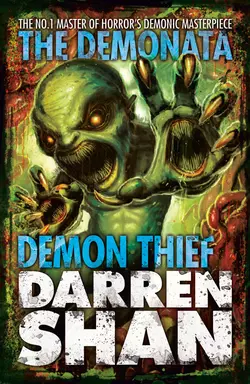

Demon Thief

Darren Shan

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Детская фантастика

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 458.46 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: A hellish nightmare for only the bravest of readers… Darren Shan’s horrifying series, The Demonata, continues with Demon Thief.When Kernel Fleck′s brother is stolen by demons, he must enter their universe in search of him. It is a place of magic, chaos and incredible danger. Kernel has three aims:• learn to use magic,• find his brother,• stay alive.But a heartless demon awaits him, and death has been foretold…