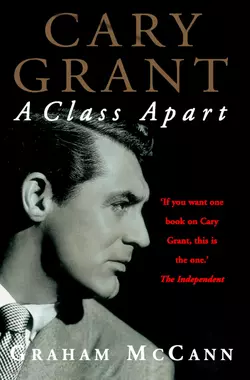

Cary Grant: A Class Apart

Graham McCann

The ultimate biography of this ever-popular star and icon, from a young Cambridge don who has already made his name with a much praised biography of Marilyn Monroe.Please note that this edition is text only and does not include illustrations.Cary Grant made men seem like a good idea. Tall, dark and handsome with a rare gift for light comedy, he played a leading man who liked to be led, a man of the world who was a man of the people. Cary Grant was Hollywood’s quintessential democratic gentleman. Born in England as Archie Leach, made famous in America as Cary Grant, he was a star for more than 30 years, in more than 70 movies, his popularity still intact when he brought his career to a close. He was never replaced: nobody else talked like that, looked like that, behaved like that. He was a class apart. Cary Grant never explained how he came to play ‘Cary Grant’ so well. ‘Nobody is every truthful about his own life,’ he said. ‘There are always ambiguities.’ This book explores the ambiguities in the life and work of Cary Grant: a working class Englishman who portrayed a well-bred American; the playful entertainer who became a powerful businessman; the intimate stranger who was often the seduced male. Thorough and meticulously researched, this book is a dazzling and entertaining account of Cary Grant’s broad and enduring appeal.

CARY GRANT

A Class Apart

Graham McCann

Copyright (#ulink_33ff325e-e9c0-5d3e-874a-332f0045482f)

Fourth Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/)

This edition published in 1997

First published in Great Britain in 1996 by Fourth Estate

Copyright © 1996 by Graham McCann

The right of Graham McCann to be identified as the author of this

work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9781857025743

Ebook Edition © FEBRUARY 2016 ISBN: 9780007378722

Version: 2016-02-08

Dedication (#ulink_49fdfcf0-39fb-5f8a-98bb-0f0fe12bec44)

For Silvanaand in memory of my dear grandparents,Frank and Florence Geary

Contents

Cover (#u074e71ef-c3c8-512f-8a8a-8fa439f91943)

Title Page (#u9c8ddc6e-7e79-5fc5-b372-78e86b9ee8f5)

Copyright (#u77e96e82-9838-54e0-b4f5-7b4ffd0beefe)

Dedication (#u110921c4-858a-5780-bb7f-911642c60146)

Epigraph (#u652ccd16-0768-5ddf-a768-e76330bce9fc)

PROLOGUE (#u7ad1eb01-b4d0-56f9-a58b-d5bd9bae630e)

BEGINNINGS (#uae73f619-52b1-5e2d-993f-d09eed9019cc)

I Archie Leach (#u6b78ef4c-ffc8-59b1-946f-c63378898420)

II A Mysterious Disappearance (#ue42e03a5-cf71-5ca9-ae04-219ef9408649)

III A Place to Be (#ub2c92d61-ffa4-5c27-b750-0c4598d4aaa6)

CULTIVATION (#u4fed9dfb-2cdf-53d7-bd09-5d0e81bace44)

IV New York (#u0bf7c5d5-2f51-5ef2-9b0a-f509ee8c8ff9)

V Inventing Cary Grant (#u9e484667-0608-5643-829d-60d8b9c7fbeb)

Hollywood (#ua3d4c5c7-2ac9-5afd-b797-fe6e0aba12d7)

STARDOM (#litres_trial_promo)

VII Never a Better Time (#litres_trial_promo)

VIII The Intimate Stranger (#litres_trial_promo)

IX Suspicions (#litres_trial_promo)

INDEPENDENCE (#litres_trial_promo)

X The Actor as Producer (#litres_trial_promo)

XI The Pursuit of Happiness (#litres_trial_promo)

XII The Last Romantic Hero (#litres_trial_promo)

RETIREMENT (#litres_trial_promo)

XIII The Real World (#litres_trial_promo)

XIV The Discreet Celebrity (#litres_trial_promo)

XV Old Cary Grant (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Filmography (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

Bibliography (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Notes (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Epigraph (#ulink_ed6aa8e1-c06e-559c-9009-46934c696d24)

Everybody wants to be Cary Grant.

Even I want to be Cary Grant.

CARY GRANT

Carl Reiner and Mel Brooks, ‘The Two Hour Old Baby’

Prologue (#ulink_9aa48f7a-45aa-5f6d-aa36-95c64c7abd07)

A mask tells us more than a face.

OSCAR WILDE

Some might say they don’t believe in heaven

Go and tell it to the man who lives in hell.

NOEL GALLAGHER

Cary Grant was an excellent idea. He did not exist, so someone had to invent him. Someone called Archie Leach invented him. Archie Leach did not know who he was, but he knew what he liked. What he liked was what he came to think of as ‘Cary Grant’. He discovered that it was an extraordinarily popular conception. Everyone really liked the idea of Cary Grant. Archie Leach liked it so much that he devoted the rest of his life to its refinement.

It is easy to see why. Cary Grant was the man that most men dreamed of being, an exceptional man, the ‘man from dream city’.

(#litres_trial_promo) He was that most unexpected but attractive of contradictions: a democratic symbol of gentlemanly grace. No other man seemed so classless and self-assured, as happy with the world of music-hall as with the haut monde, as adept at polite restraint as at acrobatic pratfalls. No other man was equally at ease with the romantic and with the comic. No other man seemed sufficiently secure in himself and his abilities to toy with his own dignity without ever losing it. No other man aged so well and with such fine style. No other man, in short, played the part so well: Cary Grant made men seem like a good idea. As one of the women in his movies said to him: ‘Do you know what’s wrong with you? Nothing!’

(#litres_trial_promo)

There was nothing wrong with Cary Grant. His colleagues admired him. ‘Cary’s the only actor I ever loved in my whole life,’ said Alfred Hitchcock.

(#litres_trial_promo) ‘If there were a question in a test paper that required me to fill in the name of an actor who showed the same grace and perfect timing in his acting that Fred Astaire showed in his dancing,’ said James Mason, ‘I should put Cary Grant.’

(#litres_trial_promo) To Eva Marie Saint, Grant was ‘the most handsome, witty and stylish leading man both on and off the screen.’

(#litres_trial_promo) James Stewart described him as a ‘consummate actor’,

(#litres_trial_promo) and Frank Sinatra remarked that ‘Cary has so much skill he makes it all look so easy’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Stanley Donen, the director, regarded him as ‘absolutely the best in the world at his job’:

(#litres_trial_promo) ‘If you asked almost any man in those days who would he like to be, you’d often get the answer “Cary Grant” – much more often than you would get the answer “the President of the United States”.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

There was nothing wrong with Cary Grant. Movie audiences loved to watch him. In the era when movies were made with and around stars, the initial attraction being the name above the title, no fewer than twenty-eight Cary Grant movies – more than a third of all those he made – played at New York’s Radio City Music Hall (the largest, most important and prestigious movie theatre at that time in the United States) for a total of 113 weeks – a long-standing record.

(#litres_trial_promo) Again and again he was acknowledged as that theatre’s leading box-office attraction. One of his movies was the very first to earn $100,000 in a single week; another was the first to earn $100,000 in a single week at a single theatre. In the pre-eminent popular cultural medium of the twentieth century, Cary Grant was one of its most successful stars. His pulling-power stayed with him until the end of a movie career which lasted for over three decades; even in the year of his retirement, the Motion Picture Association of America voted him the leading box-office attraction.

(#litres_trial_promo) There was no decline, no fall from fashion. He was an exceptionally and enduringly popular star.

(#litres_trial_promo)

There was nothing wrong with Cary Grant. Critics warmed to him. ‘We smile when we see him,’ wrote Pauline Kael, ‘we laugh before he does anything; it makes us happy just to look at him.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Richard Schickel suggested that ‘the only permissible response to him is bedazzlement’.

(#litres_trial_promo) In 1995, Premiere magazine lauded him as, ‘quite simply, the funniest actor the cinema has ever produced’.

(#litres_trial_promo) David Thomson judged him to be nothing less than ‘the best and most important actor in the history of the cinema’, in part because of his singular disposition, his ‘rare willingness to commit himself to the camera without fraud, disguise, or exaggeration, to take part in a fantasy without being deceived by it’,

(#litres_trial_promo) and in part because of the extraordinary richness of the results of this commitment, an art mature and elaborate enough to embrace the ambiguities of a self shown in close-up.

There was nothing wrong with Cary Grant. There was much, however, that was extraordinary about him. That accent: neither West Country nor West Coast, neither English nor American, neither common nor cultured, strangely familiar yet intriguingly exotic (as someone in Some Like It Hot exclaims: ‘Nobody talks like that!’). That expression: capable of blending light and dark inside a single look, hinting at much more than it holds up for show. That walk: confident, athletic and slightly rubber-legged, fit for slapstick as well as for sophistication. He was, in an unshowy way, unusually versatile: he could play submissive, naive, child-like characters (such as in Bringing Up Baby) or worldly-wise charmers (as in Suspicion) or world-weary cynics (as in Notorious). John F. Kennedy thought that Grant would be his ideal screen alter ego, but then so did Lucky Luciano;

(#litres_trial_promo) Grant’s exceptionally broad appeal was in part to do with his bright roundedness, the promise of completion, showing the coarse how to have class and the over-refined how to have the common touch, teaching the unruly how to behave and the repressed how to have fun. What was so remarkable was how Cary Grant himself seemed to be so conspicuously complete. No one else was quite like him. There was something odd, something peculiar even, about his perfection.

‘Everybody wants to be Cary Grant,’ said Cary Grant. ‘Even I want to be Cary Grant.’

(#litres_trial_promo) It was not meant as a boast, but rather as an admission of vulnerability. Cary Grant appreciated – more so than anyone else – how difficult it was to be ‘Cary Grant’, because he knew that he was far from perfect. ‘How can anyone’, asked David Thomson, ‘be “Cary Grant”? But how can anyone, ever after, not consider the attempt?’

(#litres_trial_promo) It is really not so strange that even Cary Grant could not always succeed in being ‘Cary Grant’. It is not as if Archie Leach had always found it easy to be Archie Leach. The difference is that everyone knows who ‘Cary Grant’ is supposed to be, everyone knows the rules, while not even Archie Leach was ever very sure of who Archie Leach was supposed to be.

Everybody knows Cary Grant. What everybody knows about Cary Grant, however, is largely what he wanted us to know. Leslie Caron, one of his last co-stars, recalled: ‘He would say, “Let the public and the press know nothing but your public self. A star is best left mysterious. Just show your work on film and let the publicity people do the rest.”’

(#litres_trial_promo) He lived much of his life on the screen, in the movies, making us believe in Cary Grant, showing his image at each stage in its slow and subtle evolution. When he retired, he withdrew from view. There were no opportunities for disenchantment: no kiss-and-tell memoirs, no television specials, no embarrassing scenes, no political pronouncements, no diet books or diaries, no talk-show appearances, no authorised biographies, no comebacks, no second thoughts. He never told us how he had managed to be Cary Grant so well for so long. He cared too much, or too little, to let on; he liked to keep us guessing. To accept definition was to invite disqualification. He was content, it seemed, just to live with – or behind – the mystery. The mystery had, after all, served him very well. Why let in daylight upon magic?

(#litres_trial_promo) ‘Besides,’ he said, with a playful insouciance, ‘I don’t think anybody else really gives a damn.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Cary Grant was an excellent idea. The last person who wanted to deconstruct that idea was Cary Grant:

Who tells the truth about themselves anyway? A memoir implies selectiveness, writing about just what you want to write about, and nothing else. To write an autobiography, you’ve got to expose other people. I hope to get out of this world as gracefully as possible without embarrassing anyone.

(#litres_trial_promo)

It was typically Cary Grant: polite, urbane, decent and discreet – and very much in control. He looked on with wry amusement as the old tales were retold and the new myths manufactured: he ignored all the parodies and pretenders, all the old quotations and well-worn misconceptions, all the ‘Judy, Judy, Judys’ and the ‘How old Cary Grants’. He did not rise to the bait. He refused to involve himself in the investigations. He kept his self for himself. ‘Go ahead, I give you permission to misquote me,’ he told his uninvited chroniclers. ‘I improve in misquotation.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Cary Grant, in more than one sense, was a class apart. Socially, he was a glorious enigma, eluding every pat classification. Artistically, he was, in his own particular field, without peers. In a leading article in the Washington Post shortly after his death, it was said that the name ‘Cary Grant’, ‘in the absence of anyone remotely like him on the screen, continued to be a synonym for a set of qualities his friends and admirers inevitably summed up as “class”’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Cary Grant did indeed have class. He was a master of the ‘high definition performance’, a term defined by Kenneth Tynan as ‘the hypnotic saving grace of high and low art alike’, characterised by ‘supreme professional polish, hard-edged technical skill, the effortless precision without which no artistic enterprise – however strongly we may sympathise with its aims or ideas – can inscribe itself on our memory’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Everybody wanted to be Cary Grant. Everyone else, before and since, failed. It took someone special to succeed. It took Archie Leach.

BEGINNINGS (#ulink_feb22ac8-ec65-51a7-b82b-6bdd8cebfdad)

It is not dreams of liberated grandchildren which stir men andwomen to revolt, but memories of enslaved ancestors.

WALTER BENJAMIN

Peace. That’s what I’m looking for. I want peace. Withhappy hearts and straight bones without dirt and distress.

Surprises you, don’t it? Peace – that’s what us millions want,without having to snatch it from the smaller dogs. Peace – tobe not a hound and not a hare. But peace – with pride tohave a decent human life, with all the trimmings.

NONE BUT THE LONELY HEART

CHAPTER I Archie Leach (#ulink_b6f58ee0-11b4-57a0-8c41-d958e92685db)

Don’t I sound a bounder!

CARY GRANT

Take it from me: it don’t do to step out of your class.

JIMMY MONKLEY

Cary Grant was a working-class invention. His romantic elegance, as Pauline Kael remarked, was ‘wrapped around the resilient, tough core of a mutt’.

(#litres_trial_promo) It is one of the greatest and most mischievous cultural ironies of the twentieth century that the man who taught the privileged élite how a modern gentleman should look and behave was himself of working-class origin. It took Archie Leach – poor Archie Leach – to show the great and the good how to live with style. It was Archie Leach, born into such inauspicious circumstances, who became the man others liked to be seen with, a role model for the socially ambitious, the well bred and even the royal. ‘When you look at him’, said Kael, ‘you take for granted expensive tailors, international travel, and the best that life has to offer.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Cary Grant exuded urbane good taste and inoffensive prosperity: ‘There were no Cary Grants in the sticks’; Grant represented the most distinguished example of ‘the man of the big city, triumphantly suntanned’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The transformation of Archie Leach into Cary Grant was contemporaneous with, but different from, that of James Gatz into Jay Gatsby. The mysterious and glamorous figure in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby ‘sprang from his Platonic conception of himself’,

(#litres_trial_promo) suddenly, out of sight, without explanation. Cary Grant, on the other hand, took time to take over Archie Leach. Both Leach and Gatz came from poor backgrounds, their parents ‘shiftless and unsuccessful’;

(#litres_trial_promo) both longed to grow, to change, to escape (Leach from Bristol, Gatz from West Egg, Long Island) and reinvent themselves as the kind of attractive, successful, stylish young man of wealth and taste ‘that a seventeen-year-old boy would be likely to invent’;

(#litres_trial_promo) and both possessed an extraordinary ‘gift for hope’,

(#litres_trial_promo) a quality commented on by another character in the novel:

If personality is an unbroken series of successful gestures, then there was something gorgeous about him, some heightened sensitivity to the promises of life, as if he were related to one of those intricate machines that register earthquakes ten thousand miles away.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The two men differed, however, in their relationship with their old identities; Gatsby was a tense denial of Gatz whereas Grant was a warm affirmation of Leach. With Gatsby, all the careful gestures – the pink suits, the silver shirts, the gold ties, the Rolls-Royce swollen with chrome, the pretensions to an Oxford education, the clipped speech, the ‘old sports’, the formal intensity of manner – helped to conceal the unwelcome persistence of the insecure ‘roughneck’, James Gatz. With Grant, however, the accent, the mannerisms, the values, the sense of humour, continued to underline the strangeness of his cultivation. To Gatsby, any memory of Gatz, any recognition of the prosaic facts of his existence, represented a threat to his new identity. To Grant, on the contrary, Archie Leach remained with him, an intrinsic part of his life and character, an affectionate point of reference in his movies and his interviews: Archie Leach was no threat to his – or others’ – sense of himself. Archie Leach was the measure of his success and, in a profound sense, a reason for it.

Cary Grant’s life was lived in the midst of a vibrant American modernity, but Archie Leach’s English childhood was solidly Edwardian. Queen Victoria had died just three years before he was born, and he grew up in a world of gas-lit streets, horse-drawn carriages, trams and four-masted schooners. The culture of the time discouraged – and sometimes mocked – thoughts of upward social mobility. E. M. Forster’s Howards End (1910), for example, depicted the petit bourgeois Leonard Bast as limited fundamentally by his undistinguished background: he was ‘not as courteous as the average rich man, nor as intelligent, nor as healthy, nor as lovable’;

(#litres_trial_promo) he has a ‘cramped little mind’,

(#litres_trial_promo) plays the piano ‘badly and vulgarly’

(#litres_trial_promo) and is married to a woman who is ‘bestially stupid’;

(#litres_trial_promo) his hopeless pursuit of culture is curtailed when he dies of a heart attack after having a bookcase fall on top of him. This was the England of Archie Leach. In this England the story of Cary Grant would have seemed incomprehensible.

Archibald Alexander Leach

(#litres_trial_promo) was born on Sunday, 18 January 1904, at 15 Hughenden Road, Horfield, in Bristol. Elias James Leach, his father, was a tailor’s presser by trade, working at Todd’s Clothing Factory near Portland Square. He was a tall, good-looking man with a ‘fancy’ moustache, soft-voiced but convivial by nature and at his happiest at the centre of light-hearted social occasions. Elsie Maria Kingdon Leach,

(#litres_trial_promo) his mother, was a short, slight woman with olive skin, sharp brown eyes and a slightly cleft chin; she came from a large family of brewery labourers, laundresses and ships’ carpenters. She had married Elias in the local parish church on 30 May 1898. Some of Elsie’s friends felt that Elias was rather irresponsible and, worse still, ‘common’, more obviously resigned than she to their humble position; but it seems that she was, at least for the first few years of their relationship, genuinely in love with him. The family lived at first in a rented two-storey terraced house situated on one of the side streets off the main Gloucester Road leading out of Bristol. Built of stone and heated solely by relatively ineffectual coal fires in small fireplaces, the house was bitterly cold in winter and chillingly damp the rest of the time.

Archie Leach was born in the early hours of one of the coldest mornings of the year. Like most babies at that time, he was delivered at home in his parents’ bedroom. The uncomplicated birth, and the baby’s subsequent good health, were greeted with particular relief by the couple. Their first child, John, had died four years earlier – just two days short of his first birthday – in the violent convulsions of tubercular meningitis.

(#litres_trial_promo) Elsie had sat beside his cot night and day until she was exhausted; the doctor had ordered her to sleep for a few hours, and, as she slept, the baby died.

(#litres_trial_promo) The loss had left Elsie – who was only twenty-two at the time – seriously depressed and withdrawn, and Elias, living in the city that was the centre of the wine trade, had taken to drink. The marriage was put under considerable strain. Eventually, the family doctor advised the couple to try for another child to compensate for their loss. They did so. Archie was to be, in effect, their only child.

It is at this very early stage that one encounters the first of several points of contention in Grant’s biography. Archie Leach was circumcised,

(#litres_trial_promo) which was a fact that later encouraged some biographers to identify him as Jewish.

(#litres_trial_promo) It is not, however, as simple as that. Pauline Kael, among others, has suggested that Elias Leach ‘came, probably, from a Jewish background’,

(#litres_trial_promo) and it has been said by some that Cary Grant himself believed that the reason for the circumcision must have been due to his father being partly Jewish, but, curiously, there is no record of any Jewish ancestors in Elias’s family tree, nor is there any solid evidence to suggest that he thought of himself as Jewish. We do know that Elias and Elsie attended the local Episcopalian Church every Sunday. Circumcision was not, however, it has to be said, a common practice outside the Jewish community in England at that time;

(#litres_trial_promo) it is possible, of course, that the Leaches were advised that it was – in Archie’s case – an action that was necessary or prudent for particular medical reasons (and, after the death of their first child, they would surely have taken any such advice extremely seriously), but, again, there is nothing recorded which could clarify the matter.

It is not even clear whether or not Cary Grant lived his life believing himself to be Jewish. His closest friends – indeed even his wives – have offered conflicting information and opinions on the matter. In the early 1960s, for example, Walter Matthau, who had heard the rumours that Grant was Jewish, was surprised when Grant denied it. ‘So, I asked him why everyone thought he was. He said, “Well, I did a Madison Square Garden event for the State of Israel and I wore a yarmulke.” He pronounced the r in “Yarmulke”. An Englishman wouldn’t pronounce the r, so I still think he might be Jewish. Besides, he was so intelligent. Intelligent people must be Jewish.’

(#litres_trial_promo) There is no reason to think that Grant would have tried deliberately to hide his Jewishness: he was a uniquely powerful and consistently popular star, less easily intimidated than most by anti-Semitic producers and gossip columnists, and he was a frequent contributor to, and supporter of, Jewish charities.

(#litres_trial_promo)

If all (or even most) of the testimonies by his friends are sincere, one has to acknowledge that Grant gave some people the impression that he was Jewish and others that he was not. The extraordinary farrago of conjecture, confusion and wild theorising that this apparent inconsistency has engendered is at times almost comic in its incoherence. An outstandingly bizarre example is the contribution made by Grant’s first wife, Virginia Cherrill, who was convinced (on the rather scant evidence of his deep tan and the fact that he could perform a temsulka, which is a word of Arabic derivation for a special double forward somersault) that he was of Arabic origin.

(#litres_trial_promo) In 1983, Grant – then aged seventy-nine, long retired from acting and surely at a stage in his life when it made no sense to continue to be dishonest or evasive about such a matter – replied to a fan’s question about his late ‘Jewish mother’ by stating that she was not Jewish.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The theory which has been most controversial, however, was put forward shortly after Grant’s death by two of his most assiduous biographers, Charles Higham and Roy Moseley.

(#litres_trial_promo) They claimed, with a suitably bold theatrical flourish, that Grant had been ‘the illegitimate child of a Jewish woman, who either died in childbirth or disappeared’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Although this thesis helps to make sense of the circumcision and of the possible reasons for Grant’s own inconsistent references to his background (Jews define Jewishness through the maternal line), it is not based on any documentary proof. Indeed, the authors strain one’s credulity with their scattershot references to such ‘circumstantial evidence’ as the fact that Grant’s relationship with his mother in later years appeared ‘artificial and strained’

(#litres_trial_promo) to some observers, and that ‘she consistently refused to visit Los Angeles’

(#litres_trial_promo) once Grant was established as a star. They do, however, make use of two further facts which are rather more intriguing: one is that, until 1962, Grant, in his entry in Who’s Who in America, listed his mother’s name as ‘Lillian’, not Elsie, Leach; the other is that in 1948 he donated a considerable sum of money to the new State of Israel in the name, according to the authors, of ‘My Dead Jewish Mother’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

It is quite true that, until 1962, it is ‘Lillian Leach’ who is listed in Who’s Who in America as being Grant’s mother;

(#litres_trial_promo) it is also true – although Higham and Moseley do not refer to it – that the 1941 article on Grant in Current Biography refers to his mother as ‘Lillian’, whereas the 1965 edition reverts, without any explanation, to ‘Elsie’.

(#litres_trial_promo) This discrepancy, while certainly noteworthy, is not, in itself, ‘proof of the existence of Grant’s ‘real’ mother: the entries in both publications contain numerous inaccuracies, such as the spelling of Elsie/Lillian Leach’s maiden name as ‘Kingdom’ rather than ‘Kingdon’ (one would have expected greater care if these entries had been intended to set the record straight), the description of Fairfield Grammar School as the more American-sounding ‘Fairfield Academy’ and the inverted order of Grant’s forenames as ‘Alexander Archibald’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Higham and Moseley do not make it clear why Grant took the seemingly perverse step of ‘disowning’ Elsie while she was still alive and in a fragile condition and then reclaiming her more than two decades later: such inconstancy, surely, merits some kind of explanation. Another puzzling detail, if one is to take seriously the interpretation of these entries as some kind of rare act of candour on Grant’s part, is why, after acknowledging his secret Jewish mother, he then proceeded to describe himself as a ‘member of the Church of England’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

It is a bewilderingly odd little mystery. Higham and Moseley, having convinced themselves that the ‘real’ mother of Archie Leach was a mysterious and hitherto unknown Jewish woman called ‘Lillian’, struggle to weave her into the facts of his life in spite of having no documentary (or even anecdotal) evidence that she, or anyone like her, ever existed. They also fail to explain why Grant, once Elsie Leach had died in 1973, did not make any attempt to acknowledge the identity of his ‘real’ mother at any point during the remaining thirteen years of his life. Other accounts shed no light on the question of Grant’s alleged Jewishness or the reason for the absence of any records which could corroborate it. We are left, in short, with one of those intriguing puzzles which together with others make up a peculiar constellation of ambiguities in the life of Cary Grant.

The first few years in the life of Archie Leach were marked by both material and emotional impoverishment. The Leach family moved house several times during Archie’s childhood, and each change of address marked a further decline in the Leaches’ finances.

(#litres_trial_promo) ‘We could afford only a bare but presentable existence,’ he later recalled.

(#litres_trial_promo) It did not take long for Archie to become conscious of the fact that his mother and father were increasingly unhappy in each other’s company. There were ‘regular sessions of reproach’ as Elsie castigated Elias for his failure to provide the family with a better standard of living, ‘against which my father resignedly learned the futility of trying to defend himself’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Elias started drinking more heavily and frequently – often, it seems, in the company of women who were more convivial than his wife. ‘He had a sad acceptance of the life he had chosen,’ said Grant.

(#litres_trial_promo) Elsie – partly out of necessity, partly by inclination – became the disciplinarian of the family, working hard to keep her young son under control.

Looking back, Grant observed that his old photographs of Elsie Leach failed to do justice to the complexity of her adamantine character, showing her as an attractive woman, ‘frail and feminine’,

(#litres_trial_promo) but obscuring the full extent of her strength and her will to control. When Archie was born, she became – rather understandably given the circumstances – single-minded in her concern for his well-being (she had, superstitiously, waited six weeks before allowing Elias to register the birth) and during his childhood she remained, if anything, a little over-protective of him; she ‘tried to smother me with care’, he said, she ‘was so scared something would happen to me’.

(#litres_trial_promo) She kept him in baby dresses for several years, and then in short trousers and long curls. In an attempt to provide him with an opportunity to have a better and more rewarding life than his father’s, and in the belief that her son was a bright and talented boy, Elsie arranged for Archie to start attending the Bishop Road Junior School in Bishopston; he was only four-and-a-half years old, whereas five was the usual age for admission. She also managed, on an irregular basis, to save enough money to send Archie for piano lessons. Such forceful ambition was not, one should note, so unusual within a working-class family at the time; Charlie Chaplin also recalled how his mother would correct his grammar and generally work hard to make him and his brother ‘feel that we were distinguished’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Archie did not escape from his mother’s influence when he started attending school. Although few of his new schoolfriends came from poorer families than his own, Archie was eye-catchingly smart; Elsie made sure that he wore Eton collars made of stiff celluloid, and she had taught him always to raise his cap and speak politely to any adult he met. His pocketmoney was sixpence a week, but he seldom received all of it; Elsie would fine him twopence for each mark he made on the stiff white linen tablecloth during Sunday lunch. Elias was uncomfortable with the idea of such exacting, sometimes overly fastidious, strictures governing Archie’s upbringing, but he rarely interfered in matters concerning their son.

When Archie was eight years old, his father left the family for a higher-paying job (and, it seems likely, a clandestine love-affair) eighty miles away in Southampton. War had broken out between Italy and Turkey, and, while Britain was not involved directly, armament activities were accelerated. Elias was employed making uniforms for the armies. ‘Odd,’ said Grant, ‘but I don’t remember my father’s departure from Bristol … Perhaps I felt guilty at being secretly pleased. Or was I pleased? Now I had my mother to myself.’

(#litres_trial_promo) The job only lasted six months, in part because of the considerable financial strain on Elias of maintaining two households. He was, however, fortunate that, with so many workers entering into war-related industries at that time, his old presser’s job in Bristol was still vacant on his return.

Elias and Elsie were living together again, but their marriage had disintegrated further. Absence had hardened their hearts; neither person cared enough to communicate with the other. Elias was rarely to be found at home, preferring instead to spend most of his free time in pubs, and, when he returned in the evenings, he would retire immediately after finishing his meal in order to avoid any further confrontations with Elsie. Although Archie was often overlooked during this increasingly tense period, his parents would sometimes, separately, make an effort to entertain him.

Both Elsie and Elias enjoyed visiting the local cinemas, but, typically, they each did their movie viewing in their own distinctive way. Archie’s mother would, on the odd occasion, take him to see a movie at one of the more ‘tasteful’ cinemas in town; he soon became addicted to the experience, and started going on his own or with schoolfriends to the Saturday matinees.

(#litres_trial_promo) ‘The unrestrained wriggling and lung exercise of those [occasions], free from parental supervision, was the high point of my week.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Elias also found time to accompany him but, whereas Elsie usually favoured the rather refined atmosphere of the Claire Street Picture House (where tea and refreshments were served on the balcony during the intermissions and the movies tended to be romance and melodramas), Elias, who ‘respected the value of money’,

(#litres_trial_promo) preferred to take Archie to the bigger, brasher and cheaper Metropole (a barn-like building with hard seats and bare floors, where men were permitted to smoke, fewer women were present and the movies were usually popular thrillers – such as the Pearl White serials

(#litres_trial_promo) – comedies and westerns).

Archie was grateful for all such excursions, but he particularly enjoyed his visits to the Metropole. It was a loud, exciting place, with a piano accompaniment which, he recalled, tended to aim more for plangency than for any discernible tune. It showed the kind of movies and performers he liked most (such as slapstick comedies and stars like Charlie Chaplin, Chester Conklin, Fatty Arbuckle, Ford Sterling, Mack Swain and ‘Bronco Billy’ Anderson), and these occasions were probably the only times when he had the opportunity to establish any real rapport with his father, who sometimes treated him to an apple or a bar of chocolate.

Elias also took his son to the theatre. At Christmas it was pantomimes at such grand places as the Prince’s and Empire theatres. At other times of the year it was music-hall acts, such as magicians, dancers, comedians and acrobats. Elias, ‘in a tight-throated untrained high baritone’,

(#litres_trial_promo) taught his son how to mimic some of the singers of the time (in such songs as ‘I Dreamt I Dwelt in Marble Halls’ and ‘The Man Who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo’), as well as encouraging him to learn some of the magic tricks he had seen. Archie was enchanted. He started to visit the theatre whenever he had the opportunity. He was often alone and unsettled at home, an only child who was ‘loved but seldom ever praised’,

(#litres_trial_promo) but now he had found an attractive distraction. ‘I thought what a marvellous place.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER II A Mysterious Disappearance (#ulink_21d0c2f4-56e1-5369-a343-2ff84c40f39c)

Death merely acts in the same way as absence.

MARCEL PROUST

[I made] the mistake of thinking that each of my wives was my mother,that there would never be a replacement once she left.

CARY GRANT

Archie Leach was just nine years of age when it happened.

(#litres_trial_promo) He had just arrived home, shortly after five o’clock, after an ordinary, quiet, uneventful day at school. He was shocked to discover that his mother had disappeared. She had said nothing to him on the previous day to prepare him for her absence. No one, in fact, had said anything to suggest to him that his mother might not be waiting for him, as usual, at this particular time on this particular afternoon. It was, quite simply, a mystery.

His mother had, it was true, grown stranger, more unpredictable in temperament and behaviour, over the past few months, and he had been aware, to some extent, of the change. She had become increasingly – perhaps even obsessively – fastidious: Archie had noticed that she would sometimes wash her hands again and again, scrubbing them with a hard bristle brush; she would also lock every door in the house, regardless of the time of day, and she had taken to hoarding food; there had even been odd occasions when, inexplicably, she would ask no one in particular, ‘Where are my dancing shoes?’;

(#litres_trial_promo) and on some evenings she would sit motionless in front of the fire, saying nothing, gazing at the coals, the small room draped in darkness. Archie had also grown accustomed – but by no means immune – to the noisy quarrelling between his parents, as well as to the equally common periods of icy silence which usually followed these arguments.

(#litres_trial_promo) Nothing, however, prepared him for such a sudden and dramatic disappearance as this.

Two of his cousins were lodging in part of the house at the time, and, when he realised that his mother had gone, he sought them out to see if they knew of her whereabouts. According to one source, they told Archie that his mother ‘had died suddenly of a heart attack and had had to be buried immediately’.

(#litres_trial_promo) The more common version, however, first put forward by Grant himself, has Archie being told that his mother had gone to the local seaside town of Weston-super-Mare for a short holiday.

(#litres_trial_promo) ‘It seemed rather unusual,’ he recalled much later, with a bizarre attempt at English understatement which perhaps had come to serve, in public, as a relatively painless way of obscuring a painfully disturbing memory, ‘but I accepted it as one of those peculiarly unaccountable things that grown-ups are apt to do.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

If his father attempted to reassure him that his mother would soon come home – and it seems that he did so – then it was not long before Archie realised that she was never going to return:

There was a void in my life, a sadness of spirit that affected each daily activity with which I occupied myself in order to overcome it. But there was no further explanation of Mother’s absence, and I gradually got accustomed to the fact that she was not home each time I came home – nor, it transpired, was she expected to come home.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Towards the end of his life he admitted that, once some of the shock had worn off, ‘I thought my parents had split.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

What had really happened to Elsie Leach was that her husband had committed her to the local lunatic asylum, the Country Home for Mental Defectives in Fishponds, a rustic district at the end of one of Bristol’s main tramlines.

(#litres_trial_promo) Elias had arranged for the hospital’s staff to collect her from their home earlier in the day, and then, after settling her in, he went back to work. He never told his son the truth about the matter.

The asylum at Fishponds was, by quite some way, the worst of the two institutions for the mentally ill in Bristol at that time. Conditions were filthy, and supervision negligible. It cost Elias just one pound per year to keep Elsie inside as a patient. She stayed there for more than twenty years, until, in fact, her husband’s death in the mid-1930s. Was he her gaoler? British law prohibits the unsealing of psychiatric case records until a hundred years after the patient’s death, and, as Elsie lived on until 1973, the actual reasons for her incarceration may remain ambiguous until well into the next century. Dr Francis Page, a Bristol physician, has said that it was ‘always presumed she was a chronic paranoid schizophrenic’, but he also acknowledged that he ‘never did know the official psychiatric diagnosis’ that had been used to keep her institutionalised.

(#litres_trial_promo) She was, it is clear, prone to periods of acute depression, and it is conceivable that she could have suffered a nervous breakdown at this time. It is not so obvious, however, why this in itself should have convinced Elias that the only possible solution would be to abandon her inside the most wretched institution he could find. Ernest Kingdon, a cousin, visited Elsie regularly in Fishponds, and he has insisted that he found her to be resilient and intelligent: ‘She used to write beautiful letters asking why she could not be released.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Although the precise state of Elsie Leach’s mental health remains a matter for speculation, it is much easier to establish the reasons why Elias Leach was prepared – or perhaps determined – to have her committed and out of his life. It was a fact – a fact that Cary Grant never acknowledged or commented on in public – that Elias Leach had a mistress, Mabel Alice Johnson. It might have been the shock of her husband’s indiscretion which precipitated Elsie’s breakdown, although, by that time, their marriage was probably not much more than a sham, and Elsie was unlikely to have been entirely unaware of her husband’s numerous earlier affairs. Divorce was both socially unacceptable and financially impracticable. Once Elsie was shut away, however, Elias was at liberty to establish a common-law marriage with his lover and, eventually, have a child with her.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Archie Leach was kept ignorant of his father’s other family. He and his father moved in with Elias’s elderly mother, Elizabeth, in Picton Street, Montpelier, nearer to the centre of Bristol. Elias and Archie occupied the front downstairs living-room and a back upstairs bedroom, while Archie’s grandmother (whom he later remembered as ‘a cold, cold woman’

(#litres_trial_promo)) kept to herself in a larger upstairs bedroom at the front of the house. This arrangement provided, at least in theory, someone to look after Archie while his father was spending time with his new family, and it saved Elias the expense of renting two separate houses for his double life.

Archie Leach never knew the full extent of the extraordinary deception perpetrated by his father.

(#litres_trial_promo) Cary Grant discovered the truth (or at least a part of it) two decades later, in Hollywood, after the death on 1 December 1935

(#litres_trial_promo) of his father from the effects of alcoholism – or, as the official account put it, ‘extreme toxicity’

(#litres_trial_promo) – when a lawyer wrote to him from England to inform him that his mother was in fact still alive.

(#litres_trial_promo) Through the London solicitors Davies, Kirby & Karath, Grant arranged for the provision of an allowance and moved her to a house in Bristol. Elsie Leach was fifty-seven years old, her son thirty-two. She barely recognised the tall, well-dressed sun-tanned star who arrived back in England to be reunited with her. ‘She seemed perfectly normal,’ Grant would recall, ‘maybe extra shy. But she wasn’t a raving lunatic.’

(#litres_trial_promo) As Ernest Kingdon put it, ‘Cary Grant knew very little of his mother. She was a stranger. Late in life, they had to come together and learn to know each other. It was a tragedy, really – a great tragedy.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Suddenly to re-acquire a mother in one’s early thirties must have been, to say the least, a strange experience, just as the sudden reappearance of an adult son one last saw leaving for school at the age of nine must have been profoundly unsettling. ‘I was known to most people of the world by sight and by name, yet not to my mother,’

(#litres_trial_promo) Grant would say. He, in turn, would never know how ill she had been. Their subsequent relationship, unsurprisingly, might best be described as ‘difficult’.

Opinions differ as to how difficult the relationship actually was. Any references to mothers in his movies – no matter how slight or frivolously comic – have been pounced upon by some writers for their supposedly deeper ‘significance’: in one, for example, his character – a paediatrician – has written a book entitled What’s Wrong With Mothers.

(#litres_trial_promo) According to his biographers Charles Higham and Roy Moseley, there was never any real warmth or affection shared by mother and son; Elsie, it is claimed, was a ‘hard, unyielding woman’ who never showed much gratitude for her famous son’s regular flights to Bristol, nor did she allow him ‘to make her rich’, and she ‘remained stubbornly independent and uninterested in his film career till the end’.

(#litres_trial_promo) She was not, according to some accounts, a physically demonstrative person, and she could sometimes appear aloof and brusque in the presence of strangers.

(#litres_trial_promo) Dyan Cannon, Grant’s fourth wife, after spending some time with her new mother-in-law, described her as an ‘incredible’ woman with a ‘psyche that has the strength of a twenty-mule team’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Grant himself, after her death in 1973, two weeks short of her ninety-sixth birthday, admitted that he had often been exasperated and sometimes hurt by Elsie’s stubborn and misplaced sense of independence:

Even in her later years, she refused to acknowledge that I was supporting her … One time – it was before it became ecologically improper to do so – I took her some fur coats. I remember she said, ‘What do you want from me now?’ and I said, ‘It’s just because I love you,’ and she said something like, ‘Oh, you …’ She wouldn’t accept it.

(#litres_trial_promo)

According to Maureen Donaldson, who lived with Grant for a brief period in the mid-seventies, he said that his mother ‘did not know how to give affection and she did not know how to receive it either’.

(#litres_trial_promo) He is said to have told one interviewer that his mother – in part because of her prolonged absence – had been, until quite late on, ‘a serious negative influence’ on his life.

(#litres_trial_promo) Bea Shaw, a friend of Grant’s, recalls him as being ‘devoted to his mother, but she made him nervous. He said, “When I go to see her, the minute I get to Bristol, I start clearing my throat.”’

(#litres_trial_promo)

It seems, however, that the relationship was not as grim as some have suggested. Speaking in the early 1960s, when his mother was in her eighties, Grant described her as ‘very active, wiry and witty, and extremely good company’.

(#litres_trial_promo) According to some interviewers, Grant remembered visits to his mother when the two would talk and laugh together ‘until tears came into our eyes’.

(#litres_trial_promo) In a letter to the Bristol Evening Post, Leonard V. Blake recalled first seeing Elsie – ‘a rather plainly dressed woman’ – in a department store in the city, telling someone, ‘I have heard from Archie.’ Blake went on to observe that she ‘would visibly glow as his name was mentioned … I believe she would wander around Bristol just waiting to talk about Archie. He was the Sun to her.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Clarice Earl, who was a matron at Chesterfield Nursing Home in Bristol, where Elsie lived during her last few years, describes how when Elsie knew that her son was due to visit she would dress herself up and become excited: ‘She would sit by my office and look along the corridor toward the front door. When she saw him, she’d give a little skip and throw up her arms to greet him.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Years earlier, when the strangeness of her son’s celebrity was far fresher in her mind, she still showed much more interest in him and his career than has usually been suggested. Writing to him at the end of 1938, for example, she confessed: ‘I felt ever so confused after so many years you have grown such a man. I am more than delighted you have done so well. I trust in God you will keep well and strong.’

(#litres_trial_promo) After the end of the Second World War, when Elsie was almost seventy years old, she was interviewed by a Bristol newspaper about her son: ‘It’s been a long time since I have seen him,’ she said, ‘but he writes regularly and I see all his films. But I wish he would settle down and raise a family. That would be a great relief for me.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Elsie Leach, it is true, did not accept her son’s offer – which was put to her on more than one occasion – to move to California, but her refusal was prompted by reasons other than any alleged ill-feelings towards her son. At the end of his life, Grant explained:

She wouldn’t join me in America. She told me: ‘Never lived anywhere but Bristol. Don’t want to [leave], only place I know.’ At her own request she lived in a nursing home but we kept her house although we knew she would never return there. I didn’t want to get rid of it. It would have seemed like I was packing her off.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Elsie was, it seems, as concerned about her son as he was about her. In 1942, when war prevented him from flying over to see her, she wrote to him: ‘Darling, if you don’t come over as soon as the war ends, I shall come over to you … We are so many thousands of miles from each other.’

(#litres_trial_promo) A friend of Elsie’s recalled seeing two large chests of food which had been gifts from Grant. When she was asked why they remained unopened, Elsie is said to have replied, ‘I want to have them until they’re really needed … You never know … Cary might be hard up one day.’

(#litres_trial_promo) When Grant tried, unsuccessfully, to persuade her to let him hire someone to do her housework for her, he was amused and impressed rather than upset by her negative response: ‘she avers that she can do it better herself, dear, that she doesn’t want anyone around telling her what to do or getting in her way, dear, and that the very fact of the occupation keeps her going, you see, dear’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The earliest letter from Elsie in Cary Grant’s papers is dated 30 September 1937, sent from Bristol to Hollywood, and it gives one the impression of a much warmer, caring and humorous person than many biographers have described:

MY DEAR SON,

Just a line enclosing a few snaps taken with my own camera. Do you think they are anything like me Archie? I am still a young old mother. My dear son, I have not fixed up home waiting to see you. No man shall take the place of your father. You quite understand. I am desperately longing waiting anxiously every day to hear from you. Do try and come over soon …

Fondest love, your affectionate MOTHER.

(#litres_trial_promo)

In her letters and postcards – and Grant saved hundreds in his personal archive – she was usually rather garrulous and good-natured, addressing her son as ‘Archie’ or ‘My Darling Son’ and closing with ‘Kisses’, ‘Fondest Love’ or ‘Your Affectionate Mother’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Grant, in turn, cabled or wrote to her regularly,

(#litres_trial_promo) usually addressing her as ‘Darling’, ending with ‘Love Always’ and ‘God Bless’, and signing his name as ‘Archie’. In one letter, sent in 1966 shortly before the birth of his (and Dyan Cannon’s) daughter, Grant wrote:

Watching, and being with, my wife as she bears her pregnancy and goes towards the miraculous experience of giving birth to our first child, I’m moved to tell you how much I appreciate, and now better understand, all you must have endured to have me. All the fears you probably knew and the joy and, although I didn’t ask you to go through all that, I’m so pleased you did; because in so doing, you gave me life. Thank you, dear mother, I may have written similar words before but, recently, because of Dyan, the thoughts became more poignant and clear. I send you love and gratitude.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Phyllis Brooks, who was once engaged to Grant in the late 1930s and who remained a close friend, remembered him being reunited with Elsie: ‘Cary called his mother a dear little woman. But he didn’t talk much about her. I didn’t probe. It was such a traumatic thing to have happen to anybody.’

(#litres_trial_promo) If the reunion had been an act, prompted by fears of adverse publicity, he seems to have invested an unnecessary amount of time, energy and emotion in maintaining the union during the next thirty-five years. It seems likely that Grant and his mother did, slowly, develop a relationship that was, in the circumstances, relatively stable and mature.

It is probably true that he had found it much easier to feel affection for his father.

(#litres_trial_promo) He had, after all, enjoyed an uninterrupted relationship with him, and, after his mother’s disappearance, he may have come to regard his father, like himself, as a victim of that traumatic episode.

(#litres_trial_promo) His mother, it seemed at the time, had, without any explanation, deserted him, whereas his father had stayed and raised him. When Elias died, his son expressed the belief that his death had been ‘the inevitable result of a slow-breaking heart, brought about by an inability to alter the circumstances of his life’.

(#litres_trial_promo) It would be wrong, however, to accept uncritically the common perception today of Elias as the deferential working-class man and Elsie as the somewhat snobbish woman with grand ambitions, just as it would be wrong to believe that Grant sided consistently and completely with one or the other of his parents. He once said that, when he looked back on the family arguments that dominated his childhood, he felt unable to ‘say who was wrong and right’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Both Elsie and Elias Leach possessed a strong sense of working-class pride: in Elsie, this showed itself in her determination to avoid giving anyone an opportunity to regard her family as ‘common’, as well as in her dreams of financial security and her hopes for her son’s social advancement; in Elias, this pride evidenced itself in more prosaic and pragmatic ways, such as in his advice to his son to buy ‘one good superior suit rather than a number of inferior ones’, so that ‘even when it is threadbare people will know at once it was good’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Elsie craved prosperity whilst Elias would have settled for the appearance of prosperity; Archie respected his mother’s boundless determination, as well as sharing some of her aspirations, and he also sympathised with his father’s gentle stoicism.

Eventually, Cary Grant came to look back on his childhood, and both of his parents, with a generous spirit: ‘I learned that my dear parents, products of their parents, could know no better than they knew, and began to remember them only for the most useful, the best, the nicest of their teachings.’

(#litres_trial_promo) According to one of his friends – Henry Gris – it was only relatively late in his life that Grant ‘realised the depth of his guilt complex about his mother’s disappearance. He believed he was the subject of his parents’ many bitter quarrels.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Archie Leach, however, during those traumatic months following the mysterious disappearance of his mother, was unable to come to terms with what had really happened to his family; he could only attempt to adjust to what he thought had happened, and he thought that his mother had deserted him. ‘I thought the moral was – if you depend on love and if you give love you’re stupid, because love will turn around and kick you in the heart.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER III A Place to Be (#ulink_894e9868-0dae-5af0-819d-73cf458a86a2)

Regardless of a professed rationalisation that I became an actor in orderto travel, I probably chose my profession because I was seeking approval,adulation, admiration and affection: each a degree of love. Perhaps nochild ever feels the recipient of enough love to satisfy him or her. Oh,how we secretly yearn for it, yet openly defend against it.

CARY GRANT

Our dreams are our real life.

FEDERICO FELLINI

Archie Leach’s adolescence was marked by absence: the absence of his mother, the absence of a stable home life, the absence of money, the absence, it seemed, of a promising future. Not long after his mother’s disappearance, his world was disrupted again: Britain was at war, and material conditions grew even worse for working-class families. His father, it seems, simply withdrew himself from his son’s life. There was no open breach; there was just a vague and gentle separation. They left the house at different times – Elias for work, Archie for school – and they returned at different times. They seldom saw each other. Archie became, in effect, a latch-key child.

In September 1915, at the age of eleven, he won a scholarship to the local Fairfield Grammar School

(#litres_trial_promo) – a gabled, red-brick establishment about ten minutes’ walk from Picton Street. The Liberal government of the time offered ‘free places’ to a limited number of children whose parents could not afford to contribute financially to their education.

(#litres_trial_promo) Archie still had to pay for his books, school uniform and other necessities, however, and, in the absence of his mother, he soon came to suspect that he would probably not be able to get through Fairfield on the little money that his father gave him. As a result, his ‘aspirations for a college education slowly faded’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Elsie Leach’s smart young son was now, according to one of his former classmates, ‘a scruffy little boy’

(#litres_trial_promo) who was a promising scholar and a good athlete, but who also had a mischievous streak and was often a disruptive influence. ‘It depressed me to be good, according to what I judged was an adult’s conception of good’, Grant recalled, ‘and matters around me were not going well.’

(#litres_trial_promo) When Cary Grant made his triumphant return to Bristol on a visit in 1933, Archie Leach’s old teachers told reporters of their memories of ‘the naughty little boy who was always making a noise in the back row and would never do his homework’.

(#litres_trial_promo) The irascible piano teacher whom Archie was obliged to visit had taken to rapping the knuckles of his left hand with a ruler (he was naturally left-handed,

(#litres_trial_promo) which caused him to struggle sometimes to play as she instructed). ‘My head seemed stubbornly set against the penetration of academic knowledge,’

(#litres_trial_promo) although he admitted, grudgingly, that he quite enjoyed studying geography, history, art and chemistry. What he did become was an avid reader of comics, such as The Magnet and The Gem, as well as a popular and eye-catching footballer (playing in goal and experiencing the ‘deep satisfaction’ of being cheered when making a good save – ‘one of those fancy ballet-like flying jobs’

(#litres_trial_promo)). It was, in fact, as a result of his increasingly uninhibited sporting exploits that he suffered an accident that would alter his appearance in a subtle way: he snapped off part of a front tooth when he fell over in the school playground; the gap closed up in time, but he was left with only one front-centre tooth.

(#litres_trial_promo) Similar – if less dramatic – mishaps followed. His teachers began to give up on him: ‘I was not turning out to be a model boy.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

He found an additional outlet for his energies in the 1st Bristol Scout troop. At the end of his first year at Fairfield he volunteered for summer work wherever his Boy Scout training could be used for the war effort: ‘I was so often alone and unhappy at home that I welcomed any occupation that promised activity.’

(#litres_trial_promo) He was assigned to working as a messenger and guide on the military docks at Southampton. For two months he watched thousands of boys not much older than himself sail off towards France; some had already lost an arm or a leg in combat but were being sent back for a second time. It was a poignant experience for him, but it was also, in an odd way, an exhilarating period in his life. When he returned to Bristol, he began to spend time at the docks, where schooners and steamships sailed right up the Avon into the centre of the city. ‘You always had a sense that Bristol was a port, a gateway to somewhere else,’ he said, and, seeing the ships ‘that could take you all over the world’, he came to see the city as ‘a place you could leave, if you wanted to, and, at that age, I did.’

(#litres_trial_promo) He was restless and lonely, and it appears that he contemplated signing on as a cabin-boy until he discovered that he was too young.

(#litres_trial_promo) Although, years later, he described Bristol as ‘one of my favorite places in the world’,

(#litres_trial_promo) he admitted that, at the time, ‘I didn’t like it where I was, and I wanted to travel’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Back at the dark, quiet, cramped house in Picton Street, he was aware that his father, on those irregular occasions when he saw him, was growing increasingly withdrawn and melancholic. ‘He was a dear sweet man, and I learned a lot from him,’

(#litres_trial_promo) but as a father he no longer exerted much influence on Archie’s life. The shadow of Elsie hung over them both. Years later, Cary Grant wrote of a long-held desire to ‘cleanse’ himself ‘perhaps of an imagined guilt that I was in some way responsible for my parents’ separation’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

An opportunity to escape from the emptiness of his home life opened up unexpectedly when he encountered an electrician who was helping out in the school laboratory as a part-time assistant. Grant remembered him as a ‘jovial, friendly man’

(#litres_trial_promo) whose attitude towards his own family was considerably more responsible and positive than that of Elias Leach. This unnamed benefactor took a kindly interest in the bright but rather pathetic young boy who was clearly eager for companionship. He was also working at that time at the Hippodrome, Bristol’s newest variety theatre, which had opened in 1912; a fully electrified theatre was still something of a novelty in those days, and he offered Archie the chance to explore the house that he had helped to wire. Archie, without any hesitation, accepted:

The Saturday matinee was in full swing when I arrived backstage; and there I suddenly found my inarticulate self in a dazzling land of smiling, jostling people wearing and not wearing all sorts of costumes and doing all sorts of clever things. And that’s when I knew! What other life could there be but that of an actor? They happily travelled and toured. They were classless, cheerful and carefree.

(#litres_trial_promo)

From that moment on, Archie Leach spent as much time as he possibly could at the theatre. The electrician introduced him to the manager of the Empire, another Bristol theatre, where he was invited to assist the men who worked the limelights. There he began to learn the ways of showbusiness people, absorbing the lore of the theatre. This unofficial job came to an abrupt and embarrassing end when, working the follow spot from the booth in the front of the house, he accidentally misdirected its beam, revealing that one of an illusionist’s tricks was achieved with the aid of mirrors. Archie reappeared, his enthusiasm undimmed, at the Hippodrome, where he became a familiar sight, running errands and delivering messages backstage. His father and grandmother were, it seems, quite content to allow him to pursue his new activity without any interference. ‘I had a place to be,’ he said, ‘and people let me be there.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

During 1918, Archie recorded his daily activities in his Boy Scout’s notebook and diary, a four-by-three-inch leather-bound volume which was preserved by Cary Grant in his personal archive. A few typical entries from January of that year give one a good sense of how his free time had come to be dominated by the theatre:

14 Monday. After school I went and bought a new belt. And a new tie. Empire in evening. Daro-Lyric Kingston’s Rosebuds.

17 Thursday. Stayed home from school all day. Went to Empire in evening. Snowing.

18 Friday. My birthday. Stayed home from school. In afternoon went in town. In evening, Empire.

21 Monday. School. Wrote letter to Mary M. Empire in evening. Not a bad show. Captain De Villier’s wireless airship at the top of the bill.

22 Tuesday. School all day. In evening, Empire. All went well, first house. But second house, wireless balloon got out of control and went on people in circle. Good comedy cyclist called Lotto.

(#litres_trial_promo)

He was nearing the age when he could leave school, and he was convinced that he wanted to work full-time in the theatre as soon as he possibly could. He was watching – and often meeting backstage – a broad range of music-hall acts, and he was eager to begin performing himself. At some unrecorded point during that period, probably late in 1917,

(#litres_trial_promo) he made contact with Bob Pender, who was the manager of a fairly well-known troupe of acrobatic dancers and stilt-walkers known as Bob Pender’s Knockabout Comedians.

(#litres_trial_promo) He had never achieved the kind of success enjoyed by Fred Karno, but he was an established and respected figure on the music-hall circuit.

(#litres_trial_promo) Archie had heard that the troupe was being depleted regularly as the younger performers reached military age: ‘When I found out that there were actually touring companies who would let you perform, and take you around the world, I was amazed, and it became my ambition to join one of these travelling shows.’

(#litres_trial_promo) In a letter on which he signed his father’s name, he wrote to Pender – who was on tour at the time – offering his services (but neglecting to note that he was not yet fourteen).

(#litres_trial_promo) Pender replied favourably, inviting Archie to report to Norwich as an apprentice.

(#litres_trial_promo)

According to Cary Grant’s version of what happened, he intercepted Pender’s letter, ran away from home, caught the train to Norwich (paying the rail fare with money sent by Pender) and was placed in training with the troupe, practising cartwheels, handsprings, nip-ups and spot rolls.

(#litres_trial_promo) It took Elias more than a week to find him, eventually catching up with him in Ipswich, but whatever anger he had felt was swiftly assuaged by Pender, who was, Elias discovered, a fellow Mason.

(#litres_trial_promo) The two men agreed, over a drink, that Archie could return to the troupe as soon as he was allowed to leave school – an event that Grant later claimed he tried to hasten by getting himself expelled: doing his ‘unlevel best to flunk at everything’ and by cutting class after class.

(#litres_trial_promo)

On 13 March 1918, for some undocumented reason, Archie Leach was suddenly expelled from Fairfield. In front of the school assembly, it was announced that he had been ‘inattentive … irresponsible and incorrigible … a discredit to the school’, and that he would be leaving immediately.

(#litres_trial_promo) There are at least four distinct versions of what had happened to precipitate such a radical measure. His own account, repeated and embellished in numerous interviews, was that he and another boy had been caught as they investigated the interior of the girls’ lavatories.

(#litres_trial_promo) A second, rather less racy, version, put forward by a classmate, claims that he was found in the girls’ playground: ‘His expulsion was so unfair. Several of us girls were in tears over it, because we didn’t like to lose him.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Another contemporary insists that the reason why he was expelled was that he had been ‘involved in an act of theft with two other boys in the same class in a town named Almondsbury, near Bristol’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Years later, G. H. Calvert, a headmaster of Fairfield, could not clarify the matter: ‘I have heard various accounts of the reason for his leaving the school, but have no reason to suppose that any one of them is truer than another. Probably only Mr Grant and the headmaster of the day knew the facts of the matter, and memories play tricks …’

(#litres_trial_promo) A fourth, and perhaps most plausible, theory is that the decision to expel Archie Leach was not inspired by some singularly dramatic misdemeanour but rather was the act of a broadly utilitarian headmaster (Mr Augustus ‘Gussie’ Smith) who had – along with the practically minded Elias Leach – reached the conclusion, after a string of petty incidents, that it would be best for all concerned if Archie Leach and Fairfield School parted company sooner rather than later.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Three days later, Archie rejoined Bob Pender’s troupe. His father, on this occasion, made no attempt to restrain him, and ‘quietly accepted the inevitability of the news’.

(#litres_trial_promo) There was no legal hindrance to his re-employment. The contract between Bob Pender and Elias Leach, written in longhand, is preserved in Grant’s personal archive:

MEMORANDUM OF AGREEMENT

Made this day 9th Aug. 1918 between Robert Pender of 247 Brixton Road, London, on the one part, Elias Leach of 12 Campbell Street, Bristol, on the other part.

The said Robert Pender agrees to employ the son of the said Elias Leach Archie Leach in his troupe at a weekly salary of 10/- a week with board and lodging and everything found for the stage, and when not working full board and lodgings.

This salary to be increased as the said Archie Leach improves in his profession and he agrees to remain in the employment of Robert Pender till he is 18 years of age or a six months notice on either side.

Robert Pender undertaking to teach him dancing & other accomplishments needful for his work.

Archie Leach agrees to work to the best of his abilities.

Signed, BOB PENDER

(#litres_trial_promo)

He began taking lessons in ground tumbling and stilt-walking and acrobatic dances. He practised using stage make-up. He studied the best ways to make full use of a wide range of stage props. He was also coached in the ways of ‘working’ an audience, of conveying a mood or a meaning without having recourse to words, establishing silent contact with an audience – a skill that he later acknowledged as having helped prepare him for the special challenge of screen acting.

Archie Leach had found a teacher he trusted. Bob Pender, a stocky, robust man in his early forties, was one of the most experienced and versatile physical comedians in England at that time. His real name was Lomas, the son and grandson of travelling players from Lancashire. His wife and co-director, Margaret, was former ballet mistress at the Folies Bergère in Paris. Archie, once he joined the troupe, lived with the Penders and the other young performers, either in their house in Brixton (the area long established, because of its close proximity to the forty-one London music-halls, as the home base of many professional entertainers

(#litres_trial_promo)) or in boarding-houses on the tour circuit. It was an intense, practical and rapid education. Three months after he had left Bristol, Archie returned with the troupe to appear at the Empire. After the final curtain, Elias Leach, who had been in the audience, walked with his son back to his home. ‘We hardly spoke, but I felt so proud of his pleasure and so much pleasure in his pride, and I remember we held hands for part of that walk.’

(#litres_trial_promo) It was the closest that he had ever felt to his father.

The Pender troupe toured the English provinces and played the Gulliver chain of music-halls in London. The theatre became Archie Leach’s world, the source of his new identity; when he was not on stage, he was usually studying the other acts. ‘At each theatre I carefully watched the celebrated headline artists from the wings, and grew to respect the diligence it took to acquire such expert timing and unaffected confidence, the amount of effort that resulted in such effortlessness.’

(#litres_trial_promo) He became determined to learn how to achieve the illusion of effortless performance: ‘Perhaps by relaxing outwardly I thought I could eventually relax inwardly; sometimes I even began to enjoy myself on stage.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

While on tour, the troupe was informed that it had been engaged for an appearance in New York. It was an extraordinary opportunity for all the young performers. There were twelve boys in the company, but provision for only eight in the contract that Pender had signed with Charles Dillingham, a New York theatrical impresario. Archie Leach – much to his relief – was one of the first of the troupe to be selected. On 21 July 1920, he joined the others on the RMS Olympic – sistership to the Titanic – and set sail for the United States of America.

CULTIVATION (#ulink_832a2286-854f-5898-9b01-4fef5d2a1060)

BRINGING UP BABY

CHAPTER IV New York (#ulink_3d5d5de2-6bc4-5acb-8af6-008db49974d4)

It was an age of miracles, it was an age of art, it was an age of excess,and it was an age of satire. A stuffed shirt, squirming to blackmail in alifelike way, sat upon the throne of the United States; a stylish youngman hurried over to represent to us the throne of England.

F. SCOTT FITZGERALD

Good manners and a pleasant personality, even without a collegeeducation, will take you far.

CARY GRANT

Archie Leach wanted to become a self-made man. The idea of being a self-made man appealed to him. It made sense. He had a fair idea of what he wanted to make of himself. As Pauline Kael observed, he ‘became a performer in an era in which learning to entertain the public was a trade he worked at his trade; progressed, and rose to the top’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Archie Leach craved realism, not magic: he did not want to be dazzled, he wanted to learn: ‘Commerce is a bind for actors now in a way it never was for Archie Leach; art for him was always a trade.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Not for Archie Leach the debilitating struggles with one’s conscience about the artistic merit of what one was doing; what he was doing was, it seemed to him, eminently preferable to what he would otherwise have been forced to do back home in Bristol. His initial struggles were, primarily, materialistic rather than intellectual; the practical experience he acquired furnished him with a certain toughness of spirit that subsequent generations of performers, from more privileged, middle-class backgrounds, lacked. In Bristol, he had seen the future, and it was work – work of the soul-destroying, demeaning kind which his father had come to accept as the bald and bleak sum of his life and identity. It was not a fate that Archie Leach was prepared to face: ‘I cannot remember consciously daring to hope I would be successful at anything, yet, at the same time, I knew I would be.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Archie Leach was there, at the ship’s rail, as the RMS Olympic steamed into New York harbour in the early morning sunshine of 28 July, and he thought he knew precisely where he was going; he had seen the famous sights of New York many times before, back in Bristol, on the movie screen. He had spent much of his free time, as a child, gazing at visions of American life in the dark. Archie Leach had imagined America long before he set foot on Manhattan Island.

The Pender troupe was met by a Dillingham representative, who took them directly to the Globe Theater. It was explained, as soon as they arrived, that the plans had been changed; instead of appearing in the comic Fred Stone’s show, the Pender troupe would now open in a new revue, Good Times, at the Hippodrome. Although there was little time for them to rehearse, the troupe was not disappointed about the unexpected change. The Hippodrome, then on 6th Avenue between 43rd and 44th streets, was the world’s largest theatre: