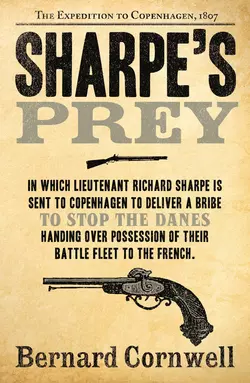

Sharpe’s Prey: The Expedition to Copenhagen, 1807

Bernard Cornwell

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 458.46 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Richard Sharpe is sent to Copenhagen to deliver a bribe to stop the Danes handing over possession of their battle fleet to the French.It seems very easy. But nothing is easy in a Europe stirred by French ambitions. The Danes possess a battle fleet that could replace every ship the French lost at Trafalgar, and Napoleon′s forces are gathering to take it. The British have to stop them, while the Danes insist on remaining neutral.Dragged into a war of spies and brutality, Sharpe finds that he is a sacrificial pawn. But pawns can sometimes change the game, and Sharpe makes his own rules. When he discovers a traitor in his midst, he becomes a hunter in a city besieged by British troops.Soldier, hero, rogue – Sharpe is the man you always want on your side. Born in poverty, he joined the army to escape jail and climbed the ranks by sheer brutal courage. He knows no other family than the regiment of the 95th Rifles whose green jacket he proudly wears.