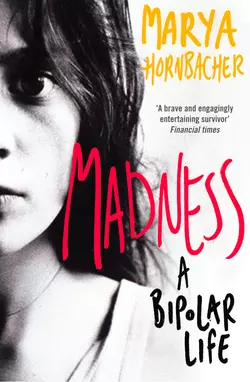

Madness: A Bipolar Life

Marya Hornbacher

A searing, unflinching and deeply moving account of Marya Hornbacher’s personal experience of living with bipolar disorder.From the age of six, Marya Hornbacher knew that something was terribly wrong with her, manifesting itself in anorexia and bulimia which she documented in her bestselling memoir ‘Wasted’. But it was only eighteen years later that she learned the true underlying reason for her distress: bipolar disorder.In this new, equally raw and frank account, Marya Hornbacher tells the story of her ongoing battle with this most pervasive and devastating of mental illnesses; how, as she puts it, ‘it crept over me like a vine, sending out tentative shoots in my childhood, taking deeper root in my adolescence, growing stronger in my early adulthood, eventually covering my body and face until I was unrecognizable, trapped, immobilized’. She recounts the soaring highs and obliterating lows of her condition; the savage moodswings and impossible strains it placed on her relationships; the physical danger it has occasionally put her in; the endless cycle of illness and recovery. She also tackles the paradoxical aspects of bipolar disorder – how it has been the drive behind some of her most creative work – and the reality of a life lived in limbo, ‘caught between the world of the mad and the world of the sane’.Yet for all the torment it documents, this is a book about survival, about living day to day with bipolar disorder – the constant round of therapy and medication – and managing it. As well as her own highly personal story, the book includes interviews with family, spouses and friends of sufferers, the people who help their loved ones carry on. Visceral and inspiring, lyrical and sometimes even funny, ‘Madness’ will take its place alongside other classics of the genre such as ‘An Unquiet Mind’ and ‘Girl, Interrupted’.

Madness

a bipolar life

marya

hornbacher

Copyright (#ulink_f8447acc-1cc3-5c4c-9529-935b64e05e36)

HarperPress

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street, London SE1 9GF

www.harperperennial.co.uk (http://www.harperperennial.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by Fourth Estate in 2008

Copyright © Marya Hornbacher 2008, 2009

PS Section copyright © Hannah Harper 2009, except ‘Lives Too Often Kept Dark’ by Marya Hornbacher © Marya Hornbacher 2009

PS™ is a trademark of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

Marya Hornbacher asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780007250646

Ebook Edition © MARCH 2015 ISBN 9780007380367

Version: 2015-03-26

CONTENTS

Cover (#ucef0b98d-711b-59c3-a20f-2b5a1bef2931)

Title Page (#ud8928705-a2d9-512c-a158-237ede53cd2e)

Copyright (#ud1730cc9-5e83-5f0a-a480-20443ce9bce9)

Prologue (#u1f4006c1-23f0-5de6-90a7-5d65c9c71f53)

Part I (#u7b3a06ce-ee74-529b-b337-46abdb242d48)

The Goatman (#ua728963f-f548-5fdd-9f51-ac76a67134c8)

What They Know (#u72df9ec4-31ed-50ad-ad0f-0a22f6b043b8)

Depression (#u54482077-ca8e-5f3d-8dac-63cdc962eeae)

Prayer (#u798fdfd7-1583-53de-9439-3ee1b763ac25)

Food (#u23e241ae-c313-555b-aeee-7a53fe6c22c7)

The Booze under the Stove (#uf25cbd6b-f785-5ee6-b54a-0bfa4f921f9d)

Meltdown (#uaf5a2b1a-0fb2-52e5-9851-e056a2c860ca)

Escapes (#uede4e9c3-1f49-5636-af7d-787ff9f39eda)

Minneapolis (#u5507ecbf-70b7-5013-ab48-428e423f746a)

California (#uc35383ea-50b7-562f-821a-26bfc213767b)

Minneapolis (#u7409e791-3c2f-54c1-bb8b-9029320348df)

Washington, D.C. (#u1c9def12-739f-5862-94e9-d0cefe8cdf0f)

Full Onset (#ub10d86d7-19e8-5f96-b950-9022a8250d20)

Part II (#ua50f43b6-d78b-5482-a34b-447c920b446a)

The New Life (#ud8ba9832-7ec1-55cc-ba99-7b6e10595dd3)

The Diagnosis (#ub91697c7-a8f0-510c-ad33-f9bbf0eabab0)

The Break (#ue04851e4-4995-50b9-af88-746fba363193)

Unit 47 (#u1bc63e84-0a6e-5d85-b12d-48869bb37a34)

Tour (#litres_trial_promo)

Hypomania (#litres_trial_promo)

Jeremy (#litres_trial_promo)

Therapy (#litres_trial_promo)

Losing It (#litres_trial_promo)

Crazy Sean (#litres_trial_promo)

Oregon (#litres_trial_promo)

Day Treatment (#litres_trial_promo)

Attic, Basement (#litres_trial_promo)

Valentine’s Day (#litres_trial_promo)

Coming to Life (#litres_trial_promo)

Jeff (#litres_trial_promo)

The Good Life (#litres_trial_promo)

The Magazine (#litres_trial_promo)

Part III (#litres_trial_promo)

The Missing Years (#litres_trial_promo)

Hospitalization #1 (#litres_trial_promo)

Hospitalization #2 (#litres_trial_promo)

Hospitalization #3 (#litres_trial_promo)

Hospitalization #4 (#litres_trial_promo)

Hospitalization #5 (#litres_trial_promo)

Hospitalization #6 (#litres_trial_promo)

Hospitalization #7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Release (#litres_trial_promo)

Part IV (#litres_trial_promo)

Fall 2006 (#litres_trial_promo)

Winter 2006 (#litres_trial_promo)

Spring 2007 (#litres_trial_promo)

Summer 2007 (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Bipolar Facts (#litres_trial_promo)

Useful Websites (#litres_trial_promo)

Useful Contacts (#litres_trial_promo)

Research Resources (#litres_trial_promo)

Bibliography (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

P.S. Ideas, interviews & features … (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Q A with Marya Hornbacher (#litres_trial_promo)

Life at a Glance (#litres_trial_promo)

Top Ten Writers of All Time (#litres_trial_promo)

Top Ten Musical Artists of All Time (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Book (#litres_trial_promo)

Lives Too Often Kept Dark (#litres_trial_promo)

A Writers Life (#litres_trial_promo)

Read On (#litres_trial_promo)

Have You Read? (#litres_trial_promo)

If You Loved This (#litres_trial_promo)

Find Out More (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Praise (#litres_trial_promo)

By the Same Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PROLOGUE (#ulink_f0b517d7-540d-5ec7-b2e6-dd78a5db3b36)

The Cut

November 5, 1994

I am numb. I am in the bathroom of my apartment in Minneapolis, twenty years old, drunk, and out of my mind. I am cutting patterns in my arm, a leaf and a snake. There is one dangling light, a bare bulb with a filthy string that twitches in the breeze coming through the open window. I look out on an alley and the brick buildings next door, all covered with soot. Across the way a woman sits on her sagging flowered couch in her slip and slippers, watching TV, laughing along with the laugh track, and I stop to sop up the blood with a rag. The blood is making a mess on the floor (note to self: mop floor) while a raccoon clangs the lid of a dumpster down below. Time hiccups; it is either later or sooner, I can’t tell which. I study my handiwork. Blood runs down my arm, wrapping around my wrists and dripping off my fingers onto the dirty white tile floor.

I have been cutting for months. It stills the racing thoughts, relieves the pressure of the madness that has been crushing my mind, vise-like, for nearly my entire life, but even more so in the recent days. The past few years have seen me in ever-increasing flights and falls of mood, my mind at first lit up with flashes of color, currents of electric insight, sudden elation, and then flooded with black and bloody thoughts that throw me face-down onto my living room floor, a swelling despair pressing outward from the center of my chest, threatening to shatter my ribs. I have ridden these moods since I was a child, the clatter of the roller coaster roaring in my ears while I clung to the sides of my little car. But now, at the edge of adulthood, the madness has entered me for real. The thing I have feared and railed against all my life—the total loss of control over my mind—has set in, and I have no way to fight it anymore.

I split my artery.

Wait: first there must have been a thought, a decision to do it, a sequence of events, a logic. What was it? I glimpse the bone, and then blood sprays all over the walls. I am sinking; but I didn’t mean to; I was only checking; I’m crawling along the floor in jerks and lurches, balanced on my right elbow, holding out my left arm, the cut one. I slide on my belly toward the phone in my bedroom; time has stopped; time is racing; the cat nudges my nose and paws at me, mewling. I knock the phone off the hook with my right hand and tip my head over to hold my ear to it. The sound of someone’s voice—I am surprised at her urgency—Do you have a towel—wrap it tight—hold it up—someone’s on their way—Suddenly the door breaks in and there is a flurry of men, dark shadows, all around me. I drop the phone and give in to the tide and feel myself begin to drown. Their mouths move underwater, their voices glubbing up, Is there a pulse? and metal doors clang shut and I swim through space, the siren wailing farther and farther away.

I am watching neon lights flash past above my head. I am lying on my back. There is a quick, sharp, repetitive sound somewhere: wheels clicking across a floor. I am in motion. I am being propelled. The lights flash in my eyes like strobe. The place I am in is bright. I cannot move. I am sinking. The bed is swallowing me. Wait, this is not a bed; there are bars. We are racing along. There are people on either side of me, pushing the cage. They’re running. What’s the hurry? My left arm feels funny, heavy. There is a stunning pain shooting through it, like lightning, flashing from my hand to my shoulder. It seems to branch out from there, shooting electricity all through my body. I try to lift my arm but it weighs a thousand pounds. I try to lift my head to look at it, to look around, to see where I am, but I am unable to. My head, too, is heavy as lead. From the corner of my eye, I see people watching me fly by.

I am in shock. I heard them say it when they found me. She’s in shock, one said to the other. Who are they? They broke down the door. Well, are they going to pay for it? I am indignant. I black out.

I come to. I am wearing my new white sweater. I regret that it is stained dark red. What a waste of money. We have stopped moving. There are people standing around, peering down at me. They look like a thicket of trees and I am lying immobile on the forest floor. When did it happen? What did you use? they demand, their voices very far away. I don’t remember—everyone calm down, I’ll just go home—can I go home? I feel a little sick—I vomit into the thing they hold out for me to vomit into. I’m so sorry, I say, it was an accident. Please, I think I’ll go home. Where are my shoes?

Am I saying any of this? No one stops. They bustle. I must be in a hospital; that is what people do in a hospital, they bustle. For hospital people, they are being very loud. There is shouting. The bustling is unusually hurried. What’s the rush, people? My arm is killing me, as it were, yuk yuk, though I can’t really feel it so much, am more just aware that it is there; or perhaps I am merely aware that it was there, and now I am aware only of the arm-shaped heaviness where it used to be. Have they taken my arm? Well, that’s all right. Never liked it anyway, yuk yuk yuk.

No one is getting my jokes.

I realize I am screaming and stop immediately, feeling embarrassed at my behavior. I have to be careful. They will think I am crazy.

I come to and black out. I come to and black out. This lasts forever, or it takes less than a minute, a second, a millisecond; it takes so little time that it does not happen at all; after all, how would I be conscious of losing consciousness? Is that, really, what it means to lose your mind? Well, then, I don’t lose my mind very often after all. My arm hurts like a motherfucker. I object. I turn my head to the person whose face is closest to me to tell him I object, but suddenly he is all hands, and there is an enormous gaping red thing where my arm used to be. It is bloody, it looks like a raw steak, it looks like the word flesh, the word itself, in German fleish, and the Bastard of Hands has one hand wrapped around my forearm, his fingers and thumbs on either side of the gaping red thing, pressing it together, and he is sticking a needle into the inside part of the thing—Quiet down! Someone hold her down, for chrissakes—and he stabs the inside of the thing again and again and I hear someone screaming, possibly me. It does not hurt, per se, but it startles me, the gleaming slender needle sinking into the raw flesh. I realize I am a steak. They are carving me up to serve me. They will serve me on a silver-plated platter. The man’s hands are enormous, and now the hands are sewing the cut flesh, how absurd! Can’t they just glue it together? What a fuss over nothing—Oh, for God’s sake! I yell (perhaps, or maybe only think), now I remember, and I scream (I’m pretty sure I really do), Can you believe I did it? What a fucking idiot! I didn’t mean to! I plead with them to understand this, I was only cutting a little, didn’t mean to do it, sorry to make such a mess, look at the blood! And my sweater! I black out and come to and black out again. You’re in shock. Can you hear me? Can you hear me, Maria? She’s completely out of it, one says to the other. They tower like giants. They can’t pronounce my name. It’s MAR-ya, I say, stressing the first syllable. Yes, dear. It is, I say, it really is. Yes, dear, I know. I’m sureit is. Just rest. Fuming, I rest. How can they save my life if they don’t even know how to say my name? They will save someone else’s life instead! A woman named Maria! Why, I suddenly think, should they have to save my life—oh, for God’s sake! I remember again. I’ve gone and actually done it! Moron! How on earth will I explain this? The pair of hands has sewn the inside flesh together and is beginning another row on top of it. One row won’t do? Stupid, says the Bastard of Hands. I look at him, shaking his head, disgusted, stitching quickly. So damn stupid.

I want to say again that I didn’t mean it so he will not think I am stupid. I watch blood drip from a bag above my head into a thin tube that leads, I think, to me. I black out. I come to. There is a giant belly in front of me. It touches the edge of the bed. I follow the belly up the body to a very pretty face. Aha! Pregnant! Now I understand. However, why is there a pregnant woman standing next to me? Where is the hand man? Do you think you need to be in the psych ward? God, no! I laugh at the very idea, wanting very badly to seem sane. I prop myself up, forgetting about the arm, and collapse back on it, screaming in pain. Note to self: don’t use left arm. Why don’t you think you need to be in the psych ward? she asks. I didn’t mean to! I cry. It was a total accident, I was making dinner, accidentally the knife slipped, not to worry, I wasn’t attempting (I cannot say the word) (there is a hollow between words, which I fill with) (nicer, safer words). I am incredibly dizzy and I wish she would go away so I could go home—who lets a woman who’s just sliced her arm in half go home? Can you contract for safety? the pregnant psychiatrist asks. Who knew psychiatrists got pregnant? I can, I say, very earnest. You can agree that you will not hurt yourself again if you go home? Absolutely, I say. After all, I joke, I can’t very well cut open the other arm—this one hurts too much! I laugh hysterically, nearly falling off the bed. She doesn’t think this is funny. She has no sense of humor.

She lets me go home. Hospital policy is to impose the least level of restriction possible. If they think you can keep yourself safe, if they can keep one more bed open in the psych ward, they let you go home. And I’m very convincing. I contract for safety, swearing I won’t cut myself up again. I call a cab and climb into it, dizzy, my arm wrapped in thick layers of bandages. I return to a bloody mess, and as dawn fills the room, I tell myself I’ll clean it up in the morning.

I HAVE BEEN in and out of psychiatric institutions and hospitals since I was sixteen. At first the diagnosis was an eating disorder—years spent in a nightmare cycle of starving, bingeing, and purging, a cycle that finally got so bad it nearly killed me—but I’ve been improving for over a year, and it’s all cleared up (brush off hands). They think I’m a little depressed—that’s the assumption they make for anyone with an eating disorder—so they give me Prozac, new on the market now, thought to cure all mental ills, prescribed like candy to any and all. Because I’m not, in fact, depressed, Prozac makes me utterly manic and numb—one of the reasons I slice my arm open in the first place is that I’m coked to the gills on something utterly wrong for what I have.

I am probably in the grip of a mixed episode. During manic episodes or mixed episodes—which are episodes where both the despair of depression and the insane agitation and impulsivity of mania are present at the same time, resulting in a state of rabid, uncontrollable energy coupled with racing, horrible thoughts—people are sometimes led to kill themselves just to still the thoughts. This energy may be absent in the deepest of depressions, whether bipolar or pure depression; the irony is that as people appear to improve, they often have a higher risk of suicide, because now they have the energy to carry out suicide plans. Actually, an alarming number of bipolar suicides are unintentional. Mania triggers wildly impulsive behaviors, powerful urges to push oneself to the utmost, to go to often dangerous extremes—like driving a hundred miles an hour, bingeing on drugs and alcohol, jumping out of windows, cutting, and others. These extreme behaviors lead, often enough, to accidental death.

Who knows, really, what leads to my sudden, uncontrollable desire to cut myself? I don’t know. Is the suicide attempt accidental or deliberate? It certainly isn’t planned. Manic, made further manic by the wrong meds, I simply do it, unaware in the instant that there will be any consequence at all. I watch my right hand put the razor in my left arm. Death is not on my mind.

No one even thinks bipolar—not me, not any of the many doctors, therapists, psychiatrists, and counselors I’ve seen over the years—because no one knows enough. Later, this will seem almost incredible, given what a glaring case of the disorder I actually have and have had nearly all my life. But how could they know back then? With so little knowledge about bipolar disorder, or really about mental illness at all, no one knows what to look for, no one knows what they’re looking at when they’re looking at me. They, and I, and everyone else think I’m just a disaster, a screwup, a mess. On the phone, my grandfather demands, “So, have you got your head screwed on right yet?” Yuk yuk yuk, funny man, raging drunk. But you can’t blame him for the question. It’s the one everyone’s been asking since I was a kid. Surely she’ll grow out of it, they think.

I grew into it. It grew into me. It and I blurred at the edges, became one amorphous, seeping, crawling thing.

Part I (#ulink_1836f20c-a2a7-548d-a2c3-12e063915513)

The Goatman (#ulink_9cee5356-64f4-5d65-9c32-a348a2adcf1c)

1978

I will not go to sleep. I won’t. My parents, who are always going to bed, tell me that I can stay up if I want, but for God’s sake, don’t come out of my room. I am four years old and I like to stay up all night. I sing my songs, very quietly. I keep watch. Nothing can get me if I am awake.

I sleep during the day like a bat with the blinds closed, and then they come home. I hear them open the door, and I fling on the lights and gallop through the house shrieking to wake the dead all evening, all night. Let’s have a play! I shout. Let’s have a ballet! A reading! A race! Don’t tell me what to do, get away from me, I hate you, you’re never any fun, you never let me do anything, I want to go to the opera! I want opera glasses! I’m going to be an explorer! I don’t care if I track mud all over the house, let’s get another dog! I want an Irish setter, I want a camel! I want an Easter dress! I’m going ice-skating! Right now, yes! Where are the car keys? Of course I can drive! Fine, go to bed! See if I care!

And I slam into my room, dive onto the bed, kick and scream, get bored, read a book, shouting at the top of my lungs, “I don’t care,” says Pierre! And the lion says, “Then I will eat you, if Imay.” “I don’t care, says Pierre!” It is my favorite Maurice Sendak book. I jabber to my imaginary friends Susie and Sackie and Savvy and Cindy, who tell me secrets and stay with me all night while I am keeping watch, while I am guarding the castle, and there are horrible creatures waiting to kill me so I talk to myself all night, writing a play and acting it out with a thousand little porcelain figures that I dust every day, twice a day, I must keep things neat, in their magic positions, or something terrible will happen. The shah of Iran, who is under my bed, will leap out and carry me away under his arm.

I have to get dressed. So what if it’s black as pitch outside. I go to the closet, I take out a jumper and a white shirt, and from the dresser I get white socks and white underwear and a white undershirt, and I get my favorite saddle shoes, and I suit up completely. I must be very quiet or my parents will hear. I tie my shoes in double knots so I won’t fall out of them. I get on my hands and knees and crawl all over the room, smoothing out the carpet. Finally I make myself stop. I lie down in the center of the floor, facing the door in case of emergency. I cross my ankles and fold my hands across my middle. I close my eyes. I fall asleep, or die.

“MOM,” I WHISPER loudly, pushing on her shoulder. It’s dark, I’m in my parents’ bedroom, a ghost in my white nightie. “Mom,” I say again, shaking her. I bounce up and down on my toes and lean over her, my mouth near her ear. “Mom, I have to tell you something.”

“What is it?” she mumbles, opening one eye.

“The goatman,” I whisper, agitated. “He’s in my room. He came while I was sleeping. You have to make him leave. I can’t sleep. Will you read to me?” I hop about, crashing into the nightstand. “Can we make a cake? I want to make a cake, I can’t go to school tomorrow, I’m scared of Teacher Jackie, she yells at us, she doesn’t like me, Mom, the goatman, do you have to go to work tomorrow? Will you read to me?”

“Marya, it’s the middle of the night,” she says, hoisting herself up with her elbow. Next to her, the mountain of my father snores. “Can we read tomorrow?”

“I can’t go back in there!” I shriek, running around in a tiny circle. “The goatman will get me! We could make cookies instead! I want to buy a horse, a gray one! And I want to go to the beach and collect seashells, can’t we go to the beach, I promise I’ll sleep—”

My mother swings her legs off the edge of the bed and holds me by the shoulders. “Honey, can you slow down? Just slow down.”

Out of breath, I stand there, my head spinning.

“What did you want to tell me?” she asks. “One thing. Tell me the most important thing you want to tell me.”

“The goatman,” I say, and burst into tears. “But Mom, I can’t—”

“Shhh,” she says, picking me up. She carries me down the hall. This is how she fixes it. She holds me very tight and things slow down a little. But I’m too upset. I set my chin on her shoulder and sob and babble. Everyone’s going to leave, you’ll forget to come get me, I’ll get lost, I’ll get stuck in the grocery store and they’ll lock me in. What if there are snakes in my bedroom? Why won’t the goatman go away? What if it isn’t perfect? What if it’s scary? What if you and Daddy die? Who will take care of me? What if you give me away? I don’t want you to give me away, I want to be a policeman, why do policemen wear hats—

“Marya, hush. It’s all right. Everything’s going to be all right.”

I want to see Grandma, let’s go see Grandma, I want to go outside and play in the yard, why can’t I play in the yard when it’s dark, I want to look at the moon—

We pace up and down the hall. I get more and more agitated, swinging moment by moment from terror to elation to utter despair, until finally I wiggle my way free and start to run. I race around the house, my mother trailing me, until I stumble on my nightgown and sprawl out on the floor, sobbing, beating my fists on the ground. “I’m here,” she says. “Honey, I’m here.”

I snuffle and drag a hiccupping breath and heave a sigh. She is here. She is right here. She picks me up. She carries me into the bathroom and turns on the bathtub. While it runs, I squirm on her lap, kicking my legs, shrieking, laughing, crying, I can’t ever go back in my room, the goatman, I want to have a party, when is it Christmas, I want to live in a tree house, what if I fall in the ocean and drown, where do I go when I die—

She pulls my nightgown over my head and sets me in the tub. I am suddenly quiet. Water makes it better. In the water, I am safe. She kneels next to me where I sit, only my head sticking out of the water. She tells me a story. Things are slowing down. I am contained. I bob in the water, warm, enclosed. My limbs float. The noise and racing of my thoughts wind down until they yawn in my head as if they are in slow motion. My head is filled with white cotton, and I hear a low humming, and my skull is heavy. I am aware only of the water and my mother’s voice.

Back in bed, she wraps me tight in my quilt, my arms and legs and feet and hands all covered, kept in so they won’t fly off. The goatman has gone away for the night. She sits on the edge of my bed, smoothing my hair. I am wrapped up like a package. I am a caterpillar in my cocoon. I am an egg.

She stays with me until, near dawn, I fall asleep.

What They Know (#ulink_de6e8772-7579-55a7-8427-d11dfc4397b3)

1979

They know I am different. They say that I live in my head. They are just being kind. I’m crazy. The other kids say it, twirl their fingers next to their heads, Cuckoo! Cuckoo! they say, and I laugh with them, and roll my eyes to imitate a crazy person, and fling my arms and legs around to show them that I get the joke, I’m in on it, I’m not really crazy at all. They do it after one of my outbursts at school or in daycare, when I’ve been running around like a maniac, laughing like crazy, or while I get lost in my words, my mouth running off ahead of me, spilling the wild, lit-up stories that race through my head, or when I burst out in raging fits that end with me sobbing hysterically and beating my fists on my head or my desk or my knees. Then I look up suddenly, and everyone’s staring. And I brighten up, laugh my happiest laugh, to show them I was just kidding, I’m really not like that, and everyone laughs along.

I AM LYING on the bed. I am listening to my parents scream at each other in the other room. That’s what they do. They scream or throw things or both. You son of a bitch! [crash]. You’re trying to ruin my life! [crash, shatter, crash]. When they are not screaming, we are all cozy and happy and laughing, the little bear family, we love each other, we have the all-a-buddy hug. It’s hard to tell which is going to come next. Between the screaming and the crazies, it is very loud in my head.

And so I am feeling numb. It’s a curious feeling, and I get it all the time. My attention to the world around me disappears, and something starts to hum inside my head. Far off, voices try to bump up against me, but I repel them. My ears fill up with water and I focus on the humming in my head.

I am inside my skull. It is a little cave, and I curl up inside it. Below it, my body hovers, unattached. I have that feeling of falling, and I imagine my soul is being pulled upward, and I close my eyes and let go.

My feet are flying. I hate it when my feet are flying. I sit up and grab them with both hands. It’s dark, and I stare at the little line of light that sneaks in under the door.

The light begins to move. It begins to pulse and blur. I try to make it stop. I scowl and stare at it. My heart beats faster. I am frozen in my bed, gripping my feet. The light has crawled across the floor. It’s headed for the bed. I want it to hold still, so I press my brain against it, expecting it to stop, but it doesn’t. The line crosses the purple carpet. I want to scream. I open my mouth and hear myself say something, but I don’t know what it is or who said it. The little man in my mind said it, I decide, suddenly aware that there is a little man in my mind.

The line is crawling up the side of the bed. I tell it to go away. Holding my feet, I scootch back toward the wall. My brain is feeling the pressure. I let go of my feet and cover my ears, pressing in to calm my mind. The line crests the edge of the bed and starts across the flowered quilt. I throw myself off the bed. I watch the line turn toward me, slide off the bed, follow me into the corner of my room.

I want to go under the bed but I know it will follow me. I jump up on the bed, jump down, run into the closet and out again, the humming in my head is excruciatingly loud. The light is going to hurt me. I can’t escape it. It catches up with me, wraps around me, grips my body. I am paralyzed, I can’t scream. So I close my eyes and feel it come up my spine and creep into my brain. I watch it explode like the sun.

I drift off into my head. I have visions of the goatman, with his horrible hooves. He comes to kill me every night. They say it is a nightmare. But he is real. When he comes, I feel his fur.

I don’t come out of my room for days. I tell them I’m sick, and pull the blinds against the light. Even the glow of the moon is too piercing. The world outside presses in at the walls, trying to reach me, trying to eat me alive. I must stay here in bed, in the hollow of my sheets, trying to block the racing, maniac thoughts.

I turn over and burrow into the bed headfirst.

I HAVE THESE crazy spells sometimes. Often. More and more. But I never tell. I laugh and pretend I am a real girl, not a fake one, a figment of my own imagination, a mistake. I never let on, or they will know that I am crazy for sure, and they will send me away.

This being the 1970s, the idea of a child with bipolar is unheard of, and it’s still controversial today. No psychiatrist would have diagnosed it then—they didn’t know it was possible. And so children with bipolar were seen as wild, troubled, out of control—but not in the grips of a serious illness.

My father is having one of his rages. He screams and sobs, lurching after me, trying to grab me and pick me up, keep me from going away with my mother, but I make myself small and hide behind her legs. We are trying to leave for my grandmother’s house. We are taking a train. I have a small plaid suitcase. I come around and stand suspended between my parents, looking back and forth at each one. My mother is calm and mean. The calmer she gets, the more I know she is angry and hates him. She hisses, Jay, for Christ’s sake, stop it. Stop it. You’re crazy, stop screaming, calm down, we’re leaving, you can’t stop us. My father is out of control, yelling, coming at my mother, grabbing at her clothes as she tries to move away from him. Don’t leave me, he cries out as if he’s being tortured, choking on his words, don’t leave me, I can’t live without you, you are the reason I even bother to stay alive, without you I’m nothing. His face is twisted and red and wet from tears. He throws himself on the floor and curls up and cries and screams. I go over to him and pat him on the head. He grabs me and clutches me in his arms and I get scared and try to push away from him but I’m not strong enough. I finally get free and he stands up again, and I stand between them, my head at hip level, trying to push them apart. He kneels and grabs my arms, Baby, I love you, do you love me? Say you love me—and I pat his wet cheeks and say I love him, wanting to get away from him and his rages and black sadness and his lying-on-the-couch-crying days when I get home from preschool, and his sucking need, and I close my eyes and scream at the top of my lungs and tell them both to stop it.

My father calms down and takes us to the train station, but halfway there he starts up again and we nearly crash the car. We leave him standing on the platform, sobbing.

“Why does he get like that?” I ask my mother. I sit in the window seat swinging my legs, watching the trees go by, listening to the clatter of the wheels. I look at my mother. She stares straight ahead.

“I don’t know,” she says. I picture my father back at home, walking through the empty house to the couch, lying down on his side, staring out the window like he does some afternoons, even though I tell him over and over I love him. Over and over, I tell him I love him and that everything will be okay. He never believes me. I can never make him well.

CRAZY IS NOTHING out of the ordinary in my family. It’s what we are, part of the family identity, sort of a running joke—the crazy things somebody did, the great-grandfather who took off with the circus from time to time, the uncle who painted the horse, Uncle Frank in general, my father, me. In the 1970s, psychiatry knows very little about bipolar disorder. It wasn’t even called that until the 1980s, and the term didn’t catch on for another several years. Most people with bipolar were misdiagnosed with schizophrenia in the 1970s (in the 1990s, most bipolar people were misdiagnosed with unipolar depression). We didn’t talk about “mental illness.” The adults knew Uncle Joe had manic depression, but they didn’t mind or worry about it—just one more funny thing about us all, a little bit of crazy, fodder for a good story.

This is my favorite one: Uncle Joe used to spend a fair amount of time in the loony bin. My family wasn’t bothered by his regular trips to and from “the facility”—they’d shrug and say, There goes Joe, and they’d put him in the car and take him in. One day Uncle Frank (who everybody knows is crazy—my cousins and I hide from him under the bed at Christmas) was driving Uncle Joe to the crazy place. When they got there, Joe asked Frank to drop him off at the door while Frank went and parked the car. Frank didn’t think much of it, and dropped him off.

Joe went inside, smiled at the nurse, and said, “Hi. I’m Frank Hornbacher. I’m here to drop off Joe. He likes to park the car, so I let him do that. He’ll be right in.” The nurse nodded knowingly. The real Frank walked in. The nurse took his arm and guided him away, murmuring the way nurses always do, while Frank hollered in protest, insisting that he was Frank, not Joe. Joe, quite pleased with himself, gave Frank a wave and left.

Depression (#ulink_63fe64a2-4700-5433-8b3d-e6aec71f65c1)

1981

Maybe it begins when I am seven. I’m in bed. It’s too sunny outside, I can’t go out. The blinds are drawn and yet they let in a little light, and the little light pierces my eyes. I turn my face into my pillow. It’s cool and safe in my sheets. My father comes in.

Time to get up, kiddo.

(Silence.)

Kiddo.

(I pull the pillow over my head to block the incessant light.)

Kiddo, are you getting up?

No.

Why not?

I’m skipping today.

What’s the matter with today?

I sigh. I despair of ever getting up again. I cannot move. I will not move. Everything is horrible. I want to go to sleep forever.

I can’t go to school, I say.

Why not?

I bang my head on the mattress and let out a shriek. I sigh and flop onto my back and shade my eyes.

There’s an art project. I burst into tears.

Oh, my father says, unsurprised. Is it complicated?

It’s very complicated, I wail. I can’t do it. I don’t want to do it. So I’m sick. I wipe my nose and let the tears fall into my ears.

Okay, my father says.

I’m staying home.

Okay.

Okay. Okay. Now I will be okay. No crowded classroom, no scissors, no paste, no other kids, no cafeteria lunch, no recess, no wide sky and too much sun.

The world outside swells and presses in at the walls, trying to reach me, trying to eat me alive. I must stay here in the pocket of my sheets, with my blanket and my book. I will not face the world, with its lights and noise, its confusion, the way I lose myself in its crowds. The way I disappear. I am the invisible girl. I am make-believe. I am not really there.

I don’t come out of my room for days. Days bleed into weeks. I lie in bed in the dark.

Prayer (#ulink_726b66d8-fde6-58a8-9794-838140c41e9c)

1983

On my knees. Praying. Pleading. The basement floor is cold beneath my knees. I come here to hide, to hide my prayers. My mother would mock me. God is merely a weakness for people who need to believe. She wouldn’t understand that I am chosen to speak for all the sorrows of the world.

I’m not crazy. God has called me and I have no choice but to answer, or I will be sent to hell. It all depends on me. And so I pray myself to sleep, and pray the second I wake, and pray all day, terrified that God will catch me slacking off and punish me severely.

My knees grow sore and my heart beats a million miles an hour. I panic. I practically pant. My mind spins with the things I am forgetting to pray for, things I have done, there is a light flashing in my brain, like the headlight of a train in the dark, the dark is my mind, which teems with sins, which torment me with their noise. I can hear the sins whisper; are they inside my head or outside my ears? Are they in the basement? Coming from the water heater, the washing machine? God answers at last. You may get up, I hear him say. His voice reverberates against the concrete walls.

Halfway up the stairs, I hear God call me to prayer again. I kneel and pray. He calls me in the kitchen. Calls me in my bedroom. Calls me at school. I raise my hand, hurry into the restroom, kneel on the floor of the stall, the restroom empty and echoing with my rapid breath, echoing with the shrieking, pounding in my head. I pray in class. I pray in the car, after dinner, all night long—hours after silence has settled around the house, my mouth moves with manic prayers.

God watches me, sees my every mistake, every sin. God’s voice booms in my head, now praising me, his chosen one, now spitting at me, sending the snake into my mind. It curls itself around itself, its body pressed against the walls of my skull. I lie in bed, rocking, my head in my hands, the snake flicking its tongue at the backs of my eyeballs. It sinks its teeth into the gray, wet brain. I press my open mouth to the mattress and scream.

Food (#ulink_9a00113d-5040-58ec-8c0e-b88c7b60aec9)

1984

God has left. My mind is spinning. I’m out of control, unable to contain myself. I am propelled forward, toward something drastic. I’m going to hurl myself into anything that will stop the thoughts. Suddenly I find a focus. It’s incredibly intense. I must, I must fill myself to bursting, then rid myself of that fullness. Food. It’s all about food.

My body disgusts me. I stand naked in my bedroom in front of the mirror. I pinch the flesh, the needy, hungry, horrible flesh, the softness that buries the perfect clean bones. I pinch hard; red welts appear on my skin. The body revolts me, its tricks, its betrayals, its lies. I starve and starve, and then it happens—the black hole in my chest yawns open, and suddenly I’m in the kitchen, standing at the counter, stuffing food into my mouth, anything I can find, anything that will fill me up. Food covers my face, my cheeks bulge with it, but I still can’t stop, my hands move back and forth from food to mouth. I hate myself for it. I want to be thin, I want to be bones, I want to eliminate hunger, softness, need.

Every day I come home from fourth grade and try to avoid the kitchen. I sit in my bedroom, clutching the seat of my chair. The empty house echoes its silence around me. I sit, gritting my teeth, and then the hum of compulsion drives me into the kitchen. I eat. Leftovers, frozen dinners, whatever I can stuff in my mouth.

I lean over the toilet with my fingers down my throat. I throw up, body heaving, until I’m spitting up blood. I straighten up. I am empty. Clean. I run my hands over the flat of my stomach, play the xylophone of my ribs. Satisfied, absolved, I open the door, walk calmly down the hall to the kitchen, and do it again.

It’s my secret and my savior. It’s reliable. It saves me from the unpredictable mind, where the thoughts are a cesspool, swirling, eddying with rip tide. When I starve, the sinking, pressing black sadness lifts off me, and I feel weightless, empty, light. No racing thoughts, no need to move, move, move, no reason to hide in the dark. When I throw up, I purge all the fears, the paranoia, the thoughts. The eating disorder gives me comfort. I couldn’t let it go if I tried.

It is what I need so badly, a homemade replacement for what a psychiatrist would prescribe for me if he knew: a mood stabilizer. My eating disorder is the first thing I’ve found that works. It becomes indispensable as soon as it begins. I am calm in starvation, all my apprehensions focused. No need to control my mind—I control my body, so my moods level out. I live in single-minded pursuit of something very specific: thinness, death. I act with intention, discipline. I am free.

My parents wonder where all the food is going. I say I’m a growing girl.

The Booze under the Stove (#ulink_8080fcf0-4205-5946-a1b2-50a4343e04f9)

1985

Nothing is going fast enough. At school, the teachers are talking as if their mouths are full of molasses. Their limbs move in slow motion. Pointing to call on someone, the teacher lifts her arm as if it is filled with wet sand. I swear to God I think I am going insane, it is so slow, while my thoughts whistle past like the wind, so fast I can barely keep up. I turn my mind inward to watch them. They move in electric currents, crackling, spitting, sending out red sparks.

The other students are slow, stupid, asleep. In the hallways, they move like a herd of slugs, wet and shapeless, inching toward the door. I explode out of school, dancing as fast as I can across the playground, whipping in circles around the tetherball pole, dashing off across the yard, trying to shake off this incredible energy, this amazing energy. I’m ten years old and I might as well be on speed.

My parents are on their way out the door. Eat dinner! they call, but I am too fast for them, their voices recede in the distance as I race through the house, bouncing off the walls. I’ve been pleading with them to let me stay home by myself, and so they do, heading off to their meetings or dinners or places unknown. Maybe not a great idea to let a ten-year-old stay home alone, but I’ve twisted their arms, and they’re immersed in work and in their own nightmare marriage, avoiding each other, avoiding the fights, thinking up reasons to be gone. They work compulsively, and when they’re not working they see friends, putting on the face of the happy couple. Everything’s fine. We’re the perfect little family. People tell us that all the time.

And I am home alone with a raw steak on the counter, hopping up and down, my mind jetting about. Time for homework! I reach into my bag and throw my books and papers up in the air, ha ha! Watch this, ladies and gentlemen, the amazing Marya! Look at her go! Can you believe the incredible speed? My homework covers the kitchen floor, and I crawl around picking it up, talking to myself: Hip-hop, my friends, never liked rabbits, must get a tiger, it will sleep in my bed, take it for walks, I need new shoes, fabulous shoes, I will show all of them, hark the herald angels sing! Christmas is smashing! Love it, people, just love it—I hop up, slap my hand to my chest, salute the refrigerator, click my heels, make a sharp turn, and walk stiffly over to the kitchen table, where I whip through the papers, laying them out perfectly in a complex system, the most efficient system, each corner of each page touching the corner, exactly, of the next. Having arranged the papers, I gallop up and down the hallway, slide into the kitchen as if I’m sliding into third, yank open the refrigerator, pull out some mushrooms, chop them up, my knife a blur, toss them into the frying pan, sauté them—but they need a little something. A little zing. I pull open the cupboard beneath the sink, pull out the brandy, splash it in the pan. But now that I think of it, what are all those bottles?

I turn off the burner, bouncing up and down, and open the cupboard again.

Booze.

I pull out a jug of Gallo, stagger underneath its weight. A little wine with dinner, the very thing, don’t you think? I pour it into a giant plastic Minnesota Twins cup and collapse with my mushrooms and tankard of wine at the dining room table.

I get absolutely shitfaced. I am shitfaced and hyper and ten years old. I am having the time of my life.

I lope up and down the hallway, singing Simon and Garfunkel songs, juggling oranges. I do my homework in a flurry of brilliance, total efficiency, the electric grid of my mind snapping and flashing with light. I am in the zone, the perfect balance between manic and drunk, I am mellow, I’m cool, cool as cats. I’ve found the answer, the thing that takes the edge off, smoothes out the madness, sends me sailing, lifts me up and lets me fly.

It’s alchemy, the booze and my brain, another homemade mood stabilizer, and it stabilizes me in a heavenly mood. I am in love with the world, gregarious, full of joy and generosity toward my fellow man. My thoughts fly, but not up and down—they soar forward in a thrilling flight of ideas, heightened sensations, a creative rush, each thought tumbling into the next. It’s even more perfect than eating and throwing up.

My future with alcohol is long and disastrous. But at first, it works wonders for me. No longer low, not yet too high. Just on a roll, energetic, inspired. I truly believe the booze is helping. I’ll believe this, despite all evidence, for years.

Eventually I stagger into bed and, for once, fall asleep.

Meltdown (#ulink_b4c429b6-1cbb-5d8b-927f-dadebda573af)

1988

My moods start to swing up and down almost minute to minute. I take uppers to get even higher and downers to bring myself down. Cocaine, white crosses, Valium, Percocet—I get them from the boys who skulk around the suburban malls hunting jailbait. I’m an easy target, in the market for their drugs and willing to do what they want to get them for free. The boys themselves are a high. They have something I want. They are to be used and discarded. The trick is to catch them and make them want the girl I am pretending to be. Then twist them up with wanting me, watch them squirm like worms on a hook, and throw them away.

I find myself on piles of pillows in their basements, pressed down under their bodies, their lurching breath in my ear. They are heavy, damp, hurried, young, still mostly dressed. I don’t know how I’ve wound up here, and I want it to end, and I repeat to the rhythm of their bodies, You’re a slut, you’re a whore, and I want a bath, want to scrub them off, why does this keep happening? Why don’t I ever say no? There’s a rush when they want me, and they always do, they’re boys, that’s what they want, and once they’ve got me half lying on the couch, each basement, each boy, each time, my brain shuts off, the rush is over, I’m numb, I want to go home. The impulsive tumble into the corner, the racing pressure in my head always ends like this: I hate them, and I hate myself, and I swear I won’t do it again. But I do. And I do. And I do.

And then I am home in my bedroom, blue-flowered wallpaper and stuffed animals on the bed, stashing my baggies of powders and pills. If I hit the perfect balance of drugs, I can trigger the energy that keeps me up all night writing and lets me stay marginally afloat in junior high, accentuating the persona I’ve created as a wild child, a melodramatic rebel—black eyeliner and dyed black hair, torn clothes, a clown and a delinquent, sulking, talking back. In class, I fool everyone into thinking I’m real.

But then I come home after school to the empty, hollow house, wrap into a ball in the corner of the couch, a horrible, clutching, sinking feeling in my chest. Nothing matters, and nothing will ever be all right again. I go into rages at the slightest thing, pitching things around the house, running away in the middle of the night, my feet crunching across the frozen lake. I cling to the cold chainlink fence of the bridge across the freeway and watch the late-night cars flash by, my breath billowing out into the dark in white gusts.

DAY YAWNS OPEN like a cavern in my chest. I lie in the dimness of my room, the blinds shut tight and blankets draped over them. I weigh a million pounds. I can feel my body, its heavy bones, its excess flesh, pressing into the mattress. I’m certain that it sags beneath me, nearly touching the floor. My father bangs on the door again. Breakfast! he calls.

I crawl out of bed and slide out the drawer from the bed stand, turn it over, and untape the baggie of cocaine underneath. Kneeling, I tap lines out onto the stand, lean over, and snort them up with the piece of straw I keep in the bag. I sit back on my knees and close my eyes. There it is: the feeling of glass shards in the brain. I picture the drug shattering, slicing the gray matter into neat chunks. My heart leaps to life as if I’ve been shocked. I open my eyes, lick my fingers and the straw, and put the baggie away, replacing the drawer. I lift off, the roller coaster swinging up, clattering on its tracks, me flying upside down.

Humming, I take a shower and dance into my clothes—a ridiculously short skirt with a hole that exposes even more thigh, black tights, a ripped-up shirt. I pack up my book bag, pull out another baggie, pills this time, from the far corner of the desk drawer. I select a few and put them in my pockets, then spring into the day, a gorgeous day, a good day to be alive. Good morning! I call, sitting down at the table, bouncing my knee at the speed of light.

You’re in a good mood this morning.

I am! I am indeed. I watch my father scramble eggs, and then panic: what am I thinking? I can’t eat that. I leap to my feet. Gotta go! Can’t stay to eat! I punch my father on the arm as I run out the door.

But you need to eat! he calls after me. Get back here! You can’t leave dressed like that!

Bye, I call, setting off down the street, my book bag banging against my leg. The trees are in bloom. The sun is pulsing. I can feel it touching my skin. My skin is alive, crawling. Suddenly I stop. My skin is on fire. I drop my book bag, start rubbing my skin. Get it off! I am dancing around in the middle of the road. There are bugs on my arms, crawling up my neck, crawling on my face and into my hair, Get them off me! Where the hell are they coming from? I fall onto the grass at the side of the road, rolling, trying to get them off. My hair tangles and dirt grinds into my clothes. Finally the bugs are gone. I stand up, smooth my hair, and, much better now, skip down the road to school. It’s so annoying when that happens. But I’m not about to give up the cocaine.

No one knows about the powders, the pills, the water bottle filled with vodka that I keep in my bag. My friends are good girls. I am a tramp. I don’t know why they bother with me. I slouch in my seat in the back of the room, my arms folded, hiding behind my hair. The teachers are idiots. I hate their clothes, their thick, whining Minnesota accents, the small-town smell that clings to them: dust and tuna casserole. This whole town is a bunch of suburban clones, blond, blue-eyed, dressed in tidy matching clothes. Everyone looks the same. Everyone will wind up married, living in a mini-mansion with a sprawling, manicured lawn. There’ll be cute little identical children, and the men will golf and drink and slap each other on the back, old chum, and the women will lunch at the country club and listen to lectures about the deserving poor, the homeless children downtown. They’ll shake their heads with concern and volunteer for the PTA and at the Lutheran church, collect bad art and vote Republican, and hate people like me.

I have to get out of this town.

After lunch, I lean over the toilet in the bathroom stall and throw up. I wipe my mouth, scrub my hands, sniffing them to make sure they don’t smell, wash them again, wipe them dry, look in the mirror, reapply my lipstick, study my face. I brighten my eyes, paste on a smile, and go back out, where the kids teem down the hall.

These are supposed to be the best years of my life.

I fail home economics. I refuse to sew the stuffed flamingo. I question the necessity of learning to make a Jell-O parfait. I blow up an oven—I forget to put the nutmeg in a baked pancake, and when it’s already in the oven, I toss in a handful as an afterthought, setting the entire thing on fire.

I persecute the art teacher. I sit in detention until dark, day after day. When I’m not in detention, I’m running around the newspaper room, putting together what I’m sure is an incendiary tract that’s designed to infuriate everyone who reads it. I am ducking under my desk every half-hour, sucking up the vodka in the water bottle. I am in the library, snorting cocaine off Dante, back in the stacks.

I gallop down the hall at school in a state of absolute glee, dodging in and out between the other kids, shouting, “Hi!” to the people I know as I pass. They laugh. I am hilarious! “You’re crazy!” they call. I am crazy! I’m marvelous! I’m fantastic! The day is fantastic, the world!

“Slow down!” a teacher shouts after me. “No running in the halls!”

I turn and gallop back to him. “Not running!” I shout joyfully. “Galloping, as you can plainly see!” I gallop off.

At the end of the hall, I crash into the wall and bounce back into the circle of my friends who are clustered around my locker. “Isn’t it wonderful?” I cry, flinging my arms wide, picking them up in the air.

“Now what?” Sarah laughs.

“Everything! Absolutely everything! You, today, all of it, wonderful! Amazing! Isn’t it grand to be alive?”

“Weren’t you, like, all freaky and twitchy this morning?” asks Sandra. I pound down the stairs, my legs are faster than speed itself! Tremendous! Spectacular speed, splendid speed, splendiferous speed! I reach the bottom of the stairs and go skidding across the hall. My friends are laughing. I make them happy. I make them forget their horrible homes. I love them, I love them hugely, they are absolutely essential, I would absolutely die without them.

“No!” I shout, “I wasn’t freaky! Well, if I was, I’m certainly not anymore, obviously!” I skip backward ahead of them as we go to lunch. I grab an ice cream sandwich and a greasy mini-pizza. I will be throwing these things up after lunch, obviously, wonderful! I laugh with delight, pleased with myself. “Aha!” I shout, and the people in the line ahead of me crane their necks to look. “Hello, all of you!” I shout, waving, “it’s a beautiful day!” Someone mutters, “She’s crazy,” and I don’t even care, everyone’s entitled to his opinion! That’s the way of the world! We are a world of many opinions, many beliefs! To each his own!

My friends and I move in an amoeba-like cluster over to an open table near the windows and sit down. We munch away on our lunches, chatting, and I chatter like a ventriloquist’s dummy, and all of us laugh, and then I start crying, but right myself quickly. “Enough of that!” I say, wiping my nose, making a grand gesture, “all’s well!” And everyone is relieved, and I have a brilliant idea! I pick up my personal pizza and whip it across the room like a Frisbee! And it lands perfectly in front of Leah Pederson, whom I hate! “Yes!” I shout, triumphant, and the entire lunchroom is laughing, and it’s time to go back to class. I gather my books and my friends and walk calmly down the hall and fling myself into my chair with an enormous sigh.

This time I will be good, I promise myself. This time I won’t make a scene. My heart pounds and I feel another round of hysterical laughter welling up in my chest. I press my face between my hands. I will hold it in. I won’t get detention. I won’t get kicked out of class. I won’t punch Jeff Carver. I won’t turn over any desks, or throw any chairs. I sit up in my chair, open my notebook, click my pen. I stare straight ahead at the teacher who is shuffling papers and handing them out. I will be good. I will, I will, I will.

I SIT IN THE OFFICE of my mother’s shrink. The air circulates slowly in the room. I turn in circles in my swivel chair. To my right, through the window, two floors down, is the parking lot and the sunny, empty afternoon. A small man with square black glasses and gray hair sits kicked back in his leather office chair, watching me.

“What would you like to talk about today?” he asks.

I keep turning in circles. I shrug. “What do you want me to say?”

“What would you like to say?”

I look out the window, count the red cars in the parking lot, then the blue. “I don’t have anything to say.”

We sit in silence. The minutes tick by.

“What are you thinking right now?” he asks.

“Nothing particular.” I turn to face him. He scribbles something on his yellow notepad.

“What are you writing?” I ask.

He gazes at me. “What do you think I’m writing?” he asks.

“I haven’t the faintest idea,” I say.

He scribbles some more.

“Are you supposed to be helping me?” I ask.

“Do you think you need help?”

I turn to face the window again. “I don’t know.” From the corner of my eye, I see him write something down.

“You seem very upset,” he says thoughtfully.

Startled, I look at him. “I’m not.”

He tilts his head to the side. “You’re very angry, aren’t you?” he says.

I laugh. “You’re very perceptive, aren’t you?” I say. He writes it down.

Seven red cars, six blue. The day is still. The branches of the trees don’t move. We sit in silence. I turn circles in my chair.

HE’S A FREUDIAN therapist. When he speaks, he asks me about my mother, about my dreams. I wait for him to tell me what’s wrong with me, why I snap into sudden, violent rages, and shut myself in my room with the dresser backed up against the door for days, and disappear in the middle of the night, and stay in constant trouble at school. Why is it that my moods are all over the goddamn map? How come I’m terrified all the time? He sits silently, watching me, saying nothing, fixing nothing. I give up.

He isn’t looking for eating disorders or drinking or drug use. He isn’t looking for mental illness. In truth, he isn’t looking for much at all. One day he slaps his notebook shut. What’s wrong with me? I ask. Am I crazy? I don’t ask that. I think I know.

His wise and considered opinion is that I’m a very angry little girl.

WORD GETS OUT at school that I’m seeing a psychiatrist. My friends avoid the subject. But other kids whisper about it when I come into the room, kids I don’t like and who don’t like me, the rich kids and the snobs. One of them, egged on by the others—Go on, ask her—comes up to me: Is it true you’re, like, crazy?

No, I say, looking down at my desk.

Then why are you seeing, like, a psychiatrist? Isn’t that for crazy people? Isn’t it? Come on, admit it!

I don’t answer. I scribble so hard in my notebook that my ballpoint tears the page. They laugh. I’m a freak, and everyone knows it, including me.

Then suddenly it hits, a massive, crippling headache. My migraines are coming on nearly every day. I stagger into the nurse’s office and collapse on a cot, curled up in a ball with a pillow over my face. The nurse calls my parents. Back home, I lie in the dark, blinds drawn, rabid thoughts and images zipping through my brain, flashes of blinding color and light. I lie there, shivering and sweating as the pain clenches my skull, nearly paralyzed with fear at the fierce throbbing behind my eyes.

My father opens the door slowly, shuts it quietly behind him. I wince at the deafening noise. The bed sags and he leans over me.

“Here,” he says softly. He lays a wet washcloth over my eyes. “How is it?” he asks.

“Horrible,” I whisper.

“I’m sorry,” he says. He lays a hand on my shoulder. “It will go away soon.”

The bed squeaks as he gets up. The door thunders shut behind him. I press my hands to my head.

They take me to doctor after doctor. No one knows what’s wrong. They give me medication, try biofeedback, tell my parents they don’t know. My parents tiptoe through the house, confused, scared. They don’t know what this onset of violent headaches means. Neither do the doctors. Neither do I.

DEATH WOULD BE SO quiet. I hide in the bathroom with an X-Acto knife, making tiny cuts, crosshatch patterns in my thighs. Nothing deep. It helps relieve the pressure, focus the thoughts. I take a sharp breath and breathe out slow. The blood beads along the cuts. I sop it up with Kleenex, the red spreading out over the tissue. I bleed. I’m alive.

AND THEN it’s dinner and my father’s screaming, and my mother’s cold and icy and cruel, and they’re yelling at me and I’m yelling at them—the crazies rise up in my chest and I run away from the table, the rage welled up so far it presses at the back of my throat. I can taste it. My father chases me, hollering. I shriek and run away. We stand face to face, screaming, his face is twisted and I can feel that my face is twisted and I hate him and his craziness and I hate myself for mine, and my mother gets up, walks down the hall, and slams the bedroom door.

My father and I scream each other down until we are exhausted, completely spent. We stand there panting.

“Say,” my father says brightly, perking up. “Want to play Yahtzee?”

“Sure!” I say. And we sit down to play, laughing and having a wonderful time.

AFTER SCHOOL, I open our front door and step inside. The first thing I see is my father, lying on his side on the couch. Light streams in through the long windows, and it takes my eyes a moment to adjust.

I drop my book bag. “What’s wrong?” I say to him from across the room. I don’t want to know what’s wrong. I’m tired of this. You never know which father is going to show up.

He curls up and wraps his arms around his knees.

“I don’t know, Marya,” he says, and starts to cry. “I really don’t know.”

I stare at him flatly. I want to run over there and kick him and pound him until he gets up. When he gets like this, I feel like I am drowning. The hands of his sadness close around my throat and I can’t breathe. I have run out of the enormous love he needs to be all right.

“You know those afternoons,” he asks, drawing a shaking breath, “where you’re just going along, doing fine, and then afternoon comes and it feels like you just got the wind knocked out of you and everything is wrong?” He sighs and slowly pushes himself up so he’s sitting upright. His shoulders are slumped. “That’s all,” he says. “It’s just one of those afternoons.”

We are silent for a minute. Then he lies back down on the couch.

I should say I love him. I should say it will all be all right. But it won’t.

I walk down the hall to my bedroom. I lie down on my side and stare at the wall, the blue-flowered wallpaper next to my nose. Despite my best efforts, I start to cry.

I know those afternoons.

Escapes (#ulink_bd3afaf1-5d0f-5449-be75-d8eed93e5dfc)

Michigan, 1989

I’m sitting in the study lounge, it’s five A.M., and I have no idea how many nights or days have gone by since I last slept. I’m starving, I’m writing, I can’t stop, don’t want to stop, don’t want to eat, I am possessed by words. I’m at boarding school, an art school where students not yet eighteen spend ten hours a day, six days a week, training, practicing, studying harder than even seems possible, possessed by a desire to make it, to succeed, and I’m surrounded by open books on the study lounge table, my typewriter pouring out a short story, a paper, another, another. I am no longer a fuckup, I’m going to make it, I’m going to ace my classes, I’m going to stay awake forever if I have to, just so long as I write this, whatever it is.

Through the window that looks out over the snowy campus, the light is coming up. The snow is lit a violet-blue, the horizon’s a red-orange line. I sit back in my chair, my body buzzing, this heavenly hum in my head. Paper in stacks on the table. I’m ready for workshop, a fistful of stories in my hand. I’ve read everything for class that I was supposed to and then some. Physics thrills me, math confounds me, the German teacher despairs, but the English teacher, the writer-in-residence, the staff writers who pound us with work, they pull me aside and say: Read it, write it, don’t stop, you’ve got it, you’re going to make it. The magic words, the promise. The hope.

I just give up sleep. I’ve noticed by now that maybe my moods get a little crazier with sleep deprivation. Never mind. The deprivation unleashes a chemical reaction that feeds on itself, so that the less I sleep at night, the less I can sleep the next night, and the next. Night and day reverse themselves—but I’m not going to sleep during the day either. My body clock is no longer keeping time.

I don’t care. The future is unfurling ahead of me. I’m going to be a writer if it kills me. I will kill myself trying, I will get there, I’ve got to learn it, train for it, write it until the writing is perfect, until I get it, until I make it, I’m going to be real. This time I won’t fuck it up. I won’t fail.

The sun crests the horizon halfway, a winter sun, a blinding white. I stagger from the study lounge, carrying my piles of papers and books, and stumble down the stairs and into my room. My roommate is still asleep, the room still in shadow. As she mumbles in her sleep, I pull on my running shoes, go out into the cold, head across campus to the classroom building with the half-mile-long hall.

I run. Time stops. Thoughts stop. The never-ending pounding of my blood, the energy that surges through me all the time these days, it never runs out, I feel as if I will explode with it, I run. Up and down the long hall, compulsively touching the cold metal door on each end, must touch it or it doesn’t count, one mile, five miles, ten miles, chanting thinner, thinner, thinner, I am killing myself with the running, the starving, but I am alive, I run in the morning, between classes, during lunch, after school, during dinner, after workshops, before bed, and when I stop, I panic, afraid that until I run again, the flesh will creep back on my body. I’ve got to burn it off, get down to bones, a running, writing, starving skeleton, I eat only carrots and mustard, drink gallons of coffee, chatter with my friends, who tell me to stop, who worry, but they don’t understand, the flesh is always encroaching, trying to drown me, I will be thin, clean bones.

Minneapolis (#ulink_afefeb15-7ea7-54fa-bf0d-da9e44e1839e)

1990

I am caught. I pace up and down the hospital halls, the eating disorders ward back home, refusing to believe I’m half dead. These doctors are fools, my parents’ terror unfounded. Let me out! I holler. Leave me alone! I scream as the nurses chase me with Dixie cups of Ensure, the evil drink, all calories and fat. They’re trying to make up for what I’m burning while pacing, pacing, pacing the halls, panicked, hyper, locked in. I beat on the doors, crying, yell at my parents, stare at the food they put in front of me six times a day, Get it away, I won’t eat it, you can’t make me.

The doctor tells my parents I’m depressed. I know I’m not. Something else entirely is wrong. But doctors always say people with eating disorders are depressed. His diagnosis ignores my agitation, the fact that I sail up and crash down minute by minute. I guess he has his reasons: the extremity of my anorexia and bulimia is, to say the least, distracting. I have a life-threatening condition. No one—not my parents, not the therapists, and certainly not the doctors—has time to focus on the mayhem of my moods. Their primary goal is keeping me alive. But they’re missing the forest for the trees. (That happens to this day to patients with eating disorders. Doctors zoom in on the havoc that starving, bingeing, and purging wreaks on the body; and while it’s certainly true that some people with eating disorders have depression, the doctors assume that all of them do. So in people with eating disorders but without depression, the symptom is treated, but not the cause, and the physicians end up ignoring the mood disorders that the patients may actually have. The real underlying mental illness runs wild, advancing steadily, irreparably damaging the mind.)

Fuck this! I shout at my parents. I stand up from my chair and say again, Fuck this!

Marya, sit down.

No! I shout. I pace in circles around the room. The other patients and their families watch me from the corners of their eyes. My brain is burning. I stand over my parents, waving my arms. You can’t just keep me here! I scream. What about my civil rights?

You have no civil rights, my mother points out. Not until you’re eighteen.

I’m moving to California, I say.

What are you talking about?

I’ll live with Anne (she’s my father’s first wife), and I’ll go to school and everything.

They stare at me.

It will be totally good for me, I say, honing my argument—this plan has just occurred to me in the last three minutes, but now it is essential, imperative, that I go. It is the most important thing ever in my whole life.

I perk up, suddenly loving and cheerful. It will be totally healing for me, I say. I will totally get better. You won’t have to worryabout me. I’ll totally take in the sea air. It’s very centering out there.

California will be perfect. No one will watch me.

I’ll totally take long walks on the beach, I say. I’ll walk in the sunshine and celebrate the rain. I’ll get back in my body. I’ll do yoga. I’ll totally blossom. You see? It’s perfect. It’s just the thing.

My parents look at each other.

A few weeks later, they let me out of lockup, and I’m sitting on a plane.

California (#ulink_5b05a0e9-4d9e-5916-9017-3a79382d279d)

1990

Here I am, healing. Centering. By now I’m convinced that my eating disorder is entirely sensible, necessary, that I’m completely sane and everybody else is nuts. Obviously I had to get out of there.

I rattle through the salt-air night in the back of a pickup truck, heading for Bodega Bay. The bottles of booze, the baggies of pot, the friends from school. We trudge through the dunes, lie on our backs, stare up at the ocean of sky. I am in heaven. This is my hideaway. Here, I can starve without anyone stopping me. I can drink myself high, smoke myself into a steady drifting down. Here, I can write all night. If I can just make it through high school, I can escape to college in some city far away. I’ll be a writer and show them all that I am not a fuckup, I can make it, I am real.

The moods are steady, sky-high. My mind is racing ahead and I chase it, writing as fast as I can, failing heart stuttering, body disappearing. I can do anything. Nothing can stop me.

I’m a flurry of motion, sitting on the floor of my bedroom, arms flying, shuffling papers into piles, brain racing, reading snippets of writing, hopping up to get something on my desk, making rapid little red-pen marks on the pages, cutting and pasting, short of breath, pulse pounding, I am back in my element, where I can do a thousand things at once, fueled by the rabid energy triggered by the booze, no food, no sleep, I stand up and compulsively do three hundred leg lifts, balancing on the back of the chair—and I leap onto the chair and pierce my nose with a safety pin—and I climb out my window onto the roof, flinging my head back to look at the glorious blanket of stars and their halo, and the round-bellied moon—and I spin around in circles, arms out, teetering near the edge, dizzily gazing out over the dark, thick woods that surround the house—and I hop back in the window, grab my jacket, and dash down the stairs and out the door.

I walk down the long driveway onto the winding dark road that runs nearby, the Spanish moss hanging in heavy swags from the cypress and eucalyptus trees. I walk down to the strip mall in town, the neon signs fizzling in the night. I am violently alive. Every snap and spit of the neon pierces my eyes. A few cars go by, the whoosh of their tires making a hollow echo in my ears. This is my secret life, these nights I prowl and hide in shadows in the dark, walk the roads near their guardrails, the hills dropping sharply from the road to the valley below. Eventually, the lights, the noise, become too much, and the frenzied intensity begins to fray, tearing at my brain, slicing through my body like razor blades, and I walk down the road to my boyfriend’s house. He is older, stupid, stoned, and he passes me the joint and I take a deep drag and pass it to his sister and get up to get myself a drink. I flop belly-down on the carpet, watch the interior of my mind as it empties of thoughts. The agitation begins to subside, and I slide into a rocking, gentle nothingness. We watch idiotic reruns on TV. I am starving, and the hunger pinches at my gut. My head lolls. I lay face down on the carpet, the laugh track on the television rolling over me. I fall asleep.

I am lost, a satellite orbiting the world. The energy is turning dark, the sunshine of the early months here in California fading. The starving and the drinking and the disembodied sex—all my methods for stilling my thoughts are starting to fail me. I tell myself it’s not happening. I tell myself I’m all right. I can stay here. I can stand this. Surely, this will stop.

But a part of me knows I’m going to die, and doesn’t care. In fact, I wish like hell I would. I’m seventeen, and I’ve had enough.

Minneapolis (#ulink_72508129-2b73-59d4-b467-a6cbad0803b9)

1991

Caught again. Yellow-eyed, skeletal, bitchy, I am hauled back to Minnesota by my parents. Hospital, take two. Organs failing, deathly low weight, sick as a dog, but I’m fine, I’m fine, I’m fine. I sit on the floor, head nodding, nothing but static in my brain, my mother trying to get me to talk, speak, show some signs of life, my father making desperate jokes, trying to make me laugh. He cries and my mother cries, and through my fog I hate that they cry, and hate myself for making them cry, and, trying to form words, I tell them they don’t need to worry, I’m fine, please just leave me alone. Desert Storm plays a weird soundtrack to my days, fiery explosions on the TV screen, tanks barreling over entire towns, screaming people, that world far away—and I am far away too, lost in my own mind. The other patients hang limply over the arms of the couches and chairs, or stand in corners pretending to look at something, pacing in tiny, rapid circles, bouncing up and down, trying to burn off the calories that are keeping them alive. I lie awake at night, the bed bruising my bones, and listen to the wild, endless chatter of voices in my head.

Hospital, take three. Then the doctor’s had enough, tells my parents to put me in a state institution and leave me there. Instead, they find the last resort, a locked institution for kids as crazy as me. My last chance.

I am standing outside a square, two-story brick building. It’s ten degrees below zero, no flesh to keep me warm, and my mother grips me tight until the staff of this new place pulls me away. I look over my shoulder at my parents, they cry, I hate myself, I look forward, go away. Three triple-locked doors close one by one behind me as I follow the staff person inside, up the stairs, down the hall.

We are all crazy, under eighteen, the dregs of the system, the failures, the rejects of families, foster care, juvenile hall, we have been removed from society, a danger, a blight. We are a twelve-year-old car thief, a rapist, a sociopath, two cutters, a violent mute. We careen from pitching chairs and tables, to throwing our own bodies against the walls, to moments of calm that still the mayhem for a little while. We are in here for years, the shrieking girl, the roaring, crashing boys, the suicide attempts, the abused, the tortured, the troubled, the insane. I am here, wrapped in my coat, curled up in a ball, silent, afraid, disoriented, skinny, sick. I scream at mealtimes, pitch my food across the room, refuse to eat, they weigh me, I hate them, I swallow their fucking pills.

They are trying to kill me. Make me stupid, make me fat. They take my books, the only things I need to survive. If I can have my books, they’ll disappear, I’ll be safe, but they lock my books away, I scream and swear and cry and pound the walls, collapse on the floor, they say, Marya, you have a time-out, I go to my room and lie face-down on my bed, they come in with my treatment plan, you are assigned to play, you will play one hour a day, you will eat what you are told, you will not scream, you will make your bed, you will go to therapy, you will engage with other people, look me in the eye, you will not be allowed to push us away with your books. We spend our days in therapy groups, Marya, how are you feeling right now? I chew my nails until they’re bloody stumps, I stare at the floor, I have no books, I cannot starve, they’re pumping me full of pills, their kindness encroaches, surrounds me, suffocates me, Marya, it’s all right to feel, you will not die of feelings, why don’t you color your feelings on a piece of paper? Stop pushing them away, get out of your head, it’s safe out here. It is not. I am trapped.