Borrowed Finery

Paula Fox

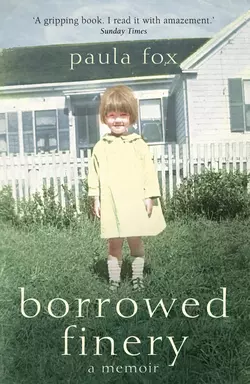

One of the most powerful memoirs of recent times.Shortly after Paula Fox’s birth in 1923, her hard-drinking Hollywood screenwriter father and her glamorous mother left her in a Manhattan orphanage. Rescued by her grandmother, she was passed from hand to hand, the kindness of strangers interrupted by brief and disturbing reunions with her darkly enchanting parents. In New York, Paula lives with her Spanish grandmother; in Cuba, she wanders about freely on a sugarcane plantation owned by a wealthy relative; in California she finds herself cast away on the dismal margins of Hollywood where famous actors and literary celebrities – John Wayne, Buster Keaton, Orson Welles – glitteringly appear and then fade away.A moving and unusual portrait of a life adrift. Paula Fox gives us an unforgettable appraisal of just how much – and how little – a child requires to survive.

Borrowed

Finery

a memoir

Paula Fox

For my family, my husband, Martin Greenberg,

and for Sheila Gordon,

who sustained me throughout this work

with her endless patience and affection

“After so long grief, such nativity!”

—The Comedy of Errors

Table of Contents

Cover Page (#u0a3158c5-e61d-5ee3-ab8b-3e71cecbf7a5)

Title Page (#u5fc3fdd4-7d41-59f0-aa54-e8f55dec55b4)

Epigraph (#ucdaf4625-6877-5efb-8038-e39c50e89be9)

BORROWED FINERY (#u70205f47-0eda-5259-bd2c-c4ff32f0e929)

Balmville (#u9e358062-c6c5-5fe5-a587-2fddd2dd45b0)

Hollywood (#litres_trial_promo)

Long Island (#litres_trial_promo)

Cuba (#litres_trial_promo)

New York City (#litres_trial_promo)

Florida (#litres_trial_promo)

New Hampshire (#litres_trial_promo)

New York City (#litres_trial_promo)

Montréal (#litres_trial_promo)

New York City (#litres_trial_promo)

California (#litres_trial_promo)

Elsie and Linda (#litres_trial_promo)

About The Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Praise (#litres_trial_promo)

Also By Paula Fox (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

BORROWED FINERY (#ulink_8c3669df-fd1c-53ce-979a-4d6325f1b1d7)

When I was seventeen, I found a job in what was then downtown Los Angeles in a store where dresses were sold for a dollar each. The store survived through its monthly going-out-of-business sales.

Every few days I was required to descend to the basement to bring up fresh stock to replace what had been sold. It was a vast space, barely lit by a weak bulb hanging from a low ceiling, and appeared to extend beyond the boundaries of the store itself. In its damp reaches I sometimes glimpsed a rat shuttling along a pipe, its naked tail like an earthworm.

Against one wall, piled up on roughly carpentered wood shelves, were flimsy boxes of dresses. In front of the opposite wall was an enormous cardboard cutout, at least ten feet high, of Santa Claus, his sled, and his reindeer. I guessed this was displayed in the store upstairs at Christmastime.

One morning when I was sent to the basement for dresses, I noticed drops of sweat on Santa’s brow. Later it occurred to me that the pipe along which I’d seen rats running extended over the cutout, and leaks could account for the appearance of sweat. But at the time I imagined it was because of his outfit. He was as inappropriately dressed for the California climate as I was in my thick blue tweed suit.

I’ve long forgotten who gave the suit to me. I do recall it was a couple of sizes too big and sewn of such grimly durable wool that the jacket and skirt could have stood upright on the floor.

I earned scant pay at a number of jobs I found and lost that year, barely enough for rent and food with nothing to spare for clothes. What I owned in the way of a wardrobe could have fitted into the sort of suitcase now referred to in luggage ads as a “weekender,” a few scraps that would cover me but wouldn’t serve in extremes of weather—and, of course, the blue tweed suit that I wore to work in the Los Angeles dress store day after day.

In that time I understood mouse money but not cat money. Five dollars were real. I could stretch them so they would last. I was bewildered even by the thought of fifty dollars. How much was $50?

The actress ZaSu Pitts, in a publicity still—an advertisement for the movie Greed made in 1923, the year I was born, that showed her crouching half naked among heaps of gold coins, an expression of demented rapacity on her face—embodied my view of American capitalism when I was a young girl. As I grew older, my attitude about money changed. I began to see how complex it was, how some people accumulate it for its own sake, driven by forces as mysterious to me as those that drive termites to build mounds that attain heights of as much as forty feet in certain parts of the world.

At the same time that I began to acquire material things, my appetite for them was aroused. Yet in my mind’s eye, the image of ZaSu Pitts holding out handfuls of gold coins, not offering them but gloating over her possession of them, persists, an image both condemnatory and triumphant.

Balmville (#ulink_8c3669df-fd1c-53ce-979a-4d6325f1b1d7)

The Reverend Elwood Amos Corning, the Congregational minister who took care of me in my infancy and earliest years and whom I called Uncle Elwood, always saw to it that I didn’t look down and out. Twice a year, in the spring and fall, he bought a few things for me to wear, spending what he could from the yearly salary paid to him by his church. Other clothes came my way donated by the mothers in his congregation whose own children had outgrown them. They were mended, washed, and ironed before they were handed on.

In early April, before my fifth birthday, my father mailed Uncle Elwood two five-dollar bills and a written note. I can see him reading the note as he holds it and the bills in one hand, while with the index finger of the other he presses the bridge of his eyeglasses against his nose because he has broken the sidepiece. This particularity of memory can be partly attributed to the rarity of my father’s notes—not to mention enclosures of money—or else to the new dress that part of the ten dollars paid for. Or so I imagine.

The next morning Uncle Elwood drove me in his old Packard from the Victorian house on the hill in Balmville, New York, where we lived, to Newburgh, a valley town half an hour distant and a dozen miles north of the Storm King promontory, which sinks into the Hudson River like an elephant’s brow.

We parked on Water Street in front of a barbershop where I was taken at intervals to have my hair cut. One morning after we had left the shop, and because I was lost in reverie, staring down at the sidewalk but not seeing it, I reached up to take Uncle Elwood’s hand and walked nearly a block before I realized I was holding the hand of a stranger. I let go and turned around and saw that everyone who was on the street was waiting to see how far I would go and what I would do when I looked up. Watching were both barbers from their shop doorway, Uncle Elwood with his hands clasped in front of him, three or four people on their way somewhere, and the stranger whose hand I had been holding. They were all smiling in anticipation of my surprise. For a moment the street was transformed into a familiar room in a beloved house. Still, I was faintly alarmed and ran back to Uncle Elwood.

Our destination that day was Schoonmaker’s department store, next to the barbershop. When we emerged back on the sidewalk, he was carrying a box that contained a white dotted-swiss dress. It had a Peter Pan collar and fell straight to its hem from a smocked yoke.

Uncle Elwood had written a poem for me to recite at the Easter service in the church where he preached. Now I would have something new to wear, something in which I could stand before the congregation and speak his words. I loved him, and I loved the dotted-swiss dress.

Years later, when I read through the few letters and notes my father had written to Uncle Elwood, and which he had saved, I realized how Daddy had played the coquette in his apologies for his remissness in supporting me. His excuses were made with a kind of fraudulent heartiness, as though he were boasting, not confessing. His handwriting, though, was beautiful, an orderly flight of birds across the yellowing pages.

Uncle Elwood made parish visits most Sundays in Washingtonville, at that time still small enough to be called a village, in Orange County, New York, seventeen miles from Balmville, where most members of his congregation lived. The church where he preached was in Blooming Grove, a hamlet a mile or so west of Washingtonville, on a high ridge above a narrow country lane, and so towering—it appeared to me—it could have been a massive white ship anchored there, except for its steeple, which rose toward the heavens like prayerful hands, palms pressed together.

Behind it stood an empty manse and, farther away, a small cemetery. To the right of the church portal was a partly collapsed stable with dark cobwebbed stalls, one of which was still used by a single parishioner, ancient bearded Mr. Howell, who drove his buckboard and horse up the gravel-covered road that led to the church. He always arrived a minute or two before Sunday service began, dressed in a threadbare black overcoat in all seasons of the year, its collar held tight to his throat by a big safety pin. He seemed to me that rock of ages we sang about in the hymn.

After the service, we sometimes called upon two women, an elderly woman and her unmarried daughter, who looked as old as her mother, both in the church choir, whose thin soprano quavers continued long past the moment when other choir members had ceased to sing and had resumed their seats. They appeared not to notice they were the only people still standing in the choir stall.

They lived in a narrow wooden two-story house that resembled most of the other houses in Washingtonville. They would give us Sunday dinner in a back room that ran the width of the house and could accommodate a table large enough for the four of us. It was a distance from the kitchen, where they usually ate their meals, and there was much to-ing and fro-ing as they brought dishes and took them away, adding, it felt to me, years of waiting to the minutes when we actually ate. Summer heat bore down on that back room. It was stifling, hot as burning kindling under the noonday sun. Everything flashed and glittered—cutlery, water glasses, window panes—and drained the food of color.

When we visited Emma Board and her family in another part of the village, I felt a kind of happiness and, at the same time, an apprehension—like that of a traveler who returns to a country where she has endured inexplicable suffering.

I had arrived at the Boards’ house when I was two months old, brought there by Katherine, the eldest of four Board children. She had taken me to Virginia on her brief honeymoon with Russell, her new husband. When they returned, her mother was sufficiently recovered from Spanish influenza to take care of an infant.

I heard the tale decades later from Brewster, one of Katherine’s two brothers, who had lived in New York City with Leopold, one of my mother’s four brothers. I had been left in a Manhattan foundling home a few days after my birth by my reluctant father, and by Elsie, my mother, panic-stricken and ungovernable in her haste to have done with me.

My grandmother, Candelaria, during a brief visit to New York City from Cuba, where she lived on a sugar plantation most of the year, inquired of Leopold the whereabouts of his sister and the baby she knew had been born a few weeks earlier. He said he didn’t know where my parents had gone, but that over his objections they had placed me in a foundling home before leaving town—if indeed they had left.

When she heard where I was, my grandmother went at once to the home and took me away. But what could she do with me? She was obliged to return to Cuba within days. For a small monthly stipend, she served as companion to a rich old cousin, the plantation owner, who was subject to fits of lunacy.

It was Brewster who suggested she hand me over to Katherine, who carried me in her arms on her bridal journey to Norfolk.

By chance, by good fortune, I had landed in the hands of rescuers, a fire brigade that passed me along from person to person until I was safe. When we visited the old woman and her daughter, or any other of the minister’s parishioners, I was diffident and self-conscious for the first few minutes. But not ever at the Boards’.

For a very short period of my infancy, I had belonged in that house with that family. At some moment during our visits there, I would go down the cellar steps and see if a brown rattan baby buggy and a creaking old crib, used at one time or another by all the Board children and for three months by me, were still stored there. I think the family kept them so I would always find them.

I was five months old when the minister, hearing of my presence in Washingtonville and the singular way I had arrived, an event that had ruffled the nearly motionless, pond-like surface of village life—and knowing the uncertainty of my future, for the Boards, like most of their neighbors in those years, were poor—came by one Sunday to look at me. I was awake in the crib. I might have smiled up at him. In any event, I aroused his interest and compassion. He offered to take me, and, partly due to their straitened circumstances, the Boards agreed to let me go.

After he finished his sermon, Uncle Elwood would step aside from the pulpit. As the choir rose to sing, he would clasp his hands and gaze down at me where I sat alone in a front pew. There would be the barest suggestion of a smile on his face, a lightening of his Sunday look of solemnity.

The intimacy of those moments between us would give way when a church deacon passed a collection plate among the congregation, now hushed by an upwelling sense of the sacred that followed a reading of Bible verse. When he reached my pew, I would drop in a coin given me earlier by Uncle Elwood.

Later, when I stood beside him at the church portal while people filed out and shook his hand, and old Mr. Howell hurried by, mumbling his thanks for the sermon in a rusty, hollow voice, the feeling of intimacy returned.

I was known to the congregation as the minister’s little girl, and thinking of that, I was always gladdened. I turned to him after Mr. Howell had vanished into the stable, noting as I usually did the formality of his preaching clothes, the pearl stickpin in his black and silver tie, a silken stripe running down the side of the black trousers, the beetle-winged tails of his black jacket.

It was like the Sunday a week earlier, and all the Sundays I could recall. I slipped my hand into his, and he clasped it firmly. I watched Mr. Howell, who had backed his buckboard and horse out of the stable and was starting down the road.

My unquestioning trust in Uncle Elwood’s love, and in the refuge he had provided for me in the years since Katherine had taken me to her mother, would abruptly collapse. In an instant, I realized the precariousness of my circumstances. I felt the earth crumble beneath my feet. I tottered on the edge of an abyss. If I fell, I knew I would fall forever.

That happened too every Sunday after church. But it lasted no longer than it takes to describe it.

Great storms swept down the Hudson Valley in the summer, especially in August. Thunder and lightning boomed and crackled. The world around the house in Balmville flashed with gusts of wind-driven rain. Through black dissolving windows, trees swayed and bent as they appeared to move closer, to form a circle of leaves and agitated branches that threatened to swallow up the house and us with it.

When the storms struck late at night, Uncle Elwood first woke me—if thunder hadn’t already—and then went to his mother’s room. He lifted her up from her bed and carried her past the large pier glass at the top of the stairs, and together we went down to the central hall, where he settled her in an armchair he would have moved from the living room earlier that day when he had first noticed black clouds forming in the sky.

Emily Corning had been crippled with arthritis for eighteen years, and she bore the pain of it with patience and austerity as though it were a hard task imposed on her to test her faith in the deity.

In the flickering yellow glow of the kerosene lamp the minister kept for such emergencies—the electricity always failed during storms—I would stare at the old woman sitting in the shadowed corner, not quite covered by a shawl her son had wrapped around her. A mild smile would touch her colorless lips when she grew aware of my scrutiny. She was unable to lift her head upright and peered at everyone from beneath her brow. She rarely spoke to me, yet I could feel kindness emanating from her just as I could feel the distant warmth of the sun in winter. Her words were few and nearly always about the view of the Hudson River, which she could see from her wheelchair, placed by the minister in front of the three-windowed bay in her bedroom all the mornings that I lived in that house.

Often at night, rarely during the day, and only when she was in terrible pain, I could hear through the closed doors between our bedrooms her gasps for breath, her faint cries, and Uncle Elwood’s efforts to comfort her. I would lie rigidly beneath the rose-colored blanket in my bed, imploring God to end what seemed endless, to let her fall asleep.

Sometimes when the thunder had diminished and only rumbled distantly, the minister would light a candle and carry his mother into the living room so she could see the dark wallpaper with its pattern of pussy-willow branches in bloom. She had chosen it decades earlier, when her husband was still living and she had been able to move freely about the house.

At an unexpected clap of thunder nearby, he would bring her back into the hall and return her to her chair, settling her into it as if she were a doll.

He told me with a humorous emphasis in his voice, so I would know not to believe him, that Henry Hudson and his crew were bowling somewhere up the river. But I half believed it.

When the minister’s only sister was visiting, and a fierce storm rumbled down the river and blew out the lights, she too sat with us in the downstairs hall, crocheting by lamp-light, her face with its pouchy cheeks bent over her work. She asked me to call her “Auntie,” which I did as seldom as possible.

As the pealing of the thunder weakened, the old woman and her daughter dozed. Their faces in repose looked sad, as if they had fallen asleep worn out by mourning a loss. Perhaps it was only a trick of the shadows.

I fell asleep too. Uncle Elwood carried me to my bedroom. As he drew up the blanket to cover me, I awoke and saw through my window the lights of Mattewan, a madhouse across the river, glittering among the leaves and branches that struck the panes fiercely as the wind blew.

Auntie had a married daughter who lived in Massachusetts. As far as I knew, she divided her time between that household and ours.

In winter, she regretted ceaselessly and aloud that the heat of the furnace, sent up through dusty registers in the floors of the living room and dining room, didn’t reach the bedrooms; in summer, that I made such a dreadful racket running up and down the stairs on my way in or out of the house it gave her headaches—why wasn’t there a rug to cover the landing?—and that the meals her brother fixed were skimpy and lacked variety—couldn’t he hire a woman on a regular basis to cook and clean, instead of the patchy arrangements with Mrs. So-and-So down the road?

She complained to her brother, when I was within hearing distance, that he gave too much time to certain parishioners of his church—whose services she attended rigorously, a baleful presence among the congregation.

Her voice was often shattered by fits of coughing. She smoked cigarettes, somewhat furtively, and carried a pack of them in a cloth bag, along with scraps of cotton or wool with which she rapidly crocheted small rugs and blankets in colors that suggested mud or blood or urine.

The cloth bag had a wooden handle and was embroidered with a design that made me uneasy. Perhaps it was the reddish entwined loops that led me to think of the copperhead snakes Uncle Elwood had warned me about, lurking in the woods in spring.

Auntie spent most afternoons murmuring to her mother, leaning over in a chair drawn so close to the wheelchair I thought she might topple over. She appeared to be about to creep into the old woman’s lap.

But the way she sat was not a posture of intimacy, I think now, or of childlike dependence. Even then I sensed there was resentment in the way she thrust her body at her mother, as though the older woman were still responsible for its miseries.

Could she be telling the story of her divorce over and over again? Uncle Elwood said that she and her husband no longer lived together. They had been divorced. Such an event had never before occurred in the family.

He looked startled as he spoke of it, as though the news had just reached him, although by the time he told me about it, it was old news. Could you escape from a divorce the way you could from a marriage? Was it possible to get a divorce from a divorce?

When the old woman’s windows were open and a breeze blew through the room, it wafted Auntie’s particular odor toward the doorway where I had paused on my way somewhere—a disagreeable smell composed of tobacco, mothballs, and the cough drops she sucked between cigarettes.

If she wasn’t crocheting or whispering to her mother, she followed me about the house, wheedling and hectoring by turns. She was the peevish serpent in the short-lived Eden of my childhood.

There was a three-legged stool in old Mrs. Corning’s bedroom that I sometimes moved from its usual place in a corner to her wheelchair and sat on, close to her motionless legs.

Earlier in the day, the minister would have lifted her to a sitting position on the edge of her bed, carried her to the bathroom, placed her on the toilet, waited outside the door until she signaled she was through, brought her back to her room, dressed her in one of her three or four print dresses, and carried her to the wheelchair in front of the bay windows, where she would spend the day until early evening, when he would carry her back to her bed.

She wore soft wool slippers.

She was as unmoving as a woman in a painting. When the day was fine, the sky unclouded, one of those blue American days full of buoyancy and promise that seemed to occur only when I was small, she might break the tranquil silence between us with a remark about the river. How beautiful it always was, she might comment, in her rather toneless voice. She could see Polpis Island and glimpse a bit of West Point just beyond the Storm King mountain. Then she would slip back into silence as though resuming a dream.

Uncle Elwood told me she had been a widow for many years. The dream might have been about her husband, how she had stood with him on the deck of a steamboat, northbound on the Hudson River, and he had seen the land that he would purchase months later to build a house on for her, this very house where she still lived, an old woman confined by illness to a wheelchair.

I looked at her hands, which lay on the wood tray fitted between the chair’s arms. They were so twisted they looked like small knobbed claws pointing at each other.

Very slowly, she bowed her head even farther down and smiled at me. It was an impersonal smile, as if pain had worn away any distinctive traits that might have defined her nature. As I looked up at the slight widening of her mouth, I imagined I recognized a kind of incorporeal kindness—and I think for those few minutes she was able to stand apart from her wounded body.

I couldn’t conceive of Uncle Elwood’s struggle to make do with the yearly salary he was paid by the church so that it would take care of his mother, himself, and me, along with paying for repairs to the ailing house, any more than I could have conceived of the lives of my parents unfolding somewhere in the world. And I would not have known how poor the Blooming Grove parishioners were, how they could barely afford a pastor of their own.

Behind his mother’s closed door, I could hear him telling her, in a voice made loud and incautious by desperation, that he had to replace the coal furnace—which he had to stoke every evening and morning when the weather turned cold—with an oil burner and that the house required a new roof. It leaked so shockingly, he said, he could fly to Jericho!

At his words, fly to Jericho, my heart jumped into my throat. It was the most extreme thing I ever heard him utter. He was at the end of his rope! It was the absolute limit!

His protests never lasted more than a few minutes, but the pictures that formed in my mind, evoked by the distress I heard in his voice—usually so serene, so playful—frightened me.

The malevolent furnace, as it labored at night with great clankings, would climb the stairs and kill us with fire, and the holes in the roof would be enlarged so drastically we would be exposed to the merciless night sky and its rain and wind and cold.

But more terrible by far was the well in the middle of the meadow.

When the water pressure in the house was so low that only a puff of stale air came from the kitchen faucet when it was turned on, and the toilet in the bathroom wouldn’t flush, Uncle Elwood set out for the well, carrying a bucket.

I watched in dread from the living room window as he lowered the bucket by a rope tied to his hand. He leaned far out over the edge of the well—too far!—to keep the rope straight as it dropped an instant later, to hit the water with a plonk.

He would fall! An enormous jet of well water would lift his drowned body toward the sky, then flood the whole earth!

He hauled on the rope, hand over hand, and at last pulled out the bucket, filled. When I ran out of the house and down the three broad steps of the porch to meet him, he was surprised at the intensity of my relief, as though he had returned safely from a long perilous journey.

Then he recalled what I had told him of my fear when he went to the well. He spoke reassuringly to me, as he did when I was ill. He told me what a fine artesian well it was, how milk snakes kept the water pure. Oh, snakes! Worse!

With his unengaged arm, he clasped me to his side as we walked across the hummocky ground. I was not able to explain to him the extremity of my terror. I couldn’t explain it to myself.

Time was long in those days, without measure. I marched through the mornings as if there were nothing behind me or in front of me, and all I carried, lightly, was the present, a moment without end.

From the living room there were views east and south. A line of maple trees and birches marked the southern boundary of the property, and beyond it stood an abandoned mansion. I had walked along its narrow porch among six towering columns and peered through dusty windows at its empty rooms. The ground sloped gently down to the river less than a mile away. It was the same long slope upon which our house stood.

From the windows that faced east, beyond the line of tall sumacs, rose a monastery whose roofs and towers I could see in late autumn and winter, when the deciduous trees surrounding it shed their leaves. At intervals during the day the monastery bells pealed.

When I sat on the porch in my wicker rocking chair in the twilight of a summer’s day, eating a supper of cold cereal and buttered bread, I would echo the sounds the bells made by tapping my spoon against the side of the china bowl that had held the cereal. I was alone with my thoughts. They drifted through my mind like clouds that change their shapes as you gaze up at them.

To the north where the storms came from, I could view from the windows in the minister’s study a line of tall, thick-trunked evergreen trees and, as though I were on a moving train, catch glimpses of a crumbling wall and some of its fallen stones lying on the pine-needle-strewn ground. Uncle Elwood said the wall had been there when his father bought the property.

Beyond the lawn, which he tended now and then, doggedly and with an air of restrained impatience, pushing a lawn mower with rusty blades, were meadows grown wild. Once or twice a year, a farmer driving a tractor, his wife and their children in a small ramshackle truck behind him, arrived to cut the tall grass and carry it away.

Once the children brought along a sickly puppy and showed it to me. We passed its limp body among us, caressed it, and at last killed it with love. We stared, stricken, at the tiny dog lying dead in the older boy’s hands, saliva foaming and dripping from its muzzle. The younger brother began to grin uneasily.

Later that day, after the farmer and his family had departed, I told the minister I had had a hand in the death of the little animal. Although he tried to comfort me, to give me some sort of absolution, I couldn’t accept it for many years.

Even now, I am haunted from time to time by the image of a small group of children, myself among them, standing silently at the back door of the house, looking down at the corpse.

Every spring, thawing snow and rain washed away soil from the surface of the long driveway, leaving deep muddy furrows and exposed stones. I spent hours cracking the stones open, using one for an anvil, another for a hammer, to find out what was inside them. Most appeared to be composed of the same gray matter, but a few revealed streaks of color and different textures in their depths or glinted with sparks of light.

I saw how Uncle Elwood struggled to hold the steering wheel of the car steady as it heaved and skidded along the rough, wet, torn-up ground. But I thought too of how gratifying it was when I found a stone that stood out from the rest because of what was inside it.

The driveway led up to scraggly, patchy lawn, circled the house, then branched off, ending several feet from the entrance to a cave-like, half-collapsed stable that had been built into the side of the slope. Earth nearly covered its roof.

During storms, the minister would race out to the car and drive it into the stable as far as it would go. Once a horse named Dandy Boy had lived in its one stall.

The minister told me stories that illustrated Dandy Boy’s high spirits and animal nobility. “He had moxie,” he said, and imitated a horse, galloping from the living room where I stood entranced, laughing, into the dining room just as Dandy Boy had galloped into the world.

A while later he took me to a Newburgh soda fountain and ordered a glass of Moxie for me. It had a spiky, electric taste. I imagined Dandy Boy drinking pailfuls of it and afterward rearing up like a cowboy’s horse.

In those days there were two movie theaters in Newburgh. Uncle Elwood only took me to movies he had seen, to make sure there was nothing alarming in them. My knowledge of cowboys was limited. But I had seen a Western in which they figured. I was struck by how they clung with their knees to the saddle when their horses circled in one spot and raised up on their hind legs, pawing the air with their hooves as they did in illustrations of books about knights and kings and queens.

When Uncle Elwood returned from evening church functions, he parked the car on a gravel-covered stretch of the driveway next to the house. Nearby stood a few crab-apple trees, neglected but still bearing wizened fruit in autumn. Every autumn she spent with us, Auntie promised to make crab-apple jelly, but she never did.

On those church nights after I was sent to bed by Auntie, or by a neighbor who had come to the house to watch over Uncle Elwood’s mother and me, I could never fall asleep, even though my eyelids were often as heavy as stones. I listened, it seemed, with my whole self for the sound of tires rolling on gravel, then halting, then the growl of the engine as it was turned off, a minute of silence, a car door opening and shutting, and not a minute later Uncle Elwood’s footsteps on the stairs.

If he came home before dark, I ran to greet him at the front door. If he walked in looking pleased with himself because he had a secret, I would search through his pockets until I found a white paper sack filled with the chocolates he had stopped to buy on his way through Newburgh, and that he and I loved.

One evening he returned from church early. I was still up. There were seven cakes on the back seat of the Packard, each one different, and all made for his birthday by women in the Ladies’ Aid Society of the church.

“How shall we ever eat them, Pauli?” he wondered in the hall, looking at the cakes lined up on a table. One by one, I thought to myself.

In late spring, you pluck a blade of tall grass, place it between your thumbs, align it, and blow. The sound you produce is unmelodious, excruciating—and triumphant.

Four bedrooms on the second floor were grouped about the hall landing. There was a bathroom, and a small study with two windows and a narrow door leading out to a balcony that arching, leaf-heavy branches kept cool in the summer. On the same floor, behind a door usually kept closed, was another part of the house and a fifth bedroom claimed by Auntie when she came for one of her visits. It was unbearably hot there in summer, glacial in winter. From a passageway outside of it, a narrow flight of steps led down to the kitchen and another flight up to the attic.

The dusty stillness of that shut-off part of the house was often broken by me, by the sound of my footsteps as I climbed the stairs to the attic, or by the dull buzz of flies trapped between screen and window in the bedroom, or by spasms of coughing and the muttering-to-herself fussing of Auntie on one of her visits, the one I feared might be without end.

She had chosen the room for herself before I was born and appeared to be gloomily satisfied with its discomforts: extremes of temperature, an iron bedstead with a thin mattress covered with stained ticking, a bare floor, and little else. Were some of the rugs she crocheted meant for the floors of her daughter’s house? How did she dispose of the ones I had seen her make?

Behind the door that closed off that uncanny space, I pictured Auntie lying on her back in her bed, her eyes opened wide and unblinking, smoking cigarettes in the dark.

I spent rainy afternoons in the attic, treading warily on the rough planks that served as flooring, hopping over the holes in which I could glimpse shadowy crossbeams where the jagged edges met, and where I feared spiders might lurk. There were five or six small rooms whose walls ended halfway up, and I could look through them to their windows that hardly let in light, they were so covered with webs and dust. Boxes were stacked everywhere. There was a huge metal birdcage, a dressmaker’s form, canes, a top hat, and a moth-eaten black dress coat. Books moldered in heaps, and trunks with lids too heavy for me to lift decayed in corners. Except for my footprints, dust covered everything.

On the top steps of a narrow flight of stairs, alongside a collection of faded postcards, were piles of National Geographic magazines. I looked through them again and again. As I turned the glossy pages, I was startled each time by the singularity of everything that lived, whether in seashells, houses, nests, temples, logs, or forests, and in the multitude of ways creatures shelter and sustain themselves.

One early afternoon—I had not yet learned to read—I was sitting on a step below the landing, an open book on my lap, inventing a story to fit the illustrations. It was raining. From the little table on which it sat in a dark corner at the foot of the staircase, I heard the telephone ringing. Uncle Elwood came from his study to answer it. “Mr. Fox?” I heard him ask in a surprised voice.

I flew up the stairs to my room, closed the door, and got under the bedclothes. Soon Uncle Elwood knocked on the door, saying the call had been from my father, Paul, who was in Newburgh, about to take a cab to Balmville. “Won’t you open your door?” he asked me.

The word father was outlandish. It held an ominous note. I was transfixed by it. It was as though I had emerged from a dark wood into the sudden glare of headlights.

Uncle Elwood persuaded me at last to come out of my room. He looked back to make sure I was following him down the stairs. After the alarm set off in me when I heard “Mr. Fox,” I felt flat and dull. In the living room I stared listlessly at a new National Geographic lying on the oak library table next to an issue of the Newburgh News, open to the page where the minister’s weekly column appeared. On top of the big radio with a pinched face formed by various dials, on which we listened to Amos and Andy, there was a bronze grouping, a lion holding its paw, lifted an inch or so above the head of a mouse. I had gazed at it often, wondering if the lion was about to pat the mouse or kill it.

I had not longed for my father. I couldn’t think how he had known where to find me.

I wandered into the hall, pausing before a large painting I had seen a thousand times, a landscape of the Hudson Valley. Dreaming my way into it, I walked among the hills, halted at a waterfall that hung from the lip of a cliff; in the glen below it there was an Indian village, feathery columns of smoke rising straight up from tepees. The painting was bathed in an autumnal light as yellow as butter, the river composed of tiny regular waves that resembled newly combed blue-gray hair, gleaming as though oiled.

I heard loud steps on the porch. My father suddenly burst through the doors carrying a big cardboard box. He didn’t see me in the shadowed hall as he looked around for a place to set down the box.

In those first few seconds, I took in everything about him; his physical awkwardness, his height—he loomed like a flagpole in the dim light—his fair curly hair all tumbled about his head, and his attire, odd to me, consisting of a wool jacket different in fabric and pattern from his trousers. He caught sight of me, dropped the box on the floor, its unsealed flaps parting to reveal a number of books, and exclaimed, “There you are!” as if I’d been missing for such a long time that he’d almost given up searching for me. Then at last!—I’d turned up in this old house.

Not much he said during the afternoon he spent with me had the troubling force of those words, and their joking acknowledgment that much time had elapsed since my birth.

I felt compelled to smile, though I didn’t know why.

I bent toward the books. I guessed by their bright colors that they were meant for me. Eventually Uncle Elwood read them all aloud: Robin Hood, King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table, Tom Sawyer, Water Babies, Aesop’s Fables, A Child’s Garden of Verses, The Jungle Books, and Treasure Island.

At some happy moment, I lost all caution. When my father got down on all fours, I rode him like a pony.

It was twilight when he left. The rain had stopped. As he turned back on the bottom porch step to hold up his arm in a salute that seemed to take in the world, and before he stepped into the taxi he’d ordered to return for him, the sun emerged from a thick cloud cover and cast its reddish glow over his face as though he’d ordered that, too.

The next morning, I woke at first daylight and ran down the staircase to the living room in my nightclothes, knowing—against my wish to find him there—that I wouldn’t.

From the earliest days of my time with him, Uncle Elwood read to me every evening. A few months after my fifth birthday he began to teach me to read. From being a listener—a standing I hadn’t thought about until I had the means to change it—I became a reader.

The bookshelves in the living room held works of poetry, books about national and local history, and, as I recall, stories by Mark Twain and Rudyard Kipling, among others. I memorized “If,” a poem by Kipling, and in historical sequence the names of the American presidents. I would recite aloud the poem and the presidential roll call, to elicit a look of pride on the minister’s face.

I read a daily children’s story in the Newburgh newspaper. It was accompanied by a drawing of a rabbit wearing a jacket and waistcoat, and the central character was an American version of Beatrix Potter’s Peter Rabbit, but plumper, far more sanguine, and never exposed to the slightest serious danger. I read the funny papers on Sunday, the Katzenjammer Kids, Moon Mullins, The Gumps, Maggie and Jiggs, and Harold Teen; the last-named I disliked intensely, for reasons I don’t recall.

I was free to read any book in the house, but what comes first to memory is my deciphering of the old postcards that lay in heaps at the top of the attic steps. Most had been mailed from foreign capitals before the Great War and showed vistas of Rome and Paris, Berlin and London. On the writing side, there were messages in the spidery but legible penmanship of those days. As I read them, I thought I could hear the ghostly utterances of the travelers, Uncle Elwood’s long-departed kin.

Around the time I learned to read, a woman named Maria and her three-year-old daughter, Emilia, moved into the house. Uncle Elwood had hired her to cook and clean and to watch over his mother when he and I were out. She and her child settled into Auntie’s bedroom.

When she came, Auntie used my bedroom, and I slept on a cot in the study. I hardly remember Maria. Uncle Elwood told me she had been born in a faraway country, Montenegro. But with no effort of memory Emilia’s face appears instantly in my mind’s eye, perhaps because among the few photographs I have from those years, there is one of the two of us.

In the photograph, she is sitting outdoors in my wicker rocking chair. Her legs, too short to reach the ground, stick straight out; her hands grip the rounded arms of the chair. Her black ringlets are clustered like Concord grapes around her little face. She is fretful. Her mouth forms an O. I am standing beside the chair. My left arm lies possessively along its curved back. I am looking down at her. My expression is troubled, angry.

Uncle Elwood takes the picture. He stands a few feet away from us. She has begun to cry in earnest, noisily. As usual, I tell myself. Her mother comes out of the house and picks her up, murmuring to her. Uncle Elwood joins me where I am standing beneath the branches of a crab-apple tree. He takes my reluctant hand. “Shall we go for a walk, Pauli?” he asks. I nod wordlessly.

Maria stayed with us for less than a year. Then, for reasons not explained to me or that I’ve forgotten, she placed Emilia in a Catholic ophanage and left Newburgh.

Uncle Elwood and I visited Emilia several times. A nun led us down a hall and into a barely furnished room smelling of floor wax, with starched white curtains at both windows. It was around noon. A distinct piercing smell that I recognized as beef broth floated in the air. One of the windows was open a crack, and a breeze kept the curtains waving like banners.

Emilia came into the room and sat down on a wooden bench, smiling uncertainly in our direction. She was dressed in a white blouse and a blue pinafore. Her curls were flattened by hair clips. She was probably four years old at the time. I don’t know what we spoke about or if she spoke at all.

What I felt was the force of my longing to move into the orphanage that very hour. I wanted for myself the aroma of broth, the white starched curtains, the clothes Emilia wore, the nuns with their pale moon faces and black habits.

Emilia looked so calm, so rescued.

I grew aware that Uncle Elwood’s public life consisted of more than preaching sermons. He wrote a weekly column for the Newburgh News called “Little-known Facts about Well-Known People.” He told me that before he’d been called to the ministry, he’d been a journalist working for a newspaper in Portsmouth, Virginia.

I spelled out his name on the spines of several books set apart on the living room bookshelves. Among them were a history of the Blooming Grove church, a collection of his own sonnets, a biography of the twenty-fifth president of the United States, William McKinley, and a slim volume about the winter George Washington spent at his headquarters at Temple Hill, at that time a bare site not far south of Newburgh.

Years later, when a replica of the headquarters was erected, it was partly paid for with funds raised by the minister.

When Auntie visited, or during the months Maria worked for him, Uncle Elwood was free to explore the countryside and chase down clues to Hudson Valley history, many of them given to him by people in his congregation. One time he told me, an expression on his face that somehow combined horror and fastidiousness, how Indians had killed the infants of settlers by grabbing their feet and swinging them against tree trunks. He often quoted Washington’s whispered question on his deathbed—so it had been reported—“Is it well with the child?” Uncle Elwood explained to me that the first president had meant the new country; the new country was the child. I repeated the words silently, not sure whether I meant the country or myself.

“We’ll drive there like blazes!” he would declare, after he’d been told where there might be a foundation of a house built during the American Revolution or a tumbledown ruin that could have been built even earlier.

Once when we were walking in the woods somewhere, we stumbled upon an Indian burial ground, the mounds fallen in and covered with moss, and a light broke over his face. He treated the Hudson Valley and his ministry with the same ardor, as though both historical discovery and biblical allegory were equal manifestations of the divine.

We took trips.

We drove south to Nyack, a town on the western shore of the Hudson, to visit a cousin of Uncle Elwood’s, who had recently had a house built for herself and a woman friend.

The river glinted in shards of light. Light-colored stones formed a promenade next to the house. The rooms were open, without doors; whiteness hung like a great curtain outside vast windows. The cousin’s name was Blanche Frost.

She gave me a doll she told me she had bought in Paris.

“Where is Paris?” I asked the minister in a whisper, awed in the presence of the tall woman with such beautifully arranged white hair.

“Across the sea, in a country called France,” he told me.

The doll’s long yellow hair was held back from its face by a raspberry-colored ribbon, the same color as its startling dress, very short, revealing long light-pink cloth legs. I put it in my bookcase at home. For weeks, it was the last thing I looked at before I fell asleep.

We drove to Elmira, New York, to see Mark Twain’s grave. It was a happy moment afterward, to sit in the sunlight on a nearby slope among the gravestones. The minister had on his high-crowned Panama hat, so it must have been August, the only month he wore it.

We went to Albany. In the governor’s mansion, or the state-house, I forget which, the minister pointed to a deep scar in the banister of the broad staircase, made by a tomahawk hurled by a long-dead Indian.

We descended by elevator to the Howe caverns. The deep shaft down which we traveled looked like a giant’s work; the earth split open just like the stones I had pounded on the long driveway.

One morning we were to go to West Point, where Uncle Elwood was to give an invocation at a military ceremony. We had to take the Storm King mountain road to get there. A snake coiled to strike would not have frightened me more than the snakelike curves of the road. At its highest point, where the rock face soared above and dropped to the river below, a sign warned of a zone of falling rocks. When we came to it, I drew up my legs and shut my eyes tight, expecting to be crushed by a boulder or flung out into space. When the road leveled out, I thought, This time we got away with it.

Uncle Elwood read me stories by Washington Irving, Rip Van Winkle and The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, out of whose pages a headless horseman pursued me into a dream. I told him I was haunted. Soon after, he took me to Sunnyside, Irving’s estate near Tarrytown on the east side of the Hudson. Perhaps by showing me evidence of the writer’s existence, he thought to exorcise the horseman.

In Balmville, just at the start of the dirt road that led home, there stood a very old Balm of Gilead tree encircled by an iron fence. Uncle Elwood told me that Washington was said to have taken shelter beneath its outstretched boughs during a sudden downpour. I could imagine the general standing there, looking as he did in a large portrait of him that hung in Uncle Elwood’s study: cloaked, pink-cheeked, white-haired, with a marionette’s stiffness of jaw. We often paused at the tree, the car motor idling, when we returned from our travels.

A mile or so away from the tree was the Delano home where we were once invited to tea. It was during the period when a family member, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, was governor of New York State. I might have forgotten the grandeur of the house and of the great winding staircase if I had not for the first time glimpsed the possibility of beauty in clothes, watching two little Delano girls hovering like butterflies about the table in white organdy dresses, slipping little cakes into their mouths.

We went to a neigboring town to attend a dinner given for a bishop. He sat at the head of a long table. During a lull in the general conversation, I asked the bishop, “Do you like me?” and he replied, “Don’t you think your question is a little premature?”

I was chagrined. Later, when Uncle Elwood smiled as he told people the story of my question and the bishop’s response, I was confused by the currents of pride and shame running through me and felt a small pinch of estrangement from him.

Uncle Elwood wrote his sermons and newspaper columns on an Underwood typewriter on a table that stood in the middle of his study. It was a large, square, plain room with big windows. On fair days, when the light poured in, it seemed to float. Books lined one wall. Against another was an immensely tall desk that suggested a Chinese temple I had seen in an issue of the National Geographic. It had many tiny doors, which opened to dusty secret passages. In little drawers, mostly empty, there were piles of foreign coins, mementos of trips to Europe, and a piece of yellowed hardtack that Uncle Elwood told me dated from the Civil War. I would surprise myself with it, the last thing I examined before I got down from a high desk chair. I had to fight off an impulse to eat it.

On the wall beside the desk there hung a photograph of Edwin Markham, the poet, and he had written a few lines from his poem “The Man with the Hoe” in the open space beneath it. He had more beard than face. I invented a story: He was the missing one of the Smith Brothers whose cough drops came in a box illustrated with sketches of themselves, bearded and disembodied, that Uncle Elwood brought home for me when I had a sore throat or a cold.

Except for an occasional clatter of typewriter keys, there was a companionable silence between us. He asked me once, “What shall I preach about next Sunday, Pauli?”

“A waterfall,” I replied at once. I had just been thinking about a recent picnic we had on the shore of a stream fed by a small cascade whose spray dampened our sandwiches and us.

I can still recall the startled pleasure I felt that Sunday in church when I realized his sermon was indeed about a waterfall. I grasped consciously for an instant what had been implicit in every aspect of daily life with Uncle Elwood—that everything counted and that a word spoken as meant contained a mysterious energy that could awaken thought and feeling in both speaker and listener.

An ancient parishioner, “old as the hills,” Uncle Elwood observed, died in her sleep. He was named executor in her will. A few days after her funeral service in the church, we went to the Washingtonville boardinghouse where she had lived for many years. Her room had not been touched. The unmade bed, a half-pulled-out drawer in a small bureau, gave the place a disheveled look. Uncle Elwood walked across the dusty floor to a window, threw it open, and dusted his hands in a finicky way.

There was a hard-hearted aspect to his nature. Perhaps he had grown too accustomed to the dying, to death. We spent less than fifteen minutes in the room. He collected a few papers from a table and plucked, from a tangle of threads and spools in a sewing basket, a small ring with an amethyst stone that he gave me on the spot.

He spoke to the elderly landlady who was fluttering about in the hallway, asking her to pack Miss Hattie’s things, keep whatever she liked, and give the rest to charity.

On our way home that day, he parked the car in front of a large house on the outskirts of Newburgh. Its roof formed steep hills, each one crowned with a chimney. Uncle Elwood sat in silence for a moment, his hands resting on the steering wheel.

Several years earlier, he told me, before he had brought me home to live with him, he had been on what he called a “thinking walk” in a field near Balmville. Suddenly he heard alarmed cries from a neighboring field. He turned to see that an untethered bull was about to heave itself at a young woman who, at that very second, hiked up her skirt and turned to run away from it. He diverted the animal by presenting himself as a target. The woman escaped and so did he. That was how he met Elizabeth, the person we were about to visit in the many-chimneyed house.

After the incident with the bull, they had become friends. A year or so later she fell ill and was now largely confined to her bed. Despite her loss of health, he proposed marriage to her. Regretfully, she refused him. All this was told to me in a tone in his voice I’d not heard before—elegiac, I tell myself now.

“Would you like to visit her?” he asked. I was curious and said yes. I couldn’t conceive of him other than as a nurse to his mother, a savior for me, and the shepherd of what appeared—if I thought about it at all—as a world full of ungainly sheep stumbling along behind him, but never as someone’s husband.

A maid opened the front door to us, and we followed her up a flight of stairs and into an enormous overheated bedroom crowded with furniture. A woman reclined in the bed against a pile of pillows almost as high as a hayrick. Her face was pale beneath her piled-up, silky-looking gray hair. Her thin listless hands lay on the coverlet. Her voice was pleasant and utterly assured.

Remembering its resonance, I now wonder if her illness, a thyroid imbalance, was itself the source of her self-confidence. After all, whatever its miseries, it had eliminated the necessity of making a choice, and the attendant anxiety that might have been aroused.

Her evident interest in me was puzzling. I grew conscious of my breathing and aware at the same time that I felt alone, cut off from Uncle Elwood. I moved to his side. For a while I was relieved that Elizabeth had turned his proposal down.

Laughter erupted from Uncle Elwood like a Roman candle, and at its peak he might exclaim, in a choked voice, “Killing!”

I learned I could evoke his laughter by imitating people, especially old Mr. Howell. There were other ways I contrived to set him off, some more successful than others.

One day he brought home a dog, a chow with bushy rust-colored fur and a tongue as black as licorice. He called him Ching. The dog was amiable, if reserved, with me.

On an early evening, Uncle Elwood drove to Newburgh to do an errand and took me along. Ching sat on the backseat, and I joined him there after Uncle Elwood had parked and left the car with his customary quickness of movement.

The dog was wagging his tail in a leisurely fashion. Uncle Elwood’s gray suede gloves were lying where he had tossed them on the seat. One thing led to another. I pulled a glove down over Ching’s tail and hid on the car floor, murmuring to Ching so he would keep up his tail wagging, hugging myself in anticipatory glee as I visualized Uncle Elwood’s face when he caught sight of a hand waving at him through the rear window.

I heard his rapid returning steps on the sidewalk. He paused a few feet from the car. It was absolutely still outside. I nearly shrieked. Then the door opened. “Pauli!” he exclaimed in apparent astonishment, his eyes crinkling with laughter.

In later years, I realized that Ching and I hadn’t fooled him for an instant, that what his laughter had expressed was appreciation of my cunning as he stood near the car, his attention momentarily caught by the flicker of a slowly waving gray hand.

On a September morning a few months after my fifth birthday, the minister drove me to the public school a mile or so away. After a few weeks, I was allowed to walk home with the four or five children who lived along the road.

Miss Hamilton taught first grade. She was plump and friendly. Her hair was bound about her head like a black silk scarf. Her dark eyes were large and slightly protuberant.

Three classmates stand out in my memory from those days: Lester, a tall farmer’s son who wore the same faded overalls every day—I realized this when I noticed the same stains in the same places—and who had grayish skin and a wedge-shaped head he held stiffly as he slouched and shambled around the classroom; Lucy, who became a friend; and Freddie Harrison, in whose presence I often lost my breath and was unable to speak. How did Uncle Elwood know about the joyful consternation I felt in those moments when Freddie and I passed by each other in the classroom or stood silently together in the school playground?

One warm afternoon, Lucy came to visit me. We drew what we conjectured to be male genitals on the blank backs of paper dolls, our heated faces close together as we crouched under a yellow-leafed maple tree near the stone wall. I don’t know what we were hiding from unless it was our own prescience of sexual love. In any event, we weren’t far off the mark.

I had a curious view of the world and its inhabitants. I imagined people were lodged inside the earth like fruit pits, and I was perplexed by the visible sky. Miss Hamilton substituted an even stranger view, that we all lived upon the earth’s surface. How was it we didn’t fall and tumble forever through space?

I walked home with the other children on the dirt road. It curved steeply at its beginning, and on the rise we passed a fieldstone house in a huddled mass of trees that hid it from sunlight. It looked emptier of life than the little graveyard behind it, where two or three tombstones had fallen over onto the ground. It all had a brooding character that stirred and frightened me. Its lightless windows looked like the eyes of a blind dog.

Gradually the other children glided away, down paths or rutted roadways, their faces assuming a certain blankness of expression they would wear indoors for the first minutes after they reached home, as my face did, until there was only one left, Gordon, a tall boy with a cap of black curls, who lived a half mile beyond my driveway and with whom I walked in an easy silence.

Car headlights shone on ranks of stunted pine trees and clumps of small weathered gray houses, silent, silvered for an instant as we drove past them. Who was driving, Uncle Elwood or my father, I can’t recall. We were on our way to Provincetown at the tip of Cape Cod, where my parents were living in a house on Commercial Street. Soon after my stay of a few days, when they were away, it burned to the ground—the fourth fire started by the retarded son of a Portuguese fisherman.

The house, a saltbox, was set back from the street a few hundred feet on the hummocky undernourished ground characteristic of land near salt water. I have a snapshot of myself standing in front of a straggly rosebush growing on a rickety trellis in the yard, its stems like insect feelers. There is another photograph of Uncle Elwood and me by the bay. He kneels to hold me around the waist, although there is no surf; the water is as flat as an ironing board. I suppose my father took the picture with the minister’s camera.

A German shepherd my parents owned attacked a cat that was drifting along the narrow cracked sidewalk in front of the house. My heart thudded; my vision narrowed to the two animals, one helpless, the other made monstrous with rage. I grabbed the cat. In its terror, it scratched my hand.

There was no one in the house that day to whom I could report the scratch. I washed my hand at the kitchen sink, standing on a chair to turn on the faucet. The wound bled intermittently for a while. When my parents returned from wherever they had been, I didn’t bring it to their attention.

I discovered a steamer trunk in a little room next to the kitchen. It was on end and partly open, like a giant book waiting to be read. Deep drawers lined one side. Suits and dresses hung in the other. They looked as though they’d been pitched across the room, arrested in their flight by small hangers attached to a metal bar, to which they clung, half on, half off.

I had never seen so many women’s clothes before. I touched them, felt them, pressed against them, breathing in their close bodily smell until I grew dizzy. I pulled open a drawer and discovered a pile of cosmetics.

I hardly knew what they were for, but memories stirred of Uncle Elwood’s mother, asking that her face be powdered when she was about to be taken for an outing in the car and a large powder puff in his hand as he bent toward her face, or the lips of some of his parishioners, too red to be true.

My mother was suddenly in the room, as though deposited there by a violent wind. I gasped with embarrassment and fear. She began to speak; I saw her lips move. I bent toward her, feeling the fiery skin of my face.

“What are you doing?” She was asking me over and over again. I heard her repeat “doing…doing” in the same measured voice, as she stared at my forehead covered with her powder, at my mouth, enlarged and thickened with lip rouge I had discovered in a tiny circular box.

I began to cry silently. Her face loomed in front of mine like a dark moon. She began to whisper with a kind of ferocity, “Don’t cry! Don’t you dare! Don’t! Don’t cry!”

I covered my face with my hands. She pushed in the trunk drawers and straightened the clothes. I sensed that if she could have hidden the act, she would have killed me.

I stood there, waiting for permission to stay or to leave. She left the room as though I weren’t there.

There was a party that evening. The noise of it came up the narrow stairs to the alcove where I lay on a cot, listening. It was like the sound of the ocean roaring in a seashell.

Grandfather Fox appeared at the Balmville house one afternoon. I sat on his bony lap and asked him why he sometimes whistled as he spoke. “False teeth,” he replied.

I couldn’t recall seeing him before. He seemed pleasant if close-mouthed. I wondered if it was because he didn’t know me despite the fact that there I was, sitting on his lap. Perhaps I was being premature, as I had been with the bishop.

Then he said to Uncle Elwood, with no reproach in his voice, “You are ruining my son,” and I understood that until that moment he had been holding back those words as if they were hard little pebbles, rolling around in his mouth. I didn’t understand what they meant.

When I was a few years older, my father told me his father had attended a German university, where he had taken a degree in philosophy. Most of the other students had saber scars on their faces from the duels they had fought.

My grandmother Fox, Mary Letitia Finch, had been one of five sisters, my father said. When admirers came to court them, their father would stomp into the living room, lift out a sword hanging in its scabbard over the fireplace mantel, and brandish it at them.

One daughter, Sara Finch, had packed a footlocker at the age of fifty and moved to the Bowery in New York City, where she made the acquaintance of a sailor at a tavern. She lived with him a year until he found a desirable berth on a ship bound for South America. She then returned to her father’s house and proceeded to write love letters, signing the sailor’s name to them and mailing them to herself. She greeted their arrival with cries of joy if her father was nearby.

My father recalled that another Finch sister had eloped with a Hungarian Jew. They had a child and named him Douglas, a family name. He grew up and became an actor, Douglas Fairbanks. He was my father’s first cousin.

When Grandfather Fox returned from Germany to the United States, he had been able to find work only as a traveling salesman, a drummer, selling medical supplies, going from town to town lugging a huge black sample case.

My grandmother’s tyrannical father had felt that his daughter had married beneath her when her husband became a traveling salesman, although when he was a philosopher he didn’t consider that she had.

One morning when my grandfather left the family home for a week of peddling in Pennsylvania, my father, then a small boy, hid behind a tree and threw an apple core at him, shouting, “Red! Red!” at his redheaded father. He desperately didn’t want him to go away on still another trip for what must have seemed to him a year.

Shortly after my grandfather’s visit, the minister drove me to Yonkers, to Warburton Avenue, where my Aunt Jessie Fox and my grandparents lived in a tall, narrow wooden house. I looked forward to the visit with curiosity and apprehension.

My aunt had thin freckled hands and a slight hump below her right shoulder, which gave her an air of impending wickedness. It was a result, Daddy said, of an early bout with tuberculosis. She smoked continually. Often, as she spoke, she twisted and twirled her hands about. She was ten years older than her brother, my father, and, like him, had a beautiful voice, but she talked constantly, and it became beautifully monotonous.

She led me through the many rooms of the house. They were either empty or crowded with furniture. In the long living room, on the wall behind a small sofa, hung a gold-framed mirror. It diminished the size of all that it reflected, and showed a scene as tiny and perfect and lifeless as a village inside a spun-sugar Easter egg I had once seen somewhere. When I looked away from it to the real room I was in, I realized how shabby and forlorn the furnishings were.

Someone very old was sitting in a large chair in front of a table at the end of the room. She was wrapped in many scarves and a blanket but had worked one of her arms loose so she could do the crossword puzzle in a newspaper that lay on her lap. From time to time, she raised her head and stared into the distance through thick-glassed spectacles.

“Here’s little Paula, Mother,” Aunt Jessie said.

The old woman made a comment. I’ve forgotten the words, but I recall her voice, soft and cold and small, a sound that might have issued from something that lived on the bottom of the sea.

Later that day, I sat at my aunt’s dressing table letting a necklace of bright glass beads flow from hand to hand. She told me the necklace had come from Venice, a city in Italy that floated upon water.

She spoke about my father’s restlessness when he’d been a boy. She had waked many mornings just before dawn to discover her little brother, unable to sleep through the night, curled up on the floor beneath her bed. On other nights, he slept under his parents’ bed. “Even in winter when it’s so cold?” I asked her, startled by the image of him in a nest of dust and cobwebs. “Even in winter,” she replied.

I noted that day how she spoke of men as “the little fellows,” but when she mentioned my father it was always by his name, Paul. “The little fellows came to repair our plumbing but they didn’t do so well,” she remarked when I told her that the faucet in the bathroom was leaking.

At one point, she recalled an incident that involved her brother and began to smile. When my father was ten or so, he was standing beside her at a window that looked out on the skimpy lawn at the front of the house. It was a summer evening, and she was waiting for a suitor to call. As the young man came into view, walking up the cement path to the porch, Paul, who had not seen him before, made a derisive remark about him.

My aunt had laughed. She was laughing as she told me about it, and had laughed as she had gone to the front door, opened it, and given the young man his “walking papers.” She could no longer remember his name.

My grandmother lived to be 101, kept alive, my father told me some years later, by his sister’s desperate measures. Jessie was like a living bellows, breathing air, day after day, into the ancient woman’s exhausted lungs. When her mother died, Jessie began to slide into a state of senile dementia and was taken off to a local nursing home where, unless restrained, she bit her nurses when they attended her. She was carried out of life one day in a fit of deranged anger. My grandfather had died in his eighties, long before his wife and daughter, from what, I don’t know; but I attributed to him as his last conscious emotion—unjustly, perhaps—relief at leaving behind him his deplorable family.

I drove past the house decades later. Warburton Avenue led to an old scenic drive along the east bank of the Hudson River. The front door was boarded up. It looked abandoned. I wondered who would be so desperate for housing that they would buy it.

A year passed between the long drive to Provincetown and several visits I made to apartments where my parents stayed in New York City, one visit to a rented cabin in the Adirondack Mountains, and a few hours in a restaurant on the Coney Island boardwalk, midday in the spring.

A scene occurred there that displayed the pleasure my mother, Elsie, took in her own mockery. I was sitting at a table with her and my father and several of their acquaintances. A small band was playing popular songs of the day. She turned to me suddenly. Would I go over to the bandstand and request a song called “Blasé?”

I felt excitement at the thought of carrying out her wish, but I was abashed by her smile of amusement and the secret it implied.

I made my way among the tables to the bandleader, who was in the middle of a number. I stood beside the bandstand where the musicians sat in scissorlike wooden chairs, blowing and fiddling on their instruments. At last I caught the eye of the bandleader. My voice to him must have been nearly inaudible. What I said was, “‘Blasé’ for her,” and pointed to the table where my mother was sitting. His sour expression gave way to a startled smile. He waved in her direction and bowed slightly. Everyone was laughing: my parents and their friends, people at tables close enough to the platform to have heard my request, and now the conductor himself. My face blazed. I knew, without understanding what it was, that their laughter was about something ridiculous I had done.

My parents were staying temporarily—their arrangements, as far as I could work out, were permanently temporary—in a small borrowed apartment in New York City. The minister arranged with my father to leave me there for a few hours and then return to take me home.

A large dog lay on the floor, its eyes watchful. I recognized it as the same animal that had attacked the cat in Provincetown a year or so earlier. It got up to sniff my shoes. My father filled in the silence with his voice. I wasn’t listening to him. Where was my mother?

Suddenly she appeared in the doorway that led to a second room. I saw an unmade bed behind her. She pressed one hand against the doorframe. The other was holding a drink. My father’s tone changed; his voice was barely above a whisper. “Puppy…puppy…puppy,” he called her softly, as though he feared, but hoped, to wake her. She stared at me, her eyes like embers.

All at once she flung the glass and its contents in my direction. Water and pieces of ice slid down my arms and over my dress. The dog crouched at my feet. My father was in the doorway, holding my mother tight in his arms. Then he took me away from the apartment.

At some hour he must have returned with me. Perhaps we waited for the minister outside the front door.

For years I assumed responsibility for all that happened in my life, even for events over which I had not the slightest control. It was not out of generosity of mind or spirit that I did so. It was a hopeless wish that I would discover why my birth and my existence were so calamitous for my mother.

A few months later Uncle Elwood took me to the city again to visit my parents. This time they were staying in a hotel owned by a family they were acquainted with, whose wealth included vast land tracts on the west side of the Hudson River, just north of the Palisades, as my father explained to me. I was to stay overnight, and for that purpose the rich family provided a room for me across the corridor from Paul and Elsie.

The idea of spending so much time with them filled me with alarm. But the visit began cheerfully, though a malaise gripped me as soon as I saw them together in the hotel room. I mistook the feeling for excitement.

Humorously, my parents played with the idea that I should marry the son of the hotel owners, a boy only a year or so older than I was, I guessed. They would arrange the marriage first thing in the morning, they promised, both smiling broadly. I strained to match their mood. It would be like the marriages of children in India. I had seen such children in an issue of the National Geographic. They looked so little. They wore bands of jewels across their brows and large brilliantly colored flowers behind their ears.

Evening approached. The dark, like ink, filled up the airshaft of their room on the fourteenth floor. My father asked me what I would like for supper; he would order it from room service. My experience was only with the minister’s cooking. “Lamb chop and peas,” I said, partially aware that this was a special occasion: hotel rooms, Paul and Elsie, so tall, so slender, both, a marriage planned for the future so I would be able to live in this room for years, the excitement of great things about to happen. We hardly ever had lamb chops at Uncle Elwood’s house, though we often had little canned peas. When the tray was delivered by a waiter, I looked at it and saw I had forgotten something.

“There’s no milk,” I observed.

At once, my father carried the tray to the window, opened it, and dropped the tray into the airshaft.

Moments later, as I stood there stunned by what my father had done—nothing Elsie did ever surprised me—I heard the tray crash. Through tight lips, my father said mildly, “Okay, pal. Since it wasn’t to your pleasure…” My mother, behind the half-closed door of the bathroom, where she had gone at the very moment he walked to the window, exclaimed “Paul!” in a muffled voice, as though she spoke through a towel.

Again, as in the episode of the trunk in Provincetown, I was profoundly embarrassed, as though I were implicated in my father’s act. But nearly as painful was the gnawing hunger I suddenly felt for that lamb chop lying fourteen stories below.

As the two of them were leaving for the evening, for whatever entertainment they anticipated, there was a loud knocking at the door. My father opened it to a laughing young man, possessed by what was to me an inexplicable merriment. “Foxes!” he cried, clapping his hands, fluttering and capering, calling out praises to my mother. “Your costume, darling!” My father murmured, “Dick is to keep an eye on you,” and at that the young man spotted me and held out his hand, which I took. “Come along, Paula,” he called, even though I was standing next to him.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/paula-fox/borrowed-finery/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Paula Fox

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Биографии и мемуары

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 171.97 ₽

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: One of the most powerful memoirs of recent times.Shortly after Paula Fox’s birth in 1923, her hard-drinking Hollywood screenwriter father and her glamorous mother left her in a Manhattan orphanage. Rescued by her grandmother, she was passed from hand to hand, the kindness of strangers interrupted by brief and disturbing reunions with her darkly enchanting parents. In New York, Paula lives with her Spanish grandmother; in Cuba, she wanders about freely on a sugarcane plantation owned by a wealthy relative; in California she finds herself cast away on the dismal margins of Hollywood where famous actors and literary celebrities – John Wayne, Buster Keaton, Orson Welles – glitteringly appear and then fade away.A moving and unusual portrait of a life adrift. Paula Fox gives us an unforgettable appraisal of just how much – and how little – a child requires to survive.