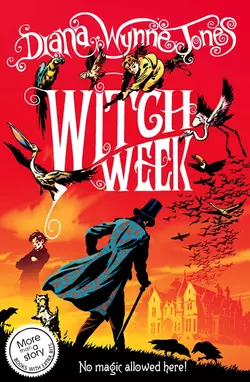

Witch Week

Witch Week

Diana Wynne Jones

Glorious new rejacket of a Diana Wynne Jones favourite, featuring Chrestomanci – now a book with extra bits!SOMEONE IN THIS CLASS IS A WITCHWhen the note, written in ordinary ballpoint, turns up in the homework books Mr Crossley is marking, he is very upset. For this is Larwood House, a school for witch-orphans, where witchcraft is utterly forbidden. And yet magic keeps breaking out all over the place - like measles!The last thing they need is a visit from the Divisional Inquisitor. If only Chrestomanci could come and sort out all the trouble.

Diana Wynne Jones

WITCH WEEK

Illustrated by Tim Stevens

Contents

Cover (#u622e91bf-6cee-5463-b08f-4a0f999bc509)

Title Page (#u8ac21811-bc26-5982-a7d3-13217e7e58fa)

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

More than a Story

Spotlight on Diana Wynne Jones

Which Witch?

Types of Magic

Enchanted Travel

Have you ever wondered?

If you like, you’ll love …

Other Works

Copyright

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER ONE (#u69483a27-a89e-5ee5-a135-aa68f23603ac)

The note said: SOMEONE IN THIS CLASS IS A WITCH. It was written in capital letters in ordinary blue ballpoint, and it had appeared between two of the Geography books Mr Crossley was marking. Anyone could have written it. Mr Crossley rubbed his ginger moustache unhappily. He looked out over the bowed heads of Class 2Y and wondered what to do about it.

He decided not to take the note to the Headmistress. It was possibly just a joke, and Miss Cadwallader had no sense of humour to speak of. The person to take it to was the Deputy Head, Mr Wentworth. But the difficulty there was that Mr Wentworth’s son was a member of 2Y – the small boy near the back who looked younger than the rest was Brian Wentworth. No. Mr Crossley decided to ask the writer of the note to own up. He would explain just what a serious accusation it was and leave the rest to the person’s conscience.

Mr Crossley cleared his throat to speak. A number of 2Y looked up hopefully, but Mr Crossley had changed his mind by then. It was Journal time, and Journal time was only to be interrupted for a serious emergency. Larwood House was very strict about that rule.

Larwood House was very strict about a lot of things, because it was a boarding school run by the government for witch-orphans and children with other problems. The journals were to help the children with their problems. They were supposed to be strictly private. Every day, for half an hour, every pupil had to confide his or her private thoughts to their journal, and nothing else was done until everyone had. Mr Crossley admired the idea heartily.

But the real reason that Mr Crossley changed his mind was the awful thought that the note might be true. Someone in 2Y could easily be a witch. Only Miss Cadwallader knew who exactly in 2Y was a witch-orphan, but Mr Crossley suspected that a lot of them were. Other classes had given Mr Crossley feelings of pride and pleasure in being a schoolmaster. 2Y never did. Only two of them gave him any pride at all: Theresa Mullett and Simon Silverson. They were both model pupils.

The rest of the girls tailed dismally off until you came to empty chatterers like Estelle Green, or that dumpy girl, Nan Pilgrim, who was definitely the odd one out. The boys were divided into groups. Some had the sense to follow Simon Silverson’s example, but quite as many clustered round that bad boy Dan Smith, and others again admired that tall Indian boy, Nirupam Singh. Or they were loners like Brian Wentworth and that unpleasant boy Charles Morgan.

Here Mr Crossley looked at Charles Morgan and Charles Morgan looked back, with one of the blank, nasty looks he was famous for. Charles wore glasses, which enlarged the nasty look and trained it on Mr Crossley like a double laser beam. Mr Crossley looked away hastily and went back to worrying about the note. Everyone in 2Y gave up hoping for anything interesting to happen and went back to their journals.

28 October 1981, Theresa Mullett wrote in round, angelic writing.

Mr Crossley has found a note in our geography books. I thought it might be from Miss Hodge at first, because we all know Teddy is dying for love of her, but he looks so worried that I think it must be from some silly girl like Estelle green. Nan Pilgrim couldn’t get over the vaulting-horse again today. She jumped and stuck halfway. It made us all laugh.

Simon Silverson wrote:

28.10.81 I would like to know who put that note in the Geography books. It fell out when I was collecting them and I put it back in. If it was found lying about we could all be blamed. This is strictly off the record of course.

I do not know, Nirupam Singh wrote musingly, how anyone manages to write much in their journal, since everyone knows Miss Cadwallader reads them all during the holidays. I do not write my secret thoughts. I will now describe the Indian rope trick which I saw in India before my father came to live in England…

Two desks away from Nirupam, Dan Smith chewed his pen a great deal and finally wrote,

Well I mean it’s not much good if you’ve got to write your secret fealings, what I mean is it takes all the joy out of it and you don’t know what to write. It means they aren’t secret if you see what I mean.

I do not think, Estelle Green wrote, that I have any secret feelings today, but I would like to know what is in the note from Miss Hodge that Teddy has just found. I thought she scorned him utterly.

At the back of the room, Brian Wentworth wrote, sighing, Timetables just run away with me, that is my problem. During Geography, I planned a bus journey from London to Baghdad via Paris. Next lesson I shall plan the same journey via Berlin.

Nan Pilgrim meanwhile was scrawling,

This is a message to the person who reads our journals. Are you Miss Cadwallader, or does Miss Cadwallader make Mr Wentworth do it?

She stared at what she had written, rather taken aback at her own daring. This kind of thing happened to her sometimes. Still, she thought, there were hundreds of journals and hundreds of daily entries. The chances of Miss Cadwallader reading this one had to be very small – particularly if she went on and made it really boring.

I shall now be boring, she wrote. Teddy Crossley’s real name is Harold, but he got called Teddy out of the hymn that goes ‘Gladly my cross I’d bear.’ But of course everyone sings ‘Crossley my glad-eyed bear.’ Mr Crossley is glad-eyed. He thinks everyone should be upright and honourable and interested in Geography. I am sorry for him.

But the one who was best at making his journal boring was Charles Morgan. His entry read,

I got up. I felt hot at breakfast. I do not like porridge. Second lesson was Woodwork but not for long. I think we have Games next.

Looking at this, you might think Charles was either very stupid or very muddled, or both. Anyone in 2Y would have told you that it had been a chilly morning and there had been cornflakes for breakfast. Second lesson had been PE, during which Nan Pilgrim had so much amused Theresa Mullett by failing to jump the horse, and the lesson to come was Music, not Games. But Charles was not writing about the day’s work. He really was writing about his secret feelings, but he was doing it in his own private code so that no one could know.

He started every entry with I got up. It meant, I hate this school. When he wrote I do not like porridge, that was actually true, but porridge was his code-word for Simon Silverson. Simon was porridge at breakfast, potatoes at lunch, and bread at tea. All the other people he hated had code-words too. Dan Smith was cornflakes, cabbage and butter. Theresa Mullett was milk.

But when Charles wrote I felt hot, he was not talking about school at all. He meant he was remembering the witch being burnt. It was a thing that would keep coming into his head whenever he was not thinking of anything else, much as he tried to forget it.

He had been so young that he had been in a pushchair. His big sister Bernadine had been pushing him while his mother carried the shopping, and they had been crossing a road where there was a view down into the Market Square. There were crowds of people down there, and a sort of flickering. Bernadine had stopped the pushchair in the middle of the street in order to stare. She and Charles had just time to glimpse the bone-fire starting to burn, and they had seen that the witch was a large fat man. Then their mother came rushing back and scolded Bernadine on across the road.

“You mustn’t look at witches!” she said. “Only awful people do that!” So Charles had only seen the witch for an instant. He never spoke about it, but he never forgot it. It always astonished him that Bernadine seemed to forget about it completely. What Charles was really saying in his journal was that the witch came into his head during breakfast, until Simon Silverson made him forget again by eating all the toast.

When he wrote Woodwork second lesson, he meant that he had gone on to think about the second witch – which was a thing he did not think about so often. Woodwork was anything Charles liked. They only had Woodwork once a week, and Charles had chosen that for his code on the very reasonable grounds that he was not likely to enjoy anything at Larwood House any oftener than that. Charles had liked the second witch. She had been quite young and rather pretty, in spite of her torn skirt and untidy hair. She had come scrambling across the wall at the end of the garden and stumbled down the rockery to the lawn, carrying her smart shoes in one hand. Charles had been nine years old then, and he was minding his little brother on the lawn. Luckily for the witch, his parents were out.

Charles knew she was a witch. She was out of breath and obviously frightened. He could hear the yells and police whistles in the houses behind. Besides, who else but a witch would run away from the police in the middle of the afternoon in a tight skirt? But he made quite sure. He said, “Why are you running away in our garden?”

The witch rather desperately hopped on one foot. She had a large blister on the other foot, and both her stockings were laddered. “I’m a witch,” she panted. “Please help me, little boy!”

“Why can’t you magic yourself safe?” Charles asked.

“Because I can’t when I’m this frightened!” gasped the witch. “I tried, but it just went wrong! Please, little boy – sneak me out through your house and don’t say a word, and I’ll give you luck for the rest of your life. I promise.”

Charles looked at her in that intent way of his which most people found blank and nasty. He saw she was speaking the truth. He saw, too, that she understood the look as very few people seemed to. “Come in through the kitchen,” he said. And he led the witch, hobbling on her blister in her laddered stockings, through the kitchen and down the hall to the front door.

“Thanks,” she said. “You’re a love.” She smiled at him while she put her hair right in the hall mirror, and, after she had done something to her skirt that may have been witchcraft to make it seem untorn again, she bent down and kissed Charles. “If I get away, I’ll bring you luck,” she said. Then she put her smart shoes on again and went away down the front garden, trying hard not to limp. At the front gate, she waved and smiled at Charles.

That was the end of the part Charles liked. That was why he wrote But not for long next. He never saw the witch again, or heard what had happened to her. He ordered his little brother never to say a word about her – and Graham obeyed, because he always did everything Charles said – and then he watched and waited for any sign of the witch or any sign of luck. None came.

It was next to impossible for Charles to find out what might have happened to the witch, because there had been new laws since he glimpsed the first witch burning. There were no more public burnings. The bone-fires were lit inside the walls of gaols instead, and the radio would simply announce: “Two witches were burnt this morning inside Holloway Gaol.” Every time Charles heard this kind of announcement he thought it was his witch. It gave him a blunt, hurtful feeling inside. He thought of the way she had kissed him, and he was fairly sure it made you wicked too, to be kissed by a witch.

He gave up expecting to be lucky. In fact, to judge from the amount of bad luck he had had, he thought the witch must have been caught almost straight away. For the blunt, hurtful feeling he had when the radio announced a burning made him refuse to do anything his parents told him to do. He just gave them his steady stare instead. And each time he stared, he knew they thought he was being nasty. They did not understand it the way the witch did. And, since Graham imitated everything Charles did, Charles’s parents very soon decided Charles was a problem child and leading Graham astray. They arranged for him to be sent to Larwood House, because it was quite near.

When Charles wrote Games, he meant bad luck. Like everyone else in 2Y, he had seen Mr Crossley had found a note. He did not know what was in the note, but when he looked up and caught Mr Crossley’s eye, he knew it meant bad luck coming.

Mr Crossley still could not decide what to do about the note. If what it said was true, that meant Inquisitors coming to the school. And that was a thoroughly frightening thought. Mr Crossley sighed and put the note in his pocket. “Right, everyone,” he said. “Put away your journals and get into line for Music.”

As soon as 2Y had shuffled away to the school hall, Mr Crossley sped to the staff room, hoping to find someone he could consult about the note.

He was lucky enough to find Miss Hodge there. As Theresa Mullett and Estelle Green had observed, Mr Crossley was in love with Miss Hodge. But of course he never let it show. Probably the only person in the school who did not seem to know was Miss Hodge herself. Miss Hodge was a small neat person who wore neat grey skirts and blouses, and her hair was even neater and smoother than Theresa Mullett’s. She was busy making neat stacks of books on the staff room table, and she went on making them all the time Mr Crossley was telling her excitedly about the note. She spared the note one glance.

“No, I can’t tell who wrote it either,” she said.

“But what shall I do about it?” Mr Crossley pleaded. “Even if it’s true, it’s such a spiteful thing to write! And suppose it is true. Suppose one of them is—” He was in a pitiable state. He wanted so badly to attract Miss Hodge’s attention, but he knew that words like witch were not the kind of words one used in front of a lady. “I don’t like to say it in front of you.”

“I was brought up to be sorry for witches,” Miss Hodge remarked calmly.

“Oh, so was I! We all are,” Mr Crossley said hastily. “I just wondered how I should handle it—”

Miss Hodge lined up another stack of books. “I think it’s just a silly joke,” she said. “Ignore it. Aren’t you supposed to be teaching 4X?”

“Yes, yes. I suppose I am,” Mr Crossley agreed miserably. And he was forced to hurry away without Miss Hodge having looked at him once.

Miss Hodge thoughtfully squared off another stack of books, until she was sure Mr Crossley had gone. Then she smoothed her smooth hair and hurried away upstairs to find Mr Wentworth.

Mr Wentworth, as Deputy Head, had a study where he wrestled with the timetable and various other problems Miss Cadwallader gave him. When Miss Hodge tapped on the door, he was wrestling with a particularly fierce one. There were seventy people in the school orchestra. Fifty of these were also in the school choir and twenty of those fifty were in the school play. Thirty boys in the orchestra were in various football teams, and twenty of the girls played hockey for the school. At least a third played basketball as well. The volleyball team were all in the school play. Problem: how do you arrange rehearsals and practices without asking most people to be in three places at once? Mr Wentworth rubbed the thin patch at the back of his hair despairingly.

“Come in,” he said. He saw the bright, smiling, anxious face of Miss Hodge, but his mind was not on her at all.

“So spiteful of someone, and so awful if it’s true!” he heard Miss Hodge saying. And then, merrily, “But I think I have a scheme to discover who wrote the note – it must be someone in 2Y. Can we put our heads together and work it out, Mr Wentworth?” She put her own head on one side, invitingly.

Mr Wentworth had no idea what she was talking about. He scratched the place where his hair was going and stared at her. Whatever it was, it had all the marks of a scheme that ought to be squashed. “People only write anonymous notes to make themselves feel important,” he said experimentally. “You mustn’t take them seriously.”

“But it’s the perfect scheme!” Miss Hodge protested. “If I can explain—”

Not squashed yet, whatever it is, thought Mr Wentworth. “No. Just tell me the exact words of this note,” he said.

Miss Hodge instantly became crushed and shocked. “But it’s awful!” Her voice fell to a dramatic whisper. “It says someone in 2Y is a witch!”

Mr Wentworth realised that his instinct had been right. “What did I tell you?” he said heartily. “That’s the sort of stuff you can only ignore, Miss Hodge.”

“But someone in 2Y has a very sick mind!” Miss Hodge whispered.

Mr Wentworth considered 2Y, including his own son Brian. “They all have,” he said. “Either they’ll grow out of it, or we’ll see them all riding round on broomsticks in the sixth form.” Miss Hodge started back. She was genuinely shocked at this coarse language. But she hastily made herself laugh. She could see it was a joke. “Take no notice,” said Mr Wentworth. “Ignore it, Miss Hodge.” And he went back to his problem with some relief.

Miss Hodge went back to her stacks of books, not as crushed as Mr Wentworth supposed she was. Mr Wentworth had made a joke to her. He had never done that before. She must be getting somewhere. For – and this was a fact not known to Theresa Mullett or Estelle Green – Miss Hodge intended to marry Mr Wentworth. He was a widower. When Miss Cadwallader retired, Miss Hodge was sure Mr Wentworth would be Head of Larwood House. This suited Miss Hodge, who had her old father to consider. For this, she was quite willing to put up with Mr Wentworth’s bald patch and his tense and harrowed look. The only drawback was that putting up with Mr Wentworth also meant putting up with Brian. A little frown wrinkled Miss Hodge’s smooth forehead at the thought of Brian Wentworth. Now there was a boy who quite deserved the way the rest of 2Y were always on to him. Never mind. He could be sent away to another school.

Meanwhile, in Music, Mr Brubeck was asking Brian to sing on his own. 2Y had trailed their way through ‘Here we sit like birds in the wilderness’. They had made it sound like a lament. “I’d prefer a wilderness to this place,” Estelle Green whispered to her friend Karen Grigg. Then they sang ‘Cuckaburra sits in the old gum tree’. That sounded like a funeral dirge.

“What’s a cuckaburra?” Karen whispered to Estelle.

“Another kind of bird,” Estelle whispered back. “Australian.”

“No, no, no!” shouted Mr Brubeck. “Brian is the only one of you who doesn’t sound like a cockerel with a sore throat!”

“Mr Brubeck must have birds on the brain!” Estelle giggled. And Simon Silverson, who believed, strongly and sincerely, that nobody was worthy of praise except himself, gave Brian a scathingly jeering look.

But Mr Brubeck was far too addicted to music to take any notice of what the rest of 2Y thought. “‘The Cuckoo is a Pretty Bird’,” he announced. “I want Brian to sing this to you on his own.”

Estelle giggled, because it was birds again. Theresa giggled too, because anyone who stood out for any reason struck her as exceedingly funny. Brian stood up with the song book in his hands. He was never embarrassed. But instead of singing, he read the words out in an incredulous voice.

“‘The cuckoo is a pretty bird, she singeth as she flies. She bringeth us good tidings, she telleth us no lies.’ Sir, why are all these songs about birds?” he asked innocently. Charles thought that was a shrewd move of Brian’s, after the way Simon Silverson had looked at him.

But it did Brian no good. He was too unpopular. Most of the girls said, “Brian!” in shocked voices. Simon said it jeeringly.

“Quiet!” shouted Mr Brubeck. “Brian, get on and sing!” He struck notes on the piano.

Brian stood with the book in his hands, obviously wondering what to do. It was clear that he would be in trouble with Mr Brubeck if he did not sing, and that he would be hit afterwards if he did. And while Brian hesitated, the witch in 2Y took a hand. One of the long windows of the hall flew open with a clap and let in a stream of birds. Most of them were ordinary birds: sparrows, starlings, pigeons, blackbirds and thrushes, swooping round the hall in vast numbers and shedding feathers and droppings as they swooped. But among the beating wings were two curious furry creatures with large pouches, which kept uttering violent laughing sounds, and the red and yellow thing swooping among a cloud of sparrows and shouting “Cuckoo!” was clearly a parrot.

Luckily, Mr Brubeck thought it was simply the wind which had let the birds in. The rest of the lesson had to be spent in chasing the birds out again. By that time, the laughing birds with pouches had vanished. Evidently the witch had decided they were a mistake. But everyone in 2Y had clearly seen them. Simon said importantly, “If this happens again, we all ought to get together and—”

At this, Nirupam Singh turned round, towering among the beating wings. “Have you any proof that this is not perfectly natural?” he said.

Simon had not, so he said no more.

By the end of the lesson, all the birds had been sent out of the window again, except the parrot. The parrot escaped to a high curtain rail, where no one could reach it, and sat there shouting “Cuckoo!” Mr Brubeck sent 2Y away and called the caretaker to get rid of it. Charles trudged away with the rest, thinking that this must be the end of the Games he had predicted in his journal. But he was quite wrong. It was only the beginning.

And when the caretaker came grumbling along with his small white dog trailing at his heels, to get rid of the parrot, the parrot had vanished.

CHAPTER TWO (#u69483a27-a89e-5ee5-a135-aa68f23603ac)

The next day was the day Miss Hodge tried to find out who had written the note. It was also the worst day either Nan Pilgrim or Charles Morgan had ever spent at Larwood House. It did not begin too badly for Charles, but Nan was late for breakfast.

She had broken her shoelace. She was told off by Mr Towers for being late, and then by a prefect. By this time, the only table with a place was one where all the others were boys. Nan slid into place, horribly embarrassed. They had eaten all the toast already, except one slice. Simon Silverson took the slice as Nan arrived. “Bad luck, fatso.” From further down the table, Nan saw Charles Morgan looking at her. It was meant to be a look of sympathy, but, like all Charles’s looks, it came out like a blank double-barrelled glare. Nan pretended not to see it and did her best to eat wet, pale scrambled egg on its own.

At lessons, she discovered that Theresa and her friends had started a new craze. That was a bad sign. They were always more than usually pleased with themselves at the start of a craze – even though this one had probably started so that they need not think of witches or birds. The craze was white knitting, white and clean and fluffy, which you kept wrapped in a towel so that it would stay clean. The classroom filled with mutters of, “Two purl, one plain, twist two . . .”

But the day really got into its evil stride in the middle of the morning, during PE. Larwood House had that every day, like the journals. 2Y joined with 2X and 2Z, and the boys went running in the field, while the girls went together to the Gym. The climbing-ropes were let down there.

Theresa and Estelle and the rest gave glad cries and went shinning up the ropes with easy swinging pulls. Nan tried to lurk out of sight against the wall-bars. Her heart fell with a flop into her gym shoes. This was worse even than the vaulting-horse. Nan simply could not climb ropes. She had been born without the proper muscles or something.

And, since it was that kind of day, Miss Phillips spotted Nan almost at once. “Nan, you haven’t had a turn yet. Theresa, Delia, Estelle, come on down and let Nan have her turn on the ropes.” Theresa and the rest came down readily. They knew they were about to see some fun.

Nan saw their faces and ground her teeth. This time, she vowed, she would do it. She would climb right up to the ceiling and wipe that grin off Theresa’s face. Nevertheless, the distance to the ropes seemed several hundred shiny yards. Nan’s legs, in the floppy divided skirts they wore for Gym, had gone mauve and wide, and her arms felt like weak pink puddings. When she reached the rope, the knot on the end of it seemed to hang rather higher than her head. And she was supposed to stand on that knot somehow.

She gripped the rope in her fat, weak hands and jumped. All that happened was that the knot hit her heavily in the chest and her feet dropped sharply to the floor again. A murmur of amusement began among Theresa and her friends. Nan could hardly believe it. This was ridiculous – worse than usual! She could not even get off the floor now. She took a new grip on the rope and jumped again. And again. And again. And she leapt and leapt, bounding like a floppy kangaroo, and still the knot kept hitting her in the chest and her feet kept hitting the floor. The murmurs of the rest grew into giggles and then to outright laughter. Until at last, when Nan was almost ready to give up, her feet somehow found the knot, groped, gripped and hung on. And there she clung, upside down like a sloth, breathless and sweating, from arms which did not seem to work any more. This was terrible. And she still had to climb up the rope. She wondered whether to fall off on her back and die.

Miss Phillips was beside her. “Come on, Nan. Stand up on the knot.”

Somehow, feeling it was superhuman of her, Nan managed to lever herself upright. She stood there, wobbling gently round in little circles, while Miss Phillips, with her face level with Nan’s trembling knees, kindly and patiently explained for the hundredth time exactly how to climb a rope.

Nan clenched her teeth. She would do it. Everyone else did. It must be possible. She shut her eyes to shut out the other girls’ grinning faces and did as Miss Phillips told her. She took a strong and careful grip on the rope above her head. Carefully, she put rope between the top of one foot and the bottom of the other. She kept her eyes shut. Firmly, she pulled with her arms. Crisply, she pulled her feet up behind. Gripped again. Reached up again, with fearful concentration. Yes, this was it! She was doing it at last! The secret must be to keep your eyes shut. She gripped and pulled. She could feel her body easily swinging upwards towards the ceiling, just as the others did it.

But, around her, the giggles grew to laughter, and the laughter grew into screams, then shouts, and became a perfect storm of hilarity. Puzzled, Nan opened her eyes. All round her, at knee-level, she saw laughing red faces, tears running out of eyes, and people doubled over yelling with mirth. Even Miss Phillips was biting her lip and snorting a little. And small wonder. Nan looked down to find her gym shoes still resting on the knot at the bottom of the rope. After all that climbing, she was still standing on the knot.

Nan tried to laugh too. She was sure it had been very funny. But it was hard to be amused. Her only consolation was that, after that, none of the other girls could climb the ropes either. They were too weak with laughing.

The boys, meanwhile, were running round and round the field. They were stripped to little pale-blue running shorts and splashing through the dew in big spiked shoes. It was against the rules to run in anything but spikes. They were divided into little groups of labouring legs. The quick group of legs in front, with muscles, belonged to Simon Silverson and his friends, and to Brian Wentworth. Brian was a good runner in spite of his short legs. Brian was prudently trying to keep to the rear of Simon, but every so often the sheer joy of running overcame him and he went ahead. Then he would get bumped and jostled by Simon’s friends, for everyone knew it was Simon’s right to be in front.

The group of legs behind these were paler and moved without enthusiasm. These belonged to Dan Smith and his friends. All of them could have run at least as fast as Simon Silverson, but they were saving themselves for better things. They loped along easily, chatting among themselves. Today, they kept bursting into laughter.

Behind these again laboured an assorted group of legs: mauve legs, fat legs, bright white legs, legs with no muscles at all, and the great brown legs of Nirupam Singh, which seemed too heavy for the rest of Nirupam’s skinny body to lift. Everyone in this group was too breathless to talk. Their faces wore assorted expressions of woe.

The last pair of legs, far in the rear, belonged to Charles Morgan. There was nothing particularly wrong with Charles’s legs, except that his feet were in ordinary school shoes and soaked through. He was always behind. He chose to be. This was one of the few times in the day when he could be alone to think. He had discovered that, as long as he was thinking of something else, he could keep up his slow trot for hours. And think. The only interruptions he had to fear were when the other groups came pounding past him and he was tangled up in their efforts for a few seconds. Or when Mr Towers, encased in his nice warm tracksuit, came loping up alongside and called ill-advised encouragements to Charles.

So Charles trotted slowly on, thinking. He gave himself over to hating Larwood House. He hated the field under his feet, the shivering autumn trees that dripped on him, the white goalposts, and the neat line of pine trees in front of the spiked wall that kept everyone in. Then, when he swung round the corner and had a view of the school buildings, he hated them more. They were built of a purplish sort of brick. Charles thought it was the colour a person’s face would go if they were throttling. He thought of the long corridors inside, painted caterpillar green, the thick radiators which were never warm, the brown classrooms, the frosty white dormitories, and the smell of school food, and he was almost in an ecstasy of hate. Then he looked at the groups of legs straggling round the field ahead, and he hated all the people in the school most horribly of all.

Upon that, he found he was remembering the witch being burnt. It swept into his head unbidden, as it always did. Only today, it seemed worse than usual. Charles found he was remembering things he had not noticed at the time: the exact shape of the flames, just leaping from small to large, and the way the fat man who was a witch had bent sideways away from them. He could see the man’s exact face, the rather blobby nose with a wart on it, the sweat on it, and the flames shining off the man’s eyes and the sweat. Above all, he could see the man’s expression. It was astounded. The fat man had not believed he was going to die until the moment Charles saw him. He must have thought his witchcraft could save him. Now he knew it could not. And he was horrified. Charles was horrified too. He trotted along in a sort of trance of horror.

But here was the smart red tracksuit of Mr Towers loping along beside him. “Charles, what are you doing running in walking shoes?”

The fat witch vanished. Charles should have been glad, but he was not. His thinking had been interrupted, and he was not private any more.

“I said why aren’t you wearing your spikes?” Mr Towers said.

Charles slowed down a little while he wondered what to reply. Mr Towers trotted springily beside him, waiting for an answer. Because he was not thinking any more, Charles found his legs aching and his chest sore. That annoyed him. He was even more annoyed about his spikes. He knew Dan Smith had hidden them. That was why that group were laughing. Charles could see their faces craning over their shoulders as they ran, to see what he was telling Mr Towers. That annoyed him even more. Charles did not usually have this kind of trouble, the way Brian Wentworth did. His double-barrelled nasty look had kept him safe up to now, if lonely. But he foresaw he was going to have to think of something more than just looking in future. He felt very bitter.

“I couldn’t find my spikes, sir.”

“How hard did you look?”

“Everywhere,” Charles said bitterly. Why don’t I say it was them? he wondered. And knew the answer. Life would not be worth living for the rest of term.

“In my experience,” said Mr Towers, running and talking as easily as if he were sitting still, “when a lazy boy like you says everywhere, it means nowhere. Report to me in the locker room after school and find those spikes. You stay there until you find them. Right?”

“Yes,” said Charles. Bitterly, he watched Mr Towers surge away from him and run up beside the next group to pester Nirupam Singh.

He hunted for his spikes again during break. But it was hopeless. Dan had hidden them somewhere really cunning. At least, after break, Dan Smith had something else to laugh about beside Charles. Nan Pilgrim soon found out what. As Nan came into the classroom for lessons, she was greeted by Nirupam. “Hallo,” asked Nirupam. “Will you do your rope trick for me too?”

Nan gave him a glare that was mostly astonishment and pushed past him without replying. How did he know about the ropes? she thought. The girls just never talked to the boys! How did he know?

But next moment, Simon Silverson came up to Nan, barely able to stop laughing. “My dear Dulcinea!” he said. “What a charming name you have! Were you called after the Archwitch?” After that, he doubled up with laughter, and so did most of the people near.

“Her name really is Dulcinea, you know,” Nirupam said to Charles.

This was true. Nan’s face felt to her like a balloon on fire. Nothing else, she was sure, could be so large and so hot. Dulcinea Wilkes had been the most famous witch of all time. No one was supposed to know Nan’s name was Dulcinea. She could not think how it had leaked out. She tried to stalk loftily away to her desk, but she was caught by person after person, all laughingly calling out, “Hey, Dulcinea!” She did not manage to sit down until Mr Wentworth was already in the room.

2Y usually attended during Mr Wentworth’s lessons. He was known to be absolutely merciless. Besides, he had a knack of being interesting, which made his lessons seem shorter than other teachers’. But today, no one could keep their mind on Mr Wentworth. Nan was trying not to cry.

When, a year ago, Nan’s aunts had brought her to Larwood House, even softer, plumper and more timid than she was now, Miss Cadwallader had promised that no one should know her name was Dulcinea. Miss Cadwallader had promised! So how had someone found out? The rest of 2Y kept breaking into laughter and excited whispers. Could Nan Pilgrim be a witch? Fancy anyone being called Dulcinea! It was as bad as being called Guy Fawkes! Halfway through the lesson, Theresa Mullett was so overcome by the thought of Nan’s name that she was forced to bury her face in her knitting to laugh.

Mr Wentworth promptly took the knitting away. He dumped the clean white bundle on the desk in front of him and inspected it dubiously. “What is it about this that seems so funny?” He unrolled the towel – at which Theresa gave a faint yell of dismay – and held up a very small fluffy thing with holes in it. “Just what is this?”

Everyone laughed.

“It’s a bootee!” Theresa said angrily.

“Who for?” retorted Mr Wentworth.

Everyone laughed again. But the laughter was short and guilty, because everyone knew Theresa was not to be laughed at.

Mr Wentworth seemed unaware that he had performed a miracle and made everyone laugh at Theresa, instead of the other way round. He cut the laughter even shorter by telling Dan Smith to come out to the blackboard and show him two triangles that were alike. The lesson went on. Theresa kept muttering, “It’s not funny! It’s just not funny!” Every time she said it, her friends nodded sympathetically, while the rest of the class kept looking at Nan and bursting into muffled laughter.

At the end of the lesson, Mr Wentworth uttered a few unpleasant remarks about mass punishments if people behaved like this again. Then, as he turned to leave, he said, “And by the way, if Charles Morgan, Nan Pilgrim and Nirupam Singh haven’t already looked at the main notice board, they should do so at once. They will find they are down for lunch on high table.”

Both Nan and Charles knew then that this was not just a bad day – it was the worst day ever. Miss Cadwallader sat at high table with any important visitors to the school. It was her custom to choose three pupils from the school every day to sit there with her. This was so that everyone should learn proper table manners, and so that Miss Cadwallader should get to know her pupils. It was rightly considered a terrible ordeal. Neither Nan nor Charles had ever been chosen before. Scarcely able to believe it, they went to check with the notice board. Sure enough it read: Charles Morgan 2Y, Dulcinea Pilgrim 2Y, Nirupam Singh 2Y.

Nan stared at it. So that was how everyone knew her name! Miss Cadwallader had forgotten. She had forgotten who Nan was and everything she had promised, and when she came to stick a pin in the register – or whatever she did to choose people for high table – she had simply written down the names that came under her pin.

Nirupam was looking at the notice too. He had been chosen before, but he was no less gloomy than Charles or Nan.

“You have to comb your hair and get your blazer clean,” he said. “And it really is true you have to eat with the same kind of knife or fork that Miss Cadwallader does. You have to watch and see what she uses all the time.”

Nan stood there, letting other people looking at the notices push her about. She was terrified. She suddenly knew she was going to behave very badly on high table. She was going to drop her dinner, or scream, or maybe take all her clothes off and dance among the plates. And she was terrified, because she knew she was not going to be able to stop herself.

She was still terrified when she arrived at high table with Charles and Nirupam. They had all combed their heads sore and tried to clean from the fronts of their blazers the dirt which always mysteriously arrives on the fronts of blazers, but they all felt grubby and small beside the stately company at high table. There were a number of teachers, and the Bursar, and an important-looking man called Lord Something-or-other, and tall, stringy Miss Cadwallader herself.

Miss Cadwallader smiled at them graciously and pointed to three empty chairs at her left side. All of them instantly dived for the chair furthest away from Miss Cadwallader. Nan, much to her surprise, won it, and Charles won the chair in the middle, leaving Nirupam to sit beside Miss Cadwallader.

“Now we know that won’t do, don’t we?” said Miss Cadwallader. “We always sit with a gentleman on either side of a lady, don’t we? Dulcimer must sit in the middle, and I’ll have the gentleman I haven’t yet met nearest me. Clive Morgan, isn’t it? That’s right.”

Sullenly, Charles and Nan changed their places. They stood there, while Miss Cadwallader was saying grace, looking out over the heads of the rest of the school, not very far below, but far enough to make a lot of difference. Perhaps I’m going to faint, Nan thought hopefully. She still knew she was going to behave badly, but she felt very odd as well – and fainting was a fairly respectable way of behaving badly.

She was still conscious at the end of grace. She sat down with the rest, between the glowering Charles and Nirupam. Nirupam had gone pale yellow with dread. To their relief, Miss Cadwallader at once turned to the important lord and began making gracious conversation with him. The ladies from the kitchen brought round a tray of little bowls and handed everybody one.

What was this? It was certainly not a usual part of school dinner. They looked suspiciously at the bowls. They were full of yellow stuff, not quite covering little pink things.

“I believe it may be prawns,” Nirupam said dubiously. “For a starter.”

Here Miss Cadwallader reached forth a gracious hand. Their heads at once craned round to see what implement she was going to eat out of the bowl with. Her hand picked up a fork. They picked up forks too. Nan poked hers cautiously into her bowl. Instantly she began to behave badly. She could not stop herself. “I think it’s custard,” she said loudly. “Do prawns mix with custard?” She put one of the pink things into her mouth. It felt rubbery. “Chewing gum?” she asked. “No, I think they’re jointed worms. Worms in custard.”

“Shut up!” hissed Nirupam.

“But it’s not custard,” Nan continued. She could hear her voice saying it, but there seemed no way to stop it. “The tongue-test proves that the yellow stuff has a strong taste of sour armpits, combined with – yes – just a touch of old drains. It comes from the bottom of a dustbin.”

Charles glared at her. He felt sick. If he had dared, he would have stopped eating at once. But Miss Cadwallader continued gracefully forking up prawns – unless they really were jointed worms – and Charles did not dare do differently. He wondered how he was going to put this in his journal. He had never hated Nan Pilgrim particularly before, so he had no code-word for her. Prawn? Could he call her prawn? He choked down another worm – prawn, that was – and wished he could push the whole bowlful in Nan’s face.

“A clean yellow dustbin,” Nan announced. “The kind they keep the dead fish for Biology in.”

“Prawns are eaten curried in India,” Nirupam said loudly.

Nan knew he was trying to shut her up. With a great effort, by cramming several forkfuls of worms – prawns, that was – into her mouth at once, she managed to stop herself talking. She could hardly bring herself to swallow the mouthful, but at least it kept her quiet. Most fervently, she hoped that the next course would be something ordinary, which she would not have any urge to describe, and so did Nirupam and Charles.

But alas! What came before them in platefuls next was one of the school kitchen’s more peculiar dishes. They produced it about once a month and its official name was hot-pot. With it came tinned peas and tinned tomatoes. Charles’s head and Nirupam’s craned towards Miss Cadwallader again to see what they were supposed to eat this with. Miss Cadwallader picked up a fork. They picked up forks too, and then craned a second time, to make sure that Miss Cadwallader was not going to pick up a knife as well and so make it easier for everyone. She was not. Her fork drove gracefully under a pile of tinned peas. They sighed, and found both their heads turning towards Nan then in a sort of horrified expectation.

They were not disappointed. As Nan levered loose the first greasy ring of potato, the urge to describe came upon her again. It was as if she was possessed.

“Now the aim of this dish,” she said, “is to use up leftovers. You take old potatoes and soak them in washing-up water that has been used at least twice. The water must be thoroughly scummy.” It’s like the gift of tongues! she thought. Only in my case it’s the gift of foul-mouth. “Then you take a dirty old tin and rub it round with socks that have been worn for a fortnight. You fill this tin with alternate layers of scummy potatoes and cat-food, mixed with anything else you happen to have. Old doughnuts and dead flies have been used in this case—”

Could his code-word for Nan be hot-pot? Charles wondered. It suited her. No, because they only had hot-pot once a month – fortunately – and, at this rate, he would need to hate Nan practically every day. Why didn’t someone stop her? Couldn’t Miss Cadwallader hear?

“Now these things,” Nan continued, stabbing her fork into a tinned tomato, “are small creatures that have been killed and cleverly skinned. Notice, when you taste them, the slight, sweet savour of their blood—”

Nirupam uttered a small moan and went yellower than ever.

The sound made Nan look up. Hitherto, she had been staring at the table where her plate was, in a daze of terror. Now she saw Mr Wentworth sitting opposite her across the table. He could hear her perfectly. She could tell from the expression on his face. Why doesn’t he stop me? she thought. Why do they let me go on? Why doesn’t somebody do something, like a thunderbolt strike me, or eternal detention? Why don’t I get under the table and crawl away? And, all the time, she could hear herself talking. “These did in fact start life as peas. But they have since undergone a long and deadly process. They lie for six months in a sewer, absorbing fluids and rich tastes, which is why they are called processed peas. Then—”

Here, Miss Cadwallader turned gracefully to them. Nan, to her utter relief, stopped in mid-sentence. “You have all been long enough in the school by now,” Miss Cadwallader said, “to know the town quite well. Do you know that lovely old house in the High Street?”

They all three stared at her. Charles gulped down a ring of potato. “Lovely old house?”

“It’s called the Old Gate House,” said Miss Cadwallader. “It used to be part of the gate in the old town wall. A very lovely old brick building.”

“You mean the one with a tower on top and windows like a church?” Charles asked, though he could not think why Miss Cadwallader should talk of this and not processed peas.

“That’s the one,” said Miss Cadwallader. “And it’s such a shame. It’s going to be pulled down to make way for a supermarket. You know it has a king-pin roof, don’t you?”

“Oh,” said Charles. “Has it?”

“And a queen-pin,” said Miss Cadwallader.

Charles seemed to have got saddled with the conversation. Nirupam was happy enough not to talk, and Nan dared do no more than nod intelligently, in case she started describing the food again. As Miss Cadwallader talked, and Charles was forced to answer while trying to eat tinned tomatoes – no, they were not skinned mice! – using just a fork, Charles began to feel he was undergoing a particularly refined form of torture.

He realised he needed a hate-word for Miss Cadwallader too. Hot-pot would do for her. Surely nothing as awful as this could happen to him more than once a month? But that meant he had still not got a code-word for Nan.

They took the hot-pot away. Charles had not eaten much. Miss Cadwallader continued to talk to him about houses in the town, then about stately homes in the country, until the pudding arrived. It was set before Charles, white and bleak and swimming, with little white grains in it like the corpses of ants – Lord, he was getting as bad as Nan Pilgrim! Then he realised it was the ideal word for Nan.

“Rice pudding!” he exclaimed.

“It is agreeable,” Miss Cadwallader said, smiling. “And so nourishing.” Then, incredibly, she reached to the top of her plate and picked up a fork. Charles stared. He waited. Surely Miss Cadwallader was not going to eat runny rice pudding with just a fork? But she was. She dipped the fork in and brought it up, raining weak white milk.

Slowly, Charles picked up a fork too and turned to meet Nan’s and Nirupam’s incredulous faces. It was just not possible.

Nirupam looked wretchedly down at his brimming plate. “There is a story in the Arabian Nights,” he said, “about a woman who ate rice with a pin, grain by grain.” Charles shot a terrified look at Miss Cadwallader, but she was talking to the lord again. “She turned out to be a ghoul,” Nirupam said. “She ate her fill of corpses every night.”

Charles’s terrified look shot to Nan instead. “Shut up, you fool! You’ll set her off again!”

But the possession seemed to have left Nan by then. She was able to whisper, with her head bent over her plate so that only the boys could hear, “Mr Wentworth’s using his spoon. Look.”

“Do you think we dare?” said Nirupam.

“I’m going to,” said Charles. “I’m hungry.”

So they all used their spoons. When the meal was at last over, they were all dismayed to find Mr Wentworth beckoning. But it was only Nan he was beckoning. When she came reluctantly over, he said, “See me at four in my study.” Which was, Nan felt, all she needed. And the day was still only half over.

CHAPTER THREE (#u69483a27-a89e-5ee5-a135-aa68f23603ac)

That afternoon, Nan came into the classroom to find a besom laid across her desk. It was an old tatty broom, with only the bare minimum of twigs left in the brush end, which the groundsman sometimes used to sweep the paths. Someone had brought it in from the groundsman’s shed. Someone had tied a label to the handle: Dulcinea’s Pony. Nan recognised the round, angelic writing as Theresa’s.

Amid sniggers and titters, she looked round the assembled faces. Theresa would not have thought of stealing a broom on her own. Estelle? No. Neither Estelle nor Karen Grigg was there. No, it was Dan Smith, by the look on his face. Then she looked at Simon Silverson and was not so sure. It could not have been both of them because they never, ever did anything together.

Simon said to her, in his suavest manner, grinning all over his face, “Why don’t you hop on and have a ride, Dulcinea?”

“Yes, go on. Ride it, Dulcinea,” said Dan.

Next moment, everyone else was laughing and yelling at her to ride the broom. And Brian Wentworth, who was only too ready to torment other people when he was not being a victim himself, was leaping up and down in the gangway between the desks, screaming, “Ride, Dulcinea! Ride!”

Slowly, Nan picked up the broom. She was a mild and peaceable person who seldom lost her temper – perhaps that was her trouble – but when she did lose it, there was no knowing what she would do. As she picked up the broom, she thought she just meant to stand it haughtily against the wall. But, as her hands closed round its knobby handle, her temper left her completely. She turned round on the jeering, hooting crowd, filled with roaring rage. She lifted the broom high above her head and bared her teeth. Everyone thought that was funnier than ever.

Nan meant to smash the broom through Simon Silverson’s laughing face. She meant to bash in Dan Smith’s head. But, since Brian Wentworth was dancing and shrieking and making faces just in front of her, it was Brian she went for. Luckily for him, he saw the broom coming down and leapt clear. After that, he was forced to back away up the gangway and then into the space by the door, with his arms over his head, screaming for mercy, while Nan followed him, bashing like a madwoman.

“Help! Stop her!” Brian screamed, and backed into the door just as Miss Hodge came through it carrying a large pile of English books. Brian backed into her and sat down at her feet in a shower of books. “Ow!” he yelled.

“What is going on?” said Miss Hodge.

The uproar in the room was cut off as if with a switch. “Get up, Brian,” Simon Silverson said righteously. “It was your own fault for teasing Nan Pilgrim.”

“Really! Nan!” said Theresa. She was genuinely shocked. “Temper, temper!”

At that, Nan nearly went for Theresa with the broom. Theresa was only saved by the fortunate arrival of Estelle Green and Karen Grigg. They came scurrying in with their heads guiltily lowered and their arms wrapped round bulky bags of knitting wool. “Sorry we’re late, Miss Hodge,” Estelle panted. “We had permission to go shopping.”

Nan’s attention was distracted. The wool in the bags was fluffy and white, just like Theresa’s. Why on earth, Nan wondered scornfully, did everyone have to imitate Theresa?

Miss Hodge took the broom out of Nan’s unresisting hands and propped it neatly behind the door. “Sit down, all of you,” she said. She was very put out. She had intended to come quietly into a nice quiet classroom and galvanise 2Y by confronting them with her scheme. And here they were galvanised already, and with a witch’s broom. There was clearly no chance of catching the writer of the note or the witch by surprise. Still, she did not like to let a good scheme go to waste.

“I thought we would have a change today,” she said, when everyone was settled. “Our poetry book doesn’t seem to be going down very well, does it?” She looked brightly round the class. 2Y looked back cautiously. Some of them felt anything would be better than being asked to find poems beautiful. Some of them felt it depended on what Miss Hodge intended to do instead. Of the rest, Nan was trying not to cry, Brian was licking a scratch on his arm, and Charles was glowering. Charles liked poetry because the lines were so short. You could think your own thoughts in the spaces round the print.

“Today,” said Miss Hodge, “I want you all to do something yourselves.”

Everyone recoiled. Estelle put her hand up. “Please, Miss Hodge. I don’t know how to write poems.”

“Oh, I don’t want you to do that,” said Miss Hodge. Everyone relaxed. “I want you to act out some little plays for me.” Everyone recoiled again. Miss Hodge took no notice and explained that she was going to call them out to the front in pairs, a boy and a girl in each, and every pair was going to act out the same short scene. “That way,” she said, “we shall have fifteen different pocket dramas.”

By this time, most of 2Y were staring at her in wordless despair. Miss Hodge smiled warmly and prepared to galvanise them. Really, she thought, her scheme might go quite well after all.

“Now, we must choose a subject for our playlets. It has to be something strong and striking, with passionate possibilities. Suppose we act a pair of lovers saying good bye?” Somebody groaned, as Miss Hodge had known somebody would. “Very well. Who has a suggestion?”

Theresa’s hand was up, and Dan Smith’s.

“A television star and her admirer,” said Theresa.

“A murderer and a policeman making him confess,” said Dan. “Are we allowed torture?”

“No, we are not,” said Miss Hodge, at which Dan lost interest. “Anyone else?”

Nirupam raised a long thin arm. “A salesman deceiving a lady over a car.”

Well, Miss Hodge thought, she had not really expected anyone to make a suggestion that would give them away. She pretended to consider. “We-ell, so far the most dramatic suggestion is Dan’s. But I had in mind something really tense, which we all know about quite well.”

“We all know about murder,” Dan protested.

“Yes,” said Miss Hodge. She was watching everyone like a hawk now. “But we know even more about stealing, say, or lying, or witchcraft, or—” She let herself notice the broomstick again, with a start of surprise. It came in handy after all. “I know! Let us suppose that one of the people in our little play is suspected of being a witch, and the other is an Inquisitor. How about that?”

Nothing. Not a soul in 2Y reacted, except Dan. “That’s the same as my idea,” he grumbled. “And it’s no fun without torture.”

Miss Hodge made Dan into suspect number one at once. “Then you begin, Dan,” she said, “with Theresa. Which are you, Theresa – witch or Inquisitor?”

“Inquisitor, Miss Hodge,” Theresa said promptly.

“It’s not fair!” said Dan. “I don’t know what witches do!”

Nor did he, it was clear. And it was equally clear that Theresa had no more idea what Inquisitors did. They stood woodenly by the blackboard. Dan stared at the ceiling, while Theresa stated, “You are a witch.” Whereupon Dan told the ceiling, “No I am not.” And they went on doing this until Miss Hodge told them to stop. Regretfully, she demoted Dan from first suspect to last, and put Theresa down there with him, and called up the next pair.

Nobody behaved suspiciously. Most people’s idea was to get the acting over as quickly as possible. Some argued a little, for the look of the thing. Others tried running about to make things seem dramatic. And first prize for brevity certainly went to Simon Silverson and Karen Grigg. Simon said, “I know you’re a witch, so don’t argue.”

And Karen replied, “Yes I am. I give in. Let’s stop now.”

By the time it came to Nirupam, Miss Hodge’s list of suspects was all bottom and no top. Then Nirupam put on a terrifying performance as Inquisitor. His eyes blazed. His voice alternately roared and fell to a sinister whisper. He pointed fiercely at Estelle’s face.

“Look at your evil eyes!” he bellowed. Then he whispered, “I see you, I feel you, I know you – you are a witch!” Estelle was so frightened that she gave a real performance of terrified innocence.

But Brian Wentworth’s performance as a witch outshone even Nirupam. Brian wept, he cringed, he made obviously false excuses, and he ended kneeling at Delia Martin’s feet, sobbing for mercy and crying real tears.

Everyone was astonished, including Miss Hodge. She would dearly have liked to put Brian at the top of her list of suspects, either as the witch or the one who wrote the note. But how bothersome for her plans if she had to go to Mr Wentworth and say it was Brian. No, she decided. There was no genuine feeling in Brian’s performance, and the same went for Nirupam. They were both just good actors.

Then it was the turn of Charles and Nan. Charles had seen it coming for some time now, that he would be paired with Nan. He was very annoyed. He seemed to be haunted by her today. But he did not intend to let that stop his performance being a triumph of comic acting. He was depressed by the lack of invention everyone except Nirupam had shown. Nobody had thought of making the Inquisitor funny. “I’ll be Inquisitor,” he said quickly.

But Nan was still smarting after the broomstick. She thought Charles was getting at her and glared at him. Charles, on principle, never let anyone glare at him without giving his nastiest double-barrelled stare in return. So they shuffled to the front of the class looking daggers at one another.

There Charles beat at his forehead. “Emergency!” he exclaimed. “There are no witches for the autumn bone-fires. I shall have to find an ordinary person instead.” He pointed at Nan. “You’ll do,” he said. “Starting from now, you’re a witch.”

Nan had not realised that the acting had begun. Besides, she was too hurt and angry to care. “Oh, no I’m not!” she snapped. “Why shouldn’t you be the witch?”

“Because I can prove you’re a witch,” Charles said, trying to stick to his part. “Being an Inquisitor, I can prove anything.”

“In that case,” said Nan, angrily ignoring this fine acting, “we’ll both be Inquisitors, and I’ll prove you’re a witch too! Why not? You have four of the most evil eyes I ever saw. And your feet smell.”

All eyes turned to Charles’s feet. Since he had been forced to run round the field in the shoes he was wearing now, they were still rather wet. And, being warmed through, they were indeed exuding a slight but definite smell.

“Cheese,” murmured Simon Silverson.

Charles looked angrily down at his shoes. Nan had reminded him that he was in trouble over his missing running shoes. And she had spoilt his acting. He hated her. He was in an ecstasy of hate again. “Worms and custard and dead mice!” he said. Everyone stared at him, mystified. “Tinned peas soaked in sewage!” Charles said, beside himself with hatred. “Potatoes in scum. I’m not surprised your name’s Dulcinea. It suits you. You’re quite disgusting!”

“And so are you!” Nan shouted back at him. “I bet it was you who did those birds in Music yesterday!” This caused shocked gasps from the rest of 2Y.

Miss Hodge listened, fascinated. This was real feeling all right. And what had Charles said? It was clear to her now why the rest of 2Y had clustered so depressingly at the bottom of her list of suspects. Nan and Charles were at the top of it. It was obvious. They were always the odd ones out in 2Y. Nan must have written the note, and Charles must be the witch in question. And now let Mr Wentworth pour scorn on her scheme!

“Please, Miss Hodge, the bell’s gone,” called a number of voices.

The door opened and Mr Crossley came in. When he saw Miss Hodge, which he had come early in order to do, his face became a deep red, most interesting to Estelle and Theresa.

“Am I interrupting a lesson, Miss Hodge?”

“Not at all,” said Miss Hodge. “We had just finished. Nan and Charles go back to your places.” And she swept out of the room, without appearing to notice that Mr Crossley had leapt to hold the door open for her.

Miss Hodge hurried straight upstairs to Mr Wentworth’s study. She knew this news was going to make an impression on him. But there, to her annoyance, was Mr Wentworth dashing downstairs with a box of chalk, very late for a lesson with 3Z.

“Oh, Mr Wentworth,” panted Miss Hodge. “Can you spare a moment?”

“Not a second. Write me a memo if it’s urgent,” said Mr Wentworth, dashing on down.

Miss Hodge reached out and seized his arm. “But you must! You know 2Y and my scheme about the anonymous note—”

Mr Wentworth swung round on the end of her clutching hands and looked up at her irritably. “What about what anonymous note?”

“My scheme worked!” Miss Hodge said. “Nan Pilgrim wrote it, I’m sure. You must see her—”

“I’m seeing her at four o’clock,” said Mr Wentworth. “If you think I need to know, write me a memo, Miss Hodge.”

“Eileen,” said Miss Hodge.

“Eileen who?” said Mr Wentworth, trying to pull his arm away. “You mean two girls wrote this note?”

“My name is Eileen,” said Miss Hodge, hanging on.

“Miss Hodge,” said Mr Wentworth, “3Z will be breaking windows by now!”

“But there’s Charles Morgan too!” Miss Hodge cried out, feeling his arm pulling out of her hands. “Mr Wentworth, I swear that boy recited a spell! Worms and custard and scummy potatoes, he said. All sorts of nasty things.”

Mr Wentworth succeeded in tearing his arm loose and set off downstairs again. His voice came back to Miss Hodge. “Slugs and snails and puppy-dogs’ tails. Write it all down, Miss Hodge.”

“Bother!” said Miss Hodge. “But I will write it down. He is going to notice!” She went at once to the staff room, where she spent the rest of the lesson composing an account of her experiment, in writing almost as round and angelic as Theresa’s.

Meanwhile, in the 2Y classroom, Mr Crossley shut the door behind Miss Hodge with a sigh. “Journals out,” he said. He had come to a decision about the note, and he did not intend to let his feelings about Miss Hodge interfere with his duty. So, before anyone could start writing in a journal and make it impossible for him to interrupt, he made 2Y a long and serious speech.

He told them how malicious and sneaky and unkind it was to write anonymous accusations. He asked them to consider how they would feel if someone had written a note about them. Then he told them that someone in 2Y had written just such a note.

“I’m not going to tell you what was in it,” he said. “I shall only say it accused someone of a very serious crime. I want you all to think about it while you write your journals, and after you’ve finished, I want the person who wrote the note to write me another note confessing who they are and why they wrote it. That’s all. I shan’t punish the person. I just want them to see what a serious thing they have done.”

Having said this, Mr Crossley sat back to do some marking, feeling he had settled the matter in a most understanding way. In front of him, 2Y picked up their pens. Thanks to Miss Hodge, everyone thought they knew exactly what Mr Crossley meant.

29 October, wrote Theresa. There is a witch in our class. Mr Crossley just said so. He wants the witch to confess. Mr Wentworth confiscated my knitting this morning and made jokes about it. I did not get it back till lunchtime. Estelle green has started knitting now. What a copycat that girl is. Nan Pilgrim couldn’t climb the ropes this morning and her name is Dulcinea. That made us laugh a lot.

29.10.81. Mr Crossley has just talked to us very seriously, Simon Silverson wrote, very seriously, about a guilty person in our class. I shall do my best to bring that person to justice. If we don’t catch them we might all be accused. This is off the record of course.

Nan Pilgrim is a witch, Dan Smith wrote. This is not a private thought because Mr Crossley just told us. I think she is a witch too. She is even called after that famous witch, but I can’t spell it. I hope they burn her where we can see.

Mr Crossley has been talking about serious accusations, Estelle wrote. And Miss Hodge has been making us all accuse one another. It was quite frightening. I hope none of it is true. Poor Teddy went awfully red when he saw Miss Hodge but she scorned him again.

While everyone else was writing the same sort of things, there were four people in the class who were writing something quite different.

Nirupam wrote, Today, no comment. I shall not even think about high table.

Brian Wentworth, oblivious to everything, scribbled down how he would get from Timbuktu to Uttar Pradesh by bus, allowing time for roadworks on Sundays.

Nan sat for a considerable while wondering what to write. She wanted desperately to get some of today off her chest, but she could not at first think how to do it without saying something personal. At last she wrote, in burning indignation,

I do not know if 2Y is average or not, but this is how they are. They are divided into girls and boys with an invisible line down the middle of the room and people only cross that line when teachers make them. Girls are divided into real girls (Theresa Mullett) and imitations (Estelle Green). And me. Boys are divided into real boys (Simon Silverson), brutes (Daniel Smith) and unreal boys (Nirupam Singh). And Charles Morgan. And Brian Wentworth. What makes you a real girl or boy is that no one laughs at you. If you are imitation or unreal, the rules give you a right to exist provided you do what the real ones or brutes say. What makes you into me or Charles Morgan is that the rules allow all the girls to be better than me and all the boys better than Charles Morgan. They are allowed to cross the invisible line to prove this. Everyone is allowed to cross the invisible line to be nasty to Brian Wentworth.

Nan paused here. Up to then she had been writing almost as if she was possessed, the way she had been at lunch. Now she had to think about Brian Wentworth. What was it about Brian that put him below even her?

Some of Brian’s trouble, she wrote, is that Mr Wentworth is his father, and he is small and perky and irritating with it. Another part is that Brian is really good at things and comes top in most things, and he ought to be the real boy, not Simon. But SS is so certain he is the real boy that he has managed to convince Brian too.

That, Nan thought, was still not quite it, but it was as near as she could get. The rest of her description of 2Y struck her as masterly. She was so pleased with it that she almost forgot she was miserable.

Charles wrote, I got up, I got up, I GOT UP.

That made it look as if he had sprung eagerly out of bed, which was certainly not the case, but he had so hated today that he had to work it off somehow.

My running shoes got buried in cornflakes. I felt very hot running round the field and on top of that I had lunch on high table. I do not like rice pudding. We have had Games with Miss Hodge and rice pudding and there are still about a hundred years of today still to go.

And that, he thought, about summed it up.

When the bell went, Mr Crossley hurried to pick up the books he had been marking in order to get to the staff room before Miss Hodge left it. And stared. There was another note under the pile of books. It was written in the same capitals and the same blue ballpoint as the first note. It said:

HA HA. THOUGHT I WAS GOING

TO TELL YOU. DIDN’T YOU?

Now what do I do? wondered Mr Crossley.

CHAPTER FOUR (#u69483a27-a89e-5ee5-a135-aa68f23603ac)

At the end of lessons, there was the usual stampede to be elsewhere. Theresa and her friends, Delia, Heather, Deborah, Julia and the rest, raced to the lower school girls’ playroom to bag the radiators there, so that they could sit on them and knit. Estelle and Karen hurried to bag the chillier radiators in the corridor, and sat on them to cast on their stitches.

Simon led his friends to the labs, where they added to Simon’s collection of honour marks by helping tidy up. Dan Smith left his friends to play football without him, because he had business in the shrubbery, watching the senior boys meeting their senior girlfriends there. Charles crawled reluctantly to the locker room to look for his running shoes again.

Nan went, equally reluctantly, up to Mr Wentworth’s study.

There was someone else in with Mr Wentworth when she got there. She could hear voices and see two misty shapes through the wobbly glass in the door. Nan did not mind. The longer the interview was put off the better. So she hung about in the passage for nearly twenty minutes, until a passing prefect asked her what she was doing there.

“Waiting to see Mr Wentworth,” Nan said. Then, of course, in order to prove it to the prefect, she was forced to knock at the door.

“Come!” bawled Mr Wentworth.

The prefect, placated, passed on down the passage. Nan put out her hand to open the door, but, before she could, it was pulled open by Mr Wentworth himself and Mr Crossley came out, rather red and laughing sheepishly.

“I still swear it wasn’t there when I put the books down,” he said.

“Ah, but you know you didn’t look, Harold,” Mr Wentworth said. “Our practical joker relied on your not looking. Forget it, Harold. So there you are, Nan. Did you lose your way here? Come on in. Mr Crossley’s just going.”

He went back to his desk and sat down. Mr Crossley hovered for a moment, still rather red, and then hurried away downstairs, leaving Nan to shut the door. As she did so, she noticed that Mr Wentworth was staring at three pieces of paper on his desk as if he thought they might bite him. She saw that one was in Miss Hodge’s writing and that the other two were scraps of paper with blue capital letters on them, but she was much too worried on her own account to bother about pieces of writing.

“Explain your behaviour on high table,” Mr Wentworth said to her.

Since there really was no explanation that Nan could see, she said, in a miserable whisper, “I can’t, sir,” and looked down at the parquet floor.

“Can’t?” said Mr Wentworth. “You put Lord Mulke off his lunch for no reason at all! Tell me another. Explain yourself.”

Miserably, Nan fitted one of her feet exactly into one of the parquet oblongs in the floor. “I don’t know, sir. I just said it.”

“You don’t know, you just said it,” said Mr Wentworth. “Do you mean by that you found yourself speaking without knowing you were?”

This was meant to be sarcasm, Nan knew. But it seemed to be true as well. Carefully, she fitted her other shoe into the parquet block which slanted towards her first foot, and stood unsteadily, toe to toe, while she wondered how to explain. “I didn’t know what I was going to say next, sir.”

“Why not?” demanded Mr Wentworth.

“I don’t know,” Nan said. “It was like – like being possessed.”

“Possessed!” shouted Mr Wentworth. It was the way he shouted just before he suddenly threw chalk at people. Nan went backwards to avoid the chalk which came next. But she forgot that her feet were pointing inwards and sat down heavily on the floor. From there, she could see Mr Wentworth’s surprised face, peering at her over the top of his desk. “What did that?” he said.

“Please don’t throw chalk at me!” Nan said.

At that moment, there was a knock at the door and Brian Wentworth put his head round it into the room. “Are you free yet, Dad?”

“No,” said Mr Wentworth.

Both of them looked at Nan sitting on the floor. “What’s she doing?” Brian asked.

“She says she’s possessed. Go away and come back in ten minutes,” Mr Wentworth said. “Get up, Nan.”

Brian obediently shut the door and went away. Nan struggled to her feet. It was almost as difficult as climbing a rope. She wondered a little how it felt to be Brian, with your father one of the teachers, but mostly she wondered what Mr Wentworth was going to do to her. He had his most harrowed, worried look, and he was staring again at the three papers on his desk.

“So you think you’re possessed?” he said.

“Oh no,” Nan said. “All I meant was that it was like it. I knew I was going to do something awful before I started, but I didn’t know what until I started describing the food. Then I tried to stop and I couldn’t, somehow.”

“Do you often get taken that way?” Mr Wentworth asked.

Nan was about to answer indignantly No, when she realised that she had gone for Brian with the witch’s broom in exactly the same way straight after lunch. And many and many a time, she had impulsively written things in her journal. She fitted her shoe into a parquet block again, and hastily took it away.

“Sometimes,” she said, in a low, guilty mutter. “I do sometimes – when I’m angry with people – I write what I think in my journal.”

“And do you write notes to teachers too?” asked Mr Wentworth.

“Of course not,” said Nan. “What would be the point?”

“But someone in 2Y has written Mr Crossley a note,” said Mr Wentworth. “It accused someone in the class of being a witch.”

The serious, worried way he said it made Nan understand at last. So that was why Mr Crossley had talked like that and then been to see Mr Wentworth. And they thought Nan had written the note. “The unfairness!” she burst out. “How can they think I wrote the note and call me a witch too! Just because my name’s Dulcinea!”

“You could be diverting suspicion from yourself,” Mr Wentworth pointed out. “If I asked you straight out—”

“I am not a witch!” said Nan. “And I didn’t write that note. I bet that was Theresa Mullett or Simon Silverson. They’re both born accusers! Or Daniel Smith,” she added.

“Now I wouldn’t have picked on Dan,” Mr Wentworth said. “I wasn’t aware he could write.”

The sarcastic way he said that showed Nan that she ought not to have mentioned Theresa or Simon. Like everyone else, Mr Wentworth thought of them as the real girl and the real boy. “Someone accused me,” she said bitterly.

“Well, I’ll take your word for it that you didn’t write the note,” Mr Wentworth said. “And next time you feel a possession coming on, take a deep breath and count up to ten, or you may be in serious trouble. You have a very unfortunate name, you see. You’ll have to be very careful in future. How did you come to be called Dulcinea? Were you called after the Archwitch?”

“Yes,” Nan admitted. “I’m descended from her.”

Mr Wentworth whistled. “And you’re a witch-orphan too, aren’t you? I shouldn’t let anyone else know that, if I were you. I happen to admire Dulcinea Wilkes for trying to stop witches being persecuted, but very few other people do. Keep your mouth shut, Nan – and don’t ever describe food in front of Lord Mulke again either. Off you go now.”

Nan fumbled her way out of the study and plunged down the stairs. Her eyes were so fuzzy with indignation that she could hardly see where she was going. “What does he take me for?” she muttered to herself as she went. “I’d rather admit to being descended from – from Attila the Hun or – or Guy Fawkes. Or anyone.”

It was around that time that Mr Towers, who had stood over Charles while Charles hunted unavailingly for his running shoes in the boys’ locker room, finally smothered a long yawn and left Charles to go on looking by himself.

“Bring them to me in the staff room when you’ve found them,” he said.

Charles sat down on a bench, alone among red lockers and green walls. He glowered at the slimy grey floor and the three odd football boots that always lay in one corner. He looked at nameless garments withering on pegs. He sniffed the smell of sweat and old socks.

“I hate everything,” he said. He had searched everywhere. Dan Smith had found a really cunning place for those shoes. The only way Charles was going to find them was by Dan telling him where they were.

Charles ground his teeth and stood up. “All right. Then I’ll ask him,” he said. Like everyone else, he knew Dan was in the shrubbery spying on seniors. Dan made no secret of it. He had got his uncle to send him a pair of binoculars so that he could get a really close view. And the shrubbery was only round the corner from the locker room. Charles thought he could risk going there, even if Mr Towers suddenly came back. The real risk was from the seniors in the shrubbery.

There was an invisible line round the shrubbery, just like the one Nan had described between the boys and the girls in 2Y. Anyone younger than a senior who got found in the shrubbery could be most thoroughly beaten up by the senior who found them. Still, Charles thought, as he set off, Dan was not a senior either. That should help.

The shrubbery was a messy tangle of huge evergreen bushes, with wet grass in between. Charles’s almost-dry shoes were soaked again before he found Dan. He found him quite quickly. Since it was a cold evening and the grass was so wet, there were only two pairs of seniors there, and they were all in the most trodden part, on either side of a mighty laurel bush. Ah! thought Charles. He crept to the laurel bush and pushed his face in among the wet and shiny leaves. Dan was there, among the dry branches inside.

“Dan!” hissed Charles.

Dan took his binoculars from his eyes with a jerk and whirled round. When he saw Charles’s face leaning in among the leaves at him, beaming its nastiest double-barrelled glare, he seemed almost relieved. “Pig off!” he whispered. “Magic out of here!”

“What have you done with my spikes?” said Charles.