Browning

Iain Finlayson

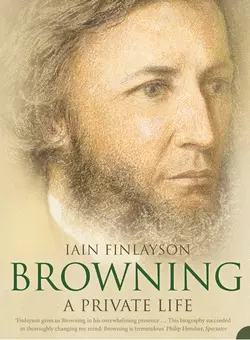

This edition does not include illustrations.A major biography of the most modern and the most underrated of English Literature's Great Victorians.Henry James called Robert Browning (1812–89) 'a tremendous and incomparable modern', and the immediacy and colloquial energy of his poetry has ensured its enduring appeal. This biography sets out to do the same for his life, animating the stereotypes (romantic hero, poetic exile, eminent man of letters) that have left him neglected by modern biographers. He has been seen primarily as one half of that romantic pair, the Brownings; and while the courtship, elopement and marriage of Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning remains a perennially seductive subject (and one Finlayson evokes vividly, quoting extensively from their daily letters and contemporary accounts) there is far more to Browning than that.Chronological in structure, this book is divided into three sections which deal with his life's major themes: adolescence and ambition, marriage and money, paternity and poetry. Browning explores the many experiences that inspired his writing, his education and passions, his relationships with family and friends, his continual financial struggles and revulsion at being seen as a fortune-hunter, his most unVictorian approach to marriage (sexual equality, his helping wean Elizabeth off morphine and nursing her through various illnesses), fatherhood and fame (inviting a leading member of the Browning Society to watch him burning a trunk of personal letters): all of which contribute to a fascinating portrait of a highly unconventional Victorian. At once witty and moving, this critical biography will revolutionise perceptions of the poet – and of the man.

BROWNING

A Private Life

IAIN FINLAYSON

DEDICATION (#u558bd85d-cb0d-5e46-8d02-a258a0df692d)

to Judith Macrae,

Good Friend and Good Samaritan

CONTENTS

Cover (#u3c1672c7-d687-528c-857d-6b318b6eeace)

Title Page (#ue9645622-fb7e-518f-b6c2-bb5808102e5b)

Prologue (#ua7dde85f-9b6f-542c-ba3a-97ed80a8b80d)

Part 1: Robert and the Brownings 1812–1846 (#uf955e16d-146c-55da-83fb-9139cde46fe7)

Part 2: Robert and Elizabeth 1846–1861 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part 3: Robert and Pen 1861–1889 (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Bibliographical Note (#litres_trial_promo)

Abbreviations and Short Citations of Principal Sources (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Notes (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PROLOGUE (#ulink_0f3c1dfb-c6af-58ff-b250-209fcca5cb44)

HENRY JAMES, a man of sound and profound literary and personal judgements, provided the most epigrammatic epitaph for Robert Browning. On the occasion of the poet’s burial in Westminster Abbey, on 31 December 1889, he remarked: ‘A good many oddities and a good many great writers have been entombed in the Abbey, but none of the odd ones have been so great and none of the great ones so odd.’

The immortal voice having been condemned to final silence by disinterested Nature, and the mortal dust committed to elaborate interment by a respectful nation, James reflected that only Browning himself could have done literary justice to the ceremony:

‘The consignment of his ashes to the great temple of fame of the English race was exactly one of those occasions in which his own analytic spirit would have rejoiced, and his irrepressible faculty for looking at human events in all sorts of slanting coloured lights have found a signal opportunity … in a word, the author would have been sure to take the special, circumstantial view (the inveterate mark of all his speculation) even of so foregone a conclusion as that England should pay her greatest honour to one of her greatest poets.’

Browning’s greatness and his oddity, his great value, in James’ view, was that ‘in all the deep spiritual and human essentials, he is unmistakably in the great tradition—is, with all his Italianisms and cosmopolitanisms, all his victimisation by societies organised to talk about him, a magnificent example of the best and least dilettantish English spirit’. That English spirit does not, generally, delight in literary or psychological subtleties; nevertheless, stoutly and steadfastly, ‘Browning made them his perpetual pasture, and yet remained typically of his race … His voice sounds loudest, and also clearest, for the things that, as a race, we like best—the fascination of faith, the acceptance of life, the respect for its mysteries, the endurance of its charges, the vitality of the will, the validity of character, the beauty of action, the seriousness, above all, of the great human passion.’

James particularly distinguished Browning as ‘a tremendous and incomparable modern’ who ‘introduces to his predecessors a kind of contemporary individualism’ long forgotten but now, in their latest honoured companion, forcefully renewed. These predecessors, disturbed in the long, dreaming serenity of Poets’ Corner and their ‘tradition of the poetic character as something high, detached and simple’ by the irruption of Browning, are obliged to measure their marmoreal greatness against Browning’s irreverent inversions and subversions that blew the spark of life into those poetic traditions. But death diminishes the force and power of any great man until—James observed—‘by the quick operation of time, the mere fact of his lying there among the classified and protected makes even Robert Browning lose a portion of the bristling surface of his actuality’. The stillness of silence and marble smooths out the poet and his work. The Samson who would crack the pillars of poetry is subsumed into the fabric of Poets’ Corner, of the Abbey, and of an Englishness that eventually, by force of the simplicity of its legends and the ineffable character of its traditions, stifles the vitality of the poet’s words and corrupts the subtle colours of their maker.

‘Victorian values’ has become a loaded phrase in recent times, sometimes revered, sometimes reviled. At best, the epithet for an age has provoked a revived interest not only in eminent Victorians but also, perhaps more so, in their ethical beliefs and social structures—though in our current perceptions those values are often misunderstood and misinterpreted when set against present-day values, which in turn are too often misapprehended by interested parties seeking to adapt them to their particular advantage and to the confusion of their opponents. Henry James gives the cue when he states that Robert Browning was a modern. Browning survives in the ‘great tradition’ as a ‘modern’ and, in his earlier life, he suffered for it. Matthew Arnold characterized Browning’s poetry as ‘confused multitudinousness’, and at first sight it is often bewildering. To cite the rolling acres of verse, the constantly (though not deliberately) obscure references, the occasional archaisms, is but to highlight a few surface difficulties.

To anyone unfamiliar with or still unseized by Robert Browning, his reputation as a serious, intellectual, difficult, and prolific writer is an impediment to reading even the most accessible of his poems. To the extent that he was serious—as he could be—he was serious because of his insistence on right and justice and the honest authenticity of his own work. To the extent that he was intellectual, he confounded even the most thoughtful critics of his day, and only now, with the perspective of time that enables more objective critical understanding of Victorian themes and thought, can his poetry be more deeply appreciated. To the extent that he was difficult, he was difficult because of his paradoxical simplicity. To the extent that he was prolific—well, he had a great deal to say on a great number of ideas and ideals, themes and topics.

The length of much of Browning’s poetry is daunting. The attention span of modern readers is supposedly more limited than that of the Victorians, though even the attention of the most persistent, discriminating intellects of the literary Victorians was liable to flag: George Eliot, noting advice to confine her own poetic epic, The Spanish Gipsy, to 9,000 lines, remarked in a letter of 1867 to John Blackwood, ‘Imagine—Browning has a poem by him [The Ring and the Book] which has reached 20,000 lines. Who will read it all in these busy days?’ The diversity, too, is intimidating: ‘You have taken a great range,’ remarked Elizabeth Barrett admiringly, ‘from those high faint notes of the mystics which are beyond personality—to dramatic impersonations, gruff with nature.’

To understand Henry James’s assertion that Browning was ‘a tremendous and incomparable modern’, it is necessary to understand the Victorian world as modern, as a dynamic, experimental, excitingly innovative age of achievements in exploration (internal and external) and advances in invention, but also as a time of doubts raised by experiments and enquiries. Browning himself is a prime innovator, an engineer of form, an explorer of history and the human heart, revolutionary in his art and of lasting importance in his achievements. One critic has suggested that Browning’s masterpiece, The Ring and the Book, may be viewed as a ‘heroic attempt to fuse Milton with Dickens, the modern novel with the epic poem’. Certainly, the comparison with Dickens is sustainable: Browning’s poetry is conspicuously democratic, rapid, colloquial, and modern in its preoccupation with individuals and the social, religious, and political systems in which they find themselves obliged to struggle, to progress throughout the history of humanity’s efforts to develop.

Words like ‘develop’ and ‘progress’ raise the matter of Browning’s optimism, which is usually taken at face value to mean his apparently consoling exclamations on the level of ‘God’s in his heaven—All’s right with the world’, ‘Oh, to be in England/Now that April’s there’, ‘Ah, but a man’s reach should exceed his grasp/Or what’s a heaven for?’, and so on. These are positive enough, and over-familiar to those who seek moral, theological, or nationalistic uplift from Browning. They have become the stuff of samplers and poker-work, tag lines expressive of a pious sentimentality (‘It was roses, roses all the way …’) he rarely intended, a jingoistic English nationalism (‘Oh, to be in England …’) he hardly felt, and a shining Candidean optimism (‘God’s in his heaven …’) that was the least of his philosophy. Browning’s poetry too often survives miserably as useful material to be raided and packaged for books of inspirational verse-in-snippets and comfortable quotations. This is a permanent fame, perhaps, but not Parnassian glory.

Browning’s optimism was a more robust and muscular characteristic, deriving not at all from sweet-natured sentimentality or rose-tinted romanticism. Rather, it was rooted in a profound, passionate realism—naturalism, some claim—and tremendous psychological analysis that looked unsparingly, with a clear eye, at the roots and shoots of good and evil. Unlike most Victorians, Robert Browning was more matter-of-factly medieval or ruthlessly Renaissance in his assessments and acceptance of matters from which fainter, or at least more emollient, spirits retreated and who drew a more or less banal moral satisfactory to the pious, who tended to prefer the possibility of redemption through suffering. For some readers, suffering was quite sufficient in itself—a just reward and retribution for the sin or moral failure, for example, of being poor.

Browning’s innate Puritanism, as Chesterton remarks, stood him in good stead, providing a firm foothold ‘on the dangerous edge of things’ while he investigated ‘The honest thief, the tender murderer.’ The early attempts of the Browning Society and others to construct a ‘philosophy’ for Browning, a redeeming and inspirational theological and ethical system to stand as firmly as that imposed by Leslie Stephen on Wordsworth, is bound to be suspect in specifics and should be distrusted in general.

That Browning was a lusty optimist is rarely doubted in the popular mind, but the evidence adduced to support the theory is too often selective and superficial. His optimism was in fact an appetite and enthusiasm for life in all its aspects, inclusive rather than exclusive, from the highest joy to the darkest trials. His optimism was an expression of endurance, of acceptance, of the vitality of living and loving, of finding value in the extraordinary individuality and oddity of men and women. Robert Browning is, in the judgement of G. K. Chesterton, ‘a poet of misconceptions, of failures, of abortive lives and loves, of the just-missed and the nearly fulfilled: a poet, in other words, of desire’. Ezra Pound insists on Browning’s poetic passion. Men and Women, the collection of poems that redeemed Browning from obscurity in middle-age, is a demotic, democratic piece of work that reflects his distance from his early reliance on the remote Romantic imagery of Shelley and adopts a firmer insistence on the mundane life of city streets and market-places.

This interest in the apparently tawdry, temporal life of fallible men and women somewhat disconcerted his more elevated, intellectual contemporaries. Of The Ring and the Book, George Eliot (who should have known better, and might have had more sympathy for the poem in her youth) commented: ‘It is not really anything more than a criminal trial, and without anything of the pathetic or awful psychological interest which is sometimes (though very rarely) to be found in such stories of crime. I deeply regret that he has spent his powers on a subject which seems to me unworthy of them.’ She was not the only contemporary critic to make such a point, or adopt such an aesthetic view: Thomas Carlyle declared the poem to be ‘all made out of an Old Bailey story that might have been told in ten lines and only wants forgetting’.

In short, Browning shocked his contemporaries. The shock consequent on his choice of subject matter was perhaps compounded by the novelty of his poetic approach to its treatment. Pippa Passes, startlingly unlike in form to anything contemporaneous in English poetry, is regarded by Chesterton, aside from ‘one or two by Walt Whitman’, as ‘the greatest poem ever written to express the sentiment of the pure love of humanity’. Like Whitman, Browning was responsive to the spirit of his age. For all his learning and his familiarity with the past, and for all his choice of antique subject matter and foreign locations, Browning is no funeral grammarian of a past culture, of spent history. His portrait of the Florentine artist Fra Lippo Lippi is as living, as vibrant, and as relevant as might be a current account of the life of the modern painters Francis Bacon or Damien Hirst. The speeches in The Ring and the Book might, with some adjustments, make a modern television or radio series examining a murder case from the points of view of all the protagonists. The form of serial views of one event was not new when Browning revived it from Greek classic models, but he infused it with modernity and it has since become a staple model for dramatists.

Browning did not bestride the peaks of poetry like a Colossus with a lofty and noble eye for the prospect at his feet. He rambled like a natural historian, peering and poking in holes and corners, describing minutely and drawing his particular conclusions; he visited the courtroom with a reporter’s notebook, and the morgue with the equipment of a forensic scientist. He was an entomologist of humanity in all its bizarre conditions of being. His great subjects were philosophy, religion, history, politics, poetry, art, and music—a few more than even Ezra Pound later marked out as the fit and proper preoccupations of serious poetry. They were all encompassed in Browning’s studies of modern society and the men and women of a universal humankind.

Browning’s poetry is often of a period, but in no sense is it period poetry, nor is Browning a period poet. In this he differs from the more consciously archaic writers and works of the Pre-Raphaelites who admired him, strove to imitate him, and embedded themselves in a literary aspic. Whereas his successors became conscious, perhaps dandified and decadent, Browning himself was largely and serenely unconscious, vigorous, and often matter-of-fact. He had principles and opinions, at first devoutly and latterly didactically held. But Browning was learned and assimilative rather than rigorously intellectual. His poetry suffers often from obscurities that puzzle intellectuals because Browning was, above all, a widely and profoundly literate, well-read man.

Once he had absorbed a fact or a thesis, he subsumed it in his mind where it found useful and congenial company. Joined with a mass of other facts and theses, it became so inextricably enmeshed with its fellows that, when it was eventually pulled out to illustrate, embellish, or point up a phrase in Browning’s work, it was comprehensible only—though not always afterwards, when he had done with it—to the mind of the poet. Being already so personally familiar with it, he thought nothing of its unfamiliarity to his readers. Chesterton regards this as the greatest compliment he could have paid the average reader. There are many who may feel too highly complimented. In this sense, his poetry is devoid of intellectual arrogance or one-upmanship. Perfectly innocently and without conscious affectation, Browning’s work arises from and is coloured with what Henry James identified as an ‘all-touching, all-trying spirit … permeated with accumulations and playing with knowledge’.

For all his modernity, now increasingly acknowledged and admired by literary critics, Browning has recently been somewhat neglected by literary biographers. ‘What’s become of Waring?’ is a well-known line from one of his best-known poems. What, one may reasonably ask, has become of Browning? There is no lack of interest in him in one sense—in the sense of Robert Browning as one half of that romantic pair, the Brownings. The marriage of Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning remains a perennially seductive subject, and not only for biographers. One difficulty for the modern biographer is that Robert Browning’s reputation has never quite lived down being cast as a great romantic hero, the juvenile lead, as it were, in Rudolph Besier’s 1934 stage play The Barretts of Wimpole Street and subsequently in the Hollywood movie, where Robert Browning was played dashingly and dramatically by Fredric March. This has become his principal claim to popular fame. For various reasons, Robert has become the dimmer partner, Elizabeth the brilliant star. The romantic hero of fiction or drama is, in any case, generally only a foil for the romantic heroine.

There are big modern biographies of most of Browning’s contemporaries, and more are published every year, but Browning himself is comparatively unknown to present-day readers. Elizabeth Barrett Browning is, to be realistic, the more immediately colourful and engaging character—the drama of her early years as a supposed invalid, the romance of her marriage to Robert Browning and their escape to Italy, the currently fashionable interest in her as an early feminist and as a radical in terms of her views on politics and social justice. Her husband, by contrast, is perceived as a more reactionary and conventional, a more prudish and private character. If judged solely by the quantity and quality of their letters to friends and acquaintances, his personality is less immediately engaging, and, for all his superficial sociability, more introverted and private.

In contrast to the relative scarcity of biographies of Robert Browning, there is an astonishing quantity of critical monographs and papers hardly penetrable to any but the Browning academic specialist. What has recently been lacking, is a chronological narrative of Browning’s life as an upstage drama to complement the downstage chorus of critics of his work. This present book is a conventional, chronological biography of Browning. Despite the enormous and constant critical attention paid to Browning, and the number of books about Elizabeth Barrett Browning and the marriage of the Brownings, there have been few modern biographies that give themselves over mostly to the life and character of the man himself.

The standard late twentieth-century biography of Robert Browning that confidently, authoritatively, and entertainingly treats his life as thoroughly as his poetry is The Book, the Ring, and the Poet by William Irvine and Park Honan, published in 1974. Robert Browning: A life within life, Donald Thomas’s biography, published in 1982, is the conscientious work of a scholar who combines a life of the poet with critical analysis of his work. Clyde de L. Ryal’s 1993 biography, The Life of Robert Browning, is an attractive, authoritative literary critical work that provides an overview of Browning’s life and work as a bildungsroman without the distraction of—for the purposes of his book—unnecessary domestic detail.

In this present biography, I have of course been heedful of as much recent biographical work on Browning as seemed to me relevant to my purposes—specific references are gratefully (and comprehensively, I hope) acknowledged—but I have not neglected earlier biographies in my search for such materials as Nathaniel Hawthorne might have characterized as the ‘wonderfully and pleasurably circumstantial’.

A principal resource for any Browning biographer must be the official Life and Letters of Robert Browning (1891) by Mrs Alexandra Sutherland Orr, a close friend of the poet. Mrs Orr wrote her biography at the request of Browning’s son and sister. Besides the obvious constraints of these two interested parties at her shoulder, she was writing, too, soon after Browning’s death, as a close friend as much as a conscientious critic. She is thus, and naturally, tactful. Though she is not deliberately misleading, nevertheless she will occasionally suppress materials when she considers it discreet to do so, and will sometimes turn an unfortunate episode to better, more positive account than we might now consider appropriate. A close, long-standing friend of Browning’s, William Wetmore Story, supplied Mrs Orr with details of their long friendship. On reading the published biography in 1891, he commented that it seemed rather colourless, but admitted that Browning’s letters ‘are not vigorous or characteristic or light—and as for incidents and descriptions of persons and life it is very meagre’. Subsequent biographers have supplied the deficit.

My second principal biographical authority is Gilbert Keith Chesterton, whose short book about Browning, published in 1903, is valuable less for strict biographical fact, which now and again he gets wrong, than for consistently inspired and constantly inspiriting psychological judgements about the poet and his work, which he gets right. Like Mrs Orr, Chesterton’s value is that he was closer in time and thought to the Victorian age, more attuned to the Browning period and the psychology of the protagonists than we are now, closer to the historical literary ground than we can be. Chesterton’s Robert Browning has never been bettered. It remains unarguably perceptive and uniquely provocative. Besides its near-contemporaneity to its subject, Chesterton’s book is valuable because it evokes Browning’s character with the very ironies and psychological inversions that Browning himself often employed in his poetry. Time and again Chesterton proposes the converse to prove the obverse, exactly as Browning could easily—with poetic prestidigitation—prove black to be white or red.

Two lively, thoughtful women—Betty Miller and Maisie Ward—have contributed more recent biographies that sometimes convincingly and sometimes controversially propose psychological and psychoanalytic interpretations of Robert Browning, his poetry, and his life. Their insights are regularly disputed, and perhaps for that very reason they regularly startle their readers out of complacency. They ask questions, raise points, that—right or wrong—are still worth serious consideration by Browning’s critics and biographers.

I should also say that I have generally relied on earlier Browning criticism, which retains much of its vigour and sparky originality. This is by no means to belittle latter-day critics, many of whom write ingeniously and excitingly, but merely to indicate that for the purposes of this biography I have for the most part personally preferred period sources and contemporary authorities. An exception has to be made for The Courtship of Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett, Daniel Karlin’s close and authoritative study of the love-letters that preceded the marriage. This book is indispensable to any modern biographer of Browning, not just for Karlin’s detailed analysis of the voluminous correspondence but also for the tenderness and imagination he brings to its interpretation.

There is—or has been—a discussion about how far the biography of an objective poet is necessary, in contrast to the permissible biography of a subjective poet. Browning gave his own views on this in his essay on Shelley. Since Browning himself is generally reckoned to combine subjective and objective elements in his work, then it probably follows that a biography detailing the day-to-day activities of the poet may be as relevant as a critical commentary on his poetry. G. K. Chesterton remarked that one could write a hundred volumes of glorious gossip about Browning. The Collected Letters of Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, when the full series is finally published, will be exactly that. But for all the froth and bubble of Browning’s social life, not a great deal happened to him—there is a distinct dearth of dramatic incident. One is inclined to sigh with relief, like Joseph Brodsky who says of Eugenio Montale, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1975 for the poetry he had written over a period of sixty quiet years, ‘thank God that his life has been so uneventful’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

And yet, as Chesterton concedes of Browning biography, ‘it is a great deal more difficult to speak finally about his life than his work. His work has the mystery which belongs to the complex; his life the much greater mystery which belongs to the simple.’ By and large, my biographical preference has been for a straightforward (I won’t say simple) chronological narrative rather than a series of thematic chapters. And so, this biography is divided into three major sections. These large sections deal successively with three subjects associated with three themes: adolescence and ambition, marriage and money, paternity and poetry.

I like, too, the unfashionable Victorian biographical convention of ‘Life and Letters’. Much of this book is based on the correspondence of Robert and Elizabeth Browning, from which I have quoted lengthily and freely. Where either of them have written personally, or their words have been otherwise recorded by others, I have often preferred to quote them directly rather than make my own paraphrase. Their own voices are important—the tone, the vocabulary, the tempo of the sentences, the entire texture of their poetry, letters, and recorded conversation: all contribute to our understanding of character. The Brownings’ letters are not referenced to the various collections in which they have appeared over the years, since chronological publication of their complete collected correspondence is currently in progress. All dated letters will finally be found there in their proper place.

My reliance on previous biographical materials is deliberate. Far from studiously avoiding them, I have sedulously pillaged them. Biographies are a legitimate secondary source just as much as the first-hand memoirs of those who once saw Shelley, Browning, or any other poet plain and formed an impression that they set down in words or pictures for posterity. It might be argued that a scrupulous biographer who is familiar with all the details of his or her subject’s life may indeed be better informed as to the subject’s character than those friends and enemies who knew him in his outward aspect but were less intimately acquainted with his private life. An enemy of Browning’s, Lady Ashburton, is a case in point. She formed a view of a Miss Gabriel that proved to be wrong. Lady Ashburton, to her credit, thereupon fell to wondering that two views of Miss Gabriel’s character could be so contrary. As a starting-point for biography, her surprised surmise could hardly be bettered. Her latterly-held opinion of Robert Browning could have benefited from some similar consideration of his contrarieties.

‘A Poet’, wrote John Keats, ‘is the most unpoetical of anything in existence; because he has no Identity—he is continually informing and filling some other Body.’

(#litres_trial_promo) This remark, though referring to poets in general, seems to justify the view of Henry James and others that Robert Browning the public personality and Robert Browning the private poet were two distinct personalities. When the biographer stops to point to an image or a word that is apparently autobiographical (or at least seems open to a subjective interpretation), it is because biography imposes a structure and perceives a coherence that the subject himself cannot fully be aware of. The literary biographer neither need be completely contre Sainte-Beuve, nor feel officiously obliged to seek biographical meaning in a text. And yet, of course, Robert Browning is one man, not a series of discrete doppelgängers inhabiting parallel universes. To quote Joseph Brodsky again, ‘every work of art, be it a poem or a cupola, is understandably a self-portrait of its author … a lyrical hero is invariably an author’s self-projection … The author … is a critic of his century; but he is a part of this century also. So his criticism of it nearly always is self-criticism as well, and this is what imparts to his voice … its lyrical poise. If you think that there are other recipes for successful poetic operation, you are in for oblivion.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

I have avoided, so far as possible, attributing feelings to Browning or anyone else that they are not known to have felt. I have tried to suppose no emotions that are not supported by the statement of anyone who experienced them personally or observed them in others and interpreted their effects. I have stuck so far as possible to the facts insofar as they are known and can be supported, if not ideally by first-hand sources, at least credibly by reliable hearsay; and—where facts fail and supposition supersedes—by creditable biographical consensus and, in the last resort, my own fallible judgement.

Nevertheless, and despite all best intentions, biography is a form of fiction, and successive biographies create, rather like the monologuists in The Ring and the Book, a palimpsest of their subject. Like a Platonic symposium, all the guests at the feast will have their own ideas to propound. A biography, like a novel, tells a story. It contains a principal subject, subsidiary characters, a plot (in the form, normally, of a more or less chronological narrative), and subplots, and it unfolds over a certain period of time in various locations. It has a beginning, a middle, and an end, however much these elements may be creatively juggled. That the biographer is not his subject is the point at which the narrative takes on the aspect of fiction. The subject lived his or her life for, say, threescore years and ten, and—allowing for various forms of psychological self-defence—he or she may be regarded as the first authority for that life. Autobiography, however, is generally even more fiction than biography, even less trustworthy than biography. If we put not our faith in princes or poets, even less should we trust an apologist pro vita sua. As Jeanette Winterson puts it, ‘autobiography is art and lies’.

Poetry, of course, may be said to be art and truth. The poet, even if he lies in every other aspect of his life, cannot consistently lie in his work. Robert Browning’s poetry tells the truth not only about Robert Browning, but about the men and women he loved and the common humanity he shared with them and sought to understand. Says Chesterton, with an irresistible conviction and authority:

Every one on this earth should believe, amid whatever madness or moral failure, that his life and temperament have some object on the earth. Every one on this earth should believe that he has something to give to the world which cannot otherwise be given. Every one should, for the good of men and the saving of his own soul, believe that it is possible, even if we are the enemies of the human race, to be the friends of God … With Browning’s knaves we have always this eternal interest, that they are real somewhere, and may at any moment begin to speak poetry.

Lacking the vanity and hypocrisy of the age, Browning was blind to no one, and to the best and the worst of them in their inarticulacy he gave the voice of his own understanding, compassion, and love as few had done so sincerely since Chaucer, Shakespeare, and Burns.

PART 1 ROBERT AND THE BROWNINGS 1812–1846 (#ulink_2de07354-9147-5c62-bd54-c3fe7dd2284e)

ONLY ONE THING is known for certain about the appearance of Sarah Anna Browning, wife of Robert Browning and mother of Robert and Sarianna Browning: she had a notably square head. Which is to say, its uncommon squareness was noted by Alfred Domett, a young man sufficiently serious as to become briefly, in his maturity, Prime Minister of New Zealand and sometime epic poet. Mr Domett, getting on in years, conscientiously committed this observation to his journal on 30 April 1878: ‘I remembered their mother about 40 years before (say 1838), who had, I used to think, the squarest head and forehead I almost ever saw in a human being, putting me in mind, absurdly enough no doubt of a tea-chest or tea-caddy.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Many people have square heads. There is little enough to be interpreted from this characteristic, though to some minds a square head may naturally imply sturdy common sense and a regular attitude to life. A good square head is commonly viewed as virtually a guarantee of correct behaviour and a restrained attitude towards vanity and frivolity. Lombroso’s forensic art of physiognomy being now just as discredited as palmistry or phrenology, we may turn with more confidence to Thomas Carlyle’s shrewd and succinct assessment of Mrs Browning as being ‘the type of a Scottish gentlewoman’.

(#litres_trial_promo) The phrase is evocative enough for those who, like Carlyle, have enjoyed some personal experience and acquired some understanding at first hand of the culture that has bred and refined the Scottish gentlewoman over the generations. She is a woman to be reckoned with. Since we know nothing but bromides and pleasing praises of Sarah Anna’s temperament beyond what may be conjectured, particularly from Carlyle’s brief but telling phrase, we may take it that she was quieter and more phlegmatic than Jane Welsh, Carlyle’s own Scottish gentlewoman wife whose verbal flyting could generally be relied upon to rattle the teeth and teacups of visitors to Carlyle’s London house in Cheyne Walk.

Mrs Browning’s father was German. Her grandfather is said to have been a Hamburg merchant whose son William is generally agreed to have become, in a small way, a ship owner in Dundee and to have married a Scotswoman. She was born Sarah Anna Wiedemann in Scotland, in the early 1770s, and while still a girl came south with her sister Christiana to lodge with an uncle in Camberwell. Her history before marriage is not known to have been remarkable; after marriage it was not notably dramatic. There is only the amplest evidence that she was worthily devoted to her hearth, garden, husband, and children.

Mrs Browning’s head so fascinated Alfred Domett that he continued to refer to it in a domestic anecdote agreeably designed to emphasize the affection that existed between mother and son: ‘On one occasion, in the act of tossing a little roll of music from the table to the piano, he thought it had touched her head in passing her, and I remember how he ran to her to apologise and caress her, though I think she had not felt it.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Sarah Anna Browning’s head was at least tenderly regarded and respected by Robert, her son, who—since he has left no description of it to posterity in prose or poetry—either refrained from disobliging comment or regarded its shape as in no respect unusual.

Mrs Browning was a Dissenter; her creed was Nonconformist, a somewhat austere faith that partook of no sacraments and reprobated ritual. She—and, nine years into their marriage, her husband—adhered to the Congregational Church, the chapel in York Street, Walworth, which the Browning family attended regularly to hear the preaching of the incumbent, the Revd George Clayton, characterized in the British Weekly of 20 December 1889 as one who ‘combined the character of a saint, a dancing master, and an orthodox eighteenth-century theologian in about equal proportions’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Before professing Congregationalism, she had been brought up—said Sarianna, her daughter, to Mrs Alexandra Sutherland Orr—in the Church of Scotland. One of the books that is recorded as a gift from Mrs Browning to her son is an anthology of sermons, inscribed by him on the flyleaf as a treasured possession and fond remembrance of his mother. As a token of maternal concern for her son’s spiritual welfare it was perfectly appropriate, and might perhaps have been intended as a modest counterweight to the large and eclectic library of books—six thousand volumes, more or less—that her husband had collected, continued to collect, and through which her precocious son was presently and diligently reading his way.

Sarah Anna Browning doubtless had cause to attempt to concentrate young Robert’s mind more narrowly. He had begun with a rather sensational anthology, Nathaniel Wanley’s Wonders of the Little World, published in 1678, and sooner rather than later would inevitably discover dictionaries and encyclopedias, those seemingly innocent repositories of dry definitions and sober facts but which are, in truth, a maze of conceits and confusions, of broad thoroughfares and frustrating cul-de-sacs from which the imaginative mind, once entered, will find no exit and never in a lifetime penetrate to the centre.

But Mrs Browning’s head, square with religion and good intentions, was very liable to be turned by kindly feeling towards her son and poetry. Robert, in 1826, had already come across Miscellaneous Poems, a copy of Shelley’s best works, published by William Benbow of High Holborn, unblushingly pirated from Mrs Shelley’s edition of her husband’s Posthumous Poems. This volume was presented to him by a cousin, James Silverthorne, and he was eager for a more reliable, authoritative edition. Having made inquiries of the Literary Gazette as to where they might be obtained, Robert requested the poems of Shelley as a birthday present.

(#litres_trial_promo) Mrs Browning may be pictured putting on her gloves, setting her bonnet squarely on her head and proceeding to Vere Street. There, at the premises of C. & J. Ollier, booksellers, she purchased the complete works of the poet, including the Pisa edition of Adonais in a purple paper cover and Epipsychidion. None of them had exhausted their first editions save The Cenci, which had achieved a second edition.

On advice, as being in somewhat the same poetic spirit as the works of the late Percy Bysshe Shelley who had died tragically in a boating accident in Italy but three years before, Sarah Anna Browning added to her order three volumes of the poetry of the late John Keats, who had died, also tragically young, in Rome in 1821. Her arms encumbered with the books of these two neglected poets, her head quite innocent of the effect they would have, she returned home to present them to her son. There being not much call for the poetry of Shelley and Keats at this time, it had taken some effort to obtain their works. Bibliophiles, wrote Edmund Gosse in 1881 in the December issue of the Century Magazine, turn almost dazed at the thought of these prizes picked up by the unconscious lady.

The Browning family belonged, remarked G. K. Chesterton, ‘to the solid and educated middle-class which is interested in letters, but not ambitious in them, the class to which poetry is a luxury, but not a necessity’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Robert Browning senior, husband to Sarah Anna Wiedemann, was certainly educated, undeniably middle-class, and interested in literature not so much for its own sake—though he was more literate and widely read, it may safely be said, than many of his colleagues at the Bank of England—but more from the point of view of bibliophily and learning. There was always another book to be sought and set on a shelf. The house in Camberwell was full of them.

Literature and learning are not precisely the same thing, and Mr Browning senior, according to the testimony of Mr Domett, was accustomed to speak of his son ‘“as beyond him”’—alluding to his Paracelsuses and Sordellos; though I fancy he altered his tone on this subject very much at a later period’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Poetry safely clapped between purple paper covers is one thing, poets are quite another—and an experimental, modern poet within the confines of one’s own family is bound to be unsettling to a traditionalist, try as he may to comprehend, proud as he may be of completed and published effort. Mr Browning senior may initially have been more pleased with the fact of his son’s work being printed and bound and placed in its proper place on his bookshelves than with the perplexing contents of the books themselves.

That said, introductory notes by Reuben Browning to a small volume of sketches by Robert Browning senior refer kindly to his stepbrother’s bibliophily and store of learning—however much at random and magpie-like it may have been acquired: ‘The love of reading attracted him by sympathy to books: old books were his delight, and by his continual search after them he not only knew all the old books-stalls in London, but their contents, and if any scarce work were spoken of, he could tell forthwith where a copy of it might be had. Nay, he would even describe in what part of the shop it was placed, and the price likely to be asked for it.’

(#litres_trial_promo) So, ‘with the scent of a hound and the snap of a bull-dog’ for an old or rare book, Mr Browning acquired learning and a library.

‘Thus his own library became his treasure,’ remarked Reuben Browning. ‘His books, however, were confessedly not remarkable for costly binding, but for their rarity or for interesting remarks he had to make on most of them; and his memory was so good that not infrequently, when a conversation at his table had reference to any particular subject, has he quietly left the room and in the dark, from a thousand volumes in his library, brought two or three illustrations of the point under discussion.’ The point under discussion, however esoteric, would rarely defeat Mr Browning senior’s search for an apposite reference: ‘His wonderful store of information,’ wrote Reuben Browning, ‘might really be compared to an inexhaustible mine. It comprised not merely a thorough scholastic outline of the world, but the critical points of ancient and modern history, the lore of the Middle Ages, all political combinations of parties, their descriptions and consequences; and especially the lives of the poets and painters, concerning whom he ever had to communicate some interesting anecdote not generally known.’

A portrait of Mr Browning senior, preserved throughout their lives by his children, was ‘blue-eyed and “fresh-coloured”’ and, attested Mr Browning’s daughter Sarianna to Alfred Domett, the man himself ‘had not an unsound tooth in his head’ when he died at the age of 84. In his youth he had been a vigorous sportsman, afflicted only by sore throats and a minor liver complaint. Altogether, his general health and recuperative powers were strongly marked. Alfred Domett took these facts of paternal health and heredity seriously, on the ground that ‘they have their significance with reference to the physical constitution of their son, the poet; which goes so far as to make up what is called “genius”’.

So far as Domett was aware, no cloud shadowed the home life of the Brownings: ‘Altogether, father, mother, only son and only daughter formed a most suited, harmonious and intellectual family, as appeared to me.’ Mr Browning senior, to Domett, was not often a physically significant presence: his friend’s father, ‘of whom I did not see much, seemed in my recollection, what I should be inclined to call a dry adust [sic] undersized man; rather reserved; fond particularly of old engravings, of which I believe he had a choice collection.’ Mr Browning took pleasure not only in collecting pictures but also in making them. He was liable to sketch the heads of his colleagues and visitors to the Bank of England, a habit so much encouraged by his employers that hundreds of these whiskered heads survive to this day.

Mr Browning also wrote poetry of a traditional kind. His son in later life praised his father’s verses to Edmund Gosse, declaring ‘that his father had more true poetic genius than he has’. Gosse, taking this with scarcely too gross a pinch of salt and allowing for filial piety, kindly but rigorously comments that, ‘Of course the world at large will answer, “By their fruits shall ye know them,” and of palpable fruit in the way of published verse the elder Mr Browning has nothing to show.’ The elder Browning’s poetic taste was more or less exclusively for double or triple rhyme, and especially for the heroic couplet, which he employed with ‘force and fluency’. Gosse goes on to quote the more celebrated son describing the moral and stylistic vein of the father’s vigorous verses ‘as that of a Pope born out of due time’. Mr Browning had been a great classicist and a lover of eighteenth-century literature, the poetry of that period having achieved, in his estimation, its finest flowering in the work of Alexander Pope. Though his son’s early poetry, Pauline and Paracelsus, confounded him, Mr Browning senior forgave the otherwise impenetrable Sordello because—says William Sharp in his Life of Browning—‘it was written in rhymed couplets’.

Pope, according to the critic Mark Pattison, ‘was very industrious, and had read a vast number of books, yet he was very ignorant; that is, of everything but the one thing which he laboured with all his might to acquire, the art of happy expression. He read books to find ready-made images and to feel for the best collocations of words. His memory was a magazine of epithets and synonyms, and pretty turns of language.’ Mr Browning senior’s satirical portraits of friends and colleagues are said to be very Pope-ish in expression, quick sketches reminiscent in their style of Pope’s rhetorical (often oratorical) couplets. It is further said that he was incapable of portraying anyone other than as a grotesque. The sketch of his wife is certainly none too flattering.

This domestic, middle-class idyll, quiet-flowing and given muted colour by art, poetry, music, bibliophily and decent religious observances, was touching to Alfred Domett, who recollected his serene memories of the Browning family in the tranquillity that fell upon him after leaving public office in New Zealand and returning to London to look up an old friend now celebrated as an important poet and public figure.

Mr Browning, like his wife, became a Dissenter and a Nonconformist in middle life, though it had taken Sarah Anna Browning time and energy to persuade him from the Episcopal communion. In his youth, he had held principles and expressed opinions, uncompromisingly liberal, that had all but brought him to ruin—certainly had distanced him from the prospect of maintaining at least, perhaps increasing, the family fortune that derived from estates and commercial interests in the West Indies. His father, the first Robert Browning, had been born the eldest son in 1749 to Jane Morris of Cranborne, Dorset, wife to Thomas Browning who in 1760 had become landlord of Woodyates Inn, close to the Dorset-Wiltshire border, which he had held on a 99-year lease from the Earl of Shaftesbury. Thomas and Jane Browning produced five more children, three sons (one of whom died young) and two daughters.

Robert the First, as he may here be styled, was to become grandfather of the poet. He was recommended by Lord Shaftesbury for employment in the Bank of England, where he served for the whole of his working life, fifty years, from August 1769, when he would have been about the age of twenty, becoming Principal of the Bank Stock Office, a post of some considerable prestige which implied wide contact with influential financiers. This first Robert Browning was no man, merely, of balance sheets and bottom-polished trousers: at about the age of forty, he vigorously assisted, as a lieutenant in the Honourable Artillery Company, in the defence of the Bank of England during the Gordon Riots of 1780.

In 1778, he married Margaret Morris Tittle, a lady who had been born in the West Indies, reputedly a Creole (and said, by some, to have been darker than was then thought decent), by whom he sired three children—Robert, the eldest, being born on 6 July 1782 at Battersea. A second son, William, was born and died in 1784. A daughter, Margaret—who remained unmarried and lived quietly until her death in 1857 (or 1858, according to a descendant, Vivienne Browning)—was born in 1783. Nothing more is heard of Margaret, beyond a reference by Cyrus Mason, a Browning cousin, who in later life composed a memoir in which he wrote that ‘Aunt Margaret was detected mysteriously crooning prophecies over her Nephew, behind a door at the house at Camberwell.’

The picture of an eccentric prophetess lurking at keyholes and singing the fortunes of the future poet is not conjured by any other biographer of Robert Browning. Cyrus Mason is not widely regarded as a reliable chronicler of Browning family history. He begins with his own self-aggrandizing agenda and sticks to it. His reputation is rather as a somewhat embittered relation who took the view that the poet Robert Browning and his admirers had paid inadequate attention and given insufficient credit to the more remote branches of the family. The contribution of the extended family to the poet’s early education, he considered, had been cruelly overlooked and positively belittled by wilful neglect.

However, since the reference to Margaret Browning does exist, and since Margaret has otherwise vanished from biographical ken, a possible—rather than probable—explanation for this single recorded peculiarity of the poet’s aunt is that she may have been simple-minded and thus kept in what her family may have regarded (not uncommonly at the time) as a decent, discreet seclusion. The extent to which they succeeded in containing any public embarrassment may—and it is no more than supposition—account for Margaret’s virtually complete obscurity in a family history that has been otherwise largely revealed.

Margaret Morris Tittle Browning died in Camberwell in 1789, when Robert (who can be referred to as Robert the Second), her only remaining son, was seven years old. When Robert was twelve, his father remarried in April 1794. This second wife, Jane Smith, by whom he fathered nine more children, three sons, and six daughters, was but twenty-three at the time of her marriage in Chelsea to the 45-year-old Robert Browning the First. The difference of twenty-two years between husband and wife is said, specifically by Mrs Sutherland Orr, Robert Browning’s official biographer, sister of the exotic Orientalist and painter Frederic Leighton, and a friend of the poet, to have resulted in the complete ascendancy of Jane Smith Browning over her husband. Besotted by, and doting upon, his young darling, he made no objection to Jane’s relegation of a portrait (attributed to Wright of Derby) of his first wife to a garret on the basis that a man did not need two wives. One—the living—in this case proved perfectly sufficient.

The hard man of business and urban battle, the doughty Englishman of Dorset stock, the soundly respectable man who annually read the Bible and Tom Jones (both, probably, with equal religious attention), the stout and severe man who lived more or less hale—despite the affliction of gout—to the age of eighty-four, was easily subverted by a woman whose gnawing jealousy of his first family extended from the dead to the quick. Browning family tradition, says Vivienne Browning, a family historian, also attributes a jealousy to Robert the First, naturally anxious to retain the love and loyalty of his young wife against any possible threat, actual or merely perceived in his imagination. Their nine children, a substantial though not unusual number, may have been conceived and borne as much in response to jealousy, doubt, and fear as in expression of any softer feelings.

Jane Browning’s alleged ill-will towards Robert the Second, Robert the First’s son by his previous marriage to Margaret Tittle, was not appeased by the young man’s independence, financial or intellectual. He had inherited a small income from an uncle, his mother’s brother, and proposed to apply it to a university education for himself. Jane, supposedly on the ground that there were insufficient funds to send her own sons to university, opposed her stepson’s ambition. Then, too, there was some irritation that Robert the Second wished to be an artist and showed some talent for the calling. Robert the First—says Mrs Orr—turned away disgustedly when Robert the Second showed his first completed picture to his father. The household was plainly a domestic arena of seething discontents, jealous insecurities, envious stratagems, entrenched positions on every front, and sniper fire from every corner of every room.

Margaret Tittle had left property in the West Indies, and it was Robert the First’s intention that their son should proceed, at the age of nineteen, to St Kitts to manage the family estates, which were worked by slave labour. He may have been glad enough to go, to remove himself as far as possible from his father and stepmother. In the event, he lasted only a year in the West Indies before returning to London, emotionally bruised by his experience of the degrading conditions under which slaves laboured on the sugar plantations. Robert the Second’s reasonable expectation was that he might inherit perhaps not all, but at least a substantial proportion of his mother’s property, had he not ‘conceived such a hatred of the slave system’.

Mrs Sutherland Orr states: ‘One of the experiences which disgusted him with St Kitts was the frustration by its authorities of an attempt he was making to teach a negro boy to read, and the understanding that all such educative action was prohibited.’ For a man who, from his earliest years, was wholly devoted to books, art, anything that nourished and encouraged inquiry and intellect, the spiritual repression of mind and soul as much—perhaps more than—physical repression of bodily freedom, must have seemed an act of institutionalized criminality and personal inhumanity by the properly constituted authorities. He could not morally consider himself party to, or representative of, such a system.

Certainly as a result of the apparent lily-livered liberalism of his son and his shocking, incomprehensible disregard for the propriety of profit, conjecturally also on account of a profound unease about maintaining the affection and loyalty of his young wife—there were only ten years between stepmother Jane and her stepson—Robert the First fell into a passionate and powerful rage that he sustained for many years. Robert Browning, the grandson and son of the protagonists of this quarrel, did not learn the details of the family rupture until 25 August 1846, when his mother finally confided the circumstances of nigh on half a century before.

‘If we are poor,’ wrote Robert Browning the Third the next day to Elizabeth Barrett, ‘it is to my father’s infinite glory, who, as my mother told me last night, as we sate alone, “conceived such a hatred to the slave-system in the West Indies,” (where his mother was born, who died in his infancy,) that he relinquished every prospect,—supported himself, while there, in some other capacity, and came back, while yet a boy, to his father’s profound astonishment and rage—one proof of which was, that when he heard that his son was a suitor to her, my mother—he benevolently waited on her Uncle to assure him that his niece “would be thrown away on a man so evidently born to be hanged”!—those were his very words. My father on his return, had the intention of devoting himself to art, for which he had many qualifications and abundant love—but the quarrel with his father,—who married again and continued to hate him till a few years before his death,—induced him to go at once and consume his life after a fashion he always detested. You may fancy, I am not ashamed of him.’

As soon as Robert the Second achieved his majority, he was dunned by his father for restitution in full of all the expenses that Robert the First had laid out on him, and he was stripped of any inheritance from his mother, Margaret, whose fortune, at the time of her marriage, had not been settled upon her and thus had fallen under the control of her husband. These reactions so intimidated Robert the Second that he agreed to enter the Bank of England, his father’s territory, as a clerk and to sublimate his love of books and sketching in ledgers and ink. In November 1803, four months after his twenty-first birthday, he began his long, complaisant, not necessarily unhappy servitude of fifty years as a bank clerk in Threadneedle Street.

A little over seven years later, at Camberwell on 19 February 1811, in the teeth of his father’s opposition, Robert the Second married Sarah Anna Wiedemann, whose uncle evidently disregarded Robert the First’s predictions. She was then thirty-nine, ten years older than her husband and only one year younger than his stepmother Jane. They settled at 6 Southampton Street, Camberwell, where, on 7 May 1812, Sarah Anna Browning was delivered of a son, the third in the direct Browning line to be named Robert. Twenty months later, on 7 January 1814, their second child, called Sarah Anna after her mother, but known as Sarianna by her family and friends, was born.

William Sharp, in his Life of Browning, published in 1897, refers briskly and offhandedly to a third child, Clara. Nothing is known of Clara: it is possible she may have been stillborn or died immediately after birth. Mrs Orr never mentions the birth of a third child, and not even Cyrus Mason, the family member one would expect to seize eagerly upon the suppression of any reference to a Browning, suggests that more than two children were born to the Brownings. However, William Clyde DeVane, discussing Browning’s ‘Lines to the Memory of his Parents’ in A Browning Handbook, states that ‘The “child that never knew” Mrs Browning was a stillborn child who was to have been named Clara.’ The poem containing this discreet reference was not printed until it appeared in F.G. Kenyon’s New Poems by Robert Browning, published in 1914, and in the February issue, that same year, of the Cornhill Magazine. Vivienne Browning, in My Browning Family Album, published in 1992, declares that her grandmother (Elizabeth, a daughter of Reuben Browning, son of Jane, Robert the First’s second wife) ‘included a third baby—a girl—in the family tree’, but Vivienne Browning ‘cannot now find any evidence to support this’.

It is known that Sarah Anna Browning miscarried at least once. In a letter to his son Pen, the poet Robert Browning wrote on 25 January 1888 to condole with him and his wife Fannie on her miscarriage: ‘Don’t be disappointed at this first failure of your natural hopes—it may soon be repaired. Your dearest Mother experienced the same misfortune, at much about the same time after marriage: and it happened also to my own mother, before I was born.’ Unless Sarah Anna’s miscarriage occurred in a very late stage of pregnancy, it seems improbable that a miscarried child should have been given a name and regarded, in whatever terms, as a first-born—but natural parental sentiment may have prompted the Brownings to give their first daughter, who never drew breath, miscarried or stillborn, at least the dignity and memorial of a name.

The small, close-knit family moved house in 1824, though merely from 6 Southampton Street to another house (the number is not known) in the same street, where they remained until December 1840. Bereaved of his mother at the age of seven, repressed from the age of twelve by his father and stepmother, denied further education and frustrated in his principles and ambitions in his late teens, all but disinherited for failure to make a success of business and to close a moral eye to the inhumanity of slavery, set on a high stool and loaded with ledgers in his early twenties, it is hardly surprising that Robert the Second sought a little peace and quiet for avocations that had moderated into hobbies. He settled for a happy—perhaps undemanding—marriage to a peacable, slightly older wife, and a tranquil bolt-hole in what was then, in the early nineteenth century, the semi-rural backwater of Camberwell.

His poverty, counted in monetary terms, was relative. His work in the Bank of England, never as elevated or responsible as Robert the First’s, was nevertheless adequately paid, the hours were short and overtime, particularly the lucrative night watch, was paid at a higher rate. There was little or no managerial or official concern about the amount of paper, the number of pens, or the quantity of sealing wax used by Bank officials, and these materials were naturally regarded as lucrative perquisites that substantially bumped up the regular salary. Though Mrs Orr admits this trade, she adds—somewhat severely—in a footnote: ‘I have been told that, far from becoming careless in the use of these things from his practically unbounded command of them, he developed for them an almost superstitious reverence. He could never endure to see a scrap of writing-paper wasted.’

He could count on a regular salary of a little more than £300 a year, supplemented by generous rates of remuneration for extra duties and appropriate perks of office. He may have been deprived of any interest in his mother’s estate, but his small income from his mother’s brother, even after deductions from it by his father, continued to be a reliable annual resource. Over the years, Robert the Second acquired valuable specialist knowledge of pictures and books, and certainly, though he was no calculating businessman and willingly gave away many items from his collection, he occasionally—perhaps regularly—traded acquisitions and profited from serendipitous discoveries.

In the end, though it was a long time coming, Robert the First softened towards his eldest son. That he was not wholly implacable is testified by his will, made in 1819, two years before his retirement from the Bank: he left Robert the Second and Margaret ten pounds each for a ring. This may seem a paltry inheritance, but he took into account the fact that Robert and Margaret had inherited from ‘their Uncle Tittle and Aunt Mill a much greater proportion than can be left to my other dear children’. He trusted ‘they will not think I am deficient in love and regard to them’. As a token of reconciliation, the legacy to buy rings was a substantial olive branch.

It may be assumed that the patriarch Browning’s temper had begun to abate before he made his will, and that the Brownings had resumed some form of comfortable, if cautious, communication until the old man’s death. There is certainly some indication that Robert the First saw something of his grandchildren—the old man is said by Mrs Orr to have ‘particularly dreaded’ his lively grandson’s ‘vicinity to his afflicted foot’, little boys and gout being clearly best kept far apart. After the death of Robert the First in 1833, stepmother Jane, then in her early sixties, moved south of the river from her house in Islington to Albert Terrace, just beyond the toll bar at New Cross. In the biography of Robert Browning published in 1910 by W. Hall Griffin and H.C. Minchin, it is said that the portrait of the first Mrs Browning, Margaret Tittle, had been retrieved from the Islington garret and was hung in her son’s dining room.

The most familiar photograph of Robert the Second, taken—it looks like—in late middle age (though it is difficult to tell, since he is said to have retained a youthful appearance until late in life) shows the profile of a rather worried-looking man. A deep line creases from the nostril to just below the side of the mouth, which itself appears thin and turns down at the corner. The hair is white, neatly combed back over the forehead and bushy around the base of the ears. It is the picture of a doubtful man who looks slightly downward rather than straight ahead, as though he has no expectation of seeing, like The Lost Leader, ‘Never glad confident morning again!’. He still bled, perhaps, from the wounds inflicted upon him as a child and young man: but if he did, he suffered in silence.

As some men for the rest of their lives do not care to talk about their experiences in war, so Robert the Second could never bring himself to talk about his bitter experiences in the West Indies: ‘My father is tenderhearted to a fault,’ wrote his son to Elizabeth Barrett on 27 August 1846. The poet’s mother had confided some particulars to him three days before, but from his father he had got never a word: ‘I have never known much more of those circumstances in his youth than I told you, in consequence of his invincible repugnance to allude to the matter—and I have a fancy to account for some peculiarities in him, which connects them with some abominable early experience. Thus,—if you question him about it, he shuts his eyes involuntarily and shows exactly the same marks of loathing that may be noticed if a piece of cruelty is mentioned … and the word “blood,” even makes him change colour.’

These ‘peculiarities’ observed in his father by the youngest Browning did not go unremarked by others who, with less fancy than his son to seek an origin for them, were content to observe and to wonder at this marvellous man. Cyrus Mason, as an amateur historian of the Browning family, speaks specifically of Robert the Second’s ‘imaginative and eccentric brain’. It seems likely that he is not only confessing his own bewilderment, which becomes ever more apparent as his memoir proceeds, but a general incomprehension within the wider Browning family. Inevitably, mild eccentricities of character become magnified by family and friends otherwise at a loss to account for the somewhat detached life of a man who is for all practical, day-to-day intents and purposes a conscientious banker and responsible family man, but whose domestic and inner life, so far as it is penetrable by others, exhibits a marked degree of abstraction and commitment to matters that harder, squarer heads would not regard as immediately profitable in the conduct of everyday life—‘Robert’s incessant study of subjects perfectly useless in Banking business’, to quote Cyrus Mason. Such minor aberrations are naturally inflated in the remembrance and the retelling, particularly when it becomes evident that such a man has become, indirectly, an object of interest and attention through efforts made by admirers or detractors to trace the early influences upon his remarkable son.

Mrs Orr tells us that Robert the Second, when he in turn became a grandfather, taught his grandson elementary anatomy, impressing upon young Pen Browning ‘the names and position of the principal bones of the human body’. Cyrus Mason adds considerably to this blameless, indeed worthy, anecdote by claiming that ‘Uncle Robert became so absorbed in his anatomical studies that he conveyed objects for dissection into the Bank of England; on one occasion a dead rat was kept for so long a time in his office desk, awaiting dissection, that his fellow clerks were compelled to apply to their chief to have it removed! The study of anatomy became so seductive that on the day Uncle Robert was married, he disappeared mysteriously after the ceremony and was discovered … busily engaged dissecting a duck, oblivious of the fact that a wife and wedding guests were reduced to a state of perplexity by his unexplained absence.’

This story has the air of invention by a fabulist—Mr Browning, being a little peckish, might merely have been carving a duck—and earlier echoes of preoccupied, enthusiastic amateur morbid anatomists recur to the mind (in the annals of Scottish eccentricity, there are several instances of notable absence of mind of more or less this nature at wedding feasts); there is even a faint, ludicrous hint of Francis Bacon fatally catching a cold while stuffing a chicken with snow by the roadside in an early endeavour to discover the principles of refrigeration. The patronizing tone is one of barely-tolerant amusement, of reminiscence dressed up with a dry chuckle, of family anecdote become fanciful.

‘Uncle Robert’, in short, was held—more or less exasperatedly—to be something of a whimsical character. His seeming inclination to desert the ceremonies and commonplace observances of ‘real life’, of family life, for abstruse, even esoteric researches—all those books!—may be exaggerated, but the metamorphosis of memory into myth is generally achieved through the medium of an actuality. The pearl of fiction accretes around a grain of actuality, and in this case the attitudes and behaviour of Robert Browning, father of the poet, achieve a relevance in respect of his attitude towards the education, intellectual liberty, and the vocation of his son.

Robert the Second, frustrated in his own creative ambitions, did not discourage his son from conducting his life along lines that he himself had been denied. Cyrus Mason declares that, from the beginning, the ‘arranged destiny’ of Robert and Sarah Anna’s son was to be a poet. His life and career, says Mason, were planned from the cot. The infant Robert’s ‘swaddling clothes were wrapped around his little body with a poetic consideration’, his father rocked his cradle rhythmically, his Aunt Margaret ‘prophecied [sic] in her dark mysterious manner his brilliant future’, and women lulled him to sleep with whispered words of poetry. Whether unconsciously or by design, Mason here introduces the fairy-story image of the good or bad fairy godmothers conferring gifts more or less useful.

Allowing for the Brothers Grimm or Perrault quality of these images conjured by Mason, and his patent intention in writing his memoir to arrogate a substantial proportion of the credit for the infant Robert’s development to a wider family circle of Brownings, there is a nub of truth in his assertion. There is some dispute as to how far it may be credited, of course. Mrs Orr merely states that the infant Robert showed a precocious aptitude for poetry: ‘It has often been told how he extemporised verse aloud while walking round and round the dining room table supporting himself by his hands, when he was still so small that his head was scarcely above it.’ Some children naturally sing, some dance, some draw little pictures and some declaim nonsense verse or nursery rhymes: Robert Browning invented his own childish verses. Doting family relations would naturally exclaim over his prospects as a great poet and genially encourage the conceit.

That he was raised from birth as—or specifically to become—a poet is improbable: more unlikely still is the assertion that he was raised ‘poetically’ by parents whose inclinations in the normal run of things were kindly and indulgent in terms of stimulating their son’s natural and lively intelligence, but not inherently fanciful: they were respectably pious, middle-class, somewhat matter-of-fact citizens of no more and no less distinction than others of their time, place, and type. They were distinctive enough to those who loved them or had cause to consider them, but they were not—in the usual meaning of the word—distinguished.

They were what G.K. Chesterton calls ‘simply a typical Camberwell family’ after he sensibly dismisses as largely irrelevant to immediate Browning biography all red herrings such as the alleged pied-noir origins of Margaret Tittle (which may have been true), a supposed Jewish strain in the Browning family (now discounted, but which would have been a matter of extreme interest to the poet), and the suggestion, from the fact that Browning and his father used a ring-seal with a coat of arms, of an aristocratic origin dating from the Middle Ages for the family name, if not for the family itself.

Nevertheless, in thrall to the romance of pedigree and the benefits that may be derived from a selective use of genealogy, Cyrus Mason’s memoir is motivated not only by a gnawing ambition to associate himself and his kinsfolk more closely with the poet Browning and to aggrandize himself by the connection, but also, vitally, to give the lie to the ‘monstrous fabrication’ by F.J. Furnivall, a devoted admirer and scholar of the poet Browning, that the Brownings descended from the servant class, very likely from a footman, later butler, to the Bankes family at Corfe Castle before becoming innkeepers. Cyrus Mason claims to trace the Browning lineage back unto the remotest generations—at least into the fourteenth century—to disprove any stigma of low birth. He even manages to infer, from some eighteenth-century holograph family documents, the high cost of binding some family books, the good quality of the ink used, and, from the evidence of ‘fine bold writing’, a prosperous, educated, literary ancestry. These elaborate researches were of the greatest possible interest to Cyrus Mason: they consumed his time, consoled his soul, confirmed his pride, and confounded cavilling critics.

Cyrus Mason was satisfied with his work, and it is to his modest credit that he has amply satisfied everyone else, most of whom are now content to acknowledge this monument to genealogical archaeology and pass more quickly than is entirely respectful to more immediate matters. We consult Mason’s book much as visitors to an exhibition browse speedily through the well-researched but earnest expository notes at the entrance and hurry inside to get to the interesting main exhibit. ‘For the great central and solid fact,’ declared G. K. Chesterton, ‘which these heraldic speculations tend inevitably to veil and confuse, is that Browning was a thoroughly typical Englishman of the middle class.’ Allowing, naturally, for his mother’s Scottish-German parentage and his grandmother’s Creole connection, Robert Browning was certainly brought up as a middle-class Englishman.

Chesterton’s argument, scything decisively through the tangled undergrowth of genealogy and the rank weeds of heterogeneous heredity, becomes a spirited, romantic peroration, grandly swelling as he praises Robert Browning’s genius to the heights, then dropping bathetically back as he regularly nails it to the ground by constantly reminding us that Browning was ‘an Englishman of the middle class’; until, finally, he sweeps to his breathtaking and irresistible conclusion that Browning ‘piled up the fantastic towers of his imagination until they eclipsed the planets; but the plan of the foundation on which he built was always the plan of an honest English house in Camberwell. He abandoned, with a ceaseless intellectual ambition, every one of the convictions of his class; but he carried its prejudices into eternity.’

Robert Browning’s mother was no bluestocking: she was not herself literary, nor was she inclined to draw or paint in water-colours. Her husband did enough book collecting and sketching already. Though she had a considerable taste for music and is said to have been an accomplished pianist (Beethoven’s sonatas, Avison’s marches, and Gaelic laments are cited as belonging to her repertoire), she was very likely no more than ordinarily competent on a piano, though her technique was evidently infused with fine romantic feeling. Sarah Anna Browning tended her flower garden (Cyrus Mason remarks upon ‘the garden, Aunt Robert’s roses, that wicket gate the Robert Browning family used by favor, opening for them a ready way to wander in the then beautiful meadows to reach the Dulwich woods, the College and gallery’) and otherwise occupied herself, day by day, with domestic matters relating to her largely self-contained, self-sufficient family. Other biographers beg to differ when Mrs Orr tells us that Mrs Browning ‘had nothing of the artist about her’. In contrast to her husband, she produced nothing artistic or creative, but partisans speak warmly of her tender interest in music and romantic poetry. She possessed at least an artistic sensibility.

Mrs Orr remarks, cursorily but not disparagingly: ‘Little need be said about the poet’s mother’, the implication—quite wrong—being that there was little to be said. Her son’s devotion to Sarah Anna was very marked: habitually, when he sat beside her, Robert would like to put his arm around her waist. When she died in early 1849, he beatified her by describing her as ‘a divine woman’. Most biographers and others interested in the poet Browning make a point of the empathetic feeling that developed between mother and son: when Sarah Anna Browning was laid low with headaches, her son dreadfully suffered sympathetic pains. ‘The circumstances of his death recalled that of his mother,’ says Mrs Orr, and adds, however ‘it might sound grotesque’, that ‘only a delicate woman could have been the mother of Robert Browning’.

She was certainly religious, and none doubted that her place in heaven had long been marked and secured by her narrow piety, commonsense good nature, and her stoical suffering of physical ailments. Sarah Anna Browning endured debilitating, painful headaches, severe as migraines (which indeed they may have been). In contrast to her vigorously hale husband, she is portrayed by Mrs Orr as ‘a delicate woman, very anaemic during her later years, and a martyr to neuralgia which was perhaps a symptom of this condition’.