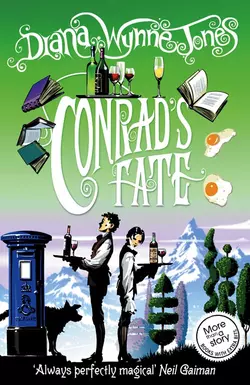

Conrad’s Fate

Diana Wynne Jones

Glorious new rejacket of a Diana Wynne Jones Chrestomanci novel – now a book with extra bits!Conrad is young, good at heart, and yet is apparently suffering from the effects of such bad karma that there is nothing in his future but terrible things. Unless he can alter his circumstances – well, quite frankly, he is DOOMED.Conrad is sent in disguise to Stallery Mansion, to infiltrate the magical fortress that has power over the whole town of Stallchester, and to discover the identity of the person who is affecting his Fate so badly. Then he has to kill that person. But can any plan really be that simple and straightforward? Of course it can't! And things start to go very strangely for Conrad from the moment he meets the boy called Christopher…This is trademark DWJ – packed with laugh-aloud humour, insane logic, spot-on observations, organised chaos, and all wrapped up in a rattling good adventure which oozes magic from every seam. Literally.

Diana Wynne Jones

CONRAD’S FATE

Illustrated by Tim Stevens

Dedication (#ulink_d78c2b78-130e-53b8-b301-199c6732a5af)

To Stella Paskins

Contents

Cover (#u940962fc-8d40-57ab-a919-bfea8d64533d)

Title Page (#ud29cf527-1b99-5e74-9d09-c29c8c6c7d74)

Dedication (#ua46baf45-6198-5593-bf36-36a765aac6f4)

Author’s Preface (#u76404be0-cbcd-548e-8f4c-ae25d3754462)

Chapter One (#u2907db1c-be53-55ed-8a04-ce9c81757d76)

Chapter Two (#ua6ef66d4-6461-5007-a504-80ceb46605da)

Chapter Three (#u19b85855-fb34-57c9-88a9-65804c8880bd)

Chapter Four (#u1622fff4-e1e1-592d-9cb1-774987d998e8)

Chapter Five (#u626a86eb-197a-52b9-a5ef-7984904f0c37)

Chapter Six (#uea4f5dbb-fee2-5068-9577-55c3a1e34017)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Other Works (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Author’s Preface (#ulink_73420d42-9c2f-5b57-ae69-9fd3c83345b6)

This book, and all the other books about Chrestomanci, takes place in a universe made up of many worlds. People living in these worlds have explored them and given them the name “Related Series” on the grounds that the same languages are spoken in each. There are twelve such Series, numbered One to Twelve, and there are usually nine different worlds in each Series, each of which will share the same geography as others of the same number. (For instance, Series Two is a mass of marshy land and rivers, Series Five is all islands, and Series Seven has the worlds where the British Isles have not split off from the continent of Europe).

Chrestomanci himself lives in Series Twelve A, which is like our own world except that magic is common there. Our own world is Twelve B and does not have magic to speak of. A magic user using the proper spells can easily cross from one world to another, which is what Christopher does in this book.

Conrad’s Fate takes place in Series Seven and, although there are in fact thousands of different worlds, none of the others need concern you here.

Diana Wynne Jones

Chapter One (#ulink_950af081-c601-5540-b32b-f520c4d8ca97)

When I was small, I always thought Stallery Mansion was some kind of fairy-tale castle. I could see it from my bedroom window, high in the mountains above Stallchester, flashing with glass and gold when the sun struck it. When I got to the place at last, it wasn’t exactly like a fairy tale.

Stallchester, where we had our shop, is quite high in the mountains too. There are a lot of mountains here in Series Seven and Stallchester is in the English Alps. Most people thought this was the reason why you could only receive television at one end of the town, but my uncle told me it was Stallery doing it.

“It’s the protections they put round the place to stop anyone investigating them,” he said. “The magic blanks out the signal.”

My Uncle Alfred was a magician in his spare time so he knew this sort of thing. Most of the time he made a living for us all by keeping the bookshop at the cathedral end of town. He was a skinny, worrity little man with a bald patch under his curls and he was my mother’s half-brother. It always seemed a great burden to him, having to look after me and my mother and my sister Anthea. He rushed about muttering, “And how do I find the money, Conrad, with the book trade so slow!”

The bookshop was in our name too – it said GRANT AND TESDINIC in faded gold letters over the bow windows and the dark green door – but Uncle Alfred explained that it belonged to him now. He and my father had started the shop together. Then, just after I was born and a little before he died, my father had needed a lot of money suddenly, Uncle Alfred told me, and he sold his half of the bookshop to Uncle Alfred. Then my father died and Uncle Alfred had to support us.

“And so he should do,” my mother said in her vague way. “We’re the only family he’s got.”

My sister Anthea said she wanted to know what my father had needed the money for, but she never could find out. Uncle Alfred said he didn’t know. “And you never get any sense out of Mother,” Anthea said to me. “She just says things like ‘Life is always a lottery’ and ‘Your father was usually hard up’ – so all I can think is that it must have been gambling debts. The casino’s only just up the road after all.”

I rather liked the idea of my father gambling half a bookshop away. I used to like taking risks myself. When I was eight I borrowed some skis and went down all the steepest and iciest ski runs, and in the summer I went rock climbing. I felt I was really following in my father’s footsteps. Unfortunately, someone saw me halfway up Stall Crag and told my uncle.

“Ah, no, Conrad,” he said, wagging a worried, wrinkled finger at me. “I can’t have you taking these risks.”

“My dad did,” I said, “betting all that money.”

“He lost it,” said my uncle, “and that’s a different matter. I never knew much about his affairs, but I have an idea – a very shrewd idea – that he was robbed by those crooked aristocrats up at Stallery.”

“What?” I said. “You mean Count Rudolf came with a gun and held him up?”

My uncle laughed and rubbed my head. “Nothing so dramatic, Con. They do things quietly and mannerly up at Stallery. They pull the possibilities like gentlemen.”

“How do you mean?” I said.

“I’ll explain when you’re old enough to understand the magic of high finance,” my uncle replied. “Meanwhile…” His face went all withered and serious. “Meanwhile, you can’t afford to go risking your neck on Stall Crag, you really can’t, Con, not with the bad karma you carry.”

“What’s karma?” I asked.

“That’s another thing I’ll explain when you’re older,” my uncle said. “Just don’t let me catch you going rock climbing again, that’s all.”

I sighed. Karma was obviously something very heavy, I thought, if it stopped you climbing rocks. I went to ask my sister Anthea about it. Anthea is nearly ten years older than me and she was very learned even then. She was sitting over a line of open books on the kitchen table, with her long black hair trailing over the page she was writing notes on. “Don’t bother me now, Con,” she said without looking up.

She’s growing up just like Mum! I thought. “But I need to know what karma is.”

“Karma?” Anthea looked up. She has huge dark eyes. She opened them wide to stare at me, wonderingly. “Karma’s sort of like Fate, except it’s to do with what you did in a former life. Suppose that in a life you had before this one you did something bad, or didn’t do something good, then Fate is supposed to catch up with you in this life, unless you put it right by being extra good of course. Understand?”

“Yes,” I said, though I didn’t really. “Do people live more than once then?”

“The magicians say you do,” Anthea answered. “I’m not sure I believe it myself. I mean, how can you check that you had a life before this one? Where did you hear about karma?”

Not wanting to tell her about Stall Crag, I said vaguely, “Oh, I read it somewhere. And what’s pulling the possibilities? That’s another thing I read.”

“It’s something that would take ages to explain and I haven’t time,” Anthea said, bending over her notes again. “You don’t seem to understand that I’m working for an exam that could change my entire life!”

“When are you going to get lunch then?” I asked.

“Isn’t that just my life in a nutshell!” Anthea burst out. “I do all the work round here and help in the shop twice a week, and nobody even considers that I might want to do something different! Go away!”

You didn’t mess with Anthea when she got this fierce. I went away and tried to ask Mum instead. I might have known that would be no good.

Mum has this little bare room with creaking floorboards half a floor down from my bedroom, with nothing in it much except dust and stacks of paper. She sits there at a wobbly table, hammering away at her old typewriter, writing books and magazine articles about Women’s Rights. Uncle Alfred had all sorts of smooth new computers down in the back room where Miss Silex works, and he was always on at Mum to change to one as well. But nothing will persuade Mum to change. She says her old machine is much more reliable. This is true. The shop computers went down at least once a week – this, Uncle Alfred said, was because of the activities up at Stallery – but the sound of Mum’s typewriter is a constant hammering, through all four floors of the house.

She looked up as I came in and pushed back a swatch of dark grey hair. Old photos show her looking rather like Anthea, except that her eyes are a light yellow-brown, like mine, but you would never think her anything like Anthea now. She is sort of faded and she always wears what Anthea calls “that horrible mustard coloured suit” and forgets to do her hair. I like that. She’s always the same, like the cathedral, and she always looks over her glasses at me the same way. “Is lunch ready?” she asked me.

“No,” I said. “Anthea’s not even started it.”

“Then come back when it’s ready,” she said, bending to look at the paper sticking up from her typewriter.

“I’ll go when you tell me what pulling the possibilities means,” I said.

“Don’t bother me with things like that,” she said, winding the paper up so that she could read her latest line. “Ask your uncle. It’s only some sort of magicians’ stuff. What do you think of ‘disempowered broodmares’ as a description? Good, eh?”

“Great,” I said. Mum’s books are full of things like that. I’m never sure what they mean. That time I thought a disempowered broodmare was some sort of weak nightmare, and I went away thinking of all her other books, called things like Exploited for Dreams and Disabled Eunuchs. Uncle Alfred had a whole table of them down in the shop. One of my jobs was to dust them, but he almost never sold any, no matter how enticingly I piled them up.

I did lots of jobs in the shop, unpacking books, arranging them, dusting them, and cleaning the floor on the days Mrs Potts’ nerves wouldn’t let her come. Mrs Potts’ nerves were always bad on the days after she had tried to tidy Uncle Alfred’s workroom. The shop, and the whole house, used to echo then with shouts of “I told you just the floor, woman! You’ve ruined that experiment! And you’re lucky not to be a goldfish! Touch it again and you’ll be a goldfish!”

But Mrs Potts, at least once a month, just could not resist stacking everything in neat piles and dusting the chalk marks off the workbench. Then Uncle Alfred would rush up the stairs shouting and the next day Mrs Potts’nerves kept her at home and I would have to clean the shop floor. As a reward for this, I was allowed to read any books I wanted from the children’s shelves.

To be brutally frank with you – which is Uncle Alfred’s favourite phrase – this reward meant nothing to me until about the time I heard about karma and Fate and started wondering what pulling the possibilities meant. Up to then I preferred doing risky things. Or I mostly wanted to go and see friends in the part of town where televisions worked. Reading was even harder work than cleaning the floor. But suddenly one day I discovered the Peter Jenkins books. You must know them – Peter Jenkins and the Thin Teacher, Peter Jenkins and the Headmaster’s Secret and all the others. They’re great. Our shop had a whole row of them, at least twenty, and I set out to read them all.

Well, I had already read about six, and those all kept harking back to another one called Peter Jenkins and the Football Formula that sounded really exciting. So that was the one I wanted to read next.

I finished the floor as quickly as I could. Then, on my way to dust Mum’s books, I stopped by the children’s shelves and looked urgently along the row of shiny red and brown Peter Jenkins books for Peter Jenkins and the Football Formula. The trouble is, all those books look the same. I ran my finger along the row, thinking I’d find the book about seventh along. I knew I’d seen it there. But it wasn’t. The one in about the right place was called Peter Jenkins and the Magic Golfer. I ran my finger right along to the end, and it still wasn’t there, and The Headmaster’s Secret didn’t seem to be there either. Instead, there were three copies of one called Peter Jenkins and the Hidden Horror which I’d never seen before. I took one of those out and flipped through it, and it was almost the same as The Headmaster’s Secret, but not quite – vampire bats instead of a zombie in the cupboard, things like that – and I put it back feeling puzzled and really frustrated.

In the end, I took one at random before I went on to dust Mum’s books. And Mum’s books were different – just slightly – too. They looked the same, with FRANCONIA GRANT in big yellow letters on them, but some of the titles were different. The fat one that used to be called Women in Crisis was still fat, but it was now called The Case for Females, and the thin floppy one was called Mother Wit, instead of Do We Use Intuition? like I remembered.

Just then I heard Uncle Alfred galloping downstairs whistling, on his way to open the shop. “Hey, Uncle Alfred!” I called out. “Have you sold all the Peter Jenkins and the Football Formulas?”

“I don’t think so,” he said, rushing into the shop with his worried look. He hurried along to the children’s shelves, muttering about having to reorder as he changed his glasses over. He peered through them at the row of Peter Jenkins books. He bent to look at the books below and stood on tiptoe to look at the shelves above. Then he backed away looking so angry that I thought Mrs Potts must have tidied the books too. “Would you look at that!” he said disgustedly. “That’s a third of them different! It’s criminal. They went for a big working without even considering the side effects! Go outside and see if the street’s still the same, Conrad.”

I went to the shop door, but as far as I could see, nothing…Oh! The postbox down the road was now bright blue.

“You seel” said my uncle when I told him. “You see what they’re like! All sorts of details will be different now – valuable details – but what do they care? All they think of is money!”

“Who?” I asked. I couldn’t see how anyone could make money by changing books.

He pointed up and sideways with his thumb. “Them. Those bent aristocrats up at Stallery, to be brutally frank with you, Con. They make their money by pulling the possibilities about. They look, and if they see they could get a bigger profit from one of their companies if just one or two things were a little different, then they twist and twitch and pull those one or two things. It doesn’t matter to them that other things change as well. Oh no. And this time they’ve overdone it. Greedy. Wicked. People are going to notice and object if they go on doing this.” He took his glasses off and cleaned them. Beads of angry sweat stood on his forehead. “There’ll be trouble,” he said. “Or so I hope.”

So this was what pulling the possibilities meant. “How do they change things?” I asked.

“By very powerful magic,” said my uncle. “More powerful than you or I can imagine, Conrad. Make no mistake, Count Rudolf and his family are very dangerous people.”

When I finally went up to my room to read my Peter Jenkins book, I looked out of my window first. Because I was at the very top of our house, I could see Stallery as just a glint and a flashing in the place where green hills folded into rocky mountain. I found it hard to believe that anyone in that high, twinkling place could have the power to change a lot of books and the colour of the postboxes down here in Stallchester. I still didn’t understand why they should want to.

“It’s because if you change to a new set of things that might be going to happen,” Anthea explained, looking up from her books, “you change everything just a little. This time,” she added, ruefully turning the pages of her notes, “they seem to have done a big jump and made a big difference. I’ve got notes here on two books that don’t seem to exist any more. No wonder Uncle Alfred’s annoyed.”

We got used to the changes by next day. Sometimes it was hard to remember that postboxes used to be red. Uncle Alfred said that we only remembered anyway because we lived in that part of Stallchester. “To be brutally frank with you,” he said, “half Stallchester thinks postboxes were always blue. So does the rest of the country. The King probably calls them royal blue. Mind games, that’s what it is. Diabolical greed.”

This happened in the glad old days when Anthea was at home. I think Mum and Uncle Alfred thought Anthea would always be at home. That summer, Mum said as usual, “Anthea don’t forget that Conrad needs new school clothes for next term,” and Uncle Alfred was full of plans for expanding the shop once Anthea had left school and could work there full time.

“If I clear out the boxroom opposite my workroom,” he would say, “we can put the office in there. Then we can put books where the office is – maybe build out into the yard.”

Anthea never said much in reply to these plans. She was very quiet and tense for the next month or so. Then she seemed to cheer up. She worked in the shop quite happily all the rest of the summer and, in the early autumn, she took me to buy new clothes just as she had done last year, except that she bought things for herself at the same time. Then, after I had been back at school a month, she left.

She came down to breakfast carrying a small suitcase. “I’m off,” she said. “I start at University tomorrow. I’m catching the nine-twenty to Ludwich, so I’ll say goodbye now and get something to eat on the train.”

“University!” Mum exclaimed. “But you’re not clever enough!”

“You can’t,” said Uncle Alfred. “There’s the shop – and you don’t have any money.”

“I took an exam,” Anthea said, “and I won a scholarship. That gives me enough money if I’m careful.”

“But you can’t!” they both said together. Mum added, “Who’s going to look after Conrad?” and Uncle Alfred said, “Look here, my girl, I was relying on you for the shop.”

“Working for nothing. I know,” Anthea said. “Well, I’m sorry to spoil your plans for me, but I do have a life of my own, you know, and I’ve made arrangements for myself because I knew you’d both stop me if I told you. I’ve looked after all three of you for years. But now Conrad’s old enough to look after himself, I’m going to go and get a life.”

And she went, leaving us all staring. She didn’t come back. She knew Uncle Alfred, you see. Uncle Alfred spent a lot of time in his workroom setting up spells to make sure that when Anthea came home at the end of the University semester she would find herself having to stay with us for good. Anthea guessed he would. She simply sent a postcard to say she was staying with friends and never came near us. She sent me cards and presents for my birthdays, but she never came back to Stallchester for years.

Chapter Two (#ulink_6ad68217-0f7d-59ef-a3e9-bda342c57e11)

Anthea’s going made a dreadful difference, far worse than any change made by Count Rudolf up at Stallery. Mum was in a bad mood for weeks. I’m not sure she ever forgave Anthea.

“So sly!” she kept saying. “So mean and secretive. Don’t you ever be like that, Conrad, and it’s no use expecting me to run after you. I have my work to do.”

Uncle Alfred was tetchy and grumpy for a long time too, but he cheered up after he had set the spells that were supposed to fix Anthea at home once she came back. He took to patting me on the shoulder and saying, “You’re not going to let me down like that, are you, Con?”

Sometimes I answered, “No fear!” but mostly I wriggled a bit and didn’t answer. I missed Anthea horribly for ages. She had been the person I could go to when I had a question to ask, or to get cheered up. If I fell down or cut myself, she had been the one with sticking plaster and soothing words. She used to suggest things for me to do if I was bored. I felt quite lost now she was gone.

I hadn’t realised how many things Anthea did in the house. Luckily, I knew how to work the washing machine, but I was always forgetting to run it and finding I’d no clothes to go to school in. I got into trouble for wearing dirty clothes until I got used to remembering. Mum just went on piling her clothes into the laundry basket as she always had, but Uncle Alfred was particular about his shirts. He had to pay Mrs Potts to iron them for him and he grumbled a lot about how much she charged.

“The ingredients for my experiments cost the earth these days,” he kept saying. “Where do I find the money?”

Anthea had done all the shopping and cooking too, and this was where we all suffered most. For the week after she left we lived on cornflakes, until they ran out. Then Mum tried to solve the problem by ordering two hundred frozen quiches and cramming these into the freezer. You can’t believe how quickly you get tired of eating quiche. And none of us remembered to fetch the next quiche out to thaw. Uncle Alfred was always having to unfreeze them by magic, and this made them soggy and seemed to affect the taste.

“Is there anything else we can eat that might be less squishy and more satisfying?” he asked pathetically. “Think, Fran. You used to cook once.”

“That was when I was being exploited as a female,” Mum retorted. “The quiche people do frozen pizzas too, but you have to order them by the thousand.”

Uncle Alfred shuddered. “I’d rather eat bacon and eggs,” he said sadly.

“Then go out and buy some,” said my mother.

In the end, we settled that Uncle Alfred would do the shopping and I would try to cook what he bought. I fetched books called Simple Cookery and Easy Eating up out of the shop and did my best to do what they told me. I was never very good at it. The food always seemed to turn black and stick to the bottom of the pan, but I usually had enough on top to get by with. We ate a lot of bread, though only Mum got noticeably fatter. Uncle Alfred was naturally skinny and I kept growing. Mum had to take me shopping for new clothes several times a year from then on. It always seemed to happen when she was very busy finishing a book and this made her so unhappy that I tried to make my clothes last as long as I could. I got into trouble at school once or twice for looking like a scarecrow.

We got used to coping by next summer. I suppose that was when it finally became obvious that Anthea was not coming back. I had worked out by Christmas that she had left for good, but it took Mum and Uncle Alfred most of a year.

“She’ll have to come home this summer,” Mum was still saying hopefully in May. “All the Universities shut for months over the summer.”

“Not she,” said Uncle Alfred. “She’s shaken the dust of Stallchester off her feet. And to be brutally frank with you, Fran, I’m not sure I want her back now. Someone that ungrateful would only be a disturbing factor.”

He sighed, dismantled his spell to keep Anthea at home and hired a girl called Daisy Bolger to help in the shop. After that, he was always worrying about how much he had to pay Daisy in order to stop her going to work at the china shop by the cathedral instead. Daisy knew how to get money out of Uncle Alfred much better than I did. Talk about sly! And Daisy always seemed to think I was going to mess up the books when I was in the shop. Once or twice, Count Rudolf up at Stallery worked another big change, and each time Daisy was sure it was me messing the books about. Luckily, Uncle Alfred never believed her.

Uncle Alfred was sorry for me. He would look at me over his glasses in his most worried way and shake his head sadly. “I reckon Anthea going has hit you hardest of all, Con,” he took to saying sadly. “To be brutally frank, I suspect it was your bad karma that caused her to leave.”

“What did I do in my past life?” I asked anxiously.

Uncle Alfred always shook his head at that. “I don’t know what you did, Con. The Lords of Karma alone know that. You could have been a crooked policeman, or a judge that took bribes, or a soldier that ran away, or maybe a traitor to the country – anything! All I know is that you either didn’t do something you should have done, or you did something you shouldn’t. And because of that, a bad Fate is going to keep dogging you.” Then he would hurry away muttering, “Unless we find a way you could expiate your misdeed, I suppose.”

I always felt horrible after these conversations. Something bad almost always happened to me just afterwards. Once I slipped when I was quite high up climbing Stall Crag and scraped the whole front of me raw. Another time I fell downstairs and twisted my ankle, and one other time I cut myself quite badly in the kitchen – blood all over the onions – but the truly nasty part was that, each time, I thought, I deserve this! This is because of my crime in my past life. And I felt horribly guilty and sinful until the scrapes or the ankle or the cut had healed. Then I remembered Anthea saying she didn’t believe people had more than one life, and after that I would feel better.

“Can’t you find out who I was and what I did?” I asked Uncle Alfred, one time after I had been told off by the Headmistress because my clothes were too small. She sent a note home with me about it, but I threw it away because Mum had just started a new book and, anyway, I knew I deserved to be in trouble. “If I knew, I could do something about it.”

“To be brutally frank,” said my uncle, “I fancy you have to be a grown man before you can change your Fate. But I’ll try to find out. I’ll try, Con.” He did experiments in his workroom to find out, but he never seemed to make much headway.

About a year after Anthea left, I got really annoyed with Daisy Bolger, when she tried to stop me looking at the newest Peter Jenkins book. I told her my uncle had said I could, but she just kept saying, “Put it back! You’ll crease it and then I’ll be blamed.”

“Oh, why don’t you go away and work in that china shop!” I said in the end.

She tossed her head angrily. “Fat lot you know! I wouldn’t dream of it. It’s boring. I only say I will to get a decent wage out of your uncle – and he doesn’t pay me half what he could afford, even now.”

“He does,” I said. “He’s always worrying how much you cost.”

“That,” said Daisy, “is because he’s stingy, not because he hasn’t got it. He must be as rich as the Count up at Stallery, almost. This bookshop’s coining money.”

“Is it?” I said.

“I keep the till. I know,” Daisy said. “We’re at the picturesque end of town and we get all the tourists, winter and summer. Ask Miss Silex if you don’t believe me. She does the accounts.”

I was so astonished to hear this that I forgot to be angry and forgot the Peter Jenkins book too. That was no doubt what Daisy intended. She was a very cunning person. But I couldn’t believe she was right, not when Uncle Alfred was always so worried. I began counting the people who came into the shop.

And Daisy was right. Stallchester is a famous beauty spot, full of historic buildings and surrounded by mountains. In summer, we got people to look at the town and play the casino, and hikers who walked in the mountains. In winter, people came to ski. But because we are so high up, we get rain and mist in summer; and in winter there are always times when the snow is not deep enough, or too soft, or coming down in a blizzard, and these are the days when tourists come into the shop in their hundreds. They buy everything, from dictionaries to help with crosswords, to deep books of philosophy, detective stories, biographies, adventure stories and cookery books for self-catering. Some even buy Mum’s books. It only took a few months for me to realise that Uncle Alfred was indeed coining money.

“What does he spend it all on?” I asked Daisy.

“Goodness knows,” she said. “That workroom of his is pretty expensive. And he always buys best vintage port for his Magicians’ Circle. All his clothes are handmade too, you know.”

I almost didn’t believe that either. But when I thought about it, one of the magicians who came to Uncle Alfred’s Magicians’ Circle every Wednesday was Mr Hawkins the tailor, and he often came early with a package of clothes. And I’d helped carry dusty old bottles of port wine upstairs for the meeting, often and often. I just hadn’t realised the stuff was expensive. I was annoyed with Daisy for noticing so much more than I did. But then she was a really cunning person.

You would not believe how artfully Daisy went to work when she wanted more money. She often took as much as two weeks on it – ten days of sighing and grumbling and saying how overworked and hard up she was, followed by another day of saying how the nice woman in the china shop had told her she could come and work there any time. Finally, she would flare up with “That’s it! I’m leaving!” And it worked every time.

Uncle Alfred hates people to leave, I thought. That’s why he let Anthea go to Cathedral School, so she could stay at home and be useful here.

I couldn’t threaten to leave, not yet. You have to stay at school until you are twelve in this country. But I could pretend I was not going to do any more cooking. It didn’t take much pretending, really.

That first time, I went even slower than Daisy. I spent over a fortnight sighing and saying I was sick to my back teeth of cooking. Finally, it was Mum who said, “Really, Conrad, to listen to you, anyone would think we exploited you.”

It was wonderful. I went from simmering to boiling in one breath, and I shouted with real feeling, “You are exploiting me! That’s it! I’m not doing any more cooking ever again!”

Then it was even more wonderful. Uncle Alfred hurried me away to his workroom and pleaded with me. “You know – let’s be brutally frank, Con – your mother’s hopeless with food and I’m worse. But we’ve all got to eat, haven’t we? Be a good boy and reconsider now.”

I looked around at the strange-shaped glass things and shining machinery in the workroom and wondered how much it all cost. “No,” I said sulkily. “Pay someone else to do it.”

He winced. He almost shuddered at the idea. “Suppose I was to offer you a little something to take up as our chef again,” he said cajolingly. “What could I offer you?

I let him cajole for a while. Then I sighed and asked for a bicycle. He agreed like a shot. The bicycle was not so wonderful when it came, because Uncle Alfred only produced one that was second hand, but it made a start. I knew how to do it now.

When winter came, I went into my act again. I refused to cook twice. First I got regular pocket money out of my uncle and then I got skis of my own. In the spring, I did it again and got modelling kits. That summer I got most things I needed. The next autumn I actually made Uncle Alfred give me a good camera. I know this was calculated cunning and quite as bad as Daisy – though I couldn’t help noticing that my friends at school got skis and pocket money as if they had a right to them, and that none of them had to cook for these things, either – but I told myself that my Fate had made me bad and I might as well make use of it.

I stopped the year I was going to be twelve. This was not because I was reformed. It was part of a Plan. You can leave school at twelve, you see, and I knew Uncle Alfred would have thought of that. The rule is that you can go on to an Upper School, but only if your family pays for you. Otherwise you go and find a job. All my friends were going to Upper Schools, most of them to Cathedral like Anthea, but my best friends were going to Stall High. I thought of it as like the school in the Peter Jenkins books. Stall High cost more, but it was supposed to be a terrific place and, best of all, it taught magic. I had set my heart on learning magic with my friends. Living as I did in a house where Uncle Alfred filled the stairway with peculiar smells and the strange buzz of working spells at least once a week, I couldn’t wait to do it too. Besides, Daisy Bolger told me that Uncle Alfred had been to Stall High himself as a boy. How that girl found out these things was something I never knew.

Knowing Uncle Alfred, I knew he would try to keep me at home somehow. He might even be going to sack Daisy and make me work in the shop for nothing. So my Plan was to threaten to stop cooking just near the end of my last term and get him to bribe me with Stall High. If that didn’t work, I thought I would threaten to go and get a job in the lowlands, and then say that I’d stay if I could go to Cathedral School instead.

I worked all this out sitting in my room, staring upwards at Stallery glimmering among the mountains. Stallery always made me wish for all the strange and exciting things that I didn’t seem to have. It made me think that Anthea must have sat in her room making plans in much the same way – except that you couldn’t see Stallery from Anthea’s old room. Mum used it as a paper store now.

Stallery was in the news around then anyway. Count Rudolf died suddenly. People gossiping in the bookshop said he was quite young really, but some diseases took no account of age, did they? “Driven to an early grave,” Mrs Potts said to me. “Mark my words. And the new Count is only twenty-one, they say. His sister’s even younger. They’ll be having to marry soon to preserve the family name. She’ll insist on it.”

Daisy was very interested in weddings. She hunted everywhere for a magazine that might have pictures of the new Count Robert and his sister, Lady Felice. All she found was a newspaper with the announcement of Count Robert’s engagement to Lady Mary Ogworth in it. “Just plain print,” she complained. “No photos.”

“Daisy won’t find pictures,” Mrs Potts told me. “Stallery likes its privacy, it does. They know how to keep the media out of their lives up there. I’ve heard there’s electrical fences all round those grounds, and savage dogs patrolling inside. She won’t want people prying, not she.”

“Who’s she?” I asked.

Mrs Potts paused, kneeling with her back to me on the stairs. “Pass the polish,” she said. “Thanks. She,” she went on, rubbing in polish in a slow, enjoying sort of way, “is the old Countess. She’s got rid of her husband – bothered and nagged him to death, I’ve heard – and now she won’t want anyone to see while she works on the new Count. They say he’s well under her thumb already and bound to be more so, poor boy. She likes all the power, all the money. He’ll marry that girl she’s chosen and then she’ll run the pair of them, you’ll see.”

“She sounds horrible,” I said, fishing for more.

“Oh, she is,” said Mrs Potts. “Used to be on the stage. Caught the old Count by kicking up her legs in a chorus line, I heard. And…”

Unfortunately, Uncle Alfred came rushing upstairs at this point and upset Mrs Potts’ cleaning bucket and Mrs Potts’ nerves along with it. I never got Mrs Potts to gossip about Stallery again. That was my Fate at work there, I thought. But I got a few more hints from Uncle Alfred himself. With his face almost withered with worry, he said to me, “What happens up in Stallery now, eh? It could be even worse. I mention no names, but someone’s very power hungry up there. I dread the next set of changes, Con.”

He was so worried that he telephoned his Magicians’ Circle and they actually met on a Tuesday, which was almost unheard-of. After that, they met on Tuesdays and Wednesdays and I helped carry up twice the number of dusty wine bottles every week.

And those weeks slowly passed, until the dread day arrived when the Headmistress came and gave everyone in the top class a School Leaver’s Form. “Take this home to your parent or guardian,” she said. “Tell them that if they want you to leave school at the end of this term, they must sign Section A. If they want you to go on to an Upper School, then they sign Section B. Get them to sign tonight. I want all these forms back tomorrow without fail.”

I took my form home to the shop, prepared for battle and cunning. I went in through the back yard and straight upstairs to Mum. My plan was to get her to sign Section B before Uncle Alfred even knew I’d got the form.

“What’s this?” Mum said vaguely as I pushed the yellow paper in front of her typewriter.

“School Leaver’s Form,” I explained. “If you want me to go on at school you have to sign Section B.”

She pushed her hair back distractedly. “I can’t do that, Conrad, not when you’ve got a job already. And at Stallery of all places. I must say I’m really disappointed in you.”

I felt as if the whole world had been pulled out from under me like a carpet. “Stallery!” I said.

“If that’s what you told your uncle, yes,” my mother said. And she took the form and signed Section A with her married name. F. Tesdinic. “There,” she said. “I wash my hands of you, Conrad.”

Chapter Three (#ulink_bf31604f-27f5-59b5-ac54-9e7f6df5713e)

I stood there, feeling utterly let down. I didn’t know what to do, or what to think. Then, when I next caught up with myself, I was racing downstairs, waving the School Leaver’s Form. I rushed into the shop, where Uncle Alfred was standing behind the pay desk, and I wagged the form furiously in his face.

“What the hell do you mean by this?” I pretty well shrieked at him.

A lot of customers whirled round from the shelves and stared at me. Uncle Alfred looked at them, blinked at me and said to Daisy, “Do you mind taking over here for a moment?” He dodged out from behind the desk and seized my elbow. “Come up to my workroom and let me explain.”

He more or less dragged me from the shop. I was still flapping the form with my free hand and I think I was shouting too. “What do you mean – explain?” I screamed as we went upstairs. “You can’t do this to me! You’ve no right!”

When we reached the workroom, Uncle Alfred shoved me inside into a strong smell of recent magic and shut the door behind both of us with a clap. He straightened his glasses, which I had knocked crooked. He was panting and he looked more worried than I had ever seen him, but I didn’t care. I opened my mouth to shout at him again.

“No, don’t, Con,” Uncle Alfred said earnestly. “Please. I’m doing the best I can for you. Honestly. It’s your Fate – this wretched bad karma of yours – that’s the problem, see.”

“What’s that got to do with anything?” I demanded.

“Everything,” he said. “I’ve been doing a lot of divining about you and it’s even worse than I realised. Unless you put right what you did wrong in your previous life – and put it right now – you are going to be horribly and painfully dead before the year’s out.”

“What?” I said. “I don’t believe you!”

“It’s true,” he assured me. “The Lords of Karma will just scrap you and let you try again when you next get reborn. They’re quite ruthless, you know. But I don’t ask you to believe me just like that. I’d like you to come to the Magicians’ Circle this evening and see what they say. They don’t know you, I haven’t told them about you, but I’m willing to bet they’ll spot this karma of yours straight off. To be brutally frank with you, it’s round you in a black cloud these days, Con.”

I felt terrible. My mouth went dry and my stomach shook, in wobbly waves. “But,” I said, and found my voice had gone down to a whisper, “but what’s it got to do with this?” I tried to flourish the Leaver’s Form at him again, but I could only manage a feeble flap. My arm had gone weak.

“Ah, I wish you’d come to me first,” said my uncle. “I’d have explained. You see, I’ve discovered what you did wrong. There was someone in your last life the Lords of Karma required you to put an end to. And you didn’t. You lost your nerve and let them go free. And this person got reborn and continued his evil ways in this present life too…”

“But I still don’t see—” I began.

He held up a hand to stop me. It was shaking. He seemed to be shaking with worry all over. “Let me finish, Con. Let me go on. Since I discovered what caused your Fate, I’ve done every kind of divination to find out who this person is that you didn’t put an end to. It’s been really difficult – I don’t have to tell you how the magics up at Stallery interfere with spells down here – but it was pretty definite even so. It’s someone up at Stallery, Con.”

“You mean it’s the new Count?” I said.

“I don’t know,” said my uncle. “It’s one of them up there. Someone up at Stallery has a lot of power and is doing something really bad, and they’ve got the exact pattern of this person you should have done away with last time. That’s all I can find out, Con. Look on the bright side. We know where to find him or her. That’s why I arranged for you to get a job up at Stallery.”

“What kind of a job?” I asked.

“Domestic,” said Uncle Alfred. “The kind of thing you’re used to really. The steward up there – butler, whatever – is a Mr Amos and he’s reckoning to take on some school leavers shortly, to train up as servants to the new Count. Day after the end of term, he’ll be interviewing a whole bunch of you. And he’ll take you, Con, never fear. I’ll put a really good spell on you so he’ll have no choice. You don’t need to worry about getting the job. And you’ll be right in the middle of things then, cleaning boots and running errands, and you’ll have ample opportunity to seek out the person responsible for this terrible karma you carry…”

I thought, Cleaning boots! And nearly burst into tears. My uncle went on talking, nervously, persuasively, but I just couldn’t attend any more. It wasn’t simply that my careful Plan had been no use at all. It was more that I suddenly saw where the Plan had been leading me. I hadn’t admitted it to myself before, but I knew now – I knew very fiercely – that what I wanted was to be like Anthea, to leave the bookshop, leave Stallchester, go somewhere quite different and make a career of some kind. I hadn’t actually thought what career, until then, but now I thought of flying an aircraft, becoming a great surgeon, being a famous scientist, or perhaps, best of all, learning to be the strongest magician in the world.

It was like peeping past a door that was just slamming in my face. I could do so many interesting things if I had the right education. Instead, I was going to spend my life cleaning boots.

“I don’t want to!” I blurted out. “I want to go to Stall High!”

“You haven’t listened to what I’ve been telling you,” Uncle Alfred said. “You’ve got to get this evil Fate of yours cleared away first, Con. If you don’t, you’ll die in agony before the year’s out. Once you’ve gone up to Stallery, found out who this person is and done away with him or her, then you can do anything you want. I’ll arrange for you to go to Stall High then like a shot. Of course I will.”

“Really?” I said.

“Really,” he said.

It was like that door softly swinging open again. True, there was an ugly doorstep in the way labelled Bad Karma, Evil Fate, but I could step over that. I found myself letting out a long, long sigh. “All right,” I said.

Uncle Alfred patted my shoulder. “Good lad. I knew you’d see reason. But I don’t ask you to take my word alone. Come to the Magicians’ Circle tonight and see what they have to say. All right now?” I supposed I was. I nodded. “Then could I get back to the shop?” he said. “Daisy hasn’t the experience yet.”

I nodded again. But as he pushed me out on to the stairs, I had a thought. “Who’s going to do the cooking with me gone?” I asked. I was surprised not to have thought of this before.

“Don’t worry about that,” my uncle said. “We’ll hire Daisy’s mother. Daisy’s always telling me what a good cook her mum is.”

I stumbled away up to my room and stared up at Stallery twinkling out of its fold in the mountains. My mind felt like someone in the dark, stumbling about among huge pieces of furniture with sharp corners on them. I kept barking myself on the corners. No Stall High unless I went and cleaned boots in Stallery – that was one corner. The Lords of Karma scrapped you if you were no good – that was another. A person up there among those glinting windows was so wicked they had to be done away with – that was another—and I had to deal with the person now because I’d been too feeble to do it in my last life – that was yet another. Then I barked my mind on the most important corner of the lot. If I didn’t do this, I’d die. It was this person or me, him or me.

Him or me, I kept saying to myself. Him or me.

Those words were going through my head while I helped Uncle Alfred carry the bottles of port up to his workroom that evening. I had to back into the room because I had two bottles in each hand.

“Dear me,” someone said behind me. “What appalling karma!”

Before I could turn round, someone else said, “My dear Alfred, did you realise that your nephew carries some of the blackest Fate I’ve ever seen?”

All the magicians of the Circle were there, though I hadn’t heard them arrive. Two of them were smoking cigars, filling the workroom with strong blue smoke, which made the place look a different shape and size somehow. Instead of the usual workbench and glass tubes and machinery, there was a circle of comfortable armchairs, each with a little table beside it. There was another table in the middle loaded with bottles, wineglasses and several decanters.

I knew most of the people sitting in the armchairs at least by sight. The one pouring himself a glass of rich red wine was Mr Seuly, the Mayor of Stallchester, who owned the ironworks at the other end of town. He passed the decanter along to Mr Johnson, who owned the ski runs and the hotels. Mr Priddy, beside him, ran the casino. One of those smoking a cigar was Mr Hawkins the tailor and the other was Mr Fellish who owned The Stallchester News. Mr Goodwin, beyond those, owned a big chain of shops in Stallchester. I wasn’t quite sure what the others were called, but I knew the tall one owned all the land round here, and that the fat one ran the trams and buses. And there was Mr Loder the butcher, helping Uncle Alfred uncork bottles and carefully pour wine into decanters. The thick nutty smell of port cut across the smell of cigars.

All these men had shrewd respectable faces and expensive clothes, which made it worse that they were all staring at me with concern. Mayor Seuly sipped at his wine and shook his head a little. “Not long for this life unless something’s done soon,” he said. “What’s causing it? Does anyone know?”

“Something – no, someone he should have put down in his last life, by the looks of it,” Mr Hawkins the tailor said.

The tall land-owning one nodded. “And the chance to cure it now, only he’s not done it,” he said, deep and gloomy. “Why hasn’t he?”

Uncle Alfred beckoned me to stop standing staring and put the bottles on the table. “Because,” he said, “to be brutally frank with you, I’ve only just found out who he should be dealing with. It’s someone up at Stallery.”

There was a general groan at this.

“Then send him there,” said Mr Fellish.

“I am. He’s going next week,” my uncle said. “It couldn’t be contrived any sooner.”

“Good. Better late than never,” Mayor Seuly said.

“You know,” observed Mr Priddy, “it doesn’t surprise me at all that it’s someone up at Stallery. That’s such a strong Fate on the boy. It looks equal to the power up there – and that’s so strong that it interferes with communications and stops this town thriving as it should.”

“It’s not just this town Stallery interferes with,” Mayor Seuly said. “Their financial grip is down over the whole world, like a net. I come up against it almost every day. They have magical stoppages occurring all the time, so that they can make money and I can’t. If I try to get round what they do – bang. I lose half my profits.”

“Oh, we’ve all had that,” agreed Mr Goodwin. “Odd to think it’s in this lad’s hands to save us as well as himself.”

I stood by the table, turning from one to the other as they spoke. My mouth went drier with each thing that was said. By this time I was so horrified I could hardly swallow. I tried to ask a question, but I couldn’t.

My uncle seemed to realise what I wanted to know. He turned round. He was holding his glass up to the light, so that a red blob of light from it wavered on his forehead as he said, “This is all very true and tragic, but how is my nephew to know who this person is when he sees him? That’s what you wanted to ask, wasn’t it, Con?” It was, but I couldn’t even nod by then.

“Simple,” said Mayor Seuly. “There’ll come a moment when he’ll know. There’s always a moment of recognition in cases of karma. The person he needs will say something or do something, and it will be like clicking a switch. Light will come on in the boy’s head and he’ll know.”

The rest of them nodded and made growling murmurs that they agreed, it was like that, and Uncle Alfred said, “Got that, Con?”

I managed to nod this time. Then Mayor Seuly said, “But he’ll want to know how to deal with the person when he does know. That’s quite as important. How about he uses Granek’s Equation?”

“Too complicated,” said Mr Goodwin. “Try him with Beaulieu’s Spell.”

“I’d prefer a straight Whitewick,” Mr Loder the butcher said.

After that they all began suggesting things, all of which meant nothing to me, and each of them got quite heated in favour of his own suggestion. Before long, the tall, land-owning one was banging his wineglass on the little table beside his chair and shouting, “You’ve got to have him eliminate this person for good, quickly and simply! The only answer is a Persholt!”

“Please remember,” my uncle said anxiously, “that Con’s only a boy and he doesn’t know any magic at all.”

This caused a silence. “Ah,” Mayor Seuly said at length. “Yes. Of course. Well then, I think the best plan is to enable him to summon a Walker.”

At this, all the others broke into rumbles of “Exactly! Of course! A Walker. Why didn’t we think of that before?”

Mayor Seuly looked round the circle of them and said, “Agreed? Good. Now what can we give him to use? It ought to be something quite plain and ordinary that no one will suspect…Ah. Yes. A cork from one of those bottles will do nicely.”

He held out his hand with a handsome gold ring shining on it and Mr Loder passed him the purple stained cork from the bottle he had just emptied into a decanter. Mr Seuly took it and clasped it in both hands for a moment. Then he nodded and passed it on to Mr Johnson, who did the same. The cork slowly travelled round the entire circle, including Uncle Alfred and Mr Loder standing by the table, who passed it back to the Mayor.

Mayor Seuly held the cork up in his finger and thumb and beckoned me over to him. I still couldn’t speak. I stood there, looking down on his wealthily clipped hair, that almost hid the thin place on top, and wondering at how rounded and rich he looked. I breathed in smells of nutty, fruity wine, smooth good cloth and a tang of aftershave, and nodded at everything he said.

“All you have to do,” he said, “is first to have your moment of recognition and then to fetch out this cork. You hold it up like I’m doing, and you say, ‘I summon a Walker to bring me what I need’ Have you got that?” I nodded. It sounded quite easy to remember. “You may have to wait a while for the Walker,” Mayor Seuly went on, “and you mustn’t be frightened when you see the Walker coming. It may turn out bigger than you expect. When it reaches you, the Walker will give you something. I don’t know what. Walkers are designed to give you exactly the tool for the job. But take my word for it, the object you get will do just what you need it to do. And you must give the Walker this cork in exchange. Walkers never give something for nothing. Have you got all that?” he asked. I nodded again. “Then take this cork and keep it with you all the time,” he said, “but don’t let anyone else see it. And I hope that when we next meet you’ll carry no karma at all.”

As I took the cork – which felt like an ordinary cork to me – Mr Johnson said, “Right. That’s done. Send him off, Alfred, and let’s start the meeting.”

I didn’t really need Uncle Alfred to jerk his head at me to go. I got out as quickly as I could and rushed upstairs to the kitchen for a drink of water. But by the time I got there, my mouth was hardly dry at all. That was odd, but it was such a relief that I hardly wondered about it. I wasn’t even very scared any more, and that was odd too, but I didn’t think of it at the time.

Chapter Four (#ulink_a75acc75-2284-5bf6-9b42-267078f832fd)

I got much more nervous as the week marched on. The worst part was the end of term assembly, when I had to sit on the left side with the school leavers, while all my friends sat across the gangway because they were going to Upper Schools. I felt really left out. And while I sat there, I realised that even when I’d found the karma person and got rid of him, I’d still be a year behind my friends at Stall High. And on my side of the gangway, the boy next to me had got a job at Mayor Seuly’s ironworks and the girl on the other side was going to train as a maid in Mr Goodwin’s house. I still had to get my job.

Then it suddenly hit me that I was going off on my own to a strange place where I wouldn’t know what to do or how to behave – and that was bad enough, without having to find the person causing my evil Fate as well. I tried saying It’s him or me to myself, but that was no help at all. When I got home, I looked out of my window, up at Stallery, and that was terrifying. I realised that I didn’t know the first thing about the place, except that it was full of powerful wizardry and that someone up there was thoroughly wicked. When Uncle Alfred came and took me to his workroom to put the spell on me that would make this Mr Amos give me the job at Stallery, I went very slowly. My legs shook.

The workroom was back to its usual state. There was no sign of the comfortable chairs, or the port wine. Uncle Alfred chalked a circle on the floor and had me stand inside it. Otherwise, the magics were just like ordinary life. I didn’t feel anything particularly, or notice much except a very small buzzing, right at the end. But Uncle Alfred was beaming when he had finished.

“There!” he said. “I defy anyone to refuse to employ you now, Con! It’s tight as a diving suit.”

I went away, shaking with nerves. I was so full of doubts and ignorance that I went and interrupted Mum. She was sitting at her creaky table reading great long sheets of paper, making marks in the margins as she read. “Say whatever it is quickly,” she said, “or I’ll lose my place in these blessed galleys.”

Out of all the things I wanted to know, all I could think of was, “Do I need to take any clothes with me to Stallery tomorrow?”

“Ask your uncle,” Mum said. “You arranged the whole caper with him. And remember to have a bath and wash your hair tonight.”

So I went downstairs, where Uncle Alfred was now unpacking guidebooks out in the back, and I asked him the same question. “And can I take my camera?” I said.

He pulled his lip and thought about it. “To be frank with you, by rights you shouldn’t take anything,” he said. “It’s only supposed to be an interview tomorrow. But of course, if the spell works and you do get the job, you’ll probably start work there straight away. I know they provide the uniforms. But I don’t know about underclothes. Yes, perhaps you ought to take underclothes along. Only don’t make it obvious you expect to be staying. They won’t like that.”

This made me more nervous than ever. I thought the spell had fixed it. After that, I had a short, blissful moment when I thought that if I was dreadfully rude to them in Stallery, they’d throw me out and not give me the job. Then I could go to Stall High next term. But of course that wouldn’t work, because of my evil Fate. I sighed and went to pack.

The tram that went up past Stallery left from the market square at midday. Uncle Alfred walked down there with me. I was in my best clothes and carrying a plastic bag that looked like my lunch. I’d arranged a packet of sandwiches and a bottle of juice artfully on top. Underneath were all my socks and pants wrapped round my camera and the latest Peter Jenkins book – I thought Uncle Alfred could spare me one book from the shop.

The tram was filling up with people when we got to the square.

“You’d better get on or you won’t have a seat,” my uncle said. “Good luck, Con, and I’ll love you and leave you. Oh, and Con,” he said as I started to climb the metal steps into the tram. He beckoned and I came back down. “Something I forgot,” he said. He led me a little way off across the pavement. “You’re to tell Mr Amos that your name is Grant,” he said, “like mine. If you tell them a posh name like Tesdinic they’ll think you’re too grand for the job. So from now on your name is Conrad Grant. Don’t forget, will you?”

“All right,” I said. “Grant.” Somehow this made me feel a whole lot better. It was like having an alias, the way people did in the Peter Jenkins books when they lived adventurous double lives. I began to think of myself as a sort of secret agent. Grant. I grinned and waved quite cheerfully at Uncle Alfred as I climbed back on the tram and bought my ticket. He waved and went bustling off.

About half the people on the tram were girls and boys my own age. Most of them had plastic bags like mine, with lunch in. I thought it was probably an end-of-term outing to Stallstead from one of the other schools in town. The Stallery tram was a single-line loop that went up into the mountains as far as Stallstead and then down into Stallchester again by the ironworks. Stallstead is a really pretty village right up among the green Alps. People go there all summer for cream teas and outings.

Then the tram gave out a clang and started off with a lurch. My heart and stomach gave a lurch too, in the opposite direction, and I stopped thinking about anything except how nervous I was. This is it, I thought. I’m really on my way now. I don’t remember seeing the shops, or the houses, or the suburbs we went past. I only began to notice things when we reached the first of the foothills, among the woods, and the cogs underneath the tram engaged with the cogs in the roadway, clunk, and we went steeply up in jerks, croink, croink, croink.

This woke me up a bit. I stared out at the sunlight splashing on rocks and green trees and thought, in a distracted way, that it was probably quite beautiful. Then it dawned on me that there was none of the chattering and laughing and fooling about on the tram that there usually is on a school outing. All the other kids sat staring quietly out at the woods, just as I was doing.

They can’t all be going to Stallery to be interviewed! I thought. They can’t! But there didn’t seem to be any teachers with them. I clutched at the slightly sticky cork in my pocket and wondered if I would ever get to use it to call a Walker, whatever that was. But I had to call one, or I would be dead. And I realised that if any of these kids got the job instead of me, it would be like a death sentence.

I was really scared. I kept thinking of the way Uncle Alfred had told me not to be too obvious about taking clothes and then to call myself Grant, as if he wasn’t too sure that his spell on me would work, and I was more frightened than I had ever been before. When the tram came out on the next level part, I stared down at the view of Stallchester nestled below, and the blue peaks where the glacier was, and at Stall Crag, and the whole lot went fuzzy with my terror.

It takes the tram well over an hour to get as high as Stallery, cogging up the steep bits, rumbling through rocky cuttings and stopping at lonely inns and solitary pairs of houses on the heights. One or two people got on or off at every stop, but they were all adults. The other children just sat there, like me. Let them all be going to Stallstead! I thought. But I noticed that none of the ones with bags of lunch tried to eat any of it, as if they might be too nervous for food, just as I was. Though they could be saving it to eat in Stallstead, I thought. I hoped they were.

At last we were running on an almost level part, where there were clumps of trees and meadowlands and even a farm on one side. It looked almost like a lowland valley here. But on the other side of the road there was a high dark wall with spikes on top. I knew this was the wall round Stallery and that we were now really high up. I could even feel the magics here, like a very faint fizzing. My heart began banging so hard it almost hurt.

That wall seemed to run for miles, with the road curving alongside it. There was no kind of break in its dark surface, until the tram swung round an even bigger curve and began slowing down. There was a high turreted gateway ahead in the wall, which seemed to be some kind of a house as well – anyway I saw windows in it – and across the road from this gateway, along the verge by the hedge, I was surprised to see some gypsies camping. I noticed a couple of tumbledown-looking caravans, an old grey horse trying to eat the hedge, and a white dog running up and down the verge. I wondered vaguely why they hadn’t been moved on. It seemed unlike Stallery to allow gypsies outside their gates. But I was too nervous to wonder much.

Clang, clang, went the tram, announcing it was stopping.

A man in a brown uniform came to the gate and stood waiting. He was carrying two weird-shaped brown paper parcels. Barometers? I wondered. Clocks? He came over as the tram stopped and handed the parcels to the driver.

“For the clock mender in Stallstead,” he said. Then, as the driver unfolded the doors, the man came right up into the tram. “This is Stallery South Gate,” he said loudly. “Any young persons applying for employment should alight here, please.”

I jumped up. So, to my dismay, did all the other kids. We all crowded towards the door and clattered down the steps into the road, every one of us, and the gatehouse seemed to soar above us. The tram clanged again and whined away along its tracks, leaving us to our fate.

“Follow me,” the man in the brown uniform said, and he turned towards the gate. It was a gateway big enough to have taken the tram, like a huge arched mouth in the towering face of the gatehouse, and it was slowly swinging open to let us through.

Everyone clustered forward then, and I was somehow at the back. My feet lagged. I couldn’t help myself. Behind me, across on the other side of the road, someone called out in a strong, cheerful voice, “Bye then. Thanks for the lift.”

I looked round to see a tall boy swing himself down from the middle caravan – I hadn’t noticed there were three before – and come striding across the road to join the rest of us.

Anyone less likely to climb out of a shabby, broken-down caravan was hard to imagine. He was beautifully dressed in a silk shirt, a blue linen jacket and impeccably creased fawn trousers, and his black hair was crisply cut in a way that I could see was expensive. He seemed older than the rest of us – I thought, fifteen at least – and the only gypsy things about him were the dark, dark eyes in his confident, good-looking face.

My heart sank at the sight of him. If anyone was going to get the job at Stallery, it would be this boy.

The gatekeeper came pushing past the boy and shook his fist at the gypsy encampment. “I warned you!” he shouted. “Clear off!”

Someone on the driving seat of the front caravan shouted back. “Sorry, guvnor! Just going now!”

“Then get going!” yelled the gatekeeper. “Go on. Hop it. Or else!”

Rather to my surprise, all five caravans moved off at once. I hadn’t realised there were so many and, for another thing, I had thought the grey horse was eating the hedge and not hitched up to any of them. I dimly remembered there was a cooking fire too, with an iron pot hanging over it. But I thought I must have been wrong about that when all six carts bumped down into the road, leaving empty grass behind, and set off clattering away in the direction of Stallstead. The white dog, which had been sniffing at the hedge some way down the road, came pelting after them and leapt up and down behind the last caravan. A thin brown arm came out of the back of this caravan and the dog was hauled inside with enormous scramblings. It looked as if the dog had been taken by surprise as much as I had.

The gatekeeper grunted and pushed back among us to the open gate. “Come on through,” he said.

We obediently shuffled forward between the walls of the gatehouse. At the exact moment that I was level with the gate, I felt the magical defences of Stallery cut through me like a buzz saw. It was only a thin line, luckily, but while I crossed it, it was like having my body taken over by a swarm of electric bees. I squeaked. The tall boy, walking beside me, made a small noise like “Oof!” I didn’t notice if any of the others felt it because almost at once we came through under the gatehouse into a huge vista of perfect parkland. We all made little murmurs of pleasure.

There was perfect green rolling lawn wherever you looked, with a ribbon of beautifully kept driveway looping through it among clumps of graceful trees. The greenness rose into hills here and there and the hills were either crowned with trees or they had little white pillared summerhouses on them. And it all went on and on, into the blue distance.

“Where’s the house?” one of the girls asked.

The gatekeeper laughed. “Couple of miles away. Start walking. When you come to the path that goes off to the right, take that and keep walking. When you can see the mansion, take the right-hand path again. Someone will meet you there and show you the rest of the way.”

“Aren’t you coming too then?” the girl asked.

“No,” said the man. “I stay with the gate. Off you go.”

We set off, trudging in a dubious little huddle along the drive, like a lost herd of sheep. We walked until the wall and the gate were out of sight behind two of the green hills, but there was still no sign of the mansion. A certain amount of sighing and shuffling began, particularly among the girls. They were all wearing the kind of shoes that hurt your feet just to look at them, and most of them had the latest fashion in dresses on too, which held their knees together and forced them to take little tripping steps. Some of the boys had come in good suits made of thick cloth. They were far too hot, and one boy who was wearing hand-stitched boots was hobbling worse than the girls.

“I’ve got a blister already,” one of the girls announced. “How much further is it?”

“Do you think it’s some kind of a test?” wondered the boy with the boots.

“Oh, it’s bound to be,” said the tall boy from the gypsy camp. “This drive is designed to lead us round in circles until only the fittest survive. That was a joke,” he added, as almost everyone let out a moan. “Why don’t we all take a rest?” His bright dark eyes travelled over our various plastic bags. “Why don’t we sit on this nice smooth grass and have a picnic?”

This suggestion caused instant dismay. “We can’t!” half of them cried out. “They’re expecting us!” And most of the rest said, “I can’t mess up my good clothes!”

The tall boy stood with his hands in his pockets surveying everyone’s hot, anxious faces. “If they want us that badly,” he said, in a testing kind of way, “they might have had the decency to send a car.”

“Ooh, they wouldn’t do that, not for domestic,” one of the girls said.

The tall boy nodded. “I suppose not.” I had the feeling that, up until then, this boy had not the least notion why we were all here. I could see him digesting the idea. “Still,” he said, “domestic or not, there’s nothing to stop people taking their shoes off and walking on this nice smooth grass, is there? There’s no one who could see.” Faces turned to him with longing. “Go on,” he said. “You can always put them on again when we sight the house.”

More than half of them took his advice. Girls plucked off shoes, boys unlaced tight boots. The tall boy sauntered behind with a pleased but slightly superior smile, watching them scamper barefoot along the smooth verge. Some of the girls hauled their tight skirts up. Boys took off hot jackets.

“That’s better,” he said. He turned to me. “Aren’t you going to?”

“Old shoes,” I said, pointing down at them. “They don’t hurt.” His shoes looked to be handmade. I could see they fitted him like gloves. I felt very suspicious of him. “If you really thought it was a test,” I said, “you’ve made them all fail it.”

He shrugged. “It depends if Stallery wants barefoot parlourmaids and footmen with big hairy toes,” he said, and I could have sworn he looked at me closely then, to see if I thought this was what we all intended to be. His piercing dark eyes travelled on down to my carrier bag. “You couldn’t spare a sandwich, could you? I’m starving. The Travellers only eat when they happen to have some food, and that didn’t seem to happen most of the time I was with them.”

I fished him out one of my sandwiches and another for myself. “You couldn’t have been with the gypsies that long,” I said, “or your clothes would have got creased.”

“You’d be surprised,” he said. “It was nearly a month, actually. Thanks.”

We marched along munching egg and cress, while the driveway unreeled ahead of us and more hills with trees and lacy white buildings came into view, and the other kids ran along ahead of us in a bunch. Most of them were trying to eat sandwiches too, and hang on to coats and shoes and bags while they ate.

“What’s your name?” I said at length.

“Call me Christopher,” he said. “And you?”

“Conrad Te—Grant,” I said, remembering my alias just in time.

“Conrad T Grant?” he said.

“No,” I said. “Just Grant.”

“Very well,” he said. “Grant you shall be. And you aim to be a footman and strut in Stallery in velvet hose, do you, Grant?”

Hose? I thought. I had visions of myself in a reel of rubber pipe. “I don’t know what they dress you in,” I said. “But I do know they can’t be going to take more than one or two.”

“That seems obvious,” Christopher replied. “I regard you as my chief rival, Grant.”

This was so exactly what I thought about him that I was rather shaken. I didn’t answer, and we swung up another loop of drive to find there were now banks of flowers under some of the trees, as if we might be getting near the gardens round the house. Here a dog of some kind came lolloping from the nearest trees and put on speed towards us. It was quite a big dog. The kids on the verge instantly began milling about, yelling out that it was one of the ferocious guard dogs on the loose. A girl screamed. The boy with the hand-stitched boots swung them, ready to throw at the dog.

“Don’t do that, you fool!” Christopher bellowed at him. “Do you want it to go for you?” He set off in great strides up the grass towards the dog. It put on speed and came sort of snaking at him, long and low.

I’m sure the kids were right about that dog. It was snarling as if it wanted to tear Christopher’s throat out, and when it got near, it bunched itself, ready to spring. A girl screamed again.

“Stop that, you fool of a dog,” Christopher said. “Stop it at once.”

And the dog did stop. Not only did it stop, but it wagged its tail and wagged its bunched-up hind parts and came crawling and grovelling towards Christopher, where it tried to lick his beautiful shoes.

“No slobber,” Christopher commanded, and the dog stopped and just grovelled instead. “You’ve made a mistake,” he told it. “No one here’s a trespasser. Go away. Go back where you came from.” He pointed sternly up at the trees. The dog got up and walked slowly back the way it had come, turning round hopefully every so often as it went, in case Christopher was going to let it come and grovel again. Christopher came down the hill saying, “I think it’s trained to go for anyone who isn’t on the path. Shoes on again, everyone, I’m afraid.”

Everyone now regarded him as a sort of hero, saviour and commander. Several girls gave him passionate looks while they put their shoes back on, and we all limped and straggled on round another curve of drive. Here there were hedges, with glimpses of flowers blazing beyond and, beyond that, a twinkle of many windows from behind the trees. A path branched off to the right. Christopher said, “This way, troops,” and led everyone along it.

We went through more parkland, but it was just as well everyone had put their shoes on again, because this path was quite short and soon branched into another, among tall shiny shrubs, where it ended in a flight of stone steps.

The boys hastily put their jackets back on. A youngish man was waiting for us at the top of these steps. He was quite skinny and only an inch or so taller than Christopher. He had a nice, snubby face. But all of us, even Christopher, stared up at him with awe because he was dressed in black velvet knee breeches, with yellow and brown striped stockings below those and black buckled shoes. He wore a matching brown and yellow striped waistcoat over a white shirt, and his fairish hair was long, tied at the back of his neck by a smooth black bow. It was enough to make anyone stare.

Christopher dropped back beside me. “Ah,” he said. “I see a footman or a lackey. But it’s the breeches that seem to be velvet. The hose are striped silk.”

“My name’s Hugo,” the young man said. He smiled at us, very pleasantly. “If you’ll just follow me, I’ll show you where to go. Mr Amos is waiting to interview you in the undercroft.”

Chapter Five (#ulink_12dce9b3-af39-542d-bc31-76eb2f4e93bb)

Every one went quiet and nervous. Even Christopher said nothing more. We all trooped up the steps and, with the young man’s buckled shoes and striped stockings flashing ahead, we followed him through confusing shrubbery paths. By now we were quite near the mansion. We kept getting glimpses of high walls and windows above the bushes, but we only got a real sight of the house when Hugo led us cornerwise to a door in a yard. Just for a moment, there was a space where you could look along the front of the mansion. We all craned sideways.

The place was enormous. There were windows in rows. It seemed to have its main front door halfway up the front wall, with two big stone stairways curving up to it, and all sorts of curlicues and golden things above that, on a heavy piece of roof that hung over the door. There was a fountain jetting down between the two stairways, and a massive circle of drive beyond that.

This was all I had time to see. Hugo led us at a brisk pace into the yard, across it, and in through a large square doorway in the lower part of the house. In no time at all we were crowding into a big wood-lined room where Mr Amos was standing waiting for us.

No one had any doubt who he was. You could tell he was a Stallery servant because he wore a striped waistcoat like Hugo’s, but the rest of his clothes were black, like someone going to a funeral. He had surprisingly small feet in very shiny black shoes. He stood with his hands clasped behind his back, like something blocky that might be going to take root in the floor, his small shiny shoes astride, his blunt, pear-shaped face forward, and he made you feel almost religious awe. The Bishop down in Stallchester was much less awe-inspiring than Mr Amos was – although it was hard to see why. He was the most pear-shaped man I had ever seen. His striped waistcoat rounded in front, his black coat spread at the sides, and his hands had to reach a long way back in order to clasp behind him. His face was rather purple as well as pear-shaped. His lips were quite thick below his wide, flat nose. He was not much taller than me. But you felt that if Mr Amos were to get angry and uproot his small shiny shoes from the floor, the floor would shake and the world with it.

“Thank you, Mr Hugo,” he said. He had a deep, resounding voice. “Now I want you all standing in a line, hands by your sides, and let me look at you.”

We all hastily shuffled into a row. Those of us with plastic bags tried to lean them up against the backs of our legs, out of sight. Mr Amos uprooted himself then, and the floor did shake slightly as he paced along in front of us, looking each of us intently in the face. His eyes were quite as awesome as the rest of him, like stones in his purple face. When he came to me, I tried to stare woodenly above his smooth grey head. This seemed the right way to behave. He smelt a little like Mayor Seuly, only more strongly, of good cloth, fine wine and cigar. When he came to Christopher at the end of the line, he seemed to stare harder at him than at anyone, which worried me quite a lot. Then he turned massively sideways and snapped his fingers.

Instantly two more youngish men dressed like Hugo came into the room and stood looking polite and willing.

“Gregor,” Mr Amos said to one, “take these two boys and this girl to be interviewed by Chef. Andrew, these boys are to see Mr Avenloch. Take them to the conservatory, please. Mr Hugo, all the rest of the girls will see Mrs Baldock in the Housekeeper’s Room.”