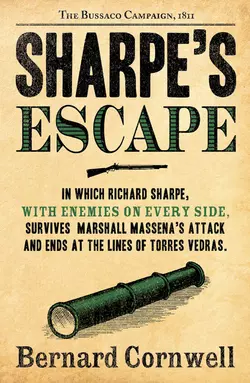

Sharpe’s Escape: The Bussaco Campaign, 1810

Bernard Cornwell

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 1536.15 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Richard Sharpe, with enemies on every side, survives Marshall Massena’s attack and ends at the lines of Torres Vedras.Sharpe’s job as Captain of the Light Company is under threat and he has made a new enemy, a Portuguese criminal known as Ferragus. Discarded by his regiment, Sharpe wages a private war against Ferragus – a war fought through the burning, pillaged streets of Coimbra, Portugal’s ancient university city.Sharpe’s Escape begins on the great, gaunt ridge of Bussaco where a joint British and Portuguese army meets the overwhelming strength of Marshall Massena’s crack troops. It finishes at Torres Vedras where the French hopes of occupying Portugal quickly die.Soldier, hero, rogue – Sharpe is the man you always want on your side. Born in poverty, he joined the army to escape jail and climbed the ranks by sheer brutal courage. He knows no other family than the regiment of the 95th Rifles whose green jacket he proudly wears.