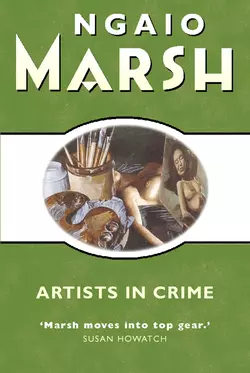

Artists in Crime

Ngaio Marsh

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 150.68 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: One of Ngaio Marsh’s most famous murder mysteries, which introduces Inspector Alleyn to his future wife, the irrepressible Agatha Troy.It started as a student exercise, the knife under the drape, the model’s pose chalked in place. But before Agatha Troy, artist and instructor, returns to the class, the pose has been re-enacted in earnest: the model is dead, fixed for ever in one of the most dramatic poses Troy has ever seen.It’s a difficult case for Chief Detective Inspector Alleyn. How can he believe that the woman he loves is a murderess? And yet no one can be above suspicion…