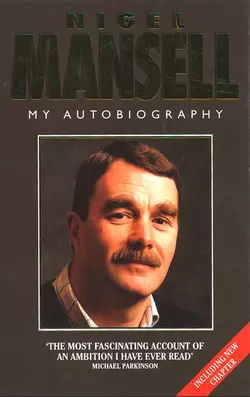

Mansell: My Autobiography

Nigel Mansell

The ebook edition of Nigel Mansell’s bestselling autobiography is an absorbing account of one man's rollercoaster ride to the top.Nigel Mansell is one of motor racing's all-time greats. An ordinary bloke who took on the best and most ruthless drivers in the world's most glamorous sport and won; the epitome of speed, daring and sheer bloody determination.His refusal to be beaten endeared him to millions, but few inside the sport or outside it have fully understood what motivates him in his quest to be number one. Here, for the first time Nigel reveals the secrets of his driving technique, his hunger for racing and the psychological approach that helped him outwit legends like Niki Lauda, Nelson Piquet, Alain Prost and Ayrton Senna.

COPYRIGHT (#ulink_4713e0cf-c056-5adf-a463-b775513a2e5d)

Harper

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/)

First published in paperback in 1996

Published in hardback in 1995 by CollinsWillow

Copyright © Nigel Mansell 1996

Nigel Mansell accepts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780002187039

Ebook Edition © JUNE 2016 ISBN: 9780008193362

Version: 2016-05-18

DEDICATION (#ulink_8548d284-7b35-5884-a527-0312bcf2c4c8)

To Rosanne, Chloe, Leo and Greg

for giving me the love, understanding and support

which is so necessary to achieve so much.

Without you, none of this would have been possible.

CONTENTS

Cover (#u9c383919-f421-5e62-a02a-a686e2273f8b)

Title Page (#uab5e3a90-48ad-5fd1-bd60-a4b814fd22c6)

Copyright (#ulink_7ad12a88-c4b4-55fb-9a8a-981053400d5b)

Dedication (#ulink_2c277965-0971-5870-b7a8-b52a921551dd)

Preface (#ulink_9d8f8aea-8d54-5622-bbd7-3160fb4a2324)

Why race? (#ulink_b762ded8-eb2a-5ca1-af7d-0e43053c03b8)

PART ONE: THE SECRET OF SUCCESS (#ulink_fcf31d0f-1732-59d4-a09c-c452a80da4f8)

1. My philosophy of racing (#ulink_bd03f3cd-bbb2-54ab-9c8f-1464f71d742c)

2. The best of rivals (#ulink_c4725f98-5366-5ed0-acd3-85d47217f7a4)

3. The peopleâs champion (#ulink_dff3b050-f427-5ddf-bac6-f239fb74b874)

4. Family values (#ulink_c0592960-aead-51c3-bef7-4f9f7dd8bb6f)

PART TWO: THE GREASY POLE (#ulink_89477007-2304-54f8-9ebc-b21cf11c2996)

5. Learning the basics (#ulink_3aa4ab4f-ee30-50d0-96d0-2cc83a4ba8b3)

6. The hungry years (#ulink_b13f9a42-5d1e-5ae8-9b27-cde912a73ae5)

7. Rosanne (#ulink_654b7bc6-05c9-5550-a09a-7c044a3a5e5d)

8. The big break (#litres_trial_promo)

9. Colin Chapman (#litres_trial_promo)

10. Taking the rough with the smooth (#litres_trial_promo)

11. The wilderness years (#litres_trial_promo)

12. âIâm sorry, I was quite wrong about youâ (#litres_trial_promo)

PART THREE: WINNING (#litres_trial_promo)

13. Making it count (#litres_trial_promo)

14. Keeping a sense of perspective (#litres_trial_promo)

15. Bad luck comes in threes (#litres_trial_promo)

16. Honda (#litres_trial_promo)

17. Forza Ferrari! (#litres_trial_promo)

18. The impossible win (#litres_trial_promo)

19. Problems with Prost (#litres_trial_promo)

20. Building up for the big one (#litres_trial_promo)

21. For all the right reasons (#litres_trial_promo)

22. World Champion at last! (#litres_trial_promo)

23. Driven out (#litres_trial_promo)

24. Saying goodbye to Formula 1 (#litres_trial_promo)

25. The American adventure (#litres_trial_promo)

26. The concrete wall club gets a new member (#litres_trial_promo)

27. âYouâre completely mad, but very quick for an old manâ (#litres_trial_promo)

28. The stand down from McLaren (#litres_trial_promo)

29. Fresh Perspectives (#litres_trial_promo)

Faces in the paddock (#litres_trial_promo)

My top ten races (#litres_trial_promo)

Career highlights (#litres_trial_promo)

Glossary (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

This is a story about beating the odds through sheer determination and self-belief. It is a story about starting with nothing, taking risks and defeating the best racing drivers in the world to rewrite the record books of this most dangerous and glamorous sport.

It is about overcoming the dejection of being injured, having no money and no immediate prospects for the future. And it is about the sheer exhilaration of standing on top of the world and knowing that whatever happens next, no-one can take away from you what you have just achieved.

Nigel Mansell

Woodbury Park, Devon

NIGELâS THANKS

To the late, great Colin Chapman and his wife Hazel for giving me the first opportunity, and to Enzo Ferrari for giving me the most historic drive in motor racing and two years of wonderful memories. To Ginny and Frank Williams and to Patrick Head for the twenty-eight Grand Prix wins and the World Championship in 1992; for six years and four races it was an awful lot of fun. To Paul Newman and Carl Haas for the 1993 IndyCar World Series; and to Honda, Renault and Ford for giving me the power to win â¦

Without all these people and without the manufacturers and associated sponsors, none of the racing achievements in this book would have been possible. Rosanne and I and our family would like to thank you all for your support. A very big thank you.

PREFACE (#ulink_982dd9c5-b01b-515e-a613-eab57fc365e9)

Nigel Mansellâs life is a wonderful example of the triumph of the human spirit over adversity. He has overcome enormous hurdles throughout his career thanks to an indomitable will, total self-belief and a burning desire to succeed.

All top Grand Prix drivers are heroes, you just have to stand by the side of the track during a race weekend to see that. But Nigel stands out from the crowd for his commitment, his determination and his natural showmanship. His force of will is apparent in everything he does. I once played against him in a soccer match for journalists, photographers and drivers on the eve of the Spanish Grand Prix in 1991, a week after the pit stop fiasco in Portugal, where Nigelâs hopes of beating the great Ayrton Senna to the World Championship had followed his errant rear wheel down the pit lane.

Most of the players were there for fun, either a bit long in the tooth or too fond of their beer to be fully competitive, but Nigel played as if his life depended on it, crashing into every tackle and chasing every ball. His day ended in a twisted ankle, which swelled up like a grapefruit. He won the race that weekend of course. His injury was not play-acting, but a perfect illustration of how accident-prone the man is.

The chronicling of Nigel Mansellâs career has always been uneven. A mismatch of personalities between him and many of my colleagues in the world of journalism has led him in for some heavy criticism, some of it justified, some of it no more than blind insults. I have always been sceptical about the criticism that Nigel has come in for and fascinated to know what really makes him tick. It struck me that, although a huge public feels it can identify with him, there are very few people in the sport who actually understand what he is all about.

Nigel and I spent over 16 months devising, developing and refining this book in order to make it the definitive text on his life and racing career. In these pages Nigel explains for the first time what lies behind his philosophy of life and his psychological approach to the sport he loves. A great deal of archive research was undertaken and over 30 hours of interviews carried out with people close to Nigel. Time after time fascinating revelations from them prompted equally fascinating reflections from Nigel. We have included some of the more revealing comments, where appropriate, as notes at the end of each chapter.

Sifting through all the evidence, I believe that the starting point for understanding Nigel Mansell lies in two comments made by Williamsâ director Patrick Head and Formula 1 promoter Bernie Ecclestone, when interviewed for this book. Bernie, who knows and understands Nigel better than most in the Formula 1 pit lane, said that he is âa very simple, complex personâ while Patrick described Nigel as ânot a driver who takes well to not-winningâ. The veracity of these two statements is there for all to see in Nigelâs own words in this book.

He is a great champion who has not been fully appreciated in his own time and perhaps it will only be in history, provided it is objectively written, that the full achievement of Nigel Mansell will come to be recognised.

I am greatly indebted to Nigelâs many friends and colleagues who gave me information and insights and who pointed me towards the right areas to probe.

I would like to thank Murray Walker, Bernie Ecclestone, Gerald Donaldson, David Price, John Thornburn, Chris Hampshire, Sue Membery, Grant Bovey, Sally Blower, Anthony Marsh, Creighton Brown, Patrick Mackie, Mike Blanchet, Nigel Stroud, Frank Williams, Patrick Head, David Brown, Cesare Fiorio, Carl Haas, Paul Newman, Peter Gibbons, Bill Yeager, Derek Daly, Gerhard Berger, Keke Rosberg and Niki Lauda.

Special thanks to Peter Collins, Peter Windsor and Jim McGee for devoting a lot of time and help with my research, and to Rosanne Mansell for the stories, help with the editing and copious cups of tea. I am also greatly indebted to my father, Bill, and Sheridan Thynne for laboriously studying the draft manuscripts and making helpful suggestions.

Thanks also to the folks at CollinsWillow: Michael, Rachel and Monica and especially to Tom Whiting for an excellent piece of editing; Alberta Testanero at Soho Reprographic in New York; Bruce Jones at Autosport magazine for use of the archive; Andrew Benson for archive material and Rosalind Richards and the Springhead Trust; Ann Bradshaw, Paul Kelly and Andrew Marriott for their support; Pip for keeping me sane; and to my parents Bill and Mary and my sister Sue.

Most of all, I would like to thank Nigel for giving me the opportunity to write this book with him and for opening the door and allowing me in.

James Allen

Holland Park, London

WHY RACE? (#ulink_98f9fc26-593b-52e3-9fd3-8097bdf75622)

My interest in speed came from my mother. She loved to drive fast. In the days before speed limits were introduced on British roads, she would frequently drive us at well over one hundred miles an hour without batting an eyelid. She was a very skilful driver, not at all reckless, although I do recall one time, when I was quite young, she lost control of her car on some snow. She was going too fast and caught a rut, which sent the car spinning down the middle of the road. Although it was a potentially dangerous situation I was not at all scared. I took in what was happening to the car, felt the way it lost grip on the slippery surface and watched my mother fighting the wheel to try to regain control. I was always very close to my mother and I loved riding with her in the car. I was hooked by her passion for speed.

Racing has been my life for almost as long as I can remember. I told myself at a young age that I was going to be a professional racing driver and win the World Championship and nothing ever made me deviate from that belief. There must have been millions of people over the years who thought that they would be Grand Prix drivers and win the World Championship, fewer who even made it into Formula 1 and made people believe that they might do it and fewer still who actually pulled it off.

A lot of things went wrong in the early stages of my career. I quit my job, sold my house and lived off my wife Rosanneâs wages in order to devote myself to racing; but this is a cruel sport with a voracious appetite for money and in 1978, possibly the most disastrous year of my life, Rosanne and I were left destitute, having blown five years worth of savings on a handful of Formula 3 races.

Not having any backing, I often had to make do with old, uncompetitive machinery. I had some massive accidents and was even given the last rites once by a priest whom I told, not unreasonably, to sod off. But we never gave in.

Along the way Rosanne and I were helped by a few people who believed in us and tripped up by many more who didnât. But I came through to win 31 Grands Prix, the Formula 1 World Championship and the PPG IndyCar World Series and scooped up a few records which might not be beaten for many years. For one magical week in September 1993, after I won the IndyCar series, I held both the Formula 1 and IndyCar titles at the same time.

Looking back now, it amazes me how we won through. I didnât have a great deal going for me, beyond the love and support of my wife and the certainty that I had the natural ability necessary to win and the determination not to lose sight of my goal. I did many crazy things that I wouldnât dream of doing now, because I felt so strongly that I was going to be the World Champion.

I have no doubt that without Rosanne I would not be where I am today. She has given me strength when Iâve been down, love when Iâve been desolate and she has shared in all of my successes. She has also given me three lovely children. None of this would have been possible without her.

Over the years there have been many critics. Hopefully they have been silenced. Even if they havenât found it in their hearts to admit that they were wrong when they said I would never make it, perhaps now they know it deep down.

I have always been competitive. I think that it is something you are born with. At around the age of seven I realised that I could take people on, whether it was at cards, Monopoly or competitive sports and win. At the time, it wasnât that I wanted to excel, I just wanted myself, or whatever team I was on, to win. I have always risen to a challenge, whether it be to win a bet with a golfing partner or to come through from behind to win a race. I thrive on the excitement of accepting a challenge; understanding exactly what is expected of me, focusing my mind on my objective, and then just going for it. I have won many Grands Prix like this and quite a few golf bets too.

As a child at school I played all the usual sports, like cricket, soccer and athletics and I always enjoyed competing against teams from other schools. But then another, more thrilling, pursuit began to clamour for my attention.

My introduction to motor sport came from my father. He was involved in the local kart racing scene and when he took me along for the first time at the age of nine, a whole new world of possibilities opened up. It was fast and exhilarating, it required bravery tempered by intelligence, aggression harnessed by strategy. Where before I had enjoyed the speeds my mother took me to as a passenger, now I could be in control. It was just me and the kart against the competition.

To a child, the karts looked like real racing machines. The noise and the smell made a heady cocktail and when you pushed down the accelerator, the vibrations of the engine through the plastic seat made your back tingle and your teeth chatter. It was magical. It became my world. I wanted to know everything about the machines, how they worked and more important how to make them go faster. I wanted to test their limits, to see how far I could push them through a corner before they would slide. I wanted to find new techniques for balancing the brakes and the throttle to gain more speed into corners. I wanted to drive every day, to take on other children in their machines and fight my way past them. I wanted to win.

At first I drove on a dirt track around a local allotment, then I went onto proper kart tracks. The racing bug bit deep. I won hundreds of races and many championships, and as I got more and more embroiled in the international karting scene in the late sixties and early seventies I realised that this sport would be my life. Where before I had imagined choosing a career as a fireman or astronaut, as every young boy did in those days, or becoming an engineer like my father, now I had an almost crystal clear vision of what lay ahead. My competitiveness, determination and aggression had found a focus.

I also used to love going to watch motor races. The first Grand Prix I went to was in 1962 at Aintree when Jim Clark won for Lotus by a staggering 49 seconds ahead of John Surtees in a Lola. I saw Clark race several times before his tragic death in 1968 and I used to particularly enjoy his finesse at the wheel of the Lotus Cortina Saloon cars. He had a beautifully smooth style and was certainly the fastest driver of his time. I can also remember rooting for Jackie Stewart when he was flying the flag for Britain. We went to Silverstone for the 1973 British GP, when the race had to be stopped after one lap because of a pile up on the start line. Iâll never forget watching Jackie in his Tyrrell as he went down the pit straight in the lead and then straight on at Copse Corner. I thought: âThatâs not very goodâ but it turned out that his throttle had stuck open.

Throughout the sixties and seventies as I tried to hoist myself up the greasy pole and move into their world, I followed the fortunes of the Grand Prix drivers. My favourites were James Hunt and Jody Scheckter, while I particularly liked watching Patrick Depailler and Ronnie Peterson, who were both very gutsy, aggressive drivers with a lot of style.

I never saw him race but I had a lot of respect for the legendary fifties star Juan-Manuel Fangio. To win the World Championship five times is a remarkable achievement. I have read about him and met him several times and I only wish I could have seen him race. Iâm told it was a stirring sight.

As I turned from child to adolescent and into adulthood I absorbed myself totally in motor racing, becoming totally wrapped up both in my own karting career and in the wider field of the sport. I am very much aware of the history of Grand Prix racing and I think that nowadays it is a lot more competitive than it was in the days of Fangio or Clark, although Iâm sure that the people competing in those days would dismiss that idea.

People like to compare drivers from different eras and discuss who was the greatest of all time, but the cars were so different that it makes it impossible to say who was the best; you just have to respect the records that each driver set and the history that they made. What I think you can say is that anyone who is capable of winning a World Championship in one sport could probably have done it in another discipline if they had put their minds to it, because they all have something special in them which gives them the will to win.

I had that will to win and I knew all along that, given half a chance, I could make it to the top. Against the wishes of my father, I switched from karts to single-seater racing cars in 1976 and thus began the almost impossible seventeen year journey which took me to the Formula 1 World Championship in 1992 and the IndyCar World Series in 1993. Along the way I suffered more knocks than a boxer, more rejections than an encyclopedia salesman.

In our sport it is often said that truth is stranger than fiction. The most unbelievable things can happen in motor racing, especially Formula 1, and in my case they frequently did. I can laugh now at my childhood vision of a racing driverâs life, it seems hopelessly naive in comparison to the reality.

We began writing my autobiography at possibly the worst time I can remember for trying to explain why I am a racing driver. My rival in many thrilling Grands Prix and a driver whose ability I respected enormously, Ayrton Senna, had just been killed in the 1994 San Marino Grand Prix. It was a crushing blow. The last driver to have perished in a Grand Prix car was my old team-mate Elio de Angelis in 1986, another death which hit me hard. I had seen many drivers get killed during my career, but for some of the younger ones it came as quite a shock to realise how close to death they could come on the track.

It had been twelve years since anyone had died during an actual Grand Prix. There have been huge advances made in safety since those days which certainly helped me to survive some horrific accidents, but when Senna and Roland Ratzenberger were both killed in the same weekend the whole sport was left reeling. There had been many terrible accidents in the preceding twelve years, but the drivers had got away mostly unharmed. Racing had been lucky many times, now its luck had run out.

Every time I thought about it, shivers ran down my spine. It was difficult to comprehend that Ayrton was dead; that he would never be seen again in a racing car. Ayrton was always so committed. Like me, he explored the limits and we had some thrilling no-holds barred battles where both of us drove at ten tenths the whole way. A mistake by either driver in any of those situations would have given the race to the other. It was pure competition.

He won half of his Grands Prix victories by beating me into second place and I won half of mine by beating him. We are in the Guinness Book of Records for sharing the closest finish in Grand Prix racing, at the 1986 Spanish Grand Prix, where he just pipped me by 0.014s as we crossed the finish line; a distance of just 93 centimetres after nearly 200 miles of racing. Some of the battles we had are part of the folklore of racing.

At Hungary in 1989, for example, I seized the opportunity, as we approached a back marker, to slingshot past him and grab a memorable victory. But perhaps the most enduring image of our rivalry was the duel down the long pit straight in the 1991 Spanish Grand Prix. His McLaren-Honda against my Williams-Renault; both of us flat-out on a wet track at over 180mph, with only the width of a cigarette-paper separating us, both totally committed to winning, neither prepared to give an inch. Like me, Ayrton wanted to win and was not a driver who took well to coming second.

Naturally everybody wanted to know what I thought about Ayrtonâs death and whether it would make me retire. I had achieved a great deal, I didnât need the money, I was a forty-year-old married man with three children, why continue to take the risk? The press had a field day, some writing that I was considering retirement, others saying that I was negotiating a return to Formula 1 for some unheard-of sum of money. I have never had such a hard time justifying what I do for a living as I did in the weeks following Ayrtonâs death. Every day I even questioned myself why I was doing it.

It didnât help that this period coincided with preparations for my second Indianapolis 500; a race which I remembered painfully from the year before, when I nearly won despite a severe back injury caused by hitting a wall at 180mph in Phoenix the previous month.

Every journalist and television reporter I spoke to during this period wanted me to articulate my fears about racing and my thoughts on Ayrtonâs death. They were just doing their job, of course, and it was my responsibility as a professional sportsman to talk to them, but it became thoroughly demotivating. If it were not for the fact that I am totally single-minded when it comes to racing, the barrage of questions about death could so easily have taken the edge off my competitive desire.

My passion for racing, undiminished by over thirty years of experience, was the only thing that made me put my helmet on, get into my car and drive flat out.

I am a great believer in fate, something else I inherited from my mother, and this has helped me to come to terms with some of the most difficult times in my life. If things had worked out differently and I had stayed at Williams for another couple of seasons after I won the 1992 World Championship, I would have had a great chance to win again in 1993 ⦠but then the tragedy that befell Ayrton at Imola could have happened to me.

There are three or four drivers in the world who could have been in that particular car that day, but it wasnât Prost, it wasnât Damon Hill and it wasnât me. It was Ayrton. Probably through no fault of his own, one of the greatest racing drivers of all time is dead and it could quite easily have been me. So when people ask me whether I have any regrets I tell them, âYou cannot control destiny and in our business there are occasional stark reminders of that.â As a racing driver you must believe in fate. You wouldnât get back into another car if you didnât.

Over the years I have hurt myself quite badly in racing cars and this will have prompted many a sane person to wonder why I race. Naturally pain is the farthest thing from your mind when you are in a racing car. You have to blank it out completely and focus on the job in hand. This is a quality only the very top racing drivers have. You must be able to forget an injury. Your mind must push your body beyond the pain barrier. I have often found that adrenalin is the best painkiller of all. In a hard race, even if you arenât carrying an injury, your mind pushes your body beyond the point of physical exhaustion to achieve the desired result, which is winning.

When the race is over your brain realises that your body is exhausted and canât move and then you are reminded of the pain. I have been so drained after some races that I have been unable to get out of the car. But my ability to blank out pain has been invaluable throughout my career; indeed I doubt whether I would ever have made it had I not had that ability. I won my first single-seater championship in my first full year despite suffering a broken neck mid-season. I got my big break into Formula 1 in 1979 with a test for Lotus on one of the worldâs fastest Grand Prix circuits, Paul Ricard in France, and managed to get the job despite having a broken back at the time.

I even won the 1992 World Championship with a broken foot, which I sustained in the last race of 1991. An operation over that winter would have meant it being in plaster for three months. However, I was determined to get into perfect physical shape and to put in a lot of testing miles in the car to be ready for the following season. So I delayed the operation. I couldnât tell anyone because if the governing body found out they might have stopped me from racing.

The orthopaedic surgeons thought I was crazy. The foot was badly deformed and after every race that year I could barely walk. Some journalists chose to interpret my limp as play-acting which, in retrospect, is pretty laughable. But then what do they know? None of them have ever driven a modern Grand Prix car flat out for two hours.

If they had they would know that the cockpit is a very hostile environment. The body receives a terrible pummelling during the course of a race from the thousands of shocks which travel up through the steering wheel, the footrest and the seat as you fly along the ground at 200mph. Through the corners the g-forces try to snap your head off. When you brake your insides are thrown forwards with violence, your body gripped by a six-point harness, which pins you into your seat. When you accelerate your head is thrown back violently against the carbon fibre wall at the back of the cockpit, which is the only thing separating you from a 200 litre bag of fuel. On top of that, the cockpit is hotter than a sauna and you are wearing thick fireproof overalls and underwear. The only thing which is in any way designed for comfort is the seat, which is moulded to the driverâs body.

If you have a good car and everything is right, you become at one with the car and it allows you to express yourself. It responds to your commands, goes where you point it and allows you to explore the limits with confidence. You can get into a straight fight with another driver, both pushing your machines to the limits, both determined to win. On days like that, driving a Formula 1 car is magical, another world. The pure essence of competition.

Other days you have to fight the car all the way. You might realise early in a race that your car is not handling properly but you have to try to drive around the problem. The car might catch you out or do something you donât expect, and this destroys your confidence in it. Everything becomes a struggle, but you fight to stay in the race with your competitors. You must do everything you can to remain competitive. Driving a Grand Prix car hard is always exhausting, but you must not let up or give in to pain until you reach the end. As Ayrton once said, âAll top Grand Prix drivers are fast, but only a very few of us are always fast.â

I often wonder what life would have been like had I chosen a less dangerous sport. I play golf to quite a high amateur standard and Iâm pretty sure that if I had poured the same dedication and focus into it thirty years ago that I poured into racing, I could have made my living from it. Whether I could have reached the same level and got the same rewards, Iâm not sure and I will never know. But I think in many ways if I had my time again I would like to find out.

It may sound improbable, but I have had days on the golf course where I have scored back-to-back eagles, or had a round of 65 including half a dozen birdies, and these have been some of the biggest thrills Iâve ever experienced. I love the idea that itâs just you and a set of clubs against the golf course and the elements. Itâs a true test and if you get it right the sense of gratification is quite overwhelming. And if, by chance, it all goes wrong and you slice your ball into the trees, you donât hurt yourself. You just swallow your pride, grab a club and march in after it.

Having said that, Iâm glad that motor racing has been my life. It has satisfied my desire to compete and, above all, to win. It has tested my limits and my resolve many times. It has bankrupted me, hospitalised me and some of the disappointments it has inflicted on me have almost broken my heart. It has also robbed me of some good friends.

But all of that is far outweighed by what it has given me. I have had two lifetimes worth of incredible experiences and more memories than if I were a hundred years old. I set out on this long and treacherous journey with nothing, except the belief that I had the talent to beat the best racing drivers in the world.

After a lot of hard work I was able to prove it.

PART ONE (#ulink_de1c1f50-fe19-5785-9fd6-6239230fe08e)

THE SECRET OF SUCCESS (#ulink_de1c1f50-fe19-5785-9fd6-6239230fe08e)

âI am interested only in success and winning races and if my brain and body did not allow me to be completely committed, I would know that I was wasting my time. The moment I feel that, I will retire on the spot.â

1 (#ulink_3c292549-41b7-5376-857d-81c57dc4df31)

MY PHILOSOPHY OF RACING (#ulink_3c292549-41b7-5376-857d-81c57dc4df31)

There are very few people who have any idea what it takes to be successful in this business.

Much of my life has been devoted to the pursuit of the Formula 1 World Championship. I was runner-up three times before I finished the job off in 1992. Yet if circumstances had been different and politics hadnât intervened, I might also have won a further two World Championships, in 1988 with Williams and in 1990 with Ferrari.

In both cases the essentials were there. The hard work developing the car had been done, but politics dictated that the pendulum should swing away from me. In 1988 Honda quit Williams and dominated the championship with McLaren, while in 1990 Alain Prost joined Ferrari, where we had developed a winning car, and proceeded to work behind the scenes to shift all the teamâs support, which I had worked for in 1989, to himself.

Although I consider myself strong in most sporting areas of motor racing, I am a poor politician and there is no doubt that this has accounted for me not winning more races and more championships.

Moreover, these experiences provide an object lesson in just how difficult it is to win a lot of Grands Prix and a World Championship; there is far more to it than simply beating people on the race-track. They also serve as a reminder that nothing in motor racing is ever certain. You might have all the right ingredients in place, the full support of the team, an excellent car, and yet some minor component can let you down or some freak accident, like a wheel nut coming off, can rob you of the prize after youâve done most of the hard work.

There are no shortcuts to winning the World Championship, but in my fifteen years as a Grand Prix driver I have learned a lot about what it takes to win consistently.

My philosophy of driving a racing car is part and parcel of my philosophy of life. Achievement, success and getting the job done in every area of life, not just in the cockpit, are fundamental to my way of thinking. Everything has to be right. Whether itâs getting to the golf club on time or having the right pasta to eat before a race, the demand for perfection everywhere is critical.

MOTIVATION IS THE KEY

Winning at the highest level of motor sport is not like winning in athletics or tennis or golf. In those sports you have just yourself to motivate. In motor sport, you require a huge team and huge resources and it is incredibly difficult to get it all to gel at the same time, to hit the sweet spot. Everything has to come together in unison.

When people think of Nigel Mansell the World Champion, they think that all my winning is done behind the steering wheel. Although important, the actual driving aspect is the final link in the chain. A lot of what it takes to be a champion takes place out of the car, unseen by the public. Winning World Championships as opposed to winning the odd Grand Prix is about always demanding more from your team and never being satisfied. This was a very important aspect of the 1992 World Championship and it is perhaps an area that the public understand least.

At Paul Ricard in September 1990 I tested the fairly unloved Williams-Renault FW13B. I changed everything on the car and got it going quicker than either Riccardo Patrese or Thierry Boutsen had managed that year, but it was clear to me that although Renault and the fuel company Elf had been doing a reasonable job, they had not been pushed hard enough to deliver the best. I immediately began demanding more from them, especially Elf. Having been at Ferrari for the past two years, I understood the progress which their fuel company Agip had made. Agip was producing a special fuel which gave Ferrari a significant horsepower advantage. I am a plain speaking man and I told them straight. The demands I made on them didnât endear me to them initially; in fact I pushed so hard that I was told at one point to back off. But I knew that if Williams-Renault and I were going to win the World Championship, we had to begin immediately raising the standards in key areas like fuel.

As I said, it didnât endear me to them to start with. No-one likes to be told that they can do a lot better, even less that they are well behind their rivals. Perhaps they thought that I was complaining for the sake of it, or âwhingeingâ. I think whingeing is a rather naive term to use for trying to raise everybody up to World Championship level!

Eventually they came around to my way of thinking. In the case of Elf, it took them three or four months to realise that I meant business and another three to deliver the fuel that I wanted, but the performance benefits that began to emerge in the late spring of 1991 were the result of the pressure that I had put on both Renault and Elf in late 1990.

Ayrton Senna opened up a points cushion in the World Championship by winning the first four races of 1991 in the McLaren-Honda, but after that we were able to compete on more equal terms and as the year wore on and the developments came through onto the cars, the wins started to come thick and fast. From then on everybody kept the momentum going, always striving to do a better job than they thought was possible and the result was the total domination of the 1992 Championship. It took a year and a half to get the team into championship winning mode but together we did it.

Motivation is a vital area of a driverâs skill. Towards the end of 1990 I visited the Williams factory in Didcot to meet the staff. Since I had left at the end of the 1988 season, the team had grown and new staff had been taken on. Consequently there were quite a few people there who didnât know me and who did not know how I work. I asked for everybody to come to the Williams museum where I did a presentation on what I thought it would take to win the World Championship. I needed them all to know that it isnât just a driver and a team owner who win World Championships, but the 200 or so people back at base, some of whom only give up the odd Saturday or Sunday to come in to work and do what is required to win, but who are all very important.

Similarly, in February 1992, around a month before the start of the season, I went to Paris with the then Williams commercial director, Sheridan Thynne to visit the Renault factory at Viry Chatillon. We went around the whole place, not just the workshops where they prepare the engines, but every office and every drawing office in the building. We shook hands with every single person from the managing director down to the secretaries and the cleaners and signed posters for each of them.

It was a good visit from a motivational point of view. It got everybody focused on what we were about to do and it helped all the Renault people to understand me a bit better and to feel a part of the success. We were taken around and introduced to everybody by my engineer, Denis Chevrier. I subsequently found out that he had been on a skiing holiday that week and wasnât due back until the weekend. But so committed was he to the cause of winning the World title, that he had cut short his holiday to be there. That is the stuff of which championships are made.

We also visited Elfâs headquarters and met with all of their people. I believe that this is a key part of building a successful team. You must push everybody involved with the team in every area and tell them that, although they are doing a good job, they can do better. A large part of it is demanding the best, better than people think they can achieve. From suppliers of components through to secretaries in the factory, everyone must be made to feel they can improve and to feel a part of the success when it comes. When I step from the car after winning a race or getting pole position, I shake hands with all my mechanics and congratulate them on the job that we have all done together.

Over the years, through sheer determination to succeed, I have learned all of the things that are required to win. I try to raise everybodyâs standards to a level that they donât always know they can achieve. I demand the highest standards from everyone around me and if everything is working right, then I just have to keep up my end of the deal on the track. If itâs not going right and everybody is searching for answers it puts more pressure on the driver and makes it more difficult to get good race results.

I have also learned that you cannot please everybody and that no matter what you do or say and no matter how you carry yourself when you are in the spotlight, people are going to criticise you. Sadly that is a given element of my life and I have come in for a lot of criticism, some of it justified, most of it, I believe, not.

If pushing everybody to produce commitment at the highest level in order to win really is whingeing, then Iâm a whinger â but I have the satisfaction of knowing that it leads directly to success.

There is a deplorable and negative characteristic of the British, which is to try to undermine success and to glorify the gallant loser. It is often called the âtall poppy syndromeâ. The media have a simplistic perception of a lot of stars; they like to stick a label on someone and work from there. Once the label is stuck on it is difficult to shake off. People are actually a lot more complicated than that and in most cases there is a great deal going on behind the scenes, which would explain a lot if only it were more widely known.

In 1992 I was criticised for implying that the victories we were accumulating were entirely due to me and not to the team and our fabulous car, FW14B. I always paid tribute to the team in post race press conferences, itâs just that the media chose not to use those quotes in their articles. I did a long interview with the BBC at the end of the year, where I spent quite some time going into detail about how the team had done a great job, but they cut that part out when they aired the programme.

The way I work is that I am the captain of the ship and I work for the common good within a team. I donât like anyone telling me how to drive a racing car or what to do out on the track â thatâs my business and my record speaks for itself. Outside the car I listen to all of the technical advice and make use of all the expertise available. I am a team player and I know that unless some outside factor comes in to upset the balance, whatâs best for me is whatâs best for the team.

When you hire Nigel Mansell as your driver, the actual time spent in the car and what I can do with the car is far from all that you are buying. The ability to get the best out of the the car is well known, but also crucial is the ability to get the car into a shape to be used like that.

I need to be surrounded in a team by people who believe in me and who know that if I am given the right equipment, Iâll get the results.

When I aligned myself to Williams in 1991/92, everybody worked my way and we delivered the goods: nine wins, fourteen pole positions and the title wrapped up in record time by August. If we hadnât delivered the goods then I could sympathise with the teamâs frustration and difficulty in continuing the relationship. But to change tack just because of pressure from the teamâs French partners to bring aboard one of their fellow countrymen, Alain Prost frustrated me enormously, although I could understand the reason behind it.

There is an old Groucho Marx joke which goes: âI wouldnât want to be a member of a club which would have someone like me as a member.â I am the exact opposite of this. I only want to be in a team that wants me there and wants to work the best way both for the team and for me. If I feel that I do not have the teamâs full support, then I am quite prepared to leave.

I donât want to be in a situation where everyone is not pulling together.

BE FAST AND CONSISTENT

Patrick Head, Williamsâ technical director, has said that one of my major strengths as a racing driver is that I donât have on days and off days. I am consistently fast, which is a big help to a team when it comes to developing a car. They know that the speed at which I drive a car on any given day is the fastest that car will go, so they always have something consistent to measure against.

Of course, in reality, every human being has on days and off days, but if you are a real professional it shouldnât show in the car, because you are being paid to drive the car and to perform. Also your professional integrity should not allow you to take it easy on yourself when you feel like it. A champion needs to have that extra will and determination to get the job done so that, although you might not feel on top form out of the car, you perform to the highest levels in it. That takes a lot of energy but it is vital if you are going to be successful.

Sometimes you have to face the fact that even your best efforts are not going to yield the results. In my second year of IndyCars in 1994, it just wasnât possible to do what we had done the year before and win races consistently with the car we had. I gave it a massive effort in bursts during qualifying and sometimes was able to get on pole or the front row, but the Penskes were so superior over a race distance that there was nothing I could do to beat them, even if I drove every lap of the race as if it were a qualifying lap. When itâs not possible you canât make it happen. Thatâs not to say that I gave up or resigned myself to making the numbers up. I was just being realistic.

I am often asked how I feel I have improved as a driver over the years. Obviously you cultivate your skills and talents in all areas, but if I had to be specific I would say that I have improved as a human being and that has matured my racing technique. Iâm a little bit more patient now and Iâm not as aggressive as I used to be, although there is still a lot of aggression there. I have much more knowledge of how to get the job done and I donât pressure myself into doing a certain lap time, which I used to do all the time.

I am a better thinker in a racing car nowadays, I donât feel that I have to lead every lap of a race. As long as Iâm the one who crosses the line first thatâs the important thing.

I have also developed the courage to come into the pits when the car isnât working and to tell the crew that itâs terrible, rather than feel that I have to tread on eggshells so as not to hurt their feelings. In the early days, when I complained about a car everybody would say, âOh, heâs whingeing again, heâs no good.â Now I have the self belief and I know what is right and what is wrong and stick to it. I donât just steam in and criticise, I make suggestions and pressurise people into accepting that something isnât good enough and needs to be changed. In other words I have become a little wiser about how to operate and do things.

MY UNUSUAL DRIVING STYLE

My driving style has changed little over the years that I have been racing. It is quite a distinctive style, because I tend to take a different line around corners from other drivers. The classic cornering technique, as taught by racing schools, is to brake and downshift smoothly while still travelling in a straight line and then to turn into the apex of the corner and apply the power. Thus you are slow into the corner and fast out of it.

I never consciously set out to ignore those rules, I just devised my own way of driving and stuck to it because I found it faster. It is a lot more physical and tiring than the classic style, but itâs faster and thatâs what counts.

My style is to brake hard and late and to turn in very early to the apex of the corner, carrying a lot of speed with me. I then slow the car down again in the corner and drive out of it. Because I go for the early apex, I probably use less road than many other drivers. In fact if you put a dripping paint pot on the back of my car and on the back of another driverâs car around a lap of a circuit like Monaco, you would probably find that my lap is 20 or 30 metres shorter than theirs!

To drive like this I need a car which has a very responsive front end and turns in immediately and doesnât slide at the front. I cannot drive on the limit in a car which understeers, for example. My cars tend to handle nervously because I need them to roll and be supple; a car which does this at high speed is an uncomfortable car to drive and is very demanding, but invariably it is faster. Because itâs ânervousâ it will react quickly to the steering and will turn quicker into a corner. The back end feels like it wants to come around on you, but thatâs something you learn to live with. Although itâs nervous itâs got to be balanced properly, if it isnât then thereâs nothing you can do with it. A stable stiff car is reassuring to drive and wonât do anything nasty to you, but itâs not fast. If you want the ultimate then youâve got to have something which is close to the limit. This makes demands on you physically, of course. Itâs much more tiring to drive a car this way and you need to have a particularly strong upper body and biceps in order to pick the car up by the scruff of the neck and hurl it around a corner.

The best car is not just a car which wins for you, but one which gives you the feedback that you need as a driver so you can have total confidence in it. The best car I ever drove was the active suspension Williams-Renault FW14B, in which we won the 1992 World Championship. It was a brilliant car because the only limiting factor was you, the driver. The car could do anything you wanted it to. For example, if you wanted to go into a particular corner faster than you had ever done before, all that was holding you back was the mental barrier of being able to keep your foot down. If you went for it, the car would see you through. I loved that.

SLOWING THINGS DOWN

Any top class racing driver must have the ability to suspend time by the coordination of eyes and brain. In other words, when youâre doing 200mph you see everything as a normal person would at 50mph. Your eyes and brain slow everything down to give you more time to act, to make judgments and decisions. In real time you have a split second to make a decision, but to the racing driver it seems a lot longer. If youâre really driving well and you feel at one with the car, you can sometimes even slow it down a bit more so it looks like 30mph would to the normal driver. This gives you all the time in the world to do what you have to do: read the dashboard instruments, check your mirrors, even radio your crew in the pits. Thatâs why, when I say after I won the British Grand Prix, for example, that I could see the expressions on the faces of the crowd, itâs because everything was slowed and I had time to see such things.

When you first drive a Grand Prix car, everything happens so quickly that you can sometimes frighten yourself. Once youâve had some experience of racing at these speeds you can get into pretty much any racing car and go quickly, provided that youâre comfortable with the car of course. The more time you spend in the car the more in tune you become with the speeds involved.

Sometimes unexpected things happen incredibly quickly and you just have to rely on instincts to see you through. A good example of this is the incident which occurred when I was with Ferrari at Imola in 1990, when Gerhard Berger in the McLaren pushed me onto the grass at the Villeneuve Curve. That was an incredible moment. It was a split second decision as I travelled backwards at nearly 200mph whether to put it into a spin or whether to try and catch it. I took the first option and managed to bring the nose around the right way and kept on going. Although I cannot say that I saw the direction I was pointing throughout the two full revolutions the car made, I was aware through instincts of exactly where I was going the whole time. The result was a spectacular looking double spin and I kept on going. I probably only lost about 40mph in the spin. Because the adrenalin was pumping so hard after it, I broke the lap record on the next lap.

At times like that youâve got to be a bit careful. Your heartbeat gets up to 150-200 beats per minute. You donât think about it, but it is very important that you breathe properly, because you are on the verge of hyperventilating at that pulse level. It is vital that you understand your body and that you manage it as much as you do the car.

DRIVING ON THE LIMIT

Everybody has different limits, thatâs one of the things which differentiates good amateur drivers from great professional drivers. Most top Grand Prix drivers will go beyond their limits at some time in their career and a few really top ones are able to go beyond their limit, if the occasion demands, for a period of time. Ayrton Senna talked after qualifying at Monaco in 1988 of going into a sort of trance, where he was lapping beyond his limit, treading into unknown territory. He stopped after three laps because he frightened himself. While I would not describe the feeling as being like a trance, I have had a similar experience several times, most notably at Silverstone in 1987, when I caught and passed Nelson Piquet after 29 laps of totally committed driving. This experience of mesmerising speed is described in detail later in the book. More usually that feeling comes when you commit every ounce of your strength and determination on a qualifying lap.

When you go for the big one in qualifying, you give it everything youâve got and on certain corners you over-commit. Now this is where the judgment comes in because if you over-commit too much then you wonât come out of the corner the other side. You enter the corner at a higher speed than on previous occasions and if you are able to carry that speed through the corner you will exit quicker than before. You canât do it consistently because the car wonât allow it and something will inevitably give. Of course you have to feel comfortable with the car. If itâs bucking around all over the place and is unstable even at medium speed through a corner then you would be a fool to go in 20mph faster next time round.

Provided that the car is doing more or less what you want it to, you can hustle it around on one or two really quick laps. It then comes down to your own level of commitment and that depends on so many factors. Some drivers become less committed after they have children, others lose the edge after a major accident, others will become more committed when itâs time to sign a new contract for next year!

Mental discipline plays a huge part in driving on the limit. A top athlete in any sport must be able to close his mind completely to extraneous thoughts and niggling doubts and concentrate 100%. If you want to be a champion, you need to be able to focus completely on the job in hand to the exclusion of everything else going on around you. Your brain must have a switch in it so that the minute you need to concentrate, your mind is right there and ready to go. I have been able throughout my career to give a consistently high level of commitment and even my harshest critics would admit that there are few more committed or focused drivers than me.

Itâs a personal thing. You have to be true to yourself and if I thought that I had lost my edge I would stop racing immediately. I am interested only in success and winning races and if my brain and body did not allow me to be completely committed I would know that I was wasting my time. The moment I feel that, I will retire on the spot.

You can only do what your brain and your body will allow you to do. For example, in qualifying for the British Grand Prix in 1992, the telemetry showed that I was taking Copse Corner 25mph faster than my team-mate Riccardo Patrese, using the same Williams-Renault FW14B. In fact over a whole lap I was almost two seconds faster than him. As we sat debriefing after the session, Riccardo looked at the printouts and said that he could see how I was taking Copse at that speed, but that he couldnât bring himself to do it. His brain was telling his body, âIf we go in that fast, weâll never come out the other side.â

Every really hot qualifying lap relies on the brain and body being in harmony and prepared, at certain key points, to push the envelope, to over-extend. That is the only way you are going to beat the Rosbergs, Piquets, Sennas and Schumachers of this world. It goes without saying that once you operate at that level, your self-belief must be absolute.

In all my career I have done maybe 10 perfect laps. One of the ones I savour the most was at Monaco in 1987. To do any kind of perfect lap is special, but when you do it at Monaco thatâs as good as it gets. When you run the film of the lap through your mind afterwards and you examine every gearchange, every braking point, every turn-in and how you took every corner and at the end of it you say âI could not have done that fasterâ, thatâs when you know you have done a perfect lap. You donât need to go out and try to do better. When you get a lap like that you donât even need to look at the stopwatch on your dashboard or read the pit boards. You know itâs quick.

When I came back into the pits David Brown, my engineer and a man who would become one of my closest allies in racing, pointed out that the white Goodyear logos had been rubbed off the walls of the rear tyres where I had brushed the barriers! You have to skim the barriers at a couple of points when youâre flying at Monaco, itâs the only way to be really quick. It sounds frightening, but itâs supremely exhilarating. I never feel more alive on any race track than I do on the streets of Monaco. Everything has to be synchronised and you need to have fantastic rhythm as well as aggression and a truckload of commitment to be fast there. I have always enjoyed the challenge, but I think also that the romantic in me responds to the idea of going well at this most celebrated of Grands Prix.

Generally speaking, although qualifying is important, merely lapping quickly, in other words driving fast, is not what turns me on the most. Competition is the most important thing and driving flat out against someone else with victory as the end result is my idea of heaven. Nevertheless, when you get a perfect lap in qualifying it feels absolutely marvellous. When I got out of the car at Monaco and looked at the white smears on the walls of the tyres where the manufacturerâs logo had been wiped off, it even impressed me. There are no long straights at Monaco, itâs all short chutes, but coming out of the tunnel I was clocked at 196mph, a full 17mph faster than Prost in the McLaren. I was six tenths faster than Senna and 1.7s faster than my team-mate Nelson Piquet and I had done not just one, but three laps which were good enough for pole!

From the point of view of a race, itâs not a major psychological advantage over your rival to get pole position. Anybody can get pole position if they have an exceptional lap in the right equipment. The key is to prove that you have the ability to do it time and again. Itâs not one thing that gets you pole position, itâs a package of things, but you do have to put together the perfect lap and to show that you can do it more than anyone else. I am very competitive and I approach qualifying and racing at the same level.

Some top drivers believe that the race is the most important thing and that their position on the grid does not matter too much. Double IndyCar champion Al Unser Jr is like this, as to some extent was Alain Prost. They would concentrate on getting the set-up of the car absolutely perfect for the race and not over-extend themselves in qualifying. On one level you can see their point and I have done that a couple of times myself, notably at Hungary in 1989. It is the race after all which carries the points, but I have always believed that it is important to be quick and to show that you are strong throughout the weekend. Of course on certain tracks, like Monaco, there is a benefit to being at the front because it is hard to pass in the race.

Sometimes, as happened to me a great deal in the early part of my career, if your car is not up to scratch you are forced to make up the difference yourself. You do not want to be blown off in a bigger way than you have to be. So you delve deep into your reserves of commitment. You have to squeeze the maximum out of your car and out of yourself and whatever that yields is the absolute fastest that it is possible to go with the equipment. You can then go away satisfied in the knowledge that youâve done the best job you can possibly do. Hopefully, if you are working your way up the ladder despite struggling with inferior equipment, the people who run the top teams will pay attention to you and maybe give you an opportunity in a good car.

It is also very important to be on the limit when testing a car because if you donât know what a car is going to do when you are on the limit, then youâll be in trouble when you race it. Anyone can drive at nine-tenths all day, but unless you understand what the car will do at ten-tenths and even occasionally eleven-tenths, then you are not being true to yourself, your car or your team.

When you are testing a car and you are not on the limit, you can make a change which might feel better to you, but which does not show on the stopwatch. If you then say, âNo, it feels better like that, itâs only slow because I wasnât pushing it,â then you might subsequently find that the car wonât work on the limit and in fact youâve made it go slower by making the change. If you find that out during a race, youâre in big trouble.

Sometimes making a car feel better doesnât make it quicker, and the name of the game in motor racing is to shave as many fractions of seconds off your lap time as possible and then to be able to lap consistently at your optimum speed. Itâs an uncomfortable truth for some, but the only thing that tells you that is the stopwatch.

Motor racing is in general, I think, the art of balancing risk against the instinct of self-preservation, while keeping everything under control. People can only aspire to great endeavours if they believe in their hearts that they can achieve their goals â and to my mind thatâs the difference between courage and stupidity.

Courage is calculating risks; when someone sets an objective, realises how dangerous it is, but then does it anyway, fully in control. They have to fight with their feelings and hopefully are honest with themselves when facing up to the dangers inherent in what they are doing. Then there are others who arenât really in control.

STARTING A RACE

The start of a Grand Prix is a very dramatic moment and there is a lot of chaos and confusion going on around you. But the most important thing you have to think about is your own start and making sure that you get away as well as you can. The first couple of corners in a Grand Prix can make a huge difference to the result. If you have pole position and you get a good clean start, you can open out a lead over the field, because they are jockeying for position behind you. Also it goes without saying that if itâs wet and the cars are kicking up huge plumes of spray, there is only one place to be!

Itâs very important at the start to have mental profiles of each of the drivers around you, to know whoâs fired up that weekend and whoâs depressed, whoâs trying to be a hero and who is desperate for a result. If thereâs someone who has qualified way beyond expectations, then they will probably want to show that their position is justified so they are probably going to be dangerous. You need to know who is brainless, who is a cautious starter, and so on. You have to put all of this into your brain and let your instinct take you through. Itâs like reading the greens on a golf course, or knowing about the going on a race course. Itâs the finer points that matter.

Psychologically, the start is vital. In 1992 I had 14 pole positions and at the starts I went off like a rocket. I wasnât holding anything back. I would open out as big a gap as I could as fast as I could. Sometimes I was two or three seconds clear at the end of the first lap. It was vital to dominate everybody, to intimidate everyone to the point where they knew who was going to win before the race even started. And it worked.

I was on a mission that year. No-one was going to beat me. I had psyched myself up throughout the winter and I was incensed when before the season started Patrick Head said when referring to the Williams drivers, âWeâll see who comes out better in 1992.â

That was an insult. My team-mate Riccardo Patrese was a great driver, but my credentials up to that point were a lot better and I had won three or four times as many races as him. Whatâs more, having spent years as the number two driver, I was finally number one. I was determined to crush everybody. I had to dominate the Williams team and I wanted everybody to know that I was number one. I also wanted Ayrton Senna, the only person whom I perceived as being a threat, to know that I was going to win the World Championship at the earliest possible time. The relentless pressure I applied through qualifying and then at the start helped to cement that idea in peopleâs minds.

Sometimes it can all go wrong at the start, as it did in Canada in 1982 when Didier Pironi stalled on the front row of the grid and Riccardo Paletti didnât see him, hit him and was killed. I was one of the cars who had to dodge Pironi and there was no time to think about it, you just had to act. Itâs the instinct of self-preservation. We all have this instinct because we donât want to die. You know when you race a car that if you donât do the right things at certain times, you could get killed or badly hurt. The start of a race is one of those times.

STRATEGY AND READING THE RACE

Peter Collins played a major role in helping me reach Formula 1 and he was my team manager for a few years at Lotus and Williams. I always used to laugh at him because he used to like to plan the race in minute detail beforehand and sometimes we would have ten different strategies in front of us. It was complete nonsense because usually something would happen that we hadnât even considered. Before the start we used to study the grid and he would say, âWhat happens if he gets a good start and what if he gets a bad one?â But whatever you tried to plan, it all used to change.

Niki Lauda was always a great planner, but what he thought about never occurred either, so he gave up wasting his brain power, relaxed and was ready for anything that came up.

Thatâs one of the strengths of my driving now. I donât think about things too much. Iâve had so much experience and so many things programmed into my brain that Iâm prepared for anything. When something crops up, you donât have time to think about it anyway. If you try to think, youâll be too slow in reacting. A mixture of instinct and experience tells your hands and your feet to position the car so that if something does happen, youâre in good shape. It takes years of experience to develop that ability. It just doesnât occur by chance.

Once you are in the race, you can read whatâs going on pretty well. You can control the race more in Formula 1 than you can in IndyCar racing. In IndyCar you rely on the team manager and the crew to call fuel strategies and the yellow flags can wreak havoc to your progress. You can win or lose a race because of yellow flags and thatâs according to the rules. Itâs a bit frustrating, but they are there for everybody, the fans and the television and the smaller teams. It can work for you and it can work against you. Does it level out? Iâm not sure. I think I had a fair bit of luck in 1993, while in 1994 I had some bad breaks, but Iâm happy that it worked out for me first time around.

Formula 1 is quite different. You win and lose a race out on the track. Itâs a pure sprint and itâs very rare that a yellow flag or a pace car will intervene to deprive you of a win which you thought you had in the bag. You rely on pit signals and the radio link with the crew, but you can tell a lot from the cockpit about where the opposition is on the track.

OVERTAKING AND RACE CRAFT

The secret with overtaking is that youâve got to be in total control of what you are doing before you set about passing other cars. If you are on the ragged edge just to keep your car at racing speed, then you are not going to be effective when trying to make up positions and compete with rivals. Some duels can last a long time and you need to be totally comfortable with your car before you can commit the mental and physical energy required to pass a Senna or a Prost on a race track.

When you come to pass someone, you first have to make sure that they know youâre there. Sometimes they do, but will pretend that they donât and will try to block you or even put you off the track. Itâs up to you to decide when and where to engage them in psychological combat.

You first put the âsucker moveâ on them, showing them your nose and setting them up with moves through certain corners to make them think that this is where you are going to attack. You are saying to them, âThis is the move which is going to come off,â when in reality you know that it isnât. You feint to one side and they think that this is your last-ditch attempt to come through, but it isnât. Youâve got something else in mind.

You save up your best move and donât give them any idea what it is or where it will come. Sometimes you only get one chance and winning a race depends on one proper effort. If it comes off you win, if it doesnât you lose. But to have many attempts and to fail all the time, merely weakens your position. You must show that you intend to come through and in many cases you can psyche your opponent out before the fight begins. Some will say, âOh God, itâs Mansell, I canât possibly keep him behind me,â because theyâve had experience of being beaten in the past. This does not work on the real aces however. Youâve got to do something special to pass them and youâll probably only get one go.

This is one of the strongest areas of my driving and I havenât had too much trouble in my career passing people, with one exception. Ayrton Senna stood out during my career as the toughest opponent. Our careers coincided and between 1985 and 1992 we both wanted to win the same Grands Prix. When we both had competitive equipment we knew that to win we would have to beat the other.

We had some fantastic scraps, although in the early days he was quite dangerous to race against. He was so determined to win that he would sometimes put both you and himself into a very dangerous situation. It was a shame he did this. He was so good he didnât need to do it, but he so badly wanted to win.

Sometimes you over-estimate your opponent and this can have dire consequences. For example you might be lapping a back marker, thinking that he will react a certain way, the way you would react if you were in his shoes. If he reacts in a quite different way he might collide with you and then youâve thrown away the race because you attributed a higher level of intelligence to a driver than he actually possesses. It is a far greater weakness, however, to under-estimate an opponent, for obvious reasons.

There is no doubt that at the pinnacle of the sport there are some very forceful competitors.

Mike Blanchet, a former competitor of Nigelâs in Formula 3 and now a senior manager at Lola Cars: âNigel likes a car with a good turn-in. He likes a more nervous handling car, which would frighten most drivers. Most of them like a neutral car with a little understeer, which feels safer. Because of his reflexes and his physical upper body strength Nigel is able to carry a lot of speed into corners without losing control of the car. A lot of people would spin if they tried to take that much speed into a corner.â

Peter Windsor, a former Grand Prix editor of Autocar magazine and Nigelâs team manager at Williams in 1991/92: âNigel drives a little like Stirling Moss used to. Moss always said, âAnyone can drive from the apex of a corner to the exit, itâs how you get into the apex that matters.â Nigel got a feel early on for turning in on the brakes, crushing the sidewall of the tyre and thereby getting more out of a tyre. From the outside he makes a car look superb and his technique is very exciting to watch. He gets on the power very early on the exit of the corner. If the track conditions change suddenly or unexpectedly then Nigel is more at risk than other drivers because heâs more committed early on and more blind than others.â

Derek Daly, driver, turned TV commentator: âMansellâs style is an aggressive style more than an efficient one, but itâs very fast. He makes an early turn-in; he gets his business sorted out in the apex and gets out of the corner as soon as possible. The key to being quick is the time it takes from turning in to reaching the apex and then the momentum you carry through the apex and out the other side. That is an area of the track where a lot of people slow down too much. Mansell doesnât do that. He goes to the apex as soon possible, carrying lots of speed, lots of momentum and gets on his way. It is an unusual style â he often uses different lines through corners, but always the same cornering principle.â

2 (#ulink_30914796-94ee-5a3a-9c5a-bdedf47339a5)

THE BEST OF RIVALS (#ulink_30914796-94ee-5a3a-9c5a-bdedf47339a5)

When I first started in Grand Prix racing there were many top names involved, each of which will always strike a particular chord in the hearts of Formula 1 fans around the world: Niki Lauda, Jody Scheckter, Gilles Villeneuve, Didier Pironi, Nelson Piquet, Patrick Tambay, Alan Jones, Carlos Reutemann, Alain Prost, Elio de Angelis, Jacques Laffite, Keke Rosberg, to name but a few. A lot of those drivers were either World Champions at the time or became champions in the next few years. Thirteen of them had won Grands Prix. I was lucky to enter Formula 1 at a time when there were far more significant names around than there are today.

In the late eighties there were only four âacesâ â Ayrton Senna, Alain Prost, Nelson Piquet and myself. Into the nineties and by the end of the 1994 season, Prost had joined Piquet in retirement and Senna had tragically died, so it was down to three: myself and the emerging talents of Damon Hill and Michael Schumacher. The new breed of drivers have not been able to establish themselves yet, either in the record books or the publicâs perception, and their reputations remain unproven.

The biggest thing for a driver is to gain worldwide recognition and respect and you only get that by doing the job for a number of years and getting the results. You need years of wins and strong placings to establish your name. No disrespect to any Grand Prix driver, but until you have won five and then ten and then fifteen and then twenty Grands Prix, you cannot be considered an ace.

Only three drivers have won more than thirty Grands Prix: Prost, Senna and myself. If you go down the list of prolific Grand Prix winners, many have either retired or died â Jackie Stewart, Niki Lauda, Jim Clark, Stirling Moss, Graham Hill, Juan Manuel Fangio, and so on. One reason for the gulf between the big names and the rest is that in the late eighties, when much more non-specialised media became interested in Formula 1, they could only focus on a limited number of drivers and so instead of looking at seven or eight drivers, they focused only on three and put them under the microscope. Because Prost, Senna and I were winning everything, the non-specialist media totally disregarded some other good up and coming drivers.

When I decided to commit myself to motor sport and to strive to be World Champion, I knew that I was an outsider. I was told at the beginning of my career that with a name like Nigel Mansell I would never make it to Formula 1 or make anything of myself in life. I guess I proved them wrong.

In the early stages of my racing career, as I struggled to scrape together the money to pursue my dream, I became aware of a group of drivers whom I nicknamed âThe Chosen Onesâ. These are the people who are expected to make it, to go all the way to the top. The phrase âfuture World Championâ is bandied about with reference to these people, some of whom do make it, many of whom donât. What unites them is that they have the backing and support of wealthy sponsors or corporations and their path to the top is marked out for them. Influential people in the industry back them and tip off the magazines and newspapers to âkeep an eye on this boyâ. Consequently they get a lot of publicity and this pleases their sponsors, who put in more money. If youâve got the money in this sport, you get the best equipment and on it goes. You can understand why these people are âThe Chosen Onesâ, because in this sport you need a lot of money and support to make it and people are unwilling to back outsiders, like me, who have no money.

But the unavoidable truth of the sport is that it takes talent to win races and championships. You cannot compete at the highest levels without having that talent. When I was coming through the ranks, âThe Chosen Onesâ were drivers like Andrea de Cesaris and Chico Serra. They got huge backing and much ink was put on paper about how they would conquer the world. Yet neither of them won a single Grand Prix. Chico Serra was run in Formula 3 by Ron Dennis, now the boss of McLaren, and they used to have their own video cameras out on every corner so they could analyse what the car was doing. And yet Chico came up to me on the grid one day and said, âExcuse me Nigel, could you tell me how many revs youâre using at the start?â

The history of the sport is littered with examples like this and itâs still going on today. Maybe there is a young outsider out there who is struggling to get the money together but has the self-belief and the determination never to give up. If there is, I hope he draws strength from this story and I wish him the best of luck. Heâs going to need it.

Others, like Ayrton Senna, Alain Prost and Michael Schumacher were more successful. None of them spent much time in poor equipment and all of them were well financed along the way. The main thing which united them, however, was their supreme talent. It annoys me when I read that I do not have the natural talent of a Senna or a Prost and that I âmade myselfâ a great driver. Firstly, you cannot run with, let alone consistently beat guys like that unless you have as much talent and, secondly, I have the satisfaction of knowing that two of the sportâs greatest figures, Colin Chapman of Lotus and Enzo Ferrari, both considered me to be one of the most talented drivers they had ever hired. Their opinions speak for themselves.