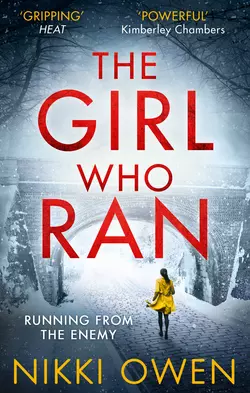

The Girl Who Ran

Nikki Owen

Running from the enemy…Dr Maria Martinez has finally escaped The Project facility that has been controlling her since birth. But in going against The Project’s rigid protocol, the powers at the very top of the organisation will go to any length to re-initiate her. Their aim? To bring her back to the tightly-regimented headquarters where their intense ‘training ‘of Maria can be completed.Fleeing to Switzerland in an attempt to outwit her enemy, Maria must never lose sight of potential danger, but soon finds there’s nowhere to run. And as she starts to question whether she can trust even those closest to her, returning to the one place she has fought so hard to leave might be her only option.An electrifying thriller, perfect for fans of Nicci French and Charles Cumming.

Praise for Nikki Owen (#uad4603e2-c80a-5b51-a311-1cbb3cf3f2d0)

‘Powerful and gripping - an adrenaline-filled thriller you won’t forget’

Sunday Times bestseller Kimberley Chambers

‘Taut and clever, with a fascinating, complex lead character in a terrifying situation.’

New York Times bestselling author Gilly MacMillan

‘A gripping and tense thriller’

Heat Magazine

‘A must have’

Sunday Express ‘S’ Magazine

‘high-octane … made me feel like I should be hyperventilating at times’

New Books Magazine

‘Always a step ahead of the reader’s expectations’

David Mark, bestselling author of The Dark Winter

‘Fast-paced thriller … building with pace to a dramatic finale.’

Gloucestershire Gazette

‘Seizes your attention from the very first page.’

Liz Robinson, LoveReading

‘A great conspiracy thriller and a mind-bending tale!’

Booktime

‘One of the UK’s most exciting new thriller writers’

Talk Radio Europe

‘Truly excellent!’

My Weekly

Born in Dublin, Ireland, NIKKI OWEN is an award-winning writer and columnist. Previously, Nikki worked in advertising as a copywriter, and was a teaching fellow at the University of Bristol, UK, before turning to writing full time. As part of her degree, she studied at the acclaimed University of Salamanca – the same city where her protagonist, Dr Maria Martinez, hails from.

Nikki’s novels are published in many languages around the world, and her debut novel was selected for TV Eire AM prestigious Book Club choice and Amazon’s ‘Rising Star debut selection’, the AudioFile Earphone Award and was a finalist for the USA Independent Publishers Award. Her second book was awarded the Book Noir Book of the Year Award.

Nikki now lives in the Cotswolds with her husband and two children.

To Dave, Abi and Hattie – my beautiful little family.

Contents

Cover (#uc908ae8d-2342-5a97-9478-9e63a19501fb)

Praise (#u9fc3de60-60d8-50d0-a5b5-afd237de64f2)

About the Author (#ud152f8f4-b27e-5277-8fbd-e60af918a8da)

Title Page (#u7d302fc5-b240-56f5-a7a3-777ba4630626)

Dedication (#u9993c854-d98d-5ac8-9511-582f552a1270)

Chapter 1 (#ulink_cf94691b-689f-5f8c-87aa-60be327c5849)

Chapter 2 (#ulink_c1691f9d-fc63-55ae-bd77-9a5b2d151875)

Chapter 3 (#ulink_fef30cc3-ce92-5d1e-83d2-1dea839f3cca)

Chapter 4 (#ulink_ddaf28b3-1086-5e79-a99e-bee6b11f42d4)

Chapter 5 (#ulink_ea0307d5-6440-521e-8ee6-4ea450c3ccfb)

Chapter 6 (#ulink_9a473a3c-4961-554a-84c7-af0aed1cd230)

Chapter 7 (#ulink_75dd579b-4255-552d-bbf2-c5d102e5d30a)

Chapter 8 (#ulink_c404c9ec-2478-5472-a90c-6c37706b0fc9)

Chapter 9 (#ulink_136ec787-3f7a-525f-94b6-b9d19f3f3ae8)

Chapter 10 (#ulink_848533dc-d3fc-5428-a87f-be2899aca183)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 36 (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 1 (#ulink_47ee97e8-479f-5979-a53e-85f19566fa51)

Deep cover Project facility.

Present day

The room is strange and yet familiar. I know where I am yet it is all new, and when I arrive at a white door marked Project Callidus – Clearance Grade Two, I know that this, finally, is the right place.

I know I am truly home.

I enter. I return the black security card into a zipped pocket and proceed. Everything is neat and ordered. The walls are white and gleaming, and the door three metres and eleven centimetres ahead of me is brown, neat and straight, a gloss to its surface reflecting the strip of muted, butter-yellow lights above me. There is barely any sound. My black boots brush in clipped, precise patterns on the cream polished tiles and, as they do, I count my steps, pausing at the now familiar notice that sits encased on the wall, a note repeated at careful, measured intervals throughout the clean, frosted walkways of each Project facility in the world.

Order and routine are everything. The Project is our only friend.

I read the words on the wall and a feeling passes over me: I am one of them; finally the rightful place for me in the world is here. For is that not what we are all searching for? Acceptance? I reach the far wall, stop and turn right. In every way now I know where I am going, but there are moments when I wonder who I truly am, when I think it’s hard to find a place in the world when you don’t know who you are supposed to be.

Striding seven more steps in the glow of the bulbs above, I reach a small grey monitor. Ahead, another subject number talks in hushed tones to a fellow colleague, and while we follow protocol and acknowledge the other’s numerical existence, each one of us is careful to make no eye contact at all.

There is a quick crackle from the monitor. ‘State your name and subject number.’

I clear my throat. ‘Dr Maria Martinez. Subject number 375.’

One second passes, two, until a mild buzzer sounds and, as per measured routine, I lean in to allow a soft pink light to scan my retina. The door ahead of me clicks, followed by a familiar whoosh of air and, striding seven more steps, I knock on another door. This one is thick, metal and heavy with silver casing and deep, solid locks with a sensory entrance system designed to withstand the harshest attack.

‘Enter,’ announces a familiar voice from inside.

In my nightmares and memories, the sound of him, of his accent, used to bother me. It would pull me into a downwards spin of fear, but now my mind has learned to find the Scottish lilt comforting, helpful to me and a welcome element in my daily routine. Placing my hand on the steel of the door and, the internal scanner tracing every groove of the unique lines on my skin, I walk in. There is a banging noise from somewhere, a mild moan, but my brain ignores it and my eyes remain facing forwards.

‘Subject 375,’ he says, inhaling through flared nostrils on a thin, pointed nose, ‘you are three seconds late.’

His skeletal fingers drum on a white file that sits on a metal desk, eyes as dark as oil, two round patches of bitumen pressed into deep, bottomless sockets. As he breathes, his head tilts and his tissue paper skin shines translucent, stretched across bones so thin that the blue roots of his veins glisten, criss crossing his face and neck and arms, down to where two spindled wrists hang on hooks from his triangular joints. He wears a white coat and a brown lambswool jumper, his shirt cornflower blue, and on his legs that bend like twigs about to snap hang trousers scratched from polyester and cotton that stop at his ankles where the bones jut out.

I speak. When I do, I am careful to ensure my voice does not shake or flip or fold. ‘Forgive me, Dr Carr.’

He regards me. He taps a single finger on the metal table and looks to the right where a large, rectangular mirrored window rests. I catch my reflection. Hair back to black, cropped neat to the scalp and neck, my green contacts are now gone to reveal birth-brown eyes that match a tan skin which softens to honey in the glow of the light hitting the curve of my elbow. Since I was brought here and recommenced training, much of my body has changed. Where before I was lean, now I am strong, muscular, the definition of my biceps and triceps outlined under the soft cotton white t-shirt and the smooth black brush of my Project-issue combats. My stomach is taut and when, on instruction of Dr Carr, my legs stride to the chair and sit, my quads tighten automatically, flexed, honed.

He installs a smile on his face, no eye creases, and clicks his pen. ‘Time for our daily chat.’

A ripple of nerves passes through my spine down to the soles of my feet. I smell in the air, for the first time since entering, his familiar scent, a scent I have known for almost three decades since the Project took me and began their conditioning programme. Hot garlic, stale tobacco – the odour trail of his presence left long ago in my road map of memories. My immediate instinct is to run, to bang on the door with curled-up fists and yell for them to let me out, yet instead I find a way of breathing through it, of practising mental yoga in my head and moving my mind in a gentle rhythmic flow of reassurance and calm. He has taught me to react this way. When pushed to its limits, the mind can achieve so much, he says. And so I inhale his aroma and ignore the bubble of worry that threatens to burst, and gratefully channel the emerging inner-strength that the Project has helped me cultivate.

Dr Carr crosses one leg over the other and opens a folder. From the mirrored window, the moan from earlier sounds again, low, but audible.

‘Have you received your Typhernol injection today at the allotted time?’

‘Yes.’

‘Any reactions, symptoms?’

‘I had a headache at 06:01 hours, followed by a short nosebleed that lasted forty-seven seconds.’

He makes a note. ‘Now, Maria, as we always do in order to reinforce why we are all here, can you state for me your name, subject number, age, status and reason for being at this Project Callidus facility.’

I clock the four corners of the white room, note the laptop on the table and, next to it, one picture frame with a photograph of two people unknown to me, and yet somehow there is a flicker of familiarity at the sight of their faces, a grain of remembrance I cannot place. My eye switches to a second, smaller, clear window that throws a view onto a bank of subject numbers working silently on rows of computers beyond, each with their sight locked in front of them on their tasks. Satisfied all is in order, I begin.

‘I am Dr Maria Martinez. Subject number: 375. I am thirty-three years old—’

‘Soon to be thirty-four.’ He smiles. ‘Soon.’

I nod at this fact and continue as per routine. ‘I am a member of Project Callidus, conditioned with my Asperger’s to assist in the Project’s covert cyber and field operative missions. We protect the UK and global nations against terrorist attacks of all kinds, and, due to the NSA prism programme investigation, we are black sited and are no longer affiliated to MI5.’

He sucks in air. ‘Good. Now – my name, the special one you reserve just for me, what is it, Maria?’

‘Black Eyes,’ I say, delivering the response as per requirement. This is his favourite part of our talks, or so he says. ‘Your name, Dr Carr, the one I have always given you since you trained me from a young child, is Black Eyes.’

He nods and smiles, and I notice tiny crinkles fanning out by his eyes. ‘Thank you.’ He leans back a little in his chair, his stomach concave, and his jumper seems to sink into him.

‘Now, since you arrived here, how do you think you are adjusting?’

‘I have fully memorised the map of the facility and know all routines down to the last second.’

‘Do you recall yet the immediate events leading up to your arrival at this facility for your Project re-initiation?’

I hesitate. Images sometimes come at night, blurred events, faces, but nothing yet definable or real. ‘No.’

‘And so when you see this’— he slides the laptop to me and clicks to a page — ‘what do you think about?’

I read it fast, photographing the data to the memory banks within ten seconds. Facts. The file contains spool upon spool of facts about me. Dates, times, images all collected by my handlers over the years, undercover Project handlers at school, university, work who watched me grow up and who took me, with the help of my adoptive mother, Ines, to train me on missions, then drug me with Versed to make me forget what I had done. There are facts about my time in prison for a murder I did not commit, a murder I was set up for by the Project to get me out of the way while the NSA scandal blew up. Details on my adoptive family, how Ines killed my real father, Balthus, and shot my adoptive brother, Ramon, after pretending it was he who had given me to the Project. Facts about how I killed Ines at her Madrid apartment to protect my then friends, Patricia and Chris, the whole scene covered up by the Project, dressed up as a gangland drug killing. There are pictures of each person I have known, intelligence on them, and I resist the urge to reach out and touch the image of their nearly forgotten faces; at this black site facility we are taught that the Project is our only friend.

I look to Black Eyes. ‘When I look at this data I think about the killings.’

‘Done by you or by others?’

‘Both.’

‘You have killed several people, Maria – how does that make you feel?’

I hesitate. Feelings, for me, are the hardest questions to answer.

‘You see, Maria,’ Black Eyes says now, ‘you are vulnerable, or at least, you have been vulnerable to outside influences, and it affects you from time to time, as I suspect it’s doing now. But that is why I am here. You must learn to lock it away, shut such trivialities from your mind, forget your past, forge your future. Ines gave you to us from Balthus and Isabella, your real mother, so you could be someone better.’

‘Ines gave me to you so she could have cancer drugs from the Project in return,’ I say, struggling to keep a worm of emotion from rising in me. ‘Ines lied to all of us and was working with the Project all along. Ines… Ines helped to kill my Papa.’

‘He is not your Papa,’ he suddenly snaps. ‘He is Alarico. He was your adoptive father.’

My eyes flicker to Papa’s image on the computer: warm smiles, creased eyes. ‘I… I miss him.’

I drop my head, feeling an acute sense of failure. I have tried to forget my family, my friends; I have come a long way and it has been hard, too hard sometimes. I glance around the room, at the walls and the window, deeply sad yet resigned, my feet weary and heavy, and the thought arrives that this here now, with Black Eyes, with the Project, is the only option I have left. The only option now. I am on my own. Everyone has deserted me. Gone or dead, I don’t know – it always varies, but one thing throughout it all has been consistent: the Project. It’s all I have left. I have tried, in the past, to fight them, have actively railed against them, but for what? What good has it done? What good does it do to fight for what you believe in when all you are is a wounded soldier in a losing battle? Is it not better to lay down your arms and surrender? To try and at least see down the barrel from their point of view? Here, with the Project now, with Black Eyes every day, I can see now that it offers me something of what I need: a routine. And maybe this is where I was meant to be all along, a place where a daily routine is standard, surrounded by people like me, working, perhaps, for a greater good. I can learn, maybe. I can attempt to understand what it is they are really trying to do and possibly then acceptance of it all will be easier. You can’t control everything and sometimes there comes a moment when you must accept that this is the way your days are meant to be. This is, all along, who you were meant to be.

Black Eyes lets out a long sigh and shuts the laptop. He glances to the picture frame on the desk. ‘The past is hard to deal with sometimes.’ He lingers on the image for a second then looks back to me. ‘And, Maria, a lot has happened to you. But, what you have to remember is that it’s the future that truly shapes us, if only we let it.’

I listen to him and as I do, the Project’s phrase, the one bolted to the corridor walls, enters my head, clear and true. ‘Order and routine are everything,’ I find myself chanting.

Then we say, together: ‘The Project is our only friend.’

A smile spreads on his face and reaches his eyes then, clearing his throat, he flicks a page. ‘Now’— he taps a file with photographs— ‘to pressing matters. You know these two people, correct?’

He presents me with two images. I take a sharp breath.

‘This,’ he says, pointing to one, ‘is Patricia O’Hanlon – your cell mate at Goldmouth prison when you were incarcerated for the murder of the Catholic priest before your acquittal.’

‘Yes.’

‘And you were good friends, close, yes? Your first real friend, would you say?’

I swallow, nervous. Why is he asking me this? ‘Yes.’

His finger traces Patricia’s swan neck, her shaven head and blue saucer eyes, and as he does, I feel uncomfortable, concerned, but I don’t know why. ‘And this,’ he says now, ‘is Chris Johnson. We have a lot of data on him. Convicted American hackers tend to pique our interest. I believe it was Balthus that originally put you two in touch?’

‘Yes,’ I say, my throat oddly dry. ‘I met Chris at his villa in Montserrat, near Barcelona. I went there after MI5 found me at Salamanca villa. Chris was in prison for hacking a USA government database. Balthus was Chris’s prison governor before he was in charge of Goldmouth.’

Black Eyes moves the file nearer to me and my vision catches Chris’s familiar deep brown eyes, his uncut hair flopping to sharp cheeks and stubbled chin, and somewhere inside me, I feel an indefinable pull towards him, and towards the faces on the pages, an urge to scoop them to my chest and hold them tight.

‘Maria?’

I whip my head up in fright at his sudden voice. ‘Yes?’

‘The Project is your only friend.’

His eyes reduce to small slits, one second passing in the silence, two. He looks from the faces in the file to me, then back again in a seesaw pendulum of time. I shiver, not knowing what to do, worried, scared even at how strongly I felt just now when I saw the faces of my friends, yet shocked at how much I want to please Black Eyes, please the Project, do whatever I can for them, find a place where I belong, accept that this is where I am to live my life.

After ten seconds pass without a word, Black Eyes scrapes back his chair and, striding to the glass mirror on the far side, he turns and faces me.

‘Maria, I have something to show you.’

He steps back and presses a buzzer. I watch, a nervous swell inside me licking the shores of my brain as the mirror of the window begins to move and a grey blind behind starts to rise. It reaches the top, clicking to a halt but still I cannot see fully what is beyond, when another snap sounds and this time a light switches on from the other side. A brightness floods the room and I have to blink over and over as it assaults my eyes, my hand shielding them. I have to resist the strong compulsion to duck and curl as, slowly, I finally see what was causing the moaning earlier.

‘Doc! Doc!’ the familiar Irish lilt of a voice shouts out.

I manage to stand and step forward, as what emerges in front of me, limb by limb, bone by bone, is a beaten, bruised and tied-up body.

When I find my voice, only one word comes out. ‘Patricia.’

Chapter 2 (#ulink_85bb5ff6-d86a-5ce1-999a-30342af6a4fe)

Madrid Barajas Airport, Spain.

Time remaining to Project re-initiation: 32 hours

Even the earbuds I wear can’t cancel out the chaos and noise. People march back and forth, left and right, criss crossing the glaring bright gloss of the polished airport walkways. Babies scream and toddlers yell, coffee cups clink and trolley wheels screech, tannoy systems above my head bark the next flight departure as, in the near distance, wine glasses tinkle at a champagne bar, and a group of people laugh at a joke I will never understand.

I stand and blink and watch it all as the airport scene crashes into my senses, body and mind temporarily paralysed by everything. The noise, the smells. Tinny music from open shops. Coffee, beer, oil, sickly sugar, stale cigarette smoke, burger fat, perfume, leather, sweat, the faint soak of breeze block urine. The slurp of a straw. The bite of a sandwich. Every single scent, I smell. Every tiny pinprick of noise, I hear. It all smashes into my brain, colliding into my white and grey matter until I don’t know which way to look.

‘Doc?’

I slip out an earbud and look to my friend.

‘They’re not going to spot us,’ Patricia says, her voice low, calm. ‘We’ve got through security and I know airports are a nightmare for you, but look at us.’ She points to herself. ‘We’re in business suits and wigs. Jesus’— she smiles,— ‘I’ve never looked so smart. So it’ll be alright. Okay?’

I nod and tap my finger.

Another smile. ‘Good. You’re doing great. I’m right with you.’

She looks down at herself now and I watch her angled arms, her swan neck and her shaven head disguised by a long, mouse-brown wig that settles on suited shoulders. A cream, silk blouse slipped under a black jacket sits against smart tailored trousers and neat, flat ballet pumps on the end of flamingo stalks for legs. My friend. My first true friend.

‘It is too loud here,’ I say.

She takes my palm and presses her five fingertips into mine as she has always done. ‘I know, Doc. I know it’s too much information flying into your head from the airport, but I’m here.’ A group of passengers shuffle nearby and Patricia forms a little bubble of space around us so no one brushes against me. I catch her familiar scent of talcum powder, fresh linen, bubble baths. It makes me breathe a little slower.

Chris wanders over. He fiddles with his suit and his newly dyed bottle-blonde hair, and shakes his bright red Converses. ‘The security guards are hanging around a bit back there. We need to get moving towards boarding.’

Patricia eyes his feet. ‘You couldn’t have worn a pair of smart shoes, could you? We’re supposed to be pretending to be professional business people.’

He fidgets, pulling at his yellow tie, at the sleeves of his smart navy suit, shoulders twitching. ‘I feel like an idiot.’

‘You look like one.’

Chris glares at Patricia. He scratches where a white shirt clings to a flat surfer stomach and pulls at his trouser band muttering, ‘It’s too fucking tight.’

I observe my friends without any understanding of what their exchange means, the glances between them, the words. Funny or serious? Heartfelt or fickle? Ahead, a large bang slices the air as a café tray clatters to the floor, cups and plates and cutlery smashing into cold cream tiles, the sound of it hammering my head. I wince. It’s exhausting. I need stability, something factually familiar for my mind to cling onto, a lifeboat of facts.

I turn to Chris. ‘The term “idiot” means a person of low intelligence. You hacked into a CIA website, that takes intelligence to achieve. Therefore, the term idiot in describing you is wrong. On this occasion.’

Chris pulls his tongue out at Patricia. ‘See.’ Then he turns to me. ‘Thanks, Google.’

‘I have informed you before – that is not my name.’

He smiles, big and wide. ‘I know.’ Then he starts humming a song I have come to recognise from a singer he seems to greatly admire called Taylor Swift.

‘That is the melody entitled…’ I listen… “Shake it Off.”

He grins. ‘In one.’

Patricia rolls her eyes. ‘We have to go. Doc?’

‘Yes?’

‘Stay by me.’

We find a semi-quiet patch in a coffee shop and sit. Immediately anxiety hits. The slurp of peoples’ lips and tongues as they sip their drinks. The clink of cups. The steam from the milk machine and the mechanical grind of coffee beans. Teeth biting down into crunchy lettuce. Someone’s lace undone, the thread hanging loose, dragging along the floor. It all collides inside me. I try to focus, count, look to Patricia who mouths to me, ‘How can I help?’ except I don’t know the answer, only know that here and now I need to keep any potential meltdown under control so no attention is drawn to me or to us. Three hours ago we were in Ines’s apartment and I killed her with an iron nail to the neck, and watched Ramon and Balthus die. The last thing we need is a scene.

‘Doc, deep breaths.’

I nod, watching Chris closely as he walks to the counter, orders our drinks, but immediately, this tips me into a panic.

‘I want a black coffee,’ I say. ‘What is he ordering for me? It can only be black.’

‘It’s okay,’ Patricia says. ‘He asked me and I said black coffee. I told him for you.’ She smiles. Soft cheeks, lines opening wide at her eyes. ‘Okay?’

I nod, but inside I am panicking.

Chris is talking to the barista now, easy, light, making random conversation about the bustle of the airport. To give myself something to focus on, I examine his movements, his facial expressions. How easy it seems to come to him, how simple such dialogue appears for him. I try pressing some of it into my memory, the way in which he acts, remember it so I can perhaps use it, mimic it, cover me up. It’s hard to find a place in the world when you don’t know who you’re expected to be.

Done with that yet still anxious, I turn my focus to checking and rechecking the time of our flight to Zurich where Chris has secured us a safe house through his hacking contacts until we can get further away and out of sight. Finally, Chris returns and it’s only then I can be assured that the right drink has been bought. I sip slowly. The liquid is hot, scalding my palate and tongue, but I like it, as if it polishes the tips of my mind so they are ready to be used. Now and then the multiple sights, sounds, smells of the airport hit me, make my body go rigid, but breathing and counting help, and so I do that, run through numbers in my mind, murmur the digits with the tips of my fingers pressed one after the other into my thumb, all the while glancing to my friends, grateful that they are here.

‘Okay, so, I checked my email,’ Chris says, emptying two full sachets of sugar into a latte, ‘and my buddy in Zurich is all set for us to rock up there. All secure. Also, from what I can tell, it looks as if the Alexander woman has read the message we sent her.’

Patricia looks up. ‘What? The Home Secretary?’

‘Yep, Balthus’s wife, Harriet Alexander herself.’ He draws out a computer tablet and taps the screen. ‘About twenty-seven minutes ago. No, wait…twenty-eight minutes ago she read the whole file that reveals the Project Callidus bombshell, from way back in 1973 up to right now.’ He starts listing things off with his fingers. ‘The thousands of Basque blood-type people they’ve been testing on, the cancer drugs for Ines, the Project taking Maria and drugging her, Maria being Balthus’s kid, all of it, all of the stuff we hacked into in Hamburg.’ He grins at us and I wonder if his face has ever, in his life, been fixed into a frown; I resist the temptation to stick my finger into the dimple on his chin.

‘Well,’ Patricia says, ‘hopefully that’ll be it. That’ll be enough for the government to kick-start an investigation into the whole Project bollocks and it’ll finally all be over. No more running.’

‘Can your software connect to her server system?’ I ask.

‘Ah, you’re thinking of hacking into her emails, tracking who she contacts about the subject of our little message. Yep, thought of that. There’s something blocking me at the moment, don’t know what it is yet, but I’m on it.’

We finish our coffee. Chris taps on his computer the whole time and, ten minutes to go until our flight is boarding, he excuses himself to attend the lavatory. I use the spare time to carry out a reassuring check of the contents of my rucksack. One by one, I place them on the table in a neat line: three pay-as-you-go cell phones, two fake passports, money in several denominations, one wash bag, two packets of energy tablets and the other essential items I require to be on the run and hide, all itemised on a list in my head. But it is the last three things that I unpack, that now amid the din and the cappuccino milk steam and the idle chatter around tea-stained tables, that give me the most sense of calm and reassurance: my notebook and two old photographs.

I rest my hand on the worn notebook cover, flick a finger over the dog-eared pages, pages that have housed my thoughts and calculations and mathematical probabilities for years, each spare section crammed with drawings and codes scribbled feverishly after awaking from dreams and nightmares that would jolt some distant, drug induced memory.

Patricia leans in, looks at a page filled with algorithms and coding. ‘I may as well be seeing spots as to understand what on earth all that means.’ She inhales. ‘It’s been hard for you, hasn’t it, Doc? Everything that’s happened.’

I touch the page with my fingertips, let them skim the curve of the equations before me, the lines, the sketches of pencilled memories forgotten and only sometimes remembered. ‘Ines killed Balthus,’ I say, sticking to the facts, unable to express the sorrow I truly feel inside.

‘Yes, Doc, she did.’ Her voice is a soft pillow, a floating feather.

I blink, turn my attention to the two photographs from my bag.

‘Is that your dad with you when you were young? He has the same dark hair and eyes as your brother.’

‘Yes. Except they were never my biological father or brother.’

‘No,’ Patricia says. ‘No, I know. Balthus was your biological father, and that’s hard – you watched him die when you’d only just found out who he really was.’

I swallow. My eyes are a little blurred. ‘Yes.’

Patricia touches the second photograph, this one more sepia-toned and worn. ‘You were a cute baby.’

I take the second image between my fingers and stare. In it stands a woman, my biological mother, long hair falling in wisps around her face, two grainy, willowed hands on the ends of ribbon-thin arms cradling me – her new swaddled baby. I map the skirt that skims the ground where ten toes on bare feet rest on a bed of gravel surrounding a sprawling, stone hospital-come-nunnery with a crucifix on the door. I blink at the photograph and battle with a feeling inside me, strange and unwelcome. Anger and sadness, a tumbleweed of sorrow that, try as I might, will not go, but instead rolls along the barren land of my heart and mind, leaving behind trails in the sand that vanish with one whip of the wind. Isabella Bidarte – my real mother. I try the phrase out in my head, wear it like a new pair of shoes, walk it up and down the corridors of my mind, but it feels odd, stiff, as if using it for too long would create a blister filled with pus that would burst and seep and hurt.

I turn the photograph in my hands. On the back is scribbled an address and the geolocation coordinates of a hospital – Weisshorn Psychiatric Hospital, the place Isabella was last kept in Geneva, and next to it the date of her death, all etched out by my Papa and hidden from Ines before he died.

Patricia stares at it. ‘He knew she was kept there, didn’t he, your dad? He’d found out about what Ines was doing – getting the cancer drugs to keep her alive in exchange for you.’

Too sad to speak, I trace the address and date with my fingertips as, to the right of the café, a television repeats a news feed detailing the killings at Mama’s apartment.

‘A triple homicide was reported in Madrid, in what is being cited as a cartel crime. Spanish lawyer and member of parliament Ines Villanueva; her lawyer son, Ramon Martinez; and a British prison chief, Balthus Ochoa, have all been implicated in what sources are saying is a decade-long fraud ring stretching into millions of dollars and which includes trafficking in illegal medical drugs. The bodies of the three were found at Villanueva’s central Madrid house this afternoon. Villanueva, who was a likely pick to become the next leader of the right wing, and prime minister …’

Tilting her head so I can see her eye-creased smile, Patricia nods to the television. ‘Same story they’re telling like before, same bullshit.’

‘It is all lies. The deaths did not happen in that way.’

She sighs as the television screen flashes across the faces of Ines, Balthus and Ramon.

We finish our coffees. I carry out a final check of my belongings, secure the photographs in an inside pocket near my notebook and, acknowledging the presence of my passport one more time, in my head I begin to carry out a run-through of the airport journey when Chris runs up to the table, breathless.

‘Jesus,’ Patricia says, ‘what’s with you?’

He swallows, pointing behind him. ‘People…’ He gulps air, slaps two palms to the table and hauls in some oxygen. ‘C-coming…’

‘What d’you mean?’ Patricia says, frowning. ‘You’re not making any sense and we’ve got to—’

‘Shush!’

Patricia opens her mouth on the verge of speaking when Chris raises a hand and finally spits out the words he wants to say.

‘The Project – they’ve found us!’

Chapter 3 (#ulink_688d6d56-538e-597c-99c5-2dfa87832254)

Madrid Barajas Airport, Spain.

Time remaining to Project re-initiation: 31 hours and 30 minutes

I turn, stand, focus. ‘Tell me.’

He swallows. ‘So, I was just walking back and looking in the duty-free bit, and they have the mirrors and stuff there and I’m sure there were two guys watching me.’

‘This is ridiculous,’ Patricia says.

‘What? No. I was followed.’ He looks straight to me. ‘I’m telling you – they were different, these guys.’

‘How?’

‘Just, well, I guess they were, like, rigid, you know. Kind of robotic and—’

‘Christ,’ Patricia says, ‘this is the last thing we need, you freaking out on us like this.’

‘I’m not freaking out.’

‘You are, and you’re going to upset—’

‘No!’ His voice is raised. I flinch. The people at the next table stop eating mid-sandwich bite and narrow their eyes.

Chris lowers his head. ‘No. Please,’ he whispers, ‘you have to listen to me. I know they have to be different because I recognise them, from when I was locked up for hacking, okay. One of the two guys who investigated me via the UK, well they were MI5. The other one, I’m not sure…’

‘You have to be sure,’ I say. ‘Now.’ My eyes scan ahead, quick fire.

‘I’m sorry. I recognise both of them, just can’t place the second one.’

‘One of them is definitely MI5?’

‘Yes.’

The cogs in my head, as if tripped by a switch, begin to turn at such a rate, for a second I feel dizzy.

‘Shit,’ Patricia says. ‘Doc, MI5 wanted you dead. If they’re here, this is not good.’

‘Oh fuck.’ Chris rubs his head. ‘Oh fuck, oh fuck.’

As my friends swear repeatedly, I scan the crowds.

‘Maria,’ Chris says now, ‘I’m sorry. I sent that email. MI5 must have tracked it.’

‘Why would you be sorry?’ I ask. ‘This is not your fault.’

‘It is,’ Patricia snaps.

I look between the two of them. ‘We cannot determine with any mathematical certainty why these men are here. We can only assume.’ I pause, my mind firing at such a rate now, the probabilities and conclusions whip out. ‘We can only assume a level of danger which requires some amount of action on our part.’

Patricia blows out a breath. ‘Shit a brick.’

Chris nods. ‘Too right.’

I scan the busy foyer, the noise so loud, my body wincing at the near physical hurt it causes me. Heads, hats, citrus perfume, detergent, the smell of ice cream and pancakes, a series of buckles and trailing laces.

‘I can see them,’ Chris says.

‘Where?’

He gestures to an area by a burger bar thirty metres away. ‘Right… there.’

I follow his line and spot two men, black jackets, casual clothing, no suitcases, no definable baggage, just coffee bean eyes and steady strides.

‘Doc,’ Patricia says, ‘is it them? Could MI5 be back working with the Project now, you know, running it or something?’

‘I do not know,’ I say, sight missile-locked on the two figures. Flickering fluorescent lights, the clatter of suitcase wheels, the hum of a fan somewhere in a nearby store, the oppressive stench of chip fat. It all collides in my head, making it harder to think straight, but even between the chaos, a cold calm descends and a phrase, one drummed into me by the Project, despite my resistance, enters my head as easy as walking through an open door. Prepare, wait, engage.

I turn to Chris. ‘You are certain it is them?’

He gulps. ‘Yes.’

‘Then we have to go.’

He rubs his face. ‘Oh man, oh man, oh man.’

Bags secured, Patricia moves backwards, her feet stumbling a little, Chris following as the three of us slip behind a large silver pillar that houses neat billboards for expensive Parisian perfumes.

‘Doc, what do we do now?’

I glance to the area ahead and watch the two men. They walk five steps then stop and, as they do, my brain carries out a full and rapid assessment of the immediate threat. Each man is approximately one hundred and sixty-six centimetres tall, the right man blonde, the left brown, no distinguishable facial features, no definable scars, and by quick track of their frames, each appears to be built to endure long distance runs over twenty kilometres, yet still bulked enough to carry the weight of a full army training kit on their backs.

Patricia bites her lip. ‘They’re not real travellers, are they? Oh, God.’ There is a shake to her words. She chews on a nail. ‘You think they’ve seen us?’

Chris risks a glance. ‘Maybe… Fuck.’ He slips out his phone, sets up a fast proxy, starts tapping on a screen I cannot see. ‘Let me… Hang on.’

‘What are you doing?’ I ask, but he shakes his head, taps his phone and does not reply.

I scan the shops to calculate the best route forwards. By the entrance of a chain of toilets, a toddler is squirming in a ball on the floor screaming while his mother flaps around him, coils of hair springing up, shored by sweat, the father nearby, scratching his head, tutting into a smartphone that’s stitched into his hand. The noise of it all ricochets around my brain.

‘Doc,’ Patricia whispers, ‘should we get out of the airport?’

‘No.’ I take a breath, try to count the noise away. ‘We must board our flight and travel to Zurich as planned.’

‘You think that’s wise? Won’t they know where we are going?’

‘Negative.’ I swallow. Someone make the toddler be quiet. ‘We look different. Our email tracks have a high probability of being invisible.’

Chris, head up from his phone, points. ‘They’re moving.’

Patricia bites down harder on her fingernail. ‘Doc, I’m bloody shitting it.’

‘If you soil yourself, you could impede our escape.’

She ceases eating her hands.

The billboard with the perfume advert on the pillar is a rolling one. I observe it. Every six seconds, there is a change of posters, promoting gilded watches, branded clothing, vintage bottled cognac, champagne and truffles, and each time a new poster flashes, the entire board moves from side to side creating one small yet significant space behind it, a scooped out hole. A blind spot.

I turn to my friends. ‘There is a place to hide, there.’ I point. ‘It will provide us cover to plan the next move. When I say go, we all go. Do you understand?’

They nod.

‘Does that mean you understand?’

Two frantic nods. ‘Yes.’

‘Good. I will count to three. On three, we will run to the billboard.’

‘We won’t be seen?’ Chris checks.

‘No.’

‘Okay.’ His eyes flick ahead then back to me, a breath billowing from his chest. ‘Go for it.’

‘Okay. On my count: One…’

Patricia slaps a hair from her face, mutters, for some reason, what I believe is a slang word related to a man’s genital area. The billboard begins to revolve to the side.

‘Two…’

Chris taps his foot. He shields his phone screen with his hand as his eyes dart left and right in the glare and bustle of the concourse beyond.

‘Three. Go!’

We run. Lights, sounds, sharp slaps of heat and noise. They all fly through my ears as we weave in and out of the crowds. The men do not immediately follow us and yet still there is something about the way they move, about the assurance of their steps.

We reach the billboard. ‘Which way?’ Patricia whispers.

To our right is a concourse of cafés and shops, people spilling out of them in various states of speed and urgency. To our left is the open floor, shining, twinkling in a yellow brick road that leads off to the departure gate announcing cities and flight numbers. My brain photographs it all. Istanbul, Melbourne, Washington, Paris, locations that span the world across data lines that lie hidden underground.

‘They know we are here,’ Chris says. ‘I’m certain now.’

I whip round. ‘What?’

He turns his phone to me and my heart starts to race at an alarming speed.

‘I hacked into the Madrid police database,’ he says. ‘You know, to be on the safe side, get some firm intel. I found this.’

‘Oh, holy fuck,’ Patricia blurts. ‘It says wanted. It’s us!’

There are pictures of all three of us. My mouth runs dry so fast that I have to lean against Chris to steady myself.

‘Hey,’ he says, ‘you okay?’

‘They have us in different wigs,’ Patricia says. ‘Shit – they’ll know what we look like!’

‘I have put you in danger.’

‘Huh? What? Oh Doc, no. None of this is your fault. Doc, it’s okay.’

‘Er, no,’ Chris cuts in. ‘It’s not okay.’

We both look to him, mouths open.

‘Why?’ I say.

Very slowly, he guides his eyes to the left. ‘Because they’re looking right at us.’

Chapter 4 (#ulink_80ab42e9-b2af-5f2b-aa3f-db4d4429dddd)

Madrid Barajas Airport, Spain.

Time remaining to Project re-initiation: 31 hours and 13 minutes

‘Oh, Jesus, they’re – they’re looking straight towards us,’ Patricia says, ducking behind me.

I stare now at our faces on the police alert in Chris’s hand, and a feeling wells inside me, one of guilt, of shame and confusion. By making friends, have I done the wrong thing? Is life not easier, better, safer when we are on our own?

‘Doc? Doc, you alright? Should we go?’

My head snaps up, refocussing. ‘Negative. If we move now it will alert the men. They have images of us. We must wait. We must prepare.’

Chris tips his head to the left towards a landslide of bodies approaching. ‘What about them?’

I direct my sight to where Chris points. A pack of students has entered the walkway, flooding the air with chatter in a melody of Italian and French, a river of language rushing forwards amid a sea of brown limbs, all long and lean and clad in assorted patchwork pieces of denim and cotton and hooded drawstring sweats. Tinny music, the tap of phones, beeps, rings. The sounds send my brain into red alert, and I am about to move when two teenage students stop almost next to me and kiss. I find myself staring, unable to look away, and when I inhale I detect bubble gum, washing powder, body odour masked by a sugary scent.

‘Hey, Google?’ A pause. ‘Maria?’

I turn to Chris. ‘What?’

‘They’re all moving – the students. If we move with them, they could be good cover.’

The teenagers pull away from each other, the girls smiling in a way I do not understand. The chatter rises, smacking into my ears, slap, slam. Startled, I look to Patricia.

‘It’s alright,’ she says automatically, trotting off what she’s had to say to me now so many times. ‘Deep breaths. It’s going to be loud and close, but I’ll stay right by you, yeah? Chris is right – the students’ll be good cover.’

I nod, but my eyes are on the moving mass. ‘Their skin, their scent.’

‘Deep breaths.’

Chris starts to move. ‘Let’s go.’

We dart in and out as, ahead of us, the boarding gates appear. People, limbs, spit and sweat. Announcements hanging from the ceiling with flashing orange letters and numbers declaring the areas our flight is leaving from. Our feet brush the tiles as we surge forwards amid the slippery mass, sliding across the mirrored thoroughfare where the shoes of the students clomp down in hooves of plastic and leather, jostling, laughing, bumping into me. Head down, I bite my lip and try not to scream.

Hidden by the human cloak, we remain out of direct sight. Some metres nearer now, the men move rapidly, steady, their presence two dark monoliths against the landscape of pick-a-mix colour. My heart rate rockets. We duck, weaving, as Chris keeps watch and Patricia spreads five fingers on her thigh, but every time someone’s arm or leg grazes me, I flinch. Every time I smell their burger breath, feel the heat of their perspiring skin near me – deodorant, talcum powder, flowers and musk – I want to scream at the top of my voice, curl up into a tight ball. It is impossible to switch off.

We finally approach the flight gates, Patricia to my right, Chris to my left. We drop our speed as the students slow down lolloping and laughing at each other, and as I risk a small glance, I find myself fascinated by their ease with each other, their calmness, happiness even, transfixed at the way in which their limbs seemingly absentmindedly intertwine, vines of arms and fingers interlinking as if all branches from the same tree. They oscillate and flutter, and I imagine a shoal of clownfish swimming over into a new anemone, relaxed, loose, just another day hanging in the reef.

I unpick my gaze from the students and inspect the two men. They are talking to each other.

‘They’re calling our flight,’ Patricia says.

The entrance to our boarding gate is drenched in sunlight from a vast glass and steel dome above. Glass, steel, huge masses of heavy concrete. I do the maths in my head.

‘If a bomb went off here, the glass would shatter and kill and maim the people beneath it.’

Chris stares at me. ‘Seriously?’

‘Of course.’

‘Oh shit. Shit!’ Patricia whispers. ‘They’re looking this way.’

She’s right. ‘Walk.’

We stride, not running, not wanting to create attention. Backs straight, footing as sure as we can make it, we mimic three busy work colleagues eager to catch their business flight. Soon we reach the gate. Patricia’s face is pale. Chris’s fingers are tapping his phone.

‘Good afternoon,’ the flight attendant says, his eyebrows two tapered caterpillars. ‘Boarding passes, please.’

We hand over our travel documents, fake IDs, as from my peripheral vision I see the two men searching through the students, casting them to the side, one after the other. The lights above shine bright, a traffic of chatter and laughter pummelling the air. I count to stay calm.

‘Hurry up,’ Patricia mutters, but, just as the line begins to move again, everything stops.

The flight attendant looks to us. ‘Could you step aside for a moment please?’

‘But we’re getting on the flight,’ Chris says.

My teeth start to grind. Breathe. One, two, three. One, two, three. The men are moving towards us in the pile of students washing up near the gate.

‘We have to run,’ Chris whispers.

‘Negative.’

‘Yes,’ he insists, stronger now. ‘The attendant’s stopped us.’

‘They are nearer now,’ I say.

Patricia’s eyes go wide. ‘Oh God.’

‘God has nothing to do with…’ I halt. Something is not right. The men have stopped. Their movements – why are they now so still? Keeping my head as rigid as I can, I check the CCTV cameras, their small domed lenses, dark black caps, blinking in the nearby areas. All seems as it should, all cameras facing the correct way, all security staff, in the immediate zone at least, carrying on with their duties as before.

Patricia shuffles from foot to foot. ‘Shall we peg it? This is fecking MI5. Shit.’

I trace the outline of the officers. They may have been trained, like me, to prepare, wait, engage. Is that what they are doing now? If I were them, what would I do next?

‘Doc? Doc, I think we should move.’

‘Holy fuck,’ Chris says.

I look to him. He is staring at his phone. ‘What is it?’

‘I’ve just…’ A shake of the head. ‘No way. It’s—’

‘They’re coming!’

We look up at where Patricia is staring. The second man, the one with the slightly narrower shoulders, is touching his ear, scanning to his right and moving slowly forwards. I track his eye line, wincing at the sharp clatter of some tray that is dropped in the distance, my assaulted brain just about keeping it together. What is he looking at, the man? What can he see?

I force my brain to focus, think clearly. Maybe Chris is right – maybe the flight attendants know who we are and have been informed to keep us back and make us wait.

I turn to Chris and Patricia. ‘We must go.’

Chris points to his phone. ‘You have to see this email.’

‘Not now. We must leave first.’

We all turn, ready to duck from sight and out of the airport, my mind already fast forwarding to a next plan to hide, when the flight attendant calls to us with a bright white smile beaming on his face.

‘Hello? I’m so sorry about the short delay.’ We hesitate. He gestures over to us. ‘If you’d just stand to the side and allow our late wheelchair passenger through, who we were waiting for, then you can board. Apologies for the inconvenience.’

We look to each other, the three of us, our chests visibly deflating, eyes blinking in what? Shock? Relief? I cannot tell, but we watch a wheelchair board the ramp and, with one nod of the attendant, we follow it fast through the final doors that lead to the plane ahead.

Outside, the Madrid air hits me. Aviator fuel, warm concrete, the roar of jet engines, all of it colliding in my head. I grind my teeth and blink at the blue sky that swirls through clouds spun with cotton. I stay close to Patricia.

As we reach the door of our Zurich-bound plane, Chris stops me.

‘I got an email.’ He swallows, catching his breath. ‘That’s what I was trying to tell you before.’

My heart rate shoots. Alarm bells sound. ‘From who?’

An attendant smiles. ‘Welcome to the flight. Boarding passes, please.’

I thrust her my pass, ignore her and turn to Chris. The woman frowns.

‘Who is the email from?’

Chris pauses then, lowering his voice, he tells me what I didn’t expect to hear.

‘It’s a reply from the UK Home Secretary – from Balthus’s wife.’

Chapter 5 (#ulink_c739672d-913c-57f6-9a92-051076ca1cc6)

Deep cover Project facility.

Present day

I’m not certain how I feel when I see Patricia held and behind the screen. Shock? Fear? Nothing? I am too scared to answer.

Stepping forward, I observe my former friend as if she were a specimen in a lab. On her head are fresh red lacerations. Deep bruises strangle her neck. Her body is clothed in a dirty grey t-shirt, ripped trousers hanging from her legs that lie crumpled at odd angles. She raises her eyes and calls out my name, but the officer kicks her in the stomach and her middle folds in, body collapsing flat to the floor. I want to slap my hand to my mouth, but something tells me that would be a bad thing to do right now.

‘What do you see, Maria?’ Black Eyes says, a crackle of something indefinable stepping across his voice.

‘Patricia,’ I say, quick, as steady as I can.

‘This O’Hanlon woman – she is not your family.’

‘No,’ I respond, ‘she is not.’ Patricia is looking at me with big eyes, but when before they were blue and clear and shining, now her eyes seem dulled and bloodshot.

He regards me, holding my face with his sight and I so desperately want to tap my finger, my foot, anything to help my mind deal with the intensity of the attention.

‘You had two fathers,’ Black Eyes says, ‘adopted, biological. Now both dead.’

A heartbeat. ‘Yes.’ My sight remains locked on Patricia.

He folds his arms across his chest, watching the scene behind the screen. The officer is hauling Patricia up, but her body must be weak, because her rib-caged torso keeps buckling, her legs bending, feet toppling.

‘I lost my father, too,’ Black Eyes says, sight on the screen. ‘I was fourteen. He was in the SAS.’

Beyond the window, Patricia whimpers. We observe, Black Eyes and I, riding for a moment in a slow seesaw of sound left, right, left, right.

‘Why is she here?’ I dare myself to ask.

‘She is here because she is the enemy. You do understand, don’t you, that after everything that’s happened, she is no longer your friend?’

Friend. I roll the word in my mouth, feel it, test it out. For a long time, I never really understood what having one meant.

‘You made the only choice you could, Maria, by being here. Here is where you belong. Patricia O’Hanlon is the enemy because she does not agree with the aims and objectives of the Project. She does not agree with you being here. Yet this?’ He stretches out his arms to the room. ‘This is where you belong.’

‘This is where I belong,’ I say, the words marching out of my mouth of their own accord.

‘That’s right. And you don’t need people like Patricia O’Hanlon when the Project is our only friend.’

He reaches forward and presses a button. The grey blind rolls down slowly, one centimetre at a time, but the movement of it must jolt Patricia awake as, suddenly, she raises her head, staggering up a little. She begins screaming.

‘Doc! Doc! Help me!’ She wobbles forwards. ‘Don’t listen to them, Doc! They’re lying! They’re all lying! They’re going to—’

The officer hits Patricia on the skull with the butt of his gun and she crumples, falling unconscious to the tiles. Without thinking, I slap my palms to the screen, startled, as before me the officer starts dragging Patricia’s clubbed-seal body out of the room.

‘Where are they taking her?’ I ask fast, pressing my face into the glass trying to see round the corner. ‘She needs help.’ I turn to Black Eyes. ‘Why did he do that? Why?’

I gulp in air, as to the side of me Black Eyes rolls back his shoulders, snapping the bones that puncture his spine one by one. He regards me as I stare at the screen as the blind descends, then he steps to his desk and picks up the photograph that sits on it.

‘When people we love die, it is often hard for us to cope with. Would you agree?’

I blink, the image of Patricia still fresh and raw in my head, not fully comprehending what is happening or why. Black Eyes holds the frame in his fingers closer to his face and as he does, I find myself staring at the picture of the two people in it, my brain prodded by some odd curiosity, a vague, foggy notion that they look familiar. Both female, the oldest appears to be in her thirties: slim, caramel skin, hair in long black cascades down a suited back, wide collar, wire-rimmed spectacles clutching high cheekbones and resting against thick branches of brows. Beside her is a girl, young, at estimate under ten years old, the same hair as the older woman, same features, just softer, plumper, the sharpness to her cheeks not yet defined, still hidden under an infantile cushion of baby milk and bread.

‘Who are they?’ I ask before I can stop myself.

He does not respond, seeming, at first, as if he will not say anything at all, but then he sniffs, takes a breath and traces one thin finger over the printed faces. ‘They are – were – my family.’ He swallows; the pointed triangle of his Adam’s apple juts out, then sinks in. ‘They passed away a long time ago.’

Returning the frame to its allocated slot on the desk, Black Eyes picks up the file from the table, clutches it to his chest, then stands and stares at the grey blind where Patricia once was. For a few seconds time is suspended, the air swinging in silence around us. I steal a glance at the photograph on the desk.

Ten seconds pass, until, raising his chin, Black Eyes strides to the door and, unlocking it, gestures to the white-washed gleam of the walkways beyond.

‘Come. It’s time I showed you something.’

Zurich Airport, Switzerland.

Time remaining to Project re-initiation: 28 hours and 30 minutes

From: Harriet Alexander (Secretary of State for the Home Department)

To: Maria Martinez

Subject: Re: The Project

Dear Dr Martinez,

Thank you for your email. I’ve had your message decrypted and have verified the details contained within it. This information now is for our eyes only and has been seen by only the most trustworthy members of my immediate staff. You managed to find my private email address, so I am responding directly from that – given the nature of the situation you have brought to my attention, I believe it’s our most secure method of communication at this time.

Firstly, you have my gratitude for informing me of the true cause of death of my husband, Balthazar. Balthus was a dear husband and, while I did not know of your existence, I am sorry for the sadness I am sure you must be feeling at this moment.

I have reviewed your files on this organisation called Project Callidus. Please be assured that I was unaware that this group existed. I am currently seeking to set up talks with the Chief of MI5 with a view to beginning an investigation, but, as I am sure you understand, timing with these things is everything and I have to be very careful and measured with what we do next. Your safety, Dr Martinez, is paramount.

To that end, I would be grateful if we could meet. I understand this may be a complicated request. However, I strongly believe that, after reviewing the initial data you relayed to me, a meeting between us would aid in the investigation in the Project and MI5’s involvement in it.

Please do consider my suggestion. In the meantime, there is one more thing. After hearing of Balthus’s status as your biological father, I was naturally curious about the woman he had a baby – you – with. You asked in your email about her grave and its location. I thought it only right and fair to share the information with you as to her status.

Her name, as you know, is Isabella Bidarte. She is from Bilbao, Spain. The last known location of her is Weisshorn Psychiatric Hospital in Geneva, Switzerland. She was born in May, 1968. I, first, after your grave location request, also assumed she was dead. However, after a confidential investigation by my closest team, I can tell you that Ms Bidarte is indeed still alive, her residence understood still to be the Weisshorn Hospital in Geneva.

I trust this news is of value to you. This has been difficult for me, as I am certain it has been for you. I am sorry for the distress you have, over the years, I am sure, been caused at the hand of our security services. I hope this news of your mother contributes in some way to atoning for that.

Please do consider strongly my request to meet with you in order to aid our vital investigations and put an end to Project Callidus’ operations. Let us keep secure lines of communication open.

Yours truly,

Harriet Alexander

I look up from Chris’s computer tablet at Patricia, my hands shaking at the shock, yet my brain curious and elated at the email.

‘She is alive,’ I say. ‘She is alive.’

Patricia comes close to my side, the milk of her skin and the warm bath of her scent reaching my brain. ‘I’m right here.’

She touches my fingers and my mind becomes a little calmer, small clouds of our breath billowing in the frozen air.

We are hidden by a wall outside Zurich Airport. Close by, the external glass façade of the busy building glistens by a freezing taxi rank and the pencil-straight road washed in paint strokes of sunshine, leaving weak yellow lines across fine snow-covered pavements. I pull out my notebook and the photograph Papa had hidden in Ines’s Madrid cellar. I gaze at Isabella’s face, at her river of hair, her flowing skirt, her baby – me – swaddled and held in arms so smooth and melodic they sing like swans. Could she really be alive? Could it be true? Or is the whole thing a fabrication? Quickly, I begin to write down the email contents, cross match for any patterns, hidden codes or messages, but no matter how hard I look, there is nothing secret to find.

Chris hurries over, cupping his hands and blowing on his fingers. ‘I thought spring was supposed to be warmer here.’

Patricia rolls her eyes. ‘Wimp.’

He stares at her, shudders, then looks to me. ‘Okay, so—’ He sneezes.

‘Bless you.’

He tilts his head at Patricia and raises one eyebrow; I have no idea why.

‘Okay, so,’ he continues, ‘I’ve double-tracked the email on my system and it’s from her alright – it’s from Harriet Alexander.’

I clutch the sepia-tone photograph in my fingers. ‘Are you certain?’

‘Yep. The thing is, she said what she said, you know, about investigating the Project, but if MI5 are tracking her then they’ll know she’s talking to you.’ He points to the email. ‘They’ll know now she’s planning to investigate it all.’

‘Doc,’ Patricia says, ‘he’s right. They’ll follow you and then MI5’ll want you dead and the Project will want you with them, just like before. The Home Secretary asked to meet you. Wouldn’t that be the right idea? She’s based in Westminster – it doesn’t get much safer than there. The Project and MI5 can’t get you then.’

‘Hang on though,’ Chris says. ‘What if she knows something – your mom, Isabella?’

I turn to him. ‘What do you mean?’

‘Okay, so, what if we find her and she can, I don’t know, tell us something to really put the nail in the Project’s coffin? Because the way I see it, you can’t trust—’

Patricia shakes her head. ‘No. No way. Too risky…’

‘A nail in a coffin?’ I say, but Patricia continues.

‘The police have our bloody pictures, Chris, for God’s sake. They’ll find us. And then MI5 will get to us before we get back to the UK and we’re all stuffed.’

‘Wimp,’ he says. ‘We’ll be fine.’

Patricia rolls her eyes and looks to me. ‘Doc, I don’t like it. It’s risky. God, I’d rather we went to the safe house of Chris’s in Zurich than go to the hospital in Geneva.’

There is a wall straight in front of us. It is beige, bland, the grouting along the brickwork in neat patterned lines, each one with a clear beginning and an obvious ending. I calculate the length of the edges to help my brain to think straight in the midst of the plane engine roar in the air around me, the birds in the swaying fir trees near the network of road and railways, the tremble of trolley wheels and the faint scent of distant cigarette smoke. Yet it is only when a lick of aviator fuel flicks my nostrils, jolting me upwards, that the thought occurs to me.

The brick and the grouting and the definable end. I think about that word – end – how it sounds and what it means…

Slowly at first then faster, I study the cellar picture in my hands then scan the dates scrawled on the back. ‘There is an end.’

Patricia looks over. ‘What d’you mean?’

I spin round to Chris, my mind moving at speed. ‘Isabella’s birth date and death date are both on this photograph.’

He looks.

‘If she is alive,’ I continue, brain planning now at lightning speed, ‘as the email said, why is the date of her death written here? It was written over two decades ago. The conclusion can only be that either my Papa wrote down the date without it being true or—’

‘Or the Home Secretary is lying,’ Chris says.

I look to him, his body stomping from foot to foot, his breath blowing small, white candy strands into the air, and for the first time since we arrived in Zurich, I feel a strong urge to turn to him and nuzzle my face in his neck and just smell him.

‘I have to know whether she is alive or not,’ I say now. ‘And if Weisshorn Hospital was her last known location then that is where we will go.’

Patricia stretches bolt upright. ‘Doc, no. I don’t think that’s a good idea. There’s a high chance she’s not there and then what? Why on earth d’you want to go there, Doc, when it’s so risky? Why?’

I stare at Isabella’s image. ‘She is the only family I have left,’ I say, quietly, softly.

Patricia’s shoulders drop. ‘Oh, Doc.’ Around us, lace patterns of snow float to the tarmac and evaporate into nothing. Patricia wipes her eyes, but doesn’t speak and when I inspect her left hand, I see her index finger and thumb pressing hard against each other so the skin is white.

‘Ok, so Google,’ Chris says. ‘You freak out on trains, right?’

I tear my sight from Patricia. ‘What?’

Chris leans against the wall and, fast, flips open his laptop. ‘There’s the Goldenpass route to Lausanne in Geneva. It’s long, but quiet, a tourist route, but not busy at this time of year. We can lie low.’ He looks to me, hair flopping in his eyes. ‘Would you be okay with that? It would mean it’s calmer for you to, well, to deal with.’

I study the details he has pulled up on the journey. Wide-open carriages, large windows, space, clean mountain air and no crowds. ‘We will have to change outfits so we are not recognised.’

‘No sweat. I’ve got untraceable credit cards that can buy us new stuff, and an uncanny ability to deactivate security cameras.’ He pauses, drops still for a moment, looks to the photograph in my hand. ‘Hey, we’ll find her, whatever the ending. We can go under the radar, figure out everything we can. We’ve done it before, we can do it again.’

I watch his lips move, smell his scent. ‘Can you hack into the Weisshorn Hospital, track any data?’

His face breaks out into a grin. ‘For you? Anything.’

Patricia coughs. ‘What’— she stops, swallows— ‘sorry – what time does the train depart?’

‘In one hour,’ Chris says. ‘We all ready to go?’

‘Yes.’ I throw my rucksack to my shoulder. ‘But first, I need to use the toilet facilities.’

‘Oh. Okay,’ Patricia says. She slips her cell phone from her bag, checks it and slides it out of sight.

Chapter 6 (#ulink_b2942ec1-1422-5005-90bc-d203609b3b89)

Goldenpass railway line, The Alps, Switzerland.

Time remaining to Project re-initiation: 26 hours and 20 minutes

I am unable to pull my eyes from the palette of watercolour before me. Aching blue lagoons of sky sifting in a mist of citrus and orange peel. Carpets of green grass shoots sprinkled with sugar flakes of snow all scattered among petals of spring painted with brush strokes of yellows and lilacs and multi-coloured confetti. Majestic mountains rise up, backs straight, muscles taut, mountains that, each time I gaze at them, each second I take in their strong, solid presence as they whisk past the window, a lump forms in my throat. When my sight drifts up to the fading turquoise of the sky, my breathing softens, and I think to myself that no matter what happens, no matter what wars are raged, what lives are slain, what untruths are spewed and sewn, the mountains that soar high above us are always there. Solid, present and true.

‘Doc, you okay?’

I peel my forehead from the window. Patricia now wears a wine-red sweat top with a hood and pocket, and on her legs blue jeans the colour of the night sea hug her skin. Her brown wig is still in place, as is Chris’s bottle-blonde mane as he sits by us hunched over his laptop. We are all now casually dressed, but, despite the simple comfort of the clothes, the fresh cardboard cotton of the t-shirt I currently wear itches my skin, irritating me. It’s unbearable, so I go to take it off, but Patricia reaches forward.

‘No, Doc. Not here.’

I stop. ‘Why?’

‘People don’t get changed down to their bras in public places.’

I drop my hand. ‘Oh.’

Scratching my stomach to bat away the clothing annoyance, I glance round the carriage. It is sparse. An old man with white hair wearing a pressed herringbone coat, black tie, cotton-blue shirt sits two seats beyond reading a daily newspaper containing headlines about the NSA and their surveillance of the German Head of State. Near to him is perched a young woman, small bird-like shoulders hunched over a worn-out copy of Animal Farm, the dog ears of the cover touching the tips of ten porcelain fingers as she turns the page, nails bitten, faded black jeans on petite, slim legs.

The only other group in the carriage is a father in his early thirties with two children, both boys under the age of ten, one nestled under each arm. The children are swaddled in navy blue duffle coats sewn with eight toggles apiece and they sit across a wooden table, opposite an elderly woman whose stomach and chin rest in kneaded batches of dough, square metal-framed glasses perched on the tip of a podgy nose as, making conversation with the small family, she points out the various Alpine sights that trundle past.

I observe the father for a moment, watch the way he smiles each time one of his sons whoops or claps at spotting a random cow or a snow-covered mountain top. A father, living, breathing. I hold my gaze on the family scene then, swallowing hard, I touch the picture of my Papa and the photograph of Isabella and her baby.

‘Hey,’ Patricia says, leaning forwards a little, ‘what’ve you done to your thumb?’

‘What?’

‘Your thumb – have you hurt yourself?’

I glance down at the small wound peeking out beneath a pale plaster still partially wet with blood. ‘I cut it.’

‘Where?’

‘In the toilets in Zurich.’

She leans forward. ‘Ooof, that looks sore. Must have been some wallop you gave it.’

I hide my hand out of sight and try to ignore the sting. ‘It is healing.’

The train jostles on and I take out my notebook, careful to avoid contact with my thumb. I check our current location against the brief list I have compiled to help me tackle the journey. Places, times, exact locations, short, sketched scenarios.

Satisfied we are on schedule, I peer through the wide window again and breathe easier. I turn my attention to Chris and his laptop.

‘Have you hacked the Weisshorn database yet?’

He shakes his head. ‘Yeah, but it doesn’t make sense.’

‘What does not make sense?’

Chris sits back, scratches his chin. ‘Well, okay, so I’m in their system, yeah – the hospital’s. I still can’t find Isabella’s name, but, either way, there seems to be some kind of glitch with my computer.’ He swivels his laptop to me and points. ‘See it?’

There are a series of numbers, stretching across the screen and linking to the database Chris is trying to hack. ‘They are codes,’ I say.

He nods. ‘I know, right? And every time I click on them, the screen shakes, just for a second.’ He shows me, and, sure enough, it shakes.

Patricia leans in to see. ‘Why’s it doing that?’

‘No idea. I’ve checked the OS, but it’s all fine.’

‘Can you not tell using a file or something and bypass the shake, or whatever you do?’

‘Nope. My trace files won’t open right now. No idea why.’

Connections firing, I rip open my notebook and cross-reference my written data with the online file then sit back. Nerves prick my spine. Something is not right. I wait for a second, think through the program on the laptop with the details in my notebook from dreams long gone. The motion of the train back and forth, the rhythm and gentle chug of the sound and its predictable pattern soothes my brain, and I flip through my cerebral files, checking, referencing, interweaving the recalled data in my mind as if it were open in a book in front of me. Connections, link, numbers…

‘There’s a thread,’ I say finally, noting that just five seconds have passed.

Chris’s eyes flip wide open. ‘Jesus, that was quick.’ He’s right – even for me that was fast work. The train, the lull of it, the empty white bowl of the mountains and snow – that must be enabling my mind to work at such speed. Patricia watches me closely, frowning.

‘The thread,’ I continue, scanning the laptop, ‘is linked by an algorithm like this one’— I swivel my notebook to him— ‘that attributes a line at the back of this hacking program into the hospital.’

‘What? You serious?’ He peers at the page. ‘You got all that from there? But what does it mean?’

I try to think it through, but the woman with Animal Farm breaks open a baguette of ham and cheese and the scent flicks at my nostrils. Butter, stale bread, sloppy ham with veins of fat, the sugary fug of processed cheese. I pinch my nose shut and, trying to focus on anything but the smell, look to Chris’s laptop and the information from the hospital contained on it. The data merges together in my mind, line after line of it racking up a catalogue of knowledge at such speed and with such force that I have to slam my palm down on the table to steady myself. I am aware of the stares towards me, but I ignore them, focus on the screen as, slowly then faster still, an answer begins to form, until, with fear, I realise what is happening.

‘There is a tracker.’ I swallow. ‘It’s linked to the program, activated when you connected with the hospital database.’ How did I come to that conclusion so fast?

‘What?’ Chris studies the screen, eyes wide. ‘Holy fuck! But if they’ve targeted my actual laptop it means that, whoever’s done that, whoever’s singled this device out must have done it deliberately. They must have known I’d try and get into Weisshorn and as soon as I did, they sent a virus to my computer to locate it. Fuck.’

‘It may not be deliberate. It is common for servers to have an instant defence virus attack sent out when any hacking is detected.’

Chris’s shoulders drop and his features visibly soften. ‘Oh God, d’you think so? God, yeah, shit. I should know that – do know that. Sorry. I’m just… Fuck. This kind of stuff makes me nervous.’ He leans over his laptop, fingers moving fast. ‘I’ll cut all links now to their database and get out of there. I have software that should stop any viruses, but it must have bypassed it.’

Patricia watches us. ‘What if hacking into that database means they know where we are? I mean, they can do that, right? Find locations and stuff?’

We stare at her. Chris swallows. ‘She’s right.’

‘So it would be better,’ Patricia says, ‘if we… if we get off this train?’

Chris smacks the laptop shut, throws his hands up as if the computer were a hot coal, a burning ember. ‘Shit. Shit, shit, shit.’

Panic wells inside me at the prospect of the Project finding us before the investigation can cull them. I steady myself, gaze out at the patches of snowflakes that stick on the window. Outside, deep lakes give way to fields of fir trees and sugar-dusted green pasture. Sometimes I imagine that if I look at nature long enough, it will make everything better and, like the snowflakes melting on the warmth of the window, it will all disappear.

I turn to speak to Chris, when a tannoy announces in French, German then English that Brunig-Hasliberg is the next station up. At the barking sound, my hands slap to my ears while, ahead, the two boys whoop and clap and tell their father that this is the best train trip ever, and can they have some sweets.

Patricia looks to me. ‘Doc?’ She jabs a finger to her ears. ‘The tannoy’s stopped.’

‘We need to get off this train as soon as we can,’ Chris says. He is fidgeting – does that mean he is anxious? ‘I’ll have to leave this laptop on here so they won’t find us – it’ll be full of the virus now.’ He fumbles over a paper map looking for a station.

I lower my hands. ‘Interlaken Station would provide a good place to alight the train as it is located between lakes Thun and Brienz. It will therefore provide more places to hide, and better access to more low-key transport opportunities. It is also a place popular with backpackers.’

Chris nods. ‘Okay, yeah – I see where you’re going with this. If it’s full of backpackers, we can slip right in, unnoticed. Awesome.’

‘It’s not on our routine, Doc,’ Patricia says to me. ‘Will an unscheduled stop be okay with you? I’m not sure if you can cope.’

‘I can… cope.’

Patricia gives me a flicker of a smile. I drink in her face, her soft smile, and feel happiness. Soon the train begins to ascend, lurching and heaving through the white dust of the mountain that yawns steep through the Brunig pass. As I observe the lakes laid out in mirrors of deep blue ice alongside our carriage of glass and gold, I worry about the tracker linked to Chris’s computer, and so to remain calm, I watch Patricia and I tell myself how lucky I am to have finally found, amid this confusing world that changes in a heartbeat of time, someone whom I can truly trust.

Deep cover Project facility.

Present day

We walk along a white corridor with low-level bulbs that do not assault my senses. All is quiet.

Black Eyes strides by my side. In his hand is clutched his folder, and in the light that glows down in calm, controlled pools beneath our boots, his fingernails appear to glisten as they pinch the plastic edges of the documents.

We reach a junction and halt. Having witnessed Patricia behind the glass pane just moments before, I am jittery and my finger taps the side of my thigh where my combats skim my skin, The cold air gives me goose bumps. Black Eyes shifts his vision down. He regards my finger where it flaps and, with a flicker of a frown, he flares his nostrils and returns his chin to its upright position. No one speaks.