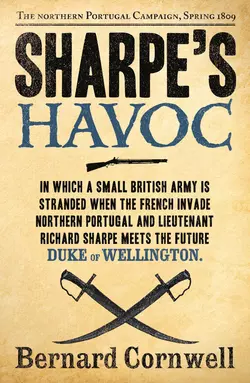

Sharpe’s Havoc: The Northern Portugal Campaign, Spring 1809

Bernard Cornwell

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 920.59 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: A small British army is stranded when the French invade northern Portugal and Lieutenant Richard Sharpe meets the future Duke of Wellington.Sharpe is stranded behind enemy lines, but he has Patrick Harper, his riflemen and he has the assistance of a young, idealistic Portuguese officer.When he is joined by the future Duke of Wellington they immediately mount a counter-attack and Sharpe, having been the hunted, becomes the hunter once more. Amidst the wreckage of a defeated army, in the storm lashed hills of the Portuguese frontier, Sharpe takes his revenge.Soldier, hero, rogue – Sharpe is the man you always want on your side. Born in poverty, he joined the army to escape jail and climbed the ranks by sheer brutal courage. He knows no other family than the regiment of the 95th Rifles whose green jacket he proudly wears.