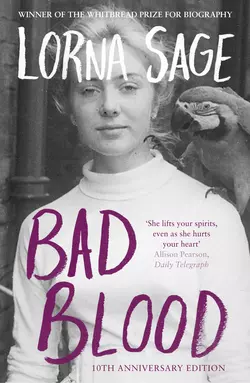

Bad Blood: A Memoir

Lorna Sage

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Биографии и мемуары

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 1151.20 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: From a childhood of gothic proportions in a vicarage on the Welsh borders, through adolescence, leaving herself teetering on the brink of the 1960′s, Lorna Sage vividly and wittily brings to life a vanished time and place and illuminates the lives of three generations of women.Lorna Sage’s memoir of childhood and adolescence is a brilliantly written bravura piece of work, which vividly and wickedly brings to life her eccentric family and somewhat bizarre upbringing in the small town of Hanmer, on the border between Wales and Shropshire.The period as well as the place is evoked with crystal clarity: from the 1940s, dominated for Lorna by her dissolute but charismatic vicar grandfather, through the 1950s, where the invention of fish fingers revolutionised the lives of housewives like Lorna’s mother, to the brink of the 1960s, where the community was shocked by Lorna’s pregnancy at 16, an event which her grandmother blamed on ‘the fiendish invention of sex’.Bad Blood is often extremely funny, and is at the same time a deeply intelligent insight by a unique literary stylist into the effect on three generations of women of their environment and their relationships.