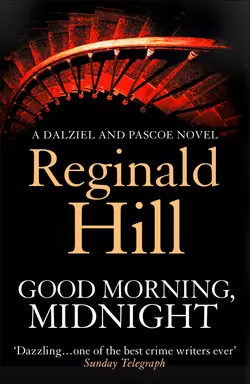

Good Morning, Midnight

Reginald Hill

The brilliant new crime thriller featuring Dalziel and Pascoe from the Top Ten Bestseller, Reginald HillThe locked-room suicide of Pal Maciver exactly mirrors that of his father ten years earlier. In both cases, Pal’s stepmother Kay Kafka is implicated. But Kay has a formidable champion in the form of Detective Superintendent Andy Dalziel…An obstructive superior is just the first of DCI Peter Pascoe’s problems. Disentangling the tortured relations of the Maciver family is any detective’s nightmare, and the fallout from Pal’s death reaches far beyond Yorkshire. For some, it seems, the heart is a locked room where it is always midnight…

REGINALD HILL

GOOD MORNING, MIDNIGHT

A Dalziel and Pascoe novel

Copyright (#ulink_677229d5-7176-543e-9042-118fbff5ce99)

Harper An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street, London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain in 2004 by HarperCollins

This edition published in 2010.

Copyright © Reginald Hill 2004

Reginald Hill asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780007123438

Ebook Edition © JULY 2015 ISBN: 9780007370306

Version 2015-06-22

Dedication (#u60590809-a96a-59b2-be4d-494b09bca0f8)

For Max and Mattie

and in memory of Pip

and all those other

companions of creation

right back to Pangur Ban

messe ocus Pangur Bancechtar nathar fira saindan:bith a menmasam fri seilgg,mu memna cein im saincheirdd.

Epigraph (#u60590809-a96a-59b2-be4d-494b09bca0f8)

Good Morning – Midnight –

I’m coming Home –

Day – got tired of Me –

How could I – of Him?

Sunshine was a sweet place –

I liked to stay –

But Morn – didn’t want me – now –

So – Goodnight – Day!

EMILY DICKINSON (1830 – 86)

Contents

Cover (#ucaf78308-e280-5204-a664-a85d66d75312)

Title Page (#uf269d49d-26fa-5fcb-952f-74971054025c)

Copyright (#u02e25296-fbbe-53ec-a802-1a772226824f)

Dedication (#u5844c3c9-2cfd-5b06-bd25-67e299520533)

Epigraph (#ubfa9b390-f791-591c-8ecb-d1477e19a774)

March 1991 (#u11a591da-6d9d-5ffe-a3c9-b5c852696c22)

1 By the Waters of Babylon (#ubfc57990-29db-5818-8cb7-fb7d1318666c)

March 20th, 2002 (#u2d6568c3-1266-519b-bc69-0637ecf74450)

1 Dropping the Loop (#u1b72dd89-65e1-5c63-b244-43e5d756559a)

2 Bedside Manner (#u55720552-ce07-58c4-963e-90c404f4d595)

3 Signora Borgia’s Guest List (#u3b6659e0-0e1f-560e-9179-4552f8ac1312)

4 An Open Door (#u498133c8-4d0d-5e00-b5dc-88f00ae0fbb4)

5 A Tight Cork (#uc6c01e02-c6b0-5923-b0df-e3902d96b47b)

6 A Fishy Smell (#ue3f28498-36fd-5f6a-bb37-0f0d9b7236cb)

7 A British Euro (#u31169cf1-43a9-51c0-b043-f2d20a712f69)

8 Another Fine Mess (#u8b71aa6c-3f66-5b7c-9126-74d204956f91)

9 The Battle of Moscow (#u2b0b574b-e4c1-536f-92aa-6b7820216d35)

10 A Shark in the Pool (#u0bba34a1-d10d-5157-b83a-18814735f103)

11 SD+SS=PS (#u376298ef-037a-539b-8dea-d5b7be1b4ef1)

12 Cold, Strange World (#u5e6d6a34-48d8-5b8c-af59-1c9563d84d0c)

March 21st, 2002 (#uec8c0b04-306d-5473-bae1-826928b0bd08)

1 The Crunch Witch (#u725a3509-ce67-5a6a-988a-037b6bf5c0c4)

2 The Kafkas at Home (#u8ebdb370-24e3-5501-a503-29797644cb0a)

3 A Nice Vase (#u7c099026-ae9b-5add-a71a-0a04a20d824f)

4 Like Father, Like Son (#ubdca10ac-0d0b-518c-9d9b-3bac4129541c)

5 Load of Bollocks (#u5c9b6abb-df52-511f-9676-7b0a15678b59)

6 Pal (#litres_trial_promo)

7 Amnesia (#litres_trial_promo)

8 Assignation (#litres_trial_promo)

9 Special Filling (#litres_trial_promo)

10 Green Peckers (#litres_trial_promo)

11 Cressida (#litres_trial_promo)

12 Lunch at the Mastaba (1) (#litres_trial_promo)

13 Hairy Chests (#litres_trial_promo)

14 See Me! (#litres_trial_promo)

15 Two-Mile Jigsaw (#litres_trial_promo)

March 22nd, 2002 (#litres_trial_promo)

1 870 (#litres_trial_promo)

2 Flying With the Cormorants (#litres_trial_promo)

3 Going With the Flow (#litres_trial_promo)

4 The Lily and the Rose (#litres_trial_promo)

5 Helen (#litres_trial_promo)

6 Big Maggie and Crazy Jane (#litres_trial_promo)

7 A Tool of the Devil (#litres_trial_promo)

8 A Bloody Great Splash (#litres_trial_promo)

9 Blue Beer (#litres_trial_promo)

10 Kay (1) (#litres_trial_promo)

11 A Feminist Hook (#litres_trial_promo)

12 Kay (2) (#litres_trial_promo)

13 Not the Beverley Sisters (#litres_trial_promo)

14 Mohawks (#litres_trial_promo)

15 Our Lady of Pain (#litres_trial_promo)

16 Jason (#litres_trial_promo)

17 Lunch at the Mastaba (2) (#litres_trial_promo)

18 In the Parlour (#litres_trial_promo)

19 Confessional (#litres_trial_promo)

20 Dalziel (#litres_trial_promo)

21 The Voice of Death (#litres_trial_promo)

22 Walking on Water (#litres_trial_promo)

March 23rd, 2002 (#litres_trial_promo)

1 A Lady Calls (#litres_trial_promo)

2 Dolly (#litres_trial_promo)

3 Middle Name (#litres_trial_promo)

4 A Bucket of Cold Water (#litres_trial_promo)

5 A Lovely Cup of Tea (#litres_trial_promo)

6 An Irish Joke (#litres_trial_promo)

7 A Load of Bullshit (#litres_trial_promo)

8 Birdland (#litres_trial_promo)

9 Mr Waverley (#litres_trial_promo)

10 And Having Done all, to Stand (#litres_trial_promo)

11 Midnight (#litres_trial_promo)

April 2003 (#litres_trial_promo)

1 By the Waters of Babylon (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Praise (#litres_trial_promo)

By Reginald Hill (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

March 1991 (#ulink_cb65c97c-02b8-5cd7-b8f9-d3318502ec31)

1 (#ulink_3564263c-4cfb-50a0-8612-ebb35f0418a1)

by the waters of Babylon (#ulink_3564263c-4cfb-50a0-8612-ebb35f0418a1)

The war had been over for three weeks. Eventually the process of reconstruction would begin, but for the time being the ruins of the plant remained as they had been twenty-four hours after the missiles struck. By then the survivors had been hospitalized and the accessible dead removed. The smell of death rising from the inaccessible soon became intolerable but it didn’t last long as the heat of the approaching summer accelerated decay and nature’s cleansers, the flies and small rodents, went about their work.

Dust settled, sun and wind airbrushed the exposed rawness of cracked concrete till it was hardly distinguishable from the baked earth surrounding it, and a traveller in this antique land might have been forgiven for thinking that these relicts were as ancient as those of the great city of Babylon only a few miles away.

Finally, with the smells reduced to a bearable level and the dogs picking over the ruins showing no signs of turning even mangier than usual, some bold spirits living in the vicinity began to make their own exploratory forays.

The new scavengers found a degree of devastation so extensive that even the most technically minded of them couldn’t work out the possible function of the plant’s wrecked machinery. They gathered up whatever might be sellable or tradable or adaptable to some domestic purpose and left.

But not all of them. Khalid Kassem, at thirteen counting himself a man and certainly imbued with a sense of adventure and ambition which was adult in its scope, hung back when his father and brothers departed. He was small for his age and slightly built, factors usually militating against his efforts to be taken seriously. In this case, however, he felt they could work to his advantage. He’d noticed a crack in a collapsed wall which he felt he might be able to squeeze through. Earlier while scavenging in the ruins of an office building he had come across a small torch, its bulb miraculously unbroken and its battery retaining enough juice to produce a faint beam. Instead of flaunting his find, he had concealed it, and when he spotted the crack and shone the light through it to reveal a chamber within, he began to feel divinely encouraged in his enterprise.

It was a tight squeeze even for one of his build, but eventually he got through and found himself in what looked to have been a basement storage area. There was blast damage here as there was everywhere and much of the ceiling had been shattered when the floors above had come crashing down, but no actual explosion seemed to have occurred in this space. Among the debris lay a scatter of metal crates, some intact, one or two broken open to reveal cuboids of some kind of lightweight foam cladding. Where this had split, Khalid’s faint beam of light glanced back off dully gleaming machines. He broke some of the cladding away to get a better look and discovered the machine was further wrapped in a close-clinging transparent plastic sheet. Recently on a visit to relatives in Baghdad, he had seen a refrigerator stacked with packets of food wrapped like this. It was explained to him that all the air had been sucked out so that as long as the package remained unopened the food inside would remain fresh. These machines too, he guessed, were being kept fresh. It did not surprise him. Metal he knew was capable of decay, and machinery was, in his limited experience, even harder to keep in good condition than livestock.

There was unfortunately no way to profit from his discovery. Even if it had been possible to recover one of these machines, what would he and his family do with it?

He turned to go, and the faint beam of his torch touched a crate rather smaller than the rest. A long metal cylinder had fallen across it, splitting it completely open, like a knife slicing a melon. It was the shape of its contents that caught his eye. Obscured by the cylinder resting on the broken crate, this lacked the angularity of the vacuum-packed machines. It was more like some kind of cocoon.

He put his torch down and, by using both hands and all his slight body weight, he managed to roll the cylinder to one side. It hit the floor with a crash that raised enough dust to set him coughing.

When he recovered, he picked up his torch and directed the ever fainter beam downward, praying it might reveal some treasure he could bear back proudly to his family.

The light glanced back from a pair of staring eyes.

He screamed in terror and dropped the torch, which went out.

That might have been the end for Khalid, but Allah is merciful and bountiful and permitted two of his miracles together.

The first was that as his scream died away (for want of breath not want of terror) he heard a voice calling his name.

‘Khalid, where the hell are you? Come on, or you’re in big trouble.’

It was his favourite brother, Ahmed.

The second miracle was that another light came on in the storeroom to replace his broken torch. This light was red and intermittent. In the brightness of its flashes he looked again at the vacuum-packed cocoon.

It was a woman in there. She was young and black and beautiful. And of course she was dead.

His brother shouted his name again, sounding both anxious and angry.

‘I’m all right,’ he called back impatiently, his fear fading with Ahmed’s proximity and of course the light.

Which came from … where?

He checked and his fear came back with advantages.

The light was coming from the end of the metal cylinder he had so casually sent crashing to the floor. There were Western letters on the metal which made no sense to him. But one thing he did recognize: the emblem of the great shaitan who was the nation’s bitterest foe.

Now he knew what had come crashing through the roof but had not exploded.

Yet.

He scrambled towards the fissure through which he’d entered. It seemed to have constricted even further, or fear was making him fat, and for a moment he thought he was caught fast. He had one arm through and was desperately trying to get a purchase on the ruined outer wall when his hand was grasped tight and next moment he was being dragged painfully through the gap into Ahmed’s arms.

His brother opened his mouth to remonstrate with him, saw the look on his face and needed no further persuasion to obey when Khalid screamed. ‘Run!’

They ran together, the two brothers, straining every sinew forward, like two champions contesting the final lap in an Olympic race, except that in this competition whenever one stumbled, the other reached out a steadying hand.

The tape they were running to was the Euphrates whose blessed waters had provided fertility and sustenance to their ancestors for centuries.

Time meant nothing, distance was everything.

The only sound was their laboured breathing and the swish of their limbs through the waist-high rushes.

Their eyes stared ahead, to safety, to their future, so they did not see behind them the ruins begin to rise into the air and be themselves ruined.

But they knew instantly there were now other faster competitors in the race.

The sound overtook them first, rolling by in dull thunder.

And then the blast was at their heels, at their shoulders, picking them up and hurling them forward as it raced triumphantly on.

Down they crashed, down they splashed. They were at the river. They felt its blessed coldness sweep over them. They let the current roll them at its own sweet will. Then they rose together, coughing and spluttering, and looked at each other, brother checking brother for damage at the same time as the impulses signalling the state of his own bone and muscle came pulsing along the nerves.

‘You OK, little one?’ said Ahmed after a while.

‘Fine. You?’

‘I’m OK. Hey, you run well for a tadpole.’

‘You too, for a frog.’

They pulled themselves on to the bank and sat looking back at the column of dust and fine debris hanging in the air.

‘So what did you find in there?’ asked Ahmed.

Khalid hardly paused for thought. He had no explanation for what he’d seen, but he was old enough to know he lived in a world where knowledge could be dangerous.

Later he would say a prayer for the dead woman in case she was of the faith.

Or even if she wasn’t.

And then a prayer for himself for lying to his brother.

‘Nothing,’ he said. ‘Just the rocket. Otherwise nothing at all.’

March 20th, 2002 (#ulink_e425dbf1-545d-5493-bd90-2b9d62489ed6)

1 (#ulink_9007c158-967a-5423-b9aa-a7084dd5e01b)

dropping the loop (#ulink_9007c158-967a-5423-b9aa-a7084dd5e01b)

It was the last day of winter and the last night of Pal Maciver’s life.

With only fifteen minutes to go, he was discovering that death was even stranger than he’d imagined.

Until the woman left, he’d been fine. From the first-floor landing he had watched her come through the open front door, trailing mist. She tried the light switch. Nothing happened. Standing in the dark she called his name. After all these years she still almost had the power to make him answer. Now was a critical moment. Not make-or-break critical. If she simply turned on her heel and walked away, it wasn’t disastrous. Getting her there could still be made enough.

But he felt God owed him more.

She turned back to the open door. Winter, determined to show he didn’t give a toss for calendars, had rallied his declining forces. There had been flurries of snow on the high moors but here in the city the best he could manage was a denial of light, at first with low cloud, then as the day wore on with mist rolling in from the surrounding countryside. But still enough light seeped in through the narrow window by the door for her to see the stub of candle and book of matches lying on the sill.

His fingers touched the microcassette in his pocket. Without taking it out he pressed the ‘play’ button. Two or three bars of piano music tinkled out, then he switched off.

Below in the hall it must have sounded so distant she was probably already doubting she’d heard it at all. Perhaps indeed he’d overdone the muffling and she really hadn’t heard it.

Then came the sputter of a match and a moment later he saw the amber glow of the candle.

God might not pay all his debts, but he kept up the interest.

Now the candle’s glow moved beyond his range of vision but his ears kept track of her.

Ever a practical woman, she went straight down the passage leading to the kitchen where the electricity mains box was situated high on the wall. He pictured her reaching up to it. He heard her exclamation as the door swung open, releasing a shower of dust and debris. She hated being mussed. He heard the mains switch click down, could imagine her growing frustration as nothing happened.

The glow returned to the entrance hall. Lots of choice here. The two big-bayed reception rooms, the dining room, the music room. But her choice had been preordained. She headed for the music room. The door was locked but the key was in the lock. She tried it. It wouldn’t turn. She tried to force it but she couldn’t make it move.

She called his name once more, nothing uneasy in her voice and certainly nothing of panic, but with the calm clarity of a summons to supper.

She waited for a reply that by now she must have guessed wasn’t coming.

He would have bet her next move would be to cut her losses and walk away. Even if she had the balls for it, he doubted she’d find any reason to come up the gloomy staircase with an uncertain light to confront the memories awaiting her there.

Wrong!

That was exactly what she was doing.

He almost admired her.

As she advanced, he retreated to the upper landing, matching his steps to hers. Would she want to visit the master bedroom? He guessed not and he was right. She went straight to the study door and tried to open it. Oh, this was good. When it didn’t budge, she stood still for a moment before stooping like a comic-book gumshoe to apply her eye to the keyhole. By the vinegary light of the candle, he saw her steady herself with her left hand against the central oak panel.

This was better still! God was truly in a giving vein today.

Suddenly she straightened up and he took a step back into the protection of the black shadows of the upper landing. Now she was nothing to him but the outermost edge of the candle’s faint aureole on the landing below. But the way she’d stood up had been enough. So had she always signalled by some undramatic but nonetheless emphatic movement – a twist of the hand, a turn of the head, a straightening of the shoulders – that a decision had been reached and would be acted on.

He saw the glow float down the stairs, wavering now as she moved with the swiftness of decision. He heard her firm step across the tiled entrance hall, then out on to the gravelled drive. She didn’t close the door behind her. She would leave it as she found it. That too was typical of her.

He waited for half a minute then descended to the hallway. She’d blown the candle out and left it where she’d found it. He pulled on a pair of white cotton gloves and relit the stump, slipping the book of matches into his pocket. He went to the music-room door, removed the key and carefully folded it in a fresh white handkerchief. From the top pocket of his jacket he took an almost identical key, unlocked the door and replaced the key in the same pocket before moving into the kitchen. Here he opened the electricity supply box and reset the mains switch to off. Then he levered off the cover of the fuse box. From his pocket he took the household fuses and replaced them and clicked the mains switch on.

Immediately below the electricity box was a narrow glass-fronted key cupboard, each hook neatly labelled. He opened it, removed the key from his top pocket and hung it on the empty hook marked Music Room.

Some of the dust and debris she’d disturbed from the supply box had landed on top of the key cupboard, some had drifted down to the tiled floor. He took a dustpan and brush from under the sink and carefully swept the tiles but the cupboard top he ignored. He tipped the sweepings into the sink and turned on the tap, letting it run while he opened a wall unit and took out two cut-glass tumblers. From his hip pocket he took a silver flask and a small prescription bottle. From the former he poured whisky into both tumblers into one of which he broke two capsules removed from the latter. He shook the mixture up before tossing it down his throat. He downed the other whisky too before lightly splashing water inside the tumblers, which he then shook and replaced upside down on the cupboard shelf.

Now he made his way back to the entrance hall and mounted the stairs. He inserted the key he had wrapped in his handkerchief into the study door. It turned with well-oiled ease. He wiped the handle clean with his glove and pushed open the door.

For a moment he stood there looking in, like an archaeologist who has broken into a tomb and hesitates to confront what he has been so energetic to discover.

And indeed there was something tomb-like about the room. The old oak panelling had darkened to a slatey blackness, heavily shuttered windows kept light and fresh air at bay and the atmosphere was dank and musty with the smell of old books emanating from two massive mahogany bookcases towering against the end walls. On the wall facing the door hung a half-length portrait of a man in rock-climbing gear with a triple-peaked mountain in the background. On one side of the portrait a coil of rope was mounted on the wall, on the other an ice axe. The painted face was severe and unsmiling as it glared down at the huge Victorian desk that loomed like an ancient sarcophagus in the centre of the floor.

Pal Maciver looked up at the man in the portrait and saw his own face there. He drew a deep breath and stepped over the threshold.

It was now that the strangeness started. Hitherto he had been the complete man of action, his whole being concentrated on the working out of his well-laid plans. But as he stepped through the doorway, awareness of that other darker threshold which was getting closer by the minute swept over him like the mist outside, leaving him helpless and floundering.

Then his strong will took command. There was still much work to do. He summoned Action Man back into control, and Action Man returned, but only at the price of a weird fragmentation of sensibility. Far from finding his mind wonderfully concentrated by the imminence of death, he discovered he was split in two, man of action and man of feeling, or rather in three, for here was the strangest thing of all, he found that, as well as the cast in this two-parter, he was audience too, an independent and almost disinterested observer, floating somewhere near the portrait, looking down with pity on that part of him drifting wraithlike in a shapeless swirl of fear and loss and bewilderment and despair while at the same time noting with admiration the way that Action Man was going about his preparations with the dextrous precision of a maid laying a supper table.

Action Man moved across the study floor, placed the candle on the desk, checked that the heavy curtains were tightly drawn across the shuttered windows and switched on the bright central light. Across the desk lay a six-foot length of thread. He picked it up, took out a cigarette lighter, gently pressed the thumb switch to release gas without giving a spark, and ran the thread through the jet. Then he fed the thread through the keyhole, put the key into the lock on the inside of the door, twisted the internal end of the thread round the head of the key so that about three feet hung down, went out on to the landing, once more clicked on his lighter and put the flame to the dangling end. The flame ran up the thread, vanished into the keyhole, emerged on the inside, and ran round the loops on the key. He let it get within a couple of feet of the end then snuffed it out.

With his gloved hand he cleaned off all traces of the burnt thread from the outside of the door, then he closed it and with great care turned the key in the lock.

Against the wall about two feet from the door stood a tall Victorian whatnot. On the shelf at the same level as the door lock rested a portable record player. Its retaining screws had been slackened so that he could lift out the turntable. He made a running loop at the unburnt end of the thread, dropped it over the drive spindle and pulled it tight. Then he fed the burnt end out through the power cable aperture, replaced the turntable and tightened the restraining screws. He picked up a record leaning against the table leg and placed it on the turntable. He plugged the power cable into a socket in the skirting board, set the control switch to ‘play’ and turned on the power. The arm swung out and descended, setting the stylus in the groove. For the second time that evening the opening bars of that gentlest of tunes, the opening piece ‘Of Foreign Lands and People’ from Schumann’s Childhood Scenes, sounded in the house.

He stood and watched as the rotations of the spindle wound the thread into the depths of the machine. Just before it vanished he pinched the end between his thumb and finger, held it, pausing the music momentarily, then let it go.

He switched off the light. Darkness surged back, almost tangible, as if it longed to snuff out the candle. But the tiny flame burnt on, filling the hollows of his face with shadow and turning the peaks to parchment as he went behind the desk and sat down in the ornately carved mahogany elbow chair.

He opened a drawer and from it he took a book, which he set on the desk, a legal envelope and a fountain pen. Out of the envelope he took several sheets of heavy bond paper. He held a single sheet over the candle till it began to burn. He let it fall into a metal wastepaper bin by the chair. He lit a second sheet, did the same, then the others one by one. Tongues of fire showed at the bin’s mouth, licking the darkness out of the study’s gloomy corners before they shrank and died. The record was still playing. He listened and recognized the fourth of the Childhood Scenes. With an effort he summoned up its title. ‘A Pleading Child’.

He shook the bin to make sure all the paper was consumed and stirred up the ashes with an ebony ruler, reducing them to a fine powder, some of which drifted up on the residual heat and hung in the air.

Now he rose again and went to the left-hand wall where alongside one of the bookcases a glass-fronted, metal-framed gun case was bolted on to the oak panelling. It was empty, covered with a soft pall of dust which he was careful not to disturb as he opened the door. He reached in, took hold of the gun-retaining clip, twisted it anticlockwise through ninety degrees, then pulled sharply. A section of panelling came away revealing a recess mirroring the cabinet in size and in function too. Here stood a shotgun, which unlike most other things in that room showed no sign of dusty neglect. It gleamed with a menacing beauty. Alongside it, on a leather-bound diary embossed with the year 1992, rested a pack of cartridges.

He took the gun and cartridges and returned to the desk. The music had reached piece number seven: ‘Dreaming’. He sat down with the weapon across his lap, broke it and loaded it. From his pocket he took a piece of string about a foot long with a loop at either end. He slipped one of the loops over the trigger, and leaned the weapon against the desk.

He checked his watch. Waited another thirty seconds. Picked up the fountain pen. Wrote in bold capitals on the envelope FOR SUE-LYNN. Set the pen down on the desktop. Checked his watch again. Stood up and went back to the gun case.

Up to this point he had done everything with steady purpose. Now he seemed touched by a sense of urgency.

He peeled off the gloves and tossed them into the secret recess, followed by his lighter, the matchbook, the microcassette, the hip flask and the prescription bottle. Next he replaced the panel, twisted the gun clip, shut the cabinet door, and went back to the chair into which he slumped with a finality which suggested he did not purpose rising again. He let the music back into his ears. Piece eleven was finishing. ‘Something Frightening’. Then piece twelve began. ‘Child Falling Asleep’.

He listened to it all the way through, asking himself, where had they gone, those thirty years?

As the music faded, he drew the book on the desktop towards him.

The final piece began. ‘The Poet Speaks’.

He opened the book. He did not need to look for his place. It fell open with an ease that suggested that this was a page frequently visited.

And now the observer saw that other part of himself, that disembodied swirl of feeling, start to drift back into the corporeal chamber from which it had been temporarily expelled. Like Action Man, it had its calmness too, but this was the calm of despair, the acknowledgement that the end was near, a process perfectly captured by the words the eyes stared at but did not need to see.

He scanned it – staggered –

Dropped the Loop

To Past or Period –

Caught helpless at a sense as if

His Mind were going blind –

Feeling Man, the observer saw, was absolute for death, so completely separated from hope and time and sense and feeling and all the threads of experience which tie us lightly to life that he was far ahead of the meticulous preparation of Action Man for that journey from the familiarity of now into the mystery of next …

The music was coming to an end. The observer could hear it but Feeling Man had ears for nothing but the words of the poem as if they were being read aloud by the soft American voice of their creator …

Groped up, to see if God was there –

Groped backward at Himself

… while Action Man still went quietly about his business, removing his left shoe and sock, bringing the gun between his legs with the stock firmly on the floor, slipping the loop of string over his big toe, grasping the barrel with both hands and holding it steady against the edge of the desk, then leaning forward and pressing the soft underpart of his chin hard against the muzzle.

Now the quiet voice in Feeling Man’s mind speaks the final words

Caressed a Trigger absently

and wandered out of Life

while Action Man lowers his left foot, and Observing Man, rather to his surprise, has time to see the ball of shot burn its way up through jaw and palate, squirting blood from mouth and nostrils and punching out the eyes before emerging through the top of his skull in a fountain of bone and brain which spatters floor and desk and open book.

For a millisec reason and sensation and observation are reunited in one consciousness.

Then the empty body slumps to one side, the record dies away, the fine ash from the wastepaper bin slowly settles, the candle gutters.

Pal Maciver exists no longer.

Except in the hearts and minds and lives of those he leaves behind.

2 (#ulink_5ef2051e-8810-5584-be88-5858c45fbdac)

bedside manner (#ulink_5ef2051e-8810-5584-be88-5858c45fbdac)

Sue-Lynn Maciver stretched her naked body languorously against her lover’s hand and laughed.

‘What?’ said Tom Lockridge.

‘I was thinking, first time I felt you inside me, it cost me a hundred quid.’

‘Wait till you get my bill for this.’

He spoke lightly but she knew he didn’t like being reminded he was still her doctor. When Pal had dropped him, his first reaction had been that her husband suspected something. Once reassured, his second reaction had been that this was a good opportunity for her to come off his list too.

‘Don’t be silly,’ she’d said. ‘Why give up the perfect cover for me visiting your surgery, you coming to the house?’

‘It’s just that, if it ever came out, the GMC don’t take kindly to doctors screwing their patients.’

‘Really? How else do they expect you to become stinking rich?’

When he didn’t laugh, she said, ‘Relax, Tom. It’s not going to come out, not from me, anyway. I’ve got even more reason to keep it from Pal than you have from your precious Council. Or your precious wife for that matter.’

She’d meant it. But nonetheless it wasn’t altogether displeasing to feel she had a hold over her lover that went beyond his desire.

He removed his hand from between her legs and pushed back the duvet.

She glanced at her watch and said, ‘What’s the hurry? We’ve got another hour at least.’

‘Just going to the loo,’ he said, rolling out of bed.

‘Why do men always have to pee after sex?’ she called after him.

He paused in the doorway and said, ‘I’ll draw you a diagram when I get back.’

She made a face at the prospect. Sometimes it wasn’t altogether comfortable screwing a man who knew so much about the internal workings of the human body. She reached out to the cigarette packet lying by the phone on the bedside table and lit one. He’d probably give her the antismoking lecture, but it was better than a conducted tour of his innards.

The phone rang.

She picked it up and said, ‘Hi.’

‘Sue-Lynn, it’s Jason.’

She stiffened then forced herself to relax.

‘Jase, shouldn’t you be chasing a little ball around a squash court with my husband?’

‘That’s why I’m ringing. He hasn’t turned up. My mobile’s on the blink and I thought he might have left a message with you.’

She stubbed her cigarette out, swung her legs off the bed, found her panties on the floor and started tugging them on one-handed as she replied, ‘Sorry, Jase. Not a word. But I shouldn’t worry. Probably a customer showed up as he was on his way out. You know Pal. He’d miss his own funeral if he thought there was a deal to be done. How’s Helen? Must be close now. Give her my best. Look, got to go. ’Bye.’

She put down the phone and was crouching on the floor searching for her bra when she heard the toilet flush. A moment later, Lockridge came through the door. He was smiling and there was evidence he was having serious thoughts about how to spend the next hour. The smile faded as he saw her rise on the far side of the bed with her bra in her hand.

‘Pal’s loose,’ she said before he could speak. ‘Get dressed.’

‘Shit. You don’t think he’s on to us? Jesus wept!’

He’d started dragging on his trousers with more haste than care and done something she didn’t care to think about with the zip.

‘Shouldn’t think so, but better safe than sorry … oh hell. Did you hear that?’

‘What?’

‘I don’t know. A noise. Downstairs. No … on the stairs.’

They both froze, mouths agape, eyes staring, she with her bra round her neck, he with his hand on his fly zipper, like a tableau vivant of Guilt Surprised, and were both in a state to take the flash of light that came through the open door as the harbinger of one of heaven’s avenging angels.

3 (#ulink_1d30ae96-1177-57b6-bfbf-466387971ba3)

Signora Borgia’s guest list (#ulink_1d30ae96-1177-57b6-bfbf-466387971ba3)

The mist was definitely getting thicker. Much more and they’d be calling it fog, which was bad news. There were enough idiots out there who couldn’t drive properly in broad daylight without making things even more problematic for them.

Ignoring the obvious impatience of the cars behind her, Kay Kafka drove her Mercedes E-Class down the quiet suburban roads at five mph under the permitted speed limit and signalled a good hundred yards before she turned into the driveway of Linden Bank.

With the mist and encroaching darkness toning down the unfortunate shade of lavender the Dunns had chosen for their outside woodwork, she was able to re-experience her feelings on first seeing the house. Helen had rung full of excitement to tell her that she and Jason had found a place they both liked but she wanted Kay’s approval before committing. Kay had gone along prepared to lie, and had instead been delighted. She’d liked the clean modern lines, the harmonious proportions, the use of rosy brick under a shallow-pitched roof of olive tiles. The prepared lies had come in useful later, however, once the newlyweds had moved in.

At the door Kay only had to ring once before it was flung open by a young woman hugely pregnant.

‘You’re late,’ she said accusingly.

‘You too by the look of you.’

The young woman grimaced and said, ‘Still a couple of days to go – Kay, it’s lovely to see you.’

The two women embraced, not without difficulty.

‘Jesus, Helen, you sure it’s only twins you’ve got in there?’

‘I know – it’s terrible – I may have to let out my smocks.’

They went into the house. Outside the evening temperature was dropping fast. In here as usual the central heating was set a couple of degrees above Kay’s comfort level. In anticipation she was wearing only a sleeveless silk blouse beneath her chic sheepskin jacket.

As Helen hung it up she brushed her hand over the fleecy collar and said, ‘Hey, have you been on a building site? This is a bit dusty.’

‘Is it? You know these old houses. I wish Tony had bought somewhere modern like this,’ said Kay removing the silk square with which she’d protected her short black hair from the mist and shaking it gently. ‘He sends his love.’

‘Give him mine. I really love that blouse,’ said Helen enviously. ‘Wish I dared let people see the tops of my arms.’

In fact pregnancy became her. Big she was, but with the roseate carnality of a Renoir bather. In the glow of that aura many other women would have been reduced to attendant shadows, but Kay Kafka, pale faced and pencil slim, was not diminished.

They went into the lounge. The first time Kay had come into this room and found it full of light from the huge picture window overlooking the long rear lawn, she had known exactly how she would furnish and decorate it. Now, even after many visits, she had to make an effort not to react to the heavy furnishings, the fitted pink carpet, the gilt-framed Canaletto reproductions and the Regency striped curtains which, closed, at least concealed the Yorkstone patio running down to a solar-powered fountain in red-veined marble with which the Dunns had replaced half of the lawn. The only thing that won her approval was the Steinway upright occupying one corner, which, if Jason had had his way, would probably have been replaced by an electronic keyboard in dazzling silver. Strange, she thought, how people could be so beautiful without having any inner sense of beauty.

Tony, when she had told him about this, had asked, ‘So if she bought the right kind of house, how come she put the wrong sort of stuff in it with you looking over her shoulder?’

‘Because I wasn’t looking over her shoulder, not even when she asked me to,’ said Kay. ‘It’s not my place.’

‘Come on. The kid worships you and you’re the nearest thing to a mother she ever had.’

‘But I’m not her mother and I never want to give her occasion to remind me. In fact, looking back, I suspect she chose the house because she knew in advance I’d like the look of it, which I did. Inside’s different. They’re the ones who’ve got to live in it.’

‘You’re all heart, baby,’ said Tony, smiling. He was a man of many contradictions and this capacity to be cynical and affectionate at the same time was one of them.

Now she seated herself gingerly at one end of a long sofa. This was great furniture for lounging in. Helen in her pre-pregnancy days would usually curl up in one of the huge chairs with her legs tucked up beneath her and Kay had had to admit that the setting suited her marvellously well. Herself, even in Helen’s company, she liked to stay in control, and felt taken over by the soft cushions and yielding upholstery. Tony had called it a great shagging sofa, and thereafter whenever she sat on it she got a mental flash of Jason and Helen intimately intertwined in its depths.

Now Helen was long past the curling up stage and presumably the intimate intertwining stage too. She’d brought one of the broad high elbow chairs from the dining room to sit upon, though even this was becoming a tight fit.

‘Hope you don’t mind – got pizzas coming – cooking’s getting hard without doing myself or the Aga serious damage – sorry.’

There’d been a time when Kay had tried to amend Helen’s rather breathlessly unpunctuated way of speaking but she’d given up when she saw she was merely creating tension. The same with the girl’s taste in interior decoration. This was how she was, and you didn’t look a gift horse in the mouth especially when God was the giver.

‘Pizza’s fine,’ she said with a smile. ‘Though I hope Jase is making sure you get a slightly more varied diet.’

‘Don’t worry – I’m sticking to the menu I got from the clinic – more or less – tonight’s a treat – triple anchovies – damn! Just when I’d got comfortable.’

The phone in the entrance hall was ringing.

‘I’ll get it,’ said Kay.

She rose elegantly, not an easy feat from the absorbent upholstery, and went into the hall.

‘Hello,’ she said.

‘Kay, is that you? It’s Jason. Look, Pal hasn’t turned up for squash and I wondered if maybe he’d tried to ring me at home. Could you ask Helen?’

‘Sure.’

She called, ‘It’s Jase. Pal’s stood him up. He wants to know if he’s left a message here.’

‘No, nothing – tell Jase to get himself something at the Club like he usually does – don’t want him spoiling our evening just because Pal’s spoilt his.’

‘Jase, did you get that?’

‘Yes. Who needs phones when you’ve got a wife who could yodel for Switzerland? OK, tell her I’ll get myself a pasty, then go up on the balcony and see if I can find a couple of sweaty girls to watch. How are you keeping, Kay?’

‘Mustn’t complain.’

‘Why not? Everyone else does. Probably catch you before you leave. Bye.’

Kay put down the receiver and stood looking at her reflection in the gilt mirror on the wall behind the phone table. Her face wore the contemplative almost frowning expression which Tony had once caught in a snap which he labelled La Signora Borgia checks her guest list. She relaxed her features into their normal edge-of-a-smile configuration and went back into the lounge.

4 (#ulink_18da5305-e00b-51d0-906e-fea4ae2e2d03)

an open door (#ulink_18da5305-e00b-51d0-906e-fea4ae2e2d03)

‘There we go,’ said PC Jack ‘Joker’ Jennison, placing the two newspaper-wrapped bundles on the dashboard. ‘One haddock, one cod.’

‘Which is which?’

‘Mail’s haddock, Guardian’s cod.’

‘That figures. What do I owe you?’

‘Don’t be daft. Chinese chippie two doors up from the National Party offices, they’d pay good money to have us park outside till closing time.’

‘Then they’ll be getting a refund,’ said PC Alan Maycock. ‘We’re out of here.’

He gunned the engine and set the car accelerating forward.

‘What’s your hurry?’ asked Jennison.

‘Just got a tip from CAD that Bonkers is on the prowl. Don’t think he’d be too chuffed to find us troughing outside a chippie, so let’s find somewhere nice and quiet.’

Bonkers was Sergeant Bonnick, a new broom at Mid-Yorkshire HQ who was hell bent on clearing out its dustiest corners. Also he was big on physical fitness and had already been mildly sarcastic about the embonpoint of the two constables, saying that watching them getting into their car was like seeing a pair of 42s trying to squeeze into a 36 cup.

‘Not too far, eh? I hate cold chips,’ said Jennison, pressing the warm packets to his cheeks.

‘Don’t fret. Nearly there.’

They’d turned off the main road with its parade of shops and were speeding into the area of the city known as Greenhill.

Once a hamlet without the city wall, Greenhill had been absorbed into the urban mass during the great industrial expansion of the nineteenth century. The old squires who bred their beasts, raised their crops, and hunted their prey across this land were replaced by the new squires of coal and steel and commerce who wanted houses to live in that had land enough to give the impression of countryside but without any of the attendant inconveniences of remoteness, agricultural smells or peasant society. So the hamlet of Greenhill became the suburb of Greenhill, in which farms and cotts and muddy lanes were replaced by urban mansions and tarmacked roads.

From the naughty nineties to the fighting forties, many of the great and the good of Mid-Yorkshire paraded their pomp in Greenhill. But after the war, the rot set in. Old ways and old fortunes faded, and though for a while the makers of new fortunes still turned their thoughts to what had once been the arriviste’s dream, a Greenhill mansion, there rapidly developed an awareness of their inconvenience and a sense that they were at best démodé, at worst crassly kitsch, and by the seventies Greenhill was in steep decline. Many of the mansions were converted into flats, or small commercial hotels, or corporate offices, or simply knocked down to make room for speculative development.

Some areas hung on longer than others, or at least by sheer weight of presence managed to preserve the illusion that little had changed from the glory days. Chief among these was The Avenue, which, if it ever had a praenomen, had long ago shed it as superfluous to general recognition. Here on nights like the present one, with mist seeping in from the already shrouded countryside to blur the big houses behind their screening arbours into vague shapes, still and awe-inspiring as sleeping pachyderms, it was possible to drive slowly down the broad street between the ranks of leafy plane trees and imagine that the great days of Empire were with us yet.

In fact, driving slowly down the Avenue was still a popular pursuit among a certain section of Mid-Yorkshire society, but they weren’t thinking of Empire, except perhaps metaphorically. The shade against the elements provided by the trees, the privacy afforded by many of the dark and winding driveways, plus the thinness on the ground of complaining residents, made this a favourite parade ground for prostitutes and kerb crawlers. In the misty aureoles of the elegantly curved Greenhill lampposts, the Avenue might look deserted. But set your car crawling sedately along the kerbside and, like dryads materializing from their trees at the summons of the great god Pan, the ladies of the night would appear.

Except if the car had POLICE written all over it, when the effect was quite other.

Jennison hadn’t been able to last out and was already unfolding his parcel, releasing the pungent smell of hot battered fish and vinegary chips.

‘Can’t you bloody wait till I get parked?’

‘No, me belly thinks me throat’s cut. This’ll do. Pull over here.’

‘Don’t be daft. We’d have the girls throwing bricks at us for frightening off the punters. I know just the spot. Bonkers’ll never find us here.’

He swung the wheel over and ran the car under the plane trees into a gravelled driveway between two stone pillars. Stumps of concrete at their tops suggested that they had once been crowned with some ornamental or heraldic device but this had long since vanished, probably at the same time as the ornate metal gate. Its massy hinges were still visible on the right-hand pillar, however, while on the left, graven deep enough in the stonework to be still readable though heavily lichened, was the name MASCOW HOUSE.

Leaning over the high ivied garden wall was an estate agent’s board reading FOR SALE WITH VACANT POSSESSION.

Maycock drove up the length of the drive till he could see the house. Its complete darkness and shuttered windows confirmed the promise of the sign that there was no one here to disturb or be disturbed by.

‘That’s funny,’ he said as he brought the car to a halt.

‘What?’

‘Isn’t that door open?’

‘Which door?’

‘The house door, what do you fucking think?’

The two men strained their eyes through the swirling mist.

‘It is, tha knows,’ said Maycock. ‘It’s definitely open.’

Jennison leaned across, dropped the warm newspaper packet on to his colleague’s lap and switched off the headlights.

‘Can’t see it myself,’ he said. ‘Now shut up and eat your haddock afore it gets cold.’

They munched in silence for a while. Then the radio crackled out their call sign and a voice they recognized as Bonnick’s said, ‘Report your position.’

‘Shit,’ said Maycock.

‘No sweat,’ said Jennison.

He switched on his transmitter and said, ‘We’re in the Avenue, Sarge. Checking out an unsecured property.’

‘The Avenue? Which Avenue?’ demanded Bonnick, sounding irritated. ‘Use proper procedure, full details when reporting location.’

Jennison grinned at his partner and replied mildly, ‘Just the Avenue, Sarge. In Greenhill. Thought everyone knew that. The property’s called Moscow House. It’s on the left-hand side as you’re heading east, about one hundred and five metres from the junction with Balmoral Terrace. There’s a name on the gate pillar. Moscow House. That’s M, O, S, C, O, W. Moscow. H, O, U, S, E. House. Bit misty out here but if you get lost, there’s one or two helpful young ladies around who’ll be glad to show you the way. Over.’

There was silence, though in his mind Maycock could hear police constables pissing themselves laughing all over Mid-Yorkshire.

‘Report back to me as soon as your check’s finished. Out,’ said the sergeant in a quiet controlled voice.

‘Think you’ve made a friend there,’ said Maycock.

‘He can please his bloody self.’

‘Aye, but we’d best do what you’ve told him we’re doing,’ said Maycock, getting out of the car. ‘Come on. Let’s take a look.’

‘I’ve not finished me cod yet!’ protested Jennison.

But to tell the truth his appetite was fading. For Joker Jennison had a secret. He was scared of the dark, and particularly scared of old dark houses. His fear was metaphysical rather than physical. Muscular muggers and crazy crack-heads he took in his stride. But in his infancy he couldn’t sleep without a night-light and as a teenager he’d fainted while watching The Rocky Horror Picture Show. On reviving and realizing the damage this was likely to do to his street cred, he had faked every symptom of every illness he could think of, causing a meningitis scare in his school and getting him confined to an isolation ward in the infirmary while they did tests. It had worked as far as his mates were concerned, but on joining the police force (which itself had been an act of denial), he had soon realized that if he fainted every time he had to enter a deserted property with only his torch for light, pretence of illness would get him thrown out as quickly as admission of terror. So he had learned to grit his teeth and keep his true feelings hidden behind the screen of pleasantries that got him his nickname.

Now he remained stubbornly in his seat as his partner mounted the steps to the open door. Moscow House seemed to grow in bulk as he watched, towering high into the swirling mist where it wasn’t hard for his straining eyes to detect ruined battlements around which flitted squeaking bats.

Then the mist came rolling down the dark façade as if bent on putting a curtain between himself and Alan Maycock.

‘Oh shit,’ said Jennison again. What was worse, out here alone or in there with his partner?

That part of his mind still in touch with reason told him that if anything happened to Maycock he’d have to go into the house anyway.

With a sigh of desperation, he rolled his bulk out of the car, crushed the remnants of his fish supper into a ball and hurled it into the darkness, then jogged towards the house shouting, ‘Hang about, you daft bugger. I’m coming!’

5 (#ulink_07d56a49-b7a2-5871-9556-5b3886c47907)

a tight cork (#ulink_07d56a49-b7a2-5871-9556-5b3886c47907)

‘What do they put these things in with? Sledgehammers?’ snarled Cressida Maciver, gripping the bottle between her knees and hauling at the corkscrew with both hands.

Ellie Pascoe smiled uneasily and glanced at her watch. Half eight, two empty bottles lying on the floor, and they hadn’t even eaten yet. Nor could her sensitive nose detect any evidence of food in preparation wafting from the kitchen, and Cress was one of those cooks who couldn’t scramble an egg without sprinkling it with spices.

But it wasn’t the thought of going hungry that caused her unease. It was the fact that on a couple of previous occasions, even with food, the opening of a third bottle had been closely followed by an attempt at seduction which came close to sexual assault. After the second time, Ellie had been ready with various stratagems to pre-empt the well-signalled pounce, and though their farewell hug sometimes came close to frottage, she had managed to escape without damage. Sober, next time they met, Cress seemed to have forgotten everything in the same way that, drunk, she clearly had no recollection of Ellie’s having confided in her that once, at university, curiosity and a determination not to appear repressed or naive had got her into a female lecturer’s bed, but the experience had done nothing for her and wasn’t one she had any desire to repeat.

Usually she got a taxi home, but when her husband, Detective Chief Inspector Peter Pascoe had announced they’d need a baby-sitter as piles of neglected paperwork were going to keep him at his desk deep into the evening, she’d declared that what they lost on the sitter they could gain on the taxi and arranged for him to pick her up about ten thirty, which was the usual danger time. Now the schedule was blown to hell, and as well as uneasy, Ellie felt cheated. She was very fond of Cress, and in matters of taste generally, politics sufficiently, and humour absolutely, they shared so much that their evenings together before the hormones took over were a delight which tonight looked like being cut well short.

The assaults always occurred when Cressida was between men, which was pretty frequently. The intensity of her commitment was more than most could abide for long. The journey from feeling adored and cosseted to feeling cribbed, cabined and confined was a short one, in some cases taking only a matter of days. In the aftermath of break-up, Cressida always turned to her female friends for comfort. Men were only good for one thing, and that was overrated. Passion was for pubescents. Female friendship was the thing. Which sensible life-view ruled her mind until the opening of the third bottle, when a meeting of mature female minds was suddenly discarded in favour of a close encounter of mature female flesh.

The last break-up seemed to have been even more than usually traumatic.

‘I really liked the guy,’ she bewailed. ‘He had everything. And I mean everything. Including a Maserati. Have you ever had sex in a Maserati, Ellie?’

Ellie pursed her lips as if running though a check list of top cars, then admitted she’d missed out.

‘Never mind,’ said her friend consolingly. ‘The driving position’s fabulous but the shagging position’s absolute agony. But you wouldn’t believe a guy driving a car like that would turn out to have five kids and a religion that won’t let his wife entertain the idea of divorce.’

Her eyes glinted malevolently.

‘Maybe if I had a word with his wife that would change her religion,’ she added.

‘Cress, you wouldn’t.’

‘Of course I wouldn’t. Not unless provoked. And why the hell am I wasting quality time with my dearest friend talking about that sunburnt shit of a witch doctor?’

She gave a mighty heave at the corkscrew and succeeded in hauling it out of the bottle, but only at the expense of leaving half the cork in the neck.

Oh well, that should delay matters a little, thought Ellie, offering up a prayer of thanks to whatever it was that almost certainly wasn’t there.

As if to reproach her for this qualification in her devotion, the phone rang.

‘Shit,’ said Cressida. ‘See what you can do with this sodding thing, will you?’

As soon as she left the room, Ellie pulled out her mobile and pressed her husband’s speed-dial key. He answered almost immediately.

‘Peter,’ she whispered. ‘It’s me.’

‘What? It’s a lousy line.’

‘Just listen. I need you earlier.’

‘Ah,’ he said. ‘Second bottle time already, eh?’

He was quick. That was one of the good things about him. One of many good things.

‘Third,’ she said. ‘No sign of food and she’s been dumped again. Some medic. She’s started on about the problems of sex in a Maserati.’

‘Poor thing. Can’t you tell her you’ve got a headache? Always works with me.’

‘Ha ha. Can you get here soon? Say it’s some problem with the sitter.’

‘I’m on my way. Fifteen minutes tops. Hang in there, girl.’

She’d just got the phone into her bag when Cressida came back into the room.

‘Sue-Lynn,’ she said. ‘My sister-in-law. Wants to know if I’ve heard from Pal. Seems he didn’t turn up for his squash with Jase and nobody knows where he is. Silly bitch.’

In the five years of their friendship, she’d never talked in any detail about her family, not even her brother Pal with whom she was close and who’d been indirectly responsible for bringing Ellie and Cress together. He ran an antique shop called Archimagus in the town’s medieval area near the cathedral. Ellie had been in a couple of times without buying anything and without registering more about the proprietor than that he was a good-looking young man who after a token offer of help became a non-hassling background presence. On the third occasion when she expressed interest in a seventeenth-century knife box in walnut with a beautiful mother-of-pearl butterfly inlay on the lid, he’d answered her questions with an eloquent expertise that very subtly implied that only a person of the most sensitive taste would have selected this item above all the rest of his stock. Finally he suggested she took it home to see how it looked in situ, no obligation, which had made a young woman who’d just come into the shop roar with laughter.

‘I bet he hasn’t mentioned the price yet,’ she said.

On reflection, Ellie had to admit this was true.

A price was mentioned. Ellie looked at the newcomer and raised an eyebrow enquiringly.

She pursed her lips, shook her head and said, ‘That the best you can do for a friend of your sister?’

‘You two are friends?’ said Pal.

Cressida had looked at Ellie, grinned and said, ‘No, but I think we could be.’

To which Pal had replied, ‘So let me know how it works out, then we can discuss a possible price cut.’

It had worked out well and the knife box now adorned the Pascoe dining room. But though her friendship with Cressida burgeoned, the brother never became anything more than an antiques dealer with whom she was on first-name terms. As for the rest of the family, Ellie had picked up that there was a younger sister, and also that they’d lost their parents some time in childhood, but she’d made no attempt to pry into the exact nature of the evident tensions and problems Cress’s upbringing had left her with. This didn’t mean she wasn’t curious – hell, they were friends, weren’t they? And knowing your friends was even more important than knowing your enemies – but in Ellie’s book though mere curiosity might get you nebbing into the life of a stranger, it was never enough to justify sticking your nose into the affairs of a friend.

But if the confidences came unasked, she was not about to discourage them, particularly in a situation where they also served the useful function of postponing the threatened pounce.

‘You’re not worried?’ she said.

‘No. He’s probably still at work, giving discount.’

‘Sorry?’

Cressida grinned.

‘Well-heeled ladies love their objets d’art but love their money even more. Pal says I’d be amazed how many of them after a bout of haggling will say, “Do you give a discount for cash, Mr Maciver? Or something …?”’

‘I presume you didn’t say this to your sister-in-law?’

‘Thought about it, but in the end I just said if she was really worried she should ring the police and the hospitals.’

‘Decided to go for reassurance then.’

‘You needn’t concern yourself about Sue-Lynn. Self-centred cow. Any worries she’s got will be about herself, not Pal.’

‘But his squash partner is worried too … Jase, you said?’

‘Jason Dunn. My brother-in-law,’ said Cressida, sounding rather surprised, as if she’d just worked out the relationship.

‘So, married to your sister?’

‘Yeah, Helen the child bride.’

‘Lot younger than you then?’ said Ellie.

‘She’s younger than everyone,’ said Cress dismissively. ‘Like Snow White. Doesn’t get any older no matter how often you see the picture. Only this one still adores the wicked stepmother.’

‘Stepmother?’ This was completely new. ‘I didn’t know you had a stepmother.’

‘Not something I boast about. You don’t want to hear all this crap. Haven’t you got that bottle open yet?’

‘Sorry. It’s this broken cork. This stepmother, is she really wicked?’

‘Goes with the job, doesn’t it? She’s a pain in the arse anyway. You’ve probably seen her name in the papers. You wouldn’t forget it. Kay Kafka, would you believe? Why do Yanks always have these crazy fucking names? Here, let me try.’

She grabbed the bottle from Ellie and began poking at the broken cork.

Ellie, feeling that a gibe about names didn’t come well from someone called Cressida who had a brother called Palinurus, was by now sufficiently interested in the family background to have pursued it even without its pounce-postponing potential.

‘So you don’t care for your stepmother? And Pal?’

‘Hates her guts.’

‘But Helen took to her?’

‘She was only a kid when Dad remarried. It was easy for Kay to sink her talons in. Me and Pal were older, our shells had toughened up.’

‘And when your father died … when was that?’

‘Ten years ago. Pal was of age so out of it. I was seventeen so officially still in need of a responsible adult to care over me. I was determined it wasn’t going to be Kay even if it meant signing up with dotty old Vinnie till I made eighteen.’

‘Vinnie?’

‘My aunt Lavinia. Dad’s only sister. Mad as a hatter; you need feathers and a beak before she’ll even speak to you. But being a blood relative did the trick and I was able to give Kay the finger.’

‘But Helen thought different?’

‘Don’t think thought entered into it. She was only nine. Pal and I tried to get her out of the clutches, but she went all hysterical at the idea of being separated from Kay. Poor little cow. Not much upstairs, and I’m sure Kay preferred it that way. She’s a real control freak. Probably handpicked Helen’s husband with that in mind too.’

‘Sorry?’

‘Jason. He’s a PE teacher at Weavers, so not what you’d call an intellectual giant. But a real hunk. And hung. Known as a bit of a stud before Helen hooked him. They say he fucks like a Rossini overture.’

This was an interesting concept but not one that Ellie, in her present antaphrodisiac mode, felt it wise to pursue.

‘So Helen’s stayed close to her stepmother? Which means you and Pal aren’t all that close to Helen?’

Cressida shrugged.

‘She made her choice.’

‘But Pal plays squash with Jason?’

‘Yes, he does,’ said Cressida. ‘Can’t think why, especially as I’m sure Jase must whup the shit out of him and Pal’s not a good loser. Still there’s nowt so queer as folks, is there? And most of us are even queerer than we think.’

She gave Ellie what could only be described as a suggestive leer, then said, ‘Fuck this,’ and drove the broken segment of cork down into the bottle, squirting wine over her hand and forearm.

She raised her fingers to her mouth and licked the red drops off, her eyes fixed on Ellie and a tiny smile twitching her lips.

‘More ways of popping a reluctant cork than one, eh?’ she said. ‘Pass your glass.’

6 (#ulink_6477851c-d5f3-5302-a4fe-95586b3ea094)

a fishy smell (#ulink_6477851c-d5f3-5302-a4fe-95586b3ea094)

Moscow House was full of light, which the shuttered and curtained windows kept penned within. Only through the open front door did any escape to offer a weak challenge to the besieging fog.

Finding the electricity switched on had been a big bonus, particularly for Jennison, but he still stuck close to his partner as they went methodically through the downstairs rooms, then headed upstairs.

‘Hello hello hello,’ said Maycock as he pushed open a bedroom door to reveal a double bed, neatly made up, though not with fresh linen. ‘This looks like it’s still in use.’

‘Yeah. Hey, do you think some of the girls might have been using this place to bring their punters?’

‘Could be.’ Maycock sniffed the air. ‘Smell a bit sexy to you?’

Jennison sniffed.

‘Nah,’ he said. ‘Think it’s thy haddock.’

There was only one door they couldn’t open.

Some of Jennison’s uneasiness returned. In haunted houses there was always one door that was locked, and when you opened it …

Maycock was kneeling down.

‘Key’s in the lock on the inside,’ he said.

Jennison said hopefully, ‘Maybe one of the girls heard us come in and she’s locked herself in here.’

‘Could be.’

Maycock banged his fist against the solid oak panel and called, ‘It’s the police. If there’s anyone in there, come on out.’

Jennison stepped back in alarm, recalling tales of vampires and such creatures who could only join humankind if invited.

Nothing happened.

Maycock stooped to the keyhole again. Once more he sniffed.

‘More sex?’ said Jennison.

‘Bit of a burnt smell.’

‘You think there’s a fire in there?’

‘No. Not strong enough. Listen.’

He pressed his ear to the door.

‘Can you hear something?’

‘What?’

‘Sort of whirring, scratching noise.’

‘Scratching?’ said Jennison unhappily, his imagination reviewing a range of possibilities, none of them comforting.

‘Yeah. Here, give it a try with your shoulder.’

Obediently, Jennison leaned against the door and heaved.

‘Jesus, you couldn’t open a paper bag like that.’

‘You try then. Didn’t I hear you once had a trial for Bradford? Or were that a trial at Bradford for masquerading as a rugby player?’

Provoked, Maycock hit the door with all his strength and bounced back nursing his shoulder.

‘No go,’ he said. ‘Bolted as well as locked, I’d say.’

‘Better call this in,’ said Jennison.

He spoke into his personal radio, gave details of the situation, was told to wait.

They went to the head of the stairs and sat down.

‘Not one of my best ideas, this,’ admitted Maycock. ‘We’d have been better off eating our nosh outside the chippie, and bugger Bonkers.’

Jennison surreptitiously crossed himself and wished he had some garlic. He knew that at times of psychic stress it was a dangerous thing to name evil spirits as that could easily summon them up. So it came as a shock but no surprise when out of the air came a familiar voice, saying, ‘So there you are, making yourselves comfortable. OK, what’s going off here? And why does your car smell like a chip-shop?’

They peered into the hallway and found themselves gazing down at the slim athletic figure of Sergeant Bonnick who’d just come through the open door.

They scrambled to their feet but were saved from having to answer by the radio.

‘Keyholder to Moscow House is a Mr Maciver, first name Palinurus. Just say if you need that spelt, Joker. We’ve rung the number given and got hold of Mrs Maciver. She got a bit agitated when we told her we wanted to talk to her husband about Moscow House. She says she doesn’t know where he is, in fact nobody seems to know where he is, and he’s missed some kind of appointment this evening. I’ve passed this on to Mr Ireland. Hold on. He’s here.’

Ireland was the duty inspector.

‘Alan, you’re sure there’s a key on the inside of that locked door?’

‘Certain, sir.’

‘Then I think from the sound of it you ought to take a look inside. You need assistance to break in?’

Bonnick spoke into his radio.

‘Sergeant Bonnick here, sir. No need. I’ve got a ram in my boot. I’ll get back to you soon as we’re in.’

He tossed his keys to Jennison, who set off down the stairs.

‘Be prepared, eh, Sarge?’ said Maycock. ‘Good idea carrying everything you might need around with you.’

‘Not always, else you’d be towing a mobile chippie,’ said Bonnick. ‘Show me this locked room.’

He examined the door carefully and stooped to check through the keyhole.

‘Key’s still there,’ he said.

‘Well, it would be,’ said Maycock. ‘Seeing as I just saw it.’

‘Not necessarily. Not if there’s someone in there to take it out,’ said Bonnick.

‘We did shout.’

‘Oh well then, they were bound to answer,’ said the sergeant. ‘God, when did you last take some serious exercise?’

Jennison had returned, carrying the ram. He was slightly out of breath. Outside, with the mist turning even the short journey from front door to car into a ghostly gauntlet run, he hadn’t been tempted to hang about.

‘All right, which of you two still has something resembling muscle under the flab?’

‘Al had a trial for the Bulls,’ said Jennison.

‘That right, Alan? Let’s see you in action then.’

The constable hit the woodwork four or five times with the ram with no visible effect except on himself.

‘They knew how to make doors in them days,’ he gasped.

‘They knew how to make policemen too,’ growled Bonnick. ‘Give it here.’

He swung it twice. There was a loud splintering. He gave Maycock a told-you-so look.

‘Yeah, but I weakened it,’ protested the constable.

‘Let’s see what’s inside, shall we?’ said Bonnick.

He raised his right foot and drove it against the door. It flew open. Light from the landing spilled into the room.

‘Oh Jesus,’ said Bonnick.

But Jennison, whose fear of the supernatural was compensated for by a very relaxed attitude to real-life horror, exclaimed, ‘Ee bah gum, he’s made a reet mess of himself, hasn’t he, Sarge!’

7 (#ulink_3bd6c73c-cbc8-5797-8171-42cb7d2cb61b)

a British Euro (#ulink_3bd6c73c-cbc8-5797-8171-42cb7d2cb61b)

The company of her stepdaughter was always a delight to Kay Kafka. They shared an affection which went all the deeper because it involved neither the constraints of blood nor the coincidence of taste and opinion. Indeed, during these regular Wednesday evening encounters, they rarely strayed nearer the harsh realities of existence than a discussion of films and fashions and local gossip, but what might (in Kay’s case at least) have been tedious in the company of another was here rendered delightful by the certainty of love.

In recent months, however, the approach of harsh reality in the form of the soon-to-be-born children had provided another topic, which could have kept them going for the whole visit if they’d let it. Even here, there wasn’t much harshness in evidence. It had been so far a comparatively easy pregnancy, and, bulk apart, Helen seemed to be enjoying her role as serenely glowing mother-in-waiting. So they would move easily over the wide range of pleasurable preparations for the great day – baby clothes, pushchairs, nursery decoration and, of course, names. Here Helen was adamant. Superstitiously she’d refused all offers to identify the gender of the twins, but if one were a girl, she was going to be called Kay.

‘And I don’t care what you say,’ she went on, ‘they’re both going to call you grandma.’

Which had brought Kay as close to tears as she’d been for a long while. She’d told the children to call her Kay when she married their father. The two elder ones did their best to avoid calling her anything polite, but Helen was young enough to want, eventually, to call her mum. Realizing the problem this would give the girl with her brother and sister, Kay had resisted.

‘I want to be her friend,’ she explained to her husband. ‘The lady’s not for mummification.’

But she never explained to him just how very hard it was for her to resist.

Grandma was different. She had no resistance to offer here. And even if she had, she doubted if it would have made a difference. Helen had powers of obduracy which could sometimes surprise. In this at least she resembled her dead father.

So she’d smiled and embraced the girl and said, ‘If that’s what you want, that’s what I’ll be. Thank you.’

It had been a good moment. One of many on these Wednesday evenings. But tonight seemed unlikely to contribute more. Somehow Jason’s phone call had disturbed the even flow, then the fog delayed the pizza delivery and when they finally turned up, they were what Kay called upper-class anglicized – pale, lukewarm and flaccid with not much on top. But the real downer was the fact that, as she entered the finishing straight of her pregnancy, it seemed finally to be dawning on Helen that the birth of the twins wasn’t just going to be a triumphal one-off champagne-popping occasion for celebration, it was going to change the whole of her life, for ever.

Kay tried to be light and reassuring but the young woman was not to be jollied.

‘Now I know why you would never let me call you mum,’ she said. ‘Because it would have made you my prisoner.’

‘Jesus, Helen,’ exclaimed Kay. ‘What a weird thing to say.’

‘I come from a weird family,’ said Helen. ‘You must have noticed. Talking of which, I wonder if Pal turned up.’

On cue the answer came with the sound of the front door opening. A moment later Jason looked into the room. In his mid twenties, six foot plus, blond, beautifully muscled and with looks to swoon for, he could have modelled for Praxiteles. Or Leni Riefenstahl. If his genes and Helen’s melded right, these twins should be a new wonder of the world, thought Kay, smiling a welcome.

‘Hi, Kay,’ he said. ‘It’s all right, sweetie, I’m not going to disturb you. Any word from Pal?’

‘No, nothing. He didn’t show at the club then?’

‘No. What the hell’s he playing at? I hope nothing’s wrong.’

The phone rang.

He said, ‘I’ll get it,’ and retreated to the hall, closing the door firmly behind him.

‘Why’s he so worried?’ said Helen irritably. ‘It’s not as if Pal was ever the most reliable of people.’

‘Oh, I always found him pretty reliable,’ said Kay sardonically.

She regretted it as soon as she said it. Family relationships were a no-go area, again one of her own choosing. Many times in the past it would have been easy to swing along with Helen as she took off in a cadenza of indignation at the attitude and behaviour of her siblings, but, as she’d explained to Tony, ‘In the end, they’re blood family, I’m not, and nothing’s going to change that.’ To which he’d replied in his mafiosa voice, ‘Yeah, family matters. You may have to kill ’em, but you should always send a big wreath to the funeral. It’s the American way. That’s one of the things I miss, being so far from home.’

She sometimes thought Tony made a joke of things to hide the fact he really believed them.

Helen gave her a sharp look and said, ‘OK, I know he’s been an absolute bastard with you – me too – but things change and lately you’ve got to admit he’s been trying. These games of squash with Jase, a year ago that wouldn’t have been possible, but it’s a kind of rapprochement, isn’t it? You know Pal, he would never just come straight out and say, “Let’s forget everything and start over,” he’d have to come at you sideways.’

Sideways. From above, beneath, behind. Oh yes, she knew Pal.

She smiled and said, ‘Yes, the games obviously mean a lot to Jason. And no one likes being stood up.’

Through the closed door they heard the young man’s voice rise. They couldn’t make out the words but his intonation had alarm in it.

He came back into the room.

‘I’ve got to go out again,’ he said.

He was making an effort to sound casual but his fresh open face gave the game away.

‘Why? What’s happened?’ demanded Helen.

‘Nothing,’ he said. Then, seeing this wasn’t a sufficient answer, he went on, ‘It was Sue-Lynn wanting to know if I’d heard anything yet. The police just rang her. They wanted to contact Pal as the keyholder of Moscow House. They wouldn’t give any details, but it’s probably just a break-in, or vandalism. You know what kids are like. I blame the teachers.’

His attempt at lightness fell flat as an English comic telling a kilt joke at the Glasgow Empire.

‘So where are you going?’ asked Helen.

‘Sue-Lynn said she’s going down to Moscow House. I thought maybe I should go too. She sounded upset.’

‘Since when did you give a damn how Sue-Lynn sounded?’ demanded his wife.

Kay said, ‘No, you’re quite right, Jase. It’s probably nothing, but just in case … Hang on, I’ll come with you.’

She stood up. Helen rose too, rather more slowly.

‘All right, we’ll all go,’ she said.

‘Helen, love, don’t be silly,’ protested Jason. ‘In your condition …’

‘I’m pregnant,’ she snapped, ‘not a bloody invalid. And Pal’s my brother.’

There we go, thought Kay. Blood.

She said brightly, ‘This can hardly have anything to do with Pal if the police are trying to get hold of him as the keyholder, can it?’

It rang as true as a British Euro.

‘All right. Come on,’ said Jason, who knew when argument was useless.

They got their coats and went out. It took some time to ease Helen into the car, even though it was a big Volvo estate. Jason’s beloved MR2 had gone in the fourth month of pregnancy when he’d had to admit its impracticality as a vehicle for his expanding wife and his imminently expanding family.

Finally they were on their way.