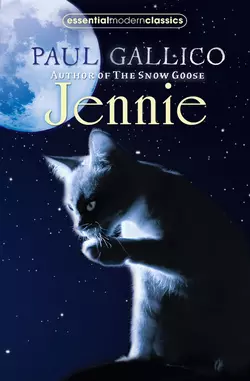

Jennie

Paul Gallico

“If in doubt, wash!”What is it like to be a cat? Find out in this classic animal story from the renowned writer Paul Gallico.Peter Brown longs for a pet cat. One day, he is following a stray cat through the streets when he is knocked down and seriously hurt. On waking, he is astonished to find that he has turned into a cat… The world is a dangerous place for him, but luckily he is rescued and befriended by Jennie, a kindly stray tabby who has been abandoned by her owners. Adventures wait around every corner for the two new friends, as Jennie teaches Peter all about life as a cat.Humorous and touching, and packed with acutely observed feline behaviour, this is a beloved classic that’s essential for any cat-lover.

Copyright (#ulink_98b5cb84-c842-51a1-8d7b-6cf856f26717)

First published in the USA as The Abandoned in 1950

First published in Great Britain by Michael Joseph in 1950

This edition published by HarperCollins Children’s Books in 2016

HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd,

HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

The HarperCollins Children’s Books website address is

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Text copyright © 1950 by Paul Gallico. Copyright renewed 1978 by Virginia Gallico, Robert Gallico and William Gallico

Why You’ll Love This Book copyright © Vivian French 2011

Cover illustration © Chuck Groenik 2016

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd, 2016

Paul Gallico asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007395194

Ebook Edition © 2016 ISBN: 9780007460526

Version: 2018-09-25

To the late Simon of the Amethyst

CONTENTS

Cover (#u8a952d32-ae01-53dc-9970-74f4b4651c08)

Title Page (#u6856886a-b7bc-5c62-90db-af84d6601ba5)

Copyright (#u6373a6ae-917e-54af-a143-97b9a8a529d0)

Dedication (#u6154b7ce-91be-559c-b494-55a3dad21b76)

Why You’ll Love This Book by Vivian French (#u15aa223b-e0b5-5e31-afea-5a049fb6a0ed)

Chapter One – How It Began (#u320d232c-5c1a-55f3-952a-118cf9c5a89b)

Chapter Two – Flight from Cavendish Square (#u69336860-cd74-5537-8c72-c477a9d5a7e1)

Chapter Three – The Emperor’s Bed (#ue82a204f-f4d1-531a-8cbb-77c76ee31dfd)

Chapter Four – A Story is Told (#ua4864f68-004d-5aba-b05c-9c3a07788676)

Chapter Five – When in Doubt – Wash (#u4fc742da-afce-5984-acd6-77971d49f66c)

Chapter Six – Jennie (#udd24a0fc-994b-5e31-b027-b59f80cf0431)

Chapter Seven – Always Pause on the Threshold (#u00bc0951-6ef6-52d2-895c-e7bb86c31199)

Chapter Eight – Hoodwinking of an Old Gentleman (#u946557b2-16be-54a1-be11-1070361174a6)

Chapter Nine – The Stowaways (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten – Price of Two Tickets to Glasgow (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven – The Countess and the Crew (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve – Overboard! (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen – Mr Strachan Furnishes the Proof (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen – Mr Strachan’s Proof Leads to Difficulties (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen – The Killers (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen – Lost in the Clouds (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen – Jennie Makes a Confession (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen – Mr Grims Sleeps (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen – London Once More (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty – The ‘Élite’ of Cavendish Square (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One – Reunion in Cavendish Mews (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two – Jennie Makes a Decision (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three – Lulu – or, Fishface for Short (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Four – The Informers (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Five – The Search (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Six – Jennie, Come Out (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Seven – The Last Fight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Eight – How It All Ended (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading … (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Why You’ll Love This Book by Vivian French (#ulink_13ee8623-b4b3-5f3d-8124-00c62f8167cf)

I can’t remember how old I was when I first read Jennie, but I do remember I couldn’t put it down. I told my friend Alison how brilliant it was and asked her if she wanted to borrow it, but she shook her head. “That’s a story for people who like cats,” she said, “and I like dogs.”

“But it’s a story about a boy called Peter,” I told her. “His mother’s always busy, and his father’s away a lot, and he’s lonely.”

Alison looked more interested. “Does he have adventures?”

“LOADS,” I said. “He gets into fights, and he goes travelling on a ship with an extraordinary crew, and he catches the most enormous rat—”

“YEUCH!”Alison made a face. “Why does he do that?”

“Didn’t I tell you?” I put the book on the table. “He runs after a kitten and gets knocked down by a coal lorry, and when he opens his eyes he discovers he’s a cat … but he doesn’t know how cats behave, so he has to learn. It’s Jennie who teaches him – and they have adventures together.”

Alison picked the book up, and flicked through the pages. “‘When in doubt – any kind of doubt – WASH!’” she read out loud, and laughed. “My brother HATES washing!”

“So did Peter,” I said. “But it’s different for cats. And it tells you why.”

“Is it a teachy book?”Alison looked suspicious. “I mean, does it pretend to be a story, but really it’s so you learn about cats?”

I thought about it. “No,” I said. “It’s much more about a friendship. Sometimes they get things wrong and get cross with each other, but they sort it out. You don’t learn stuff, but you do end up knowing exactly what it’s like being a cat, because of all the detail – like how they stretch and twist and jump, or how they clean themselves, or fight each other. It makes you really and truly feel as if you’ve lived in the world of cats, and understand the way they think. It’s so clever. And it’s funny, too.”

“Who’s your favourite character?”Alison wanted to know.

“Jennie, of course.” I was surprised she’d even asked. “And Captain Sourlies. He’s the captain of the ship they stow away on, and he weighs twenty-two stone, and he hates the sea. And big Angus, with fingers like sausages, who does embroidery. And Mr Grims—”

Alison held up her hand. “Don’t spoil it for me!” Then she turned to the beginning of the book, and started reading … and I never ever got my book back.

I’ve read Jennie lots of times since then (my mum bought me another copy!) and I enjoy it just as much – if not more – each time. These days, I’m sometimes reminded by a phrase or an expression that the book was published in 1950, but the story still grips me. At one point in his life Paul Gallico had twenty-three cats, and he obviously studied them with a real passion; that passion pours into his writing. He was also passionate about people, and the way they interact one with another. Every time I get to the end of the book (even though I’ve read it so often) I have to go and find a hanky. And I know exactly what I’d do if I was a cat, and someone saw me looking just a little bit silly …

I’d wash!

Vivian French

Vivian French is the author of over 200 children’s books, including the hugely popular Tiara Club series. She is also a playwright, storyteller and teacher of creative writing to children and adults.

Poussie, Poussie, Baudrons

“Poussie, poussie, baudrons,

Whaur hae ye been?”

“I’ve been tae London,

Tae see the Queen.”

“Poussie, poussie, baudrons,

Whit gat ye there?”

“I gat a guid fat mousikie,

Rinnin’ up a stair!”

“Poussie, poussie, baudrons,

Whit did ye dae wi’ it?”

“I pit it in ma meal-poke,

Tae eat tae ma breid.”

OLD SCOTTISH NURSERY RHYME

CHAPTER ONE (#ulink_852e80ca-b6f1-5742-ad0c-ea8c1e4ec16e)

How It Began (#ulink_852e80ca-b6f1-5742-ad0c-ea8c1e4ec16e)

PETER GUESSED THAT he must have been hurt in the accident although he could not remember very much from the time he had left the safety of Scotch Nanny’s side and run out across the street to get to the garden in the square, where the tabby striped kitten was warming herself by the railing and washing in the early spring sunshine.

He had wanted to hold and stroke the kitten. Nanny had screamed and there had been a kind of an awful bump, after which it seemed to have turned from day to night as though the sun were gone and it had become quite dark. He ached and somewhere it hurt him, as it had when he had fallen running after a football near a gravel pile and scraped nearly all the skin from the side of one leg.

He seemed to be in bed now, and Nanny was there peering at him in an odd way, that is, first she would be quite close to him, so close that he could see how white her face was, instead of its usual wrinkled pink colour, and then it would seem to fade and become very small like seen through the wrong end of a telescope.

His father and mother were not there, but this did not surprise Peter. His father was a Colonel in the Army, and his mother was always busy and having to dress up to go out, leaving him with Nanny.

Peter might have resented Nanny if he had not been so fond of her, for he knew that at eight he was much too old to be having a nurse who babied him and wanted always to lead him around by the hand as though he were not capable of looking after himself. But he was used by now to his mother being busy and having no time to look after him, or stay in and sit with him at night until he went to sleep. She had come to rely more and more upon Nanny to take her place, and when his father, Colonel Brown, once suggested that it might perhaps be time for Nanny to be leaving, his mother could not bear to think of sending her away, and so of course she had stayed.

If he was in bed, then perhaps he was sick, and if he was sick, perhaps his mother would be with him more when she came home and found out. Maybe now they would even give him the wish he had had for so long and let him have a cat all of his own to keep in his room and sleep curled up at the foot of his bed, and perhaps even crawl under the covers with him and snuggle in his arms on nights that were cold.

He had wanted a cat ever since he could remember, which was many years ago at the age of four – when he had gone to stay on a farm near Gerrards Cross, and had been taken into the kitchen and shown a basketful of kittens, orange and white balls of fluff, and the ginger-coloured mother who beamed with pride until her face was quite as broad as it was long, and licked them over with her tongue one after the other. He was allowed to put his hand on her. She was soft and warm, and a queer kind of throbbing was going on inside of her, which later he learned was called purring, and meant that she was comfortable and happy.

From then on he dearly wished for a cat of his own.

However, he was not allowed to have one.

They lived in a small flat in a Mews off Cavendish Square. Peter’s father, Colonel Brown, who came home occasionally on leave, did not mind if Peter had a cat, but his mother said that there was enough dust and dirt from the street in a small place, and not enough room to move around without having a cat in, and besides, Scotch Nanny didn’t like cats and was afraid of them. It was important to Peter’s mother that Nanny be humoured in the matter of cats, so that she would stay and look after Peter.

All of these things Peter knew and understood and put up with because that was how it was in his world. However, this did not stop his heart from being heavy, because his mother, who was young and beautiful, never seemed to have much time for him, or prevent him yearning hungrily for a cat of his own.

He was friends with all or most of the cats on the Square, the big black one with the white patch on his chest and green eyes as large around as shilling pieces, who belonged to the caretaker of the little garden in Cavendish Square close to the Mews, the two greys who sat unblinking in the window of Number 5 throughout most of the day, the ginger cat with the green eyes who belonged to Mrs Bobbit, the caretaker who lived down in the basement of Number 11, the tortoiseshell cat with the drooping ear next door, and the Boie de Rose Persian who slept on a cushion in the window of Number 27 most of the time, but who was brought into the Square for an airing on clear warm days.

And then of course there were the countless strays who inhabited the alley and the bombed-out house behind the Mews, or squeezed through the railings into the park, tigers and tabbies, black and whites and lemon yellows, tawnies and brindles, slipping in and out behind the dustbins, packets of waste paper, and garbage containers, fighters, yowlers, slinkers, scavengers, homeless waifs, old ’uns, and kittens, going nervously about the difficult business of gaining a living from the harsh and heedless city.

These were the ones that Peter was always dragging home, sometimes kicking and clawing in terror under his arm, or limp and more than willing to go where it was warm and there might be a meal and the friendly touch of a human hand.

Once in a while, when he evaded Nanny, he managed to smuggle one into the cupboard of the nursery and keep it for as much as two whole days and nights before it was discovered.

Then Nanny, who had her orders from Mrs Brown as to what she was to do when a cat was found on the premises, would open the door on to the Mews and cry – “Out! Scat, you dirty thing!” or fetch a broom with which to chase it. Or if that did not work and the stowaway merely cowered in a corner, she would pick it up by the scruff of the neck, hold it away from her, and fling it out into the street. After that, she would punish Peter, though he could not be worse hurt than he was through losing his new friend and remembering how happy it had been safe in his arms.

Peter had even learned not to cry any more when this happened. One could cry inside of one without making a sound, he had found out.

He was feeling that way now that he was sick, only this was different because he seemed to want to cry out this time, but found that he could not utter a sound. He did not know why this should be except it was a part of the queer way things had been since whatever it was had happened to him when he had darted away from Nanny who was talking to the postman, and run across the road after the striped kitten.

Actually, it was a coal lorry that had come speeding around the corner of the Square that had struck Peter and knocked him down just as he had stepped off the kerb without looking and had run in front of it, but what happened after that, the hue and cry, the people that gathered after the accident, Nanny’s crying and wailing, the policeman who picked him up and carried him into the house, the sending for the doctor and the trying to find his mother, and later, the trip to the hospital, Peter was not to know for a long, long time. So many strange things were to happen to him first.

For, unquestionably, events seemed to be taking an odd turn what with night appearing to follow day at such rapid intervals that it was almost like being at the cinema with the screen going all dark and light and Nanny’s face seeming to be on top of him first and then sliding away into the distance only to return once more with the lenses of her spectacles shining like the headlamps of an approaching motor-car.

But that something really queer was about to take place Peter knew when after Nanny had faded into the distance and his bed had seemed to rock like a little boat in the waves and when she had begun to return again, it was no longer the face of Nanny, but that of the tabby striped kitten that had been washing itself by the park railings and that he had wanted to catch and hug.

Indeed, it was this dear little cat now grown to enormous size, sitting at his bedside smiling at him in a friendly manner, its eyes as large as soup tureens, large, luminous, and shiny, and resembling Nanny’s spectacles in that he could see himself mirrored in them.

But what was puzzling to him was that although he knew it to be himself reflected therein, still it did not seem to look like him at all as he was accustomed to seeing himself when he passed the tall cheval mirror in the hallway, or even in Nanny’s glasses in which he could frequently catch a reflection of his curly head of close-cropped auburn hair, round eyes, upturned button nose, stubborn chin, and cheeks as red-and-white and rounded as two crab-apples.

At first Peter did not try to make out exactly who or what he looked like because it was pleasant and soothing just to lose himself in the cool green pools of the kitten’s eyes, so calm and deep and clear that it seemed like swimming about in an emerald lake. It felt delightful to be there bathed in the beautiful colour and surrounded by the warmth of the smile of the kitten.

But then soon he began to notice the effect it was beginning to have upon him.

Sometimes the picture would be hazy and then for a moment it would grow quite clear so that he could see how the shape of his head had altered and not only the shape but the colour. For whereas he was familiar with the reddish-brown curly hair and apple cheeks, his fur now seemed to be quite short, straight and snow white.

“Why,” said Peter to himself, “I said ‘fur’ instead of hair. What a strange thing to do. It must be looking into the cat’s eyes that is changing me into a cat, if that is what is happening.”

But he continued to look there because he found that for the moment he could not take his gaze elsewhere, and when it grew hazy, his image seemed to quiver as though things were happening to it from inside, and each time it grew clear he noted new details, the queerly slanted eyes that were now no longer grey but a light blue, the nose that had changed from an uptilted little sixpenny-bit into a rose-pink triangle leading to a mouth that was no more like his than anything he could think of. It now curved downwards over long, sharp white teeth, and from either side sprouted sets of enormous, bristly white whiskers.

The head was square, the slant-set eyes large and staring, and the sharp-pointed ears stood up like dormers. “Oh,” thought Peter, “that is how I would look if I were a cat. How I wish I were one.” And then he closed his eyes, because this queer, unusual image of himself was now so clear and unmistakable that it was a little frightening. To wish to be a cat was one thing. To seem very much to be one was quite another.

When he opened them, it seemed for a moment as if he had broken the spell of the cat’s-eye mirror, for he was able to avoid staring into it and instead managed to look down at his paws. They were pure white, large and furred, with quaint, soft pinkish pads on the underside and claws curved like Turkish swords and needle-sharp at the end.

To his astonishment, Peter saw that he was no longer lying in the bed, but on top of it. His whole body, now long and slender, was just as soft and white as the ermine muff his mother used to carry when she dressed up and went out in the winter, and what seemed to be a blank and eyeless snake curving, moving, twitching and lashing at the end of it was his own tail. From ear-tip to tail-tip he was clad in spotless white fur.

The tiger-striped kitten, who with his smile and staring eyes had apparently worked this mischief on him, had vanished and was nowhere to be seen. Instead there was only Nanny, ten times larger than she had ever appeared before, standing over the bed shouting in a voice so loud that it hurt his ears –

“Drat the child! He’s dragged in anither stray off the street! Shoo! Scat! Get out!”

Peter cried out – “But, Nanny! I’m Peter. I’m not a cat. Nanny, don’t, please!”

“Rail at me, will ye?” Nanny bellowed. “’Tis the broom I’ll take to ye then.” She ran down the hall, and returned carrying the broom. “Now then. Out ye go!”

Peter was cold with fright. He could only cower down at the end of the bed while Nanny beat at him with the broom, and cry: “Nanny, Nanny, no, no! Oh, Nanny!”

“I’ll miaow you!” Nanny stormed, dropped the broom, and picked Peter up by the scruff of the neck so that he hung there from her hand, front and hind legs kicking, while he cried miserably.

Holding him as far away from her as she could, Nanny ran down the hallway muttering, “And it’s to bed without any supper for Peter when I find him. How often have I told him he’s no’ to bring in any more cats!” until she reached the ground floor entrance to the flat from the Mews.

Then she pitched Peter out into the street and slammed the door shut.

CHAPTER TWO (#ulink_6faa907e-389e-5bd0-a0db-e69ea10dc889)

Flight from Cavendish Square (#ulink_6faa907e-389e-5bd0-a0db-e69ea10dc889)

IT WAS MISERABLY cold and wet out in the Mews, for when the sun had gone down a chill had come into the air, clouds had formed, and it had begun to rain in a heavy, soaking, steady downpour.

Locked outside, Peter let out such a howl of anguish and fright that the woman who lived opposite said to her husband, “Goodness, did you hear that? It sounded just like a child!”

He parted the curtains to look, and Peter cried – or thought he cried to him – “Oh, let me in! Please let me in! Nanny’s put me out, me-out, me-out!”

Peter then heard the husband say as he dropped the curtains: “It’s only another stray, a big white tom. Where do they all come from? You never get a minute’s rest with their yowling and caterwauling. Ah there! Boo! Scat! Go ’way!”

The boy who delivered the evening newspapers came by on his bicycle, and hearing the shouting to scare away the cat outside the door, decided to assist him in the hope of earning a tip.

He rode his bicycle straight at Peter, crying “Oi! Garn! Scat! Get along there!” and then, leaning from the saddle, struck Peter across the back with a folded-up newspaper. Peter ran blindly from this assault, and a moment later, with a roar and a rumble, something enormous and seemingly as big as a house went by on wheels, throwing up a curling wave of muddy water that struck him in the flank as he scampered down the Mews into Cavendish Square, soaking right through his fur to the skin underneath.

He had not yet had time even to look about him and see what kind of a world this was into which he had been so rudely and suddenly catapulted.

It was like none he had ever encountered before, and it struck terror to his heart.

It was a place that seemed to consist wholly of blind feet clad in heavy boots or clicking high heels, and supplied with legs that rose up out of them and vanished into the dark, rainy night above, all rushing hither and thither, unseeing and unheeding. Equally blind but infinitely more dangerous were wheels of enormous size that whizzed, rumbled or thundered by always in twos, one behind the other. To be caught beneath one of those meant to be squashed flatter than the leopard-skin rug in their living-room.

Not that the feet weren’t of sufficient danger to one in the situation in which Peter now found himself, cowering on the wet, glistening pavement of the Square, standing on all fours, and not quite ten inches high. Eyeless, and thus unable to see where they were going, the shoes came slashing and hurtling by from all directions, and no pair at the same pace.

One of them stepped on his tail, and a new and agonising pain he had never felt before shot through Peter and forced an angry and terrified scream from his throat. The foot that had done this performed an odd kind of slithering and sliding dance with its partner for a moment, while down from the darkness above thundered a voice: “Dash the beast! I might have broken my neck over him. Go on! Clear out of here before somebody hurts himself!”

And the partner foot leaped from the pavement and flung itself at Peter’s ribs and shoulders where it landed a numbing blow.

In sheer terror Peter began to run now, without knowing where he was going or what the end was to be.

It seemed as though suddenly all London had become his enemy, and everything that had formerly been so friendly, interesting and exciting, the sounds, the smells, the gleam of lights from the shop windows, the voices of people, and the rush and bustle of traffic in the streets, all added to the panic that began to grip him.

For while he knew that he still thought and felt like and was Peter, yet he was no longer the old Peter he used to know who went about on two legs and was tall enough to be able to reach things down from over the fireplace without standing on tiptoes. Oh no. That Peter was gone and in his place was one who was running on all fours, his ears thrown back and flattened against his head, his tail standing straight out behind him, dashing wildly, hardly looking or knowing where he was going through the rainswept streets of London.

Already he was far from his own neighbourhood or anything that might have looked familiar, and racing now through brightly lighted and crowded thoroughfares, now through pitch-black alleys and crooked lanes. Everything was terrifying to him and filled him with fear.

There was, for instance, the dreadful business of the rain.

When Peter had been a boy, he had loved the rain and had been happiest when he had been out in it. He liked the feel of it on his cheeks and on his hair, the rushing sounds it made tumbling down from the sky, and the cool, soft touch of it as it splashed on to his face and then ran down the end of his nose in little droplets that he could catch and taste by sticking out his lower lip.

But now that he seemed to be a cat, the rain was almost unbearable.

It soaked through his thick fur, leaving it matted and bedraggled, the hairs clinging together in patches so that all their power to give warmth and protection was destroyed and the cold wind that was now lashing the rain against the sides of the shops and houses penetrated easily to his sensitive skin, and in spite of the fact that he was tearing along at top speed he felt chilled to the marrow.

Too, the little pads at the bottom of his feet were thin and picked up the feel of the cold and damp.

He did not know what he was running away from the most – the rain, the blows and bruises, or the fear of the thing that was happening to him.

But he could not stop to rest or find shelter even when he felt so tired from running that he thought he could not move another step. For everyone and everything in the city seemed to be against him.

Once he paused to catch his breath beneath a kind of chute leading from a wagon and which served to keep the rain off him somewhat, when with a sudden terrible rushing roar like a landslide of stones and boulders rolling down a mountainside, coal began to pour down the chute from the tail-gate in the wagon, and in an instant Peter was choking and covered with black coal dust.

It worked itself into his soaked fur, streaking it with black, and got into his eyes and nose and mouth and lungs. And besides, the awful noise started his heart to beating in panic again. He had never been afraid of noises before, not even the big ones like bombs and cannon fire when he had been a little boy in the blitz.

He had not yet had time to be aware that sound had quite a different meaning to him now. When noises were too loud it was like being beaten about the head and he could now hear dozens of new ones he had never heard before. The effect of a really thunderous one was to make him forget everything and rush off in a blind panic to get away from it so that they would not hurt his ears and head any more.

And so he darted away again to stop for a moment under a brightly lighted canopy where at least he was out of the dreadful rain. But even this respite did not last long, for a girl’s voice from high above him complained:

“Oh! That filthy beast! He’s rubbed up against me, and look what he’s done to my new dress!”

It was true. Peter had accidentally come too close to her, and now there was a streak of wet coal grime at the bottom of her party gown. Again the hoarse cries of “Shoo! Scat! Get out! Pack off! Go ’way!” were raised against him, and once more the angry feet came charging at him, this time joined by several umbrella handles that came down from above and sought to strike him.

To escape them, shivering and shaking, his heart beating wildly from fright and weariness, Peter ran under an automobile standing at the kerb where they could not reach him.

It was to be only a temporary sanctuary from rain and pursuit, and an unhappy one at that, as the water was now pouring through the gutters in torrents. For the next moment from directly over Peter’s head, there sounded the most appalling and ear-splitting series of explosions mingled with a grinding and clashing of metals as well as a shattering wail of the horn. Hot oil and petrol dripped down on Peter, who was nearly numb with terror from the shock of the noise. Summoning strength from he knew not where, he darted off again, and just in time, as the car started to move. He seemed to have struck a kind of second wind of panic strength, for he ran and ran and ran, bearing towards the darker and more twisted streets where there was less wheeled traffic to menace him and less likely to be humans abroad to abuse him.

And thus he passed on into the poorer section where the streets were dirtier and horrible smells arose from the gutters to poison his nostrils and make him feel sick, mingled with the odour of coffee and tea and spices that came from the closed-up shops. And nowhere was there any shelter, or friendly human voice, or hand stretched forth to help him.

Hunger was now added to the torments that beset him, hunger and the knowledge that he was fast approaching the end of his strength. But rather than stop running and face new dangers, Peter was determined to keep on until he dropped. Then he would lie there until he died.

He ran. He stopped. He started again. He faltered and kept on. He thought his eyes would burst from his head, and his chest was burning from his effort to draw breath. But ever when he came to pause, something happened to drive him on – a door banging, a shout, a sign waving in the wind, some new noise assaulting his sensitive ears, dark threatening shapes of buildings, a policeman glistening in his tall helmet and rain cape, hideous bursts of music from wireless sets in upper-storey windows, a cabbage flung at him that went bounding along the pavement like a head without a body, drunken feet staggering out of a pub door, a bottle thrown that crashed into a hundred pieces on the pavement close to him and showered him with glass.

He kept on as best he could, but running only weakly now as exhaustion crept up on him.

But the neighbourhood had changed again, the little shops and the lighted upstairs windows were gone, and Peter now entered a forbidding area of huge black sprawling buildings, of blank walls and deserted streets, of barred doors and iron gates, and long, wet, slippery steel rails he knew were railway tracks.

The yellow street lamps shone wetly on the towering sides of the warehouses and behind them the docks and the sides of great ships in the Pool, for it was to this section of London down by the Thames that Peter’s wild flight had taken him.

And there, just as he felt that he could not run or stagger another step, Peter came upon a building in which the street light showed the door standing slightly ajar. And the next moment he had slipped inside.

It was a huge warehouse piled high with sacks of grain, which gave forth a warm, comfortable, sweetish smell. There was straw on the floor and the sacks were firm and dry.

Using his sharp, curved claws to help him, Peter pulled himself up on to a layer of sacks. The rough jute felt good against his soaked fur and skin. With another sack against his back, it was almost warm. His limbs trembling with weariness, he stretched out and closed his eyes.

At that moment a voice close to him said: “Trespassing, eh? All right, my lad. Outside. Come on. Quick! Out you go!”

It was not a human voice, yet Peter understood him perfectly. He opened his eyes. Although there was no illumination in the warehouse, he found he could see clearly by the light of the street lamp outside.

The speaker was a big yellow tomcat with a long, lean, stringy body, a large head as square as a tiger’s, and an ugly, heavy scar running straight across his nose.

Peter said: “Please, I can’t. Mayn’t I stay here a little while? I’m so tired—”

The cat looked at him out of hard yellow eyes and growled, “You heard me, chum. I don’t like your looks. Pack off!”

“But I’m not hurting anything,” Peter protested. “All I want to do is rest a little and get dry. Honestly, I won’t touch a thing—”

“You won’t touch a thing,” mocked the yellow cat. “That’s rich. I’ll wager you won’t. I work here, son. We don’t allow strangers about these premises. Now get out before I knock you out.”

“I won’t,” said Peter, his stubborn streak suddenly showing itself.

“Oh, you won’t, won’t you?” said the yellow tom softly, and gave a low growl. Then, before Peter’s eyes, he began to swell as though somebody were pumping him up with a bicycle pump. Larger and larger he grew, all lumpy, crooked and out of plumb.

Peter continued to protest: “I won’t go. There’s plenty of room in here, and besides—” but that was as far as he got, for with a scream of rage the yellow cat launched his attack.

His first lightning buffet to Peter’s head knocked him off the pile of sacks on to the ground, his second sent him rolling over and over. Peter had never dreamed that anything or anyone his size could hit so hard. His head was reeling from the two blows, and he was sick and dizzy. The floor seemed to be spinning around him; he tried to stand up, but his legs gave way and he fell over on his side, and at that moment the yellow tom, teeth bared, hurled himself upon him.

What saved Peter was that he was so limp from the first punishment he had taken that he gave with the force of the attack, so that the big bully rolled with him towards the door. Nevertheless he felt teeth sink into his ear and the needle-sharp claws rip furrows in his side. Kick, kick, kick, one-two-three, and it was like thirty knife thrusts tearing his skin. More blows rained upon his bruised skull. Over and over they rolled, until suddenly they were out of the door and in the street.

Half blinded by the blood that had run into his eyes, Peter felt rather than saw the yellow cat stalk back to the warehouse door, but he heard his hard, mocking voice saying: “And don’t come back. Because the next time you do, I’ll surely kill you.”

The water running in the gutter helped to revive him a little, but only for a moment. He knew that he was bleeding from many wounds; he could hardly see out of his eyes, there was a rip in his ear, and he felt as though every bone in his body was broken. He dragged himself on a hundred yards or so. There was a hoarding advertising Bovril a little further down the street, and he tried to reach it to crawl behind it, but his strength and his senses failed him before he got there. He fell over on his side by a pillar box, with the rain pouring down in torrents and bounding up from the pavement in glistening drops. And there Peter lay quite still.

CHAPTER THREE (#ulink_2f1eea00-89d7-5907-953f-1a1c875c5262)

The Emperor’s Bed (#ulink_2f1eea00-89d7-5907-953f-1a1c875c5262)

WHEN PETER OPENED his eyes again, it was daylight and he knew that he was not dead. He was also aware of something strange, namely that he was no longer in the same place where he had fallen the night before shortly before he had lost his senses.

He remembered that there had been a hoarding with a poster, a pillar box, and a long, low wall, and now there were none of these to be seen. Instead, he found himself lying on a soft mattress on an enormous bed that had a red silk cover over it and a huge canopy at one end with folds of yellow silk coming down from a sort of oval with the single letter ‘N’ on it, written in a manner and with a kind of a crown over it that Peter found vaguely familiar.

But now he was only concerned with the wonderful comfort of the great bed, the fact that he was warm and dry, even though he ached from head to foot, and wondering how he had got to where he was.

For now that his eyes were fully opened, he noticed that he was in a dark, high-ceilinged chamber into which only a little light filtered from a small grimy window at the top with one pane out – it was really more a bin than a chamber, because it had no door and it was filled with furniture of every description, most of it covered with dust sheets, and piled to the ceilings, though in some cases the covers had slipped down and you could see the gilt and the brocade coverings of chairs and sofas. There were a lot of cobwebs and spider webs about, and it smelled musty and dusty.

All the horrors of the night before came back to Peter, the pursuit, the noises, the hounding, and the fright, the terrible mauling he had suffered at the hands of the yellow tomcat and, above all, his plight. Turned into a cat in some mysterious manner and thrown out into the street by Nanny by mistake – how was she to know that he was really Peter? – he might never again see his mother and father, his home, and Scotch Nanny from Glasgow who, except for hating cats, was a dear Nanny and good to him within the limits of a grown-up. And yet the wonderful feel of the bed and the soft silk under him was such that he could not resist a stretch, even though it hurt him dreadfully, and as he did so, to his surprise a small motor seemed to come alive in his throat and began to throb.

From somewhere behind him a soft voice said, “Ah well, that’s better. I’m glad you’re alive. I wasn’t sure at all. But I say, you are a mess!”

Startled, for the memory of his encounter with the yellow cat was still fresh, Peter rolled over and beheld the speaker squatted down comfortably beside him, her legs tucked under her, tail nicely wrapped around. She was a thin tabby with a part-white face and throat that gave her a most sweet and gentle aspect heightened by the lively and kind expression in her luminous eyes that were grey-green, flecked with gold.

She was so thin, Peter noticed, that she was really nothing but skin and bones, and yet there was a kind of tender and rakish gallantry in her very boniness that was not unbecoming to her. For the rest, she was spotlessly clean, particularly the white patch at her breast, which gleamed like ermine and (along with her remark) made Peter acutely conscious for the first time of his own condition. She was quite right. He was a mess.

His fur was dirty, matted with blood and streaked with mud and coal dust. To look at him, no one would ever have known he had once been a snow-white cat, much less a small boy.

He said to the tabby, “I’m sorry. I’ll go away as soon as I am able. I don’t know how I got here. I thought I was going to die in the street.”

“You might have,” she said. “I found you and brought you here. I don’t think you’re very well. Hold still, and I’ll wash you a bit. Maybe that will make you feel a little better.”

Although Peter had acquired the body and the appearance of a white cat, he still thought and felt like a boy, and the prospect of being washed at that moment did not at all appeal to him, and particularly not at the hands, or rather tongue, of a bone-thin, scrawny tabby cat even if she had a sweet white face and a kind and gentle expression. What he really wanted was to stretch out on the heavy silk of the covers on the comfortable bed and just stay there and sleep and sleep.

But he remembered his manners and said, “No, thank you. I don’t want to trouble you. I don’t really think I would care—”

But the tabby cat interrupted him with a gentle “Hush! Of course you would. And I do it very well too.”

She reached out a scrawny part-white paw and laid it across his body, kindly but firmly, so that he was held down. And then with a long, stroking motion of her head and pink tongue she began to wash him, beginning at his nose, travelling up between the ears and down the back of his neck and the sides of his face.

And thereafter something strange happened to Peter, at least inside him. It was only a poor, thin, stray alley cat washing him, her rough tongue rasping against his fur and skin, but what it made him feel like was remembering when he had been very small and his mother had held him in her arms close to her. It was almost the very first thing he could remember.

He had been taking some of his early running-walking steps and had fallen and hurt himself. She had picked him up and held him tightly to her and he had cuddled his head into the warm place at her neck just beneath the chin. With her soft hands she had stroked the place where it hurt, and said, “There, Mother’ll make it all better. Now – it doesn’t hurt any more!” And it hadn’t. All the pain had gone, and he remembered only feeling safe and comfortable and contented.

That same warm, secure feeling was coming over him now as the little rough tongue rasped over his injured ear and down the long deep claw furrows torn into the skin of his shoulder and his side, and with each rasp, as her tongue passed over it, it seemed as though the pain that was there was erased as if by magic.

All the ache went out of his sore muscles too, as her busy tongue got around and behind and underneath, refreshing and relaxing them, and a most delicious kind of sleepiness began to steal over him. After all the dreadful things that had happened to him, it was so good to be cared for. He half expected to hear her say, “See, Mother’s making it all better! There! Now it doesn’t hurt any more …”

But she didn’t. She only kept on washing in a wonderful and soothing rhythm, and shortly Peter felt his own head moving in a kind of drowsy way in time with hers; the little motor of contentment was throbbing in his throat. Soon he nodded and went fast asleep.

When he awoke it was much later, because the light coming in through the grimy bit of window was quite different; the sun must have been well up in the sky, for a beam of it came in through a clear spot in the pane and made a little pool of brightness on the red silk cover of the enormous bed.

Peter rolled over into the middle of it and saw that he looked almost respectable again. Most of the coal grime and mud was off him, his white fur was dry and fluffed and now served again to hide and keep the air away from the ugly scars and scratches on his body. He felt that his torn ear had a droop to it, but it no longer hurt him and was quite dry and clean.

There was no sign of the tabby cat. Peter tried to stand up and stretch, but found that his legs were queerly wobbly and that he could not quite make it. And then he realised that he was weak with hunger as well as loss of blood, and that if he did not get something to eat soon he must surely perish. When was it he had last eaten? Why, ages ago, yesterday or the day before, Nanny had give him an egg and some greens, a little fruit jelly, and a glass of milk for lunch. It made him quite dizzy to think of it. When would he ever eat again?

Just then he heard a little soft, singing sound, a kind of musical call – “Errrp, purrrrrrow, urrrrrrp!” – that he found somehow extraordinarily sweet and thrilling. He turned to the direction from which it was coming and was just in time to see the tabby cat leap in through the space between the slats at the end of the bin. She was carrying something in her mouth.

In an instant she had jumped up on to the bed alongside him and laid it down.

“Ah,” she said, “that’s better. Feeling a little more fit after your sleep. Care to have a bit of mouse? I just caught it down the aisle near the lift. It’s really quite fresh. I wouldn’t mind sharing it with you. I could stand a snack myself. There you are. You have a go at it first.”

“Oh, n-no … No-no, thank you,” said Peter in horror. “N-not mouse. I couldn’t—”

“Why,” asked the tabby cat in great surprise, and with just a touch of indignation added, “What’s the matter with mouse?”

She had been so kind and he was so glad to see her again that Peter was most anxious not to hurt her feelings.

“Why, n-nothing, I’m sure. It’s … well, it’s just that I’ve never eaten one.”

“Never eaten one?” The tabby’s green eyes opened so wide that the flecks of gold therein almost dazzled Peter. “Well, I never! Not eaten one! You pampered, indoor, lap and parlour cats! I suppose it’s been fresh chopped liver and cat food out of a tin. You needn’t tell me. I’ve had plenty of it in my day. Well, when you’re off on your own and on the town with nobody giving you charity saucers of cream or left-over titbits, you soon learn to alter your tastes. And there’s no time like the present to begin. So hop to it, my lad, and get acquainted with mouse. You need a little something to set you up again.”

And with this she pushed the mouse over to him with her paw and then stood over Peter, eyeing him. There was a quiet forcefulness and gentle determination in her demeanour that made Peter a little afraid for a moment that if he didn’t do as she said, she might become angry. And besides, he had been taught that when people offered to share something with you at a sacrifice to themselves, it was not considered kind or polite to refuse.

“You begin at the head,” the tabby cat declared firmly.

Peter closed his eyes and took a small and tentative nibble.

To his intense surprise, it was simply delicious.

It was so good that before he realised it, Peter had eaten it up from the beginning of its nose to the very end of its tail. And only then did he experience a sudden pang of remorse at what he had done in his moment of greediness. He had very likely eaten his benefactress’s ration for the week. And by the look of her thin body and the ribs sticking through her fur, it had been longer than that since she had had a solid meal herself.

But she did not seem to mind in the least. On the contrary, she appeared to be pleased with him as she beamed down at him and said, “There, that wasn’t so bad, was it? My tail, but you were hungry!”

Peter said, “I’m sorry. I’m afraid I’ve eaten your dinner.”

The tabby smiled cheerfully. “Don’t give it another thought, laddie! Plenty more where that one came from.” But even though the smile and the voice were cheerful, yet Peter detected a certain wan quality about it that told him that this was not so, and that she had indeed made a great sacrifice for him, generously and with sweet grace.

She was eyeing him curiously now, it seemed to Peter almost as though she was expecting something of him, but he did not know what it was and so just lay quietly enjoying the feeling of being fed once again. The tabby opened her mouth as though she were going to say something, but then apparently thought better of it, turned, and gave her back a couple of quick licks.

Peter felt as if something he did not quite understand had sprung up to come between them, something awkward. To cover his own embarrassment about it, he asked: “Where am I – I mean, where are we?”

“Oh,” said the tabby, “this is where I live. Temporarily, of course. You know how it is with us, and if you don’t, you’ll soon find out. Though I must say it’s months since I’ve been disturbed here. I know a secret way in. It’s a warehouse where they store furniture for people. I picked this room because I liked the bed. There are lots of others.”

Now Peter remembered having learned in school what the crown and the ‘N’ stood for, and couldn’t resist showing off. He said, “The bed must have belonged to Napoleon, once. That’s his initial up there, and the crown. He was a great emperor.”

The tabby did not appear to be at all impressed. She merely remarked, “Was he, now? He must have been enormously large to want a bed this size. Still – I must say it is comfortable, and I don’t suppose he has any further use for it, for he hasn’t been here to fetch it in the last three months and neither has anybody else. You’re quite welcome to stay here as long as you like. I gather you’ve been turned out. Who was it mauled you? You were more than half dead when I found you last night lying in the street and dragged you in here.”

Peter told the tabby of his encounter with the yellow tomcat in the grain warehouse down by the docks. She listened to his tale with alert and evident sympathy, and when he had finished, nodded and said:

“Oh dear! Yes, that would be Dempsey. He’s the best fighter on the docks from Wapping all the way down to Limehouse Reach. Everybody steers clear of Dempsey. I say, you did have a nerve, telling him off! I admire you for that even if it was foolhardy. No house pets are much good at rough-and-tumble, and particularly against a champion like Dempsey.”

Peter liked the tabby’s admiration, he found, and swelled a little with it. He wished that he had managed to give Dempsey just one stiff blow to remember him by, and thought that perhaps some time he would. But then he recalled the big tom’s last words: “And don’t come back. Because next time you do, I’ll surely kill you,”and felt a little sick, particularly when he thought of the powerful and lightning-like buffets of those terrible paws that had so quickly robbed him of his senses and laid him open for the final attack which but for a bit of luck might have finished him. Assuredly he too would steer clear of Dempsey, but to the tabby he said:

“Oh, he wasn’t so much. If I hadn’t been so tired from running—”

The tabby smiled enigmatically. “Running from what, laddie?”

But before Peter could reply, she said: “Never mind, I know how it is. When you first find yourself on your own, everything frightens you. And don’t think that everybody doesn’t run. It’s nothing to be ashamed of. By the way, what is your name?”

Peter told her. She said, “Hm … Mine’s Jennie. I’d like to hear your story. Care to tell it?”

Peter very much wanted to do so. But he found suddenly that he was a little timid because he was not at all sure how it would sound, and, even more important, whether the tabby would believe him and how she would take it. For it was certainly going to be a most odd tale.

CHAPTER FOUR (#ulink_9bbc3b0b-95b6-5930-8229-4fc6204724b2)

A Story is Told (#ulink_9bbc3b0b-95b6-5930-8229-4fc6204724b2)

BY AND LARGE, Peter made about as bad a beginning as could be when he said:

“I’m not really a cat, I’m a little boy. I mean actually, not so little. I’m eight.”

“You’re what?” Jennie gave a long, low growl, and her tail fluffed up to twice its size.

Peter could not imagine what he had said to make her angry, and he repeated hesitantly, “A boy—”

The tabby’s tail swelled another size larger and twitched nervously. Her eyes seemed to shoot sparks as she hissed: “I hate people!”

“Oh!” said Peter, for he was suddenly full of sympathy and understanding for the poor thin little tabby who had been so kind to him. “Somebody must have been horrible to you. But I love cats!”

Jennie looked mollified, and her tail began to subside. “Of course,” she said, “it’s just your imagination. I should have known. We’re always imagining things, like a leaf blowing in the wind being a mouse, or if there’s no leaf there at all, then we can imagine one, and when we’ve imagined it, go right on from there and imagine it isn’t a leaf at all but a mouse, or if we like, a whole lot of mice, and then we start pouncing on them. You just like to imagine that you’re a little boy, though what kind of a game you can make out of that I can’t see. Still—”

“Oh, please,” said Peter, interrupting. He could feel somehow that the tabby very much didn’t want him to be a boy, and yet, even at the risk of offending her, he knew that he must tell her the truth. “Please, I’m so sorry, but it is so. You must believe me. My name is Peter Brown, and I live in a flat with my mother and father and Nanny, in a house at Number 1A, Cavendish Mews. Or at least I did live there before—”

“Oh, come now,” protested Jennie, “don’t be silly. Anybody can see that you look like a cat, you feel like a cat, you smell like a cat, you purr like a cat, and you—” But here her voice trailed off into silence for a moment and her eyes grew wide again. “Oh dear,” she said then. “But there is something the matter. I’ve felt it all along. You don’t act like a cat—”

“Of course not,” Peter said, relieved that he might be believed at last.

But the tabby, her eyes growing wider and wider, wasn’t listening. She was going back over her acquaintance with Peter and enumerating the odd things that had happened since she had found him exhausted, wounded and half dead in the alley and had dragged him to her home, for what reason she did not know.

“You told off Dempsey, and right on his own premises, where he works. No sensible cat would have done that, no matter how brave. And besides, it’s against the rules.” She almost seemed to be ticking items off the end of her claws, though of course she wasn’t. “And then you didn’t want to eat mouse when you were literally starving – said you’d never had one, and then you ate it all up at one gobble, with never a thought that I might be hungry too. Not that I minded, but a real cat would never have done that. Oh, and then, of course – that’s what I was trying to remember! You ate mouse right on the silk counterpane where you’ve been sleeping, and you didn’t wash after you’d finished …”

Peter said, “Why should I? We always wash before eating. At least, Nanny always sends me into the bathroom and makes me clean my hands and face before sitting down to table.”

“Well, cats don’t!”declared Jennie decisively, “and it seems to me much the more sensible way. It’s after you’ve eaten you find yourself all greasy and sticky, with milk on your whiskers and gravy all over your fur if you’ve been in too much of a hurry. Oh dear!” she ended up. “That almost proves it. But I must say I’ve never heard of such a thing in all my life!”

Peter thought to himself, “She is good, and she has been kind to me, but she does love to chatter.” Aloud, he said, “If you would like me to tell you how it all happened, perhaps—”

“Yes, do, please,” said the tabby cat and settled herself more comfortably on the bed with her front paws tucked under her, “I should love to hear it.”

And so Peter began from the beginning and told her the whole story of what had happened to him.

Or rather he began away back before it began, really, and told her about his home in the Mews near the square and the little garden there inside the iron railings where Nanny took him to play every day after school when the weather was fine, and about his father who was a Colonel in the Guards and was away from home most of the time, first during the war when he was in Egypt and Italy, and then in France and Germany, and he hardly saw him at all, and then later in peacetime when he would come home now and then wearing a most beautiful uniform with blue trousers that had a red stripe down the side, except that as soon as he got into the house he went right into his room and changed it for an old brown tweed suit which wasn’t nearly as interesting or exciting.

Sometimes he stayed a little while for a chat or a romp with Peter, but usually he went off with Peter’s mother with golf clubs or fishing tackle in the car and they would stay away for days at a time. He would be left with only Cook and Nanny in the flat and it wasn’t much fun being alone, for even when he was with friends in the daytime, playing or visiting, it got very lonely at night without his father and mother. When they weren’t away on a trip together, they would dress up every evening and go out. And that was when he wished most that he had a cat of his own that would curl up at the foot of his bed, or cuddle, or play games just with him.

And he told the tabby all about his mother, how young and beautiful she was, so tall and slender, with light-coloured hair as soft as silk, that was the colour of the sunshine when it came in slantwise through the nursery window in the late afternoon, and how blue were her eyes and dark her lashes.

But particularly he remembered and told Jennie how good she smelled when she came in to say goodnight to him before going out for the evening, for when Peter’s father was away she was unhappy and bored and went off with friends a great deal seeking amusement.

It was always when he loved her most, Peter explained, when she came in looking and smelling like an angel, with clouds of beautiful materials around her, and her hair so soft and fragrant, when he so much wanted to be held to her, that she left him and went away.

Jennie nodded. “Mmmmm. I know. Perfume. I love things that smell good.”

She was indignant when Peter came to the part about not being allowed to have a cat because of the mess it might make around a small flat, and said, “Mess, indeed! We never make messes, unless we’re provoked, and then we do it on purpose. And can’t we just—!” But strangely enough she took Nanny’s part when Peter reached the point in his story about Nanny being afraid of cats and not liking them.

“There are people who don’t, you know,” she explained, when Peter expressed surprise, “and we can understand and respect them for it. Sometimes we like to tease them a little by rubbing up against them, or getting into their laps just to see them jump. They can’t help it any more than we can help not liking certain kinds of people and not wanting to have anything to do with them. But at least we know where we stand when we come across someone like your Nanny. It’s the people who love us, or say they love us and then hurt us, who …”

She did not finish the sentence, but turned away quickly, sat up, and began to wash violently down her back. But before she did, Peter thought that he had noticed the shine of tears in her eyes, though of course it couldn’t be so, since he had never heard of cats shedding tears. It was only later he was to learn that they could both laugh and cry.

Nevertheless, he felt that the tabby must be nursing some secret hurt, perhaps like his own, and in the hopes of taking her mind away from something sad, he launched into a description of the events leading up to his strange and mysterious transformation.

He began by telling about the tiger-striped kitten sunning and washing herself by the little garden in the centre of the square, and how he had wanted to catch her and hold her. Jennie showed immediate interest. She stopped washing and enquired: “How old was she? Was she pretty?”

“Oh yes,” said Peter, “very pretty, and full of fun …”

“Prettier than I?” Jennie enquired, with seeming nonchalance.

Peter had thought she had been, for she was like a round ball of fluff as he remembered, with most proud whiskers and two white and two brown feet. But he wouldn’t for anything have offended the tabby by telling her so. The truth was that for all her gentle ways and the kindly expression of her white face, Jennie was quite plain, with her small head, longish ears and slanted, half-Oriental eyes, and what with being so dreadfully thin making her bones stick out, Peter felt she was really nothing much to look at as cats went. But he was already old enough to know that one sometimes told small white lies to make people happy, and so he replied: “Oh, no! I think you’re beautiful!” After all, he had eaten her mouse.

“Do you really?” said Jennie, and for the first time since they had met, Peter heard a small purr coming from her. To cover her confusion she gave one of her paws a few tentative licks and then with a pleased smile on her thin face, enquired: “Well, and what happened then?”

And Peter thereupon told her all the rest of the story right to the end.

When he had finished with “… and then the next thing I knew, I opened my eyes and here I am”, there was a long silence. Peter felt tired from the effort of telling the story and reliving all the dreadful moments through which he had come, for he was yet far from having regained his full strength, even with rest and a meal.

Jennie, undeniably taken aback by the tale she had heard, appeared to be thinking hard, her eyes unblinking, and a faraway look in them, which, however, was not disbelief. It was clear from her demeanour that she apparently accepted Peter’s word that he was not a cat really, but a little boy, and the queer circumstances that had brought this about, and that it was something else that was occupying her mind.

Finally she turned her too-small, slender head towards Peter and said: “Well, what’s to be done?”

Peter said, “I don’t know, I’m sure. I suppose if I am a cat, I will just have to be one—”

The tabby put her gentle paw on his and said softly, “But, Peter, don’t you see, that’s just it! You said yourself that you didn’t feel as though you were a cat at all. If you’re going to be one, you must first learn how.”

“Oh dear,” said Peter, who never did much enjoy having to learn things, “is there more to being a cat than just liking to eat mice and purring?”

The little puss was genuinely shocked. “Is there more?” she repeated. “You couldn’t begin to imagine all the things there are! There must be hundreds. Why, if you left here right now and went out looking like a white cat, but feeling inside and thinking like a boy, I shouldn’t be inclined to give you more than ten minutes before you’d be in some terrible trouble again – like last night. It isn’t easy to be on your own, even if you have learned to know everything or nearly everything that a cat ought to know.”

Peter hadn’t thought about it that way, but there was no doubt she was right. If he had been himself in shape and form and had been locked out of the house, or had got lost from Nanny at the fun-fair, or in the park, he would have known enough to go straight up to a policeman and tell him his name and address and ask to be taken home. But he couldn’t very well do this in his present condition as a white cat with a slightly droopy left ear where it had been ripped by a yellow tom named Dempsey. And what was worse, now that the tabby had called it to his attention, he was a cat and didn’t know the first thing about how to behave as one. He began to feel frightened again, but different from the panic of the night before – it was a new kind of shakiness as though the bed and the ground and everything beneath his four paws was no longer very steady. He said somewhat piteously to the tabby: “Oh, Jennie – now I’m really frightened! What shall I do?”

She thought for a moment longer and then said, “I know! I’ll teach you.”

Peter felt such relief he could have cried. “Jennie dear! Would you? Could you?”

The expression on the face of the cat was positively angelic, or so Peter thought, and now she actually almost did look beautiful to him as she said: “But of course. After all, you’re my responsibility. I found you and brought you here. But one thing you must promise me if I try …”

Peter said, “Oh yes, I’ll promise anything—”

“First of all, do as I tell you until you can begin to look after yourself a little, but most important, never tell another soul your secret. I’ll know, but nobody else needs to, because they just wouldn’t understand. If we get into any kind of trouble, just let me do the talking. Never so much as hint or let on in any way to any other cat what you really are. Promise?”

Peter promised, and Jennie gave him a comradely little tap on the side of his head with her paw. Just the touch of her velvet pad and the simplicity of the caress made Peter feel happier already.

He said, “Won’t you tell me your story now, and who you are? I know nothing about you, and you’ve been so good to me …”

Jennie withdrew her paw, and a look of sadness came over her gentle face as she turned away for a moment. She said, “Later, perhaps, Peter. It is hard for me to speak about it now. And besides, you might not like it at all. Since you say you are a human and really not a cat at all, you would not be able to understand the way I feel and why I will never again live with people.”

“Please do tell me,” Peter pleaded. “And I will like it, I’m sure, because I like you.”

Jennie could not resist a small purr at Peter’s sincerity. She said, “You are a dear—” and then fell into reflective silence for a moment. Finally she seemed to make up her mind and said:

“See here, what is really important at the moment is for you to begin to learn something about being a cat, and the sooner we begin, the better. I shudder to think what might happen to you if you were alone again. How would it be if we had a lesson first? And of course nothing is more pressing than for you to learn how to wash. Afterwards, perhaps, I will be able to tell you my story.”

Peter hid his disappointment because she had been so kind to him and he did not wish to upset her. He merely said, “I’ll try, though I’m not very good at lessons.”

“I’ll help you, Peter,” Jennie reassured him, “and you’ll be surprised how much better you will feel when you know how. Because a cat must not only know how to wash, but WHEN to wash. You see, it’s something like this …”

CHAPTER FIVE (#ulink_b1a920da-b5da-51b8-bd07-be54d48fca98)

When in Doubt – Wash (#ulink_b1a920da-b5da-51b8-bd07-be54d48fca98)

“‘WHEN IN DOUBT – any kind of doubt – Wash!’ That is Rule Number 1,” said Jennie. She now sat primly and a little stiffly, with her tail wrapped around her feet, near the head of the big bed beneath the Napoleon Initial and Crown, rather like a schoolmistress. But it was obvious that the role of teacher and the respectful attention Peter bestowed upon her were not unendurable, because she had a pleased expression and her eyes were again gleaming brightly.

The sun had reached its noon zenith in the sky in the world that lay outside the dark and grimy warehouse, and coming in slantwise through the small window sent a dusty shaft that fell like a theatrical spotlight about Jennie’s head and shoulders as she lectured.

“If you have committed any kind of an error and anyone scolds you – wash,” she was saying. “If you slip and fall off something and somebody laughs at you – wash. If you are getting the worst of an argument and want to break off hostilities until you have composed yourself, start washing. Remember, every cat respects another cat at her toilet. That’s our first rule of social deportment, and you must also observe it.

“Whatever the situation, whatever difficulty you may be in you can’t go wrong if you wash. If you come into a room full of people you do not know, and who are confusing to you, sit right down in the midst of them and start washing. They’ll end up by quieting down and watching you. Some noise frightens you into a jump, and somebody you know saw you were frightened – begin washing immediately.

“If somebody calls you and you don’t care to come and still you don’t wish to make it a direct insult – wash. If you’ve started off to go somewhere and suddenly can’t remember where it was you wanted to go, sit right down and begin brushing up a little. It will come back to you. Something hurt you? Wash it. Tired of playing with someone who has been kind enough to take time and trouble and you want to break off without hurting his or her feelings? Start washing.

“Oh, there are dozens of things! Door closed and you’re burning up because no one will open it for you – have yourself a little wash and forget it. Somebody petting another cat or dog in the same room, and you are annoyed over that – be nonchalant; wash. Feel sad – wash away your blues. Been picked up by somebody you don’t particularly fancy and who didn’t smell good – wash him off immediately and pointedly where he can see you do it. Overcome by emotion – a wash will help you to get a grip on yourself again. Any time, anyhow, in any manner, for whatever purpose, wherever you are, whenever and why ever that you want to clear the air, or get a moment’s respite or think things over – WASH!

“And,” concluded Jennie, drawing a long breath, “of course you also wash to get clean and to keep clean.”

“Goodness!” said Peter, quite worried, “I don’t see how I could possibly remember them all.”

“You don’t have to remember any of it, actually,” Jennie explained. “All that you have to remember is Rule 1:‘When in doubt – WASH!’”

Peter, who like all boys had no objection to being reasonably clean, but not too clean, saw the problem of washing looming up large and threatening to occupy all of his time. “It’s true, I remember, you always do seem to be washing,” he protested to Jennie, “I mean all cats I’ve seen, but I don’t see why. Why do cats spend so much of their time at it?”

Jennie considered this question for a moment, and then replied, “Because it feels so good to be clean.”

“Well, at any rate I shall never be capable of doing it,” Peter remarked, “because I won’t be able to reach places now that I am a cat and cannot use my hands. And even when I was a boy, Nanny used to have to wash my back for me …”

“Nothing of the kind,” said Jennie. “The first thing you will learn is that there isn’t an inch of herself of himself that a cat cannot reach to wash. If you had ever owned one of us, you would know. Now watch me. We’ll begin with the back. I’ll do it first, and then you come over here alongside of me and do as I do.”

And with that, sitting upright, she turned her head around over her shoulder with a wonderful ease and grace, and with little short strokes of her tongue and keeping her chin down close to her body, she began to wash over and around her left shoulder blade, gradually increasing the amount of turn and the length of the stroking movement of her head until her rough, pink tongue was travelling smoothly and firmly along the region of her upper spine.

“Oh, I never could!” cried Peter, “because I cannot twist my head around as far as you can. I never know what is going on behind me unless I turn right around.”

“Try,” was all Jennie replied.

Peter did, and to his astonishment found that whereas when he had been a boy he had been unable to turn his head more left and right than barely to be able to look over his shoulders, now he could swivel it quite around on his neck so that he was actually gazing out behind him. And when he stuck out his tongue and moved his head in small circles as he had seen Jennie do, there he was washing around his left shoulder.

“Oh, bravo! Splendid!” applauded Jennie. “There, you see! Well done, Peter. Now turn a little more – you’re bound to be a bit stiff at first – and down the spine you go!”

And indeed, down the spine, about halfway from below his neck to the middle of his back, Peter went. He was so delighted that he tried to purr and wash at the same time, and actually achieved it.

“Now,” Jennie coached, “for the rest of the way down, you can help yourself and make it easier – like this. Curve your body around and go a little lower so that you are half sitting, half lying. That’s it! Brace yourself against your right paw and pull your left paw in a little closer to you so that it is out of the way. There … Now, you see, that brings the rest of you nicely around in a curve where you can get at it. Finish off the left side of your back and hindquarters and then shift around and do the other side.”

Peter did so, and was amazed to find with what little effort the whole of his spine and hindquarters was brought within ample reach of his busy tongue. He even essayed to have a go at his tail from this position, but found this a more elusive customer. It would keep squirming away.

Jennie smiled. “Try putting a paw on it to hold it down. The right one. You can still brace yourself with it. That’s it. We’ll get at the underside of it later on.”

Peter was so enchanted with what he had learned that he would have gone on washing and washing the two sides of his back and flanks and quarters if Jennie hadn’t said, “There, that’s enough of that. There’s still plenty of you left, you know. Now you must do your front and the stomach and the inside of your paws and quarters.”

The front limbs and paws of course proved easy for Peter, for they were within ample reach, but when he attempted to tackle his chest, it was something else.

“Try lying down first,” Jennie suggested. “After a while you’ll get so supple you will be able to wash your chest sitting up just by sticking your tongue out a little more and bobbing your head. But it’s easier lying down on your side. Here, like this,” and she suited the action to the word and soon Peter found that he actually was succeeding in washing his chest fur just beneath his chin.

“But I can’t get at my middle,” he complained, for indeed the underside of his belly defied his clumsy efforts to reach it, bend and twist as he would.

Jennie smiled. “‘Can’t’ catches no mice,” she quoted. “That is more difficult. Watch me now. You won’t do it lying on your side. Sit up a bit and rock on your tail. That’s it, get your tail right under you. You can brace with either of your forepaws, or both. Now, you see, that bends you right around again and brings your stomach within reach. You’ll get it with practice. It’s all curves. That’s why we were made that way.”

Peter found it more awkward to balance than in the other position and fell over several times, but soon found that he was getting better at it and that each portion of his person that was thus made accessible to him through Jennie’s knowledge, experience and teaching brought him a new enjoyment and pleasure of accomplishment. And of course Jennie’s approval made him very proud.

He was forging ahead so rapidly with his lesson that she decided to see whether he could go and learn by himself. “Now how would you go about doing the inside of the hindquarter?” she asked.

“Oh, that’s easy,” Peter cried. But it wasn’t at all. In fact the more he tried and strained and reached and curved, the further away did his hind leg seem to go. He tried first the right and then the left, and finally got himself tangled in such a heap of legs, paws and tail that he fell right over in such a manner that Jennie had to take a few quick dabs at herself to keep from laughing.

“I can’t – I mean I don’t see how …” wailed Peter, “there isn’t any way …”

Jennie was contrite at once and hoped Peter had not seen she had been amused. “Oh, I’m sorry,” she declared. “That wasn’t fair of me. There is, but it’s most difficult, and you have to know how. It took me the longest time when my mother tried to show me. Here, does this suggest anything to you – Leg of Mutton? I’m sure you’ve seen it dozens of times,” and she assumed an odd position with her right leg sticking straight up in the air and somehow close to her head, almost like the contortionist that Peter had seen at the circus at Olympia who had twisted himself right around so that his head came down between his legs. He was sure that he could never do it.

Peter tried to imitate Jennie but only succeeded in winding himself into a worse knot. Jennie came to his rescue once more. “See here,” she said, “let’s try it by counts, one stage at a time. Once you’ve done it, you know, you’ll never forget it. Now –

“One – rock on your tail.” Peter rocked.

“Two – brace yourself with your left forepaw.” Peter braced.

“Three – half sit, and bend your back.” Peter managed that, and made himself into the letter C.

“Four – stretch out the left leg all the way. That will keep you from falling over the other side and provide a balance for the paw to push against.” This too worked out exactly as Jennie described it when Peter tried it.

“Five – swing your right leg from the hip – you’ll find it will go – with the foot pointing straight up into the air. Yes, like that, but outside, not inside the right forepaw.” It went better this time. Peter got it almost up.

“Six – NOW you’ve got it. Hold yourself steady by bracing the right front forepaw. SO!”

Peter felt like shouting with joy. For there he was, actually sitting, leg of mutton, his hindquarter shooting up right past his cheek and the whole inside of his leg exposed. He felt that he was really doubled back on himself like the contortionist, and he wished that Nanny were there so that he could show her.

By twisting and turning a little, there was no part of him underneath that he could not reach, and he washed first one side and then, without any further instruction from Jennie, managed to reverse the position and get the left leg up, which drew forth an admiring, “Oh, you are clever!” from Jennie – “it took me just ages to learn to work the left side. It all depends whether you are left-or right-pawed, but you caught on to it immediately. Now there’s only one thing more. The back of the neck, the ears and the face.”

In a rush to earn more praise Peter went nearly cross-eyed trying to get his tongue out and around to reach behind him and on top of him, and of course it wouldn’t work. He cried – “Oh dear, THAT must be the most complicated of all.”

“On the contrary,” smiled Jennie, “it’s quite the simplest. Wet the side of your front paw.” Peter did so. “Now rub it around over your ears and the back of your neck.”

Now it was Peter’s turn to laugh at himself. “How stupid I am,” he said. “That part is just the way I do it at home. Except I use a wash-rag, and Nanny stands there watching to make certain I go behind the ears.”

“Well,” said Jennie, “I’m watching you now …”