God’s Fugitive

Andrew Taylor

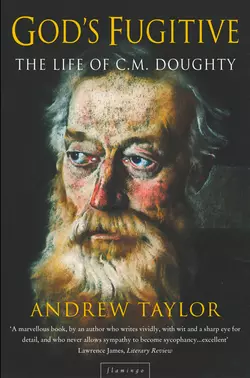

This edition does not include illustrations.A new biography of one of the most intrepid, romantic and fascinating of the great nineteenth-century travellers.Explorer, scholar, travel writer and poet, Charles Doughty was one of the great 19th-century adventurers. In the 1870s he spent two years wandering through Arabia, first with the Haj pilgrimage, then joining nomadic bands of Arabs. Unyielding in his independence of mind, the tall, red-bearded Doughty’s aggressive refusal to conceal his Christianity made his travels all the more dangerous: he was threatened with death several times, spurned, insulted and often beaten by angry mobs.The story of his archaeological investigations and his wide-ranging observations of Arabia and desert life were published in 1888 as the famous Arabia Deserta. Although feted by the literary establishment, Doughty often found himself at odds with the authorities, his work rejected and his genius (as he saw it) neglected. His long, impassioned and often paradoxical life make him one of the great British scholar-eccentrics.

GOD’S FUGITIVE

The Life of Charles Montagu Doughty

Andrew Taylor

DEDICATION (#ulink_91ce7d5f-dd3c-51a9-8db5-244e03a06bd6)

Looking in one direction,

this book is dedicated to

HARRY TAYLOR

and in the other

to

SAM, ABIGAIL AND REBECCA

EPIGRAPH (#ulink_1e3eebfb-b78b-5e50-a12e-50b85ddfe826)

The traveller must be himself in men’s eyes, a man worthy to live under the bent of God’s heaven, and were it without a religion; he is such who has a clean human heart and longsuffering under his bare shirt: it is enough, and though the way be full of harms, he may travel to the ends of the world.

Travels in Arabia Deserta, i, p. 56

CONTENTS

Cover (#udb631a4e-3e11-52a3-90d6-5ef3da8868cc)

Title Page (#u1a07a34b-1ac5-5d1c-ba48-b3b3e2971853)

Dedication (#ue342f9a1-1990-5670-90b6-13592ecb9839)

Epigraph (#u27274280-3848-56a4-ba83-f89629baab53)

Foreword (#u51ba865c-2ad9-557b-8ef3-16b5e4ff832d)

Map (#uf64263a8-3424-5b07-b612-4db8813e16b7)

Chapter One (#u14f0598c-b73f-580f-84e5-28580b57b418)

Chapter Two (#ua3c5ce91-8dcf-55e1-b11b-f340d68b61ae)

Chapter Three (#u8d611c69-3105-5a79-bd3c-381542813aa1)

Chapter Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Afterword (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

Bibliography (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Notes (#litres_trial_promo)

Author’s Note (#litres_trial_promo)

Praise (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

FOREWORD (#ulink_68f7fe59-b37f-5bdc-9a91-019a178c82f7)

Charles Montagu Doughty was the foremost Arabian explorer of his or any other age. His two years of wandering with the bedu through the oasis towns and deserts started a tradition of British exploration and discovery by travellers who acknowledged him as their master, and he returned to England to write one of the greatest and most original travel books.

He was that unlikely adventurer for his day, a man who would not kill – and yet he had strength and passion, and could face the threat of his own death without flinching. As a writer, he believed in his writing and in his vision when nobody else did; turning his back on exploration, he dedicated his life to poetry and struggled singlehandedly to change the direction of English literature. He lived through the greatest revolution in thought the world had ever seen, and spent a lifetime wrestling with his conscience over its consequences.

Among his admirers as an artist were George Bernard Shaw, who found Arabia Deserta inexhaustible. ‘You can open it and dip into it anywhere all the rest of your life,’ he declared.

(#litres_trial_promo) There were F. R. Leavis, Edwin Muir, Wyndham Lewis and, most ardent of all, T. E. Lawrence. Seven Pillars of Wisdom is, in its way, Lawrence’s own homage to Doughty.

And now he is virtually forgotten, his dense and idiosyncratic works valued by antiquarian booksellers and lovers of Arabia, but practically unknown to the readers of a simpler, less painstaking age. The achievement of his travels on foot and by camel seems overshadowed in the days of four-wheel-drive vehicles, helicopters, satellite navigation systems, supply-drops and commercial sponsorship. The great desert journeys are now all in the past. The tradition of Arabian exploration can never be recovered: it is as much a part of history today as the crossing of the Atlantic, or the search for the source of the Nile.

It was Wilfred Thesiger, another great Arabian explorer, who observed that there could never again be a camel-crossing of the desert like his own in the 1940s, or those of the explorers who went before him. ‘I was the last of the Arabian explorers, because afterwards, there were the cars,’ he said. ‘When I made my journeys in Arabia, there was no possibility of travelling in any other way than the way I went. If you could go in a car, it would turn the whole journey into a stunt.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Thesiger was the last of a line that included Harry St John Philby, father of the Russian spy and the dedicated servant of Ibn Saud, King of Arabia; there was Bertram Thomas, the civil servant who saved up his holidays for his desert expeditions, and became the first European to cross the Empty Quarter; and Gertrude Bell, who travelled to Arabia in the shadow of a disastrous love affair,

(#litres_trial_promo) and demanded that the rulers of Hail treat her like the lady she was and cash her a cheque for £200.

There were the Blunts, Wilfrid and Lady Anne, searching for a romantic Orient which never existed outside the salons of London and Paris; and of course, T. E. Lawrence himself, Lawrence of Arabia, who united the warring tribes just long enough to drive out the Turks and change the face of the Middle East for ever. All of them were passionate, even obsessive, about the desert – and above and before them all stood Charles Montagu Doughty.

The tradition had lasted less than seventy years. Before, there had been adventurers, explorers like Sir Richard Burton or William Gifford Palgrave, who disguised themselves and slipped through Arabia like thieves or spies; after Doughty, with his proud refusal to dissemble, things were never the same again.

Doughty came to Arabia almost by accident, at the end of six years’ wandering through Europe and the Middle East. Initially, he intended to investigate reports of a lost city like Petra, close by the pilgrim road to Mecca; but by the time he sailed away from Jedda two years later, he had dug more deeply into Arabia, lived more closely with the wandering bedu, than any explorer before or since. Thesiger was to collect photographs, Philby tiptoed after tiny birds, reptiles and mammals like some ghastly Angel of Death adding to his collection, and all of them gathered fossils, rocks and ‘specimens’ for the museums at home – but Doughty’s vision embraced an entire civilization.

Everything he did was on a grand scale, and the book he eventually wrote about his travels, which appeared some nine years later, covered nearly 1,200 pages. It was written in a style that mingled Elizabethan and Arabian, the rhythms of the Bible with the precision of a scientific text. And apart from being a staggering work of literary ambition, Travels in Arabia Deserta was, for many of the explorers who followed him, a first introduction to the Arab world.

‘We were in totally different parts of Arabia, so he couldn’t give me any information about the country itself, but he could give me a feel for the bedu and their way of life,’ said Thesiger, whose own book, Arabian Sands, is itself considered a classic.

(#litres_trial_promo) ‘It was a massive undertaking. Thomas’s books I don’t think are worth reading; Philby’s are too technical, and I don’t find them readable, but there is more in Doughty about the Arabs and their way of life than anywhere else.’

Doughty claimed later that his travelling was no more than a brief distraction in a life dedicated to poetry. But Arabia stayed with him until the day he died – as indeed it did with all the explorers. His obsessions, though, were bigger, more ambitious, than theirs – his book delving at the same time into the soul of a civilization and into the soul of a single tortured human being.

He was born into the maelstrom of the most wide-ranging revolution in the entire history of western thought, and he shared fully in an intellectual upheaval that still reverberates. Scientific disputes are usually remote, abstruse – the bitter argument centuries before, over whether the sun or the earth was at the centre of the universe, had been carried on largely among a small group of committed experts. The vast mass of the people were as unaffected as they were uncomprehending. But the twin shocks of the revolution which hit the mid nineteenth century were to shake the confident world-view of virtually every single thinking person in the western world for decades to come.

Through the early years of the century generations of comfortable certainty were being chipped away by the questing hammers of the new geologists. Not only was the world vastly older than the theologians suggested, the scientists claimed, but the natural forces that had shaped it were still at work. Two books took the argument forward – first Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology, and then Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species.

Each was the synthesis of a dispute which had been simmering for decades, but they shifted the ground of the debate irreversibly. First the earth, and now mankind itself, was toppled from its position as the unchanging Creation of a loving God. The reassuring vision of man in the image of his Maker was altered for ever. It was by going to study the work of wind, rain, volcanoes and glaciers, peering through microscopes rather than poring over religious books, that knowledge could be won.

Doughty followed both courses. He was born into a family which, through its generations of conservative Anglican religious ministry and its respect for history and tradition, was likely to be shaken to the core by the revolution. Many people in a similar position struggled to maintain their equanimity by ignoring the scientific arguments, others by relinquishing their religious faith. Doughty, picking over fossils in the Suffolk clay, travelling to Cambridge University to study the dangerous new discipline of Natural Science, struggling with his ice-axe and notebooks over the glaciers of Norway, yet still maintaining his passionate religious sense, was caught in a lifelong dilemma.

After Cambridge, he abandoned science to turn to poetry, abandoned the new fascination with field-study to return to the library. Once again, he was delving back into the past, into the foundations and origins this time of language and literature, a self-taught philologist, linguist and anthropologist. When he set off on his travels, his copies of Chaucer, Spenser and other early English writers in his bags, it was with a closely drawn and wide-ranging intellectual map which could guide his researches in geography, geology, biology, history, anthropology and language.

But he had, too, the deeply introspective determination of a writer and a poet. His wanderings, as far as we can tell, seem to have been largely serendipitous: Doughty was blown by whatever wind took him, first around Europe, then through the Middle East and Sinai, and finally south with the Hadj caravan towards Mecca.

When he returned, it was to a life of unremitting study and contemplation as he embarked first on the story of his travels, and then on a series of epic poems that drew on his experiences, his researches and his uncompromising belief in the corruption and decadence of the English language. He saw himself as a patriot, trying to turn back the clock to a time when language and literature were fresh and pure. He failed, as people who reach back into history always do; but the attempt dominated his life, and the poetry that it created does not deserve merely to be forgotten.

In many ways, he was a man of his times: he felt a Victorian’s distaste for industrialization; he joined in the brutal, blustering patriotism of the First World War years; even his fascination with language, with the words and expressions of another age, was shared by other scholars and poets of the period. But, a sort of intellectual Howard Hughes, he read nothing of their work, and virtually nothing of other contemporary writing: the names of the leading poets and writers of his day were completely foreign to him, and he shied nervously away from the onrush of the twentieth century.

He was indeed, in the phrase he was to use many years later, ‘God’s Fugitive’.

MAP (#ulink_f4bb5f4f-4cc1-57d5-bd2b-622ed52b3324)

Chapter One (#ulink_c9dd2b5e-6b19-5691-bdbe-1ed50b0ce210)

There is nothing in the nature of a biography; nor could there, that I can see, be any utility in it. I was born in ’43 and left an orphan when a little child. I am now rather an invalid …

Letter to S. C. Cockerell, Christmas Day 1918

The solid, square flint tower of St Mary’s Church, Martlesham, is almost hidden among the Suffolk trees. It stands a couple of miles away from the modern village – easy to miss for the casual visitor.

Inside are the haphazard treasures of thousands of English country churches: a fifteenth-century wall painting of St Christopher, lovingly preserved; an ancient family pew recessed into a wall of the chancel, and now used to store cleaning materials; a stone font from the fifteenth century and a carved oak pulpit from the seventeenth; an ancient chest, and a few pieces of medieval stained glass gathered into a single panel. And along the walls, the carved memorials that say everything and nothing about the long-dead members of a local family – in this case, the Doughtys.

There are George Doughty, died 1798, and his wife Ann; their son Chester, who died in 1802; Major Ernest Christie Doughty, DSO, of the Suffolk Regiment, who died in 1928; his grandfather, Frederic Ernest, Rector of Martlesham for nearly thirty years. Outside, more Doughtys are at rest in the graveyard: Rear-Admiral Frederick Proby Doughty, who died in 1892, and his wife, the former Mary Arnold, with their child Beatrice May, lie there among their relatives.

Of Charles Montagu Doughty, for whom as a child Martlesham was closer to being a home than anywhere else, there is nothing: his memorial is far away, in a London crematorium. And yet the atmosphere of the simple little church, its unimpeachable, unassuming Englishness and its dignified reserve, reflect one facet of his character. As in churches all over the country, it is the list as a whole, rather than the individual names, which tells the story; of specific characters, particular lives, the memorials are all but silent. There are names, dates, an occasional mention of a life’s work, but it is the tradition, the history, not the individual, which counts.

And that, without the slightest doubt, is what Charles Doughty would have thought the proper attitude.

He always backed away from curiosity about his biography or his early life – and indeed, many Victorian children must have shared his experience of childhood as time spent in a foreign and not particularly friendly country. Even for the offspring of a family with lands, traditions and inheritances on each side going back for generations, it could be an unpredictable and precarious existence.

Doughty was born into a world of privilege and high expectations. His father, also Charles Montagu, was a clergyman, the squire of Theberton in Suffolk, and owner of family estates and properties all over the county – but it was only a few months after his birth on 19 August 1843 that the young Charles Doughty suffered the first of a series of devastating blows. His mother, Frederica, never recovered from the strain of childbirth and, at less than a year old, Doughty was motherless. He himself had not been expected to survive. ‘It is a long time since I came into the world, and so obviously a dying infant life, that I was christened by my own father almost immediately,’ he said later.

(#litres_trial_promo)

But it was the mother, and not the child, who died, and for the rest of his life, the few people who talked to Doughty about his childhood commented on his abiding sense of bereavement. Within a year of his own marriage forty-three years later came a mirror-image of the tragedy, with his own stillborn first child carried off to the churchyard while his invalid wife lay and struggled back to health. Small wonder that later, as he gathered together in his painstaking fashion thousands of word-associations and jottings for use in his writing, among the first under the Latin heading ‘Mater’ would be ‘mother’s yearning’, ‘longing’, ‘smiling tears’ and ‘yearning love’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

One of the first and most lasting lessons for the young Charles Doughty was that love was something that was brutally wrenched away – an ache, not a consolation.

At the end of his life, then, his writing drew not just on six decades of dedicated study, not just on the travels through Arabia which had been his formative experience, but also, crucially, upon the sense of loss which had surrounded his earliest memories. The theme repeatedly comes back to haunt him – in his last poem, Mansoul, for instance, he describes how he faced his own ‘private grief’ on his journey around the underworld. ‘Death cannot dim thy vision,’ he declares at his mother’s grave.

Long cold be those dead lips, that word ne’er spake

Unworth, unsooth; those dying lips, that kissed,

Once kisst (thy nature’s painful travail past)

This last new-born on thy dear breast, alas! …

Mother of my life’s breath, I living lift

O’er thee, these prayer-knit hands …

(#litres_trial_promo)

And the grief runs deeper than that simple, almost formalized Victorian sentimentality. In The Dawn in Britain, the story is told of the baby Cusmon, who was abandoned by his mother, the immortal nymph Agygia, but watched over by her throughout his life. Eventually, after his hundredth birthday, they are reunited at his death.

She stooped, and dearly kissed

That bowed down, aged man, and long embraced …

(#litres_trial_promo)

When he wrote that, Doughty himself was in his seventies. He is a child again, his lost mother restored, and a lifelong sense of bereavement finds its devoutly longed-for but hollow and insubstantial resolution in an old man’s dream. It is significant that he angrily denied suggestions in reviews that this was his own version of an ancient tale: ‘There is no such myth, and there is no such version,’ he declared. ‘The original is that in The Dawn in Britain itself.’

(#litres_trial_promo) The story clearly remained important to him: he could mourn the loss of his mother, but emotionally, he could never quite accept it.

Materially, though, both Doughty and his elder brother Henry were well provided for, their place in society apparently fixed by generations of affluence and family tradition. On both sides, the family were well-to-do, landowning gentry: the census return for Theberton for 1841, just two years before Charles’s birth and Frederica’s death, shows the Doughtys with the three-month-old Henry and five adult servants. It was a comfortable life in the sheltered and undemanding tradition of the prosperous Church of England.

The Doughtys of Suffolk had built up extensive lands over the centuries, and occupied a succession of livings; Frederica’s relatives, the Hothams of East Yorkshire, had produced six admirals, three generals, a bishop, a judge and a colonial governor. It was a family that drank in unquestioning patriotism and the peculiarly restrained devotion of the Established Church with its mother’s milk – the sort of family on which the empire had relied for generations.

But it seems, too, to have been a family where the idea of pride and duty replaced any open show of affection. Doughty’s cousin, the Rear-Admiral Frederick Proby Doughty who now lies in Martlesham churchyard, wrote a journal in which he recorded his memories of the various members of his family – and on the Doughtys’ side at least, there does not seem to have been much obvious emotional closeness. ‘We were badly off as children in the matter of relatives – no grandfathers or grandmothers, or relatives that were disposed to do the correct and orthodox “uncle and aunt” business.’

(#litres_trial_promo) The family would perhaps have been scandalized not to be considered ‘correct and orthodox’, but the message is clear. Of his uncle, the late father of young Charles and Henry, he reminisced: ‘I do not recall much connected with him, except on one occasion when walking with my father at Martlesham. I suppose I was rather busy with my tongue – he said to my father, “Why do you allow that boy to go on chattering? Box his ears …!”’

And there was more for the young Charles Doughty to contend with than the occasional bad temper of a crusty old Victorian clergy man. For all his wealth, Doughty’s father was stretching himself financially, with an ambitious programme of ostentatious building works at Theberton Hall. It seems to have been something of a family failing – only a few years later, after a similar programme of grandiose ‘improvements’, Doughty’s uncle, Frederick Goodwin Doughty, was forced to put his own home of Martlesham Hall, a few miles away, up for sale.

The boys, no doubt, were too young to be aware of the growing problems, but the atmosphere at Theberton Hall cannot have been a happy one. Their father seems to have been shattered by the untimely death of his ‘late dear wife’, who was only thirty-five when she died. No doubt the young Charles was not the only one to feel a sense of loss and bereavement: his father’s own health was not strong, and on 6 April 1850 he put his affairs in order, writing a new will, with an instruction that he should be buried next to Frederica in Theberton Church. Less than three weeks later he was dead, at the age of fifty-two, the doctors giving the cause of death as ‘Exhausted nature following a severe bilious attack’. The two boys were now orphans.

Childhood, it must have seemed, was little more than a harsh preparation for a life of loneliness. Theberton Hall was shut up, and within a few weeks the auctioneers moved in. At 11 a.m. on 28 August they started their sale with Lot 1 – two brown bread pans, a strainer and three baking pans – and over the next four days sold off the entire contents of the house. The Reverend Doughty’s fine wine cellar and his extensive library were split up and put under the hammer; so were his ‘town-built chariot’ and his single-horse phaeton. Even more distressing for the two boys, everything in their nursery was sold – brass mounted fender, fire-irons and pictures off the wall. It was a common practice in the mid nineteenth century to sell off the belongings of the dead – but that made it no less heart-rending for the young boys, who had to see what had once been their home broken up and carried off by strangers.

But if the seeds of Doughty’s later emotional detachment and determined self-sufficiency can be seen in these bleak years of bereavement, there were other members of his immediate family with a brisker, no-nonsense attitude to death. Frederick Proby Doughty’s detached account of his uncle’s financial problems and death seems brutal today, but it probably reflects the severely practical attitude of the family at large.

He had commenced great alterations to Theberton Hall, building enormous stablings, altering the entrance, building a picture gallery, and other expensive undertakings far beyond his means, and out of character with such an estate. Luckily he died, leaving his sons Henry and Charles … a long minority before them to recover and pull through the expenses and debts their father had incurred.

In fact, if his will is anything to go by, Charles Doughty senior still had plenty to leave his two sons. For Henry, there were several houses and estates spread over various parishes in Suffolk – among them Theberton Hall itself.

Charles, as the younger son, was less generously provided for, but he still inherited three farms, all his father’s government funds and securities, and an unspecified amount of cash, annuities and other investments which derived originally from the Hotham family. His guardian was to be his uncle, Frederick Doughty of Martlesham, father of the journal-keeping Frederick Proby Doughty – but the journal gives little cause to suggest that the move to Martlesham brought any fresh lightheartedness or fun into the little boy’s life. The elderly admiral recalled later: ‘I never remember a guest staying in the house, and but one or two dinner parties; and visiting friends were few and far distant.’ Of his mother – the woman who was to share the job of bringing up the young Charles Doughty – he wrote: ‘I fancy she was very delicate – lived mostly when at home stretched out on a sofa. I don’t remember her ever entering into any games or sports with us …’ She had a good education and spoke several languages, but she wasn’t known for her friendliness. ‘Extreme amiability’, her son noted carefully, ‘was never one of my mother’s vices or virtues.’

Neither Frederick Doughty nor his wife was going to waste much time or affection on their new charge. Within months of his father’s death young Charles was packed off to school at Laleham, on the Thames, to come home only for those parts of the holidays for which they could not find another willing relative or friend to take on the burden of his keep.

For Doughty’s new guardian was going through his own financial problems, and for much the same reasons that his dead brother had done. He had been pouring money into the rebuilding of Martlesham Hall for nearly ten years when his nephew arrived – perhaps the two brothers were competing in the splendour of their ambitions. If so, they paid a heavy price: only death prevented Charles from crippling himself and his two small sons with debt, while Frederick was eventually forced to sell the Hall which was his pride and joy. ‘It was a terrible wrench to all his feelings: the building of the Hall in the Elizabethan style had been the pleasure and the hobby of his life. For years after the sale, the place was never named, or mention made of it,’ Frederick’s son dutifully recorded. By the time Martlesham was sold, Charles Doughty would have been some ten years old – old enough to sense and recognize the fresh misery that the family was going through. Perhaps there is even a hint in his cousin’s journal that the young Charles might have been made to feel some responsibility for the disaster, despite the fact that his father’s will had carefully provided for his upkeep and maintenance.

The sale of the Hall and the estate around it I fancy became inevitable in spite of a hard struggle on the part of my father to make ends meet. The growing up of children and the increasing expense of education in addition to the above sealed its fate … The sale was, I have heard on all sides, a terrible blow to my father.

Laleham, with swimming in the river Thames and cricket in a nearby meadow, seemed initially to be an ideal choice of school for a boy who was used to life in the country, and who was already, not surprisingly, showing signs of being shy and withdrawn. The Revd John Buckland had made his career as headmaster there – he had come to Laleham thirty years before with Dr Thomas Arnold, and the two young schoolmasters had set up their own establishments, Arnold preparing older boys for university, and Buckland building up one of the country’s first preparatory schools.

Arnold, of course, had moved on to greater things at Rugby School after ten years, but Buckland stayed behind. By the time he retired, three years after Charles Doughty arrived, The Times commented that he was running ‘a large and flourishing private school’. The connection with Arnold was still close, and a letter from his son, the poet Matthew Arnold, about a visit in 1848 to the man he still called Uncle Buckland gives an idyllic picture of the establishment as it then was. ‘In the afternoon I went to Penton Hook with Uncle Buckland, Fan, and Martha, and all the school following behind, as I used to follow along the same river bank eighteen years ago. It changes less than any place I ever go to.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

But the memories of a man in his mid twenties, however little the place itself seemed to have changed, were more pleasant than the day-to-day reality for the thirty or so small boys at the school. Even Arnold, in a less lyrical mood, described it as ‘a really bad and injurious school’, and grumbled about ‘that detestable gravel playground’,

(#litres_trial_promo) while ‘Uncle Buckland’ gloried in a reputation for strict discipline that was anything but avuncular.

One former pupil – who went on to become a bishop in New Zealand

(#litres_trial_promo) – recalled how he was summoned from breakfast by Buckland to be asked what religion he was. ‘Christian’, apparently, was not a good enough answer, and when the boy stammered nervously that he did not know ‘what sort of Christian’ he was, he was sent off to spend the day locked in the cellar. Eight hours later ‘Uncle Buckland’ unlocked the door, and asked him again – and still the panic-stricken boy had no reply for him. ‘The headmaster replied at last, “Sir, you are a Protestant,” and knocked him down. Hardly a method to encourage Protestantism, the bishop thought, looking back …’

And not one either to encourage a happy atmosphere of learning and scholarship. Doughty was experiencing early the violent religious bigotry that he would meet again in the deserts of Arabia: it is hardly surprising, even though the victim of that attack made his career in the Church, that many of Buckland’s pupils, like Doughty, adopted an ambiguous attitude to the established religion as they grew up.

But Buckland’s no-nonsense attitude would have raised few eyebrows in the mid nineteenth century. The only complaint about the school that Doughty himself made as he grew older was a much less serious one, his wife wrote in a letter, years afterwards. ‘He was six years old, and much resented being made to get out of bed to show visitors what a tall boy he was.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

His guardians positively welcomed the strictness of the regime, and around the time that Buckland retired they moved their young charge away from Laleham and off to the nearby school at Elstree. It was a move from one strict disciplinarian to another, even more overbearing one.

Once again, it was a quiet, country establishment, in a seventeenth-century mansion at the top of a hill, with a Spanish chestnut tree said to be over a thousand years old outside the front door – the tree, its huge, contorted branches now severely pruned, still stands outside what is now a nursing home. The curriculum was mainly classics, with a few periods a week of mathematics, occasional science lessons, and desultory French from a visiting Frenchman. There was a gravel yard with a fives court, football from time to time, and cricket on the field in front of the house.

Doughty had a slight stammer, which was to stay with him throughout his youth. He was tall for his age, but slim and unassuming, although his contemporaries were already finding out that his apparent frailty concealed a deceptive strength and determination. Two of them who met his wife shortly before her marriage told her that, thin and delicate as he was, he had fought and beaten all of them.

(#litres_trial_promo) In another incident, presumably during one of the cricket sessions across the road from the School House, he was hit in the face by the ball. His wife told the story after he died: ‘No notice was taken at the time, and he said nothing (so like him!) but the cheekbone was smashed, which showed all his life.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

On another occasion, he had told her about competing with a group of boys to see who could stand longest on one leg. He was left standing there when they all went off to church – and he was still there on one leg when they came back.

It is probably as well that the Revd Leopold Bernays knew nothing about one of his young charges spending his time in such fruitless vanity when he should have been at prayer. Letters about the headmaster ‘do not give the impression of a genial or popular man’, notes the Elstree School history coyly – and, judging from the sermons that he published during his life, he must have been an awe-inspiring, even terrifying, figure for a young boy. ‘Nothing can make life sweet and happy but a constant preparation for death,’ was one of his more jovial bons mots;

(#litres_trial_promo) in another sermon he stormed at the wide-eyed ranks of small boys before him: ‘If we could see the very jaws of hell open to receive us, and ourselves hastening madly down the road, with nothing to arrest our career – how we should pray!’ Again, he pondered on how ‘one week passed amongst you pains me, with its long catalogue of idleness and carelessness, of disobedience and wilfulness, of harsh and profligate words …’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Most of these idle, disobedient and wilful pupils were destined for Harrow School, but Doughty’s ambition, even at his young age, was to follow the tradition of his mother’s family and enter the navy. His brother Henry had already been at sea for two years, and Charles wanted nothing more than to follow in his footsteps. Some time around 1856, a boy of around thirteen, he was uprooted from school and friends for a second time, and bundled off to Portsmouth, where he was to be prepared for his navy examination at a school called Beach House.

Henry was to leave the navy later for a career as a lawyer. But his future was mapped out for him, as the future squire of Theberton; as the younger son, Charles would have to fend for himself. Life as a naval officer must have seemed to combine excitement with the sense of patriotic duty that had been bred in the young boy’s bones – and, too, with the severely practical need for a career.

It was not only the example of his mother’s family that had inspired the two Doughty boys with the idea of serving in the navy – for all their seniority, the much-boasted six Hotham admirals would have seemed remote to a small boy, an inspiration to duty rather than passion. But there were other family stories to whet their appetites – most particularly, those of their cousin, the journal-writing Frederick Proby Doughty of Martlesham.

He was only a few years older than they were and had already sailed to Canada, South America, Easter Island and even off to the Baltic to fight against the Russians. Here was a hero with whom they could identify. Though they saw him rarely because he had been away at sea since passing his exams some ten years before, they must have been well aware of his stories and adventures. They did, after all, spend at least some of their holidays with his father, their guardian, Frederick Doughty.

Much of the time, though, the boys were farmed out to a succession of relatives. Theberton Hall, the house where they had been born, and one of the few constant elements in a life that had so far been a series of uprootings and removals, remained locked up. A caretaker and his family lived there, among the gloomy, half-finished building works that were their father’s memorial, to look after it until Henry should come of age to take over his inheritance.

Sometimes they stayed with the Newsons, a family who had farmed on the estate for generations, sometimes with their father’s sister Harriet Betts and her family, who lived nearby in Suffolk – ‘a thoroughly scheming, worldly person’, if Frederick Proby Doughty is to be believed – and sometimes, too, with their mother’s relatives, the Hothams, who also lived in Suffolk.

Certainly there were happy memories among all the travelling between relatives’ houses: in his old age Doughty recalled fondly ‘the noble castle ruins and proud church monuments’ of Framlingham. ‘It is to me one of the memories of childhood, when my mother’s father was Rector of Dennington, two miles further on,’ he wrote.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Frederick Proby Doughty has left details of one family holiday which he spent with his parents and his cousin and future wife Mary Arnold – with the fourteen-year-old ‘Charlie’ Doughty acting as unofficial chaperon for the undeclared lovers. Young Charlie at that time was at Beach House and his cousin – who had been at home for several months since his latest voyage – was deputed to collect him from Portsmouth and escort him to North Wales. The long coach journey through Bath and Bristol to Llangollen gave plenty of time for the young man’s tales of life at sea – and his teenage cousin would have been an avid listener.

For the two young lovers, it was an ideal family party. The older Doughtys left them to their own devices – they, after all, wanted a quiet, dignified time in a respectable hotel, rather than long walks in the country. And even when their young cousin tagged along, he had better things to do than interfere. ‘Charlie was ever alive to the chance of catching a trout … Better elements for leaving Mary and myself to our own devices could not have been collected together,’ says the journal gleefully.

The young people spent most of their time rambling over the hills – again, little sign of Doughty’s supposed frailness. ‘Charlie and myself did Beddgelert, and passed over the top down to the pass of Llanberis, and so back to Beddgelert – a walk of over thirty miles. We had been rewarded by a good view from the top of Snowdon.’ But if the days were long and energetic, the journal also gives a telling glimpse of what must have seemed to the young people to be equally lengthy but tedious evenings. ‘As a family, we are not a festive lot, and, left to ourselves, the sun might travel from its rising to its setting without one observation being made … The more genial spirit of my father, as I remember him, seemed by the habitual staidness of his life to have almost died out.’

Frederick’s innocent suggestion of a quiet game of cards caused an outburst from his mother: it showed a vicious spirit, and a tendency towards gambling, she stormed. It’s a hint of what life at Martlesham must have been like for much of the time – these, after all, were the people who thought the Revd Leopold Bernays a suitable moral guide for their young charge.

As a whole, though, the month in Wales passed happily – the best times, even at this young age, were spent away from wherever happened to be ‘home’ at the moment. Frederick Doughty recalled it years later as ‘a very jolly cruise’, and ‘Charlie’ clearly enjoyed spending time with a cousin who seemed, at twenty-two, to have such a wide and enviable experience of the naval life on which he was himself about to embark.

From Llangollen, at the end of the holiday, he returned to Beach House, and his preparation for his naval examinations – and to a shock and disappointment that was to remain with him all his life. When he was finally entered for the medical test that formed part of the entrance requirement, he was turned down by the examiners, either because of his slight speech impediment, or because his general health was thought not to be strong enough for the rigours of life at sea. More than sixty years later the memory still hurt him. ‘My career was to have been in the navy, had I not been regarded at the Medical Examination as not sufficiently robust for the service. My object in life since, as a private person, has been to serve my country so far as my opportunities might enable me.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

His rejection seems to have shocked the staff at Beach House as well. During the following year his maternal aunt, Miss Amelia Hotham of Tunbridge Wells, was assured that he was ‘the very best boy that we have met with’. Even allowing for a degree of tact in dealing with pupils’ close relatives, it is a verdict that suggests that Doughty’s teachers, at least, believed that the navy had missed a good candidate.

Their sympathy, however, must have been of very little consolation to a boy who had seen his ambition snatched away from him, whose elder brother had by now started a career at sea, and who was still all too conscious of his cousin’s steady progress in the service. It must have been hard, too, to be surrounded by his contemporaries, who would have been looking forward to their own careers as naval officers. A few months after the examination board’s decision he was taken out of the school, and started a course of study with a private tutor.

Clearly, he and his family had decided that if he could not follow one family tradition by joining the navy, he should follow another by going up to his father’s old college at Cambridge, Gonville and Caius. Preparation for that involved a degree of formal, structured study, and the records of King’s College, London, show the young Doughty lodging in a suitably respectable boarding house in Notting Hill,

(#litres_trial_promo) while he followed a mathematics evening course at the college.

But Doughty remained the prosperous son of a prosperous family, and much of the time between Beach House and Cambridge, his widow said later, was passed in travelling with his tutor through France and Belgium. They were travels that not only gave him his first taste of foreign languages outside the classroom, but also established the connection in his mind between study and the wandering life. Perhaps it was on the roads of northern France that much of the character of the scholar gypsy was formed.

More crucially, though, he returned to the chalk countryside of his home in Suffolk. During his school holidays at his uncle’s home in Martlesham or on the Newsons’ farm in Theberton, he had amused himself by digging for fossils and stone artefacts – a very fashionable pastime as the revelations of Charles Darwin about evolution were echoing around the world. Now Doughty started geological and archaeological studies in earnest around the village of Hoxne – ‘working a good deal with the microscope’, he told a correspondent later.

(#litres_trial_promo) In 1862, while still only nineteen years old, he submitted a paper to the Cambridge meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science on Flint Implements from Hoxne.

It was an ideal place to start. More than sixty years earlier the little Suffolk village, recognized today as one of the most important archaeological sites in Europe, had seen the discovery of some of the first stone axes found in Britain; in 1860 those discoveries were being linked with others made in France, to revolutionize the accepted view of prehistory. Humanity, the researchers demonstrated, had a much longer pedigree than anyone had believed.

(#litres_trial_promo)

It was a controversial, even revolutionary subject, and the decision Doughty made now reflected the self-reliance that had been forced on him by a bleak and lonely childhood, the toughness that the disappointment at Beach House had given him, and the straightforward determination that was already a part of his character. Practically everyone who came into contact with Doughty throughout his life commented on his diffidence – his friends were later to refer to him dismissively as a ‘shy dreamer’

(#litres_trial_promo) – but his arrival at Cambridge University showed that his reserved manner hid a rocky determination.

The Admissions Book in the archives of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, shows ‘Carolus Montagu Doughty’ accepted as a new member of the college on 30 September 1861. It was the college that his father and his grandfather had attended before him, but Doughty was determined not simply to follow in their footsteps. It was only two years since Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species had outraged the certainties of the Established Church with which Doughty had such close family links, and the study of science was still considered barely respectable in the university – and yet it was on the newfangled Natural Science tripos that he decided to concentrate.

His expeditions and diggings in Suffolk had already made him a dedicated geologist and collector of fossils, and he was determined to develop this interest from the start of his Cambridge career. It cannot have been a welcome ambition in a family as steeped as his in the reassuring traditions of Church and countryside.

It is Darwin who is chiefly remembered today as the man who shivered the comfortable theology of the Church of England to its foundations, but more than twenty-five years before On the Origin of Species appeared, Charles Lyell had dealt another blow with his Principles of Geology. It is hard to overstate the impact of the new science on the intellectual life of the time: Lyell’s contention that the earth was still changing and developing after hundreds of thousands of years had broken upon a world where eminent churchmen referred to ancient texts and confidently named 23 October 4004 BC as the precise date of Creation, while Darwin’s challenge to the story of Adam and Eve seemed to strike at the very basis of Christianity.

People struggled to hold onto their faith, and John Ruskin spoke for many of them when he declared, ‘If only the geologists would let me alone, I could do very well – but those dreadful hammers! I hear the clink of them at the end of every cadence of the Bible verses!’

(#litres_trial_promo) And the geologists themselves felt the draught of their studies upon their own beliefs. In a letter to Darwin, written in the mid 1860s, Lyell said wistfully: ‘I had been forced to give up my old faith without thoroughly seeing my way to a new one.’

(#litres_trial_promo) It was a common dilemma, and one which struck particularly hard at a young man like Doughty, passionate in his sense of tradition, yet unswerving in his search for truth.

Doughty had grown up with the rhythms of the Authorized Version echoing in his mind, and his whole instinct was to look back, not forward, for reassurance – but it was in that dreadful clink of the geologist’s hammer that he found inspiration. The whole discipline of geology, and the study of natural science itself, was unsettling, revolutionary, and frequently in direct conflict with the teaching of the Church – but it fascinated Doughty.

As a child, he had been gripped by the idea of the navy and his family tradition of military service. Later, it would be Arabia, and then the story of the Roman conquest of Britain. Doughty would continue to focus his attention upon some particular subject and, over a period of years, would immerse himself in it, teasing out every last detail, before passing on, his attitude to life altered and enriched by the experience, to some new study. Time was not significant – the writing alone of The Dawn in Britain took almost ten years of his life, and the research beforehand at least as long again – but while the fascination was upon him, his obsession would be virtually total.

The shy and diffident young Doughty seems to have made little impression in his early days at Cambridge. He found it hard to make friends with his fellow students – and at the same time he showed no sign of incipient brilliance as a scholar. The Caius examination records show him stumbling uneasily through his first examinations – 27th out of 32 in Classics, 19th of 34 in Theology and, despite his efforts at King’s College, London, 30th of 35 in Mathematics. But from the very start there was no doubt where his greatest interest lay.

(#litres_trial_promo)

He clearly enjoyed passing on his geological passion: he dragged one of the junior fellows of the college, Henry Thomas Francis, off to inspect the Kimmeridge clay at Ely and the gravel pits in Barnwell (‘When’, Francis recalled wryly later, ‘I caught a severe cold …’). Another friendship was with the future Professor John Buckley Bradbury, with whom he shared a staircase in Caius overlooking Trinity Street – Doughty’s old room, which has since been redeveloped, was above the college library where, decades later, the main collection of his private books and papers was held. The two men used to take long walks into the country, visiting the chalk pits and coprolite diggings just outside Cambridge.

Another contemporary at Cambridge, Edwin Ray Lankester, later to become a Fellow of the Royal Society and one of the country’s leading zoologists, also recalled Doughty’s application and enthusiasm. For a time Doughty had rooms opposite his, and Lankester remembered him, three years his senior, as ‘rather shy and quiet, but very kind and anxious to help me’.

(#litres_trial_promo) The unassertive, awkward young man still spent much of his time and money digging at Hoxne. ‘Doughty did not take part in such things as rowing, but was always reading geology and philosophy,’ he said.

But before he could specialize in his chosen subject. Doughty had to pass the Cambridge first-year examination, the so-called Littlego. The Greek and Latin which had to be dealt with he treated with a certain amount of disdain, doing the work that was necessary without, apparently, much enthusiasm. Sixty years later his colleague of the gravel pits and the Kimmeridge clay, Henry Thomas Francis, remembered teaching him Classics.

Doughty as an undergraduate was shy, nervous, and very polite. He had no sense of humour, and I cannot remember that he had any literary tastes or leanings whatever. He read Classics with me for his Littlego. He knew very little Greek. When he came up, he was devoted to Natural Science generally. He had made a large collection of Suffolk fossils, and was rather combative in favour of the new studies. He did not like attending lectures.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Francis also recalled a visit from another undergraduate who announced that he was no longer going to take lessons in Classics from him.

I said, ‘Very well, but what are you going to do?’ and after a little hesitation he replied, ‘The fact is, my friend Doughty tells me you bother one with grammar and all that sort of thing, and that it is far easier to get up the whole business by heart.’ My answer was, ‘Then we are right to part, for I can’t teach Latin or Greek on those conditions.’

The young Doughty simply had no time for literature, and certainly no time for the detailed study of language: those passions would come later. For now, with his characteristic singleminded determination, he wanted to concentrate only on his scientific studies.

He had no time, either, for the religious requirements of his college. Even at Caius, which was not among the most dogmatic or conservative of Cambridge institutions, there was a strict rule demanding daily appearances at religious services, and the college’s Chapel Attendance Book shows the young Doughty cautioned twice, and punished once, for his irregular appearances. Maybe unsurprisingly, for a young man who as a boy had been forced to sit through the Revd Bernays’s thunderous sermons, he was less than enthusiastic all his life about organized worship: after his death, his widow observed in a letter, ‘He never (or hardly ever) entered a church during service, but he loved to sit in any church or cathedral for hours. He was truly religious, in spite of never going to church in the orthodox way …’

(#litres_trial_promo)

But Doughty’s studies in geology were already chipping away at the foundations of his own belief in much the same way as similar research had done for Lyell. His Christianity was too closely bound up with his sense of family, of tradition, and of Englishness for him ever to disavow it; but there can be little question that poring over the fossils gathered from the Suffolk chalkland must have sown the first seeds of religious doubt in his mind.

Failing to turn up for chapel was not a grave offence, and not likely to have incurred a serious penalty – probably a small fine or a period restricted to the college grounds – but, for a young man as careful of his dignity as Doughty, any punishment would have been a humiliating experience. It was almost certainly one reason for his decision to ‘migrate’ from Caius to Downing in 1863, two years after coming up to the university – years later, The Times said that the move came ‘after a difference with the head of his original college’

(#litres_trial_promo) – but there were others.

Cambridge University as a whole was gaining a growing reputation in botany and geology – although it would be several years before anything as dangerous or innovative as a scientific laboratory would be opened – and the relatively new Downing College, anxious to improve its academic standing in the university, was offering a number of Foundation Scholarships in Natural Sciences. Doughty’s friend Bradbury had already been accepted for one of these, and although Doughty did not need the £50 a year the scholarship offered, he would have relished the academic standing it would confer.

He was disappointed, because he entered Downing without a scholarship. But simply making the transition from the quiet, enclosed courts of Caius to the wide open spaces of Downing was significant: apart from the lack of enthusiasm at Caius for the newfangled study of science, there was the rigid insistence on the need to attend not only chapel, but also lectures. Doughty wanted to study on his own, and the more easygoing atmosphere at Downing attracted him. His own explanation was straightforward: ‘They bothered me so much at Caius with lectures and chapels and things, and I knew that at Downing I could do just as I liked …’

(#litres_trial_promo) Certainly, Bradbury boasted later that he never attended a single lecture as an undergraduate at Downing – and, as an additional incentive, the college buildings did not yet boast a chapel.

There was no lasting rift with his former college – on the contrary, Doughty remained on cordial terms with Caius, took his Master of Arts there, presented the college with gifts and paintings, and even used it as a forwarding address later in his life. But for someone who felt less than enthusiastic about the entire ambience of the university, Downing was a more congenial place to live than the more staid and ancient Caius. It was a new college, a college for the modern age, and one which seemed to delight in being almost semi-detached from the university as a whole. Doughty walked away from the college where his father and his grandfather had studied without a backward glance. The young man who was to prove himself in so many ways obsessed by tradition and antiquity was showing in his choice of college, as he had in his choice of subject, that he had a strong and determined mind of his own.

There is no doubting the seriousness with which he approached his chosen field of study at Downing – but it was to be several months before he could resume his formal studies.

Throughout his life Doughty complained of weak health – and throughout his life, when it let him down, he would set off at a tangent to ‘convalesce’ in some extravagantly physical and energetic enterprise which would have taxed an athlete in the peak of condition. So it was as he started his first term at Downing: he was granted leave to postpone his final exams, and announced his intention of spending some eight or nine months surveying the fiords and glaciers of Norway.

The declared aim of his journey was the observation of the ice-flows of the Jostedal-Brae glacier field, and he fulfilled it completely enough to produce his second paper for the British Association when he returned. But those studies took only a couple of months, and much of the rest of his time was spent wandering more or less at random, in much the same way as he did later through Europe and Arabia. Before he travelled north-west to the Jostedal-Brae, he had spent some time at the university in Christiana, as Oslo was then called. The earnest young Englishman, diligently jotting down words and phrases of Danish as he struggled to build up a working vocabulary, must have been an unusual sight in the small university, which had only been founded fifty years before. Norway was a poor country: it was more customary for their students to travel abroad than for foreigners to come there.

Doughty’s priorities remained scientific, but his interests extended far beyond the university. This was not the quiet, studious life he had enjoyed at Cambridge: instead, he set off into the hills, lodging with farmers and gamekeepers, sometimes sleeping rough in log huts, and trekking for days at a time on shooting expeditions that took him and his guides miles into the remote mountain slopes.

It was a time that he remembered in Arabia years later when, near the end of his travels, he struggled from the interior towards Mecca ‘in a stony valley-bed betwixt black plutonic mountains, and half a mile wide: it is a vast seyl-bottom of grit and rolling stones, with a few acacia trees. This landscape brought the Scandinavian fjelde, earlier well-known to me, to my remembrance.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

That description gives some idea of the Norwegian countryside to which he had travelled, supposedly for the sake of his frail health, and when, in mid 1864, he arrived at the sixty-mile-long ridge of the Jostedal-Brae, it was to find an environment and a lifestyle that were certainly no easier. ‘Here is an arctic climate, and we found the lakes covered with ice in the middle of August, still thick enough to bear some wild reindeer, which we disturbed. We slept under a stone, while it froze outside, according to a minimum thermometer.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Five separate glaciers descended from the ridge into a gorge below, which was so deep and sheer that the sun hardly reached it during the winter months. It was remote, unfriendly country, with just a few scattered farms and a rough bridle path between the rounded boulders which the glaciers had brought inching down with them from the mountains.

But it was a magical land as well, and it was not just Doughty the geologist scrambling with his guide over the rocks, ice and broken ground. As he wrote his report later, his descriptive enthusiasm struggled against a determined scientific detachment. The Nigaard glacier, he wrote,

seems to flow down in elegant curves; though in reality this is due to the tossing up of the surface by some submerged knees of the mountains, and it passes through nearly a straight channel. No stones or earth soil its glittering surface, which appears capping the cliffs and creeping down every depression and pouring out its water in picturesque threads down the rocks.

(#litres_trial_promo)

At the foot of Lodal’s glacier, meanwhile, water came gushing out from an arched cavern in the ice some thirty feet high. The name of the lake, Styggevaten, meant ‘horrid-water’, he jotted carefully in his notebook – names and their meanings would carry a fascination for him throughout his travels, landscape and language inextricably linked in his mind. Between the detached response and the imaginative, he saw little distinction: at times, the Jostedal-Brae sounds almost like the setting for a mystical scene from Ibsen: ‘Loud peals are heard booming among the heights when some new ice-shoot takes place and seems to smoke in the distance,’ he wrote.

It was also a landscape that encouraged thoughts about the continuity between the present and the far past – the ice offering the imaginative possibility of a direct link with the most distant history. That was the sort of speculation that appealed instinctively to Doughty, and he noted that the glaciers were continually engulfing plants and animals, preserving them virtually for eternity. Humans, too, he said, must occasionally be entombed. ‘Very early traces of the human race may some day be dug out from the deposits of the later glacial period, if man was then in existence and inhabited those parts of the globe …’

But his primary task was the more prosaic one of measuring the speed of the glaciers’ movement. He had been loaned a theodolite by the Royal Geographical Association to help him with the detailed surveying – his first contact with that august body, later relations with which were to prove volatile. For the rest, he had a rope, an iron-tipped stick, a set of metal spikes to help him stand on the ice, and the aid of a local guide, one Rasmus Rasmussen.

With this rudimentary equipment, by driving stakes into the ice of the glacier as markers, and building matching stone cairns off to one side, he produced a series of tables for the different glaciers to show the varying speed of the flow. They were, he noted with pardonable pride, the first measurements ever obtained of the seasonal motions of Scandinavian ice streams.

It was a subject of some current scientific interest. Geologists were arguing about exactly what caused glaciers to flow, and Lyell himself was enquiring into the subject for the new edition of his Principles. But though there can be no doubting the enthusiasm and determination of the twenty-one-year-old Doughty, his figures leave something to be desired. The distances between his markers, he admits, were little more than estimates; on one glacier, presumably having forgotten to use his theodolite, he has guessed the gradient; and one complete set of figures, setting out the lengths of the different glaciers, he has simply lost, replacing them with estimates.

Later, he was to claim that, in preparing the last edition of his Principles of Geology, Lyell called on the young undergraduate to ask for details of his observations.

(#litres_trial_promo) It is certainly likely that Doughty made the great man’s acquaintance: the first thing he did when he returned from Norway was prepare a paper for the annual meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science on his observations. Lyell, then president of the association, was speaking about glaciation in his inaugural address: what more natural than that he should exchange a few words with the shy, gangling youth who had just returned from Norway? That, though, is as far as it went: the Principles includes little about Norwegian glaciers, nothing at all about the Jostedal-Brae, and certainly no acknowledgement of assistance from Charles M. Doughty and his lackadaisical measurements.

But the expedition had given him at least the beginnings of a scientific career. He had become a life member of the British Association earlier that year; now, the misspelled name of C. Montague Doughty was printed in the list of members – albeit with his address, too, wrongly listed as Dallus College, Cambridge. While the paper he had produced after his diggings at Hoxne had been only briefly noted by its title in the annual report, the account of this latest one, which was presented to the association’s Bath meeting, ran to 350 words. He had also, though still an undergraduate, been making the social contacts necessary for a career in science. He had cultivated not just the acquaintance of Sir Charles Lyell himself, but also that of several other worthies of the British Association and the Royal Geographical Society. And, most important of all, if he had been disappointed not to be given a scholarship by Downing, he was still confidently expected to gain a first-class degree.

But in December 1865 those expectations were dashed. Doughty found himself near the top of the second class in the Cambridge Tripos examinations – although it seems that his examiners were at least as disappointed as he was with the result. More than fifty years later Professor Thomas George Bonney, then Professor of Geology at London University, said of his distinguished pupil: ‘I was very sorry not to be able to give him a First, as he had such a dishevelled mind. If you asked him for a collar, he upset his whole wardrobe at your feet.’

(#litres_trial_promo) It would not be the last time in his life that Doughty would be criticized for hurling facts at his readers by the handful.

But while such an examination result would have been a setback, it would not necessarily have prevented him from following a career as a scientist, particularly as he still enjoyed the financial support of his father’s legacy. Doughty, though, seems to have changed his priorities during that final year at Cambridge: although he prepared his report on Jostedal-Brae for its full publication, he had abandoned any thought of making his name through science.

A letter written to him shortly before his final examinations by the Revd Henry Hardinge, the rector of Theberton, seems to confirm that he still had grandiose plans – the adolescent boy who had been turned down by the navy clearly still thought in the same patriotic terms of serving his country. Hardinge refers to Doughty’s ‘researches and noble ambition as regards this earth’, and goes on to praise his determination to ‘soar above the vanities of this world and take a place among the worthies who have lived for its adornment and the real glory of God’.

(#litres_trial_promo) But the researches and noble ambition would be directed at literature: though science and geology would remain among his interests, his life, he had decided, would be devoted to writing. He left the university with his second-class degree, no firm plans for a career, and a brief formal note of introduction from Bonney.

Doughty, after all, could afford high-flown ambition: there was no pressing need to find a way of earning his living. His education had not been designed to fit him for a career, unless perhaps, like his father, as a parson in one of the Suffolk livings. His inheritance should have enabled him to live a life of comfortable scholarship. For fifteen years his financial affairs had been cautiously managed, with his father’s old friend, Henry Southwell of Saxmundham, and his own uncle and guardian, Frederick Goodwin Doughty, acting as trustees. Now, with his studies behind him, he could take up the rights that had passed to him on his twenty-first birthday. He had both the power and the leisure to handle his wealth himself.

What he does not seem to have had was luck or shrewdness: over the next three or four years his inheritance simply withered away. He was never to show the remotest financial acumen, and it is significant that the collapse of his financial affairs should have come just after he took over the active management of his investments from his father’s trustees.

Neither Doughty nor anyone else in his family would ever say exactly what happened. Fifty years later the memory of the collapse clearly still hurt: asked about stories of his past involvement in the printing industry, he replied shortly, ‘Printing I conceived of in my early inexperience as an adjunct to literature, but I was deceived in that matter, and was somewhat of a victim. Therefore it would not be kind to mention it.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

His widow would only speak generally of ‘depreciation of investments’ – but the overall effect was that the rest of Doughty’s life was passed in a state of genteel poverty. Years after his death she turned down the offer of financial help for herself and her daughters from her husband’s friends: ‘Really we are much better off than a good many people … I think Rubber will recover in time; I have put up half the grounds for sale; if a small bungalow is built it won’t hurt us, but so far, I’ve had no success there. I sold 5 dozen spoons and forks for £17 …’

(#litres_trial_promo) Her husband’s books, respected as they were, made little money: financially, he simply never recovered from the crushing blow of his early twenties.

Doughty’s response at the time was to bury himself in his books. The letter of recommendation he had taken with him from Cambridge had been addressed to the Library of Winchester College, probably because of some personal connection of Bonney’s; but he used it, and his standing as a graduate, to gain entrance to the Bodleian Library in Oxford.

His name first appears in the Bodleian’s records on 1 December 1868; and for the next fourteen months he was an assiduous reader there. He was, he said later, a solitary man, and entirely dependent now on his own resources to direct his studies – but a glance down the list of books he was reading at the time demonstrates that he had already established where his primary interests lay. There is nothing of modern science – and precious little as late as the seventeenth century.

There is Gavin Douglas’s translation of The Aeneid, published in 1553; several books of medieval songs and ballads; a number of Anglo-Saxon grammars and dictionaries; commentaries on the Bible, catechisms and sermons. Doughty was immersing himself in the distant past. Above all, he was reading Spenser and Chaucer, the two poets he believed all his life had reached the uncontested summit of English literature. It was they, he told an interviewer not long before he died,

(#litres_trial_promo) who finally decided him upon a life dedicated to poetry.

When, at the end of his life, he completed Mansoul, which he firmly believed to be his greatest work, he declared: ‘I have not borrowed from any former writer; save I hope something of the breath of my beloved, Master Edmund Spenser, with a reverend glance backward to good old Dan Chaucer …’

(#litres_trial_promo) It was at the Bodleian, as he threw himself wholeheartedly into the new life of a poor scholar, that he first made their acquaintance.

But there is one book among the volumes of ancient history and literature which seems slightly out of place. Of the works of the seventeenth-century writer George Sandys Doughty chose neither his translations of Ovid, nor his poems based on the Psalms and the Passion, but his travel writing, A Relation of His Journey to the Levant.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Possibly he was struck by the similarities between his own position and that of his Jacobean predecessor, who came, like him, from a background of well-connected country gentlefolk with naval antecedents. Sandys, too, had been a literary man and an academic – and in 1610, at the age of thirty-two, he had set off on a journey that took him through Europe and into the Middle East.

The two years of wanderings described in Sandys’s book took him through France, Italy, Egypt, the Middle East and Malta. He gazed with a slightly bilious eye on the ancient wonders of the pyramids and of the city of Troy; he was robbed and manhandled by angry Muslims in the towns of Palestine and as he journeyed by caravan across the desert; he was fascinated by the habits and beliefs of the common people who were his companions.

There were moral and religious lessons to be drawn from his travels. The naturally rich lands of the Middle East, he wrote, were now waste, overgrown with bushes, and full of wild beasts, thieves and murderers. It was a country in which Christianity – ‘true religion’ – was discountenanced and oppressed: ‘Which calamities of theirs, so greatly deserved, are to the rest of the world as threatening instructions … thence to draw a right image of the frailty of man, and the mutability of whatever is worldly.’ The thought, and its expression, could almost have come from the pages of Travels in Arabia Deserta two and a half centuries later.

Doughty still hoped to achieve some great literary success, but in the meantime, he could no longer afford the leisured scholastic career he had anticipated: he would have to find some way of supporting himself on his greatly reduced means. Travel, and the life of a wandering scholar, might offer one solution.

Chapter Two (#ulink_6c245a9e-4c7e-5bc4-b2b0-5cb555dfccb8)

The next year, out of a reverence for the memory of Erasmus, Jos. Scaliger, etc., I passed in Holland learning Hollandish … I spent some months also at Louvain and the winter at Mentone (I had always rather poor health). I travelled then in Italy and passed the next winter in Spain, and most of the next year at Athens; and that winter went forward to the Bible lands …

Letter to D. G. Hogarth, August 1913

The Charles Doughty who left England for the continent in 1870 was a man who had been emotionally battered almost to submission – shy, retiring, and without a shred of emotional self-confidence. At twenty-seven, he was a Master of Arts, a scholar widely read in medieval literature and with some knowledge of geology and science, a man filled with literary and academic ambition, but without any obvious means of earning a living. His studies provided one safe retreat from the daunting world of human relationships; the lonely life of a solitary wanderer would be another.

There was no need to reach back to the sixteenth century for explanations for his decision to travel. The idea of paying homage to Scaliger

(#litres_trial_promo) and Erasmus,

(#litres_trial_promo) the one looking back from his own time to ancient history, the other rejecting the calling of a churchman and then leaving Cambridge to wander Europe as a peripatetic scholar, was appealing to his intellectual self-esteem, but it did little to explain his real motives.

One manifestation of his chronic lack of confidence was his constant wittering concern about his health. It had already led him to abandon his studies at Cambridge for a year, and he would claim later in his life

(#litres_trial_promo) that his hard work in the Bodleian had left him weak, ill, and in need of a change of climate. It was a common predilection: the hotels and sanatoria of Menton and the other Mediterranean resorts were full of sickly Englishmen taking the air, although few of them would have undertaken travels as extensive or as energetic as Doughty himself was embarking upon.

Like some of them, he had a pressing financial motive for leaving Britain. He had neither possessions nor prospects to keep him in England, and contemporary guidebooks estimated that something under ten shillings a day

(#litres_trial_promo) should be sufficient for walking tours in remote areas of Europe. Life could be lived much more cheaply travelling the streets of the continent than at home; the future would have to look after itself.

So to save his money and to preserve his health, he decided to go abroad. But the letter to Hogarth more than forty years later puts his supposed weak constitution into context: the hardships and discomforts he was to endure over the next eight years would have killed a less hardy individual. He was a man dedicated to living his life through his books and scholarship – and yet, at this time of personal crisis, Doughty the diffident intellectual was determinedly pitting himself against a series of physical challenges. It would not be the last time.

It was not exactly a Grand Tour that he undertook: Europe was in ferment, with either open fighting or sullen, smouldering peace in France, North Africa, Spain and the Balkans. Doughty faced the prospect not just with courage but with all the insouciance of an English gentleman as he picked his way from troublespot to troublespot, peering superciliously past the shattered landscapes and the weary people to jot down his reflections about the ancient ruins he had come to see.

For his first few months out of England, though – ‘a long year’, he called it later

(#litres_trial_promo) – he stayed in Leiden and the nearby Dutch towns, following his lonely studies and applying himself to learning the language.

He had a vague idea of investigating the historical background of the English civilization which fascinated him – but when he left Holland, he had, like Sandys before him, no plan for where his travels or his studies would lead him. The opportunity to observe the life of the travelling Arabs at first hand – the opportunity which was to provide him with the raw material for his greatest literary work – came to him by chance rather than by intent. One of his greatest talents was in allowing his life to be taken over by such chances and in seizing the benefit of them.

The next two years are the first period of Doughty’s life for which his own detailed and contemporary records exist. His diary, painstakingly written in his neat, precise hand, with its occasional pen and ink or pencil diagrams and sketches of landscapes, archaeological remains, or whatever else caught his attention, is far from exhaustive: some vital moments are casually skipped, there are occasional long gaps with no entries at all, and the whole account ends in March 1873, with Doughty still in Italy. His later travels around Greece, Egypt, Sinai and the Middle East can only be pieced together from letters, later memories and other patchy records. Even more frustrating, for much of the time as he wandered around Europe, his imagination seemed infuriatingly disengaged. But the hardback notebook which is now kept in the library of Caius College, Cambridge, faded and battered at the edges, gives an intimate picture of his intellectual and emotional development over a crucial spell of his young adulthood.

It starts as he leaves Leiden for Louvain, with a distaste for his surroundings which was to become familiar over the next few months: Doughty’s impressions of northern Europe were less than enthusiastic. In Louvain – a ‘very filthy and unwholesome’ town – he noted ‘the obscene manners of the people who piddle openly in every place’, although the observation was carefully crossed out in the diary. Presumably it was a little too crude even for a personal notebook. It remains legible, though, behind Doughty’s pencil scribble, as his fastidious indictment of the Belgian people.

He presents much the same litany of dissatisfaction that any middle-class traveller from Britain at that time might have recited. The people, being foreign, were grubby, unhealthy and – worst of all – Catholic.