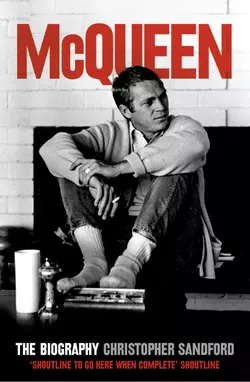

McQueen: The Biography

Christopher Sandford

A full and frank portrait of the complex man behind the icon of cool.This edition does not include illustrations.Steve McQueen, one of the first ‘cool’ film stars, remains a cultural icon the world over. His image is used to sell everything from cars, to beer, to a range of dolls. From the Cincinnati Kid to Frank Bullitt, Tom Crown to Papillon, his roles exemplified a certain school of male charm, as well as grit and a hint of menace.McQueen was born in 1930 into a poor Mid-western family to a highly strung mother and truant father. In and out of reform school from a young age, he was eventually made a ward of court and the resulting sense of abandonment never left him. His big break came with the TV Saga Wanted: Dead or Alive and the now cult-classic B-movie The Blob. Just two years later he was one of the leading lights of tinseltown.Sandford goes on to chart McQueen’s phenomenal Hollywood career, starring in some of the world’s best-loved films, in tandem with his turbulent private life: his marriages, his bisexuality, the drink, the fast cars, casual sex and violence. As a close friend has remarked: ‘You couldn’t peg him. He wanted to be memorable as an actor – but in his private life you got the impression he was trying to speed up, to get into the next hour without quite living out the last one.’As Sandford reveals, McQueen’s public demeanour of studied nonchalance hid chronic self-destrutive urges which emerged in his favourite hobbies, including bare-knuckle boxing and porsche-racing, as well as several suicide attempts. His ‘lost’ years at the very height of his fame are illuminated with disclosures of rampant addiction, bizarre health cures, fringe religion and androgyny. McQueen died in 1980 at a ‘wellness’ clinic in New Mexico, having been earlier diagnosed with lung cancer . His last words were ‘Lo hice’ – Spanish for ‘I did it’.Sandford has spoken to a wide range of McQueen’s contemporaries – Hollywood stars, friends and family – and discovered the man behind the myth, the abandoned little boy underneath the movie-god swagger.

McQueen

The Biography

Christopher Sandford

Copyright (#ulink_7c486c2c-21ea-598c-ab0a-3045762c1d5d)

Harper Non-Fiction

A division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsEntertainment 2001

Copyright © S. E. Sandford 2001

The Author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780006532293

Ebook Edition © JANUARY 2017 ISBN: 9780007381906

Version: 2017-01-13

For Robin Parish

‘The soul of the thing is the thought;

the charm of the act is the actor;

The soul of the fact is its truth, and the

NOW is its principal factor’

Eugene Fitch Ware

‘I’m a little screwed up, but I’m beautiful’

Steve McQueen

Table of Contents

Cover Page (#u04b205e1-19e0-5b1e-8059-ce05a0784885)

Title Page (#uc9327094-3538-5782-b724-0bd22f39948c)

Copyright (#u9b75861b-32eb-5b89-b4f1-274e05fa1310)

Epigraph (#u75864d07-1dca-5713-a0e9-ebe2d08f49d1)

1 The American Dream (#ua13ba9ab-b4ae-571a-9ae5-809c5b1fc45e)

2 War Lover (#uf738c26a-c56c-5f87-a8e9-8c462797bc4e)

3 ‘Should I lay bathrooms, or should I perform?’ (#ubb62b8bf-9549-5fdd-bd7c-2936fc5e3e0a)

4 Candyland (#ueb682037-37fd-5d30-9f04-29f99d9a28c6)

5 Solar Power (#litres_trial_promo)

6 The King of Cool (#litres_trial_promo)

7 Love Story (#litres_trial_promo)

8 Abdication (#litres_trial_promo)

9 Restoration (#litres_trial_promo)

10 The Role of a Lifetime (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

Appendix 1 Chronology (#litres_trial_promo)

Appendix 2 Filmography (#litres_trial_promo)

Appendix 3 Bibliography (#litres_trial_promo)

Author’s Note (#litres_trial_promo)

Sources and Chapter Notes (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Also By Christopher Sandford (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

1 The American Dream (#ulink_aba0e9c5-698a-5da4-b496-9d079c5d7686)

Steve McQueen was dead. It was a strange enough ending for a life that had scaled the heights of fame and plumbed the depths of depravity, laid out in a cold bare-walled room in a Mexican clinic. On this November morning a pale, watery sun came through the barred windows, sending chopped-up light onto the narrow bed. All the grief which marked the last year of McQueen’s life seemed purged by death. His eyes which, oddly, had turned dark grey were blue once more. In his hands was a Bible, turned to McQueen’s favourite verse, ‘For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish but have everlasting life.’ A doctor and a nurse both noticed the look that came over him at the end. It was the quizzical half-grin he made his own, that frighteningly unamused smirk at once attractive and not quite welcoming. Steve McQueen was himself again.

The king of cool had died at fifty. If the cancer hadn’t done for him, then a human agent had: according to McQueen’s doctor, it is ‘certain’ that a person or persons injected him with a fatal coagulant late on 6 November 1980, his final night alive. His patient was, he says, executed as he lay drugged and immobilised in a hospital bed. But no one should feel pity for Steve McQueen. He was neither broken nor bitter. Sick as he was, the happiest chapter of his life may have been the last one, in the care of Barbara, his third wife, flying his antique planes and slipping anonymously into church. He’d been living first in an aircraft hangar and then in a ranch with a big pot-bellied stove that filled half the room. Behind the house were fields and behind the fields were mountains. Here, in Santa Paula, California reminded Steve of the Missouri heartland he’d fled as a boy but never left. Here, the circle was complete.

A few other circles had been closed, too. McQueen’s first ever appearance on the big screen was as a prowling, knife-wielding punk. For his minuscule role as Fidel in 1956’s Somebody Up There Likes Me he earned $19 a day. Twenty-four years later, The Hunter ended on a poignantly downbeat note with McQueen spark out on a hospital floor. For that picture he made $3 million, plus 15 per cent of the gross. Running as a throughline in between, film audiences met one of the most arresting personalities in American art. Not too many others could hold a candle to McQueen’s striking affirmation of individuality. Far, far from the usual Hollywood pieties, Steve spent his off-duty hours dirt-biking or squatting in the desert with Navajo Indians. As a man, few ever came close to him. As an actor, nobody did. At his worst, McQueen gave off a quietly passionate sense of love and loss, eyes reeling with meaning, which perhaps promised more than it delivered. On peak form, he gave substance to even the thinnest plot. Not since the salad days of Brando had the words ‘movie’ and ‘star’ been in such proximity. Above all, McQueen knew that performance wasn’t a matter of right and wrong but of life and death – of the material. Jim Clavell, who worked up The Great Escape, would say that ‘Steve played suffering perfectly,’ since it chimed so well with his experience.

‘Lo hice – I did it’ were McQueen’s last known words. Towards the end, according to an orderly who was there, he ‘talked a lot about the early days, the farm, growing up and most of all reform school’. His nostalgia for the lost world of 1945 hid a grim truth: Steve had been committed by his own mother and her new husband. The squat bunker of Junior Boys Republic, the burr-cuts and bib overalls, the carbolic smell ground deep into the floor, the reek of the laundry – those were the stinking madeleines of his youth. And as McQueen lay dying, pressing ice cubes to his cheeks, doctors would hear him sob, ‘Three-one-eight-eight,’ over and over, his old school number of thirty-five years earlier echoing his fluttering heartbeat. Steve went out, if not with a whimper, then whey-faced for all the bewildered souls, not for his legendary groupies and least of all for Candyland, but for the ‘real folks’. For those who like their types cast, it was a quite heroic death.

They took him to the mortuary in Juarez, bumping along dusty roads where paparazzi from across the border already cowered behind trees. The Globe and Enquirer stringers squealed like game-show contestants when the car pulled in to the Prado Funerales. On that frenetic morning reporters were attempting to bribe medical staff with $80,000 for a shot of the corpse. In the end it was Paris Match who located McQueen’s body, calmly lifted the undertaker’s sheet and got off a picture for their front page. An orderly took exception and wound up rolling around with the photographer on the morgue floor. Later that afternoon the cortege made its way to the frontier town of El Paso, Texas, where a private jet stood fuelled and ready for the flight to Santa Paula. The sight of more press on the runway even as the plane revved up set off a round of groans and denunciations among McQueen’s friends. It was like the climactic scene from Bullitt. Two hours later they landed in California in thick fog. The plain Mexican coffin, flimsy for even his gaunt body, was loaded on a station wagon and taken to the Chapel of Rest in Ventura for cremation.

It was what McQueen had wanted, another perverse triumph. He’d always hated fires. He was nearly killed by one as a boy and in later years often had occasion to head-butt his demons. ‘You lookin’ at me?’ or a tart ‘Fuck you, candyass’ defiantly masked his inner terrors. Steve once ran through hot smoke to rescue his wife and young baby from a brush fire in Laurel Canyon. Drink and dope were balanced, for him, not only by fast cars but by constantly testing how he felt about himself and nature; and McQueen experienced that sense of challenge again in 1966, when he helped fight a three-alarm blaze at the studio. Ironically, the two worlds of fact and fiction finally merged eight years later when, at a routine briefing with the technical adviser on The Towering Inferno, McQueen responded to a real-life emergency by suiting up to save yet another torched stage. On that occasion a fireman looked over his shoulder, started and blurted out, ‘Holy crap! Steve! My wife won’t believe this.’ ‘Neither will mine,’ said McQueen calmly.

The body was burnt, and the ashes placed in a cheap urn. Steve had wanted ‘nothing fancy’ for himself, and he was famous for his spartan tastes – a can of Old Milwaukee was fine by him. Especially towards the end: by then, instead of goons and gofers, McQueen was keeping company with a distinctly rough-hewn crew of local barnstormers and pilots. Together they shared hobbies and traditions that were already old when Steve was born. They had an overriding love of keeping it simple, and many was the night they sat around the hangar, drinking and hugging themselves against the cold, whooping it up at Hollywood. This new McQueen was, above all, ‘real folks’, which is to say much the sort of person done on screen by the old McQueen. He favoured flying the flag in every school, early nights, and affirming the sanctity of marriage. That never ruled out a beer or a smoke. As for protocol, he didn’t overdo it. McQueen’s language was famously earthy. As far as acting went, he felt as if he’d pissed away about twenty years, wondering aloud what the fuck he’d been doing in half his films, although he always cashed the cheques. ‘You know, guys,’ Steve would say, squinting up at the snowy Rafaels, ‘I only really feel horny when I’m flying.’

They took the urn up in McQueen’s favourite antique Stearman, headed for the coast and scattered his ashes over the Pacific. That big bug. He’d loved it almost as much as he loved wheels. Fumes and altitude, the part of the American dream that went high and fast. Up there in the yellow biplane all the lines and wrinkles and what Steve called ‘broken glass’ were dissolved, blown away in the alpine air. They’d watched him, Sammy and Doug and Clete and the other flyboys, as he’d climbed sheer gradients, swooping with wild speed, and, just as fast, pulling back, rushing headlong towards the mountains, then levelling out at last towards the trails that went up into the hills and the clear sharpness of the peaks beyond. He would waggle his wings and it was exciting to him as though he were living, or at least exhaling, for the first time. That and the ranch and the silvered grey of the sagebrush, the quick, clear water of the Santa Clara and the missionary church were the sights and sounds he’d chosen for himself at the end. He’d always had a great imitative style, attitudes and poses associated with other people. But for the last year at least, Steve McQueen was playing himself.

That flight in the Stearman was a defining symbol of McQueen’s real breakthrough: that worldly success, for which he’d fought the System like two ferrets in a sack, was yet more ‘shit’. He was back to basics. Fire, air and sea were the true representation of Steve’s own words echoing down his last year – ‘Keep it elemental.’ His friends said a prayer for him over the water and came back low across the channel to Ventura. On McQueen’s orders, there was no grave or marker of any sort. His widow moved out of the ranch to a remote cabin in Idaho, and the plane and McQueen’s other goods were mainly given away. That, too, chimed with the ‘poor, sick, ragged kid’ who was father to the man.

Even Steve’s latter-day humility wasn’t enough to protect his cherished privacy. They came from all parts looking for clues, fans and paparazzi alike, doorstepping the ranch and swarming round his figure – soon removed by curators – at Hollywood’s wax museum. More than a few straggled back to the clinic, but none pierced the narcotic smog of medical debate, especially on the knotty subject of ‘alternative’ cancer treatment. Certainly nobody seriously floated the idea that McQueen had been murdered.

William Kelley, a one-time Texas dentist who apparently cured himself of cancer and went on to found the impressively styled International Health Institute, first treated a man posing as Don Schoonover in April 1980. ‘I told Schoonover – who turned out to be Steve – what he had to do. Sure enough, he began to get better…Six months later McQueen was in the clinic in Juarez and wanted to have his dead tumours surgically removed. I advised him of the risk, but Steve, being Steve, insisted. “I’m going to blow the lid off of the American cancer-treatment scam,” he told me. The medical establishment was freaked, shit scared of being exposed by a man like that. I was there the last night of his life, and I know what happened.’

A gutsy pioneer and whistleblower, or a demented nut? When Kelley started his institute, he had no surgical and little enough medical kudos. Even his orthodontist’s licence had been suspended after people complained that he was more interested in treating other health problems than in straightening teeth. A court injunction then briefly stopped publication of his book, One Answer to Cancer. By 1976 Kelley was being investigated by more than a dozen government agencies. For several years he and his wife moved onto an organic farm in Washington state, fantasised as a place of old-fashioned ideals, perfect peace, happiness and wholeness, with good vibes for all. He sold vitamins.

At this stage Kelley expanded his mail-order business and began hawking a ‘nonspecific metabolic therapy’ programme to patients disillusioned, like him, with the American Medical Association. His staggeringly complex nutritional regimen had some striking successes. Nobody knows exactly how many people are alive today because of him. However, after co-leasing the clinic in Mexico, Kelley achieved a series of remissions and apparent cures in even terminal cancer cases, McQueen allegedly among them. Both nurses and surgeons agree that the tumours removed from McQueen’s body were themselves already dead – ‘like cotton candy’, Kelley explains. ‘Steve was cancer-free for the last six months of his life. He died, pure and simple, of an induced blood clot.’ The accusation comes from a man, it has to be said, whose diet- and enema-based remedies landed him on the American Cancer Society’s blacklist. Some of Kelley’s deathbed scenario is also, like his therapy, nonspecific, but when his last doctor says ‘Steve was done in,’ you can be sure it’s because he believes it and not because of some slick dash he’s trying to cut. It would be astonishing if a freelance American celebrity like Kelley were vanity free, and he isn’t. With his treatment of McQueen already on record, he makes sure that people know of his other accomplishments – that he’s survived attacks by the FBI and the CIA, along with the ‘enemy Jew-controlled establishment’, for over thirty years. If Kelley’s racism repels, there’s still another strain in him that attracts as well. He talks fast, with a wheedling energy, but also with a wry humour and a string of wisecracks. Above all, he was there when Steve needed help, almost certainly prolonged his life, and was intimately involved in the events of 6–7 November 1980. Kelley may be a radical; he’s no nut.

Why did McQueen turn to what his first wife, at least, calls the ‘charlatans and exploiters’? The question still fascinates Hollywood’s ruling class who, for the most part, stood in such awe of him. Possibly because he felt so marginal – he never met his father and barely knew his mother – McQueen had the lifelong need to feud, to ‘twist people’s melons’, as he put it. Intrinsic to nearly everything he did was the sense of proving both himself and others. The truculence became part of this pattern, and any attempt to separate it from the gentler, mature Steve would split what’s indivisible. Throughout his life he was a cynic sometimes made credulous by his urge – almost a pathological need – to wing it. And McQueen would have automatically been well disposed towards anyone who, like Kelley, was at war with the world.

Sam Peckinpah, a man whose wit outlived his liver, put it best: Steve was every guy you didn’t fuck with. There are various mysteries about McQueen, shy kid and adult male equivalent of the Statue of Liberty, the chief one being that he seemed to be several different people. He was the insecure boy who didn’t much like being famous. Mostly he liked being alone, driving a straight ribbon of blacktop through the canyon dirt and past the lemon groves and orchards down into the desert. He loved the open spaces. Animals he usually tolerated but didn’t trust. People were ‘bad shit’. If there was any fellow-feeling, it was towards those he saw as other loners. There was the pill-popping and grog-quaffing McQueen who worked out three hours daily in the gym. There was the loving husband who boasted of ‘more pussy than Frank Sinatra’ on the side. There was the dumb hick (his phrase) who fought the studio system to a draw. The charismatic man who brought oxygen into a room. The last true superstar. The great reactor.

McQueen was the character who revels in his rebelliousness, the larger-than-life stud and free spirit who was actually a martyr to self-hate. During the periods when he wasn’t working Steve would get monumentally wasted, one of his typical pranks being when he stopped exercising and drank or snorted himself into oblivion. The pattern became a familiar one. While there was a suicidal component in some of these binges, McQueen didn’t actually want to die – the need for revenge was still too powerful for that. But he depended for his survival on a small but fanatically loyal gang of old friends; and his rude health. When most of those went south, and he made a genuine if tardy conversion to God, it’s not surprising McQueen pondered his options with Bill Kelley.

In the late 1960s, when Steve reached adulthood and suddenly realised he didn’t want to be there, the inverted world of movies was a wonderfully soothing place. McQueen’s personal myth, what he called his mud, ran to the bitter end. Many of the actual parts played were laughably weak, but McQueen was better than his scripts. Character counted with him, because in the end character was all there was. More than anyone, he knew that films exist in a kind of delicate balance with their moment. They can, sometimes mysteriously, either catch or miss their time. His own defining eloquence – a combination of the tough and the goofy – spoke directly to the embattled, mixed-up spirit of a war-torn republic. No one did the Sixties better than McQueen. He was, said Frank Sinatra, who would have known, ‘absolutely the greatest Zeitgeist guy. Ever.’

The designation was hard won. Obviously he wasn’t someone, like a De Niro, who physically aped his characters. The question of full-scale possession remains. All the fear and doubt and past experience McQueen brought to bear only heightened the surface dazzle of his cool under-playing. He didn’t call it a method: it was a policy, a life-plan of realism that was simply a part of him. It was also a good way for him to ‘twist melons’.

Karl Maiden remembers a scene he did with McQueen in The Cincinnati Kid. ‘Steve came on, in character, to confront me about whether I was double-dealing cards. He sprang at me like an animal. McQueen was prowling around the room where we were shooting, and he was absolutely terrifying. His fiery blue eyes were covered with an electric glaze and he was whipping about like a loose power line. He was so tense, I felt like I was gonna see an actor blow up for real…I mean, I was in awe of him.’ And this was a tough guy himself, who’d worked with Brando.

His aggression! People who knew and even loved Steve still marvel at it. It consumed him. The actor Biff McGuire remembers an odd and touching instance of it on The Thomas Crown Affair. This particular take called for McQueen to chip a golf ball out of a bunker, something that could have been done in a minute using a double or some other trick. ‘Steve toiled away at the shot most of the day, trying to hit the ball – going off to rest after a while, but then drawn back to it, totally focused on the job. He’d swing over and over and the ball would dribble up just a few inches and roll back in the pit again. Sometimes the director and crew would encourage him, but mostly I remember him alone, with that blinkered “Don’t fuck with me” expression of his, the club poised, then down, and the little shower of sand would spurt up. But everyone knew Steve would get the ball on the green, and in the end he did.’

He must have holed out just in time for his next – and best – picture, Bullitt. McQueen’s long-time friend (and sidekick in the film) Don Gordon was on location with him in San Francisco. ‘As well as kicking against the producers and suits generally, Steve applied his monster talent for competitiveness every night. First, he had both our motorbikes secretly shipped up from LA – secretly because the studio would’ve thrown a fit. He stowed them somewhere in a private lock-up. Around five every evening, just as the spring light was softening, Steve would yawn and announce he was turning in early. An hour later we’d meet at the garage and zip up into the hills, just the world’s biggest movie star and me, Steve thrilled like a kid breaking curfew but his edge immediately taking over.’ Gordon would good-naturedly watch McQueen put the throttle on and roar off into the dark. He ‘took it hard and fast because he was damn good, but also because he was stoked by knowing someone else was right behind him. I mean, Steve had to win.’

When McQueen died, more than twenty years ago, there was still a mythical America; an individual could still wrap himself in that myth. A large part of the legend had already gone Hollywood – not least in the lens of a John Ford or Frank Capra – before McQueen, but he also created his own. Vulnerability, decency and a real sense of menace all combined to fix him as the ‘new Bogie’, although Steve’s on-screen chemistry with women was the more toxic of the two. Some are put in mind of the ‘torn shirt’ school epitomised by Montgomery Clift and Brando, though McQueen’s reputation was always based on rather more than a few grunts and stylised nasal tics. With rare exceptions, he kept upping the risk, enlarging the dimensions of his own performance both on screen and off. Each of Steve’s roles was a grander and more precariously improvised adventure of the mind. His tragedy was that he could neither change the world nor ignore its creation of him. But it made for a life.

McQueen was able, out of his arrogance, to do something which was selfless. Of course he cashed the cheques, but in the best roles he created the walk, the look and the presence of the truly universal. Steve McQueen’s is the story of our time.

2 War Lover (#ulink_a559083a-8a8e-5636-900a-d7df6159844c)

Many of Steve’s first memories were of machines; they seemed to exert a pull on him from the start. They stood out, conspicuous against the human world, notable for their tireless, solid qualities, their efficiency, their resilience and power. They seemed responsive to his touch, and they were rational. He quickly found his place.

His time, early spring of 1930, was one of uneventful peace brooding over Europe. Britain grappled with its perennial labour and sterling crises and the worldwide trade slump, both cause and result of the Depression. The sovereign people of the US still lumped it under President Hoover, Advisory Boards on everything from Reconstruction Finance to Illiteracy marking the real beginning, three years pre-Roosevelt, of the New Deal. Yet, if lacking in surface drama, 1930 was still a turning-point, with two or three events of real long-term significance. In Germany the first Nazis took public office; on the sub-continent Gandhi began his civil disobedience campaign, with all the dislocation that entailed; and in the American rust-belt Steve McQueen was born.

It was a grim enough time, an icy 24 March, and a grim enough spot, the Indianapolis suburb of Beech Grove. He was delivered at ten that morning in the branch hospital, hard by the Conrail depot, where shabby passenger cars came to be fixed. Among the first sounds he would have heard were of engines. Everywhere more and more machinery was grinding: the city mills were still running at full bore and coal was being quarried in record weight. The factories blasted night and day; the clang of iron plates made a thought-annihilating thunder. The stockyards sent up a thick reek, wooden shacks standing beside animal swamps which bubbled and stank like stewing tripe. Dirty snow hillocks formed along the kerbs and sewage water ran raw and braided in the gutters. The inner slums, like Beech Grove, were already long since pauperised. Even the leprous hospital block was half-enveloped in weeds. This was the place, full of blood, stench and the sulphurous glare of the railyard, that fixed itself in the young boy’s imagination.

It’s often said that McQueen lived five lives, the juvenile and late years and one time around with each of his three wives. Like many people he used to wonder whether, in the last resort, those mewling early days weren’t the happiest and best. ‘I remember running in the hog yards…My people had this big field. And I’d come lighting out from school and play [there] and I remember how buzzed I felt.’ In later life Steve was skilled at softening hard memories with happy stories. His nostalgia for the 1930s and 1940s masked the grim truth that he was odds-on illegitimate, very probably abused and certainly unwanted. The experience left McQueen with the unshakable conviction that he was ‘a dork’, a friend explains. ‘He always described himself exactly that way. Steve was very sold on his being damaged goods.’

His mother, Julia Ann Crawford, known as Julian, was a nineteen-year-old runaway and drunk. In 1927 she’d taken off from the family farm for the city. Julian was blonde and pert, an apparently stylish and independent woman, if not the model of sanity. On closer inspection her very face was demented. Julian’s eyes, small and dark, suggested a substitute set of nostrils at the wrong end of her nose. At moments of excitement her head would loll wildly. She soon made a whole lifestyle out of being fractious. For a while it was only semi-prostitution, but before long Julian was dancing the hoochy-koochy and swigging ‘tea’, which she fortified from a silver flask in her handbag. Lipstick smudged across her pasty cheeks, face drawn, arms frail, black dress cinched round her thighs, stockings rolled down, she lurched from partner to partner, half gone but occasionally soaring into a shrill, manic high. The city authorities often called for her. Long before bi-polarity had a name, Julian was screwing herself in and out of madness.

In June 1929 she met and bedded an ex-flyboy named Bill McQueen. Steve’s mysterious father was one of those old-time rowdies who bent iron bars, pulled trains with their teeth or barnstormed at county fairs. All that’s known of his early days is that he flew in the navy and later toured North America with an aerobatic circus. Aside from drink, his two major loves in life were of planes and gambling. On his twenty-first birthday Bill came into a windfall of $2000. He took the cash and opened an illegal casino called Wild Will’s below a brothel on Indianapolis’s Illinois Street. After the club folded he became a drifter and an alcoholic. Around 1928 he began to suffer so badly from liver attacks and heart trouble that his doctor had to dull the pain with morphine. That set up yet another vicious circle of addiction. By the time Bill met Julian Crawford he was a sick man, in his late twenties but prematurely aged, with death all over him. They lived for a while in a rooming house, riding the trolley down to Schnull’s Block, the commercial zone, looking for work. None ever came. When Steve McQueen was born the following March, his parents had to apply for funds under the Poor Law. Julian took Bill’s surname, though there is no evidence they ever married. The father took off one night six months later, leaving the mother and son in a dismal hotel downtown. Bill came back once, a few weeks later, asking to be forgiven. Julian kicked him out.

Bill headed for the hills.

Steve’s claim that ‘my life was screwed up before I was born’ might be mawkish, but there’s no denying the shadow cast by this earliest ‘shit’, as he called it. Right to the end, he often quoted The Merchant of Venice, ‘The sins of the father are to be laid on the children’, sometimes substituting ‘of the mother’. The rich, famous and fulfilled man the world saw still considered himself a freak maimed for life by that early catastrophic shock.

In both manner and matter, McQueen was firmly tied to the fate of a bastard child of the 1930s. He rarely or never trusted anyone, and knew the value of a dollar as well as a crippling sense of doubt throughout years that were gritty and filled with struggle. It was a new world he grew up in, unique to the place, peculiar to the time; and, his friend confirms, ‘always, to Steve, something of a cross’. On the very morning he was born the weather broke in a filthy shawl of snow. Back in the rooming house the pipes had to be thawed with blow-torches while Bill brooded over his bottles. By day thick fog descended, leaving spectacular rime deposits on Market Street. At night the White river froze solid and the cold seemed to have the pygmy’s power of shrinking skin. Even in early spring, few of the locals ventured beyond the narrow confines of the city canal. Trains would haul freight and animals east, but rarely people. Some did claim they liked to travel, but they meant to Chicago perhaps, 130 miles north, or that they once visited St Louis. Indianapolis had few illusions about ever becoming world class. It was the typical submerged existence of the poor; people accepted it, hardly realising that their destiny could ever have been different. In short, it was the kind of place that teaches a boy to be practical while it forces him to dream of other, headier realities.

The past slowly faded: Civil War veterans, though a few still held court in Military Park; Indians, first as names and then as faces; even the great Jazz Age of the twenties. Culture in the Midwest was a marginal enterprise. The news that March Monday in the Hoosier Star was of Hitler, Gandhi and Stalin, and closer to home of Indianapolis itself, where the talk was of unemployment, foreclosures and the Ku Klux Klan. On the 24th fiery crosses burned on Mars Hill and the downs around Beech Grove, and the Catholic cathedral was pipe-bombed. Thugs terrorised Jewish shopkeepers. That long winter’s gloom wasn’t just climatic; it acted on the streets and the houses, but also on character, mood and outlook. It was a powerful depressant.

Nineteen-thirty was also, on another level, a time of mass escapism. The old music halls had gone, but the dramatic heart of the nation started up again in the movies. Sixty million men, women and children paid at the box office weekly. Mummified ‘flickers’ were fast giving way to modern production values: widescreen action in general and the Grandeur process in particular were blazed in 1930’s The Big Trail, starring John Wayne. The Depression would prove to be Hollywood’s finest hour. Disraeli, The Blue Angel and All Quiet on the Western Front were all soon playing amid a relentless diet of Dracula and primitive adult and slasher films. That same March Al Jolson opened in Mammy, while Garbo’s first talkie, Anna Christie, started out as an epic and soon mutated into something more, a picture Julian herself saw every night for a week. Between times, she would trudge with Steve to the downtown Roxy or sneak into the Crescent ‘colored house’, full of smoke, chrome and low-budget flickers which faded away to reveal the main visual drama – punch-ups and, in not a few cases, lynchings in the surrounding ghetto dealt out by the Klan. It was here that McQueen first made the acquaintance of sex and violence.

Meanwhile, more and more concerned women’s groups said that children could not be trusted around a cinema.

And yet the Daughters of the American Revolution probably weren’t unhappy. They had one cause of never-failing interest, and that was censorship. That same year Hoover established the Motion Picture Production Code, the so-called Hays Office, to police a growing trend towards blasphemy or crude Scandinavian naturism. Later in 1930 Loew’s on Meridian Street was actually raided during a live illustration of ‘civic hygiene’ involving two women, a tub and their silk smalls in a striking combination. According to the deadpan police report, ‘The sexual parts, around which the pubic hairs seem[ed] to have been shaved off, [were] clearly visible and so imperfectly covered by the wash cloth, that the lips bulge[d] out to the left and right of the towel…The glands were uncovered.’ Mae West’s celebrated trial on a similar morals rap opened in New York. This early, seminal association of the lively arts with sex and rowdyism was one Steve soon learnt and never forgot. Play-acting would give him the licence to be dirty, sweaty and lewd, the licence to get even, to make the real world vanish – and, eventually, to blow town. Once he started emulating the hoary two-reelers from Hollywood, it was only a matter of time for him and the rust-belt.

The pre-war decade was also a great flying era. Stunt pilots, barnstormers and wing-walkers attracted crowds undreamed of in the 1920s. Air displays sold out. In the same three-month period Charles Lindbergh and his wife set a transcontinental speed record, Amy Johnson made the haul from London to Sydney and Francis Chichester brought off the first solo crossing by seaplane from New Zealand to Australia. Bill’s intense devotion to this world reflected the same recklessness his son later experienced in drinking, drug-taking and dirt-biking. Like his father, Steve put himself on the line, on-screen and off; he dared all and he ‘went for it’ until self-destruction, or a sense of parody, kicked in. His whole career was the celluloid equivalent of the Barrell Roll. Long before he went aloft in his own vintage Stearman, McQueen had already flaunted his patronymic DNA – what Julian called the ‘butch, brawling, ballsy’ school of life. The winging it.

Born to poverty and bred to insecurity, Steve soon thrived on loneliness. He could never pinpoint how old he was when he first began to feel wretched in his own skin, but the critical scene haunted him the rest of his life. Running upstairs to the dive he shared with Julian, he suddenly heard her screaming, ‘hollering and howling [like] she was bein’ done in’ but accompanied, curiously, by gales of mirth from the neighbours’ stoop. His mother was in bed there with a sailor. ‘We ragged him,’ says a childhood friend, Toni Gahl. ‘Steve was very sort of geeky in those days. He was dirt poor, wore britches and Julian was no more than a prize slut. The other kids were down on him.’

So, suddenly, life became bewildering, and before he could even read or write McQueen was a reformatory case. His fate to always be the outsider was blazed early on. He was old enough to know he was ‘trash’, and young enough to dream about being part of a fantasy world in the movies. An imaginative, hyperactive child who would always rather be elsewhere, doing something else, Steve came to hate his mother even more than his runaway father. Every night he wandered among the drunks and rat-infested garbage while Julian turned tricks in their bedroom.

McQueen’s later binges were also a legacy of Bill’s – and Julian’s – world. What went into his movies was part of what went into his monumental craving for sex and drugs. The plethoric screwing, in particular, wasn’t normally for fun or pleasure; nor, says a well-placed source, was it ‘likely to thrill the girl. Steve was very much a wham, bam guy, not the kind to pour sap about love in your ear.’ That, too, echoed his father (motto: ‘They’re all grey in the night’), whose mark was in the boy’s marrow. His very names, Terrence Steven, were in honour of a figuratively legless, literally one-armed punter at Wild Will’s. The ‘McQueen’, from the Gaelic suibhne, meant ‘son of the good or quiet man’. As a derivative it was strictly out of the ironic-name school, and in fact, two choicer words could hardly be used to describe Bill. His own father had been a soldier, from a family of soldiers or sailors, who had moved from Scotland around 1750. By the early nineteenth century the McQueens were living in North and South Carolina before fanning out west at the time of the Civil War. An Arian (the ‘me’ sign), Steve was by a neat twist, within a few weeks’ age of both Sean Connery and Clint Eastwood, the three great ball-clanking icons of their era. The 24th of March was also celebrated in ancient Rome as the Day of Blood. Any child born that day was likely to be punished by an early death.

Julian’s people were devout Catholics and tradesmen in Slater, Missouri, gently rolling farm country midway between Columbia and Kansas City. For most of the 1930s she and Steve would shuttle from Indianapolis to the heartland and back, boarding with her parents and fostering an arbitrary highway persona, equal parts brief, ad hoc arrangements and cyclical transience, which he never broke. Much of McQueen’s on-screen insight came from the highly imaginative and disturbed five-year-old who once clutched his mother’s hand in genuine perplexity:

‘What’s wrong with us?’

Julian remained mute.

‘I’m starving, Ma.’

Julian was unaware of it at the time, but he was consumed with envy when he compared life even to that of the other slum kids in the city. Most of his peers were living in semi-comfort, while he had to content himself with cast-off clothes and meagre, wolfed-down meals. Toni Gahl remembers that Steve ‘didn’t say a lot. Basically he was pretty much of a clenched fist.’

Around mid-decade things, already apparently at their darkest, would turn black. Julian’s father went broke in the slump and he and his wife moved in with the latter’s brother Claude Thomson, a hog baron with a prodigious appetite for moonshine and also, with that spread, catnip to the ladies. The next time the bus pulled in from Indianapolis, Julian and Steve also joined the displaced family. Claude lived on a 320-acre farm on, aptly, Thomson Lane, three miles out of Slater by Buck creek. It was as near to a fixed childhood home as Steve ever had. He spent eleven years there on and off, sometimes with his mother, more often not. A woman named Darla More once saw him, head down, tramping alongside the Chicago & Alton railway between Slater and Gilliam. ‘Steve was just a poor, sad, fatherless, mixed-up kid. I don’t think it’s possible for a human being to look as absolutely beat as he did at that moment.’ More sat down with him and learnt that Julian had left for Indianapolis, without bothering to tell her son, the night before. ‘Steve slumped there on the tracks and wept his eyes out. It sounds corny, but I promptly went and picked a flower to cheer him up and gave it to him. I still remember the smile Steve flashed me back.’ When alluding to the scene in later years, McQueen himself would sometimes choke and have to compose himself.

In all, Steve grew up in ‘about twenty different shacks and dumps’, he said, and his imagination seems to have provided more richly furnished accommodations. There were any number of lifelong connections from that era, but a handful beat a straight path to sadomasochism: watching Julian casually come and go, for example, her soft, fat lips, her assertion that fun was more important than family.

Neglected by both parents, he was raised in large part by a man who ran the farm with a mixture of shrewdness, opportunism and brute force. Husbandry in those days was an often violent business, and they did have gangsters in Missouri. In fact, the only mention of crime in the Slater paper for Christmas 1933 records a sorry fall from grace: on 24 December two men shot at a third after catching him interfering with a sow. Although Uncle Claude owned several guns, there was no suggestion that he was tied up in this scandal. He did, however, protect his own, worked all hours and drove a hard bargain. All through the Depression he made a good living, becoming one of Slater’s richest men. Unfortunately, he was also an alcoholic whose great-nephew, for all the Catholic ritual and dogma his family tried to beat into him, grew up virtually wild.

Accordingly, Steve stood far closer to the moonshine than to any holy sacraments. By contrast, Julian’s mother Lil was a religious nut and disciplinarian said by McQueen to habitually ‘spit icicles in July’. She fussed around the white stucco home (first in the county to get electricity), a rambling pile with sixty-five scalloped windows and endless corridors, all lined with bad paintings and an occasional life-size nude. What Claude Thomson had in cash, he lacked in class, the threadbare rugs and wooden pews (to give things a churchy feeling) contributing to a kind of mingy staleness. Despite all the glass, the farm had a dark, gothic feel, grimy paint and heavy mahogany mingling with a reek of dishwater, slops and Lil’s speciality, garlic, oozing from the kitchen. Everybody muttered about private grievances and never shared. In an unresolved row over money, Claude soon evicted his sister and her husband, who moved into an unlit railway car put up on blocks in a neighbouring field. When Lil was later widowed, her brother promptly had her committed to the state hospital for the insane.

Slater itself, of 4000 souls and a single stop-light, was inhabited by cadaverously thin men in overalls working the land for soya beans, by the peculiar musty stench of the loam and salt deposits, by defecating hogs and ancient trucks beached in front yards, by fire-and-brimstone preachers and illicit stills and funereal hillbilly music drifting up out of tomb-dark shacks. Local politics were a depressing spectacle, most attitudes pre-Lincolnian, race relations fundamental. Tradition was all. The place boasted twenty-one Protestant and two Catholic churches. Behind these lay the wheatfields and the occasional plantation, like Claude’s, in a grove of trees; obviously places of pretension at one time. The whole area was a throwback to a vanishing America. As for the people, they may have been, as Claude said, ‘no Einsteins’, but for the most part they possessed a certain earthy frankness. They were also capable, gruff, and kissed up to no one, including a new, ‘dorky’ arrival. Steve now knew what it was like to be shunned in two communities.

The trouble grew worse each year, especially after McQueen worked out the full truth of his parentage. From the start, though fully alive to the gossip, he’d been determined to ignore it, to ‘shut [himself] down’. At first there were only whispered reports; the locals simply looked away when he walked by. Returning along the trail that led across the creek to town, deep in the green shade of the thickest part of the prairie-grass, Steve was regularly aware of the same group of boys sitting at a turn of the road, at a place just before it led up the hill to the railroad and the shops. They squatted between the cottonwoods, quietly talking. When he came up to them he’d keep his head down, and they always did the same, remained silent a moment until he’d gone by, then nudged each other and hooted out, ‘Bastard!’

By the time Steve was six or seven, this already tense scene gradually gave way to violence, and verbal abuse degenerated into punch-ups. One local teen known only as Bud once spat at him as he walked by on Main Street. The response was dramatic. Quite suddenly, McQueen’s indifference ended. Vaguely, Bud remembered one of the other boys screaming and then felt a cracking pain as he went down on the kerb. There was another blow, and blood began to spurt out all over his face. A wiry meatpacking arm began to flail downwards, and with one hook of his left fist, Steve split the much older boy’s nose. Two passers-by, fearing he’d brain him, started yelling, ‘You’ll kill him, Mac! You’ll kill him!’ and dragged McQueen off. The police were called.

Steve would later attend a small, all-white school, where his aggression was matched by sullenness. For the most part his hobbies were solitary, his companions subhuman. So far as he ever let himself go, it was with a series of animals and household pets – his best friend was one of Claude’s hogs – with whom he abandoned himself in a carefree display of emotion, an uninhibited effusion of irresponsibility, happiness and love. He also, says Gahl, ‘dug anything with wheels’. Within those massive confines, it wasn’t a bad childhood, merely a warped one. First Bill’s and then Julian’s defections were a blow that helped to shape, or did shape him, making him tense, hard-boiled and edgily single-minded. He had his code worked out. People were swine; performing for them was simply to rattle the swill bucket. The sense of parental love which nourished even a Bud was shut off totally. On the other hand, McQueen learnt the value of self-help early on, and in the one surviving contemporary photo of him, taken in the pig-pen, he’s tricked out for the occasion in boots, bib overalls and a wide grin. Striking a pose that’s at once studied and casual, he leans against a trough with his knees slightly bent, as if ready to spring into action the moment the shutter’s released: finishing his chores early would earn him a bonus from Uncle Claude, and a Saturday matinee ticket to Slater’s Kiva cinema. ‘I’m out of the midwest,’ McQueen would say, from the far side of fame. ‘It’s a good place to come from. It gives you a sense of right or wrong and fairness, and I’ve never forgotten [it].’

He made his life within the cycles of manic depression, and they shaped him as much as the cycles of seasons and weather and fat and famine shaped the lives of other Slaterites. For the most part, Steve was happy enough to lose himself in Claude’s farm and the hardware. But clearly there was a part of him, burning down inside, that wanted to get away as far and as fast as possible.

McQueen’s morbid ambition was in large part revenge. Right down the middle of his psyche ran a mercenary core: the will to get even. Someone, he thought, was always trying to screw him; somebody else was having him on. All the world – but never he – was a con. Not exactly a prize sucker for the sell, Steve started off life ‘thinking everyone, from [Julian] down, was after me’, and went on from there to get paranoid. The bitchy litany became the sustained bark punctuated by the snarl and – when backed into a corner – outbreaks of hysterical frothing at the mouth. Even when McQueen got what he wanted, he combined the swagger of the aggressor with the cringe of the abused.

As Steve’s suspiciousness increased, so did his solitude. At a 1900-era diner stranded on Slater’s Front Street, the ex-owner remembers McQueen ‘real well…he came in after school and spent an hour sitting alone there over a glass of water. He wasn’t like other kids.’ Robert Relyea, with whom Steve went into business in the 1960s, recalls him ‘practising the famous baseball drill in The Great Escape for two days…I don’t think he’d ever been much for team sports.’ This key truth, more broadly unsociable than narrowly un-American, was echoed a few years later, when Relyea and his family were playing football with McQueen in a California park. ‘It was touching that he was running around, laughing at a fumble, punching triumphantly with his fist in the air when he made a touchdown, smiling and nodding when one of the kids brought off a catch, having the time of his life…touching, but also sad that he’d never once played the game as a boy.’ Little wonder McQueen hit the heights in offbeat roles in breakout films. In the process, the improbable wisdom of his moodiness would be fully vindicated.

His life was transformed – at least intensified – by the accumulated blows of 1930–44, to the point where the whole ordeal seemed to be a jail sentence. Not only was McQueen an orphan and condemned case, the Midwest itself was a haven of kidnapping and racketeering, stony-jawed icons like Bonnie and Clyde, Machine-Gun Kelly and the Barkers all plying their trade along the Route 44 corridor. The young Steve once saw John Dillinger being led into jail in Crown Point, Indiana. In later years he remembered how the killer had turned to him with his grinning, lopsided face, curling away from his two guards, and winked. Quite often, McQueen said, he couldn’t go to sleep for replaying the scene in his mind.

Against this felonious backdrop, marches and violent pickets in Saline county reflected the feelings of most Americans in the face of the appalling and mysterious Depression. Fist fights, or worse, regularly broke out between labour organisers and the law. ‘Most of my early memories’, McQueen once told a reporter, ‘are bloody.’

One morning in 1937 Steve was walking with Claude up Central Avenue in Slater when he saw several protesters holding banners turning the corner ahead of them. Soon there was shouting from around the bend. Armed police began to run towards the intersection. Steve looked up at Claude, who said quietly, ‘Something’s up.’ They walked on to the general store on Lincoln Street and heard shots fired. When they got nearer the crowd, they saw one of Claude’s own farmhands being dragged along the ground by three policemen. He was kicking. There was blood, Steve noticed, all over his face and shirt. ‘We better not have anything to do with it,’ Claude calmly told his great-nephew. ‘Better stay way out of it.’ The seven-year-old shook his head.

Steve’s clash with formal education, later that same year, came as a mutual shock. Every morning he walked or biked the three miles down to Orearville, a small, segregated elementary school on Front Street. Stone steps led up under a canopy to the modest one-room box he later called the ‘salt mine’. It was certainly Siberian. A coal stove in the vestibule there gave off as much heat as a 60-watt bulb and when it rained, which it did constantly most winters, water seeped through the roof. Like many shy boys, Steve relied on memorising to get by. (The rote student of Mark Twain would become an actor who hated to learn lines.) Parroting Huck Finn, for his peers, was enlivened by the ‘deez, demz and doz’ tones, plus stammer, in which he flayed the text. It was later discovered that he was suffering from a form of dyslexia. The muffled sniggers were yet another small snub, avenged by Steve with a quick, impersonal beating in the dirt bluff behind the schoolyard or, more often, playing truant. A Slater man named Sam Jones knew McQueen in 1937-8. ‘We all heard stories about him, but the truth is he didn’t show up much.’

By his ninth birthday he was firmly in the problem-child tradition, a pale, sandy-haired boy whose steely-blue eyes gave Jones the uncomfortable feeling of ‘being x-rayed’. People called it a striking face, broad-nosed but narrow-chinned, so that the head as a whole was bullet-shaped rather than oval. Another Slaterite recalls ‘that tense, hunted look he always had in a crowd’. Aside from the claustrophobia, McQueen owed his trademark quizzical squint to hearing loss. An undiagnosed mastoid infection in 1937 damaged his left ear for life, bringing him further untold grief in class and completing a caricature performance as small-town misfit. His remaining time there would be brief, violent and instructive.

As soon as he could drive Claude’s truck or fire a rifle, Steve immediately entered into such active conflict with Slater that the local sheriff called at Thomson Lane to issue a caution, and he aroused the school’s indignation by appearing, when he did so at all, reeking of pig dung. But he also deftly took to his relatives’ world. He liked to hunt, for instance, and once, to Claude’s eternal admiration, he took out two birds with a single shot. Steve often stalked deer or quail in the woods north of town, on the banks of the Missouri, at least once with a pureblood setter named Jim, the officially designated ‘coon dog of the century’. (The animal could apparently understand elaborate human commands, and also predicted the winners of horse races and prize fights.) In short, he said, it was a ‘schizo existence’, in which the wilderness, bloodletting and the magic of the primal, male life jarred against the drudgery of school and church. Steve’s great-uncle and grandparents didn’t bring him up to be violent – something beyond even their nightmares – but they showed him the world, and that was enough.

All this changed for the worse in 1939.

A flash of inspiration as can only be produced by a newlywed parent now caused Julian to send for her son from Indiana. Early that autumn, the same month that Britain went to war with Germany, Steve was taken out of school, packed a kit bag and sat, shrouded in his moth-eaten city clothes, cap pancaked down on his head, in the very back seat of the bus east. It was crowded with immigrant farmworkers going home to enlist. Many of them knew as much about the rest of America as they did about the Antarctic and sat staring or muttering over the noise of Steve’s neighbour, a Negro with a mouth-harp, as they crossed the Mississippi at St Louis. The Greyhound wound through Illinois until, late at night, it came around a curve into town. On both sides a sudden, windswept ruin opened out, the bus ploughing down dark alleys and backstreets, hardly better than furrows between the slums with, Steve noticed, ‘only a couple of pissing rats’ as proof of life. Indianapolis.

McQueen himself looked unhappily through the back window taking in the acrid smell of the city. Those 400 miles were worlds exquisitely separated. Where once there’d been Claude’s pigs, now there were pool halls, the Crescent and the Roxy. Racially, too, Indianapolis was segregated, black and white symbolically split by the railway – somewhere, downtown, men wore cheap Irontex suits and drove boatlike cars past hand-painted signs saying EATS. Local unemployment and, not incidentally, racketeering and Klan activity were all at their height and there was a curfew. It was raining. With two mismatched homes and no fewer than four warring role models (five, including his new stepfather), it’s hardly surprising McQueen would return to the theme of self-reliance throughout his career, channelling it into his best work and telling one startled reporter, ‘I’d rather wake up in the middle of nowhere than in any city on earth.’

The bus pulled in to the Meridian Street depot at midnight. Julian was more than an hour late meeting it, and Steve could smell the gin on her breath when she kissed him. He was introduced to her dour, clinically psychotic, it emerged, husband, and the three of them walked down dark streets, frequently challenged by police, to the boarding house. It was on the site of a former stockyard, and the old stink still haunted the place. Even through the shut window, the familiar depressing reek of meat, tallow, pulverised bones, hair and hides wafted up to Steve’s cold room. Towards dawn, he could hear Julian’s voice pleading and begging through the wall, and then the sound of her husband punching her. Finally, with daylight, the boy fell asleep. After all, he later told a close friend, it wasn’t as if it were permanent. They already owed their landlord ten dollars.

Before long Steve’s fourth-grade teacher in Indianapolis wanted nothing to do with him, and the contempt was mutual. Most mornings he went back to his earliest haunts, nowadays alone, slipping into the darkness of the Roxy, then begging some bones at the kitchen door of a diner. It wasn’t unknown for him to scavenge from the dustbins outside the canal bars, and he became an underage, lifelong beer toper. One day Steve fell in with some older boys who showed him how to steal hubcaps and then redeem them for cash at a store downtown. It was his first glimpse beyond his own rebellion into a world of organised crime that he would find more intriguing than the weekly mass to which his grandmother had dragged him in Slater. Julian and her husband tried, too, packing him off to a delinquents’ summer camp and Sunday school. But Steve acquired neither religion nor social graces. Soon, he was spending his nights running with a gang. He rarely, if ever, slept at home.

There was some building done during the late 1930s and early 1940s: hospitals, museums and parks all overlaying the great Lockefield Garden prank, a slum clearance scheme that provided housing for 7000 families. Several of these projects went broke and the Reconstruction Finance Corporation had to bail them out. By the time Steve arrived for the second time, the feds had assumed much of the local relief burden and a bewildering raft of agencies funnelled funds to help towns like Indianapolis to their own grass-roots ‘solutions’. Soon enough, there was money and food available to the needy. The young McQueen doted on the pleasure it would bring to relieve the suits of their cash.

Steve not only legitimately applied for ration tickets. He began working a lucrative forgery scam with his street mob. Between them they printed bundles of the tatty coupons and sold them at a profit to their contact downtown, who was in turn reimbursed by Washington. It was a crude but highly effective form of pioneering welfare fraud. Steve might have been a flop at school, but his inner fire – the vitality that erupted whenever he got away with something – was uncanny for a so-called loser. From about 1940 onwards he was busy either as a petty hood or generally twisting the system – and people’s melons – to his own ends. ‘You had this sense he was getting back on folks,’ says Toni Gahl. ‘He just tried everything, like he was fighting for his life. I heard about his [welfare] thing. Son of a bitch! No one else was doing that then, I couldn’t believe it.’

There was something almost confidence-inspiring in McQueen’s later career. For the few who knew him and millions who didn’t, his was the big magic that offset the cliches of the American film industry. Partly this was a result of his image, partly the result of his personality. Even in the 1940s a gap opened up between the angry thug and the shy boy wearing a pair of overalls hand-labelled Huck who was quiet, kind and fanatically loyal to friends. One was dark, one was sunny, but the two McQueens had this in common: both were warped by a sense of being alone in a ‘shit’ world. That long and hard childhood made him a master at walking a thin tightrope, buffeted by the warring rivalries of Julian, her husband and Slater, with church, school and his criminal interests to consider as well. It was a neat balancing act.

When her man left, as they all did, Julian made it a point of honour not to resort further to food stamps. Prostitution only ever supplemented her typing and waitressing but, after the day Steve caught her in flagrante, it took on a symbolic importance for him far outweighing its fiscal value. She hated doing it, obviously. No she didn’t. She didn’t hate it all that much. She was always fucking at it, he told Gahl. Sailors. Suits. Anyone, any time at all. From then on Steve spent his few evenings at home sitting on the stoop of their small downtown hotel while Julian was at work upstairs. She’d yell at him and throw a shoe at the door if he ever interrupted her, and he even had to fit his sleeping arrangements (by now he and his mother were sharing a bed) around hers. If Julian was entertaining late, Steve would make up a sort of bunk for himself, using his jacket and a few flattened boxes as blankets, on the ugly, geometric-patterned tile floor of the vestibule. One winter when she was unusually busy, he ate all his meals out there, crouching behind stairs or walls, or anywhere that was protected from the snow.

Indianapolis aged him, but arguably he never really grew up. Steve’s family life was dire and, at times, outrageous. On Saturday mornings, after a week in which she’d been with four or five men, Julian would shout downstairs and ask him the time. The ritual gave Steve a rare link back to Slater, since his one valuable possession was a pocket watch he’d been given by Claude. He’d yell up in his high, reedy voice, breaking slightly but also militant, ‘Nine o’clock, Ma.’ This was the signal for one of those sudden reversals in behaviour that constituted the basic pattern of Julian’s life. She’d come down in her high heels and dress, kiss him on the mouth and then hurry off with him to the Roxy. Steve already lived for the cinema. Even in the drenching rain which seeped through the brickwork, he could soak up the lushness and grace of the western landscapes he loved, the grandeur and ruggedness, the seductive combination of sex and violence. By his eleventh birthday, he was hooked.

It was a boom time for the movies. In the early war years Hollywood went from a half-shod outpost dealing in flickers to a culture factory employing the likes of Mann, Brecht and Faulkner. A large number of Broadway’s classical stars were coming west as fast as they could make it. The very best pictures of the day – Gone with the Wind, The Grapes of Wrath, Mrs Miniver – created characters that weren’t just some new aspect of stage acting, but new from the ground up. Bogart’s High Sierra, above all, won Steve over. This far-fetched gangster yarn had its faults, even he would admit, but in the lonely, sardonic yet soulful leading man it boasted a recognisable role model – ‘someone [whose] mud I dug’. More than thirty years later he was still mining the lode of that film, along with trace elements of The Maltese Falcon and Casablanca. ‘I first saw Bogie on screen when I was a kid,’ Steve said in 1972. ‘He nailed me pronto, and I’ve admired him ever since. He was the master and always will be.’

There were better technical actors than McQueen, more classical or orthodox, but none who did a more brilliant take-off of his hero. He was more volatile than the actual Bogart, colder, more threatening, more thoroughly lost in the parts. He reprised and improved the famous sneer; he paid homage to Bogie and outdid him in the same breath. But Steve’s emotional authenticity went far beyond getting off a decent impersonation. His smallest movements had the kinetic flow of an animal, something feral. Whether playing the loner, the loser or the lover, he drew on his own signature mix of ego and insecurity. There was, first up, the man himself. Steve McQueen looked like a movie star. A front page of him, whether tight-lipped and scowling or smirking archly, was usually worth thousands of extra copies. But there was more to his success than bright blue eyes and a fetching grin. McQueen was one of that rare breed of actors who didn’t need to ‘do’ anything in order to shine. It was enough that he had, as Brando puts it, ‘the mo’, the properties of a bullet in flight.

Laser-like focus was key to the young Steve, always adapting to some new competition, some fresh conflict. When not brooding at home or prising off hubcaps, he would make for the downtown pool hall. He played the game like a war, often wagering his entire day’s cash and immersing himself in the ritual, polishing shots and practising slang – picking up the protocol of the sport. Steve’s technique was sound, his gamesmanship honed, the depth of concentration frightening. But what most struck people, says Gahl, was the way ‘he got in part…Even broke, he’d show up with his own monogrammed stick and a bridge that was pure Minnesota Fats.’ McQueen played with self-assured pride, gliding this kit around the baize and carefully stowing it at night in a leather travelling case. He took it with him everywhere and, in 1956, its third or fourth successor became the very first item of the ‘stuff’ (as he called his stage artefacts) he worked so brilliantly on screen. Persistence, panache, props: the three ingredients were already filling out Steve’s street education, and he soon added a fourth. The fear he aroused in people was palpable, and he reinforced it more than once around town with that same pool-cue.

How much of the juvenile delinquent McQueen would be in his films? The answer is that the more you watch him, the more of him you recognise. It was precisely because he was real – working off his own reactions, not the director’s – that he managed to create roles with mass appeal to high- and lowbrow alike. When he played a loner or a hustler, an emotional basket case, you could be sure it was coming from deep source material and not just a script. Those early years fell, Steve said, as ‘ashes and muck’ on adult life but as gold and fame on his career. In a rare cultural allusion, he sometimes compared his Indianapolis gang days to Fellini’s I Vitelloni. ‘That one…seemed to sum up the kind of kids we were at the time – whistling at chicks, breaking into bars, knocking off lock-up shops…a little arson.’ That kind of thing. His early childhood was the ‘baddest shit imaginable’, McQueen later told his wife.

Then things took another turn for the worse.

Late in 1940 Julian, apparently unable to cope, sent him back to the farm in Slater. Steve spent the next two years there. Home again became the tall prairie-grass pastures around Thomson Lane, the hulking grain storage silos and the love-seat under the old elm close to the house where Claude would sit swinging on summer nights with his new maid and future wife (less than half his age), Eva. McQueen’s room was a tiny attic under the eaves. Because of his obvious affection for his great-nephew, his tendency to josh him, and the enjoyment he took from his company as time went on, much would be made of Claude’s influence on Steve. With such a father figure a boy could hardly be an orphan. ‘The main script read like Tom Sawyer,’ one McQueen biographer has written. But there was also a dark sub-plot from Tennessee Williams around the place.

A heavy drinker, Claude had a volcanic temper. His fiancée, an ex-burlesque dancer from St Louis, where she left an illegitimate daughter, wore fake diamond rings on every finger and drove a gold Cadillac. The money soon ran out and the farm resorted to raising fryer chickens to sell at Christmas. Steve’s grandfather Vic was still living across the field in the disused sleeper, suffering from terminal cancer. His wife Lil went from being merely pious to fanatical, sometimes hobbling up Thomson Lane nude except for her crucifix and rosary in order to ‘see God’. Most days she didn’t recognise, or even acknowledge, her grandson. There were constant rows between husband and wife, brother and sister, plates flung, cops called. Julian, meanwhile, never once visited. All in all, it was no place for a chronically depressed twelve-year-old with an already fractured home life. If Indianapolis seemed like Fellini, then Slater was a living embodiment of American Gothic, the starkly realistic painting of Midwestern farm life unveiled, like Steve himself, in 1930. He ran away more than once, loping down to the railroad tracks with his few belongings in a knapsack, accompanied by a black-and-tan dog of uncertain ancestry and his black cat Bogie. The brick depot at the far end of Main Street made a viable overnight shelter from the madness of the farm.

The central fact of Steve’s childhood is that he was destroyed by men and blamed a woman. He carped at his vanished father for the rest of his life, but always with the key qualification, ‘Julian!’ He caught the right note of bewilderment. Claude himself wasn’t merely cranky, he was a tough disciplinarian who used strap and rod on his great-nephew; McQueen once called him ‘a shouter, very vociferous…He’d blow me out of the place, but I deserved it.’ His first stepfather, according to Gahl, ‘sexually molested Steve. He told me the two of them had been together one cold night while Julian was downtown, and how [McQueen] could always remember the beads of ice dripping from the ceiling like the sweat on the old geek’s lips…and that he, Steve, had tried to focus on the sound of the water and the wind flapping the hotel sign around outside the door to avoid thinking about what was going on.’ This was the same man who casually – and quite frequently – beat up his wife. That long winter of ritual abuse, physical and emotional, can only have been a trial to Steve’s mother as well, tied as she was to a perverted bully she couldn’t acknowledge as such. Steve, for his part, would always hold Julian responsible for the misery of his early years. ‘Don’t talk to me about love,’ she used to say. ‘I feel the same way before, when and after I fuck somebody – like shit.’

In mid 1942 Julian, now divorced and remarried to a man called Berri (Steve could never remember his first name), sent for her son to join them in California. Various circumstances had led to the move west, earlier that spring, among them another landlord-related crisis in Indiana. The specific reason that brought her to Los Angeles was that Berri was offered steady manual work on the fringes of the film trade. They took an apartment together on a drab, half-paved road of cheap motels between Elysian Park and the Silver Lake district, a mile or two north of downtown. Though there were sweeping views and a few modernist piles nearby, it was practically a genetic rule of thumb that Julian would end up in a slum. If the change was as good as a rest, its effect was to shatter her already primitive concept of family.

Day one she broke out the peroxide, nestled into a deck chair and whooped, ‘California!’

In fact neither the address nor the building itself could have been much worse. The Berris counted rats, raccoons, snakes, wild dogs and prairie-wolves in three or four varieties amongst their neighbours. Coyotes, the most feared, regularly came prowling down from the Verdugo hills. It was all a long way, figuratively, from Hollywood, let alone either Indianapolis or the farm. Steve arrived in LA, he told Gahl, feeling like he’d ‘crash-landed on Mars’, a pale, sulky refugee who now barely recognised his mother. Her first words when she met him at the depot were to tell him to behave around his stepfather, whose name they now took.

One night in his tiny back bedroom, with the vermin grazing outside, Steve lay down to write a letter to Slater. It wasn’t the usual perfunctory note home of a young teenager and it turned into a long one, as there was real hell as well as news involved. His new stepfather, he told Uncle Claude, was a thug who regularly beat him up. Steve was torn between his desire to run and a strong, but not yet overpowering, urge to fight back. Surely his family would rescue him. Is that what they were? Yes, he decided, those were his loved ones back in Slater. ‘Tonite after supper’, the letter continued, ‘[Berri] came to my room when he was ripped and lit off on stuff that he yells at Ma and me about and which he’s crazy over. That is, me and Ma finding jobs. Says he will likely toss us out if we dont start work.’ Steve went on like this for three pages, all of them covered in his spidery, retarded scrawl, sloppy, verbose and misspelt, though with sudden and surprising jolts of insight. The very last word over the signature, and the keynote of his whole year in LA, read ‘Help’.

The letter never made it to Slater. Berri, now lacerated by ulcers as well as by failure, got up in the night and noticed the light from under Steve’s door. Grabbing the letter, he read the first line or two before tearing it in half. When Steve bent over to pick it up, he was kicked or at least swatted hard on the rear. Berri followed this up by threatening to brain him. Unscrewing the dim bulb overhead, he then left Steve alone in the dark, whimpering in long, shuddering sobs and vowing revenge.

‘Berri used his fists on me,’ McQueen said later. ‘He worked me over pretty good – and my mother didn’t lift a hand. She was weak…I had a lot of contempt for her. Lot of contempt.’ Unsurprisingly, he was soon back running with a gang of toughs and shoplifters who worked the area around the bottom end of Sunset Boulevard. On Christmas Eve Steve was booked for stealing hubcaps from cars parked in Lincoln Heights. Truancy officers from the Los Angeles school board also called. At this dire pass, Julian wrote Uncle Claude a letter of her own, telling him how bad the boy was, and that they were considering sending him to the reformatory. A month later Claude wired money for the bus fare back to Missouri.

It had changed in Steve’s absence. Now the trains hauled troops as well as cattle, and a local factory converted from shoe manufacturing blasted out parts for the B-29 bomber. On the farm, too, began a painful induction into the world of peers and rivals. Claude’s wife Eva had sent for her own child, Jackie, from St Louis. The teenage girl was a year older than Steve and, it seemed to him, was spared chores around the house as compensation for having been dumped. Though he began innocently dating another relative of Eva’s, Ginny Bowden, Jackie’s would duly be the ‘first cooze I ever saw’, ogled through the crack in her bedroom door. There was also a suspicion that the seventy-year-old Claude was more interested than was proper in his stepdaughter. It was now, too, that Steve’s widowed grandmother was hauled off to State Hospital One, as the local asylum was called. The last sight he ever had of her was of her being dragged, kicking and screaming, out of her room. They used a straitjacket on her; an experimental model, it dislocated one of Lil’s painfully thin shoulders. Steve stood in open-mouthed horror as the old woman whirled free, yelling in agony and biblical righteousness, before being muzzled and hauled off like a mad dog. Once in the ambulance, she became a muffled shade and disappeared.

Steve, for his part, enjoyed his freedom to go drinking, hunting, or cruising off on his red bike with the black-and-tan or his pet mouse. For an inquisitive boy, he did remarkably little reading; the business of showing up for eighth grade was so tedious and time-consuming that he never made more than a few stabs at it. He was a dab hand at story-telling, but that was his one and only accomplishment back at Orearville. Formal learning never mattered much to Steve, aka Buddy Berri. At the end of the summer term, after calmly informing his schoolmistress of his dream of becoming a movie idol, he ran down the seven steps onto Front Street, laid out his cap on the ground in front of him and began doing Bogart and Cagney impersonations. When the afternoon was over he’d collected a total of two dollars. Thrilled at his success, Steve rode his bike home to Thomson Lane, where he repeated his career plans to Claude and Eva. His great-uncle’s response was to let rip with a contemptuous belch from behind a gin bottle.

One evening Claude tore a strip off him after the law called yet again at the Thomson farm, this time in response to complaints that Steve had shot out a cafe window with his BB gun. After the shouting had died down, the fourteen-year-old took off into the night. By way of a travelling circus he grubbed his way back west, eventually reaching California. Steve never set foot in Slater again. For the rest of his short but active life he carefully avoided it. McQueen had mixed views about the place. On one level he clearly loathed it, running it down as a ‘sewer’ where he’d felt his welcome to be, at best, sketchy. On the other hand it was precisely in his retreat into the world of guns, engines and play-acting that he found his way in life. Keenly aware of his role as Hollywood’s misfit, he played the part with a flair that gave his performance that touch of genius. He made a whole career out of his rich source memory.