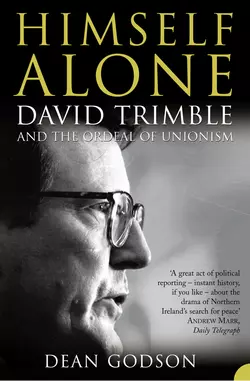

Himself Alone: David Trimble and the Ordeal Of Unionism

Dean Godson

The comprehensive and groundbreaking biography of the Nobel Peace Prize-winning politician, one of the most influential and important men in Irish political history.Please note that this edition does not include illustrations.How did David Trimble, the ‘bête noire’ of Irish nationalism and ‘bien pensant’ opinion, transform himself into a peacemaker? How did this unfashionable, ‘petit bourgeois’ Orangeman come to win a standing ovation at the Labour Party conference? How, indeed, did this taciturn academic with few real intimates succeed in becoming the leader of the least intellectual party in the United Kingdom, the Ulster Unionists? And how did he carry them with him, against the odds, to make an ‘historic compromise’ with Irish nationalism?These are just a few of the key questions about David Trimble, one of the unlikeliest and most complicated leaders of our times. Both his admirers and his detractors within the unionist family are, however, agreed on one thing: the Good Friday agreement could not have been done without him. Only he had the skills and the command of the issues to negotiate a saleable deal, and only he possessed the political credibility within the broader unionist community to lend that agreement legitimacy once it had been made.David Trimble’s achievements are extraordinary, and Dean Godson, chief leader writer of the ‘Daily Telegraph’, was granted exclusive and complete access while writing this book.

DEAN GODSON

HIMSELF ALONE

DAVID TRIMBLE

AND THE ORDEAL OF UNIONISM

DEDICATION (#ulink_577e214d-cb64-5e7c-8b9c-f47bb97943fe)

For my mother above all

but not forgetting Paul, Greta, John, Evelyn, Charlie and Gill

EPIGRAPH (#ulink_d9eb67f2-7880-5b38-9434-38861fb49c24)

I am Ulster, my people an abrupt people

Who like the spiky consonants in speech

And think the soft ones cissy; who dig

The k and t in orchestra, detect sin

In sinfonia, get a kick out of

Tin cans, fricatives, fornication, staccato talk,

Anything that gives or takes attack,

Like Micks, Tagues, tinkers’ gets, Vatican.

An angular people, brusque and Protestant,

For whom the word is still the fighting word,

Who bristle into reticence at the sound

Of the round gift of the gab in Southern mouths.

Mine were not born with silver spoons in gob,

Nor would they thank you for the gift of tongues;

The dry riposte, the bitter repartee’s

The Northman’s bite and portion, his deep sup

Is silence; though, still within his shell,

He holds the old sea-roar and surge

Of rhetoric and Holy Writ.

W. R. Rodgers; from ‘Epilogue’ in Poems,

Michael Longley (Oldcastle,

Co. Meath, 1993), pp. 106–7

‘Whatever an Ulsterman may be, he is certainly never charming, and of that fact, no one is more fully aware than the Ulsterman himself.’

F. Frankfort Moore, The Truth about Ulster

(London, 1914), p. 102

‘I’ve changed, you know.’

David Trimble to his old friend, Professor Herb Wallace,

after signing the Belfast Agreement

‘What do you want for your people?’

‘To be left alone.’

Exchange between Sean Farren, a senior nationalist politician, and David Trimble at Duisburg, in the late 1980s

CONTENTS

Cover (#udf00273a-7711-5d96-82a4-4ea9d2157865)

Title Page (#u4eed21a0-01d7-5810-a72e-55be892ba225)

Dedication (#ub50f7d48-e9af-5b1b-8a16-9b8f7dda6139)

Epigraph (#u01b49454-9682-52ff-82be-26f2c62ee628)

1. Floreat Bangoria (#uc8a2b8d3-9b85-5831-8a67-7fdade424f7f)

2. A don is born (#ua8473915-a50e-54a5-af98-60d34ff8e5b8)

3. In the Vanguard (#ua48d16ca-1ac5-59de-bb2f-7ac88de71546)

4. Ulster will fight (#u8fbac1ba-7e61-5f22-a52b-cbf60fe0f33c)

5. The changing of the Vanguard (#ueb95a73e-0a61-5509-89c9-ab3cbb31d5ec)

6. Death at Queen’s (#ud74356db-bb36-5d50-8239-504dca295f8f)

7. He doth protest too much (#u6e5463c8-f946-5b62-bed6-55c444c945f8)

8. Mr Trimble goes to London (#ud45474d2-8012-5bd5-a2be-4771a92fc383)

9. Framework or straitjacket? (#ufbc02443-7689-509a-9962-ad65e8636e05)

10. The Siege of Drumcree (I) (#u667991cf-055c-5372-a654-67841a77de92)

11. Now I am the Ruler of the UUP! (#u5948bf03-f9ef-5f65-b236-4aa45ed7dbc4)

12. The Establishment takes stock (#ua6aa7a5b-ec7f-5fa4-8e82-bad0783d9e10)

13. Something funny happened on the way to the Forum election (#ucdaf96f1-d5ef-57e9-8109-705735d04a4c)

14. Go West, young man! (#uc05d3774-75a1-58a7-8cec-5a19f70e0957)

15. ‘Binning Mitchell’ (#u0a0c7417-1aa1-5805-9964-4091f12b7179)

16. ‘Putting manners on the Brits’ (#u737dbbb3-b6a6-5770-9700-4d52a8e287d5)

17. The Yanks are coming (#u69c5eef1-f8e9-5962-9a17-4d3766ed5861)

18. The Siege of Drumcree (II) (#u7ce1f546-bbb0-558d-a028-3b5fd9418d47)

19. Fag end Toryism (#litres_trial_promo)

20. The unlikeliest Blair babe (#litres_trial_promo)

21. The pains of peace (#litres_trial_promo)

22. When Irish eyes are smiling (#litres_trial_promo)

23. Murder in the Maze (or the way out of it) (#litres_trial_promo)

24. Long Good Friday (#litres_trial_promo)

25. ‘Let the people sing’ (#litres_trial_promo)

26. A Nobel calling (#litres_trial_promo)

27. The blame game speeds up (#litres_trial_promo)

28. No way forward (#litres_trial_promo)

29. RUC RIP (#litres_trial_promo)

30. By George (#litres_trial_promo)

31. ‘And the lion shall lie down with the lamb’ (#litres_trial_promo)

32. Mandelson keeps his word (#litres_trial_promo)

33. The Stormont soufflé rises again (#litres_trial_promo)

34. In office but not in power (#litres_trial_promo)

35. A narrow escape (#litres_trial_promo)

36. The luckiest politician (#litres_trial_promo)

37. Another farewell to Stormont (#litres_trial_promo)

38. A pyrrhic victory (#litres_trial_promo)

39. Paisley triumphant (#litres_trial_promo)

40. Conclusion (#litres_trial_promo)

Glossary (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Author’s Note (#litres_trial_promo)

Notes (#litres_trial_promo)

Praise (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

ONE Floreat Bangoria (#ulink_665249fa-87ef-591a-833c-f088d4c53c1e)

WILLIAM David Trimble was born on 15 October 1944, at the Wellington Park Nursing Home in Belfast of respectable, lower-middle-class, Presbyterian stock. From his earliest years he was called David, apparently to distinguish himself from his father, William Sr. The gregarious elder Trimble was generally known as ‘Billy’, but his flinty son was to reject all such attempts to turn him into a ‘Davy’ or a ‘Dave’. He remained resolutely ‘David’. This name apparently derives from his paternal grandfather, George David Trimble, born in 1874 and a native of Co. Longford. The earliest Protestant settlement there can be traced back to the reign of James I, though there was an overspill into Co. Longford resulting from subsequent influxes of Scottish Presbyterians into Ulster at the end of the 17th and early 18th centuries. Indeed, at its pre-Famine peak, the Protestant community numbered around 14,000 and the 1831 census suggests that it comprised 9.5% of the population. As late as 1911, in the parish of Clonbroney where the Trimbles lived, Protestants comprised 18.3% of the population.

(#litres_trial_promo) It is not known when the Trimbles – a variation of the Scottish Lowland name of Turnbull – arrived in Co. Longford.

(#litres_trial_promo) But what is certain is that David Trimble’s own line of descent can be traced back to the end of the 18th century (he is not related to the Co. Fermanagh Trimbles, whose descendants own the famed Impartial Reporter and Farmers’ Journal. By coincidence, his wife is part of that extended family). Like most Protestants, the Co. Longford Trimbles and the families they married into – the Smalls, the Twaddles, the Gilpins and the Eggletons – were farmers, with a few ploughmen, stewards and underagents amongst them. The first available record is of one Alexander Trimble (DT’s great-great-grandfather) who farmed in Sheeroe, Co. Longford. His son, also called Alexander (DT’s great-grandfather), lived from 1826 to 1904 and had eight children of whom the above-mentioned George David (DT’s grandfather) was the youngest. According to Griffith’s valuation of property in Ireland, conducted in the 1850s and 1860s, Alexander Trimble (II) rented a plot from one of the Edgeworths, the main landowners in the area, comprising lands of 11 acres, 3 roods and 16 perches. Its rateable valuation was £9 and 5 shillings, with buildings thereon valued at £1 and 15 shillings. But unlike most Protestants in Co. Longford, who were adherents of the Church of Ireland, the Trimbles were staunch Presbyterians: the parish registers show that George David, DT’s grandfather, was baptised at Tully Presbyterian Church in 1875. They were thus a minority within a minority. History does not record how these Trimbles felt about the Ascendancy, in the shape of the Edgeworth family, nor about the Church of Ireland itself. If they keenly felt the disabilities long imposed upon Dissenters, it echoed down the years in odd ways: David Trimble himself never much cared for the traditional Unionist establishment.

The world of the Trimbles, like those of so many smallholders, would have been far removed from the elegiac evocations of ‘Big House’ Protestant life described by Somerville and Ross or Elizabeth Bowen. Especially during the latter half of the 19th century, they became increasingly vulnerable. There were a number of reasons for this: changing patterns in the rural economy, which led to the disappearance of farm servanthood and labouring jobs; difficulty in finding suitable local spouses, sometimes leading to intermarriage with Catholics and to conversion; and the lure of North America. Another, darker explanation for the decline in the Protestant population was the rising tide of Catholic disaffection – which took an increasingly violent form – and the attempts of some of the bigger landlords and of the British Government based in Dublin Castle to appease such anger through a variety of reforms at the Protestant smallholders’ expense.

(#litres_trial_promo) According to J.J. Lee, mid-19th-century Co. Longford was one of the six most disturbed counties in Ireland. David Fitzpatrick further states that in the immediate pre-Partition era, Sinn Fein membership in Co. Longford totalled between 600 and 1000 out of a 10,000 population, the highest of any county.

(#litres_trial_promo) Whatever the exact causes of the collapse of the Protestant population of Co. Longford, the community undoubtedly declined by 40% between 1911 and 1926. By 1981, there were fewer than 1500 in the entire county. Census returns from Clonbroney at the time of the 2002 Easter Vestry to the Church of Ireland Diocese of Elphin and Ardagh showed that there were 43 regular worshippers – compared to 1010 in 1831.

(#litres_trial_promo) In Longford as a whole, there were around 40 Presbyterians left in 2003, plus around 80 Methodists. Tully Presbyterian Church closed in the 1950s; only one, at Corboy, is left in the county. As Liam Kennedy concluded in his authoritative study of the Protestants of Longford and Westmeath, ‘The Long Retreat’, ‘there is little comfort here for those seeking stories of ethnic accommodation along pluralist lines. True enough, by the 1930s or ’40s, unlike the case of Northern Ireland, there was no minority ethnic or religious problem in the region. There was no minority.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Throughout his career, David Trimble has been determined that the Protestants of Northern Ireland, and pro-Union Catholics, not suffer the same fate.

George David Trimble, DT’s grandfather, was part of that exodus – though, again, his exact reasons for leaving remain unknown. Originally a farmer, he joined the Royal Irish Constabulary in 1895 (it seems an uncle, one Thomas Trimble, born in 1819, had earlier served in the Dublin Metropolitan Police from 1840–8). After tours of duty in Sligo, Armagh, Belfast and Tyrone, George David Trimble returned to Ulster’s capital in 1909. He remained there for the rest of his life, attaining the rank of Head Constable. According to the official records, he received a life annuity of £195 upon the disbandment of the RIC in 1922, and then joined the newly created Royal Ulster Constabulary: his service record has neither blemishes nor commendations on it. He ended his career in 1931 at Donegal Pass RUC station and died in 1962, aged 87. Thus it was that the Trimbles came to settle in the ‘greater Belfast area’, as it is now sometimes called.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Moustachioed Grandfather Trimble was a great ‘spit and polish’ man, who would daily ‘bull’ his boots till he could see the reflection of his face.

(#litres_trial_promo) He stood at over six-foot-three and was not one to be trifled with: he had been through the severe inter-communal rioting which racked Belfast at the time of Partition and was ever on his mettle. When some relatives from the newly created Free State banged on his door in jest, shouting ‘we’ve come to get you, Trimble’, he drew his gun from his holster and repeatedly fired through the wooden panels, scattering his terrified country cousins.

(#litres_trial_promo) According to Maureen Irwin, David Trimble’s sole surviving first cousin, the ‘Trimble temper’ comes down from Grandfather George Trimble; the red hair and the florid complexion come from Grandfather Trimble’s diminutive wife, Sarah Jane Sparks, daughter of James Sparks, a farmer of Cullentrough, Co. Armagh, to whom he was married in 1903. Grandfather Trimble sired three red-headed sons; the eldest, Norman, emigrated to Arizona; the middle child, Stanley, followed his father into the RUC and also attained the rank of Sergeant; Billy, the youngest, was born in 1908.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Grandfather Trimble was also a staunch Presbyterian: when Stanley Trimble had his children baptised in the Church of Ireland, Grandfather Trimble was furious, believing that little separated the Anglicans from Rome. ‘Were you at Mass today?’ he would ask his grandchildren in later years.

(#litres_trial_promo) Grandfather Trimble also signed the Ulster Covenant of 1912 – a mass pledge against Asquith’s Home Rule Bill – at the Sandy Row Orange Hall. Indeed, he was a pillar of the Orange Order, rising to the post of Master of Ballynafeigh District Lodge (Ballynafeigh District’s traditional 12 July parade through Belfast’s Lower Ormeau Road became the most controversial Orange walk after Drumcree during the 1990s). The population of the area, once overwhelmingly Protestant, is now overwhelmingly Catholic; David Trimble wonders what kind of reception he would receive today if he returned to the string of modest terraced houses where Grandfather Trimble used to live in and around the ‘Holy Land’ of south Belfast (so called because of the large number of Middle Eastern street-names): at Agincourt Avenue, Carmel Street and at Jerusalem Street (where Billy Trimble was born). Latterly he lived across the Lagan at 50 Candahar Street, where the young David used to visit him on day trips.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Strangely, Dàvid Trimble was quite unaware of his links to the Ballynafeigh District Lodge until he became leader of the Ulster Unionist party. This may owe something to the influence of his mother, Ivy Jack, who regarded the Loyal Orders as vulgar and who appeared unhappy when the teenaged Trimble eventually joined the Orange Order in 1962 (Billy Trimble was never a member, though he was a Mason). Ivy Jack was born in 1911, the only child of Captain William Jack and of Ida Colhoun. The lineage of Capt. Jack (DT’s maternal grandfather) can be traced back at least as far as one Samuel Jack (DT’s maternal great-great-grandfather), a landed proprietor of Lisnarrow in the parish of Donagheady, Co. Tyrone, who lived from 1776 to 1846. His son, also Samuel (DT’s great-grandfather), became a prominent official of the Londonderry Corporation and for over 30 years served as water superintendent. His death notice in the Londonderry Sentinel of 16 February 1897 states that he was ‘a staunch Unionist in politics … one of the electors who suffered “excommunication” from the Covenanting Church rather than forgo his right to vote at the Parliamentary elections’. Formally known as the Reformed Presbyterian Church of Ireland, the Covenanters were quite separate from the much larger Presbyterian Church in Ireland: they were descended from the Scots Covenanters, and did not agree with the Revolution Settlement of 1689 because it did not reaffirm the Solemn League and Covenant of 1643, which swore to recognise Christ as King of the Nation. Since the Revolution Settlement did not provide the reassurance which they sought, the Covenanters held it was inconsistent for their communicant members to vote in parliamentary elections. Most of their flock went along with this ruling, but Samuel Jack was highly unusual in his unwillingness to give up the hard-won right of Dissenters to exercise this democratic liberty.

(#litres_trial_promo) A hundred or so years later, his Presbyterian great-grandson, David Trimble, would also endure a kind of ostracism – again, risking much for his rejection of what he considered to be the other-worldly purism of some of his fellow Protestants.

Samuel Jack’s son, Capt. William Jack (DT’s grandfather), worked for J. & J. Cooke, timber merchants and subsequently for Robert Colhoun Ltd, the building and construction firm owned by his wife’s family. He was a Derryman all his life – he served on the Board of Guardians – and signed the Ulster Covenant of 1912. Grandfather Jack only left Londonderry during the First World War in his 40s: in June 1915 he was given a temporary commission as a 2nd Lieutenant in the 12th Battalion of the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, a support unit which furnished drafts to the 36th (Ulster) Division. In October 1916, he transferred to the southern-recruited Royal Irish Regiment and was posted to the 1st Garrison Battalion which provided guards for bases and prisoners. He then went to Egypt during Allenby’s campaign in the Middle East against the Turks, but appears not to have left the place during the liberation of Palestine from the Ottomans. Instead, he spent much of his time in the British military hospital in Cairo: the service records in the PRO say nothing of wounds, as they normally would, suggesting he was felled by malaria or some other infection. After the war, he returned to his home at 5 Eden Terrace, in the city’s Northland district.

(#litres_trial_promo) It was some five minutes away from the house in Glenbrook Terrace where Trimble’s fellow Nobel Laureate, John Hume, grew up (although, as John Hume is keen to point out, the Jack residence was in a much more up-market area).

(#litres_trial_promo) It is a neighbourhood from where most Protestants have now fled. ‘The biggest thing that’s happened in Northern Ireland over the last 30 years is the ethnic cleansing of the west bank [of the River Foyle]’, notes Trimble. ‘There were 10,000 there till the early 1970s. The North Ward was Protestant. That’s all gone.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Captain Jack’s wife, Ida, was undoubtedly the most influential of Trimble’s grandparents. Following her husband’s death, she was crippled and came to live with her daughter and son-in-law until her death in 1966. Ida Jack was ever-present during Trimble’s childhood and teenage years and imparted a smattering of loyalist lore to young David. She told him of how the inhabitants of Derry were reduced to eating rats during the Siege of 1689 and of how a forebear, one Robert Colhoun, had been in the Siege. She claimed that he subsequently married a daughter of George Walker, the Rector of Donoughmore and joint governor of the city during the Siege (such claims are, however, not uncommon in many old Ulster families).

(#litres_trial_promo) She also signed the Ulster Covenant in 1912. Family tradition holds that the Colhouns originally came from Doagh Island off the Inishowen peninsula in Co. Donegal. They left in the early 19th century because of deteriorating land conditions and eventually came to Londonderry, via Malins, Co. Donegal, in 1860 (John Hume’s family made a not dissimilar journey from Inishowen).

(#litres_trial_promo) The tithe applotment books show that they settled in Elaghtmore in the parish of Templemore, Co. Londonderry. Ida Colhoun was one of seven children of Robert Colhoun and his wife Anne Walker (DT’s maternal great-grandparents), the daughter of one David Walker, a leather dealer from the Diamond on the west bank of the Foyle (DT’s great-great grandfather). Robert Colhoun had founded the family construction firm: their buildings included the military barracks and Roman Catholic Church at Omagh, substantial tracts of the Bogside, the Guildhall in Londonderry and the Methodist Church at Carlisle Road, also in the Maiden City. The construction firm was eventually run by his mother’s first cousin, Senator Jack Colhoun, a former Mayor of Londonderry, known to Trimble as ‘Uncle Jack’ (prior to the prorogation of Stormont in 1972, the Lord Mayor of Belfast and the Mayor of Londonderry were ex-officio members of the Northern Ireland Senate). The company ran into financial difficulties during the construction of Altnagelvin Hospital, which was to become Londonderry’s leading infirmary. Although he did not have to do so, Colhoun sold up in 1961 in order to ensure that none of his subcontractors was out of pocket. Trimble was impressed by such probity. Indeed, when the Northern Ireland civil rights movement denounced the ‘rotten borough’ practices of the old Londonderry Corporation in the late 1960s, Trimble reacted on both a personal and on a political level. Recalls Trimble: ‘I thought “Well, I know Uncle Jack. And I know he’s not corrupt.” So I started to think about things more deeply.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Billy Trimble met Ivy Jack whilst he was working in Londonderry as a middle-ranking official in the Ministry of Labour; she was a clerk-typist in the same department. They were married in the Great James Street Presbyterian Church in the Maiden City on 7 December 1940. Billy Trimble soon returned to Belfast, where he eventually became the deputy manager of the labour exchange at Corporation Street. Known in the local vernacular as the ‘Broo’ (a corruption of ‘Bureau’), it was the largest such centre in Northern Ireland. The Trimbles settled in Bangor, which had become something of a dormitory town for Belfast and was rapidly expanding because of the post-war baby boom. They resided at an artisan’s house, 1 King Street, just off Main Street, where David Trimble lived until he was four: his first memory is of the relaxing of sweets rationing in 1947. Although Trimble could, by his own admission, often be awkward and gauche in his dealings with his parents, peers and the outside world generally, he was always the dominant sibling. His older sister, Rosemary, born in 1943, was not overly assertive; his younger brother Iain, born in 1948, naturally looked up to him.

Trimble’s mother, Ivy, was, by his own testimony, ‘middle class moving downwards’. Little of the Colhoun legacy came down to her, and she was obliged from the early years of her marriage to bear the burden of caring for her own mother. Moreover, her husband’s career went awry in his 40s: it may have had something to do with his heavy drinking, which became even more pronounced in his later years.

(#litres_trial_promo) He would return home from work, listen to the news, fidget and then put on his coat and slip away to the local pub.

(#litres_trial_promo) Indeed, Trimble’s earliest recollection of his drinking habit was, at the age of six or seven, of finding beer bottles under the kitchen sink – though, fortunately, there were no great public embarrassments nor huge rows in the parental home.

(#litres_trial_promo) Rather, Iain Trimble recalls, he was simply not there for much of the time.

(#litres_trial_promo) More obviously problematic was Billy Trimble’s decision to become a guarantor of a loan on behalf of an associate, which then went wrong. In 1960, the ensuing financial difficulties forced Billy Trimble to sell the semi-detached house which he had built himself with a neighbour at 109 Victoria Road, Bangor, and move a short distance up the hill to rented accommodation in a grander Victorian villa at 39 Clifton Road.

Trimble inherited his looks and his argumentative nature from his father. But, he says, they were perhaps too alike to be really close. ‘Like a lot of Ulster Protestant males, Father was emotionally illiterate,’ recalls Trimble. ‘He told me I was “handless” [clumsy and uncoordinated], which was true, but telling you as much doesn’t help.’ Efforts by his father to interest him in football by taking him to Bangor FC matches were also unsuccessful.

(#litres_trial_promo) But he bequeathed his son one hobby: music. Not only was classical music always around the house, but Billy Trimble was also a prominent member of the chorus of the Ulster Operatic Company, performing in productions of such Gilbert and Sullivan operettas as Trial by Jury and Patience. David Trimble also did some acting at school – playing the part of Stanley in Richard III – and later for the Bangor Drama Society: he says that these performances probably did as much as anything to increase his self-confidence. During the 1980s, as chairman of the Ulster Society, he also put on several productions of the plays of St John Ervine, the Ulster writer and dramatist. Although Trimble is no singer, and does not play any instrument, music remains his greatest enthusiasm and the family drawing room bulges with several thousands of albums. His first love was Elvis Presley; later, he graduated to Puccini, Verdi and Wagner (his particular favourite). Indeed, in times of crisis, says Daphne Trimble, such as after the setting up of the first inclusive Northern Ireland Executive in late 1999, he will turn to his records for solace.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Trimble’s relations with his mother were not very good, either. From her, too, he encountered a measure of coldness – the origins of which may owe something to the infant David’s error of throwing her engagement ring into the fire.

(#litres_trial_promo) Whatever the reality of their relationship, Ivy Trimble was the dominant personality within the household. She was also determined to maintain appearances and became a pillar of suburban society, both as chairman of the Women’s Institute in Bangor and of the ‘B&P’ (or the Business and Professional Club). David Montgomery – who later became an important Trimble ally as Chief Executive of Mirror Group Newspapers which owned the News Letter and who grew up 100 yards away from the Trimble family – recalls that they ‘epitomised the Ballyholme-Shandon Drive society and were much more visibly upmarket than we were’.

(#litres_trial_promo) If so, it was relative privilege, for when Trimble entered Ballyholme Primary School, he was conscious of residing outside that catchment area and of coming from slightly the wrong side of the tracks. He may not have wanted for any essentials, but his home could not be said to have been ‘earth’s recurring paradise’ – to quote Tennyson’s poem ‘Helen’s Tower’, about the folly built near Bangor by the First Marquess of Dufferin and Ava.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The Trimble household could not, in the old Ulster phrase, be described as especially ‘good living’ – in the sense that alcohol, smoking and theatregoing were obviously indulged. Likewise, profane music and books were allowed on Sundays.

(#litres_trial_promo) But certain traditional practices and forms were nonetheless observed. The family worshipped at Trinity Second Presbyterian Congregation of Bangor, whose minister John T. Carson had written several volumes, including a school story entitled Presbyterian and Proud Of It and God’s River In Spate, a study of the 1859 religious awakening known as the Year of Grace; in 1966, he was called to the Moderatorial Chair of the General Assembly. Carson was in the forefront of the moderate evangelicalism of the Presbyterian Church in Ireland in the post-war era and Trimble was an enthusiastic congregant from his teenaged years through to his mid-twenties. Between the ages of eleven and fourteen, Trimble spent part of several Christmas holidays at the interdenominational Belfast Bible College and attended morning and evening services every Sunday and at midweek, as well as special services: according to Iain Trimble, he was undoubtedly the most observant member of the family.

(#litres_trial_promo) He was also ‘headhunted’ for a variety of tasks by the kirk authorities, of whom the most influential was Michael Brunyate, an Englishman who worked as an engineer at Harland and Wolff. Trinity wanted to attract more holidaymakers to its services and to that end, the young Trimble assisted Brunyate in rigging up the sound system to blare out hymns on Main Street: because of copyright problems, they had to pre-record their own devotional music.

(#litres_trial_promo) But this was not just a pastime for an awkward, bookish teenager: Trimble recalls that he was a genuine ‘fundamentalist’, asserting the literal truth of the Bible. Moreover, he was a ‘creationist’ – in the sense of believing it to be an accurate description of the order in which God created the world, though he always entertained doubts about the precise six-day timespan (he remains doubtful about Darwinian evolutionary theory to this day, but on intellectual rather than theological grounds). He would continue to be an ardent church-goer until the late sixties – though he declines to say why he stopped, on the grounds that it would be ‘too complex’ to explain.

(#litres_trial_promo) Notwithstanding his often excellent memory, he would make a reluctant, even poor witness for the likes of Anthony Clare.

Perhaps because of the uneasy relationship with his parents, and his lack of coordination, Trimble was thrown back on his own resources at an early age. This self-sufficiency took both intellectual and emotional forms. Certainly, books were the safest refuge of all from family and contemporaries alike. His siblings recall him poring endlessly over war adventure stories: his brother Iain recalls that young David would read by candlelight after his parents switched off the lights at 9:00 p.m.

(#litres_trial_promo) Later, he moved on to Winston Churchill’s The Unknown War, about the eastern front during the First World War, and delighted in mastering the geography and history of the obscure countries described in that volume. Yet for many years, Trimble’s knowledge of the outside world was largely derived from books. Despite his curiosity, he never holidayed overseas – apart from a couple of school-trips to Austria and Germany – until he married Daphne Orr in 1978. His parents could afford only cycling holidays in the Mourne Mountains or the Trossachs, where the entire family would stay in youth hostels.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Such mastery of detail may have been entirely theoretical, but it served Trimble well in his own home. He established his pre-eminence in the house as much through a natural ability with words and his excellent memory, as through physical force. ‘You could never argue with David because he always retained any information,’ recalls Iain Trimble, who left home at fifteen to join the RAF as an apprentice photographer. ‘He would always know more than you did. Which was quite frustrating. But it had the effect on me that if David said something, I’d believe it.’ Whether the issue at hand was the Munich air disaster of 1958, the Floyd Patterson – Ingemar Johansson fight, or Elvis Presley, the young Trimble acquired an encyclopaedic mastery of the details.

(#litres_trial_promo) Trimble is often called an intellectual snob, but this is not quite right: he could more accurately be described as a knowledge snob, whatever the subject. Even today, notes Daphne Trimble, ‘he can be quite happy spending the evening at home reading, without exchanging a word with anybody in the family’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Such traits and interests set Trimble apart from his contemporaries at an early age – first at the Central Primary, then at Ballyholme Primary. In consequence, Trimble’s mother entertained hopes that he might attend Campbell College (one of Northern Ireland’s leading independent schools). Such aspirations were short-lived – especially after his father pointed out that they could not afford travel costs, let alone the fees. But he passed the 11-plus – the only one of the three Trimble children to do so – and in the autumn of 1956 he began at Bangor Grammar. Located within 100 yards of home, at College Avenue, it was an all-boys school of 350–400 pupils. Following his successful interview in June of that year, the headmaster, Randall Clarke – a former housemaster at Campbell College – wrote at the time that the young Trimble was possessed of good speech and manners. In appearance, he was neat and red-headed. He added that he was ‘over-studious and over-conscientious. Nice child. Highly intelligent. Precocious.’ He wondered: ‘Has he been pushed too much?’

(#litres_trial_promo)

The remark may have said something about the Trimble household, but it also said something about the prevailing ethos of Bangor Grammar: Jim Driscoll, who came to Bangor Grammar from Ballymena Academy in 1952 to teach Classics, found that ‘to a certain extent, it reflected the tone of a holiday town’.

(#litres_trial_promo) This, of course, is precisely what it was. Bangor, known in the 19th century as ‘the Brighton of the North’, was a quiet seaside resort of faded grandeur; some of the older people then had never even been to Belfast. True, Bangor Abbey, founded in 558 by St Comgall, had been one the centres of learning in medieval Europe – which explains why the spot is one of only four places in Ireland referred to in the late twelfth-century Mappa Mundi.

(#litres_trial_promo) By the 1950s any such academic distinction was mostly a thing of the past and university entrants, let alone Oxbridge awards, were then comparatively rare. But such qualifications were not really needed: higher education was the exception rather than the norm and, as Jim Driscoll recalls, most school-leavers had little difficulty in finding jobs.

(#litres_trial_promo) Its proudest achievements were in sports and to this day, two of the most celebrated Old Bangorians are still Dick Milliken, the former British Lion, and Terry Neill, the football player and manager. Nor does the school appear to make much of its other famous politicians: one was H.M. Pollock, the first Finance Minister of Northern Ireland, and the other was Brian Faulkner, who attended Bangor Grammar briefly before completing his education at St Columba’s in Dublin. Faulkner was the last Unionist politician who attempted an ‘historic compromise’ with Irish nationalism in 1973–4, and destroyed himself politically in the process.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Bangor and its Grammar School were also socially ambitious – as was implied by the school song, Floreat Bangoria, adopted in conscious imitation of the Eton motto Floreat Etona. Indeed, class, rather than religious sectarianism, was the sharp dividing line in this overwhelmingly Protestant town. Although the Catholic Church was on the periphery of town (the three Presbyterian and two Church of Ireland houses of worship were conspicuously in the centre) there was no such thing as a ‘ghetto’. Indeed, a few Catholics were to be found amongst both staff and pupils of Bangor Grammar and the two ‘communities’ socialised quite freely. Nor did Ivy Trimble have any objection to her sons associating with Catholic boys, provided they came from the ‘right’ sort of background, such as Terry Higgins and his brother Malachy (now Mr Justice Higgins); another Catholic friend was Derek Davis, later a BBC Northern Ireland and RTE presenter. Ivy Trimble’s prejudices were not untypical of the time, and David Montgomery recalls that his mother shared the same attitude to contact with Catholics.

(#litres_trial_promo) If most of Trimble’s friends were Protestants, it was simply because they formed the bulk of the population – but, recalls Terry Higgins, that applied equally to Catholic boys such as himself.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Bangor Grammar’s cocktail of physical hardiness, social snobbery and academic mediocrity did not appeal to Trimble. Moreover, he disliked Randall Clarke personally. ‘He treated me like a remedial pupil,’ Trimble recalls.

(#litres_trial_promo) So uncongenial did Trimble find Bangor Grammar that he now regards his main achievement as avoiding sports for two years. Certainly, he was an academic late-developer, only really coming into his own when he began his legal studies at Queen’s. But neither was he a disaster, as some of his own recollections imply. The programme for the 1963 Speech Day shows that he won first prize in Ancient History and second prize in Geography and Latin. Still, he received no particular encouragement from Clarke to go to university. Certainly, many of Trimble’s reports are replete with references to his ‘carelessness’ – something to which he was prone when not interested in the matter at hand. In his final term, in 1963, Clarke commented: ‘This boy has a lively mind which sometimes leads him into irrelevance which can be disastrous in examination conditions.’

Trimble’s teachers now remember a nervous, highly-strung boy who was a bit of a loner. He does not disagree: his friends were so few in number that he cannot recall the names of many of those with whom he was at school.

(#litres_trial_promo) It is, therefore, curious that the swottish and ‘handless’ Trimble was never bullied. Perhaps it was because there was something forbidding about him. Family and friends recall a terribly serious and pencil-thin Buddy Holly lookalike, who could walk straight past any number of friends and acquaintances with the most tightly rolled-up umbrella anyone had ever seen.

(#litres_trial_promo) ‘The only way in which David was extreme was in his music and his reading,’ his closest school-friend, Martin Mawhinney now says.

(#litres_trial_promo) Trimble first heard Elvis’ ‘All Shook Up’ in the amusement arcades of Bangor in 1957 and never looked back. Once, he and his friends went to three Presley films in a day: they began with Loving You at the now-demolished Tonic Cinema in Bangor (with its great Hammond organ which would emerge from the floor during the interval); then to Newtownards to see Jailhouse Rock; the ‘treble bill’ would then be rounded off in a Belfast cinema. He acquired a Rover 90 for £50; and he taught himself how to drive it from the handbook. As a result, he crashed into a lamp-post on his first outing and did not drive again until he was into his 40s.

Trimble’s recollections of an uneven academic performance may have owed something to his growing commitment to 825 Squadron of the Air Training Corps – the Bangor area ‘feeder’ for RAF ground crews (indeed, according to school records, Trimble indicated upon entry into Bangor Grammar that he wanted to go into the RAF). Leslie Cree, an older boy who was already a Warrant Officer in the ATC, recalls that ‘in the early days we reckoned he was a wee bit of a boffin’, with little sense of humour. But in fulfilling his tasks assiduously – which included shooting competitions with the local sub-division of the Ulster Special Constabulary, or ‘B’ Specials – Trimble earned respect. Cree thinks it helps explain why he was never bullied.

(#litres_trial_promo) To this day, Trimble recalls with pleasure his low-flying experiences in England, hedge-hopping in a Chipmunk. It was also an institution where sectarian tensions were not high: Trimble was much impressed when one recruit personally gathered up his fellow Roman Catholic cadets and took them off to Mass in Bangor in full uniform before heading off to the parade ground.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The ATC was significant to Trimble in social terms. As Cree points out ‘he gradually became more acceptable and part of the human race’. Moreover, he had taken risks – such as a near crash landing at RAF Bishopscourt near Downpatrick – and actually enjoyed it. But its effects were more long-term. It was through the ATC that Trimble made the contacts which led him into the Orange Order and ultimately into politics. Although Trimble had been promoted to corporal in 1962, his poor eyesight meant he could never take up a career even in the ground crews. Those who were not going to enter the RAF had to leave the ATC by 18. Many, including Leslie Cree, went from the ATC into the ‘B’ Specials – then run by the district commandant, George Green, who later became an important figure in the hardline Vanguard party.

(#litres_trial_promo) But Trimble’s hand-eye coordination, though good enough with a .22 was less good with a .303, and potential entrants had to be proficient with both. How, then, would he stay in touch with his mates? The Orange Order provided at least a partial answer.

It was, nonetheless, a curious choice for Trimble in some ways. First of all, it obviously excluded his Catholic friends. Second, even in pre-Troubles Ulster – when the Order had a far larger middle-class membership – relatively few boys from Bangor Grammar joined up. As David Montgomery recalls, ‘Bangor had middle-class English pretensions and therefore the Orange Order would have been seen as a bit comic.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Third, neither of Trimble’s parents belonged to it and his father’s unionism amounted to little more than raising a Union flag on 12 July and putting up election posters for the local MP in the provincial Parliament, Dr Robert Nixon, who was also the family GP. Fourth, Orangeism in Bangor was shaped by the Church of Ireland and Trimble was, of course, a Presbyterian. Indeed, Cree, who was then a member of the Church of Ireland, recalls that it was no easy matter to persuade Trimble to join: Trimble gave a stirring defence of the ‘Blackmouth’, or the cause of the Dissenters. But Cree showed Trimble that the Order brought all Protestant denominations together in defence of their civil and religious liberties, and he was duly sworn into Loyal Orange Lodge 726, otherwise known as ‘Bangor Abbey’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Founded in 1948 by members of the Abbey Church, it was a smallish Lodge, 30 to 45 strong. Membership was in that period 60 to 70% Church of Ireland; it is still around 40% ‘Anglican’, as it were. It was a classless cross-section of society composed, amongst others, of civil servants, butchers and gas fitters. Unusually for a Lodge, it had no Orange Hall, meeting instead on Church premises. Trimble did not then know much about Orange culture, but he rapidly mastered its ‘Constitution, Law and Ordinances’, and for a period became Lodge Treasurer. In these early days, he attended every one of the Lodge’s six or seven parades that were held each year.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The mildness of Bangor Orangeism of the era may also owe something to the fact that it was quite untouched during the IRA Border campaign of 1956 to 1962. Indeed, Cree remembers that Trimble and his friends were utterly shocked when a Republican slogan was painted on an advertising hoarding in Hamilton Road, Bangor. Indeed, so solid and secure was the world of Bangor Orangeism that the word ‘Loyalism’ would not even have been understood, at least in its contemporary sense, back then. That was only to come to the area with the onset of the Troubles, when housing clearances brought former residents of the Shankill and east Belfast to new estates in Breezemount and Kilcooley: the paramilitary influences came with some of them. Everything was assumed, and the world-view of the area can best be summed up by the genteel, stock phrase to be found in obituaries of the time in the County Down Spectator – ‘a staunch Unionist in politics’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

It makes Trimble’s subsequent flirtation with the more robust elements in Orangeism – above all, at Drumcree – all the more curious. LOL 726 did go as a whole to show solidarity with their brethren during the first ‘Siege of Drumcree’ in 1995, which helped to propel Trimble to the Ulster Unionist Party leadership, but not in subsequent years. Indeed, he only joined the Royal Black Preceptory, the senior organisation within the Orange family, in the early 1990s at the behest of constituents in Lurgan (his lodge is RBP 207 or ‘Sons of Joseph’). This was after declining earlier offers from lodges in Bangor to join ‘the Black’. In other words, he did so as an act of duty as much as out of a desire to participate regularly in its activities. Indeed, by 1972, Trimble had dropped out from regular attendance at meetings of LOL 726. Partly, it was a question of professional commitments: Trimble believes that one of the problems with the Loyal Orders over many decades has been that instead of focusing on the great political questions ahead of them, they have devoted their energies to the rituals of Orange life with its incessant round of quasi-Masonic meetings and social gatherings.

(#litres_trial_promo) Certainly, it was impossible to envisage him seeking higher office either in the District or the County Grand Lodge – in contrast, say, to his parliamentary colleague, Rev. Martin Smyth or John Miller Andrews, Northern Ireland’s second Prime Minister, in retirement.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Such concerns were far removed from the mind of the young Trimble as he contemplated his future in his last year at school. Quite apart from the discouraging noises which emerged from Randall Clarke, his father did not believe he could afford to go to university and tried to interest him in the Provincial Bank, later amalgamated with other institutions into the Allied Irish Bank. Billy Trimble had passed the Queen’s University matriculation aged sixteen, but he could not afford to attend: his son wonders whether paternal jealousy may have played a part in the counsel he gave (the contrast with the pleasure which David Trimble derived from his eldest child’s success in obtaining entry to Cambridge could not have been greater).

(#litres_trial_promo) There was also the fear of rising unemployment, which seemed high by the standards of the time, though it was low compared to later jobless rates. Consequently, Trimble opted for security. He saw an advert to join the Northern Ireland Civil Service (NICS) and was admitted on the basis of his surprisingly good ‘A’ Level results. In the following September, he was posted as a Clerk to the General Register Office at Fermanagh House in Belfast, compiling the weekly bulletin which recorded births and deaths.

(#litres_trial_promo) Like his father before him, Trimble seemed destined for a life of comparative anonymity.

TWO A don is born (#ulink_69e0334a-b4e5-55dd-87e2-cb4515e121db)

TRIMBLE duly began his career in the NICS in September 1963, on a monthly salary of £35. He was rapidly transferred to the Land Registry – tucked away at the Royal Courts of Justice in Chichester Street, because it had originally been part of the Courts Service. The Northern Ireland Government, however, seemed most of the time to have forgotten the existence of this Dickensian backwater: a musty, overcrowded warren of rooms with high windows. It was primarily a place where paper was stored and when ancient title deeds would be brought out from the bowels of the registry, the member of staff would often find his clothing covered in dust. When a property transaction occurred, a change in the entry of ownership was required in the relevant folio; Trimble’s job was to make a draft of the new entry. But the drudgery had a purpose. Transfer to the Land Registry afforded access to the NICS’s scheme for recruiting lawyers. Under this programme, civil servants could study part-time for a law degree at Queen’s University Belfast, whilst continuing their professional tasks, and then return at a higher grade.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Tempting as the prospect was, Trimble asked himself whether he would be up to the task. After all, no Trimble had ever been to university. Queen’s was then the only fully-fledged university in the Province and the most solid of redbrick foundations. It had been founded as Queen’s College after the passage of the Irish Universities Act of 1845 as part of Sir Robert Peel’s reforms. Hitherto, the Ascendancy had dominated higher education, as embodied by Trinity College Dublin. But the burgeoning middle classes, Catholic and Dissenter alike, demanded something more. Three such institutions were set up. Two of them, at Cork and Galway, were intended to serve the predominantly Catholic population of the south and the west and one, in Belfast, was to serve the overwhelmingly non-conformist population of the north-east. As such, it heavily reflected the Presbyterian ethos.

(#litres_trial_promo) Although there was still a residual sense amongst Protestants, even in Trimble’s time, that this was ‘our University’, he was initially hesitant about applying. The competition was stiff, and when the NICS scheme was pioneered in the previous year only two out of the 300 applicants had made it. But Michael Brunyate, who was still one of the greatest influences on Trimble’s life, persuaded him that he would never be happy within himself if he did not obtain a degree.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Trimble applied, and managed to win one of two NICS places for 1964: the other went to Herb Wallace, a friend and colleague from the Land Registry who would later hold a Professorial chair and serve as Vice Chairman of the Police Authority. Wallace initially thought the pencil-thin, ginger-haired, red-faced youth was ‘a bit odd’; but they were soon to become firm friends. Again, like Trimble’s family and school contemporaries, Wallace was impressed by his knowledge and authority, especially when it came to current affairs. Trimble was already a critic of Terence O’Neill, the mildly liberal Prime Minister of Northern Ireland from 1963 to 1969, as much because of his unattractive and haughty manner as because of his policies. Wallace recalls that Trimble then regarded Ian Paisley, who was starting to make waves in opposition to O’Neill’s policies, as a crank.

(#litres_trial_promo) Instead, he admired the two most dynamic figures in the Provincial Government: William Craig, the Development Minister, and Brian Faulkner, the Commerce Minister. He considered them both to be ‘doers’. Trimble, who was irritated by the parochialism of the Northern Ireland news, was more stimulated by events further afield. During the General Election of 1964, he loathed Harold Wilson, identifying more with Sir Alec Douglas-Home; he was passionately interested in Rhodesian UDI and ardently backed the United States over Vietnam. He was also influenced in his opinion of the Cold War by the London-based monthly journal of culture and politics, Encounter, in which contributors often urged a tough line on the Soviets.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Queen’s Law Faculty was then still very much in its ‘golden epoch’. Along with Medicine, it had always been the most prestigious of the University departments and enjoyed an intimate relationship with the Provincial Bar and Judiciary. Places were specially set aside for law students in the library, who then underwent a four-year course. The student numbers, though they had increased substantially since the 1950s, were still very small compared to today – around 40 in each year. It was also a place where Catholic and Protestant undergraduates mixed relatively easily. But what made Queen’s outstanding in this epoch was the quality of the teaching staff. They included colleagues such as William Twining, later Professor at University College London; Claire Palley, who taught Family and Roman Law and later became Principal of St Anne’s College Oxford; Lee Sheridan, later Professor of Law at University College Cardiff; and Harry Calvert, a Yorkshireman who had written what was then the definitive text on the Northern Ireland Constitution.

(#litres_trial_promo) Moreover, these academic grandees set the most demanding of standards: some years could go by when no ‘firsts’ were awarded, and even ‘2:1s’ would be dispensed sparingly enough; many would fail their first-year exams.

Yet although Trimble was only a part-timer, he flourished. Indeed, in some ways, he rather resembled the young Edward Heath, whose life only really ‘began’ after he left his small-town grammar school and went up to Oxford.

(#litres_trial_promo) Oddly, perhaps, in the light of Trimble’s dislike of the work of the Land Registry, he particularly enjoyed Property Law and its bizarre algebraic logic, which he took in the final two years: but, unlike other ‘swots’, recalls Herb Wallace, he was always very generous about sharing his copious lecture notes.

(#litres_trial_promo) So absorbing did he find the work that he began to attend less to duties in the Land Registry and in his final year took leave of absence.

(#litres_trial_promo) Queen’s, however, spotted his academic potential and in his fourth year William Twining informed him that he ought to consider taking up a teaching post – subject to his obtaining the right result. Trimble took an outstanding first in his Finals that summer and won the McKane Medal for Jurisprudence. On the basis of that achievement, he was offered an assistant lecturership in Land Law and Equity, with a starting salary of £1,100 per annum. The front page of the County Down Spectator of 5 July 1968 pictured him on the front page and claimed with pride that the local boy was the only Queen’s student to take a first for three years. But his graduation was marred by the death of his father the night before the ceremony. In his will, Billy Trimble left an estate worth £3078.

Why did Trimble opt to become a lecturer? He also loved Planning Law and easily had the intellectual ability to become, in due course, a well-paid silk in London (indeed, he was called to the Northern Ireland Bar in 1969 and by Gray’s Inn in 1970: two of his fellow pupils in the bar finals included Claire Palley and the late Jeffrey Foote, subsequently a leading QC and County Court Judge). Curiously, despite the small nature of society in Northern Ireland, he had few contacts at the Bar who would take him on as a pupil: his mother’s childhood friend from Londonderry, Lord Justice McVeigh, politely heard out Ivy Trimble’s representations on behalf of her son, but opened no doors for him. When eventually Trimble was called to the Bar, he was so lacking in contacts that his memorial had to be signed by a man who did not know him well, Robert Carswell, QC, subsequently Lord Chief Justice of Northern Ireland and a Law Lord (indeed, to this day, many practitioners of the law in Northern Ireland look down upon Trimble as not a ‘real’ lawyer). His decision to become an academic may also have had something to do with his shyness and awkwardness, which mattered less in the more arcane realms of Property Law than it would have in the more social atmosphere of the Bar Library (the Northern Ireland Bar operates a library system, inherited from the old Irish Bar, rather than Chambers). Above all, Trimble knew that any proceeds from a practice at the Bar would be some time in coming. Legal aid had been introduced in Northern Ireland only in 1966 and prior to the Troubles, the law was still a comparatively small profession. And he now had another reason to opt for financial security: he had met the local girl he wanted to marry.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Trimble had first encountered Heather McCombe from Donaghadee at the Land Registry. She was a plump and very popular girl; they were first spotted together at the office Christmas party of 1967. His friends and colleagues thought her a surprising choice. Not only was she outgoing where he was shy, but she was not obviously bookish. Nonetheless, they were married on 13 September 1968 at Donaghadee Parish Church with Martin Mawhinney as his best man; they honeymooned in Bray, Co. Wicklow – Trimble’s first visit to the Irish Republic (‘I had no idea how deeply unfashionable it was,’ he now recalls).

(#litres_trial_promo) On the proceeds of his work for the Supreme Court Rules Committee, he bought their first marital home at 11 Henderson Drive in Bangor. She soon became pregnant, and six months into her pregnancy went into premature labour. Trimble went to the hospital that evening, but did not appreciate fully what was happening and the medical staff told him to go home and to obtain some sleep. When he returned, twin sons had been born – but one had already died and the other was dying.

(#litres_trial_promo) Trimble went into shock and according to Iain Trimble, withdrew into himself.

(#litres_trial_promo) Subsequently, Heather Trimble became one of the first women to join the Ulster Defence Regiment, otherwise known as ‘Greenfinches’.

(#litres_trial_promo) It became an all-consuming passion for her and, indeed, many UDR marriages broke up in this period because of the highly demanding hours.

(#litres_trial_promo) The combination of their social and work commitments soon put the marriage under intolerable strain. The hearing was held before the Lord Chief Justice, Sir Robert Lowry, and the decree absolute was granted before Lord Justice McGonigal in 1976.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The unhappiness of Trimble’s domestic life contrasted sharply with the growing satisfaction which he derived from his professional duties in the Department of Property Law headed by Lee Sheridan. It was perhaps all the more remarkable because he never became part of the ‘in-set’ around Calvert and Sheridan who played bridge and squash. He has always felt an outsider, whether at Ballyholme Primary, Bangor Grammar, Queen’s, even in the Ulster Unionist Party. ‘In those years I was suffering from an inferiority complex,’ remembers Trimble. ‘Not because the people around me are English – though that’s a wee bit of it. No, it’s because the people around me are confident. I’m a bit unsure of myself. Francis Newark asked me if I played bridge. I felt uneasy about saying no, but at the same time I wasn’t going to learn it just to please him.’ Even today, he looks at himself and says: ‘It’s a curious thing: deep down inside I believe I’m very good but somehow I’m not always managing to reflect that in what I do.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Certainly, he was then unsophisticated. Claire Palley recalls how she and Trimble went to a French restaurant in the Strand after they completed their Bar exams: Trimble preferred the traditional British fare of steak and chips.

(#litres_trial_promo) The contrast with today’s Trimble – who has to order the most exotic items from the menu – could not be greater.

As throughout his life, Trimble gained self-confidence – and thus respect – by mastering his subject. His Chancery-type of mind, in contradistinction to the kind of horsedealing required at the criminal Bar, was perfectly suited to his dry-as-dust subjects. Students would often sense self-doubt in a lecturer, but Trimble kept order by asking questions which he knew nobody could answer. And when he himself then gave the response he would be able to cite the relevant case from his phenomenal memory and without referring to the textbook. Later, in judging moots, he would search on the Lexis Nexis database to check if there were any unreported decisions so he could pull the students up short; he hates nothing more than to be wrong-footed. Some, such as Alex Attwood – who became a prominent SDLP politician – thought him colourless; but as Attwood concedes, Trimble’s subjects were not necessarily those which would inspire someone imbued with great reforming or radical zeal.

(#litres_trial_promo) Others, such as Alban Maginness, who subsequently became the first SDLP Lord Mayor of Belfast, enjoyed his lectures.

(#litres_trial_promo) This was because he invested his subject with such enthusiasm, and would bound about his room waving his arms around. Another plus point for many students, recalls Judith Eve – later Dean of the Law School – was that Trimble was young and local.

(#litres_trial_promo) In 1971, he was promoted to Lecturer and in 1973 he was elected Assistant Dean of the Faculty, with responsibility for admissions. This appointment was a tribute to the impartiality with which he conducted his duties. Trimble later became a controversial figure in the University, but in this period his outside political activities were relatively low profile and in any case he was always assiduous in keeping his views out of the classroom (though that was easier when teaching subjects such as Property and Equity, rather than the thornier area of constitutional law). Few, if any, in this period thought twice that he conveyed the ’wrong image’ – least of all to have him go round schools of all kinds and denominations to extol the virtues of law as a career.

The effects of his term as Dean for admissions were significant. Only about 10 per cent of 500–600 hopefuls were accepted in this period. But according to Claire Palley, who regularly returned to Belfast, the percentage of Roman Catholic entrants rose markedly.

(#litres_trial_promo) Of course, this had little to do with Trimble, and owed far more to broader sociological circumstances. But this supposed ‘bigot’ did nothing to retard these developments and was renowned for meticulously sifting every application (only mature students did interviews). Indeed, so assiduous was he in discharging his responsibilities to students that when one of them was interned for alleged Republican sympathies, Trimble went down to Long Kesh to give him one-to-one tutorials; even at the height of the Troubles, he also regularly went to nationalist west Belfast to the Ballymurphy Welfare Rights Centre as part of a university scheme to help the underprivileged, taking the bus up the Falls to the Whiterock Road. And despite the subsequent growth of a highly litigious ‘grievance culture’, no one can remember any accusations of sectarian remarks, still less of discrimination; he was never subjected to a Fair Employment Commission case of any kind. This is why he was so vexed when Alex Attwood accused him of being distant towards nationalist students: Trimble would have been impartially cold towards all.

(#litres_trial_promo) ‘There was a level of reserve there, undoubtedly,’ remembers Alban Maginness. ‘It was fitting enough for a lecturer in the Law Faculty. He didn’t engage in simulated informality in a classroom context.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Nor, notes Claire Palley, a one-time colleague, was he any sort of misogynist – and he shared none of the condescending attitudes of some Ulster males towards female colleagues.

(#litres_trial_promo) The truth is that he is an old-fashioned meritocrat, who deplores the excesses of discrimination and anti-discrimination alike.

Trimble may have been the only member of the Orange Order on the Law Faculty staff, but that did not preclude good relationships with those colleagues who most certainly did not share his views (others were, of course, unionists with a lower case ‘u’, in the sense that they believed in the maintenance of the constitutional status quo, but were not Loyalists in the way that Trimble was). Thus, he enjoyed a good, bantering relationship with Kevin Boyle, a left-wing Catholic from Newry. Indeed, when his first marriage was breaking up, Trimble would even turn to Boyle for advice.

(#litres_trial_promo) Trimble’s best-known academic work, Northern Ireland Housing Law: The Public and Private Rented Sectors (SLS:1986), was written with Tom Hadden, a liberal Protestant, who also did not share his views.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Trimble and Hadden had also clashed at faculty meetings over the Fair Employment Agency’s attempt to review recruitment practices at Queen’s, when Trimble was one of the few with either the courage or the intellect to challenge the assumptions of that body.

(#litres_trial_promo) Moreover, whereas Trimble was a ‘black letter lawyer’, Hadden was very much more in the jurisprudential tradition. But for the purposes of this project, their complementary skills worked very well. Trimble was teaching housing law in the context of his property courses – such as how to sue landlords – and Hadden was covering the same terrain in the context of social policy. Trimble wrote three chapters, including those dealing with planning issues relating to clearance and development and technical landlord-tenant matters in the private sector (Northern Ireland’s housing then differed from that of the rest of the United Kingdom in having a substantial rented sector). It was an authoritative consolidation of this amalgam of the old Stormont legislation with the Orders in Council which came in with the introduction of direct rule from Westminster in 1972; and it vindicated the expectations of the publishers, SLS (run from the Queen’s Law Faculty), that it would be of use to practitioners, and sold its entire print run.

(#litres_trial_promo) So impartial was Trimble in the conduct of his duties that when eventually he did become involved in Ulster Vanguard, many of his colleagues were surprised: the first that David Moore knew of any political commitments on his part was when he saw Trimble on television during the 1973 Assembly elections.

(#litres_trial_promo) Events soon ensured that it would not turn out to be an image that he would sustain for long.

THREE In the Vanguard (#ulink_5815690d-b864-5dbb-8f16-ee64ef31a263)

‘I AM a product of the destruction of Stormont’, is David Trimble’s summation of his political genesis. On 24 March 1972, the British Prime Minister, Edward Heath, announced the prorogation of Northern Ireland’s Provincial Parliament and replaced it with direct rule from Westminster. The Troubles had already claimed 318 deaths, leading London to conclude that Ulster’s devolved system of government known by the shorthand of ‘Stormont’ was no longer the best way of kicking the issue of Northern Ireland ‘into touch’. Rather, as the Heath ministry saw it, Stormont was exacerbating the problem.

(#litres_trial_promo) Many Unionists, including Trimble, believed that Heath had tyrannically altered the terms of the 1920 constitutional settlement – which they had imagined could only be done by agreement with Stormont. Since then, one of the consistent aims of Trimble’s political life has been to undo the effects of this traumatic episode, by regaining local control over the affairs of the Province. His argument with Unionist critics of the 1998 Belfast Agreement centres on whether he has paid too high a price to attain that objective.

Why was this imposing edifice of Portland limestone, named after its location deep inside Protestant east Belfast, invested with such significance?

(#litres_trial_promo) Before the First World War, the Ulster Unionists had bitterly resisted devolved government to all of Ireland, otherwise known as ‘Home Rule’. They argued that it was little more than a halfway house to incorporation into an all-Ireland Republic, in which their liberties would endlessly be trampled upon by the island-wide Catholic majority. Led by Sir Edward Carson, they preferred to be governed like any other part of the United Kingdom from the Imperial Parliament at Westminster. But Lloyd George and the bulk of the British political class were not prepared to grant them this demand.

(#litres_trial_promo) Westminster had been convulsed for at least a generation by the affairs of Ireland and the parliamentary elites now wished to hold them at arm’s length. If possible, they also wished ultimately to reconcile the 26 (predominantly Catholic) southern counties with the six (heavily Protestant) northern counties. A permanently divided Ireland, many of the ruling elite calculated, could only be a recipe for further conflict and embarrasment in Britain’s backyard – and a possible strategic threat in time of war. Equally, an attempt to coerce Ulster into a united Ireland would also cause fighting and embarrassment.

Lloyd George, therefore, gave the Ulster Unionists a stark choice. He conceded that the six northern counties neither would nor could be coerced into a united Ireland. Ulster could ‘opt-out’ and run their own unique, semi-detached institutions of government – that is, Home Rule. The Ulster Unionists, who had never wanted this anomalous arrangement, now reluctantly accepted it in the changed circumstances. Many in London had at first envisaged it as only a temporary expedient, leading to eventual re-unification. But over time, the Unionists became comfortable with this settlement – maybe too comfortable for their own good. ‘A Protestant Parliament and a Protestant state’ was governed from 1922 by the Ulster Unionist Party: the phrase was coined in a debate on 24 April 1934 by Carson’s successor, Sir James Craig, the first Prime Minister of Northern Ireland. It was made in response to de Valera’s remarks about the Catholic nature of its southern counterpart (it was in the same speech that Craig also used another memorable phrase, ‘I have always said I am an Orangeman first and a politician and member of this Parliament afterwards’).

(#litres_trial_promo) Stormont thus came to be seen by the Ulster Unionists as their bulwark against a united Ireland. Or, more precisely, it was seen as a bulwark against potential British pressure to join such a state: the experiences of 1919 to 1921 had taught the Ulster Unionists that the liberties of this small group of British subjects could easily be sacrificed where broader British interests were deemed to be at stake. Ulster Unionists may have formed a majority in the six counties, but they were in a tiny minority in the United Kingdom as a whole. Stormont thus became the institutional expression of their wish to control their own destiny and the pace of change. Indeed, the famous Unionist slogan ‘Not an inch’ is an abbreviation of another of Sir James Craig’s pronouncements – ‘not an inch without the consent of the Parliament of Northern Ireland’.5

Despite the rocky beginnings of the Northern Ireland state, successive British Governments did pay for the post-1921 settlement because Lloyd George’s solution of ‘semi-detachment’ seemed to have worked. During Terence O’Neill’s modernisation programme in the mid-1960s, it even appeared that residual sectarian differences would be dramatically modified by the ‘white heat’ of new technology. While allegations of discrimination in housing and employment and gerrymandering of electoral boundaries were still raised from time to time by assorted British civil libertarians and Labour MPs with large Irish populations in their constituencies, the issue of Northern Ireland was never at the forefront of the public consciousness until the late 1960s. Even within Ulster itself, the future looked rosy: David Trimble first became interested in national and international politics precisely because he found the politics of the pre-Troubles Province to be so soporific. Unlike many of his Unionist peer group, such as Sir Reg Empey or David Burnside, he had neither joined the Young Unionists nor the Queen’s University Unionist Association. Indeed, some loyalist critics of the Belfast Agreement told me privately that Trimble’s apparent emergence from nowhere suggested that he was some kind of long-term plant of the British state inside the unionist community.

A simpler explanation is that times of upheaval bring improbable individuals to the fore. After 1968, the state of Northern Ireland was under relentless assault. The offensive came first from the Civil Rights movement, elements of which successfully portrayed Stormont as little more than a discriminatory instrument of Protestant hegemony, and then from the resurgent IRA. Protestants, feeling their position under threat, retaliated. The exhausted RUC could not cope and regular British troops were dispatched during 1969 to aid the civil power. Three provincial Prime Ministers – Terence O’Neill, James Chichester-Clark and Brian Faulkner – resigned or were deposed in quick succession. Worse still from a Unionist viewpoint, many of the nationalist allegations of sectarian injustices and a repressive security system now found a sympathetic hearing in British official and journalistic circles. As long as Stormont ‘worked’ (in the sense of keeping things quiet) the British were happy enough to let it be. Once it was seen as a source of discontent and international embarrassment, the British cast around for less bothersome alternatives. The allegations against Stormont shaped one of the constants of British Government policy over a quarter-century: namely, that Unionists could never again be trusted with simple majority rule on the basis of the first-past-the-post electoral system. Henceforward, they would have to share power with representatives of the nationalist minority.

To a young man like Trimble, it all had a ‘disorienting effect. The established landmarks in one’s life were shifting and I did not know where it would lead to.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Trimble also disliked the way in which the British Army, which was accountable to central government, was introduced on to the streets of Northern Ireland in 1969. Like so many Loyalists, he felt it undermined the role of the old RUC and the locally raised militia called the Ulster Special Constabulary (or ‘B’ Specials), which were accountable to the Government of Northern Ireland.

(#litres_trial_promo) He did not, however, initially respond by becoming politically active. Indeed, his first experience of elections owed more to informal peer pressure within the Law Faculty than to any reaction to the collapse of public order. Trimble was approached by Harry Calvert: would he help his friend Basil McIvor, then running in the 1969 Northern Ireland General Election as the Ulster Unionist candidate for one of the newly created south Belfast constituencies? Trimble knew McIvor’s wife Jill, who worked in the Law Faculty. ‘Even at that time I had difficulty in saying no,’ recalls Trimble. ‘I find it embarrassing. If people are pressing me, it’s easy to say no, but if they ask nicely, it’s much harder.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

It was, at first glance, an unlikely pairing, for Basil McIvor was the most liberal of Unionists and a staunch ally of Terence O’Neill, Northern Ireland’s aloof, patrician Prime Minister.

(#litres_trial_promo) Moreover, he was one of very few UUP MPs elected to the old Stormont not to have been a member of the Orange Order.

(#litres_trial_promo) Trimble, by contrast, had always disliked O’Neill’s style and his increasingly flaccid response to the disturbances: he less minded O’Neill’s reforms than their timing, which he felt showed weakness and which could only encourage more violence. There was, however, another attraction in aiding McIvor. McIvor’s seat not only contained such unionist terrain as Larkfield, Finaghy and Dunmurry, but also included the adjacent, predominantly Catholic, area of Andersonstown: Trimble wanted to see what it was like and duly canvassed it. In February 1969, things were not yet so polarised as to preclude such an excursion and Trimble even received a good reception – so much so that he reckons that as many as 1000 to 1500 votes out of McIvor’s winning total came from Andersonstown (though some of these may have been cast by Protestants then still living in the area).

(#litres_trial_promo)

Subsequently, Trimble sought to join the UUP but received no reply to his letter of application. The inertia of party HQ at Glengall Street in central Belfast seemed to him to incarnate all that was wrong with the organisation of the time. Glengall Street had failed to provide a sustained or coherent intellectual response to the critique of the Northern Irish state advanced by the nationalists and their left-wing allies on the mainland.

(#litres_trial_promo) In consequence, says Trimble, ‘quite a few contemporaries tamely accepted this fashionable view of things – of a politically and morally corrupt establishment. There was a widespread view then of a poor, down-trodden minority. Those of the same age as me all went with the spirit of the times – Unionist Government bad, Civil Rights movement good. When things went pear-shaped, one gets the impression that the middle classes opted out of unionist politics altogether and headed for a safe port. They found it in the nice, uncontroversial New Ulster Movement and later in the Alliance party’. The reaction of one colleague from Queen’s was typical of the times: driving down the Shankill Road past Malvern Street, where an organisation styling itself as the ‘UVF’ had perpetrated a couple of grisly murders in 1966, his companion observed ‘ah, we’re passing your spiritual home’. Trimble was angered by the remark, but was not deterred. Indeed, the challenge of articulating a Unionist response also appealed to the counter-cyclical, even contrarian aspects of his nature: ‘My feeling that they were wrong was not entirely intellectual, it was in my bones as well. But it took me a couple of years to work things out. I usually do find myself uncomfortable with fashionable views and I have spent most of my life arguing against them.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Trimble, therefore, responded to the crisis in the only way he knew: he searched the stacks at Queen’s and read, read and read. There was a dearth of material. For although there had been some ‘Unionist’ historical writing during the Stormont years – such as St John Ervine’s biography of Sir James Craig, the first Prime Minister of Northern Ireland – there had been little Unionist political thought since the 1950s.