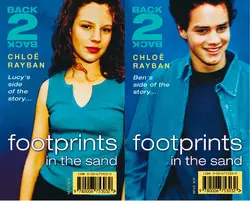

Footprints in the Sand

Chloe Rayban

The first of two exciting titles in the new BACK-2-BACK series. Told with an authentic teenage voice, these stories really hit the right note.Miranda’s story – she’s an only child on holiday with her recently-divorced mother, hoping to get away from it all, but finding herself on a grotty Greek island in the worst hotel ever, where even the Coke is warm! Life is miserable, until she spots a dream-on-a-windsurf, zig-zagging across the bay…Mark’s story – he’s backpacking with a couple of mates and they wind up on a remote Greek island, but some hippies rip off their money and passports. His mates depart but Mark decides to make the most of a bad job – after all, if he works at the taverna he’ll get an hour off every day to windsurf – his passion. He’s noticed the snooty babe in the hotel, so why does she think she’s so great? Can love transform the ugliest of places…?

footprints

in the sand

Lucy’s side of the story…

CHLOË RAYBAN

with grateful thanks toNick Price for his help with the windsurfing

Contents

Cover (#u4df97441-960a-593f-9065-2e2926dbcb7d)

Title Page (#u85090aee-7369-5c52-aa4f-76bf9e18333a)

Chapter One (#ubec9115a-0495-523a-baf3-f820222be665)

Chapter Two (#uf0601fa4-6d58-5e41-8d1d-0373703c9ec8)

Chapter Three (#u24ed1dae-ed1c-5927-888e-cd320d1c5e53)

Chapter Four (#u16dd4711-db70-5995-9276-0a0a10c1b71f)

Chapter Five (#u8744ff9d-8cce-575e-8e30-7e796be2d165)

Chapter Six (#u4148ea6d-e4e7-5791-8ee2-4aa30a152e5d)

Chapter Seven (#u75b920d8-4c55-572a-aad2-59dce78f267d)

Chapter Eight (#ucd62d6ec-e456-52c4-9df2-ea3d391d510e)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter One (#ulink_deef67bb-daf6-5df8-afa4-d15dbd32a707)

‘Mu-um! Have you read this?’

My mother looked up from her reading with one of her intentionally vague expressions.

‘Umm – guide book, yes – no… Not sure. Think so.’

‘You can’t have. It sounds ghastly. Listen to this…’

I put on my official travel guide voice and read:

‘The island’s relative fertility can seem scraggy and unkempt when compared with its neighbours. These characteristics, plus the lack of spectacularly good beaches, meant that until the late 1980s very few visitors discovered Lexos. The tiny airport which cannot accommodate jets still means that the island is relatively unspoilt. Not that the island particularly encourages tourism – it’s a sleepy peaceful place populated mainly by local fishermen.

‘Unusually for a small island, Lexos has abundant ground water, channelled into a system of small lakes. These make for an active mosquito population…’

Mum cut in. ‘Well, it sounds fabulous in this – listen. “Lexos – undiscovered paradise of the Aegean.” Smashing picture too.’

I leaned over her shoulder. She was leafing through a glossy tourist brochure. She thrust the cover under my nose.

‘It’s only a pot of geraniums and a bit of blue sea. It could be anywhere.’

‘Well, I’m intending to enjoy this holiday Lucy – whatever.’

I sat back in the airline seat and put my Walkman on. ‘Undiscovered’ – typical. I reckon she’d done this on purpose.

Neither of us had actually said anything, but we both knew it was going to be our last holiday together. By all rights I would have gone inter-railing with Migs and Louisa – three girls off round Europe together, what a laugh. That’s what I’d intended to do. But just when we’d got all the arguments over our itinerary sorted out, Mum had this phone call…

Dad was getting married again.

I don’t know why it got to her so much, they’d been divorced for years – five years at least. Everything had settled down. She’d seemed perfectly happy. But after the call she got this sort of thin-lipped look on her face, like I remembered from way back, when they separated.

‘You know what you need – a really good holiday,’ I said.

“Yes, you’re right. I do. I know I do. Why don’t we go somewhere right away from it all?’ she said.

‘We’. I hadn’t actually fixed anything with Migs and Louisa. I mean, we hadn’t booked the tickets yet.

She looked at me, all kind of bright-eyed and expectant. So I nodded and left it at that. I hoped she’d forget about it. But then, a day or so later, she came up with this plan. She wanted us both to go to the Greek islands just around the time Dad was due to get married. I had no intention of going to the wedding anyway. I didn’t like Sue, Dad’s ‘partner’ much. And Mum seemed so set on the idea, so I hadn’t the heart to refuse.

But I didn’t expect it to be this far away from it all.

Lexos was really off the beaten track. We flew to a larger island first – Kos. And then we had to travel on by ferry. Dad said I’d love Greece. It was the furthest I’d ever been from England. He said it was the first place where you actually felt the influence of the East. Dad was really into the East. He’d gone overland all the way to India and back when he was young, and he’d kept a ratty kind of embroidered Afghan coat in the loft. I used to dress up in it when I was little. It smelt like a dead goat.

But he was right about Greece. It did have a sense of the East. As soon as I got off the plane I could feel it in the warm dry heat of the sun, soaking into me.

We hired a taxi to take us from the airport to the ferry port, and the driver played this kind of clattering Eastern music on his radio. We drove past little whitewashed churches with strange round domes, and all the old women were dressed like witches in long fluttering black dresses. They held scarves up to their faces to keep out the dust. And the air smelt different. Hot and perfumed with herbs and pine and something sweet and kind of musky. And now and then there was just the odd whiff of dead goat smell. Maybe that was what made it feel Eastern to me – by association with the coat.

The boat trip took hours. We had to queue to board with all these backpackers who looked as if they’d been in Greece all their lives. I couldn’t help noticing that some of the guys were gorgeous. Their skins were a deep bronze and their hair and clothes bleached as if they’d been left out in the sun for months. I felt really self-conscious with my white skin and my brand new jeans and T-shirt – and I was with my mother too. Pretty humiliating.

Mum said we should go up on the outer deck in case it got rough. By the time we got up there, there were no seats left, so we had to sit on the deck and lean on our suitcases. But she was right. It did get pretty rough.

Apparently, there’d been this massive storm the night before. The wind had died down but the sea was still recovering from its effects. After about an hour of being tossed around I started to feel really sick and my head ached. I must have looked sick too, because this old Greek lady leant over and handed me half a lemon. I didn’t know what I was meant to do with it. But she held it to her nose and sniffed and nodded. And I did the same and I felt a bit better. Mum said it was a traditional Greek cure for sea-sickness. So I nodded and sniffed and smiled at the old woman and she laughed and nodded back. We kept up this nodding and sniffing and smiling routine for the rest of the trip.

I’ll never forget my first view of Lexos. Some paradise! But, quite frankly, in the state I was in – any bit of dry land was as good as any other. As we drew nearer, the truly dire condition of the port came into focus. Boy, was it run-down. The buildings were mostly rough squareish boxes of concrete and grey breeze block. Most of them had odd bent ribs of rusty iron sticking out from their flat roofs as if they’d meant to build another storey on top and changed their minds. I think my first impression must’ve registered on my face because Mum was desperately trying to stay positive.

‘Oh look Lucy, there’s a palm tree,’ she said, as her eye lit on the sole acceptable item in the panorama. I was beyond a reply.

I wasn’t actually sick until I got on shore. And then I was, dramatically, behind a cactus. Cheers! Welcome to Lexos, I thought to myself as I took sips from the bottle of water Mum sympathetically handed to me.

After we’d sat at a café for a while and I’d drunk a lemonade, I started to feel a bit better.

‘Well, I hope you don’t think we’re going to stay here,’ I said as I recovered the faculty of speech.

‘Oh, it’s not that bad,’ said Mum, looking fixedly in the direction of the palm tree.

‘Mum – it’s ghastly and you know it.’

‘Let’s get back on the boat then,’ she threatened, pointing to where the last boxes of freight were being loaded into the hold. ‘It’ll be leaving in a minute.’

‘Ha ha, very funny,’ I said. ‘I’d have to be anaesthetized before you’d get me back on that.’

‘Feeling any better?’

‘Mmm… the lemonade helped.’

‘Well, if you’re up to it, I reckon we ought to find the Tourist Office and see if they can suggest somewhere to stay.’

We trekked miles in search of it. Mum kept spotting all these little signs with Ts for Information on them which seemed designed to take us on a scenic tour of the town. I’d never been anywhere so Third World. The roads were cracked and pot-holed and smelt of donkeys, and the few bars or restaurants we came across just had men sitting outside who stared at us. The whole place felt vaguely threatening.

‘I don’t like it here,’ I said.

‘Oh don’t be silly, Lucy. Ports are always like this. It’ll be fine when we get out into the country – you’ll see.’

We must have been walking round in circles because when we eventually found the Tourist Office, it was located more or less where we’d disembarked from the ferry. It was in a forbidding grey concrete block next door to the Customs Office. It had bars over the windows and looked like a prison. But there was a sign outside with the same jolly tourist picture showing the pot of geraniums that we’d seen on the front of Mum’s brochure. I cracked up when I spotted the slogan written underneath: You’ll learn to love Lexos.

‘What’s so funny?’ demanded Mum. I think she was losing her cool by this time.

But when she caught sight of the poster she started giggling as well. ‘Do you think they give indoctrination sessions?’

‘Vee haf vays of making you luf us…’ I said.

The people in the Tourist Office brought out a plastic folder full of pictures of hotels and guest houses. I could see Mum getting hot and bothered trying to calculate how much the prices quoted in drachmas worked out at. She was never any good with noughts. I helped her with the maths and made a few acid comments about the pictures.

They all looked incredibly dreary. I’d wanted to go somewhere like Corfu or Skiathos, somewhere with a bit of life. Clubs maybe. The places they had on offer looked as if they were all in the back of beyond – and I couldn’t make out any guests under the age of about fifty in the photos.

I kept giving Mum meaningful glances and turning the page.

‘Well, if you’re going to be like this, Lucy,’ whispered Mum, ‘we’ll never find anywhere to stay.’

I felt hot and my head ached.

‘How can you possibly tell what a place is like from a photo in a book?’ I whispered crossly. ‘Think of what that poster does for this island.’

Mum glanced at the poster with a sigh and then turned to the girl behind the desk, saying apologetically: ‘I’m sorry. I think we’d better come back later.’ She raised an eyebrow in my direction. I loathed it when she did that.

We trailed back to the café where I’d had the lemonade and Mum ordered two more.

‘Look,’ she said when we’d both cooled down. ‘Let’s hire a taxi and get away from the port. Ports are always dreary. I bet we’ll find a gorgeous beach with a taverna just along the coast. All we’ve got to do is look around a bit, that’s what Dad and I used to do when we came to the islands in the seventies…’

She paused for a moment, and just a shadow of that thin-lipped look came back on her face. I remembered photos in our album of Mum and Dad, young and tanned and carefree on hired mopeds, bumming round the islands. Mum in a ridiculous daisy-printed mini dress and Dad with long hair and John Lennon sunglasses, both totally relaxed and happy together. Looking at the pictures, you’d think that feeling would last forever. Weird how things can change like that.

‘Maybe you’re right,’ I said, picking up my backpack before she could get all emotional and embarrassing. I suddenly felt guilty about being such a pain.

‘I know I’m right,’ said Mum, sounding more like her old self.

‘You’re always right,’ I teased.

‘Come on,’ she said. ‘Let’s make a move then. We’re bound to find somewhere you’ll love.’

We bought cheese pies and honey cakes from the bakery for our lunch, and once I’d eaten I felt loads better. Then we tracked down what seemed to be the one and only taxi on the island.

I think Manos, the driver, must have come from a very large family. At any rate, he had an awful lot of cousins, and we must have visited most of them that afternoon. We started at a five-star hotel. It was a great big pink stone barracks of a place which smelt like a hospital. It did have a pool… but it was empty. Mum turned that down with the excuse that it was too expensive. So Manos must’ve come to the conclusion that we were flat broke, and he took us to his poorer cousins. One had a flat to let that reeked of calor gas and drains. Another had a room with a large decaying double bed and a fridge standing in the middle of the bedroom. And worse still, when Mum said we wanted a place on our own, he took us to what he called ‘a bungalow’ which was a kind of prefab with a compost heap for a garden and a goat tethered outside.

As the sun dipped towards the horizon I was fast losing faith. I hadn’t seen a single decent beach yet.

‘What we really want is a taverna,’ said Mum. ‘A nice, clean, cheap taverna, near a beach.’

‘Oh, taverna!’ said Manos – and he sucked through his teeth as if the very concept of a taverna, was new to him. Then he swung back into the driving seat and shifted noisily into gear. ‘OK, if you want taverna, I take you.’

It was a long drive along a winding cliff road to the other side of the island to find this taverna. I don’t think Manos was in a very good mood. He obviously didn’t have a cousin who owned a taverna, so he wasn’t going to get his cut, or free drinks, or whatever it was he usually received as commission.

Mum had her eyes closed for most of the journey which was a waste because she was on the cliff-side and the views must have been staggering. The sun was going down and it was the most magical sunset. All gold and blue and mauve with puffy little clouds turning candy-floss pink.

It was almost dark when we crunched to a halt in a cobbled square. We climbed out of the taxi. Manos beckoned to us and led us up over a rise.

We were on top of a headland, looking out over the most amazing view of the sea, which had turned a livid copper colour in the low sunlight. We could see for miles, right over to the misty shapes of the neighbouring islands.

Some kind of building was outlined against the sky. It had a corrugated iron roof which looked on the point of caving in and a battered sign surrounded by coloured light-bulbs, most of which didn’t work, which read: TAVERNA PARADISOS.

‘Perfect,’ said Mum.

Chapter Two (#ulink_00bb85f7-958c-5b08-ac95-54b38d693642)

A fat man with a sagging belly, who I took to be the owner, was lounging on the terrace, wearing a dirty vest and boxer shorts. He had a bottle and a glass beside him, and I reckoned he had been indulging in the contents for some time.

I shot Mum a warning glance, but before it registered, she was already asking if he had a room free.

He leapt to his feet with remarkable agility for a man his size.

‘You want room? I have good room. How long?’

‘Oh I don’t know – a week? Ten days maybe?’

‘Best room! Best price! Private facilities,’ he said.

‘Oh, that’s nice. Can we take a look?’

He ushered us across the terrace as if he was showing us around the Ritz.

I followed. Mum had really lost it this time. The place was awful. It wasn’t what I had in mind at all. It didn’t have a pool or anything, and by the look of it we were the only guests he’d had this side of Christmas.

He was already unlocking a door with a big metal key. The floor was plain concrete. It didn’t have a carpet or lino. All there was by the way of furniture were two narrow beds, a three-legged table on the point of collapse and a fly paper hanging from the bare lightbulb. It even had dead flies on it – that was so gross.

‘We can’t stay here,’ I whispered to Mum.

She frowned at me. ‘We can’t keep searching all night. It’ll be dark soon,’ she hissed back.

‘You no like?’ asked the taverna owner, looking sulky.

‘How much is the room?’ asked Mum.

He came out with a figure that was way below anything we’d seen that day. I could see Mum working out the sum in her head and for once – would you believe it? – she must’ve actually come up with the right answer. She raised an eyebrow at me.

‘No, it’s fine, we’ll take it,’ she said.

I shot her another furious glare.

The taverna owner walked out with a satisfied look on his face, leaving us alone together.

‘I can’t believe you said that.’

‘Oh honestly Lucy, what do you want to stay in? One of those ghastly air-conditioned tower blocks full of people on package tours?’

‘Well maybe I would. At least we’d get MTV – this place hasn’t even got a room phone.’

‘Dear, dear, how on earth are we going to order room service?’ said Mum breezily, plonking her suitcase down on a bed.

I sat down on the other bed. It was hard as a board.

‘Come on Lucy, don’t look like that. It’s incredible value. It’ll look lovely with the sun on it in the morning – you’ll see.’

‘Huh!’

‘Well, I’m going to pay the taxi driver and order us some nice cold drinks. We can have them on the terrace and watch the last of the sunset.’

Big deal! I thought as Mum went off with a determined look and her purse in her hand.

The taverna owner served the drinks. He seemed to do everything around the place – show the rooms, check the passports. He even swabbed down the table, brushing the crumbs right into my lap.

When we’d finished our drinks. Mum asked him about dinner.

‘No eat here tonight. No food. Restaurant down in the village.’ He waved a hand in the direction of the cliff-side.

We were both dead tired after the journey. We’d been up at five that morning in order to catch the plane. Mum took one glance at the unlit and perilous-looking steps that led down to the harbour below and said:

‘We don’t want much. Just an omelette will do.’

So he served us reluctantly. We sat at a table with a greasy oilcloth on it. The oilcloth was grudgingly covered by a paper tablecloth which was held in place by a long stretch of what looked like knicker elastic. He wasn’t up to much as a waiter – he just slammed the plates down on the table and refused to cook me chips although they were on offer, chalked up on the board which served as a menu. I wondered if he was always in such a bad mood.

When we’d finished our meal I was still hungry.

‘Ask him if he’s got a yogurt or something,’ suggested Mum.

So I went to the kitchen to ask. When he opened the fridge, I saw it was jam-packed. He had plenty of food. He just couldn’t be bothered to cook it. That’s when Mum called him ‘the Old Rogue’. And the name kind of stuck.

There wasn’t a lot to choose from by way of entertainment after dinner. Not even enough light to read by. We had the choice of either sitting and looking at the view on the left of the terrace or the view on the right. Both were equally dark. So we went to bed. Outside, I could hear the thumps and clatter of the tables being cleared. And then the lights went out on the terrace and silence descended on the place – total silence. God this place was bo-ring!

Was it an earthquake? Was it a landslide? God knows what it was! The shock had woken me and I was sitting bolt upright.

‘What on earth was that?’

Mum was awake and dressed, perched on the bed opposite looking equally stunned.

‘No idea.’

The last of the landslide was followed by a deep, guttural chug-chug-chug which echoed through the room. Mum went out to investigate.

A minute or so later she returned. ‘It’s OK. It’s only a dredger.’

‘A what?’

They must be doing some work on the harbour. Making it deeper or something. It’s a rusty old thing – amazing they’ve kept it going.’

‘Sounds healthy enough to me. How long d’you think it’ll keep that racket up?’

‘Oh, I don’t know. Why don’t you get up? It’s a lovely morning.’

‘In a minute.’

I turned over and tried to get back to sleep on the rock-hard mattress. My pillow felt as if it was made of concrete. My right ear was flattened and sore. I doubted whether it would ever regain its normal shape.

I was just dropping off when it happened again. Another deafening landslip of gravel cancelled out any further attempt at sleep, so I climbed out of bed and stomped over to the bathroom. You could hardly call it a bathroom, it was about the size of an airplane lavatory. I paused in the doorway… Hang on. Where was the shower?

‘Mu-um?’

‘What?’ She was rubbing sunscreen into her legs.

‘I thought the Old Rogue said we had a shower.’

‘We have. The tap’s under the towel thingy.’

I went back into the bathroom. On closer inspection, I discovered that the ‘shower’ was just a rusty sort of sprinkler sticking out of the ceiling. When I turned the tap on, water gushed out all over the loo, all over the basin and then drained away through an evil-looking hole in the floor. And what’s more – the water was stone cold.

‘Yuuukkk!’ I said as I climbed out of the icy flood and found a dry bit of floor to towel myself down on. ‘That was just about the most gruesome experience I’ve had in my entire life.’

‘You’ll soon get used to it,’ said Mum. ‘You find showers like that all over the islands. Labour-saving – it washes down the bathroom too.’

‘I think it’s disgusting.’

‘Oh Lucy, don’t be such a killjoy. It’s lovely outside. He’s laid breakfast on the terrace. What do you want? Tea or coffee?’

‘Tea, I suppose. And orange juice.’ I’d had a Greek coffee at the airport. The cup was half-full of muddy-tasting dregs.

‘See you out there, then.’

When I emerged into the sunlight, Mum was already seated at a table in the shade making the best of the ‘breakfast’. We each had a plate with couple of slices of dry white bread, a sliver of margarine and some red jam. When Mum asked for orange juice, we were each presented with a Fanta.

‘Well I suppose we can’t expect much at the price we’re paying,’ said Mum when the Old Rogue was out of earshot.

‘Now you can see why we’re the only ones staying here,’ I remarked grimly.

Anyway, after the guy had made it clear that breakfast was over by swabbing down the table all around us, we decided to spend the morning exploring. Armed with swimming things and suntan lotion, a book for Mum and my Walkman, we set off in search of a decent beach.

The nearest beach was in the long bay lying to the right of the headland. But the sand was an unwelcoming black colour and you could see by looking down from the terrace that there was a wide band of weed along the shore which you’d have to swim through to get to open water.

‘Don’t even think about it,’ I said to Mum.

‘But it’s nice and close.’

‘Nice! Imagine what could be lurking in that weed. Crabs or jellyfish or sea urchins.’

At the mention of sea urchins, Mum agreed. I’d trodden on one once and had all these little prickles stuck in my foot which had to be taken out one by one with Mum’s tweezers. It was agony.

‘What about the harbour?’ I suggested.

‘Let’s go down and see.’

So we tried the bay on the left. A flight of rough irregular steps wove its way down through some poor little tumble-down houses. At the bottom there was a pathetic fringe of shingle edged by some rotting fishermen’s shacks. Nets were stretched out on the tarry stones to dry. The air smelt of weed and gently decaying fish.

‘Oh, isn’t this wonderful!’ said Mum brightly. ‘Look Lucy, real fishermen!’

I looked. Some rather depressed-looking whiskery Greeks were sitting barefoot on the beach mending nets.

‘Look at their boats! Oh, it’s all so unspoilt.’

I thought the place could do with a bit of spoiling actually, but I didn’t comment. I suppose the boats were pretty. They were a fading weathered sea-blue, like those trendy kitchen cabinets you get in Ikea – but this weathering was obviously genuine. One of the fishermen was rowing his boat out to sea. He stood up in it and rowed in the direction he was going, leaning forward on the oars in a really weird way.

‘We can’t swim here, it’s all fishy and tarry,’ I pointed out. My new sandals were rubbing a blister on my foot and it was already really hot. I was longing for a swim.

‘There’s probably a beach in the next bay,’ said Mum. ‘We just need to clamber over those rocks.’

The rocks were dark and evil-looking and I didn’t hold out much hope of there being a nice white sand beach the other side. But I clambered after Mum anyway. It took about half an hour to get round to the next bay. And once we got there, predictably enough, we found there was yet another headland to negotiate. I was lagging behind and my blister was rubbed red and raw.

When, at last, we rounded the further point, I could see that there were only more jagged rocks. To top it all, this bay wasn’t as sheltered as the fishing harbour – the sea looked dark and angry as it lashed against the rocks. It didn’t even look safe to swim in.

I was getting really fed up. The Greek sea Dad had described to me was calm, blue, crystal clear – so clear, he said, you could see fish swimming beneath you, twenty metres down.

Mum was up ahead of me, trying to see round into the bay beyond. I tried shouting to catch her attention but my voice was lost in the sound of the sea.

I sat down crossly on a rock and took my sandal off to examine the damage. The blister was throbbing. I dabbled my foot in the water to cool it.

‘Lucy! Come on!’

‘I’ve had enough of this,’ I shouted back.

‘What?’

She turned and started picking her way back over the rocks. ‘What’s up?’

‘I’m hot and I’m thirsty and I’ve got a humungous blister,’ I shouted.

Mum joined me on my rock. ‘It doesn’t look very inviting, does it?’

‘No.’

‘But having come so far…’

‘Look. Anyone in their right mind can see there’s no way there’s going to be a decent beach anywhere round here.’

‘Perhaps you’re right. Maybe we should go back.’

‘At last!’

I climbed to my feet and tried to ease my foot back into my sandal, but it was too painful.

‘Oh Mu-um! I don’t believe this!’

‘What is it?’

‘Tar. I’ve got it all over my new shorts.’

‘Oh Lucy.’

‘Oh Lucy’ – it was the way she said it. Mum had her tired voice on. I could tell she was really fed up too. We made our way back over the sun-baked rocks. I was forced to limp with one sandal on and one foot bare, and I could feel the sole of my bare foot practically griddling on the hot stone.

‘I think we should treat ourselves to a really nice lunch to make-up,’ said Mum, trying to cheer me up in the most obvious way as the harbour came into view once again.

The ‘restaurant’ the taverna owner had mentioned was nothing but a few blue-washed tables and chairs set out in a sloping lopsided way on the beach. The whole place was salt-encrusted and fishy, and by the look of it, salmonella was generally the dish of the day.

But by the time we reached it, I was past caring about food. I just sank down gratefully on one of their rickety rush chairs.

‘All I want is a drink,’ I said.

‘Oh Lucy.’

‘Well, do you seriously want to eat here?’

‘There isn’t anywhere else. Not without climbing up all those steps again.’

I just sat on my chair not speaking. By all rights, I should be stopping off somewhere glamorous with Migs and Louisa – somewhere clean and civilised, sitting at a café in Venice maybe, eating a nice squidgy slice of pizza, with loads of dark and gorgeous Italian boys chatting us up.

‘Well, the dredger’s stopped anyway,’ said Mum.

‘I thought something was missing.’

‘Oh come on Lucy, what are you going to have?’

I sighed. ‘What’s the choice?’

‘Umm…’ Mum peered at the menu, which was all in Greek.

‘I bet it’ll be fish, fish, fish or fish.’

‘There’s nothing wrong with fish.’

‘I loathe fish, as well you know.’

‘You used to love fish fingers.’

‘That was ages ago.’

‘I think we’ll have to go into the kitchen and choose,’ said Mum, after a minute or so. ‘They won’t mind, everyone does that in Greece.’

The kitchen was dark after the bright sunlight outside. It took a moment for my eyes to adjust, and when they did, I found I was face to face with a glass-fronted fridge.

I was right, the choice was fish. There were loads of them, all shapes and sizes, staring back at me. This fish wasn’t cut up into neat white rectangles like it was back home. And it didn’t have batter or breadcrumbs on it. It had heads on, and tails on, and looked as if, ever so recently, it had been swimming around alive and well, unaware that the day’s swim was going to come to such a nasty end.

There was a large lady in a witch dress standing behind the fridge, grinning at us. A gold tooth gleamed in the darkness.

‘I don’t fancy anything if you don’t mind,’ I said with a grimace.

‘Oh Lucy. Don’t be such a wimp, darling, it looks simply delicious. It’s probably just come out of the sea.’

‘Can’t I have chips?’

‘Only chips? Well, if you must. But we didn’t have much to eat last night.’

‘Chips’ll be fine.’

So I had chips and a Coke and Mum had fish and some wine. We sat at a table in the shade not far from the water’s edge. I think the wine must’ve been pretty strong because after a glass or so, Mum kept going on about what a brilliant place it was. She came out with all this ‘unspoilt’ stuff again and droned on and on about how we were getting back to the ‘real Greece’ and how time stood still in this kind of place. It was all that ‘alternative lifestyle’ nonsense that Dad sometimes came out with. I reckon the olds had been brainwashed with it when they were young.

All I could see was that we were sitting on a grotty beach that had several centuries of discarded fishbones and rotting fish heads mixed in among the pebbles. And that there were feral-looking cats hanging around which seemed horribly mangy and possibly rabid. And that the sea looked weedy and oily and fishy and had bits floating in it …

‘Oh look at those children. It must be paradise for them here. It’s like going right back to nature…’ said Mum, absent-mindedly filling her glass again.

I looked. A couple of unhealthily chubby little boys were wading in the rust brown sea. They had a plastic bag with them and they were emptying it into the water a few metres out. A load of bloody-looking fish guts fell from the bag. As they did so, a shoal of tiny fish surrounded them and the water boiled around their legs as the younger fish eagerly devoured the remains of their elders. The boys squealed with delight and tried to catch them with their fingers.

‘Yeah, what’s that phrase? Nature raw in tooth and claw?’ I agreed.

The trek back up the steps to the taverna seemed to go on forever. By the time we reached the top, we were both hot and cross and headachy.

‘Bags first in the shower,’ I said.

‘Don’t be long then. I think I’m going to melt.’

I turned the shower on and nothing happened. When I tried to flush the loo it made a hollow cranking noise and no water came out.

‘That’s it,’ I said. ‘That’s the final straw. I’m not staying here any longer.’ I was near to tears.

‘Oh Lucy. Don’t tell me the water’s off.’

‘Try for yourself.’

I lay down on my bed as Mum tried a range of clanking and cranking, but she had no more luck than me.

‘See?’

She sat down on her bed. ‘Do you really hate it here?’

‘Don’t you?’

‘Well, I suppose it is a bit primitive…’

‘Primitive! It’s positively Stone Age. I’m hot and I’ve got a headache and there isn’t even any water.’

‘Maybe we should have looked further.’

‘Hmmm.’

‘And I really wanted us to enjoy this holiday…’

‘So did I!’

‘I know that next year you’ll be off somewhere with your friends… It could be our last together…’

‘I know, I know…’

‘Listen. If you absolutely hate it here, we could move on…’

‘But you keep saying you really like it.’

‘Not if you’re not happy…’

‘Well, it is a bit cut off…’

‘I suppose I could get on a bus this afternoon and have a look round. There must be other places.’

‘Nowhere could be worse than this.’

‘Well, we could be nearer to a decent beach.’

‘Want me to come with you?’

‘No point in us both going out in this heat. You rest that headache, get a plaster on your blister. Have a sleep.’

‘Thanks Mum.’

Chapter Three (#ulink_40b8bb7f-5125-5e66-81d0-3fa704f2451d)

It was cool in the room. The shutters had been closed all morning to keep the sun out. I lay back and shut my eyes. I heard Mum bustling around the room, collecting her things. As she went out through the door she said: ‘Oh, and Lucy – don’t go out in the sun again. Not till after four. It’s scorching. You’ll get burned.’

‘Mmmm. OK. Bye.’

I lay gazing into the semi-darkness, chasing the tiny squiggles you get in your eyes as they darted back and forth across the gloom. They’re stray cells apparently, being washed back and forth over the eye. I’m fascinated by all that stuff. Mum calls it gruesome. She’s not exactly scientific. I reckon her science education must’ve ended with the life-cycle of the frog. When I told her I wanted to be a vet she nearly freaked out. She claimed I’d got the whole idea from some series I’d seen on the telly and it would wear off. But it is what I want to do – really badly.

My head had stopped throbbing. I listened to the noises outside. The dredger must’ve knocked off for the day and I could now hear all the other sounds of the village. Hens somewhere not too far off. And a donkey braying in the distance – a long cascade of eeyores, like mad hysterical laughter. Then the soft sound of the wings of pigeons as they landed on the roof and started scrabbling and cooing.

I was starting to feel bored. What a waste of all that sunlight out there. I climbed off the bed and went to the door. It wasn’t that hot. Mum was just being over-protective, as usual.

My shorts were hanging on the balcony rail. I could at least try and get the tar off. There was a pump in the vineyard – maybe that worked. I took the shorts and some soap and went and cranked the handle. Sure enough, a gush of water came out.

The shorts were brand new from Gap. They were the first pair of shorts I’d ever had which didn’t make my bottom look big. I’d been really pleased with them. But after five minutes or so of scrubbing with the soap, I’d made the tarry marks bigger and darker, if anything.

‘What you doin’?’

I jumped. The Old Rogue was standing with his hands on his hips watching me, frowning. Maybe I wasn’t meant to be in his vineyard.

‘There’s no water in the bathroom. I was trying to get these marks off.’

He held out a hand. ‘Let me see?’

He took the shorts and made some tut-tutting noises. Then he carried them over to where he had a can of what looked like kerosene. He slopped some on and rubbed the marks. Then he brought them back to the pump, and with a lot of huffing and puffing, soaped the stains and rinsed them out.

‘See – good – like new,’ he said.

The tar had disappeared as if by magic.

Thank you, that’s brilliant.’

‘Parakolo.’

‘Parakolo?’

‘No worries.’ His face broke into a smile. He wasn’t such an Old Rogue really.

‘How do you say “thank you” in Greek?’

‘Efharisto.’

I messed it up the first time, and he repeated the word syllable by syllable.

He was tickled pink when I got it right.

I hung the shorts on the balcony rail to dry in the sun and leaned beside them gazing out to sea. It was a really intense blue – like a mirror-image of the sky, but deeper. There was a lone windsurfer skimming across the bay. My eyes lazily followed it. I’ve always wanted to windsurf. Plenty of girls do. There was a gravel pit not far from home where they gave lessons. But Mum said they were too expensive. That’s the thing about your parents divorcing. You soon discover that two different homes cost a lot more to run than one did. Even though Mum worked too now, we never seemed to have anywhere near as much money as we used to.

Leaning further over the rail, I saw that there was a kind of shack on the beach that I hadn’t noticed before. It had a pile of windsurfers beside it and a sign which said that they were for hire. Civilisation!

Once my shorts were dry, I’d take a closer look at that beach. Maybe, somewhere along that stretch of sand, I could find a big enough gap in the weed to risk a swim.

Half an hour later, I was down on the beach. I cast an eye along the stretch of sand, looking for bathers or sunbathers, but it was deserted. Or was it? At the very far end, almost too far away to see, there seemed to be a few rough tents and towels maybe, hanging between the trees – signs that backpackers had taken up occupation. I thought of the bronzed boys on the boat. Just maybe this wasn’t such a bad place after all.

I drew level with the shack. The sign advertised pedaloes as well as the windsurfers, but I couldn’t see any. The shack was locked up, and on closer inspection, I found a piece of paper was stuck on the window giving the opening times for hire. It was closed between one o’clock and four.

I took off my sneakers and found the black sand was burning hot, so I had to do a hurried hop, skip and a jump down to the water’s edge. The sea felt deliciously cool. Just the right temperature, in fact, and the weed didn’t look too bad close up. There were plenty of gaps to get through.

I hesitated. I was longing for a swim, but a swim is always all the more delicious if you get really hot first. So I spread out my towel quite near to the water’s edge, stripped off to my bikini and stretched out. Not much point smothering myself in sun-lotion – I was going in the water any minute.

I had a compilation tape made by Migs’ brother in my Walkman. It was brilliant, he’d put all my favourite tracks on it. I quite fancied Nick actually. He was quite a bit older than us, going to University next year, so he was hardly likely to take much notice of a friend of his kid sister. But he was always nice to me for some reason.

I lay on the sand soaking in the delicious warmth of the sun, with my eyes closed listening to the tape and having some rather censorable thoughts about Nick…

I woke up to find the tape had come to an end. How long had I been asleep? I’d left my watch back at the taverna. I looked guiltily at the height of the sun. It had moved round quite a bit. My skin didn’t look burnt in the bright light – maybe I hadn’t slept for too long. It would be just my luck to end up looking like a slab of coconut ice – all pink one side and white the other. Maybe I should have that swim. But now the sun was lower, the sea didn’t look half so inviting. I wondered again what was lurking in the weed. Perhaps a better idea would be to turn over and get my back to catch up with my front. I turned over on to my stomach, and as I turned, I caught sight of the windsurfer again.

I watched the little pink and blue sail gliding effortlessly in the steady breeze. It must be so quiet out there, with just the sound of the sea and the wind. The windsurfer hesitated and the sail dipped, then quick as a flash it was up again and the board started off in another direction. The surfer was tacking like a sailing boat, and as he turned and took another tack, I realised he was obviously heading for my beach. I propped myself up on an elbow and slid on my sunglasses to cope with the glare.

As the surfer came closer I could see it was a guy – and quite a nice guy too, as far as I could tell from this distance. It was going to be tricky to tack in to the shore, and I was interested to see how neatly he could do it. As he drew nearer, I became even more interested. He must’ve been here some time because he had a great tan and I couldn’t help noticing, not a bad body. That’s the thing about windsurfing – at least that’s what Migs always said. ‘It tones guys up in all the right places – pecs, six-pack, you name it! Take it up Lucy – and then you can introduce us to all your friends.’

The windsurfer changed direction again, and for an instant he paused and the sail dipped into the sea. In those few seconds that he waited, poised and about to pull the sail up, I got a full view of him. Oh no, this just wasn’t fair. He was absolutely gorgeous, sunbleached hair, nice jaw-line – yes, definitely – he was very, very yummy.

He was pretty close to the shore now and I could tell he’d caught sight of me. To my delight he did an epic wobble and nearly fell off. Wicked! I’d really put him off his stroke.

I just managed not to laugh. Instead, I turned over and put my headset back on and pretended to ignore him. I didn’t turn the tape on though. Through the phones I could hear him beaching the board and dragging it up on the sand. I sneaked a glance. A pair of nice strong feet and ace legs deliciously flecked with golden hairs strode past me. He carried the sail up the beach and then he went back for the board. Closer up he was definitely very good news indeed.

I lay pretending to be absorbed in my music as he stowed the board and then made off up the beach in the direction of the taverna. Our taverna. Maybe he was staying there too…

Brilliant! I sat up and started to gather my things together.

Once back at the taverna, I was half-expecting to find my bronzed windsurfer sitting there, having a drink after his sail, maybe. I ran my fingers through my hair and just prayed I hadn’t burnt myself red as beetroot. But he wasn’t on the terrace. I caught sight of him walking down the path between the vines with a towel round his neck. So he was staying here. Excellent!

Then I suddenly had an awful thought. Oh my God, what if Mum had found somewhere else to stay? Nightmare! Oh curses and damnation! Why had I been such a pain about wanting to move on? It wasn’t such a bad place. I mean, one beach in Greece is very much like another, isn’t it? And the taverna was so cheap. A real bargain. There might even be some money left over for windsurfing and I could start to learn and…

But Mum wasn’t back yet. Did that mean she was still searching – fruitlessly? Or was she held up looking at rooms – fixing up the details – oh pl-ease!

I went into the bathroom wishing there was some magical method of thought-tranference by which I could bring her back. Our shower was working again and wonders will never cease – the water was actually hot.

I had a really good shower and washed my hair. My skin stung as the hot water ran down it. I had overdone it. I just prayed it wouldn’t all peel off before I had a chance to tan. I’d have to be really careful tomorrow.

After my shower, I dressed in my most favourite T-shirt and the pair of jeans that made my legs look longest and went out on to the terrace.

The sun was dipping towards the horizon and promising a pretty spectacular sunset. The evening light shone through the vines, casting dancing shadows across the terrace. The faded blue tables and ancient wicker chairs looked kind of rustic and picturesque.

I sat down at a table nearest the sunset. Even the dredger looked somehow glamorous in this light. The low sun had lit up all its rust, turning it a dramatic burnt ginger colour.

The Old Rogue came out of the kitchen wearing a clean vest.

‘You want drink, yes?’

‘Yes please. Orange.’

‘Portocalada?’

‘Is that orange?’

‘Yes. Greek for orange.’

‘Portocalada?’

‘Yes, good!’ he smiled. He was in a much better mood today. He held out a hand. ‘Stavros,’ he said. ‘What is your name?’

‘Lucy.’

‘Lucy – very nice.’

He was a long time bringing my orange, but when he came back he was carrying a plate as well, with what looked like crispy fried onion rings with a slice of lemon on them.

‘For you, on the house,’ he said.

‘Oh thank you. What are they?’

‘Mezze,’ he said. ‘Good – eat!’

I tasted one. They were hot and crispy and delicious.

‘Good, yes?’ he said, watching me.

‘Very good,’ I agreed.

He was going to be ever so disappointed if we moved on. We’d really be letting him down. I smiled and nodded and sipped my drink and indulged in a silent prayer that Mum had found nothing but chicken-pens and and five-star rip-offs on her search.

Stavros waved an arm towards the sunset.

‘Beautiful, yes?’ he said proudly as if it was his very own sunset ‘on the house’.

‘Fantastic!’ I agreed.

‘Best sunset view in the island,’ he said, and he made his way off back to his kitchen.

It really was, too. A narrow band of cloud was hovering above the horizon, splitting the sunlight into great golden shafts like you see in old-fashioned religious pictures. It was incredible. I mean, Stavros was right. This headland must be the very best place in the whole island to watch the sunset.

As I sipped my drink I heard footsteps on the gravel. I steeled myself to confront Mum. But it wasn’t Mum. It was him… the windsurfer. He did a double-take when he saw me – almost dropped the package he was carrying.

‘Hi,’ he said.

‘Hello,’ I said, in what I hoped was a suitably cool and laid-back voice.

Then he made off down some steps behind the taverna and I heard a door slam. He was staying here. There was no question about it.

There was no way I was going to move on now. My mind raced. How was I going to persuade Mum to stay? Well, there was the sunset for a start.

I climbed down the few steps from the terrace and on to the headland to get an even better view of the last moments. It was only a few metres to a rocky outcrop that stood at the furthest tip. Standing there was like standing on top of the world. I was sandwiched between sea and sky, and the two of them were putting on a performance that was like the biggest firework display and the most dramatic laser show ever.

The clouds were tinted violet and the sun had turned into a great molten ball of fire, sliding down the sky. As the last liquid orange glob of it slipped down into the inky sea I heard Mum’s voice, calling:

‘Lucy… Lucy!’

She was back.

Making my way across to the terrace, I prepared myself for a forceful introduction to a change of plan.

She dumped her bag down on the table. She looked hot and tired. She didn’t look as if she’d had a lot of luck!

I slid on to a chair opposite her.

‘Phew, what an afternoon!’ she said. (I felt sure she hadn’t found anywhere.) But then she leaned forward with a triumphant look on her face.

‘It’s all settled. I’ve found a fabulous place. You’ll love it.’

Chapter Four (#ulink_46ea003f-efce-59ab-9518-564257010db0)

‘I can’t understand why you’ve changed your mind like this,’ said Mum. ‘You couldn’t wait to get out of the place at lunchtime.’

‘Yes, I know but… I went down to the other bay this afternoon. The beach is much nearer and it’s quite nice really.’

‘I hope you didn’t sit in the sun.’

‘Don’t fuss. Mum. I had a closer look. It should be fine for swimming. There are plenty of channels through the weed.’

‘But the beach I’ve found hasn’t any weed at all.’

‘Really?’

‘I’ve left a deposit on the room. Said we’d arrive by lunchtime. If we get up early and pack before breakfast, we can settle up with the Old Rogue and be there by mid-morning.’

‘He’s not really an old rogue. He’s actually quite nice. His name’s Stavros. He brought me some hot crispy onion rings, free with my drink.’

‘This new place has got a proper water heater and everything. We have to share the bathroom, but at least we can have decent hot…’

I leapt on this shred of hope.

‘Oh, we don’t have to share a bathroom, do we?’

‘It’s only with one other room. And that room may not even have people staying…’

‘But I had a hot shower here this afternoon. It was fine…’

‘Is the water on again? Thank God for that. I’m feeling really anti-social.’

She got up and reached for her bag.

‘Mum, do we have to go?’

‘What do you mean – have to go?’

‘Well, it’s not really so bad here, is it?’

‘Lucy, what’s going on? I’ve been half-way across the island in a stuffy bus, searching in the broiling heat. And all because you said you absolutely loathed the pl…’

Mum paused. An arm leaned over and took my glass and empty plate away. It wasn’t the Old Rogue’s arm. It was a nice bronzed one, flecked with golden hairs.

‘Hi,’ he said. ‘Welcome to the Paradisos. My name’s Ben. Can I get you anything?’

Mum looked up and smiled at him.

‘I’d love a glass of white wine. Chilled white wine?’ she said.

‘Coming right up.’

He turned and gave me a half-grin and walked away, disappearing into the kitchen.

Mum sank back into her chair and looked at me wryly. She raised an eyebrow. ‘Oh I get it now,’ she said. ‘A lot can happen in an afternoon, can’t it?’

Half an hour or so later, Mum was sitting on her bed wrapped in a towel. She’d perked up a lot after her shower.

‘It’s not like that, honestly. I haven’t even spoken to him,’ I protested.

‘Does he work here or what?’

‘I don’t know. I wish you wouldn’t keep going on about him. Wanting to stay here has nothing to do with him.’

Mum wasn’t buying that. ‘Oh, I suppose it’s the view of the bay that’s the big attraction.’

‘Maybe it is. There was another fantastic sunset. You missed it.’

‘Lucy, you get sunsets everywhere. You said yourself, there’s absolutely nothing for you to do here.’

‘Yes there is.’ I racked my brain for inspiration. ‘We could hire a pedalo.’

‘I saw the pedaloes on the beach, in pieces. They’re wrecked.’

‘Well, we could hire donkeys then.’

‘Correction, donkey. There’s only one – one of us would have to walk.’

‘You’ve already made up your mind, haven’t you?’

‘I’ve paid a deposit. For two whole nights. And the beach there is far nicer.’

‘How much have you paid?’

‘Umm – two nights, about fifty quid.’

‘Why did you have to go and do that?’

‘It was the only way to secure the room.’

‘Well you could’ve checked with me first.’

‘I think you’ve forgotten, Lucy. It’s because of you we’re moving.’

I could tell Mum was losing her cool. She was right of course, it was because of me.

I tried a new angle. ‘But you said you really liked it here.’

‘I did, yes. But, I don’t particularly want to waste fifty quid. Do you?’

‘It’s only fifty quid.’

‘Only!’

‘No, I suppose not.’

We had a meal down at the port again. It was a warm evening so we sat at the water’s edge. The fishermen were setting out in their boats. Each had a tiny lantern in the bows. They rowed out really quietly and you could see their lights reflecting in the water going further and further out to sea. It was so still, their voices came over the water to us as if they were sitting at the very next table.

The lady at the taverna had cooked a cheese and spinach pie. I think maybe she’d been expecting us to come back – she looked really pleased to see us.

Mum said her fish wasn’t nearly as nice this time. And she noticed the bits floating in the water. She kept going on about them.

‘It’s only weed,’ I said.

She looked at it darkly. ‘You can never be sure.’

When we got back to the taverna Ben wasn’t around.

He wasn’t there next morning either. We packed up first thing and Stavros brought us breakfast. I kept expecting Ben to turn up. I’d felt sure he’d be around and I’d purposely worn my favourite T-shirt – the one that didn’t have a flattening effect. But he must’ve gone off somewhere – windsurfing perhaps. I scanned the bay for a glimpse of his pink and blue sail as I listened to Mum explaining to Stavros why we’d changed our plans. It was really embarrassing.

‘But you say you stay one week – two weeks maybe? Why you change your mind?’ said Stavros in a grumpy voice.

‘I’m really sorry. But you know, my daughter…’ Mum glanced apologetically in my direction. ‘You know what they’re like, young people!’

She was making out it was my fault. That was so unfair!

Stavros frowned and shrugged his shoulders. ‘I make the bill,’ was all he said.

I felt terrible. And he’d been really nice to me.

‘How could you blame it on me?’ I hissed to Mum.

‘Well, what was I meant to say? There was no water yesterday. And honestly, look at the breakfast…’

The dredger started up at that moment, drowning out her voice.

‘Oh yes,’ said Mum in the direction of the dredger. ‘Thanks for reminding me – that too.’

I spread my bread carefully, hoping that maybe, given time, Ben might turn up.

‘Hurry up Lucy. We’ll miss the bus.’

‘I’m not really hungry.’

‘Well, leave it then, I don’t blame you. Perhaps we could have a proper breakfast when we get there.’

‘Mmmm.’

I shrugged my backpack on and followed Mum to the bus stop. We didn’t miss the bus. It was standing waiting in the square. It wasn’t full up either. There were two seats free at the back.

I sat staring miserably out of the window. The bus took off with a lot of honking at some chickens that had wandered into its path. The sun gleamed on the little white dome of the chapel. A dog which was lazing in the sun raised its head and then flopped back again, basking in the warmth. The donkey brayed in the distance. Mum had been right – it was all so unspoilt.

I didn’t see him until the bus had practically turned the bend in the road. He was running along the goat track. He ran effortlessly, as if running was his natural way of moving. God it wasn’t fair. He was so gorgeous.

The place Mum had chosen was miles away. Right on the other side of the island. My heart sank as each kilometre went by. Every one of them taking me further away from Ben. Why on earth had she wanted to go so far? There was no way we’d meet up if we were on opposite sides of the island.

The bus was full of local people – old ladies mostly with bundles and crates who got dropped off at remote bus stops in wind-torn villages in the interior. They were dismal-looking places. There was one in particular where an old granny in a tattered black dress was standing on a corner, screaming something at the passers-by. I wondered what it could be like living in a place like that, year in, year out, until you got really old with absolutely nothing happening – ever. No wonder she was in such a state.

I was really fed up by the time we reached the place Mum had found. The bus dropped us off right beside it. It was a modern brick building, set back from the road standing on its own, in a dusty olive grove. It didn’t even have a view of the sea or anything.

Our room was on the first floor. It led off a communal corridor that was open on one side to the wind. The bedroom seemed small and dark. As Mum drew up the roller blind a white box of a place came into focus. It had a horrid tasteless lino floor.

‘You see, it’s all lovely and new and clean.’

‘But there’s nowhere to sit. No terrace or balcony or anything.’

‘There are some garden chairs in the olive grove.’

I looked out of the window. There were a few broken plastic recliners standing in the dust.

‘So how much is this room?’

‘Well, it’s a bit more than it was at the other place.’

Mum was already unpacking and trying to hang things in the wardrobe, battling with those beastly hanger things that come off in your hand.

‘So if we went back now, it’d come to the same thing in the long run, wouldn’t it?’

‘Lucy, I’ve paid for two nights, so we’re staying here now. Don’t be difficult.’

‘But it’s daft to spend our holiday staying somewhere we don’t like.’

‘I like it here.’

‘No you don’t. I can tell you don’t.’

‘I’m not going to waste fifty pounds. You haven’t even looked around yet. You’ll love the beach. White sand.’

‘Really?’

‘Oh for goodness sake, don’t look like that. Come on, let’s have some breakfast – you’re probably hungry.’

We had breakfast sitting on the broken recliners in the olive grove. Unfortunately, it was a much better breakfast than we’d had at the taverna. Mum kept going on about how much better it was. I made a point of not eating much.

‘I hope you’re not sickening for something.’

‘The butter tastes funny.’

‘No, it doesn’t.’

‘It’s got a kind of rancid goat taste.’

‘Oh honestly Lucy, don’t exaggerate.’

‘But if we really don’t like it here, we could go back after the two nights you’ve paid for, couldn’t we?’

‘I don’t want to spend my whole holiday moving from place to place like a bag lady.’

‘Now you’re exaggerating.’

‘Well, it’s a bore all this packing up and moving around. I came here to relax.’

She slid the back of her chair down and stretched out with a sigh as if to demonstrate her commitment to the place.

A wasp settled on the bowl of jam.

I made more fuss than absolutely necessary about the wasp, and went back to our room to change for the beach.

The beach was about ten minutes’ walk away. We had to cross a stretch of green swampy marshland to get there. There was a wobbly bridge made of planks which crossed a stagnant-looking stream clogged with reeds.

Below us, standing waist deep in the dyke, was an old man cutting reeds. Up on the bank was another fellow who had a sackful of wet reeds and an old chair frame. Oh, local colour! Mum was going to love this. Sure enough, she’d spotted them.

‘What do you think they’re doing?’ she asked.

‘How should I know?’

‘Let’s go and see.’

The chap on the bank was doing something tediously rustic with the reeds. He’d twisted them into long strands. You could see where he’d already woven some of them back and forth to make a new rush seat for the chair.

Mum went into ‘reverie mode’ at that point.

‘It’s just so timeless, isn’t it? You know – I reckon they’ve been making chairs like that since… since…’ She paused. ‘Since chairs were invented,’ she finished.

‘How long ago is that?’ I asked with a yawn.

‘Oh I don’t know – couple of thousand years – more probably.’

‘That must explain why they’re so uncomfortable.’

‘Oh honestly Lucy,’ said Mum, forging on ahead again.

I followed, scuffing up the sand. ‘Well, it must.’

‘See?’ she said when we reached the beach. ‘Isn’t it lovely?’

It was white sand. Acres of it – deserted – not a soul to be seen.

‘Why isn’t there anyone here?’

‘I don’t know. Aren’t we lucky, we’ve got it all to ourselves.’

‘Mmmm.’

I smothered suntan lotion on and lay down on my stomach before Mum could get a good look at my red skin. I wasn’t going to let on, but the skin on my front was still pretty sore from the day before.

Mum stretched out on her towel and took out her book.

‘The sun’s pretty high, so just half an hour and then we can have a lovely cooling swim before lunch,’ she said.

I put a tape in my Walkman and turned it on. Anything to try and put myself in a better mood.

Mum made her usual fuss about the volume. (‘Sounds like people clashing saucepans around – can’t understand why you like that stuff, Lucy.’) So I turned it down a bit. Some holiday this had turned out to be.

It was barely half an hour before Mum started fussing about sunburn, so I agreed to a swim. Or should I say a paddle? We had to walk out about a kilometre before the water got up to our waists. No wonder no-one came to this beach.

‘But there’s no weed,’ said Mum, still trying desperately hard to stress the finer points of the place.

‘And we’re not likely to drown, that’s for sure,’ I commented sarkily.

We had a very half-hearted swim, constantly encountering sandbanks and running aground. And then we went back for lunch and a siesta.

Once back in the room Mum fell asleep almost immediately, but I lay awake staring at the ceiling and silently plotting ways to talk her round. Outside, I could hear the steady rhythmic chanting of the crickets. It really wasn’t fair. There were all those crickets outside, thousands of them by the sound of it, packed tight as bodies on a beach on a hot Bank Holiday, sounding as if they were having the time of their lives. While I was here in positive solitary confinement – except that I had Mum for company. I was starting to feel like those hostages you read about. Locked up with just one other person till they drive you barmy. If this went on much longer, I reckoned I’d start having delusions.

I wondered what Ben was doing. Ben – short for Benjamin, I supposed. I could imagine him now, serving people drinks maybe, at the taverna. A vision of him came into my mind, so vivid it was almost real, of him standing there last night in the gloom…

The low sun had turned him a kind of over-the-top all-over golden colour. I’d had to look away. He’d stood there waiting to take my glass, and when I looked up he was already walking off – but then he turned back slowly and smiled at me. I’d gone hot and cold and tingly all over. It was how he’d smiled. I mean, I’ve got to notice these things. There’s a certain way guys look at you when they fancy you. Kind of eyes halfway between open and closed, trying to look as if they’re not looking, if you know what I mean. We had to go back. I’d get around Mum somehow.

And then I had a dreadful thought. What if someone else had come and taken our room? What if all the rooms in the taverna were booked up? Maybe there was some other girl staying in my room. Who was older. And had a nicer nose…

I stabbed at my pillow and turned over. Oh why had I been such an idiot wanting us to leave like that?

Fate didn’t intervene until that night. I didn’t hear the first one. I woke with a hot itchy feeling on my leg. Switching on the light I discovered that I had the most gigantic mozzie bite.

‘Oh no!’ There was a whole row of them all the way up my leg.

‘Hmm – what is it, Lucy? Why’s the light on?’

‘We can’t stay here! I’m getting eaten alive!’

‘What?’

‘Mosquitoes. Look at them! We’ll get malaria!’

‘Don’t be silly – you don’t get malaria in Greece! Hand me that magazine – I’ll swat it. And put the light out!’

‘How can you see to swat it with the light out?’

‘Well if you don’t put the light out, more will come in.’

‘Too late,’ I announced.

There were already six or seven of the creatures circling round the lightbulb.

‘Oh my God.’

I turned the light out.

‘Oh damn and blast, one’s bitten me now.’

‘Didn’t we bring any mozzie spray?’ I whispered to Mum.

‘No need to whisper. They can’t hear you, you know.’ Mum sounded really cross.

‘But didn’t we?’

‘Didn’t think we’d need it. And besides, that stuff’s so bad for you.’

Mum was such a fanatic about chemicals and things. I could hear her raking through her bag.

‘What are you looking for?’

‘Bite stuff – can’t see a thing.’

‘I’ll put the light on then.’

‘No! Oh bother, think it must’ve fallen out on the beach.’

‘But I’m itching to death!’

‘Put some lick on it. And cover yourself up or you’ll get bitten again.’

We both covered ourselves in sheets, including our faces. I lay in silence, hearing the mosquitoes circling overhead like heat-seeking missiles searching for a target. My bites itched like mad, and I could hear Mum turning over restlessly. Hers were obviously as bad as mine.

After half an hour or so, I turned on to my side.

‘Mu-um?’ I whispered.

‘Hmmm?’

‘Not asleep, are you?’

‘What does it sound like…?’

I lifted the corner of her sheet.

‘There weren’t any mosquitoes at the other place.’

‘Maybe there are now.’

‘No, it’s the fresh water. You know where the swampy bit was, by the beach? They only breed in fresh water. We did mosquitoes last term.’

‘So all that education wasn’t wasted after all.’

‘You have to admit – you liked the other place better, didn’t you?’

There was a moment’s silence and then she answered: ‘Well, yes, OK. I suppose I did.’

‘So what’s the big deal about staying here?’

‘There’s no big deal.’

‘You mean we could possibly go back?’

I could sense Mum staring at me through the darkness.

‘You’re really keen on that place, aren’t you?’

I blushed in spite of myself. I was glad it was dark.

‘Well it was just – so much nicer, wasn’t it?’

Mum leaned over and gave me a hug through the sheet.

‘After two days, yes. Why not? Better give the Old Rogue a chance to calm down first.’

‘Really, honestly, truly?’

‘Well it’s what we both want, isn’t it?’

‘Now she admits it.’

There was another, longer silence.

‘Can’t we go back tomorrow?’

‘Oh Lucy. I don’t know. Maybe.’

‘We could have another swim at that brilliant beach of yours first.’

‘It’s not that brilliant.’

‘Mum, it’s ghastly and you know it.’

Chapter Five (#ulink_926f3332-19bc-5c73-97af-757dd0728a2c)

So we went back the following morning. Mum didn’t even seem to mind about losing the money she’d paid for the second night. And she didn’t want a swim either, so we left straight after breakfast.

We saw the bus coming as we finished our coffee and had to run for it across the olive grove.

The bus driver waited for us, grinning and honking his horn in a teasing manner. Mum and I flopped down in the front seats.

‘Two please, to Paradiso,’ said Mum.

‘To Paradiso!’ said the bus driver. ‘You go back?’

He winked at me. It was the guy who’d driven us here. It was such a small island he obviously recognised all his passengers. It was a nice feeling actually.

‘Yes,’ said Mum.

‘Ahhh! Paradiso. Paradise! Yes?’

‘Yes – I know.’

He leaned forward and switched on his radio full blast, and we set off with the sun glinting through the trees and the music clattering in our ears and the sea dreamily blue in the fresh morning light.

We drove back through the villages we’d passed on the way. Maybe it was the direction of the sun or something, but in the morning light, those villages looked completely different. Between the whitewashed houses, there were flowering plants brightening the place up with totally improbable splashes of colour, colour that plants simply don’t have back home. All the mad old ladies had disappeared and been replaced by younger women who had baskets of bread on their arms. And there were loads of children around, and contented-looking cats and well-fed dogs. And even the men sitting outside the cafés smoking and chatting had a kind of festive look about them, as if they were on holiday like us. I wondered how it could all look so different.

‘Maybe we should have rung first. What if he hasn’t got a room free?’ Mum interrupted my train of thought.

‘Oh no, I’m sure he will have.’

‘I think we should stop off at the next village and check. It’ll be a waste of time going all that way back if he hasn’t.’

I’d been dreading this. What if the rooms were let – they couldn’t be! No way! The very idea of not getting back to the Paradisos after all this effort – it was unthinkable!

‘Mum. Who else in their right mind would want to stay at the Paradisos?’

‘Yes, I suppose you’ve got a point there.’

It was about twelve by the time we reached the square above the taverna. The bus juddered to a halt, and with a gentle sigh of the power brakes, the doors swung open. The dog was still basking, but he’d moved out of the sun and into the shade. The donkey was still there – I could hear it braying a hilarious greeting in the distance. The sun was so bright on the chapel, you couldn’t see the flaking paint. Even the shop with its dusty display of out-of-date Hello magazines and battered sun-hats looked somehow welcoming.

The driver climbed out of the bus and hauled our luggage on to the cobbles.

‘Ahhh,’ he said, stretching out his arms as if encompassing the view of the bay. ‘Paradise!’

‘Mmmm,’ agreed Mum. ‘Isn’t it just.’

We were about to start the trek with our luggage, back down the goat path, when a figure shot out of the shadow of the chapel.

‘No,’ he said.

‘I carry bags for you.’

It was a skinny boy of about fifteen or so. He was wearing peculiar old-fashioned trousers made of cheap material and one of those tourist T-shirts they gave out free at the Tourist Office with the picture and the slogan on it – the one we’d cracked up about. You’ll learn to love Lexos.

He took Mum’s suitcase out of her hands and made a grab for my backpack.

‘No it’s OK,’ I said. ‘I can manage.’

But Mum said: ‘Let him, Lucy.’

The boy lifted Mum’s suitcase on to one shoulder and flung my backpack over the other. He put out a hand for the beach bag I was carrying too. But I shook my head, he was smaller than me. As we followed behind him, I thought Mum was being really crazy. We were on a really strict budget, it didn’t allow for luxuries like porters.

The poor kid was so puny too – I wondered how he could support the weight of luggage from both of us. But he went at quite a pace on the rough track as if he was used to it.

Carefully selecting a clean place, he put Mum’s suitcase down at the top of the steps that led to the taverna and placed my backpack beside it.

Mum was scrabbling in her purse. She came out with a one thousand drachma note and handed it to him. I frowned at her. Typical – she was getting all mixed up with the noughts again.

The boy took the note and hesitated.

‘Yes, take it, thank you. That’s fine,’ said Mum.

He cast a wary glance towards the taverna entrance and then made off.

‘Mum!’ I exclaimed. ‘That was worth over two pounds.’

‘I know,’ she said. ‘Didn’t you see? He looked half-starved.’

‘Yes I did. I don’t know why you let him take our stuff in the first place. Honestly, two pounds for carrying a suitcase fifty metres? I thought we were meant to be on a budget. If you’re going to give hand-outs to every Greek…’

‘He wasn’t Greek. He was Albanian.’

‘How do you know?’

‘His accent. It wasn’t Greek.’

‘To every Albanian then…’

‘Lucy… Don’t you read the papers? Those people – they don’t have anything.’

‘Oh honestly, Mum.’

‘Honestly what?’

‘You exaggerate. He’s probably got a job. He may even work at the taverna…’

An awful thought struck me. What if Ben had left? What if that boy had got Ben’s job? Maybe he’d been sent to wait at the bus stop and drum up trade for the Old Rogue – Stavros.

‘Come on, we’d better go and see if we can get our room back,’ said Mum.

I brushed my hair out of my eyes and followed Mum with a thumping heart. Stavros was sitting alone at a table on the terrace. Ben was nowhere to be seen. The minute Stavros caught sight of us he leapt to his feet.

‘You come back!’ he said, waving his arms about in a wild greeting. ‘You no find other place nothing like Paradisos – no?’

‘No,’ said Mum. ‘I mean yes, we’ve come back. I hope you have a room free?’

‘I have room, your room yes? Best room in the taverna. You like, eh?’

‘Yes,’ said Mum.

‘We like very much.’

‘You like views – quiet, peace, eh?’

The dredger let loose a joyful welcoming cascade of gravel.

‘Umm, quite,’ said Mum suppressing a smile.

‘Oh they not work long. They go. Very soon,’ said Stavros with a dismissive wave towards the bay. ‘Bad for business.’

‘We really don’t mind,’ I said.

‘Siddown,’ said Stavros. ‘You have drinkses. On the house.’

I sat down and cast a searching glance towards the kitchen. At any moment Ben would come out with a tray in his hand and give me that wicked smile of his. I waited.

‘Whaddya want?’ asked Stavros.

Ben didn’t come out. Stavros went to get the drinks himself, and I realised with a sinking feeling that Ben wasn’t there. But maybe he was out windsurfing. He must get some time off during the day.

Ben didn’t come back while we were having lunch either. And he still wasn’t there when we took our bags to our room and started to unpack.

Mum threw the shutters open wide while we did so.

‘Lovely,’ she sighed.

I gazed past her. There was a really good view of the bay but I couldn’t see a windsurfer out there.

‘It really is such a nice room,’ said Mum, unzipping her suitcase.

‘Mmmm.’

I stood at the window, scanning the sea for a glimpse of a pink and blue sail. The sea was a milky blue in the harsh midday sun. Maybe the sun was too hot for windsurfing. The dredger had fallen silent – the workers must’ve knocked off for the day.

‘I wonder what happened to that English boy,’ mused Mum. As if she’d read my mind.

‘What English boy?’ I asked innocently.

Mum stood holding up her sundress and examining it for creases.

‘The one we had to come back for,’ she said, without looking at me.

‘Oh Mum, honestly.’

‘Well, I hope we haven’t come all the way back for nothing.’

Chapter Six (#ulink_cbd84980-1261-5007-90c2-530fcb7a9237)

She was like that. She’d always been like that. She knew instinctively the kind of boys I fancied. It was so maddening. I’d do everything to cover up. I’d send out a massive smoke-screen of negative comments or drop red herrings about some other boy who wasn’t even in the running, but I never fooled Mum.

I lay there on the bed while we were meant to be having our siesta, thinking about it. She always looked kind of crumpled when she was sleeping – but she wasn’t bad-looking really for a mum. One of the best in my class at school, as a matter of fact. How was it that someone who was such a brilliant judge of who I liked could have made such a mistake in her own life? I mean, she must’ve been in love with Dad once. Weren’t you meant to know if you really loved someone? And if you did, wasn’t it meant to last? And if it didn’t last… was it really love in the first place? It was a terrible circular argument which went round and round in my head and never seemed to have an answer.

As I tried to get off to sleep my mind kept swinging back to Ben. I could imagine him right now, sitting outside under the vines, having lunch maybe at the table by the kitchen door. Or sitting with a drink in his hand, in silhouette against the sunlit sea. Maybe he was there now. I strained my ears for the sound of a chair scraping on the concrete or the chink of a knife on a plate. There wasn’t a sound. Where was he? Maybe he had left? I couldn’t just lie there doing nothing. I had to find out.

I crept to the door and peeped out. The sun was beating down from practically overhead. It was the hottest time of day and very still. I had the feeling that the whole village was asleep. Even the chickens were quiet.

Ben wasn’t on the terrace. Nor was Stavros – I could hear his steady snoring coming from a room beyond the kitchen. I went back and lay on the bed again. Oh curses and botheration. I picked up my book and tried to concentrate on reading.

I must’ve fallen asleep. I woke with my face crushed uncomfortably against the book. Mum was still asleep. I glanced at my watch. It was four o’clock. If I left her sleeping I could have a look for Ben in peace, without her interfering.

I tiptoed out of the room and across the terrace in bare feet and picked my way down the long flight of steps that led down to the beach.

The pile of windsurfers was neatly stacked. The shack was locked up and the sign advertising that they were for hire was leaning up against the door. I tried to make out whether the pink and blue sail was rolled up with the others. Did he always use the same sail? I stared at the boards, wondering if his was among them… They all looked identical to me.

That’s when I caught sight of them. Footprints in the sand. Large strong footprints with a fine curve inwards where the foot arched. They looked like male footprints. They were deeply imprinted as if whoever they belonged to had been carrying something heavy. I went up to one and tried my foot in it. Yes, by their size, they were definitely male.

They led down to the water’s edge. And beside them, where the water met the sand, something heavy had been placed down – like a windsurfer’s board.

With a rush of conviction, I felt sure the footprints were Ben’s. Who else could they belong to? The Albanian boy’s feet would be far too thin and puny – and as for big flat-footed Stavros…

I studied the sand for more clues. There was a slight graze in the sand where the windsurfer had been launched. He was out there somewhere, I knew it.

I made my way slowly along the beach, scanning the horizon for a glimpse of pink or blue. No sign of a sail. So I sat down on a rock in the shade, under the very furthest tip of the headland where it jutted out into the sea.

And I waited…

Waves don’t actually move towards the shore. That’s an optical illusion. The waves move through the water but the water stays where it is. Or at least that’s what I’d learned in Physics. Over the next hour or so I had quite enough time to study this puzzling phenomenon. And I added a P.S. to it. Whatever was on top of the waves didn’t move into the shore either – neither plastic bottles, nor bits of weed, nor horny windsurfers.