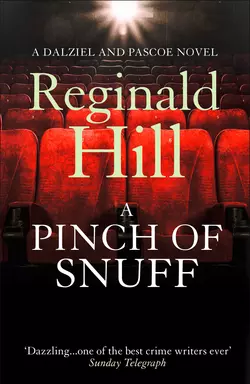

A Pinch of Snuff

Reginald Hill

‘Deplorably readable’ ObserverEveryone knew about the kind of films they showed at the Calliope Club – once the Residents’ Association and the local Women’s Group had given them some free publicity. But when Peter Pascoe’s dentist suggests that one film in particular is more than just good clean dirty fun, the inspector begins to make a few discreet inquiries. Before they bear fruit, though, the dentist has been accused of having sex with an underage patient, the cinema has been wrecked and its elderly owner murdered.Superintendent Dalziel expects no more from professional men who watch blue films. But Pascoe has a hunch that this time Dalziel is way off target…

REGINALD HILL

A PINCH OF SNUFF

A Dalziel and Pascoe novel

Copyright (#u6c4fab43-6061-549e-8da1-3cc3e619d8e2)

Harper An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street, London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by

HarperCollinsPublishers 1978

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Copyright © Reginald Hill 2003

Reginald Hill asserts the moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN 9780586072509

Ebook Edition © July 2015 ISBN 9780007370269

Version: 2015-06-18

Contents

Cover (#u0828f1d0-36d3-5a64-b43c-cfdbdbde27fd)

Title Page (#u6ffc6027-bd63-5042-a830-2ee3a2f8adcf)

Copyright

Epigraph (#ub082e3f0-e0f5-535f-bda5-d832bfcc4d3f)

Chapter 1 (#ucb7410d9-0a7a-5d19-bba9-b1519660b283)

Chapter 2 (#u006172b4-6cd4-511e-9704-0ff884b8ba78)

Chapter 3 (#u6d003a64-9d21-5605-8e3c-d8dcb0e6c462)

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author

Also by the Author

About the Publisher

Epigraph (#ulink_48f6458d-bce8-5e87-b3fd-dc90bd3b9f1e)

‘If you find you hate the idea of getting out of bed in the morning, think of it this way – it’s a man’s work I’m getting up to do.’

MARCUS AURELIUS: Meditations

Chapter 1 (#ulink_2cab13ca-46f2-5dbf-b184-42c067611ae7)

All right. All right! gasped Pascoe in his agony. It’s June the sixth and it’s Normandy. The British Second Army under Montgomery will make its beachheads between Arromanches and Ouistreham while the Yanks hit the Cotentin peninsula. Then …

‘That’ll do. Rinse. Just the filling to go in now. Thank you, Alison.’

He took the grey paste his assistant had prepared and began to fill the cavity. There wasn’t much, Pascoe observed gloomily. The drilling couldn’t have taken more than half a minute.

‘What did I get this time?’ asked Shorter, when he’d finished.

‘The lot. You could have had the key to Monty’s thunderbox if I’d got it.’

‘I obviously missed my calling,’ said Shorter. ‘Still, it’s nice to share at least one of my patients’ fantasies. I often wonder what’s going on behind the blank stares. Alison, you can push off to lunch now, love. Back sharp at two, though. It’s crazy afternoon.’

‘What’s that?’ asked Pascoe, standing up and fastening his shirt collar which he had always undone surreptitiously till he got on more familiar terms with Shorter.

‘Kids,’ said Shorter. ‘All ages. With mum and without. I don’t know which is worse. Peter, can you spare a moment?’

Pascoe glanced at his watch.

‘As long as you’re not going to tell me I’ve got pyorrhoea.’

‘It’s all those dirty words you use,’ said Shorter. ‘Come into the office and have a mouthwash.’

Pascoe followed him across the vestibule of the old terraced house which had been converted into a surgery. The spring sunshine still had to pass through a stained-glass panel on the front door and it threw warm gules like bloodstains on to the cracked tiled floor.

There were three of them in the practice: MacCrystal, the senior partner, so senior he was almost invisible; Ms Lacewing, early twenties, newly qualified, an advanced thinker; and Shorter himself. He was in his late thirties but it didn’t show except at the neck. His hair was thick and black and he was as lean and muscular as a fit twenty-year-old. Pascoe who was a handful of years younger indulged his resentment at the other man’s youthfulness by never mentioning it. Over the long period during which he had been a patient, a pleasant first name relationship had developed between the men. They had shared their fantasy fears about each other’s professions and Pascoe’s revelation of his Gestapo-torture confessions under the drill had given them a running joke, though it had not yet run them closer together than sharing a table if they met in a pub or restaurant.

Perhaps, thought Pascoe as he watched Shorter pouring a stiff gin and tonic, perhaps he’s going to invite me and Ellie to his twenty-first party. Or sell us a ticket to the dentists’ ball. Or ask me to fix a parking ticket.

And then the afterthought: what a lovely friend I make!

He took his drink and waited before sipping it, as though that would commit him to something.

‘You ever go to see blue films?’ asked Shorter.

‘Ah,’ said Pascoe, taken aback. ‘Yes. I’ve seen some. But officially.’

‘What? Oh, I get you. No, I don’t mean the real hard porn stuff that breaks the law. Above the counter porn’s what I mean. Rugby club night out stuff.’

‘The Naughty Vicar of Wakefield. That kind of thing?’

‘That’s it, sort of.’

‘No, I can’t say I’m an enthusiast. My wife’s always moaning they seem to show nothing else nowadays. Stops her going to see the good cultural stuff like Deep Throat.’

‘I know. Well, I’m not an enthusiast either, you understand, but the other night, well, I was having a drink with a couple of friends and one of them’s a member of the Calliope Club …’

‘Hang on,’ said Pascoe, frowning. ‘I know the Calli. That’s not quite the same as your local Gaumont, is it? You’ve got to be a member and they show stuff there which is a bit more controversial than your Naughty Vicars or your Danish Dentists. Sorry!’

‘Yes,’ agreed Shorter. ‘But it’s legal, isn’t it?’

‘Oh yes. As long as they don’t overstep the mark. But without knowing what you’re going to tell me, Jack, you ought to know there’s a lot of pressure to close the place. Well, you will know that anyway if you read the local rag. So have a think before you tell me anything that could involve your mates or even you.’

Which just about defines the bounds of our friendship, thought Pascoe. Someone who was closer, I might listen to and keep it to myself; someone not so close, I’d listen and act. Shorter gets the warning. So now it’s up to him.

‘No,’ said Shorter. ‘It’s nothing to do with the Club or its members, not really. Look, we went along to the show. There were two films, one a straightforward orgy job and the other, well, it was one of these sex and violence things. Droit de Seigneur they called it. Nice simple story line. Beautiful girl kidnapped on wedding night by local loony squire. Lots of nasty things done to her in a dungeon, ending with her being beaten almost to death just before hubbie arrives with rescue party. The squire then gets a taste of his own medicine. Happy ending.’

‘Nice,’ said Pascoe. ‘Then it’s off for a curry and chips?’

‘Something like that. Only, well, it’s daft, and I hardly like to bother anyone. But it’s been bothering me.’

Pascoe looked at his watch again and finished his drink.

‘You think it went too far?’ he said. ‘One for the vice squad. Well, I’ll mention it, Jack. Thanks for the drink, and the tooth.’

‘No,’ said Shorter. ‘I’ve seen worse. Only in this one, I think the girl really did get beaten up.’

‘I’m sorry?’

‘In the dungeon. The squire goes berserk. He’s got these metal gauntlets on, from a suit of armour. And a helmet too. Nothing else. It was quite funny for a bit. Then he starts beating her. I forget the exact sequence but in the end it goes into slow motion; they always do, this fist hammers into her face, her mouth’s open – she’s screaming, naturally – and you see her teeth break. One thing I know about is teeth. I could swear those teeth really did break.’

‘Good God!’ said Pascoe. ‘I’d better have another of these. You’re saying that … I mean, for God’s sake, a mailed fist! How’d she look at the end of the film? I’ve heard that the show must go on, but this is ridiculous!’

‘She looked fine,’ said Shorter. ‘But they don’t need to take the shots in the order you see them, do they?’

‘Just testing you,’ said Pascoe. ‘But you must admit it seems daft! I mean, you’ve no doubt the rest of the nastiness was all faked?’

‘Not much. Not that they don’t do sword wounds and whip lashes very well. But I’ve never seen a real sword wound or whip lash! Teeth I know. Let me explain. The usual thing in a film would be, someone flings a punch to the jaw, head jerks back, punch misses of course, on the sound track someone hammers a mallet into a cabbage, the guy on the screen spits out a mouthful of plastic teeth, shakes his head, and wades back into the fight.’

‘And that’s unrealistic?’

‘I’ll say,’ said Shorter. ‘With a bare fist it’s unrealistic, with a metal glove it’s impossible. No, what would really happen would be dislocation, probably fracture of the jaw. The lips and cheeks would splatter and the teeth be pushed through. A fine haze of blood and saliva would issue from the mouth and nose. You could mock it up, I suppose, but you’d need an actress with a double-jointed face.’

‘And this is what you say happened in this film.’

‘It was a flash,’ said Shorter. ‘Just a couple of seconds.’

‘Anybody else say anything?’

‘No,’ admitted Shorter. ‘Not that I heard.’

‘I see,’ said Pascoe, frowning. ‘Now, why are you telling me this?’

‘Why?’ Shorter sounded surprised. ‘Isn’t it obvious? Look, as far as I’m concerned they can mock up anything they like in the film studios. If they can find an audience, let them have it. I’ll watch cowboys being shot and nuns being raped, and rubber sharks biting off rubber legs, and I’ll blame only myself for paying the ticket money. No, I’ll go further though I know our Ms Lacewing would pump my balls full of novocaine if she could hear me! It doesn’t all have to be fake. If some poor scrubber finds the best way to pay the rent is to let herself be screwed in front of the cameras, then I won’t lose much sleep over that. But this was something else. This was assault. In fact the way her head jerked sideways, I wouldn’t be surprised if it ended up as murder.’

‘Well, there’s a thing,’ murmured Pascoe. ‘Would you stake your professional reputation?’

Shorter, who had been looking very serious, suddenly grinned.

‘Not me,’ he said. ‘I really was convinced that John Wayne died at the Alamo, But it’s bothered me a bit. And you’re the only detective-inspector I know, so now it can bother you while I get back to teeth.’

‘Not mine,’ said Pascoe smugly. ‘Not for six months.’

‘That’s right. But don’t forget you’re due to have the barnacles scraped off. Monday, I think. I’ve fixed you up with our Ms Lacewing. She’s a specialist in hygiene, would you believe?’

‘I also gather that she too doesn’t care what goes on at the Calliope Kinema Club,’ said Pascoe.

‘What? Oh, of course, you’d know about that. The picketing, you mean. She’s tried to get my wife interested in that lot but no joy there, I’m glad to say. No, if I were you I’d keep off the Calli while she’s got you in the chair. On the other hand I’m sure she’d be fascinated by any plans Bevin might have for harnessing female labour in the war effort.’

‘Shorter,’ said Detective-Superintendent Andrew Dalziel reflectively. ‘Does your fillings in a shabby mac and a big hat, does he?’

‘Pardon?’ said Pascoe.

‘The blue film brigade,’ said Dalziel, scratching his gut.

‘I managed to grasp the reference to the shabby mac,’ said Pascoe.

‘Clever boy. Well, they need the big hats to hold on their laps.’

‘Ah,’ said Pascoe.

‘Of course it’s a dead giveaway when they stand up. Jesus, my guts are bad!’

Scatophagous crapulence, diagnosed Pascoe, but he kept an expression of studied indifference on his face. On his bad days Dalziel was quite unpredictable and it was hard for his inferiors to steer a path between overt and silent insolence.

‘I reckon it’s an ulcer,’ said Dalziel. ‘It’s this bloody diet. I’m starving the thing and it’s fighting back.’

He thumped his paunch viciously. There was certainly less of it than there had been a couple of years earlier when the diet had first begun. But the path of righteousness is steep and there had been much backsliding and strait is the gate and it would still be a tight squeeze for Dalziel to get through.

‘Shorter,’ reminded Pascoe. ‘My dentist.’

‘Not one for us. Mention it to Sergeant Wield, though. How’s he shaping?’

‘All right, I think.’

‘Shown his face at the Calli, has he? That’s why I picked him, that face. He’ll never be a master of disguise, but, Christ, he’ll frighten the horses!’

This was a reference to (a) Sergeant Wield’s startling ugliness and (b) the Superintendent’s subtle tactic for satisfying both parties to a complaint. The Calliope Kinema Club had opened eighteen months earlier and after an uneasy period as a sort of art house it had finally settled for a level of cine-porn a couple of steps beyond what was available at Gaumonts, ABCs and on children’s television. All might have been well had the Calli known its place, wherever that was. But wherever it was, it certainly wasn’t in Wilkinson Square. Unlike most centrally situated monuments to the Regency, Wilkinson Square had not relaxed and enjoyed the rape of developers and commerce. Even the subtler advances of doctors’ surgeries, solicitors’ chambers and civil servants’ offices had been resisted. It was true that some of the larger houses had become flats and one had even been turned into a private school which for smartness of uniform and eccentricity of curriculum was not easily matched, but a large proportion of the fifteen houses which comprised the Square remained in private occupation. Even the school was forgiven as a necessary antidote to the creeping greyness of post-war education based on proletarian envy and Marxist subversion. No parent of sense with a lad aged six to eleven could be blamed for supporting this symbol of a nation’s freedoms, whatever the price. The price included learning to add in pounds, shillings and pence and being subjected to Dr Haggard’s interesting theories on corporal punishment, but it was little to pay for the social kudos of having a Wilkinson House certificate.

What inefficiency and paedophobia could not achieve, inflation and a broken economy did, and in the mid-seventies so many parents had a change of educational conscience that the school finally closed. The inhabitants of Wilkinson Square watched the house with interest and suspicion. The best they could hope for was expensive flats, the worst they feared was NALGO offices.

The Calliope Kinema Club was a shattering blow cushioned only by the initial incredulity of those receiving it. That such a coup could have taken place unnoticed was shock enough; that Dr Haggard could have been party to it defied belief. But it had and he was. His master stroke had been to change the postal address of the building. Wilkinson House occupied a corner site and one side of the house abutted on Upper Maltgate, a busy and noisy commercial thoroughfare. Here, down a steep flight of steps and across a gloomy area, was situated the old tradesman’s entrance through which postal and most other deliveries were still made. Dr Haggard requested that his house be henceforth known as 21A Upper Maltgate. There was no difficulty, and it was as 21A Upper Maltgate that the premises were licensed to be used as a cinema club while the vigilantes of the Square slept and never felt their security being undone.

But once awoken, their wrath was great. And once the nature of the entertainments being offered at the Club became clear, they launched an attack whose opening barrage in the local paper was couched in such terms that applications for membership doubled the following week.

Legally the Club was in a highly defensible position. The building satisfied all the safety regulations and the Local Authority had issued a licence permitting films to be shown on the premises. The films did not need to be certificated for public showing, though many of them were, and even those such as Droit de Seigneur which were not had so ambiguous a status under current interpretation of the obscenity laws that a successful prosecution was most unlikely.

In any case, as the Wilkinson Square vigilantes bitterly pointed out, Haggard clearly had strong support in high places and they had to content themselves with appealing against the rates and ringing the police whenever a car door slammed. Most of them hadn’t known whether to raise a radical cheer or a reactionary eyebrow when WRAG, the Women’s Rights Action Group, had joined the fray. Sergeant Wield, who had been given the job of looking into complaints from both sides, was summoned by Haggard and later three members of WRAG, including Ms Lacewing, Jack Shorter’s partner, were fined for obstructing the police in the execution, etc. This confirmed the vigilantes’ instinct that the rights of women and the rights of property owners had nothing in common and a potentially powerful alliance never materialized. But the pressures remained strong enough for Sergeant Wield to be currently engaged in preparing a full report on the Calli and all complaints against it. Pascoe felt a little piqued that his own contribution was being so slightingly dismissed.

‘So I just ignore Shorter’s information?’ he said.

‘What information? He thinks some French bird got her teeth bust in a picture? I’ll ring the Sûreté if you like. No, the only thing interests me about Mr Shorter is he likes dirty films.’

‘Oh come on!’ said Pascoe. ‘He went along with a friend. Where’s the harm? As long as it doesn’t break the law, what’s wrong with a bit of titillation?’

‘Titillation,’ repeated Dalziel, enjoying the word. ‘There’s some jobs shouldn’t need it. Doctors, dentists, scout-masters, vicars – when any of that lot start needing titillation, watch out for trouble.’

‘And policemen?’

Dalziel bellowed a laugh.

‘That’s all right. Didn’t you know we’d been made immune by Act of Parliament? They’ve got a council, these dentists? No doubt they’ll sort him out if he starts bothering his patients. I’d keep off the gas if I were you.’

‘He’s a married man,’ protested Pascoe, though he knew silence was a marginally better policy.

‘So are wife-beaters,’ said Dalziel. ‘Talking of which, how’s yours?’

‘Fine, fine,’ said Pascoe.

‘Good. Still trying to talk you out of the force?’

‘Still trying to keep me sane within it,’ said Pascoe.

‘It’s too bloody late for most of us,’ said Dalziel. ‘I get down on my knees most nights and say, “Thank you, Lord, for another terrible day, and stuff Sir Robert.”’

‘Mark?’ said Pascoe, puzzled.

‘Peel,’ said Dalziel.

Chapter 2 (#ulink_edad27ed-c87d-568b-a944-560b37aca95f)

Pascoe was surprised at the range of feelings his visit to the Calliope Kinema Club put him through.

He felt furtive, angry, embarrassed, outraged, and, he had to confess, titillated. He was so immersed in self-analysis that he almost missed the teeth scene. It was the full frontal of a potbellied man wearing only a helmet and gauntlets that triggered his attention. There was a lot of screaming and scrabbling, all rather jolly in a ghastly kind of way, then suddenly there it was; the mailed fist slamming into the screaming mouth, the girl’s face momentarily folding like an empty paper bag, then her naked body falling away from the camera with the slackness of a heavyweight who has run into one punch too many. Cut to the villain, towering in every sense, with sword raised for the coup de grâce, then the door bursts open and enter the hero, by some strange quirk also naked and clearly a match for tin-head. The girl, very bloody but no longer bowed, rises to greet him, and the rest is retribution.

When the lights were switched on Pascoe, who had arrived in the dark, looked around and was relieved to see not a single large hat. The audience numbered about fifty, almost filling the room, and were of all ages and both sexes, though men predominated. He recognized several faces and was in turn recognized. There would be some speculation whether his visit was official or personal, he guessed, and he did not follow the others out of the viewing room but sat and waited till word should reach Dr Haggard.

It didn’t take long.

‘Inspector Pascoe! I didn’t realize you were a member.’

He was a tall, broad-shouldered man with a powerful head. His hair was touched with grey, his eyes deep set in a noble forehead, his rather overfull lips arranged in an ironic smile. Only a pugilist twist of the nose broke the fine Roman symmetry of that face. In short, it seemed to Pascoe to display those qualities of authoritarian, intellectual, sensuous brutality which were once universally acknowledged as the cardinal humours of a good headmaster.

‘Dr Haggard? I didn’t realize we were acquainted.’

‘Nor I. Did you enjoy the show?’

‘In parts.’

‘Parts are what it’s all about,’ murmured Haggard. ‘Tell me, are you here in any kind of official capacity?’

‘Why do you ask?’ said Pascoe.

‘Simply to help me decide where to offer you a drink. Our members usually foregather in what used to be the staff room to discuss the evening’s entertainment.’

‘I think I’d rather talk in private,’ said Pascoe.

‘So it is official.’

‘In part,’ said Pascoe, conscious that this was indeed only a very small part of the truth. Shorter’s story had interested him, Dalziel’s lack of interest the previous day had piqued him, Ellie was representing her union at a meeting that night, television was lousy on Thursdays, and Sergeant Wield had been very happy to supply him with a membership card.

‘Then let us drink in my quarters.’

They went out of the viewing room, which Pascoe guessed had once been two rooms joined together to make a small school assembly hall, and climbed the stairs. Sounds of conversation and glasses as from a saloon bar followed them upstairs from one of the ground-floor rooms. The Wilkinson Square vigilantes had made great play of drunkards falling noisily out of the Club late at night and then falling noisily into their cars, which were parked in a most inconsiderate manner all round the Square. Wield had found no evidence to support these assertions.

Haggard did not pause on the first-floor landing but proceeded up the now somewhat narrower staircase. Observing Pascoe hesitate, he explained, ‘Mainly classrooms here. Used for storage now. I suppose I could domesticate them again but I’ve got so comfortably settled aloft that it doesn’t seem worth it. Do come in. Have a seat while I pour you something. Scotch all right?’

‘Great,’ said Pascoe. He didn’t sit down immediately but strolled around the room, hoping he didn’t look too like a policeman but not caring all that much if he did. Haggard was right. He was very comfortable. Was the room rather too self-consciously a gentleman’s study? The rows of leather-bound volumes, the huge Victorian desk, the miniatures on the wall, the elegant chesterfield, the display cabinet full of snuff-boxes, these things must have impressed socially aspiring parents.

I wonder, mused Pascoe, pausing before the cabinet, how they impress the paying customer now.

‘Are you a collector?’ asked Haggard, handing him a glass.

‘Just an admirer of other people’s collections,’ said Pascoe.

‘An essential part of the cycle,’ said Haggard. ‘This might interest you.’

He reached in and picked up a hexagonal enamelled box with the design of a hanging man on the lid.

‘One of your illustrious predecessors. Jonathan Wild, Thief-taker, himself taken and hanged in 1725. Such commemorative design is quite commonplace on snuffboxes.’

‘Like ashtrays from Blackpool,’ said Pascoe.

‘Droll,’ said Haggard, replacing the box and taking out another, an ornate silver affair heavily embossed with a coat of arms.

‘Mid-European,’ said Haggard. ‘And beautifully airtight. This is the one I actually keep snuff in. Do you take it?’

‘Not if I can help it.’

‘Perhaps you’re wise. In the Middle Ages they thought that sneezing could put your soul within reach of the devil. I should hate you to lose your soul for a pinch of snuff, Inspector.’

‘You seem willing to take the risk.’

‘I take it to clear my head,’ smiled Haggard. ‘Perhaps I should take some now before you start asking your questions. I presume you have some query concerning the Club?’

‘In a way. It’s a bit different from teaching, isn’t it?’ said Pascoe, sitting down.

‘Is it? Oh, I don’t know. It’s all educational, don’t you think?’

‘Not a word some people would find it easy to apply to what goes on here, Dr Haggard,’ said Pascoe.

‘Not a word many people find it easy to apply to much of what goes on in schools today, Inspector.’

‘Still, for all that …’ tempted Pascoe.

Haggard regarded him very magisterially.

‘My dear fellow,’ he said. ‘When we’re much better acquainted, and you have proved to have a more than professionally sympathetic ear, and I have been mellowed by food, wine and a good cigar, then perhaps I may invite you to contemplate the strange flutterings of my psyche from one human vanity to another. Should the time arrive, I shall let you know. Meanwhile, let’s stick with your presence here tonight. Have my neighbours undergone a new bout of hysteria?’

‘Not that I know of,’ said Pascoe. ‘No, it’s about one of your films. One I saw tonight. Droit de Seigneur.’

‘Ah yes. The costume drama.’

‘Costume!’ said Pascoe.

‘Did the nudity bother you?’ said Haggard anxiously.

‘I don’t think so. Anyway it was the assault scene I wanted to talk about, where the girl gets beaten up.’

‘You found it too violent? I’m astounded.’

‘The scene was brought to my attention …’

‘By whom?’ interrupted Haggard. ‘Has he not seen A Clockwork Orange? The Exorcist? Match of the Day?’

‘I would like you to be serious, Dr Haggard,’ said Pascoe reprovingly. ‘What do you know about the making of these films?’

‘In general terms, very little. You probably know more yourself. I’m sure the diligent Sergeant Wield does. I am merely a showman.’

‘Of course. Look, Dr Haggard, I wonder if it would be possible to see part of that film again. It’ll help me explain what I’m doing here.’

Haggard finished his drink, then nodded.

‘Why not? I’m intrigued. You could always gatecrash again, of course, but I suppose that might compromise your reputation. Besides, we only have that film until the weekend, so let’s see what we can do.’

Downstairs again, Haggard left Pascoe in the viewing room and disappeared for a few moments, returning with a small triangular-faced man with large hairy-knuckled hands, one of which was wrapped round a pint tankard.

‘Maurice, this is Inspector Pascoe. Maurice Arany, my partner and also, thank God, my projectionist. I am mechanically illiterate.’

They shook hands. It would have been easy, thought Pascoe, to develop it into a test of strength, but such games were not yet necessary.

As well as he could he described the sequence he wished to see, and Arany went out. Haggard switched off the lights and they sat together in the darkness till the screen lit up. Arany hit the spot with great precision and Pascoe let it run until the entry of the vengeful husband.

‘That’s fine,’ he said and Haggard interposed his arm into the beam of light and the picture flickered and died.

‘Well, Inspector?’ said Haggard after he had switched on the lights.

‘My informant reckons that was for real,’ said Pascoe diffidently.

‘All of it?’ said Haggard.

‘The punch that knocks the girl down.’

‘How extraordinary. Shall we look again? Maurice!’

They sat through the sequence once more.

‘It’s quite effective, though I’ve seen better,’ said Haggard. ‘But on what grounds would you claim it was real, if by real you mean that some unfortunate girl really did get punched?’

‘I don’t know,’ admitted Pascoe. ‘It has a quality … I’ve seen a few fights, and that kind of …’

He tailed off, uncertain if he was speaking from even the narrowest basis of conviction. If he had seen the film without Shorter’s comments in his mind, would he have paid any special attention to the sequence? Presumably hundreds of people (thousands?) had sat through it without unsuspending their disbelief.

‘I’ve seen people burnt alive, decapitated, disembowelled and operated on for appendicitis, all I hasten to add in the commercial cinema,’ said Haggard. ‘So far as my own limited experience of such matters permitted me to judge, I was completely convinced of the verisimilitude of these scenes. I shouldn’t have thought dislodging a few teeth was going to present the modern director with many problems.’

‘No,’ said Pascoe. He was beginning to feel a little foolish, but under Dalziel’s tutelage he had come to ignore such social warning cones.

‘Can I see the titles, please?’ asked Pascoe.

Haggard addressed Maurice Arany again and as the titles rolled, Pascoe made notes. There wasn’t a great deal of information. It was produced by a company called Homeric Films and written and directed by one Gerry Toms.

‘A name to conjure with,’ said Pascoe.

‘It must be his own,’ agreed Haggard.

‘You don’t know where this company is located, do you?’

‘It’s a mushroom industry,’ said Haggard. ‘It probably no longer exists.’

‘But there have been other films from the same people?’

Haggard admitted there had.

‘Perhaps your distributor could help.’

‘I wouldn’t bank on it, but you’re welcome to the address.’

Upon this co-operative note, they parted. Pascoe sat in his car in the Square for some time until other members of the audience began to leave. There were no overt signs of drunkenness, no undue noise in the way they entered and started their cars, and certainly no suggestion that anyone was about to roam around the Square all night in search of some luckless resident to assault and ravish.

When he got home, Ellie was sitting in front of the television eating a dripping sandwich.

‘Good meeting?’ he asked.

‘Useless,’ she said. ‘Why don’t you declare a police state and shoot the bastards? You know what they said? Higher education might be a luxury this authority could no longer afford!’

‘Quite right,’ he said, regarding her affectionately. She was worth his regard. Friends at university, they had met again during an investigation at Holm Coultram College where Ellie was a lecturer. After some preliminary skirmishing they had become lovers and then, the previous year, got married. It was not an easy marriage, but nothing worthwhile ever was, thought Pascoe with a swift descent into Reader’s Digest philosophy.

‘You know who they’ve brought in to chair our liaison committee? Godfrey bloody Blengdale, that’s who.’

‘Is that bad?’ asked Pascoe, yawning. He sat down on the sofa next to Ellie, took a bite of her sandwich and focused on the television screen.

‘It’s sinister,’ said Ellie, frowning. ‘He’s the right-wing hatchet man on that council. I’ve never really believed there was a chance they could seriously consider closing the college down, but now … shall I switch this off?’

‘No,’ said Pascoe, watching with interest as James Cagney prepared to sort out a guy twice his size. ‘I may learn something.’

‘About dealing with suspects?’

‘About dealing with women. Is this the one where he pushes the grapefruit in whatsername’s face?’

‘I don’t know. I haven’t really been watching. It’s just been something to take my mind off those pompous bastards. Where’ve you been anyway? Boozing with Yorkshire’s Maigret?’

‘No. I’ve been to the pictures which is what makes this so nice.’

Briefly he explained. Ellie listened intently. He didn’t often discuss the detail of his work with her but this wasn’t a case, just a speculation, and Pascoe who would have welcomed her clarity of thought on many occasions was glad to invite it now.

To his surprise like Dalziel she dismissed as irrelevant the question of the broken teeth.

‘It’s not very likely, is it?’ she said. ‘It’s this chap Haggard you want to be interested in. I’ve heard of him. Before his school folded, he was a thorn in everyone’s side. No official standing, of course, and he had ideas that made the Black Papers shine at night. But he knew how to get to people, push them around.’

‘He obviously hasn’t lost his charming ways,’ said Pascoe. ‘The neighbours are almost solidly against him, but it’s getting them nowhere.’

‘So you have a complaint to investigate? Great! Can’t you fit him up? Slip a brick in his pocket or something?’

Pascoe sighed. Ellie made police jokes like some people make Irish jokes, and at times they began to wear a bit thin.

‘It’s nothing to do with me. Sergeant Wield’s looking after things there. I’m only here for the teeth.’

‘So you say. Sounds odd to me. And this dentist of yours, he sounds a bit odd too.’

‘Christ,’ said Pascoe. ‘You sound more like Dalziel every day.’

He bit into Ellie’s dripping sandwich again and watched James Cagney bust someone right on the jaw. The recipient of the blow staggered back, shook his head admiringly, then launched a counter-attack.

This, thought Pascoe, is what fighting ought to look like. When the Gerry Toms of this world could produce stuff like this, then they might climb out of the skin-flick morass. This appealed to man’s artistic sense, not his basic lusts.

Guns had appeared now. Cagney dived for cover and came up with a huge automatic in his hand.

‘Great,’ said Pascoe, his artistic sense thoroughly appealed to. ‘Now kill the bastard!’

Chapter 3 (#ulink_1e400cc7-810c-53a4-b467-dbf483a202a7)

Sergeant Wield’s ugliness was only skin deep, but that was deep enough. Each individual feature was only slightly battered, or bent, or scarred, and might have made a significant contribution to the appeal of any joli-laid hero from Mr Rochester on, but combined in one face they produced an effect so startling that Pascoe who met him almost daily was still amazed when he entered his room.

‘Thanks for the membership card,’ said Pascoe, tossing it on the desk. ‘Maurice Arany, what do you know about him?’

‘Hungarian,’ said Wield. ‘His parents brought him out with them in ’fifty-six. He was thirteen then. They settled in Leeds and Maurice started work in a garage a couple of years later. He has no formal qualifications but a lot of mechanical skill. He got interested in the clubs and for a while he tried pushing an act around, part time. Bit of singing, juggling, telling jokes. Trouble was he couldn’t sing and his jokes never quite made it. Arany spoke near perfect English, but he couldn’t quite grasp the subtleties of our four-letter words. So he jacked it in and got involved in other ways, lighting and sound to start with, but eventually a bit of dealing, a bit of management.’

‘Who’d he manage?’

‘Exotic dancers mainly. No, it wasn’t like that. Most of these girls have mum to mind them, so there’s no room for a ponce. Arany just smoothed the way, made contacts, arranged bookings. Now he’s got his own agency. Small, just an office and a secretary, but he does a lot of business.’

‘And how’d he get involved with Haggard?’

Wield shrugged.

‘God knows. He just appeared, as far as I can make out. There’s no trace of a previous connection, but then we never had any cause to keep a close watch on either of these two.’

‘Kept his nose clean, has he?’

‘Oh yes. Everyone keeps a bit of an eye on the club circuit, that’s how we know as much as we do about him, but he’s never been on the books.’

‘Clever or clean,’ said Pascoe. ‘How’s it going anyway, Sergeant?’

‘Slowly and nowhere. No one’s breaking the law and there isn’t any public nuisance to speak of. I don’t know why we bother! But Mr Dalziel says to keep at it, so keep at it I will! You didn’t get anything, did you, sir?’

He spoke with a kind of reproachful neutrality. Pascoe had offered only the most perfunctory of explanations for his visit to the Calliope Club. He had passed on Shorter’s comments on Droit de Seigneur, of course, but the sergeant obviously suspected that there was some other motive for his interest. Was there? wondered Pascoe. All he could think of was obstinacy, because everyone else seemed to be so dismissive of the dentist’s claim, but he was not by nature an obstinate man. On the other hand here he was with enough work to keep two MPs, or six shop stewards, or a dozen teachers, or twenty pop-groups, or a hundred members of the Jockey Club, or a thousand princesses, going for a year and he was reaching for the phone and ringing Ace-High Distributors Inc. of Stretford, Manchester.

A girl answered. Quickly assessing that the word ‘police’ was more likely to inhibit than expedite information, he put on his best posh voice, said he was trying to contact dear old Gerry Toms, last heard of directing some masterpiece for Homeric Films, and could she help? She could. He noted the address with surprise, said thank you kindly, and replaced the receiver.

‘Mike Yarwood beware,’ said Dalziel from the doorway. ‘There’s laws against personation, you know that? Sergeant Wield tells me you went to the pictures last night. Asked a few questions I dare say?’

Pascoe nodded, feeling like a small boy caught trespassing.

‘Jesus wept,’ sighed Dalziel. ‘What do I have to say to get through to you, Peter? You must be bloody slack at the moment, that’s all I can say. Well, we’ll soon put that right. My office, five minutes.’

He left and Pascoe resumed his feeling of surprise that such a respectable place as Harrogate should house such a prima facie disreputable company as Homeric Films.

At least it was relatively handy.

He dialled again.

Another girl. This time he put on his official voice and asked to speak to the man in charge.

After a pause, another female voice said, ‘Hello. Can I help?’

‘I asked for the man in charge,’ said Pascoe coolly.

‘Did you indeed?’ said the woman in sympathetic motherly tones. ‘Were you perhaps shell-shocked in the First World War? They let us women out of the kitchen now, you know, and we’ve even got laws to prove it.’

‘I’m sorry,’ said Pascoe. ‘You mean you’re in charge?’

‘You’d better believe it. Penelope Latimer. Who’re you?’

‘I’m sorry, Miss Latimer. My name’s Pascoe; I’m a Detective-Inspector with Mid-Yorkshire CID.’

‘Congratulations. Forget my shell-shock crack. You’ve just explained yourself. What can I do for you, Detective-Inspector?’

She sounded amused rather than concerned, thought Pascoe. But then why should she be concerned? Perhaps I just want people to be concerned when I give them a quick flash of my constabulary credentials.

‘Your company produced a film called Droit de Seigneur, I believe.’

‘Yes.’ More cautious now?

‘I’m interested in talking with the director, Mr Toms, and I wondered if you could help?’

‘Gerry? How urgent do you want him?’

‘It’s not desperate,’ said Pascoe. ‘Why?’

‘He’s in Spain just now, that’s why. If you want him urgent, I can give you his hotel. We’re expecting him back on Friday, though.’

‘Oh, that’ll do,’ said Pascoe. ‘You say you’re expecting him back. That means he’s still working for Homeric?’

‘He better had be,’ said Penelope Latimer. ‘He owns a third of the company.’

‘Really? And he wrote and directed the film?’

‘You’ve seen it? Yes, he wrote it, not very taxing on the intellect though, you agree? What’s with this film anyway? Some local lilywhite giving trouble?’

Pascoe hesitated only a moment. She sounded cooperative and bright. At the worst he might pick something up from her reaction.

He told her Shorter’s theory.

Her reaction was an outpouring of pleasantly gurgly laughter.

‘I’m sorry,’ he said. ‘I didn’t catch that.’

‘Funny,’ she said. ‘You think we pay actresses to get beaten up? Who can afford that kind of money?’

‘If you beat them up enough, I suppose they come cheap,’ said Pascoe with great acidity, tired of being made to feel foolish.

‘Oh-ho! Snuff-films we’re making now? When can we expect you and the dogs?’

‘I’m not with you,’ said Pascoe. ‘What was that you said! Snuff-films?’

‘I thought the police knew everything. It’s when someone really does get killed in front of the camera. They snuff it – get it?’

‘And these exist?’

‘So they say. I mean, who wants to find out? Look, you’re worried about the leading lady being duffed up, right? So if you could have a little chat with her, you’d be happy? All right. I’ll dig out her address on one condition. You see her, ask about the film, nothing more. No follow up just to make your bother worthwhile.’

‘You’ve lost me again,’ said Pascoe.

‘Do I have to spell it out? This is lower division stuff. I mean it won’t be Julie Andrews you’re going to talk to. This girl might – I don’t say she is, but she might be on the game. Or she might have a bit of weed about the place. Or anything. Now I don’t want to sick the police on her. So I want your word. No harassment.’

‘How do you know you can trust me?’ asked Pascoe.

‘For a start you wouldn’t be pussyfooting around about promising if it didn’t mean anything,’ she answered.

‘A psychologist already,’ mocked Pascoe. ‘All right. I promise. But all bets off if she’s just stuck a knife into her boy-friend or robbed a bank. OK?’

‘Now we’re talking about crimes,’ said Penelope Latimer. ‘Hold on.’

While he waited Pascoe picked up his internal phone and got through to Wield.

‘You ever heard of something called a snuff-film?’ he asked.

‘Yes,’ said Wield.

‘Don’t keep it to yourself, Sergeant,’ said Pascoe in his best Dalziel manner.

‘In the States mainly,’ said Wield. ‘Though there are rumours on the Continent. No one’s ever picked one up as far as I know, so obviously there’s no prosecution recorded yet.’

‘Yes, but what are they?’

‘What they’re said to be is films made of someone dying. Usually some tart from, say, one of the big South American sea ports who no one’s going to miss in a hurry. She thinks it’s a straightforward skin-flick. By the time she finds out wrong, it’s too late. The scareder she gets, the more she tries to run, the better the picture.’

‘Better! Who for?’

‘For the bent bastards who want to see ’em. And for the guys who make the charge.’

‘Jesus!’

‘Hello? You there?’ said the woman’s voice from the other phone.

‘Thanks, Sergeant,’ said Pascoe. ‘Yes, Miss Latimer?’

‘It’s Linda Abbott. Address is 25 Hampole Lane, Borage Hill. That’s a big new estate about twelve miles south of here, just north of Leeds.’

‘Local, eh?’

‘What do you think, we fetch them from Hollywood?’

‘No, but I reckoned you might cast your net as far as South Shields, say, or Scunthorpe.’

Penelope Latimer chuckled.

‘Come up and see us some time, Inspector,’ she said throatily. ‘’Bye.’

‘I might, I might,’ said Pascoe to the dead phone. But he doubted if he would. Harrogate, Leeds, they were off his patch and Dalziel didn’t sound as if he was about to let him go drifting west on a wild goose chase. No, he’d have to get someone local to check that this woman, Linda Abbott, had all her teeth. On the other hand, he’d promised Penelope Latimer that he’d handle it with tact. What he needed was an excuse to find himself in the area.

The phone rang.

‘Have you got paralysis?’ bellowed Dalziel.

Thirty seconds later he was in the fat man’s office.

‘There’s a meeting this afternoon. Inter-divisional liaison. Waste of fucking time so I’ve told ’em I can’t go, but I’ll send a boy to observe.’

‘And you want me to suggest a boy?’ said Pascoe brightly.

‘Funny. It’s four-thirty. Watch the bastards. Some of them are right sneaky.’

‘One thing,’ said Pascoe. ‘Where is it?’

‘Do I have to tell you everything?’ groaned Dalziel. ‘Harrogate.’

Chapter 4 (#u6c4fab43-6061-549e-8da1-3cc3e619d8e2)

Pascoe had no direct experience of the polygamous East, but he supposed that, with arranged marriages thrown in, it was possible for a man to know a woman only in her wedding dress and total nudity. But would he recognize her if he met her in the street? Pascoe doubted it. He regarded the gaggle of women hanging around outside the school gates and mentally coated each in turn with blood. It didn’t help.

He’d come to see Linda Abbott hoping that the law-breaking forecast by Penny Latimer would not be too blatant. Now he wished that he’d found the woman leaning against a lamp post smoking a reefer and making obscene suggestions to passersby. Instead he’d found himself at the front door of a neat little semi, talking to an angry Mr Abbott who had been roused from the sleep of the just and the night-shift worker by Pascoe’s policeman’s thumb on the bell push.

Having mentally prepared himself to turn a blind eye to Mrs Abbott’s misdemeanours, Pascoe now became the guardian of her reputation and pretended to be in washing-machines. Mrs Abbott, he learned, had a washing-machine, didn’t want another, wasn’t about to get another, and cared perhaps even less than Mr Abbott to deal with poofy commercials at the door. But he also learned that Mrs Abbott had gone down to the school to collect her daughter and, having noticed what he took to be the school two streets away, Pascoe had made his way there to intercept.

He spotted Linda Abbott as the mums began to break off, clutching their spoil. A bold face, heavily made up; a wide loud mouth remonstrating with her small girl for some damage she’d done to her person or clothes. The camera didn’t lie after all.

‘Mrs Abbott?’ said Pascoe. ‘Could I have a word with you?’

‘As many as you like, love,’ said the woman, looking him up and down. ‘Only, my name’s Mackenzie. Yon’s Mrs Abbott, her with the little blonde lass.’

Mrs Abbott was dumpy, untidy and plain. Her daughter on the other hand was a beauty. Another ten years if she maintained her present progress and … I’ll probably be too old to care, thought Pascoe.

‘Mrs Abbott,’ he tried again. ‘Could I have a word?’

‘Yes?’

‘Mam, is this one of them funny buggers?’ asked the angelic six-year-old.

‘Shut up, our Lorraine,’ said Mrs Abbott.

‘Funny …?’ said Pascoe.

‘I tell her not to talk with strangers,’ explained Mrs Abbott.

‘’Cos there’s a lot of funny buggers about,’ completed Lorraine happily.

‘Well, I’m not one of them,’ said Pascoe. ‘I hope.’

He showed his warrant card, taking care to keep it masked from the few remaining mums.

‘You might well hope,’ said Mrs Abbott. ‘What’s up?’

‘May I walk along with you?’ he asked.

‘It’s a free street. Lorraine, don’t you run on the road now!’

‘It’s about a film you made,’ said Pascoe. ‘Droit de Seigneur.’

‘Oh aye. Which was that one?’

‘Can’t you remember?’

‘They don’t often have titles when we’re making them, not real titles, any road.’

Briefly Pascoe outlined the plot.

‘Oh, that one,’ said Mrs Abbott. ‘What’s up?’

‘It’s been suggested,’ said Pascoe, ‘that undue violence may have been used in some scenes.’

‘What?’

‘Especially in the scene where the squire beats you up, just before the US cavalry arrive.’

‘You sure you’re not mixing it up with the Big Big Horn?’ said Mrs Abbott.

‘I don’t think so,’ said Pascoe. ‘I was speaking figuratively. Before your boy-friend rescues you. You remember that sequence? Were you in fact struck?’

‘I don’t think so,’ said Mrs Abbott. ‘It’s six months ago, of course. How do you mean, struck?’

‘Hit on the face. So hard that you’d bleed. Lose a few teeth even,’ said Pascoe, feeling as daft as she obviously thought he was.

‘You are one of them funny buggers,’ she said, laughing. ‘Do I look as if I’d let meself get beaten up for a picture? Here, can you see any scars? And take a look at them. Them’s all me own, I’ve taken good care on ’em.’

Pascoe looked at her un-made-up and unblemished face, then examined her teeth which, a couple of fillings apart, were in a very healthy state.

‘Yes, I see,’ he said. ‘Well, I’m sorry to have bothered you, Mrs Abbott. You saw nothing at all during the making of the film that surprised you?’

‘You stop being surprised after a bit,’ she said. ‘But there was nowt unusual, if that’s what you mean. It’s all done with props and paint, love, didn’t you know?’

‘Even the sex?’ answered Pascoe sharply, stung by her irony.

‘Is that what it’s all about then?’ she said. ‘I might have known.’

‘No, really, it isn’t,’ assured Pascoe, adding, in an attempt to re-ingratiate himself, ‘I’ve been at your house by the way. I said I was a washing-machine salesman.’

‘Why?’

‘I didn’t want to stir anything up,’ he said, feeling noble.

‘For crying out loud!’ said Mrs Abbott. ‘You don’t reckon I could do me job without Bert knowing?’

‘No, I suppose not,’ said Pascoe, discomfited.

‘Bloody right not,’ said Mrs Abbott. ‘And I’ll tell you something else for nothing. It’s a job. I get paid for it. And whatever I do, I do with lights on me, and a camera, and a lot of technicians about who don’t give a bugger, and you can see everything I do up there on the screen. I’m not like half these so-called real actresses who play the Virgin Mary all day, then screw themselves into another big part all night. Lorraine! I told you to keep off of that road!’

‘Well, thank you, Mrs Abbott,’ said Pascoe, glancing at his watch. ‘You’ve been most helpful. I’m sorry to have troubled you.’

‘No trouble, love,’ said Mrs Abbott.

He dug into his pocket and produced a ten-pence piece which he gave to Lorraine ‘for sweeties’. She waited for her mother’s nod before accepting and Pascoe drove off feeling relieved that after all he had not been categorized as a ‘funny bugger’, and feeling also that at the moment Jack Shorter would top his own personal list.

He needn’t have worried about his meeting. It started late because of the non-arrival of one of the senior members and was almost immediately suspended because of the enforced departure of another. Reluctantly Pascoe found a phone and rang Ellie to say that his estimate of a seven o’clock homecoming had been optimistic.

‘Surprise,’ she said. ‘Will you eat there?’

‘I suppose so,’ he said.

‘I was hoping you’d take me out. You get better service with a policeman.’

‘Sorry,’ said Pascoe. ‘Better try an old boy-friend. See you!’

He replaced the receiver and went back to the conference room where Inspector Ray Crabtree of the local force told him they were scheduled to restart at seven.

‘Fancy a jar?’ asked Crabtree. He was a man of forty plus who had gone as far as he was likely to go in the force and had a nice line in comic bitterness which usually entertained Pascoe.

‘And a sandwich,’ said Pascoe.

‘Where do you fancy? Somewhere squalid or somewhere nice?’

‘Is the beer better somewhere squalid?’

‘No.’

‘Or the food cheaper?’

‘Not so’s you’d notice.’

‘Then somewhere nice.’

‘That’s a sharp mind you’ve got there, Pascoe,’ said Crabtree admiringly. ‘You’ll get on.’

‘Somewhere nice’ was the lounge bar of a large, plush and draughty hotel.

Crabtree ordered four halves of bitter.

‘And two rounds of ham, Cyril,’ he added. ‘Tell ’em it’s me and I like it cut with a blunt knife.’

‘They only serve halves in here,’ he said as they sat down. ‘Bloody daft. You’ve got to get them in twos. Wouldn’t do for Sitting Bull.’

‘Who?’

‘Dalziel. Your big chief. You know, I could have had his job.’

‘I didn’t know that,’ said Pascoe.

‘Oh yes. We were up before the same promotion board once. I thought I’d clinched it. They asked, are you as thick as Prince Philip? “Oh yes,” says I. “Twice as thick.”’

‘And what did Dalziel say?’

‘He said, “Who’s she”?’

The sandwiches arrived, filled with thick slices of succulent ham, and Pascoe understood the advantages of a blunt knife.

‘Do you know a company called Homeric Films?’ he asked for the sake of something to say.

Crabtree paused in his chewing.

‘Yes,’ he said after a moment and took another bite.

‘End of conversation, is it?’ said Pascoe.

‘You could ask if I’d seen any good films lately,’ said Crabtree.

‘All right. Have you?’

‘Yes, but none of ’em were made by Homeric. They’re a skin-flick bunch, but if you know enough to ask about them, you probably know as much as me.’

‘Why the pause for thought, then?’

‘I said you’d a sharp mind. Mebbe I was just chewing on a bit of gristle.’

‘It seems to me,’ said Pascoe, ‘that they have more sense here than to serve you gristle.’

‘True. No, truth is you just jumped in front of my train of thought. What’s your interest?’

‘No interest. They just cropped up apropos of something. What was your train of thought?’

Crabtree finished his first half and started on his second.

‘See in the corner to the left of the door?’ he said into his glass.

‘Yes,’ said Pascoe glancing across the room. Three people sat round a table in animated conversation. Two were men. They looked like brothers in their fifties, balding, fleshy. The third was a woman, gross beyond the wildest dreams of gluttony. Surely, thought Pascoe, no deficiency of diet could have produced those avalanches of flesh. She wore a kaftan made from enough shot silk to have pavilioned a whole family of Tartars in splendour, and girded quite a few of them into the bargain. Dalziel would love her. It is not enough (Pascoe paraphrased) to lose weight; a man must also have a friend who is grotesquely fat.

‘Homeric Films,’ said Crabtree. ‘They put me in mind.’

‘How?’ asked Pascoe but before Crabtree could answer, the huge woman rose and rolled across the room towards them.

‘Raymond, my sweet,’ she said genially. ‘How pleasant and how opportune. I hope I’m not interrupting anything?’

Pascoe stared in amazement. It was not just that on closer view he realized how much he’d underestimated the woman’s proportions. It was the voice. Seductive, amused, hinting at understanding, promising pleasure. He recognized it. He’d heard it on the phone that morning.

‘Inspector Pascoe,’ said Crabtree, rising. ‘I’d like you to meet Miss Latimer. Miss Latimer is managing director of Homeric Films.’

‘Why so formal, Ray? I’m Penelope to all Europe and just plain Penny to my friends. But soft awhile. Pascoe?’

‘We spoke this morning.’

‘So! When a girl says come up and see me, you let no grass grow!’

‘It’s an accident,’ said Pascoe unchivalrously. ‘But I’m glad to meet you.’

‘Join us, Penny?’ said Crabtree.

‘Just for a moment.’

She redistributed herself around a chair and smiled sweetly at Pascoe. She had a very sweet smile. Indeed, trapped in that flesh like a snowdrop in aspic, a small, pretty, girlish face seemed to be staring out.

‘Will you have a jar?’ asked Crabtree.

‘Gin with,’ said the woman.

‘It’s my shout,’ said Pascoe.

‘It’s my patch,’ said Crabtree, rising.

‘How’s the case, Inspector?’ asked Penny Latimer.

‘No case,’ said Pascoe. ‘People tell us things, we’ve got to look into them.’

‘And you’ve looked into Linda Abbott?’

‘Do you know her? Personally, I mean,’ countered Pascoe.

‘Only as an actress. Socially I know nothing, which was why we struck our little bargain, just in case. How were her teeth?’

‘Complete.’

‘Don’t sound so disappointed, dear. What now? Would you still like to see Gerry?’

‘I don’t know. Not unless I really have to. But you never know.’

‘You could spend an interesting day on the set,’ she said. ‘Really. I mean it. Do you good.’

‘How?’

‘For a start, it’d bore you to tears. You might find it distasteful but you wouldn’t find it illegal. And at the end of the day you might even agree that though it’s not your way of earning a living, there’s no reason why it shouldn’t be somebody else’s.’

Pascoe downed his second half in one and said, ‘You’re very defensive.’

‘And I know it. You’re bloody aggressive, and I don’t think you do.’

‘I don’t mean to be,’ said Pascoe.

‘No. It’s your job. Like one of your cars stopping some kid on a flash motor-bike. His licence is in order, but he’s young, and he’s wearing fancy gear, and he doesn’t look humble, so he gets the full treatment. Finally, reluctantly, he gets sent on his way with a warning against breathing, and the Panda-car tracks him for the next ten miles.’

‘I grasp your analogy,’ said Pascoe.

‘Chance’d be a fine thing,’ she answered. Their gazes locked and after a moment they started to laugh.

‘Watch her,’ said Crabtree plonking down a tray with a large gin, with whatever it was with, and another four halves. ‘She’ll have you starring in a remake of the Keystone Cops – naked.’

‘I doubt it,’ said the woman. ‘The Inspector don’t approve of us beautiful people. Not like you, Ray. Ray recognizes that police and film people have a lot in common. They exist because of human nature, not in spite of it. But Ray has slain the beast, ambition, and now takes comfort in the arms of the beauty, philosophy. You should try it, Inspector.’

‘I’ll bear it in mind,’ was the smartest reply Pascoe could manage.

‘You do. And don’t forget my invitation. Homeric’s the company, Penelope’s the name. I’ll be weaving and watching for you, sailor. ’Bye, Ray. Thanks for the drink.’

She rose and returned to her companions.

‘Interesting woman,’ said Crabtree, regarding Pascoe with amusement.

‘Yes. Is she like that through choice or chance?’

‘Glandular, they tell me. Used to be a beauty. Now she has to live off eggs and spinach and no good it does her.’

‘Tough,’ said Pascoe. ‘Tell me, Ray, what’s a joint like Homeric doing in a nice town like this?’

Crabtree shrugged.

‘They have an office. They pay their rates. They give no offence. The only way that most people are going to know what their precise business is would be to see their films, or take part in one of them. Either way, you’re not going to complain. Things have changed since I was a callow constable, but one thing I’ve learned in my low-trajectory meteoric career: if it’s all right with top brass, it’s all right with me.’

‘But why come here at all? What’s wrong with the Big Smoke?’

‘Dear, dear,’ said Crabtree. ‘I bet you still think Soho’s full of opium dens and sinister Orientals. Up here it’s cheaper, healthier and the beer’s better. Do you never read the ads?’

‘Everyone’s talking smart today and putting me down,’ said Pascoe. ‘Time for another?’

‘Hang on,’ said Crabtree. ‘I’ll phone in.’

He returned with another four halves.

‘Plenty of time,’ he said. ‘It’s been put back again.’

‘When to?’

‘Next week.’

‘Oh shit,’ said Pascoe.

He regarded the half-pints dubiously, then went and rang Ellie again. There was no reply. Perhaps after all she had rung an old boy-friend.

‘Left you, has she?’ said Crabtree. ‘Wise girl. Now, what do you fancy – drown your sorrows or a bit of spare?’

He arrived home at midnight to find a strange car in his drive and a strange man drinking his whisky. Closer examination revealed it was not a strange man but one of Ellie’s colleagues, Arthur Halfdane, a historian and once a sort of rival for Ellie’s favours.

‘I didn’t recognize you,’ said Pascoe. ‘You look younger.’

‘Well thanks,’ said Halfdane in a mid-Atlantic drawl.

‘On second thoughts,’ said Pascoe belligerently, ‘you don’t look younger. It’s your clothes that look younger.’

Halfdane glanced down at his denim suit, looked ironically at Pascoe’s crumpled worsted, and smiled at Ellie.

‘Time to go, I think,’ he said, rising.

Perhaps I should punch him on the nose, thought Pascoe. Man alone with my wife at midnight … I’m entitled.

When Ellie returned from the front door Pascoe essayed a smile.

‘You’re drunk,’ she said.

‘I’ve had a couple.’

‘I thought you were at a meeting.’

‘It was cancelled,’ he said. ‘I rang you. You were out. So I made a night of it.’

‘Me too,’ she said.

‘Difference was, my companion was a man,’ said Pascoe heavily.

‘No difference,’ said Ellie. ‘So was mine.’

‘Oh,’ said Pascoe, a little nonplussed. ‘Have a good evening, did you?’

‘Yes. Very sexy.’

‘What?’

‘Sexy. We went to see your dirty film. Our interest was socio-historical, of course.’

‘He took you to the Calli?’ said Pascoe indignantly. ‘Well, bugger me!’

‘It was all right,’ said Ellie sweetly. ‘Full of respectable people. You know who I saw there? Mr Godfrey Blengdale, no less. So it must be all right.’

‘He shouldn’t have taken you,’ said Pascoe, feeling absurd and incoherent and nevertheless right.

‘Get it straight, Peter,’ said Ellie coldly. ‘Dalziel may have got you trained like a retriever, but I still make my own decisions.’

‘Oh yes,’ sneered Pascoe. ‘It’s working in that elephants’ graveyard that does it. All that rational discourse where the failed intellectuals go to die. The sooner they close that stately pleasure-dome down and dump you back in reality, the better!’

‘You’ve got the infection,’ she said sadly. ‘Work in a leper colony and in the end you start falling to bits.’

‘Schweitzer worked with lepers,’ countered Pascoe.

‘Yes. And he was a fascist too.’

He looked at her hopelessly. There were other planets somewhere with life-forms he had more chance of understanding and making understand.

‘It’s your failures I put in gaol,’ he said.

‘So, blame education, is that it? All right, but how can it work with kids when intelligent adults can still be so thick!’ she demanded.

‘I didn’t mean that,’ he said. He suddenly saw in his mind’s eye the girl in the film. The face fell apart under the massive blow. It might all be special effects but the reality beneath the image was valid none the less. If only it could be explained …

‘There is still, well, evil,’ he essayed.

‘Oh God. Religion, is it, now? The last refuge of egocentricity. I’m off to bed. I’m driving down to Lincolnshire tomorrow, so I should prefer to pass the night undisturbed.’

She stalked from the room.

‘So should I,’ shouted Pascoe after her.

Their wishes went unanswered.

At five o’clock in the morning he was roused from the unmade-up spare bed by Ellie pulling his hair and demanding that he answer the bloody telephone.

It was the station.

There had been a break-in at Wilkinson House, premises of the Calliope Kinema Club. The proprietor had been attacked and injured. Mr Dalziel wondered if Mr Pascoe, in view of his special interest in the place, would care to watch over the investigation.

‘Tell him,’ said Pascoe. ‘Tell him to …’

‘Yes?’ prompted the voice.

‘Tell him I’m on my way.’

Chapter 5 (#u6c4fab43-6061-549e-8da1-3cc3e619d8e2)

The Calli was a wreck.

As far as Pascoe could make out, person or persons unknown had entered by forcing the basement area door which fronted on to Upper Maltgate. They had then proceeded to wreck the house and beat up Gilbert Haggard, not necessarily in that order. That would be established when Haggard was fit enough to talk. A not very efficient attempt to start a fire had produced a lot of smoke, but fortunately very little flame, and a Panda patrol checking shop doorways on Maltgate had spotted the fumes escaping from a first-floor window.

When they entered the house, they had found Haggard on the second-floor landing, badly beaten round the face and abdomen. A combination of the blows and fumes had rendered him unconscious.

Pascoe wandered disconsolately around the house accompanied by a taciturn Sergeant Wield and an apologetic Fire Officer.

‘Was there any need to pump so much water into the place?’ asked Pascoe. ‘My men say there was next to no fire.’

‘Can’t be too careful, not where there’s inflammable material like film about,’ said the FO, smiling wanly at the staircase which was still running like the brook Kerith. ‘Sorry if we’ve dampened any clues.’

‘Clues!’ said Pascoe. ‘I’ll need frogmen to bring up clues from this lot. Where did the fire start?’

‘In a store room on the first floor. There’s a couple of filing cabinets in there, and that’s where they kept their cans of film as well. Someone scattered everything all over the place, then had the bright idea of dropping a match into it on their way out.’

‘Can we get in there without a bathysphere?’ asked Pascoe.

The FO didn’t answer but led the way upstairs.

There was a sound of movement inside the storage room and Pascoe expected to find either a policeman or a fireman bent on completing the destruction his colleagues had begun. Instead in the cone of light from a bare bulb which had miraculously survived the visiting firemen, he found Maurice Arany.

‘Mr Arany,’ he said. ‘What are you doing here?’

‘I own half of this,’ said Arany sharply, indicating the sodden debris through which he appeared to have been picking.

‘I don’t like the look of your half,’ said Pascoe. ‘You got here quickly.’

Arany considered.

‘No,’ he said. ‘You got here slowly. I live quite close by. I have a flat above Trimble’s, the bakers, on Lower Maltgate.’

‘Who called you?’ asked Pascoe.

‘No one. I am a poor sleeper. I was awake when I heard the fire-engine going up the street. I looked out, became aware they were stopping by the Square, so I dressed and came out to investigate. After the firemen had finished, I came in. No one stopped me. Should they have done so?’

‘Perhaps,’ said Pascoe. ‘I should have thought you would be more concerned with Mr Haggard’s health than checking on damage here.’

‘I saw him being put in the ambulance. He looked all right,’ said Arany indifferently. ‘I tried to ring through a moment ago. The phones seem not to be working.’

‘Check that,’ Pascoe said to Wield. ‘See what’s wrong with them. Probably an excess of moisture.’

Turning back to Arany, he said, ‘It would be useful, Mr Arany, if you could check if there’s anything missing from the house.’

‘That’s what I’m doing,’ said Arany, dropping the goulash of charred paper and shrivelled celluloid he held in his hands. ‘Of course, I cannot answer for Gilbert’s apartments. But on this floor and in the club rooms, I think I can help.’

‘Well, start here,’ said Pascoe. ‘Anything missing?’

‘Who can tell? So much is burned. We kept old files of business correspondence here. Nothing of importance.’

‘And the films?’

‘And the films. Yes, they are finished. Still, the insurance will cover that.’

‘Someone’s going to be disappointed,’ said Pascoe, looking at the mess. ‘They won’t show those again.’

‘There are plenty of prints,’ said Arany carelessly. ‘I’ll go and check the other rooms.’

He went out as the sergeant returned. Wield waited till he was gone before saying, ‘The phone wire was cut, sir.’

‘Inside or out?’

‘Inside. By the phone in the study. Both the other phones in the house are extensions.’

‘Let’s look upstairs,’ said Pascoe.

Haggard had been found lying outside his bedroom door which was two doors down the landing from the study. In between was a living-room which had been comfortably if shabbily furnished with two chintz-covered armchairs and a solid dining table. Now the chairs lay on their sides with the upholstery slashed. The table’s surface was scarred and a corner cabinet had been dragged off the wall.

‘What’s through there?’ asked Pascoe, pointing at a door in the far wall.

‘Kitchen,’ said Wield, pushing it open.

It was a long narrow room, obviously created by walling off the bottom five feet of the living-room at some time in the not-too-distant past. The furnishings were bright and modern. Pascoe walked around opening cupboards. One was locked, a full-size door which looked as if it might lead into a pantry.

‘Notice anything odd?’ he asked in his best Holmesian fashion.

‘They didn’t smash anything in here,’ said Wield promptly.

‘All right, all right. There’s no need to be so clever,’ said Pascoe. ‘Probably they just didn’t have time.’

The bedroom was in a mess too, but it was the study which really caught his attention, perhaps because he had seen it before the onslaught.

Everything that could be cut, slashed, broken or overturned had been. Only the heavier items of furniture remained unmoved, though drawers had been dragged from the desk and the display cabinet had been overturned. Pascoe’s attention was caught particularly by the shredded curtains and he examined them thoughtfully for a long time.

‘Anything, sir?’ asked Wield.

‘Something, perhaps, but I really don’t know what. They must have made some noise. Who lives next door?’

‘Just two old ladies and their cats. They sleep on the floor below, I think, and they’re both as deaf as toads. They’ve lived there all their lives, and they’re both in their seventies now. I gather the vigilantes were dead keen to recruit them for their anti-Calli campaign, but it was no go.’

‘Didn’t they mind the Club, then?’

‘They are, or were, very thick with Haggard. The elder, Miss Annabelle Andover, acted as a part-time matron while the school was on the go, and I get the impression that he’s been at pains to keep up the connection. You know, chicken for the cats, that kind of thing. If it ever did come to a court case, it’d be useful for him to be able to prove his immediate neighbours didn’t object to the Club.’

‘Which they don’t? It’s a bit different from a school!’

‘I can’t really say, sir,’ said Wield. ‘Old ladies, old-fashioned ideas, you’d say. But you never know.’

‘Well, we’d better have a chat in case they did notice anything. But at a decent hour. Let’s check on Haggard first. Then I reckon we’ve earned some breakfast.’

At the hospital they learned that Haggard, though intermittently conscious, was not in a fit state to be questioned so they had bacon sandwiches and coffee in the police canteen before returning to the Club.

Arany was still there.

‘Anything missing yet?’ asked Pascoe.

‘Not that I have found,’ said Arany. ‘Some drink from the bar, perhaps. It is hard to say, so much is broken.’

‘Well, keep at it. Perhaps you could call down at the station later, put it down on paper.’

‘What?’ enquired Arany. ‘There is nothing to put.’

‘Oh, you never can tell,’ said Pascoe airily. ‘First impressions when you arrived, that kind of thing. And by the way, would you bring a complete up-to-date list of members with you? Come on, Sergeant. Let’s see if the Misses Andover are up and about yet.’

The Misses Andover were, or at least their curtains were now drawn open. Pascoe pulled at the old bell-toggle and the distant clang was followed by an equally distant opening and shutting of doors and the slow approach of hard shoes on bare boards. It was like a Goon-show sound track, he thought. Eventually the door opened and a venerably white-haired head slowly emerged. Timid, bird-like eyes scanned them.

‘Miss Andover?’ said Pascoe.

The head slowly retreated.

‘Annabelle!’ cried a surprisingly strong voice. ‘There are callers enquiring if you are at home.’

‘Tradesmen?’ responded a distant voice.

‘I thought you said they were deaf,’ murmured Pascoe.

‘They are. They switch their aids off at night,’ answered Wield.

The head re-emerged, accompanied by a hand which fitted a pair of pince-nez to the little nose, and proceeded to scan the two policemen. When it came to Wield’s turn, the head jerked in what might have been recognition or shock and withdrew once more.

‘Mr Wield is one of them, Annabelle.’

‘Then admit them, admit them, you fool.’

The door swung full open and they stepped into the past.

Nothing in here had changed for two generations, thought Pascoe looking round the dark panelled hall. Except the woman who stood before him, smiling. She must have been young and pretty and full of hope when the men delivered that elephant’s foot umbrella stand. Now the folds of skin on her neck were almost as grey and wrinkled as those on the huge foot which had been raised for the last time on some Indian plain and set down (no doubt to the ghostly beast’s great amazement) here in darkest Yorkshire.

‘Miss Andover will be down presently,’ announced the woman, her eyes darting nervously from one to the other.

‘Thank you, Miss Alice,’ said Wield.

‘Miss Alice Andover?’ said Pascoe.

Wield smiled.

‘Then you too are Miss Andover,’ Pascoe stated brightly.

‘Oh no,’ said the woman, shocked. ‘I am Miss Alice Andover. This is Miss Andover.’

She indicated the figure of (Pascoe presumed) her elder sister descending the gloomy staircase.

The sisters were dressed alike in long flowered skirts which might have been antiques or the latest thing off C & A’s racks. From the starched fronts of their plain white blouses depended the receivers of two rather old-fashioned hearing aids. Annabelle, however, was several inches the taller and wore her even whiter hair in a simple page-boy cut while her sister had hers pulled back into a severe bun. Her face had probably never been as pretty as her sister’s, but she had an alert intelligent expression missing from the younger woman’s.

‘My dear,’ said Alice, ‘this is Mr Wield, as you know, but I’m afraid the other gentleman has not been presented.’

‘My fault entirely,’ said Pascoe, entering into the spirit of the thing. ‘Perhaps I may be allowed to break with convention and present myself?’

‘Whoever you are,’ said Miss Annabelle, ‘there’s no need to treat us both like half-wits even if m’sister asks for it. Alice, stop being a stupid cow, will you, dear? She saw Greer Garson in Pride and Prejudice on the box the other week and she’s not been the same since. Let’s go in here.’

She led the way into a bright Habitat-furnished sitting-room with the largest colour television set Pascoe had ever seen lowering from one corner.

‘Well?’ said Miss Andover impatiently, taking up a stance in front of the fireplace and lighting a Park Drive. ‘As you’re with the sergeant, I presume you’re a cop, and from the way he’s hanging back behind you, you must have some rank. Unless you’re a princess and he’s just married you.’

The quip amused her so much that she laughed till she coughed.

Pascoe waited till she’d finished both activities and introduced himself in a brusque twentieth-century fashion.

‘The house next door, Dr Haggard’s house, was broken into last night and a deal of damage done. I wondered if either of you heard anything?’

Miss Alice gasped in fright and seemed to shrink into herself but her sister just whistled in surprise, then shook her head, pointing to her hearing aid.

‘An advantage of this thing is that I need hear only what I want to. It’s very useful at night and when I’m with extremely boring people.’

‘So you heard nothing?’ persisted Pascoe.

‘I’ve said so.’

‘Miss Alice?’

‘Oh no. I switched off too,’ said Alice, evidently retrieved to the present moment by her sister’s command.

‘Which side of the house do you sleep?’ asked Pascoe, causing a time-slip in Miss Alice who put her hand to her mouth in horror at his indelicacy.

‘First floor on the Wilkinson House side,’ said Miss Annabelle. ‘Alice is at the back, I’m at the front.’

‘It’s a very large house,’ said Pascoe. ‘May I have a look upstairs just to get an impression of where you’d be in relation to next door?’

‘By all means,’ said Miss Annabelle. ‘Follow me.’

They set off in procession up the gloomy stairs, the older woman leading, the two men close behind and the younger sister trailing.

On the first floor they halted and Miss Annabelle flung open doors.

‘These are our bedrooms. Mine here and that’s Alice’s. As you can see, they abut on to Wilkinson House, but we weren’t disturbed. Over there are another couple of rooms, used to be our parents’ bedroom and dressing-room. We don’t use them now. Bathroom, boxroom. We use this as a sewing-room or rather Alice does. Me, I was never a hand with the needle. But Alice is an expert. Makes all our clothes in here. Gets the best light, you see.’

Pascoe peered in. The room was full of material, some of it draped around a dressmaker’s dummy. On a smooth polished table stood an ancient foot-operated sewing machine and a work basket with all the tools of the art, needles, cotton reels, buttons, pinking shears, edging tape, everything.

‘A hive of industry,’ he said brightly. ‘It’s a big house. You live here alone?’