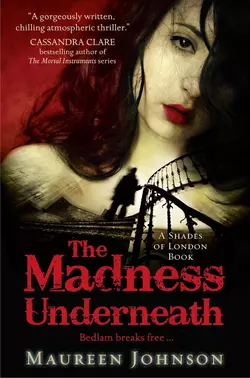

The Madness Underneath

The Madness Underneath

Maureen Johnson

When madness stalks the streets of London, no one is safe…There’s a creepy new terror haunting modern-day London.Fresh from defeating a Jack the Ripper killer, Rory must put her new-found hunting skills to the test before all hell breaks loose…But enemies are not always who you expect them to be and crazy times call for crazy solutions. A thrilling teen mystery.

For my friend, the real Alexander Newman, who would never let a tiny thing like having twelve strokes get the better of him. When I grow up, I want to be you. (Maybe without the twelve strokes? You know what I mean.)

Contents

Dedication

The Royal Gunpowder Pub, Artillery Lane, East London November 11 10:15 A.M. (#ulink_c0e49dc1-4e58-5bd6-84df-a7a5c2d424c7)

The Crack in the Floor (#ulink_da847850-4bc2-53a3-882d-c19cd49f2a7b)

Chapter 1 (#ulink_2e49d8ff-d82f-5ffa-8af8-e1a5403fb182)

Chapter 2 (#ulink_b086e891-3e78-5d42-97f8-ab784c710822)

Chapter 3 (#ulink_338cb44c-2972-5ced-ab94-0a7196917a3d)

Chapter 4 (#ulink_5cbdc362-064b-5d9f-97bf-bdd390a64f5d)

Chapter 5 (#ulink_6fd9401d-2e41-5f95-9da0-78c28c0abc47)

Chapter 6 (#ulink_2fa15340-9003-5f77-a86f-ed6c8926a9cc)

Chapter 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

New Dawn Psychic Parlor, East London December 9 11:47 P.M. (#litres_trial_promo)

The Falling Woman (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher

THE ROYAL GUNPOWDER PUB, ARTILLERY LANE, EAST LONDON NOVEMBER 11 10:15 A.M. (#ulink_d29e6886-16f2-5eaa-bfe1-94cf912b5e90)

HARLIE STRONG LIKED HIS CUSTOMERS—YOU DON’T run a pub for twenty-one years if you don’t like your customers—but there was something about the quiet in the morning that pleased him to no end. In the morning, Charlie had the one cigarette he allowed himself daily. He drew on the Silk Cut slowly, listening to the satisfying sizzle of burning paper and tobacco. He could smoke inside when no one else was here. Good mug of tea. Good smoke. Good bacon on his sandwich.

Charlie switched on the television. The television in the Royal Gunpowder went on for only two things: when Liverpool played and Morning with Michael and Alice, the relentlessly cheerful talk show. Charlie liked to watch this as he prepared for the day, particularly the cooking part. They always made something good, and for some reason, this made him enjoy his bacon sandwich even more. Today, they were making a roast chicken. His barman, Sam, came up from the basement with a box of tonic water. He set it on the bar and quietly got on with his work, taking the chairs from their upside-down positions on the tables and setting them upright on the floor. Sam was good to have around in the mornings. He didn’t say much, but he was still good company. He was happy to be employed, and it always showed.

“Good-looking chicken, that,” he said to Sam, pointing to the television.

Sam paused his work to look.

“I like mine fried,” Sam said.

“It’ll kill you, all that fried food.”

“Says the man eating the bacon sarnie.”

“Nothing wrong with bacon,” Charlie said, smiling.

Sam shook his head good-naturedly and continued moving chairs. “Think we’ll get more of them Ripper freaks today?” he asked.

“Let’s hope so. God bless the Ripper. We did almost three thousand pounds last night. Speaking of, they do eat a lot of crisps. Get us another box of the plain and”—he sorted through the selection under the bar—“cheese and onion. And some more nuts while you’re there. They like nuts as well. Nuts for the nutters, eh?”

Without a word, Sam stopped what he was doing and returned to the basement. Charlie’s gaze was fixed on the television and the final, critical stages of the cooking segment. The cooked chicken was produced from the oven, golden brown and lovely. The show moved on to the next segment, talking about some music festival that was going on in London over the weekend. This interested Charlie less than the chicken, but he watched it anyway since he had a cigarette to finish. When he was down to the filter, he stubbed it out and got to work.

He had just started wiping down the blackboard to write the day’s specials when he heard the sound of breaking glass from below. He opened the basement door.

“Sam! What in God’s name—”

“Charlie! Get down here!”

“What’s the matter?” Charlie yelled back.

Sam did not reply.

Charlie swore under his breath, allowed himself one heavy post-smoke cough, and headed down the stairs. The basement stairs were narrow and steep, and the basement itself was full of things Charlie largely didn’t want to deal with—broken chairs and tables, heavy crates of supplies, racks of glasses ready to replace the ones that were chipped, cracked, or stolen every day.

“Sam?” he called.

“In here!”

Sam’s voice was coming from a small room off the main one. Charlie ducked down. The ceiling was lower in this room; it just skimmed his head. Many times he had almost knocked himself senseless on it.

Sam was near the wall, cowering between two shelving units. There were two shattered pint glasses, as well as a roughly drawn X in chalk on the stone floor.

“What are you playing at, Sam?”

“I didn’t do that,” Sam replied. “Those weren’t there a few minutes ago.”

“Are you feeling all right?”

“I’m telling you, those weren’t there.”

This was not good, not good at all. The glasses clearly hadn’t fallen off a shelf—they were in the middle of the room. The X was shaky, like the hand that had drawn it could barely hold the chalk. No one looked healthy in the basement’s faintly greenish fluorescent light, but Sam looked particularly bad. The color had drained from his face, and he was quivering and glistening with sweat.

Maybe this had been bound to happen. Charlie had always known the risks, but the risks were part of the agreement. He had gotten sober, and he trusted that others could as well. And you needed to show that trust.

Charlie said quietly, “If you’ve been taking something—”

“I haven’t!”

“But if you have, you just need to tell me.”

“I swear to you,” Sam said, “I haven’t.”

“Sam, there’s no shame in it. Sobriety is a process.”

“I didn’t take anything, and I didn’t do that!”

There was an urgency in Sam’s voice that frightened Charlie, and he was not a man who frightened easily. He’d been through fights, withdrawal, divorce. He faced alcohol, his personal demon, every day. Yet, something in this room, something in the sight of Sam huddled against the wall and this crude X and broken glass on the floor . . . something in this unnerved him.

There was no point in checking to see if anyone else was down here. Every business in the area had fortified itself when the Ripper was around. The Royal Gunpowder was secure.

Charlie bent down and ran his hand over the cool stone floor.

“How about we just get rid of this,” he said, wiping away the chalked X with his hand. In cases like this, it was best to calmly get things back to normal and sit down and talk the issue through. “Come on, now. We’ll go upstairs and have a cup of tea, and we’ll talk this out.”

Sam took a few tentative steps from the wall.

“Good, that’s right. Now let’s just get rid of this and we’ll have a nice cuppa, you and me . . .”

Charlie continued wiping away the last of the X. He didn’t see the hammer.

The hammer was used to pry open crates, to knock sticky valves into action, and to do quick repairs on the often unstable shelving units. Now it rose, lingering just long enough over Charlie’s head to find its mark.

“No!” Sam screamed.

Charlie turned his head in time to see the hammer come down. The first time it did so, Charlie remained upright. He made a noise—not quite a word, more of a broken, gurgling sound. There was a second blow, and a third. Charlie was still upright, but twitching, struggling against the onslaught. The fourth blow seemed to do the most damage. An audible cracking sound could be heard. On that fourth blow, Charlie fell forward and did not move again.

The hammer clattered to the ground.

(#ulink_dccd3ea0-9e44-5b52-8555-1b475604138f)

Out flew the web and floated wide;

The mirror crack’d from side to side;

“The curse is come upon me,” cried

The Lady of Shalott.

—Alfred Lord Tennyson,

“The Lady of Shalott”

(#ulink_27d19512-d4d2-5307-95f4-0da7211e9d40)

ACK AT WEXFORD, WHERE I WENT TO SCHOOL BEFORE all of this happened to me, they made me play hockey every day. I had no idea how to play hockey, so they covered me in padding and made me stand in the goal. From the goal, I could watch my fellow players run around with sticks. Occasionally they’d whack a small, very hard ball in my direction. I would dive out of the way, every time. Apparently, avoiding the ball isn’t the point of hockey, and Claudia would scream, “No, Aurora, no!” from the sidelines, but I didn’t care. I take my best lessons from nature, and nature says, “When something flies at your head—move.”

I didn’t think hockey had trained me for anything in life until I went to therapy.

“So,” Julia said.

Julia was my therapist. She was Scottish and petite and had a shock of white-blond hair. She was probably in her fifties, but the lines in her face were imperceptible. She was a careful person, well spoken, so achingly professional it actually made me itch. She didn’t fuss around in her chair or need to change over and cross the other leg. She just sat there, calm as a monk. The winds might blow and the rains might fall, but Julia would remain in the same position in her ergonomic chair and wait it out.

The clock in Julia’s office was hidden in plain sight; she put it behind the chair where her patients sat, on top of a bookcase. I followed the clock by watching its reflection in the window, watching time run backward. I had just managed to waste a solid forty-five minutes talking about my grandmother—a new record for me. But I’d run out of steam, and the silence descended on the room like a vague but ever-intensifying smell. There was a lot going on behind her never-blinking eyes. I could tell, from what now amounted to hours of staring at her, that Julia was studying me even more carefully than I was studying her.

And I knew about her relationship with that clock. All she had to do was flick her eyes just a tiny bit to the left, and she could see both me and the time without moving her head. It was an incredibly small move, but I had started to look for it. When Julia checked the time, it meant she was about to do something.

Flick.

Time to get ready. Julia was going to make a move. The ball was heading for my face. Time to dodge.

“Rory, I want you to think back for me . . .”

Dive! Dive!

“. . . we all learn about death somehow. I want you to try to remember. How did you learn?”

I had to restrain myself. It doesn’t look good if your therapist asks you how you learned about death and you practically jump off the couch in excitement because that’s pretty much your favorite story ever. But as it happens, I have a really good “learning about death” story.

I wasted about a full minute, grinding away the airtime, tilting my head back and forth. It’s hard to pretend to think. Thinking doesn’t have an action stance. And I suspected that my “thinking” face looked a lot like my “I’m dizzy and may throw up” face.

“I was ten, I guess. We went to Mrs. Haverty’s house. She lived in Magnolia Hall. Magnolia Hall is this big heritage site, proper antebellum South, Gone with the Wind, look-at-how-things-were-before-the-War-of-Northern-Aggression sort of place. It has columns and shutters and about a hundred magnolia trees. Have you ever seen Gone with the Wind ?”

“A long time ago.”

“Well, it looks like that. It’s where tourists go. It’s on a lot of brochures. Everything about it looks like it’s from 1860 or something. And no one ever sees Mrs. Haverty, because she’s crazy old. Like, maybe she was born in 1860.”

“So an elderly woman in a historical house,” she said.

“Right. I was in Girl Scouts. I was a really bad Girl Scout. I never got any badges, and I forgot my troop number. But once a year there was this amazing picnic thing at Magnolia Hall. Mrs. Haverty let the Girl Scouts use the grounds, because apparently she had been a Girl Scout back when the rocks were young and the atmosphere was forming . . .”

Julia eyed me curiously. I shouldn’t have thrown in that little flourish. I’d told this story so many times that I’d refined it, given it nice little touches. My family loves it. I pull it out every year at our awkward get-together dinners at Big Jim’s or at my grandmother’s house. It’s my go-to story.

“So,” I said, slowing down, “she’d have barbecues set up, and huge coolers of soda, and ice cream. There was a massive Slip ’N Slide, and a bouncy castle. Basically, it was the best day of the year. I pretty much only did Girl Scouts so I could come to this. So this one summer, when I was ten, I guess . . . oh, I said that . . .”

“It’s all right.”

“Okay. Well, it was hot. Like, real hot. Louisiana hot. Like, over a hundred hot.”

“Hot,” Julia summarized.

“Right. Thing was, Mrs. Haverty never came out, and no one was allowed inside. She was kind of legendary. We always wondered if she was looking at us from the window or something. She was like our own personal Boo Radley. Afterward, we would always make her a huge banner where we’d write our names and thank her and draw pictures, and one of the troop leaders would drive it over. I don’t know if Mrs. Haverty let her in or if she just had to throw it out of the car window at the porch. Anyway, usually the Girl Scouts got Porta Potties for the picnic. But this year there was some kind of strike at the Porta Potti place and they couldn’t rent any, and for a week or so, they thought there was going to be no picnic, but then Mrs. Haverty said it was okay for us to use the downstairs bathroom, which was a really big deal. On the bus ride over, they gave us all a lecture on how to behave. One person at a time. No running. No yelling. Right to the bathroom and back out again. We were all excited and sort of freaked out that we could actually go inside. I made up my mind I was going to be the first person in. I was going to pee first if it killed me. So I drank an entire bottle of water on the ride—a big one. I made sure our troop leader, Mrs. Fletcher, saw me. I even made sure she said something to me about not wasting my water. But I was determined.”

I don’t know if this happens to you, but when I get talking about a place, all the details come back to me at once. I remember our bus going up the long drive, under the canopy of trees. I remember Jenny Savile sitting next to me, stinking of peanut butter for some reason and making an annoying clicking noise with her tongue. I remember my friend Erin just staring out the window and listening to something on her headphones, not paying any attention. Everyone else was looking at the crew that was inflating the bouncy castle. But I was on high alert, watching the house get closer, getting that first view of the columns and the grand porch. I was on a mission. I was going to be the first to pee in Magnolia Hall.

“My Scout leader was probably on to me,” I continued, “because I had a reputation for being that girl—not the leader or the baddest or the prettiest, or whatever that girl is. I was that girl who always had some little idea, some bone to pick or personal quest, and I would not be stopped until I had settled the matter. And if I was gulping water and bouncing in my seat, claiming extreme need of the bathroom, she knew I was not going to shut up until I was taken inside of Magnolia Hall.”

Julia couldn’t conceal the whisper of a smile that stole across her lips. Clearly, she had picked up on this aspect of my personality.

“When we pulled up,” I went on, “she said, ‘Come on, Rory.’ There was a real bite in how she said my name. I remember it scared me.”

“Scared you?”

“Because the Scout leaders never really got mad at us,” I explained. “It wasn’t part of their jobs. Your parents got mad at you, and maybe your teachers. But it was weird to have another adult be mad at me.”

“Did it stop you?”

“No,” I said. “I’d had a lot of water.”

“Let me ask you this,” Julia said. “Why do you think you behaved that way? Why did it matter so much to you to be the first one to use the toilet?”

This was something so obvious to me that I had no mechanism to explain it. I had to be first to that bathroom for the same reason that people climb mountains or go to the bottom of the sea. Because it was new and uncharted territory. Because being first meant . . . being first.

“No one had ever seen the inside of her house,” I said.

“But it was just a toilet. And you said this was a behavior you were aware of in yourself. That you come up with plans, ideas.”

“They’re usually bad plans,” I clarified.

Julia nodded slightly and wrote a note in her pad. I’d given her a clue about my personality. I hated when that happened. I refocused on the story. I remembered the heat. Heat—real heat—was something I hadn’t felt in England since I’d arrived. Louisiana summer heat has a personality, a weight to it. It wraps you entirely in its sweaty embrace. It goes inside of you. Magnolia Hall had never known an air conditioner. It was like an oven that had been on for a hundred years, and it felt entirely possible that some of the air trapped in there had been there since the Civil War, blown in during a battle and locked away for safekeeping.

I can always remember my first step through that doorway, that slap of dust-stinking heat. The stillness. The entrance hall with the genuine family portraits, the marble-topped table with a bowl of parched and drooping azaleas, the hoarded stacks of old newspapers in the corner. The bathroom was in an alcove under the stairs. Mrs. Fletcher had to supervise the unloading of the bus and make sure Melissa Murphy had her EpiPen in case she was stung by a bee, so she told me to come right out when I was done and not to touch anything. Just go to the bathroom and leave.

“I was in there by myself,” I said. “The first person ever . . . I mean, first person that I knew, so I couldn’t not look around. I only looked in rooms with open doorways. I didn’t snoop. I just had to look. And there was this dog in the middle of one of the sitting rooms in the front, a big golden retriever . . . and I like dogs. A lot. So I petted him. I didn’t even hear Mrs. Haverty come in. I just turned around and there she was. I guess I expected her to be in a hoop skirt or covered in spiderwebs or something, but she was wearing one of those sportswear things that actual senior citizens wear, pink plaid culottes and a matching T-shirt. She was incredibly pale, and she had all these varicose veins—her calves had so many blue lines on them, she looked like a road map. I thought I’d been caught. I thought, ‘This is it. This is when I get killed.’ I was so busted. But she just smiled and said, ‘That’s Big Bobby. Wasn’t he beautiful?’ And I said, ‘Was?’ And she said, ‘Oh, he’s stuffed, dear. Bobby died four years ago. But he liked to sleep in here, so that’s where I keep him.’”

It took Julia a moment to realize that that was the end of the story.

“You’d been petting a stuffed dog?” she said. “A dead one?”

“It was a really well stuffed dog,” I clarified. “I have seen some bad taxidermy. This was top-notch work. It would have fooled anyone.”

A rare moment of sunlight came in through the window and illuminated Julia’s face. She was giving me a long and penetrating stare, one that didn’t quite go through me. It got about halfway inside and roamed around, pawing inquisitively.

“You know, Rory,” she said, “this is our sixth meeting, and we really haven’t talked about the reason why you’re here.”

Whenever she said something like that, I felt a twinge in my abdomen. The wound had closed and was basically healed. The bandages were off, revealing the long cut and the new, angry red skin that bound the edges together. I searched my mind for something to say, something that would get us off-roading again, but Julia put up her hand preemptively. She knew. So I kept quiet for a moment and discovered my real thinking face. I could see it, but I could tell it looked pained. I kept pursing and biting my lips, and the furrow between my eyes was probably deep enough to hold my phone.

“Can I ask you something?” I finally said.

“Of course.”

“Am I allowed to be fine?”

“Of course you are. That’s our goal. But it’s also all right not to be fine. The simple fact of the matter is, you’ve had a trauma.”

“But don’t people get over traumas?”

“They do. With help.”

“Can’t people get over traumas without help?” I asked.

“Of course, but—”

“I’m just saying,” I said, more insistently, “is it possible that I’m actually okay?”

“Do you feel okay, Rory?”

“I just want to go back to school.”

“You want to go back?” she asked, her brogue flicking up to a particularly inquisitive point. You want tae go back?

Wexford leapt into my mind, like a painted backdrop on a suddenly slackened rope crashing down onto a stage. I saw Hawthorne, my building, looking like the Victorian relic that it was. The brown stone. The surprisingly large, high windows. The word WOMEN carved over the door. I imagined being in my room with Jazza, my roommate, at nighttime, when she and I would talk across the darkness from our respective beds. The ceilings in our building were high, and I’d watch passing shadows from the London streets and hear the noise outside, the gentle clang and whistle of the heaters as they gave the last blast of heat for the night.

My mind flashed to a time in the library, when Jerome and I were together in one of the study rooms, making out against the wall. And then I flashed somewhere else. I pictured myself in the flat on Goodwin’s Court with Stephen and Callum and Boo—

“We’re at time for today,” she said, her eye flicking toward the clock. “We can talk about this some more on Friday.”

I snatched my coat from the back of the chair and got it on as quickly as possible. Julia opened the door and looked out into the hall. She turned back to me in surprise.

“You came by yourself today? That’s very good. I’m glad.”

Today, my parents had let me come to therapy by myself. This was what passed for excitement in my life now.

“We’re getting there, Rory,” she said. “We’re getting there.”

She was lying. I guess we all have to lie sometimes. I was about to do the same.

“Yeah,” I said, stretching my fingers into the tips of my gloves. “Definitely.”

(#ulink_98a4b182-72bc-5b7d-9b45-0418050d5b1c)

WASN’T GOING TO BE ABLE TO COPE WITH MANY MORE of these sessions.

I like to talk. Talking is kind of my thing. If talking had been a sport option at Wexford, I would have been captain. But sports always have to involve running, jumping, or swinging your arms around. You don’t get PE points for the smooth and rapid movement of the jaw.

Three times a week, I was sent to talk to Julia. And three times a week, I had to avoid talking to Julia—at least, I couldn’t talk about what had really happened to me.

You cannot tell your therapist you have been stabbed by a ghost.

You cannot tell her that you could see the ghost because you developed the ability to see dead people after choking on some beef at dinner.

If you say any of that, they will put you in a sack and take you to a room walled in bouncy rubber and you will never be allowed to touch scissors again. The situation will only get worse if you explain to your therapist that you have friends in the secret ghost police of London, and that you are really not supposed to be talking about this because some man from the government made you sign a copy of the Official Secrets Act and promise never to talk about these ghost police friends of yours. No. That won’t improve your situation at all. The therapist will add “paranoid delusions about secret government agencies” to the already quite long list of your problems, and then it will be game over for you, Crazy.

The sky was the same color as a cinder block, and I didn’t have an umbrella to protect me from the dark rain cloud that was clearly moving in our direction. I had no idea what to do with myself, now that I was actually out of the house. I saw a coffee place. That’s where I would go. I’d get a coffee, and then I’d walk home. That was a good, normal thing to do. I would do this, and then maybe . . . maybe I would do another thing.

Funny thing when you don’t get out of the house for a while—you reenter the outside world as a tourist. I stared at the people working on laptops, studying, writing things down in notebooks. I flirted with the idea of telling the guy who was making my latte, just blurting it out: “I’m the girl the Ripper attacked.” And I could whip up my shirt and show him the still-healing wound. You couldn’t fake the thing I had stretching across my torso—the long, angry line. Well, I guess you could, but you’d have to be one of those special-effects makeup people to do it. Also, people who get up to the coffee counter and whip off their shirts for the baristas usually have other problems.

I took my coffee and left quickly before I got any other funny little ideas.

God, I needed to talk to someone.

I don’t know about you, but when something happens to me—good, bad, boring, it doesn’t matter—I have to tell someone about it to make it count. There’s no point in anything happening if you can’t talk about it. And this was the biggest something of all. I ached to talk. I mean, it literally hurt me, sitting there, holding it all in hour after hour. I must have been clenching my stomach muscles the whole time, because my whole abdomen throbbed. Sometimes, if I was still awake late at night, I’d be tempted to call some anonymous crisis hotline and tell some random person my story, but I knew what would happen. They’d listen, and they’d advise me to get psychiatric help. Because my story was nuts.

The “official” story:

A man decides to terrorize London by re-creating the murders of Jack the Ripper. He kills four people, one of them, unluckily, on the green right in front of my building at school. I see this guy when sneaking back into my building that night. Because I’m a witness, he decides to target me for the last murder. He sneaks into my building on the night of the final Ripper murder and stabs me. I survive because the police get a report of a sighting of something suspicious and break into the building. The suspect flees, the police chase him, and he jumps into the Thames and dies.

The real version:

The Ripper was the ghost of a man formerly of the ghost policing squad. He targeted me because I could see ghosts. His whole aim was to get his hands on a terminus, the tool the ghost police use to destroy ghosts. The termini (there were actually three of them) were diamonds. When you ran an electrical current through them, they destroyed ghosts. Stephen had wired them into the hollow bodies of cell phones, using the batteries to power the charge. I survived that night because Jo, another ghost, grabbed a terminus out of my hand and destroyed the Ripper—and, in the process, herself.

The only people who really knew the whole story were Stephen, Callum, and Boo, and I was never allowed to talk to them again. That was one of the conditions when I left London. A man from the government really had made me sign the Official Secrets Act. Measures had been taken to make sure I couldn’t reach out to them. While I was in the hospital after the attack, knocked out cold, someone took my phone and wiped it clean.

Keep quiet, they said.

Just get on with your life, they said.

So now I was here, in Bristol, sitting around in the rented house that my parents lived in. It was a nice enough little house, high up on a rise, with a good view of the city. It had rental house furnishings, straight out of a catalog. White walls and neutral colors. A non-place, good for recuperating. No ghosts. No explosions. Just television and rain and lots of sleep and screwing around on the Internet. My life went nowhere here, and that was fine. I’d had enough excitement. I just had to try to forget, to embrace the boredom, to let it go.

I walked along the waterside. The mist dropped layer upon delicate layer of moisture into my clothes and hair, slowly chilling me and weighing me down. Nothing to do but walk today. I would walk and walk. Maybe I would walk right down the river into another town. Maybe I would walk all the way to the ocean. Maybe I would swim home.

I was so preoccupied in my wallowing that I almost walked right past him, but something about the suit must have caught my attention. The cut of the suit . . . something was strange about it. I’m not an expert on suits, but this one was somehow different, a very drab gray with a narrow lapel. And the collar. The collar was odd. He wore horn-rim glasses, and his hair was very short, but with square sideburns. Everything was just a centimeter or two off, all the little data points that tell you someone isn’t quite right.

He was a ghost.

My ability to see ghosts, my “sight,” was the result of two elements: I had the innate ability, and I’d had a brush with death at the right time. It was not magic. It was not supernatural. It was, as Stephen liked to put it, the “ability to recognize and interact with the vestigial energy of an otherwise deceased person, one who continues to exist in a spectrum usually not perceived by humans.” Stephen actually talked like that.

What it meant was simply this: some people, when they die, don’t entirely eject from this world. Something goes wrong in the death process, like when you try to shut down a computer and it goes into a confused spiral. These unlucky people remain on some plane of existence that intersects with the one we inhabit. Most of them are weak, barely able to interact with our physical world. Some are a bit stronger. And lucky people like me can see them, and talk to them, and touch them.

This is why in my many, many hours of watching shows about ghost hunters (I’d watched a lot of television in Bristol) I’d gotten so angry. Not only were the shows stupid and obviously phony, but they didn’t even make sense. These people would rock up to houses with their weird night-vision camera hats and cold-spot-o-meters, set up cameras, and then turn off all the lights and wait until dark. (Because apparently ghosts care if the lights are on or off and if it’s day or night.) And then, these champions would fumble around in the dark, saying, “IF SPIRITS ARE HERE, MAKE YOURSELVES KNOWN, SPIRITS.” This is roughly equivalent to a tourist bus stopping in the middle of a foreign city and all of the tourists getting out in their funny hats with their video cameras and saying, “We are here! Dance for us, natives of this place! We wish to film you!” And, of course, nothing happens. Then there’s always a bump in the background, some normal creaking of a step or something, and they amplify that about ten million times, claim they’ve found evidence of paranormal activity, and kick off for a cold, self-congratulatory brew.

I edged around for a few minutes, taking him in from a few different angles, making sure I knew what I was looking at. I wondered what the chances were that the first time I came out and walked around Bristol on my own, I’d see a ghost. Judging from what was going on right now, those chances were very good. A hundred percent, in fact. It made a kind of sense that I’d find one here. I was walking along a river and, as Stephen had explained to me once, waterways have a long history of death. Ships sink and people jump into rivers. Rivers and ghosts go together.

I crossed in front of him, pretending to talk on my phone. He had a blank stare on his face, the stare of someone who truly had nothing to do but just exist. I stared right at him. Most people, when stared at, stare back. Because staring is weird. But ghosts are used to people looking right through them. As I suspected, he didn’t react in any way to my staring. There was a grayness, a loneliness about him that was palpable. Unseen, unheard, unloved. He was still existing, but for no reason.

Definitely a ghost.

It occurred to me, he could have a friend. He could have someone to share this existence with. Something welled up in me, a great feeling of warmth, of generosity, a swelling of the spirit. I could share something with him, and in return, he could help me as well. Whoever this guy was, I could tell him the truth. He was part of the truth. No, he didn’t know me, but that hardly mattered. He was about to get to know me. We would be friends. Oh, yes. We would be friends. We were meant to be together. For the first time in weeks, there was a path—a logical, clear, walkable path. And it started with me sitting on the bench.

“Hi,” I said.

He didn’t turn.

“Hi,” I said again. “Yes, I’m talking to you. On the bench. Here. With me. Can you hear me?”

He turned to look at me, his eyes wide in surprise.

“Bet you’re surprised,” I said, smiling. “I know. It’s weird. But I can see you. My name’s Rory. What’s yours?”

No answer. Just a wide, eternal stare.

“I’m new here,” I said. “To Bristol. I was in London. I’m from America, but I guess you can tell that from my accent? I came here to go to school, and—”

The man bolted from his seat. Ghosts have a fluidity of movement that the living don’t know—they remain solid, yet they can move like air. I didn’t want him to go, so I bounced up and reached as far as I could to catch his coat. The second I made contact, I felt my fingers getting pulled into his body, like I had put them into the suction end of a vacuum. I felt the ripple of energy going up my arm, the inexorable force linking us both together now, then the rush of air, far greater than any waterside breeze. Then came the flash of light and the unsettling floral smell.

And he was gone.

(#ulink_3d28b9c2-2817-5807-b959-50b1ca0bde32)

HIS DESTROYING-THE-DEAD-WITH-A-SINGLE-TOUCH thing was even more recent than the seeing-the-dead thing. It had happened once before, the day I left Wexford. I’d found a strange woman in the downstairs bathroom where I’d been stabbed. She too had looked frightened, and I’d reached out, and she too had exploded into nothingness. I’d tried to tell myself that this had been a fluke, something to do with the room itself. The bathroom was where the Ripper had cornered me. The bathroom was where the terminus had exploded. I’d convinced myself that the room did it.

But no. It was me.

I walked home, an entirely uphill walk in every way, feeling queasy and shaky. Once there, I went to the “conservatory,” which was really just a glassed-in porch. I sat with my head resting on my knees and replayed the scene again and again in my head. The inevitable rain came and tapped on the roof, rolling down the panes of glass.

I’d tried to make a new friend, and I had blown him up.

I’d been told to keep quiet, and I had. But it wasn’t going to work anymore. I needed Stephen, Callum, and Boo again. I needed them to know what was going on with me. I had made a few efforts to find them in the last week. Nothing serious—I’d just tried to find profiles on social networking sites. No matches. This much I expected.

Today I was going to try a bit harder. I Googled each of their names. I found one set of links that were definitely about Callum. Callum had mentioned that he was good at football. What he didn’t say was that he had been a member of the Arsenal Under-16s, a premier-level junior club. He’d been in training to become a professional footballer. And all of that ended one day when he was fifteen, when a malicious ghost let a live wire drop into the puddle Callum was stepping through. He survived the electrocution and recovered, but something in him was never the same. Whether it was physical or psychological, who knew, but he couldn’t play football anymore. The magic was gone. Callum hated ghosts. He wanted them to burn.

In terms of contact information, though, there was nothing.

I moved on to Boo, Bhuvana Chodhari. Boo had been sent into Wexford as my roommate after I saw the Ripper. It was her first job with the squad. There were a lot of Chodharis in London, and even quite a few Bhuvana Chodharis. I knew Boo had been in a serious car accident, but I found nothing about it. Nothing about Boo at all, really. That surprised me. Of the three of them, I expected her to pop up somewhere. But I guess once you joined the squad, your Facebook days were over.

I searched for Stephen last. In terms of his past, I knew very little. I think he said once he was from Kent, but Kent was a big place. He went to Eton. He had been on the rowing team while he was there. I started with that, and managed to come up with one photo of a rowing team in which I could clearly see him in the back. He was one of the tallest, with dark hair and eyes fixed at the camera. He was one of the not-smiling ones. In fact, he was the least-smiling person in the photo. Like everyone else, he had his arms folded over his chest, but he seemed to mean it.

But again, there was nothing in terms of how to make contact.

I stared at the photo of Stephen for a long time, then at the ceiling of the conservatory, which was thick with condensation and fat drops of water. I knew that Stephen and Callum shared a flat on a small street in London called Goodwin’s Court. I’d been there. I had never, however, looked at the building number. The few times I’d been there, I was following someone to the door, usually in a state of distress.

I pulled up a map and some images of the street. The trouble with Goodwin’s Court was that it was very picturesque, and very small, and all of it looked more or less the same. The houses were all quite dark, with dark brick and black trim, so it was hard to see numbers. I found one pretty grainy picture that I thought was probably their house, but I couldn’t see the number.

My phone rang. It was Jerome. He often called me on his break between classes. Jerome had been what I suppose I could call my “make-out buddy” at Wexford. But since I’d been gone, we had become something much more. I still couldn’t talk to him the way I needed to talk to someone, but it was nice that I had someone in theory. An imaginary boyfriend I never saw. We were planning to see each other over the Christmas break in a few weeks, probably only for a day, but still. It was something.

“Hey, disgusting,” he said.

Jerome and I had developed a code for expressing whatever it was we felt for each other. Instead of saying “I like you” or whatever mush expresses that sentiment, we had started saying mildly insulting things. Our entire correspondence was a string of heartfelt insults.

“What’s wrong?”

“Nothing,” I said quickly. “Nothing.”

“You sound funny.”

“You look funny,” I replied.

I could hear Wexford noises in the background. Not that Wexford noises were so particular. It was just noise. People. Voices. Guys’ voices.

He was talking quickly, telling me a story about some guy in his building who’d been busted for claiming to have an interview at a university, but actually he went off to see his girlfriend in Spain, and how someone had ratted him out to Jerome, and Jerome had the unwelcome task of reporting him. Or something.

I was only half listening. I rubbed at my legs and stared at the images of Goodwin’s Court. I hadn’t shaved in three weeks, so that was quite a situation I had going. For the first few days, I hadn’t been able to bend over completely or get the injured area wet, so I couldn’t shave. The hairs sprouted, and they were kind of cute. So I just let them go to see what would happen, and what had happened was that I had a fine web of delicate hair all over my legs that I could ruffle while I watched television, like some people absently pet their cats. I was my very own fuzzy pet.

The grainy picture told me nothing.

“Hello?” Jerome said.

“I’m listening,” I lied. I guess the story had finished.

“I have to go,” he said. “You’re disgusting. I want you to know that.”

“I heard they named a mold after you,” I replied. “Poor mold.”

“Vile.”

“Gross.”

After I hung up, I pulled the computer closer to stare at the image. I moved the view up and down the row of tiny, dark houses with their expensive gaslights and security system warning signs. Up and down. And then I saw something. There was a tiny plaque on the outside of one of the houses, right above the buzzer. That plaque. I knew it. That was their building. There was some kind of a small company downstairs, a graphic designer or photographer or something like that. The print was impossible to make out in the photo, but it began with a Z. I knew that much. Zoomba, Zoo . . . Zo . . . something.

It was a start, enough to search the Internet. I tried every combination I could with Z and design and art and photography and graphic design. It took a while, but I eventually hit it. Zuoko. Zuoko Graphics. With a phone number. I pulled up the address in maps, and sure enough, it was the same building.

Now all I had to do was call and ask them . . . something. Get them to go upstairs. Leave a note. I would say it was an emergency and that they needed to call Rory, and I would leave my number. So simple, so clever.

So I called, and Zuoko Graphics answered. Well, some woman did. Not the entire agency.

“Hi,” I said. “I’m trying to reach someone else in this building. It’s kind of an emergency. Sorry to bug you. But there are some guys? Who live upstairs? From you?”

“Two guys, right?” the woman said. “About nineteen or twenty?”

“That’s them,” I said.

“They moved out, about a week and a half ago.”

“Oh . . .”

“You said it’s an emergency? Do you have another way of reaching them, or—”

“It’s okay,” I said. “Thanks.”

So that was that. I struck that off the list. They’d moved out. Because of me? Because I knew where they lived? Maybe they were really cleaning up their tracks so they could never be found again.

I heard someone come into the house. I quickly clicked on a link to BBC news and pretended to be deeply engrossed in world affairs. My mom came into the kitchen.

“We have chairs,” she said.

“I like it down here. It’s where I belong.”

“Doing some work?” she asked.

My parents weren’t stupid. They knew I hadn’t really been keeping up with school stuff, but they hadn’t been pressuring me. I was recovering. Everyone was very gentle with me. Soft voices. Food on demand. Command of the remote control. But there was just a little lilt of hope in her voice, and I hated to disappoint her.

“Yup,” I lied.

“I just got a call from Julia. She’s asking all of us to come in tomorrow for a group session. Is that all right with you?”

I ran my thumbs along the bottom edge of my computer. This wasn’t right. We didn’t do group sessions. Was this an intervention? It sounded like an intervention, at least like the ones I had seen on TV. They get your family and a psychologist, and they sit you in a room and tell you that the game is up, you have to change. Change or die. Except . . . I didn’t drink or do drugs, so I wasn’t sure what they could intervene about. You can’t stop someone from doing nothing all time.

I thought about the man again . . . my hand reaching out in greeting. Maybe the first greeting he’d had in years. The hand that wiped him from existence. Or something.

“Sure,” I said, slightly dazed. “Whatever.”

The next day at noon, the three of us waited by Julia’s door, staring down at the little smoke-detector-shaped noise-reduction devices that lined the hallway. That’s how you could tell a therapist was behind the door. One of these little privacy devices would spring up naturally, like a mushroom after a rainstorm.

“So,” Julia said, once we were all squeezed onto her sofa, “I want to talk to all of you about the progress we’ve made, and just a little bit about the process. Recovering from a trauma like this. There’s no one method that fits everyone. I want you to know, and I want you to hear this, Rory . . . I think Rory is very, very strong. I think she’s resilient and capable.”

It was supposed to make me feel good, but I burned . . . burned with anger or embarrassment or resentment. I felt my cheeks flush. This was the worst of it. Right now, this. I’d survived the stabbing. I’d survived all of the other, much crazier stuff. But now I was a victim. I might as well have had the word tattooed on my face. And victims get strange looks and psychologists. Victims have to sit between their parents while they’re told how “resilient” they are.

“In my opinion, I feel . . . very strongly . . . that Rory should be returned to Wexford.”

I seriously almost fell off the sofa.

“I’m sorry?” my mother said. “You think she should go back?”

“I realize what I’m saying may run counter to all your instincts,” Julia said, “but let me explain. When someone survives a violent assault, a measure of control is taken away. In therapy, we aim to give victims back their sense of control over their own lives. Rory’s been removed from her school, taken away from her friends, taken out of her routine, out of her academic life. I believe she needs to return. Her life belongs to her, and we can’t let her attacker take that away.”

My dad had a look in his eye that I’d once seen in a painting at the National Gallery. It was of a man who was facing down an angel that had just come crashing through his ceiling and was now glowing expectantly in the corner of the room. A surprised look.

“I say this with full understanding that the idea may be difficult for all of you,” she continued, mostly to my parents. “If you decide against this, that’s absolutely fine. But I feel the need to tell you this . . . Rory and I have done quite a lot of work in our sessions. I’m not saying we’ve done all we can do. I’m saying the next logical step is to get her back into a normal routine.”

She was lying. Julia, right now, was lying. And she was looking right at me, as if challenging me to contradict her. We both knew perfectly well that I’d told her nothing at all. Why the hell would Julia lie? Had I said things without even realizing it?

“She can have a normal routine here,” my mom said.

“It’s not her normal routine. It’s a new routine based around the attack. Right now, keeping her away from the learning environment is punitive. I’m not talking about sending Rory out to live in a wild and dangerous environment—this is a structured one, with everything in place to allow her to resume her life.”

“An environment where she was stabbed,” my dad said.

“Very true. But that particular case was a true anomaly. You need to separate your fears from the actual risk involved. What happened will not be repeated. The attacker is deceased.”

Their conversation became a low buzzing noise, like the background sound that’s supposed to run across the universe. Of course I couldn’t go back. My parents would never agree to it. It had taken me a week to convince them I could walk down the hill by myself. They were never going to send me back to school, in London, to the very place I’d been stabbed. Julia might as well have asked me, “Rory, do you want to go live in the sky? On a Pegasus?” It was not going to happen.

As ridiculous as this all was, if there is one thing that could sway my parents, it was a professional opinion. An expert witness. They both dealt with them all the time, and they knew how to take that knowledge and advice. Julia was a professional, and she said this was what I needed. They were still listening.

“I’ve been in touch with them,” she went on. “There are new security measures in place. They have a new system that apparently cost a half a million pounds.”

“They should have had that before,” my dad said.

“It’s best to think forward,” Julia said gently, “not backward. The system includes biometric entry pads and forty new CCTV cameras feeding into a constantly monitored station. Curfew hours have been changed. And the police now include Wexford on a patrol, simply because of all of the publicity. The reality is that it is probably the most secure environment she could be in right now. The school term is only going to last about two more weeks. This short period would allow her to reintegrate herself. It’s an excellent trial run to get Rory back into a more normal routine.”

Oh, the silence in that room. The silence of a thousand silences. I could hear that stupid clock ticking away.

“Do you really feel ready?” my mom asked me. “Don’t let anyone talk you into feeling like you’re ready.”

It wasn’t phrased as a question—I think it was more of an invitation. They wanted me to say I wasn’t ready, and we would just go on like this, safe and secure and static.

This was happening. They were saying yes. Yes, I could go back. No, they didn’t want me to, and yes, it went against every instinct they had . . . and possibly against every instinct I had.

(#ulink_bb5f3c18-c5f5-50a2-b944-75c723cc6362)

’M NOT SURE WHAT I EXPECTED TO SEE AS WE BUMPED along the cobblestone road that fronted Hawthorne. Maybe I thought Wexford would be covered in creeping vines, or part of it would have crumbled from age. This was maybe a bit extreme for three weeks, but three weeks is a lot of time in school time, especially when you live at said school. Miss three weeks, and you come back to a different world.

There were Christmas decorations on the streets, for a start. Christmas ads in the bus shelters. Christmas displays in windows. It was three in the afternoon, but the lights by the front door were switched on and the sky had taken on a dusky tint. Claudia, our hockey-loving, large-handed housemistress, met me at the front door, just as she had when I’d first arrived. This time, though, she came down the steps and gave me a car-crusher of a hug.

“Auror a. It is good to see you. And your parents . . . Call me Claudia. I’m housemistress of Hawthorne.”

Claudia managed the entire return and good-bye process, assuring my parents in every possible way aside from interpretive dance that all would be well and I would be looked after and coming back to school was very much the right thing for me. Before they left, my parents went through the personal rules we’d established. I’d call them every day. I would never take the Tube after nine at night. I would carry a rape whistle, which I’d already been given and which was already attached to my bag.

Claudia shepherded them back to the car. I finally understood why she was in charge of our building. She had skills with parents. She was like the parent whisperer.

“I want you to know,” she said, when we were alone and back in the safety of her office, “I think what you are doing is exceptionally courageous, and all of us here at Wexford are behind you. Those events . . . are in the past. You’re here to pick up where you left off, and you will have an excellent rest of term. I encourage you to take advantage of our health services. Mr. Maxwell at the sanatorium is an excellent counselor. He’s helped many students . . .”

“I have someone,” I said. “Back in Bristol.”

“But you might want someone here. If you do, Mr. Maxwell would be happy to see you at any time. But enough of that. How are you coming along with your lessons?”

“I’m a little . . . behind.”

“Quite understandable,” she said, as gently as Claudia could say anything. “We have people to help bring you up to speed in all your subjects. Charlotte has already volunteered, and your teachers certainly know the circumstances. For the time being, we’ll keep you out of hockey so you can use that time to catch up.”

I tried to look sad.

“Don’t worry,” she said. “Next term, we’ll have you back out there.”

I would work on that one later. There was no way I was going back “out there.”

“Now,” she said, “we’re almost to the end of term. Next week is the final week of classes. Then there’s revision over the weekend and through Monday of the following week, with exams on Tuesday and Wednesday. Obviously, you’ve missed too much to take a full exam, but we’ve worked something out for you. All of your teachers will assess your current level, both through classwork and through some informal testing, and you’ll be provided with modified versions of the exams. If necessary, we’ll give you take-home exams that you can complete over the holidays. Your teachers are prepared to work with you if you are willing to put in the effort. All right?”

Claudia fished around in the top drawer of her desk and produced a small black box. She jacked this into her computer and pushed it across the desk in my direction.

“Are you right-handed?” she asked me.

I nodded.

“Just put your right index finger on the pad there and hold it still for a moment.”

There was a square on the top of the box marked off in white. I put my finger on it, and she clicked the mouse a few times.

“Rotten thing,” she mumbled. “Always takes a . . . ah. There we go. Now, let me show you how this works.”

She led me back to the front door and pointed to a small touchpad.

“Try it now to see if your fingerprint was accepted.”

I put my finger on the pad. A purple light came on, and there was a click.

“Oh, good. Sometimes it doesn’t like the first time we take the impression. This is how you get in and out. It gives you ten seconds, or you have to do it again. The system monitors the whereabouts of all students. We know when you go in and out of this building. And no one goes in or out between eleven at night and five thirty in the morning. Now, why don’t you go up and get yourself settled back in?”

The stairs of Hawthorne had a pronounced, musical creak as I walked back up to my room. My hall was much more narrow than I remembered, and I clunked along to my room with my last bag. Mr. Franks, our ancient custodian, had taken all my other things up at some point when I was in with Claudia. The room was weirdly bare. All of Jazza’s things were over on one side. The two other beds—Boo’s and mine—were stripped down to the mattress. I would have spread out in every direction, but Jazza had kept to her third with a devotion that made me tear up a little. It was like she refused to accept we weren’t there. The only thing Jazza had added was a new floor lamp—a wobbly thing with a plastic upturned shade. It gave the room a warm glow when I switched it on.

I went to the window and looked out at the square. That’s where the police had found the girl’s body. That was the square I ran across when I met the Ripper. Everything had a Ripper memory attached to it. Julia had given me a whole talk about forging new mental connections to things. She’d said that after a while, the Ripper stuff would take on less significance, and when I looked around Wexford, I’d have new, more positive thoughts come to mind.

She also said it could take a while.

The building was freezing. During the day, they shut the heat down to conserve electricity. It came back up again at night and in the morning, but it was never really that warm. In Bristol, my parents had kept the house so hot, the windows would steam. This was considered very American, but in our defense, we are Southern. We get cold.

I was not going to be a baby about a little cold. I put on my fleece and set to work unpacking boxes and bags. I refilled my drawers, trying to remember the exact way I had arranged things before my untimely departure. I piled all my textbooks in order of subject. Further maths, French, English literature (from 1711 to 1847), art history, and normal history. I stepped back and examined my effort. Yup. Those were my books. Familiar, yet foreign, a wealth of information stashed behind every spine.

What I needed to do now was figure out how behind I was. That meant going through all the notes my teachers had been sending me while I was gone, marking off chapters, counting up assignments.

I pulled out the lists I’d been given: the pages I was supposed to have read, the essays I was supposed to have started, the problem sets I’d been given. I did the math. It didn’t take long. Zero plus zero plus zero plus zero equals zero. When should I tell my teachers that I hadn’t actually done anything since I left?

I flipped to the front of my binder and looked at the term schedule. Just about two weeks. That’s all that was left of the term. So what if the exams started in . . . twelve days?

I shut the binder. One step at a time. Today’s step was just getting back to school. No need to take it all in at once.

I turned my mind to other matters. I still had no idea where Stephen, Callum, and Boo were, but now that I was back in London, it seemed like I’d have a much better chance of finding them. Possibly. I wasn’t exactly sure how. They didn’t really have a beat or a known routine. The only one who was ever in the same general place was Callum. He covered the Underground network. I guessed I could ride the Tube for hours and hours, trying to catch a glimpse of him at some station. That wasn’t much of a plan. London is a very big place—one of the biggest cities in the world—and the Underground went on for hundreds of miles and had dozens of stations and millions of riders.

I would think of something. In the meantime, I needed something to do, someone to talk to. And there was someone here I could have a chat with. But to do that, I needed to put the uniform back on. Back on with the gray skirt and the white blouse. I could feel myself becoming a Wexford person again through the feel of the fabric—the slight polyester squeak of the skirt, the stiff collar of the shirt. But it was always the tie that did it for me. I looped it around my neck and fumbled with it for a moment until I had it right. I was Wexford property again.

Alistair spent most of his time in the library because he thought Aldshot smelled bad. His favorite spot was up in the stacks, in the romantic poetry section, in a dark little corner by a frosted glass window. This was where I found him, spread out in his usual way.

Alistair died in the 1980s, when overcoats were big and hair was even bigger. He was used to people walking past him, or over him, or through him, so he didn’t really pay any attention when I stood by his Doc Martens.

I was careful to leave a lot of distance between us. Blowing up one potential friend by accident, well, that can happen. Blowing up another would be carelessness.

“Hey,” I said, “Alistair.”

A slow drawing up of the head.

“You’re back,” he said.

“I’m back,” I replied.

“Boo said they took you to Bristol. That you wouldn’t be coming back, ever.”

“I’m back,” I said again.

Alistair wasn’t the hugging type, but I took the fact that he hadn’t already started reading again as a sign that he welcomed my presence. I slid down the wall and took a seat on the floor, tucking up my legs so we didn’t tap into each other.

“One thing,” I said. “Never touch me. Don’t even get near me.”

“Nice to see you too.”

“No, I mean . . . something’s gone wrong with me. And now I am bad for you. Really. No joke.”

“Bad for me?”

It’s really hard to tell someone you can destroy them with a touch. It’s not the kind of thing that should ever come up in conversation.

“I’m unlucky,” I said, in an attempt to cover. “I attract nutjobs and trouble.”

“So why’d you come back?”

“Why wouldn’t I?”

“You got stabbed,” he said.

“I got better. I was bored sitting around at home.”

“And you came back here? Why didn’t you go back to America?”

“Someone’s renting our house,” I said. “And my shrink said I needed to come back to get my normal life back.”

“Normal life?” That got a dark little laugh.

It was good to see Alistair was the same cheerful entity that I’d left behind.

“So the Ripper,” he said. “The news says he died, that he jumped off a bridge. That’s a lie. They covered it all up. Typical. The press lies. The government lies. They all want to keep people in the dark.”

He scraped the rubbery sole of his shoe against the library floor. It made no noise.

“I don’t think that many people in the government actually know what happened.”

“Oh, they know,” he said. “Thatcher and her kind always know.”

“It’s not Thatcher anymore,” I said.

“Might as well be. They’re all the same. Liars.”

I heard footsteps approaching. The library wasn’t very populated during the day, and not many people made a point of coming to this corner of the second floor. This is why Alistair liked it. It was the literature corner, full of works of criticism. It was also a bit dim and cold.

Whoever was coming seemed to really want some criticism, because the footsteps were sharp and fast. The person hit a switch, waking up the aisle lights, which reluctantly flicked on one by one.

“I thought you might be here,” he said.

I recognized Jerome, obviously, but there was something very strange, something almost a little foreign. His hair had gotten just a touch shaggy and was falling into a center part. His tie was a bit loose. He seemed about an inch taller than I remembered, and slouchy shouldered. And his eyes were smaller. Not in a bad way. My memory had screwed everything up and adjusted all the measurements.

“Oh, God,” Alistair said. “Already?”

I’d gotten used to not being around Jerome, and strangely, this had made us closer. We’d definitely gotten more serious in the last two weeks, but we’d done it all over the phone or on a screen. I’d grown accustomed to Jerome as a text message, and it was somewhat unsettling to have the actual person sliding down the wall to sit next to me. Unsettling, but also a bit thrilling.

“Welcome back, stupid,” he said.

“Thanks, dumbass.”

Jerome shifted a bit, moving closer to me. He smelled strongly of Wexford laundry detergent. He looked down at my hand, which was resting on my thigh, then reached out and touched it, gently tapping the back of my hand with his fingers. We both looked at this gesture, like it was something our hands were doing of their own accord. Like they were children putting on a show for us, and we, the indulgent parents, were watching them.

“On the way here, I saw someone pissing on a wall,” I said. “It reminded me of you.”

“That was me,” he replied. “I was writing a poem about your beauty.”

“I hate you both,” Alistair said, from his side of the dark corner.

I ignored him as Jerome brushed my hair away from my face. When anyone touches my hair, I basically turn to slush. If a friend does it, or if I’m getting my hair cut, I fall asleep. When Jerome did it, it sent an entirely different sensation through my body—warm and wibbly.

The lights in the aisle clicked out. They did that automatically after about three minutes. I flinched. Actually, it was a bit more than a flinch—it was a full-body jerk and a small, high-pitched noise.

“It’s okay,” Jerome said, raising his arm and making a space for me to lean against him. I accepted this offer, and he wrapped his arm around my shoulders.

Here’s something I do that’s really great: when I get nervous, I tell completely irrelevant and often very inappropriate stories. They just come out of my mouth. I felt one coming up now, rising out of whatever pit in my body I keep all the nervous tics and terrible conversation starters.

“We had this neighbor once,” I said, “who named his dog Dicknickel . . .”

Jerome was somewhat familiar with my quirks by now, and wisely took my chin in his hand and directed my face toward him. He nuzzled me with the tip of his nose, drawing it lightly against my cheek as he made his way toward my lips. The wibbliness got wibblier, and I craned my neck up. Jerome kissed it lightly, and I let out a little noise—a completely involuntary and small groan of happiness. Jerome rightly took this as a signal to kiss a bit harder, working up to the back of the ear.

“How long are you two going to sit there?” Alistair said. “I know you’re not going to answer me, but if you’re going to start kissing, can you leave?”

The only reason I opened my eyes was because Alistair sounded a little too close. This turned out to be a good call because he was, in fact, standing over us—I mean, right over us. Many people would be put off of a good make-out session by the sight of an angry ghost looming directly overhead, all spiky hair and combat boots. What terrified me, though, was the fact that Alistair was just about an inch or so away from my foot. I immediately yanked my legs away from him. In the process, I very nearly kneed Jerome in the groin, but he reflexively tucked and covered the way guys do.

“What is the matter with you?” Alistair said.

It looked like he was going to come even closer to see why I was convulsing.

“Stay back!” I said.

“What?”

Honestly, I have no idea which one of them said it. Could have been either. Could have been both. Alistair backed off a bit, so I achieved my immediate goal of not killing one of my friends. By this point, Jerome had crab-walked back a bit and then scrambled to his feet. He was scanning the aisles and generally looking freaked out. I had just yelled “Stay back!” pretty loudly. Anyone nearby would come and check to make sure I wasn’t being assaulted in the dark of the stacks. It’s one thing to have a girlfriend who gets startled by the automatic lights and then cuddles close to you for a kiss. It’s another thing entirely when said girlfriend curls up like a shrimp in a hot pan when you try to kiss her, nearly nailing you in the nuts in the process. And then to have the aforementioned girlfriend scream “Stay back!” . . .

The moment, to put it as gently as possible, had passed.

“I’m sorry,” Jerome said, and he sounded genuinely alarmed, like he’d hurt me. “I’m sorry, I’m sorry . . .”

“No!” I said, and I forced a smile. “No. No, no. It’s fine. It’s good! It’s fine.”

Alistair folded his arms and watched me try to explain this one away. Jerk. Jerome was keeping toward the wall, in a stance I recognized from goalkeeping—knees slightly bent, arms at the sides and ready. I was the crazy ball that might come flying at his head.

“I . . . didn’t sleep much last night,” I said. “Not at all, actually.” (A massive lie. I’d slept for thirteen hours straight.) “So, I’m like . . . you know how you get? When you don’t sleep? I really did not mean to do that. I just heard a noise and . . . I’m jumpy.”

“I can see that,” he said.

“And hungry! It’s almost time for dinner.”

“I know how you are about dinner.”

“Damn straight,” I replied. “But . . . we’re okay?”

“Of course! I’m sorry if I—”

“You didn’t.”

“I don’t want you to think—”

“I definitely do not think,” I said. And that was the truest thing I’d said in a long time.

“Dinner then,” he said. “Everyone will be excited to see you.”

He relaxed a bit and moved away from the wall. Jerome took my hand. I mean, it was a grip. A grip of relationship. A statement grip. A grip that said, “I got your back. And also we are, like, a thing.” The incident was over. We would laugh about it, if not now, then by later tonight.

“You have the whole campus,” Alistair called as we left. “The whole city. Do you really have to keep coming here to do that? Really?”

The sky was a particularly vibrant shade of purple, almost electric. The spire of the refectory stood out against it, and the stained-glass windows glowed. It had gotten pleasantly crisp out, and there were large quantities of fallen leaves all around. I could hear the clamor of dinner even from outside the building. When we pushed open the heavy wooden door, all the flyers and leaflets on the vestibule bulletin board fluttered. There was another set of doors, internal ones, with diamond-cut panes. Beyond those doors, all of Wexford . . . or at least . . . most of Wexford.

This was it, really. My grand entrance back into Wexford, and it started with the opening of a door, the smell of medium-quality ground beef and floor cleaner. Aside from those things, it really was an impressive place, housed in an old church, made of stone. The setting gave our meals a feeling of importance that my high school cafeteria couldn’t match. Maybe we were eating powdered mashed potatoes and drinking warm juice, but here it seemed like a more important activity. The tables were laid out lengthways, with benches, so I got a side view of dozens of heads as we stepped inside and I made my way past my fellow students.

And . . . no one really seemed to notice. I guess I’d been imagining a general turning, a hush in the room, the single clang of a fork being dropped onto the stone floor.

Nope. Jerome and I just walked in and proceeded to the back of the room, where the trays were. The actual food line was in a small separate room. I got my first welcome from the dinner ladies, specifically Helen, who handled the hot mains.

“Rory!” she said. “You’re back! How are you?”

“Good,” I said. “Fine. I’m . . . fine.”

“Oh, it’s good to see you, love.”

She was joined in a little cheer by the other dinner ladies. When we emerged, heads turned in our direction. I didn’t exactly get a round of applause, but there was a mumbled interest.

“Rory!”

That was Gaenor, from my hall. She was half standing, waving me over. She and Eloise made a space for me that I didn’t quite fit into, but I pressed butt to bench as best I could and turned my tray. Jerome sat on the other side, a few seats down. My hall mates generally swarmed. Even Charlotte poked her big red head over my shoulder just as I was shoveling a particularly drippy chunk of sausage into my mouth.

“Rory.”

I tried to get the fork away from my mouth, but I had already inserted said sausage, so all I could do was accept the weird back-shoulder hug that she gave me. It was quite a long hug too. With something like this, I would have expected a little squeeze—maybe you could count to three, and then it would be over. This hug lingered and settled in, at least ten seconds. This was no handshake hug. This was a contract. A bond. I made haste with my chewing and swallowing.

“Hey, Charlotte,” I said, shrugging loose.

Then I heard the squeal and I knew Jazza had arrived. I turned to see her tearing up the aisle toward us. Jazza always reminded me a little of a golden retriever. I mean that in a good way. Just the way her long hair (which was always bizarrely smooth and shiny) flopped joyfully as she hurried to greet me, the genuine happiness she exuded. She almost flipped me backward off the bench when she embraced me.

“You’re back!” she said. “You’re back, you’re back, you’re back . . .”

And I was.

(#ulink_0e33deb6-a779-50fe-84fa-d6ada83d44d9)

WAS DEAD ASLEEP WHEN MY PHONE BUZZED. I reached out automatically and slapped it silent. Then I grabbed it and held it right in front of my face. It was 1:34, and I had one text message. It read:

Come downstairs -s

I blinked.

Stephen? I wrote back.

The reply, a few seconds later: Yes. Wear shoes.

I knelt on my bed and looked out the window, but I couldn’t see anyone. Just the empty square, the empty sidewalk. Empty London, all tucked in for the night. This emptiness didn’t fill me with confidence. I was in no mood for weird text messages telling me to go outside in the middle of the night, especially when I couldn’t see anyone outside the window.

This didn’t mean I wasn’t going, of course. Because, Stephen.

I got up as silently as I could, grabbed my sneakers from the foot of my bed, plucked my fleece from the hook by my door, and crept out, closing the door quietly behind me. Jazza didn’t stir at all. Downstairs, the hall lights were on, even though no one was around. They used to be off at night. Maybe this was part of the new security plan—always look awake, always look at home, always keep the public areas lit. There was no noise from Claudia’s room as I passed by. I remembered the alarm as I stood by the front door. If I tried to get out, it would go off. Stephen was nodding at me. He held up his thumb in a thumbs-up gesture. I smiled and thumbs-upped back. Then he shook his head no and typed something into his phone.

Open the door.

I can’t open the door, I typed. Alarm go boom.

He shook his head again and typed another message.

Just open it.

I took a deep breath and pushed. The door opened with no fanfare, no screech and flash, no metal bars slamming down. I stepped into the cold night. A great plume of my breath fogged up in front of my face.

I was used to seeing Stephen in his police uniform, but today he was wearing a black sweater and a pair of jeans. He had a scarf thickly knotted around his neck in the way that all English people seemed to tie their scarves (a tie that eluded me no matter how I tried). And although it was very cold, he wore no coat. I think some English people think coats are for the weak.

I’d forgotten just how tall he was, and how worried he always looked. He had very thin and straight black eyebrows that were perpetually pushed slightly toward his nose in a worry wrinkle, like he’d just been told something mildly problematic—not terrible or tragic, just annoying and difficult to fix. He turned this vaguely troubled gaze on me, the newest and most immediate problem.

“Hey,” I said. “You heard I was back, huh?”

My relationship with Stephen had been a strange one from the start. He wasn’t, for many reasons, the most open person. But he was here. I think I’d known he would come. My initial inclination was to grab him around his long, skinny middle and hug him until his head popped off, but Stephen was not really a hugger.

I decided to hug him anyway. He tolerated this reasonably well, though he didn’t reciprocate. I guess I expected a smile or something, but smiling also wasn’t his thing.

“Your roommate,” he replied. “Julianne. Is she asleep? Your lights have been off for a half an hour.”

Nor was conversation, really.

“You’ve been looking at my window for a half an hour?”

“That’s not an answer to my question.”

“She’s asleep,” I said. “At least, she’s quiet. She didn’t say anything when I got up.”

“Would she normally say something?”

“It’s good to see you too,” I said. “They said that’s a really good security system, but not so much, huh?”

“It is quite a good system.”

“So why didn’t it go off?”

“Disarming the alarm system of a school building isn’t exactly the trickiest thing the security services has ever had to do.”

“Security services . . .”

“We should move.”

“What?”

“Come on.”

“But . . .”

He had already slipped a businesslike arm across my back and was ushering me down the cobblestone path and around the corner. Stephen was the only person in the world I would tolerate this kind of thing from, because there was one thing I did know—if he dragged me out of bed and ushered me through the dark, there was a reason. And I would be safe.

There was a red car, and I heard the doors unlock when Stephen pointed the remote at it.

“That’s not a police car,” I said, pointing out the obvious.

“It’s an unmarked vehicle. Get in.”

“Where are we going?”

“Let me explain inside the car.”

There was a figure sitting in the front passenger seat. I recognized the head of white hair at once, and the altogether too young face that went with it. It was Mr. Thorpe, the government official who’d come to visit me in the hospital. The one who told me I was never allowed to say anything.

“What’s he—”

“It’s all right,” Stephen said, opening the back door for me. “Get inside.”

Stephen held the door open until I acquiesced.

“Aurora,” Mr. Thorpe said, turning around. “Good to see you. Sorry to pull you out in the middle of the night like this.”

“What are we doing?” I asked.

“We need to talk.”

Stephen started up the car.

“Where are we going?” I asked.

“Do you enjoy being back?” Thorpe asked.

Thorpe didn’t exactly seem like the kind of person who cared whether or not I was adjusting well to my circumstances, and Stephen was suddenly very focused on his driving.

“It’s okay,” I said. “I just got here. As I guess you know.”

“We do.”

“Why do I feel like my being back has something to do with you?”

“It does have something to do with us,” he said. “But I hope that you’re happy about it.”

“Where are we going?”

“We’re just going to take a short ride,” Thorpe said. “Nothing to be worried about.”

Stephen looked at me through the rearview mirror and gave me a reassuring nod. I wrapped my arms around myself and shivered. He turned up the heat.

The first few turns, I knew basically where we were—in the Wexford neighborhood, going south. Then we were lost in a warren of tight little streets for a few moments, reemerging near King William Street, where the old squad headquarters was, where we’d faced down the Ripper. We turned off that quickly enough and were on a road that ran along the Thames Embankment. We were definitely heading west. West was the way to central London. The black cabs got more numerous, the path along the Thames thicker with trees and impressive buildings, the lights on the opposite bank shinier. I caught sight of the London Eye, glowing brightly in the dark, then we were going right, into the very heart of London.