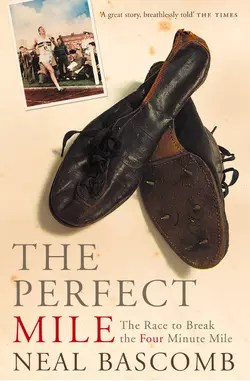

The Perfect Mile

Neal Bascomb

This edition does not include illustrations.The inspirational story of three international runners attempting to achieve what no one had managed – to break the four-minute mile barrier. It was the ultimate test of endurance, and the human drama that unfolded is told here for the first time.In sport, running the four-minute mile was the elusive Holy Grail, considered by most to be beyond the limits of human endeavour.Then in late 1952, shortly after the Helsinki Olympics, three men set out to challenge the record books: Roger Bannister, the Oxford medical student, the great British hero who epitomised the ideal of the amateur athlete; John Landy, the tireless Australian, the romantic who trained night and day in search of perfection; and the American Wes Santee, son of a Kansas ranch hand, a natural runner and the quickest of the three ('I was just born to run fast').Three men, each of contrasting character, competing thousands of miles apart, but all with the same valedictory goal. The Perfect Mile is the stirring account of their quest for sporting martyrdom, charting their journey through triumph and failure, culminating in the moment when Bannister broke the record in a monumental run at the Iffley Road cinder track in Oxford in May 1954. It was a feat that became one of the most celebrated in the history of British sport.Far from bringing an end to the rivalry, this watershed moment turned out to be merely the prelude to a final climactic battle three months later – the ultimate head-to-head between Bannister and Landy in what was dubbed ‘the mile of the century’ at the Vancouver Empire Games.Bascomb provides a fascinating account of what happened and an invaluable insight into the motivations and characters of three amazing achievers.

COPYRIGHT (#ulink_bf7f4ec2-5a5f-5534-a70c-f0e589e31116)

HarperNonFiction

A division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain in 2004.

This edition first published by HarperCollinsPublishers in 2005

Copyright © Neal Bascomb 2004

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Neal Bascomb asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007173723

Ebook Edition © MAY 2017 ISBN: 9780007382989

Version: 2017-05-11

DEDICATION (#ulink_dc6d6bc8-2395-5d04-adb8-a7b1e81e1f6d)

To Diane

AUTHOR’S NOTE (#ulink_e1da14e1-fe79-50e5-8e52-4c0870a3d54a)

When an author sets out to investigate a legend, and there are few stories as legendary in sport as the pursuit of the four-minute mile, it is initially difficult to see the heroes around whom events unfolded as true flesh-and-blood individuals. Myth tends to wrap its arms around fact, and memory finds a comfortable groove and stays the course. What makes these individuals so interesting – their doubts, vulnerabilities, and failures – is often airbrushed out, and their victories characterised as faits accomplis. But true heroes are never as unalloyed as they first appear (thank goodness). We should admire them all the more for this fact.

Getting past the panegyrics that populate this history has been the real pleasure behind my research. No doubt there have been some very fine articles written about this story, but only by interviewing the principals – Roger Bannister, John Landy, and Wes Santee – and their close friends at the time does one do justice to the depth of this story. Their generosity in this regard has been without measure. These interviews, coupled with contemporaneous newspaper and magazine articles as well as memoir accounts by several individuals involved in the events, serve as the basis of The Perfect Mile. With this material, the story almost wrote itself.

I have included collective references for those interested in knowing the sources behind particular conversations and scenes. No dialogue in this book was manufactured; it is either a direct quote from a secondary resource or from an interview. That said, half a century has passed since this story occurred. On some occasions, dialogue is represented as the best recollection of what was in all probability said. Furthermore, memory has its faults, and in those situations where interview subjects contradicted one another I almost always went with what the principal recollected. In those instances when contemporaneous sources (mainly newspaper articles) did not correspond with memory, I primarily went with the former, particularly when there were several sources indicating the same facts. Having inhabited this world for the past eighteen months, aswim in paper and interview tapes, I feel I have been a fairly accurate judge of the events as they happened. I hope that I have served the history of these heroes well.

CONTENTS

Cover (#u07f6861e-bb91-5576-81a5-3bf2f0030ca0)

Title Page (#u0381d3b4-2786-5c8a-b88f-28325bea5527)

Copyright (#ulink_5f9055c3-4e4a-54e3-b5cc-061ce512d212)

Dedication (#ulink_9ff080da-0f89-57c5-af81-f3b779a499f5)

Author’s Note (#ulink_a51a20ac-4617-597c-b723-4d0afbb136b3)

Prologue (#ulink_09806cfb-2d3f-51ad-abb5-619807002ef6)

PART I (#ulink_b29d09f4-12c7-52d6-a5a3-3e5e4bc6a1da)

A Reason to Run (#ulink_b29d09f4-12c7-52d6-a5a3-3e5e4bc6a1da)

Chapter 1 (#ulink_dfd39348-c130-5778-a80d-68be6f816957)

Chapter 2 (#ulink_e00248d1-d801-550f-90a7-b1132b7bb4eb)

Chapter 3 (#ulink_9607c189-a9bb-5e17-8c0c-a754b7f43e83)

Chapter 4 (#ulink_d1d0f072-b19a-5fb8-8f27-1fa6aa9bc029)

Chapter 5 (#ulink_7f335eaa-1dd0-5acc-8aa1-dc1c9e4a5b5d)

PART II (#litres_trial_promo)

The Barrier (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 6 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

PART III (#litres_trial_promo)

The Perfect Mile (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

References (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Other Books By (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PROLOGUE (#ulink_7d366724-b62e-58dd-8907-c9ac482d1565)

If you can force your heart and nerve and sinew

To serve your turn long after they are gone,

And so hold on when there is nothing in you

Except the Will which says to them: ‘Hold on!’

Rudyard Kipling, ‘If …’

‘How did he know he would not die?’ a Frenchman asked of the first runner to break the four-minute mile. Half a century ago the ambition to achieve that goal equalled scaling Everest or sailing alone around the world. Most people considered running four laps of the track in four minutes to be beyond the limits of human speed. It was foolhardy and possibly dangerous to attempt. Some thought that rather than a lifetime of glory, honour, and fortune, a hearse would be waiting for the first man to accomplish the feat.

The four-minute mile: this was the barrier, both physical and psychological, that begged to be broken. The number had a certain mathematical elegance. As one writer explained, the figure ‘seemed so perfectly round – four laps, four quarter miles, four-point-oh-oh minutes – that it seemed God himself had established it as man’s limit’. Under four minutes: the place had the mysterious and heroic resonance of reaching sport’s Valhalla. For decades the world’s best middle-distance runners tried and failed. They came to within a second or so, but that was as close as they were able to get. Attempt after spirited attempt proved futile. Each effort was like a stone added to a wall that looked increasingly impossible to breach.

The four-minute mile had a fascination beyond its mathematical roundness and assumed impossibility. Running the mile was an art form in itself. The distance, unlike the 100-yard sprint or marathon, required a balance of speed and stamina. The person to break that barrier would have to be fast, diligently trained, and supremely aware of his body, so that he would cross the finish line just at the point of complete exhaustion. Further, the four-minute mile had to be won alone. There could be no team-mates to blame, no coach during half-time to inspire a comeback. One might hide behind the excuses of cold weather, an unkind wind, a slow track, or jostling competition, but ultimately, these obstacles had to be defied. Winning a foot race, particularly one waged against the clock, was a battle with oneself, over oneself.

In August 1952 the battle commenced. Three young men in their early twenties set out to be the first to break the barrier. One of them was Wes Santee, the ‘Dizzy Dean of the Cinders’. Santee was a natural athlete, the son of a Kansas ranch hand, born to run fast. He amazed crowds with his running feats, basked in the publicity, and was the first to announce his intention of running the mile in four minutes. ‘He just flat believed he was better than anybody else,’ said one sportswriter. Few knew that running was his escape from a brutal childhood.

Then there was John Landy, the Australian who trained harder than anyone else and had the weight of a nation’s expectations on his shoulders. The mile for Landy was more aesthetic achievement than foot race. He said, ‘I’d rather lose a 3:58 mile than win one in 4:10.’ Landy ran night and day, across fields, through woods, up sand dunes, along the beach in knee-deep surf. Running revealed to him a self-discipline he never knew he possessed.

And finally there was Roger Bannister, the English medical student who epitomised the ideal of the amateur athlete in a world being overrun by professionals and the commercialisation of sport. For Bannister the four-minute mile was ‘a challenge of the human spirit’, but one to be realised with a calculated plan. It required scientific experiments, the wisdom of a man who knew great suffering, and a magnificent finishing kick.

All three runners endured thousands of hours of training to shape their bodies and minds. They ran more miles in a year than many of us walk in a lifetime. They spent a large part of their youths struggling for breath. They trained week after week to the point of collapse, all to shave off a second, maybe two, during a mile race – the time it takes to snap one’s fingers and register the sound. There were sleepless nights, training sessions in rain, sleet, snow, and scorching heat. There were times when they wanted to go out for a beer or a date yet knew they couldn’t. They understood that life was somehow different for them, that idle happiness would elude them. If they weren’t training or racing or gathering the will required for these, they were trying not to think about training and racing at all.

In 1953 and 1954, as Santee, Landy, and Bannister attacked the four-minute barrier, getting closer with every passing month, their stories were splashed across the front pages of newspapers around the world, alongside headlines of the Korean War, the atomic arms race, Queen Elizabeth’s coronation, and Edmund Hillary’s climb towards the world’s rooftop. Their performances outdrew golf majors, Ashes Tests, horse derbies, football and rugby matches, and baseball pennant races. Stanley Matthews, Ben Hogan, Rocky Marciano, Mike Hawthorn and Surrey County Cricket Club were often in the shadows of the three runners, whose achievements attracted media attention to athletics that has never been equalled. For weeks in advance of every race the headlines heralded an impending break in the barrier: ‘Landy Likely to Achieve Impossible!’; ‘Bannister Gets Chance of 4-Minute Mile!’; ‘Santee Admits Getting Closer to Phantom Mile’. Articles dissected track conditions and the latest weather forecasts. Millions around the world followed every attempt. Whenever any of the runners failed – and there were many failures – he was criticised for coming up short, for not having what it took. Each such episode only motivated the others to try harder.

They fought on, reluctant heroes whose ambition was fuelled by a desire to achieve the goal and to be the best. They had fame, undeniably, but of the three men only Santee enjoyed the publicity, and that proved to be more of a burden than an advantage. As for riches, financial reward was hardly a factor. They were all amateurs. They had to scrape around for pocket change, relying on their hosts at races for decent room and board. The prize for winning a meet was usually a watch or a small trophy. At that time, the dawn of television, when amateur sport was losing its innocence to the new spirit of win-at-any-cost, these three strove only for the sake of the attempt. The reward was in the effort.

After four soul-crushing laps around the track, one of the three finally breasted the tape in 3:59.4, but the race did not end there. The barrier was broken, and a media maelstrom descended on the victor, yet the ultimate question remained: who would be the best when they toed the starting line together?

The answer came in the perfect mile, a race no longer fought against the clock, rather against one another. It was won with a terrific burst around the final bend in front of an audience that spanned the globe.

If sport, as a chronicler of this battle once said, is a ‘tapestry of alternating triumph and tragedy’, then the first thread of this story begins with tragedy. It occurred in a race 120 yards short of a mile, at the Olympic 1,500m final in Helsinki, Finland, almost two years to the day before the greatest of triumphs.

I (#ulink_f6c8016b-4e92-5c89-97db-46e3ac82adfd)

A REASON TO RUN (#ulink_f6c8016b-4e92-5c89-97db-46e3ac82adfd)

1 (#ulink_8f274829-0b36-5658-b313-b28f65adf2b8)

I have now learned better than to have my races dictated by the public and the press, so I did not throw away a certain championship merely to amuse the crowd and be spectacular.

Jack Lovelock, 1,500m gold medallist, 1936 Olympics

On 16 July 1952 at Motspur Park, south London, two men were running around a black cinder track in singlets and shorts. The stands were empty, and only a scattering of people watched former Cambridge miler Ronnie Williams as he tried to stay even with Roger Bannister, who was tearing down the straight. It was inadequate to describe Bannister as simply ‘running’: eating up yards at a rate of seven per second, he was moving too fast to call it running. His pacesetter for the first half of the time trial, Chris Chataway, had been exhausted, and the only reason Williams hadn’t folded was that all he needed to do was maintain the pace for a lap and a half. What most distinguished Bannister was his stride. Daily Mail journalist Terry O’Connor tried to describe it: ‘Bannister had terrific grace, a terrific long stride, he seemed to ooze power. It was as if the Greeks had come back and brought to show you what the true Olympic runner was like.’

Bannister was tall – six foot one – and slender of limb. He had a chest like an engine block and long arms that moved like pistons. He flowed over the track, the very picture of economy of motion. Some said he could have walked a tightrope as easily, so balanced and even was his foot placement. There was no jarring shift of gears when he accelerated, as he did in the last stage of the three-quarter-mile time trial, only a quiet, even increase in tempo. Bannister loved that moment of acceleration at the end of a race, when he drew upon the strength of leg, lung, and will to surge ahead. Yes, Bannister ran, but it was so much more than that.

As he sped to the finish with Williams at his heels, Bannister’s friend Norris McWhirter prepared to take the time on the sidelines. He held his thumb firmly on the stopwatch button, knowing that because of the thumb’s fleshiness, having it poised only lightly added a tenth of a second at least. Bannister shot across the finish; McWhirter punched the button. When he read the time, he gasped.

Norris and his twin brother Ross had been close to Bannister since their days at Oxford University. They were three years older than the miler, having served in the Royal Navy during the Second World War, but they had been Blues together in the university’s athletic club. Norris had always known there was something special about Roger. Once, during an Italian tour with the Achilles Club (the combined Oxford and Cambridge athletic club), which Bannister had dominated, McWhirter had looked over with amazement at his friend sleeping on the floor of a train heading to Florence and thought, ‘There lies the body that perhaps one day will prove itself to possess a known physical ability beyond that of any of the one billion other men on earth.’ Sure enough, as McWhirter stared down at his stopwatch that July afternoon, he could hardly believe the time: Bannister had run three-quarters of a mile in 2:52.9, four seconds faster than the world record held by the great Swedish miler Arne Andersson.

After gathering his breath, Bannister walked over to see what the stopwatch read. Cinders clung to his running spikes. At the time, athletics shoes were simply a couple of pieces of thin leather that moulded themselves so tightly to the feet when the laces were drawn that one could see the ridges of the toes. The soles were embedded with six or more half-inch-long steel spikes for traction. Running surfaces, too, had advanced very little over the years. They were mostly oval dirt strips layered on top with ash cinders that were taken from boilers at coal-fired electricity plants. Track quality depended on how well the cinders were maintained, since in the sun they became loose and tended to blow away, and when it rained the track turned to muck. Motspur Park’s track benefited from the country’s best groundskeeper, and it was one of the fastest, which was why Bannister had chosen it for this time trial.

He always ran a three-quarter-mile trial before a race to fix in his mind his fitness level and pace judgement. This trial was particularly important because in ten days’ time, given that he qualified in the heats, he would run the race he had dedicated the past two years to winning: the Olympic 1,500m final. A good time this afternoon was crucial for his confidence.

‘Two fifty-two nine,’ McWhirter said.

Bannister was taken aback. Williams and Chataway were just as incredulous. The time had to be wrong.

‘At least, Norris, you could have brought a watch we could rely on,’ Bannister said.

McWhirter was cross at such a suggestion. But he knew one way to make sure his stopwatch was accurate. He dashed to the telephone booth near the concrete stadium stands, put in a penny coin, and dialled the letters T-I-M. The phone rang dully before a disembodied voice came on to the line, tonelessly saying, ‘And on the third stroke, the time will be two thirty-two and ten seconds – bip–bip–bip – and on the third stroke, the time will be two thirty-two and twenty seconds – bip–bip–bip …’ Norris checked his stopwatch: it was accurate.

After McWhirter returned and confirmed the result to the others, they agreed that Bannister was certain of a very good show in Helsinki. They dared not predict a gold medal, but they knew that Bannister considered a three-minute three-quarter mile the measure of top racing shape. He was now seven seconds under this benchmark. All of his training for the last two years had been focused on reaching his peak at exactly this moment – and what a peak it was. He was in a class by himself. The critics – coaches and newspaper columnists – who had condemned him for following his own training schedule and not running in enough pre-Olympic races would soon be silenced.

There was, however, a complication, which McWhirter had yet to tell Bannister. As a journalist for the Star, McWhirter kept his ear to the ground for any breaking news, and he had recently heard something very troubling from British Olympic official Harold Abrahams. Because of the increased number of entrants, a semi-final had been added to the 1,500m contest. In Helsinki, Bannister would have to run not only a first-round heat, but also a semi-final before reaching the final.

The four men bundled into McWhirter’s black Humber and headed back to the city for the afternoon.

When Bannister was not racing around the track, where he looked invincible, the 23-year-old appeared slighter. In trousers and a shirt, his long corded muscles were no longer visible, and it was his face one noticed. His long cheekbones, fair complexion, and haphazard flop of straw-coloured hair across the forehead gave him an earnest expression that turned boyish when he smiled. However, there was quiet aggression in his eyes. They looked at you as if he was sizing you up.

As Norris McWhirter turned out of the park, he finally said, ‘Roger … they put in a semi-final.’

They all knew what he meant: three races in three days. Bannister had trained for two races, not three. Three required a significantly higher level of stamina; Bannister had concentrated on speed work. With two prior races, the nervous energy he relied on would be exhausted by the final – if he made the final. It was as if he were a marksman who had precisely calibrated the distance to his target, then found that his target had been moved out of range. Now it was too late to readjust the sights.

Bannister looked out the window, saying nothing. Away from Motspur Park with its trees and long stretches of open green fields, the roads were choked with exhaust fumes and bordered by drab houses and abandoned lots overgrown with weeds. The closer they got to London, the more they could see of the war’s destruction, the craters and bombed-out walls that had yet to be bulldozed and rebuilt. A fine layer of soot clouded the windows and greyed the rooftops.

The young miler didn’t complain to his friends, although they knew he was burdened by the fact that he was Britain’s great hope for the 1952 Olympics. He was to be the hero of a country in desperate need of a hero.

To pin the hopes of a nation on the singlet of one athlete seemed to invite disaster, but Britain at that time was desperate to win at something. So much had gone wrong for so long that many questioned their country’s standing in the world. Their very way of life had come to seem precarious. ‘It is gone,’ wrote James Morris of his country in the 1950s. ‘Empire, forelock, channel and all … the world has overtaken [us]. We are getting out of date, like incipient dodos. We have reached, none too soon, one of those immense shifts in the rhythm of a nation’s history which occur when the momentum of old success is running out at last.’ The First World War had put an end to Britain’s economic and military might. The depression of the 1930s slowly drained the country’s reserves, and its grasp on India started to slip. Britain moved reluctantly into the Second World War, knowing it couldn’t stand alone against Hitler’s armies. Once the British joined the fight, they had to throw everything into the effort to keep the Nazis from overrunning them. When the war was over they discovered, like the Blitz survivors who emerged onto the street after the sirens had died away, that they were alive, but that they had grim days ahead of them.

Grim days they were. Britain owed £3 billion, principally to the United States, and the sum was growing. Exports had dried up, in large part because half of the country’s merchant fleet had been sunk. Returning soldiers found rubble where their homes had once stood. Finding work was hard, finding a place to live harder. Shop windows remained boarded up. Smog from coal fires deadened the air. Trash littered the alleys. There were queues for even the most basic staples, and when one got to the front of the line, a ration card was required for bread (three and a half pounds per person per week), eggs (one per week), and everything else (which wasn’t much). Children needed ration books to buy their sweets. Trains were overcrowded, hours off schedule, and good luck finding a taxi. If this was victory, asked a journalist, why was it ‘we still bathed in water that wouldn’t come over your knees unless you flattened them?’

And the blows kept falling. The winter of 1946–7, the century’s worst, brought the country to a standstill. Blizzards and power outages ushered in what the Chancellor of the Exchequer called the ‘Annus Horrendus’. It was so cold that the hands of Big Ben iced up, as if time itself had stopped. Spring brought severe flooding, and summer witnessed extremely high temperatures. To add to the misery, there was a polio scare.

Throughout the next five years, ‘austerity’ remained the reality, despite numerous attempts to put the country back in order. Key industries were nationalised, and thousands of dreary prefabricated houses were built for the homeless. In 1951 the Festival of Britain was staged to brighten what critic Cyril Connolly deemed ‘the largest, saddest and dirtiest of the great cities, with its miles of unpainted half-inhabited houses, its chopless chop-houses, its beerless beer pubs … its crowds mooning around the stained green wicker of the cafeterias in their shabby raincoats, under a sky permanently dull and lowering like a metal dish-cover’. The festival, though a nice party, was an obvious attempt to gloss over people’s exhaustion after years of hardship. Those who were particularly bitter said that the festival’s soaring Skylon was ‘just like Britain’, standing there without support. To cap it all, on 6 February 1952 London newspapers rolled off the presses with black-bordered pages: the king was dead. Crowds wearing black armbands waited in lines miles long to see George VI lying in state in Westminster Abbey. As they entered the hall, only the sounds of footsteps and weeping were heard. A great age had passed.

The ideals of that bygone age – esprit de corps, self-control, dignity, tireless effort, fair play, and discipline – were often credited to the country’s long sporting tradition. It was said that throughout the empire’s history, ‘England has owed her sovereignty to her sports.’ Yet even in sport she had recently faltered. The 1948 Olympic Games in London had begun badly when the Olympic flame was accidentally snuffed out on reaching England from Greece. America (the ‘United, Euphoric, You-name-it-they-had-it States’ as writer Peter Lewis put it) dominated the games, winning thirty-eight gold medals to Britain’s three. After that the country had to learn the sour lesson of being a ‘good loser’ in everything from football and cricket to rugby, boxing, tennis, golf, athletics, even swimming the Channel. It looked as though the quintessential English amateur – one who played his sport solely for the enjoyment of the effort and never at the cost of a complete life – simply couldn’t handle the competition. He now looked outdated, inadequate, and tired. For a country that considered its sporting prowess symbolic of its place in the world, this was a distressing situation.

Roger Bannister, born into the last generation of the age that ended with George VI’s death, typified the gentleman amateur. He didn’t come from a family with a long athletic tradition, nor one in which it was assumed he would go to Oxford, as he did, to study medicine and spend late afternoons at Vincent’s, the club whose hundred members represented the university’s elite.

His father, Ralph, was the youngest of eleven children raised in Lancashire, the heart of the English cotton industry and an area often hit by depression. Ralph left home at 15, took the British Civil Service exams, qualified as a low-level clerk, and moved to London. Over a decade later, after working earnestly within the government bureaucracy, he felt settled enough to marry. He met his wife Alice on a visit back to Lancashire, and on 23 March 1929 she gave birth to their first son and second child, Roger Gilbert. The family lived in a modest home in Harrow, north-west London. Forced to abandon their education before reaching university (his mother had worked in a cotton mill), Roger’s parents valued books and learning above everything else. All Roger knew of his father’s athletic interests was that he had once won his school mile and then fainted. Only later in life did he learn that his father carried the gold medal from that race on his watch chain.

Bannister discovered the joy of running on his own while playing on the beach. ‘I was startled and frightened,’ he later wrote of his sudden movement forward on the sand in bare feet. ‘I glanced round uneasily to see if anyone was watching. A few more steps – self-consciously … the earth seemed almost to move with me. I was running now, and a fresh rhythm entered my body.’ Apart from an early passion for moving quickly, nothing out of the ordinary marked his early childhood. He spent the years largely alone, building models, imagining heroic adventures, and dodging neighbourhood bullies, like many boys his age.

When he was 10 this world was broken; an air-raid siren sent him scrambling back to his house with a model boat secured under his arm. The Luftwaffe didn’t come that time, but soon they would. His family evacuated to Bath, but no place was safe. One night, when the sirens sounded and the family took refuge underneath the basement stairs of their new house, a thundering explosion shook the walls. The roof caved in around them, and the Bannister family had to escape to the woods for shelter.

Although the war continued to intrude on their daily lives, mostly in the form of ration books and blacked-out windows, Roger had other problems. As an awkward, serious-minded 12-year-old who was prone to nervous headaches, he had trouble fitting in among the many strangers at his new school in Bath. He won acceptance by winning the annual cross-country race. The year before, after he had finished eighteenth, his house captain had advised him to train, which Bannister had done by running the two-and-a-half-mile course at top speed a couple of times a week. The night before the race the following year he was restless, thinking about how he would chase the ‘third form giant’ who was the favourite. The next day Bannister eyed his rival, noting his cockiness and general state of unfitness. When the race started, he ran head down and came in first. His friends’ surprise would have been trophy enough, but somehow this race seemed to right the imbalance in his life as well. Soon he was able to pursue his studies, as well as interests in acting, music, and archaeology, without feeling at risk of being an outcast – as long as he kept winning races. Possessed of a passion for running, a surfeit of energy, and a preternatural ability to push himself, he won virtually all of them, usually wheezing for breath by the end.

Before he left Bath to attend the University College School in London, the headmaster warned, ‘You’ll be dead before you’re 21 if you go on at this rate.’ His new school had little regard for running, and Bannister struggled to find his place once again. He was miserable. He tried rugby but wasn’t stocky or quick enough; he tried rowing but was placed on the third eight. After a year he wanted out, so at 16 he sat for the Cambridge University entrance exam. At 17 he chose to take a scholarship to Exeter College, Oxford, since Cambridge had put him off for a year. He never had a problem knowing what he wanted.

Bannister intended to study to become a doctor, but he knew he needed a way not only to fit in but to excel among his fellow students, most of whom, in 1946, were eight years older than he, having deferred placement because of the war. A schoolboy among ex-majors and brigadiers, he realised that running was his best chance to distinguish himself. The year before, his father had taken him to see the gutsy, diminutive English miler Sydney Wooderson take on the six-foot giant Arne Andersson at the first international athletics competition since the war’s end. White City stadium, located in west London, was bedlam as Andersson narrowly beat Wooderson. ‘If there was a moment when things began, that was it for me,’ Bannister later said. In a foot race, unlike other sports, greatness could be won with sheer heart. He sensed he had plenty of that.

Before he even unpacked his bags at Oxford, Bannister sought out athletes at the track. He found no one there, but discovered a notice on a college bulletin board for the University Athletic Club. He promptly mailed a guinea to join but received no response. He decided to go running on the track anyway, even though one of the groundskeepers advised, ‘I’m afraid that you’ll never be any good. You just haven’t got the strength or the build for it.’ Apparently the groundskeeper thought everyone needed to look like Jack Lovelock, the famous Oxford miler: short, compact, with thick, powerful legs. The long-limbed, almost ungainly Bannister persisted nonetheless. Three weeks later, having finally received his membership card, he entered the Freshman’s Sport mile wearing an oil-spotted jersey from his rowing days. He thought it best to lead from the start – a strategy he would afterwards discard – and finished the race in second place with a time of 4:52. After the race, the secretary of the British Olympic Association advised him, ‘Stop bouncing, and you’ll knock twenty seconds off.’ Bannister had never before worn running spikes, and their grip on the track had made him, as he later described, ‘over-stride in a series of kangaroo-like bounds’.

The cruel winter of 1946–7, with its ten-foot snowdrifts, meant that someone had to shovel out a path on the track so the athletes could train; Bannister took to the yeoman’s task, and for his effort won a third-string spot in the Oxford versus Cambridge mile race on 22 March 1947. On that dreary spring day, on the very track at White City where he had watched Wooderson compete, Bannister discovered his true gift for running. He stepped up to the mark feeling the pressure to run well against his university’s arch rival. From the start Bannister held back, letting the others set the pace. The track was wet, and the front of his singlet was spotted black with cinder ash kicked up by the runners ahead of him. After the bell for the final lap, Bannister was exhausted but still close enough to the leaders to finish respectably. All of a sudden, though, he was overwhelmed by a feeling that he just had to win. It was instinct, a ‘crazy desire to overtake the whole field’, as he later explained. Through a cold, high wind on the back straight, he increased the tempo of his stride, and to everyone’s shock, team-mates and competitors alike, he surged past on the outside. In the effort inspired by the confluence of body and will, he felt more alive than ever before. He pushed through the tape twenty yards ahead of the others in 4:30.8. It wasn’t the time that mattered, rather the rush of passing the field with his long, devouring stride. This was ecstasy, and it was the first time Bannister knew for sure there was something remarkable in the way he ran – and something remarkable in the feeling that went with it.

After the race he met Jack Lovelock, the gold medallist in the 1,500m at the 1936 Olympics and the former world record holder in the mile. ‘You mean the Jack Lovelock,’ Bannister said on being introduced. Lovelock was a national hero, Exeter graduate, doctor, and blessed with tremendous speed. It didn’t take much insight on his part to see in Bannister the potential resurrection of British athletics.

Bannister didn’t disappoint. On 5 June he clocked a 4:24.6 mile, beating the time set by his hero Wooderson when he was the same age, 18. In the summer Bannister travelled with the English team on its first post-war international tour, putting in several good runs. In November he was selected as a ‘possible’ for the 1948 Olympics, then turned down the invitation. He wasn’t ready, he decided, to some criticism.

It was in his nature to listen to his own counsel, not that of others. He had taken a coach, Bill Thomas, who had once trained Lovelock, but Bannister soon became disgruntled with him. Thomas attended to Bannister on the track while wearing a bowler hat, suit and waistcoat. He barked instructions at the miler on how to hold his arms or how many laps to run during training. When the young miler asked for the reasoning behind the lessons, Thomas simply replied, ‘Well, you do this because I’m the coach and I tell you.’ When Bannister ran a trial and enquired about his time, Thomas said, ‘Oh, don’t worry about that.’ Soon Bannister dropped him, preferring to discover for himself how to improve his performances.

The next year he became Oxford Athletic Club secretary, then quickly its president. He won the Oxford versus Cambridge meet for the second year; he competed in the Amateur Athletic Association (AAA) championships in the summer, learning the ropes of first-class competition. Increasingly the newspapers headlined his name. He even saved the day at the opening ceremony for the Olympics when it was discovered that the British team hadn’t been given a flag with which to march into the stadium. Bannister found the back-up flag, smashing the window of the commandant’s car with a brick to retrieve it.

Four years later, he intended to save the British team’s honour again.

Roger Bannister’s preparations for the Helsinki Games began in the autumn of 1950. He had spent the two previous years studying medicine, soaking up university life, hitch-hiking from Paris to Italy, and going on running tours to America, Greece, and Finland. His body filled out. He won some races and lost others but, importantly, he turned himself from an inexperienced, weedy kid into a young man who clearly understood that Oxford and running had opened up worlds to him that otherwise would have remained closed. He was ready to make his Olympic bid, and afterwards to put away his racing spikes for a life devoted to medicine.

Bannister’s plan was to spend one year competing against the best international middle-distance runners in the world, learning their strengths and weaknesses and acclimatising to different environments. Then, in the year before the Games, he would focus exclusively on training to his peak, running in only a few races so as not to take off his edge. The plan was entirely his own. Having spoken to Lovelock about his preparations for the 1936 Olympics, Bannister felt he needed no other guidance.

First he flew to New Zealand over Christmas for the Centennial Games, where he beat the European 1,500m champion Willi Slijkhuis and the Australian mile champion Don Macmillan, both of whom he was likely to face in Helsinki. His mile time was down to 4:09.9, a reduction of more than forty seconds from his first Oxford race three years earlier. While in New Zealand he visited the small village school Lovelock had attended, noticing that the sapling given to the Olympic gold medal winner had now grown into an oak tree. The symbolism wasn’t lost on him. Back in England Bannister continued his fellowship in medicine through the spring of 1951 at Oxford, where he investigated the limits of human endurance and chatted with such distinguished lecturers as J. R. R. Tolkien and C. S. Lewis. He then flew to Philadelphia to compete in the Benjamin Franklin Mile, the premier American event in middle-distance running. The press fawned over this foil to the American athlete, commenting on his travelling alone to the event: ‘No manager, no trainer, no masseur, no friends! He’s nuts – or he’s good.’ In front of forty thousand American fans, Bannister crushed the country’s two best milers in a time of 4:08.3. The New York Herald Tribune described him as the ‘worthy successor to Jack Lovelock’. The New York Times quoted one track official as saying, ‘He’s young, strong and fast. There’s no telling what he can do.’

The race brought Bannister acclaim back home. To beat the Americans on their own turf earned one the status of a national hero. When he followed with summer victories at the British Games and the AAA championships, it seemed track officials and the press were ready to award him the Olympic gold medal right then and there. They praised his training as ‘exceptional’, an ‘object lesson’. Of his long, fluid stride, the British press gushed that it was ‘immaculate’ and ‘amazing’. He left rivals standing; he was a ‘will-o’-the-wisp’ on the track. After a race that left the crowd laughing at how effortlessly Bannister had won, a British official predicted, ‘Anyone who beats him in the Olympics at Helsinki will have to fly.’

Then the positive press turned quickly to the negative. Following his own plan, Bannister stopped running mile races at summer’s end. Tired from competition, he felt he had learned all he needed during the year and should now dedicate himself to training. When he chose to run the half-mile in an international meet, the papers attacked: ‘Go Back to Your Own Distance, Roger’. This was only the beginning of the criticism, but Bannister remained focused on his goal.

To escape the attention, he journeyed to Scotland to hike and sleep under the stars for two weeks. One late afternoon, after swimming in a lake, he began to jog around to ease his chill. Soon enough he found himself running for the sheer exhilaration of it, across the moor and towards the coast. The sky was filled with crimson clouds, and as he ran, a light rain started to fall. With the sun still warming his back, a rainbow appeared in front of him, and he seemed to run towards it. Along the coast the rhythm of the water breaking against the rocks eased him, and he circled back to where he had begun. Cool, wet air filled his lungs. Running into the sun now, he had trouble seeing the ground underneath his feet, but still he rushed forward, alive with the movement. Finally spent as the sun disappeared from the horizon, he tumbled down a slight hill and rested on his back, his feet bleeding but feeling rejuvenated. He had needed to reconnect to the joy of running, away from the tyranny of the track.

Throughout the winter of 1951–2, Bannister immersed himself into his first year of medical school at St Mary’s Hospital in London, learning the basics of taking a patient history and working the wards. He was, by the way, also training for the Olympics. By the spring he had developed his stamina and began speed work on the track. When he announced that he wouldn’t defend his British mile championship, the athletics community objected. It was unthinkable. He had obligations to amateur sport; he had to prove he deserved his Olympic spot; he must take a coach now; he couldn’t duck his British rivals. Bannister made no big press announcements defending his reasons, he simply stuck to his plan, trusting it. As isolating as this plan was, so far it had taken him exactly where he wanted – so far. Meanwhile, most other athletes trained under the guidance and direction of the British amateur athletics officials.

On 28 May 1952, Bannister clocked a 1:53 half-mile at Motspur Park with his ‘space-eating stride’. Ten days later he entered the mile at the Inter-Hospitals Meet and won by 150 yards. Maybe he knew what he was doing. The press turned to writing that he would silence his critics at Helsinki and that his training was ‘well-advanced’. Compared to those of the top international 1,500m men, his times were sufficient. His ‘pulverizing last lap’ would likely win the day. Even L. A. Montague, the Manchester Guardian’s esteemed athletics correspondent, trotted out to explain that Bannister was the ‘more sensitive, often more intelligent, runner who burns himself up in giving of his best in a great race’. Bannister was Britain’s best chance at the gold medal, and Montague wondered, ‘Do [critics] really think that they suddenly know more about him than he knows himself?’

Although he lost an 800m race at White City stadium in early July, the headlines exclaimed, ‘Don’t worry about Bannister’s defeat – he knows what he is doing!’ Ably assisted by the press, Bannister had painted himself into a corner. He was favoured to bring back gold by everyone from the head of the AAA to revered newspaper columnists – and, by association, by his countrymen as well. Of course, there weren’t going to be any scapegoats if he failed. ‘No alibis,’ as Bannister said himself. ‘Victory at Helsinki was the only way out.’ A part of him suspected that he had manoeuvred himself into this tight position on purpose. Come the Olympic final, he would have an expectant crowd, the rush of competition, two years of dedicated training, the expectation that it was his last race before retirement, and nobody to blame but himself if he lost. This was motivation.

By 17 July most of the British Olympic team had left for Finland, team manager Jack Crump declaring upon arrival in Helsinki, ‘We will not let Britain down.’ But, though he would have to join the team soon, Bannister was still in London. Like a few other athletes, he wanted to avoid the media frenzy in the prelude to the Games, and the inevitable waiting around, worrying about upcoming events. His friend Chris Chataway, the 5,000m hopeful, had also delayed his departure. The two scoured London for dark goggles to curtain the twenty-one hours of Scandinavian daylight. Given that one rarely saw the sun in London, it proved a difficult search. Bannister also sought out a morning newspaper.

It didn’t take him long to find a story headline – ‘Semi-Finals for the Olympic 1,500 Metres’ – that confirmed what Norris McWhirter had told him the day before about the added heat. ‘I could hardly believe it,’ Bannister later explained. ‘In just the length of time it took to read those few words the bottom had fallen out of my hopes.’ Worse, he had drawn a tough eliminating heat in the first round.

As he went about his day in the smog-choked London streets, the crisp air and fast tracks he expected to enjoy in Helsinki seemed threateningly close at hand. One could hardly have blamed him had he not wanted to go at all.

2 (#ulink_a9b8dedb-1d01-5c4b-b44b-c51486fe5dab)

The essential thing in life is not so much conquering as fighting well.

Baron de Coubertin, founder of the modern Olympic Games

In the narrow concrete tunnel, Wes Santee stuck to his position in the seven-man line, waiting to move forward as the first of the American team marched into Helsinki’s Olympic Stadium through the Marathon Gate. The applause from the stands reverberated in the tunnel, sounding as if the whole of mankind had come to watch the opening ceremony parade. Santee, his feet more accustomed to cowboy boots or track spikes, stepped ahead in white patent leather shoes. His outfit was a departure from his typical attire of Western shirts and jeans. Like the rest of his team-mates, he wore a dark flannel jacket with silver buttons, grey flannel slacks, and a poplin hat whose brim he had folded to make it look more like a cowboy hat.

The 20-year-old University of Kansas sophomore towered over most of those around him. At six foot one inch, with much of that height in his legs, he looked the clean-cut American athlete, buzz cut included. His shoulders were wide, and he bristled with energy. His face easily lit with a smile, and he almost always said what he thought, with a Midwestern twang. One had the sense that he wore his emotions out in the open, but that this vulnerability had a limit buttressed with steel.

That afternoon of 19 July 1952, he was nothing but a bundle of nervous anticipation as he moved towards the tunnel’s mouth. Rain streaked across the opening. He peered past it into the stadium, where hundreds of athletes circled the track. They were dressed in a kaleidoscope of colours and styles: pink turbans, flower-patterned shirts, green and gold blazers, black raincoats, orange hats. It was impossible to tell where each team was from because all the flag inscriptions were in Finnish. Santee could not even pronounce the translation for the United States: Yhdysvaltain. The Soviets were already settled on the infield, wearing their cream suits and maroon ties, lined up as neatly as an army regiment. It was their first Olympics since 1912, and they had made no secret of the fact that they were out to beat the Americans.

Finally Santee cleared the tunnel and moved in file towards the track, his head swivelling about to take in the three-tiered stadium and its seventy thousand spectators. It was an awesome sight, like nothing he had ever witnessed. So many people from so many places, charged with excitement and speaking so many different languages. And they had all come this afternoon simply to watch them march around the track, not even to see them compete. On an electric signboard, the likes of which Santee had seen only a few times, were the words Citius, Altius, Fortius – Faster, Higher, Stronger. He had made it. He was an Olympic athlete representing his country.

After marching around the mud-soaked track, he followed the row of athletes to his spot on the infield for the ceremony’s beginning. He felt as if his eyes weren’t wide enough to take in everything happening around him. This was a long way from Ashland, the farming town deep in the south-western part of Kansas where he was raised. The size of the Helsinki stadium alone was enough to marvel at. He remembered arriving at the University of Kansas for the first time and going to the big auditorium for freshman orientation. He’d been with his team-mate Lloyd Koby, who also came from the kind of small town where electricity was just on its way in and a rooster’s crow was the only wake-up call one knew. Koby had looked across the numerous tiers of seats, gauged the height of the rafters, turned to Santee, and said, ‘Boy, this building would hold a lot of hay.’ It was not so much a joke as the only context they knew. But that auditorium was nothing compared to this place, its steep concrete stands seeming to reach the sky.

At a rostrum on the track in front of Santee, the chairman of the organising committee began to speak, first in Finnish, then in Swedish, French, and English, about the Herculean efforts that had gone into these Games. His countrymen had cleared forests, put up hundreds of new buildings of stucco, granite, and steel, enlisted thousands of volunteers, and opened their homes to strangers from around the globe. The stadium in which the opening ceremony was taking place had been the chief target of Russian bombers at the start of the Second World War because of its symbolic value. Now it was once again alive with people, anxious for the competition to commence.

The chairman finished his speech by introducing Finland’s president, who stood at the microphone and announced, ‘I declare the Fifteenth Olympic Games open!’ To the sound of trumpets, the Olympic flag with its five interlocking circles was raised on the stadium flagpole. Then a twenty-one-gun salute boomed. As its echo dissipated, 2,500 quaking pigeons were released from their boxes to swoop and pivot in the air. Santee looked skyward as the birds escaped one by one, carrying the message that the Olympics had begun.

Before the last of them soared away, the scoreboard went blank, and then appeared the words: ‘The Olympic Torch is being brought into the Stadium by … P-A-A-V-O N-U-R-M-I.’ Pandemonium ensued. Santee had passed the bronze statue of Nurmi at the stadium entrance and had seen his classic figure on posters wallpapered throughout Helsinki, but few had expected to see the man himself. Peerless Paavo, the Phantom Finn, the Ace of Abo. Nurmi was a national hero in Finland, the godfather of modern athletics. At one time he owned every record from 10,000m down to 1,500m. At the 1924 Paris Olympics he claimed three gold medals in less than two days. Put simply, he was the greatest. Now bald-headed, slight of stature, and 55 years old, Nurmi ran into the stadium in a blue singlet with the torch in his right hand, his stride as graceful and effortless as ever. Photographers manoeuvred into position. The athletes, Santee included, broke ranks, storming to the track side to catch a glimpse of the unconquerable man.

The fire leaping from the birch torch Nurmi held had been lit in Olympia, Greece, on 25 June and had since weathered a five-thousand-mile journey across land and water. When Nurmi finished his run around the track, as athletes and spectators alike jostled one another to get a better look, he passed the flame to a quartet of athletes at the base of the 220-foot-tall white tower at the stadium’s south end. While they ascended the tower, at the top of which another Finnish champion, Hannes Kolehmainen, waited, a whiterobed choir stood to sing. The stadium was reverently silent. Kolehmainen took the torch and tilted it to light the Olympic flame, which would burn until the Games ended.

Santee and the other athletes returned to their places in the field. From a distance each team looked uniform, its athletes dressed in matching outfits and standing side by side. On closer inspection, they were an odd assembly of men and women: stocky wrestlers, tall sprinters, wide-shouldered shot-putters, cauliflower-eared boxers, miniature gymnasts, crooked-legged horsemen, and weather-beaten yachtsmen – all with their own ambitions for victory in the days ahead. As Santee stood in the middle of this medley of people, looking at the Olympic flame and hearing the jumble of voices all around him, the strangeness of the scene overwhelmed him. He had been overseas only one other time. Except for travelling to athletics meets, he had never left the state of Kansas. Now he was in this enormous amphitheatre in a country where night lasted only a few hours. He didn’t have his coach with him. He had few friends among the athletes. He had rarely faced international competition. He was scheduled to run in the 5,000m even though the 1,500m was his best distance. Filled with these thoughts, Santee gulped. The tightness in his throat felt like a stone. Indeed, he was a long way from Kansas now.

Had his father had his way, in the summer of 1952 Wes would still have been pitching hay, fixing fence posts, and ploughing fields back in Ashland. Most fathers want their sons to have a better life, but Wes Santee didn’t have such a dad.

David Santee was born in Ohio in the late 1800s. He lived a helter-skelter childhood, never advancing past the second grade (for 7- to 8-year-olds). He was a keen braggart and adept at the harmonica, but his only employable skill was hard labour. Over six feet tall and weighing 2201b, he had the size for it. His cousin married a ranch owner named Molyneux in western Kansas, and David Santee went out to work the eight thousand acres as a hired hand. He met Ethel Benton, a tall, gentle woman who had studied to be a teacher, on a blind date. They were soon married, and shortly afterwards expecting the first of three children. On 25 March 1932, the town doctor was called to the ranch to deliver Wes Santee. He came into the world kicking.

Santee was raised on the Molyneux cattle and wheat ranch five miles outside Ashland. It was practically a pioneer’s existence, with an outhouse, no running water, no electricity. If you wanted to listen to the radio, you had to hook it up to the car battery. Farm life was vulnerable to the often cruel hand of nature. The Santees lived through the drought of the Dust Bowl years, when sand squeezed through every crack in the house and made the sky so dark that the chickens went to roost in mid-afternoon. They survived tornados and storms of grasshoppers that ate everything they could chew, including the handle of a pitchfork left out against a fence post. In good times and bad, Mr Molyneux ruled the ranch. He liked the Santee boy’s spirit and was more a father to Wes than his own ever was. Molyneux was a successful rancher and businessman; he owned Ashland’s dry goods store and enjoyed taking the boy into town to buy him a double-dip ice cream cone at the drugstore. But Molyneux died when Wes was in the fourth grade, and by the age of 10 his happy childhood had ended abruptly. From that point on he was his father’s property, suffering his bad temper while working a man’s day on the ranch. His only freedom was running.

For Santee, running was play. He ran everywhere. ‘I just don’t like to fiddle around,’ he said. ‘If I was told to get the hoe, I’d run to get it. If I had to go to the barn, I’d run.’ The only bus in town was a flat-bed truck, so instead of riding, Santee ran the five miles to school. When he returned in the early afternoon, he ran from his house into the fields to help with the ploughing or to corral one of the four hundred head of cattle. At dusk, when his father called it a day, an exhausted Santee didn’t walk home for supper, he ran – fast, wearing his cowboy boots. As the distance from his father lengthened, a weight lifted from his shoulders, and by the time he had washed up and changed clothes he was as fresh as if he hadn’t worked at all.

Later, when a remark, a look, or seemingly nothing at all set off his father’s rage, this freshness was torn from Wes. He took the brunt of his father’s anger, saving his younger brother Henry, who suffered from rickets as a child, and his younger sister Ina May from the worst of it. David Santee dispensed his cruelty with forearm, fist, rawhide buggy whip, or whatever else was at hand. Once it was a hammer. Wes considered himself lucky that his old man didn’t drink or the situation could have been really bad. Some sons of abusive fathers want to become big enough to fight back; Santee wanted to become fast enough to get away.

Very early on he recognised that he had a gift for running. He was never very good in the sprint, but if the game was to run around the block twice, he always won. In eighth grade, when Wes was in his early teens, the high-school coach came down to evaluate which kids were good at which sports. That was how a small town developed its athletes. The coach threw out a football to see who threw or kicked it the furthest, threw out a basketball to see who made a couple of jump shots. Then he told Santee and the other twenty kids in his class to run to the grain elevator. Within a few hundred yards Santee was all alone and knew he had the others whipped. This was ‘duck soup’ he said to himself as he ran to the grain elevator and back and took a shower before the others had returned. Most walked half the distance.

When a new kid named Jack Brown, who was rumoured to be quite a runner, arrived in town, the townspeople urged Santee to race him. The first day of his freshman year, Santee joined Brown at the starting line of the half-mile track used for horse races and almost lapped him by the finish. It felt good to be better than everybody else at something. What had started as a combination of fun – running to chase mice or the tractor – and a means to escape his father’s clutches had now become a way to excel. Each race he won bolstered his pride.

J. Allen Murray was there to help him on this path. Murray was Ashland’s high-school track and field coach (as well as history teacher and basketball/football coach). He believed Santee could be the next Glenn Cunningham, the most famous United States middle-distance runner and a Kansas native. The problem was that Santee barely had enough time for classes, let alone running, because his father wanted him home to work. Murray told Wes that if he didn’t have time to train, he should just continue to run everywhere he went. That was fine with Santee.

Finally the time came for his first track meet. Scheduled for a Saturday, the meet was delayed until Monday because of a thunderstorm. Unfortunately, Santee worked on Mondays, and he knew his father would object to losing an afternoon of his free labour. Murray told him he would take care of it. The next evening he walked up the steps to the Santees’ house. He had invited himself to dinner. Wes’s father normally greeted visitors with a .22-calibre pistol and an offer of five minutes to get off his property. This time David Santee at least pushed open the door, but his hospitality ended there. Through dinner and dessert, Coach Murray explained to Wes’s parents why they should allow their son to attend the meet – how it was good for the boy to be challenged in competition. David Santee didn’t utter a word the entire evening: not a yes, not a no. Murray left without an answer, and Wes disappeared into the fields afterwards. Alone in the dark, he clawed at the dirt and grass, wondering how he would ever get out of this place. If he hadn’t learned to hate his father before this night, he did so now.

The next day Coach Murray told him to get up early on Monday to do his chores; he would pick him up at seven o’clock. Santee rose at four, hauled feed, milked the cows, and did everything required of him before his coach arrived. David Santee was working in the fields and thought his son had simply left for school. It was the first time Wes had left the county, and although he was the youngest in the mile race, unaware of competition tactics and scared after having disobeyed his father, he placed third. He was awarded a red ribbon and could barely stand still with the excitement. But then he had to go home. When he entered the house, his father was sitting at the table. From the grim look on his face he obviously knew that Wes had gone to the meet.

‘I won third place,’ Wes said with sheepish excitement.

‘If you have time to miss school and do all this’ – his father bit off each word – ‘then you have time to get all the rest of the ploughing done.’

For some eighteen hours, Wes Santee sat on the tractor, ploughing miles of fields without a break for lunch, and certainly not for school. His throat burned from thirst, his spine ached from the jarring movements of the tractor on uneven terrain, and his hands were rubbed raw from gripping the wheel. Working from dawn until ten o’clock at night, Wes finished two days of ploughing in one. As a man who spent most of his youth labouring on the farm, he would remember that day as the hardest he had ever endured. When he finally returned to school, Murray asked if he was all right. Santee nodded. Murray then asked him if he wanted to go to the next meet in Mead, Kansas. Santee said yes.

After Wes left, Murray called the ranch to say one thing to Santee’s father: ‘I want you to bring your truck in and haul some kids to Mead.’ David Santee didn’t reply, but the tone in Coach Murray’s voice made him understand that he didn’t have a choice in the matter. Like most bullies, David Santee folded when someone finally stood up to him. The next week he showed up on time with his truck, and though it angered him that his son was wasting time that would be better spent on the ranch, he never got in the way of Wes’s running again.

Over the next four years, Wes Santee scorched around tracks throughout Kansas. He won two state mile championships, broke Glenn Cunningham’s state high-school record, became the favourite son of Ashland, and was targeted by college track recruiters from coast to coast. He had found his way out, and now there was nothing that could stand in his way. He trained as much as possible, studied hard to keep his grades up, and decided not to let things get too far with his high-school girlfriend because recruiters were not interested in athletes with wives or children. Shutting himself down with her was not easy, but he had to get out of Ashland.

When Bill Easton, the University of Kansas track and field coach, offered him a scholarship in 1949, Santee accepted. Over the previous two years Easton had won his confidence, probably because he was everything Santee’s father was not: he wore a coat and tie, spoke intelligently, won friends easily, and backed up his words with action. Under Easton’s guidance and encouragement, the KU track team had become one of the country’s best.

The summer before he left for college, Wes had his last confrontation with his father. While he dug yet another six-foot-deep hole in the hard ground for the soon-to-arrive electricity poles, his father started pounding on his back with his fists because he was digging too slowly. That was it. The 17-year-old, his shirt soaked with sweat and hands blistered from the work, stormed back to the house, informed his mother he was leaving, and said goodbye to Henry and Ina May. In the stable, he saddled Bess, the horse his father had given him, and put a halter on a second mare, which Wes had yet to name (a local farmer had given her to Wes in exchange for breaking some horses). He then led his two horses towards the front gate, a cloud of dust from their hooves trailing behind them.

Suddenly, his father appeared from behind the barn and blocked his way. ‘You’re not taking that horse anywhere,’ he said, gesturing towards Bess.

Sensing the coiled violence in the rigid way his father stood in front of him, Wes grimly said ‘Okay’ and unstrapped his saddle from Bess. He then threw it over the other horse, which had never been ridden before, and led her through the gate, leaving his father without a goodbye. When he was two hundred yards away, Santee carefully hoisted himself up on the horse and rode into town. He stayed with a friend who owned the local ice plant and had once told him that he could stay with him if things ever got too bad at the ranch. Santee lived there until college began.

In Lawrence, Santee fell under the protection of Bill Easton. The coach invited the youth, who had almost nothing with him but the clothes on his back, to stay at his house until his dormitory was ready. Santee might have been bold-talking and powerful, but he needed someone to care for him. The first morning, over a breakfast of bacon and eggs, Easton told Santee that he needed to set a good example and help lead the team. Easton spoke to him like an equal, and Santee listened.

Coach Murray had given him the opportunity to run; Coach Easton showed Santee how to turn his raw talent as a runner into greatness. It had little to do with changing his short, clipped stride, which had become ingrained in his youth while running along plough furrows and through pastures where a long stride would have been dangerous on the uneven terrain. Santee did not bring his arms back in a normal long arc, nor drive to the extreme with his kicking foot like most distance runners. Instead he had the quick arm swing and knee action of a sprinter. But with his native speed, coordination, long legs, strong shoulders, and ability to relax, he was able to sustain this sprinter style over long distances. Easton was convinced that reshaping his stride into a more classical motion would do more harm than good, so he taught Santee to harness his power through training, pace judgement, and focus. Soon enough, seniors on his team were struggling to keep up with him in practice and competition.

Led by Santee, the freshman squad won the Big Seven cross-country and indoor championships – the league that comprised the biggest and best colleges in sport in the Midwest, namely Kansas State, Iowa State, University of Missouri, University of Colorado, University of Nebraska and University of Oklahoma alongside University of Kansas. Santee set the national collegiate two-mile record in 9:21.6 and began to win headlines as the ‘long-legged loper’ who would ‘play havoc’ with most, if not all, of Glenn Cunningham’s records by the time he was finished. In the spring of 1951, at the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) championships, he took seventeen seconds off the 5,000m record in the junior division, and the next day he placed second in the senior division. By the end of his freshman year, his mile time hovered in the four-minute teens (4:15, 4:16, 4:17). That summer he earned a spot on an AAU-sponsored tour to Japan and found himself running in Osaka, Sapporo, and Tokyo. There he met the American half-miler Mai Whitfield who had won two gold medals at the 1948 Olympic Games. While some athletes were hesitant to share a hotel room with the black track star, Santee gladly jumped at the opportunity. Whitfield taught the young miler to make sure to keep his toes pointed straight ahead when striding, so as not to lose even a quarter inch of distance with each stride. He also explained to Wes that a miler had the time and physical reserves to make only one offensive and one defensive move in the course of a race. When Santee returned to Kansas in August, he felt certain he was ready for more international competition. He announced to local reporters, ‘I want to make the Olympic team and go to Helsinki, Finland.’

In his second, or sophomore, year this ‘sinewy-legged human jet’, as one reporter described Santee, proved that he was on his way. Some began to compare him to Emil Zatopek, the Czech star who ran everything from the mile to the marathon at world-class levels. This was the level of enthusiasm Santee generated on and off the track. He loved racing in front of large crowds and never tired. His talent just barely outmeasured his confidence. On a flight to one meet, a Kansas Jayhawks team-mate held out a newspaper article to show Wes. ‘Look what it says here … [Santee’s college competitor] Billy [Herd] hasn’t been beaten in any kind of a race for almost two years. That includes relay carries … He’s gobbled up some pretty good boys too, Wes.’

Santee stretched his boots out into the aisle. ‘Yeah, he’s a good boy. But he hasn’t tried to digest me yet.’

In two-mile races during his sophomore year, Santee lapped his competitors. In cross-country meets he was slipping into his sweats before other runners had finished. During the indoor season he set record after record in the mile, leading his team to a host of dual meet victories. It was almost too easy. On campus he ran from class to class, and professors set their watches by the precise time at which he started his training sessions.

In April 1952 at the Drake University Relays in Des Moines, Iowa, one of the year’s most important outdoor track meets, Santee anchored the four-mile relay for his team. When the baton was passed to him, Georgetown’s Joe LaPierre was some sixty yards ahead. Santee blazed three 62-second quarter-miles, yet had trouble gaining ground because LaPierre was running brilliantly himself. As Santee sped into the first turn of the last lap, Easton yelled out, ‘He’s wilting in the sun!’ Santee was finally gaining. Stride after stride he closed the gap. When he burst through the tape yards ahead of LaPierre, setting a national collegiate mile record in 4:06.8, Wes Santee had officially arrived. ‘Santee’s not human,’ said the Georgetown coach. The Des Moines Register quipped, ‘Santee stuck out above every other athlete like the Aleutian Islands into the Bering Sea.’ The national papers picked up the best quote, from the Drake coach: ‘Santee is the greatest prospect for the four-minute mile America has yet produced. He not only has the physical qualifications, but the mental and spiritual as well.’

But first Santee turned his sights to the Olympics. As holder of national titles in the 1,500m and the 5,000m, he by right qualified for the American trial in each. In mid-June he went to California with Easton to spend a week training. They decided together that he should participate in both trials. ‘I just want to make the Olympic team,’ he told his coach. ‘Time or race isn’t important.’ On 27 June, at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, Santee placed second in the 5,000m trial, guaranteeing a trip to Helsinki. That night he dined on his customary steak and potato dinner and enjoyed quiet conversation with Easton back at the hotel. The next day, braving one of the coldest June days in Los Angeles history, he readied himself for the 1,500m trial in front of forty-two thousand spectators. Santee looked around for Easton, but couldn’t find him. A whistle was blown, the race called, and Santee approached the starting line alongside milers Bob McMillen and Warren Druetzler, both of whom he was sure he could beat. In the programme listing the qualifiers for the 3.40 p.m. race, Santee was predicted to ‘win as he pleases – he has all year’. He was revved to go.

Suddenly, two AAU officials grabbed his arm and shuffled him off the track before he could protest. ‘Wes, they’re not going to let you run,’ one official said.

‘What do you mean?’ Santee asked, shrugging off their hold on him. ‘What’s going on?’

Out of the corner of his eye he saw Easton running across the field. Though wearing a jacket, tie, and dress shoes, he was moving fast.

The race starter called, ‘Runners to your mark!’ and then the gun fired. Santee watched helplessly as the trial started without him.

Easton finally made it to his side. ‘Wes, I’m sorry. We’ve been in a meeting for over an hour and they’re saying you’re not good enough to run both races, and they won’t let you drop out of the 5,000 to run the 1,500.’

This wasn’t right. Only the previous week he had run the third fastest 1,500m time in AAU history: 3:49.3. It was the fastest time by an American in years. Santee welled with anger, and with balled fists looked ready to act out his frustration.

Easton pulled him to one side. The coach had the stocky build of a wrestler, and even then, in his late forties with a fleshy, oval face, he looked capable of stopping this tall athlete if necessary. His voice was calm. ‘They told me you were only 19 [sic] – not good enough to run the 5,000 against Zatopek followed up with the 1,500.I told them we don’t particularly want to run the 5,000; we want to run the 1,500. Their only response was, “You qualified for that, and you have to stay with it.”’

There was nothing to be done. Easton knew that no Olympic rule forbade an athlete from participating in two events. If he qualified, he qualified. Those were the rules, but the AAU ran the show, and if a rule interfered with what the AAU wanted, its leader either ignored the rule or changed it. This was the first time, yet unfortunately not the last, that the AAU would stand in Santee’s way. Yes, he was off to Helsinki to race in the 5,000m, but his best chance of coming home with a medal was in the 1,500m.

The three weeks between the trial and the opening ceremony in Helsinki was a whirlwind. Santee nearly died on a flight from Los Angeles to St Louis when the plane carrying America’s Olympic athletes went into a tailspin and passengers were thrown from their seats. When the plane finally righted itself, the preacher and polevaulter Bob Richards walked down the aisle asking for confessions. After a long layover in St Louis, they arrived in New York. Santee participated in the national TV show Blind Date, hosted by Arlene Francis, as well as the first Olympic telethon with Bob Hope and Bing Crosby. He ran in an exhibition three-quarter-mile race on Randall’s Island and set a new American record of 2:58.3, not to mention leaving the Olympic 1,500m qualifiers far behind. The effort was born of frustration: to show the AAU officials his speed and prove their decision wrong. After a flurry of press interviews, he flew from New York to Newfoundland, then to London and, finally, to Helsinki. By the time Santee arrived in Finland he was a jumble of excitement, jet lag, hope, aggravation, patriotism, fear, and confusion – a very different cocktail of emotions from what he needed to perform at his best.

But there he was at the opening ceremony, right in the middle of it all and wanting to prove he deserved to stand side by side with the best runners in the world. When the ceremony ended, the 5,870 athletes from sixty-seven nations filed out of the stadium, soaked and cold. Santee had only a few more days to pull himself together for his qualifying round. His legs had never failed him before, and no matter the obstacle or his state of mind, he expected them to see him through once again.

3 (#ulink_46dced30-dc4a-593d-8aa3-0ddcd97e383d)

To be great, one does not have to be mad, but definitely it helps.

Percy Cerutty, Australian athletics coach

All was quiet in Kapyla, the Olympic village in a forest of pine trees twenty miles outside Helsinki. John Landy and three of his four room-mates – Les Perry, Don Macmillan, and Bob Prentice – lay in their iron-framed beds. The Arctic twilight crept in around the edges of the window, the sheets were as coarse as burlap, and the piles of track clothes and shoes reeked, but the Australians were resting easily, exhausted from being thousands of miles from home and trying to prepare for the most important athletics competition of their lives. In the days before an Olympian’s event, he felt as if he were looking over the edge of a cliff; the nerves, upset stomach, and general unease took a lot out of an athlete. The anticipation was almost as trying as the event itself. Sleep was the only relief on offer, if one could finally fall asleep.

‘Wake up! Wake up! You don’t need all this sleep!’ Percy Cerutty yelled as he burst into the room, swinging the door wide open and switching on the lights.

‘Bloody hell, Percy!’ groaned one of his athletes. ‘Thanks for waking us.’

‘You blokes don’t need all this sleep,’ their coach shouted back. At 57, Cerutty was a whirling dervish, a short, fit man with a flowing white mane of hair, goatee, toffee-coloured face, blue eyes, and the kind of voice that could wake the dead when raised. It was often raised.

‘All what sleep?’ his athletes retorted.

‘Ah, you’re hiding in here. You’re avoiding reality!’ Cerutty bounced around the floor, kicking up little wakes of cement dust. ‘The world is gathered here just outside that doorway, and all you fellas can think of is sleep. Sleep won’t get you anywhere.’ He was really getting going now. When Cerutty started a rant, he went on for a while. They had to stop him.