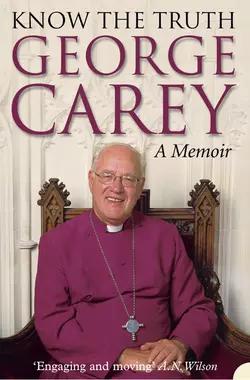

Know the Truth

George Carey

In this remarkable and candid memoir the former Archbishop of Canterbury recalls his life and his spiritual quest; this is the first time in history that an Archbishop of Canterbury has written his autobiography.‘Know the Truth’ tells George Carey’s story from growing up in Dagenham to his experiences in the RAF in the early 1950s, of how he was to become Bishop of Bath and Wells and thereafter attained the position of Archbishop of Canterbury.Utterly sincere and told with warmth and compassion, ‘Know the Truth’ shares George Carey’s story of marriage, family and friendship as well as addressing the wider political aspects of his time at Lambeth.

KNOW THE TRUTH

A MEMOIR

George Carey

COPYRIGHT (#ulink_32e05d1c-1e29-51c4-bc93-f80194598b8e)

Harper Press

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

This edition published by Harper Perennial 2005

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2004

Copyright © George Carey 2004, 2005

George Carey asserts the moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007120291

Ebook Edition © OCTOBER 2012 ISBN 9780007439799

Version: 2016-09-30

CONTENTS

Cover (#u17ea7384-816a-537e-a24e-fe459d185deb)

Title Page (#ue403f6a4-c007-519d-ae13-a584ca835ff8)

Copyright (#uf190663c-f6f3-5e59-a9c0-b7c01fe0a293)

Foreword (#u028677e8-aa95-59d0-9688-058544dda802)

PART I (#u26995365-fe26-5edd-a662-e26682f4ac40)

1 No Backing Out (#ua3526e80-320a-5c3d-80e6-0149c617482c)

2 East End Boy (#u05b29ce2-bc98-5c40-8662-e22771928701)

3 Signals (#u8dbb84f4-7165-58bb-9ed2-d64897a66fb8)

4 Shaken Up (#u2469cfed-d4d4-5464-9d26-bdce24efa798)

5 A Changing Church (#uca1190ea-429e-56cc-ba88-6bb13db82f84)

6 Challenges of Growth (#u5a4b58f6-6e55-51e9-8b2a-0487a54b1da0)

7 Letters from Number 10 (#u6f7a1322-3e91-581b-a21f-4beda9f38b4c)

8 Archbishop-in-Waiting (#litres_trial_promo)

PART II (#litres_trial_promo)

9 Women Shake the Church (#litres_trial_promo)

10 Forced to Change (#litres_trial_promo)

11 Bishop in Mission (#litres_trial_promo)

12 Power and Politicians (#litres_trial_promo)

13 Clash of Cultures (#litres_trial_promo)

14 Empty Stomachs Have no Ears (#litres_trial_promo)

15 The Rosewood Tree (#litres_trial_promo)

16 The Challenge of Homosexuality (#litres_trial_promo)

17 Lambeth ’98 (#litres_trial_promo)

18 Opening the Door (#litres_trial_promo)

19 Rubbing Our Eyes (#litres_trial_promo)

20 From Crusades to Co-Operation (#litres_trial_promo)

21 The Glory of the Crown (#litres_trial_promo)

22 A World in Crisis (#litres_trial_promo)

23 Quo Vadis? (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

FOREWORD (#ulink_c8726d2b-2a82-534b-b370-4324f7d2d031)

When, halfway through my archiepiscopate, I decided to write my memoirs I was surprised to discover that I am the only one of 103 Archbishops to have done so. Admittedly Archbishop Thomas Secker in the eighteenth century set out on the task but his sudden death left his memoirs unfinished. This book is a reflection on a ministry of which Archbishop Cosmo Lang said long ago: ‘The post [of Archbishop of Canterbury] is impossible for any one man to do, but only one man can do it.’ Any holder of this historic office knows from first-hand experience that its demands, expectations and opportunities take one to the edge of human endurance, and require of its holders a recognition of our frailty and our need of God’s everlasting grace.

This edition of Know the Truth gives me an opportunity to comment on some of the reactions of those who have read the first edition.

I might have anticipated that certain sections of the press, and, indeed, a few Church leaders, would focus attention on what I wrote about the Royal Family. I was accused of breaking confidentiality, and one writer even saw this as ‘the ultimate betrayal of trust’. There is no truth in this claim. As will become clear to the reader, no conversation I had with any member of the Royal Family is divulged in the book. I have always kept strictly to the principle of pastoral confidentiality, with the Royal Family and indeed with anyone else. However, what particularly caught the media’s attention was the revelation that I had several private conversations with Mrs Parker Bowles. Again, no report of our conversation is given: all that is offered is my opinion of her as an extremely able and nice person.

Controversially, the book did offer my view that the Prince of Wales should marry Mrs Parker Bowles in due course, and I was delighted when the marriage took place on 9 April 2005 in St George’s Chapel, Windsor. If the uproar caused by my views encouraged their decision to marry I am pleased to have played a small role.

April 2005 also saw the death of Pope John Paul II and the inauguration of Pope Benedict XVI. Pope John Paul II will be remembered as an outstanding Pope and I feel privileged to have known him, and to have worked and prayed with him. If he has left behind him a great deal of unfinished business, it is up to his successor to take forward the hope that his predecessor has given. Scepticism has already greeted the appointment of the new Pope, whose record as President of the Sacred Congregation for the Defence of the Faith does not lead one to expect a great change in policy. However, Joseph Ratzinger has a brilliant mind and a deep love for his Lord. He knows the secular challenges all too well. I pray that he will take risks for the sake of the gospel. His own Church is dying in many parts of the West for lack of vocations to the priesthood. Now is the time to tackle the issue of priestly celibacy and make it optional in the Church, the time to look more sympathetically on the ordination of women and to encourage a healthy debate both within and outside the Roman Catholic Church. Now is also the time to support the action of Catholic agencies in caring for those affected by HIV/AIDS by allowing the use of condoms as part of the strategy to defeat the pandemic. I also suggest that now is the time to make Pope John Paul II’s encyclical Ut Unum Sint a gift to the unity of the Church. Only the Roman Catholic Church, with its pre-eminence in numbers, can do this. Many Christians have become impatient with the slowness of ecumenism and question the amount of time and money going into structural unity at the expense of mission and service.

In the first edition of this book I warned that the consecration of a practising homosexual in the American Church would lead to deep divisions in the Anglican Communion. This has proved the case and the future of the Communion may be bleak if the Episcopal Churches of the United States and Canada continue to assume that they can take unilateral actions on this matter without regard to the rest of the Communion. Events have confirmed my worst fears about the weakness of the Anglican theology of the Church.

Since original publication events have also shown the importance and urgency of the chapter on inter-faith co-operation. I remain convinced that Christians must continue their dialogue with Muslims and Jews in particular, but without forgetting links with other world faiths. Dialogue without friendship, kindness and honest criticism will always remain aloof and bland; with bonds of affection it can contribute substantially to our divided and polarised world.

Few spiritual journeys are ever walked alone. So many people have travelled with me, and I shall remain everlastingly grateful for their patience, kindness, friendship and support. Pride of place goes gladly to my wife Eileen, whose rock-like presence in my life and work is evident throughout this journey. What a great friend she has been over these tumultuous years and what times have we shared together. Then there are our parents who, though out of sight through death, are never out of our minds and grateful hearts. We think of our brothers and sisters whose lives are inextricably linked with our story, and of our beloved children and their husbands and wives, who have shared our joy and pain over some difficult years. Thank you, Rachel and Andy, for your love and care for us at the Old Palace; and Mark and Penny, Andrew and Helen and Lizzie and Marcus – not forgetting thirteen wonderful grandchildren. Thank you, each one of you, for constantly reminding us that life is a gift to be enjoyed.

In the making of this book there are a number of people who should be thanked and appreciated. I am so grateful to Julia Lloyd, who spent a year at Lambeth going through the records and recording speeches, travel journals and staff records in such a way that my task was made much easier. My son Andrew has also been a tower of strength, going over the draft chapters with a careful eye, reminding me of incidents I had forgotten – and in some cases those I wanted to forget! I am grateful to him for his thoroughness, wisdom, insight and incisiveness. Thanks must go to Sir Philip Mawer, Richard Hop-good and Richard Lay for their help with the chapter on the Church Commissioners; to Dr Mary Tanner for her careful insights on the ecumenical chapter; to Canon Andrew Deuchar, Canon Roger Symon and Dr Alistair Macdonald-Radcliffe for their suggestions with respect to the chapters dealing with the Anglican Communion; to Canon Andrew White and Canon David Marshall for positive comments on the inter-faith chapter; and to the Very Reverend Michael Mayne and Sir Ewan Harper for helpful criticisms of the chapter on the Royal Family. I alone am responsible for the use I have made of all the assistance offered; any shortcomings are entirely my fault.

I also wish to record my debt of gratitude to those whose contribution is deeper than I can possibly state. To Dr Ruth Etchells, whose friendship goes back many years, and whose wisdom has always been there and often sought. To Dr James and the Reverend Elisabeth Ewing, two dear American Christians, whose grace has touched the lives of our family so many times over the last decade. To Sir Siggy and Lady Hazel Sternberg and Lord Greville Janner, wonderful Jewish friends whose kindness has reminded me constantly of what we owe to Judaism. In recent years a rich friendship has been established with Professor Akbar Ahmed, a dear Muslim friend, whose scholarship and commitment to dialogue I admire. To Professor Richard McBrien, Professor of Theology at Notre Dame University; Beverley Bra-zauskas; and Professor Gerry O’Collins of the Gregorian University, Rome, for their rich Catholic contribution to our lives.

Finally, I am grateful, too, for the help and professionalism of my editors and the staff at HarperCollins. The final word of thanks must go to God himself. My journey has been one of finding the truth about the Creator through his final revelation in Jesus, the Christ. If my story helps others to find him my unworthy offering will be worth all that Eileen and I have shared together.

GEORGE CAREY

May 2005

I (#ulink_9637179b-3ab7-501c-9b68-f1fed2bc6b8c)

1 No Backing Out (#ulink_03bf28b9-b44b-58bb-9771-c2b44eda01c3)

‘It is perhaps significant that though state education has existed in England since 1870, no Archbishop has so far passed through it. The first Prime Minister to do so was Lloyd George. Nor has anyone sat on St Augustine’s Chair, since the Reformation, who was not a student at Oxford or Cambridge. Understandably nominations to Lambeth have been conditioned by the contemporary social climate, but such a limitation of the field intake is doubtless on the way out. It is inconceivable that either talent or suitability can be so narrowly confined.’

Edward Carpenter, Cantuar: The Archbishops in Their Office (1988)

AS THE DOOR OF THE OLD PALACE BANGED behind Eileen and the family as they departed for the cathedral, I was left alone in the main lounge to await the summons that would most certainly change the direction of my life. At lunchtime with my family around the kitchen table there had been nervous laughter as Andrew, who had had his hair cut that morning, recounted hearing another customer talk about the ‘enthornment’ of the new Archbishop. We all agreed that that was a great description of it, although another of the family volunteered, ‘At least he didn’t say “entombment”.’

Somewhere in the building Graham James, my Chaplain, was sorting out the robes I would shortly wear. From the lounge window I could see and hear the crowds of people teeming around the west front of the cathedral. They were there to capture a glimpse of the Princess of Wales and other dignitaries including the Prime Minister, John Major. I could not help thinking wryly that within twenty yards of where I was standing another Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Becket, had met his death in the same cathedral on 30 December 1170. My journey from this room was not going to lead me to his fate, but it was bound to bring me too in touch with opposition and conflict, as well as with much joy and fulfilment. The massive, enduring walls of the cathedral overshadowing the Old Palace however were a reassuring sign that the faith and folly, the strengths and weaknesses, the boldnesses and blunders of individual Archbishops are enveloped by the tender love of God and His infinite grace.

The television was on in the room, and I could hear Jonathan Dimbleby and Professor Owen Chadwick solemnly discussing the significance of the enthronement of the 103rd Archbishop of Canterbury. Professor Chadwick, a well-known Church historian, was reminding the viewers of the significance in affairs of state of the role of the Archbishop, an office older than the monarchy and integral with the identity of the nation.

Graham swept in with the first set of clothing I had to wear. ‘We’d better get you dressed, Archbishop,’ he said. ‘There’s no backing out now!’

I put on my cassock as I heard Owen Chadwick say that today, 19 April, was the Feast Day of St Alphege, a former Archbishop of Canterbury who, in 1012 ad in Greenwich, was battered to death by Vikings with ox bones because he refused to allow the Church to pay a ransom for his release. It seemed a hazardous mantle I was about to don.

Suddenly a great deal of noise erupted outside, and we walked over to the window to see the Prime Minister arrive with several other Ministers of State. He waved to the crowds and was ushered into the cathedral.

The whole world, it seemed, was present at the service in one way or another. Not only all the important religious leaders in the country – Cardinal Hume and Archbishop Gregorius, Moderators of the Church of Scotland, the Methodist Church and the Free Churches – but also the Patriarchs of the four ancient Sees of Constantinople, Alexandria, Jerusalem and Antioch. Billy Graham was present as my personal guest and as someone whose contribution to world Christianity was unique and outstanding. Cardinal Cassidy represented Pope John Paul II and the Pontifical Council for Christian Unity. Every Archbishop in the Anglican Communion was present, as was every Bishop in the Churches of England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland.

Behind me Dimbleby and Chadwick were now speculating about the new Archbishop. I caught several of the comments: ‘A surprising appointment … he has only been a Bishop less than three years … Yes, an evangelical, but open to others … was born in the East End of London … working class … No, certainly not Oxbridge, but has taught in three theological colleges and Principal of another … comes with experience of parish life as well as being Chairman of the Faith and Order Advisory Group … I think he will be an unpompous Archbishop.’

Mention of my background brought home to me how much I owed to my godly and good parents, who sadly were not here to share in today’s momentous events. How proud, and yet how humble, they would have felt. I smiled to myself as I recalled my mother’s loud comment when in 1985 I was made Canon in Bristol Cathedral: ‘Now I know what the Virgin Mary must have felt like!’ Eileen, rather shocked, wheeled on her: ‘Mum, that’s blasphemy!’ Mother, unrepentant, just smiled.

Yes, how thrilled Mum and Dad would have been; but as realistic Christians they would not be glorying in the pomp and majesty of the day, so much as in the service it represented. They would also be sharing in the tumult of my feelings, and my apprehension as I faced a new future.

Actually, I was not the slightest bit ashamed of my working-class background, which I shared with at least 60 per cent of the population. The popular press had of course milked the story thoroughly, and it was the usual tale of ‘poor boy makes good’ by overcoming huge obstacles to ‘get to the top’. How I hated that kind of language of ‘top’ and ‘success’. It encouraged the stereotype that I was a ‘man of the people’, and therefore in tune with the vast majority of the populace. There was no logic in that, as a moment’s thought should have reminded such journalists that David Sheppard’s background – to take one example of many – did not prevent him from being closely in touch with the underprivileged. Nevertheless, I hoped with all my heart that it was true, and it was very much at the centre of my ministry to represent the cares and interests of ordinary people, with whom I could identify in terms of background.

Some writers, astonishingly, had drawn the conclusion that because I came from an evangelical background my politics were essentially conservative. That was clearly not the case, but neither did it mean that I automatically identified with any particular political party. I saw my role as Archbishop as a defender of the principles of parliamentary democracy. I wanted to support those called to exercise authority, and I would later remind Prime Ministers of both major parties that I saw it as my duty to confront them if they embarked upon policies which I felt undermined the nation in any way.

But what kind of Archbishop was I going to be? As the 103rd Archbishop I was spoiled for choice if modelling myself on any of my predecessors was the way to proceed. Becket feuded so regularly with his King that he spent most of his time in exile. No, that was not for me. The quiet, scholarly Cranmer, perhaps, with whose theology I could identify; but, then again, he was too vacillating and cautious. Nearer my time perhaps one of the greatest of them all, William Temple – scholar, activist, social reformer and inspirer. Yes, a giant among Archbishops, but he was Archbishop of Canterbury for a mere two years during wartime. As a model for this post there were many great men to consider. It struck me that whatever inspiration I received from my illustrious predecessors, I had to be my own man. One thing I could depend upon was that the same divine grace and strength that the previous Archbishops had received was available to me too.

‘It’s time to go, Archbishop,’ said a smiling Graham, handing me my mitre, and then with a prayer we walked towards the door, leaving the television commentary still describing the scene within the cathedral as we advanced to be part of it.

2 East End Boy (#ulink_3b4075b4-2217-5b3a-a8bb-503bcd3f6919)

‘Perhaps more typical of the period after 1940, when the war settled down into the long slog that it became for most non-combatants is the comment of an old lady from Coventry. Asked by her priest what she did when she heard the sirens, she replied: “Oh, I just read my bible a bit and then says ‘bugger ‘em’ and I goes to bed.” ’

W. Rankin

THE WORLD INTO WHICH I WAS BORN on 13 November 1935 was a very troubled and insecure one. The nations were just emerging from the effects of the devastating Wall Street crash that had led to thousands of bankruptcies and to the ruin of many millions of ordinary people around the world. Europe had been badly affected by the Depression, and the rise of fascism was beginning to trouble many. The United Kingdom was not immune from the turmoil and confusion of the period, with unemployment blighting the lives of millions. An absorbing and important sideline was the worrying problem of the monarchy, that would very shortly lead to the abdication of Edward VII and the accession to the throne of George VI.

To what extent my working-class parents shared in these questions and concerns I have no knowledge, although poverty was an abiding reality in our home. Number 68 Fern Street, Bow, London E3, was a typical working-class terrace house, with two bedrooms and a toilet upstairs, and two rooms and a scullery downstairs. I never heard my parents complain about their council home. They kept it clean and were proud of it.

It was a very happy and loving home into which I was born. I was the eldest of five children. Dennis, the twins Robert and Ruby, and Valerie followed at roughly two-year intervals. It was our privilege to have two wonderful parents.

To outward appearances, there was nothing remarkable about them. Their marriage certificate declared that our father, George Thomas Carey, was a labourer at the time of my birth. His schooling had stopped at fourteen years of age, and from birth until well into his teenage years he was the beneficiary of cast-off clothes and shoes. His background was impressive only for the extent of its poverty and deprivation. He was eight months old when his father died in St Bart’s Hospital as a result of an appendicitis operation at the age of twenty-five. His earliest memory was of his mother’s second marriage to an Irish Roman Catholic, a street trader, who was habitually drunk and who often beat his wife when under the influence of alcohol.

In addition to his older brother John, Dad’s mother gave birth to a further eight children. She only married her Catholic husband on the clear understanding that the two sons of her first marriage were brought up in the Church of England faith. She often took them to Bow Church, which to this day occupies a position of prominence on Mile End Road.

My father told me that two moments of his childhood stand out. His maternal grandparents were both born blind, and when his grandmother passed away his grandfather joined this already very large family. The cramped house necessitated grandson and blind grandfather sharing a single bed. A close relationship grew between them, and the old man devoted many hours to teaching the boy to read. My father was encouraged to recite huge passages of the Bible that later in life he could still recall and repeat. At the age of ten, Dad was due to go on a school trip to Regent’s Park Zoo. The day before the trip, Granddad gave his daughter some money, with the mysterious instruction that should anything happen to him, nothing should stop George going to the zoo. Dad was suddenly woken up during the night and transferred into another bed without knowing why. On his return home from the zoo the following day his mother told him gently that his dear grandfather had died in the night with his arms around him. A very special bond was broken – but Dad remained devoted to the memory of his blind grandfather throughout his life.

Dad’s second memory was of a night in his early teens when he was woken by loud screaming and the sound of breaking furniture. Fearfully he crept out of bed, and struggled downstairs. The screaming was his mother’s. Candles were the only form of lighting, so it was with some difficulty that he found his way to her bedroom. Suddenly, confronting him was his stepfather, breathing heavily and clearly the worse for drink.

‘What’s the matter, Georgie?’ came the harsh voice.

‘I heard Mum scream, and it frightened me,’ the boy said.

His stepfather replied, ‘Go to bed, George. Your mother is all right.’

The following day he found out that his older brother had also heard the screaming and had pulled their drunken stepfather off their mother, who had been savagely beaten. He in turn was practically strangled before Nell, one of the stepsisters, was able to rescue him. Mother, son and stepdaughter were thrust from the house and spent the remainder of the night at an uncle’s home. The battered face of his mother the following day told the sorry story of the power of drink in his stepfather’s life. Apparently he could be the most charming of men when sober, but rarely did my father talk of him. There was, however, no mistaking the depth of the love between my father and his mother. Although I have no recollection of her whatsoever, the fragrance of her presence was almost tangible in my father’s life. Few of us realise how lasting is the impact that such caring and close relationships have on our children.

My mother, Ruby Catherine Gurney, came from a more secure and more prosperous working-class home – although the same struggle for existence blighted her life too. Looking at the earliest photos I possess of my mother, she was clearly a good-looking and gentle woman, intelligent, full of life with a great sense of humour. She too was from a large family, and like my father did not have the chance of a decent education.

It was not until many years later that I discovered the extraordinary fact that my mother’s side of the family had close links with Canterbury. My mother’s great-great-grandparents, Thomas and Mary Gurney, were born in Canterbury and baptised in St Alphege’s Church, just fifty yards away from the Old Palace. Their son James was married to Louisa Dawson in the same church on 26 March 1849, and their place of residence was recorded as Archbishop’s Palace, Canterbury. The Gurney family later moved to the East End of London, where my mother was born and grew up. One firm recollection of my parents, sharply etched in my memory, is the fact that they remained in love and cherished one another throughout their lives. I have no memory of them ever having an argument, and with their children they would rely on kindness and good humour to resolve any tense situation.

At some point shortly before the war my parents moved to Dagenham in Essex, which was just as well, as 68 Fern Street was badly damaged during the Blitz. We moved to a larger council house with three bedrooms. The houses around swarmed with young families, and the small number of cars on the roads meant that children could play safely on most of the sidestreets. Impromptu football matches started after school on most days. At the age of five I was enrolled at Monteagle Primary and Junior School, just a few minutes’ walk from home. Later in life I was surprised to discover that my academic year at Monteagle School was not only to yield a future Archbishop of Canterbury, but also a senior officer in the Royal Air Force and the captain of a Cunard liner.

My recollections of those early years are exceedingly vague, and consist of a kaleidoscope of war memories: the excitement of being bundled into underground shelters, the shattering of the calm order of life through three evacuations to Wiltshire, the drone of planes overhead, the sound of the dreaded ‘doodlebugs’ and the destruction they wrought. A tremendous camaraderie developed among the families in our road, and people went to great lengths to support one another, even to the degree of sharing rations if the children did not have enough to eat. Dad became very accomplished at making toffee, and Mum’s cooking became highly inventive, as she had to make do with whatever ingredients she had to hand to produce food for us all. Dad was not called up, but was involved in essential services’, working at Ford’s motor company churning out tanks and armoured vehicles for the army. Often after work he had to take his turn of duty as one of the Home Guard. As youngsters we were tickled pink to see our father donning his uniform, cleaning his Lee-Enfield rifle and parading with other members of his brigade to different parts of the city. In later years I could never watch BBC TV’s Dad’s Army without thinking of my father.

At times in the early days war did seem exciting and rather intoxicating. A sense of urgency gripped the nation, and that feeling of living on the edge of survival penetrated even the world of children of my age. It was impossible to escape the business of war. We knew we were living in desperate days. During the day barrage balloons filled the sky, and the unmistakable traces of fighter-plane tracks high in the heavens were witnesses to the dogfights going on far above us. I became all too familiar with the sound of the ‘doodlebug’, the German V1 rocket, which did so much damage to the East End. I learned that if you could hear it you were safe. It was when the engine cut out that you knew its journey was over, and you had better run for cover. Sadly, my best friend at school, Henry, was badly injured in a doodlebug attack. War invaded our daily lives – everyone, it seemed, had at least one relative in the forces, and at school assemblies prayer was earnest. All children learned how to put gasmasks on, and took in their stride regular visits to the air-raid shelters in the back garden – even though the dirty conditions and the presence of spiders made such times less than appealing.

War also intruded on our diet, in the form of rationing, which affected every person in Britain. Everyone had a ration book, and food was rigidly controlled, with priority given to expectant mothers and children. With five children, my parents had a hard time ensuring that we all received adequate nourishment. But while everyone was hungry in wartime Britain, no one starved. The irony is that, despite people having to go without, on the whole rationing meant that the nation was better fed than it had been in the 1930s. People preferred equality to a free-for-all in which the well-off might stockpile food and the poor starve. Poorer families such as ours were entitled to free school meals. Some of my most exciting memories are of my father saving enough sugar to make fudge for all the family.

There were periods when the level of bombing in London meant that children had to be evacuated to safe country areas. That happened to us three times, but thankfully, at least when we had to leave the security of home – in spite of the dangers of bombs – we had the reassuring presence of our mother with us. Many a London child of my generation has reason to be grateful for the wonderful care of country people who could not have been kinder and more welcoming to the city kids with their unruly behaviour and their ignorance of the ways of rural communities.

There was, however, one terrible experience which was imprinted on the memory of us all, when Mother fell out with a family with whom we were staying in Warminster. A deserter came to the door one day asking for bread, and Mum gave him some. The woman who owned the house was furious with her, and a violent argument ensued. The woman then told Mother that she was totally fed up with us all – we must go. We left in a hurry, and returned to London. But Mum only had enough money to reach Paddington, and Dad had no idea we were on our way home. It was very late in the evening when the train arrived, and we were all wretchedly tired. I remember that the younger ones were crying, and Mum was forlorn and exhausted. Suddenly, to our relief and joy, a neighbour recognised Mum and greeted her: ‘Ruby! What on earth are you doing here so late? Why, you all look in need of a good meal.’ Mum, in tears, explained her predicament, and the good Samaritan bought us all fish and chips and gave us the money to complete our journey home. It was one of those moments forever treasured in our family history. For my parents it was a real sign that ‘Someone’ was watching over us all.

But we could not stay in Dagenham, it was far too dangerous, and once more we were evacuated – this time to Bradford-on-Avon and to a remarkable family, the Musslewhites, whose kindness we always remembered. Mr Musslewhite was the billeting officer and also churchwarden of Christ Church, Bradford-on-Avon. It was his job to match children and families with hospitable homes. I was told by one of his children that when he came face-to-face with Mrs Ruby Carey and her five offspring he was so touched by this very close family that, acting on impulse, he decided: ‘We will take in this family ourselves.’

We stayed with them for several weeks before a house was found on White Hill, which became our home until it was safe to return to Dagenham. Mr Musslewhite and his family also helped us in more than practical ways. He helped to reconnect us with our church, because it was entirely natural to go to his church every Sunday and to enter into the rhythm of worship and praise, community life and the care of one another. For us children it also meant education at the local church school, which we greatly appreciated. Ever since those days Bradford-on-Avon has had a special place in our affections.

I have little recollection of the many schools I must have entered during those years, except the shock of sitting the eleven-plus examination in 1946, and failing it. Of course, most working-class people then – and possibly even today – gave very little thought to such exams. Life had dealt them such a poor hand that they became accustomed to failure and constant disillusionment. I don’t recall my parents being terribly bothered by my failure, but I myself was keenly aware of its momentous significance. Looking back, I am sure that the shock of failing the eleven-plus had a very important part in my later determination to succeed academically. Even at that age I was aware that this exam could determine, to a large degree, the trajectory of one’s life. I was shaken, angry and very disappointed with myself.

So to Bifron’s Secondary Modern School I went. It wasn’t such a bad place for a boy keen to learn, and I quickly made friends. ‘Speedy Gonzales’ was my father’s nickname for me, because I always had my head in a book, and ‘speedy’ was, to be honest, the last thing I was. School reports from the period inform me that I was regularly in the top three places in most subjects. My favourite teacher, Mr Kennedy, a delightful Scot who had entered the teaching profession directly from the navy, taught English. He opened to me the riches of literature, and I borrowed book after book from him. To this day I owe him so much – for teaching me, with his softly-spoken Scottish accent, the power of literature and the need for precision in language. I recall one time when I had to read out an essay I had composed to the class. I felt very proud to be chosen, and weaved into it a few newly discovered words. Suddenly I came to ‘nonchalantly’.

‘What do you mean by that word, Carey?’

‘Well, sir, I think it means “carelessly”.’

‘Then why didn’t you use the word “carelessly”, because all of us know that word better than “nonchalantly”!’

Afterwards, Mr Kennedy said, ‘A good essay, George, but don’t use language to show off!’

And then there was the Headmaster, Mr Bass, who always wrote in green ink. His impact on my life was his belief in me. I remember the time when Alec Harris, my best friend, and I played truant. Alec had been asked by his mother to do some shopping. No shopping was in fact done. With the money burning a hole in his hand, Alec and I went to Barking cinema – known as the ‘fleapit’ – instead, where a horror film banned to children was the main attraction. We attached ourselves to an obliging man and spent Mrs Harris’s money on the tickets, ice cream and sweets. We got our just deserts, because the film was particularly horrible, with realistic scenes of a hand that strangled people. Leaving the cinema, both of us realised the even more horrifying consequences of what we had done. Not only had we played truant, but we had spent someone else’s money on a film we were not entitled to see. Mrs Harris was, not surprisingly, angry, and reported us both to the school. I was caned, but long after the pain had subsided the rebuke in Mr Bass’s voice hurt me more: ‘I am disappointed by you, Carey. You have let yourself down. You are worthy of better things than this.’

What made this incident particularly distressing was that the late forties were very tough for ordinary people. Employment was not a great problem and most men found work quickly, but wages were low, and poverty dogged the steps of most working-class families. Mrs Harris had every right to be profoundly distressed. Luckily I was able to keep the story from my parents, who would have been appalled by my behaviour. As for our family, Dad continued to work at Ford, and brought home just enough for us to pay the rent and get by. Life was hard, but we were a happy family, and entertainment came from fun in the home, close friendships at school, and of course from the radio, or ‘wireless’ as everyone called it.

One day the wireless packed up. We were dismayed beyond measure, but Dad reassured us that we would get a new one, although as we could not afford to buy it outright, it would have to be on hire purchase. I shall never forget the day the salesman came to agree terms with our parents. Soon we would be the proud owners of a new radio, and for the five children it was a moment to savour and look forward to. After the man had left, one look at Dad’s face told the story – he did not earn enough to pay the monthly instalments for a new radio; we had to settle for a second-hand one that Mother bought with some saved housekeeping money the following day. I would not go so far as to say that that incident alone made me conscious of the unfairness of life, and the way that a privileged class controlled the rest of us. It is true to say, however, that the form of Christian faith I espoused later in life had a clear social and political foundation. If it did not make a difference to life, it could never be for me a real faith.

Party politics did not intrude greatly into our home. Mum and Dad were working-class Conservatives, as far as political affiliation was concerned. My father was an intelligent man and enjoyed a good argument. His daily paper was the Express, and every Sunday the People was read from cover to cover. They were Tory papers. He had no time for socialism, believing it to be allied to Communism, and therefore in his view opposed to everything that made Britain great and free. Our parents were also unashamedly royalist, principally, I believe, because the monarchy gave a visible form to British traditions and values.

Nevertheless, even as a young teenager I could not help wondering, as I watched our two happy parents, what the Conservative Party had ever done for them. ‘Look at how poor you are. Look at the way you struggle to make ends meet,’ I thought. I could not understand their acceptance of the way things were. Deep down I felt that there ought to be, indeed must be, a better way.

Shortly after the war we moved again, this time to a three-bedroom council house in Old Dagenham. Our parents had a modest bedroom overlooking the rear garden, which was bigger than our previous one, the girls were in a pokey ‘box room’, and the three boys shared a larger room overlooking the road. It was a house full of noise and fun. Most evenings we listened to the radio which engaged with our imaginations with serials like Dick Barton, Special Agent and many other favourites. We were encouraged to read, and the local library was a great resource. Whenever he had time Dad would disappear into the shed where his tools were stored and make toys for us all. Alas, I never did acquire his practical ability, although my brother Dennis did in abundance.

With romantic notions of the ocean, I decided to join the Sea Cadets at the age of twelve, and I stayed with this great youth organisation until I was sixteen. Admittedly I had to lie to get in, as the minimum age of entry was thirteen, but I was a tall, strong lad and managed to convince the CO that I was old enough. The Sea Cadets helped me to mix with other teenagers and gave me confidence in holding, my own with them.

At thirteen I was able to sit another examination to see if I was up to the level to attend high school, and this time I passed. I can still remember the feeling of happiness. I was not a failure after all. But then came another let-down – my parents visited Mr Bass, and the conclusion of the meeting was that there was more to be gained by my staying at Bifron’s than moving on at that stage. I was not unhappy with the decision, because I was comfortable at the school, was cruising through the classes and had made many friends. The blow was to come when, at the age of fifteen and a half, I had to leave Bifron’s with no qualifications whatsoever. Secondary-modern pupils did not sit the matriculation examination.

This did not bother me at first, because I did not realise the significance of matriculation. My reading had made me thirsty for adventure, and I dreamed of joining the Merchant Navy and becoming a Radio Officer – no doubt the legacy of Mr Kennedy’s tales of his life in the Royal Navy before he became a teacher. The outside world, however, brutally woke me up to reality. For the vast majority of working-class children, school ended at fifteen and work beckoned. So I was suddenly pitched into the world of employment, and became an office boy at the London Electricity Board in East India Dock Road, Bow.

The adult world I now found myself a member of was certainly not dull or lacking interest. On the contrary, it was a bustling, urgent world of caring for customers and serving others. As office boy I was at the bottom of the heap, and the servant of all. At the top of the pile was Mr Vincent, a tall, emaciated figure who swept through the outer offices to sycophantic calls of ‘Good morning, sir! Good morning, Mr Vincent.’ Without acknowledging any of the greetings he would disappear into his office, closing the door sharply behind him.

I fell foul of Mr Vincent in my second week. I was summoned into his office and given instructions to go to a shop in Whitechapel and collect some goods he had ordered. He gave me £5 to cover the cost. I was thrilled at this opportunity to show him that I was up to scratch. I jumped on the bus happily and then, for some reason known only to the brain of an absent-minded fifteen-year-old, I started to clear out my pockets of their debris, discarding some items and shredding others. I arrived at the shop, and after I had been handed the parcel I reached for the note I had put into my top pocket. With mounting horror, I realised what I had done. From my pocket I withdrew – half of a fiver. The shopkeeper refused the tattered remains of the note point-blank, and with panic I returned to face the music, knowing that my job was on the line.

A stern-looking Mr Vincent heard me out in total silence. ‘Now go to the bank,’ he ordered, ‘and in return for the half of the banknote, you may be able to get a new £5 note – otherwise you will have to pay for this yourself.’ As that represented at least two weeks’ salary for an office boy, I was relieved when the bank gave me a whole £5 note for the fragment I sheepishly presented. It was not a happy start to my working life.

There was, however, another side to this unpopular boss whose grumpy personality made him seem a tyrant to his staff. One lunchtime Mr Vincent found me in the corner of the open office reading a book I had withdrawn from the local library. As I was by far the youngest in the office I had no one of my own age to chat with, and reading was the only way to pass the time – not that I, of all people, complained. No doubt Mr Vincent had observed me reading on other occasions, but this time he approached me with a book.

‘Carey. Have you read much of Charles Dickens?’ he asked.

I replied that I had not.

‘A pity,’ he said. ‘He is in my opinion one of the greatest writers in the English language. Here, borrow this book, and tell me what you think.’ He disappeared into his office, slamming the door behind him.

Within a few days I had read Nicholas Nickleby and returned it. The following day I was called into Mr Vincent’s large office and, standing on the other side of his desk, I was required to give him a critique of Nicholas Nickleby. His muttered grunts indicated approval, and another Dickens novel was passed across the desk. I must have read my way through most of Dickens’s oeuvre before I left to do my National Service at the age of eighteen. How I thank God for Mr Vincent for giving me such a wonderful apprenticeship in learning. It dawned on me later that it wasn’t only the reading of Dickens he encouraged in me, but the articulation of ideas. He made me use words more effectively, and made me listen to the rolling cadences of prose. ‘Read that again,’ I was often ordered. ‘Do you see the way he was combining nouns, adverbs and verbs to bring the reader into the story?’ He made me pay attention to the uses of language, as well as to its beauty.

But another discovery – an even more important discovery – happened during this period. I discovered there was a God.

My family was not religious – at least, not in the sense of feeling a need to go to church and worship. To this day I am not religious in that way. Worship is of course important, and people who claim to be Christian should belong to a congregation and attend as regularly as they can. But if worship is the outward badge of being a Christian, putting one’s belief into practice will always be its heart.

It was Bob, one of the twins, four years my junior, who first started going to Old Dagenham Parish Church. From the back of our three-bedroom council house at 198 Reede Road we could see the tower of the church in the old village of Dagenham. Bob loved the people he met there, and told me about them. So after work one day I decided to go along to the Youth Club that met on a Monday evening.

I made friends instantly. Every Monday the open Youth Club met, and on Tuesdays there was a meeting of ‘Christian Endeavour’. It was these that really interested me. They took the form of a service lasting one hour, led, in the main, by young people. Most of them were from lower-middle-class backgrounds, and they were zealous and bright. A few of them stood out, and would become special friends: Ronald Rushmer, Edna Millings, and the twins David and John Harris.

They were all a year or two older than myself, and I was impressed by the depth of their faith, the rigour of their thinking and the breadth of their lives. There was nothing ‘holy’ or ‘religious’ about them. They seemed to me to be whole people, and their interests were certainly mine. The fact is that, whether religious or not, I was deeply interested in philosophy, and particularly the meaning of life. I can’t even begin to date this interest, although I know that as soon as I was old enough to get a library ticket I started to read books by great thinkers. I vividly remember reading a book by Bertrand Russell for over an hour at Becontree library, and being asked to leave by an impatient member of staff who wanted to lock up.

The war had deeply unsettled my generation, and led many of us to ask fundamental questions about the meaning of freedom, democracy and peace. Working-class men returning from six years of conflict were determined to put behind them forever the nightmare of the thirties. Winston Churchill’s stock in the country was still high, but it was felt that even he represented a period that demeaned the vast majority of people in the land – as was demonstrated by his defeat in the general election of July 1945.

War affected me too: not in the sense of unsettling me psychologically, so much as making me aware that there were exciting questions concerning the meaning of life. Later I would find that Immanuel Kant’s classic formulation expressed my search succinctly: ‘What can I know? What must I do? What can I hope for?’ The three questions, focusing on epistemology, morals and the future of humankind, seemed to me to identify the truly crucial issues. For me as a teenager, however, the questions took a less sophisticated form: ‘Is there a God? If so, what is He like? Is He knowable?’

Old Dagenham Parish Church, with its open and evangelical style, suited me perfectly. A new vicar had arrived, the Reverend Edward Porter Conway Patterson – or ‘Pit-Pat’, as the young people instantly baptised him. Pit-Pat had recently returned from service in Kenya as a missionary. His preaching was direct, and always contained an appeal for people to turn to Christ. Many did, and the congregation grew. There could be no denying Pit-Pat’s great abilities and focus. His theology was Christ-centred and Bible-based. He was against anything that watered down the heart of what he believed to be Anglican theology, and particularly disapproved of Catholicism in any shape or form. If there was anything worse than Roman Catholicism, it was Anglo-Catholicism. He urged his congregation to abstain from drink and to avoid cinemas and theatres: ‘Come out from among them and be separate’ was one of his favourite Pauline texts.

Pit-Pat’s great strengths were his directness and simplicity; his weaknesses were the same. It did not take me very long to discover this, and in time I became concerned that he was projecting a joyless and stern gospel that fell short of the faith I was discovering for myself. Sadly, the negative influence of his teaching resulted in my feeling guilty for the next ten years whenever I saw a film or drank even a glass of beer or wine.

Worship puzzled me as well as impressed me. It was always based on the Book of Common Prayer, and a great deal of it seemed boring. It was the sermon we looked forward to, and following the service those young people who wanted to would go to the curate’s house for coffee and a discussion of the sermon. As time went on, however, I began to appreciate the framework of worship. Because of my growing love for the beauty of language, I came to find the Prayer Book evocative and wonderfully inspiring, and it took root in me. There are times even now when I wonder if the Church took a wrong turn in developing modern liturgies from the 1960s onward. We have certainly lost ‘common prayer’. In my youth, every parish church was bound together by the 1662 Prayer Book, even though it was expressed in many different ways. Sadly, today ‘uncommon prayer’ is closer to the truth, and many evangelical churches have departed from authorised forms altogether.

My intellectual development continued when the Harris twins began to interest me in music. Until then my musical education had been limited to what I heard on radio, which was largely the popular music of the time. I was, and continue to be, a fan of big bands and jazz. Ted Heath and his orchestra, Dizzy Gillespie, Stan Kenton and his band were among my favourites. One day John Harris said to me, ‘George, do you fancy coming round to our house on Saturday afternoon to listen to music?’ I readily accepted, expecting that we would be listening to jazz. Not a bit of it. I found myself listening entranced to classical music for three hours. This became a regular feature of my weekends, listening to great music, which like literature and philosophy took root in me – Elgar, Beethoven, Chopin, Bach, Mozart and other great composers. Ironically for a developing evangelical, Elgar’s Dream of Gerontius had a major impact on my emotional and theological development. It remains to this day one of the finest pieces of music I have ever heard. Through the influence of John and David Harris, music became an essential element of my growing faith. In time I was able to say with Siegfried Sassoon:

From you, Beethoven, Bach, Mozart,

The substance of my dreams took fire.

You built cathedrals in my heart,

And lit my pinnacled desire.

You were the ardour and the bright

Procession of my thoughts toward prayer.

You were the wrath of storm, the light

On distant citadels aflame.

As my thinking progressed, so did my journey into the Christian faith. I bought my first Bible, and read it avidly. At the same time I was reading Christian writers such as Leslie Weatherhead, the great Methodist teacher. Pit-Pat, recognising my thirst for reading, lent me books on prayer and spirituality, on faith and doubt, on doctrine and dogma. The focus of my interest was the person of Jesus Christ. His claims, and the claims that the Church made about Him, were so remarkable that I was forced to ask: Is it true that He is the hinge of history, that decisive omega point, by which all faith is assessed? The point came when I passed from a vague belief in God to a firm and joyful conviction that Jesus is the Son of God, Saviour of the World and, what seemed more important at the time – my saviour and Lord. There was no blinding Damascus experience, rather a quiet certainty that many of my questions had been answered, and my Christian life had begun.

I told Pit-Pat, and he was thrilled, although his response unnerved me: ‘I want you to read John 1.1, and memorise it to the end. Come back next week and recite it to me. Now, next Sunday, after the evening service we are going to have an open-air service in the banjo directly opposite your house. I want you to give your testimony.’

The first request was easy, but the thought of giving a testimony, a familiar practice in evangelical circles, terrified me. Because the ‘banjo’ (a familiar pattern on council estates, with houses arranged in the shape of a banjo around a small green) was opposite my house, all our neighbours would be able to see me standing on a soapbox, and would hear me speak. The implications were horrifying. My parents would be ashamed. But Pit-Pat would not hear of me backing down. ‘You have committed yourself to Christ. Now nail your colours to the mast!’

The following Sunday evening after the service, about thirty of us were there on the green, and a simple service began with a few hymns, a speaker and my ‘testimony’. I doubt if it lasted more than two minutes, but it was enough to satisfy Pit-Pat. In his opinion George Carey, at the age of nearly seventeen, had declared himself a believer.

Looking back fifty years, I have no doubt in describing it as a real conversion experience which changed the pathway of my life. It was forged from reading, from worship, fellowship and prayer. But it was only a beginning. Other great moments of discovery were to follow, and one can only call such youthful moments of conversion authentic in the light of what develops from them.

Great joy was to follow as other members of our family followed Bob and myself on this journey of faith. Our sisters Ruby and Val attended a church camp, and returned with a story of a commitment to Christ. And then our parents quite unexpectedly followed. I will never forget the moment Mum and Dad committed themselves to Christ. They had watched their children’s spiritual development with curiosity mixed with joy and, no doubt, alarm. That they did not know what was going on was evident, but they were pleased with the difference faith made to our lives.

Youth for Christ rallies were held regularly in Dagenham at that time, and we had invited Mum and Dad along to one particular meeting. The preacher invited all those who wanted to follow Jesus Christ to come to the front. To my amazement our parents walked hand-in-hand up the aisle. For both of them it was a ‘coming home’. They had been brought up as Christians, and had gone to church as youngsters. My father’s life, especially, had been irradiated with the spiritual through the influence of his blind grandfather. Now both of our wonderful parents were convinced Christians.

Dennis, eighteen months younger than me, was in the meantime going out with Jean, his future wife, and missed the spiritual revolution going on in the family. Although sad that this was not to be his story too, he was never made to feel excluded in any way. Indeed, I always felt very close to him, and knew that the Christian faith was also real to him, although expressed in a different way.

The impact of my father’s dramatic conversion revealed itself a few weeks later. Dad said early one Sunday morning, ‘I’m not going to church today, because I’ve got to put something right.’ He explained that when he was fourteen he had worked for a Christian man named Mr Zeal in Forest Gate, and had stolen some money. ‘But he must be dead by now!’ said Mother, amazed by Dad’s insistence that he had to at least try to make amends.

Later that day, Dad returned from his journey with a glad and triumphant smile on his face. He had gone to the nonconformist church where Mr Zeal worshipped and had been informed that Mr Zeal was still alive, but was not very well. Dad went round to his former employer’s house, reintroduced himself and confessed that he had taken a small amount of money. Mr Zeal looked at him with complete amazement and joy. ‘You know, Carey,’ he finally said, ‘I knew you had taken the money, and I have been praying for you ever since.’ What a shot in the arm for my father’s faith that was, and what a lot it taught us all about the power of prayer.

Even as a youngster I could tell what that commitment to Christ did for my mother and father. It changed them both, and gave them a great thirst to know more not only about the Christian faith, but about how to apply that knowledge to life around them. The limited education my father had received made it impossible for him to do anything other than lowly jobs, and soon after his conversion he became a porter at Rush Green Hospital in Romford, where he made a deep impact on the lives of many patients through his Christian goodness and kind words.

As for me, my learning too continued. My work at the London Electricity Board did not tax me, and I was eager to move on. The opportunity came when, not long before my eighteenth birthday, I received a letter informing me that I was due for my National Service call-up. I was delighted. It was time for me to move from my secure home, and I was ready to go.

3 Signals (#ulink_79981df8-6df0-5885-ab31-c5010e1c1071)

‘Why couldn’t Quirrell touch me?’

‘Your mother died to save you. If there is one thing Voldemort cannot understand it is love … love as powerful as your mother’s leaves its own mark. Not a visible sign … but to have been loved so deeply, even though the person who loved us is gone, will give us some protection forever.’

J.K. Rowling, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone

WITH A YOUTHFUL IMAGINATION fired by Mr Kennedy’s stories of the Royal Navy, and fed by my experience in the Sea Cadets, my preference was to do my National Service in the navy. Unfortunately, the Royal Navy did not accept conscripts at that time, so it had to be the Royal Air Force. As it turned out I was not to be disappointed in the slightest. For a young man eager to explore life and widen his horizons, the Air Force suited me down to the ground.

First came a week of ‘kitting out’ at RAF Cardington, where hundreds of dazed and subdued eighteen-year-olds gathered to be allocated to billets, receive severe haircuts and don the blue uniform of the youngest service. Pit-Pat’s final advice to me the previous day seemed particularly daunting: ‘George, you must disclose that you are a Christian right from the start. Don’t be ashamed of your faith. When lights go out, kneel by your bed and say your prayers.’ This had seemed easy enough to agree to when in church, but I confess that as I surveyed the crowded billet on my first evening, with the good-natured banter of high-spirited young men all around me, my resolve wavered. Nevertheless, taking a deep breath, I knelt and spent several minutes in prayer.

The reaction was interesting. First there was a quietening-down of voices as everyone realised I was praying and, unusually courteously, gave me space for prayer. The second reaction – clearly predicted by Pit-Pat – was that it marked me out as someone who took his faith seriously. The following day at least six young men in the billet took me aside and declared that they were practising Christians. By the end of the second day we were told of a SASRA (Soldiers and Sailors Scripture Readers’ Association) Bible-study meeting that evening. SASRA was particularly favoured by nonconformist and evangelical Christians, and throughout my National Service I found it a wonderful source of fellowship and support.

I never found that my practice of public praying, which I kept going for a great deal of my time in the Air Force, limited or negatively affected my relationships with other servicemen. To be sure, there were often jokes when I knelt down to pray. There were several times when things were thrown at me, and once my left boot was stolen while I was on my knees – just minutes before an inspection. Somehow I managed to keep to attention with one boot on and one off as the officer advanced through the billet.

Years later, in fact just a few weeks before I retired, I was touched to receive a letter from a Mr Michael Moran, who wrote to my secretary at Lambeth Palace:

Dear Sir,

Are you able to tell me whether George Carey spent the early years of his National Service at the basic training camp at RAF Cardington? When I was there at that time I was deeply impressed (and this has remained with me ever since) by the devotion and courage of an eighteen-year-old named George who knelt to pray at the side of his barrack-room bed. At no time in the following two years did I see anyone else show such evidence of his faith.

I was rather uncomfortable to receive such praise, because I did not kneel down to impress people by my courage, or to be the odd man out. In fact, I shrank from doing so. I did it simply because I felt Pit-Pat was absolutely right: if prayer is important, and if one is in a communal setting with no private place to pray, one ought not to be ashamed or embarrassed to be known as someone who loves God and worships Him. Later in life I would put the issue as a question to others: ‘Muslims aren’t ashamed to pray publicly, so why should Christians feel embarrassed? If it is a good way of praying when one is alone, why should we be ashamed of acknowledging a relationship with God when we are with others?’

The relative calm of the kitting-out week was followed by eight weeks’ hard square-bashing at West Kirby, near Liverpool. To this day, while I am left with many questions about the psychology behind the tyrannising and brutal attitude of the Platoon Leaders and Sergeants, there can be little dispute that it is a highly efficient way of moulding young men into effective members of a military unit. For eight weeks we were terrorised by screaming NCOs who told us in unambiguous terms that we were the lowest forms of life ever to appear on earth: ‘You are a turd of unspeakable putrefaction’, ‘a cretin with an IQ lower than a tadpole’, ‘You are the scum of the earth! What are you? Repeat it after me: the scum of the earth’, ‘You are hopeless, hopeless, hopeless.’

The verbal ingenuity of some descriptions was rehearsed in the billet long into the evening, as we sympathised with victims or rejoiced at the misfortune of a rival platoon. There were times when I too became the object of the Squad Corporal’s wrath. ‘Carey, you little bleeder!’ he screamed into my face, his saliva making my eyes water, ‘I am about to tear your ****ing left arm off and intend to beat your ****ing ’ead in with the bloody end, until your brains – if you have any – are scattered far and wide.’ Imagine my disappointment when I discovered later that this threat was far from original, and was in fact a tried and trusty favourite of that particular NCO.

I was able to gauge attitudes to the Church from the viewpoint of the ordinary conscript. The vast majority of my ‘mates’ had no contact with institutional religion. Although most of them, deep down, had faith, few of them had the ability to convert it into anything of relevance. They were not, on the whole, helped by the Chaplains, who held officer rank and talked down to the conscripted men. We all had to go to compulsory religious classes, and I can only say that from a Christian point of view these were something to be endured rather than enjoyed. The talks were usually moralistic, and the most embarrassing were about sex, a subject on which the Chaplains were definitely out of touch with the earthy culture of working-class people. I remember asking myself: ‘Why are they so shy about talking about the subject where they are expert? About the existence of God, about spirituality and prayer, about Jesus Christ and His way?’

Even more frustrating to me was the fact that I never saw a Chaplain visiting the men, either in the mess or in the billets. Far more effective was the ordinary ‘bloke’ from SASRA, who at least had the courage to meet the men where they were. Church parades were no different. The hymns were sung indifferently, and the sermons went over the heads of all. I was often embarrassed by the effete way services were conducted, and felt that overall they did more harm than good to the Church.

Although I was glad when the square-bashing was over, I have to admit that it taught me a lot about myself and how to cope when pushed to one’s limit. At the end of the eight weeks I was posted to RAF Compton Bassett in Wiltshire to train as a Wireless Operator. If I was not able to be a Wireless Officer in the Royal Navy, well, being a Wireless Operator in the Royal Air Force seemed an interesting challenge. And so it turned out to be. The training took twenty weeks, and included elementary electronics as well as having Morse code so drummed into us that by the end of it most of us were able to send and receive Morse at over twenty words a minute. As VHF was still in its infancy even in the RAF at that time Morse code was a reliable and efficient form of communication, though of course very slow.

At Compton Bassett we were able to participate in many activities, ranging from sport to hobbies of all kinds. Discipline continued to be very strict, but we were now finding that the ordered life enabled work and leisure to function smoothly. I played a lot of football, and enjoyed running as well. At weekends evening worship at Calne Parish Church was certainly far more authentic than the formal and compulsory church parades.

At the end of the training, everyone waited with impatience for their postings. I was astonished to be selected for the post of Wireless Operator on an air-sea rescue MTB (motor torpedo boat) operating out of Newquay in Devon. It seemed that at last my dreams would be fulfilled. If not the Royal Navy, at least I would be at sea with the RAF. But it was not to be. Two days before taking up my posting I was told to report to the CO’s office, where I was given completely different instructions – to go home on leave immediately, and to report to Stansted airport the following Sunday evening for an unknown destination.

I was among twenty or so extremely puzzled airmen on a York aircraft which left Stansted that September Sunday evening in 1955. To the question I put to the Sergeant on duty I received the friendly rejoinder, ‘You’ll know soon enough where you are when you land, laddie.’

Sure enough, I did. The following morning I found myself in Egypt, and the same day I started work as a Wireless Operator (WOP) at RAF Fayid – a huge RAF camp alongside part of the Suez Canal known as the ‘Bitter Lakes’. With a large group of other WOPs work began in earnest, handling signals from Britain and the many RAF bases in the Middle East. In my leisure time I enjoyed exploring beyond the base and discovered many things about Egypt, its culture and life. I settled down to church life on the base, and made many friends.

After three months at RAF Fayid I was sent to RAF Shaibah – a posting which was greeted by howls of sympathy by my colleagues. Shaibah was a tiny base about fifteen miles from Basra, at the top of the Persian Gulf. It is very hot most of the year, and the temperature rarely falls below 120 degrees in the shade in summer. With just 120 airmen to service the squadron of Sabre jets and cover the region I was told that it was a deadly appointment, and that I was to be pitied.

On the way to Shaibah a bizarre incident took place that was to make me chuckle often in later life. The journey began with a flight to Habbaniyah, a large RAF camp close to Baghdad, from where I was to make my way by train to Basra. I boarded the plane and was shown to my seat by the WOP, who told me, ‘Carey, your lunch is on your seat. Make yourself at home,’ before disappearing into the cockpit alongside the pilot. There were no other passengers, but I noticed that there was another lunchbag on the seat alongside mine. Surely this was for me too, I concluded. It was, I admit, naïve of me to suppose that the RAF would offer me two lunches and without hesitation I scoffed both of them. To my surprise the plane landed in the Transjordan, and as we taxied towards the concourse the terrible truth dawned on me – we were about to pick up another passenger, and I had eaten his lunch.

The passenger in question was an elderly clergyman, who was greeted with deference by the crew and shown to his seat alongside mine. We had a brief chat, and the plane took off. The moment came when he reached for his lunchbox, and I had to stammer out an apology for having eaten his lunch. He made light of it, and we relaxed into a pleasant conversation in which he showed great interest in my welfare and future. On landing at Habbaniyah I was impressed to see a red carpet laid out to welcome somebody – I knew it was not for me. The top brass were all there alongside the CO. The elderly clergyman paused to say goodbye to me, then turned to the steps to be greeted by the CO and whisked away.

‘Who was that?’ I asked the WOP.

‘Oh, that’s Archbishop McInnes, Archbishop of Jerusalem and the Middle East,’ came the reply.

Sadly, I never had an opportunity to apologise again to Archbishop George McInnes for having eaten his lunch that day; but at least I was later able to tell his son, Canon David McInnes, of the incident. David had followed his father into the Church, and completed a very distinguished ministry as Rector of St Aldate’s, Oxford. He was sure that his father would have been delighted and thoroughly amused that the culprit was a future Archbishop of Canterbury.

Despite the warnings of my colleagues at Fayid, Shaibah was to prove a wonderful posting for me. I was one of eight WOPs who had a special role as High Frequency Direction Finding Radio Operators (known as HF/DF Operators). So primitive and sensitive was this means of communication that it required the erection of special radio huts three miles from the camp, out in the desert. On each side of the hut stood four large aerials which received signals from transport planes, and which provided an accurate beam by which a plane could determine its position and find its way to us.

Operators were on duty in these isolated huts for eight hours at a time, and for many months we worked around the clock. The duty was often boring, very hot and lonely. There were however times when the importance of our work was driven home. On one occasion several Secret Service personnel called on me to help trace the position of a Russian radio network which was proving to be a nuisance to the RAF. Another time, a two-engine transport plane from Aden to Bahrain was in serious trouble, with one engine on fire and the other causing problems. To this day I recall the SOS ringing through my headphones, and the signal telling me that the plane needed help urgently as it was about to crash. All the training I had received was focused at that very moment on giving the crew directions on how to find their way to Shaibah, then alerting the main camp and the emergency services that a crippled plane was in need of help. As a member of the air-ground rescue team I would be required to switch instantly to new responsibilities if the plane crashed in the desert. Fortunately I was able to help nurse the plane to the base, where it made an emergency landing and all was well.

It was a lonely job most of the time, but I loved it. It gave me time to read and reflect. When things were quiet and no planes were within a two-hundred-mile radius it was safe to walk a short way from the hut and explore the desert. The idea that the desert was void of life, I discovered, is quite erroneous. There were always fragile, tiny yet beautiful flowers that one could find, and the place teemed with insects, snakes and scorpions. As for human contact, I often met passing Bedouin tribespeople: sometimes shy, giggling young girls hidden behind their flowing black robes, herding their black goats; sometimes their more confident brothers and fathers. They were always friendly, even though we could only communicate through signs and through my limited Arabic, which caused great merriment. In exchange for water, which I had in abundance, I would often receive figs, dates and other fruits. Their simple, uncomplicated lives seemed attractive and natural. It was always a joy to meet them, and for a few moments share a common humanity in a hostile terrain.

I do recall though one terrifying time when I wandered a little too far, and could not find my little signals hut in the expanse of desert. The realisation that I was totally lost, without water, and that my replacement would not arrive at the hut for six hours panicked me greatly. I tried to take my bearings from the puffs of smoke coming from the distant oilwells in Kuwait, but to no avail. I walked carefully north, hoping to find some clue that might orient me. Then, with relief, I heard the sound of singing, and into view came some of my Bedouin friends. They were shocked to see me so exhausted, and after a drink of water I was taken back to the hut. Perhaps only forty minutes had passed, but it made me aware of how fragile life is, and how the desert can never be taken lightly.

In our leisure time there was opportunity to explore the surrounding region, including the teeming city of Basra, a forty-minute car ride away. Every Sunday evening dozens of us would go to worship at St Peter’s Church, where there was a hospitable expatriate congregation. I confess that I can scarcely recall the services at all, and the only thing I remember is the vicar’s fascination for the card game Racing Demon, that was played every Sunday evening following choral evensong. But the worship was excellent, and almost without realising it I was nurtured and sustained by it.

Several of us went on a number of trips to the ancient Assyrian site of Ur of the Chaldees, home to Nebuchadnezzar. Time had reduced this great archaeological site to pathetic heaps of stone, but its grandeur and imposing scale was undiminished.

It was the living, vibrant Iraq that intrigued me, however, and I went out of my way to find out more about the life of its people. I made some enquiries at the Education Centre on the base, and enrolled in a class to learn Arabic. In this way I encountered Islam as a living faith. I was the only pupil in the class, and I took advantage of such personal tuition. My teacher was an intelligent middle-aged Iraqi named Iz’ik, who took great delight in teaching me the rudiments of a graceful language. In addition to the language, he introduced me to his faith. Through his eyes I gained a sympathy towards and an interest in Islam that has endured until the present time.

I was impressed by my teacher’s deep spirituality and devotion to God. It was not uncommon to see Muslim believers serving on the camp lay out their prayer mats wherever they were and turn to Mecca at the set times of the day. Many of my fellow airmen mocked them, but I could not. I sensed a brotherhood with them in their devotion and their openness about their spirituality. Although sharp differences exist between the two world religions, the way that Islam affects every aspect of life continues to impress me.

I was led also to appreciate the overlap between the Christian faith and Islam. I discovered its deep commitment to Jesus – a fact hardly known to most Christians – who is seen as a great prophet who will come as Messiah at the end of time. I began to appreciate the remarkable role of Mohammed in Islam, and the way in which he is a role model for male Muslims. Perhaps one of the most striking things that Iz’ik revealed to me was the fact that in Iraq Christians had been living alongside Muslims for centuries in complete harmony. In time I met a number of Assyrian Christians whose faith was deep and real.

Iz’ik and I often discussed the areas of faith and life where our religions diverged. Among these was the Trinity, and I hope that my youthful explanation led my teacher to understand that Christianity is monotheistic, and not polytheistic as many Muslims believe. I argued as strongly as I could for the relevance of Jesus Christ and the determining significance of Him for faith. As I saw it then – and still do – one can have a high regard for Jesus (as Muslims undoubtedly do), yet fail to see that unless He is central to the faith, that faith is inadequate without Him. Some thinkers have termed this the ‘scandal’ of Christianity, and the reason it can be seen as uncompromising and exclusive.