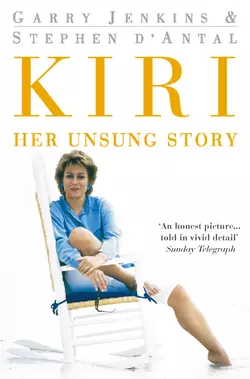

Kiri: Her Unsung Story

Garry Jenkins

Stephen d’Antal

This edition does not include photographs.The biography of Kiri Te Kanawa, one of the most well-known and well-loved personalities in music, revealing for the first time the dramatic story of her origins, career and marital life.Dame Kiri Te Kanawa exudes an exoticism, glamour and appeal unmatched by any other diva of her generation. She is the most widely recorded and most instantly recognisable female face in the world of classical music. Yet there are few among her followers who really know the amazing story behind the public figure.Kiri has brought opera’s most passionate and powerful roles to memorable life. More than any other woman she has been responsible for broadening the appeal of opera and serious music. Kiri: Her Unsung Story charts her remarkable rise from unwanted baby and raw prodigy to polished performer; from national celebrity when, at just twenty-two, she left her homeland, to international icon. Sydney, La Scala, Covent Garden, the New York Met and her scene-stealing performance at the Prince and Princess of Wales’s wedding in 1981 – Kiri has risen to the pinnacle of her profession.Born Claire Mary Teresa Rawstron fifty-five years ago, the illegitimate daughter of an Irish immigrant and a Maori, Kiri was adopted when she was six months old. For many years she never knew where she came from or who her real parents were. The moving and unforgettable story that is her real life is told for the first time. The highs, and the lows – her volatile private life, the backstage fighting, her two miscarriages and her failure to have children, and the eventual break-up of her marriage to Australian mining engineer Desmond Park – are revealed together with the full details of her past.

COPYRIGHT (#ulink_0a20f9ae-9723-538c-b803-1df944a613b0)

Harper Non-Fiction

A division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 1998

Copyright © Garry Jenkins and Stephen d’Antal 1998

Garry Jenkins and Stephen d’Antal assert the moral right to be identified as the authors of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN 9780006530619

Ebook Edition © SEPTEMBER 2016 ISBN: 9780008219345

Version: 2016-09-08

DEDICATION (#ulink_e9f8cb75-bcd4-5e6f-8aac-a660eba97ad4)

For Eva and Gabriella

CONTENTS

COVER (#u001600ee-6248-5303-8b1b-0390718c9561)

TITLE PAGE (#u3b91ce5e-8511-51c4-8146-447ba0512eca)

COPYRIGHT (#ulink_e7fb75c0-b0c8-5f5d-a197-32bf5bd4035e)

DEDICATION (#ulink_e3428435-29f8-5650-a56a-b2eaa9b0a554)

PROLOGUE (#ulink_bef5e9d0-1e4a-5304-9272-172224bd3bc7)

PART ONE (#ulink_1422d7cd-9b23-5648-96be-a1c35c14acaa)

The Road to Gisborne (#ulink_ed803634-5a9d-515f-a059-0334a8ca11ae)

‘The Boss’ (#ulink_84f7ebd0-bb82-5431-8caf-72fb9f3a43d7)

‘The Nun’s Chorus’ (#ulink_bec71ad1-e01f-549c-b4d4-a73ead6ecb16)

Wicked Little Witch (#ulink_b2feb4af-c36d-5b02-9fb3-475d871b4aec)

A Princess in a Castle (#ulink_9db98236-17ed-5765-a3db-7fba5d493677)

Now is the Hour (#ulink_dbf5ed4f-febc-5dbd-8c60-e499f50200d5)

PART TWO (#litres_trial_promo)

Apprentice Diva (#litres_trial_promo)

Mr Ideal (#litres_trial_promo)

Tamed (#litres_trial_promo)

A Pearl of Great Price (#litres_trial_promo)

New Worlds (#litres_trial_promo)

Fallen Angel (#litres_trial_promo)

Lost Souls (#litres_trial_promo)

PART THREE (#litres_trial_promo)

‘250,000 Covent Gardens’ (#litres_trial_promo)

A No-win Situation (#litres_trial_promo)

Home Truths (#litres_trial_promo)

A Gift to the Nation (#litres_trial_promo)

Pop Goes the Diva (#litres_trial_promo)

Paradise Lost (#litres_trial_promo)

Out of Reach (#litres_trial_promo)

Freefall (#litres_trial_promo)

Footnote (#litres_trial_promo)

NOTES AND SOURCES (#litres_trial_promo)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (#litres_trial_promo)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR (#litres_trial_promo)

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER (#litres_trial_promo)

PROLOGUE (#ulink_b561553f-857b-5a7f-ac83-0d86324abba6)

Shortly before noon on Wednesday, 29 July 1981, the anxiety that had been etched on the features of Charles, Prince of Wales for most of an eventful morning finally gave way to a faraway smile.

The heir to the throne of the United Kingdom was in the midst of the most solemn moment of his thirty-two-year-old life. Dressed in the full uniform of a Commander of Her Majesty’s Royal Navy he was positioned behind a large desk in the Dean’s Aisle in London’s St Paul’s Cathedral. He had, in the presence of his mother, Queen Elizabeth II, just signed the wedding certificate confirming the vows he had taken moments earlier in the main hall of Sir Christopher Wren’s imperious basilica. Sitting next to him, cocooned in a sea of ivory silk, was his new wife, the twenty-year-old Lady Diana Spencer, now the Princess of Wales.

For both Charles and Diana, the intimacy and privacy of the moment had helped lift the tensions of the previous few hours. The atmosphere inside the chapel, where they were congratulated by their families and the man who had just officiated over the wedding, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr Robert Runcie, was one of joyous relief.

For all the happiness Charles was sharing with his radiant bride at that moment, however, it was another woman who was responsible for his most spontaneous smile. Some fifty metres away, back in the north transept and out of his view, her familiar voice had begun delivering the opening stanzas of one of his favourite arias, ‘Let the Bright Seraphim’ from Handel’s Samson. Suddenly, Charles admitted later, he found himself strangely disconnected from the tumultuous events unfolding around him. Instead, he said, his head was filled with nothing but the blissful sound of ‘this marvellous, disembodied voice’.

If the divine soprano of Kiri Te Kanawa was instantly recognisable to the man at the centre of the most eagerly awaited Royal Wedding in living memory, it was less so to the vast majority of the 700 million or so people watching the spectacle on television around the world. At first the unannounced sight of her striking, statuesque form, dressed in a rainbow-hued outfit, a tiny, pillbox hat fixed loosely on her lustrous, russet red hair, had been something of a puzzle. Yet the moment her gorgeous operatic phrases began climbing towards the domed ceiling of St Paul’s her right to a place in the proceedings was unmistakable.

Charles had wanted the occasion to be a festival as well as a fairytale wedding, in his own words, ‘as much a musical event as an emotional one’. His bride had entered St Paul’s to a rousing version of Purcell’s Trumpet Voluntary. Sir David Willcocks, Director of the Royal College of Music, had conducted an inspired version of the National Anthem. A glorious version of Elgar’s Pomp and Circumstance March no. 4 had been prepared to lead the newlyweds down the aisle. Yet it was the occasion’s lone soloist who was providing its unquestioned highlight.

Since she emerged, a decade earlier, as a musical star of the greatest magnitude with her performance as the Countess in Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro at Covent Garden’s Royal Opera House, Kiri Te Kanawa had grown accustomed to glamorous occasions on the world’s great stages, from the New York Met to La Scala. The faces she saw assembled before her today, however, made up the most glittering audience she or indeed any other singer had ever encountered. Seated on row after row of gilted, Queen Anne chairs were not just the vast majority of the British Royal Family but Presidents Reagan of America and Mitterrand of France, Prince Rainier and Princess Grace of Monaco, the monarchs of Belgium, the Netherlands and Denmark, ex-King Constantine of Greece and the giant figure of the King of Tonga. Behind them sat crowned heads, presidents and prime ministers representing almost every nation on earth.

The soprano’s emotions were, as usual, a mixture of fire and ice. Inside, she confessed later, she was a maelstrom of nerves. Yet her voice, unfaltering and flawless, betrayed none of her true feelings. It was as if she had been born for this moment and this place – as, indeed, many were sure she had been.

In the decade or so since her early stage triumphs, Kiri Te Kanawa had frequently been described as a member of aristocracy. Her father, people said, was descended from a great chief of the Maniapoto tribe, a member of the Maori nation of New Zealand. In truth, she did not know her true identity. She had no real idea whether she was a Maori princess or not. Among the hundreds of millions of people who watched her sing that day, only a tiny handful knew the truth. They sat 13,000 miles away, on the east coast of her homeland, their television sets tuned to the wedding being broadcast live at midnight Pacific time.

As the strains of Handel faded inside St Paul’s Cathedral and the television commentators paid tribute to the singer who had so charmed the assembled kings and queens, they shook their heads quietly and a little mournfully. They knew Kiri Te Kanawa’s true story was rather different from that which the world imagined. They knew, much like the wedding of Charles and Diana, it too was far from a fairytale.

PART ONE (#ulink_9570fa75-9129-5ddd-a457-c20a28fba351)

When people ask you

To recite your pedigree

You must say,

‘I am forgetful, a child,

But this is well-known,

Tainui, Te Arawa, Matatua,

Kura-haupo and Toko-maru,

Were the ancestral canoes

That crossed the great sea

Which lies here.’

Nga Moteatea, Peou’s Lament

The Road to Gisborne (#ulink_d700223d-0b8e-521d-9e33-ff6ce587a48d)

In the early months of 1944 in the remote New Zealand community of Tokomaru Bay, an auburn-haired, twenty-six-year-old woman, Noeleen Rawstron, walked out of the shabby, corrugated iron bungalow that had been her home. She loaded a few belongings into a taxi and began the fifty-mile drive south to the nearest major town, Gisborne, on the eastern Pacific coast.

The two hour journey she was about to make was an uncomfortable one at the best of times. Despite recent improvements, the road to Gisborne remained little more than a rutted dirt track. Given the fact she was heavily pregnant, however, she would have had even more reason to dread every pit and pothole that lay ahead of her.

The child she was expecting was her second. She had left her first son, James Patrick, inside the ramshackle house with her own mother, Thelma, with whose help she had raised him. Like any mother, her anguish at leaving her son ran deep. Yet, in truth she had no choice. Noeleen Rawstron had reached a crisis in her life. The child she was about to give birth to was the result of an affair that had scandalised the tight-knit community in which she had spent her entire life. She had climbed into her taxi that morning to escape.

Noeleen Rawstron had kept her condition a secret from almost all her family, no mean feat given she was one of six children, three boys and three girls, each of whom lived in the small community. Her flight from Tokomaru Bay was almost certainly precipitated by the fact that she had failed to hide the truth from the most powerful figure in that family, her mother.

Noeleen had inherited much from Thelma Rawstron. She too was copper-haired and steely-willed, fiercely independent and at times too fiery for her own good. Now she would need to emulate another of her mother’s characteristics – an instinct for survival.

Thelma’s parents, Samuel and Gertrude Wittison, had fled Ireland at the turn of the century. After a spell farming land near Hobart in Australia, where Liza Thelma had been born in 1887, the Wittisons had sailed on to Napier in New Zealand. It was here, on 12 July 1909, that Thelma married Albert James Rawstron, the twenty-nine-year-old son of a police inspector who had emigrated to New Zealand from Bamber Bridge, Lancashire.

With his new bride, Albert, a carpenter, had soon moved to begin a new life along the coast in Tokomaru Bay. Thelma recalled to her children how she watched her possessions lowered on to the harbour in a wicker basket. To the eyes of later generations, Tokomaru Bay’s setting, on one of the most brutally beautiful stretches of coastline on New Zealand’s North Island, would conjure up images from New Zealand film director Jane Campion’s Oscar-winning movie The Piano. However, to Thelma there was little or no romance to this bleak, windswept outpost. The town amounted to little more than a threadbare collection of homes and farms. In the 1930s the town had little street lighting or indeed electricity of any kind. Fifty miles of often impenetrable dirt track separated it from the nearest large community, Gisborne.

In summer, the so-called East Cape was the hottest, driest region of New Zealand. Yet in winter the cold, Pacific winds would cut into the town with a vengeance. Thelma soon discovered life itself could be no less callous.

At first her marriage was happy enough. Albert, like many of the town’s population, had found work at the giant, meat freezing works that served the district’s sheep-farming industry. Thelma had six children in rapid succession and the demands of his rapidly expanding household became an increasingly difficult burden for Albert to bear. Work at the freezing factory was seasonal. At times money was so tight, all eight of the family were forced to live in a tent near the meat works. Eventually, as the pressures of providing piled up, Albert told Thelma he had decided to leave the coast in search of better paid work in Auckland. He was never seen in Tokomaru Bay again.

Even by the standards of Tokomaru Bay, Thelma’s life and that of her family became a grim and impoverished one. The community was spread out along the edge of the Pacific; the white, European immigrants concentrated in the more affluent part of the town, known as Toko, the indigenous, dark-skinned Maori in a shanty town called Waima. The Rawstrons were among the few white families forced to live in what most regarded as the wrong side of Tokomaru Bay.

In the aftermath of Albert’s desertion, Thelma had kept a roof over the family’s head by working as a cleaner. She would leave Waima each morning at five and walk five miles to a farmhouse owned by two elderly spinsters. She used the money she scraped together to move the family into a rented, corrugated iron bungalow. The home was pitiful – its floors were earth – but in comparison to the tent it seemed positively palatial to her children.

Of all her offspring, Noeleen seems to have been the one who inherited her mother’s combination of inner strength and outgoing attractiveness. She had been born Mary Noeleen Rawstron on 15 October 1918, in Gisborne. A spirited girl, she was also blessed with striking good looks. By the time she had reached her teenage years, she had become an object of admiration for many of the area’s menfolk.

Noeleen’s first serious boyfriend was Jimmy Collier, a handsome Maori farm labourer who lived in Tokomaru Bay. The pair conducted their courtship far from the prying eyes of the local community, in the shadow of Mount Hikurangi and the parched hills overlooking the town. Their idyll was short-lived, however. Soon Noeleen had fallen pregnant. She gave birth to a son in 1938, naming him James Patrick after his father. If she had hoped the child would cement their relationship, she had been mistaken. Jimmy seemed frightened by the responsibility and the speed at which matters had progressed. Noeleen was left to raise Jimmy junior, or Ninna as he was nicknamed, at home with her mother. As Jimmy junior grew into a young boy, his father became less and less an influence in his life. By 1940 Collier had moved to Gisborne where he married another woman. Noeleen found the desertion hard to bear.

‘Noeleen couldn’t understand what Jimmy was doing with her,’ recalled a friend, Ira Haig, a schoolteacher in the town. ‘She knew she was much better looking than this girl and couldn’t accept his rejection.’

In the aftermath of Collier’s disappearance, Noeleen cast her eye around the male population for a man capable of bringing her new happiness. Three years after Collier left Tokomaru Bay, she thought she had found him.

As World War II brought Europe’s economy to a standstill, Tokomaru Bay found itself entering one of the most prosperous periods in its history. With the rest of the world in desperate need of wool and mutton, the freezing factory was at full capacity. More than 2,000 men poured into the area to work, among them a twenty-five-year-old Maori butcher, Tieki ‘Jack’ Wawatai.

Jack had travelled down to Tokomaru from the village of Rangitukia, sixty miles to the north along the Pacific coast. As a Maori he could not be conscripted into the ANZAC forces now being dispatched by the New Zealand government. Instead, with little work available on the farms in his area, he headed south to the freezing factory where his skills with a knife had brought him work in previous seasons. Not for the first time in his life, Jack Wawatai arrived in Tokomaru in need of money. Back in Rangitukia a wife and a large family were depending on him.

Jack had been born and raised in Rangitukia. His father had died there when he was just thirteen. When his mother remarried he had been taken in by the community’s Anglican minister, the Reverend Poihipi Kohere. Jack worked on the minister’s farm where he made an instant impression on his employer’s daughter, Apo. In November 1937, twenty-year-old Jack and eighteen-year-old Apo were married in the Reverend Kohere’s home. By 1943 they had four children.

Jack was a good-looking man with piercing eyes and an engaging, happy-go-lucky personality. ‘He could charm the birds from the trees,’ said his schoolteacher wife. Blessed with a fine singing voice, his renditions of traditional Maori songs and Mario Lanza arias would often drift towards the farmhouse. ‘I would hear him singing to the cows in the field in the middle of the night,’ smiled Apo. In Tokomaru Bay, Jack whiled away the long evenings singing with a group of other, mostly Maori, men in a shop near the Rawstrons’ home.

He had been introduced to the impromptu singalongs by Ira Haig, a friend of his family for years. ‘At first he told me he couldn’t go. He was married and these meetings were for single men only,’ said Ira. ‘But he loved to sing, he really did, and in the end he went. I took him there.’ By 1943 Noeleen had landed herself a job working as a waitress in the meat works’ canteen. It was there she first set her eye on the handsome newcomer. He reciprocated her interest and soon they were seeing each other discreetly. According to her sister, Donny, Noeleen may have assumed Jack was unmarried when she met him. If she had suspicions, they would have been deepened by his regular disappearance at weekends to return to Rangitukia and his family.

Whatever the truth, Noeleen felt the cut of her mother’s Irish temper when Thelma found out what her daughter was up to. ‘My mother kicked up a hell of a fuss,’ recalled Donny. ‘She didn’t like Jack. One, because he was Maori – she didn’t like the Maoris even though she lived surrounded by them – and two, because he was married.’

Disapproval may have been exactly what Thelma’s most headstrong daughter was looking for, however. ‘I saw them walking around town one Sunday afternoon and once I saw them at the pub. I spoke to Noeleen about it and I told her she should stop seeing Jack,’ said Donny. ‘But she told me it was none of my business. She had a strong will.’

Jack’s wife Apo had suspected nothing of her husband’s infidelity, even when he returned with little of his wages left. She put his shortage of money down to his weakness for drinking and gambling on a game called ‘two up’. ‘Jack was terrible with money,’ she lamented. Soon, however, news of his relationship with another woman found its way back to the farm via relations in Tokomaru Bay. While her father, an introverted man, bottled up his fury, Apo packed her bags and headed south to confront her husband. ‘It was a hell of a shock. I hadn’t expected it,’ she said.

When Noeleen got wind of Jack’s wife’s imminent arrival she prepared for the worst. ‘She thought she was coming to knock her block off,’ said Donny, to whom she confided news of the crisis. ‘Maybe Jack warned her because Noeleen stayed well out of the way all weekend.’

Instead, however, Apo maintained a dignified silence. She moved in with Jack in Waima and let him know she intended staying until their marriage was once more on an even keel. When she eventually saw Noeleen on the street she simply ignored her. ‘I couldn’t help but pass Noeleen by – but I don’t think I ever spoke to her,’ she recalled.

Apo treated her husband’s contrition with the scepticism it deserved. ‘He was a naughty boy. Jack said he was sorry and wouldn’t do it again.’ In years to come Jack would confirm her suspicions by straying once more, this time for good. Yet by the end of the freezing season of 1943 the couple were able to make the journey back to Rangitukia with their marriage intact.

Unable to see or speak to Jack, Noeleen was powerless as the latest man in her life left Tokomaru Bay. Her pain was compounded by the fact that he did so oblivious to the reality she was left to face alone. She was pregnant once more.

During the early months of morning sickness, Noeleen managed to keep the news to herself. ‘We never knew,’ said her sister Donny. ‘She never told me or anyone else.’

If she had a confidante, it was probably a woman from outside Tokomaru Bay and her family circle, Kura Beale, stepdaughter of the area’s richest landowner, A.B. Williams, for whom Noeleen had worked as a cleaner in nearby Te Puia Springs. According to some, Kura Beale had herself fallen pregnant in unfortunate circumstances and had, apparently, given her child away for adoption. As Noeleen’s condition became obvious, however, it seems her mother realised what had happened and was instrumental in Noeleen’s decision to leave Tokomaru Bay. Noeleen decided to head for Gisborne, a town large enough and far away enough for her to have her baby in relative peace. When she left, her mother had prepared a cover story for her. ‘I remember my mother telling me that Noeleen had gone away to work for a while,’ said Donny.

The unhappiness she must have endured during the final weeks of her pregnancy can only be imagined. Her misery came to an end at the maternity annexe of the Cook Hospital, on 6 March, when she gave birth to a baby girl. She named the child Claire Mary Teresa Rawstron.

With Jack Wawatai once more reunited with his family and unlikely to have been aware of the birth, Noeleen had no choice but to leave the name of the girl’s father blank on the birth certificate. Forced to remain in Gisborne and without an income, however, she could not leave matters as they were for long.

If Jack and Apo Wawatai had hoped the unpleasantness of the previous year had been put behind them, their wishes were shattered when a policeman arrived on the farm one day that autumn. The officer solemnly presented Jack with a summons to appear at the courthouse in Rotorua in the coming days. ‘He had to go to Rotorua for a hearing about maintenance for the baby,’ said his sister, Huka. ‘That was the first we knew of it.’ Shaken and confused, Jack once more turned to his wife in the hope she would be understanding. ‘He said we should take her in as our own,’ recalled Apo. This time, however, his wish was beyond even Apo’s charity. ‘I told him that was out of the question,’ she said softly. ‘Apart from anything, we had enough children already and couldn’t afford it. Things were very hard at the time.’

It is unclear what decision the court in Rotorua came to when it heard the case against Jack Wawatai. Even if Noeleen had been able to prove he was the baby’s father, any maintenance award would have been pitiful given his finances and other responsibilities. The court case only underlined the hopelessness of Noeleen’s predicament. She knew she would eventually be forced to return to Tokomaru Bay and her mother. Yet she also knew that Thelma’s hostility towards her – and the child of an adulterous affair with a Maori man – would be hard to bear.

A few weeks after baby Claire’s birth, Noeleen – perhaps influenced by her friendship with Kura Beale – decided to put her up for adoption and headed back up to Tokomaru Bay where she picked up her life with her mother and her son Jimmy. There she maintained a steadfast silence about the dramas of that year for the rest of her life.

‘The Boss’ (#ulink_d89fd533-7c41-5550-a194-a17d63a4833a)

Within weeks of Noeleen Rawstron’s departure back to Tokomaru Bay, a member of Gisborne’s social services staff took baby Claire to a house at 161 Grey Street, a short walk from the ocean. There the social worker introduced her to a Maori, Atama ‘Tom’ Te Kanawa, and his wife Nell.

The middle-aged couple had been married for four years. While Tom ran a successful trucking company, Nell was in the process of completing the purchase of the Grey Street property which she was already running as a thriving boarding house.

Approaching her forty-seventh birthday, Nell, the mother of two children from a previous marriage, was now too old to bear Tom a child. The couple had decided to adopt instead. According to their own account, passed on to their daughter later, Tom Te Kanawa was particularly keen to adopt a boy and rejected Claire on first meeting her. Unable to find another home for the baby, however, the social worker persisted. When Claire was taken to Grey Street for a second time Tom had been smitten by the dusky-skinned little girl with huge limpid eyes. He and Nell agreed to adopt her as their daughter.

As the legal formalities were completed Tom and Nell were asked to choose the child’s new name. Nell had agreed with Tom’s idea of calling the little girl Kiri, after Tom’s father, a Maori name meaning ‘bell’ or ‘skin of the tree’, depending on the dialect. For her other names they chose Jeanette, one of Nell’s own middle names, and Claire, the only name they had heard the social workers use when referring to the child. For decades to come, the name her birth mother had chosen for her would remain Kiri Jeanette Claire Te Kanawa’s sole link with her troubled past.

As she handed her baby over to the town’s social services, Noeleen Rawstron had accepted that she could have no say in choosing the family who would become Claire’s parents. As she dwelled on her daughter’s fate back in Tokomaru Bay, she would have hoped for a life filled with love and security. On a deeper level, her instincts may have wished for a home and a family background that fitted the little girl’s own complex beginnings. In time Noeleen would come to discover the identity of the couple who had taken her daughter in, but she would never appreciate quite how alike Claire’s real and adopted parents were.

In the course of a colourful and eventful life, the redoubtable Mrs Tom Te Kanawa had found herself addressed by any number of names, not all of them charitable. At birth on 14 October 1897, she had been christened Hellena Janet Leece. Since then she had been addressed at different times, and with varying degrees of happiness, as Mrs Alfred John Green and Mrs Stephen Whitehead. In electoral and postal directories around the North and South Islands of New Zealand, her unusual Christian name had been rearranged as Ellenor, Eleanor and even Heleanor. It was little wonder she insisted new friends simply call her Nell. To her family and the boarders she took in at her guest house there was little cause for confusion, however. To them she was The Boss – and she always would be.

A boisterous, ruddy-cheeked woman with a heart – and a temper – to match her oversized frame, Nell Te Kanawa cast her considerable shadow over every aspect of life at the house that became baby Claire Rawstron’s new home. During the formative years of her new daughter’s life she would be its dominant – and at times overwhelmingly domineering – force. She would not thank her for it until later in life. Yet without The Boss, it is unlikely Kiri Te Kanawa would have left the town of Gisborne, let alone the North Island of New Zealand.

Like Thelma and Noeleen Rawstron, Nell Te Kanawa had endured a life of early hardship. She was born in the gold-mining town of Waihi in the Bay of Plenty. Nell’s mother, Emily Leece, née Sullivan, was the daugter of a miner, Jeremiah Sullivan. She was one of fifteen children Emily bore with her husband, another miner, John Alfred Leece, originally from Rushen on the Isle of Man. Like many men of his generation, John Leece dreamt of making a fortune at Australasia’s largest gold mine. Instead, however, his life seems to have disintegrated there. It is unclear whether Emily Leece was widowed or divorced her husband. What is certain is that when Hellena was a teenager her mother uprooted the family to the town of Nelson, at the northerly tip of the South Island, where she set up a new life without John Leece.

‘Nell’, as everyone called Hellena, was less than lucky in her own relationships with men. It was certainly not for the lack of trying.

She had wasted little time in finding a husband. She had been just eighteen when she married Alfred John Green, a twenty-year-old labourer from Hobart. Nell had been employed as a factory worker in the town and living with her mother, now re-married to a Nelson labourer called William John Staines. Emily and her new husband were the witnesses at the wedding, held at the town’s Catholic Church on Manuka Street on Monday, 1 November 1915.

Within four years, the Greens had two children; Stan, born in 1916, and Nola, born three years later. Around the time of Nola’s arrival in the world the family moved to a farm in the remote community of Waimangaroa, outside Westport on the stormy west coast of the South Island where Nell’s parents had been married. Life on the land seems to have proven too hard and soon the family were living in the tiny village of Denniston, where Alfred had found work as a carpenter. The move was no less of a failure. With Stan and Nola, Nell left her husband and Denniston for Gisborne on the East Cape of the North Island. She and Alfred Green were divorced in October 1933.

The divorce inspired a new energy in Nell’s life. In the years that followed, she often proclaimed that she had arrived in Gisborne with nothing but ‘two suitcases and two kids’. With the determination that would characterise her later years, she began the process of building a more secure life for herself and her family.

With Stan and Nola and a relation of her mother’s, Irene Beatrice Staines, she moved into a large boarding house at 161 Grey Street. It was while lodging here that, according to some, Nell began performing illegal abortions. Her services were much in demand in the busy coastal town where too many young women found themselves compromised by visiting sailors and other transient workers. As discreet as she was efficient, she apparently found much of her custom within members of the Gisborne’s growing Greek and Italian immigrant population.

Nell had soon found herself a new husband too. Around the time her first marriage was dissolved she met Stephen Whitehead, a forty-eight-year-old widower from Gisborne. Nell and Whitehead, a bicycle dealer and mechanic, were married at the registrar’s office in Gisborne on 8 August 1935. The marriage proved childless, short-lived and somewhat scandalous. It was Kiri herself who later suggested Nell’s second marriage had left her in disgrace, both with her family and the Catholic Church. ‘There had even been talk of excommunication,’ she remembered. If the exact details of Nell’s shame are unclear, it is not difficult to imagine the outrage her backstreet operations would have provoked if they had become known within the church.

From baby Claire’s perspective, at least, there were more encouraging threads linking the lives of Nell Te Kanawa and Noeleen Rawstron. Of all the parallels, perhaps none would prove so significant as the fact that both Nell and Noeleen had found themselves involved in mixed-race relationships.

As her second marriage headed towards divorce, Nell had met and fallen in love with a soft-spoken, deeply reserved truck driver also lodging at Grey Street. In Atama ‘Tom’ Te Kanawa, it turned out, she had found the ideal man with whom to reinvent herself.

Tom Te Kanawa’s family originated from the west coast of the North Island, near Kawhia Harbour and the community of Kinohaku. His bloodlines led directly back to a legendary Maori figure, Chief Te Kanawa of one of the Waikato tribes, the Maniapoto. Chief Te Kanawa’s primary claim to a place in New Zealand’s history rests on his exploits in the Maori wars of the 1820s. In 1826, Te Kanawa and another chieftain, Te Wherowhero, had ended the ambitions of the region’s most feared warlord, Pomare-nui, by ambushing his canoe and murdering him. According to Maori folklore, the two chiefs had then cooked and eaten their vanquished rival. As the gruesome ritual had been carried out, strange, yellow granules had been found inside his stomach. Thus, corn is said to have arrived in the Waikato region.

Tom was one of thirteen children born to a farmer, Kiri Te Kanawa, and his wife Taongahuia Moerua. By the time Tom, his parents’ fourth child and third son, arrived in the world in 1902, the Te Kanawa family had moved from Kawhia inland to the lush green hills above the small towns of Otorohanga and Waitomo. Tom spent the formative years of his childhood in a community built around the family meeting place, or marae, Pohatuiri. The community was a remote collection of earth-floored houses made from punga logs – the trunks of a native fern tree – set miles from the nearest roads. His early life there was rooted in a simple, self-sufficient lifestyle that had served the Maori people for centuries.

Tom’s younger brother, Mita, later wrote of the Te Kanawas’ way of life in a privately published history. He remembered Pohatuiri as a ‘very busy community’, and looked back with affection at ‘the closeness, unity and warmth of everyone’ who shared their world. The fertile land around Pohatuiri provided almost everything they needed. The families bought in only sugar, salt, flour, tobacco and alcohol to supplement their home-brewed supplies. Seafood was often provided by family members from Kawhia. In this land of milk and honey, the depression that afflicted the rest of the world in the 1930s passed almost unnoticed.

The highlights of each year were the huis, or feasts, prepared communally. ‘Our family homestead was situated just above where the spring and the orchard trees were. Whenever there as a hui approaching, everyone planned on the preparation for the function,’ Mita wrote. ‘Each family group looked after certain duties, but we all helped each other. Fruit picking was done by all of us – we collected the fruit and our kuia [elder women] would be busy with the making of jams, pickles, sauces, preserves and homebrews.’

Both Tom’s parents were God-fearing individuals. Taongahuia’s family were staunch members of the Christian Ratana movement, named after its founder Bill Ratana, a farmer who had become convinced of his pastoral role after witnessing visions in 1919. Kiri was never slow to chastise younger members of the family overheard using bad language. It was a community steeped in the Maori language, and its tradition of passing its history on orally rather than the written word. According to the family, Kiri was the possessor of a fine singing voice. ‘Kiri and his wife couldn’t speak English at all. They didn’t really have to up there,’ said Kay Rowbottom, Tom’s niece, the daughter of his sister Te Waamoana. ‘They maybe could read a little but not speak it, perhaps just a few basic words.’

At school, however, Tom was introduced to the harsh realities of New Zealand life. Tom and his siblings were taught English as a second language and were banned by statute from any use of their native tongue. ‘In that era they would have been beaten with a leather strap for speaking Maori,’ said Kay Rowbottom.

Tom’s childhood in the hills eventually came to an end when he was sent to a foster mother, Ngapawa Ormsby, in the town of Otorohanga. The arrangement was far from unusual. ‘Kids were fostered out as workers,’ said Kay Rowbottom. ‘They were like slaves. In a lot of cases, the girls worked in the houses and the boys on the land.’ Tom’s unhappiness at the arrangement was soon obvious, however. ‘I don’t think Tom enjoyed his time down there. I remember people talking about it years later.’

Tom went to a local school for both Maori and European (or Pakeha) children but, like all but the offspring of the wealthy, had no option but to leave at the age of twelve. Forced to find his own way in the world, he became increasingly estranged from the Maori family in which he had been raised. The death of his parents and the end of the old lifestyle at Pohatuiri, where the old community was slowly reabsorbed into the bush from which it had grown, only added to the distance between him and his siblings.

While the Te Kanawa family moved to the Moerua family’s marae at Te Korapatu, Tom decided to break away from his roots and move to Gisborne on the east coast. He arrived there in the late 1920s or early 1930s. It was while renting a room at 161 Grey Street that he met the formidable figure of Nell Whitehead.

On the face of it, at least, Tom and Nell made an unlikely couple. At the age of thirty-seven, Tom was five years Nell’s junior. He was as taciturn as she was ebullient. She had been married twice before, he had seemingly formed few, if any, lasting relationships. Yet against all the odds they seem to have conducted a whirlwind romance. They were married in Gisborne on 14 July 1939, only twenty-four days after Nell had been granted a decree absolute dissolving her second marriage.

In many respects Tom and Nell Te Kanawa were older, wiser and, in Gisborne terms at least, more financially secure versions of Jack Wawatai and Noeleen Rawstron. From the very beginning, they devoted their lives to giving their only daughter Kiri everything she could possibly want in life.

Perhaps Tom’s most significant gift was the name he chose for his baby girl. His choice of his father’s name served a dual purpose. In the short term the name short-circuited any arguments within the family over the child’s adoption into the Te Kanawa line. While fostering was a common practice among Maori, full adoption was rarer. Tom’s relations, notably his younger brother Mita, believed the Te Kanawa name was reserved for blood family and adoption diluted that exclusivity. ‘Mita didn’t like adopting kids,’ said Kay Rowbottom. ‘His only daughter Collen was fostered by him and his wife but they never adopted her. She was always known as Collen Keepa, her birth surname, and she’s no relation of the Te Kanawa family.’

Tom, who had been unhappy during his time as a foster child, was not about to condemn his only daughter to such limbo. Deliberately or otherwise, by handing on his father’s Christian name, a gift Maori tradition dictates can only be given once in a generation, he signalled to Mita and the other members of his family that baby Kiri was his own child. ‘They believed she was a blood daughter because Tom had given her his father’s name, Kiri,’ said Kay Rowbottom. In the long term, the distinctive name, and the heritage that went with it, would prove an incalculable asset. Kiri would come to draw on her Maori ancestry, even write a book, influenced by the magical elements of her roots. On a more practical level, she would appreciate too how it lent her a name and an image that would count for much when she left her native New Zealand.

As she herself put it years later: ‘It’s unique to be Maori, to sing opera, have a fantastic name; it’s all rather exotic and interesting. Better than being Mary Smith with mousy hair.’

Kiri arrived at Grey Street around the time that Nell became the house’s new, official owner in September 1944. The colonial style, white, weather-boarded house stood in the heart of the town, on a peninsula near the town’s docks and the estuary of the Turanganui River. Nell had paid £1,400

(#litres_trial_promo) for the property, which had been repossessed from its previous owners by its mortgagees. When Nell had first arrived in Gisborne it had been a busy guest house run by a Miss Yates. By luck or judgement she took over as its new owner as Gisborne, a shipping centre for the frozen meat industry for more than sixty years, passed through one of the busiest periods in its history.

Gisborne, or Turanga-nui-Kiwa as it was then known, had been Captain Cook’s first port of call when he had landed in New Zealand in 1769. So unpromising was the greeting he received from the local Maori, he named the sweeping stretch of coastline it overlooked Poverty Bay. The modern settlement had been founded a hundred years later in 1870 and named after Sir William Gisborne, then Secretary for the British Colonies.

By the final years of World War II, Gisborne’s population had swelled to some 19,000 or so people. New Zealand’s links to its former colonial masters remained strong. When Great Britain declared war on Germany it had joined the effort immediately. ‘Where she goes, we go; where she stands, we stand,’ its Prime Minister, Michael Savage, had pledged. The nation’s navy was placed under Admiralty control and New Zealand’s pilots travelled to England to form the first Commonwealth squadron in the RAF.

A battalion of volunteer Maori troops was dispatched to the front line from where it would return garlanded with honours. While Mita Te Kanawa was among them, his brother Tom stayed behind to help maintain the flow of mutton, wool and food supplies that was among the loyal Kiwis’ greatest contribution to the war effort.

As New Zealand played quartermaster to the warring northern hemisphere, Gisborne’s harbour was filled with cargo ships bound for Britain and other parts of Europe. As it did so, its industrial base mushroomed. As well as freezing factories, the town became a centre for dairy, ham and bacon processing, tallow and woolscouring works, brewing, canning, hosiery and general engineering. Such would be its growth over the following decade that Gisborne would be officially recognised as a city in 1955.

For the young Kiri, the bustling quays were a place of endless fascination. She would make the short walk to the docks and stand for hours watching the ships sailing in and out, flocks of sea birds attached to their masts.

Her home at Grey Street was no less a source of fascination. In the grounds at the back Tom tended a few chickens, there was a disused tennis court and apricots, peaches and strawberries grew freely. At the front a huge, old pohutakawa tree, to be rigged with a swing later, stood outside the porch. The house stood opposite one of the town’s main ‘granaries’, or general stores, Williams and Kettle. The store had donated the Te Kanawas’ two cats, unimaginatively christened William and Kettle.

Given its central position, and the town’s hyperactivity, the Te Kanawa guest house was never short of boarders. Recounting her earliest memories later in life, Kiri realised she could barely remember a time when there were less than twenty people in the house. The one permanent fixture was an elderly boarder, known simply as ‘Uncle Dan’, who inhabited an upper storey bedroom he liked to call his ‘office’.

‘Every available space she could find Nell put someone in it,’ recalled one boarder, Myra Webster, sister of Nell’s son-in-law, Tom Webster. ‘Every little store shed was done up as a room. Upstairs she would have about four people crowded in each room. She wouldn’t turn anyone away,’ she added.

Nell’s head for business extended to a detailed knowledge of each tenant’s financial arrangements. ‘She always knew when their paydays were. She’d stand at the bottom of the stairs when they came home and she’d make sure they were paying up to date. Most of them were young Maori people who came down from the coast to work in Gisborne. She charged the going rate, about one pound ten a week, so she had a pretty good income.’

The healthy living the boarding house provided meant Nell could move away from her earlier sideline. According to one member of the family, Tom insisted that she stop performing abortions when they married. When he discovered she had defied him on one occasion, an enraged Tom grabbed his golf bag and broke each of his hickory-shafted clubs across his knee.

For Kiri as a child, the house – and its sprawling grounds – was a wonderland in which she could run free. Bedrooms climbed all the way to the third floor attic. Downstairs was dominated by a huge, farmhouse-style kitchen and dining room. At the front of the house, a lounge, complete with comfortable sofas and an upright piano, family portraits and Nell’s collection of knick-knacks, offered the only real refuge from the constant comings-and-goings. While the rest of the house was left in a ‘take us as you find us’ fashion, the lounge was kept spick and span for entertaining guests drawn from Nell’s ever widening social circle.

Nell’s social aspirations were clear to see. ‘Nell used to play croquet with a group of ladies at a club in Gisborne,’ remembered Myra Webster. ‘I think they enjoyed afternoon tea more than the croquet, but whenever these ladies came to the house, out would come the best china and all the dainty little trinkets and cakes.’

In his own way, Tom was upwardly mobile too. Unlike many of his family and the vast majority of the Maori population, he was in favour of assimilation into New Zealand’s dominant, white European culture. As he removed himself further from his family he immersed himself in the middle-class enclaves of the town, becoming a popular figure at the Poverty Bay Golf Club. ‘I think he wished he had a paintbrush and could paint himself white,’ one relation used to say.

His success in business only opened the doors wider. On his wedding certificate, Tom listed his profession as ‘winchman’. Since leaving school early he had worked on construction projects all along the east coast, specialising in driving trucks and operating cranes. With the contacts and cash he made from the most lucrative, blasting a road link to Gisborne via the previously impenetrable gorge of Whakatane, he had set up a small contracting company.

Tom, though no more than 5ft 10in, was a muscular and powerful man and prided himself on his physical strength and his capacity for hard work. ‘He had fingers like sausages, and these wonderful hands, worker’s hands,’ Kiri recalled once. ‘He never believed that he couldn’t dig a tree trunk out, lift a boat, lift anything because he was so strong.’

By the end of the 1940s he was able to build his own holiday home, a comfortable cabin, or ‘bach’, on the shores of Lake Taupo, a favourite New Zealand holiday destination in the heart of the North Island. Tom had always been famously industrious. In Kiri he had found a reason to work even harder. Nothing was too much trouble if it was for Kiri, the unquestioned apple of her father’s eye. When she was very young Tom built an elaborate dolls’ house complete with fitted windows, linoleum floors and a dressing table. ‘Kiri stayed in it for about a week, and then the old lady put a tenant in it,’ said Myra Webster.

In time Kiri came to value the Maori qualities bequeathed by both her natural and adoptive fathers. ‘I was given two marvellous gifts. One was white and one was Maori,’ she said later in life. It was not an opinion she voiced often as a young girl, however.

Kiri admitted later that Tom had ‘basically rejected the Maori side’ of his life. ‘My father would not speak Maori and I would not learn Maori because it was just not fashionable to do that,’ she said. ‘I was brought up white.’

Yet as Kiri took her first steps into a wider world, at St Joseph’s Convent School in Gisborne, her unmistakable heritage drew unwanted attention. Mixed race marriages were far from unusual in Gisborne. At St Joseph’s, however, Kiri found herself in more conservative company. She recalled once how her entire class had been invited to a grand birthday party at a well-to-do home in Gisborne. ‘They sent me home because I was the Maori girl.’ At the time, she claimed later, she was too young to notice, but Nell’s anger at the humiliation ensured the incident was burned into her memory. ‘My mother kept reminding me, and I thought, “Why does she keep reminding me?”’

The treatment meted out to Kiri and the two other Maori girls at St Joseph’s on another occasion left even deeper psychological scars. One day, without any warning, the three children were taken from school and forced to have a typhoid vaccination. ‘At that time in New Zealand, Maori children were considered to be dirty,’ Kiri wrote three decades later in Vogue magazine, the memory still painfully vivid. ‘It made me ill. I was on my back in a darkened room for two weeks afterwards. My mother was furious that she hadn’t been consulted and I never forgave the powers that be for doing that to me without bothering to find out that I came from a good clean home.’

At school, Kiri’s sense that she was somehow apart from other children was confirmed on an almost daily basis. Nell never appeared at the school gates to collect her, she recalled. ‘When it rained there would always be a little crowd of mothers outside the school with raincoats and umbrellas,’ she said once. ‘I always half expected her to be there but she never was. I don’t know why. She just didn’t bother, so I walked home in the wet.’

Her sense of her own uniqueness only deepened as she began to learn more about her origins. According to Kiri, Tom and Nell told her the truth about her background when she was a little over three years old. They drew short of revealing the identity of her real mother and father but made no secret of the fact that she was adopted. As a young girl, Kiri’s emotions would have been no different from any other adopted child’s, a tearful confusion of anger, shame, insecurity and isolation. It was only years later that she began to understand the deep and divergent impact it had on her personality. Asked once about the legacy of her adoption, Kiri admitted it had added to her sense of isolation from the world. Kiri could be a naturally solitary child. ‘You grow up with this capacity to cut off,’ she said. ‘It’s a protective device. I become alone, totally alone when something goes wrong.’ At the same time the knowledge that she had been abandoned by her real parents instilled in her a tenacity and a determination she would never have known otherwise. ‘It turned me into a survivor. I felt I was special and had special responsibilities. I’m quite sure if I hadn’t known I was adopted I’d have stayed a nobody and would be in New Zealand breeding children now. But that turned me into a fighter.’

As her childhood progressed, she found a natural opponent in her mother. Kiri was, by her own admission, a classic example of a spoilt only child. It is easy to see how the distrust, antipathy towards competition and often naked jealousy Kiri has displayed throughout her life was born in her early years alone at Grey Street. ‘I was an only child. I didn’t make friends easily. I always wanted everything my way and I wasn’t very happy in a great bunch of children,’ she said once. While Tom doted on Kiri it was left to Nell to administer the discipline she undoubtedly required. If the young Kiri misbehaved she would be forced to sit silently in a chair. If she looked too unhappy she would be sent into the bathroom and told not to come back until she was smiling. Kiri described once how she learned to offer a sickly fixed smile even when her young heart seemed as if it was breaking. The ability to mask her mood would prove useful in later life.

If the crime was considered severe enough, her mother was not beyond dealing out physical punishment. Nell would take a large wooden spoon or a belt to the errant Kiri. Years later Kiri would recall how she had run mischievously through a patch of poppies Nell had planted in the Grey Street garden. ‘As I skipped through I hit the head off each flower.’ Nell’s reaction was instantaneous. The blow she dealt Kiri was ‘so hard it was unbelievable’.

At least once she threatened to run away. Packing a bag in a temper one afternoon she announced her departure to a disinterested Nell, who was entertaining visitors. Like so many other reluctant runaways, she made it no further than the garden gate where she sat sobbing quietly until the evening.

‘Thought you were going to run away?’ her mother asked as she limped back into the house.

‘I was going to but it got too dark,’ Kiri replied, still sulking.

It was Kiri’s greatest good fortune that she grew up in a house dominated by music. Nell liked to claim that her mother Emily was a niece of the great English composer Sir Arthur Sullivan. The story, repeated by Kiri throughout her life, was a blatant piece of fiction. In fact the roots of Nell’s mother Emily Sullivan’s family tree extended back to Lancashire and the town of Radcliffe. It had been there that Emily’s father, Jeremiah, had grown up with his father, a local schoolteacher also called Jeremiah Sullivan. Sir Arthur Sullivan’s only sibling, a brother, Frederic, lived in Fulham, London.

Nell’s talents as a musician seem to have been genuine, nevertheless. Visitors to Grey Street invaribly found its halls and corridors echoing to her fluent piano playing.

As the 1950s dawned, the television age was being born in America and, to a lesser extent, Europe. On the other side of the world, however, New Zealand would have to wait another decade before its first broadcasts, even then only one channel broadcasting three hours a day. In the meantime radio remained king, with racing and rugby forming the three Rs that were the bedrock of New Zealand life. At Grey Street the family would often sit around and listen to concerts and entertainment shows on the local Gisborne station. In the absence of decent music on the airwaves, Nell would provide the entertainment herself, conducting evening singalongs from the stool of her upright piano. ‘She was a very big personality, and a lot of people loved her,’ Kiri said later.

In this environment, Kiri’s raw musical gifts were soon apparent. At the age of two, according to her mother, she had danced to the sound of Uncle Dan’s harmonica. Nell would also sit her on her lap to show her the rudiments of the keyboard. To her mother’s delight, Kiri was soon accompanying her as well as playing solo. It was her tuneful singing voice that impressed Nell most, however. As a five-year-old, Kiri regaled Nell and Tom with her versions of songs like ‘Daisy, Daisy’ and ‘Cara Mia’. ‘By the time she was eight she had a nice little voice,’ her mother said.

At St Joseph’s, Nell encouraged Kiri to study the piano. To her mother’s frustration, however, Kiri was more interested in sport, in particular fishing and swimming, which she had learned at an early age with her father at Hatepe. ‘She used to be a real tomboy,’ Tom proudly proclaimed. She would not be deterred, however. Soon Nell was engineering Kiri a reputation as a new star in Gisborne’s musical firmament. Nell had begun to encourage Kiri to sing solo at Grey Street gatherings. Drawing on connections in town, she had won her a place on a popular local radio show. Kiri was seven when she made her public performing debut on Radio 2XG singing ‘Daisy, Daisy’. She proved such a success she was invited back at regular intervals. Victorian ballads and songs for more mature voices, like ‘When I Grow Too Old To Dream’, seemed to offer no difficulties. To Nell each of her daughter’s successes only served to fuel her belief that she had real talent. Her mother would reward Kiri with clothes and presents she would pick up on shopping expeditions to Auckland. To the young Kiri, however, the increasing attention became a source of resentment and confrontation.

Kiri got her first indication of the future being planned for her in her bedroom one morning as Nell came in and sat on the edge of the bed. ‘My mother had had a dream where she had seen me on the stage at Covent Garden,’ she recalled once. To Kiri it seemed meaningless. ‘I thought, “Oh, that sounds nice”, and thought no more about it.’ In time Kiri would come to share the same dream. ‘You have to believe in dreams. I don’t think I would have gone on if I hadn’t believed.’ In the meantime, however, she found herself becoming an often unwilling vehicle for her mother’s fantasies.

Kiri’s love of music was real enough. She had been fascinated by the new radiogram that had arrived in the house and had played the family’s first discs, ‘If I Knew You Were Coming I’d Have Baked a Cake’ and ‘Sweet Violets’ endlessly. When she broke one of them she had run out of the room screaming in fear of what Nell might do to her. Yet she had no real interest in devoting her young life to music. Her defiance was, in part, down to a laziness she confessed stayed with her for years. ‘I can see Mummy constantly kept the music going. I’d tend not to feel like it because I was a lazy child, but she’d insist that I sang,’ she recalled later.

Its roots lay also in her natural need to test the parameters of her relationship with her parents. Kiri knew that whatever her wishes she would find a supporter in Tom, in whose eyes she could do little wrong. In truth, Nell loved her just as much. She was a far less pliable personality, however. Kiri had yet to discover how far she could push her.

Ultimately, Kiri’s dislike of the ever-strengthening spotlight now being turned on her owed most to a simpler truth. For all her high spirits around those she knew and loved, she was painfully reserved among strangers. In the house on Grey Street there were times when she was literally ‘sick with shyness’, she confessed once. She was intensely sensitive, too. Kiri often cried when she was taken to the cinema, the sight of violence or sometimes even a phrase threatening it could reduce her to floods of tears.

When she came to take stock of her early years later in life, a prisoner of an operatic diary planned years in advance and a fame by then extended from Gisborne to Glyndebourne, Kiri’s memories of her childhood were not dominated by memories of dresses or dolls’ houses, living room recitals or early radio stardom. ‘If I had to name one aspect of my early life in New Zealand it would be the aloneness of life there,’ she explained. ‘I was able to be alone and I still seek that, I suppose.’

Nell seemed determined to knock her reticence out of her. Kiri’s earliest motivation for singing in public was the sheer terror with which she viewed her mother. ‘She frightened me into singing,’ she said once. When she threatened rebellion Nell’s words were as predictable as they were menacing. ‘I’ll speak to you when everyone goes,’ she would promise.

Few who watched the effervescent young prodigy singing would have believed it. ‘I was not an extroverted child. You have to learn to be extroverted,’ she lamented later.

Gradually, however, Nell’s bullying began to transform her. Soon Kiri was demonstrating the first, formative hints of self-confidence. She went on to one of her regular radio shows nursing a bad cold. When she hit a false note she heard a voice laughing. It might have been a moment of crushing importance, yet Kiri took it in her stride. ‘It was my first sobering experience of somebody being jealous,’ she said later.

The cold was a far from rare event. The harsh New Zealand winters brought a succession of colds and flus with them. For all the robustness of life at Gisborne and Hatepe, Kiri’s health was a constant worry to Nell. ‘I was very sickly,’ she once confessed. Her sports-loving father had encouraged her to take up some of his favourite pastimes to improve her health. Archery had been suggested as a good exercise to strengthen her lungs. Under Tom’s watchful eye, she would later learn to play golf, too.

It was around the time of her radio debut that Kiri was diagnosed as having ‘a touch of TB’. With the medical establishment conducting a love affair with the relatively new science of X-rays, Kiri’s young body was repeatedly ‘zapped’, without any real consideration of the long-term consequences.

Asked years later about her mother’s past, Kiri replied that Nell had been deserted by her first husband. ‘Or maybe she left him, I’m not too sure,’ she added hastily. In truth Kiri knew precious little about her mother’s turbulent background. As a seemingly strict Catholic there can be little doubt first that Nell’s shame would have been intense and lasting and secondly that her pain remained confined to the confession box. She certainly never shared its details with her adopted daughter. ‘My mother was rather secretive about that part of her life. It’s something I didn’t delve into,’ is all Kiri has confided in the years since.

Nell’s children from her first marriage provided the most positive link with the past. Stan, on whom Nell doted, had served in the army during World War II but had returned to run a poultry farm with his wife Pat in Gisborne. Nola had married Tom Webster, a local farmer, and lived at Patutahi on the outskirts of town. A one-year-old Kiri had been a flower girl at the Websters’ wedding in Gisborne in 1945. Nola had been unable to have children and had adopted a daughter, Judy. By 1954, however, Nola’s marital fortunes were mirroring those of her mother. Her marriage to Tom in ruins, she and Judy arrived on the guesthouse doorstep. Mother and daughter would become a permanent fixture at Grey Street.

Kiri quickly discovered she had much more in common with her five-year-old niece than she did with her grown-up half-sister. In the years that followed, Judy became the closest thing to a sister Kiri would know. Like Kiri, Judy knew she was adopted. Nola had told her she had found her in a shop window in Gisborne.

‘Every time we went into Gisborne to the shops I would have her going all round the streets looking for this bloody shop so that she could get all my brothers and sisters that she left behind in the window. I wanted them all with me. And of course she had to play along with it,’ recalled Judy. Inevitably the knowledge bound the two closer.

Judy recalls how at a ‘do’ once, Kiri had joked about the fact that they were sisters. ‘No we’re not,’ Judy had told her.

‘Yes we are, we are all adopted.’

Kiri’s loneliness as an only child seems to have been a source of concern to Tom and Nell. There was frequent talk of Kiri’s ‘brother’ joining the family, according to Judy.

‘Apparently there was meant to be a brother. I always remember it being talked about that Nana wanted to adopt him as well,’ she remembered. All Judy – and her ‘sister’ – knew of Kiri’s real mother was that she was ‘a blonde lady’ who lived somewhere on the coast of the East Cape.

To Judy, Grey Street seemed more like a hotel than a home. Uncle Dan still lived upstairs and appeared to act as an unpaid nanny for Kiri when Nell and Tom were not around. ‘Come up to my office,’ he used to joke with Kiri when she was alone in the house. Kiri recalled once how ‘Danny’ would fill his pockets with stolen bread rolls from a bakery across the road. ‘I used to have one for breakfast every morning. He used to pull out the middle and I’d eat the middle and he’d eat the outside,’ she said.

‘He used to give Kiri and I handfuls of peppermints,’ Judy recalled. ‘As long as we didn’t tell Nell.’

Judy quickly discovered that her ‘Nana’s’ authority was absolute and her temper truly volcanic. ‘When she lost it, we didn’t ask “How high?”, we asked “Excuse me, when can we come down?”,’ she smiled. Yet, as far as Judy was concerned, beneath her teak-hard exterior beat a generous and genuinely loving heart. ‘She was tough, but she had a soft side,’ she said.

Judy loved nothing more than to hear Nell play the piano. ‘Kiri and I would always be on at her after school to play. She would ask: “Have you finished what you were meant to do for school?” If we said yes, she would play.’ ‘Greensleeves’ was a favourite which Kiri too could play well.

A less musical child, Judy had shown a talent for poetry reading instead. A year or so after Judy’s arrival in Grey Street, Nell persuaded the radio station to showcase the two girls as a double act. Judy’s radio career was short-lived, however. ‘Kiri had to sing and I had to read a poem,’ recalled Judy. ‘Kiri did her piece fine, no problem, but I forgot the words and said “Oh shit”,’ she smiled. ‘Well, of course, it was a live show and it went out clear as a bell to all of Gisborne. I think Kiri started to laugh which didn’t help. That was the start and finish of my broadcasting career all in one night.’

Nell waited until Judy was back at Grey Street before unleashing her anger. ‘I remember getting a scolding for that,’ she said.

For all her ferocity, Nell was vulnerable to bouts of ill health. She had been overweight for years and suffered from related illnesses and general tiredness. She spent much of her time confined to her bedroom where she would listen to the radio, read music magazines and summon Tom and the children to talk to her. ‘She didn’t move around that much,’ Kiri explained once. ‘She liked to lie in bed and hold court.’ Kiri and Judy would lie on her bed with her listening to her read stories from the imported American Post magazine. ‘She was a big lady. She had these big arms we used to push up and use as pillows. I can remember her lying on the bed with me and Kiri either side, tucked up on her arms while she lay there reading the story of the Incredible Journey out of this magazine,’ Judy said. ‘She read the whole thing, from start to finish. We weren’t leaving until we found out what happened to these dogs and the cat.’

In the miniature fiefdom that was Nell’s home, the kitchen was the place where she wielded her ultimate power. ‘She was an absolutely brilliant cook, always cooking scones or something,’ recalled Judy. ‘She filled up jars and tins with all sorts of things, making her own jams and pickles.’ The sublime smells that wafted out on to Grey Street seem to have made it a magnet for friends, neighbours and passers-by. ‘When people bowled in, it was “Have a cup of tea.” If somebody wandered in off the street she would cook for them as well.’

In the kitchen, Kiri and Judy were Nell’s chief underlings. ‘She was like a chef. She made the mess and Kiri and me cleared up,’ recalled Judy. The two girls spent much of their time bickering over who would wash and who would dry. ‘Kiri and me fought constantly over that because if you washed you had to do the benches and the stove as well.’

The most intense arguments were reserved for the nights when Nell served mashed potato. ‘She used to make it in big old aluminium pots. They weren’t soaked of course, so the potato stuck to the sides like concrete.’ As far as the girls were concerned, the highlight of the year would be the family’s annual Christmas trip to the cabin at Hatepe on the shores of Lake Taupo. The cabin allowed Tom to indulge his twin passions – tranquillity and trout fishing. For Kiri, too, Hatepe provided some of the earliest and most magical moments of her early life. She recalled once the excitement of catching her first fish with Tom.

The fact that the house had no electricity only added to its enchantment somehow. ‘There was no power. We would drive up from Gisborne and my grandfather would get out the paraffin lamps from the shed,’ recalls Judy. ‘It was a huge big event down there. Stan and Pat stayed on the poultry farm because they had to work but there was my grandparents, mum, Kiri and all the locals would pile in too.

‘Christmas in those days was like a fairy tale for us and I always remember it as a happy time. Kiri and me used to go into the woods looking for big red toadstools. Sometimes we would sit in the trees very quietly, keeping very still, and wait for the fairies to come,’ she says. Kiri’s love of the open spaces of Lake Taupo had been inherited from her shy, self-contained father.

‘Daddy’ could not have presented a quieter, kinder contrast to the gregarious Nell. When she had the house filled with guests, Tom would blend into the background, a benign, watchful influence. ‘Tom was always there but he was always very quiet,’ recalled Judy. ‘If there was a big pile of people he would be stuck in the corner with his glass of ginger ale.’

Tom’s even temper was the stuff of legend within the family. Judy recalls only seeing him lose his composure once. ‘He was working on a car motor and said “bugger” when he hit his thumb with a spanner,’ she laughed. His love of speed seems to have been his only rebellious outlet. While Nell slept on the drive to Taupo the girls would encourage him to put his foot down on the treacherous, twisting inland roads west of Gisborne. ‘He used to drive like Stirling Moss. He was a brilliant driver, fast but not dangerous,’ recalled Judy. ‘My grandmother would doze off and his foot would go down and away we’d go. When she woke she’d bark: “Slow down, Tom, slow down!” It was hysterical. He’d slow right down and keep looking over at her until she nodded off again and then he’d roar off again. She’d wake up, shout at him, and on it went. Every trip was like that.’

The young Kiri lived for the mornings when Tom would wake her with a gentle kiss at 5 a.m. as he left for work. She would slip out into the dawn and spend the day sitting in the cab of his truck. At Taupo she would sit on the edge of the lake in silence as he fished for trout or simply took in the scene. Sometimes father and daughter would sleep out under the stars, ‘to be there when the fish rose in the morning’.

‘What was wonderful about him was you didn’t have to talk,’ she said later. ‘We used to look at the lake and we’d say nothing. For hours. That was the best part.’

For Kiri, such serenity was in increasingly short supply back at Grey Street. By the time Judy and Nola moved in, the evening get-togethers had taken on the air of a showcase for Nell’s prodigious discovery. If the gathering was confined to the immediate family, Nell would command the stage as usual. If there were visitors present, however, there was only one star. ‘Kiri was the big thing,’ said Judy. ‘Always, whenever anybody came around, I would have to sing,’ Kiri confessed later. ‘I felt at the time like a performing monkey.’

For large parts of her life, Nell had known little more than disappointment and disillusionment. With Tom she had, at last, found security. In Kiri, however, she glimpsed an opportunity for something more. She would not be the first mother to find her life revitalised and ultimately taken over by the vicarious thrill of her child’s success. Few stage mothers would drive their daughters from such unpromising beginnings to such unthinkable heights, however. By Kiri’s twelfth birthday, Nell’s ambition for her daughter had already far outgrown Grey Street and Gisborne.

Lying on her bed upstairs, Nell would listen avidly to the many musical competitions broadcast on the radio at the time. The contests had proliferated all over New Zealand and Australia. In 1956 the Mobil Petroleum Company had added to their credibility and popularity by sponsoring the most prestigious of New Zealand’s domestic contests, the biennial competition from then on known as the Mobil Song Quest.

The competition had produced its share of stars within New Zealand, none greater than the Auckland nun widely regarded as the finest teacher in the country. Sister Mary Leo had been born Kathleen Agnes Niccol, the eldest child of a respectable Auckland shipping clerk and his wife Agnes. In later life, she was mysterious about her exact birthdate in April 1895, as it fell only five months after her devoutly Catholic parents’ wedding. Kathleen Niccol became a schoolteacher and budding singer before, at the age of twenty-eight, she walked into the sanctuary of St Mary’s Convent in Auckland and the Order of the Sisters of Mercy. She never left.

A college had first been established at the convent in 1929. Two decades later, in 1949, Sister Mary Leo persuaded the Order to allow her to establish her own independent, non-denominational music school within the St Mary’s grounds. While she concentrated on voice coaching, four other nuns were enlisted to teach piano, violin, cello and organ. Each year as many as 200 aspiring musicians from all faiths and all corners of New Zealand received their education there. In the aftermath of the war, Sister Mary Leo’s pupils had begun to dominate the lucrative singing competitions. It had been her success with an emotionally frail but extraordinarily gifted singer, Mina Foley, that had transformed her into a national celebrity.

An orphan, Foley had begun singing as an alto in the St Mary’s Choir at the age of thirteen. At sixteen, encouraged by Sister Mary Leo, she had won the prestigious John Court Memorial Aria in Auckland. From there she went on to win almost every domestic singing competition. Her successes turned Foley and her teacher into stars. Crowds of well-wishers and pressmen followed them to their triumphs. When, in 1950, they travelled to Australia for the most lucrative of all the Antipodean prizes, the Melbourne Sun Aria competition, most of New Zealand tuned in on the radio.

Foley’s freakish range allowed her voice to reach across three and a half octaves. She had already been dubbed the ‘Voice of the Century’ by the New Zealand media. By 1951, thanks largely to a scholarship from the British Council, the singer had been accepted as a pupil of Toti Del Monte in Italy.

When Nell discovered that Foley was due to visit Gisborne before leaving for Europe, she wasted no time in booking two tickets for the concert at the Regent Theatre. If she had hoped the trip would inspire Kiri she was soon rewarded. Kiri still recalled the impact of the moment thirty years later. She remembered how Foley had taken to the stage in a wonderful gown, ‘all in green net, with off-the-shoulder puffed sleeves and sparkling jewellery everywhere. I remember it so vividly. She used to wear her hair pulled back with one ringlet trailing forward over her shoulder. It was the most awful style but at the time I thought it was marvellous.’

Kiri was transfixed by Foley’s voice. ‘She sang and sang and I never for one moment stopped gazing at her. I think it was then that my mother realised I was going to concentrate on music and nothing else.’ In the wake of the Foley concert, Nell’s dreams began to solidify. By the beginning of 1956 she was ready to swing into action.

For all its historic importance, the East Cape was far from the hub of New Zealand life. In the 1950s and sixties it was regarded as one of the least dynamic and most isolated regions of New Zealand. Nell knew that a move north to Auckland was vital if Kiri was to make any progress. Nell began by telephoning St Mary’s in Auckland and asking to be put directly through to its most celebrated teacher. It was to be the first of many memorable confrontations between the irresistible force that was Nell Te Kanawa and the immovable object that was Sister Mary Leo.

‘I have a daughter who sings very well,’ Nell announced, matter of factly. ‘Will you take her on?’

Sotto voce, Sister Mary Leo explained that, as a pupil of a school other than St Mary’s, Kiri was ineligible for her classes until she was eighteen. In other words, no, she could not.

Nell was in no mind to be deterred by such a rejection, however. She began her efforts to persuade Tom that the family, including Kiri, Nola and Judy, should move to Auckland and that Kiri should be installed at St Mary’s. She had clearly missed her true vocation as a saleswoman. Soon Tom had not only agreed to put the Grey Street house up for auction, but to sell his business as well.

Kiri, however, could not share her mother’s enthusiasm for the move. Grey Street had provided a happy home. From Uncle Dan to the students with whom she had forged lasting friendships in the town, its cast of characters represented a loving and rather extraordinary extended family. Now she was being forced to leave them. Her protests were pointless, however. The move to Auckland was made shortly after Kiri celebrated what she later remembered as a sad and solemn twelfth birthday in March, 1956. ‘It was pretty horrendous,’ she came to say. ‘All the books tell you that you should never change a child at that age. I had left my beautiful home, a dear old man who was my nanny, and missed my “family”.’

Given the events that had led her to Grey Street a dozen years earlier, there was an added cruelty to the enforced farewells. It would only be later in life that she came to understand the significance of what had happened to her. ‘I basically lost my family when I lost that house,’ she would say.

‘The Nun’s Chorus’ (#ulink_26a48bba-73b2-5b24-aa67-e99056404fb0)

With the proceeds from the sales of Grey Street and Tom’s truck company, Nell was able to put a sizeable deposit down on a new home in the Auckland suburb of Blockhouse Bay, about nine miles south of the city centre. The nine-year-old house at 22 Mitchell Street stood at the bottom of a steep drive overlooking the picturesque Manukau Harbour. Only a set of nearby electricity pylons marred the splendour of the view.