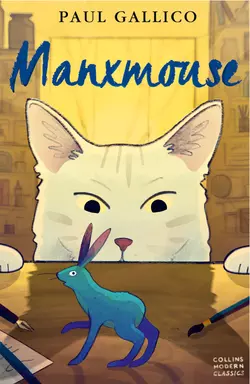

Manxmouse

Paul Gallico

The brave little Manxmouse is one-of -a-kind creature on a special journey. But everyone knows who awaits him, for the Manxmouse belongs to the Manx Cat…The Manxmouse is one-of-a-kind. He’s the strangest little mouse you’ll ever see, with bright blue fur, huge rabbit ears and a distinct lack of tail. But Manxmouse doesn’t mind being different.He knows that destiny awaits him, and so Manxmouse sets out on an exciting adventure. He meets tigers and hawks and dastardly pet-shop owners, but there’s someone he dreads and desires to meet more than anyone else. The someone who has been waiting for him all along… the Manx Cat.

First published by William Heinemann Ltd in 1968

Published in paperback by Pan Books Ltd in 1972

This edition published by HarperCollins Children’s Books in 2017

HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd,

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

The HarperCollins Children’s Books website address is

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Text copyright © Paul Gallico 1968

Why You’ll Love This Book copyright © Michael Bond 2012

Cover design © HarperCollins Publishers 2017

Cover illustration © Jarom Vogel 2017

Paul Gallico asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007457311

Ebook Edition © 2017 ISBN: 9780007457328

Version: 2017-03-02

For Grace

Contents

Cover (#u93ec50bd-3ba4-5510-b5ac-265933a1efff)

Title Page (#ua7d9036b-1fb3-5ea1-9ff1-1baf471c6e5b)

Copyright (#u6e14fd4a-0b60-5496-913e-aa1f8cfa0412)

Dedication (#u44b28a34-2fe0-517c-9863-e1fc111c4fbd)

Why You’ll Love This Book by Michael Bond

1 – The Story of the Tiddly Mouse-Maker

2 – The Story of Manxmouse and the Clutterbumph

3 – The Story of the Happenings in Nasty

4 – The Story of Manxmouse and Pilot Captain Hawk

5 – The Story of the Great Bumbleton Mouse Hunt

6 – The Story of Nervous Nelly

7 – The Story of Wendy H. Troy

8 – The Story of the Terrified Tiger

9 – The Story of the Greedy Pet Shop Proprietor

10 – The Story of the Marvellous Manx Mouse Auction

11 – The Story of Manxmouse Meets Manxmouse

12 – The Story of Manxmouse Meets Manx Cat

Keep Reading … (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author

Books by Paul Gallico

About the Publisher

Why You’ll Love This Book by Michael Bond (#u21058572-196f-59cf-878d-0ffb57cf7eab)

There are untold millions of mice in the world. They come in all shapes and sizes, colours and nationalities. There are Japanese Waltzing Mice, Frizzie Mice with curly whiskers, Singing Mice, pink Hairless Mice, Chocolate coloured Mice, Long Haired Mice, Mice from the Himalayas and Siam …

And then there are mice that can be found in a small shop in the tiny village of Buntingdowndale in the heart of England. They come in a choice of colours; brown, green or white, and they all have pink ears. But they lack one important item.

That’s because they are made by an elderly ceramist whose life’s work is to fashion them out of a mixture of various clays from Scandinavia and loam taken from the banks of Deedle, a brook that meanders through the village.

Baked in an oven overnight, they are very brittle, which is why he doesn’t give them a tail, for fear it might break off and spoil his creation.

And therein lies the rub: the old gentleman is a perfectionist and his dream is to one day make a Super-mouse. A mouse which is like no other.

Does he achieve his dream? Well, in the hands of Paul Gallico he has certainly inspired a delightful story, head and shoulders above the rest. So read on …

By any standards you will find Manxmouse to be a very special character indeed, and the book itself is unputdownable.

Michael Bond

Michael Bond began writing the stories about a bear called Paddington in 1958 while working as a cameraman for BBC television. They are loved the world over and have been translated into more than 30 languages. The 50th Anniversary novel Paddington Here and Now was shortlisted for the inaugural Roald Dahl Funny Prize. 2014 saw the publication of a new title, Love from Paddington, as well as the movie adaptation.

In 1997 Michael was awarded the OBE for services to children’s literature, and in 2007 he received the honorary degree of Doctor of Letters from Reading University. He lives in London with his wife, Sue.

Chapter One (#u21058572-196f-59cf-878d-0ffb57cf7eab)

THE STORY OF THE TIDDLY MOUSE-MAKER (#u21058572-196f-59cf-878d-0ffb57cf7eab)

There was once rather an extraordinary old ceramist who lived in the village of Buntingdowndale in the heart of England. Ceramics is the art of making pottery into tiles, or dishes, or small glazed figures.

What was unusual about him was that he only made mice. And they were not the ordinary kind either. Other potters in the village, and there were several, turned out birds or dogs, kittens or rabbits and many different kinds of animal, but this one made nothing but the most lifelike and enchanting little ceramic mice from morning until night.

He was a happy fellow who hummed to himself contentedly throughout the day as, with his clever fingers, he modelled mouse after mouse after mouse. In the evening he would put those that were dry into a special oven and let them bake overnight. Then the next day he would take them out, polish them, file off the rough edges and look at them lovingly before either setting them in the window of his shop in Buntingdowndale or sending them off up to London.

He probably knew more about mice and their ways than anyone else in the world, so that he was able almost to think like a mouse.

He had come to know them so well because he had mice in his workshop – not in a cage of course, but whole families of them who lived there behind the wainscoting and underneath the wooden floor.

They were quite used to him and since he did not keep a cat, they would come out from their homes and go about their business across the room, or sit up to have a chat together as though he were not there. Sometimes he felt he could almost understand what they were saying. Thus he came to have a great affection for them, copying them in all kinds of poses. He made them as he saw them, coloured brown, grey or white, but their ears were always of a delicate pink and nearly transparent.

But just because he was so fond of them and so knowledgeable, he was never wholly satisfied with the results of his work. Something he felt each time escaped him – some attitude of the body, or expression of their faces. Oh, he made them look worried all right, since he knew that no sensible mouse ever relaxed entirely, even when there was no cat in the house. For there were other things to upset them: terriers, birds of prey, not to mention stoats, weasels and foxes. Then there were traps set by people, and the everyday business of seeking out a living for their families and themselves.

And so the old gentleman’s mice always seemed to be peering slightly nervously over their shoulders. Yet he felt that there was something about mousedom that he had failed to capture. But every time he set about his work, he was hoping that this next one would result in the absolutely faultless or super mouse.

So the days passed; people came from far and near to buy his figures, for they thought them perfect. But the ceramist was beginning to wonder whether before it came his time to pass on, he would ever be able to make a completely one-hundred-per-cent, satisfying reproduction.

And then, out of the blue, something happened. Sometimes when one has had an ambition for a lifetime, worked hard and tried faithfully, one can brew up a magic moment when suddenly all things seem possible. It was not exactly like that with this potter. The strange thing was that the feeling came to him on a day when he had not planned to do any work at all. For there was to be an important wedding of the daughter of friends in Buntingdowndale, and of course he had been invited.

It turned out to be a very happy and gay affair indeed, lasting all day. Beginning with the marriage in the morning there was a large luncheon with many toasts in cider drunk to the bride and groom. After the happy pair had left, it was far too early to go home, so the potter with several of his cronies went to the village inn, The Cat and Mouse. He was particularly welcome there, for he had modelled the sign that hung over the door, in which the mouse was as large as the cat and the two were marching hand-in-hand and smiling cheerfully at one another. This idea, naturally, was quite absurd but it was so amusing and charmingly done that it had resulted in making the inn rather famous.

There, without regard to the clock, or the call of other duties, the friends continued to raise their glasses to the health and future happiness of the married couple, until to their great surprise the inn-keeper was compelled to announce closing time. Thereupon they rose and departed, each to his home in his own manner, with the ceramist finding it easier to float than to walk.

For he was feeling as though he weighed almost nothing, and he was exceptionally happy, joyful and contented.

The village street by lamplight had never looked more beautiful, nor the stars above brighter and it seemed to him that if he wished he could reach up and touch the moon. Some kind of enchantment was at work.

As he turned into the gate of his cottage he thought it was a pity to put such a feeling to bed and to sleep. And so instead of entering the door, he turned off and drifted down the path to his workshop which was at the bottom of the garden. There he switched on the lamps and, light as a feather, settled down at his pottery bench by the bins of different kinds and grades of clay that he used. Before his eyes swam his jars of paints and glazes in all hues, his brushes and his modelling knives. At the far end his electric oven with its knobs, switches and levers appeared to form itself into a face and figure with arms outstretched in invitation.

And thereupon the sensation came over him most intensely and the idea smote him like a stroke of lightning: Now! Now, this very moment, here tonight, this instant, I shall make my super mouse.

At last, at last! Everything that he ever seemed to have known about mice and the making of glazed ceramic figures, came together. And at that particular instant he felt he was the greatest ceramist the world had ever known, and that the mouse that he was about to make would be the most beautiful and perfect that anyone had ever seen.

His coat apparently removed itself without his aid. When he slipped the string of his potter’s apron over his head, it tied itself around his waist. And since his feet no longer needed to touch the ground, it was no effort at all for him to move quickly about his workshop.

He decided to use his favourite mixture – two parts of Copenhagen clay which he imported from Denmark, combined with one part from the banks of the Deedle, the brook that meandered through Buntingdowndale. This he moistened and worked together into a ball. Never had this part of the work gone so well.

With a singing in his heart he reflected upon what a wonderful artist he was and with the picture of this mouse in his mind, he began to model.

It was a sitting-up one upon which he had decided. It would be perched on its hindlegs with its two tiny paws held in front of its breast, clutching the end of its tail which would come winding out from beneath it, up around its side and over one arm.

That night his fingers were so thin and sensitive that he did not need any of his modelling knives, not even to etch the fine whiskers sprouting from its cheeks. For these he used his thumbnail. He was particularly proud of the ears. He knew that when glazed and fired, one would be able almost to see right through them, as he could see through the ears of the live ones who came to visit him.

‘What is art?’ he said to himself, and then answered, ‘Art is creation and I am a creator.’ And he felt even better and happier.

It was the same with the preparation for the painting and glazing. He had only to think about what he wanted and there it was. All his skill, knowledge, cunning and experience were brought into play here. One had to know exactly the right mixture of colours, so that when the clay emerged from the furnace, the heat would have baked it into exactly the proper shades.

This was to be a dark grey mouse when it was finished. He applied the paints lovingly and with care. The tiny upstanding ears would be grey outside and their shells the faintest shade of pink, the colour of the very beginning of dawn. The tail was like the coat, dark grey at the base and growing lighter as it climbed up around the side of the mouse, until it disappeared into the paws of the little animal. The very end was hardly any colour at all, which was a most artistic and lifelike achievement. For, as everyone knows, there is no hair at the tip of a mouse’s tail and this is very difficult to copy. Yet for the ceramist that evening, nothing was impossible. But this was not all that he felt he was accomplishing, merely the making of a purely physical copy of one of his little grey friends from behind the wainscoting. Oh, no! On this very special and extraordinary occasion the ceramist felt that he had hit upon the secret of why his other creations had been failures in his own estimation, and this one was to be a success. It was because he had applied himself too much to the form and not sufficiently to the spirit. And so, concentrating most tremendously upon this master mouse, he tried to instil all the wisdom and knowledge that he himself had accumulated during his lifetime: mouse knowledge, people knowledge, things knowledge.

Of course, although the ceramist knew a great many facts, there was also a good deal he did not, since it is not possible to know everything. But this did not worry him. He was pouring all of himself that there was into the little creature that was so smoothly and beautifully taking shape beneath his fingers.

At last it was finished. He placed his creation upon an already baked tile and stood back to contemplate his handiwork. He could hardly bear to lock it up inside the oven and tear himself away from it. And yet if he wished to see it in its utmost perfection the next morning, delicately coloured and exquisitely glazed, he must of necessity do so.

‘I am indeed a great artist,’ he murmured, highly pleased with himself. He gently lifted up the tile which bore his sculpture and placed it in exactly the right position in the centre of the electric furnace, so that the heat would reach it evenly from all sides.

‘Bake well, my little fellow,’ he said, ‘and tomorrow you will be a masterpiece.’

With this he examined the instruments to see that the temperature was rising properly and the thermostat working, and then, forgetting to switch off the lights in his workshop, he went out into the garden where he performed an impromptu dance of joy in celebration of his accomplishment. It was a good thing that it was so late and the neighbours all abed, for they would have been most astounded had they seen the elderly, bespectacled ceramist leaping and pirouetting about upon the lawn.

When he had finished, he swam up the garden to his house. True, there was no water there, the night still being fine and dry, but at that moment he felt it would be lovely to swim along the path, through the cool grass. And so he did so, around and past his shop into his adjoining home, breast stroking his way up the stairs and right inside his bed, where no sooner did his head touch the pillow than he was instantly asleep. He dreamt that a gold medal was being handed him for creating the finest porcelain mouse ever.

When he awoke the next morning he was not feeling at all as well as he had upon retiring. Far from being able to float, he now seemed anchored to the bed because his head weighed as much as though it were made of lead. He had to put one foot at a time on to the floor and then saw to his amazement that he had not removed his clothes the night before. He wondered whether perhaps he was gravely ill. But then he remembered the wedding and the many glasses of cider that had been lifted, and the continuation of the party afterwards with his chums at The Cat and Mouse. What had occurred after that he did not recollect at all. He splashed cold water on his face, which did not help a great deal, and after drinking a number of cups of coffee, tottered off to his workshop.

To his astonishment he saw the light burning inside and his first thought was, Burglars!

He found the door unlocked which gave him further cause for alarm, and he hurried in to where another surprise awaited him. He observed that his electric oven was turned on to top heat, which was puzzling since he knew he had done no work the day before, but had attended a marriage instead.

Suddenly it began to come back to him, and he murmured, ‘But of course, now I remember! Last night when I came home I made the most beautiful and the finest mouse of my whole life. Now I shall look at him.’

He switched off the oven and when it had cooled sufficiently, threw open the door. With hands that trembled slightly, he seized his pair of tongs and carefully withdrew the supposed mouse masterpiece from the depths of the stove and set it upon his workbench.

And then, with his eyes almost popping from his head and the most terrible sinking feeling in the pit of his stomach, he saw that what he had produced was not only no super creature, but a disaster second to none in the history of ceramics.

In the first place, it was not grey but an utterly mad blue. It had a fat little body like an opossum, hind feet like those of a kangaroo, the front paws of a monkey and instead of delicate and transparent ears, these were long and much like those of a rabbit. And what is more, they were blue too, and violently orange-coloured on the inside.

But the worst thing of all was that it had no tail. The ceramist examined the mouse from every angle and there was none to be seen, although at the back was a small button where one once might have begun. He had either forgotten to make it or, even more horrible thought, had been careless in its production and it had broken off.

Goodness knows, it didn’t look like much of a mouse, what with no tail and rabbit’s ears and wild blue in colour, but still it felt like a mouse and in some curious way was one. But, of course, as a ceramic it was a total failure.

And suddenly the artist threw back his head and began to roar with laughter as he said to himself, ‘Well, I must have had a fine night. After coming here I can’t remember a thing. Certainly no one ought to set about making porcelain mice, or anything else, when one has had several ciders over the eight.’

Now he examined the muddle of his clay and colourings and chemicals on the workbench and laughed even louder. He had used all the wrong materials and colours and had apparently just pulled any old chemicals off the shelf. And, of course, worst of all, he had not waited for it to dry before painting, glazing and baking. It was a wonder that anything at all had resulted from the mess.

One thing was certain, it was not the kind of product that a self-respecting ceramist would want to keep about his studio in case anyone should embarrass him by asking what it was. And so he raised a wooden mallet and was about to bring it down to smash it into dust, when something about the expression of the little creature caused him to stop.

To his surprise he found that the look on the face of the so-called mouse was peculiarly unusual and endearing.

The worry, the fear, the timorousness and feeling of wanting to glance over its shoulder to see whether the cat was around was missing. None of that. What it did have was a combination of interest and excitement with a little shyness and a great deal of sweetness.

If you looked at him from one angle, his face seemed to say, ‘I love you! Please like me.’ And from another, its expression was, ‘I’m such a small mouse, I really don’t matter to anyone. But I’d be happy to help you in any way I could.’

The ceramist laid down his mallet and picked up the porcelain piece which was now cool, and the gentleness and differentness of its face made him smile. Turning it around to the place where its tail should have been, he examined the button and then said, ‘Oh, well, so I’ve made a Manx Mouse.’

He was referring to the fact that the creature had no tail, like the cats from the Isle of Man who, as everybody knows, are tail-less too, and are known as Manx Cats.

The figure looked so absurd that he was forced to smile again. ‘Then I’ll keep you to remind me to say “No thank you” next time I’m invited to have just one more glass.’

In the evening he took the Manx Mouse to his room and put it upon his bedside table where it sat up and regarded him with a mixture of longing and affection, until he put out the light.

Now a strange thing occurred that night, so odd that when the ceramist told it to one of his chums he swore that he had imbibed nothing stronger than a glass of lime and barley water before retiring. For he was not aware that, in spite of the weird results, cider or no cider, all the love and hopes he had poured into the making of this one mouse had called forth the magic of a true creation. And when that has taken place, anything can happen.

Thus it was that he woke up in the dark, or thought he did, with the feeling that the chiming clock in the living-room downstairs was about to strike, which indeed it did. He counted the strokes to know the time and how much longer there was left to sleep. And so he counted: eight, nine, ten, eleven, twelve, thirteen.

Thirteen! But that was absurd. No clock ever struck thirteen, and particularly not his faithful grandfather piece which had been in his family for years.

He had half a mind to get up and go downstairs and see what time it really was, but suddenly found himself drowsy and unable to keep his eyes open any more.

The following morning when he awoke, something even stranger had happened to occupy his attention. The Manx Mouse was no longer on his night table.

At first he thought that he must have knocked it off and so he looked on the floor and even crawled under the bed. But there was nothing there. Then he thought that perhaps it had got mixed up with the bedclothes, so he shook these out most carefully. But there was no Manx Mouse.

He then remembered vaguely what must have been a dream of the clock striking thirteen. This and the disappearance of the blue Manx Mouse was, to say the least, disquieting. He searched his room, looking in every nook and cranny and even in cupboards, bureau drawers and on top of shelves until there was not an inch that he had not inspected. In great perplexity he sat down on the edge of his bed and did not know what to think or where it could have gone, but finally had to give up.

And thus, having played his part, the ceramist now vanishes from our story.

But for Manxmouse, the adventure had just begun.

Chapter Two (#ulink_5d082168-1ab5-549c-b1ad-dc271ce98600)

THE STORY OF MANXMOUSE AND THE CLUTTERBUMPH (#ulink_5d082168-1ab5-549c-b1ad-dc271ce98600)

It was shortly after the stroke of thirteen that Manxmouse realised that he was sitting up on a night table next to a bed, where a mouse really had no business to be.

The moonlight was pouring in through the window, making a pathway to the door which was open.

There was a man asleep in the bed and he was snoring. But he might wake up at any moment and Manxmouse thought he had better go. He slid down one leg of the table quite handily and slipped over to the side of the room for a bit of shadow to think things over for a moment. For although he was certain that he ought to be going, he did not know where to.

It was a most curious feeling not to have been aware of being anywhere a few instants before and then quite suddenly to be not only somewhere, but someone. Perhaps that was what it was like to be born.

From the general shape of things he seemed to be a mouse and indeed, he felt like a mouse and so he must be one. But for the rest, how he had got on to a night table and who, and what, and where he had been when he was not anything or anybody, or even any place for that matter, was too difficult to understand. He did not even know his name, or if he had one. Thinking about it was beginning to give him a headache. If he was going to be on his way, now was the time to do it, before somebody came and shut the door.

He then did a very unmouselike thing. Instead of keeping to the shadows at the side of the room, he marched straight along the lighted path laid down by the moon across the carpet, to the door, climbed the newel post at the top of the stairs and slid down the banisters. He got out of the front door and into the street through the letter-box.

Every single soul in Buntingdowndale must have been asleep. Except for a street lamp, not a light showed anywhere. No one was about and even the houses had their eyes shut with blinds or curtains drawn.

There was a slight breeze blowing, bearing the scent of distant flowers and dew on grass. He thought he would be more comfortable in the country than in the midst of this brick, stone and glass. However, no sooner had he started off when, without warning, he encountered a Clutterbumph on the prowl through the village. It was looking for someone to entertain with a bad dream or a little agreeable terror in the night.

This was somewhat unusual, since it takes two to make a proper Clutterbumph.

For a Clutterbumph is something that is not there until one imagines it. And as it is always someone different who will be doing the imagining, no two Clutterbumphs are ever exactly alike. Whatever it is that frightens one the most and which is just about the worst thing one can think of, that is what a Clutterbumph looks like.

The Clutterbumph usually announces itself with a noise somewhere in the house during the night; a creak in a floorboard or a piece of furniture as it cools after the heat of the day, a drip from a tap, the rattle of a loose shutter, a fly buzzing on a windowpane, something scurrying in the attic, or a cricket caught in the coal cellar.

One could conjure up something with a sheet over it and two eye-holes, sitting on the end of the bed, or an ugly witch with a tall hat and hooked nose on a broomstick. Or perhaps one could imagine something that has too many legs and stingers fore and aft, or a great bear with fiery eyes and long claws and teeth. Or make it a one-eyed, snaggle-toothed giant nineteen feet tall, a dragon, a devil with a pitchfork, or just two googly eyes that keep staring.

The point is that the Clutterbumph cannot exist to frighten anyone unless that somebody thinks of it first and decides what it is going to be like. And when one had finished enjoying being frightened and does not want to be any longer, one simply stops thinking of the Clutterbumph, or falls asleep and it is not there any more.

Since Manxmouse was not imagining anything at the time, this particular Clutterbumph was as yet without any shape or form. In fact it was invisible and in its approach to Manxmouse it had to limit itself to such noises as, ‘Whooooooo!’ and ‘Ha!’ and ‘Grrrr!’ and also, ‘Ho, ho, ho!’ along with ‘Boo!’ or ‘Shoo!’ which last are rather old-fashioned and do not frighten anyone any more.

Although Manxmouse could see no one, he thought he heard somebody speak and so he said, ‘Good evening,’ politely.

The Clutterbumph let out a screech. ‘Whoooeee! Good evening, indeed! We’ll see about how good an evening it is.’ And at this it snarled, growled, howled and roared. It stopped suddenly and in a more natural voice inquired, ‘Look here, aren’t you afraid?’

‘I don’t think so,’ said Manxmouse.

‘Oh, I say,’ said the Clutterbumph in slightly injured tones, ‘that’s not playing the game. You’re bound to be frightened of something: witches, ghosts, demons, dragons, monsters plain or fancy. I’m not particular, and I’ll be glad to oblige. Just think what it is that scares you the most and then I’ll be with you in a jiffy. Perhaps I haven’t introduced myself. I’m a Clutterbumph.’

Manxmouse genuinely wished to oblige the Clutterbumph, whatever it was, but found himself unable to do so. He said, ‘I’m sorry, I really can’t think of anything I’m frightened of.’

‘Come, come!’ said the voice. ‘That’s ridiculous. Not scared? What about dark corners when you never know what’s going to jump out at you? That’s something I do beautifully, by the way. I was first in my class jumping out from dark corners.’

‘Please excuse me,’ Manxmouse apologised, ‘but you see, I haven’t been here for very long and perhaps don’t know how.’ Which was quite true, since the ceramist had forgotten to put fear into him.

The Clutterbumph tried a different tack. He said, ‘Let’s be sensible. You’re a mouse, aren’t you?’

‘I think so,’ said Manxmouse.

‘Well then,’ cried the Clutterbumph triumphantly, ‘you ought to be afraid of Cat. Ha! Wait till you see the kind of cat I can be. Made the Honour Roll for it – glowing eyes, cruel claws, sharp teeth, lashing tail and frightful growl. How about that?’

‘But I’ve never seen a cat,’ Manxmouse said.

‘You’re not being at all co-operative,’ and a plaintive note crept into the voice of the Clutterbumph. ‘Here I am, out on a job, one of the best of us, if I may say so – graduated with honours, with a gold medal for my appearance as a bogey, and I can’t take shape and get on with my work unless you imagine me. Come on, now, there’s a good mouse. Think up something simply awful.’

Manxmouse obviously wished to help and tried very hard, but nothing would come since, as he had already told the Clutterbumph, he had not been there for very long. And the truth is that no one is ever born frightened or fearing anything.

At last, after a period of awkward silence, the Clutterbumph moaned, ‘All right, I give up. Forget about it. I’ve never been so humiliated in my life. What will they say back at the office, when they find out? A Clutterbumph who couldn’t frighten a mouse! Oh dear, oh dear!’

‘Do forgive me,’ said Manxmouse.

The mouse was so plainly distressed, that the Clutterbumph said, ‘That’s all right. I shan’t hold it against you. But if you wouldn’t mind me giving you a little piece of advice …’

‘Oh, no, not at all,’ said Manxmouse. ‘It would be very kind of you.’

‘Well,’ said the Clutterbumph, ‘I see you’re a Manx Mouse.’

Since the Clutterbumph was invisible and, in fact, actually wasn’t there, it was difficult to understand how he could ‘see’ anything. Nevertheless, Manxmouse replied, ‘Am I?’

‘Oh, yes, undoubtedly. Anyone with half an eye, or even with no eyes like myself can see that. Well, my advice is Beware the Manx Cat.’ And with that he flew off into the night with his ‘Grrrrs’ and ‘Booos’ and ‘Arrghs’ growing fainter and finally dying out altogether.

Manxmouse wondered what it was the Clutterbumph had meant, but he was growing tired and so he went on in the direction of the country smells until he came to the edge of Buntingdowndale where the pavement ended.

He walked on for a little while longer, enjoying the feel of grass and leaves and earth and twigs beneath his feet. Just as the moon was beginning to set and the stars to pale, Manxmouse found a soft spot under a hedge, curled up and went to sleep.

When he awoke it was broad daylight. The sun had been shining long enough to dry the dew from the grass and the flowers. It was warm and comfortable. As Manxmouse emerged from under his hedge, he saw that he was at a road junction with an old signpost leaning slightly askew. One fingerboard pointing to the right was marked LITTLE GREAT MUNDEN, and the other pointing to the left was lettered, NASTY. A Billibird perched on top of the signpost, manicuring its fingernails.

A Billibird carries a tail light, can fly backwards as well as forwards and sideways, and knows a great deal about a lot of things, but not everything.

The Billibird stopped doing its nails and said, ‘Hello, a Manx Mouse! Or am I dreaming?’

It was strange, Manxmouse thought, how everyone he encountered seemed to know what he was, when he was not at all sure himself. He knew that he was a mouse, but not that kind of a one. For it must be remembered that as yet he had not seen himself.

‘I was just wondering which way to go,’ Manxmouse said.

‘Well,’ said the Billibird, ‘you have a choice of one or the other. And you needn’t worry, there’s no Manx Cat either way. Little Great Munden has five houses in the Little part and six in the Great part, and its own post office. Nasty has only four houses and the post office is in the kitchen of the last one.’

‘Is there really a place called Nasty?’ asked Manxmouse.

‘Well, it says so, doesn’t it?’ replied the Billibird, indicating the signboard. ‘So I suppose there must be. I know some villages with even funnier names. There’s one called Pity Me and another Come-to-Good. And then there’s the one you ought to know about. It’s called Mousehole, although they pronounce it Mouzle. The villagers try to pronounce Nasty as Naystie, but it’s Nasty all right, and there’s nothing they can do about it.’

‘It must be horrid, then,’ Manxmouse suggested.

‘Oh, no, on the contrary, it’s delightful – timbered houses with thatched roofs, early Elizabethan style, I take it; the most charming gardens and a pretty little pond. Nice people, too. I often go there myself.’

‘Then however did it get that name?’ inquired Manxmouse.

‘Now that is one of the things I don’t know,’ replied the Billibird, ‘and there aren’t many. Someone just called it that, and there it is.’

Manxmouse made up his mind. ‘Then that, I think, is where I shall go for I’m getting hungry.’

‘Mind,’ said the Billibird, ‘there’ll be cats. But they’re well fed and oughtn’t to bother you, except maybe old One-Eye or Street Cat. But of course it’s really Manx Cat you want to watch out for.’

The Billibird resumed its manicuring and as Manxmouse thanked it and went off down the road in the direction of Nasty, he heard it say, ‘I’m not dreaming. I know I’m not. It actually is a Manx Mouse. Poor thing!’

Manxmouse wondered why, ‘Poor thing’? For he was quite happy.

Chapter Three (#ulink_eaa098a8-d159-5534-874b-ca4977c4f16a)

THE STORY OF THE HAPPENINGS IN NASTY (#ulink_eaa098a8-d159-5534-874b-ca4977c4f16a)

Nasty was really exactly as the Billibird had described it: four charming cottages, the dark timbers showing bravely against the white plaster, and the eaves of the roofing thatches descending almost to the windows. The flowers in the gardens were just starting to bud.

The houses stood in a line on one side of the road and the pond the Billibird had mentioned was on the other, a blue patch of water with lily pads and rushes.

It was still early in the morning and no one was about. But the people of Nasty seemed to be the trusting kind, for two of the front doors were open and Manxmouse slipped into the first.

Following the good news told him by the odour in his nostrils, he had no difficulty in finding his way to the kitchen, or in climbing up the leg of the table where he found the remnants of a supper of bread and cheese, and a dish of rice pudding.

Manxmouse was sure nobody would mind, since he was so small that he would not be able to eat a great deal, just sufficient to satisfy his hunger. So he had some of each and it was all delicious.

He was sorry he had no pencil and paper to leave a thank-you note, but he ate very tidily and cleared up the crumbs before he left. Then he slipped down the table leg and was just about to go by the way he had come, when he felt a sudden rush of air and then something soft and furry landed upon him. Two little paws with needle claws gripped him and the next thing he knew, he was held in the tiny but sharp teeth of a kitten and was being carried, still quite unharmed, into the neighbouring ironing room, where House Cat Mother with three more kittens was lying in a basket.

The kitten set Manxmouse down on the floor, put a paw on him and cried with enormous pride, ‘Look, everyone! I’ve caught my first mouse, all alone, by myself! There I was in the kitchen, looking for my ping-pong ball that had rolled under the fridge, when this mouse stepped out from behind the stove and threatened me. But I wasn’t frightened or intimidated, even though there was nobody there to help me. Keeping my head, I gathered myself together, gave two waggles and avoiding the blow he aimed at me, made a tremendous spring, pounced and caught him. He put up a great fight, but I was too much for him. And now I’m going to eat him all by myself.’

Manxmouse was too surprised to protest the exaggeration.

By this time House Cat Mother was up and out of her basket saying, ‘You’ll do nothing of the kind! What on earth have you got there?’

The kitten pressed its paw down harder on Manxmouse’s back. ‘My mouse!’

House Cat Mother came over and said, ‘Why, it’s blue! Can’t you see it’s poisonous! Get away from it, you stupid child!’

‘But he’s mine! I caught him and I want to eat him!’

At this House Cat Mother grew very angry and cuffed the kitten with her paw, knocking it head-over-heels. It gave Manxmouse the opportunity to arise from his undignified position and catch his breath again, for he had been quite squashed.

‘Eat him, you shan’t!’ the mother scolded. ‘How many times have I told you never to touch anything that isn’t the right colour, taste or smell, or all three? Whoever heard of a blue mouse? Can’t you see that this one would make you sick? Honestly, everything I say or try to teach you seems to go in one ear and out the other.’

‘But I’m not poisonous!’ Manxmouse protested. ‘Really I’m not. Please, I promise you, you can eat me with the utmost safety. I didn’t know I was blue, but if I am, I can’t help my colour. It’s quite harmless.’

House Cat Mother drew back from him and said indignantly, ‘Well, I never heard of such a thing. A mouse actually asking to be eaten! That just proves he’s bad and is trying to trap us. Come away at once, children!’ And, herding them together, she rushed them out of the room, leaving Manxmouse rather forlorn.

Was there really something the matter with him? And was it true that he was blue? And if so, what was wrong with that?

He remembered the pond across the road and thought that the thing to do was to go there and have a look at his reflection in it. He had hardly left the door of the cottage and proceeded to the side of the road, when once more there was a rush of air and a pounce, and he was caught up in a pair of powerful jaws.

And this time it wasn’t a kitten but a ginger cat with but a single eye, the one Billibird had called Street Cat, or old One-Eye.

‘Ha! Gotcha!’ growled One-Eye. ‘Thought I’d be sleeping, didn’t you? They all fall for that one. Well, that’s your tough luck. Goodbye, mouse! Some cats start eating at the head of the mouse, but I don’t. I like to start with their tails as an appetizer and work on up, leaving the best part to the last.

And with this he put one great paw on Manxmouse’s head, when he suddenly leaped back with a cry of, ‘What’s this? Why, you haven’t got a tail!’

‘Haven’t I?’ said Manxmouse. ‘I’m sorry, I didn’t know.’

Old One-Eye was upset. ‘You’re a Manx Mouse,’ he said. ‘Why didn’t you say so? You should have told me immediately! Supposing I’d eaten you? You belong to Manx Cat, and Manx Cat would have been furious with me if I’d eaten his mouse.’

Manxmouse said, ‘But I don’t understand! It’s all so confusing! Who and what and where is Manx Cat? And where will I find him?’

Old One-Eye backed away still further, his fur standing up and his tail twitching. ‘Phew!’ he said. ‘That was a narrow escape for me.’ And then, ‘Never you mind. You’ll soon know the answer when you come across him. One thing I can tell you, you’ll never get away from him. Manx Mice are meant to be eaten by Manx Cats. Enjoy yourself while you can.’ And with that old One-Eye slouched off into the gardens behind the houses.

The pond across the street beckoned Manxmouse and he went over to see what he was really like.

It all seemed to be true. The breeze had died away and the surface of the pond was like a mirror as Manxmouse crept down to the edge between two tall rushes and looked in. He was blue and, indeed, had no tail. He turned this way and that to make sure of the latter – there was no mistake about the blue part – and even got himself afloat on a lily pad to be able to see better behind himself. He had just caught a glimpse of the little button where his tail should have been, when a deep voice rumbled, ‘There’s no use in your looking further, youngster, there isn’t one,’ and then it added, ‘Burrp!’

Manxmouse looked around and saw a huge grey-green frog with popping eyes squatting on the bank watching him.

‘That,’ said Manxmouse, now prepared to make the best of things, ‘is because I’m a Manx Mouse.’ For it was clear to him at last that that was what and who he must be, since everyone had been calling him by this name. It had not come as too much of a shock to him. For he thought that the world must be full of Manx Mice like himself and had no idea that he was the only one in existence.

‘Can you swim?’ asked the frog and burped again.

‘I’m not sure,’ replied Manxmouse.

‘Well then, you’d better get back off that lily pad. Manx Cat wouldn’t like it if you were to drown. Burrp! Burrp!’

Manxmouse did as he was told because he didn’t fancy drowning either, and then he said, ‘Just who is this Manx Cat everyone is talking about? And where would I meet him?’

‘Ho, ho!’ rumbled the frog. ‘That’s a good one! The Manx Cat is a cat without a tail, and the first time you see him you’d better start running. Plain cats eat plain mice; Manx Cats eat Manx Mice. There you are, that’s the rule.’

Manxmouse had now managed to creep back on to the shore and was sitting up wiping some droplets of water that had got on to his whiskers, and shaking his feet.

‘You’re certainly the queerest-looking specimen I ever saw,’ commented the frog and added three burps for good measure. ‘No tail, blue all over and as for those ears – oh, burrp!’

Good-natured as Manxmouse was, he was becoming just a little fed up with comments on his shape and colour and so he said, ‘I’m very sorry, but I can’t help how I look. And, for that matter, don’t you think you might appear a little odd yourself, with your eyes sticking out so that they’re practically on top of your head?’

The frog now produced the largest of all his burps and said, ‘Eyes on top of my head, eh? Well, I’ll tell you something, youngster. It might be better for you if yours were, too, because you never know where trouble is coming from next.’ And with that he dived, plop, into the pond and disappeared. It broke up the surface and sent ripples out in every direction. When they washed up on to the shore where Manxmouse was sitting, his image looked very funny and wavy indeed, like standing before one of those crazy mirrors at a fun fair. One moment he was fat and the next lean; his ears long and then short.

Then suddenly the reflection was darkened by a shadow, a great beating of wings, and a splash as something plummeted out of the sky and seized Manxmouse in talons of iron. The next moment he was flying dizzily through the air, with the earth spinning and tumbling about him. Feeling giddy he closed his eyes and did not open them again until there was a bump and he felt himself once more on ground.

He heard a voice say, ‘Now then, we’ll just have a look at what we’ve got here.’

Gazing up, Manxmouse saw the head of an enormous bird with bright yellow eyes and a cruel, curved beak.

Chapter Four (#ulink_e90310ef-8ea2-5308-8654-6479f12bc844)

THE STORY OF MANXMOUSE AND PILOT CAPTAIN HAWK (#ulink_e90310ef-8ea2-5308-8654-6479f12bc844)

Peering down, the bird of prey inspected a creature such as he had never seen before in all his days of hunting from the sky. ‘Hello,’ he said, ‘what on earth are you? No tail, funny feet, ears like a rabbit and blue all over. Are you mole, vole, mouse or shrew?’

Manxmouse, who was being terribly squashed, gasped, ‘If you could just let me go a little, sir, I’d …’

‘Oh, sorry!’ said the hawk, for such it was. ‘Of course! I’d forgotten about my undercarriage. It’s a bit powerful,’ and he relinquished his grip.

Manxmouse sighed with relief and said, ‘I’m a Manx Mouse and everyone says I’m going to be eaten by a Manx Cat. But for a moment I thought I was going to be eaten by you.’

‘Well, I never! Why, it would be a shame to eat you. I’m probably the only hawk who’s ever caught something like you. Nobody would ever believe me. There I was at 3,000 feet, on a nice thermal – you know what a thermal is, don’t you?’

‘No, I don’t,’ Manxmouse admitted. For this was something his creator, the ceramist, would not have known either.

‘Well, it’s an up-current of air caused by heat rising. Catch a good one and you can float on it for hours. I was looking for a meal when I saw that frog. Clever fellow, he was too quick for me. I’d already started my dive – it’s automatic, you know – and then I saw you.’

‘You mean to say,’ Manxmouse queried, amazed, ‘that you can see a tiny thing like me from that high up?’

‘Oh, my goodness, yes,’ exaggerated the bird, who, like most flyers was something of a show-off. ‘Even higher: 5,000 feet – 10,000. We’ve got telescopic eyes. Well, on the way down I thought there was something odd about your colour, you know. It just sort of flashed through my mind. But I was doing about 500 mph – that’s miles per hour – by that time and didn’t bother to use my air brakes. It was as nice a strike as I’ve ever made, even though I did get my tail feathers wet on the pull out. So then when we were climbing again and I saw that you actually were blue, I thought to myself that we’d better have another little look-see. And so here we are, the two of us. Captain Hawk’s the name, Senior Pilot.’

Manxmouse said politely, ‘And I’m very pleased to meet you, Captain.’

‘For that matter,’ Captain Hawk replied, ‘I’m very pleased to meet you as well, I shall be dining out on this for a long time – I don’t mean dining out on YOU,’ Hawk hastened to add, ‘it’s just a phrase and means having something to talk about when you’re invited out to dinner. I shall certainly tell about having caught a Manx Mouse. By the way, young fellow, have you ever flown before?’

‘No, never – except for … just now …’

Captain Hawk laughed, ‘Oh, that! I wouldn’t call that flying. How would you like a little flip? It’s the least I can offer to make amends for having been just a trifle rough with you.’

‘If it wouldn’t be too much trouble,’ said Manxmouse.

‘No, no, not at all! Delighted, old sport! Always pleased to be able to take someone up on his first hop and get him air-minded. Now, climb up and pass along to the front of the aircraft – I mean, get up on to my head, where you’ll find you’ll be able to hang on and it’s quite comfortable. Don’t worry if you feel a trifle dizzy at first, you’ll soon get used to it. And even if you were to fall off – not to worry. I’d catch you before you dropped very far.’

‘Oh, I’m glad of that,’ said Manxmouse.

And with this he boarded the bird at his tail and went along his back to a place just behind his head, where the feathers were rather thinner and he could get a firm grip with his fore paws.

Captain Hawk murmured, ‘Fasten your seat belts, please, and no smoking during take-off.’

‘I beg your pardon,’ said Manxmouse, ‘what was that you said?’

Captain Hawk replied, ‘Regulations. Hang on, now, we’re off!’ With that he gave a great leap upward with his strong legs and with a whoosh and a rush, his two powerful wings began to beat the air. As Manxmouse clung on tightly, the earth began to fall away beneath them, and he had to hold firmly because the ascent was so swift and slightly bumpy.

Hawk’s head seemed to be on a swivel, for he turned it around to Manxmouse, looking over his shoulder and remarked, ‘Take-off on full power. Twin engines, you know. It will be a lot steadier when I throttle back. If you get a funny feeling in your ears, swallow hard. I’m afraid we’re out of sweets on this trip.’

It was all very confusing to Manxmouse, although anybody who has ever been on an airliner knows that the hostesses pass out boiled sweets to enable the passengers to swallow which takes the pressure of the sudden climb from their eardrums. Peering from either side of Hawk’s neck he could secure the most wonderful view.

Not only was the earth continuing to crop away as though it were falling instead of them rising, but everything began to shrink. The buildings which had looked so enormous to Manxmouse were now like dolls’ houses and dwindled until they were even smaller than Manxmouse himself. The roads were but thin lines and cars driving along them looked no bigger than beetles. The pond had diminished to the size of a single drop of water. But at the same time the boundaries of the earth had become enlarged and spread out like a coloured map, with the fields cut into checker-board squares by stone walls and hedges.

Beneath them was the village of Buntingdowndale from where he had come. There was the tiny emerald patch of the village green, the church tower with its flag flying and the criss-cross of streets.

At the same time he could see the road junction like a ‘V’, where he had met the Billibird, though it was no longer possible to make out the signpost. There were four little dots which were now all that was left of the houses of Nasty.

Captain Hawk’s wings were beating with less violence and the passage had become smoother. Whatever dizziness Manxmouse might have experienced at the beginning had passed. He had swallowed dutifully and his ears were no trouble, and he could now give himself up to the enjoyment of what was going on. What fun flying was!

‘We’ve throttled back,’ the Captain remarked. ‘There are some cumulus clouds yonder. We’ll go over and I’ll show you a nice little trick.’

‘What are cumulus clouds?’ Manxmouse asked. Everything was so new and different. He had had some rather shattering experiences while on earth and up here in the sky it was wonderfully quiet and exciting, peaceful and thrilling all at the same time.

‘Those big, white, thundery-looking ones,’ Captain Hawk explained, and indicated a huge mountain of billowy white clouds rising straight up into the air, like packages of cotton wool piled one atop the other. ‘There will be some nice up-draughts. The clouds cool at the top, you see, and the hot air rises from below. They’re what we call “thermals”. You watch – we’ll cut our engines and …’

To Manxmouse’s alarm the great wings on either side of him had stopped and he wondered whether something had gone wrong, or whether the Captain was ill. The stillness was frightening after the whir of their beating. But now, close to the edge of the towering, white clouds, they suddenly shot up into the sky like an express lift in an office building.

‘There,’ Hawk said, ‘isn’t it fun? We can go as high as we like on one of these currents and then glide across to that cloud beyond, miles away, and pick up another. Tremendous saving on fuel, and a nice, smooth ride.’

They rose on the column of warm air. Manxmouse thought what a wonderful thing it must be to be a hawk and be able to live up here in the quiet of the sky.

They went up higher and higher, until at last Captain Hawk wheeled in a wide circle. He said, ‘I mustn’t overdo it. I’m actually not licensed for passengers and so I don’t carry oxygen equipment.’

‘What’s that?’ Manxmouse queried.

‘Oh, of course,’ Captain Hawk explained, ‘since you’ve never flown before you wouldn’t know about that. The further up you go, the thinner the air. People who live on earth begin to feel very funny, and have to have special tanks of oxygen and masks to breathe properly. I don’t, of course, because I’m used to it. My own ceiling is a good deal above this, but I don’t want you to feel uncomfortable. Enjoying yourself?’

‘Marvellously!’ said Manxmouse. Beneath him the landscape of fields and woodlands with silver threads of streams and rivers, small towns and villages was unreeling at dizzying speed as they flew down wind now.

Captain Hawk must have done a great deal of flying close to the big airliners criss-crossing the country, listening to what was being broadcast inside them, for he suddenly said, ‘This is your Captain speaking. We are now cruising at an altitude of 7,000 feet; our air speed is 250 mph and we are overflying St Albans. Hello, there’s a nice looking vole by that hedge. Pity I’m busy.’

‘Can you really see tiny things down there on the ground?’ Manxmouse asked again.

‘Of course. I told you that’s my speciality,’ replied Hawk. ‘There’s a mother rabbit in that field below with six little ones, and a green grass snake just disappearing into some thorn. I see a mouse, but just an ordinary one, not an extraordinary chap like you. And there are three fat trout lazing in that brook we’re just overflying.’

Manxmouse could not even make out the brook, much less any fish in it, and marvelled, ‘I can hardly see anything at all.’

‘Oh, but I’ll wager you’ve got good ears instead,’ Hawk said, and then added, ‘Especially those long, rabbity ones. That’s what you need to hear things coming – particularly things like Manx Cat.’

For the first time Manxmouse felt something like a cold shiver. He had been born without fear and so the Clutterbumph had had no power over him. But the constant repetition of the threat to his life by Manx Cat was beginning to have an effect. He had felt so happy, free, safe and secure up in the blue, but now he was reminded that somewhere below was Manx Cat.

‘We’re approaching central London,’ Hawk said. ‘That river you see winding in and out is the Thames, of course. We are now directly over Buckingham Palace, the Mall and Admiralty Arch. Westminster Abbey and the Houses of Parliament are on your right and that long thing sticking up is Nelson’s column. We’ll turn west now.’

Manxmouse forgot about Manx Cat once more in the fascination of the great grey city beneath, as Hawk banked steeply. He had started his engines again, or rather his wings, and they passed over roof tops, domes, spires and streets down which thousands of cars were crawling.

‘People down there,’ commented Captain Hawk, ‘millions of them – some good, some bad. I avoid them all.’

‘When you’re always on the ground, as I am, I suppose you can’t,’ said Manxmouse.

The ceramist, of course, had known a great deal about people and so Manxmouse too knew what they were.

‘Oh, they won’t bother you if you keep out of their way,’ said the Captain. ‘But every so often if I come down too low, I encounter anti-aircraft fire. Hunters with shotguns.’

At last the grey houses began to thin out and suddenly they came upon a most curious place that seemed to be an enormous field of stone on which sat hundreds of silver birds, but not like Captain Hawk or Billibird, or any others he had seen.

‘London Airport,’ his pilot commented.

‘But what are all those birds down there?’

‘Birds! Ha, ha, ha!’ laughed the Captain. ‘Those are aeroplanes, the things that people fly in. Here comes one now. We’ll have a look at it.’

With a whoosh, a roar and a whine, an enormous four-engined jet passed by overhead to begin its descent, its vast expanse of wings blotting out the sun momentarily, and Manxmouse saw that its tail, instead of being flat like Hawk’s, was as high as two houses, one on top of another.

‘Did you ever see anything so silly?’ Captain Hawk said. ‘They can’t flap their wings; they can’t soar or glide; they make a noise and they smell. And they call that flying!’

At that moment there was another strange noise: ‘Rackety-rackety! Clattery-clattery!’ Something that was a cross between a beetle, a dragonfly and a windmill whirled past them. Hawk had to veer off so sharply that Manxmouse was compelled to cling on for dear life.

‘What is it?’ Manxmouse cried in alarm.

‘Helicopter. Real crazy! I can’t understand what holds it up. The other thing at least has wings, even though they’re not my idea of wings. But that’s only an egg-beater. I don’t often come this way because it’s too dangerous for a bird. I had a friend once who was sucked into one of those jet engines and that was the end of him. But I wanted you to have a look-see.’

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/paul-gallico/manxmouse/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Paul Gallico

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Детская проза

Язык: на английском языке

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: The brave little Manxmouse is one-of -a-kind creature on a special journey. But everyone knows who awaits him, for the Manxmouse belongs to the Manx Cat…The Manxmouse is one-of-a-kind. He’s the strangest little mouse you’ll ever see, with bright blue fur, huge rabbit ears and a distinct lack of tail. But Manxmouse doesn’t mind being different.He knows that destiny awaits him, and so Manxmouse sets out on an exciting adventure. He meets tigers and hawks and dastardly pet-shop owners, but there’s someone he dreads and desires to meet more than anyone else. The someone who has been waiting for him all along… the Manx Cat.