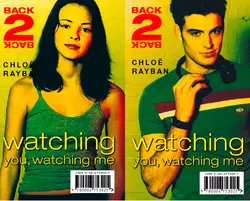

Watching You, Watching Me

Chloe Rayban

There are two sides to every story and this new series, BACK-2-BACK, is designed to attract both boys and girls. Teenagers will love to read what she really thinks about him and what he really thinks about her!Natasha’s story – she’s 15 and still at school and lives across the street from super cool Matt who’s just moved in. He’s into blading and he’s going out with a stylish girl from his college and plays loud music the whole time. And does he even notice she exists?Matt’s story – he’s 17 and is not as cool as he’d like to be, and college is pretty rough. Music is his real passion and getting some DJ work at the club is great. He really likes the look of the cute babe in the house opposite, but he always seems to be in trouble with her parents, and she turns away whenever they meet…

BACK2BACK

watching

you, watching me

Tasha’s side of the story …

CHLOË RAYBAN

with grateful thanks toJames Ross, Felix Milton, Molly Milton and Leo Bearfor their help with the music and club scene

CONTENTS

Cover (#ue07a3080-ed67-5e91-b883-dc672b822bdd)

Book One Title Page (#u78cb6353-5f2f-5509-85e0-3f33ae2b024e)

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Also by Chloë Rayban

Copyright

About the Publisher

Chapter One (#ufbc92d8e-ce70-57ff-8971-011421628926)

There it was again. That creepy feeling in the small of my back. I swung round and looked back down the road. I could feel someone watching me. But where from? The street was deserted, not even a car coming down it. I scanned windows for twitching nets, and my gaze settled on number twenty-five.

Number twenty-five had been boarded up for ages, years. Ever since Mr Copps, the old man who’d lived there, had died. There’d been some sort of legal battle about who was meant to inherit it, and until this was settled it couldn’t be sold.

Jamie and Gemma called it ‘the spook house’, and I must admit that on occasions, when they were being a real pain while I was baby-sitting, I’d made up ghost stories about it to keep them quiet. Jamie had woken up screaming with a nightmare one night, so Mum had put an end to that. She was livid.

Number twenty-five looked pretty spooky, as a matter of fact, on an overcast afternoon like today. It was a tall terraced house like the others in the street, but the windows, with their rough covering of weathered boarding, gave it a blind, desolate look. Paint was peeling off the window frames and weeds had grown up through the front path. There was a row of house-martins’ nests under the eaves — slowly nature was taking over.

I shook myself and continued down the road. I decided to put the whole thing down to an over-active imagination. My own fault really for making up all those stories.

It was later that evening, when he was meant to be getting ready for bed and was hiding from Mum behind the curtains in my room, that Jamie suddenly let out a whimper.

‘Tasha!’ He ran and clung to me.

‘Hey … what is it?’

They’re there … they’re really there …’

‘Who are where?’

‘At number twenty-five — the spooks’

‘Don’t be silly. ‘Course they’re not. No such thing as spooks. You know that, don’t you?’

‘But there are. They’re there …’ He dragged at my sleeve. ‘Come ‘n look … There’s lights moving around in the house.’

‘Rubbish,’ I said. But I could feel the little hairs on the back of my neck rising in spite of myself. ‘You’re making it up.’

‘No honest … There are … Look.’

I let him lead me to the window, and we crouched in the dark part between the curtains and the windowpane, staring out.

‘Where?’ I demanded. This was typical of Jamie, always blowing up the most trivial thing into a drama.

‘Wait …’ he whispered. His hand was holding my arm so hard it hurt.

I scanned the bleak façade of number twenty-five. And then I froze. He was right. Just the faintest glimmer of a light, but it was moving through the rooms. You caught a glimpse of it every time it passed a crack in the boarding. It would pause and glimmer and then it would flicker on. It was moving up now as if something was floating upwards through the house …

‘What are you two up to?’ Mum pulled the curtains back and found us sitting there.

‘We’ve found a spook,’ said Jamie, now emboldened by the presence of Mum and the cheery light of the room.

‘Tasha …’ said Mum with a warning look.

‘No … its not me this time, honestly. But there is someone or something in number twenty-five … See for yourself.’

The three of us huddled behind the curtain. It took some minutes before Mums eyes became accustomed to the gloom, and then she pronounced:

‘Squatters.’

‘What’s squatters?’ asked Jamie, his lower lip wobbling. To his six-year-old brain ‘Squatters’ were quite possibly as bad as spooks, or maybe they were worse — a special kind of spook, one that moved around by a kind of legless elevation like those weirdo yogic flyers.

‘That’s the limit,’ she said. ‘I knew something like this would happen if that house was left empty like that.’ She set off down the stairs to find Dad.

‘Tasha — what are squatters?’ demanded Jamie again in a wavering voice.

I put an arm round him. ‘Squatters are people who haven’t got homes of their own. So they find empty houses and they break in and squat in them.’

‘Why can’t they stand up straight?’

‘They can, silly … ‘Squat’ is just a word that means … umm … to take over an empty house and live there, without paying rent or anything.’

‘Why isn’t there a proper word?’

‘I don’t know!’ I hadn’t time to get into ‘why-mode’ for a discussion with Jamie — I wanted to know what Dad was going to make of the situation.

Dad came striding through my door at that moment. He stuck his head through the curtains and stared out.

‘Can’t see a thing — you’re all making this up.’

‘Wait until your eyes get adjusted,’ said Mum.

‘Hrrmph,’ said Dad.

‘It’s not spooks, it’s ‘squatters’,’ said Jamie importantly. They’re people who haven’t got houses so they go and live in other people’s houses while they’re out …’

‘I know what ‘squatters’ are, thank you Jamie … shhh!’ He waved a hand behind him for silence. I joined him, and we stood together for a moment straining our eyes towards the shadowy house.

‘See … There it is in the top room,’ I said.

‘Yeaahhh,’ said Dad. ‘Flickering … must be a candle …’

‘Right. I’m going to phone the police,’ said Mum.

‘No hang on …’ said Dad. He extricated himself from the curtains. ‘Let’s think about this for a moment.’

‘What’s there to think about?’

‘Well … How long has that house stood empty?’

‘Two years … could be three.’

‘So that’s two or three years when the house could have provided a roof over someone’s head. Some poor individual who’s been sleeping rough in a doorway or something.’

I loved the way Dad was like this — always surprising me — always ready to see the other side of the question. I slipped an arm through his.

‘Dad’s right. Mum. There could be some poor homeless person in there, trying to shelter.’

‘Poor homeless person! Next thing we know there’ll rubbish all the way up the street, rats, needles — God knows what else …’

‘It’s a situation this country’s brought upon itself,’ said Dad.

‘This is a respectable street. Families, children … the last thing we need is squatters.’

At that point Jamie upset my entire carefully-stacked collection of CDs. This mini-landslide brought Mum’s attention back to him and she remembered the initial reason for coming into my room.

‘Bed for you Jamie. Goodness, look at the time!’

She went off with him, still grumbling over her shoulder at my father.

‘You and your oh-so-liberal views.’

‘You may or may not have forgotten … I lived in a squat myself once,’ Dad called after her.

‘You? You were a squatter?’ I exclaimed.

‘Not for long. When I was a student. We were so hard up we had no choice. But we got the place running like clockwork. I reckon we did the people who owned it a favour. Damp old house it was before we cleaned it up. Mended the roof too — all the ceilings would have been down in another few months.’

‘So what do you think we should do?’

‘I reckon I ought to pay our new neighbours a visit. See if they’ve got forked tongues and fangs …’

‘What if they have?’

‘You willing to stand watch?’

‘Sure …’

‘Bring the portable in here and if you see someone coming at me with a meat cleaver — ring 999 straight away. Oh … and … Don’t tell Mum, OK?’

I stood at the window grasping the portable really tightly. I had a sick feeling in my throat. What if there were violent people in there — criminals — thugs?

I watched Dad cross the road and make his way up the overgrown front path. He hammered on the front door. The sound echoed down the road. I wondered if Mum would hear, but by the sound of bathwater running, I could tell she was busy bathing Jamie.

Nothing happened for a while. Then Dad hammered again, harder this time. Number twenty-five seemed absolutely silent — uninhabited. And then, I tightened my hold on the portable. The light on the first floor was on the move again, floating and glimmering through chinks in the boarding. It was descending through the house.

I waited tensely, expecting the front door to be split asunder any minute and some equivalent of the Incredible Hulk to come bursting through. But it didn’t. Dad just stood there. He seemed to be talking animatedly through the door, waving his arms around. I could tell by his back that he was speaking but I couldn’t catch what he said because Mum was letting the bathwater out. Then Dad seemed to give up — he shook his head and came back across the road.

I heard our front door slam.

I headed down the stairs.

‘What happened? What did they say?’

Dad cleared his throat. ‘Bloody confident little bastard, whoever he is. Said he had every right to be there. Told me I was an interfering old busy-body. And suggested that I … Piss off.’

I could tell by Dad’s tone that he felt put-down. Guess it was a male pride thing — he’d gone over that road in the spirit of a well-wisher, a comrade-in-arms, and he’d been told to get lost. I managed to stifle the impulse to giggle. He went to the fridge and took out a can of lager, snapped it open and sat down, thoughtfully sipping it.

‘What did he sound like — this bloke? A great big bruiser?’

‘No … not at all. Quite young …’

‘How young?’

‘Hard to tell but couldn’t be more than, say seventeen … eighteen?’

‘Who?’ Gemma had left off watching the TV and was helping herself to juice from the fridge.

‘Someone who seems to have moved in over the road, number twenty-five.’

‘What, in the spook house?’

‘It’s not a spook house, remember. No such things as spooks. Gemma,’ said Dad, taking the juice container out of her hand and returning it to the fridge before she drank the lot.

‘Seventeen or eighteen. What does he look like?’ asked Gemma. Already I could see she was assessing his romantic potential. Gemma was positively addicted to romances. Love Stories, Sweet ValleyHigh, Mills & Boon — Gemma consumed all this stuff at the rate of three books a week.

‘I haven’t actually seen him yet. We talked through the door.’

‘Oh … but you must be able to tell. You can from voices, you know. I read this book about these two people who fell in love over the telephone. They’d never even met and it was the real thing …’

‘Gemma listen,’ I said. This is like some tramp or something. Wild-eyed, unshaven, overweight maybe. He probably smells … Really rough.’

‘He didn’t sound rough. Just annoyed,’ said Dad. ‘Funny business.’

We could hear Mum coming downstairs. Dad obviously wanted to bring the discussion to a close.

‘Hey Gem. Your bedtime. Off you go.’

‘Must I?’

Mum appeared at the kitchen door. ‘Yes, you must. Term starts tomorrow, remember?’

Later that night, when I went up to bed, I opened my window as usual. Dad has this real thing about fresh air. Unless its about ten degrees below, he absolutely insists we sleep with the windows open. He says we can pile on as many duvets as we like but young lungs need fresh air and the air is freshest at night when there’s not so much traffic around. He’s got this big thing about traffic too, but I won’t bore you with all that right now. I stared out of the window. The light was still there, flickering in the top room now. With the curtains drawn around behind me, I settled down to watch. Nothing much was happening — only the light was moving around a bit. And it was pretty chilly too.

‘What’s going on?’ Gemma’s small warm body thrust itself against mine.

‘Ssssh!’ I said unnecessarily, as he could hardly have heard us from across the street. ‘Nothing.’

‘I reckon he looks like Liam Gallagher. Unshaven, you know, and kind of hungry-looking. Dead sexy.’

‘What would you know about it?’ Gemma was only nine.

‘What would you?’ she retorted. You’ve never even had a boyfriend.’

She was right really. At fourteen I didn’t score too highly on the ‘boyfriend’ front. Unless you counted being kissed at Christmas by Stephen, my cousin, but he was a total dweeb and since it was under the mistletoe, I guess it didn’t count anyway. Girls at school had been going out with guys since they were twelve practically. I was teased about my single status the whole time. But short of bumping into the boy of my dreams in the local shopping mall, I didn’t have that much opportunity for male conquest. Mum and Dad were dead strict about pubs and clubs, and even parties were vetted. It really wasn’t fair.

‘Look, it’s gone out,’ said Gemma. The light had suddenly been extinguished. We sat in silence for a few minutes more. Watching a flickering candle was pretty boring, but watching a totally dark house was ridiculous. So we went to bed after that.

I lay in bed unable to sleep for hours. My mind kept on making up different photo-fits of our mysterious new neighbour.

I had just got to Mystery-Man Photo-Fit Number Eight which was a bronzed kind of Baywatch guy who’d escaped from Hollywood and come to Britain because he was being hounded by Interpol for a murder he hadn’t committed and was trying to clear his name. I featured prominently in this one, working as an undercover agent and doing amazingly heroic acts for which he was stunned and grateful and he was just about to …

When I must have fallen asleep.

Chapter Two (#ufbc92d8e-ce70-57ff-8971-011421628926)

Mornings in our house are always pretty unbelievable. But the first morning of any term gets the chaos award.

I left as much time as I reasonably could before I made my appearance downstairs. Mum had called six times. I climbed into my loathsome uniform. Grey skirt made as short as I dare by rolling round the waistband (a quick unroll adds that vital inch on uniform inspection days). Hideous white shirt you can see your bra through, yukk! I’d forgotten the gross feel of the nylony fabric — the kind of stuff that gives off electric shocks like forked lightning when you undress in the dark. Dangerous if you ask me. Tie — now I reckon it’s kinky making girls wear ties. And to complete the ensemble, scratchy nylon and acrylic mix grey cardie — ghastly!

I stomped downstairs. Gemma was sitting on the third step practising her recorder. The ‘tune’ she was attempting to master was ‘London’s Burning’. Every time she got to the two final notes — ‘Fire, Fire’ — she played two painfully wrong ones.

‘Shut up Gems — you’re giving everyone a headache!’

‘Miss Dawson said we had to have it perfect over the holidays.’

‘But you’ve had all summer!’

I climbed over her. Mum was dressed in her smart ‘I’ve got a meeting at work’ outfit and making sandwiches distractedly.

‘Oh, there you are. You couldn’t be an angel and find Jamie’s football gear for me, could you? It’s brand new, should be in the drawer but …’

‘He’s been wearing it as pyjamas,’ chimed in Gemma, appearing in the kitchen doorway.

‘I have not …’ said Jamie going red — and an argument broke out.

Mum tore open a tin of tuna and Yin and Yang started up a chorus at her feet.

‘Jamie, its your job to feed the cats this week. Why aren’t they fed?’

‘Mum!!!!! …’ Gemma was staring at the sandwiches practically in tears. You know I can’t stand mayonnaise. It makes me want to throw up. The very sight of it and I puke …’

‘Oh goodness yes … I forgot. OK … Tasha, you feed the cats and Jamie, you get your football gear.’

‘Dad came in. I couldn’t find them. Definitely not in the bedroom.’

‘What?’

‘The car keys.’

‘I don’t believe this! We’re going to be late,’ Mum fussed.

Gemma broke off in the middle of an ear-piercing wrong note. ‘Mu-um, we can’t be late on the first day. I’ll get a seat near the front …’

‘I’ll look for the keys,’ I offered — anything to avoid smelly cat food duty.

‘Hey Gems … its OK, your sandwich hasn’t got mayonnaise on now,’ said Jamie.

Mum leapt at Yang, who in the absence of breakfast, had seized his opportunity and was licking mayonnaise off Gemma’s bread.

‘If you smack him I shall ring the NSPCC,’ said Gemma.

‘Try the RSPCA, Gemma,’ suggested Dad. ‘Unless you continue playing that thing — then we might need both.’ And with that he scooped up his briefcase and escaped through the front door.

Mum headed upstairs.

Gemma poured milk on her cereal.

‘I wonder if he’s got any breakfast over there …’ she sighed to me.

‘Who?’ asked Jamie as he spooned cat food ever so slowly and carefully on to two saucers. Yin and Yang were practically going berserk at his feet.

I shoved the saucers under their noses.

‘Maybe we should make up a food parcel, like in a basket or something, and then he could let down a rope and haul it up to his room,’ continued Gemma in a dreamy tone.

‘Dad’s trying to get rid of him, not encourage him,’ I pointed out.

‘But what if he stays up there and starves to death? It’ll be our fault.’

‘He could have my tuna sandwiches and then I’d have to have school dinners,’ suggested Jamie generously. Mum didn’t approve of school dinners. She reckoned they served factory-farmed meat, and they had chips too which she insisted were really unhealthy. Jamie went positively dewy-eyed over the very thought of a school dinner.

‘Shall I make some toast for him?’

‘No, Gemma. Absolutely not.’

The last thing we needed was Gemma doing something typically cringe-worthy like sending over food parcels. Having her act of charity rejected, she returned crossly to the stairs and started up her recorder torture again.

Mum came down the stairs like a whirlwind, holding out Jamie’s football gear.

‘Gemma was right! They were in your bed.’

‘You’ve got a ladder in your tights, Mum. A really humungous one,’ remarked Gemma.

‘I haven’t! I have! The keys! Tasha we’re going to be so late!’

We were late. I found Mum’s keys in the fridge. I reckon Dad must have picked them up last night when he’d had the set-to with the ‘squatter’ and then shoved them in there when he’d got the beer. He’d been in a bit of a state.

So we all piled in the car, and just as Mum was trying to persuade it to start … this boy came out of number twenty-five. He shot through the gate that led round to the back garden, bold as brass as if he owned the place. He was really fit actually. I craned out of the back to get a better view.

‘Cor …’ said Gemma.

‘Gems, that is a really vile and vulgar expression,’ I said, signalling violently to her not to draw Mum’s attention to our new neighbour. Mum hadn’t seen him — she’d been too busy battling between the ignition and the choke. I prayed she wouldn’t realize where he’d come from. For all I knew, she’d be out of that car in a flash and doing a citizen’s arrest on him or something.

The car started at last and Mum coaxed it out into the street. He was ahead of us now, sashaying along on rollerblades, dead in the middle of the road, making it impossible for Mum to pass.

‘I don’t believe this!’ she muttered, really losing her cool. She hooted at him but he didn’t take a blind bit of notice. This guy had some cheek.

But Gemma was right — he was well ‘Cor!’ I mean, guys always look good on rollerblades — gives them extra height and all that. But apart from the nice build which I’d noticed as he came out, he had a really OK face too. He wasn’t unshaven as a matter of fact — he was pretty tanned as if he’d just come back from holiday and his hair was kind of rough and sun-bleached. I mean, he was about the best thing I’d ever seen down our street. Squatter or not — he was good news.

A milk float lurched round the corner and approached us. Now any chance of passing him was totally out of the question.

Mum put her hand down on the hooter again.

‘This young man is going to get himself killed if he’s not careful!’

She hooted again and waved wildly at the milkman. The milkman got her drift and went all officious, flagging him down as if he were a policeman. Our rollerblader suddenly came to an abrupt stop, and Mum nearly collided with him. The guy shot a glance over his shoulder and did an ace wobble and double-take, nearly landing on his backside. You should have seen his face!

‘Just what do you think you’re doing!’ Mum yelled at him. She always gets hysterical when she sees someone endangering themselves.

The guy recovered himself and took the two little foam Walkman speakers out of his ears. I could hear the jangle of the bass from inside the car. He must have had it on full blast. No wonder he hadn’t heard the car. The idiot! He stood there looking foolish for a moment. And then he caught sight of me in the back of the car. I was killing myself — silently, so as not to enrage Mum even more. He frowned, obviously realising what a total prat he’d made of himself.

‘Look — do you know the way to West Thames College?’ he asked.

‘I know the way to West London Cemetery — and that’s where you’re heading at this precise moment,’ said Mum.

‘Sorry but — you must’ve come from nowhere!’ he said.

Mum pointed at the head-set. ‘If you want to stay alive, I’d give that a rest if I were you.’

‘Yeah, well maybe …’

‘If I see you doing that again, I won’t be so lenient. I’ll run you over,’ she added.

‘Feel free … Mind how you go now,’ he said. And he waved her on with a flourish.

‘Hmmmph — he’s got a cheek,’ said Mum, but she kind of smiled to herself all the same. Then she thrust the gear lever into second gear and concentrated on getting us through the traffic to school.

OK — school. That first day back is never as bad as you think it’s going to be. You arrive there all ready to muster your reluctant brain-cells and force them back to work, then most of the day turns out to be timetable-planning and book lists and general reorganisation. All of this was carried out by harrassed teachers who were fighting a losing battle against our real purpose of the day — to find out what everyone else did on holiday and go one better.

Melanie deserved the all-time poseur prize because she’d been to the South of France and stayed on her uncle’s ‘yacht’ (i.e. power cruiser, but nobody was splitting hairs). Loads of people had been to Spain and were sporting tans to prove it. Jayce, the rebel of the class, claimed to have been on a caravan holiday with her boyfriend and went into a huddle with some of her mates over the steamier details. Rosie had spent two weeks in Tenerife with her Mum — she’d met this boy and had brought in tons of photos.

I just kept my head down. No-one needed to know about our two-week family walking tour along Hadrian’s Wall, did they? I’d enjoyed it, actually, in a masochistic sort of way. The weather had been fantastic and we’d taken field glasses and seen curlews and sparrow hawks and one day we’d even sighted a falcon’s nest. But I knew from bitter past experience that the very mention of bird-watching would bring the united weight of class scorn down on me.

I’d done an essay, a year or so back, about what I’d done on holiday, and got an A for it. I had to read it out to the whole class with Mrs Manners looking on and smiling indulgently. Dad had taken us to a place called Holy Island. It’s not really an island — its at the end of this causeway, but it’s cut off at high tide. It’s got a castle and an abbey but absolutely nothing else except marsh and sea and birds. I’d felt myself getting hotter and hotter as I read out all this stuff about the abbey and the monks and the curious sense of history in the place. I could hear people fidgeting and giggling beneath the sound of my voice.

That’s when I got friendly with Rosie. She’d come and found me in the cloakroom where I’d gone to get some peace. There’s a place between the coat racks where nobody can see you if you sit really still.

‘It’s OK for you,’ I said, blowing my nose on the tissue she’d given me. You went to Majorca. You’ve got a tan and everything.’

‘Yes, and Mum went out every night and I had to stay in this stuffy hotel bedroom and watch crappy films on the TV. The hotel was full of grossly overweight middle-aged couples getting sunburn round the pool — the women looked like red jelly babies and the men looked like Michelin men and they were all trying to get off with each other. It was disgusting.’

‘You didn’t put that in your essay.’

‘Course I didn’t, stupid.’

Rosie was brilliant like that. She didn’t tell lies exactly, she just knew how to present the truth in the right light for class consumption. If she went to Calais with her Mum on a day trip, she’d let drop that they’d popped over to France for lunch. If a boy asked her out she wouldn’t say he was fit exactly, she’d just find the right way to describe him. I’d got to know her shorthand and how to translate. Tall for his age (i.e. overgrown and weedy). Fascinating to talk to (i.e. gross to look at). Really fit and into sport (i.e. totally obsessed by football).

Anyway, unlikely as it seemed, Rosie and I had teamed up. I had an ally, a conspirator, a protector. However gross the girls in class might be to me, I always had Rosie to have a laugh with.

She was beckoning wildly to me now as a matter of fact.

‘How come you were so late in?’

‘Mum nearly ran someone over. This really gorgeous guy on rollerblades.’

‘She should’ve driven faster — you might’ve got acquainted.’

‘That shouldn’t be a problem. He’s moved into our street.’

‘You’re joking — a fit guy in Frensham Avenue?’

‘Stranger things have happened. Except we think he’s a squatter.’

‘In good old respectable Fren-charm.’ (She was putting on a posh accent). ‘All the local budgies will be falling off their perches in shock.’

‘Yeah well, we’re not sure yet.’

‘I better come’n check him out — like tonight.’

‘OK, you do that.’

I had double Biology at that point and Rosie went off to General Science so I didn’t see her again until after school.

Chapter Three (#ufbc92d8e-ce70-57ff-8971-011421628926)

There was a kind of unspoken feud going on between West Thames College and our school. Our school is an all-girls comprehensive, and it has quite a reputation for getting people into university. I guess the West Thames crowd look on us as swots. We return the compliment by considering them losers. Our status isn’t helped by the fact that we have to wear uniform until we’re in the Sixth Form. So the galling truth — that you’re only in Year eleven or below — is positively broadcast to the nation every time you walk down the street.

On my walk home I always came across groups of West Thames students hanging about in the street. Generally, I tried to ignore them. But today I took an interest. I was hoping to catch a furtive glimpse of our squatter. Most of the students were a lot older and a lot more chilled than us. There was a load of them crowding round a café having a laugh. The girls looked really sophisticated, more like art students. I crossed over to the other side of the road. It was really humiliating to be seen by them wearing school uniform. I’m pretty tall for my age so I look twice as ludicrous as the average girl in mine. My legs are so skinny my gross grey socks slip down as I walk. I could feel them right now subsiding into sagging rolls round my ankles. But there was no way I was going to stop and pull them up with the present audience.

A searching glance through the crowd revealed, to my relief, that there was no-one of his height or colour in the group.

I was continuing on my way down Frensham Avenue dressed in this totally humiliating way when I had that feeling again. The feeling of being watched. The closer I got to home the stronger it got. I glanced up at number twenty-five. I couldn’t see anyone at the windows but I felt positive he was looking down — watching me.

I got inside as fast as I could and slammed the front door.

‘Hi Tasha — want some tea?’

‘No thanks. I’m going upstairs to change.’

‘Have a cup first.’ Mum appeared round the kitchen door. What’s up? Had a bad day?’ It never ceases to astonish me how mothers have such an uncanny knack of reading every tiny intonation in your voice and then drawing a totally inaccurate conclusion.

‘I just want to get out of this,’ I said, indicating the uniform.

‘Have a shower — you’ll feel much better.’

‘Mmm.’

I dragged my clothes off and climbed into the shower. I washed my hair. I let the water run down through my hair and over my face and I did feel better as a matter of fact. I felt as if I was washing away my dreary day and that terrible vision of long lanky me in saggy grey socks. The person who emerged from the shower was new and clean and not half-bad actually — wrapped in my white towelling robe I felt like someone quite different.

I went and lay on my bed for a while in order to savour the feeling. I’d just spend ten minutes or so chilling out before I got down to my homework.

I lay there staring at the ceiling. That guy over the road was just so — fit. I’d never stand a chance. I mean, he was surrounded by dead cool girls, wasn’t he? He’d never be interested in me. Then I got to thinking about that word ‘cool’. The trouble is, if you’re like me, the minute you’ve got the hang of it — like the right clothes and music and language and stuff — you find the whole scene has moved on. And whatever it was you thought was ‘cool’, isn’t any more.

In fact, the truly sad thing is, the harder you try to be ‘cool’, the more it evades you. Like that ghastly time the girls at school were talking about their favourite film stars. I thought I’d be really ‘cool’ and mature so I said Ralph Fiennes. And everyone fell about. I didn’t know you were meant to pronounce his name ‘Rafe Fines’. It would have been simpler if I’d just settled for Leonardo diCaprio or Brad Pitt like everyone else.

One day I’d show them all. I’d be so damn ‘cool’ that everyone would be absolutely begging to come round to my place. I’d have one of those mansions in the hills in LA — all white with pillars and palm trees and a couple of marble swimming pools and a drive-in wardrobe. And I’d give this massive party with guys in uniform ushering limos in. I’d be standing there on the steps wearing this incredible designer outfit with Brad Pitt on one side and Leonardo diCaprio on the other and ‘Rafe Fines’ lurking enigmatically somewhere in the background being incredibly mysterious. All these girls from school would drive up and I’d look at them blankly and say: ‘Hang on a minute — do I know you …’

‘Hi … I’ve come to check out your horny new neighbour.’

Rosie woke me up!

‘Oh no! What’s the time?’

‘Seven-thirty. You look so you’ve been hard at work, I must say.’

‘How did you get up here? Mum in a coma or something?’

My parents generally went ballistic if anyone interrupted the sacred homework hour.

‘Nah, told her we were doing a project together — official visit. So I’ve come to see what he’s like. I hear he’s got a really fit body.’

She had moved over to the window and was staring out in the most obvious fashion.

‘Get away from there, he’ll see you. How come you know so much about his body anyway?’

‘Your kid sister’s put out an official statement. Only a matter of time apparently before you two are an item. She’s chosen her bridesmaid’s dress already.’

‘Gemma! Uggh … You can have no idea what a pain it is to have a younger sister. I’ve absolutely nil privacy. I fantasise sometimes about being an orphan with no family whatsoever. You don’t know how lucky you are.’

‘Yeah well, but brothers and sisters can take the pressure off. Being an ‘only’ means Mum’s investing all her hopes and ambitions in me.’

‘Huh — you can wind her round your little finger.’

‘That’s technique. Taken years to perfect. Sod-all going on over there — budge over.’

Rosie grabbed a pillow and settled herself down end-to-end on my bed. She leaned over and shoved a CD in my player, then sat well-prepared for a girly chat.

‘So … what is he like?’

‘Turn it down a bit — they’ll hear.’

‘God, I’d give anything for a ciggie — do you think they’ll notice?’

‘Yes, Dad’s got a built-in smoke detector up his nostrils.’

‘OK, shoot. Is Gemma making it all up? Said he looked like that guy who used to be on Blue Peter — you know …’

‘Tim Vincent? The one she nearly died of a crush over? She needed counselling when he left the programme …’

‘Well is he …?’

‘Nah. He’s a bit more mature-looking than that. Not so baby-faced.’

‘Mmmm … Tell me more.’

I suddenly had an insight that if Rosie got in on the act I wouldn’t stand a chance.

‘I didn’t get that good a look at him. Not that fit. Maybe he had dandruff …’

‘You must’ve got a pretty good look at him to notice that!’

‘Look, hold on — we don’t know a thing about him! He’s a squatter for God’s sake and he’s probably really rough. He goes to West Thames.’

‘A squatter who goes to college?’

‘Well, seems like he was going there this morning. I guess it is a bit odd.’

‘Maybe he’s a cleaner there or something.’

‘Mmm.’

Rosie had grabbed my eyelash curlers and was studying her reflection in my hand mirror. She was concentrating on putting the curl back in her lashes.

‘Hey … Something is going on over there.’ She stopped with one lash done — the hand mirror was trained over her shoulder.

I craned towards my window. The boards which had been nailed up over one of number twenty-five’s upstairs windows — the one at the very top, opposite mine — were being split apart. It looked as if someone was trying to break through.

Rosie had leapt from the bed and was hovering by the window.

‘Do we have a sighting?’ I asked.

‘Uh-uh, nothing yet,’ Rosie whispered, waving a hand at me to keep quiet. Then she added: ‘Down lights. Down music. Action!’

I switched the bedside light off and joined her.

The squatter was leaning out and wrenching at one of the boards which was proving hard to shift. He was wearing a torn old T-shirt. The light of the street-lamps had just come on and were catching him from below like footlights.

‘I thought Gems was exaggerating. But he is really scrummy.’

‘Isn’t he just?’

‘So why aren’t you in there, man?’

‘How?’

‘Head over there with a cup of sugar. Enrol him into the local Neighbourhood Watch. Sign him up for the Brownies. Use your imagination!’

‘Small problem.’

‘What?’

‘Mum and Dad have already decided he’s big, bad and not-nice-to-know.’

We were interrupted at that point by a loud ‘Cooooey’ from below. ‘Supper-time!’

We made our way downstairs.

‘Do you want to stay, Rosie? There’s plenty to go round.’

Rosie eyed Mum’s veggiebake, which was standing steaming on the table.

‘Thanks Mrs Campbell, but Mum’s expecting me back.’

Mums cooking was a bit of an embarrassment. I mean, there’s a limit to what you can do with vegetables. I expected Rosie and her mum were having one of those lush M&S meals. I’d seen inside their freezer, it was stacked with stuff — ready-made meals all with posey foreign names. Some people had all the luck.

But it was one of Mum’s better bakes. As a matter of fact, I even had a second helping. When Dad had eaten enough of his meal to put him in a receptive mood, I took the opportunity to ask a few questions.

‘What happens to squatters, Dad? If they’re caught? Do they get fined or go to prison or what?’

‘It depends,’ said Dad. ‘If the property’s derelict and they’re in there long enough, they can establish something called ‘squatter’s rights’. Then it can be really difficult to get them out.’

Gemma eyed me over her food. This was good news.

‘But there must be some way to get rid of them,’ said Mum.

‘If you can prove they’re causing damage or are a nuisance you can.’

‘This one’s not a nuisance. He’s quiet as a mouse. He doesn’t even have lights on,’ said Gemma. ‘I think he’s lovely.’

‘Stop messing about with your food and eat it properly,’ said Mum irrelevantly. Her irritation showed in her voice.

‘I don’t like the horrid black bits. They’re all wibbly.’

The black bits are aubergine and there’s no such word as ‘wibbly’,’ said Mum.

An argument broke out as to whether or not ‘wibbly’ was in the dictionary and Gemma insisted on finding it to check. So the subject was dropped for the time being.

Post-dinner Gemma was on drying-up duty, so I headed back upstairs as fast as I could.

‘Haven’t you forgotten something?’

Mum’s voice floated up from the kitchen.

‘No … what?’

‘Your turn to empty the green bucket.’

The green bucket — the yukk-bucket, or ‘yucket’ for short as we’d renamed it — was Mum’s big bid to save the world. Absolutely everything that didn’t get eaten went into it — the more disgusting the better. Every day it had to be emptied into her compost-maker. This stood in the front garden like a great green dalek. Other people had bay trees or statuettes or nice tubs of flowers in their front gardens. But we didn’t. We had to be different. We had a green plastic dalek standing on guard outside our house — announcing to the whole world that this family was basically peculiar.

‘I’ve got my slippers on. Can’t Jamie do it?’

‘Jamie’s on cat duty this week.’

‘Gemma then.’

‘I’m drying up.’

I tried a new tactic. ‘I’ve got to do my oboe practice.’

Mum was standing at the sink with the yucket in her hand.

‘Well that won’t take all night. What precisely is the problem?’

‘Nothing,’ I muttered and went and collected the beastly thing from her.

I shot out of the front door as fast as I could, praying that our squatter wasn’t looking out of his window at the time. I just knew he was, though. I could feel his gaze positively boring into the back of my neck. It was so mortifying.

Chapter Four (#ufbc92d8e-ce70-57ff-8971-011421628926)

Three whole days went by and I didn’t get a single sighting of him. School was one big yawn once the novelty of starting a new year had worn off. Teachers were starting to put the pressure on. A year to go before GCSEs — now was the time to panic early — big deal. Every day I trudged home with a massive bag full of books. I reckoned I was going to look like the Hunchback of Notre Dame by the time GCSEs had come and gone.

And on Thursdays — the day I had my music lesson — I had to carry my oboe and my music as well. I’d been really keen on the oboe to start with. I’d begun learning on the school oboe years ago, and I’d begged and begged my parents to buy me one of my own. I’d even saved up part of the cost myself. At the time the idea of getting into the school orchestra had seemed the ultimate in achievement. I’d really worked hard and got through loads of grades. Miriam my music teacher had started talking about applying to a music school.

But recently I was beginning to have second thoughts. The orchestra wasn’t such great shakes anyway. Nearly all the girls wanted to play woodwind — we always had loads too many flutes — and the strings were dreadful. Now I was in Year Eleven everyone was really dismissive about the orchestra. You didn’t need to be clairvoyant to realise that playing in it labelled you as a nerd. So I’d taken to carrying my oboe disguised in a big sports bag. Weighed down like this, that I was approaching the shops.

I dropped into the shops every day on my way home from school. I’d devised this plan to survive the week by punctuating it with comfort treats. Sad but true, these pathetic little gestures gave me something to look forward to every day. Monday — first day of the week — generally left me weak from exhaustion, so I’d treat myself to a Creme Egg on the way home. Tuesday it was Pastrami Flavour Bagel Chips to eat in front of Heartbreak High. Wednesday — more than halfway through the week, so cause for body-pampering — a luxury face pack or an intensive hair treatment. Thursday — that was the day I treated myself to a magazine.

Hang on — it was Thursday today.

Rosie was reading a Hello from the racks while she waited for me.

It had become a kind of ritual that Rosie and I would meet in the newsagents every Thursday. If Rosie, say, bought Mizz, I’d buy a J17. and that way we could do a swop when we’d read them. I also had another reason for the ritual. Mum and Dad would have had an absolute fit if they knew I was spending my pocket money on magazines. Sounds pretty innocent doesn’t it? I mean, magazines — it’s not as if I was buying cigarettes or booze or hash or anything. Just think what I could be into at my age.

But it’s not what’s printed in the magazines they fuss about. It’s what they’re printed on. I said we were a pretty peculiar family, didn’t I? Well, Mum and Dad are absolutely paranoid about using paper. They reckon magazines are a total waste of the world’s resources - and as for junk mail …! Don’t start them on that. I mean its virtually a criminal act in our house to blow your nose on a paper tissue. They go on as if you’d been caught chopping down a prime sapling in the rainforest or something.

Anyway, I’d decided to keep the older generation happy with this convenient little fiction that it was Rosie who bought the magazines and I borrowed them from her. We were coming back from Mr Patel’s that evening and exchanging vital chunks of media gossip when Rosie paused and nudged me.

‘Guess who’s right behind us?’

I knew immediately without turning round.

‘Keep walking,’ I muttered to her. I’d made a big plan about how I was going to look when we met. A plan that included a major make-over, newly washed hair, sophisticated-but-subtle make-up and my latest stack-heeled sandals. Not as I was at present, in my standard gross school uniform. I even had my hair up to keep it out of the way for my music lesson. It was in ludicrous childish bunches that bounced like spaniel’s ears every time I moved my head.

‘No,’ insisted Rosie. This is our chance to get to know him.’

I could have killed her. I mean, she was looking OK — she’d been home and changed and had her new mini skirt and skimpy T-shirt on. Before I could protest further she’d stopped at the corner. She was loitering really obviously.

‘Hi …’ I heard her say.

I stood, pretending not to be there. I was just praying he’d ignore us and go past. But, no. Thanks a lot, Rosie. He had to stop, didn’t he?

Rosie was going on about how we’d noticed he’d moved into the street, as if we’d been spying on him or something — which we had of course.

‘You read that kind of stuff?’ He was staring at my magazine. I glanced down. It had the most embarrassing headline on the front. The things I’d like to do with boys’ — the kind of headline that’s designed to get you to buy the magazine but turns out to be really tame inside. It would probably be things like roller blading and scuba diving — but it didn’t imply that on the front. I flipped the magazine over.

But he’d seen it already. I could tell he thought it was really, really naff. You could see it written all over his face. I mean, I don’t take these mags seriously — they’re entertainment for God’s sake — a little light relief in my dreary week. But it was just my luck. Not only was I standing there looking like a dog’s breakfast, but I’d come across as a total airbrain as well.

‘Want to borrow it?’ said Rosie, flirting with him like mad. I stared fixedly into the distance. Somehow, ignoring him made me feel less visible.

‘Hardly — its like girls’ stuff, isn’t it?’ I heard him say.

‘So how would you know?’ asked Rosie. She was trying to be witty but the comment fell painfully flat.

‘I wouldn’t know — I mean, obviously,’ he said. And he walked off down the street.

‘Egotist,’ Rosie muttered, watching him as he turned off into number twenty-five.

‘We really made a good impression. I don’t think.’

‘Well, you didn’t have to be so off with him.’

‘If I’d had my way we wouldn’t have spoken to him.’

‘That’s what I mean.’

‘Honestly Rosie, sometimes you can be such a prat.’ I guess I was pretty fed up and I was taking it out on her.

‘So you’re the world’s expert on how to talk to boys, are you?’ she retorted.

‘At least I wouldn’t have offered to lend him a stupid girls’ magazine.’

‘That was meant to be a joke.’

‘Thanks for telling me.’

‘Oh honestly, Tasha. Loosen up. He’s not the only fit guy in the world.’

‘He’s the only one living in my street.’ I stared miserably in the direction he’d disappeared in. ‘I’m never going to be able to face him now.’

‘Oh for God’s sake, Tash. Stop being such a drama queen.’

I hitched my school bag further up on my shoulder. ‘Look, I’ll see you tomorrow, OK?’

‘If you say so.’

I strode off leaving Rosie standing there. We never argued as a rule. But this time she’d gone too far.

Chapter Five (#ufbc92d8e-ce70-57ff-8971-011421628926)

It was some days after this excruciating first encounter that he was sighted again. But not by me this time. It was by Mum.

I was doing my French homework curled up on the sofa. I usually did this downstairs, hoping to glean a little help from Mum’s shaky command of French. She was pretty good on anything to do with food or travel.

I looked up and found her poised with the Hoover mid-way through cleaning the sitting room carpet. She was staring out of the window.

‘What is it?’

She switched the vacuum off.

‘Just take a look at that.’

‘What now?’ I was sorting a particularly difficult bit of past tense into imperfect and passé composé and didn’t want to lose the thread.

Jamie joined her. ‘Huh,’ he said with six-year-old disapproval. ‘He’s drinking out of the bottle.’

‘But it’s what he’s drinking …’ said Mum.

I could resist no longer. I joined Mum and Jamie and stared out as well.

Sitting on the wall outside number twenty-five, there was this boy with his hair shaved round the sides and cut in a sort of slab on top. He was taking swigs out of a bottle — a Smirnoff vodka bottle.

‘What did I tell you?’ said Mum. ‘Let squatters into the street and there’ll be nothing but trouble. I should call the police.’

‘No!’ I said. You can’t do that. He’s probably nothing to do with the house. I expect he’ll move on in a moment.’

This statement was immediately contradicted by the window two storeys above opening. A figure leaned out. It was him.

‘Come on up. I’ve found something better up here.’

I left the window in a hurry and went and sat on the sofa well out of sight.

Mum glared at me. ‘See?’

‘No, I don’t see,’ I said. You’re jumping to conclusions.’

Mum continued peering out of the upper window. ‘Look upstairs. It’s that boy from the other morning. The one I nearly ran down rollerblading. The one who had such a cheek.’

‘Oh … is it?’ I asked, trying not to sound in the least bit interested.

‘He’s our squatter,’ said Gemma, giving me a nudge. ‘Come away, It’s not fair on Tasha to stare at him like that.’

‘What’s going on?’ demanded Mum.

‘Tasha really fancies him,’ said Jamie in a matter-of-fact voice.

Gemma nudged Jamie hard.

‘I do not!’ I said hotly.

‘That would be just so typical!’ said Mum. ‘A girl with no problems whatsoever. Doing well at school. And then someone like that moves into her street and …!’ She paused, peering out again. ‘Oh that’s too much.’

‘So what’s going on now?’ I asked.

‘He’s smoking a big fat cigarette,’ said Jamie.

‘Stay well away from them. That’s all I’m going to say,’ said Mum. She started vacuuming again in a haphazard way with one eye on the window.

Mum thinks she knows it all. She’s got this part-time job as an educational psychologist. She’s used to seeing kids that have gone off the rails. She spends her whole time sorting out disputes, counselling people who’ve been expelled and helping to fix up places in special schools. I reckon it makes her over-react sometimes.

‘I’m going upstairs where I can get some peace to finish my French,’ I said.

I settled down lying on my stomach on my bed facing the window. My room was in shadow so I knew no-one could see in. The guy with the flat-top haircut was leaning out of the attic window opposite, smoking now. And it didn’t look like an ordinary cigarette. He still had the vodka bottle in his hand. He looked down and waved it in the direction of our living room. He must have caught sight of Mum watching him.

The two boys appeared to be fooling around the ways boys do when they think they have an audience. I could have killed Mum. She must be staring out through the window. And they were certainly making the most of it.

The boy waved the bottle again. It was nearly empty now. How on earth could squatters afford to drink vodka like that? That’s if it was vodka, of course. I was starting to have my doubts. The way the boys were fooling around didn’t look totally convincing to me. The chap with the flat-top haircut was really camping it up. He stood at the window and made his eyes go completely crossed and then fell over flat, backwards. I was killing myself.

Mum must’ve been going ballistic down below.

The falling-over act seemed to conclude the show. They’d disappeared from sight. I wondered what it was like being a squatter. What did they live on? Social Security? Was the house filthy and vermin-infested like Mum said? If I lived in a squat I’d make the place exactly how I wanted it. I’d paint the walls black or silver maybe. Perhaps I’d paint murals all over them — and I’d find things in skips and do them up. It must be absolutely fantastic being able to do exactly what you want with no parents around. Being able to stay in bed as long as you want, for instance — eat what and when you like — play music as loud as you like — go out wherever and however late you like.

My parents are really repressive. I reckon it has a lot to do with the fact I’m the eldest. I haven’t had someone up ahead of me to kind of break them in — establish the ground rules. They’re always easier on Gemma — she can do things I was never allowed to do at the same age. By the time Jamie’s my age they’ll probably have given up rules entirely. It’s so unfair!

The boys didn’t reappear. I rolled over on my back and stared at the ceiling. Out of all the girls in my class I reckon my parents are the strictest. Maybe some of it’s boasting, but from what I’ve heard, other girls my age are allowed to go out loads more than me. They dress up and get into pubs and clubs. My parents would have a fit if I did any of those things. They still think I’m a child.

I sat up and stared at my reflection in the bedroom mirror. I even look young for my age. I didn’t stand a chance with a guy like the one over the road. He’d hardly want to be seen around with some kid.

You know what Mum says? It’s the most depressing and infuriating thing anyone can say: ‘Your turn will come, Natasha.’ Well, I simply don’t believe it. By the time it’s my turn, it’ll be too late.

I lay there for quite a while trying to summon up the energy to finish my French homework. I strained my ears for sounds from the house opposite but I guess the boys must have gone out or something.

It was a warm evening and my window was open. I could hear the anxious cheeping and scrabbling of the house-martins. They made a rough mud nest under the eaves of our house every year. This one was just above my bedroom window. Gemma was doing a nature project on them for school and was always barging into my room to check on them. It had been a bit of a pain to start with, but then I couldn’t help getting involved. This summer the parents had brought up three separate broods of fledglings. So there had been constant comings and goings as the parents tried to keep up with their demand for food. I could see a couple of martins darting back and forth across the street catching insects right now. I loved the way they always looked so neatly dressed in black and white — like an anxious pair of waiters in a smart restaurant, with a load of diners grumbling about the time they took bringing the food. And it wasn’t just the adults who did the work. Later in the year — like right now — the earlier, older fledglings would join in and help feed the younger ones. You’d think they’d prefer to be off on their own somewhere, wouldn’t you? Flying down to Spain perhaps, sorting out where they were going to spend the winter? Instead, they were stuck at home doing chores for Mum and Dad. I’d started to identify with some of those martins over the course of that project.

Gemma had wandered into my room.

‘Hi,’ she said, sitting down on my bed beside me.

‘What’s up? Nothing on TV?’

‘Just wondered what was going on over there.’ She indicated the window over the road.

‘Absolutely nothing.’

‘Oh. Sorry about letting on to Mum.’

‘I’ll survive.’

‘But you do fancy him, don’t you?’

‘He’s all right.’

She leaned towards me and asked in an undertone: ‘Do your knees go to Jell-o whenever you see him?’

‘Go to what?’

‘Jell-o.’ She paused. ‘What is Jell-o?’

‘Jell-o is American for jelly. And no, they don’t as a matter of fact. Honestly, Gem. I don’t know what you see in those books.’

Chapter Six (#ufbc92d8e-ce70-57ff-8971-011421628926)

The school week dragged to an end at last, and Friday found me in my room doing my long overdue oboe practice.

I had a really difficult piece to practise for my next exam. It had this long sustained opening note which you had to count through and keep your breathing controlled until you felt you could burst. I dread to think what I must have looked like while playing it.

On my third attempt it really came out well. The piece was by Albinoni. He’s a genius. If you play his music properly it’s really stunningly beautiful. That’s the funny thing about practice. You put it off and put it off and when you can’t put it off any longer and it comes to doing it — you find you enjoy it. No, not just enjoy It’s as if you’re on another plane when you really get into it. You get to a state when you’re so totally absorbed that you can’t break off …

Like now.

‘Natasha, can you hear me?’

‘Yes Mum … What is it?’

‘Help me with this, can’t you?’ Mum’s voice was muffled. She appeared in her bedroom doorway half-in and half-out of a dress, her best dress.

I put down the oboe and went to rescue her. I gave the dress a tug and her head appeared over the top.

‘Can you keep an eye on Jamie and Gemma? It’s only for a few hours. I’ll be back by 9.30.’

‘But it’s Friday …’

‘Yes, and this is a very important meeting. Might mean promotion.’

‘I’m doing my oboe practice.’

‘Well, that won’t take all night.’

‘Why can’t Dad babysit?’

‘Working late on that river project.’

‘Uggghh.’

‘You can take the two of them to the cinema, my treat.’

‘Big deal. We can go to a U.’

Mum was leaning into her three-piece mirror putting lipstick on. I stood behind her and watched critically.

‘You ought to use a lipliner you know — you’d get a much better shape.’

‘You said yourself you wanted to see Babe,’ she mumbled, rubbing her lips together. They’re doing a rerun at the MGM.’

I had actually. OK, I know it’s pathetic, but I still get a kick out of kids’ films — it’s the one and only compensation for having a younger brother and sister. You can veg out in front of stuff like 101 Dalmatians and pretend it’s for their benefit.

‘Popcorn and ice-cream too?’

Mum put a tenner on the dressing table and then increased the bribe by adding a five pound note.

‘It’s a deal then,’ I said sweeping them up. What time does it start?’

‘You’ve missed the early performance — have to take them to the 7.15. So you can finish your practice first.’

‘Can I stand the pace?’

Mum straightened up and took an assessing look at herself in her full-length wardrobe mirror.

‘How do I look?’

I’ve never liked the dress. It’s a really ghastly oxblood red and that terrible middle aged length that makes you look as if you end at mid-calf.

‘It’s not exactly power dressing, is it?’

‘What do you think I should wear?’

‘Your black suit.’

‘The skirt’s too short.’

‘Rubbish. You’ve got good legs Mum, flaunt them. And you need mascara too.’

It took about half an hour to get Mum looking halfway decent, and I had to lend her my lip-gloss. She took another long assessing look at herself in the mirror.

‘I look like Joan Collins.’

‘Well look how successful she is.’

‘True. And — oh my God! Look at the time! I’ve got to dash. They’ve both had tea. Now make sure Jamie holds your hand anywhere near a road. And …’

‘Mum … Do you think I’m stupid or what?’

‘Or what,’ she said, giving me a hasty kiss.

‘Thanks. Knock ‘em dead.’

‘Do you really think I look OK?’

‘Of course!’

‘Not mutton dressed as lamb?’

‘You looked like lamb dressed as mutton in that red thing. Raw mutton.’

‘OK … Here goes.’

We could walk to the MGM from our house. Jamie and Gemma kept running on ahead so I was forced to run with them. Going with me instead of Mum made it an extra-special treat, and I knew that it was going to be a struggle to stop them getting out of hand.

We arrived at the cinema hot and out of breath to find there was a queue and it had started to drizzle too. We’d hardly joined the tail-end before Jamie started to put the pressure on for me to go inside and stock up with supplies of popcorn.

‘It’s raining,’ I pointed out. ‘It’ll only get soggy. Wait till we’re inside.’

The queue was moving really slowly and there were at least forty people ahead of us. My hair had started sticking to my head in a most unflattering fashion. That’s when Gemma nudged me hard.

‘Look,’ she said.

It was him. He was walking down the road with this incredible girl. She had really high-heeled boots on and a minimal skirt topped by a black leather jacket. And she was walking with him as if she owned him.

They joined the queue opposite ours — the one for White Knuckle, a really tough suspense movie just released. The one I’d been planning to see with Rosie until tonight’s alternative entertainment cropped up.

Gemma looked at me balefully. I ignored her. The last thing I needed was her sympathy. ‘She could be his sister,’ she whispered.

Out of the corner of my eye I could see that the girl had started practically rubbing her body against his. Some sister. Get any closer and she’d be inside his jacket. She kept pulling at his sleeve to get eye contact.

‘Huh,’ I said. All I was interested in at that point was getting into the cinema without being noticed.

But as luck would have it, their queue and our queue coincided at the MGM doors at precisely the same moment.

‘Hi …’ I heard him say.

‘Hello …’ said Gemma.

I vaguely murmured a cross between the two that came out like a painful hybrid ‘Hi-lo”. Hoping that if I didn’t look at him, he wouldn’t look at me, I gazed at the pavement which was dotted with blobs of discarded chewing-gum — riveting.

‘Are you going to see Babe?’ I heard Jamie ask. (Thanks Jamie.)

‘No, as a matter of fact, but I’ve heard it’s good …’ he was saying.

There’s a pig in it that can talk and everything.’

‘Really? How do they do that?’

‘Come on Matt. We’re losing our place,’ the girl’s voice whined.

‘Dunno,’ said Jamie. ‘I suppose they must’ve taught it to.’ He was doing everything in his power to prolong this agonising encounter.

‘Must’ve been some bright pig,’ said ‘Matt’. I knew his name now — Matt. He was being really nice to Jamie for some reason.

There was more hassle coming from the girl, who was through the doors by now.

‘OK, I’m coming …’ I heard him say, and then they went ahead of us and bought their tickets and disappeared arm-in-arm into Screen 2.

Gemma gazed after him. ‘He is gorgeous,’ she sighed.

‘But he’s got a girlfriend,’ I pointed out. ‘So forget it.’

Gemma then proceeded to give me the benefit of worldly-wise advice gleaned from her obsessive romance reading — like how ‘true love’ always had to overcome all sorts of totally impossible obstacles which made it all so much more worthwhile in the end.

‘Thanks a lot Gem, that’s a big comfort.’

I didn’t have the heart to point out that, in real life, guys like him went out with girls like the one he was with — and girls like me went to see Babe with their kid brother and sister.

Chapter Seven (#ulink_c4cd2819-8594-5818-a0fb-d3a68b8fec2b)

Saturday morning. Mum likes to use Saturdays to catch up on chores. So it had become a sort of ritual that Dad and I should make the routine shopping expedition to the supermarket. I had an ulterior motive, of course, like making sure decent shampoo and conditioner found its way into the trolley, not just family stuff — and slipping in things like Fruit Comers and Coco Pops when he wasn’t looking. If Dad had his own way he’d come out with an entire trolley of unwashed, unwrapped, organically-grown fruit and veg. He has this real thing about packaging, keeps ranting on about what a waste of the worlds resources it is. In Dad’s ideal world, we’d all have to juggle our groceries home with our pockets filled with detergent. So for Dad, Saturday mornings at Sainsbury’s isn’t just shopping — its a crusade.

We’d stocked up on fruit and veg and Dad had given a lady who was helping herself to a stash of special mushroom bags a lecture on criminal waste — when I spotted Matt.

He was with that alkie guy — the one who looked as if he’d been guzzling vodka on number twenty-fives front wall. The alkie guy actually had an open can of lager in his hand, and between bouts of slopping it everywhere, he was drinking out of it. Their trolley was packed sky-high with booze. A third guy, who was huge and ferocious-looking with matted dreadlocks, was tagging along behind. I knew Dad would throw a wobbly if he saw them. I steered our trolley into safer territory between the cereal aisles and started up a distracting argument about the virtues of Kelloggs versus Own Brand Cereals. I knew this would get him going.

‘They’re all made by the same people, Natasha.’

‘No they’re not. Says so on the packet.’

‘It’s basically the same stuff inside, though.’

‘It can’t be.’

Dad was well into a tirade against branded goods when we moved on to Jams and Preserves. Since it was Saturday morning the place was pretty crowded. At this rate I just might get Dad out of the supermarket without him spotting the guys.

All went well as we went full steam ahead through tinned foods and stocked up on pasta. Nearing the end of the maze of aisles, we reached pet foods. I was reminding Dad of the varieties of cat food that Yin and Yang would or would not currently eat.

‘What do you mean, they’ll eat Chicken & Rabbit but not Chicken & Turkey? Those can’t taste much different.’

‘Maybe they read the labels.’

‘Well, they’re getting Own Brand. I’ve never heard of brand-conscious cats.’

‘That is so unfair; Dad. They don’t do Own Brand Salmon & Shrimp — and that’s their favourite.’

‘One tin, Natasha — for a treat. And that’s their lot.’

So all we had left to do now was detergents. We rounded the top of the Shampoo and Soaps aisle and as luck would have it, there they were. The alkie guy with the flat-top haircut was throwing his weight around, having some sort of argument with one of the shelf-stackers. He had him by the lapels.

Dad stopped in his tracks.

‘Just look at that,’ he said. ‘Disgusting.’

‘Mmmm,’ I said.

But Dad hadn’t homed in on the aggressive little scene in Wines and Spirits. His interest was closer to home. He’d picked up a box containing a hideous plastic crinoline lady full of strawberry-scented bubble bath.

‘It’s criminal! An outer pack — an inner pack — about ten grams of high grade coloured plastic — and all to package a teaspoonful of artificial strawberry-scented detergent. Do you know what stuff like this is doing to the ozone layer?’

‘Making a hole in it, Dad,’ I replied dutifully.

‘Too right it is,’ he said, passing the pack to me. He took charge of the trolley and steamed off towards the check-out. ‘Come on, we’re going to take a stand on this one.’ I was left to trail behind carrying the gross crinoline lady.

I’d had scenes like this before. Incredibly mortifying scenes with everyone staring at us as if we’d gone totally insane. Scenes with poor harrassed staff trying to keep their cool and churn out all that ‘the customer’s always right’ stuff they learn in supermarket school, while Dad ranted on making a total prat of himself.

Dad had rounded the bend at the end of Shampoos and Conditioners when we were caught in a knot of people. A traffic jam of trolleys and mums and kids had built up. That’s when we came face to face with them.

The guy with the dreadlocks took one look at what I was carrying, raised an eyebrow and made an ‘isn’t it cute’ face. The guy with the square-topped hairdo raised his can of lager like a salute and he just said ‘Hi.’

‘Hi,’ I said. And then they moved on.

Dad stood there staring after them. ‘Do you know those people?’

‘Yes, no … Umm, one of them lives in our street … I think.’

‘Not that squatter that’s moved into number twenty five?’

Dad didn’t need an answer, my face said it all.

‘Nice friends he’s got. Your mother’s right. You don’t want to have anything to do with them.’

‘Yes, Dad.’

Dad continued positively fuming. We joined a checkout queue and I dutifully started to load the conveyor.

‘And what about that?’ asked the girl, indicating the bubble bath I was holding. ‘Do you want it or don’t you?’

‘Want it? How could anyone want anything as repulsive as that?’ demanded Dad.

The check-out lady looked affronted. She obviously wasn’t used to having people criticising her merchandise. Well, if you don’t want it, just leave it on one side.’

‘I don’t want it. I want to take it through and complain about it.’

‘You’ll have to pay for it first then and get a refund.’

Dad looked as if he was about to explode.

‘You are asking me to pay for this … This … excrescence?’

‘If you want to take it through, yes.’

A little queue was building up behind us. A lady one back, wearing designer sunglasses with gilt bits on them, stopped devouring the ‘Mediterranean Recipe’ card she’d pinched from the rack and gave us a withering glance.

‘I say. Why don’t you just jolly well pay and be done with it?’ she said.

‘Yes,’ agreed a guy three or so people back. We haven’t got all morning.’ He was wearing a tight T-shirt that read ‘Expansion Tank’ across his stomach and didn’t look like the kind of person you’d want to have an argument with. A baby strapped into a plastic seat set up a mournful howl in agreement.

‘I’d like to speak to the Manager.’ Dad was standing his ground.

The check-out lady put her on her little flashing light with a sigh and we all stood and waited.

‘Look mate, why don’t you just pay for what you’ve got and ‘op-it,’ said the bloke in the expandable T-shirt.

I don’t really want to go into the details. Let’s just say we came very close indeed to causing a riot and ended up at the Complaints Desk with an angry crowd gathered round Dad listening to his standard speech on the evils of packaging and the imminent destruction of rainforests and polar icecaps and the inundation of most of the Netherlands. I stood a few yards away, guarding our trolley, praying for an earthquake to cause a gaping hole to appear in Sainsbury’s floor and swallow me up.

And yes, the boys had reached the check-out. They weren’t going to be allowed to miss out on a scene like this. Oh no. They were finding the whole situation most fun. I could see the flat-top haircut guy practically peeing himself. Dreadlocks was doing a pretty good imitation of Dad by the look of it.

Naturally, they took forever going through — one of their crates of lager wasn’t bar-coded and they had to send an assistant back to check the shelves. I’d moved away, hoping to disassociate myself from Dad’s agonisingly embarrassing performance. But my eyes kept gliding back to check if the boys were still watching him.

That’s when our eyes actually met. You read all those corny things about ‘eyes meeting’. I mean, I’d always thought the whole eye-contact thing was a vast overclaim. But even from this distance, I could see that his were greeny-hazel and kind of — intense. They went right through me. To add the ultimate touch to my humiliation, I felt myself blushing. I had to turn round and study a poster for Spicy Thai Prawn Paella to get over it.

When I felt composed enough to turn back, I found they were making for the exit. They’d practically bought up the whole store’s supply of beers. By the look of it they were going to have some party.

Chapter Eight (#ulink_d7aa88ef-bb42-54a4-9474-05205d29be21)

Just so you get the picture of the full extent of my family’s madness, I’ve got to tell you about Dad’s pet project.

Dad’s pet project is up in the loft. He’s taken over the whole loft area and he’s pinned out all the pages of the A-Z road atlas side by side, each page butting to the next so that we’ve got an incredibly detailed plan of London, street by street. He’s working on his own alternative traffic plan. He seems to think that the future of the planet lies in pedal power. So he’s tracing all these little cycle-ways through the city. Most weekends you’ll see us setting out as reluctant researchers on one of his reccies. First Dad on his mountain bike. Then Mum on her old upright. Followed by Jamie and Gemma and lastly me on my cringe-making pink Raleigh. To complete the picture, we all have to wear these really nerdy cycle helmets and pollution masks. Give us ears and we’d look like a group outing of koala bears.

Anyway, the Saturday after Matt had moved in, I happened to be up in the loft with Dad spending an ecological evening. I was helping him by sticking on rows of little green sponge trees and creating parks and open spaces. I’ve got rather fond of Dad’s project over the years. We used to get into long arguments over traffic control. I’m all for a couple of east-west one way systems which take you past all the cool shopping streets, but Dad’s plan is to filter all the traffic south of the river and ban everything from central London apart from public transport, taxis and of course, bikes. On this particular evening we’d designed a ring over-pass right round London that was like a cycle superhighway.

‘What’s that din?’ asked Dad, looking up from the calculations he was feeding into his lap-top.

It was a deep throaty boom-boom-boom that was reverberating through the loft.

‘Umm … sounds like music.’

‘But where’s it coming from?’ He was already making his way down the loft ladder.

I followed, realising only too well what was up. By the time I reached my room he was leaning out of the window staring at number twenty-five.

People were milling round outside trying to get in through the crush round the front door.

‘It’s only a party,’ I said.

‘But listen to the noise!’

‘Oh well, I don’t expect it’ll go on for long.’

‘Hmm,’ said Dad.

It was about 2.00 am when he totally flipped. I hadn’t got much sleep. In fact, I hadn’t got any. I’d wrapped myself in my duvet and sat in the window with the lights off and the curtains closed behind me — watching. I wouldn’t have believed so many people could have crammed themselves into one house. In fact, they couldn’t. There was a constant overflow of people into the garden. They were the kind of people who were a bit of a novelty in Frensham Avenue. It looked like the whole of Camden Market and Portobello Road had decided to migrate south-west. Through number twenty-fives shadowy windows you could see the waving forms of people dancing. I strained into the gloom for a sighting of Matt but it was pretty well impossible to make out anyone in the flickering candlelight.

And then, just as I was giving up and deciding to crawl into bed, I saw her — the girl who had been with him at the cinema. She’d come into the garden and she was sitting on the low wall smoking a cigarette. A few minutes later, he came out. He was standing in front of her saying something. Then he waited for some minutes with his hands on his hips while she obviously said something back. It was impossible to hear any of the discussion against the music. They appeared to be having some sort of argument. He looked as if he was about to make off when she suddenly stood up and slipped her arms around his waist. For a moment he seemed to be pulling away. But then they went into a clinch. You couldn’t really see but I could tell by the way his back was hunched they were snogging. I came away from the window and slumped miserably down on the bed.

That was when I heard Mum and Dad’s door open. Mum was saying to Dad that she’d had enough and that they ought to call the police. Dad was answering back, saying he’d give them one more chance. I heard our front door slam. I was back at the window in a flash.

But someone had got there ahead of Dad. It was grouchy old Mr Levington from number twenty. Mr Levington was about the most miserable interfering old so-and-so you could ever hope not to live next door to. A real semi-detached Sunday morning car washer. The Levingtons were a kind of family joke — Mum claimed that Mrs Levington washed out the insides of their dustbins each week. They had this garden that looked like a municipal park — a square of grass with symmetrical beds all round and all the plants tied to stakes like torture victims. Mum and Dad had an ongoing battle against their putting out noxious weed-killer and poisonous slug pellets. They were the kind of people who thought — if it moves, it must be a pest, kill it.

Mr Levington was having a go at Matt and the girl by the look of it — waving his arms around and saying something I couldn’t decipher. And now Dad had joined him. He was standing in the middle of the road in his dressing gown and slippers — cringe. The worst thing about it was Dad and Mr Levington seem to have teamed up over this one.

Dad had gone right up to Matt and the girl. Matt still had his arms around her but they’d stopped snogging. She took one look at Dad as if he was the lamest thing or two legs and then made off into the house. Matt was gesticulating, talking back. But Dad and Mr Levington stood their ground. It looked like some row. When they left. Matt went back into the house and the music was turned down.

The music stayed turned down for all of ten minutes. And then there was a crash of shattering glass and a load of shouting. The house seemed about to erupt and a kind of people-explosion burst through the front door. It looked as if a fight had broken out.

I heard Dad’s bedroom door being flung open again, and this time he did go down to the phone. I heard him dial three times and wait.

The crowd flooded out on to the street. There were about six massive guys bearing down on someone who had his back to me. He tripped and fell backwards. And then I caught sight of him under a street light. It was Matt. He was getting to his feet again, shouting things, but none of the guys were taking any notice. Then something glinted in the light of a street lamp. One of them had a broken bottle in his hand.

I stood helplessly at the window. I wanted to scream or shout but I stood frozen to the spot, afraid that any sound from me would cause a fatal lunge or slip.

And then, just in the nick of time, two police cars came careering down the road with their blue lights flashing.

I’ve never been so relieved to see a police car in my whole life.

After the police had gone the party broke up. I lay there listening as people left. At last, the final stragglers made their way down the road, kicking cans and shouting to each other and eventually singing in a slurred sort of way as they rounded the corner. Gradually the street subsided into silence.

Number twenty-five was in darkness apart from a single candle flickering in that top room. I wondered whether that was Matt in there and whether he was alone. I wondered whether he was all right. I sat watching the light for a moment. And then it went out.

Chapter Nine (#ulink_2364e30a-2d31-55a5-ba48-7c0184c02441)

I didn’t sleep too well and I was the first up next day. I decided to walk down to the newsagent and get the Sunday paper — do Dad a favour — or maybe it was just an excuse to get a closer look at what the damage opposite had been.