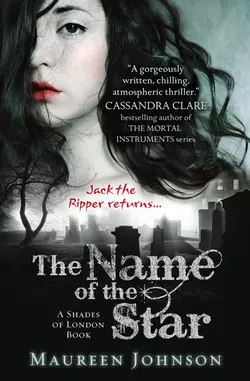

The Name of the Star

Maureen Johnson

Thrilling ghost-hunting teen mystery as modern-day London is plagued by a sudden outbreak of brutal murders that mimic the horrific crimes of Jack the Ripper."A gorgeously written, chilling, atmospheric thriller. The streets of London have never been so sinister or so romantic." Cassandra Clare, author of THE MORTAL INSTRUMENTSSixteen-year-old American girl Rory has just arrived at boarding school in London when a Jack the Ripper copycat-killer begins terrorising the city. All the hallmarks of his infamous murders are frighteningly present, but there are few clues to the killer’s identity.“Rippermania” grabs hold of modern-day London, and the police are stumped with few leads and no witnesses. Except one. In an unknown city with few friends to turn to, Rory makes a chilling discovery…Could the copycat murderer really be Jack the Ripper back from the grave?

Copyright

First published in hardback in the USA by G. P. Putnam’s Sons, a division of Penguin Young Readers Group in 2011

First published in paperback in Great Britain by HarperCollins Children’s Books in 2011

HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd,

1 London Bridge Street

London, SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

THE NAME OF THE STAR. Copyright © 2011 by Maureen Johnson. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Maureen Johnson asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of the work.

Source ISBN: 9780007398638

Ebook Edition © AUGUST 2011 ISBN: 9780007432257

Version: 2018-06-19

Dedication

For Amsler.

Thanks for the milk.

Contents

Cover (#ulink_287b0376-7262-5600-a454-1a359f3b78e4)

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

The Return

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

Persistent Energy

10

11

12

13

14

15

The Star That Kills

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

Inner Vileness

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

Terminus

33

34

35

36

37

38

Acknowledgments

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

DURWARD STREET, EAST LONDON

AUGUST 31

4:17 A.M.

EYES OF LONDON WERE WATCHING CLAIRE JENKINS.

She didn’t notice them, of course. No one paid attention to the cameras. It was an accepted fact that London has one of the most extensive CCTV systems in the world. The conservative estimate was that there were a million cameras around the city, but the actual number was probably much higher and growing all the time. The feed went to the police, security firms, MI5, and thousands of private individuals—forming a loose and all-encompassing net. It was impossible to do anything in London without the CCTV catching you at some point.

The cameras silently recorded Claire’s progress and tracked her as she turned onto Durward Street. It was four seventeen A.M., and she was supposed to have been at work at four. She had forgotten to set her alarm, and now she was running, trying to get to the Royal London Hospital. Her shift usually got the fallout from last night’s drinking—the alcohol poisonings, the falls, the punch-ups, the car accidents, the occasional knife fight. All the night’s mistakes came to the early-shift nurse.

It had been pouring, clearly. There were puddles all over the place. The one mercy of this doomed morning was that there was only the slightest drizzle now. At least she didn’t have to run through the rain. She got out her phone to send a message to let them know she was close. The phone emitted a tiny halo that encircled her hand, giving it a saintly glow. It was hard to text and walk at the same time, not if she didn’t want to fall off the pavement or walk into a post. Am running lake…

Claire had tried to type the word late three times, but it kept coming up as lake. She wasn’t running lake, she was running late. She refused to stop walking and fix it. There was no time to waste. The message would stand.

…Be there in 5…

And then she tripped. The cell phone took flight, a little glowing ball of light, free at last before it clattered to the sidewalk and went out.

“Bugger!” she said. “No, no, no … don’t be broken …”

In her concern over the fate of her phone, Claire first didn’t take notice of the thing she had tripped over, aside from faintly registering that it was somewhat large and weighty and it gave a little when her foot struck it. In the dark, it appeared to be a strangely shaped mound of garbage. Something else put in her way this morning to impede her progress.

She knelt down and felt along the ground for the phone, sinking her knee directly into a puddle.

“Wonderful,” she said to herself as she scrabbled around. The phone was quickly recovered. It appeared to be dark and lifeless. She tried the power button, not expecting any result. To her delight, the phone blinked on, casting its little light around her hand once again.

This was when she first noticed that there was something sticky on her hand. The consistency was extremely familiar, as was the faint metallic smell.

Blood. Her hand was covered in blood. A lot of blood, with a faintly jelly-like consistency that suggested congealing. Congealing blood meant blood that had been here for several minutes, so it couldn’t be her own. Claire shifted around, holding up her phone for light. She could see now that she had tripped over a person. She crawled closer and felt a hand, a hand that was cool, but not cold.

“Hello?” she said. “Can you hear me? Can you speak?”

She got up alongside the figure, a smallish person dressed entirely in motorcycle leathers, wearing a helmet. She reached up to the neck to feel for a pulse.

Where the neck was supposed to be, there was a space.

It took her a moment to process what she was feeling, and in desperation she kept reaching around the edge of the helmet to get to the neck, trying to get a sense of the size of this wound. It went on and on, until Claire realized that the head was barely attached at all, and that the puddle she was kneeling in was almost certainly not rainwater.

The eyes saw it all.

THE RETURN

Then shall the slayer return, and come unto his own city, and unto his own house, unto the city whence he fled.

—Joshua 20:6

1

F YOU LIVE AROUND NEW ORLEANS AND THEY THINK a hurricane might be coming, all hell breaks loose. Not among the residents, really, but on the news. The news wants us to worry desperately about hurricanes. In my town, Bénouville, Louisiana (pronounced locally as Ben-ah-VEEL; population 1,700), hurricane preparations generally include buying more beer, and ice to keep that beer cold when the power goes out. We do have a neighbor with a two-man rowboat lashed on top of the porch roof, all ready to go if the water rises—but that’s Billy Mack, and he started his own religion in the garage, so he’s got a lot more going on than just an extreme concern for personal safety.

Anyway, Bénouville is an unstable place, built on a swamp. Everyone who lives there accepts that it was a terrible place to build a town, but since it’s there, we just go on living in it. Every fifty years or so, everything but the old hotel gets wrecked by a flood or a hurricane—and the same bunch of lunatics comes back and builds new stuff. Many generations of the Deveaux family have lived in beautiful downtown Bénouville, largely because there is no other part to live in. I love where I’m from, don’t get me wrong, but it’s the kind of town that makes you a little crazy if you never leave, even for a little while.

My parents were the only ones in the family to leave to go to college and then law school. They became law professors at Tulane, in New Orleans. They had long since decided that it would be good for all three of us to spend a little time living outside of Louisiana. Four years ago, right before I started high school, they applied to do a year’s sabbatical teaching American law at the University of Bristol in England. We made an agreement that I could take part in the decision about where I would spend that sabbatical year—it would be my senior year. I said I wanted to go to school in London.

Bristol and London are really far apart, by English standards. Bristol is in the middle of the country and far to the west, and London is way down south. But really far apart in England is only a few hours on the train. And London is London. So I had decided on a school called Wexford, located in the East End of London. The three of us were all going to fly over together and spend a few days in London, then I would go to school and my parents would go to Bristol, and I would travel back and forth every few weeks.

But then there was a hurricane warning, and everyone freaked out, and the airlines wiped the schedule. The hurricane teased everyone and rolled around the Gulf before turning into a rainstorm, but by that point our flight had been canceled and everything was a mess for a few days. Eventually, the airline managed to find one empty seat on a flight to New York, and another empty seat on a flight to London from there. Since I was scheduled to be at Wexford before my parents needed to be in Bristol, I got the seat and went by myself.

Which was fine, actually. It was a long trip—three hours to New York, two hours wandering the airport before taking a six-hour flight to London overnight—but I still liked it. I was awake all night on the flight watching English television and listening to all the English accents on the plane.

I made my way through the duty-free area right after customs, where they try to get you to buy a few last-minute gallons of perfume and crates of cigarettes. There was a man waiting for me just beyond the doors. He had completely white hair and wore a polo shirt with the name Wexford stitched on the breast. A shock of white chest hair popped out at the collar, and as I approached him, I caught the distinctive, spicy smell of men’s cologne. Lots of cologne.

“Aurora?” he asked.

“Rory,” I corrected him. I never use the name Aurora. It was my great-grandmother’s name, and it was dropped on me as kind of a family obligation. Not even my parents use it.

“I’m Mr. Franks. I’ll be taking you to Wexford. Let me help you with those.”

I had two incredibly large suitcases, both of which were heavier than I was and were marked with big orange tags that said HEAVY. I needed to bring enough to live for nine months. Nine months in a place that had cold weather. So while I felt justified in bringing these extremely big and heavy bags, I didn’t want someone who looked like a grandfather pulling them, but he insisted.

“You picked quite the day to arrive, you did,” he said, grunting as he dragged the suitcases along. “Big news this morning. Some nutter’s gone and pulled a Jack the Ripper.”

I figured “pulled a Jack the Ripper” was one of those English expressions I’d need to learn. I’d been studying them online so I wouldn’t get confused when people started talking to me about “quid” and “Jammy Dodgers” and things like that. This one had not crossed my electronic path.

“Oh,” I said. “Sure.”

He led me through the crowds of people trying to get into the elevators that took us up to the parking lot. As we left the building and walked into the lot, I felt the first blast of cool breeze. The London air smelled surprisingly clean and fresh, maybe a little metallic. The sky was an even, high gray. For August, it was ridiculously cold, but all around me I saw people in shorts and T-shirts. I was shivering in my jeans and sweatshirt, and I cursed my flip-flops—which some stupid site told me were good to wear for security reasons. No one mentioned they make your feet freeze on the plane and in England, where they mean something different when they say “summer.”

We got to the school van, and Mr. Franks loaded the bags in. I tried to help, I really did, but he just said no, no, no. I was almost certain he was going to have a heart attack, but he survived.

“In you get,” he said. “Door’s open.”

I remembered to get in on the left side, which made me feel very clever for someone who hadn’t slept in twenty-four hours. Mr. Franks wheezed for a minute once he got into the driver’s seat. I cracked my window to release some of the cologne into the wild.

“It’s all over the news.” Wheeze, wheeze. “Happened up near the Royal Hospital, right off the Whitechapel Road. Jack the Ripper, of all things. Mind you, tourists love old Jack. Going to cause lots of excitement, this. Wexford’s in Jack the Ripper territory.”

He switched on the radio. The news station was on, and I listened as he drove us down the spiral exit ramp.

“…thirty-one-year-old Rachel Belanger, a commercial filmmaker with a studio on Whitechapel Road. Authorities say that she was killed in a manner emulating the first Jack the Ripper murder of 1888…”

Well, at least that cleared up what “pulling a Jack the Ripper” meant.

“…body found on Durward Street, just after four this morning. In 1888, Durward Street was called Bucks Row. Last night’s victim was found in the same location and position as Mary Ann Nichols, the first Ripper victim, with very similar injuries. Chief Inspector Simon Cole of Scotland Yard gave a brief statement saying that while there were similarities between this murder and the murder of Mary Ann Nichols on August 31, 1888, it is premature to say that this is anything other than a coincidence. For more on this, we go to senior correspondent Lois Carlisle …”

Mr. Franks barely missed the walls as he wove the car down the spiral.

“… Jack the Ripper struck on four conventionally agreed upon dates in 1888: August 31, September 8, the ‘Double Event’ of September 30—so called because there were two murders in the space of under an hour—and November 9. No one knows what became of the Ripper or why he stopped on that date …”

“Nasty business,” Mr. Franks said as we reached the exit. “Wexford is right in Jack’s old hunting grounds. We’re just five minutes from the Whitechapel Road. The Jack the Ripper tours come past all the time. I imagine there’ll be twice as many now.”

We took a highway for a while, and then we were suddenly in a populated area—long rows of houses, Indian restaurants, fish-and-chip shops. Then the roads got narrower and more crowded and we had clearly entered the city without my noticing. We wound along the south side of the Thames, then crossed it, all of London stretched around us.

I had seen a picture of Wexford a hundred times or more. I knew the history. Back in the mid-1800s, the East End of London was very poor. Dickens, pickpockets, selling children for bread, that kind of thing. Wexford was built by a charity. They bought all the land around a small square and built an entire complex. They constructed a home for women, a home for men, and a small Gothic revival church—everything necessary to provide food, shelter, and spiritual guidance. All the buildings were attractive, and they put some stone benches and a few trees in the tiny square so there was a pleasant atmosphere. Then they filled the buildings with poor men, women, and children and made them all work fifteen hours a day in the factories and workhouses that they also built around the square.

Somewhere around 1920, someone realized this was all kind of horrible, and the buildings were sold off. Someone had the bright idea that these Gothic and Georgian buildings arranged around a square kind of looked like a school, and bought them. The workhouses became classroom buildings. The church eventually became the refectory. The buildings were all made of brownstone or brick at a time when space in the East End came cheap, so they were large, with big windows and peaks and chimneys silhouetted against the sky.

“This is your building here,” Mr. Franks said as the car bumped along a narrow cobblestone path. It was Hawthorne, the girls’ dorm. The word WOMEN was carved in bas-relief over the doorway. Standing right under this, as proof, was a woman. She was short, maybe just five feet tall, but broad. Her face was a deep, flushed red, and she had big hands, hands you’d imagine could make really big meatballs or squeeze the air out of tires. She had a bob haircut that was almost completely square, and was wearing a plaid dress made of hearty wool. Something about her suggested that her leisure activities included wrestling large woodland animals and banging bricks together.

As I got out of the van she called, “Aurora!” in a penetrating voice that could cause a small bird to fall dead out of the sky.

“Call me Claudia,” she boomed. “I’m housemistress of Hawthorne. Welcome to Wexford.”

“Thanks,” I said, my ears still ringing. “But it’s Rory.”

“Rory. Of course. Everything all right, then? Good flight?”

“Great, thank you.” I hurried to the back of the van and tried to get to the bags before Mr. Franks broke his spine in three places hauling them out. Flip-flops and cobblestones do not go well together, however, especially after a rain, when every slight indentation is filled with cold water. My feet were soaked, and I was sliding and stumbling over the stones. Mr. Franks beat me to the back of the car, and grunted as he yanked the bags out.

“Mr. Franks will bring those inside,” Claudia said. “Take them to room twenty-seven, please, Franks.”

“Righto,” he wheezed.

The rain started to patter down lightly as Claudia opened the door, and I entered my new home for the first time.

2

WAS IN A FOYER PANELED IN DARK WOOD WITH A mosaic floor. A large banner bearing the words WELCOME BACK TO WEXFORD hung from the inner doorway. A set of winding wooden steps led up to what I guessed were our rooms. On the wall, a large bulletin board was already full of flyers for various sports and theater tryouts.

“Call me Claudia,” Claudia said again. “Come through this way so we can have a chat.”

She led me through a door on the left, into an office. The room had been painted a deep, scholarly shade of maroon, and there was a large Oriental rug on the floor. The walls and shelves were mostly covered in hockey awards, pictures of hockey teams, mounted hockey sticks. Some of the awards had years on them and names of schools, telling me that Claudia was now in her early thirties. This amazed me, since she looked older than Granny Deveaux. Though to be fair, Granny Deveaux had permanent makeup tattooed on her eyes and bought her jeans in the juniors department at Kohl’s. Whereas Claudia, it was clear, didn’t mind getting out there in the elements and perpetrating a little physical violence in the name of sport. I could easily picture her running over a muddy hillside, field hockey stick raised, screaming. In fact, I was pretty sure that was what I was going to see in my dreams tonight.

“These are my rooms,” she said, indicating the office and whatever splendors lay behind the door by the window. “I live here, and I am available at all times for emergencies, and until nine every evening if you just want to chat. Now, let’s go through some basics. This year, you are the only student coming from abroad. As you probably know, our system here is different from the one you have at home. Here, students take tests called GCSEs when they are about sixteen …”

I did know this. There was no way I could have prepared to come here without knowing this. The GCSEs are individual tests on pretty much every subject you’ve ever studied, ever. People take between eight and fourteen of these things, depending, I guess, on how much they like taking tests. How you do on your GCSEs determines how you’re going to spend your next two years, because when you’re seventeen and eighteen, you get to specialize. Wexford was a strange and rare thing: a boarding “sixth-form college”—college here meaning “school for seventeen-and eighteen-year-olds.” It was for people who couldn’t afford five years in a fancy private school, or hated the school they were in and wanted to live in London. People only attended Wexford for two years, so instead of moving in with a bunch of people who had known each other forever, at Wexford, my new fellow students would have been together for a year at most.

“Here, at Wexford,” she went on, “students take four or five subjects each year. They are studying for their A-level exams, which they take at the end of their final year. You are welcome to sit for the A levels if you like, but since you do not require them, we can set up a separate system of grading to send back to America. I see you’ll be taking five subjects—English literature, history, French, art history, and further maths. Here is your schedule.”

She passed me a piece of paper with a huge grid on it. The schedule itself didn’t have that day-in, day-out sameness I was used to. Instead, I got this bananas spreadsheet that spanned two weeks, full of double periods and free periods.

I stared at this mess and gave up any hope of ever memorizing it.

“Now,” Claudia said, “breakfast is at seven each morning. Classes begin at eight fifteen, with a lunch break at eleven thirty. At two forty-five you change for sport—that’s from three to four. Then you shower and have class again from four fifteen until five fifteen. Dinner is from six to seven. Then the evenings are for clubs, or more sport, or work. Of course, we still need to put you into your sport. May I recommend hockey? I am in charge of the girls’ hockey team. I think you’d enjoy it.”

This was the part I’d been dreading. I am not a very sporty person. Where I come from, it’s too hot to run, and it’s generally not encouraged. The joke is, if you see someone running in Bénouville, you run in the same direction, because there’s probably something really terrible right behind them. At Wexford, daily physical activity was required. My choices were football (a.k.a. soccer, a.k.a. a lot of running outdoors), swimming (no), hockey (by this they meant field, not ice), or netball. I hate all sports, but basketball I at least know something about—and netball was supposed to be the cousin of basketball. You know how girls play softball instead of baseball? Well, netball is the softball version of basketball, if that makes any sense. The ball is softer, and smaller, and white, and some of the rules are different … but basically, it’s basketball.

“I was thinking netball,” I said.

“I see. Have you ever played hockey before?”

I looked around at the hockey decorations.

“I’ve never played it. I really only know basketball, so netball—”

“Completely different. We could start you fresh in hockey. How about we just do that now, hmmm?”

Claudia leaned over the desk and smiled and knitted her meaty hands together.

“Sure,” I heard myself say. I wanted to suck the word back into my mouth, but Claudia had already grabbed her pen and was scribbling something down and muttering, “Excellent, excellent. We’ll get you set up with a hockey kit. Oh, and of course you’ll need these.”

She slid a key and an ID across the desk. The ID was a disappointment. I’d taken about fifty pictures of myself until I found one that was passable, but in transferring it to the plastic, my face had been stretched out and had turned purple. My hair looked like some kind of mold.

“Your ID will get you in the front door. Simply tap it on the reader. Under no circumstances are you to give your ID to anyone else. Now, let’s look around.”

We got up and went back into the hallway. She waved her hand at a wall full of open mailboxes. There were more bulletin boards full of more notices for classes that hadn’t even started yet—reminders to get Oyster cards for the Tube, reminders to get certain books, reminders to get things at the library.

“The common room,” she said, opening a set of double doors. “You’ll be spending a lot of time here.”

This was a massive room, with a big fireplace. There was a television, a bunch of sofas, some worktables, and piles of cushions to sit on on the floor. Next to the common room, there was a study room full of desks, then another study room with a big table where you could have group sessions, then a series of increasingly tiny study rooms, some with only a single plush chair or a whiteboard on the wall.

From there, we went up three floors of wide, creaking steps. My room, number twenty-seven, was way bigger than I’d expected. The ceiling was high. There were large windows, each with a normal rectangular bit and an additional semicircle of glass on top. A thin, tan carpet had been laid on the floor. There was an amazing light hanging from the ceiling, big globes on a seven-pronged silver fixture. Best of all—there was a small fireplace. It didn’t look like it worked, but it was incredibly pretty, with a black iron grate and deep blue tiles. The mantel was large and deep, and there was a mirror mounted above it.

The thing that really got my attention, though, was the fact that there were three of everything. Three beds, three desks, three wardrobes, three bookshelves.

“It’s a triple,” I said. “I was only sent the name of one roommate.”

“That’s right. You’ll be living with Julianne Benton. She does swimming.”

That last part was delivered with a touch of annoyance. It was becoming very clear what Claudia’s priorities were.

She then showed me a tiny kitchen at the end of the hall. There was a water dispenser in the corner that had cold or boiling filtered water (“so you won’t need a kettle”). There was a small dishwasher and a very, very small fridge.

“That’s stocked daily with milk and soya milk,” Claudia said. “The fridge is for drinks only. Make sure to label your drinks. That’s what the pack of two hundred blank labels on your school supply list is for. There will be a selection of fruit and dried cereal here at all times, in case you get hungry.”

Then it was a tour of the bathroom, which was actually the most Victorian room of them all. It was massive, with a black-and-white tiled floor, marbled walls, and big beveled mirrors. There were wooden cubbies for our towels and bath supplies. For the first time, I could completely imagine all my future classmates here, all of us taking our showers and talking and brushing our teeth. I would be seeing my classmates dressed only in towels. They would see me without makeup, every day. That thought hadn’t occurred to me before. Sometimes you have to see the bathroom to know the hard reality of things.

I tried to dismiss this dawning fear as we returned to my room. Claudia rattled off rules to me for about another ten minutes. I tried to make mental notes of the ones to remember. We had to have our lights out by eleven, but we were allowed to use computers or small personal lights after that, provided that they didn’t bother our roommates. We could only put things up on our walls using something called Blu-Tack (also on the supply list). School blazers had to be worn to class, official assemblies, and dinner. We could leave them behind for breakfast and lunch.

“The dinner schedule is a bit strange tonight, since it’s just the prefects and you. The meal will be at three. I’ll send Charlotte to come get you. Charlotte is head girl.”

Prefects. I had learned this one. Student council types, but with superpowers. They who must be obeyed. Head girl was head of all girl prefects. Claudia left me, banging the door behind her. And then, it was just me. In the big room. In London.

Eight boxes were sitting on the floor. This was my new stuff, my clothes for the year: ten white dress shirts, three dark gray skirts, one gray and white striped blazer, one maroon tie, one gray sweater with the school crest on the breast, twelve pairs of gray kneesocks. In addition, there was another box of PE uniforms, for the daily physical education: two pairs of dark gray track pants with white stripes down the side, three pairs of shorts of the same material, five light gray T-shirts with WEXFORD written across the front, one maroon fleece track jacket with school crest, ten pairs of white sport socks. There were shoes as well—massive, clunky things that looked like Frankenstein shoes.

Obviously, I had to put on the uniform. The clothes were stiff and creased from packing. I yanked the pins from the shirt collars and pulled the tags from the skirt and blazer. I put on everything but the socks and shoes. Then I put on my headphones, because I find that a little music helps you adjust better.

There was no full-length mirror to gauge the effect. Using the mirror over the fireplace, I got a partial look. I still really needed to see the whole thing. That was going to require some ingenuity. I tried standing on the end of the middle bed, but it was too far over, so I pulled it into the center of the room and tried again. Now I had the complete picture. The result was a lot less gray than I’d imagined. My hair, which is a deep brown, looked black against the blazer, which I liked. The best part, without any question, was the tie. I’ve always liked ties, but it seemed like too much of a Statement to wear them. I pulled it loose, tugged it to the side, wrapped it around my head—I wanted to see every variation of the look.

Suddenly, the door opened. I screamed and knocked the headphones off my ears. They blasted music out into the room. I turned to see a tall girl standing in the doorway. She had red hair in an incredibly complicated yet casual-looking updo, and the creamy skin and heavy showers of golden freckles to match. What was most remarkable was her bearing. Her face was long, culminating in an adorable nub of a chin, which she held high. She was one of those people who actually walks with her shoulders back, like that’s normal. She was not, I noticed, wearing a uniform. She wore a blue and rose skirt with a soft gray T-shirt and a soft rose linen scarf tied loosely around her neck.

“Are you Aurora?” she asked.

She didn’t wait for me to confirm that I was this “Aurora” she was looking for.

“I’m Charlotte,” she said. “I’m here to take you to dinner.”

“Should I”—I pinched a bit of my uniform in the hope that this conveyed the verb—“change?”

“Oh, no,” she said cheerfully. “You’re fine. It’s just a handful of us, anyway. Come on!”

She watched me step awkwardly from the bed, grab my ID and key, and slip on my flip-flops.

3

O,” CHARLOTTE CHIRPED, AS I STUMBLED AND SLID over the cobblestones, “where are you from?”

I know you’re not supposed to judge people when you first meet them—but sometimes they give you lots of material to work with. For example, she kept looking sideways at my uniform. It would have been so easy for her to say, “Take a second and change,” but she hadn’t done that. I guess I could have demanded it, but I was cowed by her head girl status. Also, halfway down the stairs, she told me she was going to apply to Cambridge. Anyone who tells you their fancy college plans before they tell you their last name … these are people to watch out for. I once met a girl in line at Walmart who told me she was going to be on America’s Next Top Model. When I next saw that girl, she was crashing a shopping cart into an old lady’s car out in the parking lot. Signs. You have to read them.

I was terrified for a few minutes that they would all be like this, but reassured myself that it probably took a certain type to become head girl. I decided to deflect her attitude by giving a long, Southern answer. I come from people who know how to draw things out. Annoy a Southerner, and we will drain away the moments of your life with our slow, detailed replies until you are nothing but a husk of your former self and that much closer to death.

“New Orleans,” I said. “Well, not New Orleans, but right outside of. Well, like an hour outside of. My town is really small. It’s a swamp, actually. They drained a swamp to build our development. Well, attempting to drain a swamp is pretty pointless. They don’t really drain. You can dump as much fill on them as you want, but they’re still swamps. The only thing worse than building a housing development on a swamp is building it on an old Indian burial ground—and if there had been an old Indian burial ground around, the greedy morons who built our McMansions would have set up camp on it in a heartbeat.”

“Oh. I see.”

My answer only seemed to increase the intensity of the smug glee waves. My flip-flops made weird sucking noises on the stones.

“Your feet must be cold in those,” she said.

“They are.”

And that was the end of our conversation.

The refectory was in the old church, long deconsecrated. My hometown has three churches—all of them in prefab buildings, all filled with rows of plastic chairs. This was a Church—not large—but proper, made of stone, with buttresses and a small bell tower and narrow stained-glass windows. Inside, it was brightly lit by a number of circular black metal chandeliers. There were three long rows of wooden tables with benches, and a dais with a table where the old altar had been. There was also one of those raised side pulpits with its own set of winding stairs.

There was a small group of students sitting toward the front. Of course, none of them were in uniform. The sound of my flip-flops echoed off the walls, drawing their attention.

“Everyone,” Charlotte said, walking me up to the group, “this is Aurora. She’s from America.”

“Rory,” I said quickly. “Everyone calls me Rory. And I love uniforms. I’m going to wear mine all the time.”

“Right,” Charlotte said, before my quip could land. “And this is Jane, Clarissa, Andrew, Jerome, and Paul. Andrew is head boy.”

All the prefects were casually dressed, but in a dressy way. Like Charlotte, the other girls wore informal skirts. The guys wore polo shirts or T-shirts with logos I didn’t recognize, and looked like people in catalog ads. Out of all of them, Jerome looked the most rock-and-roll, with a slightly wild head of brown curls. He looked a lot like the guy I liked when I was in fourth grade, Doug Davenport. They both had sandy brown hair and wide noses and mouths. There was something easygoing about Jerome’s face. He looked like he smiled a lot.

“Come on, Rory!” Charlotte chirped. “This way.”

By now I resented almost everything that came out of Charlotte’s mouth. I definitely didn’t appreciate being beckoned like a pet. But I didn’t see any other course of action available, so I followed her.

To get to the food, we had to walk around the raised pulpit to a side door. We entered what had probably been the old offices or vestry. All of that had been ripped out to make a compact industrial kitchen and the customary row of steam trays. Tonight’s dinner consisted of a chicken casserole, vegetarian shepherd’s pie, a pan of roasted potatoes, green beans, and some rolls. There was a thin layer of golden grease over everything except the rolls, which was fine by me. I hadn’t eaten all day, and I had a stomach that could handle any amount of grease I could get inside it.

I took a little bit of everything as Charlotte looked over my plate. I met her eye and smiled.

When we returned, the conversation had rolled on. There was lots of stuff about “summer hols” and someone going to Kenya and someone else sailing. No one I knew went to Kenya for the summer. And I knew people with boats, but no one who “went sailing.” These people didn’t seem rich—at least, they weren’t a kind of rich I was familiar with. Rich meant stupid cars and a ridiculous house and huge parties with limos to New Orleans on your sixteenth birthday to drink nonalcoholic Hurricanes, which you swap out for real Hurricanes in the bathroom, and then you steal a duck, and then you throw up in a fountain. Okay, I was thinking of someone very specific in that case, but that was the general idea of rich that I currently held. Everyone at this table had a measure of maturity I wasn’t used to—gravitas, to use the SAT word.

“You’re from New Orleans?” Jerome asked, pulling me out of my thoughts.

“Yeah,” I said, hurrying to finish chewing. “Outside of.”

He looked like he was about to ask me something else, but Charlotte cut in.

“We have a prefects’ meeting now,” she informed me. “In here.”

I wasn’t quite done eating dessert, but I didn’t want to look like I was thrown by this.

“I’ll see you later,” I said, setting down my spoon.

Back in my room, I tried to choose a bed. I definitely didn’t want the one in the middle. I had to have some wall space. The only question was, did I go ahead and take the one by the super-cool fireplace (and therefore lay claim to the excellence of the mantel to store my stuff), or did I take the high road and choose the other side of the room?

I spent five minutes standing there, rationalizing the choice of taking the one by the fireplace. I decided it was fine for me to do this as long as I didn’t take the mantel right away. I would just take the bed and not touch the mantel for a while. Gradually, it would become mine.

That important issue resolved, I put on my headphones and turned my attention to unpacking boxes. One contained the sheets, pillows, blankets, and towels I’d had shipped over from home. It was strange to have these mundane house things show up here, in this building in the middle of London. After making up my bed, I tackled the suitcases, filling my wardrobe and the drawers. I put my photo collage of my friends from home above my desk, plus the pictures of my parents, of Uncle Bick and Cousin Diane. There was the ashtray shaped like pursed lips that I stole from our local barbecue place, Big Jim’s Pit of Love. I got out my collection of Mardi Gras beads and medallions and hung them from the end of my bed. Finally, I set up my computer and placed my three precious jars of Cheez Whiz safely on the shelf.

It was seven thirty.

I knelt on my bed and looked out the window. The sky was still bright and blue.

I wandered around the empty building for a while, eventually ending up in the common room. This would probably be the only time I had this room to myself, so I flopped on the sofa right in front of the television and turned it on. It was tuned to BBC One, and the news had just started. The first thing I noticed was the huge banner at the bottom of the screen that read RIPPER-LIKE MURDER IN EAST END. As I watched, through half-open eyes, I saw shots of the blocked-off street where the body was found. I saw footage of fluorescent-vested police officers holding back camera crews. Then it was back to the studio, where the announcer went on.

“Despite the fact that there was a CCTV camera pointed almost directly at the murder site, no footage of the crime was captured. Authorities say the camera malfunctioned. Questions are being raised about the maintenance of the CCTV system …”

Pigeons cooed outside the window. The building creaked and settled. I reached over and ran my hand over the heavy, slightly scratchy blue material on the sofa. I looked up at the bookcases built into the walls, stretching to the high ceiling. I had done it. This was actually London, this cold, empty building. Those pigeons were English pigeons. I had imagined this for so long, I didn’t quite know how to process the reality.

The words NEW RIPPER? flashed across the screen over a panoramic shot of Big Ben and Parliament. It was as if the news itself wanted to reassure me. Even Jack the Ripper himself had reappeared as part of the greeting committee.

4

WOKE UP THE NEXT MORNING TO FIND TWO STRANGERS in my room—one mom-looking type, and the other a girl with long, honey-blond hair wearing a sensible gray cashmere sweater and a pair of jeans. I rubbed my eyes quickly, reached around myself to make sure I was wearing something on both the top and bottom of my body, and discovered that I had slept in my uniform. I didn’t even remember going to bed. I just rested my eyes for a minute, and now it was morning. Jet lag had gotten me. I pulled the blanket up over me and made a noise that resembled “hello.”

“Oh, did we wake you?” the girl said. “We were trying not to.”

This is when I noticed the four suitcases, two laundry baskets, three boxes, and cello that were already in the room. These people had been politely creeping around for some time, trying to move in around my sleeping, uniformed body. Then I heard the racket in the hallway, the sounds of dozens of people moving in.

“Don’t worry,” the girl said. “My dad hasn’t come in. I don’t want to disturb you. You keep sleeping. Aurora, isn’t it?”

“Rory,” I said. “I fell asleep in my …”

I let the sentence go. There was no need to point out the obvious.

“Oh, it’s fine! It won’t be the last time, believe me. I’m Julianne, but everyone calls me Jazza.”

I introduced myself to Jazza’s mom, then headed down to the bathroom to brush my teeth and try to make myself generally more presentable.

The halls were swarming. How I’d slept through this invasion, I wasn’t entirely sure. Girls were squealing in delight at the sight of each other. There were hugs and air kisses, and lots of tight-lipped fights going on with parents who were trying not to make a scene. There were tears and good-byes. It was every human emotion happening at the exact same time. As I slithered down the hall, I could hear Claudia’s voice booming from three flights down, greeting people with “Call me Claudia! How was your trip? Good, good, good …”

I finally got to the bathroom and huddled by a window. Outside, it was a bright, clear morning. There were really only three or four parking spots in front of the school. The drivers had to take turns and keep their cars in nearly constant motion, dropping off a box or two and then continuing around to let the next person have a space. The same scene was going on across the square at the boys’ house.

I had planned much better entrances. I had scripted all kinds of greetings. I had gone over my best stories. But so far, I was zero for two. I brushed my teeth and rubbed my face with cold water, finger-combed my hair, and accepted that this was how I was going to meet my new roommate.

Since she was actually from England and able to come to school in a car, Jazza had way more stuff than me. Way more stuff. There were multiple suitcases, which her mom kept unpacking, piling the contents on the bed. There were boxes of books, about six dozen throw pillows, a tennis racquet, and a selection of umbrellas. Her sheets, towels, and blankets were all nicer than mine. She even brought curtains. And the cello. As for books, she easily had two hundred of them with her, maybe more. I looked over at my cardboard boxes and my decorative beads and ashtray and my one shelf of books.

“Can I help?” I asked.

“Oh …” Jazza spun around and looked at her things. “I think we’ve … I think we’ve brought it all in. My parents have a long drive back, you see, and … I’m just going to go out and say good-bye.”

“You’re done?”

“Yes, well, we’d been piling some things in the hall and bringing them in one at a time so we wouldn’t disturb you.”

Jazza went away for about twenty minutes, and when she returned, she was red-eyed and sniffly. I watched her unpack her things for a while. I wasn’t sure if I should offer my help again because the things looked kind of too personal. But I did anyway, and Jazza accepted, with many thanks. She told me I could use anything I liked, or borrow clothes, or blankets, or whatever I needed. “Just take it” was Jazza’s motto. She explained all the things that Claudia didn’t, like where and when you were allowed to use your phone (in your house and outside), what you did during the free periods (work, usually in the library or in your house).

“You lived with Charlotte before?” I asked as I made up her bed with a heavy quilt.

“You know Charlotte? She’s head girl now, so she gets her own room.”

“I had dinner with her last night,” I said. “She seems kind of … intense.”

Jazza snapped out a pillowcase.

“She’s all right, really. She’s under a lot of pressure from her family to get into Cambridge. I’d hate it if my family was like that. My parents just want me to do my best, and they’re quite happy wherever I want to go. Quite lucky, really.”

We worked right up until it was time to get ready for the Welcome Back to Wexford dinner. It wasn’t the cozy affair of the night before—the room was completely full. And this time, I wasn’t the only one in a uniform. It was gray blazers and maroon striped ties as far as the eye could see. The refectory, which had looked enormous when only a handful of us were in it the night before, had shrunk considerably. The line for food snaked all the way around to the front door. There was just enough room on the benches for everyone to squash in. There were a few more choices at dinner—roast beef, lentil roast, potatoes, several kinds of vegetables. The grease, I was happy to note, was still present.

When we emerged with our trays, Charlotte half stood and waved us over. She and Jazza exchanged some air kisses, which nauseated me a bit. Charlotte was sitting with the same group of prefects. Jerome moved over a few inches so I could sit down. We had barely applied butts to bench when Charlotte started in with the questions.

“How’s your schedule this year, Jaz?” she asked.

“Fine, thank you.”

“I’m taking four A levels, and the college I’m applying to at Cambridge requires an S level, plus I have to take the Oxbridge preparation class to get ready for the interview. So I’m going to be quite busy. Are you taking that class, the Oxbridge preparation class?”

“No,” Jazza said.

“I see. Well, it’s not strictly necessary. Where are you applying to?”

Jazza’s doelike eyes narrowed a bit, and she stabbed at her lentil roast.

“I’m still making up my mind,” she said.

“You don’t say much, do you?” Jerome asked me.

No one in my entire life had ever said this about me.

“You don’t know me yet,” I said.

“Rory was telling me she lives in a swamp,” Charlotte said.

“That’s right,” I said, turning up my accent a little. “These are the first shoes I’ve ever owned. They sure do pinch my feet.”

Jerome gave a little snort. Charlotte smiled sourly and turned the conversation back to Cambridge, a subject she seemed pathologically fixated on. People went right back to comparing notes about A levels, and I continued eating and observing.

The headmaster, Dr. Everest (it was immediately made clear to me that he was known to all as Mount Everest, which made sense, since he was about six foot seven), got up and gave us a little pep talk. Mostly it boiled down to the fact that it was autumn, and everyone was back, and while that was a great thing, people better not get cocky or misbehave or he’d personally kill us all. He didn’t actually say those words, but that was the subtext.

“Is he threatening us?” I whispered to Jerome.

Jerome didn’t turn his head, but he moved his eyes in my direction. Then he slipped a pen from his pocket and wrote the following on the back of his hand without even glancing down: Recently divorced. Also hates teenagers.

I nodded in understanding.

“As you are probably aware,” Everest droned on, “there’s been a murder nearby, which some people have taken to referring to as a new Ripper. Of course, there is no need to be concerned, but the police have asked us to remind all students to take extra care when leaving school grounds. I have now reminded you, and I trust no more need be said about that.”

“I feel warm and reassured,” I whispered. “He’s like Santa.”

Everest turned in our general direction for a moment, and we both stiffened and stared straight ahead. He chastised us a bit more, giving us some warnings about not staying out past our curfew, not smoking in uniform or in the buildings, and excessive drinking. Some drinking seemed to be expected. Laws were different here. You could drink at eighteen in general, but there was some weird side law about being able to order wine or beer with a meal, with an adult, at sixteen. I was still mulling this over when I noticed that the speech had ended and people were getting up and putting their trays on the racks.

I spent the night watching and occasionally assisting Jazza as she began the process of decorating her half of the room. There were curtains to be hung and posters and photos to be attached to the walls with Blu-Tack. She had an art print of Ophelia drowning in the pond, a poster from a band I’d never heard of, and a massive corkboard. The photos of her family and dogs were all in ornate frames. I made a mental note to get more wall stuff so my side didn’t look so naked.

What she didn’t display, I noticed, was a boxful of swimming medals.

“Holy crap,” I said, when she set them on the desk, “you’re like a fish.”

“Oh. Um. Well, I swim, you see.”

I saw.

“I won them last year. I wasn’t going to bring them, but … I brought them.”

She put the medals in her desk drawer.

“Do you play sports?” she asked.

“Not exactly,” I said. Which was really just my way of saying “hell, no.” We Deveauxs preferred to talk you to death, rather than face you in physical combat.

As she continued to unpack and I continued to stare at her, it occurred to me that Jazza and I were going to do this—this sitting-in-the-same-room thing—every night. For something like eight months. I had known my days of total privacy were over, but I hadn’t quite realized what that meant. All my habits were going to be on display. And Jazza seemed so straightforward and well-adjusted … What if I was a freak and had never realized it? What if I did weird things in my sleep?

I quickly dismissed these things from my mind.

5

IFE AT WEXFORD BEGAN PROMPTLY AT SIX ON Monday morning, when Jazza’s alarm went off seconds before mine. This was followed by a pounding on the door. The pounding went down the hall, as every door was knocked.

“Quick,” Jazza said, springing out of bed with a speed that was both alarming and unacceptable at this hour.

“I can’t run in the morning,” I said, rubbing my eyes.

Jazza was already putting on her robe and picking up her towel and bath basket.

“Quick!” she said again. “Rory! Quick!”

“Quick what?”

“Just get up!”

Jazza rocked from foot to foot anxiously as I pulled myself out of bed, stretched, fumbled around filling my bath basket.

“So cold in the morning,” I said, reaching for my robe. And it really was. Our room must have dropped about ten degrees in temperature from the night before.

“Rory …”

“Coming,” I said. “Sorry.”

I require a lot of things in the morning. I have very thick, long hair that can be tamed only by the use of a small portable laboratory’s worth of products. In fact—and I am ashamed of this—one of my big fears about coming to England was having to find new hair products. That’s shameful, I know, but it took me years to come up with the system I’ve got. If I use my system, my hair looks like hair. Without my system, it goes horizontal, rising inch by inch as the humidity increases. It’s not even curly—it’s like it’s possessed. Obviously, I needed shower gel and a razor (shaving in the group shower—I hadn’t even thought about that yet) and facial cleanser. Then I needed my flip-flops so I didn’t get shower foot.

I could feel Jazza’s increasing sense of despair traveling up my spine, but I was hurrying. I wasn’t used to having to figure all these things out and carry all my stuff at six in the morning. Finally, I had everything necessary and we trundled down the hall. At first, I wondered what the fuss was about. All the doors along the hall were closed, and there was little noise. Then we got to the bathroom and opened the door.

“Oh, no,” she said.

And then I understood. The bathroom was completely packed. Everyone from the hall was already in there. Each shower stall was already taken, and three or four people were lined up by each one.

“You have to hurry,” Jazza said. “Or this happens.”

It turns out there is nothing more annoying than waiting around for other people to shower. You resent every second they spend in there. You analyze how long they are taking and speculate on what they are doing. The people in my hall showered, on average, ten minutes each, which meant that it was over a half hour before I got in. I was so full of indignation about how slow they were that I had already preplanned my every shower move. It still took me ten minutes, and I was one of the last ones out of the bathroom.

Jazza was already in our room and dressed when I stumbled back in, my hair still soaked.

“How soon can you be ready?” she asked as she pulled on her school shoes. These were by far the worst part of the uniform. They were rubbery and black, with thick, nonskid soles. My grandmother wouldn’t have worn them. But then, my grandmother was Miss Bénouville 1963 and 1964, a title largely awarded to the fanciest person who entered. In Bénouville in 1963 and 1964, the definition of fancy was highly questionable. I’m just saying, my grandmother wears heeled slippers and silk pajamas. In fact, she’d bought me some silk pajamas to bring to school. They were vaguely transparent. I’d left them at home.

I was going to tell Jazza all of this, but I could see she was not in the mood for a story. So I looked at the clock. Breakfast was in twenty minutes.

“Twenty minutes,” I said. “Easy.”

I don’t know what happened, but getting ready was just a lot more complicated than I thought it would be. I had to get all the parts of my uniform on. I had trouble with my tie. I tried to put on some makeup, but there wasn’t a lot of light by the mirror. Then I had to guess which books I had to bring for my first classes, something I probably should have done the night before.

Long story short, we left at 7:13. Jazza spent the entire wait sitting on her bed, eyes growing increasingly wide and sad. But she didn’t just leave me, and she never complained.

The refectory was packed, and loud. The bonus of being so late was that most people had gone through the food line. We were up there with the few guys who were going back for seconds. I grabbed a cup of coffee first thing and poured myself an impossibly small glass of lukewarm juice. Jazza took a sensible selection of yogurt, fruit, and whole-grain bread. I was in no mood for that kind of nonsense this morning. I helped myself to a chocolate doughnut and a sausage.

“First day,” I explained to Jazza when she stared at my plate.

It became clear that it was going to be tricky to find a seat. We found two at the very end of one of the long tables. For some reason, I looked around for Jerome. He was at the far end of the next table over, deep in conversation with some girls from the first floor of Hawthorne. I turned to my plate of fats. I realized how American this made me seem, but I didn’t particularly care. I had just enough time to stuff some food down my throat before Mount Everest stood up at his dais and told us that it was time to move along. Suddenly, everyone was moving, shoving last bits of toast and final gulps of juice into their mouths.

“Good luck today,” Jazza said, getting up. “See you at dinner.”

The day was ridiculous.

In fact, the situation was so serious I thought they had to be joking—like maybe they staged a special first day just to psych people out. I had one class in the morning, the mysteriously named “Further Maths.” It was two hours long and so deeply frightening that I think I went into a trance. Then I had two free periods, which I had laughingly dismissed when I first saw them. I spent them feverishly trying to do the problem sets.

At a quarter to three, I had to run back to my room and change into shorts, sweatpants, a T-shirt, a fleece, and these shin pads and spiked shoes that Claudia had given to me. From there, I had to get three streets over to the field we shared with a local university. If cobblestones are a tricky walk in flip-flops, they are your worst nightmare in spiked shoes and with big, weird pads on your shins. I arrived to find that people (all girls) were (wisely) putting on their spiked shoes and pads there, and that everyone was wearing only shorts and T-shirts. Off came the sweatpants and fleece. Back on with the weird pads and spikes.

Charlotte, I was dismayed to find, was in hockey as well. So was my neighbor Eloise. She lived across the hall from us in the only single. She had a jet-black pixie cut and a carefully covered arm of tattoos. She had a huge air purifier in her room, which had gotten some kind of special clearance (since we couldn’t have appliances). Somehow she got a doctor to say she had terrible allergies, hence she would need the purifier and her own space. In reality, she used the filter to hide the fact that she spent most of her free time smoking cigarette after cigarette and blowing smoke directly into the purifier. Eloise spoke fluent French because she lived there a few months out of every year. As for the smoking, she never actually said, “It’s a French thing,” but it was implied. Eloise looked as dismayed as I did about the hockey. The rest looked grimly determined.

Most people had their own hockey sticks, but for those of us who didn’t, they were distributed. Then we stood in line, where I shivered.

“Welcome to hockey!” Claudia boomed. “Most of you have played hockey before—we’re just going to run through some basics and drills to get back into things.”

It became pretty obvious pretty quickly that “most of you have played hockey before” actually meant “every single one of you except for Rory has played hockey before.” No one but me needed the primer on how to hold the stick, which side of the stick to hit the ball with (the flat one, not the roundy one). No one needed to be shown how to run with the stick or how to hit the ball. The total amount of time given to these topics was five minutes. Claudia gave us all a once-over to make sure we were properly dressed and had everything we needed. She stopped at me.

“Mouth guard, Aurora?”

Mouth guard. Some lump of plastic she had left by my door during the morning. I’d forgotten it.

“Tomorrow,” she said. “For now, you’ll just watch.”

So I sat on the grass on the side of the field while everyone else put their plastic lumps in their mouths, turning the space previously full of teeth into alarming leers of bright pink and neon blue. They ran up and down the field, passing the ball back and forth to each other. Claudia paced alongside the entire time, barking commands I didn’t understand. The process of hitting the ball looked straightforward enough from where I was, but these things never are.

“Tomorrow,” she said to me when the period was over and everyone left the field. “Mouth guard. And I think we’ll start you in goal.”

Goal sounded like a special job. I didn’t want a special job, unless that special job involved sitting on the side under a pile of blankets.

Then we all ran back to Hawthorne—and I mean ran, literally—where everyone was once again competing for the showers. I found Jazza back in our room, dry and dressed. Apparently, there were showers at the pool.

Dinner featured some baked potatoes, some soup, and something called a “hot pot,” which looked like beef and potatoes, so I took that. Our groupings were becoming more predictable, and I was starting to understand the dynamic. Jerome, Andrew, Charlotte, and Jazza had all been friends last year. Three of them had become prefects; Jazza had not. Jazza and Charlotte didn’t get along. I attempted to join in the conversations, but found I didn’t have much to share until the topic came around to the Ripper, when I dove in with a little family history.

“People love murderers,” I said. “My cousin Diane used to date a guy on death row in Texas. Well, I don’t know if they were dating, but she used to write him letters all the time, and she said they were in love and going to get married. But it turns out he had, like, six girlfriends, so they broke up and she opened her Healing Angel Ministry …”

I had them now. They had all slowed their eating and were looking over.

“See,” I said, “Cousin Diane runs the Healing Angel Ministry out of her living room. Well, and also her backyard. She has a hundred sixty-one statues of angels in her backyard. Plus she has eight hundred seventy-five angel figurines, dolls, and pictures in the house. And people go to her for angel counseling.”

“Angel counseling?” Jazza repeated.

“Yep. She plays New Age music and has you close your eyes, and then she channels some angels. She tells you their names and what colors their auras are and what they’re trying to tell you.”

“Is your cousin … insane?” Jerome asked.

“I don’t think she’s insane,” I said, digging into my hot pot. “This one time, I was over at her house. When I get bored there, I channel angels, so she feels like she’s doing a good job. I go like this …”

I took a big, deep breath to prepare for my angel voice. Unfortunately, I did so while taking a bite of the hot pot. A chunk of beef slipped down my throat. I felt it stop somewhere just under my chin. I tried to clear my throat, but nothing happened. I tried to cough. Nothing. I tried to speak. Nothing.

Everyone was watching me. Maybe they thought this was part of the imitation. I pushed away from the table a bit and tried to cough harder, then harder still, but my efforts made no difference. My throat was stopped. My eyes watered so much that everything went all runny. I felt a rush of adrenaline … then everything went white for a second, completely, totally, brilliantly white. The entire refectory vanished and was replaced by this endless, paperlike vista. I could still feel and hear, but I seemed to be somewhere else, somewhere without air, somewhere where everything was made of light. Even when I closed my eyes, it was there. Someone was yelling that I was choking, but the words sounded like they were far away.

And then arms were around my middle. There was a fist jabbing into the soft tissue under my rib cage. I was jerked up, over and over, until I felt a movement. The refectory dropped back into place as the beef launched itself out of me and flew off in the direction of the setting sun and a rush of air came into my lungs.

“Are you all right?” someone said. “Can you speak? Try to speak.”

“I…”

I could speak, and that was all I felt like saying at the moment. I fell against the bench and put my head on the table. There was a pounding of blood in my ears. I looked deep into the markings of the wood and examined the silverware up close. My face was wet with tears I didn’t remember crying. The refectory had gone totally silent. At least, I think it was silent. My heart was drumming in my ears so loudly that it drowned out anything else. Someone was telling people to move back and give me air. Someone else was helping me up. Then some teacher (I think it was a teacher) was in front of me, and Charlotte was there as well, poking her big red head into the frame.

“I’m fine,” I said hoarsely. I wasn’t fine. I just wanted to leave, to go somewhere and cry. I heard the teacher person say, “Charlotte, take her to the san.” Charlotte attached herself to my right arm. Jazza attached herself to my left.

“I’ve got her,” Charlotte said crisply. “You can continue eating.”

“I’m coming,” Jazza shot back.

“I can walk,” I croaked.

Neither one of them loosened their grip, which was probably for the best, because it turned out my ankles and knees had gone all rubbery. They escorted me down the center aisle, between the long benches, as people turned and watched me go. Considering that the refectory was an old church, our exit probably looked like the end of a very unusual wedding ceremony—me being dragged down the aisle by my two brides.

6

SAN WAS THE SANATORIUM—BASICALLY, THE nurse’s office. But since Wexford was a boarding school, there was a little more to it than just an office. There were a few rooms, including one full of beds where the really sick people could stay. The nurse on duty, Miss Jenkins, gave me a once-over. She took my pulse and listened to my chest with a stethoscope and generally made assurances that I had not choked to death. She told Charlotte to take me back to my house and make sure I relaxed with a nice cup of tea. Once at home, Jazza made it clear that she was taking over. Charlotte turned on her heel in a practiced way. Her head bobbed when she walked. You could see her updo bounce up and down.

I kicked off my shoes and curled up in bed. Though the offending beef was long gone, I rubbed at my throat where it had been. The feeling was still with me, that feeling of having no air, of not being able to speak.

“I’ll make you some tea,” Jazza said.

She went off and made me the tea, and I sat in my bed and gripped my throat. Though my heart had slowed to normal, there was still a tremor running through me. I picked up my phone to call my parents, but then tears started trickling from my eyes, so I shoved the phone under my blanket. I bunched myself up and took a few deep breaths. I needed to get this under control. I was fine. Nothing had happened to me. I couldn’t be the pathetic, weepy, useless roommate. I had wiped my face clean and was smiling, kind of, when Jazza returned. She handed me the tea, went to her desk and got something, then sat on the floor by my bed.

“When I have a bad night,” she said, “I look at my dogs.”

She held out a picture of two beautiful dogs—one smallish golden retriever and one very large black Lab. In the picture, Jazza was squeezing the dogs. In the background, there were green rolling hills and some kind of large white farmhouse. It looked too idyllic for anyone to actually live there.

“The golden one is Belle, and the big, soppy one is Wiggy. Wiggy sleeps in my bed at night. And that’s our house in the back.”

“Where do you live?”

“In a village in Cornwall outside of St. Austell. You should come sometime. It’s really beautiful.”

I slowly sipped my tea. It hurt my throat at first, but then the heat felt good. I reached over and got my computer and pulled up some pictures of my own. First, I showed her Cousin Diane, because I had just been talking about the angels. I had a very good picture of her standing in her living room, surrounded by figurines.

“You weren’t lying,” Jazza said, leaning on the bed and looking closely. “There must be hundreds of them!”

“I don’t lie,” I said. I flicked next to a picture of Uncle Bick.

“I can see the resemblance,” Jazza said.

She was right. Of all the members of my family, I looked most like him—dark hair, dark eyes, a very round face. Except I’m a girl, and I have fairly ample boobs and hips, and he’s a man in his thirties with a beard. But if I wore a fake black beard and a baseball cap that said BIRDBRAIN, I think people would immediately know we were related.

“He looks very young.”

“Oh, this is an old picture,” I said. “I think this was taken around the time I was born. It’s his favorite picture, so it’s the one I brought.”

“This is his favorite? It looks like it was taken in a supermarket.”

“See that woman kind of hiding behind the pile of cans of cranberry sauce?” I asked. “That’s Miss Gina. She runs the local Kroger—that’s a grocery store. Uncle Bick’s been courting her for nineteen years. This is the only picture of the two of them, which is why he likes it.”

“What do you mean, ‘courting her for nineteen years’?” Jazza asked.

“See, my uncle Bick—he’s really nice, by the way—he runs an exotic bird store called A Bird in the Hand. His life is pretty much all birds. He’s been in love with Miss Gina since high school, but he doesn’t really know how to talk to girls, so he’s just been … staying around her since then. He just tends to go where she goes.”

“Isn’t that stalking?” Jazza said.

“Legally, no,” I replied. “I asked my parents this when I was little. What he does is creepy and socially awkward, but it’s not actually stalking. I think the worst it ever got was the time he left a collage of bird feathers on the windshield of her car …”

“But doesn’t he scare her?”

“Miss Gina?” I laughed. “No. She has a whole bunch of guns.”

I made that last part up just to entertain Jazza. I don’t think Miss Gina has any guns. I mean, she might. Lots of people in our town do. But it’s hard to explain to someone who doesn’t know him that Uncle Bick is actually harmless. You only have to see him with a miniature parrot to know this man couldn’t harm anything or anyone. Also, my mom would have him locked up in a flash if she thought he was actually up to something.

“I feel quite boring next to you,” Jazza said.

“Boring?” I repeated. “You’re English.”

“Yes. That’s not very interesting.”

“You … have a cello! And dogs! And you live in a farmhouse … kind of thing. In a village.”

“Again, that’s not very exciting. I love our village, but we’re all quite … normal.”

“In our town,” I said solemnly, “that would make you a kind of god.”

She laughed a little.

“I’m not kidding,” I said. “My family—I mean, my mom and dad and me—are the normal people in town. For example, there’s my uncle Will. He owns eight freezers.”

“That doesn’t sound so odd.”

“Seven of them are on the second floor, in a spare bedroom. He also doesn’t believe in banks, so he keeps his money in peanut butter jars in the closet. When I was little, he used to give me empty jars as gifts so I could collect money and watch it grow.”

“Oh,” she said.

“Then there’s Billy Mack, who started his own religion out of his garage, the People’s Church of Universal People. Even my grandmother, who is almost normal, poses for a formal photograph each year in a slightly revealing dress and mails said photo to all her friends and family, including my dad, who shreds it without opening the envelope. This is what my town is like.”

Jazza was quiet for a moment.

“I very much want to go to your town,” she finally said. “I’m always the boring one.”

From the way she said it, I got the impression that this was something Jazza felt deeply.

“You don’t seem boring to me,” I said.

“You don’t really know me yet. And I don’t have all of this.”

She waved at my computer to indicate my life in general.

“But you have all of this,” I said. I waved my arms too in an attempt to indicate Wexford and England in general, but it looked more like I was shaking invisible pom-poms.

I sipped my tea. My throat was feeling more normal now. Every once in a while, I would remember what it was like not being able to breathe and that strange whiteness …

“You don’t like Charlotte,” I said, blinking hard. I had to say something to get all that stuff out of my head. It was probably a little abrupt and rude.

Jazza’s mouth twitched. “She’s … competitive.”

“That seems like a polite word for what she is. Is that how she got to be head girl?”

“Well …” Jazza picked at my duvet for a moment, pinching up little bits of fabric and letting them go. “The house master or mistress chooses the prefects. Claudia made her head girl, which she deserves, I suppose …”

“Did you apply?” I asked.

“You don’t apply. You just get chosen. You don’t have to be unpleasa—I mean, I like Jane a lot. And Jerome and Andrew are good friends of mine. It’s just Charlotte, well … everything was a bit of a competition. Who studied more. Who was better at sport. Who dated whom.”

Aside from being the kind of person who used “whom” correctly while gossiping, Jazza was also the kind of person who seemed pained about speaking badly about another person. She squeezed up her fists a few times, as if gossip required physical pressure to leave her body.

“When we first arrived, I was seeing Andrew for a while,” Jazza said. “Charlotte had no interest in him until I did. But she could never let something like that go. She dated him after we broke up, then she broke up with him instantly, but … she has to … well, I don’t have to live with her anymore. I live with you.”

Jazza let out a light sigh, like a demon had been released.

“Do you date someone now?” I asked.

“No,” she said. “I… no. Maybe at uni. This year, all I’m concentrating on is exams. What about you?”

I mentally paged over the short and terrible history of my love life in Bénouville. My life had been about school too. It had taken a lot of work to get into Wexford. And I wasn’t sure if a few make-outs with friends in the Walmart parking lot constituted dating. Now that I thought about it, maybe I had been waiting too—waiting to come here. In my imagination, I’d always envisioned some figure by my side at Wexford. That prospect seemed unlikely after my display tonight, unless English people were really into people who could eject food from their throats at high velocity.

“Me too,” I said. “Studying. That’s what this year is about.”

Sure, we both meant that to an extent. I had come to study. I did have to apply to college while I was here. I really was going to read those books on my shelf, and I really was excited about the prospect of my classes, even if it appeared that said classes would probably kill me. But neither of us was telling the entire truth on that count, and we both knew it. There was a look, an almost audible click as we bonded over this mutual lie. Jazza and I got each other. Perhaps she was the figure by my side that I’d always imagined.

7

NEXT DAY, IT RAINED.

I began the day with double French. At home, French was one of my strongest subjects. Louisiana has French roots. Lots of things in New Orleans have French names. I thought French was going to be my best subject, but this illusion was quickly shattered when our teacher, Madame Loos, came in rattling off French like an annoyed Parisian. I went right from there to double English Literature, where we were informed that we would be working on the period from 1711 to 1847. What alarmed me about that was its specificity. I didn’t even think it was that the material was necessarily much harder than what I had in school at home—it was more that they were so adult about it. The teachers spoke with a calm assurance, like we were all fully qualified academics, and everyone acted accordingly. We would be reading Pope, Swift, Johnson, Pepys, Fielding, Coleridge, Wordsworth, Richardson, Austen, the Brontës, Dickens … the list went on and on.

Then I had lunch. It continued to rain.

After lunch I had a free period, which I spent having a panic attack in my room.

I thought for sure that they would cancel hockey. In fact, I asked someone what we did when our sports hour was canceled because of the weather, and she just laughed. So it was off to the field in my tiny shorts and fleece, with my mouth guard, of course. The night before I had to put it in a mug of boiling water to make it soft and mold it to my teeth. That was a pleasant feeling. At the field, I was greeted with the goal-keeper equipment. I’m not sure who designed the field hockey goalie’s uniform, but I’d guess it was someone who decided to merge his or her love of safety with a truly macabre sense of humor. There were swollen blue pads for my shins that were easily twice the width of my leg. There was another set for the upper thigh. The arm pads were like massively overinflated floaties. There were chest pads with an oversized jersey to go over them and huge, cartoonish shoe objects for my feet. Then there was a helmet with a face guard. The overall effect was like one of those bodysuits you can get to make you look like a sumo wrestler—but far less elegant and human. It took me fifteen minutes to get all this stuff on, and then I had to figure out how to walk in it. The other goalie, a girl named Philippa, got hers on in half the time and was running, wide-legged, onto the field while I was still trying to get the shoes on.

Once I did that, my job was to stand in the goal while people hit hockey balls at me. Claudia kept yelling at me to repel this onslaught using my feet, but sometimes she would tell me to use my arms. All the while, rain poured onto the helmet and streamed down my face. I couldn’t move, so the balls just hit me. When it was all over, Charlotte came up to me as I was trying to get out of the padding.

“If you want some help,” she said, “I’ve been playing for a long time. I’d be happy to run drills with you.”

What was especially painful about this was that I think she meant it.

At home, I had the third-highest GPA in my class, and literature was my thing. I would do the reading for English first. The essay I had to read was called “An Essay on Criticism” by Alexander Pope.

The first challenge was that the essay was, in fact, a very long poem in “heroic couplets.” If something is called an essay, it should be an essay. I read it twice. A few lines stood out, like “For fools rush in where angels fear to tread.” Now I knew where that came from. But I still didn’t really know what it was about. I looked online first, but I quickly realized I had to up my game a little here at Wexford. This was a place for some book learning. So I went to the library.