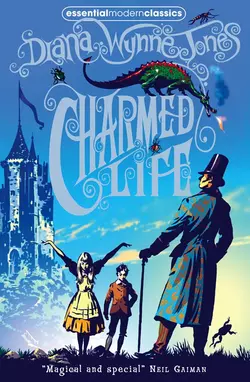

Charmed Life

Diana Jones

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Детская фантастика

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 382.20 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Glorious new rejacket of a Diana Wynne Jones classic award-winning favourite, featuring Chrestomanci – now a book with extra bits!Everybody says that Gwendolyn Chant is a gifted witch with astonishing powers, so it suits her enormously when she is taken to live in Chrestomanci Castle. Her brother Eric (better known as Cat) is not so keen, for he has no talent for magic at all.However, life with the great enchanter is not what either of them expects and sparks begin to fly!Winner of the Guardian Award.