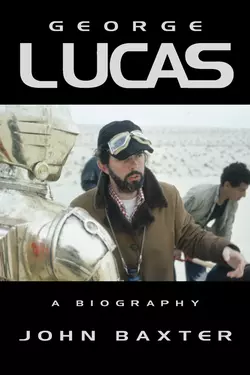

George Lucas: A Biography

John Baxter

The first major biography (since 1983) of the great movie mogul George Lucas, whose marketing techniques have transformed the film business. His fourth Star Wars film, The Phantom Menace, released in 1999, was perhaps the most eagerly awaited cinematic event of all time.George Lucas is one of the most innovative bigtime players on the movie scene. His three Star Wars films and the trio featuring the action hero Indiana Jones (all six of which Lucas conceived, produced and co-wrote) comprise the most popular group of films ever made. To finance them, he masterminded a revolutionary redrawing of the financial agreements under which films were produced in Hollywood, snatching away control of funding, intellectual content and the distribution of profits from studios, and placing them in the hands of the film-makers themselves.Yet Lucas remains (like Stanley Kubrick, the subject of John Baxter’s recent biography) an enigma and a recluse. He has specially built the Skywalker Ranch a long way from Hollywood – a Victorian village community in a redwood forest where he and his friends can work in splendid isolation, free of studio pressure but with the highest technology.

JOHN BAXTER

George Lucas

A BIOGRAPHY

DEDICATION (#ulink_662c7e9d-a44f-526e-8439-32a7f89793f4)

To Marie-Dominique Moveable feast

CONTENTS

Cover (#ufcda2bde-56e7-59e9-86f2-edc831776a5c)

Title Page (#uc9b771bc-67ab-5e3f-97cb-9ac2649325b9)

Dedication (#u0b17d76e-6765-5c08-8422-55f1191d8eec)

Epigraph (#ulink_b827cdfa-4357-57aa-8b61-f616face0f32)

1 The Emperor of the West (#ulink_bc5913f8-52fa-574a-9e23-f11d13e52e66)

2 Modesto (#ulink_cc7d7a69-e8a7-5e35-97d0-d8ed0305b2ce)

3 An American Boy (#ulink_16fcda55-a906-59c4-9f79-222d9da25d02)

4 Cars (#ulink_cd303bf9-1041-5d4d-a54d-2fee6f8c4780)

5 Where Were You in ’62? (#ulink_b5884a45-1e21-5800-9d49-0c953ad82489)

6 USC (#ulink_9422da21-d302-5296-b4ae-c6364974d91c)

7 Electronic Labyrinth (#ulink_90584683-7625-5ab0-8f5f-e09a2d57c5f4)

8 Big Boy Now (#ulink_209cc97e-14f6-5ab0-aa67-7d27e83313a6)

9 The March Up-Country (#ulink_a7427371-ef77-553d-94e7-e2262e60b65c)

10 American Graffiti (#ulink_8a354a2d-e667-5caa-9004-9af116283713)

11 The Road to the Stars (#litres_trial_promo)

12 I am a White Room (#litres_trial_promo)

13 For Sale: Universe, Once Used (#litres_trial_promo)

14 ‘Put Some More Light on the Dog’ (#litres_trial_promo)

15 Saving Star Wars (#litres_trial_promo)

16 Twerp Cinema (#litres_trial_promo)

17 Leaving Los Angeles (#litres_trial_promo)

18 Writing Raiders (#litres_trial_promo)

19 The Empire Strikes Back (#litres_trial_promo)

20 Raiders of the Lost Ark (#litres_trial_promo)

21 Fortress Lucas (#litres_trial_promo)

22 Snake Surprise (#litres_trial_promo)

23 Howard the Duck (#litres_trial_promo)

24 The Height of Failure (#litres_trial_promo)

25 Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (#litres_trial_promo)

26 Back to the Future (#litres_trial_promo)

Filmography (#litres_trial_promo)

Bibliography (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Notes (#litres_trial_promo)

By the Same Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

EPIGRAPH (#ulink_68082f1b-8f62-5f99-9c89-a7959fa71648)

There are times when reality becomes too complex for oral communication. But legend gives it a form by which it pervades the whole world.

The computer Alpha 60 in Alphaville, by Jean-Luc Godard

1 The Emperor of the West (#ulink_9c89ea0a-24e0-5dec-9766-4fc34925b4b6)

The Man in the Panama Hat (years older now) removes the Cross of Coronado from Indy’s belt.

PANAMA HAT: This is the second time I’ve had to reclaim my property from you.

INDY: That belongs in a museum.

PANAMA HAT: So do you.

From Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. Screenplay by Jeffrey Boam, from a story by Menno Meyjes and George Lucas

As he neared his sixtieth year, George Lucas sat in the shade on the red-brick patio of his home at Skywalker Ranch in Northern California and thought about destiny.

Almost without realizing it, he had become a legend – a man larger than life, magnified by his achievements, but dwarfed by them too. Over forty years, head down, brow furrowed, working every day and most of every night, ignoring discomfort and ill-health, banishing every distraction to the edge of his vision, he had created something remarkable. An empire. A fortune. A myth.

He was not a myth to himself. Only a megalomaniac takes his legend at face value. A sense of his ordinariness was part of the reason he’d succeeded. At first, the awe of his acolytes had puzzled him. Then he’d been amused, but irritated too; he’d been brought up to scorn self-advertisement and conceit.

But as one ages, adulation rests more comfortably on the shoulders. Occasionally, these days, he surrendered to the belief that perhaps he could really achieve anything on which he fixed his energy and instinct.

Other men, less able, less driven than he, paused before embarking on a project, and sometimes wondered, ‘Why am I doing this? What will be its effects, on me and on others?’ They pondered, worried, took advice.

In the beginning, Lucas had sometimes done that, but not lately. Myths don’t hesitate.

There was something presidential, even a touch imperial, in his certainty. Though it wasn’t something he confided to many people, he knew history. He’d read of Julius Caesar looking out on his empire and proclaiming, ‘I came, I saw, I conquered.’ He knew of Napoleon as a young officer surveying a world disordered by revolution and being seized by a vision of mankind united under a single rational mind. Above all, he understood Alexander the Great pausing at the end of his last campaign and weeping because there were no new worlds to conquer.

Yet he, a man less favored in his birth, less wealthy, less powerful, less educated, had achieved more than any of these men. He’d conquered not only this world, but other worlds besides. He was, in his way, master of the universe.

Or so his admirers said.

Was it true? He looked around for somebody to ask, and found only the smiling, alert faces of people anxious to do whatever he ordered, agree with whatever he said, set to work on anything he planned.

A legend is always alone.

On 4 July 1980, while Skywalker Ranch was still scrub and pasture, Lucas hosted his first cook-out on the site. There had been nothing much here in those days: just scrub, some cows, and a few deer which had become over the years the main reason for any stranger venturing this far north in Marin County. The spot where the grills were set up had once been occupied by banks of refrigerators to preserve the carcasses of game slaughtered by hunters.

Twenty-five years of construction and landscaping had transformed the old Bulltail Ranch. Anybody driving up from San Francisco along Route 101 and turning onto Lucas Valley Road at the exit marked ‘Nicasio’ found themselves passing through an expensive housing development, then twisting through an idyllic landscape of rivers and waterfalls. Discreetly, a shining wire fence paralleled the road, just out of sight in the woods. Signs every few yards warned that the fence was electrified – to keep in the deer and other livestock that roamed the estate, explained the custodians of the ranch, though everyone knew of George’s nervousness about strangers, and his fears of kidnap.

After eight miles, a sign so undemonstrative that you might well miss it unless you were looking led to a side road that wound through tall redwoods to a guardhouse. Security staff checked the visitors’ credentials against a list of people deemed persona non grata – ungrateful executives, sceptical critics, invasive journalists, technicians insufficiently respectful of Lucas or his managers. In one famous case, two special-effects technicians had been discovered after a cook-out, ‘drunk as skunks,’ according to one report, in that holy-of-holies, George’s private office. They joined the list of people ‘banned from the ranch’ – a phrase so much in currency within the effects community that one Los Angeles group took it as its business name.

Those who passed inspection were directed down the hill into the huge underground parking station, where their cars’ presence wouldn’t intrude on the rural calm. Any who remembered the ranch from the first cook-out didn’t recognise it now. A three-storied fin de siècle mansion clad in white clinker-built planks like a whaling ship, topped with shingled gables and fringed with wide verandahs, stared west across a wide artificial lake and landscaped grounds to a cluster of equally antique-looking buildings on the far side of the valley.

For centuries, European landowners had built ‘follies’ on their estates. One could have one’s own Roman ruins, with carefully shattered pillars, a picturesquely tumbled wall or two, some fragments of sculpture. Or a grotto in the Gothic style, its fountains decorated with old metalwork that might, if you didn’t look too closely, have been looted from some Etruscan tomb. Such buildings bought the owner an instant pedigree, an off-the-hook connection between a nouveau riche family and the ancient world.

Skywalker Ranch went one better. If anyone asked, staff recounted an invented history as carefully constructed as any screenplay. They were told that the property had been a monastery until a retired sea captain bought it in 1869. He built the Main House, which recalled the ‘cottages’ constructed on Newport, Rhode Island, by Vanderbilts and Whitneys at the turn of the century as summer retreats. The captain added a gatehouse the following year, and a stable. In 1880, he was supposed to have diversified into wine-making and built the large brick winery, which was given art moderne additions by a forward-looking descendant in 1934. In 1915, another innovative son erected a house spanning a brook on the estate, using the then-fashionable Arts and Crafts style pioneered by William Morris in the late nineteenth century. Later additions included the two-story library in polished redwood under a dome of art nouveau stained glass, its shelves housing a well-used and comprehensive reference collection.

On the other side of the valley, ‘unwanted relatives’ of the captain occupied conveniently remote guesthouses – named, in a lapse of historical authenticity, for Lucas’s cultural heroes: Orson Welles, John Huston, George Gershwin. After incidents like the encroachment of the drunken effects men, visitors only entered the main house by invitation. To get into the private compound around the Main House, you needed a coded key-card.

The illusion of old money was as meticulous as anything created in Hollywood at the height of its reconstructive powers in the 1940s. The Victorian-style double-hung windows and other fixtures were made in a workshop on the estate, which also maintained a studio for creating stained glass. The library’s well-rubbed redwood came from a demolished bridge in California’s Newport Beach, the books in its glassed cabinets from Paramount Pictures; they’d once been the studio’s reference library. The two thousand mature oaks, bays, and alders spotted around the 235 redeveloped acres of the ranch were trucked in from Oregon.

One visitor who opened a door marked ‘Staff Only’ found herself staring into a bunker filled with video surveillance equipment. Hidden cameras watched every corner of the estate; conduits snaking under the tranquil meadows carried enough electrical, telephone, and computer cables to feed a small town. The extent of the ranch’s electronics could faze even Lucas. In 1997, looking for a socket into which to plug a journalist’s tape recorder, he pulled up a corner of the carpet to reveal a tangle of wires. ‘So that’s what’s under there,’ he murmured.

In 1987, Lucas retained the San Francisco firm of Rudolph and Sletten to build a ‘winery.’ A red-brick two-story building with two large wings and an imposing central entrance leading to a three-story atrium with wooden galleries and a glass roof resembled other wine-making facilities in the area. In fact the building housed Skywalker Sound, 150,000 square feet of state-of-the-art post-production studios in the form of eight mixing stages. San Francisco’s avant-garde Kronos Quartet recorded here. So did the Grateful Dead, and singer Linda Ronstadt. The largest facility, Studio A, also known as the Stag Theater, replicated a high-style pastel art deco cinema of the thirties. Its ninety-six-track mixing console was twenty-four feet long, and on a film like Robert Redford’s The Horse Whisperer demanded eighty-five technicians.

Elsewhere on the ranch, what looked like a two-story barn held the negatives of Lucas’s films and the Lucas Archive. From 1983, Lucasfilm’s first archivist, David Craig, began photographing, documenting, and collecting the models, art-work – ten thousand items alone – costumes, story-boards and accumulated relics of the Lucas legend: ‘objects of artistic, cultural, and historical significance,’ according to the authorized catalog. Donald Bies became archivist in 1988, and helped plan the building, which opened in November 1991.

Lucas’s own office in the Main House held no hint of how he earned the money to build and maintain this empire. Friends like Steven Spielberg filled their offices with framed posters, awards, and signed photographs from presidents and box-office legends. Lucas displayed no souvenirs at all of his film career – no references to film at all, except for a pair of Disney bookends. Opposite his desk was a large painting of the enmeshed gears of a sixteenth-century clock. The artist, Walter Murch, a minor modernist of the thirties, was the father of Lucas’s close friend, also Walter Murch, who edited American Graffiti and with whom, rare for Lucas, he had remained close since they met at college. Elsewhere in the house hung originals by illustrator Maxfield Parrish and Saturday Evening Post cover artist Norman Rockwell, artist by appointment to those who, like Lucas and Spielberg, another Rockwell collector, yearned for the imagined certainties of American small-town life between the wars.

Downstairs, inside the front door, a few items, battered relics of Captain Lucas’s film-faring days, were displayed behind glass. They included Indiana Jones’s stained felt hat and whip; an ewok, one of the cuddly forest animals from Return of the Jedi, whom Lucas modeled on his then-two-year-old daughter Amanda; a heavily nicked light saber from Star Wars; and a creature from Willow. The case next to it was empty – for trophies of future triumphs? Or because reality has not kept pace with the growth of the illusion? Because, disguised by all this celebration of past triumphs was the puzzling fact that Lucas had not until 1999 actually directed a film in almost twenty years.

The one aspect of Lucas’s activities not relocated to Skywalker by the late nineties was Industrial Light and Magic, which still operated out of San Rafael, outside San Francisco. In 1988, Lucasfilm had opened negotiations with Marin County to develop more of the ranch as a production facility, and to move in ILM. When the supervisors bridled, Lucas offered to set aside most of the remaining thousand acres for ‘conservation,’ while continuing to own and patrol it. Meanwhile, he kept buying surrounding properties, though not without a fight from local farmers and the zoning authorities. By 1996, he owned 2500 acres and was negotiating for more.

The battle with his neighbors was typical of Lucas’s tentative hold on his retreat. In a quarter-century, more than the ranch had changed. Lucas was the second-largest employer in the county. Power calls to power; money draws money. Skywalker had become a focus for the hopes, ambitions, and needs of millions. There was magic in this place, but also greed, resentment, and fear.

Around dawn on any fourth of July during the mid-1990s, hundreds of people would have been on the road heading for Skywalker Ranch, and Lucas’s annual cook-out.

The first of them had flown up from Los Angeles on the early shuttle and collected rented cars at San Francisco airport – or been collected, if they had that kind of clout, as many did; there are some invitations that even the highest executives disregard at their peril.

Leaning back in their limos, the agents, producers, and stars skimmed Variety and Hollywood Reporter. It would be a long trip, and the headlines reminded them why they were making it. ‘Star Wars’ All-Time Boxoffice Force,’ shrilled Variety. ‘Lucas’ Series Paid off in Spades.’ The story spelled out the news, happy for their host, that the three Indiana Jones films he’d produced and helped write, the Star Wars trilogy he’d conceived and the first of which he’d written and directed, the TV series The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles, and the animated films in the series The Land Before Time were all making money.

So were his other enterprises. LucasArts Licensing was earning millions from franchising toys, clothes, drinks, candy, comic books, and games inspired by his films. One manufacturer alone, Galoob, would sell $120 million-worth of Star Wars toys that year, and the original licensee, Kenner, which still owned some rights, could also have survived comfortably on nothing but Star Wars light sabers, Imperial stormtrooper helmets, and models of Han Solo’s ship the Millennium Falcon and the series’ characters. ‘Since the first film came out,’ noted one report, ‘Star Wars merchandise sales have totaled more than $2.5 billion. It’s safe to say, in fact, that Star Wars single-handedly created the film-merchandising business.’ So expert was LucasArts Licensing that outside enterprises like the TV series Saturday Night Live and the environmental Sierra Club had become clients.

Industrial Light and Magic, founded by Lucas in suburban Los Angeles in 1975 to produce the special effects for Star Wars, was now worth $350 million, and had become the world’s premier provider of movie special effects. It created Jurassic Park’s dinosaurs and arranged for Tom Hanks to shake hands with Jack Kennedy in Forrest Gump. THX Sound, developed by Lucas engineers, was gaining ground in theaters across the world, and his recording complex, Skywalker Sound, had a reputation as the best in America. LucasArts Games, LucasArts Learning … Whatever George Lucas touched turned to gold. And the gold stuck to his fingers. No financial pages listed these companies. Lucas owned every share of stock himself.

That the staid Sierra Club trusted him with its merchandising wasn’t surprising. Lucas radiated probity – too much probity, thought some. Though the movie journal Millimetre lauded Lucasfilm as ‘a profitable multi-departmental corporation that defines the cutting edge of American film-making,’ the Boston Globe detected an omnipresent fogey-ism in its creations. A Lucas production, it wrote, ‘always seems to be about something like pre-war adventurers or pre-Vietnam teenagers or pre-television broadcasting. Even Star Wars is set in the far past, not the far future, and its style famously turned American movies back to old-fashioned (critics say old-hat) narrative strategies.’

Few of the people who distributed Lucasfilms’ products, worked on them, bought or sold their merchandise or otherwise derived a living from the group, had any such criticisms. True, British actress Jean Marsh, who played Queen Bavmorda in the fantasy Willow, did remark tartly that none of its actors relished being merchandised – ‘We would all pay not to be on the T-shirts and things’ – but she was in the minority. Most felt that, as long as it filled the coffers, Lucas could dramatize Pollyanna, or film Aesop’s Fables.

The cars took at least thirty minutes to skirt downtown San Francisco, cross the sweep of the Golden Gate Bridge, with giant tankers creeping out to sea so far below that they looked like models in a special-effects sequence, and climb the curve of the cliff onto Highway 101, the sole autoroute north into Marin County, and another world.

The social misfits and renegades who fled here in the late sixties, seeking to preserve the spirit of the Summer of Love from a San Francisco inhabited by panhandlers, dope addicts, porn-movie producers, and prostitutes, discovered a haven in old and sleepy towns like San Anselmo, San Rafael, Mill Valley, and Bonitas. Locals found themselves patronizing the hardware store along with long-haired, bearded men, ethereal-looking women in ground-brushing muslin, and barefoot babies. Teepees and geodesic domes mushroomed in the woods, fringed by private gardens of organic vegetables, with, just a few yards down the track, a patch of marijuana, exclusively for private use.

To the relief of locals, the newcomers weren’t particularly anxious to share their new lifestyle. When the town council of Bonitas, on the Pacific Coast, erected signs saying ‘Welcome to Bonitas,’ the hippies took them down. Most felt they already had just as many friends and neighbors as they needed. ‘The ideal in those days,’ said one refugee from the midwest who briefly settled there in the 1970s, ‘was a narrow road winding through the woods without any signs, and a little house at the end. I couldn’t stand it. That’s no way to live – without people. I moved to San Francisco.’

Sausalito, just across the Golden Gate, gave the first clue to Lucas’s guests that they’d moved into this new world. Once San Francisco’s yacht port, a cluster of boatyards and little dockside bars, its waterside warehouses now belonged to companies making models for movies, or sound designers like Ear Circus, the company of Randy Thom, who’d won an Oscar for the sound recording of Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now, and who’d worked too on Lucas’s ill-starred production Howard the Duck.

Thom, large, bear-like, and, like most of the people behind the scenes of special-effects films, shy and soft-spoken, was also on the road, heading north to the ranch. He’d had an office there while he was working on Howard the Duck, but after that he’d gradually moved away, until now he hardly visited the place. Like a lot of people who’d joined Lucasfilm in the heady days of its crusading energy, he’d made his own way. Except for Dennis Muren, now head of Industrial Light and Magic, none of the people who’d started ILM under John Dykstra still had jobs there. Nor did most of those who worked on Star Wars in other capacities.

Lucas’s wife Marcia had gone too, divorcing him in 1983. It surprised many people that the marriage had lasted so long. Marcia edited Lucas’s early films, and was good enough to be asked by Martin Scorsese to cut Alice Doesn’t Live Here Any More, Taxi Driver, and New York New York. In George’s conflicts with the studios and with Francis Coppola, she’d remained loyal, even when she didn’t share her husband’s obsession. Life with George was no picnic. The narrowness of his vision could be overpowering. ‘I heard this story,’ says Harley Cokeliss, second-unit director on The Empire Strikes Back, ‘that Marcia wanted a particular painting for her birthday. She dropped hints and dropped hints and dropped hints, until she was sure even George had got the message. On her birthday, he said, “I’ve got a nice surprise for you.” As Marcia looked around for her painting, George said, “I’m going to have the roof fixed.”’

John Milius was on the road, and wondering why he bothered. He and George went back longer than almost anyone. Before Star Wars, before American Graffiti and THX1138, back to 1963, when Lucas was a weedy, close-mouthed kid from upstate California, sitting through the same courses at the film school of the University of Southern California. In the famous malapropism of producer Samuel Goldwyn, they had all passed a lot of water since then – and, in Milius’s case, put on a lot of weight. Except that his beard was gray, George still looked the same. But then, he would probably look the same when another twenty years had passed.

Milius assumed that their oldest mutual friend Francis Coppola wouldn’t be at the cook-out. The excuse would be the standard one – he was on location on some film. But everyone knew that the two men were no longer close, and that, even though Coppola’s vineyards were only a twenty-minute drive from the ranch, George and he seldom saw one another. With Lucas, some rivalries never went away: ‘I bear grudges,’ he has said.

Coppola had led the move away from Los Angeles. His company American Zoetrope in San Francisco was meant to create a new Hollywood in Marin County. For a while after its collapse, Milius and the rest of the group half-believed that Lucas might pick up where Coppola left off. The mansion he and Marcia bought on Parkway in San Anselmo as headquarters for Lucasfilm might have been the beginning of an atelier, a collaborative film enterprise like Laterna, the Swedish studio-in-a-mansion which inspired Francis to found Zoetrope. But once Star Wars started earning, George bought the 1700-acre Bulltail Ranch. In 1979, he received planning permission to begin creating Skywalker.

The ranch, Lucas explained, would give him the freedom to make ‘my little films,’ abstract, experimental films that would ‘show emotions.’ Star Wars, he insisted, was only a means to an end. It would buy his way out of big-time cinema. He envisaged a ‘retreat [with] a rich Victorian character, [containing] film-research and special-effects facilities, art/writing rooms, screening rooms, film-editing areas, film libraries, a small guesthouse, and a recreation area complete with handball courts, tennis courts, and a swimming pool.’ His scheme would use only 5 percent of the land area, he said; the rest would remain agricultural.

But old friends like Gary Kurtz, Lucas’s one-time producer, watched with growing alarm as this vision metamorphosed into something closer to the private empire of Howard Hughes. ‘As the bureaucracy got bigger and bigger,’ says Kurtz, ‘George seemed to vacillate back and forth between wanting to control everything absolutely, make all the decisions himself, and being too busy to be bothered. He was busy working on his writing and other creative things, and he left his managers to deal with all that. Then he would come back in and want to be in control again, and that kept going back and forth a lot. Frustrating for a lot of people.’

That Lucas regarded the ranch as his monument became clear when, at the 1982 cook-out, a time capsule was ritually interred under the Main House, containing relics of what he hoped would become known as the Lucas Era. They included a microfilmed list of every member of the Star Wars Fan Club. He also called in Eric Westin, the designer of Disneyland, to manage the estate.

He hired helpers like Jane Bay. Once secretary to Mike Frankovich, head of Columbia pictures, and later assistant to Californian governor Jerry Brown, Bay was just the sort of management professional Lucas might have been expected to avoid. Shortly after, investment banker Charles Weber became president and chief operating officer of Lucasfilm. He imported studio veterans like Sidney Ganis as his deputies, driving out some of those who had been with Lucas through the long and painful gestation of Star Wars. Since then, Lucas had taken back control of the company, dispensing with Weber and appointing himself chairman of the board. ‘Critical observers feel, however,’ commented the Los Angeles Times tartly, ‘that if Lucas goes too far out of the Hollywood mainstream, he may end up chairman of the bored.’

These days, Lucas spent his days in a small house on the estate with his three adopted children, only visiting the Main House on semi-ceremonial occasions. Security at the ranch had increased. ‘The last thing we want,’ said Lucas in justification of the fencing and electronic surveillance, ‘is people driving up and down the road saying, “They made Star Wars here.”’ He hated being interviewed or photographed. ‘I am an ardent subscriber to the belief that people should own their own image,’ he said, ‘that you shouldn’t be allowed to take anybody’s picture without their permission. It’s not a matter of freedom of the press, because you can still write about people. You can still tell stories. It just means you can’t use their image, and if they want you to use their image, then they’ll give you permission.’

His public pronouncements had come to have overtones of the messianic. In 1981, breaking ground on the new USC Film School, to which he contributed $4.7 million, he lectured the audience on their moral shortcomings: ‘The influence of the Church, which used to be all-powerful, has been usurped by film. Films and television tell us the way we conduct our lives, what is right and wrong. There used to be a Ten Commandments that film had to follow, but now there are only a few remnants, like a hero doesn’t shoot anybody in the back. That makes it even more important that film-makers get exposed to the ethics of film.’

By 1 p.m., most of the guests had arrived and were assembled on the lawn in front of the Main House. At his first cook-out, in 1980, Lucas took the opportunity to hand bonuses to everyone who’d worked with him that year, down to the janitors. Actors and collaborators were given percentage points in his films, and he exchanged points with old friends like Steve Spielberg and John Milius. Overnight, actors like Sir Alec Guinness became millionaires.

There was nothing of that informality and generosity in the cook-out today. Replacing it was something closer to a royal garden party, or the rare personal appearance of a guru. Softly-spoken staff chivvied the guests into roped-off areas, leaving wide paths between.

‘George will be coming along these lanes,’ they explained. ‘You’ll have a good chance to see him. If you just move behind the ropes, and please stay in your designated area …’

Old friends exchanged significant glances; evidently George shunned physical contact as much as ever. Hollywood mythology also enshrines the moment when Marvin Davis, the ursine oilman who bought Twentieth Century-Fox in the eighties, met Lucas and, overcome with appreciation, picked him off his feet and hugged him. Lucas, it’s said, ‘turned red, white and blue.’

A moment after his acolytes had passed through the crowd, the host emerged onto the verandah of the Main House. Flanked by his trusted inner group, he moved to the top of the steps and stood expressionless just out of the early-afternoon sun.

It looked like the old George. Grayer, of course, and plumper, but still in the unvarying uniform of plaid shirt, jeans, and sneakers, draped over the same short body.

John Milius was a connoisseur of excess. He had penned Colonel Kilgore’s speech ‘I love the smell of napalm in the morning. It smells like … victory,’ in Apocalypse Now; Robert Shaw’s reminiscence in Jaws of the USS Philadelphia going down off Guadalcanal, and the slaughter of its survivors by sharks; the bombast of Arnold Schwarzenegger in Conan the Barbarian.

‘I remember one time I was with Steven and Harrison Ford,’ Milius recalled. ‘These people were coming around and saying, “You can be in this line, and you’ll be able to see George if you’re over here,” and moving us around.’

On that occasion, Milius’s mind had flashed to other examples of the cult of personality. Preacher Jim Jones in Guyana, for instance, and those shuddering TV images of bloated bodies fanning out from the galvanized washtubs from which they’d dipped up their last drink of sugar water and strychnine. ‘If George gets up there and starts offering Kool Aid,’ Milius muttered to Ford and Spielberg, ‘I’m bailing out.’

They all laughed, but nobody else around them was smiling. They were all staring with an almost hungry intensity as the frail man in the plaid shirt, jeans, and sneakers moved toward them.

2 Modesto (#ulink_70d1fda2-0496-502a-9034-957b89cf15ea)

If there is a bright centre to the universe, this is the place that’s furthest from it.

Luke Skywalker, on Tatooine, his home planet, in Star Wars

There is no easy way into Modesto – nor, for that matter, any easy way out.

Most people approach from the south, up Interstate 5, toughing out the flat emptiness of the San Joaquin, the ‘long valley’ John Steinbeck made famous in his stories of rural life in the twenties and thirties. Then, as now, this was fruit and vegetable country, the kitchen garden of California. Orchards, geometric patches of dense, dark foliage, interlock with fields of low, anonymous greenery which only a farmer would recognize as hiding potatoes, beets, beans. Occasionally, some town raises a banner against mediocrity – ‘Castroville, Artichoke Capital of the World!’ – but the norm is self-effacement, reticence, reserve.

Zigzagging among the fields, a great irrigation canal, wide as a highway, delivers water from lakes set back in the hills. No boats move on its surface, no kids fish from the concrete banks, no families picnic on its gravelled margins. This water, fenced off from the fields and the highway behind chain link, isn’t for leisure but, like everything else here, for use.

Modesto sits on almost the same parallel of latitude as San Francisco, but there any similarity ends. Californian or not, this is a Kansas town set down twelve hundred miles west. Even more than for most places in California, the people here are relative newcomers, migrants from the midwest and the south who fled the dust storms of the twenties and the farm foreclosures that followed.

Laid out flat as a rug on a landscape without a hill to its name, Modesto’s sprawl of ranch-style homes and flat-roofed single-story business buildings is divided as geometrically as Kansas City by a grid of streets, in turn cut arbitrarily by railway tracks. Splintered wooden trestles spanning gullies choked with weeds and the rusted hulks of Chevies and Buicks indicate the high tide of rail in the forties, but traffic still idles patiently at level crossings while hundred-car freight trains clank by.

A garage or a used-car lot seems to occupy every second corner – in farm country, anyone without a car might as well be naked – but one sees almost none of the Cadillacs, Porsches, even Volkswagens common in San Francisco and Los Angeles. Pick-ups, trucks and four-wheel drive vehicles predominate, many of them old but mostly well-tended. Cars here aren’t playthings or success symbols, but farm machinery.

In so flat a landscape, anything resembling a skyscraper looks like insane audacity. The town’s one modern hotel, the Red Lion, twenty stories tall and stark as a wheat silo, respects scale as little as a chair-leg planted in a model-train layout. Building the Red Lion broke Allen Grant, the overambitious Modesto businessman who financed it. Defaulting on his loans, he sold out to a chain. Locals recount this cautionary tale with implicit disapproval of his recklessness. In Modesto, it’s the horizontal man who’s respected, not the vertical one. If he wanted to erect something, why not a mall? When Grant used to race sports cars, his mechanic and co-driver was George Lucas.

Appropriately, Modesto’s monument to its most successful son barely lifts its head higher than George Lucas’s five feet six inches. At Five Points, where the narrow downtown streets coalesce into McHenry, a ribbon development of shopping malls and parking lots, a small wooded park next to an apartment block shelters two bronze figures. They loiter against the forequarter of a ’57 Chevy, they and the car both cast from metal with the color and buttery sheen of fudge sauce. Toffee-colored Jane perches on the fender, ankles crossed, absorbed in mahogany Dick who, earnestly turning towards her, describes his latest triumph on track or field – it’s implicit that nothing which happened in class could remotely interest this couple. What they most resemble is an image from the Star Wars trilogy: Han Solo, frozen in carbonite to provide a bas relief for the palace of Jabba the Hutt.

A slab of green marble set into the sidewalk and incised in gold footnotes the figures:

GEORGE LUCAS PLAZA

The movie remembrance of Modesto’s past, ‘American Graffiti,’ was created by the noted film-maker, George Lucas, a Modesto native and a member of the Thomas Downey High School Class of 1962. This bronze sculpture, created by Betty Salette, also entitled ‘American Graffiti,’ celebrates the genius of George Lucas and the youthful innocence and dreams of the 50s and 60s.

The ritual that inspired American Graffiti no longer takes place: large signs specifically indicate ‘No Cruising.’ In Lucas’s time, drivers circulated on Tenth and Eleventh Streets downtown, exploiting a one-way traffic system introduced by shopkeepers to facilitate business parking. Later, the Saturday-night paseo moved to McHenry, but it wasn’t the same. McDonald’s didn’t provide either telephones or public toilets, so cruisers congregated in the parking lots of shopping malls, fields of naked asphalt lit by towering lamp standards.

Without the sense of community it enjoyed downtown, cruising became a magnet for the area’s rowdies, especially on the second Saturday in June – high school graduation night. In 1988, Modesto’s city council belatedly caught up with its own bandwagon and formalized the June weekend bash as an American Graffiti festival. As many as 100,000 people converged on Modesto to line McHenry and watch the parade of ’32 Deuce Coupes and ’57 Chevies. Deejay Robert Weston Smith, aka Wolfman Jack, was master of ceremonies, an honor he enjoyed six more times, the last when he was Cruise Parade Marshal for the 1994 Graffiti USA Car Show and Street Festival. By then, night-time cruising had been banned after repeated problems with drinking and violence. The 1994 parade took place in mid-afternoon. Jack didn’t approve: ‘My favorite thing was the cruising and me being on the radio, and we don’t do that anymore,’ he said nostalgically. ‘Now they do it in the heat of the day with everyone roasting in their convertibles.’ He longed for the days ‘when the carbon monoxide was so thick you could hardly breathe.’

Meanwhile, Reno and Las Vegas, to the irritation of some Modestoans, launched what they called Hot August Nights, encouraging local owners of classic cars to cruise; and Roseburg, Oregon, launched an annual Graffiti Week. In Los Angeles, Wednesday night was Club Night on Van Nuys Boulevard, in the dormitory suburbs of the San Fernando Valley. After he made American Graffiti, Lucas enjoyed hanging out there. ‘It was just bumper to bumper. There must have been 100,000 kids down there,’ he said. ‘It was insane. I really loved it. I sat on my car hood all night and watched. The cars are all different now. Vans are the big thing. Everybody’s got a van, and you see all these weird decorated cars. Cruising is still a main thread in American culture.’ But by the late eighties, the Van Nuys ritual too had disappeared.

One isn’t surprised at Modesto banning the Cruise. Cruisers did not plant, nor cultivate, nor harvest. They were a plague, like locusts, and all the more loathed for being locally hatched. Most people in Modesto, if they were honest, would admit they were glad the gleaming cars, the horny guys and giggling girls, the throbbing exhausts and squealing tyres had moved on, taking their creator with them.

Future friends of Lucas like Steven Spielberg who, Angelenos to the heels of their fitted cowboy boots, joked about ‘Lucasland,’ which they visualized as a place of hot tubs, meditation, and marijuana, couldn’t imagine how little his birthplace resembled the satellite communities of San Francisco which furnished this fantasy. ‘Southern California ends at Carmel,’ any San Franciscan will tell you. ‘Once you get to Monterey, you’re in Northern California.’ And Modesto? ‘It’s neither. It’s the Valley.’ Their contempt is obvious, and Lucas shared it. When anyone in Los Angeles asked him where he came from, he said evasively, ‘Northern California.’

Nevertheless, the San Joaquin Valley put its stamp firmly on both Lucas and his films. Without the white upper-middle-class Methodist values he absorbed during his upbringing in this most complacent and righteous of regions, the Star Wars films, the Indiana Jones series, even the more eccentric THX1138, let alone American Graffiti, would have been very different. Indeed, they might not have existed at all, since Lucas, unlike the directors who joined him in building the New Hollywood in the sixties and seventies, is anything but a natural film-maker. Nothing in his character fits him to make films. The process irritates and bores him, even makes him physically ill.

Actors lament his failure to give them any guidance towards character. Harrison Ford, recalling the making of American Graffiti in Modesto, remembers staring for hours out of the windscreen of his car at the camera car towing it. ‘The cameraman, the sound man and the director could all sit in the trunk, and every time I looked at George, he was asleep.’ Cindy Williams, one of the film’s stars, was flattered when Lucas called her performance ‘Great! Terrific!’, until she found he said exactly the same thing to everyone.

It is easy to forget that Lucas, for all his fame and influence, has only directed four feature films in almost thirty years. Repeatedly he’s handed the job to others, supervising from the solitude of his home, controlling the shooting by proxy, as Hollywood studio producers of the forties did. As critic David Thomson remarks, ‘Lucas testifies to the principle that American films are produced, not directed.’

Martin Scorsese agrees that Lucas differs radically from both himself and others in New Hollywood, especially Spielberg. ‘Lucas became so powerful that he didn’t have to direct,’ he told Time magazine. ‘But directing is what Steven has to do.’ Spielberg agreed. ‘I love the work the way Patton loved the stink of battle.’

Lucas has less in common with Scorsese and Spielberg than with a producer like Sam Goldwyn, who fed the public taste for escapist fantasy and noble sentiment forty years before him, with films like Wuthering Heights, The Best Years of Our Lives and The Secret Life of Walter Mitty. As a young critic, the British director Lindsay Anderson met Goldwyn, and was impressed by his conviction that nobody knew better what his public wanted and needed. ‘Blessed with that divine confidence in the rightness (moral, aesthetic, commercial) of his own intuition,’ Goldwyn was, Anderson decided, one of the ‘lucky ones whose great hearts, shallow and commonplace as bedpans, beat in instinctive tune with the great heart of the public, who laugh as it likes to laugh, weep the sweet and easy tears that it likes to weep.’ Today, the grandchildren of Goldwyn’s audience laugh at Chewbacca the wookiee, cry at the love of Princess Leia for Han Solo, feel their hearts throb in tune to John Williams’s brassy score for Star Wars.

‘He came from a very practical era,’ the supervisor of Stanislaus County said of George Lucas Sr when he died in 1991. ‘There was never a day that I didn’t see George hailing me over. He’d be gesturing with his hands and pointing, and everyone knew that George was on the warpath with the government.’

The Lucases arrived in central California from Arkansas in 1890, after having left Virginia a century before. Before that, the family history is shadowy. ‘Nobody knows where we originally came from,’ George Jr said later. ‘Obviously some criminal, or somebody who got thrown out of England or France.’ The remark wasn’t made out of embarrassment. In a sort of reverse snobbery, his father had taught him that it was better to trace your roots to Billy the Kid than to the Mayflower.

In 1889, Washington and Montana achieved statehood, and California, with its orchards blossoming, its fishing industry thriving and oil being pumped along its central coast, looked like the place to be. Just before World War I, Walton Lucas, an oilfield worker, settled in Laton, a grim little town south of Fresno, where his son George Walton Lucas was born in 1913. George Walton Sr, the film-maker’s father, never lost the wiry look of a frontiersman, nor the sense, reinforced by Methodism, that life and work were two sides of the same coin. ‘He was one of those people who, at the dinner table, always had little talks about those kind of things,’ his daughter Kate recalled. ‘He quoted a lot of Shakespeare. “To thine own self be true.” He said a lot of things like that.’

In 1928, when George Sr was fifteen, his father died of diabetes, a disease whose gene would skip a generation and pass to his grandson. His widow Maud moved into Fresno, shuffling her son from school to school while she looked for work, a commodity in short supply as America’s economy imploded in the worldwide slump. In 1929 they relocated sixty miles from Fresno, to Modesto, and George enrolled in Modesto High School with the idea of studying law. Already convinced by events that the Lord only helped those who helped themselves, he was a serious student, becoming class president in his senior year. His vice president, who also co-starred with him in the senior-class play, was pretty, dark but frail Dorothy Bomberger, daughter of Paul S. Bomberger, a wealthy local businessman who’d built his father’s property interests into a large corporation that also included a seed company and a car dealership. They married in 1933, the year Lucas graduated. He was twenty, Dorothy eighteen.

With a wife to support, Lucas abandoned any thought of a law degree and found work in an old established Modesto stationery store, Lee Brothers. Shortly afterwards, one of the biggest stationery stores in the state, H.S. Crocker in Fresno, offered him a job at $75 a week. The couple moved, but Dorothy missed her family, so they returned to Modesto. With Dorothy’s father in real estate and her uncle Amos in loans, there was no problem finding a place to live. Lucas and Dorothy moved into an apartment repossessed from a defaulting borrower.

Lucas went to work for LeRoy Morris, who owned the town’s oldest stationery supplier, the L.M. Morris Co. Morris had been in business since 1904, and his shop showed it: school supplies and office materials shared space with books, gifts, and toys. With no children of his own, Morris was on the lookout for someone to whom he could hand on the thriving business. Lucas Sr wasn’t backward in making it clear he was a candidate.

‘This is the next-to-last move I plan to make,’ he told his boss. ‘By the time I’m twenty-five, I hope to have my own store.’

‘That’s a very ambitious goal,’ Morris said mildly.

But the young man’s directness had impressed Morris. Two years later he sought out Lucas in the basement where he was shifting boxes, and asked, ‘Are you satisfied with me?’

When Lucas looked blank, Morris continued, ‘If you are, I’m satisfied with you. Do you think we could live together for the rest of our lives? You know, a partnership is like getting married – maybe harder in some ways.’

‘But I have no money,’ Lucas said.

Morris shrugged this off. ‘You’ll sign a note you owe me so much. This business is no good if it won’t pay it out.’

Lucas switched from earning wages to owning 10 per cent of L.M. Morris. His employer’s generosity reinforced his belief in patriarchy. When he had a son, he would put him into the family business too, and help him run it until he was ready to take over.

In 1934 the Lucases had their first child, Ann, and two years later Katherine, always called Kate. The pregnancies sapped Dorothy’s strength, triggering the ill-health that was to haunt the rest of her life, and looking after her two daughters placed a further strain on her frail constitution. Nevertheless, she encouraged her husband, accepting his decision to spend six days a week at the store, and helping with the book-keeping on Sundays. She even got pregnant again, though two miscarriages had convinced her doctors she should not have any more children. Confident of prosperity, Lucas bought a $500 lot on Ramona Avenue, a wide street on what was then the edge of town. With $5000 borrowed from Paul and Amos Bomberger, he built a single-story house at number 530. It was here that his only son, five-pound nine-ounce George Walton Jr, was brought home after his birth on 14 May 1944 – Mother’s Day.

3 An American Boy (#ulink_424cb4c8-a7cf-59e3-895d-4d05b29d5b8f)

I might be a toymaker if I weren’t a film-maker.

George Lucas to critic Joseph Gelmis, 1973

Ramona Avenue has changed little since 1944. Only two blocks long, and twice as wide as more modern streets, it illustrates the generosity of space with which town planners could indulge themselves in those days of unrestricted development. By comparison, its homes, all bungalows, appear cheap – though now, as in 1944, this corner of Modesto exudes prosperity. No sagging campers or rusting wrecks litter the front yards. Hedges are trimmed, flowerbeds weeded. There are few fences, and those that do exist are low enough to step over. In most cases, immaculate lawns run from the kerb right up to the front door, interrupted only by mimosas, four times taller than the houses, that turn the street into a permanent avenue of shade.

With a business and a family to run, George Sr didn’t go to war. Instead, ever the horizontal man, he deepened and widened his niche in Modesto. In shipbuilding, aircraft production, munitions manufacture, prefabricated housing, petrol and rubber production, food growing and canning, and, not least, film production, California led the rest of the Union. Both those wunderkinder of World War II’s construction industry, shipbuilding king Henry Kaiser and Howard Hughes, his aeronautical counterpart, operated from the state. ‘For tens of millions,’ writes social historian William Manchester, ‘the war boom was in fact a bonanza, a Depression dream come true.’

In 1945, when George Jr was eight months old, the Lucases’ fourth and last child, Wendy, was born. Two pregnancies so close together severely strained Dorothy’s health. She was never well again, and for the rest of George’s childhood the Lucas house, like Ramona Avenue itself, lived in shadow. Dorothy spent long periods in hospital, suffering from elusive internal disorders. Her doctors diagnosed pancreatitis, but later removed a large stomach tumor. Georgie and his sisters were brought up mostly by Mildred Shelley, known as ‘Till,’ a businesslike housekeeper who moved from Missouri to look after the family, and who became a fixture of the Lucas household.

George Lucas Sr did just as well in the post-war boom and the expansive business climate under Eisenhower as he had during the war. Like Ike, he became a devoted golfer; and he was a pillar of the local chamber of commerce and the Rotary, for both of which his father-in-law served as long-time president. The most doting of grandfathers, Paul Bomberger was around at Ramona Avenue most weekends with his 16mm camera, recording the progress of his three daughters and his diminutive grandson: watchful, silent, and tiny – only thirty-three pounds and three feet seven inches tall at six years of age – but with a reservoir of nervous energy which most of the family believed he inherited from his mother’s brother Robert, who was also short and feisty.

Georgie’s inquisitive look was accentuated by the Bombergers’ trademark protruding ears. His were so prominent that his father contemplated having the fault corrected surgically. Instead, the family doctor persuaded him to tape back the more protruding ear for a year. With childhood memories of lice infestation, George Sr insisted on having his son’s head shaved every summer. ‘It didn’t matter to us,’ says Lucas’s childhood friend John Plummer, ‘but George was humiliated.’ In his first feature, THX1138, Lucas would show a future repressive society in which everyone’s head is shaved.

When George was nine, the fiancé of his oldest sister Ann died in Korea, a loss which affected George deeply: lacking an older brother, he’d co-opted his future brother-in-law into that role. George also recalled a period of existential anguish when he was six. ‘It centered around God,’ he recalled. ‘What is God? But more than that, what is reality? What is this? It’s as if you reach a point and suddenly you say, “Wait a second, what is the world? What are we? What am I? How do I function in this, and what’s going on here?” It was very profound to me at the time.’ At least one other film-maker went through an almost identical crisis at the same age. Woody Allen’s parents recalled that, at age six, their son became ‘sour and depressed,’ setting the scene for his later films.

In 1949 Leroy Morris sold George Sr the rest of the business, retired, and died three days later. Immediately, Lucas moved the store to new premises on I Street, reopening as The Lucas Company. He began specializing in office machines, becoming the major supplier of calculators, copiers and office furniture to Modesto and nearby Stockton. Later he moved to Kansas Avenue as Lucas Business Systems, district agent for the 3M corporation and its products. In his first year of independence he grossed $30,000, a respectable sum for those days. He had built the sort of business any man would be proud to hand on to his son – if his son was interested.

George Jr was not interested, though for a while his father imagined he’d been born for a life of commerce. Georgie impressed everyone with his practical skills, his creativity, energy, seriousness, and persistence. His sisters remember him at two and a half studying workmen making repairs to the house, then finding a hammer and chisel and attacking a perfectly good wall. By the time he was ten, he showed a talent for construction: ‘I had a little shed out back with tools, and I’d build chess sets and dolls’ houses.’ A childhood friend, Janet Montgomery Deckard, says, ‘Georgie made an entire doll house out of a cardboard box for my Madame Alexander doll. The top was missing so you could look down into it. The walls were wallpapered and everything was in proportion to Madame Alexander.’ A quart milk carton became a sofa, which Lucas covered in blue-and-white chintz, and an old gold lipstick tube served as a lamp.

Lucas also built cars – ‘lots of race cars that we’d push around, like Soap Box Derby.’ With his friends John Plummer and George Frankenstein, he seized the opportunity of a new phone line being laid in the area to appropriate the giant wooden spool on which the cable was wound and, with a rickety runway and a home-made car, improvised a rollercoaster. Plummer, whose father knew people in construction, procured lumber and cement. Under George’s direction they created miniature fortifications and landscapes on which, using toy soldiers and vehicles from the Lucas Company, battles could be fought and refought.

A Lionel model-train set, the best in town, wound through the elaborately re-landscaped garden – a gift from the doting Dorothy. George always knew where to go for help with an ambitious scheme. ‘He never listened to me,’ said his father. ‘He was his mother’s pet. If he wanted a camera, or this or that, he got it.’

With his friend Melvin Cellini, who lived on the next street, George created one of his most complex ‘environments.’ Atmospheric lighting and careful arrangement of props converted the Cellini garage into a haunted house. Kids paid to see it, and there were queues for the first couple of days. George had the idea of encouraging repeat visits by changing the effects periodically. ‘George always was gifted with creative talent and business sense,’ says Cellini. Through Cellini, Lucas also made his first film. Melvin had a movie camera, and they did a stop-motion film of plates stacking themselves up, then unstacking themselves – Lucas’s first experiment in special effects. He never forgot the wonder of it: ‘We were so excited, like a pair of aborigines with some new machine.’

Modesto in general wasn’t a reading town, but comic books were ubiquitous, fanned by the momentum of the war years, when color printing and the demand for propaganda had turned them into an international enthusiasm. John Plummer’s father had a friend who ran a news-stand. Once a month he returned unsold comic books for a refund, but since wholesalers were satisfied with the torn-off covers, the Lucas gang got the books themselves. Georgie’s collection of five hundred comics became the envy of the town, and rather than have drifts of Captain Marvel and Plastic Man litter the house, his father resignedly added shelves to his backyard shed to accommodate it. His sister rescued the comics when George tired of them. Years later, she re-presented them to him. They became the nucleus of a large and valuable collection.

The first TV sets filtered into Modesto in 1949, and the Plummers immediately bought one. Georgie begged his father to do the same, but Lucas refused to allow such a distraction into his house. The Lucases didn’t get their own set until 1954. In their home, as in America in general, radio remained the primary entertainment. Eighty-two per cent of people still tuned in every night. ‘We didn’t get a television set until I was ten years old,’ Lucas recalled. ‘So for the first ten years, I was in front of the radio listening to radio dramas. It played an important part in my life. I listened to Inner Sanctum, The Whistler, The Lone Ranger – those were the ones that interested me.’

But TV couldn’t be stopped. So many people wanted to see the Plummers’ set that Mr Plummer put it in the garage and built bleachers to hold the crowd. George and his friends gathered there to stare at the tiny, bulging, almost circular screen of the old brown bakelite Champion. There was only one station, KRON-TV from San Francisco. It broadcast mostly boxing and wrestling matches, with the occasional cartoon, but the idea of an image piped into one’s own home awed them; they would have watched the test pattern. Lucas went round religiously to the Plummers’ every night at six for Adventure Theater – a twenty-minute episode of an old serial, with a Crusader Rabbit cartoon. Among the serials was Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe. Lucas never forgot it. Once the Lucases got a set, George sat in front of it for hours, especially during the Saturday-morning cartoon programs, with his black cat Dinky curled round his neck.

Lucas has often cited his early experience of television, but is more reticent about movie-going. ‘Movies had extremely little effect on me when I was growing up,’ he has said. ‘I hardly ever went, and when I did it was to meet girls. Television had a much larger effect.’

In 1955, George made the newspapers for the first time. The Modesto Bee reported that he and Melvin Cellini had launched a kids’ newspaper, the Daily Bugle. Cellini saw the idea on TV and co-opted his friend as star reporter, for reasons not unconnected with the family business: George Sr typed the paper’s wax stencils and ran them off on his office duplicator, though he insisted the kids paid for supplies from their profits.

In August 1955 they published their first daily one-sheet issue, printing two hundred copies. ‘You will get your paper free for two weeks,’ it announced, ‘but then it will cost 1 cent. Papers will be given out Monday to Friday. But this Friday it won’t be out because the press broke down.’ Even with George Lucas as reporter, however, the Daily Bugle didn’t flourish. Although the paper was padded out with jokes and riddles, they had trouble filling its pages with events around Modesto. George’s father had flown the family to Los Angeles to visit Disneyland, which opened in July 1955, and George described a different attraction in each issue, but by the second week even this resource was exhausted. ‘The Daily Bugle stops,’ announced their issue of 10 August. ‘The Weekly Bugle will be put out on Wednesday only. There is the same news.’

That the Bugle went out of business so soon is the oddest thing about it, since everyone who knew Lucas as a child agrees that his persistence and tenacity were prodigious. Once launched on a project, he would follow it through to the end. At eleven, given the job of mowing the lawn once a week to earn his pocket money, he saved his allowance until he had $35, borrowed a further $25 from his mother, and bought a power mower to lighten his task. His father, not recognizing the stringy resilience of his own father and grandfather in his son, was furious. Pushing the old mower round the yard every weekend was a valuable discipline. Getting through the job quickly with a power mower demeaned the lesson.

One could imagine Lucas devoting the same energy to the Bugle as to lawnmowing: hiring kids as reporters and vendors, making the paper a paying proposition, and ending up a professional publisher at fifteen. Though a team player, he would often in later life begin working with some charismatic and forceful individual, then gravitate to leadership, and finally supplant his mentor. Some people have suggested that this was his response to the lack of a sympathetic father, but Lucas’s explanation is more pragmatic: ‘That’s one of the ways of learning. You attach yourself to somebody older and wiser than you, learn everything they have to teach, and move on to your own accomplishments.’ He needed to be both part of a group and in charge of it; otherwise, he lost interest. In childhood, as in adulthood, Lucas belonged with the entrepreneurs who defined ‘teamwork’ as ‘a lot of people doing what I say.’

4 Cars (#ulink_dceb435f-20b2-5450-907d-85622b051dfa)

I love things that are fast. That’s what moved me toward editing rather than photography. Pictures that move – that’s what got me where I am.

George Lucas, Los Angeles Times magazine, 2 February 1997

George Lucas at fourteen, in 1958, was not much different to George Lucas forty years later. He had already, at five feet six inches, reached his full height. High-school class photographers habitually stuck him in the front row, where even classmates of average height loomed over him. The clothes his mother bought for him – jeans, sneakers, green polyester sweaters, open-necked blue-and-red-checked shirts with pearl buttons – would become a lifelong uniform.

By then, Lucas had discovered rock and roll. That was by no means typical. In the hit parade of 1958, ballads like ‘It’s All in the Game,’ ‘All I Have to do is Dream,’ and ‘It’s Only Make Believe’ far outnumbered Chuck Berry’s ‘Sweet Little Sixteen’ and Jerry Lee Lewis’s ‘Great Balls of Fire.’ But Lucas raced home to spend hours playing Presley, Buddy Holly, Chuck Berry, the Platters, the Five Satins. An autographed photo of Elvis adorned his wall. He adopted the personal style that went with rock. His hair grew longer, but no amount of Dixie Pomade could plaster its natural curl into the classic Elvis pompadour. His compromise – undulating waves at front and side, slicked down on top – only called to mind the Dick Tracy villain Flattop.

Lucas’s mood was unsure and often depressed: ‘I was very much aware that growing up wasn’t pleasant. It was just … frightening. I remember that I was unhappy a lot of the time. Not really unhappy – I enjoyed my childhood. But I guess all kids, from their point of view, feel depressed and intimidated. Although I had a great time, my strongest impression was that I was always on the lookout for the evil monster that lurked around the corner.’ In short, he shared the fears and anxieties of every imaginative child, but did not suffer the traumas associated with the break-up of his family or the loss of a loved one – emotional disturbances experienced by many of the people with who he would later work. Steven Spielberg’s parents were divorced; Paul Schrader’s Calvinist family forbade most secular diversions, including the cinema.

Thomas Downey High was the more modern of Modesto’s two high schools. With its echt-Californian frontage in modified fifties art deco, set well back from the road in wide playing fields, it was an agreeable place to spend one’s time; but Lucas took no pleasure in it. ‘I was never very good in school,’ he says, ‘so I was never very enthusiastic about it. One of the big problems I had, more than anything else, was that I always wanted to learn something other than what I was being taught. I was bored. I wanted to enjoy school in the worst way and I never could. I would have been much better off if I could have skipped [the standard curriculum]. I would have learned to read eventually – the same with writing. You pick that stuff up because you have to. I think it’s a waste of time to spend a lot of energy trying to beat education into somebody’s head. They’re never going to get it unless they want to get it.’

His sister Wendy would get up at 5 a.m. and go through Lucas’s English homework, correcting the spelling, but she couldn’t be there to help in the classroom. Another Modestan who graduated from Downey a few years after Lucas remembered the battery of tests inflicted by the teachers:

Some liked ‘big’ comprehensive tell-me-everything-you’ve-learned-this-semester tests, and others preferred exams that covered materials since the previous exam in the class. Some classes had quizzes on a weekly or intermittent basis. Others would have weekly or twice/thrice weekly assignments (essays, math homework, book reviews, stuff for art portfolios, language assignments) that would be more cumulative, requiring fewer exams for the teacher to evaluate your progress. I suspect, if George Lucas had a D average, he was constantly late on a lot of assignments and papers […] Either that, or he didn’t ‘buckle down’ and learn. Or he had/has an undiagnosed learning disability that made it difficult for him to complete the assignments, irregardless of his intelligence.

Lucas’s one aptitude was art. At home, he drew elaborate panoramas, and labored over hand-crafted greeting cards. ‘I had a strong interest even in high school in going to art school and becoming an illustrator,’ he says, ‘but my father was very much against it. Said I could do it if I wanted to, but he wasn’t going to pay for it. I could do it on my own.’ Teachers were no more encouraging. Schoolmate Wayne Anderson remembers the art teacher snapping, ‘Oh, George, get serious,’ when she found he’d ignored the subject assigned and had instead sketched a pair of armored space soldiers.

When he was fifteen, George’s life underwent a fundamental disturbance. Modesto was spreading as fruit-growers sold their orchards for building lots, and planted less fragile and labor-intensive crops. In 1959, George Sr bought thirteen acres under walnut trees at 821 Sylvan Road, on the outskirts of town, and moved his family into a ranch house on the property. George loathed his new home, which cut him off from all his friends. Until he could get his driver’s license and, more important, a car, he was a prisoner. When school ended each afternoon at 3 p.m., he rode his bike or took the school bus home, went straight to his room and spent the hours before dinner reading comics and playing rock’n’roll. Emerging, he’d eat in silence, watching the family’s Admiral TV, which, fashionably for the time, sat on a revolving ‘Lazy Susan’ mount that swivelled through 360 degrees. After that, it was back to his room again. Hoping to revive his son’s interest in construction, Lucas Sr designed a large box, with a glass top and front, in which he could continue to create his imaginary battlefields. He gave him a 35mm camera for his birthday, and turned the house’s second bathroom into a dark room. But while George fitfully pursued these enthusiasms, his heart was no longer in them. He was fifteen – in America, the age when a young man’s fancy lightly turns to thoughts of wheels.

When America went to war, the car industry was one of the first to be militarized. The Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor in December 1941. By February 1942, every automotive assembly line in America had been turned over to tanks. The government impounded any cars Detroit had in stock, and doled them out to the military and to people in protected occupations. By 1945, the supply of new cars was down to thirty thousand – three days’ worth by 1939 rates of sale. The shortage didn’t ease for five years, when the government permitted the importation of a few vehicles from Europe, almost entirely luxury cars like the Rolls-Royce, Jaguar, or Bentley, or, at the other end of the market, the Volkswagen and the Fiat Innocenti and the Autobianchi – the kind of ‘toy’ cars with which Detroit, still committed to the gas-guzzler, refused to soil its hands. (Curt Henderson in American Graffiti drives a clapped-out Citroën Deux Chevaux.) The occasional independent, like Preston Tucker, who tried to build and sell cars in competition with Detroit was ruthlessly put down.

‘If you didn’t have a car back then,’ says Modestan Marty Reiss, ‘basically you didn’t exist.’ Lucas agrees: ‘In the sixties, the social structure in high school was so strict it didn’t really lend itself to meeting new people. You had the football crowd and the government crowd and the society-country-club crowd, and the hoods that hung out over at the hamburger stand. You were in a crowd and that was it. You couldn’t go up and you couldn’t go down. But on the streets it was everyone for himself, and cars became a way of structuring the situation.’

If a kid couldn’t afford a VW or Fiat, he grabbed what he could, and adapted it. Four years of tinkering, repairing and making-do, added to the repair skills expected of kids who often needed to service farm machinery, had turned farm boys into fair auto mechanics. Prewar Detroit made its cars as simply as possible, to standardize spare parts. Two rusting wrecks might be cobbled together into one vehicle. During the war, undertakers could still buy hearses. Ranchers usually got a station wagon, farmers a pick-up. All were ingeniously adapted in the late forties and early fifties.

Surfers liked the long vehicles, ideal for carrying boards, but kids looking for something hot sought out the 1932 Ford Deuce Coupe and the ’47 Chevrolet, which they ‘chopped’ – lowering the roof as close to the hoodline as possible – and ‘channelled’ – dropping the body down between the wheels. Playing with the suspension could make the car look nose- or tail-heavy, or simply close to the ground in general: the ‘low rider’ look that signalled a driver looking for trouble. (In American Graffiti, John Milner reassures a cop that his front end is the regulation 12½ inches above the road.) Fitted with an engine souvenired from some much heavier car, with a ground-scraping new suspension, the low roofline giving the divided windscreen the look of threatening slit eyes, all the chrome stripped off, door handles removed, only the legal minimum of lights retained, and the whole thing repainted yellow, with flames down both sides, Grandpa’s 1932 Ford became that most ominous of post-war cultural artefacts, the hot-rod.

One end of the post-war car world was represented by customizers like George Barris, who turned Cadillacs into lavish display vehicles for Hollywood stars, with lashings of chrome, iridescent and multiple-layered lacquer finishes, and whorehouse interiors upholstered in animal skin, velvet or fur. At the other extreme was Junior Johnson, a North Carolina country boy who dominated the dirt-track circuits of the rural South, winning such a reputation that Detroit and the tire and gas companies began investing in the burgeoning worlds of stock cars and hot-rods.

Long, straight country roads offered the perfect laboratory for testing and perfecting often bizarrely adapted vehicles. The mythology of cars flourished particularly in predominantly white Northern California. Black musicians seldom sang about cars, but white ‘surfer’ groups like Jan and Dean and, particularly, the Beach Boys made them a staple. The latter’s ‘Little Deuce Coupe,’ ‘Shut Down’ and ‘409’ – named for the cubic-inch displacement of a Chevrolet engine – were major hits.

All over Stanislaus County, kids worked on their cars through the week and, on Saturdays, brought them to downtown Modesto, where they took advantage of the one-way system imposed by merchants to make a leisurely tour d’honneur along Tenth Street, across one block, down Eleventh and onto Tenth again.

Lucas said later, ‘When I was ten years old, I wanted to drive in Le Mans and Monte Carlo and Indianapolis,’ but his real interest in cars actually began when he was around fifteen, and became a ruling passion. On any Saturday from 1959 onwards, you could have found him on Tenth Street from around four in the afternoon to well after midnight.

Cruising in Modesto had a lot to do with sex, but, though Lucas claimed he lost his virginity in the back of a car with a girl from Modesto High, the tougher and more sexually active of the town’s two high schools, nobody has ever admitted to being his girl. John Plummer recognizes a lot of Lucas in the inept teenager played by Charles Martin Smith in American Graffiti: ‘There’s so much of George in Terry the Toad it’s unbelievable. The botching of events in terms of his life, his social ineptness in terms of dealing with women.’ His mother said, ‘George always wanted to have a blonde girl friend, but he never did quite find her.’ In Graffiti, Terry, who normally bumbles around on a Vespa scooter, inherits the car of his friend Steve Bolander when Steve goes off to college, and immediately snags Debbie (Candy Clark), the most bubble-headed blonde anyone could desire.

As cruising petered out in the early hours, more aggressive drivers peeled off and headed to the long, straight roads on the edge of town, where they could prove just whose car was the fastest. A mythology grew up around these dawn races, which Lucas celebrated in American Graffiti. In the film, they take place on Paradise Road – a real Modesto thoroughfare, but too twisty, locals agree, for racing. Dragsters preferred Mariposa Drive, Blue Gum Avenue, or, best of all, Rose Lane, where painted lines marked out a measured quarter-mile. The film showed drivers gambling their registration papers – ‘pink slips’ – though this was almost unknown: even a $20 side bet was daring. Most kids didn’t own the cars anyway: ‘You’re racing your daddy’s car tonight,’ was a favorite gibe – used by Harrison Ford as Bob Falfa in American Graffiti when he challenges John Milner. If parents bought a second car for their kids, they normally retained title. Most kids simply cruised in the family Chevy or Ford, the automatic transmissions of which they wrecked in a few months by intemperate ‘peeling out’ at high speed from the kerb, or by racing.

The bad boys of the car culture were the gangs. Modesto already had a hot-car club, the Century Toppers, which went back to 1947 and was led by Gene Wilder, later a prominent professional customizer. A car modelled on his chopped Mercury, the roof so low that the windscreen is barely a slit, features in American Graffiti, but Lucas preferred to confer immortality on a later and raunchier gang, the Faros, archetypal juvenile delinquents who hung out at a burger joint called the Round Table.

In American Graffiti, the Pharaos (sic) and their slow-talking, gum-chewing leader Joe, played by gangling Bo Hopkins, are every mother’s nightmare, in glitzy satin jackets and skin-tight jeans. They kidnap Curt (Richard Dreyfuss) and put him through an initiation rite that involves hooking a chain to a police car and ripping out its back axle.

Surviving Faros reject this characterization, and deny charges that they instigated fist-fights or poured gasoline onto roads and set it afire. ‘We never got in trouble,’ insists Ted Tedesco, one of three brothers, all foundation members of the Faros when the gang formed in 1959. To hear the Tedescos and other ex-members like Marty Reiss tell it, the Faros were just decent kids high on the car culture. ‘I don’t think more than five people smoked cigarettes,’ says Reiss. ‘Nobody was on drugs. Any obscenity, including “Hell” and “Damn,” was punished by a swat from the club paddle, as was spinning your tires within two blocks of the clubhouse.’ They’re silent, however, about Lucas’s accusation that though he was never a member, they used him as a stooge, sending him in to enrage other gangs who, when they chased the pint-sized troublemaker down an alley, found themselves facing the Faros armed with bike chains.

Lucas was right, they agree, about initiations, but they deny ever having done anything as drastic as trashing a police prowler. (Lucas insisted ‘some friends’ did try this trick one Halloween, but without the film’s spectacular result: ‘The car just sort of went clunk, and it was really very undramatic.’) The worst a potential member might endure was being rolled through a supermarket on a trolley, dressed only in a diaper, or being blindfolded and forced to eat dogfood, or a live goldfish – and even then, they insist, the fish was replaced by a piece of peach. ‘That was the big, tough club,’ says Reiss, now a respectable local businessman, like most other members. The Faros’ last president, Marty Jackman, even became the local representative of the Sierra Club.

As a teenager, Lucas wanted to join the Faros, or at least win their acceptance. He let his hair grow even longer, fitted silver toecaps to his pointed boots, and wore black Levi’s that remained unwashed for weeks at a time. Nagging his parents finally got him a car, a tiny Autobianchi, nicknamed, when Fiat bought up the company, the Bianchina. It had a two-cylinder engine, hardly more powerful than a motorbike, and with an appalling clatter. Even then, there was a trade-off: George would become the delivery boy of his father’s business.