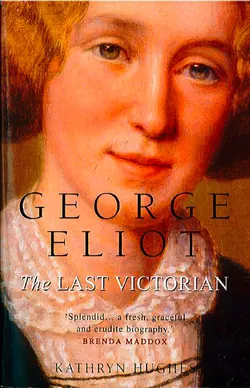

George Eliot: The Last Victorian

Kathryn Hughes

This highly praised biography is the first to explore fully the way in which her painful early life and rejection by her brother Isaac in particular, shaped the insight and art which made her both Victorian England’s last great visionary and the first modern.An immensely readable biography of the 19th century writer whose territory comprised nothing less than the entire span of Victorian society. Kathryn Hughes provides a truly nuanced view of Eliot, and is the first to grapple equally with the personal dramas that shaped her personality – particularly her rejection by her brother Isaac – and her social and intellectual context. Hughes shows how these elements together forged the themes of Eliot’s work, her insistence that ideological interests be subordinated to the bonds between human beings – a message that has keen resonance in our own time. With wit and sympathy Kathryn Hughes has written a wonderfully vivid account of Eliot’s life that is both moving, stimulating and at times laugh-out-loud funny.

GEORGE

ELIOT

The LAST VICTORIAN

KATHRYN HUGHES

Dedication (#ulink_63273674-0d82-5436-8bf1-5e99b0cdd29b)

For my parentsAnne and John Hughesagain

Contents

Cover (#u942968c2-ebe3-59c7-85d9-7d1924a026b1)

Title Page (#u5ded3ce2-618a-5459-b5d8-13ff6b9d27b0)

Dedication (#u6a18e7d7-d47c-50a4-8640-c10a692eba94)

CHAPTER 1: ‘Dear Old Griff’ Early Years 1819–28 (#ud55b5d77-c841-5992-a195-053c3a43d68d)

CHAPTER 2: ‘On Being Called a Saint’ An Evangelical Girlhood 1828–40 (#u5b67cef4-dd52-5843-8d00-e64148505e7b)

CHAPTER 3: ‘The Holy War’ Coventry 1840–1 (#u24c9358d-2858-595b-8489-0949b65cdeb1)

CHAPTER 4: ‘I Fall Not In Love With Everyone’ The Rosehill Years 1841–9 (#ud6ea970e-a7bc-557f-b58f-a64003f60d8f)

CHAPTER 5: ‘The Land of Duty and Affection’ Coventry, Geneva and London 1849–51 (#uf92a7d20-3b7c-5367-8967-c489d49bbe5f)

CHAPTER 6: ‘The Most Important Means of Enlightenment’ Life at The Westminster Review 1851–2 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 7: ‘A Man of Heart and Conscience’ Meeting Mr Lewes 1852–4 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 8: ‘I Don’t Think She Is Mad’ Exile 1854–6 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 9: ‘The Breath of Cows and the Scent of Hay’ Scenes of Clerical Life and Adam Bede 1856–9 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 10: ‘A Companion Picture of Provincial Life’ The Mill on the Floss 1859–60 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 11: ‘Pure, Natural Human Relations’ Silas Marner and Romola 1860–3 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 12: ‘The Bent of My Mind Is Conservative’ Felix Holt and The Spanish Gypsy 1864–8 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 13: ‘Wise, Witty and Tender Sayings’ Middlemarch 1869–72 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 14: ‘Full of the World’ Daniel Deronda 1873–6 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 15: ‘A Deep Sense of Change Within’ Death, Love, Death 1876–80 (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Select Bibliography (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Notes (#litres_trial_promo)

Praise (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 1 (#ulink_72659ca2-b890-5e41-89ec-6f9e9e97fbea)

‘Dear Old Griff’ (#ulink_72659ca2-b890-5e41-89ec-6f9e9e97fbea)

Early Years 1819–28 (#ulink_72659ca2-b890-5e41-89ec-6f9e9e97fbea)

IN THE EARLY hours of 22 November 1819 a baby girl was born in a small stone farmhouse, tucked away in the woodiest part of Warwickshire, about four miles from Nuneaton. It was not an important event. Mary Anne was the fifth child and third daughter of Robert Evans, and the terse note Evans made in his diary of her arrival suggests that he had other things to think about that day.

(#litres_trial_promo) As land agent to the Newdigate family of Arbury Hall, the forty-six-year-old Evans was in charge of 7000 acres of mixed arable and dairy farmland, a coal-mine, a canal and, his particular love, miles of ancient deciduous forest, the remnants of Shakespeare’s Arden. A new baby, a female too, was not something for which a man like Robert Evans had time to stop.

Six months earlier another little girl, equally obscure in her own way, had been born in a corner of Kensington Palace. Princess Alexandrina Victoria was also the child of a middle-aged man, the fifty-two-year-old Prince Edward of Kent, himself the fourth son of Mad King George III. None of George’s surviving twelve children had so far managed to produce a viable heir to succeed the Prince Regent, who was about to take over as king in his own right. It had been made brutally clear to the four elderly remaining bachelors, Edward among them, that the patriotic moment had come to give up their mistresses, acquire legal wives and produce a crop of lusty boys. But despite three sketchy, resentful marriages, the desired heir had yet to appear. Still, at this point it was too soon to give up hope completely. Princess Alexandrina Victoria, born on 24 May 1819, was promisingly robust and her mother, while past thirty, was young enough to try again for a son. If anyone bothered to think ahead for the little girl, the most they might imagine was that she would one day become the elder sister of a great king.

Officially the futures of these two little girls, Mary Anne and Alexandrina Victoria, were not promising. As for every other female child born that year, the worlds of commerce, industry and the professions were closed to them. As adults they would not be able to speak in the House of Commons, or vote for someone to do so on their behalf. They would not be eligible to take a degree at one of the ancient universities, become a lawyer, or manage the economic processes which were turning Britain into the most powerful nation on earth. Instead, their duties would be assumed to lie exclusively at home, whether palace or farmhouse, as companions and carers of husbands, children and ageing parents.

Yet that, as we know, is not what happened. Neither girl lived the life that the circumstances of her birth had seemed to decree. Instead, each emerged from obscurity to define the tone and temper of the age. Princess Alexandrina Victoria, pushed further up the line of succession by her father’s early death, even gave her name to it. ‘Victorian’ became the brand name for a confident, expansive hegemony which was extended absent-mindedly beyond her own lifetime. ‘Victorian’ was the sound of unassailable depth, stretch and solidity. It meant money in the bank and ships steaming the earth, factories that clattered all night and buildings that stretched for the sky. Its shape was the odd little figure of Victoria herself, sweet and girlish in the early years, fat and biddyish at the end. Wherever ‘Victorian’ energy and bustle made themselves felt, you could be sure to find that distinctive image, stamped into coins and erected in stone, woven into tablecloths and framed in cheap wood. In its ordinary femininity the figure of Victoria offered the moral counterpoise to all that striving and getting. The solid husband, puffy bosom and string of children represented the kind of good woman for whom Britain was busy getting rich.

George Eliot’s image, by contrast, was rarely seen by anyone. Indeed, it was whispered that she was so hideous that, Medusalike, you only had to look upon her to be turned to stone. And her name, during its early years of fame, suggested the very opposite of Victorianism. Her avowed agnosticism, sexual freedom, commercial success and childlessness were troubling reminders of everything that had been repressed from the public version of life under the great little Queen. By 1860 Victoria and Eliot had come to stand for the twin poles of female behaviour, respectability and disgrace. One gave her name to virtuous repression, a rigid channelling of desire into the safe haven of marriage and family. The other, made wickeder by male disguise, became a symbol of the ‘Fallen Woman’, banished to the edges of society or, in Eliot’s actual case, to a series of dreary suburban exiles.

That was the bluster. In real life – that messy matter which refuses to run along official lines – the Queen and Eliot shared more than distracted, greying fathers. Their emotional inheritance was uncannily similar and pressed their lives into matching moulds. Both had mothers who were intrusive yet remote, a tension which left them edgy for affection until the end of their days. Victoria slept in the Duchess of Kent’s room right up to her coronation, while Eliot spent her first thirty years looking for comfortable middle-aged women whom she could call ‘Mother’. When it came to men, both clung with the hunger of children rather than the secure attachment of grown women. Prince Albert and George Henry Lewes not only negotiated the public world for their partners, but lavished them with the intense and symbiotic affection usually associated with maternally minded wives. And when both men died before them, their widows fell into an extended stupor which recalled the despair of an abandoned baby.

What roused them in the end were intense connections with new and unsuitable men. The Queen found John Brown, then the Munshi, both servants, one black. Eliot, meanwhile, married John Cross, a banker twenty years younger and with nothing more than a gentleman’s education. Menopausal randiness was sniggeringly invoked as the reason for these ludicrous liaisons. Victoria was called ‘Mrs Brown’ behind her back. And when John Cross had to be fished out of Venice’s Grand Canal during his honeymoon, the whisper went round the London clubs that he had preferred to drown rather than make love to the hideous old George Eliot.

Because of Eliot’s ‘scandalous’ private life, which actually the Queen did not think so very bad, there was no possibility of the two women meeting. Yet recognising their twinship, they stalked each other obliquely down the years. Eliot first mentions Victoria in 1848 when, having briefly caught the revolutionary mood, she speaks slangily in a letter of ‘our little humbug of a queen’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Ironically, only eleven years later, Victoria had fallen in love with Eliot’s first full-length novel, Adam Bede, because of what she saw as its social conservatism, its warm endorsement of the status quo. The villagers of Hayslope, headed by Adam himself, reminded her of her beloved Highland servants, and in 1861 she commissioned paintings of two of the book’s central scenes by the artist Edward Henry Corbould.

George Eliot noticed how hard the Queen took the loss of Prince Albert in 1861 and, aware of the similarities in their age and temperament, wondered how she would manage the dreadful moment when it came to her. The Queen, in turn, was touched by the delicate letter of condolence that Eliot and Lewes wrote to one of her courtier’s children on his death and asked whether she might tear off their double signature as a memento.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The Queen’s daughters went even further. By the 1870s Eliot’s increasing celebrity and the evident stability of her relationship with Lewes meant that she was no longer a total social exile. Among the great and the good who pressed for an introduction were two of the royal princesses. Brisk and bright, Vicky and Louise lobbied behind the scenes for a meeting and then, in Louise’s case at least, dispensed with royal protocol by coming up to speak to George Eliot first.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The princesses were among the thousands of ordinary Victorians, neither especially clever nor brave, who ignored the early grim warnings of clergymen and critics about the ‘immorality’ of George Eliot’s life and work. By the 1860s working-class men and middle-class mothers, New Englanders (that most puritan of constituencies) and Jews, Italians and Australians were all reading her. Cheap editions and foreign translations carried George Eliot into every kind of home. Even lending libraries, those most skittishly respectable of ‘family’ institutions, bowed to consumer demand and grudgingly increased their stock of Adam Bede and The Mill on the Floss.

What is more, all these Victorians read the damnable George Eliot with an intensity and engagement that was never the case with Dickens or Trollope. While readers of Bleak House might sniff over the death of Jo and even stir themselves to wonder whether something might not be done for crossing-sweepers in general, they did not bombard Dickens with letters asking how they should live. That intimate engagement was reserved for Eliot, who alone seemed to understand the pain and difficulty of being alive in the nineteenth century. From around the world, men and women wrote to her begging for advice about the most personal matters, from marriage through God to their own poetry. Or else, like Princess Louise, they stalked her at concert halls, hoping for a word or a glance.

The worries which Eliot’s troubled readers laid before her concerned the dislocations of a social and moral world that was changing at the speed of light. Here were the doubts and disorientations that had been displaced from that triumphant version of Victorianism. An exploding urban population, for instance, might well suggest bustling productivity, but it could also mean a growing sense of social anomie. Rural communities were indeed invigorated by their new proximity to big towns, but they were also losing their fittest sons and daughters to factories and, later, to offices and shops. Meanwhile the suburbs, conceived as a rus in urbe, pleased no one, least of all George Eliot, who spent five years hating Richmond and Wandsworth for their odd mix of nosy neighbours and lack of real green.

For if in one way Victorians felt more separate from each other, in others they were being offered opportunities to come together as never before. It was not just the railway that was changing the psycho-geography of the country, bringing friends, enemies and business partners into constant contact. The postal service, democratised in 1840 by the introduction of the Penny Post, allowed letters to fly from one end of the country to the other at a pace that makes our own mail service look like a slowcoach. Then there was the telephone which, at the end of her life, George Eliot was invited to try. As a result of these changes Victorians found themselves pulled in two directions. Scattering from their original communities, they spent the rest of their lives trying to reconstitute these earlier networks in imaginary forms.

Science, too, was taking away the old certainties and replacing them with new and sometimes painful ones. It would not be until 1859 that Darwin would publish Origin of Species, but plenty of other geologists and biologists were already embracing the possibility that the world was older than Genesis suggested, in which case the Bible was perhaps not the last word on God’s word. Perhaps, indeed, it was not God’s word at all, but rather the product of man’s need to believe in something other than himself. This certainly was the double conclusion that Eliot came to during the early anonymous years of her career when she translated those seminal German texts, Strauss’s The Life of Jesus (1835–6) and Feuerbach’s The Essence of Christianity (1841). Her readers likewise wrestled with the awful possibility that there was no moral authority except the one which was to be found by digging deep within themselves. Not only did a godless universe lay terrifying burdens of responsibility upon the individual, but it unsettled the idea of an afterlife. To a culture which had always believed that, no matter how dismal earthly life might be, there was a reward waiting in heaven, this was a horrifying blow beside which the possibility that one was an ape paled into insignificance.

That much-vaunted prosperity turned out to be a tricky business too. For every Victorian who felt rich, there were two who felt very poor indeed, especially during the volatile 1840s and again in the late 1860s. During Eliot’s early years in the Midlands she saw the effect of trade slumps on the lives of working families. As a schoolgirl in Nuneaton she had watched while idle weavers queued for free soup; at home, during the holidays, she sorted out second-hand clothing for unemployed miners’ families. Even her own sister, married promisingly to a gentlemanly doctor, found herself as a widow fighting to stay out of the workhouse.

To middle-class Victorians these sights and stories added to a growing sense that they were not, after all, in control of the economic and social revolution being carried out in their name. Getting the vote in 1832 had initially seemed to give them the power to reshape the world in their own image: the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 had represented a real triumph of urban needs over the agricultural interest. But it soon became clear that early fears that 1832 would be the first step towards a raggle-taggle democracy were justified. On three occasions during the ‘hungry forties’ working-class men and women rallied themselves around the Charter, a frightening document demanding universal suffrage and annual parliaments. By the mid-186os, with the economy newly unsettled, urban working men were once again agitating violently for the vote.

These were worrying times. The fat little figure of the Queen was not enough to soothe Victorians’ fears that the blustery world in which they lived might not one day blow apart completely. In fear and hope they turned to the woman whose name they were initially only supposed to whisper and whose image they were seldom allowed to see. George Eliot’s novels offered Victorians the chance to understand their edginess in its wider intellectual setting and to rehearse responses by identifying with characters who looked and sounded like themselves. Thanks to her immense erudition in everything from theology to biology, anthropology to psychology, Eliot was able to give current doubts their proper historic context. Dorothea’s ardent desire to do great deeds, for instance, is set alongside St Teresa’s matching passion in the sixteenth century and their contrasting destinies explained. In the same way Tom Tulliver’s battles with his sister Maggie are understood not just in terms of their individual personalities, but as the meeting point of several arcs of genetic, cultural, and family conditioning at a particular moment in human history.

While disenchantment with Victorianism led readers to George Eliot, George Eliot’s advice to them was that they should remain Victorians. Despite the ruptures of the speedy present, Eliot believed that it was possible, indeed essential, that her readers stay within the parameters of the ‘working-day world’ – a phrase that would stand at the heart of her philosophy. She would not champion an oppositional culture, in which people put themselves outside the ordinary social and human networks which both nurtured and frustrated them. From Darwin she took not just the radical implications (we are all monkeys, there is probably no God), but the conservative ones too. Societies evolve over thousands of years; change – if it is to work – must come gradually and from within. Opting out into political, religious or feminist Utopias will not do. Eliot’s novels show people how they can deal with the pain of being a Victorian by remaining one. Hence all those low-key endings which have embarrassed feminists and radicals for over a century. Dorothea’s ardent nature is pressed into small and localised service as an MP’s wife, Romola’s phenomenal erudition is set aside for her duties as a sick-nurse, Dinah gives up her lay preaching to become a mother.

Eliot’s insistence on making her characters stay inside the community, acknowledge the status quo, give up fantasies about the ballot, behave as if there is a God (even if there isn’t) bewildered her peers. Feminist and radical friends assumed that a woman who lived with a married man, who had broken with her family over religion, who was one of the highest-earning women in Britain, must surely be encouraging others to do the same. And when they found that she did not want the vote for women, that she felt remote from Girton and that she sometimes even went to church, they felt baffled and betrayed.

What Eliot’s critics missed was that she was no reactionary, desperately trying to hold back the moment when High Victorianism would crumble. Right from her earliest fictions, from the days of Adam Bede in 1859, she had understood her culture’s fragility, as well as its enduring strengths. None the less, she believed in the Victorian project, that it was possible for mankind to move forward towards a place or time that was in some way better. This would only happen by a slow process of development during which men and women embraced their doubts, accepted that there would be loss as well as gain, and took their enlarged vision and diminished expectations back into the everyday struggle. In Daniel Deronda, Eliot’s penultimate book and last proper novel, she shows how this new Victorianism, projected on to a Palestinian Jewish homeland, might look and sound. Although it will cohere around a particular social, geographic and religious culture, it will acknowledge other centres and identities. It will know and honour its own past, while anticipating a future which is radically different. By being sure of its own voice, it will be able to listen attentively to those of others.

It was Eliot’s adult reading of Wordsworth and Scott that instilled in her the conviction that ‘A human life, I think, should be well rooted in some spot of a native land … a spot where the definiteness of early memories may be inwrought with affection.’

(#litres_trial_promo) But it was during her earliest years, as she accompanied her father around the Arbury estate in his pony trap, that she fell deeply in love with the Midlands countryside. Her ‘spot’ was Warwickshire, the midmost county of England. Uniquely, the landscape was neither agricultural nor industrial, but a patchwork of both. In a stunning Introduction to Felix Holt, The Radical, George Eliot used the device of a stagecoach thundering across the Midlands on the eve of the 1832 Reform Act to describe a countryside where the old and new sit companionably side by side.

In these midland districts the traveller passed rapidly from one phase of English life to another: after looking down on a village dingy with coal-dust, noisy with the shaking of looms, he might skirt a parish all of fields, high hedges, and deep-rutted lanes; after the coach had rattled over the pavement of a manufacturing town, the scene of riots and trades-union meetings, it would take him in another ten minutes into a rural region, where the neighbourhood of the town was only felt in the advantages of a near market for corn, cheese, and hay.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Mary Anne’s early life, contained within the four walls of Griff farmhouse, where her family moved early in 1820, still belonged securely to the agricultural ‘phase of English life’ and was pegged to the daily and seasonal demands of a mixed dairy and arable farm. Although there were male labourers to do the heavy work and female servants to help in the house, much of the responsibility was shouldered by the Evans family itself. Like many of the farmers’ wives who appear in Eliot’s books, Mrs Evans took particular pride in her dairy, running it as carefully as Mrs Poyser in Adam Bede, who continually frets about low milk yields and late churnings. Like the wealthy but practical Nancy Lammeter in Silas Marner, too, Mrs Evans and her two daughters had bulky, well-developed hands which ‘bore the traces of butter-making, cheese-crushing, and even still coarser work’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Some years after George Eliot’s death, a rumour circulated in literary London that one of her hands was bigger than the other, thanks to years of turning the churn. It was a story which her brother Isaac, now gentrified by a fancy education, good marriage and several decades of high agricultural prices, hated to hear repeated.

The rhythms of agricultural life made themselves felt right through Mary Anne’s young adulthood. As a prickly, bookish seventeen-year-old left to run the farmhouse after her mother’s death, she railed against the fuss and bother of harvest supper and the hiring of new servants each Michaelmas. And yet the very depth of her adolescent alienation from this repetitive, witless way of life reveals how deeply it remained embedded in her. Thirty years on and established in a villa in London’s Regent’s Park, her first thought about the weather was always how it would affect the crops.

But life on the Arbury estate was no bucolic idyll. The Newdigate lands contained some of the richest coal deposits in the county. As she grew older, the fields in which Mary Anne played had names like Engine Close and Coal-pit Field. Lumps of coal lay casually amid the grass. At night the girl was kept awake by the chug-chug of the Newcomen engine pumping water out of the mine less than a mile from her home. The canal in which she and Isaac fished was busy with barges taking the coal to Coventry. And when Mary Anne accompanied her father on his regular visits to Mr Newdigate at Arbury Hall, she would have noticed the huge crack which cut across the gold-and-white ceiling of the magnificent great hall. Subsidence caused by the mine-working had dramatically marked a building whose elaborate refashioning only a generation before had come to stand for everything that was elegantly Arcadian about aristocratic life.

Nor did Mary Anne have to look very far to fit the uneven textures of the Arbury estate into the wider landscape. Most of the people in the scrappy hamlet of Griff were not farm labourers but miners. In the nearby villages people were mainly employed in cottage industries like nail making, ribbon weaving and framework knitting. The pale faces and twisted bodies of the handloom weavers struck Mary Anne as absolutely different from the Arbury farmers, a contrast she was to use later in suggesting the weaver Silas Marner’s alienation from his ruddy Raveloe neighbours.

Only a few miles along the road was Nuneaton, the market town where Mary Anne was soon to go to school. In her very first piece of fiction she describes the town – renamed Milby – as a place where intensive homeworking had already left its grimy mark: ‘The roads are black with coal-dust, the brick houses dingy with smoke; and at that time – the time of handloom weavers – every other cottage had a loom at its window, where you might see a pale, sickly-looking man or woman pressing a narrow chest against a board, and doing a sort of treadmill work with legs and arms.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

As Eliot’s description of hard labour and pinched surroundings suggests, these were not prosperous times for the Midlands. Victory over Napoleon in 1815 had meant an end to protection against imports of French and Swiss ribbon. A couple of months before Mary Anne’s birth, a cut in the rate paid to silk weavers brought an angry crowd out on to the street. There was jeering and jostling, and a man accused of working under-price was tied backwards on a donkey and led through the streets.

(#litres_trial_promo) Later, as a schoolgirl in Nuneaton, she was to see hunger-fuelled rioting at first hand.

As Mary Anne followed her father from miner’s cottage to farmhouse to Arbury Hall itself, she learned to place herself within this complex social landscape. She noted that while tenant farmers might nod respectfully at her, when she got to Arbury Hall, she was left in the housekeeper’s room while her father went to speak to the great man. She observed a whole range of accents, dress, customs and manners against which her own must be measured and adjusted. In this way she built up a library of visual and aural references to which she could return in her imagination when she was sitting, years later, in Richmond trying to recapture the way a gardener or a clergyman spoke. It was this faithfulness to the actual past, rather than a greetings-card version of it, which was to become a plank in her demand for a new kind of realism in fiction. In Adam Bede she breaks off in the middle of describing the young squire’s coming-of-age party to ask her sentimental, suburban reader: ‘Have you ever seen a real English rustic perform a solo dance? Perhaps you have only seen a ballet rustic, smiling like a merry countryman in crockery, with graceful turns of the haunch and insinuating movements of the head. That is as much like the real thing as the “Bird Waltz” is like the song of the birds.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Mary Anne Evans had not only seen labourers dancing, she had watched them getting drunk, making love, milking and shearing. She had been patronised by the gentry and petted by their servants. And while these pictures were neither charming nor quaint, they sustained her sense of being rooted in a community which was to carry her through the long years of urban exile. She knew every field, every hedgerow and every clump of trees. In later life, she had only to close her eyes and she could conjure up the smell of cows’ breath, hay and fresh rain. But she also knew the way the muddy canal absorbed the sunlight and the noise the looms made as the weavers worked into the night. Looking at the world through her father’s expert eyes, she learned to see that these two strands of life were not conflicting, but that they represented a particular moment in the development of English life. The rural community had not been destroyed, but it was being radically regeared towards technology, profit and the power of the individual to manage his own life. And no one had benefited more from these changes than Robert Evans.

Evans had been born in Roston Common, Derbyshire, in 1773, one of eight children. There were the usual family romances about gentry stock, but by the time Robert arrived any grand connections were nothing more than stories. His father, George, was a carpenter and his mother was called Mary Leech. The five Evans boys were determined to ride the wave of social and economic expansion unleashed by the first phase of industrialisation. Second son William rose to be a wealthy builder, while Thomas overcame a shaky start to become county surveyor for Dorset. Even dreamy Samuel, who turned Methodist and kept his eye on the future world, ran a ribbon factory. Only the eldest boy, George, was unsteady. He boycotted the family’s carpentry business and there was talk of heavy drinking. When he died, the Evans clan turned its collective and implacable back on his young children.

Mary Anne was to experience both sides of this Evans legacy. Like her father and his brothers, she rose out of the class into which she was born by dint of hard work and talent. She left behind the farm, the dairy and the brown canal, and fashioned herself into one of the leading intellectual and literary artists of the day. But just like her Uncle George – was it coincidence that she took his name as the first half of her writing pseudonym? – she learned what it was like to belong to a family which regularly excluded those of whom it did not approve. When, at the age of twenty-two, she announced that she did not believe in God, her father sent her away from home. Fifteen years later, when she was living with a man to whom she was not married, her brother Isaac instructed her sisters never to speak or write to her again. The Evanses, like thousands of other ambitious families at that time, demanded that its members forge their individual destinies while skirting nonconformity.

In the case of the Evans boys, those destinies were forged in the workshop rather than the classroom. When they did attend school – run by Bartle Massey, a name which would crop up in Adam Bede – it was to learn accounting, ‘mechanics’ and ‘to write a plain hand’. Robert’s hand did indeed remain plain all his adult life, but despite almost daily entries in his journal and a constant correspondence with his employers, he was never to become comfortable with the pen. Reading his papers remains a tricky business, thanks to patchy punctuation, haphazard spelling and a whimsical use of capitals and italics. ‘Balance’ becomes ‘ballance’, ‘laughed’ is ‘laph’d’, while ‘their’ and ‘there’ are constantly confused. Despite a career of forty years spent note-taking and report-making, Robert Evans remained uneasy with the written word, finding, like Mr Tulliver in The Mill on the Floss, ‘the relation between spoken and written language, briefly known as spelling, one of the most puzzling things in this puzzling world’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Evans preferred to dwell in the stable and particular. As a young carpenter he had learned how to turn the elms and ash of Derbyshire and Staffordshire into windows, tables and doors. And as he walked through the forest on his way to the farmhouses where he was employed, he looked around at the trees that ended up on his work-bench. He took note of the conditions under which the best wood flourished. He saw when a stand was ready to be cut and when it should be left for a few weeks more. Later in his career it was said that he had only to look at a tree to know exactly how much timber it would yield.

To any landed proprietor, intent not simply on gazing at his parkland but increasing its profit, a man like Evans could be useful. It was now that he came to the attention of Francis Parker, a shrewd young gentleman of about the same age, who spotted the carpenter’s potential to be more than a maker of cottage doors and fancy cabinets. Parker persuaded his father – another Francis Parker – to put Evans to work managing Kirk Hallam, their Derbyshire estate. So began Evans’s career as a self-made man. Reworked in fiction as the ruptured rivalrous bond between Adam Bede and Arthur Donnithorne, the real-life Parker and Evans remained cordial, but always mindful of their vastly different stations. Over the next forty years they offered each other – often by letter, since Parker lived much of the time in Blackheath, Kent – cautious encouragement and condolence as the trials of their parallel lives unfolded.

(#litres_trial_promo)

In 1806, by a cat’s cradle of a will, Francis Parker senior inherited a life interest in the magnificent Warwickshire estate of Arbury Hall from his cousin Sir Roger Newdigate. Parker, now renamed Newdigate, moved to Arbury and brought Evans with him as his agent. Evans, by now thirty-three and a father of two, was installed at South Farm, from where he could manage the 7000-acre estate while running his own farm.

The Evans family and the Parker-Newdigate clan had attached themselves to one another in a mutually beneficial arrangement which was to last right down the nineteenth century. While the Newdigates spent many years and much money pursuing pointless lawsuits about who was responsible for what under the terms of Roger Newdigate’s eccentric will, the Evans brothers quietly consolidated their own empire. With Robert now moved to Warwickshire, Thomas and William stayed behind to manage the Newdigates’ Derbyshire and Staffordshire estates. The moment Robert’s eldest boy was old enough, he was sent back to Derbyshire to learn the family trade. And when occasionally something did go wrong, Robert Evans stepped in quickly to make sure that there was no blip in the steady arc of the family’s influence. In 1835 brother Thomas went bankrupt. This was a potential disaster, since if Thomas left his farm at Kirk Hallam he would also have to give up as estate manager. Robert immediately proposed a solution to his employer whereby he would become the official tenant of the farm, allowing Thomas and his son to continue to work the land and stay in place.

(#litres_trial_promo) In the Evanses’ world, business relationships always took precedence over family ones. Although during Mary Anne’s childhood Robert made regular trips northwards, on only a couple of occasions did he take her with him to meet her uncles and aunts. Their odd-sounding dialect struck her as strange, but years later she found good use for it when she came to create the North Midlands accents in Adam Bede.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Evans applied the same canny caution to his personal life. While working in Staffordshire he had noticed a local girl called Harriet Poynton. She was a servant, but a superior one. Since her teens she had been lady’s maid to the second Mrs Parker-Newdigate senior and occupied a position of unparalleled trust. Her duties would have involved looking after the wardrobe and toilet of her mistress, buttoning her up in the morning and brushing out her hair at night. Constantly in her mistress’s presence, the lady’s maid frequently became the recipient of cast-off clothes, gossip and affection. All the signs suggest that Mrs Parker-Newdigate looked on Harriet as something like a daughter. Marriage to Harriet Poynton cemented Robert Evans’s ties to his employers. The Parker-Newdigates were presumably delighted that two of their favourite servants had forged an alliance. At the very least it meant that their own comforts and conveniences would not be disturbed. In an unusual arrangement, Mrs Parker-Newdigate, now moved to Arbury Hall, insisted that Harriet continue to work after her marriage.

We know nothing of the courtship. It is hard to imagine Robert Evans divulging much beyond the current cost of elm or the need to drain the top field. But this was not about romance. Evans offered the thirty-one-year-old Harriet the respectability of marriage without the need to leave her beloved mistress. In return, her ladylike manner promised usefully to soften his blunt ways and flat vowels. They married in 1801 and children followed quickly. Robert was born in 1802, Frances Lucy, shrewdly named for Mrs Parker-Newdigate, in 1805.

In the end, it was Harriet’s attachment to her mistress that killed her. In 1809 Mrs Parker-Newdigate went down with a fatal illness to which the heavily pregnant Harriet also succumbed. A baby girl, also Harriet, was born, but died shortly afterwards and was buried with her mother. In acknowledgement of her unique relation to them in both life and death, the Parker-Newdigates took the unusual step of adding Harriet’s name – ‘faithful friend and servant’ – to the family memorial stone in nearby Astley Church.

Like all widowers with children, Robert Evans needed to marry again and quickly. We do not know who looked after the babies during the four years before he took his second wife. Perhaps Harriet’s family rallied round. Maybe one of his sisters from Derbyshire came to help at South Farm. The next thing known for certain, however, is that he made another smart match. Christiana Pearson was the youngest daughter of Isaac Pearson, a yeoman who farmed at Astley. Yeoman farmers were freeholders and so harder to place socially than those who rented their farms, a point which was to unsettle the snobbish Mrs Cadwallader in Middlemarch.

(#litres_trial_promo) The Pearsons were certainly not gentry, but they were prosperous, active sort of people, used to serving as church wardens and parish constables. If Evans’s first marriage confirmed his allegiance to the Newdigates, his second proclaimed a growing independence from them.

The Pearson daughters – there were four of them – embodied a particular kind of rigid rural respectability which would be reworked by their niece to such powerful and funny effect in the Dodson sisters in The Mill on the Floss. Literary detectives have matched up the Dodsons to the Pearsons exactly. Ann Pearson, who married George Garner of Astley, became the model for Aunt Deane; Elizabeth was second wife of Richard Johnson of Marston Jabbett and formed the basis for rich, pretentious Aunt Pullet; while Mary, second wife of John Evarard of Attleborough, was transformed into thrifty, superstitious Aunt Glegg. The overriding characteristic of the Dodson sisters (and hence the Pearsons) is their sense of superiority on every imaginable topic and an assumed right to comment on those who do not match their exacting standards. ‘There were particular ways of doing everything in that family: particular ways of bleaching the linen, of making the cowslip wine, curing the hams and keeping the bottled gooseberries, so that no daughter of that house could be indifferent to the privilege of having been born a Dodson, rather than a Gibson or a Watson.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Christiana was the youngest of the Pearson girls – there was a brother, too – and perhaps here lies the clue to why she agreed to become Robert Evans’s second wife. Still unmarried in her late twenties, she may have wanted to flee the role of companion and nurse to ageing parents. Perhaps she also wanted protection from her overbearing sisters. At forty-one, Robert Evans was a vigorous man whose reputation as the cleverest agent in the area was growing all the time. No longer a servant exactly, he was a ‘rising man’. South Farm needed a mistress, someone who could run a dairy, organise a household, feed the workmen and supervise the servants. Christiana Pearson could do worse than become the second Mrs Evans.

The marriage, in 1813, produced five children, three of whom survived. First came Christiana, always known as Chrissey, in 1814. Next, in 1816, was Isaac and two and a half years later came Mary Anne. The fact that these were all Pearson names suggests that Mrs Evans’s nearby family continued to take what seemed to them a natural precedence and influence in the children’s lives. That the last baby was a girl – Robert Evans’s third – was probably a disappointment, especially since boy twins born in 1821 did not survive more than a few days. For a man who was still busy building a business dynasty, girls were not especially useful. They could run a farmhouse, but they could not trade, build or farm. Until they married – when they had to be provided with a dowry – they remained a drain on their family’s resources.

Four months after Mary Anne’s birth the family moved to Griff House, the Georgian farmhouse on the Coventry-Nuneaton road which was to be home for the next twenty-one years. It was far more impressive than the boxy South Farm and, together with the attached 280 acres of farmland, represented the high noon of Robert Evans’s status and influence. There were eight bedrooms, three attics and four ground-floor living-rooms. A cobbled courtyard was surrounded by a dairy (which was to become the model for the richly seductive Poyser dairy in Adam Bede), a dovecote and a labourer’s cottage. The four acres of garden were picture-book perfect, with roses, cabbages, raspberry bushes, currant trees and, best of all, a round pond. During her adult years spent in boarding-houses, hotel rooms and ugly suburban villas, Mary Anne’s imagination would return repeatedly to the Eden that was Griff. When, in 1874, Isaac’s daughter Edith sent her some recent photographs of the house, Mary Anne found herself spinning back in time: ‘Dear old Griff still smiles at me with a face which is more like than unlike its former self, and I seem to feel the air through the window of the attic above the drawing room, from which when a little girl, I often looked towards the distant view of the Coton “College” [the workhouse] – thinking the view rather sublime.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Although as a mature novelist George Eliot referred repeatedly to memory and childhood as the bedrock of the adult self, she actually left very little direct information about her own early years. Even John Cross, the man she married eight months before her death, wrestled with large gaps as he attempted to recall his wife’s childhood for the readers of his three-volume George Eliot’s Life as Related in Her Letters and Journals, published in 1885. To bulk out his first chapter he leaned heavily on the account of Maggie Tulliver’s early years in The Mill on the Floss, introducing distortions which biographers spent the next hundred years consolidating into ‘fact’.

Drawing on the relationship between Mr Tulliver and Maggie, Cross has Robert Evans clucking in wonder at the cleverness of his ‘little wench’ and making her a special pet. In fact, there is no evidence that Evans had a particular fondness for Mary Anne, although plenty to suggest that she worshipped him. By the time his youngest child was born, Evans was forty-six years old and established in both his career and family life. A head-and-shoulders portrait from 1842 shows him massive and impassive as a piece of great oak.

(#litres_trial_promo) A high, wide forehead gives way to a long nose and broad lips – features that were repeated less harmoniously in Mary Anne. Evans radiated physical strength – one anecdote has him jauntily picking up a heavy ladder, which two labourers were unable to manage between them. But it was his moral authority that made him a figure to be reckoned with. Once, when travelling on the top of a coach in Kent, a female passenger complained that the sailor sitting next to her was being offensive. Mr Evans changed places with the woman and forced the sailor under the seat, holding him down for the rest of the journey.

(#litres_trial_promo)

It was this reputation for integrity that meant that Evans was increasingly asked to play a part in the burgeoning network of charitable and public institutions, which were becoming part of the rural landscape during the 1820s and 1830s. His meticulous bookkeeping and surveying skills were an asset to church, workhouse and hospital. In a blend of self-interest and social responsibility, he was able to take advantage of this move towards a professional bureaucracy by charging fees for services rendered. Less officially he also became known as someone who would discreetly lend money to embarrassed professional men, including the clergy. By charging a fair interest, the frugal carpenter’s son was able to make a profit out of those gentlemen who had been less successful than himself at negotiating the violent swings of the post-war economy.

But the heart of Evans’s empire would always remain his work as a land agent. This was what he understood and where he excelled. Since the middle of the previous century English agriculture had been developing along capitalist lines. The careless old ways of farming were giving way to scientific methods, which promised to yield bigger crops and profits. Landowners now employed professional agents to oversee the efficient running of their estates. It was Robert Evans’s job to ensure that the Newdigate tenant farmers kept their land properly fenced, drained and fertilised.

(#litres_trial_promo) Livestock was carefully chosen according to its suitability for particular pasture. Farm buildings were to be light, airy and dry. Evans was an excellent draughtsman, and one of his letters to his employer includes a meticulous scale drawing of a proposed farm cottage, complete with threshing floor, corn bay, straw bay, cowshed, kitchen and dairy. Dorothea Brooke would have been delighted.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Evans’s expertise encompassed every aspect and activity of the Arbury estate. He regularly inspected the coal-mine, arranged for roads to be built and kept a watchful eye on the quarries, which were only a few yards from the gates of Griff House. As his reputation grew throughout the region, Evans came to be seen less as a clever servant of the Newdigates and increasingly as a professional man in his own right. Several other local landowners, including Lord Aylesford at Packington, now asked him to manage their land. Evans’s relationship with the Newdigates became subtly different as he started to carry himself with more authority. Francis Parker-Newdigate senior was, according to local sources, ‘a despisable character – a bad unfeeling Landlord’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Evans was not prepared to carry out policies which he felt to be unfair. In 1834 he suggested to Newdigate that a particularly bad wheat harvest obliged him to return a percentage of the rent to the tenants. The old man was typically reluctant, so Evans wrote directly to his son, now Colonel Newdigate, in Blackheath. Permission to refund came back immediately.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Years later, as interest in George Eliot’s social origins reached fever pitch, a rumour arose that her father had been nothing more than a tenant farmer. According to this reading, Eliot’s literary achievement became heroic, the stuff of fairy-tales, instead of the continuation of a trajectory which had started long before she was born. Indignantly, Eliot intervened to explain her father’s status as a man of accomplishment and skill, in the process putting her own achievement into a more realistic context.

My father did not raise himself from being an artizan to be a farmer: he raised himself from being an artizan to be a man whose extensive knowledge in very varied practical departments made his services valued through several counties. He had large knowledge of building, of mines, of plantation, of various branches of valuation and measurement – of all that is essential to the management of large estates. He was held by those competent to judge as unique amongst land agents for his manifold knowledge and experience, which enabled him to save the special fees usually paid by landowners for special opinions on the different questions incident to the proprietorship of land.

(#litres_trial_promo)

For all his modernity, Robert Evans remained a staunch conservative. Like many children who had gone to bed hearing stories of Madame Guillotine, he fetishised the need for strong government. And government, for him, must always be rooted in the power and prestige of land. It was not to Westminster he looked for leadership, but to the alliance of squire and clergy serving together on the magistrates’ bench. Evans believed in keeping corn prices high by means of artificial protection even if that meant townsmen having to pay more for their bread. The notorious ‘Peterloo’ incident, a few months before Mary Anne’s birth, in which the cavalry cut a murderous swathe through thousands of people gathered in Manchester to protest against the Corn Laws, would have drawn from Evans a shiver of fear followed by a glow of approbation. Closer to home, the violent hustings at Nuneaton in December 1832 would have confirmed his suspicion that extending the franchise to men with no stake in the land could result only in a permanent breakdown of precious law and order.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Even if Robert Evans had not been a natural conservative, ties of deference and duty to the Newdigates meant that he was obliged to follow them in supporting the Tory party. He attended local meetings on the family’s behalf and in 1837 made sure the tenants turned up to the poll by ‘treating’ them to a hearty breakfast. At times his support for the Tories against the reforming Whigs took on the flavour of a religious battle. Describing his efforts at the 1837 election in a letter to Colonel Newdigate, he urged ‘we must not loose a Vote if we can help it’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

We know less about Mrs Evans. Eliot mentions her only twice in her surviving letters, and Isaac and Fanny seem to have been unable to recall a single thing about her for John Cross when he interviewed them after his wife’s death. Cross’s solution was to take the generalised and evasive line, followed by many biographers since, that Mary Anne’s mother was ‘a woman with an unusual amount of natural force – a shrewd practical person, with a considerable dash of the Mrs Poyser vein in her’,

(#litres_trial_promo) referring to the bustling farmer’s wife in Adam Bede. But what evidence there is suggests that Christiana Evans was actually more like Mrs Tulliver in The Mill on the Floss, a kind of Mrs Poyser minus the energy and wit, but with a similar stream of angry complaints issuing from her thin lips. Anecdotal sources indicate that from the time of her last two confinements Mrs Evans was in continual ill-health. She had, after all, lost twin boys eighteen months after Mary Anne’s birth. For a woman who had already produced two girls, losing two sons, especially towards the end of her fertile years, must have been a blow. Whether this was the lassitude of bereavement, depression or physical exhaustion is not clear, but the impression that emerges is of a woman straining to cope with the demands of her family.

Raising stepchildren is never easy, but Christiana seems to have found it intolerable, especially once she had three babies of her own to look after. Around the time of Mary Anne’s birth, seventeen-year-old Robert was dispatched to Derbyshire to manage the Kirk Hallam estate, with fourteen-year-old Fanny accompanying him as his housekeeper and, later, as governess to a branch of the Newdigate family. It may not have been a formal banishment, but the effect was to stretch the elder children’s relationship with their father and his second family to the point where on their occasional visits home they were greeted as stiffly as strangers.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Chrissey, too, was rarely seen at Griff. According to John Cross, ‘shortly after her last child’s birth … [Mrs Evans] became ailing in health, and consequently her eldest girl, Christiana, was sent to school at a very early age, to Miss Lathom’s at Attleboro’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Even during the holidays Chrissey rarely appeared at home: her biddable personality made her a favourite with the Pearson aunts who were happy to take her off their youngest sister’s hands. Only Isaac was allowed to stay at Griff to the more reasonable age of eight or nine. Even at the end of her life, Eliot had no doubts that Isaac had been their mother’s favourite. In part this was due to temperamental similarity. The boy’s subsequent development suggests that he was a Pearson through and through – rigid, respectable, intolerant of different ways of doing things. But it may also be the case that Christiana was a woman who found it easier to love her sons – both living and dead.

Critics have long noted the lack of warm, easy mother-child relationships in Eliot’s novels. Mothers are often dead and if they survive, then, like Mrs Bede, Mrs Holt and Mrs Tulliver, they are both intrusive and rejecting, swamping and fretful. Mrs Bede and Mrs Holt both demand constant attention from their sons by complaining about them. Mrs Tulliver, likewise, cannot leave Maggie alone. She worries away at the child’s grubby pinafores, stubborn hair and ‘brown skin as makes her look like a mulatter … it seems hard as I should have but one gell, an’ her so comical’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Throughout her career George Eliot repeatedly explored what it is like to be the child of such a mother, one who both pulls you towards her and pushes you away. In a late poem, ‘Self and Life’, she describes the lingering desolation of being put down too suddenly from a warm maternal lap.

(#litres_trial_promo) Speaking in the more accessible prose of The Mill on the Floss, she shows the way in which a child in this situation responds with an infuriating mix of attention-seeking and self-punishing behaviour. In angry reply to Aunt Pullet’s insensitive suggestion that her untidy hair should be cropped, Maggie Tulliver seizes the scissors and does the job herself.

(#litres_trial_promo) In another incident she retreats to the worm-eaten cobwebby rafters, surely based on the attic at Griff, where she keeps a crude wooden doll or ‘fetish’ and, concentrating this time on the image of hated Aunt Glegg, drives a nail hard into its head. When her rage is exhausted, she bursts into tears and cradles the doll in a passion of remorse and tenderness.

(#litres_trial_promo) Maggie’s swoops from showy self-display to brutal self-punishment were rooted in the violent swings of Mary Anne’s own childhood. An anecdote from around the age of four has her thumping the piano noisily in an attempt to impress the servant with her mastery of the instrument. Five years later she is cutting off her hair, just like Maggie. This sense that her childhood had been a time of uneasy longing remained with the adult Mary Anne. In 1844, at the age of twenty-five, she wrote to her friend Sara Hennell: ‘Childhood is only the beautiful and happy time in contemplation and retrospect – to the child it is full of deep sorrows, the meaning of which is unknown.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Rejection by her mother forced Mary Anne to look elsewhere for a passionate, intimate connection. At the age of three she fell violently in love with her elder brother Isaac. She trotted behind him wherever he went, following him as he climbed trees, fished or busied himself with imaginary adventures down by the quarry. The Eden that was Griff now had its own tiny Adam and Eve. Eliot’s ‘Brother and Sister’ sonnets, written in 1869, open with a description of the children as romantic soulmates, twins, each other’s missing half.

I cannot choose but think upon the time

When our two lives grew like two buds that kiss

At lightest thrill from the bee’s swinging chime,

Because the one so near the other is.

(#litres_trial_promo)

But while they may be deeply attached to one another, there is still division and difference in this Eden. The boy in the sonnets and Tom in The Mill on the Floss are older, bigger and more powerful than the little sisters who dote on them. The girl in the sonnets watches, admiring, while her brother plays marbles or spins tops; Maggie idolises Tom as the fount of all practical knowledge. And to cope with this power imbalance, Maggie likes to fantasise that the positions are reversed. In a cancelled passage from The Mill on the Floss, she imagines that,

Tom never went to school, and liked no one to play with him but Maggie; they went out together somewhere every day, and carried either hot buttered cakes with them because it was baking day, or apple puffs well sugared; Tom was never angry with her for forgetting things, and liked her to tell him tales;… Above all, Tom loved her – oh, so much, – more, even than she loved him, so that he would always want to have her with him and be afraid of vexing her; and he as well as everyone else, thought her very clever.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The split, when it comes, is awful. Tom comes home from school to find that Maggie has forgotten to feed his rabbits. His anger is swift and terrible, but it is his gradual pulling away into the realm of boydom which hurts even more. He begins to find Maggie’s adoration tiresome, her chatter silly and her superior cleverness embarrassing. Gradually he turns into the stern, conventional patriarch who scolds, criticises and eventually ignores his wayward sister.

The separation of the boy and girl in the ‘Brother and Sister’ sonnets seems, at first, to be less traumatic. ‘School parted us,’ the narrator tells us, rather than some fierce falling-out. For several years ‘the twin habit of that early time’ is enough to let the children come together easily on their subsequent meetings. But as time goes by their lives carry them in opposite directions, to the point where, although ‘still yearning in divorce’, they are unable to find their way back to that shared language which once held them together.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The fact that the brother-sister divided was a drama that Eliot treated twice, once in prose, then in poetry, suggests that it had deep roots in her own life. Certainly Mary Anne’s early attachment to Isaac is on record as greedy and rapacious. After her death, Isaac Evans recalled for John Cross that on his return from boarding-school for the holidays he was greeted with rapture by his little sister, who demanded an account of everything he had been doing.

(#litres_trial_promo) The scene is a charming one, but it hints at a distress which cannot be explained simply by sibling love. Behind the little girl’s urgent questioning there lurked a deep need to possess and control Isaac for fear he might abandon her. But it was already too late. When the boy was about nine he had acquired a pony and could no longer be bothered with his little sister. Mary Anne responded by plunging into a deep, intense grief, which was to echo down the years. ‘Very jealous in her affections and easily moved to smiles or tears,’ Cross explained to his readers, ‘she was of a nature capable of the keenest enjoyment and the keenest suffering, knowing “all the wealth and all the woe” of a pre-eminently exclusive disposition. She was affectionate, proud and sensitive in the highest degree.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Observing his wife’s temperament in later life, John Cross believed that the pony incident provided the key to understanding George Eliot’s personality. ‘In her moral development she showed, from the earliest years, the trait that was most marked in her all through life – namely, the absolute need of some one person who should be all in all to her, and to whom she should be all in all.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Later biographers have been quick to point out how this passage has become the cornerstone for a character reading of Eliot as needy, dependent and leaning heavily on male lovers and women friends for approval. Yet Eliot’s later comments on her own personality, together with the pattern of her subsequent relationships, suggest that Cross was doing no more than telling it how it was. The early withdrawal of her mother’s affection had left her with a vulnerability to rejection that would last a lifetime.

So when Mary Anne was sent away to boarding-school at the age of five, it was inevitable that she would take it hard. Even this was not the child’s first time away from home. For the previous two years she and Isaac had spent every day at a little dame school at the bottom of the drive. In her two-up-two-down cottage, Mrs Moore looked after a handful of local children and attempted to teach them their letters in an arrangement that went little beyond cheap baby-sitting. But now Mary Anne was to join Chrissey at Miss Lathom’s school three miles away in Attleborough, while Isaac was sent to a boys’ establishment in Coventry: hence the reference to ‘school divided us’ in the ‘Brother and Sister’ sonnets. Boarding-school was not unusual for farmers’ daughters, but five was an exceptionally early age to start. After only eleven years of marriage Christiana Evans had managed to clear Griff House of the five young people who were supposed to be living there.

(#litres_trial_promo)

School did not turn out to be an emotional second start for Mary Anne. Although she sometimes came home on Saturdays, and saw her nearby Aunt Evarard more often, she felt utterly abandoned. At the end of her life she told John Cross that her chief memory of Miss Lathom’s was of trying to push her way towards the fireplace through a semicircle of bigger girls. Faced with a wall of implacable backs, she resigned herself to living in a state of permanent chill. The scene stuck in her memory because it reinforced her feelings of being excluded from the warmth of her mother’s lap. No wonder, then, that her childhood nights were filled with dreadful dreams during which, reported Cross, ‘all her soul … [became] a quivering fear’.

(#litres_trial_promo) It was a terror which stayed with her throughout her life, edging into consciousness during those times when she was most stressed, depressed or alone. Even in late middle age she had not forgotten that churning sickness, working it brilliantly into the pathology of Gwendolen Harleth, the neurotic heroine of her last novel, Daniel Deronda.

Children who are separated from their parents often imagine that their bad behaviour is to blame. Mary Anne was no exception. She interpreted her banishment from Griff as a sign that she had been naughty and adopted the classic strategy of becoming very good. The older girls at Miss Lathom’s nicknamed her, with unconscious irony, ‘Little Mama’ and were careful not to upset her by messing up her clothes.

(#litres_trial_promo) The toddler who had once loved to play mud pies with Isaac grew into a grave child who found other little girls silly. When, at the age of nine or ten, she was asked why she was sitting on the sidelines at a party, she replied stiffly, ‘I don’t like to play with children; I like to talk to grown-up people.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

As part of her plunge into goodness, Mary Anne buried herself in books. Her half-sister Fanny, who had once worked as a governess, recalled for John Cross the surprising fact that the child had been initially slow to read, preferring to play out of doors with her brother. But once Isaac withdrew his companionship Mary Anne was left, like so many lonely children, to construct an imaginary world of her own. In 1839 she told her old schoolmistress Maria Lewis how as a little girl ‘I was constantly living in a world of my own creation, and was quite contented to have no companions that I might be left to my own musings and imagine scenes in which I was chief actress. Conceive what a character novels would give to these Utopias. I was early supplied with them by those who kindly sought to gratify my appetite for reading and of course I made use of the materials they supplied for building my castles in the air.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Quite who ‘supplied’ these novels is unclear. At the age of seven or so Mary Anne would have found very few books lying around Griff. The Evanses were literate but not literary and the little girl was obliged to read nursery standards like Aesop’s Fables and Pilgrim’s Progress over and over. Her father’s gift of a picture book, The Linnet’s Life, was special enough to make Mary Anne cherish it until the end of her life, handing it over to John Cross with a warm dedication.

(#litres_trial_promo) Joe Miller’s Jest Book was learned by heart and repeated ad nauseam to whoever would listen. In middle age Eliot recalled that an unnamed ‘old gentleman’ used to bring her reading material, but no more is known.

(#litres_trial_promo) For the girl who was to grow up to be the best-read woman of the century, it was an oddly unbookish start.

CHAPTER 2 (#ulink_c659cace-bed4-5405-a806-2ae895003939)

‘On Being Called a Saint’ (#ulink_c659cace-bed4-5405-a806-2ae895003939)

An Evangelical Girlhood 1828–40 (#ulink_c659cace-bed4-5405-a806-2ae895003939)

AT THE AGE of eight Mary Anne took a step towards a new world, urban and refined. In 1828 she followed Chrissey to school in Nuneaton. Miss Lathom’s had been only three miles from Griff and was attended by farmers’ daughters with thick Warwickshire tongues, broad butter-making hands and little hope of going much beyond the three Rs. The Elms, run by Mrs Wallington, was a different proposition altogether. The lady herself was a genteel, hard-up widow from Cork. She had followed one of the few options available to her by opening a school and advertising for boarders whom she taught alongside her own daughters. There were hundreds of these ‘ladies’ seminaries’ struggling to survive in the first half of the nineteenth century and most of them were dreadful. What marked out The Elms was its excellent teaching: by the time Mary Anne arrived, the school was reckoned to be one of the best in Nuneaton. Responsibility for the thirty pupils was shared between Mrs Wallington, her daughter Nancy, now twenty-five, and another Irishwoman, Maria Lewis, who was about twenty-eight.

The change of environment did nothing to help Mary Anne shed her shyness. Adults and children still steered clear, assuming they had nothing to offer the little girl whom they privately described as ‘uncanny’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Only the assistant governess Miss Lewis, with her ugly squint and her Irishness, recognised in Mary Anne something of her own isolation. Looking beyond the smooth, hard shell of perfection, she saw a deeply unhappy child ‘given to great bursts of weeping’. Within months of her arrival at Nuneaton Mary Anne had formed an attachment to Miss Lewis, which was to be the pivot of both women’s lives for the next ten years. Miss Lewis became ‘like an elder sister’ to the Evans girls, often staying at Griff during the holidays.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Mr and Mrs Evans were delighted with Mrs Wallington’s in general and Maria Lewis in particular. In their different ways they both set great store by their youngest girl getting an education. Shrewdly practical, Robert Evans had already schooled his eldest daughter, Fanny, to a standard that had enabled her to work as a governess to the Newdigates before her marriage to a prosperous farmer, Henry Houghton. Anticipating that the quiet, odd-looking Mary Anne might remain a spinster all her life, Evans was determined that she would not be reduced to relying on her brothers for support. A life as a governess was not, as Miss Lewis’s example was increasingly to show, either secure or cheerful. Still, it was the one bit of independence open to middle-class women and Robert Evans was determined that it should be Mary Anne’s if she needed it.

Christiana’s hopes for her daughter were altogether fancier.

(#litres_trial_promo) Like many a prosperous farmer’s wife, she expected a stint at boarding-school to soften her child’s rough corners and round out her flat vowels. A smattering of indifferent French and basic piano were the icing on the cake of an education designed to prepare the girl for marriage to a prosperous farmer or local professional man. In the case of young Chrissey the investment was soon to pay off handsomely. A few years after leaving Mrs Wallington’s she married a local doctor, the gentlemanly Edward Clarke. Still, husbands were a long way off for little Mary Anne. All Mrs Evans hoped for at this stage was that her odd little girl would become near enough a lady. Maria Lewis may not have been pretty, but her careful manners and measured diction were held up to Mary Anne – who still looked and sounded like a farm girl – as the model to which she should aspire.

It did no harm, either, that Miss Lewis was ‘serious’ in her religion, belonging to the Evangelical wing of the Church of England. From the end of the previous century the Evangelicals had worked to revitalise an Established Church that had become lethargic and indifferent to the needs of a changing social landscape. A population which was increasingly urban and mobile found nothing of relevance in the tepid rituals of weekly parish worship. During the 1760s and 1770s, the charismatic clergyman John Wesley had taken the Gospel out to the people, preaching with passion about a Saviour who might be personally and intimately known. For Wesley ritual, liturgy and the sacrament were less important than a first-hand knowledge of God’s word as revealed through the Bible and private prayer. When it came to deciding questions of right and wrong, the authority of the priest ceded to individual conscience. This made Methodism, as Wesley’s brand of Anglicanism became known, a particularly democratic faith. Mill workers, apothecaries and, until 1803, women, were all encouraged to preach the word of the Lord as and when the spirit moved them.

This challenge of Methodism, together with the continuing vitality of other dissenting sects such as the Baptists and the Independents, had forced the Established Church to put its house in order. The result was Evangelicalism – a brand of Anglicanism which held out the possibility of knowing Christ as a personal redeemer. In order to attain this state of grace an individual was to prepare her soul by renouncing all manner of leisure and pleasure. A constant diet of prayer, Bible study and self-scrutiny was required to stamp out temptation. Yet at the same time as renouncing the world, the Evangelical Anglican was to be busily present within it. Visiting the poor, leading prayer meetings and worrying about the state of other people’s souls were part of the programme by which the ‘serious’ Christian would reach heaven. Uninviting though this dour programme might seem, Evangelicalism swept right through the middle classes and even lapped the gentry during the first decades of the century. Its combination of self-consciousness, sentimentality and pious bustle went a long way to defining the temper of domestic and public life in early nineteenth-century England. In ‘Janet’s Repentance’, one of her first pieces of fiction, George Eliot showed how Evangelical Anglicanism had worked a little revolution in the petty hearts and minds of female Milby, a barely disguised Nuneaton: ‘Whatever might be the weaknesses of the ladies who pruned the luxuriance of their lace and ribbons, cut out garments for the poor, distributed tracts, quoted Scripture, and defined the true Gospel, they had learned this – that there was a divine work to be done in life, a rule of goodness higher than the opinion of their neighbours.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Even Robert Evans, not known for his susceptibility to passing trends, was affected by Evangelical fervour. During the late 1820s he went to hear the Revd John Jones give a series of passionate evening sermons in Nuneaton. Jones’s fundamentalist style was credited with inspiring a religious revival in Nuneaton and with provoking a reaction from more orthodox church members – events which Eliot portrayed in ‘Janet’s Repentance’. But Evans was too much of a conservative to do more than dip into this new moral and political force. As the Newdigates’ representative, he was expected to uphold the tradition of Broad Church Anglicanism. The parish church of Chilvers Coton stood at the heart of village life and it was here the Evanses came to be christened – as Mary Anne was a week after her birth – married and buried. Labourers, farmers and neighbouring artisans gathered every Sunday to affirm not so much that Christ was Risen but that the community endured.

At a time when many country people still could not read, it was the familiar cadences of the Prayer Book rather than the precise doctrine it conveyed which brought comfort, a point Eliot was to put into the mouth of the illiterate Dolly Winthrop as she urged the isolated weaver Silas Marner to attend Raveloe’s Christmas service: ‘If you was to … go to church, and see the holly and the yew, and hear the anthim, and then take the sacramen’, you’d be a deal the better, and you’d know which end you stood on, and you could put your trust i’ Them as knows better nor we do, seein’ you’d ha’ done what it lies on us all to do.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

While this was exactly the kind of hazy, casual observance which the Evangelical teenage Mary Anne abhorred, as a mature woman she came to value the way it strengthened social relations. Mr Ebdell, who had christened her, turns up in fiction as Mr Gilfil of ‘Mr Gilfil’s Love Story’. Schooled in his own suffering, Gilfil is a much-loved figure in the community, with an instinctive understanding of his parishioners’ needs. He pulls sugar plums out of his pockets for the village children and sends an old lady a flitch of bacon so that she will not have to kill her beloved pet pig. Yet when it comes to preaching, that key activity for a new generation of zealous church-goers, Mr Gilfil is sadly lacking: ‘He had a large heap of short sermons, rather yellow and worn at the edges, from which he took two every Sunday, securing perfect impartiality in the selection by taking them as they came, without reference to topics.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Gilfil begins a long line of theologically lax, but emotionally generous, Anglican clergy in Eliot’s fiction which includes Mr Irwine of Adam Bede and Mr Farebrother in Middlemarch. Irwine may hunt and Farebrother play cards, much to the horror of their dissenting and Evangelical neighbours, but both extend a charity and understanding to their fellow men which was to become the corner-stone of Eliot’s adult moral philosophy.

Ironically, it was just this kind of loving acceptance which drew Mary Anne away from her family’s middle-of-the-road Anglicanism towards the Evangelicalism of Miss Lewis. At nine years old she was hardly able to comprehend the doctrinal differences between the two ways of worship, but she was easily able to register that Maria Lewis gave her the kind of sustained attention which her own mother could not. If loving God was what it took to keep Miss Lewis loving her, Mary Anne was happy to oblige. With the insecure child’s eager need to please, she adopted her teacher’s serious piety with relish. After her death, when family and friends were busy offering commentaries on Eliot’s early influences, the idea grew that it was Maria Lewis’s indoctrination that had provoked Mary Anne into the flamboyant gesture of abandoning God at the age of twenty-two. In fact Miss Lewis’s observance, though rigorous, was always sweet and sentimental. She was hardly a hell-fire preacher, more a gentle woman who talked earnestly of God’s tender mercies. But she was not so gentle, however, that she was not prepared to push the blame in the direction where she believed it lay. Reminiscing after Eliot’s death, she maintained that it was Mary Anne’s next teachers, the Baptist Franklin sisters, who were to blame for the girl’s ‘fall into infidelity’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The Franklins, whose establishment was in the smartest part of Coventry, ran the best girls’ school in the Midlands. The ambitious curriculum and pious ambience attracted girls from as far away as New York. Too rarefied for Chrissey Evans, who returned home to Griff after her stint at Mrs Wallington’s, it was none the less the perfect place for twelve-year-old Mary Anne.

The Franklin sisters, Mary, thirty, and Rebecca, twenty-eight, were the daughters of a local Baptist minister who preached at a chapel in Cow Lane. Despite these stern-sounding origins, they were generally agreed to be the last word in female charm and culture. In what was becoming a classic pattern for the early nineteenth-century schoolmistress, Miss Rebecca had spent time in Paris perfecting her French before coming home to pass on her elegant accent to her pupils. Indeed, her combination of refinement and learning had given the younger Miss Franklin a personal reputation as one of the cleverest women in the county.

In such an exquisite atmosphere Mary Anne could hardly fail to flourish. Her French improved by leaps and bounds, and she won a copy of Pascal’s Pensées for her efforts, a triumph which still gave her pleasure at the very end of her life. Her English compositions were immaculate, read with admiration by Miss Franklin ‘who rarely found anything to correct’.