Steven Spielberg

John Baxter

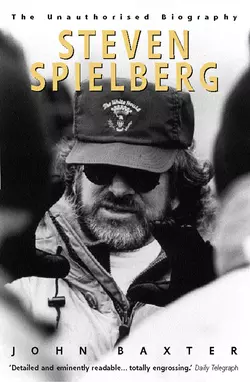

First published in 1996 and now available as an ebook. Please note that this edition does not include illustrations.Steven Spielberg dominated the cinema of the nineties. He is one of the screen's greatest enchanters, with a spellbinding capacity – and a box-office record – matched by very few.His power now exceeds that of the greatest moguls of Hollywood's golden era, and films like 'Jaws, ET, Close Encounters of the Third Kind' and 'Jurassic Park' have been seen by billions around the world, and have changed forever the way movies are made. How was it that this 'movie brat', from an unhappy and rootless adolescence on the fringes of American society, became one of the most formidable players on the global entertainment scene?.From 'Duel', which suggested the innate 'film sense' Spielberg would bring to movie-making, to the Oscar-winning 'Schindler's List 'and beyond…

The Unauthorised Biography

STEVEN SPIELBERG

JOHN BAXTER

Praise (#ulink_5901847c-74eb-5492-9b19-56ce764ee912)

Further reviews for Steven Spielberg:

‘Diligent, perceptive and with every available anecdote’

SIMON HATTENSTONE, Guardian

‘riveting… retains a healthy objectivity throughout his enthralling account’

PENELOPE DENING, Irish Times

‘… a film-lover’s book, a review of a remarkable era, an exhaustive filmography – a movie about the evolution of Hollywood, with Spielberg as the central character’

JEREMY LESTER, Jewish Chronicle

‘Baxter may have a blockbuster on his hands.’

RICHARD E. GRANT, Sunday Times

‘highly entertaining, packed with interesting information. If you want to know how a Spielberg film was made, what shenanigans went on during the making, or who fell out with whom, it is all here.’

WILLIAM RUSSELL, The Herald (Glasgow)

‘Its usefulness lies in Baxter’s shrewd assessment of Spielberg’s relationship with the wider context of the entertainment industry in general and Hollywood power-politics… the account of Spielberg’s unsettled early years… is illuminating in terms of his later preoccupations.’

HUGO DAVENPORT, Sunday Telegraph

‘Baxter is quietly professional… and makes good use of the copious interviews Spielberg has given throughout his career.’

ANTHONY QUINN, The Observer

‘A very valuable book… the thing that most impresses in his book is the calm, careful and nearly gentle way in which it builds up our disquiet that the movie kingdom and our society as a whole should be so ordered that Steven Spielberg is its Gatsby, its Kane, and such a shining young example… it is Baxter’s most intriguing point that Spielberg not only caters to youthfulness, but extends and preserves it… What is so clever, I think, is Baxter’s sense of a man too narrowly focused to amount to a villain… Baxter’s success is beyond question.’

DAVID THOMSON, Independent on Sunday

‘An impeccably professional film-biographer (he’s already done Buñuel, Fellini, Ford and is now working on Kubrick), Baxter leaves no document unrifled, no fact unchecked, no anecdote untold.’

Sight and Sound

‘… a full, frank and readable account of a man who the public regards as one of the greatest enchanters in the history of film.’

STUART GILLES, Manchester Evening News

Contents

Cover (#uf61d6071-ab09-5ce3-b6a8-4be613686884)

Title Page (#u483b24c5-7c3b-51f3-9ed1-eb25f7640427)

Praise (#ulink_97ee4113-5b0d-5799-bf30-5e0f805f3c95)

1 The Man who Fell to Earth (#ulink_caf441f1-391b-58fd-9b12-313bc28f3e53)

2 The Boy who Swallowed a Transistor (#ulink_db369efe-2578-5f4e-872c-41bf4eddc6d3)

3 Amblin’ Towards Bethlehem (#ulink_9d7fda32-2643-5ea7-964d-372fbd55dd29)

4 Universal Soldier (#ulink_3cd7eafb-f687-56f6-ae94-aad56cf1f51d)

5 Duel (#ulink_6de0c657-8735-574a-9ebe-f1bdc1e73393)

6 The Sugarland Express (#ulink_4229684e-cf2f-539e-9788-18f83ca9c69c)

7 Jaws (#litres_trial_promo)

8 Close Encounters of the Third Kind (#litres_trial_promo)

9 1941 (#litres_trial_promo)

10 Raiders of the Lost Ark (#litres_trial_promo)

11 Poltergeist and E.T: The Extraterrestrial (#litres_trial_promo)

12 The Twilight Zone: The Movie (#litres_trial_promo)

13 Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (#litres_trial_promo)

14 The Color Purple (#litres_trial_promo)

15 Empire of the Sun (#litres_trial_promo)

16 Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (#litres_trial_promo)

17 Always and Hook (#litres_trial_promo)

18 Jurassic Park and Schindler’s List (#litres_trial_promo)

19 The Dream Team

Notes

Select Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgements

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author

Also by the Author

Pre-Credit Sequence The Sandcastle

Filmography

Copyright

About the Publisher

1 The Man Who Fell to Earth (#ulink_9790af15-4679-5759-8a75-8bb2fe9247c9)

Yesterday, upon the stair,

I met a man who wasn’t there.

He wasn’t there again today.

I wish that man would go away.

Traditional rhyme

THE FORCE of American popular art lies in its directness, its simplicity, its economy of means and of scale. Analysis may uncover cultural and autobiographical references, sophistications of technique, even profundity of intellect, but the first appeal of a George Gershwin song, a Walt Disney cartoon, a Norman Rockwell painting is, and must be, commonplace delight.

Steven Spielberg embodies this tradition. His films, even the sombre Schindler’s List, are machines for delighting us. Almost always they succeed in doing so. It’s not hard to see why. He traffics in what authors of science fiction, his preferred form, call ‘a sense of wonder’, a heightened apprehension of physical possibilities. It has been said that the universe is not only stranger than we know but stranger than we can know. Spielberg dispels this idea. His vision, like that of the best science fiction writers, is of a welcoming, explicable place.

Writing about Ray Bradbury, whose books like The Martian Chronicles and Something Wicked this Way Comes share Spielberg’s simplicity of vision and sureness of technique, the critic Damon Knight, in a passage that could well refer to Spielberg, remarked:

To Bradbury, as to most people, radar and rocket ships and atomic power are big, frightening, meaningless names; a fact which, no doubt, has something to do with his popular success, but which does not touch the root of the matter. Bradbury’s strength lies in the fact that he writes about the things that are really important to us: not the things we pretend we are interested in – science, marriage, sports, politics, crime – but the fundamental pre-rational fears and longings and desires; the rage at being born; the will to be loved; the longing to communicate; the hatred of parents and siblings; the fear of things that are not self…

People who talk about Bradbury’s imagination miss the point. His imagination is mediocre; he borrows nearly all his backgrounds and props, and distorts them badly; wherever he is required to invent anything – a planet, a Martian, a machine – the image is flat and unconvincing. Bradbury’s Mars, where it is not as bare as a Chinese stage setting, is a mass of inconsistencies; his spaceships are a joke; his people have no faces. The vivid images in his work are not imagined; they are remembered.

In 1987, cartoonist Jules Feiffer drew a panel for the magazine Village Voice. A writing professor lauds a student for his ‘Joycean gift of language coupled with a Hemingwayesque spareness’. He goes on to compare him with Fitzgerald, Bellow, Updike, Styron, Mailer, then asks him what he’s working on. ‘A screenplay for Spielberg,’ the boy says airily. The professor is suddenly a beaming enthusiast. ‘Do you know him?’ he demands. ‘What’s he really like?’

The public urge to know what Spielberg is really like has never abated. His personality and appearance are so unremarkable, his public statements so bland, that everyone feels there must be a secret Spielberg hidden under the ramshackle exterior.

If you were to ask Spielberg what he is really like, he would probably reply that he is just like his audience. He is like everyone. But the image of Just Plain Steve is simply one aspect of his public persona. Examine that persona, and it fragments into a jigsaw puzzle where real memories slot into fabricated ones, and where childhood enthusiasms jostle for space with the structures of corporate power.

Spielberg’s indifferent communication skills don’t help to explain him to his public. His voice has never quite lost the self-absorbed gabble and stammer of the teenager drunk on ideas. ‘He has all the virtues – and defects – of a sixteen-year-old,’ one colleague remarks. Over the years he’s learned to smile and to pause occasionally for others to speak, but the interpersonal still daunts him. He communicates best from behind a protective grille of technology. On that level, he radiates competence. Everyone notices it. The novelist Martin Amis almost mistook him for the man who’d come to fix the Coke machine. Someone else described his image as ‘chemistry-student-next-door’. Both Amis and actor Tom Hanks compared him to the high school audio-visual assistant who alone understood 16mm projectors. (Spielberg worked his way through three years of college, in part by projecting classroom films.)

His mastery of cinema technology, what critic Pauline Kael called ‘a film sense’, is innate and effortless, his innocent flair and enjoyment disguising the complexities of what he does. ‘I got the feeling,’ said Julian Glover, who acted for him in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, ‘that, if he wanted to, he could have built the set. He knew as much about lighting as [director of photography] Douglas Slocombe. And he operated the camera himself.’ The worst sin for a Spielberg collaborator is to fail in technique. When that happens, Spielberg can be scathing. ‘There is no, “Nice try, guys – better luck next time,”’ complained one crew member. ‘He says things like, “You didn’t get it right. Think about that when you go to bed.”’

Partly by chance but increasingly by design, Spielberg has immured himself in the prison of his facility. It is the central irony of his life that the more he is driven to employ his skills, the more they destroy the very spontaneity he strives to capture. The audience which follows him, and which he helped create, is perfectly happy, however, with technique. To them, not understanding his systematic methods, his ability to engineer entertainment machines like Jurassic Park can seem almost miraculous, and it’s to a god that many of them compare him. Or an alien. When American Premiere magazine entitled one article about E.T. and its maker ‘Steven Spielberg in his Adventures on Earth’, they articulated a sense shared by many that he does not belong here. With his rodigies of imagination undermined by physical fragility and social clumsiness, he recalled the soft-spoken extra-terrestrial played by Michael Rennie in Robert Wise’s The Day the Earth Stood Still, or David Bowie’s Martian, fragile as a stick insect, in Nicolas Roeg’s 1976 film The Man Who Fell to Earth.

Spielberg makes a credible alien. He’s most comfortable with those who live in private worlds. When stories of eccentric habits and lifestyle accreted around Michael Jackson, Spielberg, who planned to film Peter Pan with the singer and spent hours playing games with him at his Disneyland-like estate, remarked wistfully, ‘It’s a nice place Michael comes from. I wish we could all spend some time in his world.’

Spielberg’s need for protection and distance has its roots in a genuine fragility. Since he was four years old, he’s bitten his fingernails. Despite his technical ease, he was for most of his early adulthood a white-knuckle flier who had nosebleeds at high altitudes. For many years he so disliked elevators that he’d walk up half a dozen flights of stairs rather than enter one. The man who terrified the world with Jaws also hated and feared the ocean, and the director of that archetypal night-time film Close Encounters of the Third Kind admits, ‘I’m scared of the dark except in a motion picture theatre.’

It is only in the welcoming darkness of the cinema that Spielberg truly feels at home – and only with the myths of the movies that he is intellectually comfortable. Increasingly, it has been through and by myths that he has chosen to define himself. Admirers have been quick to add their own manufactured myths that confirm his role as an Honorary Outsider, and just another misunderstood teenager, like them; a Peter Pan of movies, the Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up, but who invested hugely in preserving himself in artificial adolescence. As early as Jaws in 1974, rumour claimed – erroneously – that Spielberg’s jeans with their multitude of zipped pockets were specially made for him at $250 a pair. Even his pet Cavalier King Charles spaniels were pressed into the fantasy. Some people felt the turnover in dogs was curiously high. As Zalman succeeded Elmer, Chauncey succeeded Zalman and Halloween followed Chauncey, rumours grew that Elmer/Zalman/Chauncey/Halloween wasn’t a dog but a role: when the incumbent lost its puppy cuteness, another replaced it. Friends insist this is untrue. However, Spielberg’s reclusiveness fanned the story, and others like it.

Although Spielberg’s career is entwined with that of George Lucas, the two men are cultural and psychological opposites. Lucas, short, slight, seems habitually curled in on himself, arms often folded across his body. Spielberg, at five feet eight inches and 151 pounds, is fractionally taller, but contrasting body language exaggerates the difference. ‘Some people look at the ground when they walk,’ he says. ‘Others look straight ahead. I always look upward, at the sky.’

Lucas’s expressionless face and low, toneless voice emphasise the mask effect of his beard and moustache. Director John Badham calls him ‘a painfully shy person who hates dealing with people’. Writer Willard Huyck, another student friend, said, ‘George made a few friends at [the University of Southern California Film School], and decided that’s about all he needed for the rest of his life.’

As a director, he communicates even less. ‘George Lucas,’ confided a Star Wars actor, ‘is the worst director in the world. Never takes his nose out of the newspaper.’ The conventional view of film as a collaborative art – or an art of any kind, for that matter – isn’t his.

Lucas’s childhood in Modesto, California, was suffused with Methodism and German Lutheranism. He reacted against it in adulthood by creating a laid-back, feel-good home life. This ‘redwood tub mentality’ amused Spielberg, who joked about ‘LucasLand’. Spielberg himself is a product of the east coast suburbs, the rural midwest and the high desert of Arizona, but culturally he is archetypally Jewish; Thomas Keneally, author of Schindler’s List, talks of his ‘classic Central European map-of-Poland face’. His first memory is of being taken to a synagogue at six months, and he learned numbers from those tattooed on the arm of a relative who survived Auschwitz. Though he’d been bar mitzvahed, he didn’t practise his religion until well into adulthood. Long before that, however, he went out of his way to introduce a Jewish dimension into his films. In both Jaws and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, characters written as gentile were redesigned to accommodate Richard Dreyfuss, an actor proudly and obviously Jewish. It wasn’t until Spielberg’s second marriage, to the actress Kate Capshaw, that he integrated his cultural heritage into any system of belief, but since childhood, Judaism exercised a powerful influence of which even he wasn’t fully aware.

Being born Jewish also gave Spielberg an entrée to Hollywood which gentiles – and this included most of the USC group – could never possess. Along with Lucas, the film-makers who came to be known as New Hollywood included Brian De Palma (Carrie, Sisters), John Milius (Big Wednesday), the slightly older Francis Coppola (the Godfather trilogy, Apocalypse Now), husband and wife producers Michael and Julia Phillips (The Sting) and a group of lesser talents like writers Hal Barwood, Matthew Robbins, Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz, composer Basil Poledouris and cameraman/director Carroll Ballard.

Most emerged from that sixties phenomenon, the university film school, and elected to work inside the studio system rather than in the underground. Christened ‘Movie Brats’ by Michael Pye and Lynda Myles in their 1979 book The Movie Brats: How the Film Generation Took Over Hollywood, they rushed into the vacuum created when the US Justice Department forced the studios to shed their theatre chains and embrace the free market.

Old Hollywood had served the post-war baby boomers, now entering their thirties and looking for a Nice Night’s Entertainment. New Hollywood targeted their children, the teens and pre-teens in Nike and Adidas trainers, stone-washed Levis and New York Yankees caps, who spent homework time reading EC Comics’ Tales from the Crypt or watching reruns of the TV series Twilight Zone, and queued every weekend outside multiplex cinemas across the country.

Spielberg’s technique to win this audience was to scavenge Hollywood’s scrapyard, salvaging genres and recycling them in widescreen, colour and stereo sound. His ability to resuscitate moribund material was unique. His approach to the shark of Jaws, to Puck, the ‘Little Green Man’ of E.T., Jurassic Park’s velociraptor dinosaurs and the Nazis of Schindler’s List was identical. In each case, he animated a cliché by showing that even cardboard thinks and feels. Not for nothing was he an admirer of Disney’s Pinocchio, in which a puppet is brought to life.

As an added guarantee that the audience would embrace his work, Spielberg preferred never to instigate an idea. The tendency of Lucas and Scorsese to push ahead with their visions, bulldozing all in their path, could produce successes, but Spielberg fed on consensus, not confrontation. Most of his films would be years in gestation, and would often begin with another director. Jaws had been Dick Richards’s film. Close Encounters of the Third Kind originated with Paul Schrader. Phil Kaufman would start as the director of Raiders, John Milius developed 1941, Tobe Hooper Poltergeist, and Hooper, with John Sayles, did the preliminary work on E.T. Empire of the Sun was intended for David Lean. Even Schindler’s List was at one point a Martin Scorsese project.

Just as Spielberg is anything but the common man, he’s also anything but the common artist. His vision is closer to that of a politician or a corporate CEO than to a film-maker. Newsday critic Jack Matthews articulated the truth that had been dawning for some time on the filmmakers with whom Spielberg had grown up in the industry, but whom he is now leaving further and further behind: ‘His contemporaries in the Hollywood firmament are not Scorsese and Coppola, they’re studio execs Jeffrey Katzenberg, Mark Canton, Peter Guber, Joe Roth and the other fortysomething crowd controlling the power.’ The critic Peter Biskind has pointed out how closely Spielberg’s and Lucas’s business philosophies conformed to those of Ronald Reagan, who served as president from 1981 to 1989, throughout the period of their greatest success. Reagan, says Biskind, ‘was the strong father Lucas and Spielberg didn’t know they were looking for, the ideal president for the age of Star Wars’. In temperament, Spielberg has more in common with the Democrats like John F. Kennedy who saw it as their role to make a world fit for baby boomers to live in. Arthur Schlesinger Jr speaks of Kennedy as ‘a realist and an ironist, a man of sardonic wit and impenetrable reserve who sought to apply reason to the problems of state’. One senses some of the same cool estimate of cause and effect in Spielberg. ‘His direct and unfettered mind,’ Schlesinger continued of Kennedy, ‘freed him to contemplate a diversity of possible courses. At the same time, he was a careful judge of those possibilities and was disinclined to make heavy investments in losing causes… He once described himself to Jacqueline as “an idealist without illusions”.’ Spielberg shares many of these characteristics, albeit in diluted form. He’s even closer, however, to the philanthropic industrialists of a century ago like Carnegie and Frick.

In person, he appears diffident, nervous, unsure, eager to be liked and to have his work approved by the audience, but a frosty stare at moments of threat reveals him as a man who understands power and expects to be obeyed. On the set, he’s fast, focused, saying little to his crew, even less to his cast. He’s animated, however, when talking business. If he is truly an artist, his art is the deal. No Edison or Ford, perhaps – but Federico Fellini was right to say, as he did to Francis Coppola, ‘Spielberg is a tycoon, like Rockefeller.’ When historians assess the 1970s and eighties, during which entertainment and audio-visual media began to dominate large segments of the world economy, Spielberg, along with innovators like Microsoft’s Bill Gates, may well emerge as a major architect of the change.

Millions would be astonished to hear Spielberg called, as he sometimes is, ‘the most hated man in Hollywood’. Admittedly, ‘hate’ is a term so contaminated by self-interest as to be meaningless in show business. The gibe ‘You’ll never work in this town again – unless we need you’ embodies so much conventional wisdom that nobody sees it as a joke. After Spielberg allied with ex-Disney studio head Jeffrey Katzenberg and record producer David Geffen in 1994 as DreamWorks SKG, David Letterman, master of ceremonies of the 1995 Oscar broadcast, joked that the alliance was a time saver; instead of waiting for them to fail separately, Hollywood could now wait for them to fail as a group.

However, even if one replaces ‘hated’ with ‘resented’ or ‘envied’, a residue of genuine dislike remains. Friends and colleagues agree; Steven Spielberg is hard to like. Geffen called him, according to Julia Phillips, ‘selfish, self-centred, egomaniacal, and worst of all – greedy’. Geffen denied the quote, but there are plenty in Hollywood prepared to endorse it, if not for the record. Spielberg can be remote, grasping, sulky, narrow. In his office, he seldom acknowledges anyone except to raise some technical point. He ‘lacked social graces’, one colleague said of his rapport, or lack of it, with his employees. ‘He never asked anybody about their personal lives. His only subject of conversation is the movies.’

But Spielberg shares these characteristics with many – perhaps most – great directors. Fellini, Buñuel and Welles all drew the same criticism. Likewise many of his own contemporaries in New Hollywood. Filmmaking is an art learned in decades alone in the dark with other people’s dreams, and pursued in an environment of inflated egos and expectations, sudden-death deadlines and Brobdingnagian profits and losses. As the matador respects the bull more than the crowd which gathers to see one of them die, directors come to love films more than they love the audience.

During the seventies and eighties, while he was finding his feet, Spielberg was famously approachable. While other directors retired to their trailers between takes and had lunch sent in, he schmoozed with the actors, ate in the commissary and hosted evening screenings of his favourite old movies to which the entire cast and crew were invited. He always entertained his cast at dinner just before shooting, and greeted each of them, ‘Welcome to the family.’ Lucas simply sent a basket of fruit to their rooms.

All this, however, may simply have been more a technique of manipulation than a sign of interest in other people. ‘Directing is 80 per cent communication and 20 per cent know-how,’ Spielberg says. ‘Because if you can communicate to the people who know how to edit, know how to light, and know how to act – if you can communicate what you want… and what you feel, that’s my definition of a good director.’ One of the warmer stories about him describes him winning over ageing star Joan Crawford on his first job by presenting her each day with a rose in a Pepsi-Cola bottle: Crawford was the widow of Pepsi’s chairman. At an American Film Institute seminar, however, Spielberg recollected cynically: ‘I put the day of the week on the Pepsi bottle, and each day I’d give her one. She didn’t know it was a countdown. I couldn’t wait to get off the picture. Oh yeah, I did a lot of that bullshit.’

What sort of man prefers to be seen as a cunning manipulator than a charming collaborator? The same kind who will get up early on a film set to bake matzoh for 150 people? With Spielberg, it is safer to suspect the easy answers. He is stranger than we know – perhaps stranger than we can know.

2 The Boy Who Swallowed a Transistor (#ulink_47cdc90d-53a0-5664-8e8c-54ea3e0031c8)

We belong to the last generation that could relate to adults.

Joan Didion

HE WAS short and thin. His ears stuck out, and his narrow face seemed to elongate towards the chin, making his mouth V-shaped, and pulling the lower lip out and down, so that his mouth would never seem quite closed. He looked like an inquisitive bird, with a beaky nose he found so embarrassing in childhood that he stuck tape to the tip of it and to his forehead, praying it would develop a tilt. The beak was matched by a bird’s gaze, motionless, eerily unblinking. If he disliked something, as adult or child, he just stared it out of existence. A bird’s voice, too, high, fast, uninflected. And he moved in an avian way, darting and stopping, darting and stopping, his actions apparently unmediated by intellect. When teams were chosen for any game, he would always be the last one picked. Nobody wanted jerky little Steven. Adolescence would bring not muscles but acne, freckles and even greater gawkiness. His thin arms so embarrassed him that it wasn’t until the production of Close Encounters of the Third Kind in 1976 that he dared take off his shirt in public.

Spielberg’s birth almost coincided with the first sightings of UFOs over the United States. On 24 June 1947, Idaho businessman Kenneth Arnold, flying his two-seater plane over the Yakima Indian Reservation in Washington state, reported nine shallow dish-like objects heading towards the Cascade Range. They looked to him like skipping stones, but he estimated their speed at 1200 m.p.h. Over the next two weeks ‘flying saucers’ were seen in thirty states, after which sightings settled down to fifty a month.

For many years it was believed that Spielberg was born a few months after this, at the Jewish Hospital in Cincinnati, Ohio. In fact, his mother Leah Posner Spielberg gave birth to him a year earlier, on 18 December 1946, a date Spielberg systematically obscured during his early adulthood. He was followed within the next few years by three sisters, Anne, Sue and Nancy. Spielberg would complain that he spent his childhood in a house with three screaming younger sisters and a mother who played concert piano with seven other women. Elliott’s little sister Gertie in E.T., inclined to sudden squeals and conversational irrelevancies, was, Spielberg claimed, an amalgamation of his three ‘terrifying’ siblings.

Leah Posner was small, agile and nervous, like her son. She hated to fly, a trait he inherited. She’d trained as a pianist, but given it up as a possible career when she married Arnold Spielberg, another locally-born Cincinnatian whose parents, like hers, had come from Poland and Austria in the century’s first wave of immigrants. Almost immediately after their marriage, Arnold enlisted in the Air Force, flying as a B-25 radio operator in Burma with a squadron nicknamed the ‘Burma Bridgebusters’. Demobilised, he stayed with electronics, which had fascinated him since he was eight or nine. In 1948, Bell Telephone engineers John Bardeen, Walter Brattain and William Shockley invented the transistor, the tiny germanium diode that would replace vacuum tubes and make miniaturised electronics possible. Arnold found a job with the Burroughs business machine company, working on the beginnings of computers. An obsessive tinkerer, he would bring home bits of equipment, or drag the family off in the middle of the night to observe some natural wonder. His son thought him inflexible and workaholic. Richard Dreyfuss’s character Roy Neary in Close Encounters is a not entirely affectionate portrait of him.

Arnold read the science fiction magazines that proliferated after the war as publishing stumbled on a middle-class audience newly sophisticated in technology and interested in its potential. John W. Campbell built the monthly Astounding Science Fiction into the premiere sf magazine, discreetly alternating fiction with technical articles and the occasional outright piece of charlatanism, like Dianetics: A New Science of the Mind, in which L. Ron Hubbard, one of Campbell’s most successful pre-war fiction writers, expounded his pseudoscientific religion, Scientology. Sensing a shift in his readership towards technology, Campbell changed the title in 1960 to Analog Science Fiction/Science Fact and began publishing more thoughtful material, typified by Frank Herbert’s ecological saga Dune. Arnold Spielberg, an Analog fan, piled copies behind the lavatory cistern in the bathroom where he could read them in comfort and privacy.

Broadcast media permeated Spielberg’s childhood. When he was four or five, his father built him a crystal set. He would lie in his room at night, listening through an earpiece – and sometimes, he insists, through his teeth. ‘I remember one day, without the radio, hearing some music and then hearing this voice I was familiar with from the radio. It was the comedy programme Beulah.’

‘There are certain young directors, like Steven Spielberg,’ says film editor Ralph Rosenblum, ‘who were raised in the age of television and seem to have an intuitive sense of film rhythm and film possibilities.’ Spielberg agreed. ‘I did begin by reading comics. I did see too many movies. I did, still do, watch too much television. I feel the lack of having been raised on good literature and the written word.’ As critic David Denby would say later of him and his generation of directors, ‘Cartoons exert a greater influence than literature on his tastes and assumptions.’ For the rest of his life, Spielberg would apologise for lacking the intellectual discipline to deal with print. ‘I don’t like reading. I’m a very slow reader. I have not read for pleasure in many, many years. And that’s sort of a shame. I think I am really part of the Eisenhower generation of television.’

TV had just begun to pervade America. 1952 saw the debut of the prototypical cop series, Dragnet, the celebrity tribute programme This is Your Life, The Jackie Gleason Show, with Gleason as a New York bus driver with delusions of grandeur and Art Carney as his dutiful sewer-worker friend, and Our Miss Brooks, one of many series to give a new career to a Hollywood character performer, in this case Eve Arden as an acerbic unmarried middle-aged schoolteacher.

It was The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet, however, which exerted the greatest influence over Spielberg’s generation. Band leader Ozzie Nelson transferred his situation comedy from radio, and with it his real-life family, including son Eric, known as Ricky, whom the series made into a pop star. TV cloned the Nelsons into a multitude, among them the Cleavers of Leave it to Beaver and the white-bread Andersons of Father Knows Best, led by another Hollywood retread, Robert Young, whom Spielberg would find himself directing. As David Halberstam says, the sitcoms celebrated

a wonderfully antiseptic world, of idealised homes in an idealised, unflawed America. There were no economic crises, no class divisions or resentments, no ethnic tensions… Dads were good dads whose worst sin was that they did not know their way around the house or could not find common household objects or that they were prone to give lectures about how much tougher things had been when they were boys… Moms and dads never raised their voices at each other in anger… This was a peaceable kingdom. There were no drugs. Keeping a family car out late at night seemed to be the height of insubordination… Moms and dads never stopped loving one another. Sibling love was always greater than sibling rivalry. No child was favoured, no child was stunted.

The reality was very different. In 1955 teenage pregnancies reached a level unsurpassed even in the nineties, and one in every three marriages ended in divorce.

It was into this real world that Spielberg descended from TV’s fantasies of domestic perfection. Leah and Arnold Spielberg were no Ozzie and Harriet. Leah was frustrated in her musical ambitions, Arnold harassed by the need to keep up in a competitive new industry. ‘He left home at 7 a.m.,’ Spielberg recalled, ‘and sometimes didn’t get home until 9 or 10 p.m. I missed him to the point of resenting him.’ Their children roved the emotional no man’s land between them. ‘[My mother] would have chamber concerts in the living room with her friends who played the viola and the violin and the harp. While that was happening in another room, my father would be conferring with nine or ten men about computers, graphs and charts and oscilloscopes and transistors.’ Sometimes the conflict degenerated into domestic arguments. When these started, the four children huddled together, listening to the marriage fall apart.

Steven learned to tune out the rage and fear. He’d go into his room, close the door and, stuffing towels under it, immerse himself in building model planes from Airfix hobby kits. ‘For many years I had a real Lost Boy attitude about parents,’ he said. ‘Who needs them?’ He carried his defence mechanism into adult life. When an employee of Spielberg’s told Leah she’d quit Amblin Entertainment, Leah laughed and asked, ‘Have you ceased to exist yet?’

‘She knew the deal,’ said the employee. ‘That’s his childlike personality. If you do something a baby doesn’t like, he just shuts you out.’

Television became at once Steven’s educational medium and security blanket. Leah and Arnold didn’t allow him to watch anything as violent as Dragnet, but he absorbed almost everything else, in particular the old movies which were TV’s cheapest and most reliable fodder. For him, as for many of his contemporaries who became directors in the seventies and eighties, TV was his film school.

It gave him a taste for Hollywood films of the thirties, in particular the A-pictures of MGM, which often featured an actor who, to him, was the epitome of fathers, Spencer Tracy. Tracy’s appearance in MGM’s 1937 adaptation of Kipling’s Captains Courageous, about a spoiled rich kid who, falling overboard from an ocean liner, is rescued by a Portuguese fisherman and educated and civilised by him, profoundly affected Spielberg. It, and Tracy, would provide the key to his version of Empire of the Sun, just as another Tracy film, Adam’s Rib, in which Tracy and Katharine Hepburn play married lawyers who represent opposite sides in a domestic violence case, would inspire scenes in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade and in Raiders of the Lost Ark, where Harrison Ford coaxing kisses from Karen Allen parallels Tracy doing the same with Hepburn.

Spielberg was drawn even more to the fantasies of the period. His parents barred him from horror films – which, in any event, were not extensively programmed at the time – but he saw most of Hollywood’s imaginative classics, including Lost Horizon. The virtuoso first third of Frank Capra’s 1937 film of James Hilton’s novel, with the small group of refugees carried across the roof of the world in a montage of maps, mountainscapes, bantering dialogue, high-plateau refuelling stops and a final spectacular special effects crash, would be replicated in the Indiana Jones movies.

Mobs interested Capra. Nobody was more skilful at orchestrating crowds in motion, cutting between a few significant cameos as detonators to drive a screen filled with people into surging movement, and Spielberg learned his lesson well. He was influenced in particular by It’s a Wonderful Life. Offered by Capra and James Stewart as an affirmation to post-war America of everything it had fought to preserve, the fantasy of a savings and loan manager in rural Bedford Falls who sacrifices everything for his neighbours, only to lose faith, then regain it when an angel reveals the hell his town would have been without his contribution, the film endorsed everything Spielberg most needed to believe in: family, community, suburbia.

Steven’s first memory was a visual one, of being taken to a Hassidic Jewish temple in Cincinnati by his father. Still in his stroller, he stared in wonder as he was rolled down a dark corridor into a room filled with men wearing long beards and black hats. He only had eyes, however, for the blaze of red light flowing from the sanctuary where, in imitation of the biblical Ark of the Covenant, the rolls of the holy torah were kept. The impression was indelible. ‘I’ve always loved what I call “God Lights”,’ he says, ‘shafts coming out of the sky, or out of a spaceship, or coming through a doorway.’ Asked to define the central image of his work, he nominated the scene from Close Encounters where six-year-old Cary Guffey, about to be kidnapped by aliens, stands in the open kitchen door; ‘the little boy… standing in that beautiful yet awful light, just like fire coming through the doorway. And he’s very small, and it’s a very large door, and there’s a lot of promise or danger outside that door.’

The blank TV screen exercised a similar fascination. When Spielberg’s parents went out, they draped the set with a blanket and booby-trapped it with strategically placed hairs to reveal if Steven was viewing surreptitiously. He learned to note the position of the hairs and replace them. Then he would turn on the set and watch it, even if nothing was being transmitted. He was fascinated by the hissing ‘snow’, and the ghosts of faraway stations. Pressing his face to the tube, he would pursue them as they drifted in and out of range.

Sensory overload became Spielberg’s preferred state of mind, and remained so for decades. He functioned best, he told a journalist, in a soup of received impressions: radio and television blaring, record player going, dogs barking, doorbell ringing – all while he answered a telephone call. Directing Hook in 1990, he would sit on the camera crane between shots, playing with a Game Boy and at the same time eavesdropping with earphones on flight controllers at LA International Airport.

As a child, alone in his room, he induced an aesthetic frenzy by a sort of optical masturbation, throwing hand shadows on the ceiling and scaring himself with them. Seeing himself as both artist and medium encouraged a schizophrenic division of personality. Until he was fourteen, he would stare into the mirror for five minutes at a time, hypnotising himself with his own reflection. As an adult, he would reach for a camera at moments of stress and photograph his tearful face in a mirror, the film-maker dispassionately recording the stranger inside him.

Insecurity bred fantasies of domestic disaster. He imagined creatures living under his bed, monsters lurking in the closet, waiting to suck him in. At night, he would lie shivering under the blankets, fancying that the furniture had feet, and that tables and chairs were scuttling about in the dark. ‘There was a crack in the wall by my bed that I stared at all the time,’ he said, ‘imagining little friendly people living in the crack and coming out to talk to me. One day while I was staring at the crack it suddenly widened. It opened about five inches and little pieces fell out of it. I screamed a silent scream. I couldn’t get anything out. I was frozen… I was afraid of trees, clouds, the wind, the dark… I liked being scared. It was very stimulating.’

In 1952 Arnold introduced Steven to two phenomena that fundamentally affected his life.

My dad woke me in the middle of the night and rushed me into our car in my night clothes. I didn’t know what was happening. It was frightening. My mom wasn’t with me. So I thought, ‘What’s happening here?’ He had a thermos of coffee and had brought blankets and we drove for about half an hour. We finally pulled over to the side of the road, and there were a couple of hundred people, lying on their backs in the middle of the night, looking up at the sky. My dad found a place, and we both lay down. He pointed to the sky, and there was a magnificent meteor shower. All these incredible points of light were criss-crossing the sky. It was a phenomenal display, apparently announced in advance by the weather bureau… Years later we got a telescope and I was into stargazing.

To memorialise this incident, Spielberg has incorporated a shooting star in all his films.

The other event of 1952 was his first experience of a movie theatre. Again it was Arnold who took him, after carefully explaining what they were going to see. Not carefully enough, however, since Steven thought Cecil B. DeMille’s film about a circus, The Greatest Show on Earth, was a real circus and not one on film. The circus interested him, since his mother had told him how an uncle had run away with one as a boy; the same uncle, it seems, who had been in the black market, and had hidden contraband watches under the family bed.

DeMille’s film conflated all the fantasies of circus life: the clown, played by James Stewart, whose permanent make-up hides his tragic past as a surgeon; sadistic animal trainer Lyle Bettger; French trapeze artist Cornel Wilde (‘Ze Great Sebastian’); tough boss Charlton Heston, and all-American love interest in the person of raucous blonde Betty Hutton, all culminating in the collision of two trains where Stewart’s long-suppressed skills are called upon.

Arnold told Steven, ‘It’s going to be bigger than you are, but that’s all right. The people in it are going to be up on the screen and they can’t get out at you.’ (This is a common fantasy of suggestible children. Stephen King shared it, and as an adult persuaded his children not to sit too close to the screen by telling them that people who did so fell into the picture and became the extras visible behind the stars.) Spielberg recalls:

So we stood in line for an hour and a half, and we go into this big cavernous hall and there’s nothing but chairs and they’re all facing up, they’re not bleachers, they’re chairs. I was thinking: something is up, something is fishy. So the curtain is open and I expect to see elephants and there’s nothing but a flat piece of white cardboard, a canvas… I retained three things from the experience: the train wreck, the lions and Jimmy Stewart as the clown.

As soon as he had a train set, Spielberg repeatedly recreated the crash, and shadows of DeMille’s cardboard characters drift through many of his films. Indiana Jones has something of Heston, while Betty Hutton is the model for Willie, the shrill nightclub singer heroine of Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. Above all, DeMille’s showmanship left an indelible impression. ‘I guess ever since then I’ve wanted to try to involve the audience as much as I can,’ said Spielberg, ‘so they no longer think they’re sitting in an audience.’

He continued to find movies, unlike television, emotionally overwhelming. Especially Disney cartoons. At eight, he said, he ‘came screaming home from Snow White…’ – in some interviews he’s eleven, and the film is Bambi – ‘and tried to hide under the covers. My parents didn’t understand it, because Walt Disney movies are not supposed to scare but to delight and enthral. Between Snow White, Fantasia and Bambi, I was a basket case of neurosis.’ Though he was allowed to watch the Wonderful World of Disney TV shows, with their compilations of cartoons and behind-the-scenes documentaries about Disney films in production, his parents tried to keep him away from the feature cartoons. It gave them a glamorous sense of the forbidden they never lost.

One price of Arnold’s job in a sunrise industry like electronics was the occasional moves in search of work or promotion. In 1950 the Spielbergs had relocated in Haddonfield, New Jersey, when he joined RCA. In 1953 he took a job with General Electric in Scottsdale, Arizona, then a dormitory town east of Phoenix, but now a suburb. They were to spend eleven years there. The move wrenched Steven, and instilled his lifelong sense of dislocation and loneliness. ‘Just as I’d become accustomed to a school and a teacher and a best friend,’ he complained, ‘the FOR SALE sign would dig into the front lawn and we’d be packing. And it would always be that inevitable goodbye scene, in the train station or at the carport, packing up the car to drive somewhere, or at the airport. Where all my friends would be there and we’d say goodbye to each other and I would leave. And the older I got the harder it got.’ Among the first phrases he learned to say was ‘looking forward to’. His grandparents would occasionally come from New Jersey to Ohio to visit, and he loved it when his mother said it was something to look forward to.

His mother had been no less anguished. ‘I was hysterical,’ she recalled. ‘I mean, in 1955 what nice Jewish girl moved to Arizona? I looked in an encyclopedia – it was published in 1920, but I didn’t notice at the time – and it said: “Arizona is a barren wasteland.” I went there kicking and screaming. I had to promise Steve a horse, because he didn’t want to go either. I never made good on that promise, and he still reminds me of it today.’ Phoenix, as Jodie Foster was famously to remark in Martin Scorsese’s Alice Doesn’t Live Here Any More, is ‘weird’. Scottsdale, described by one visitor as ‘suburbia on steroids’, itself mixed mass-produced bungalows of the kind in which the Spielbergs lived with sprawling ranch-type houses set in gardens of sand, rock, spiky yucca and twenty-foot-high saguro cactuses. The desert around Scottsdale attracted more than its fair share of visionaries who exploited its open spaces and frontier manners to experiment. Frank Lloyd Wright started building his winter home Taliesin West just north-east of the town in 1937. Despite the discomfort of the fieldstone building, it became a centre for his students from Wisconsin, and after his death in 1959 metamorphosed into an arts centre and museum. One of Wright’s students, Paolo Soleri, chose another spot outside Scottsdale to build Arcosanti, his ‘arcology’, a community of futuristic shell-like buildings integrated into the desert environment.

Spielberg seems never to have visited either Taliesin West or Arcosanti. The visions offered him nothing. He enrolled in Scottsdale’s Arcadia High School but, whatever school meant to him, it wasn’t higher education. He’s always avoided discussing classes or his academic record, which, in common with most of the Movie Brats, was dismal. A survey of America’s twelve most influential media personalities in the nineties found that more than half never finished college. Three of them, including Ted Turner, were dyslexic. Spielberg has always had to struggle with the written word. There are no extant Spielberg letters, no diaries, and he never brings a script on set, preferring to memorise the shots beforehand. ‘He wasn’t a good student,’ Leah says. ‘He was less than mediocre. He needed tutors in French and math.’ Asked to dissect a frog in biology class, he threw up, an incident recycled in E.T. His sole reference to English class is a memory of turning a copy of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter into a flip book by drawing cartoon characters on the corner of each page.

More important than anything that happened in class were the friendships and alliances of the playground. Like any sensitive child Spielberg loathed new places and people but, once accepted, he embraced them with jealous fervour. The metaphor of the new school remained with him for life. When he encountered George Lucas’s tight team, he found it like changing schools. He felt, he said, as if he’d moved into Lucas’s eighth-grade class.

At Arcadia High School he signed up with the Boy Scouts, and was admitted to its honour society, the Order of the Arrow. He began to study the clarinet too, and to march in the school band. Leah’s preoccupation with her piano prejudiced him against the classical repertoire, and he would never warm to pop or rock. His ideal was movie music, of which he soon had an encyclopaedic recall. Once he began making his own amateur films, he would noodle tunes on his clarinet, but only for Leah to transcribe for piano and record as soundtracks.

Shorn of friends and relations by the move to Arizona, and hungry for acceptance, Spielberg took refuge increasingly in showmanship. ‘I began wanting to make people happy from the beginning of my life. As a kid, I had puppet shows – I wanted people to like my puppet shows when I was eight years old.’ For the rest of his life, displays of virtuoso invention would alternate with attempts to create the suburban contentment for which he envied others.

Physical awkwardness remained his greatest humiliation. In a school footrace, he once found himself second last, only just ahead of an even slower handicapped boy. It was this boy the crowd cheered on, yelling, ‘C’mon, John, you can beat Spielberg!’ With the compulsion to win but also to satisfy the expectations of an audience that became characteristic of him as an adult, Spielberg contrived to trip so that the other boy could pass him. Then, once the other was well ahead, he threw himself into almost catching up, coming in a close last. John was carried off in triumph, while Spielberg, winner and loser at the same time, stood on the field and cried for five minutes. ‘I’d never felt better and I’d never felt worse in my whole life.’

In adulthood, Spielberg’s ideal social and intellectual level remained that of his life as a suburban schoolboy in the late 1950s. George Lucas was to have Luke Skywalker say of provincial Tatooine in Star Wars, ‘If there is a bright centre to the universe, this is the place it is furthest from.’ But for Spielberg, suburbia would always radiate a prelapsarian glow. He came to revere middle-class virtues. Richard Dreyfuss says Spielberg has ‘a love affair with the suburban middle class. I don’t share his fascination, but Steven could do whole movies about block parties if he wanted to.’ If he’d been making All the President’s Men, Spielberg said, he would have concentrated on the White House typists rather than the reporters. His favourite painter was, and remained, Norman Rockwell, whose covers for the Saturday Evening Post showing scenes of gentle whimsy, often set in churches, soda fountains and domestic interiors, exemplified a sunny vision of America as God’s Country.

A later writer was to sum up Rockwell’s style in terms that make clear Spielberg’s affinity for the artist: ‘At his peak, Rockwell reflected an American dream which did not at the time seem ridiculous or unobtainable — the dream of international power, domestic pleasure and civil tranquillity. Rockwell’s arcadia was peopled by clever kids, indulgent grandparents, bourgeois shopkeepers, shy courting couples and pious schoolteachers – all painted in a style which was a strange blend of fairy-tale, cinematic still and comic strip.’ Another critic wrote: ‘To be feeling good at home is the secret and desire of the world Rockwell narrates. “Home” is also his narrative horizon and his project. Having a comfortable, solid, lived-in home, being confident in oneself and one’s values, are everyday and prosaic values which are obvious, lived and shared. It is art for, and about, Joe Sixpack. It plays very well in Peoria.’ Spielberg’s lifelong fascination with Rockwell culminated in him becoming a collector of his works, and a trustee and major financial contributor to the Rockwell Museum.

Unlike the Haddonfield house, which was surrounded by trees, and in particular a large one just outside his window on which Spielberg focused his scarier fantasies, the house in Scottsdale was part of a modern development sprawling over flat semi-desert. Spielberg loved its sense of community, the way one could look into the kitchen windows of the families on either side. ‘You always knew what your neighbours were cooking because you could see them preparing dinner and you could smell it. There were no fences, no problems.’ In the nineties, ensconced in a mansion in Los Angeles’ luxurious suburb of Pacific Palisades, he still felt the same affection. ‘I live in a different kind of suburbia, but it still is. There are houses next door and across the street, and you can walk, and there are street lamps on the street and sidewalks, and it’s very nice.’

The Spielberg household placed a premium on work and hobbies. Leah would invite her musician friends for musical evenings. Steven was encouraged to have pets. He filled his room with eight free-flying parakeets which perched on the curtain rod and left their droppings underneath. He would continue to keep them as an adult, naming them serially, as he had as a child. In the seventies he still had a pair, called Schmuck I and Schmuck II. On holidays, his parents drove as far as the White Mountains and the Grand Canyon, pitching their tent and, particularly in Leah’s case, throwing themselves into serious hiking and nature study. One of Spielberg’s most vivid memories is of his mother on a mountaintop, whirling in ecstasy, and while shooting Raiders in Tunisia he reminisced of scorpion hunts with his father in the Arizona desert.

His first encounter with a movie camera sprang from these camping trips. Leah gave Arnold an 8mm Kodak for Father’s Day. He hosepiped like any amateur until Steven, sensitised by prolonged viewing of movies on TV, became impatient. After being criticised repeatedly by his son for shaky camera movements and bad exposure, Arnold handed over the camera. After that, holidays were never the same. His mother recalled:

My earliest recollection of Steven with a camera was when my husband and I were leaving on vacation and we told him to take a shot of the camper leaving the driveway. He got down on his belly and was aiming at the hubcap. We were exasperated, yelling at him, ‘Come on! We have to leave. Hurry up.’ But he just kept on doing his thing, and when we saw the finished results, he was able to pull back so that this hubcap spinning around became the whole camper – my first glimpse of the Spielbergian touch, and a hint of things to come.

A hundred yards before they arrived, Steven jumped out and filmed them driving through the campsite gate. After that, every part of the trip was recorded. ‘Father Chopping Wood. Mother Digging Latrine. Young Sister Removing Fishhook From Right Eye – my first horror film. And a scary little picture called Bear in the Bushes.’

1959 was a year of significance for Spielberg. References to it riddle his films. It was the year he was bar mitzvahed, only managing to mumble through his ill-memorised extract from the torah with the help of the old men in the front row, who muttered along with him. This was also the year he began actively to resent his father’s obsession with work, and his insistence on precision and order. His father brought home a transistor, and told him, ‘Son, this is the future.’ Spielberg grabbed it and swallowed it.

Detroit’s disastrous attempt at manipulating the American public by designing cars according to theories of subliminal sexual symbolism reached fruition in 1959 with the Ford Edsel. Spielberg used one of these doomed gas-guzzlers with its calculatedly vaginal front grille in his first film, Amblin’. One of the year’s big hits, Jerome Kern’s ‘Smoke Gets in Your Eyes’, revived by the black singing group The Platters, provided the theme of Always.

More important, CBS premiered a new half-hour TV series in October. An anthology of quirky science fiction or fantasy stories, each with an ironic trick ending, it was introduced each week, and often written by, its creator, TV writer Rod Serling, already well-known for original dramas like Requiem for a Heavyweight. In his dark suit and with his crooked smile and off-handedly intellectual comments, Serling, like Arnold Spielberg, was an ex-GI with a revisionist view of the America Fit For Heroes To Live In. Through the window of The Twilight Zone, he invited his audience to spy on a puzzling future with more than a hint of threat.

The Twilight Zone influenced not only Spielberg but a whole generation of film directors-in-waiting. Like them, he came running at the sound of Marius Constant’s theme, which he compared to a bugle call drawing one to the TV set. The tune inspired the five-note alien signature of Close Encounters. Spielberg would also attempt, unsuccessfully, to replicate the series, first in a film version, then on TV in the ill-fated Amazing Stories.

The family camera admitted Spielberg to his first real life of the mind. Here his skill was not in doubt. It gave him absolute control of a world. While other kids were involved in a Little League baseball team or in music, he was watching TV and, his phrase, ‘drowning in little home movies’. Once he exhausted the technical possibilities of the little Kodak’s single lens, flip-up viewfinder and thirty-five-second clockwork motor, he persuaded his father to buy a better model with a three-lens turret. Being able to cut from long shot through medium shot to close-up widened his horizons.

Over the years, his versions of his debut in narrative film have varied. Initially, he went off alone during a camping trip and experimented with shooting something other than the family. ‘The first film I ever made was… about an experience in unseen horror, a walk through the forest. The whole thing was a seven-hundred-foot dolly shot and lasted fourteen minutes.’ Story films quickly followed. ‘My first… I made when I was twelve,’ he says, ‘for the Boy Scouts.’ For the Photo Proficiency badge, he had to tell a story in a series of still photographs. Spielberg went one better with a movie, variously remembered as Gun Smoke or The Last Gun. A 3 1/2-minute western about a showdown between homesteaders and a land baron, it cost $8.50, which he raised by whitewashing the trunks of neighbours’ citrus trees at 75c a tree. Fellow Scouts with plastic revolvers played all the characters, and Spielberg persuaded a man with a cigarette to puff into the barrel of a gun so that the film could end on the sheriff’s smoking pistol shoved back into his holster. The Scouts loved his movie, and Spielberg got his badge. ‘In that moment,’ he said, ‘I knew what I wanted to do with the rest of my life.’

The instant gratification of story film influenced Spielberg against abstraction. ‘I think if I had made a different kind of movie, if that film had been maybe a study of raindrops coming out of a gutter and forming a puddle in your back yard, I think if I had shown that film to the Boy Scouts and they had sat there and said, “Wow, that’s really beautiful, really interesting. Look at the patterns in the water. Look at the interesting camera angle” – I mean, if I had done that, I might have been a different kind of film-maker.’

Until then, his record in the Scouts had been as undistinguished as that in high school. He couldn’t cook, was so hamfisted he never learned to tie knots well, and enlivened a demonstration of sharpening an axe by cutting his finger open in front of five hundred Scouts at a summer jamboree. He avoided weekend camps, which robbed him of his only chance to see a UFO; other Scouts returned from a camp in the desert with stories of a strange glow in the sky. But movies made him, if not popular, then at least accepted. He freely acknowledged that his first films were exercises in ingratiation. They gave him, he said, ‘a reason for living after school hours’. The school bully could also be placated by putting him in a film. He rented Davy Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier and War of the Worlds on 8mm, and showed them at 25c a head in the family den. As well, he sold popcorn and soda – an integral part of the film experience for him. The proceeds went to charity. The point, then as later in his career, wasn’t profit but popularity.

Over the next four years he made about fifteen story films. Old enough now to be allowed to see almost anything at his local cinema, the Kiva, he plundered Hollywood for ideas. Some of the lessons of The Great Locomotive Chase, Disney’s version of the Civil War raid on which Buster Keaton had based his classic 1926 comedy The General, were put into effect in Duel, and parts of Henry Levin’s version of Jules Verne’s Journey to the Centre of the Earth would be restaged for Raiders of the Lost Ark. One of the first films he saw which was not straight escapism was The Searchers. John Ford’s story of racist loner John Wayne searching for the niece kidnapped by Indians opened his eyes to the poetic possibilities of landscape. ‘I wasn’t raised in a big city,’ Spielberg says. ‘I lived under the sky all through those formative years, from third grade right through high school. That’s my knowledge of a sort of lifestyle.’ Ford, brought up on the imagery of Catholic paintings and ‘holy pictures’, instinctively employed aspects of the natural world as metaphors for mental and moral states. Dust represented dissolution; rivers a sense of peace and cleansing; silhouettes presaged death. Certain landscapes, like Monument Valley, were for him intellectual universes in miniature. Those weathered towers of limestone rising from the desert against a vast sky became the unalterable precepts by which honourable men must live. Spielberg would make his own pilgrimage to them in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, one of many films to exhibit a Fordian vision of the American west.

Frank Capra also returned to the screen in 1959 after eight years in the wilderness to direct A Hole in the Head, though neither it, nor the film that followed, A Pocketful of Miracles, a remake of his 1933 Lady for a Day, in which sentimental gangsters transform an impoverished street-corner apple seller into a socialite so that her daughter can make an advantageous marriage, rivalled Mr Deeds Goes to Town or Mr Smith Goes to Washington.

While his future colleagues in the New Hollywood like Brian De Palma were surrendering to the moral intricacies and multiple deceptions of Alfred Hitchcock or, in the case of Martin Scorsese, relishing the social disquiet behind Sam Fuller’s tabloid cinema and the pastel melodramas of Douglas Sirk and Nicholas Ray, Spielberg made Ford and Capra his models. Lacking a strong moral structure of his own, he absorbed theirs, populist, sentimental, reverent and patriotic. Never comfortable talking to actors, he adopted their technique too, employing landscape and weather as symbols of character, and developing a fluid camera style and skill in directing masses of people that swept his audiences past fragile narratives and sketchy characters. ‘Film for me is totally pictorial,’ he says. ‘I’m more attracted to doing things with pictures and atmospheres – the idea of the visual telling the story.’

In this state of mind, Spielberg also dabbled in theatre:

I was probably the only student director at Arcadia High School in Arizona who was allowed to control and put together a show. I did Guys and Dolls and brought the action, especially the brawl in the Hot Box, into the audience. I guess that’s kind of commonplace in today’s theatre, but then it was very strange to have people running up and down the aisles singing and acting. I got killed for it! Every critic in Arizona who could write said, ‘How dare he open up the proscenium and do this drivel in the audience. Guys and Dolls is meant to be on stage.’ I did the standards – Arsenic and Old Lace, I Remember Mama – everything you were allowed to do then.

Like many directors destined to work in sf and fantasy, Spielberg discovered the quirky magazine Famous Monsters of Filmland. Edited by Forrest J Ackerman, self-styled ‘Mr Sci Fi’, whose Los Angeles home contained the world’s largest collection of sf movie memorabilia, it celebrated horror film and its techniques with jocular reverence.

The wave of cheap science fiction films that was Hollywood’s response to the sf publishing boom washed through American cinemas throughout 1959 and 1960. Spielberg was banned from seeing the 1958 I Married a Monster from Outer Space, a relatively modest and reticent film despite its gaudy title, but went anyway, and was racked by nightmares. In particular he came to admire the work of Jack Arnold, who directed The Incredible Shrinking Man, It Came from Outer Space, The Space Children and The Creature from the Black Lagoon. The catchpenny titles disguised thoughtful exercises in imagination and suspense which made evocative use of natural surroundings and domestic interiors. The shrinking man in Richard Matheson’s story, exposed to fallout from an atomic test, dwindles away in an ordinary suburban home; the film’s menaces are a cat and a spider. In It Came from Outer Space, written by Ray Bradbury, aliens arrive outside a small desert township. The man who first makes contact with them, John Putnam, is an archetypal Spielberg character, an unassuming Jeffersonian natural philosopher and amateur astronomer who muses about the nature of the universe and the desert, to both of which he has a gently mystical attitude.

Spielberg shared the general enthusiasm for The Thing (from Another World), a rare example of a major director, Howard Hawks, dealing with an sf subject. The script also had an important pedigree. It was based on a story called ‘Who Goes There?’ written by John W. Campbell before he became editor of Analog. Like most of Campbell’s work, it is refreshingly iconoclastic. A crashed alien ravages an Arctic research station, smashing down the scientist who tries to befriend it. It’s left to a few tough professional airmen to kill it off and save the world. At the end, a reporter broadcasts the story, warning his listeners, ‘Watch the skies. Keep watching the skies.’

For all the film’s flair, however, Hawks’s right-wing paranoia always jarred. It’s to Arnold’s films (and Bradbury’s script for Outer Space) that much of Spielberg’s later work is traceable. After Close Encounters of the Third Kind was released, Spielberg asked Bradbury, ‘Well, how did you like your film?’ and explained he’d been inspired by It Came from Outer Space. Bradbury and Arnold’s idea, that alien visitors may be benign, and concerned mainly to return home as quickly and quietly as possible, would surface in both Close Encounters and E.T. The fathers of the ‘space children’ who discover an alien in a beachside Californian cave work on a nearby scientific project and share the dislocated life Spielberg knew well, and which he evoked in The Goonies. And while the Black Lagoon may only have been in a corner of the Universal backlot lake, the underwater footage shot in the crystal springs of a Florida park played so effectively on the sense of ‘something’ lurking below us where we swim that the aquaphobic Spielberg paid it homage in the opening scenes of Jaws.

From the start, it wasn’t the atmosphere of fantasy films Spielberg enjoyed so much as their depiction of alternative realities through model work, special effects and elaborate make-up. His sisters, resented because of the attention they drew from his mother, and thus away from him, became victims of his exercises in imagination. He would scare them by building his face into a horror mask with papier mâché made from wet green toilet paper, or would lurk outside the window of Anne, the youngest, and groan ‘I am the moooooon’ until she became hysterical. He convinced them that the bedroom closet hid the decomposing body of a World War II airman, then left it to their curiosity to peek in at the plastic skull he’d hidden there, with goggles over the eyes and a flashlight inside. After they had been terrified by William Cameron Menzies’ Invaders from Mars, which featured the disembodied head of the Martian super-mind, played by an actress with green-painted face, fringed with tentacles, in a glass bubble, he locked them in the closet, this time with an empty fishbowl within which, he said, the head would materialise. All these domestic horrors and more would be recycled in Poltergeist.

War films could be just as interesting as science fiction, providing there were elaborate uniforms, and plenty of buildings were blown up. Firms like Castle Films sold World War II documentaries on 8mm, and Spielberg used some of these as stock footage for a flying story called Fighter Squadron. Arnold persuaded Skyharbor airport in Phoenix to let Steven shoot a friend in the cockpit of a P-51. In 1960, inspired by his father’s purchase of a war-surplus Jeep, Spielberg made the forty-minute Escape to Nowhere, about a World War II American platoon evading a Nazi army in the Libyan desert. He found a few fake German helmets, put them on friends and had them walk slowly past the camera, passing the helmets back down the line so that it looked like an army. Leah drove the Jeep and created uniforms in Wehrmacht grey in which Steven costumed his sisters and friends, who were then machine-gunned and forced repeatedly to roll down a hill in the desert which stood in for North Africa.

‘There was always a camera in his hands,’ Leah says. ‘Once he took a big cardboard carton from the supermarket and cut windows and doors and took it in the back alley and set it on fire to film it. When we saw it, it looked like a real building burning. These are things that in retrospect you try to figure out, but at the time it just seemed normal. He was my first child, and having no prior experience I thought all kids played like that.’

Escape to Nowhere won a prize at the Canyon Film Festival – a 16mm camera. Knowing he couldn’t afford 16mm film processing, Spielberg traded it for a more sophisticated H8 8mm Bolex. At the same time, with a little help from his father, he got a Bolex Sonorizer, with which he could put a soundtrack on his magnetically striped film.

He began to have friends, nerds like himself with over-active imaginations. During the run of the dinosaur film The Lost World in 1960, he and friends mixed white bread, Parmesan cheese, milk, creamed corn and peas in a paper bag and smuggled it into the Kiva. Then they made vomiting sounds and dripped the mixture from the balcony. It started a chain reaction of vomiting. The film was stopped and the lights went up as the malefactors escaped down the fire stairs.

Other attempts at sophistication didn’t work. ‘I’ll never forget the time I discovered girls,’ he says. ‘I was in the fifth grade. My father took me to a drive-in movie with a little girlfriend of mine. This girl had her head on my arm, and the next day my parents lectured me about being promiscuous at an early age. My growing up was like a sitcom ABC buys for a season before they drop it.’ Never passion’s plaything, except where movies were concerned, Spielberg would have a chequered emotional life that headed inexorably towards a marriage Ozzie and Harriet Nelson would have envied.

By the early sixties, Arnold and Leah’s marriage was failing. Spielberg recalled Arnold storming out of the house, shouting, ‘I’m not the head of the family, yet I am the man of the family’ – a line he would recycle in Duel. Steven fled from the cold silences of the house to the cinema’s warmth. In 1962, he saw the film that was to inspire him above all others. David Lean had spent years in the desert making Lawrence of Arabia, a truly epic picture of a larger-than-life historical character whose acts were mirrored and amplified by the landscapes in which they took place. Robert Bolt’s dialogue was minimal – indeed minimalist; aphorisms, orders, insults, seldom more than a sentence long. This was Ford crossed with Capra, but mediated by Lean. For the rest of his life, Spielberg would rate Lawrence as the one true classic of his early film-going. ‘I really kicked into high gear,’ he said of seeing it, ‘and thought, “This I gotta do. I gotta make movies.”’

Single-minded as ever, Spielberg set out to make his first feature, a science fiction adventure called Firelight. He wrote the first draft of the script in a night; the story of scientists who, investigating lights in space, provoke an alien invasion during which the visitors steal an entire city from earth and reassemble it on another planet.

Every weekend for a year, Spielberg worked on the film with anyone he could cajole or bully into helping. No girl, no football games, no summer jobs diverted him. His enthusiasm and persistence were infectious. When he needed someone exploded in the living room, Leah opened cans of cherries and stood by as her son balanced them on one end of a board and had someone jump on the other. She never got the stains off the furniture. Once again the airport closed a runway for him. A local hospital where he had worked as a volunteer in his holidays lent its corridors for a shot, though Spielberg found the experience disconcerting. ‘I saw things that were so horrifying that I had to fantasise that there were lights, props, make-up men, just to avoid vomiting.’

Once he was finished, Spielberg edited the film to 140 minutes. Actors had come and gone over the year, but he persuaded students at the nearby University of Arizona to post-synchronise the speaking parts as he ran the film on a sheet stretched over one end of the den. The Arcadia school band recorded some music for it.

The result, though he now deprecates it as ‘one of the five worst films ever made’, was good enough to screen for an audience. He persuaded his father, who had already invested $300 in the project, to gamble another $400 for the hire of a local cinema. Spielberg rented a limousine to bring him to the theatre with Leah, who had cudgelled enough friends, relatives of the actors, ex-Boy Scouts and local film fans to fill the seats. Most stayed to the end, and Arnold pocketed $100 profit.

Spielberg’s entry into the cinema was also his exit from childhood and Phoenix. Arnold had decided on another move, this time to join IBM at Saratoga, ten miles from San Jose, near San Francisco. Almost immediately, they packed up, and set out for California.

3 Amblin’ Towards Bethlehem (#ulink_bdee857d-7dec-54a7-8a0d-7a103a27d5af)

Show business is high school plus money.

Hollywood saying

AFTER THE parched landscape of Arizona, Spielberg loved the hills and vineyards of Saratoga. But this move finally wrecked the rickety marriage of Leah and Arnold Spielberg. Arnold had barely finished sketching a design for the house he hoped to build when the couple separated. Leah returned to Phoenix and started divorce proceedings. The separation wrenched Steven, who developed insecurities about marriage and a sense of loss that would be reflected in his films, which are filled with sons seeking fathers and children deprived of their families.

Saratoga also exposed him to anti-Semitism for the first time. Unlike her parents, Leah hadn’t kept a devout household. Spielberg called their style of Judaism ‘storefront Kosher’. When the rabbi called, the mezuzah was put on the door frame and the menorah on the mantel, and removed after he left. Spielberg understood vaguely that his mother’s family fled from Odessa to escape pogroms. His first memory of numbers is of a man, one of a group his grandmother was tutoring in English, trying to entertain him by displaying his concentration camp tattoo, and illustrating by turning his arm to show how 6 upside-down became 9.

As a boy, Spielberg was embarrassed by his heritage. ‘My grandfather would come to the porch when I was playing football with my friends and call out my name in Hebrew. “Schmeul! Schmeul! Dinner’s ready.” They would say, “Isn’t that your place? Who’s this Shmoo?” I’d say, “I don’t know. It’s not me he’s calling.”’ To anyone who asked, his name was German. He resisted the pressure from his grandmother to conform to what he called ‘the Orthodox mould’, but at the same time the religion’s emphasis on family values fed his need to belong. As an adult, he became a classic Jewish father – and, sometimes, mother. Though no enthusiast for cooking, he would prepare Leah’s recipes at home, and occasionally get up early on location to make matzoh for 150 people, an almost sacramental act that reaffirmed the production unit as his surrogate family.

The America in which Spielberg grew up accepted racial discrimination as a fact of life. Medical and law schools operated quotas for Jewish students, and colleges had Jewish fraternities. One still occasionally encountered a discreet ‘Christian Only’ in ‘Positions Vacant’ ads. Many golf clubs operated a racial ban. Realtors wouldn’t sell houses in certain districts to Jewish families. ‘Neighbourhoods for [a Jew],’ wrote William Manchester, ‘like his summer camps and winter cruises, would advertise “Dietary rules strictly enforced.”’

In Phoenix, even as one of only five Jewish children in his school, Spielberg hadn’t stood out, but Saratoga was actively anti-Semitic. Pennies were tossed at him in study hall, and he was mocked so much in gym that he gave up sports altogether; admittedly no great sacrifice for him. The Spielberg house, the only one not to display lights at Christmas, was just a walk away from the school, but after he’d been bullied on the way home, Steven insisted Leah pick him up each day. Once, in fury at the slurs of a neighbouring family, he smeared their windows with peanut butter. Explaining his decision to film Alice Walker’s book The Color Purple, rather than choosing a black director, he would say, ‘I felt I was qualified because of my own kind of cultural Armageddon, even though as a child I exaggerated the pain – as all children will do – and I became the only person discriminated against in history as a child.’

Because of this discrimination, but from a lack of academic interest as well, Spielberg’s grades, never high, sagged still further in Saratoga. When he graduated from high school with a dismal C average, it was in the knowledge that no major college would accept him. And not being in college meant that he was eligible for the draft. ‘I would have done anything to stay out of Vietnam,’ he said. But this wish dovetailed so neatly with his ambition to become a film director, ideally before he was twenty-one, that they soon fused in his mind.