Subject 375

Subject 375

Nikki Owen

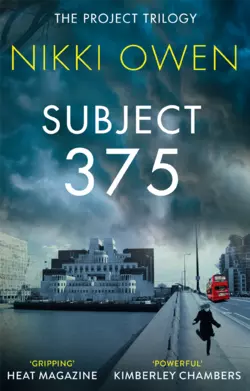

’Powerful and gripping – an adrenaline-filled thriller you won't forget' – Sunday Times bestseller Kimberley ChambersWhat to believeWho to betrayWhen to run…‘Powerful and gripping’ – Kimberly Chambers‘A gripping and tense thriller’ – Heat‘A must have’ – Sunday ExpressPlastic surgeon Dr Maria Martinez has Asperger’s. Convicted of killing a priest, she is alone, in prison and has no memory of the murder.DNA evidence places Maria at the scene of the crime, yet she claims she’s innocent. Then she starts to remember…A strange room. Strange people. Being watched.As Maria gets closer to the truth she is drawn into a web of international intrigue and must fight not only to clear her name but to remain alive.As addictive as the Bourne novels, with a protagonist as original as The Bridge’s Saga Norén.Don’t miss the first instalment of Nikki Owen’s electrifying Project Trilogy, perfect for fans of Nicci French and Charles Cumming.Previously published as The Spider in the Corner of the Room'Fast-paced thriller that leads into a web of international intrigue, building with pace to a dramatic finale.' Gloucestershire Gazette“One of the UK’s most exciting new thriller writers” Talk Radio Europe‘Truly excellent!’ My Weekly

NIKKI OWEN is a writer and columnist. As part of her degree, she studied at the acclaimed University of Salamanca—the same city where her protagonist of Subject 375, Dr Maria Martinez, hails from. Born in Dublin, Nikki now lives in Gloucestershire with her family.

Subject 375

Nikki Owen

To Dave, Abi and Hattie—my beautiful little family

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (#u012c9ca6-6FFF-11e9-9e03-0cc47a520474)

The thing about writing a book is that it’s not just one person who does it. Well, it is, ultimately, but I guess what I’m saying is, it can’t be achieved without the support of some, quite frankly, awesome people. Not to mention strong coffee. And chocolate. Oh and, it turns out, my running shoes.

So thanks to everyone. To my blog buddies who have been with me right from the outset. Made some friends there, learnt a lot—cheers, folks. And to all the bleary-eyed, coffee-mug-clutching gang on Twitter via #the5oclockclub. We’ve almost been asleep at our laptops, but, somehow, we’ve managed to work. Ta, chaps. Gratitude, also, to the 6.30 a.m gang down at the swimming pool. I’d get there, yawning my head off, hammering out the lengths. Thanks, swim gang, for the laughs and chats in the showers (it’s not what it sounds…).

Big up has to go to the Gloucestershire Twitterati. You all know who you are. I doff my hat. And to my Facebook buddies—cheers, you lot, for enduring my posts about the crazy, amazing year that was 2014. Between us all, we keep it real.

When you’re in the first throes of writing a book, you need help. Wine, of course, is handy, but so too are people who you can trust to read your manuscript and feed back their comments without you running to hide under the nearest duvet. So my heartfelt thanks to my mum. She was there to read the very first version of Spider back when it was still really just a germ of an idea. Thanks, too, to Tracy Egan for reading the second version and giving me invaluable feedback. And cheers to Kellie Duke, also. Kellie—book club reader extraordinaire—remember when I called you from the car on the long journey to see you, Al and the kids? We hammered out the last few scenes when we arrived at your house (wine open…). You helped so much, Kels. We may cry on the ski slopes together, but we can rock a book edit.

Next up: neighbours. No, not the Australian TV soap, although, to be fair, that was the defining show of my generation (Scott and Charlene getting married anyone?). No, I mean my wonderful friends two doors down, Marg and Brian. You are such dear people. We are blessed to live near you, to have you as friends. Marg—thanks for the stout advice, the cinema trips, which we love (even if the film sucks). You are two of life’s truly great people. Huge hugs.

And speaking of friends, over to Jayne and Katrina. Jayne—thank you so much for being my buddy. We’ve known each other since that first time sitting in the postnatal club with our three-week-old newborns, looking like a truck had hit us. We didn’t know how to stop a baby crying, but we did know a good friend when we saw one. Thanks, my wonderful buddy. And Katrina—sweedy darling! I remember that time we first nattered to each other—knew I’d found a kindred spirit, i.e. someone who appreciates the necessity of a good belly laugh and puts her foot in it almost as much as me. Cheesy balls. That’s all I’m going to say…

You need a literary agent to get a book on the go and I have the nicest, sharpest, smartest-dressed agent in town. Adam Gauntlett—thanks. From the first moment I received your e-mail about my MS submission when you were on a flight from Chicago, I knew this was going to be good. You’ve been on my side from the word go. You got what Spider was about straight away, you gave me huge help when I hit a low and you introduced me to the concept of booking a London cab via an app. Who knew? Adam—you are one cool dude. Cheers, A.

Thing is about this literary agency lark, just like this book-writing business, is that it takes teamwork. So thank you to everyone at PFD, my agency. To Marilia, Tim, Jonathan and the entire gang—you have all helped me in so many ways. Buckets of gratitude. Oh, and not forgetting Marlow the PFD dog. He likes a close haircut.

And from agency to publisher. Everything about Spider has been about enthusiastic people. And the gang at Harlequin MIRA are just that. Sally—you are an amazing editor. I mean really great. The feedback and advice you’ve given me on structuring Spider have been spot on. So thanks, Sally, and cheers, too, to all the HQ MIRA team—it’s an honour to be with you.

I have two children and when you work over the summer hols, you need help. So thank you to Wendy and Barrie, the best parents-in-law ever. Thanks for looking after the girls when Dave and I were working, and being just so lovely.

But the final and biggest thanks has to go to my family. My beautiful, perfect little family. To Dave, my husband, and to my two beautiful girls—Abi and Hattie. This is where I cry. Because I can’t write without them. DJ—you always believed in me even when I didn’t. You kept me going, supplied me with chocolate, looked after the girls while I typed madly for a deadline. You are my best friend, even if you do have a worryingly large Land Rover habit. You and me against the world, babe. And Abi and Hattie, my smart, strong girls—you are the best daughters in the world ever, amen. Thank you for your notes, banners and pictures for the study. Love you to infinity and beyond.

So there you go. It wasn’t just me who wrote Spider, it was all these people too. And now you are reading it, so my gratitude has to go to you. Thank you for buying my book. I truly am honoured. It’s going to be a blast.

#teamSpider

Table of Contents

Cover (#u012c9ca6-1FFF-11e9-9e03-0cc47a520474)

About the Author (#u012c9ca6-2FFF-11e9-9e03-0cc47a520474)

Title Page (#u012c9ca6-3FFF-11e9-9e03-0cc47a520474)

Dedication (#u012c9ca6-4FFF-11e9-9e03-0cc47a520474)

ACKNOWLEGEMENTS

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Extract (#litres_trial_promo)

Endpages (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 1 (#u012c9ca6-6FFF-11e9-9e03-0cc47a520474)

The man sitting opposite me does not move. He keeps his head straight and stifles a cough. The sun bakes the room, but even when I pull at my blouse, the heat still sticks. I watch him. I don’t like it: him, me, here, this room, this…this cage. I feel like pulling out my hair, screaming at him, at them, at the whole world. And yet I do nothing but sit. The clock on the wall ticks.

The man places his Dictaphone on the table, and, without warning, delivers me a wide smile.

‘Remember,’ he says, ‘I am here to help you.’

I open my mouth to speak, but there is a sudden spark in me, a voice in my head that whispers, Go! I try to ignore it, instead focus on something, anything, to steady the rising surge inside me. His height. He is too tall for the chair. His back arcs, his stomach dips and his legs cross. At 187.9 centimetres and weight at 74.3 kilograms, he could sprint one kilometre without running out of breath.

The man clears his throat, his eyes on mine. I swallow hard.

‘Maria,’ he starts. ‘Can I…’ He falters, then leaning in a little: ‘Can I call you Maria?’

I answer instinctively in Spanish.

‘In English, please.’

I cough. ‘Yes. My name is Maria.’ There is a tremor in my voice. Did he hear it? I need to slow down. Think: facts. His fingernails. They are clean, scrubbed. The shirt he wears is white, open at the collar. His suit is black. Expensive fabric. Wool? Beyond that, he wears silk socks and leather loafers. There are no scuffs. As if he stepped fresh out of a magazine.

He picks up a pen and I risk reaching forward to take a sip of water. I grip the glass tight, but still tiny droplets betray me, sloshing over the edges. I stop. My hands are shaking.

‘Are you okay?’ the man asks, but I do not reply. Something is not right.

I blink. My sight—it has become milky, a white film over my eyes, a cloak, a mask. My eyelids start to flutter, heart pounds, adrenaline courses through me. Maybe it is being here with him, maybe it is the thought of speaking to a stranger about my feelings, but it ignites something, something deep inside, something frightening.

Something that has happened to me many times before. A memory.

It sways at first, takes its time. Then, in seconds, it rushes, picking up speed until it is fully formed: the image. It is there in front of me like a stage play. The curtains rise and I am in a medical room. White walls, steel, starched bed linen. Strip lights line the ceiling, glaring, exposing me. And then, ahead, like a magician through smoke, the doctor with black eyes enters by the far door. He is wearing a mask, holding a needle.

‘Hello, Maria.’

Panic thrusts up within me, lava-like, volcanic, so fast that I fear I could explode. He steps closer and I begin to shake, try to escape, but there are straps, leather on my limbs. Black Eyes’ lips are upturned, he is in the room now, bearing down on me, his breath—tobacco, garlic, mint— it is in my face, my nostrils, and I begin to hear myself scream when there is something else. A whisper: ‘He is not real. He is not real.’ The whisper, it hovers in my brain, flaps, lingers, then like a breeze it passes, leaving a trace of goosebumps on my skin. Was it right? I glance round: medicine vials, needles, charts. I look at my hands: young, no lines. I touch my face: teenage spots. It is not me, not me now. Which means none of this exists.

Like a candle extinguishing, the image blows away, the curtains close. My eyes dart down. Each knuckle is white from where they have gripped the glass. When I look up, the man opposite is staring.

‘What happened?’ he says.

I inhale, check my location. The scent of Black Eyes is still in my nose, my mouth as if he had really been here. I try to push the fear to one side and, slowly, set down the glass and wring my hands together once then twice. ‘I remembered something,’ I say after a moment.

‘Something real?’

‘I do not know.’

‘Is this a frequent occurrence?’

I hesitate. Does he already know? I decide to tell him the truth. ‘Yes.’

The man looks at my hands then turns his head and opens some photocopied files.

My eyes scan the pages on his lap. Data. Information. Facts, real facts, all black and white, clear, no grey, no in-betweens or hidden meanings. The thought of it must centre me, because, before I know it, the information in my head is coming out of my mouth.

‘Photocopying machines originated in 1440,’ I say, my eyes on the pages in his hands.

He glances up. ‘Pardon?’

‘Photocopiers—they emerged after Johannes Gutenberg invented the printing press in 1440.’ I exhale. My brain simply contains too much information. Sometimes it spills over.

‘Gutenberg’s Bible,’ I continue, ‘was the first to be published in volume.’ I stop, wait, but the man does not respond. He is staring again, his eyes narrowed, two blue slits. My leg begins to jig as a familiar tightness in my chest spreads. To stop it, I count. One, two, three, four…At five, I look to the window. The muslin curtains billow. The iron bars guard the panes. Below, three buses pass, wheezing, coughing out noise, fumes. I turn and touch the back of my neck where my hairline skims my skull. Sweat trickles past my collar.

‘It is warm in here,’ I say. ‘Is there a fan we can use?’

The man lowers the page. ‘I’m told your ability to retain information is second to none.’ His eyes narrow. ‘Your IQ—it is high.’ He consults his papers and looks back to me. ‘One hundred and eighty-one.’

I do not move. None of this information is available.

‘It’s my job to research patients,’ he continues, as if reading my mind. He leans forward. ‘I know a lot about you.’ He pauses. ‘For example, you like to religiously record data in your notebook.’

My eyes dart to a cloth bag slung over my chair.

‘How do you know about my notebook?’

He stays there, blinking, only sitting back when I shift in my seat. My pulse accelerates.

‘It’s in your file, of course,’ he says finally. He flashes a smile and returns his gaze to his paperwork.

I keep very still, clock ticking, curtains drifting. Is he telling me the truth? His scent, the sweat of his skin, smells of mint, like toothpaste. A hard knot forming in my stomach, I realise the man reminds me of Black Eyes. The thought causes the silent spark in me to ignite again, flashing at me to run far away from here, but if I left now, if I refused to talk, to cooperate, who would that help? Me? Him? I know nothing about this man. Nothing. No details, no facts. I am beginning to wonder if I have made a mistake.

The man sets down his pen and, as he slips his notes under a file to his left, a photograph floats out. I peer down and watch it fall; my breathing almost stops.

It is the head of the priest.

Before he was murdered.

The man crouches and picks up the photograph, the image of the head hanging from his fingers. We watch it, the two of us, bystanders. A breeze picks up from the window and the head swings back and forth. We say nothing. Outside, traffic hums, buses hack up smog. And still the photo sways. The skull, the bones, the flesh. The priest, alive. Not dead. Not splattered in blood and entrails. Not with eyes frozen wide, cold. But living, breathing, warm. I shiver; the man does not flinch.

After a moment, he slips the photograph back into the file, and I let out a long breath. Smoothing down my hair, I watch the man’s fingers as they stack paperwork. Long, tanned fingers. And it makes me think: where is he from? Why is he here, in this country? When this meeting was arranged, I did not know what would happen. I am still unsure.

‘How does it make you feel, seeing his face?’

The sound of his voice makes me jump a little. ‘What do you mean?’

‘I mean seeing Father O’Donnell.’

I sit back, press my palms into my lap. ‘He is the priest.’

The man tilts his head. ‘Did you think otherwise?’

‘No.’ I tuck a stray hair behind my ear. He is still looking at me. Stop looking at me.

I touch the back of my neck. Damp, clammy.

‘Now, I would like to start the interview, formally,’ he says, reaching for his Dictaphone. No time for me to object. ‘I need you to begin with telling me, out loud, please— in English—your full name, profession, age and place of birth. I also require you to state your original conviction.’

The red record light flashes. The colour causes me to blink, makes me want to squeeze my eyes shut and never open them again. I glance around the room, try to steady my brain with details. There are four Edwardian brick walls, two sash windows, one French-style, one door. I pause. One exit. Only one. The window does not count— we are three floors up. Central London. If I jump, at the speed and trajectory, the probability is that I will break one leg, both shoulder blades and an ankle. I look back to the man. I am tall, athletic. I can run. But, whoever he is, whoever this man claims to be, he may have answers. And I need answers. Because so much has happened to me. And it all needs to end.

I catch sight of my reflection in the window: short dark hair, long neck, brown eyes. A different person looks back at me, suddenly older, more lined, battered by her past. The curtain floats over the glass and the image, like a mirage in a desert, vanishes. I close my eyes for a moment then open them, a random shaft of sunlight from the window making me feel strangely lucid, ready. It is time to talk.

‘My name is Dr Maria Martinez Villanueva and I am— was—a Consultant Plastic Surgeon. I am thirty-three years old. Place of birth: Salamanca, Spain.’ I pause, gulp a little. ‘And I was convicted of the murder of a Catholic priest.’

A woman next to me tugs at my sleeve.

‘Oi,’ she says. ‘Did you hear me?’

I cannot reply. My head is whirling with shouts and smells and bright blue lights and rails upon rails of iron bars, and no matter how hard I try, no matter how much I tell myself to breathe, to count, focus, I cannot calm down, cannot shake off the seeping nightmare of confusion.

I arrived in a police van. Ten seats, two guards, three passengers. The entire journey I did not move, speak or barely breathe. Now I am here, I tell myself to calm down. My eyes scan the area, land on the tiles, each of them black like the doors, the walls a dirt grey. When I sniff, the air smells of urine and toilet cleaner. A guard stands one metre away from me and behind her lies the main quarter of Goldmouth Prison. My new home.

There is a renewed tugging at my sleeve. I look down. The woman now has hold of me, her fingers still pinching my jacket like a crab’s claw. Her nails are bitten, her skin is cracked like tree bark, and dirt lines track her thin veins.

‘Oi. You. I said, what’s your name?’ She eyes me. ‘You foreign or something?’

‘I am Spanish. My name is Dr Maria Martinez.’ She still pinches me. I don’t know what to do. Is she supposed to have hold of my jacket? In desperation, I search for the guard.

The woman lets out a laugh. ‘A doctor? Ha!’ She releases my sleeve and blows me a kiss. I wince; her breath smells of excrement. I pull back my arm and brush out the creases, brush her off me. Away from me. And just when I think she may have given up, she speaks again.

‘What the hell has a doctor done to get herself in this place then?’

I open my mouth to ask who she is—that is what I have heard people do—but a guard says move, so we do. There are so many questions in my head, but the new noises, shapes, colours, people—they are too much. For me, they are all too much.

‘My name’s Michaela,’ the woman says as we walk. She tries to look me in the eye. I turn away. ‘Michaela Croft,’ she continues, ‘Mickie to my mates.’ She hitches up her T-shirt.

‘The name Michaela is Hebrew, meaning who is like the Lord. Michael is an archangel of Jewish and Christian scripture,’ I say, unable to stop myself, the words shooting out of me.

I expect her to laugh at me, as people do, but when she does not, I steal a glance. She is smiling at her stomach where a tattoo of a snake circles her belly button. She catches me staring, drops her shirt and opens her mouth. Her tongue hangs out, revealing three silver studs. She pokes her tongue out some more. I look away.

After walking to the next area, we are instructed to halt. There are still no windows, no visible way out. No escape. The strip lights on the ceiling illuminate the corridor and I count the number of lights, losing myself in the pointless calculations.

‘I think you need to move on.’

I jump. There is a middle-aged man standing two metres away. His head is tilted, his lips parted. Who is he? He holds my gaze for a moment; then, raking a hand through his hair, strides away. I am about to turn, embarrassed to look at him, when he halts and stares at me again. Yet, this time I do not move, frozen, under a spell. His eyes. They are so brown, so deep that I cannot look away.

‘Martinez?’ the guard says. ‘We’re off again. Shift it.’

I crane my head to see if the man is still there, but he is suddenly gone. As though he never existed.

The internal prison building is loud. I fold my arms tight across my chest and keep my head lowered, hoping it will block out my bewilderment. We follow the guard and keep quiet. I try to remain calm, try to speak to myself, reason with myself that I can handle this, that I can cope with this new environment just as much as anyone else, but it is all so unfamiliar, the prison. The constant stench of body odour, the shouting, the sporadic screams. I have to take time to process it, to compute it. None of this is routine.

Michaela taps me on the shoulder. Instinctively, I flinch.

‘You’ve seen him then?’ she says.

‘Who?’

‘The Governor of Goldmouth. That fella just now with the nice eyes and the pricey tan.’ She grins. ‘Be careful, yeah?’ She places her palm on my right bottom cheek. ‘I’ve done time here before, gorgeous. Our Governor, well, he has…a reputation.’

She is still touching me, and I want her to get off me, to leave me alone. I am about slap her arm away when the guard shouts for her to release me.

Michaela licks her teeth then removes her hand. My body slackens. Without speaking, Michaela sniffs, wipes her nose with her palm and walks off.

Lowering my head once more, I make sure I stay well behind her.

Chapter 2 (#u012c9ca6-6FFF-11e9-9e03-0cc47a520474)

We are taken through to something named The Booking-In Area.

The walls are white. Brown marks are smeared in the crevices between the brickwork and, when I squint, plastic splash panels glisten under the lights. Michaela remains at my side. I do not want her to touch me again.

The guards halt, turn and thrust something to us. It’s a forty-page booklet outlining the rules of Goldmouth Prison. It takes me less than a minute to read the whole thing— the TV privileges, the shower procedures, the full body searches, the library book lending guidelines. Timetables, regimes, endless regulations—a ticker tape of instructions. I remember every word, every comma, every picture on the page. Done, I close the file and look to my right. Michaela is stroking the studs on her tongue, pinching each one, wincing then smiling. Sweat pricks my neck. I want to go home.

‘You read fast, sweetheart,’ she says, leaning into me. ‘You remember all that? Shit, I can’t remember my own fucking name half the time.’

She pinches her studs again. They could cause problems, get infected. I should tell her. That’s what people do, isn’t it? Help each other?

‘Piercing can cause nerve damage to the tongue, leading to weakness, paralysis and loss of sensation,’ I say.

‘What the—’ The letter ‘f’ forms on her mouth, but before she can finish, a guard tears the booklet from my hand.

‘Hey!’

‘Strip,’ the guard says.

‘Strip what?’

She rolls her eyes. ‘Oh, you’re a funny one, Martinez. We need you to strip. It’s quite simple. We search all inmates on arrival.’

Michaela lets out a snort. The guard turns. ‘Enough out of you, Croft, you’re next.’

I tap the guard’s shoulder. Perhaps I have misunderstood. ‘You mean remove my clothes?’

The guard stares at me. ‘No, I mean keep them all on.’

‘Oh.’ I relax a little. ‘Okay.’

She shakes her head. ‘Of course I mean remove your clothes.’

‘But you said…‘ I stop, rub my forehead, look back at her. ‘But it is not routine. Stripping, now—it’s not part of my routine.’ My stomach starts to churn.

The guard sighs. ‘Okay, Martinez. Time for you to move. The last thing I need is you getting clever on me.’ She grabs my arm and I go rigid. ‘For crying out fucking loud.’

‘Please, get off me,’ I say.

But she doesn’t reply, instead she pushes me to move and I want to speak, shout, scream, but something tells me I shouldn’t, that if I did, that if I punched this guard hard, now, in the face, I may be in trouble.

We walk through two sets of double doors. These ones are metal. Heavy. My pulse quickens, my stomach squirms. All the while the guard stays close. There are two cleaners with buckets and mops up ahead, and when they see us they stop, their mops dripping on the tiles, water and cleaning suds trickling along the cracks, the bubbles wobbling first then popping, one by one, water melting into the grouting, gone forever.

One corner and two more doors, and we arrive at a new room. It is four metres by four metres and very warm. My jacket clings to my skin and my legs shake. I close my eyes. I have to. I need to think, to calm myself. I envision home, Spain. Orange groves, sunshine, mountains. Anything I can think of, anything that will take my mind away from where I am. From what I am.

A cough sounds and my eyes flicker open. There, ahead, is another guard sitting at a table. She coughs again, glances from under her spectacles and frowns. My leg itches from the sweat and heat. I bend down, hitch up my trousers and scratch.

‘Stand up.’

She snaps like my mother at the hired help. I stand.

‘You’re the priest killer,’ she says. ‘I recognise your face from the paper. Be needing the chapel, will you?’ She chuckles. The standing guard behind me joins in.

‘I do not go to church,’ I say, confused.

She stops laughing. ‘No, bet you don’t.’ She cocks her head. ‘You could do with a bit more weight on you. Skinny, pretty thing like you in here?’ She whistles and shakes her head. ‘Still, nice tan.’

She makes me nervous—her laughs, jeers. I know how those people can be. I pull at the end of my jacket, fingers slippery, my teeth clenched just enough so I can keep quiet, so my thoughts remain in my head. I want to flap my hands so much, but something about this place—this guard—tells me I should not.

The sitting guard opens a file. ‘Says here you’re Spanish.’

I reply in Castellano.

‘English, love. We speak English here.’

‘Yes,’ I say. ‘I am Spanish. Castilian. Can you not hear my accent?’

‘This one thinks she’s clever.’ I turn. The other guard.

‘Well, that’s all we fucking need,’ says sitting guard, ‘a bloody know-it-all.’ She spoons some sugar into a mug on the table. I suddenly realise I have had nothing to drink for hours.

‘I would like some water.’

But she ignores me. ‘Martinez, you need to do as we tell you,’ she says, stirring the mug.

She has heaped in four mounds of sugar. I look at her stomach. Rounded. This is not healthy. Before I can prevent it, a diagnosis drops out of my mouth, babbling like a torrent of water through a brook.

‘You have too much weight on your middle,’ I say, the words flowing, urgent. ‘This puts you at a higher than average risk of cardiac disease. If you continue to take sugar in your…‘ I pause. ‘I assume that is tea? Then you will increase your risk of heart disease, as well as that of type two diabetes.’ I pause, catch my breath.

The guard holds her spoon mid-air.

‘Told you,’ says standing guard.

‘Strip,’ says sitting guard after a moment. ‘We need you to strip, smart arse.’

But I cannot. I cannot strip. Not here. Not now. My heart picks up speed, my eyes dart around the room, frenzied, a primitive voice inside me swelling, urging me to curl up into a ball, protect myself.

‘You have to remove your clothes,’ sitting guard says nonchalantly. She blows on her tea. ‘It’s a requirement for all new arrivals at Goldmouth.’ She sips. ‘We need to search you. Now.’

Panic—I can feel it. My heartbeat. My pulse. Quickly, I search for a focus and settle on sitting guard’s face. Acne scars puncture her chin, there are dark circles under her eyes, and on her cheeks, eight thread lines criss-cross a ruddy complexion. ‘Do you consume alcoholic beverages?’ I blurt.

‘What?’

Perhaps she did not hear. Many people appear deaf to me when they are not. ‘Do you consume alcoholic beverages?’ I repeat.

She smiles at standing guard. ‘Is she for real?’

‘Of course I am real. See?’ I point to myself. ‘I am standing right here.’

Sitting guard shakes her head. ‘For fuck’s sake.’ She exhales. ‘Strip.’ Then she sips her drink again.

My chest tightens and my palms pool with sweat. ‘I cannot strip,’ I say after a moment, my voice quiet, the sound of it teetering on the edge of sanity. ‘It is not bedtime, not shower time or time for sex.’

Sitting guard spurts out a mouthful of tea. ‘Fuck.’ Taking a tissue from her pocket, she wipes her face. ‘Jesus. Look,’ she says, scrunching up the tissue, ‘I am going to tell you one more time, Martinez. You need to take your clothes off now so we can search you.’ She pauses. ‘After that, I will have no choice but to carry out the strip myself. Then you’ll be placed in the segregation unit as a penalty.’

She folds her arms and waits.

I wipe my cheek. ‘But…but it is not time to strip.’ I swivel to the other guard, begging. ‘Please, tell her. It is not time.’

But the guard simply rolls her eyes, presses a blue button by an intercom and waits. No one speaks, no one moves. A few more tears break out, trespassing across my face, down past my chin, stinging my skin, alien to me, unknown. I do not cry, not often. Not me, not with my brain wired as it is; I am strong, hardened, weathered. So why now, why here? Is it this place, this prison? One hour in and already it is changing me. I touch my scalp, feel my hair, fingertips absorbing the heat from my head. I am real, I exist, but I do not feel it. Do not feel anything of myself.

Shouts from somewhere drift in then out, their sound vibrating like a buzzer in my ears. I try to stay steady, to think of home, of my father, his open arms. The way he would pick me up if I was hurt. I inhale, try to recollect his scent: cigars, cologne, fountain pen ink. His chest, his wide chest where I would lay my head as his arms encircled me, the heat of his torso keeping me safe, safe from everything out there, from the world, from the merry-go-round of confusion, of social games, interactions, dos and don’ts. And then he was gone. My papa, my haven, he was gone—

Bang. The door slams open. We all look up. A third guard enters and nods to the other two. The three of them walk to my side.

‘No!’ I scream, shocked at my voice: wild and erratic.

They stop. My chest heaves, my mouth gulps in air. Sitting guard’s eyes are narrowed and she is tapping her foot.

She turns to her colleague. ‘We’re going to have to hold this one down.’

Time has passed, but I cannot be sure how much.

The room is dark, a single light flashing. I look down: I am sitting on a plastic chair. I gulp in air, touch my chest. The material, my clothes: they are different. Someone has put me in a grey polyester jumpsuit. I look around me, frantic. Where are my clothes? My blouse? My Armani trousers? I draw in a sharp breath and suddenly remember. The strip search. My stomach flips, churns, the vomit flying up so fast that I have to slap my palm to my mouth to keep it in. Their hands. Their hands were all over me. Cold, rubbery, damp. They touched me, the guards, probed me, invaded me. I said they could not do it, that it was not allowed, to cut my clothes off like that, but they did it anyway. Like I didn’t have a voice, like I didn’t matter. They told me to squat, naked, to cough. They crouched under me and watched for anything to come out…They…

A screech rips from my mouth. I stand, stumble back against the wall, the bricks damp and wet beneath my fingertips. This must be the segregation cell. They put me in segregation. But they can’t do this! Not to me. Do they not know? Do they not understand? I turn to the wall, smacking my forehead on it, once, twice, the impact of the pain jolting me into reality, calming me. Slowly, I start to steady myself when I feel something, something etched into the masonry. Turning, I peer down, squint in the blinking lights, feel with my fingers. There, scratched deep into the brickwork, is a cross.

A shout roars from outside. I jump. There is another shout followed by banging, ripping from the right, loud, like a constant thudding. Maybe someone is coming. I run to the door and try to see something, anything. The banging reaches a crescendo then dies.

I press my lips to the slit. ‘Hello?’ I wait. Nothing. ‘Hello?’

‘Go away!’ a voice screams. ‘Go away! Go away!’

The yelling smashes against my head like a hammer— slam, slam, slam. I want it to stop but it won’t, it simply carries on and on until I can’t take it any more. My hands rake through my hair, pull at it, claw it. I cannot do this, cannot be here. I need my routine. I want to go home, see my bare feet running through the grass along the hills back to my villa, the sun fat and low. I want to sprint the last leg to the courtyard where the paella stove is fired. Garlic, saffron, clams and mussels, the hot flesh melting in my mouth, bubbling, evaporating. That is what I want. Not this. Not here. Think. What would Papa tell me to do?

Numbers. That is it. Think of numbers. I shut my eyes, attempt to let digits, calculations, dates, mathematical theories—anything—run through my head. After a moment, it begins to work. My breathing slows, muscles soften, my brain resting a little, enough for something to walk into my head: an algorithm. I hesitate at first, keep my eyes shut. It seems familiar, the formula, yet strange all at once. I scan the algorithm, track it, try to understand why I should even think of it, but nothing. No clue. No sign. Which means it’s happened again. Unknown data. Data has come to me, data I do not recall ever learning, yet still it appears, like a familiar face in the window, a footprint in the snow. I have always written the calculations down when they emerge, these numbers, these codes and unusual patterns, have always recorded them obsessively, compulsively. But now what? I have no notepad, have no pen, and without inscribing them, without seeing the data in black and white, will it exist? Will it be real?

More shouting erupts and my eyes fly open. There are so many voices. So loud. Too loud for me, for someone like me. I clamp my hands to my ears. My head throbs. Images swirl around my mind. My mother, father, priests, churches, strangers. They all blur into one. And then, suddenly an illusion, just one, on its own, walks into my mind: my father in the attic. And then I see Papa getting into his Jaguar, waving to me as he accelerates off, my brother, Ramon, by my side, a wrench in his hand. There is no sound, just pictures, images. My breathing becomes quick, shallow. Am I remembering something or is it simply a fleeting dream? I close my eyes, try to will the image back into my brain, but it won’t come, stubborn, callous.

There is more banging—harder and louder this time. I tap my finger against my thigh over and over. Papa, where are you? What happened to you? If only I had stayed in Spain, then none of this would have happened. No murders. No blood.

I clutch my skull. The noise is drowning me, consuming me. The banging. Make the banging stop. Please, someone, make it stop. Papa? I am sorry. I am so, so sorry.

My breathing now is so fast that I cannot get enough oxygen. So I try cupping my hands around my mouth to steady the flow, yet the shouting outside rises, a tipping point, making me panic even more. I force myself to stand, to be still, but it does not work. I can hear guards. They are near. Footsteps. They are yelling for calm, but it makes no difference. The shouts still sound. My body still shakes.

And that is when I hear a voice say, ‘Help me,’ and I am shocked to realise it is mine. I scramble back, shoving myself into the wall, but it does no good.

The cell turns black.

Chapter 3 (#u012c9ca6-6FFF-11e9-9e03-0cc47a520474)

When I finish talking, I check the clock by the door: 09.31 hours.

How did time move so quickly? I dab my forehead, shift in my seat. I feel disorientated, out of place like a cat suddenly finding itself in the middle of the ocean. Something must be happening to me again, some change or some type of transition. But what?

The man checks his Dictaphone. He remains silent and places a finger on his earlobe. Sometimes, I have noticed, while I talk, he pulls at his ear. He was doing it just now when I was telling him about the strip search. It is only a small tug, a quick scratch, but still it is there. I have tried to detect a pattern in his actions, perhaps a timed repetition, but no, nothing. I shake my head. Maybe being in this room is affecting my senses. Or maybe I am simply searching for something that is not there. I tap my foot, check my bag is there, my notebook, my pen. I can’t trust my thoughts any more, my deductions, and yet I do not know why, not fully. And it scares me.

‘Maria, before your conviction, you came to the UK on a secondment, correct?’

I clear my throat, sit up straight. ‘Yes. I was seconded to St James’s Hospital, West London, on a one-year consultancy in plastic surgery.’

‘And where did you work in Spain?’

‘At the Hospital Universitario San Augustin in Salamanca. I worked on reconstructive surgery mainly developing…‘ I stop. Why does he remain so calm when I speak, ghost-like almost, an apparition? My throat constricts, jaw locks.

‘And why did you come here, to London?’

‘I told you,’ I say, a steel in my voice that I never intended, ‘I was seconded.’

He smiles, just a little, like a single dash of colour from a paintbrush. ‘I know that, Maria. What I mean is, why, specifically, London? Someone of your talent? You could have gone anywhere. I hear your skills are in demand. But you chose here. So, I ask again: why? Or, shall I say, for who?’

My foot taps faster. Does he know about him? About how he betrayed me? I glance at the door; it is locked.

‘Maria?’

‘I…’ My voice trembles, lets me down. This man, sitting opposite, he said he is here to help me. Can he? Do I risk letting him in?

‘I was looking for someone,’ I say after a short while.

He immediately straightens up. ‘Who? Who were you looking for?’

‘A priest.’

‘The one you were convicted of killing?’

The curtains swell, the morning breeze draughting in a whisper of a memory. Aromas. Incense. Sacred bread, holy wine. The comforting smell of a wood-burning stove, the dim lights of a vestry, a stone corridor, confessional boxes. The inner sanctum of Catholicism.

‘Maria,’ the man says, ‘can you answer my—’

‘It wasn’t the dead priest I came looking for.’

The man holds my gaze. It is unbearable for me, the eye contact, makes my hands grip the seat, makes my throat dry up, but still he stays fixed on me, like a missile locked to its target.

‘Then who?’ he says finally, his eyes, at last, disengaging enough for me to look away.

‘Father Reznik,’ I say, my voice barely audible. ‘I took the London secondment because I was looking for Father Reznik. Mama said he may have moved here, but she wasn’t sure. I needed answers.’ I pause. ‘I needed to find him.’

There is a flipping of a page. ‘And Father Reznik was your family priest, a Slovakian, correct?’

I look up. How does he know all this? ‘Yes.’

‘And your mother knew him?’

Again I answer yes. ‘She is Catholic, attends church twice a week, confession also. She said Father Reznik may have had some family in London.’

He nods, writes something down, glancing at me in between words.

‘He was my friend. Father Reznik was my friend. And then…events happened. I found out that he…‘ I stall, touch my neck. The bloodshot whites of his eyes, the sagging pale skin on his jaw, the slight wheeze when he walked. Even now when I think of him, of what he did, it hurts me. And while I know the man is speaking to me, I barely hear him, barely process what he says, because I can’t comprehend what I think is still happening, what is developing right in front of me, in front of the whole world. And they don’t even know it, don’t even realise what is being done right before their eyes, like they’re all wandering the streets blindfolded.

‘Maria?’ The man lowers his pen. ‘This Father Reznik. Are you sure about him?’

I squeeze my fist, concentrate. ‘What do you mean?’

He hesitates. ‘Are you sure he was your friend?’

A trace of a memory floats in the air, like a drowsiness. I see me, sixteen years old. Father Reznik’s drawn, lined face is swaying in front of me as I try to focus on a paper containing codes. Lots of codes. I smile at him, but when I blink, I realise it’s not Father Reznik I am looking at. It is the dead priest from the convent. I gasp.

‘Maria?’ The man’s voice hovers somewhere. ‘Stay with me. Listen to me.’

I attempt to shake away the confusion. The faces, the blurred, blended shapes swim one more time before me then dive from view. I sit forward, cough. My eyelids flicker.

‘What made him your friend, Maria?’

‘He was kind to me. He…he would spend time with me when I was young, growing up.’ A surge of heat scalds my skin. I swallow a little and loosen my collar, try to push aside the doubt creeping up like ivy inside me.

‘What else?’

‘He would…listen to me after Papa died, would give me things to do, keep me occupied. I grew up with him, with Father Reznik. Mama knew him. He gave me problems to solve when I got bored with school. “Too easy for you, school, Maria,” he would say. “Too easy.” I would visit him every day; even when I was at university I would go home to see him, he would give me complex problems to solve. And then, one day, he just vanished. But sometimes…sometimes I recall…’

‘Recall what?’

‘Absences,’ I say, after a moment, and even as the word comes out, I know it will seem unusual, because just as Father Reznik vanished, so had my memory.

‘What sort of absences?’

‘Absences of my memory, of what I had done and said.’

‘And when did these occur?’ the man says, writing everything down.

I hesitate. I know now what Father Reznik really was and what he was doing with me. But what do I tell this man? ‘I would often wake up in Father Reznik’s office.’

‘You had fallen asleep?’

‘No, no, I…’ I stop. What will happen if I reveal the truth to him now? I opt to stick to the basic facts. ‘Yes, I could have fallen asleep.’

The man stares at me. My heart knocks against my chest, my brow glistens. Did he believe me?

‘Tell me, Maria,’ he says, pen in his mouth, ‘are you scared of losing people?’

‘Yes,’ I hear myself say. A tear escapes. I touch it, surprised. My papa’s face appears in my mind. His dark, full hair, his warm smile. I didn’t realise all this had affected me so much.

The man’s eyes flicker downwards then finally rest on my face. ‘Would it help you if I told you I have lost a brother?’

I frown. ‘How? Where did he go? How did…?’ I falter, a familiar slap of realisation. He didn’t lose track of his brother. His brother died.

He hands me a tissue. ‘Here.’

I take it, wipe my eyes.

‘He was killed in the 9/11 bombings,’ the man continues. ‘He was an investment banker, worked on the hundredth floor of the first tower.’ He pauses, his body strangely stiffening, at odds with his so far relaxed poise. ‘Everything changed that day.’ He inhales one long, hard breath. ‘I still search for his face in crowds now.’ He stops, looks down. ‘Sometimes, our desire to see someone again burns so much that we convince ourselves they still exist.’ He locks his eyes now on mine, his body charged. ‘Or we project their personality onto another person.’ He tilts his head. ‘Like with your priest.’

His words hang in the air like a morning mist over a river. We sit, the two of us, in a soup of silence, of faces, of contorted, clouded memories. I think of the murdered priest, of Father Reznik. Sometimes I cannot see where one begins and the other ends.

Like clouds parting in the blue sky, the man’s body softens. He is back to normal, whatever normal is. He clears his throat, and, consulting his notes, tilts his head. ‘Maria, I want you tell me: when were you diagnosed with Asperger’s?’

I do not want to answer him. He is smiling, but it is different this time, and I cannot decipher it. Is he pretending to be nice? Is it because he likes me? Is that why he told me about his brother? I let out a breath; I have no idea. ‘I was diagnosed at the age of eight,’ I concede finally.

His smile drops. ‘Thank you.’ He immediately writes some notes. The air blows cold and I feel strangely unsteady. Why am I uncomfortable with this man? It’s as if he could be a friend to me one minute, a dangerous foe the next. And then it comes to me.

‘Your name!’ I say, pleased with myself. ‘I do not know your name. What is it?’

His pen hovers mid-air, an unexpected slice of a scowl lingering on his lips. ‘I think you know it, Maria.’

I shake my head. ‘No. The service could not tell me who would be here today as it was a last-minute appointment.’

‘I think you are mistaken, Maria, but I’ll tell you. Again. It’s Kurt. My name is Kurt.’

Kurt. I had not been told. I am certain of this. Certain. I knew the meeting would be with one of their staff, of course. The service issued a date, a time, place. But as it was a late booking, interviewer names were unconfirmed. They said that. They did. My memory is not lying. I did not want to do it at first, to be here, but he said it would do me good. I wanted to believe him. But, after everything that has happened, it is hard to trust anyone any more.

A knock sounds on the door and a woman enters. Leather jacket, bobbed brown head of hair. She glances at Kurt and sets down a tray of coffee.

‘Who are you?’ I demand. When she does not reply, I say, ‘I did not order coffee.’

Continuing to ignore me, the woman nods to Kurt and leaves. He reaches forward and picks up a mug. ‘Smells great.’

‘Who was she?’ But Kurt does not answer. ‘Tell me!’

He inhales the steam, the scent of ground coffee beans circling the room. He takes a sip and sighs. ‘Damn fine coffee.’

My body feels suddenly drained, my legs tired, my head fuzzy, my brain matter congealed like thick, cold stew. Hesitating, I slowly reach for a cup. The warmth of the coffee vapour instantly rises to my face, stroking my skin. I take a small mouthful.

‘Good?’

The hot liquid begins to thaw me, energise me. I drink a little more then lower the cup. ‘Your name. It is Kurt.’

He nods, the cup handle linked like a ring to his finger.

‘Kurt is a German name, no?’

‘Yes,’ he says. ‘I believe it is German.’

‘In German, Kurt means “courageous advice”. In English, it means “bold counsel”.’

‘I read you liked names. Like writing everything in your notebook, the names are an obsession. It’s a common trait on the spectrum. Your memory, your ability to retain information,’ he says, sitting back, ‘is that the Asperger’s or something else?’

I go still. Why would he ask me this? Does he know? ‘What else would it be?’ I say after two seconds.

‘You tell me.’

‘Why would you ask what else it would be?’ I can feel a panic rising. I try taking more coffee and it helps a little, but not much.

‘You know it is normal for me to enquire about your Asperger’s, about how you can do what you do? I am a therapist. It is my job.’

I look at him and my shoulders drop. I’m tired. Maybe I am inventing a non-existent connection here, conjuring thoughts and conclusions like a magician, plucking them from the air. How would he know what we discovered? The answer is he can’t know, so I need to be calm. I drain my coffee and try to concentrate on facts, on solid information to clear my fog.

‘What is your family name?’ I say.

‘You mean surname?’ Kurt shakes his head. ‘I’m sorry, Maria, I cannot say. Company policy.’

‘You are lying.’ I set the cup down on the table.

He sighs. ‘I do not lie.’

‘Everybody lies.’

‘Except you, correct? Isn’t that what you would say, Maria? I have seen your file, read your details.’ He smiles. ‘I know all about you.’

We both remain very still. Kurt’s eyes are narrowed, but I cannot determine what it means. All I know is that I have a tightening knot in my stomach that will not subside, with a voice in my head telling me again to run.

‘I have it in my notes,’ he says after a moment, ‘that following your blackout in segregation, you received help.’

‘Yes,’ I say quietly, the recollection of that day painful for me to think about. The room feels suddenly warm. I undo two buttons on my blouse, followed by a third; the fabric flaps against my skin in the morning breeze. I exhale, try to relax.

Kurt coughs.

‘What?’ I follow his eyeline. My chest. I can see the cotton of my bra.

‘Nothing.’ Another cough. ‘Maria, can you…can you tell me what help you received following your blackout in segregation?’

I pause. I know now exactly who tried to help me. And why. ‘A psychiatrist came to the segregation cell.’

He hits record. ‘I want you to tell me about that.’

He stares at me for three seconds. I rebutton my blouse.

Day must now be night because above my head the strobe lights hum, making me blink over and over, like staring straight at the sun.

I fall back, try to think, but my body throbs, my muscles and skin a sinew of stress. The signs. Normally I recognise them, can quell them, control them, but in here I cannot get a handle on myself, on my thoughts. I force my eyes shut and make myself think of my father. My safe place, my hideout. I inhale, try to imagine the soft apples of his cheeks, how his eyes would crinkle into a smile when he saw me, how he would sweep me into his arms, strong, secure. I open my eyes. My pulse is lowered, my breathing steady, but it is not enough. I need to think. If I remain in segregation I may not survive for long. I have to get out. But how?

I lower myself into the chair, my prison suit clinging to my skin, a stench of body odour jeering me. I am a mess. I hate to be in this state, out of control, in disarray. Allowing my body to slacken, I let my arm hang behind me. My fingers trace the cross, etched into the wall. I almost smile, because wherever I go, it is there: religion. All the priests, their rules. All of them controlling my mind, dictating life to me and everyone else, to a people, to a country, a government. Franco may have long died in Spain, but the Church will always be there.

I shake my head. Whether I want him to be or not, he is not in here now, the priest—he can’t be. So think. I must think if I want to get out of here. This is all just logic. The strip search. The incarceration. The segregation. Isolation. Fear. Panic.

I sit forward. Panic. Could that be it?

I glance at the door. Thick metal. Locked. Only one way out. Standing, I examine the room. Small. Three metres by five metres. One plastic chair: green, no armrest. One bed: mattress, no covers. Floor: rubber, bare. Walls: brick, half plastered in gunmetal grey.

I begin with my breathing; I draw in quick, sharp breaths, forcing myself to hyperventilate. It takes just over one minute, but, finally, it is done. My head swells and I try to ignore the dread in my stomach spreading through my body. I move to the cell door and bang hard, but my effort is lost in a sudden outbreak of shouts from the inmates across the walkway. I wince at the noise, count to ten, make a fist, bang again. This time: success. A guard shouts my name; she is coming over. I estimate it will take her seven seconds to reach my cell. I count. One, two, three, four. At five, I thrust my fingers down my throat. On seven, the window shutter opens above my head and a guard peers through.

‘Oh, shit!’

I vomit. My lunch splatters the floor.

A bolt unlocks. I count to three. One—two—three. I stumble, clutch my chest.

When the guard bursts in, she halts and mutters a swear word under her breath.

‘Martinez? You all right?’

I groan. Another guard enters. ‘Leave her! She’s bloody well fine.’

The guard by my side hesitates.

‘Come on!’ shouts the other.

My chance is slipping away. ‘Help,’ I croak, retching.

‘I’m sorry,’ crouching guard says, ‘but I think you are—’

I vomit. It sprays all over the floor, over the guard.

‘Oh, fuck.’

I mumble some words, but sick is lodged in my throat and it sounds as if I am choking.

‘Get a doctor!’ the guard shouts to her colleague. ‘Now!’

Chapter 4 (#u012c9ca6-6FFF-11e9-9e03-0cc47a520474)

The guard props me up against the wall. The brick is cold on my skin.

‘Is this cell five?’

There is a woman blocking the light by the cell door. She wears no uniform, has no baton.

The guard scowls at her. ‘Who the hell are you?’

The woman steps forward. Blonde hair snakes in a ponytail down her back. ‘I’m Dr Andersson,’ she says, her voice clipped, plum, like a newsreader. ‘Lauren Andersson, how do you do.’ She extends a neat little hand; the guard stands, ignores it.

Dropping her arm, Dr Andersson looks at me. ‘She needs to be out of here. Now.’

‘Hang on a minute,’ says the guard. ‘Who the hell put you in charge? I only want you to check her over.’

‘I’m responsible for the physical and psychiatric well-being of the inmates here,’ Dr Andersson says, side-stepping the vomit. She points to me. ‘This woman is Maria Martinez.’ She folds her arms. ‘And she has been assigned to me.’

‘Since when?’

‘Since today.’ She pushes past the guard, crouches down and takes my wrist. She looks to her watch, checks my pulse, releases my arm. ‘This inmate’s pulse is up. Get her out. Now.’ When the guard does nothing, Dr Andersson stands, her neck taut, voice raised. ‘I said, now.’

I am hauled up under the arms by two guards. Dr Andersson informs them that I am, under no circumstances, to be returned to the segregation cell.

‘I have the full backing of the Governor,’ she says. ‘Do you understand?’

The guards nod.

‘Good. Take her to my office.’

‘So, how are you feeling?’

I don’t know how to answer the question. I am in Dr Andersson’s office. She is sitting at her desk, staring at me. The room is cool, the light low. My pulse has dropped, but still my muscles tense, my fists clench. Everything is disorientating me.

Dr Andersson crosses her legs and her hem slips above her knee. Her cheeks are pink and she has eyes shaped like over-sized almonds.

‘My throat is sore,’ I say, touching my neck, avoiding eye contact.

‘That is to be expected, given the vomiting.’ She swivels to her right and picks up a blood pressure monitor. She opens the strap. ‘Can you roll up your sleeve?’

‘Why?’

‘Blood pressure. You know. Routine.’

I hesitate, then slowly pull up the arm of my jumpsuit to find an apple-sized bruise. I gasp.

‘You did that in the cell?’

‘I think so. I do not remember.’

She peers at it, then after slipping the strap around my bicep, begins pumping the pressure valve. The sound of wheezing fills the air.

‘That was a panic attack you had just now,’ she says, watching the valve. ‘Do you have them often?’

‘Yes.’ I watch the dial turn, try to breathe, remain calm. ‘You can stop now.’

Dr Andersson pauses then deflates the pressure valve and unstraps the band. ‘Your blood pressure is slightly high.’

I rub my arm were the strap has been. What is happening to my body?

Dr Andersson folds the monitor kit and sets it on a table to her left. ‘Do you have a headache?’

‘Yes.’

‘Front or b—’

‘Front.’

‘Light-headedness?’

I nod.

She picks up a notepad and pen. ‘Dizziness?’

I swallow. ‘All the symptoms of anxiety. Yes.’

I don’t want to believe it, but it has to be true. My high blood pressure means I am stressed. In here, in this prison. Anxiety. Worry. Trauma. None of them are good for me. But I do not know what to do, don’t know how to handle the feelings, how to curb them from taking over.

As Dr Andersson writes something down, I distract my thoughts by scanning the room. Boxes sit unpacked in the corner, medical books teeter, stacked next to her desk. There are no personal pictures on her table, no certificates on the wall.

‘Maria? Are you okay?’

I look down at myself. I am rocking. I had not even realised.

‘Here. Drink some water.’ She holds out a plastic cup.

I take it and sip. The water cools my throat.

‘So, do you want to tell me what happened in there, in the segregation cell?’

‘You already know. I had a panic attack.’ I put the cup on the desk, my heart rate rising again. Maybe if I change the subject. ‘You said in the cell that you are a psychiatrist.’

‘Oh, right, yes. That’s correct. I studied medicine at the University of Stockholm then specialised in psychiatry at King’s College, London.’

‘In what year did you qualify?’

She breathes out. ‘Look, Maria, I would love to give you details on my entire professional history, but to be frank—’

‘But I need you to tell me,’ I say, my voice rising. ‘It helps me to focus. The details, facts, they—’

‘But to be frank,’ she continues, louder, as if I hadn’t spoken, ‘that’s not what we’re here for. We are here to talk about you. To help you. You just had a major panic attack back there. Your blood pressure is up. You are experiencing classic symptoms of anxiety. So why don’t you let me help to calm you down, see how you are and guide you through all this, hmmm?’

‘Are you Swedish?’

She shakes her head. ‘Sorry?’

‘Your name. Andersson. It is Swedish.’

A sigh. ‘Look, Maria, can we—’

‘Lauren is a French name meaning “crowned with laurel”,’ I say at speed, desperate to cling on to any detail I can. ‘It has a Latin root that means “bay” or “laurel plant”. Lauren is the feminine form of the male name Laurence. In 1945, the name Lauren appeared for the first time in the top one thousand baby names in the United States.’

Dr Andersson stares at me. ‘Maria,’ she says after a moment, ‘have you ever talked to anyone about your Asperger’s?’

‘Why do you ask?’

She reaches to her desk and opens a file. My name is on the cover. ‘Your father,’ she says, opening the folder. ‘He died when you were ten. Correct?’

That stops me immediately. I swallow, nod.

‘How?’

‘Why do you want to know?’

She smiles. ‘Because I am your therapist here. And I need to know.’

I dart my eyes around the room. ‘You are new?’

‘Yes.’

My gaze settles on the half-open boxes. I pick out Dr Andersson’s name scrawled in black ink on the side and concentrate on it, so that when I speak about him, when the pain of the memory hits, it won’t be as hard. ‘It was a car accident in Spain,’ I say, eyes dead ahead. ‘Papa died in a car accident. He was returning from work. He was a prosecution lawyer.’

‘Maria, can you look at me?’

‘No.’ I am scared to. If I make eye contact, I may scream.

‘Okay. Okay.’ A quick clear of the throat. ‘Do you miss him, your father?”

I pull at a strand of hair by my ear. ‘Yes. Of course.’

She notes something down. ‘And how are you coping so far in prison with your Asperger’s?’

At this, I divert my attention to Dr Andersson’s watch. It is a TAG Heuer, loud tick. I can hear it in my head louder than I should. ‘My brain is making faster connections here.’ I stop. Everything is faster in this prison, in my head. I feel my arm where the blood pressure monitor squeezed my veins. The anxiety, the trauma—they must be the causes, the reasons why I feel different here. My head and my body are responding, trying to protect me. I think. The speed at which I could read the prison rules, suddenly recalling the algorithm in the segregation cell— it was all quicker, clearer. I have to write it down. Now. ‘I need a notepad and pen.’

‘Why?’

I pause. How do I describe it to her? How do I tell her that codes, numbers, data simply enter my head, procedures on how to complete tasks sauntering into my brain as if they own it. ‘I like to write information down, that is all.’

She suddenly sits forward. ‘Is that your Asperger’s?’ But before I can even reply, she is talking again. ‘You said your brain is making faster connections here.’

I clear my throat. ‘Yes.’

‘And is that normal?’

‘No.’

‘Can you tell me about it?’ When I do not respond, she says, ‘I can get you that notepad and pen.’

I look at her. Is she sincere? Is she on my side? I need that writing book, need to get this information out, like an itch that needs scratching. What choice, right now, do I have? I scan the room. There is a laptop on her desk. I stand and, leaning forward, pick it up.

‘Do you have something to unscrew this?’

Dr Andersson hesitates then, without speaking, opens a drawer and hands me a screwdriver. I unclip the back of the laptop and dismantle it. When all the insides of the laptop are spread out on the desk, I look up. ‘Time me on your watch.’

‘What?’

I point to her wrist. ‘Your watch. It has a stop clock function. I am going to reassemble this computer. Time me.’

She pauses, then slowly takes off her watch and lays it on the table.

Ignoring the intensity of her stare, I begin to reassemble the laptop. My fingers fly, putting everything back together. It is easy, like adding one to one, or drawing a circle on a piece of paper. Once each item is returned to its position, I pick up the screwdriver, replace the pins and secure the cover. I set down the screwdriver and flip over the laptop so it sits on the desk, right side up.

Dr Andersson clicks her watch and stretches out her hand. Her fingers skim the edge of the laptop.

‘What was my time?’ I ask.

‘Hmmm? Oh, thirty-seven seconds.’ Her eyes are still on the laptop. She looks to me, then drifts her gaze to the shelf above my head. ‘Try this,’ she says and, standing, reaches to the shelf and hands me something.

I take it. A Rubik’s Cube.

‘Can you do it?’

I turn the cube in my hand, study the colours. The red stands out more than the others, so much so that I have to squint.

‘How fast can you solve it?’

I hold up the cube. Its colours are all mixed up. ‘Press your stopwatch.’

She touches the button and I start. Swift. Skilled. I twist the sides, study each move, each turn until, just like that, the colours match. I bang it down on the desk, hardly a ripple in my breath.

Dr Andersson checks her watch but says nothing.

‘What was my time?’

She looks up yet still does not speak.

‘In 2011 at the Melbourne Winter Open Competition,’ I say, ‘the Rubik’s Cube record was set at 5.66 seconds. So that means—’

‘You did it in 4.62.’

I go still. I have never done it so quickly before. Four point six two seconds. My hand-to-eye coordination is accelerating, but why? How? I hold up my hands, study my fingers, blink at them as if they were precious diamonds, sparkling jewels.

Dr Andersson taps her chin. ‘That speed, that really is quite remarkable.’ She picks up a pen. ‘You have a high IQ, correct?’

I continue to stare at my hands. ‘Yes.’

‘Photographic memory?’

‘Yes.’ My hands return to my lap. I need to tap my thumb a little, let out the stress.

‘How are you at spotting patterns?’

‘Very good. A family priest used to help me when I was a little younger.’

‘A priest? Goodness.’ She sets down her pen, slips one leg over the other. ‘Okay, Maria, here’s what I think: it is possible the prison environment is affecting your Asperger’s. It certainly wouldn’t be the first time. All the sights, sounds, smells for your brain to process. Asperger’s is thought to be a result of widespread irregularity in the brain, a neurodevelopmental anomaly that could be controlled by environmental influences. There was a recent study in the US on it. Perhaps that is what we are seeing here with you.’

I think about this. ‘Prison is modifying my brain?’

‘In an accelerated fashion, yes. Maybe. But not modifying per se—that implies curtailing you. Let’s just say affecting your mind, hmm?’

I touch my head where my brain sits, my modified, neurodevelopmentally affected brain. There are times when I detest it, being me, my head, my neuro issues. Hate it. Locked into myself. Jailed by my own white and grey matter.

Dr Andersson swings her chair towards a cupboard behind her and opens the door. I rake my hands through my hair, scratching my scalp deliberately—my penance.

‘Maria, I just need to take some blood samples now.’

I drop my hands. My internal alarm bells ring. ‘Why do you require bloods?’

She hangs her head to the side. ‘Oh, just routine.’

‘But you are a psychiatrist…not a medic.’

She shuts the cupboard and faces the table. ‘I have a remit to monitor patients.’ She sets out five tubes and a blood-work bag already labelled with my name and prison number.

‘But I am an inmate, not a patient.’ I start to feel uneasy, agitated. I scratch the desk with my nail. ‘What tests are you sending to pathology?’

She unpeels the syringe wrapping. ‘I am sending a full blood count.’ She unwraps the additional four vials and picks up the one already loaded with the needle. ‘Okay?’

‘No.’ I shake my head, scratch harder. ‘No. My blood work is normal. And a full blood count request does not require five tubes of blood.’ I scrape the wood of the desk again and again. This is not routine. Over and over in my head, I repeat: This is not routine.

Dr Andersson lets out a sigh. ‘Look, Maria, I’m sure your blood work is normal. I’m sure it will come back fine. You are a doctor. A medical doctor.’ She says the word ‘medical’ slowly. ‘But you are here now. In Goldmouth. In prison. And in prison, there are different rules. And the rule, right now, is that I have to take blood. From you. Today.’ She pauses, softens. ‘I know it is a change for you, not routine, shall we say, being here. I understand your brain functions differently. And I know that is a struggle for you at times. But this is the way it has to be.’

I say nothing. The phrase, This is not routine, laps around my mind like a motorcycle with the accelerator permanently down, engine screeching, rubber tyres burning. I can’t stop it.

Dr Andersson bites her lip. ‘Maria, it’s okay. Trust me.’

This is not routine. This is not routine.

‘You’ve been through a lot,’ she continues. ‘Let me take the blood now. I have scheduled another appointment for you with myself and the Governor. All routine.’

The monologue in my head pauses, the engines stall. She said ‘routine’.

‘See?’ Dr Andersson says, nodding.

Slowly, I withdraw my hand from scratching. ‘This…this is a routine here, in prison?’ I say, gesturing to the needles.

‘Of course. And, with your Asperger’s, I have instructed the Governor that, in my professional opinion, you require extra assistance from me, to help with your need for routine.’ She smiles, but it doesn’t reach her eyes. ‘He has asked to meet you.’

‘When?’

‘Tomorrow. Is that okay?’

She has no certificates on the walls, no university degrees. As if she is not even certified to practice. It does not seem right, somehow. Yet, nothing seems right any more. Nothing makes sense. I rub my forehead, try to wipe away the confusion.

‘Maria?’

I point again to the needle, attempt to act like a normal person. ‘This is routine, you are certain?’

‘Yes.’

‘And you will get me a notebook and pen?’

She opens a drawer, takes out a fresh pad and pen. ‘There you go.’

My eyes go wide at the sight and I snatch them, hungry to hold them. Only when I have the items do I allow myself to exhale, my whole body loosening, limbs, bones tired, worn out, and I realise there, in the room, that I haven’t slept in forty-eight hours. Maybe routine is what I need. A routine and my writing. Maybe then I can begin to feel some semblance of humanity inside me, rather than some half-wild, chained-up animal. I roll up my sleeve and hold out my arm.

‘Thank you,’ Dr Andersson says.

Sitting forward and with a slash of a smile on her lily-white face, she taps my vein. The needle pierces my skin and I watch, weary, limp, as my blood floods into the vial.

Chapter 5 (#)

Kurt laces his fingers together. ‘So you are saying you simply took the laptop apart and put it back together?’

I have told Kurt everything, but he won’t move on from this. I can feel my body become rigid, angry. ‘Yes.’ I shift once in my seat. ‘That is what I said.’

He pauses. ‘And that is the truth?’

‘Yes. If I say it, it is true.’ I stay still. Does he not believe me? Why is he asking me all these questions about it?

‘You know our memories can play tricks on us,’ he says after a second. ‘What we think we remember cannot always be what actually happened.’

‘It happened,’ I snap.

He smiles at me, nods, but otherwise does nothing.

I tip back my head. Already, this is too much for me. My muscles ache and my shoulders feel heavy. Why is Kurt questioning what I have told him? Is it a therapist trick? Should I be on guard? Should I talk? I roll my head side to side. The session is tiring for me, the level of concentration, the social interactions—all exhausting. I flip my skull up and glance over to the window. The sun is sprinkled in a sugar-spin of clouds, and from the street below there is a shrill of laughter, the distant clink of glasses. People happy, living regular lives.

‘Maria?’

I turn from the window. ‘What?’

‘This meeting with the Governor, the one Dr Andersson mentioned. You did not know, prior to then, that you were to meet him?’

I pause. ‘No.’

‘Can you expand on that?’

I think for a moment. ‘No.’

He holds my gaze and I feel I want to squirm under the glare, unable to bear it. ‘What sort of things did he talk with you about, the Governor?’

I keep my eyes lowered. ‘The Governor introduced himself,’ I say. I smooth down my trousers twice. ‘He talked to me about why I was there, about the daily prison routine, the earned privilege scheme.’

‘And what else, Maria?’

I look up now. He is too inquisitive; I cannot tell him everything. Not yet. ‘Why do you want to know?’

He sighs. ‘Maria, I am your therapist. I ask questions. It is what I do.’ His eyes flicker to the corner of the room. It is only for a split second, but I see it.

‘Is there something there?’ I say, twisting my torso to look.

‘No. It’s nothing.’

I watch him. His legs are crossed, his back is straight. In control.

‘Maria?’

‘What?’

‘I would like you to tell me about it now.’

‘Tell you about what?’

‘About your meeting with the Governor.’

He reaches for a glass of water and that is when I pinpoint it: he is always in control. So why does his control make me nervous?

‘Maria,’ Kurt says, suddenly leaning in towards me so close that I can feel the warmth of his breath on my face, like the soft bristle of a brush. ‘Time to talk.’

I have a new cell.

It is in the regular section of the prison and it smells of cabbage and faeces. The source of the smell is the metal-rimmed toilet in the corner. There is no door, no screen. I stare at the cistern and the washbasin standing beside it. Dirty, grimy, vomit-inducing. The stench of urine hangs heavy in the air, impregnating it, penetrating every molecule, every tiny atom.

It is too much for me to process, the reality that I will have no privacy, ever, that it is all gone, my freedom vanished, like the pop of a bubble in the air. I close my eyes and try to think of Salamanca, think of the river, of eating long hot churros from the stand just off the main square, the scalding doughnut mixture melting in my mouth, the sugar dusting my lips, chin, cheeks. I remember how, on returning home with frosting around my mouth, my father would laugh—and my mother would march me to the sink and scrub me clean before she took me to church. To Father Reznik.

I open my eyes, and a guard enters. She is long like a rake, hair like tiny thorns. She informs me of my imminent therapy appointment with Dr Andersson and instructs me to follow her straight away. Not tomorrow, not in a minute: now. She repeats the instructions again and so, wondering perhaps if she thinks I don’t understand, I tell her that I know what the word ‘now’ means. She tells me to, ‘Shut the fuck up,’ then orders me to move out. I have to be escorted there, to Dr Andersson’s office. In prison, the guard barks; no one can be trusted.

The walk to Dr Andersson’s office affords me my first real look at Goldmouth Prison. The noise. The loud, loud noise. It is too much, on the cliff edge of unbearable. It is only the guard growling at me to, ‘Shift it,’ that prevents me from moaning over and over with hands on my ears, curled up like a foetus in the corner. I want to turn into a ball and block it all out. I am scared in here, in this place of loud, screeching sounds. The guard strides ahead and I force myself, will myself, to just keep going without doing what I usually do, because in here, I know they won’t understand. Nobody ever does.

I subtly sniff the air, detecting the smells as we walk. Sweat. Faeces. More urine. The scent of cheap perfume. Above me, arms dangle from metal rails, hanging, swinging like monkeys from a tree, around them animals pacing everywhere like lions and tigers, the predators, the purveyors of their territory. Gum is chewed like bark, whistles are called out like the howls of wolves. Faces peer down. Mouths snarl. Teeth and stomachs are all bared. The only similarity between me and the other inmates is that we are all convicts. All marked: Guilty.

The guard takes me across a flaking mezzanine floor, suspended one storey up from the ground. I count the levels. There are four floors to this prison, all housing forty cells, each with two inmates. That is eighty multiplied by four, equalling three hundred and twenty inmates. Three hundred and twenty women with hormones. All using toilets with no doors.

Once at Dr Andersson’s office, I am instructed to wait. The guard stands by my side, glaring, eyes like slits that make me nervous. I tap my foot in response; she barks at me to stop. I scan the area and see that rooms branch off from this corridor, door upon door stretching out every way, as far as my eye can see, strong, black doors, menacing, like ground soldiers, troops on watch. In the midst of it all is one door different to the rest, red, polished. It stands out, more refined, more elegant than the others. The plaque on it is partially obscured by the glare from the strip lights, but I can just read the first line: Dr Balthazar.

To my left, Dr Andersson’s door opens.

‘Ah, Maria.’ Dr Andersson is standing in the doorway. Her hair hangs down past her shoulders, glistening like a lake, her make-up in place, lips a slice of crimson. So different to me, my bare sallow skin, my shorn hacked-at hair, bitten nails. I feel suddenly small, insignificant. Forgotten. I touch my cheek.

‘Glad to see you looking better,’ she says.

‘I do not look better,’ I answer instantly. ‘I look worse than ever.’ The guard keeps her stare on me. Dr Andersson supplies me with a brief smile.

‘So, Maria,’ Dr Andersson continues, clearing her throat, taking a few heeled steps, ‘we have our meeting now. Could you come with me?’ She nods to the guard and the three of us proceed through the corridor.

We arrive at the red door and halt. Up close it almost gleams, the polished finish reflecting like a mirror. I catch sight of myself and gasp. Eyes black with dark circles, mouth downturned, lined, hair matted to my head, shoulders dropped. Already the prison is beating me, changing me, as if the priest’s death is slowly scratching its rigor mortis into my skin.

A buzzer sounds. I jump.

Dr Andersson pushes open the door. ‘Okay, we can go in now, Maria. We are meeting Dr Ochoa—the Governor.’

I glimpse at the plaque on the door now fully visible: Dr Balthazar Ochoa. I mull the name over. Ochoa. It means ‘wolf’. It is a Spanish name—Basque.

Which means the Governor somehow, in some connection, is Spanish.

Like me.

When we enter the office, the man from the corridor when I first arrived at Goldmouth is sitting at the desk.

I immediately halt, surprised. ‘What are you doing here?’

‘Maria,’ Dr Andersson whispers, ‘this is the Governor.’

I look at Dr Andersson then back to the man behind the table. ‘You are Governor Ochoa?’

He stands, looms over the table, a shadow casting across it. Up closer, he is taller, older, his skin more tanned. Two strips of grey bookend his ears and, when he smiles, wrinkles fan out from his eyes, soft, worn. And his eyes, they are deep brown, so dark that they take my breath away, remind me of something, of someone, some…I step back, once, twice. My heart shouts, perspiration pricks my palms. Why do I feel unexpectedly nervous, jittery almost?

‘Dr Martinez—Maria—please, there is nothing to be concerned about,’ he says now, his voice a ripple of waves over pebbles. ‘It is…very nice to meet you. Dr Andersson has told me a lot about you.’ He lingers on my face for a beat then clears his throat. ‘So, there are some aspects of Goldmouth I would like to talk to you about today. Will you please sit?’

He gestures to a set of chairs by his desk, smiling again, his teeth white, and I swear I can see them glow in the sunlight. I hesitate at first, unsure about him, but not knowing why, not knowing if I am safe here.