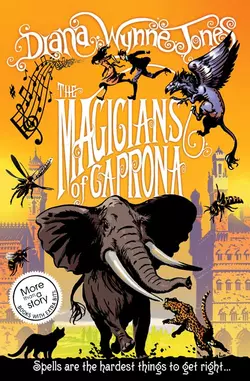

The Magicians of Caprona

The Magicians of Caprona

Diana Wynne Jones

Glorious new rejacket of a Diana Wynne Jones favourite, featuring Chrestomanci – now a book with extra bits!The Dukedom of Caprona is a place where music is enchantment and spells are as slippery as spaghetti. The magical business is run by two families - the Montanas and the Petrocchis - and they are deadly rivals. So when all the spells start going wrong, they naturally blame each other.Chrestomanci suspects an evil enchanter; others say it is a White Devil. Or maybe a different kind of magic is needed to save Caprona…

Illustrated by Tim Stevens

DEDICATION (#ulink_4d91aee6-bd20-5c9e-8593-ac672e5219a6)

For John

CONTENTS

Cover (#u4d78c723-3375-570a-86c7-959939354eb4)

Title Page (#ud4111707-3282-579e-b7a2-a94944dd4ec3)

Dedication (#u1202d2b1-742f-536c-9bd2-56768e94316f)

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Author’s Note

Other Works

Copyright

About the Publisher

CHAPTER ONE (#u8bb0f7ee-043a-575e-b2b1-f412da8ddde9)

Spells are the hardest thing in the world to get right. This was one of the first things the Montana children learnt. Anyone can hang up a charm, but when it comes to making that charm, whether it is written or spoken or sung, everything has to be just right, or the most impossible things happen.

An example of this is young Angelica Petrocchi, who turned her father bright green by singing a wrong note. It was the talk of all Caprona – indeed of all Italy – for weeks.

The best spells still come from Caprona, in spite of the recent troubles, from the Casa Montana or the Casa Petrocchi. If you are using words that really work, to improve reception on your radio or to grow tomatoes, then the chances are that someone in your family has been on a holiday to Caprona and brought the spell back. The Old Bridge in Caprona is lined with little stone booths, where long coloured envelopes, scrips and scrolls hang from strings like bunting.

You can get spells there from every spell-house in Italy. Each spell is labelled as to its use and stamped with the sign of the house which made it. If you want to find out who made your spell, look among your family papers. If you find a long cherry-coloured scrip stamped with a black leopard, then it came from the Casa Petrocchi. If you find a leaf-green envelope bearing a winged horse, then the House of Montana made it. The spells of both houses are so good that ignorant people think that even the envelopes can work magic. This, of course, is nonsense. For, as Paolo and Tonino Montana were told over and over again, a spell is the right words delivered in the right way.

The great houses of Petrocchi and Montana go back to the first founding of the State of Caprona, seven hundred years or more ago. And they are bitter rivals. They are not even on speaking terms. If a Petrocchi and a Montana meet in one of Caprona’s narrow golden-stone streets, they turn their eyes aside and edge past as if they were both walking past a pig-sty. Their children are sent to different schools and warned never, ever to exchange a word with a child from the other house.

Sometimes, however, parties of young men and women of the Montanas and the Petrocchis happen to meet when they are strolling on the wide street called the Corso in the evenings. When that happens, other citizens take shelter at once. If they fight with fists and stones, that is bad enough, but if they fight with spells, it can be appalling.

An example of this is when the dashing Rinaldo Montana caused the sky to rain cowpats on the Corso for three days. It created great distress among the tourists.

“A Petrocchi insulted me,” Rinaldo explained, with his most flashing smile. “And I happened to have a new spell in my pocket.”

The Petrocchis unkindly claimed that Rinaldo had misquoted his spell in the heat of the battle. Everyone knew that all Rinaldo’s spells were love-charms.

The grown-ups of both houses never explained to the children just what had made the Montanas and the Petrocchis hate one another so. That was a task traditionally left to the older brothers, sisters and cousins. Paolo and Tonino were told the story repeatedly, by their sisters Rosa, Corinna and Lucia, by their cousins Luigi, Carlo, Domenico and Anna, and again by their second-cousins Piero, Luca, Giovanni, Paula, Teresa, Bella, Angelo and Francesco. They told it themselves to six smaller cousins as they grew up. The Montanas were a large family.

Two hundred years ago, the story went, old Ricardo Petrocchi took it into his head that the Duke of Caprona was ordering more spells from the Montanas than from the Petrocchis, and he wrote old Francesco Montana a very insulting letter about it. Old Francesco was so angry that he promptly invited all the Petrocchis to a feast. He had, he said, a new dish he wanted them to try. Then he rolled Ricardo Petrocchi’s letter up into long spills and cast one of his strongest spells over it. And it turned into spaghetti. The Petrocchis ate it greedily and were all taken ill, particularly old Ricardo – for nothing disagrees with a person so much as having to eat his own words. He never forgave Francesco Montana, and the two families had been enemies ever since.

“And that,” said Lucia, who told the story oftenest, being only a year older than Paolo, “was the origin of spaghetti.”

It was Lucia who whispered to them all the terrible heathen customs the Petrocchis had: how they never went to Mass or confessed; how they never had baths or changed their clothes; how none of them ever got married but just – in an even lower whisper – had babies like kittens; how they were apt to drown their unwanted babies, again like kittens, and had even been known to eat unwanted uncles and aunts; and how they were so dirty that you could smell the Casa Petrocchi and hear the flies buzzing right down the Via Sant’ Angelo.

There were many other things besides, some of them far worse than these, for Lucia had a vivid imagination. Paolo and Tonino believed every one, and they hated the Petrocchis heartily, though it was years before either of them set eyes on a Petrocchi. When they were both quite small, they did sneak off one morning, down the Via Sant’ Angelo almost as far as the New Bridge, to look at the Casa Petrocchi. But there was no smell and no flies buzzing to guide them, and their sister Rosa found them before they found it. Rosa, who was eight years older than Paolo and quite grown-up even then, laughed when they explained their difficulty, and good-naturedly took them to the Casa Petrocchi. It was in the Via Cantello, not the Via Sant’ Angelo at all.

Paolo and Tonino were most disappointed in it. It was just like the Casa Montana. It was large, like the Casa Montana, and built of the same golden stone of Caprona, and probably just as old. The great front gate was old knotty wood, just like their own, and there was even the same golden figure of the Angel on the wall above the gate. Rosa told them that both Angels were in memory of the Angel who had come to the first Duke of Caprona bringing a scroll of music from Heaven – but the boys knew that. When Paolo pointed out that the Casa Petrocchi did not seem to smell much, Rosa bit her lip and said gravely that there were not many windows in the outside walls, and they were all shut.

“I expect everything happens round the yard inside, just like it does in our Casa,” she said. “Probably all the smelling goes on in there.”

They agreed that it probably did, and wanted to wait to see a Petrocchi come out. But Rosa said she thought that would be most unwise, and pulled them away. The boys looked over their shoulders as she dragged them off and saw that the Casa Petrocchi had four golden-stone towers, one at each corner, where the Casa Montana only had one, over the gate.

“It’s because the Petrocchis are show-offs,” Rosa said, dragging. “Come on.”

Since the towers were each roofed with a little hat of red pantiles, just like their own roofs or the roofs of all the houses in Caprona, Paolo and Tonino did not think they were particularly grand, but they did not like to argue with Rosa. Feeling very let down, they let her drag them back to the Casa Montana and pull them through their own large knotty gate into the bustling yard beyond. There Rosa left them and ran up the steps to the gallery, shouting, “Lucia! Lucia, where are you? I want to talk to you!”

Doors and windows opened into the yard all round, and the gallery, with its wooden railings and pantiled roof, ran round three sides of the yard and led to the rooms on the top floor. Uncles, aunts, cousins large and small, and cats were busy everywhere, laughing, cooking, discussing spells, washing, sunning themselves or playing. Paolo gave a sigh of contentment and picked up the nearest cat.

“I don’t think the Casa Petrocchi can be anything like this inside.”

Before Tonino could agree, they were swooped on lovingly by Aunt Maria, who was fatter than Aunt Gina, but not as fat as Aunt Anna. “Where have you been, my loves? I’ve been ready for your lessons for half an hour or more!”

Everyone in the Casa Montana worked very hard. Paolo and Tonino were already being taught the first rules for making spells. When Aunt Maria was busy, they were taught by their father, Antonio. Antonio was the eldest son of Old Niccolo, and would be head of the Casa Montana when Old Niccolo died. Paolo thought this weighed on his father. Antonio was a thin, worried person who laughed less often than the other Montanas. He was different. One of the differences was that, instead of letting Old Niccolo carefully choose a wife for him from a spell-house in Italy, Antonio had gone on a visit to England and come back married to Elizabeth. Elizabeth taught the boys music.

“If I’d been teaching that Angelica Petrocchi,” she was fond of saying, “she’d never have turned anything green.”

Old Niccolo said Elizabeth was the best musician in Caprona. And that, Lucia told the boys, was why Antonio got away with marrying her. But Rosa told them to take no notice. Rosa was proud of being half English.

Paolo and Tonino were probably prouder to be Montanas. It was a grand thing to know you were born into a family that was known world-wide as the greatest spell-house in Europe – if you did not count the Petrocchis. There were times when Paolo could hardly wait to grow up and be like his cousin, dashing Rinaldo. Everything came easily to Rinaldo. Girls fell in love with him, spells dripped from his pen. He had composed seven new charms before he left school. And these days, as Old Niccolo said, making a new spell was not easy. There were so many already. Paolo admired Rinaldo desperately. He told Tonino that Rinaldo was a true Montana.

Tonino agreed, because he was more than a year younger than Paolo and valued Paolo’s opinions, but it always seemed to him that it was Paolo who was the true Montana. Paolo was as quick as Rinaldo. He could learn without trying spells which took Tonino days to acquire. Tonino was slow. He could only remember things if he went over them again and again. It seemed to him that Paolo had been born with an instinct for magic which he just did not have himself.

Tonino was sometimes quite depressed about his slowness. Nobody else minded in the least. All his sisters, even the studious Corinna, spent hours helping him. Elizabeth assured him he never sang out of tune. His father scolded him for working too hard, and Paolo assured him that he would be streets ahead of the other children when he went to school. Paolo had just started school. He was as quick at ordinary lessons as he was at spells.

But when Tonino started school, he was just as slow there as he was at home. School bewildered him. He did not understand what the teachers wanted him to do. By the first Saturday he was so miserable that he had to slip away from the Casa and wander round Caprona in tears. He was missing for hours.

“I can’t help being quicker than he is!” Paolo said, almost in tears too.

Aunt Maria rushed at Paolo and hugged him. “Now, now, don’t you start too! You’re as clever as my Rinaldo, and we’re all proud of you.”

“Lucia, go and look for Tonino,” said Elizabeth. “Paolo, you mustn’t worry so. Tonino’s soaking up spells without knowing he is. I did the same when I came here. Should I tell Tonino?” she asked Antonio. Antonio had hurried in from the gallery. In the Casa Montana, if anyone was in distress, it always fetched the rest of the family.

Antonio rubbed his forehead. “Perhaps. Let’s go and ask Old Niccolo. Come on, Paolo.”

Paolo followed his thin, brisk father through the patterns of sunlight in the gallery and into the blue coolness of the Scriptorium. Here his other two sisters, Rinaldo and five other cousins, and two of his uncles, were all standing at tall desks copying spells out of big leather-bound books. Each book had a brass lock on it so that the family secrets could not be stolen. Antonio and Paolo tiptoed through. Rinaldo smiled at them without pausing in his copying. Where other pens scratched and paused, Rinaldo’s raced.

In the room beyond the Scriptorium, Uncle Lorenzo and Cousin Domenico were stamping winged horses on leaf-green envelopes. Uncle Lorenzo looked keenly at their faces as they passed and decided that the trouble was not too much for Old Niccolo alone. He winked at Paolo and threatened to stamp a winged horse on him.

Old Niccolo was in the warm mildewy library beyond, consulting over a book on a stand with Aunt Francesca. She was Old Niccolo’s sister, and therefore really a great-aunt. She was a barrel of a lady, twice as fat as Aunt Anna and even more passionate than Aunt Gina. She was saying passionately, “But the spells of the Casa Montana always have a certain elegance. This is graceless! This is—”

Both round old faces turned towards Antonio and Paolo. Old Niccolo’s face, and his eyes in it, were round and wondering as the latest baby’s. Aunt Francesca’s face was too small for her huge body, and her eyes were small and shrewd. “I was just coming,” said Old Niccolo. “I thought it was Tonino in trouble, but you bring me Paolo.”

“Paolo’s not in trouble,” said Aunt Francesca.

Old Niccolo’s round eyes blinked at Paolo. “Paolo,” he said, “what your brother feels is not your fault.”

“No,” said Paolo. “I think it’s school really.”

“We thought that perhaps Elizabeth could explain to Tonino that he can’t avoid learning spells in this Casa,” Antonio suggested.

“But Tonino has ambition!” cried Aunt Francesca.

“I don’t think he does,” said Paolo.

“No, but he is unhappy,” said his grandfather. “And we must think how best to comfort him. I know.” His baby face beamed. “Benvenuto.”

Though Old Niccolo did not say this loudly, someone in the gallery immediately shouted, “Old Niccolo wants Benvenuto!” There was running and calling down in the yard. Somebody beat on a water butt with a stick. “Benvenuto! Where’s that cat got to? Benvenuto!”

Naturally, Benvenuto took his time coming. He was boss cat at the Casa Montana. It was five minutes before Paolo heard his firm pads trotting along the tiles of the gallery roof. This was followed by a heavy thump as Benvenuto made the difficult leap down, across the gallery railing on to the floor of the gallery. Shortly, he appeared on the library windowsill.

“So there you are,” said Old Niccolo. “I was just going to get impatient.”

Benvenuto at once shot forward a shaggy black hind leg and settled down to wash it, as if that was what he had come there to do.

“Ah no, please,” said Old Niccolo. “I need your help.”

Benvenuto’s wide yellow eyes turned to Old Niccolo. He was not a handsome cat. His head was unusually wide and blunt, with grey gnarled patches on it left over from many, many fights. Those fights had pulled his ears down over his eyes, so that Benvenuto always looked as if he were wearing a ragged brown cap. A hundred bites had left those ears notched like holly leaves. Just over his nose, giving his face a leering, lop-sided look, were three white patches. Those had nothing to do with Benvenuto’s position as boss cat in a spell-house. They were the result of his partiality for steak. He had got under Aunt Gina’s feet when she was cooking, and Aunt Gina had spilt hot fat on his head. For this reason, Benvenuto and Aunt Gina always pointedly ignored one another.

“Tonino is unhappy,” said Old Niccolo.

Benvenuto seemed to feel this worthy of his attention. He withdrew his projecting leg, dropped to the library floor and arrived on top of the bookstand, all in one movement, without seeming to flex a muscle. There he stood, politely waving the one beautiful thing about him – his bushy black tail. The rest of his coat had worn to a ragged brown. Apart from the tail, the only thing which showed Benvenuto had once been a magnificent black Persian was the fluffy fur on his hind legs. And, as every other cat in Caprona knew to its cost, those fluffy breeches concealed muscles like a bulldog’s.

Paolo stared at his grandfather talking face to face with Benvenuto. He had always treated Benvenuto with respect himself, of course. It was well known that Benvenuto would not sit on your knee, and scratched you if you tried to pick him up. He knew all cats helped spells on wonderfully. But he had not realised before that cats understood so much. And he was sure Benvenuto was answering Old Niccolo, from the listening sort of pauses his grandfather made. Paolo looked at his father to see if this was true. Antonio was very ill at ease. And Paolo understood from his father’s worried face, that it was very important to be able to understand what cats said, and that Antonio never could. I shall have to start learning to understand Benvenuto, Paolo thought, very troubled.

“Which of you would you suggest?” asked Old Niccolo. Benvenuto raised his right front paw and gave it a casual lick. Old Niccolo’s face curved into his beaming baby’s smile. “Look at that!” he said. “He’ll do it himself!”

Benvenuto flicked the tip of his tail sideways. Then he was gone, leaping back to the window so fluidly and quickly that he might have been a paintbrush painting a dark line in the air. He left Aunt Francesca and Old Niccolo beaming, and Antonio still looking unhappy. “Tonino is taken care of,” Old Niccolo announced. “We shall not worry again unless he worries us.”

CHAPTER TWO (#u8bb0f7ee-043a-575e-b2b1-f412da8ddde9)

Tonino was already feeling soothed by the bustle in the golden streets of Caprona. In the narrower streets, he walked down the crack of sunlight in the middle, with washing flapping overhead, playing that it was sudden death to tread on the shadows. In fact, he died a number of times before he got as far as the Corso. A crowd of tourists pushed him off the sun once. So did two carts and a carriage. And once, a long, gleaming car came slowly growling along, hooting hard to clear the way.

When he was near the Corso, Tonino heard a tourist say in English, “Oh look! Punch and Judy!” Very smug at being able to understand, Tonino dived and pushed and tunnelled until he was at the front of the crowd and able to watch Punch beat Judy to death at the top of his little painted sentry-box. He clapped and cheered, and when someone puffed and panted into the crowd too, and pushed him aside, Tonino was as indignant as the rest. He had quite forgotten he was miserable. “Don’t shove!” he shouted.

“Have a heart!” protested the man. “I must see Mr Punch cheat the Hangman.”

“Then be quiet!” roared everyone, Tonino included.

“I only said—” began the man. He was a large damp-faced person, with an odd excitable manner.

“Shut up!” shouted everyone.

The man panted and grinned and watched with his mouth open Punch attack the policeman. He might have been the smallest boy there. Tonino looked irritably sideways at him and decided the man was probably an amiable lunatic. He let out such bellows of laughter at the smallest jokes, and he was so oddly dressed. He was wearing a shiny red silk suit with flashing gold buttons and glittering medals. Instead of the usual tie, he had white cloth folded at his neck, held in place by a brooch which winked like a tear-drop. There were glistening buckles on his shoes, and golden rosettes at his knees. What with his sweaty face and his white shiny teeth showing as he laughed, the man glistened all over.

Mr Punch noticed him too. “Oh what a clever fellow!” he crowed, bouncing about on his little wooden shelf. “I see gold buttons. Can it be the Pope?”

“Oh no it isn’t!” bellowed Mr Glister, highly delighted.

“Can it be the Duke?” cawed Mr Punch.

“Oh no it isn’t!” roared Mr Glister, and everyone else.

“Oh yes it is,” crowed Mr Punch.

While everyone was howling “Oh no it isn’t!” two worried-looking men pushed their way through the people to Mr Glister.

“Your Grace,” said one, “the Bishop reached the Cathedral half an hour ago.”

“Oh bother!” said Mr Glister. “Why are you lot always bullying me? Can’t I just – until this ends? I love Punch and Judy.”

The two men looked at him reproachfully.

“Oh – very well,” said Mr Glister. “You two pay the showman. Give everyone here something.” He turned and went bounding away into the Corso, puffing and panting.

For a moment, Tonino wondered if Mr Glister was actually the Duke of Caprona. But the two men made no attempt to pay the showman, or anyone else. They simply went trotting demurely after Mr Glister, as if they were afraid of losing him. From this, Tonino gathered that Mr Glister was indeed a lunatic – a rich one – and they were humouring him.

“Mean things!” crowed Mr Punch, and set about tricking the Hangman into being hanged instead of him. Tonino watched until Mr Punch bowed and retired in triumph into the little painted villa at the back of his stage. Then he turned away, remembering his unhappiness.

He did not feel like going back to the Casa Montana. He did not feel like doing anything particularly. He wandered on, the way he had been going, until he found himself in the Piazza Nuova, up on the hill at the western end of the city. Here he sat gloomily on the parapet, gazing across the River Voltava at the rich villas and the Ducal Palace, and at the long arches of the New Bridge, and wondering if he was going to spend the rest of his life in a fog of stupidity.

The Piazza Nuova had been made at the same time as the New Bridge, about seventy years ago, to give everyone the grand view of Caprona Tonino was looking at now. It was breathtaking. But the trouble was, everything Tonino looked at had something to do with the Casa Montana.

Take the Ducal Palace, whose golden-stone towers cut clear lines into the clean blue of the sky opposite. Each golden tower swept outwards at the top, so that the soldiers on the battlements, beneath the snapping red and gold flags, could not be reached by anyone climbing up from below. Tonino could see the shields built into the battlements, two a side, one cherry, one leaf-green, showing that the Montanas and the Petrocchis had added a spell to defend each tower. And the great white marble front below was inlaid with other marbles, all colours of the rainbow. And among those colours were cherry-red and leaf-green.

The long golden villas on the hillside below the Palace each had a leaf-green or cherry-red disc on their walls. Some were half hidden by the dark spires of the elegant little trees planted in front of them, but Tonino knew they were there. And the stone and metal arches of the New Bridge, sweeping away from him towards the villas and the Palace, each bore an enamel plaque, green and red alternately. The New Bridge had been sustained by the strongest spells the Casa Montana and the Casa Petrocchi could produce.

At the moment, when the river was just a shingly trickle, they did not seem necessary. But in winter, when the rain fell in the Apennines, the Voltava became a furious torrent. The arches of the New Bridge barely cleared it. The Old Bridge – which Tonino could see by craning out and sideways – was often under water, and the funny little houses along it could not be used. Only Montana and Petrocchi spells deep in its foundations stopped the Old Bridge being swept away.

Tonino had heard Old Niccolo say that the New Bridge spells had taken the entire efforts of the entire Montana family. Old Niccolo had helped make them when he was the same age as Tonino. Tonino could not have done. Miserable, he looked down at the golden walls and red pantiles of Caprona below. He was quite certain that every single one hid at least a leaf-green scrip. And the most Tonino had ever done was help stamp the winged horse on the outside. He was fairly sure that was all he ever would do.

He had a feeling somebody was calling him. Tonino looked round at the Piazza Nuova. Nobody. Despite the view, the Piazza was too far for the tourists to come. All Tonino could see were the mighty iron griffins which reared up at intervals all round the parapet, reaching iron paws to the sky. More griffins tangled into a fighting heap in the centre of the square to make a fountain. And even here, Tonino could not get away from his family. A little metal plate was set into the stone beneath the huge iron claws of the nearest griffin. It was leaf-green. Tonino found he had burst into tears.

Among his tears, he thought for a moment that one of the more distant griffins had left its stone perch and come trotting round the parapet towards him. It had left its wings behind, or else had them tightly folded. He was told, a little smugly, that cats do not need wings. Benvenuto sat down on the parapet beside him, staring accusingly.

Tonino had always been thoroughly in awe of Benvenuto. He stretched out a hand to him timidly. “Hallo, Benvenuto.”

Benvenuto ignored the hand. It was covered with water from Tonino’s eyes, he said, and it made a cat wonder why Tonino was being so silly.

“There are our spells everywhere,” Tonino explained. “And I’ll never be abley—Do you think it’s because I’m half English?”

Benvenuto was not sure quite what difference that made. All it meant, as far as he could see, was that Paolo had blue eyes like a Siamese and Rosa had white fur—

“Fair hair,” said Tonino.

—and Tonino himself had tabby hair, like the pale stripes in a tabby, Benvenuto continued, unperturbed. And those were all cats, weren’t they?

“But I’m so stupid—” Tonino began.

Benvenuto interrupted that he had heard Tonino chattering with those kittens yesterday, and he had thought Tonino was a good deal cleverer than they were. And before Tonino went and objected that those were only kittens, wasn’t Tonino only a kitten himself?

At this, Tonino laughed and dried his hand on his trousers. When he held the hand out to Benvenuto again, Benvenuto rose up, very high on all four paws, and advanced to it, purring. Tonino ventured to stroke him. Benvenuto walked round and round, arched and purring, like the smallest and friendliest kitten in the Casa. Tonino found himself grinning with pride and pleasure. He could tell from the waving of Benvenuto’s brush of a tail, in majestic, angry twitches, that Benvenuto did not altogether like being stroked – which made it all the more of an honour.

That was better, Benvenuto said. He minced up to Tonino’s bare legs and installed himself across them, like a brown muscular mat. Tonino went on stroking him. Prickles came out of one end of the mat and treadled painfully at Tonino’s thighs. Benvenuto continued to purr. Would Tonino look at it this way, he wondered, that they were both, boy and cat, a part of the most famous Casa in Caprona, which in turn was part of the most special of all the Italian States?

“I know that,” said Tonino. “It’s because I think it’s wonderful too that I—Are we really so special?”

Of course, purred Benvenuto. And if Tonino were to lean out and look across at the Cathedral, he would see why.

Obediently, Tonino leaned and looked. The huge marble bubbles of the Cathedral domes leapt up from among the houses at the end of the Corso. He knew there never was such a building as that. It floated, high and white and gold and green. And on the top of the highest dome the sun flashed on the great golden figure of the Angel, poised there with spread wings, holding in one hand a golden scroll. It seemed to bless all Caprona.

That Angel, Benvenuto informed him, was there as a sign that Caprona would be safe as long as everyone sang the tune of the Angel of Caprona. The Angel had brought that song in a scroll straight from Heaven to the First Duke of Caprona, and its power had banished the White Devil and made Caprona great. The White Devil had been prowling round Caprona ever since, trying to get back into the city, but as long as the Angel’s song was sung, it would never succeed.

“I know that,” said Tonino. “We sing the Angel every day at school.” That brought back the main part of his misery. “They keep making me learn the story – and all sorts of things – and I can’t, because I know them already, so I can’t learn properly.”

Benvenuto stopped purring. He quivered, because Tonino’s fingers had caught in one of the many lumps of matted fur in his coat. Still quivering, he demanded rather sourly why it hadn’t occurred to Tonino to tell them at school that he knew these things.

“Sorry!” Tonino hurriedly moved his fingers. “But,” he explained, “they keep saying you have to do them this way, or you’ll never learn properly.”

Well, it was up to Tonino of course, Benvenuto said, still irritable, but there seemed no point in learning things twice. A cat wouldn’t stand for it. And it was about time they were getting back to the Casa.

Tonino sighed. “I suppose so. They’ll be worried.”

He gathered Benvenuto into his arms and stood up.

Benvenuto liked that. He purred. And it had nothing to do with the Montanas being worried. The aunts would be cooking lunch, and Tonino would find it easier than Benvenuto to nick a nice piece of veal.

That made Tonino laugh. As he started down the steps to the New Bridge, he said, “You know, Benvenuto, you’d be a lot more comfortable if you let me get those lumps out of your coat and comb you a bit.”

Benvenuto stated that anyone trying to comb him would get raked with every claw he possessed.

“A brush then?”

Benvenuto said he would consider that.

It was here that Lucia encountered them. She had looked for Tonino all over Caprona by then and she was prepared to be extremely angry. But the sight of Benvenuto’s evil lop-sided countenance staring at her out of Tonino’s arms left her with almost nothing to say. “We’ll be late for lunch,” she said.

“No we won’t,” said Tonino. “We’ll be in time for you to stand guard while I steal Benvenuto some veal.”

“Trust Benvenuto to have it all worked out,” said Lucia. “What is this? The start of a profitable relationship?”

You could put it that way, Benvenuto told Tonino. “You could put it that way,” Tonino said to Lucia.

At all events, Lucia was sufficiently impressed to engage Aunt Gina in conversation while Tonino got Benvenuto his veal. And everyone was too pleased to see Tonino safely back to mind too much. Corinna and Rosa minded, however, that afternoon, when Corinna lost her scissors and Rosa her hairbrush. Both of them stormed out on to the gallery. Paolo was there, watching Tonino gently and carefully snip the mats out of Benvenuto’s coat. The hairbrush lay beside Tonino, full of brown fur.

“And you can really understand everything he says?” Paolo was saying.

“I can understand all the cats,” said Tonino. “Don’t move, Benvenuto. This one’s right on your skin.”

It says volumes for Benvenuto’s status – and therefore for Tonino’s – that neither Rosa nor Corinna dared say a word to him. They turned on Paolo instead. “What do you mean, Paolo, standing there letting him mess that brush up? Why couldn’t you make him use the kitchen scissors?”

Paolo did not mind. He was too relieved that he was not going to have to learn to understand cats himself. He would not have known how to begin.

From that time forward, Benvenuto regarded himself as Tonino’s special cat. It made a difference to both of them. Benvenuto, what with constant brushing – for Rosa bought Tonino a special hairbrush for him – and almost as constant supplies filched from under Aunt Gina’s nose, soon began to look younger and sleeker. Tonino forgot he had ever been unhappy. He was now a proud and special person. When Old Niccolo needed Benvenuto, he had to ask Tonino first. Benvenuto flatly refused to do anything for anyone without Tonino’s permission. Paolo was very amused at how angry Old Niccolo got.

“That cat has just taken advantage of me!” he stormed. “I ask him to do me a kindness and what do I get? Ingratitude!”

In the end, Tonino had to tell Benvenuto that he was to consider himself at Old Niccolo’s service while Tonino was at school. Otherwise Benvenuto simply disappeared for the day. But he always, unfailingly, reappeared around half-past three, and sat on the water butt nearest the gate, waiting for Tonino. And as soon as Tonino came through the gate, Benvenuto would jump into his arms.

This was true even at the times when Benvenuto was not available to anyone. That was mostly at full moon, when the lady cats wauled enticingly from the roofs of Caprona.

Tonino went to school on Monday, having considered Benvenuto’s advice. And, when the time came when they gave him a picture of a cat and said the shapes under it went: Ker-a-ter, Tonino gathered up his courage and whispered, “Yes. It’s a C and an A and a T. I know how to read.”

His teacher, who was new to Caprona, did not know what to make of him, and called the Headmistress. “Oh,” she was told. “It’s another Montana. I should have warned you. They all know how to read. Most of them know Latin too – they use it a lot in their spells – and some of them know English as well. You’ll find they’re about average with sums, though.”

So Tonino was given a proper book while the other children learnt their letters. It was too easy for him. He finished it in ten minutes and had to be given another. And that was how he discovered about books. To Tonino, reading a book soon became an enchantment above any spell. He could never get enough of it. He ransacked the Casa Montana and the Public Library, and he spent all his pocket money on books. It soon became well known that the best present you could give Tonino was a book – and the best book would be about the unimaginable situation where there were no spells. For Tonino preferred fantasy. In his favourite books, people had wild adventures with no magic to help or hinder them.

Benvenuto thoroughly approved. While Tonino read, he kept still, and a cat could be comfortable sitting on him. Paolo teased Tonino a little about being such a bookworm, but he did not really mind. He knew he could always persuade Tonino to leave his book if he really wanted him.

Antonio was worried. He worried about everything. He was afraid Tonino was not getting enough exercise. But everyone else in the Casa said this was nonsense. They were proud of Tonino. He was as studious as Corinna, they said, and, no doubt, both of them would end up at Caprona University, like Great-Uncle Umberto. The Montanas always had someone at the University. It meant they were not selfishly keeping the Theory of Magic to the family, and it was also very useful to have access to the spells in the University Library.

Despite these hopes for him, Tonino continued to be slow at learning spells and not particularly quick at school. Paolo was twice as quick at both. But as the years went by, both of them accepted it. It did not worry them. What worried them far more was their gradual discovery that things were not altogether well in the Casa Montana, nor in Caprona either.

CHAPTER THREE (#u8bb0f7ee-043a-575e-b2b1-f412da8ddde9)

It was Benvenuto who first worried Tonino. Despite all the care Tonino gave him, he became steadily thinner and more ragged again. Now Benvenuto was roughly the same age as Tonino. Tonino knew that was old for a cat, and at first he assumed that Benvenuto was just feeling his years. Then he noticed that Old Niccolo had taken to looking almost as worried as Antonio, and that Uncle Umberto called on him from the University almost every day. Each time he did, Old Niccolo or Aunt Francesca would ask for Benvenuto and Benvenuto would come back tired out. So he asked Benvenuto what was wrong.

Benvenuto’s reply was that they might let a cat have some peace, even if the Duke was a booby. And he was not going to be pestered by Tonino into the bargain.

Tonino consulted Paolo, and found Paolo worried too. Paolo had been noticing his mother. Her fair hair had lately become several shades paler with all the white in it, and she looked nervous all the time. When Paolo asked Elizabeth what was the matter, she said, “Oh nothing, Paolo – only all this makes it so difficult to find a husband for Rosa.”

Rosa was now eighteen. The entire Casa was busy discussing a husband for her, and there did, now Paolo noticed, seem much more fuss and anxiety about the matter than there had been over Cousin Claudia, three years before. Montanas had to be careful who they married. It stood to reason. They had to marry someone who had some talent at least for spells or music; and it had to be someone the rest of the family liked; and, above all, it had to be someone with no kind of connection with the Petrocchis. But Cousin Claudia had found and married Arturo without all the discussion and worry that was going on over Rosa. Paolo could only suppose the reason was “all this”, whatever Elizabeth had meant by that.

Whatever the reason, argument raged. Anxious Antonio talked of going to England and consulting someone called Chrestomanci about it. “We want a really strong spell-maker for her,” he said. To which Elizabeth replied that Rosa was Italian and should marry an Italian. The rest of the family agreed, except that they said the Italian must be from Caprona. So the question was who.

Paolo, Lucia and Tonino had no doubt. They wanted Rosa to marry their cousin Rinaldo. It seemed to them entirely fitting. Rosa was lovely, Rinaldo handsome, and none of the usual objections could possibly be made. There were two snags, however. The first was that Rinaldo showed no interest in Rosa. He was at present desperately in love with a real English girl – her name was Jane Smith, and Rinaldo had some difficulty pronouncing it – and she had come to copy some of the pictures in the Art Gallery down on the Corso. She was a romantic girl. To please her, Rinaldo had taken to wearing black, with a red scarf at his neck, like a bandit. He was said to be considering growing a bandit moustache too. All of which left him with no time for a cousin he had known all his life.

The other snag was Rosa herself. She had never cared for Rinaldo. And she seemed to be the only person in the Casa who was entirely unconcerned about who she would marry. When the argument raged loudest, she would shake the blonde hair on her shoulders and smile. “To listen to you all,” she said, “anyone would think I have no say in the matter at all. It’s really funny.”

All that autumn, the worry in the Casa Montana grew. Paolo and Tonino asked Aunt Maria what it was all about. Aunt Maria at first said that they were too young to understand. Then, since she had moments when she was as passionate as Aunt Gina or even Aunt Francesca, she told them suddenly and fervently that Caprona was going to the dogs.

“Everything’s going wrong for us,” she said. “Money’s short, tourists don’t come here, and we get weaker every year. Here are Florence, Pisa and Siena all gathering round like vultures, and each year one of them gets a few more square miles of Caprona. If this goes on we shan’t be a State any more. And on top of it all, the harvest failed this year. It’s all the fault of those degenerate Petrocchis, I tell you! Their spells don’t work any more. We Montanas can’t hold Caprona up on our own! And the Petrocchis don’t even try! They just keep turning things out in the same old way, and going from bad to worse. You can see they are, or that child wouldn’t have been able to turn her father green!”

This was disturbing enough. And it seemed to be plain fact. All the years Paolo and Tonino had been at school, they had grown used to hearing that there had been this concession to Florence; that Pisa had demanded that agreement over fishing rights; or that Siena had raised taxes on imports to Caprona. They had grown too used to it to notice. But now it all seemed ominous. And worse shortly followed. News came that the Old Bridge had been seriously cracked by the winter floods.

This news caused the Casa Montana real dismay. For that bridge should have held. If it gave, it meant that the Montana charms in the foundations had given too. Aunt Francesca ran shrieking into the yard. “Those degenerate Petrocchis! They can’t even sustain an old spell now! We’ve been betrayed!”

Though no one else put it quite that way, Aunt Francesca probably spoke for the whole family.

As if that was not enough, Rinaldo set off that evening to visit his English girl, and was led back to the Casa streaming with blood, supported by his cousins Carlo and Giovanni. Rinaldo, using curse words Paolo and Tonino had never heard before, was understood to say he had met some Petrocchis. He had called them degenerate. And it was Aunt Maria’s turn to rush shrieking through the yard, shouting dire things about the Petrocchis. Rinaldo was the apple of Aunt Maria’s eye.

Rinaldo had been bandaged and put to bed, when Antonio and Uncle Lorenzo came back from viewing the damage to the Old Bridge. Both looked very serious. Old Guido Petrocchi himself had been there, with the Duke’s contractor, Mr Andretti. Some very deep charms had given. It was going to take the whole of both families, working in shifts, at least three weeks to mend them.

“We could have used Rinaldo’s help,” Antonio said.

Rinaldo swore that he was well enough to get out of bed and help the next day, but Aunt Maria would not hear of it. Nor would the doctor. So the rest of the family was divided into shifts, and work went on day and night. Paolo, Lucia and Corinna went to the bridge straight from school every day. Tonino did not. He was still too slow to be much use. But from what Paolo told him, he did not think he was missing much. Paolo simply could not keep up with the furious pace of the spells. He was put to running errands, like poor Cousin Domenico. Tonino felt very sympathetic towards Domenico. He was the opposite of his dashing brother Rinaldo in every way, and he could not keep up with the pace of things either.

Work had been going on, often in pouring rain, for nearly a week, when the Duke of Caprona summoned Old Niccolo to speak to him.

Old Niccolo stood in the yard and tore what was left of his hair. Tonino laid down his book (it was called Machines of Death and quite fascinating) and went to see if he could help.

“Ah, Tonino,” said Old Niccolo, looking at him with the face of a grieving baby. “I have gigantic problems. Everyone is needed on the Old Bridge, and that ass Rinaldo is lying in bed, and I have to go before the Duke with some of my family. The Petrocchis have been summoned too. We cannot appear less than they are, after all. Oh why did Rinaldo choose such a time to shout stupid insults?”

Tonino had no idea what to say, so he said, “Shall I get Benvenuto?”

“No, no,” said Old Niccolo, more upset than ever. “The Duchess cannot abide cats. Benvenuto is no use here. I shall have to take those who are no use on the bridge. You shall go, Tonino, and Paolo and Domenico, and I shall take your uncle Umberto to look wise and weighty. Perhaps that way we shan’t look so very thin.”

This was perhaps not the most flattering of invitations, but Tonino and Paolo were delighted nevertheless. They were delighted even though it rained hard the next day, the drilling white rain of winter. The dawn shift came in from the Old Bridge under shiny umbrellas, damp and disgruntled. Instead of resting, they had to turn to and get the party ready for the Palace.

The Montana family coach was dragged from the coach-house to a spot under the gallery, where it was carefully dusted. It was a great black thing with glass windows and monster black wheels. The Montana winged horse was emblazoned in a green shield on its heavy doors. The rain continued to pour down. Paolo, who hated rain as much as the cats did, was glad the coach was real. The horses were not. They were four white cardboard cut-outs of horses, which were kept leaning against the wall of the coach-house. They were an economical idea of Old Niccolo’s father’s. As he said, real horses ate and needed exercise and took up space the family could live in. The coachman was another cardboard cut-out – for much the same reasons – but he was kept inside the coach.

The boys were longing to watch the cardboard figures being brought to life, but they were snatched indoors by their mother. Elizabeth’s hair was soaking from her shift on the bridge and she was yawning until her jaw creaked, but this did not prevent her doing a very thorough scrubbing, combing and dressing job on Paolo and Tonino. By the time they came down into the yard again, each with his hair scraped wet to his head and wearing uncomfortable broad white collars above their stiff Eton jackets, the spell was done. The spell-streamers had been carefully wound into the harness, and the coachman clothed in a paper coat covered with spells on the inside. Four glossy white horses were stamping as they were backed into their traces. The coachman was sitting on the box adjusting his leaf-green hat.

“Splendid!” said Old Niccolo, bustling out. He looked approvingly from the boys to the coach. “Get in, boys. Get in, Domenico. We have to pick up Umberto from the University.”

Tonino said goodbye to Benvenuto and climbed into the coach. It smelt of mould, in spite of the dusting. He was glad his grandfather was so cheerful. In fact everyone seemed to be. The family cheered as the coach rumbled to the gateway, and Old Niccolo smiled and waved back. Perhaps, Tonino thought, something good was going to come from this visit to the Duke, and no one would be so worried after this.

The journey in the coach was splendid. Tonino had never felt so grand before. The coach rumbled and swayed. The hooves of the horses clattered over the cobbles just as if they were real, and people hurried respectfully out of their way. The coachman was as good as spells could make him. Though puddles dimpled along every street, the coach was hardly splashed when they drew up at the University, with loud shouts of “Whoa there!”

Uncle Umberto climbed in, wearing his red and gold Master’s gown, as cheerful as Old Niccolo. “Morning, Tonino,” he said to Paolo. “How’s your cat? Morning,” he said to Domenico. “I hear the Petrocchis beat you up.” Domenico, who would have died sooner than insult even a Petrocchi, went redder than Uncle Umberto’s gown and swallowed noisily. But Uncle Umberto never could remember which younger Montana was which. He was too learned. He looked at Tonino as if he was wondering who he was, and turned to Old Niccolo.

“The Petrocchis are sure to help,” he said. “I had word from Chrestomanci.”

“So did I,” said Old Niccolo, but he sounded dubious.

The coach rumbled down the rainswept Corso and turned out across the New Bridge, where it rumbled even more loudly. Paolo and Tonino stared out of the rainy windows, too excited to speak. Beyond the swollen river, they clopped uphill, where cypresses bent and lashed in front of rich villas, and then among blurred old walls. Finally they rumbled under a great archway and made a crisp turn round the gigantic forecourt of the Palace.

In front of their own coach, another coach, looking like a toy under the huge marble front of the Palace, was just drawing up by the enormous marble porch. This carriage was black too, with crimson shields on its doors, in which ramped black leopards. They were too late to see the people getting out of it, but they gazed with irritated envy at the coach itself and the horses. The horses were black, beautiful slender creatures with arched necks.

“I think they’re real horses,” Paolo whispered to Tonino.

Tonino had no time to answer, because two footmen and a soldier sprang to open the carriage door and usher them down, and Paolo jumped down first. But after him, Old Niccolo and Uncle Umberto were rather slow getting down. Tonino had time to look out of the further window at the Petrocchi carriage moving away. As it turned, he distinctly saw the small crimson flutter of a spell-streamer under the harness of the nearest black horse.

So there! Tonino thought triumphantly. But he rather thought the Petrocchi coachman was real. He was a pale young man with reddish hair which did not match his cherry-coloured livery, and he had an intent, concentrating look as if it was not easy driving those unreal horses. That look was too human for a cardboard man.

When Tonino finally climbed down on Domenico’s nervous heels, he glanced up at their own coachman for comparison. He was efficient and jaunty. He touched a stiff hand to his green hat and stared straight ahead. No, the Petrocchi coachman was real all right, Tonino thought enviously.

Tonino forgot both coachmen as he and Paolo followed the others into the Palace. It was so grand, and so huge. They were taken through vast halls with shiny floors and gilded ceilings, which seemed to go on for miles. On either side of the long walls there were statues, or soldiers, or footmen, adding to the magnificence in rows. They felt so battered by all the grandeur that it was quite a relief when they were shown into a room only about the size of the Casa Montana yard. True, the floor was shiny and the ceiling painted to look like a sky full of wrestling angels, but the walls were hung with quite comfortable red cloth and there was a row of almost plain gilt chairs along each side.

Another party of people was shown into the room at the same time. Domenico took one look at them and turned his eyes instantly on the painted angels of the ceiling. Old Niccolo and Uncle Umberto behaved as if the people were not there at all. Paolo and Tonino tried to do the same, but they found it impossible.

So these were the Petrocchis, they thought, sneaking glances. There were only four of them, to their five. One up to the Montanas. And two of those were children. Clearly the Petrocchis had been as hard-pressed as the Montanas to come before the Duke with a decent party, and they had, in Paolo and Tonino’s opinion, made a bad mistake in leaving one of their family outside with the coach.

They were not impressive. Their University representative was a frail old man, far older than Uncle Umberto, who seemed almost lost in his red and gold gown. The most impressive one was the leader of the party, who must be Old Guido himself. But he was not particularly old, like Old Niccolo, and though he wore the same sort of black frock-coat as Old Niccolo and carried the same sort of shiny hat, it looked odd on Old Guido because he had a bright red beard. His hair was rather long, crinkly and black. And though he stared ahead in a bleak, important way, it was hard to forget that his daughter had once accidentally turned him green.

The two children were both girls. Both had reddish hair. Both had prim, pointed faces. Both wore bright white stockings and severe black dresses and were clearly odious. The main difference between them was that the younger – who seemed about Tonino’s age – had a large bulging forehead, which made her face even primmer than her sister’s. It was possible that one of them was the famous Angelica, who had turned Old Guido green.

The boys stared at them, trying to decide which it might be, until they encountered the prim, derisive stare of the elder girl. It was clear she thought they looked ridiculous. But Paolo and Tonino knew they still looked smart – they felt so uncomfortable – so they took no notice.

After they had waited a while, both parties began to talk quietly among themselves, as if the others were not there. Tonino murmured to Paolo, “Which one is Angelica?”

“I don’t know,” Paolo whispered.

“Didn’t you see them at the Old Bridge then?”

“I didn’t see any of them. They were all down the other—”

Part of the red hanging swung aside and a lady hurried in. “I’m so sorry,” she said. “My husband has been delayed.”

Everyone in the room bent their heads and murmured “Your Grace” because this was the Duchess. But Paolo and Tonino kept their eyes on her while they bent their heads, wanting to know what she was like. She had a stiff greyish dress on, which put them in mind of a statue of a saint, and her face might almost have been part of the same statue. It was a statue-pale face, almost waxy, as if the Duchess were carved out of slightly soapy marble. But Tonino was not sure the Duchess was really like a saint. Her eyebrows were set in a strong sarcastic arch, and her mouth was tight with what looked like impatience. For a second, Tonino thought he felt that impatience – and a number of other unsaintly feelings – pouring into the room from behind the Duchess’s waxy mask like a strong rank smell.

The Duchess smiled at Old Niccolo. “Signor Niccolo Montana?” There was no scrap of impatience, only stateliness. Tonino thought to himself, I’ve been reading too many books. Rather ashamed, he watched Old Niccolo bow and introduce them all. The Duchess nodded graciously and turned to the Petrocchis. “Signor Guido Petrocchi?”

The red-bearded man bowed in a rough, brusque way. He was nothing like as courtly as Old Niccolo. “Your Grace. With me are my great-uncle Dr Luigi Petrocchi, my elder daughter Renata, and my younger daughter Angelica.”

Paolo and Tonino stared at the younger girl, from her bulge of forehead to her thin white legs. So this was Angelica. She did not look capable of doing anything wrong, or interesting.

The Duchess said, “I believe you understand why—”

The red curtains were once more swept aside. A bulky excited-looking man raced in with his head down, and took the Duchess by one arm. “Lucrezia, you must come! The scenery looks a treat!”

The Duchess turned as a statue might turn, all one piece. Her eyebrows were very high and her mouth pinched. “My lord Duke!” she said freezingly.

Tonino stared at the bulky man. He was now wearing slightly shabby green velvet with big brass buttons. Otherwise, he was exactly the same as the big damp Mr Glister who had interrupted the Punch and Judy show that time. So he had been the Duke of Caprona after all! And he was not in the least put off by the Duchess’s frigid look. “You must come and look!” he said, tugging at her arm, as excited as ever. He turned to the Montanas and the Petrocchis as if he expected them to help him pull the Duchess out of the room – and then seemed to realise that they were not courtiers. “Who are you?”

“These,” said the Duchess – her eyebrows were still higher and her voice was strong with patience – “these are the Petrocchis and the Montanas awaiting your pleasure, my lord.”

The Duke slapped a large, damp-looking hand to his shiny forehead. “Well I’m blessed! The people who make spells! I was thinking of sending for you. Have you come about this enchanter-fellow who’s got his knife into Caprona?” he asked Old Niccolo.

“My lord!” said the Duchess, her face rigid.

But the Duke broke away from her, beaming and gleaming, and dived on the Petrocchis. He shook Old Guido’s hand hugely, and then the girl Renata’s. After that, he dived round and did the same to Old Niccolo and Paolo. Paolo had to rub his hand secretly on his trousers after he let go. He was wet. “And they say the young ones are as clever as the old ones,” the Duke said happily. “Amazing families! Just the people I need for my play – my pantomime, you know. We’re putting it on here for Christmas and I could do with some special effects.”

The Duchess gave a sigh. Paolo looked at her rigid face and thought that it must be hard, dealing with someone like the Duke.

The Duke dived on Domenico. “Can you arrange for a flight of cupids blowing trumpets?” he asked him eagerly. Domenico swallowed and managed to whisper the word “illusion”. “Oh good!” said the Duke, and dived at Angelica Petrocchi. “And you’ll love my collection of Punch and Judys,” he said. “I’ve got hundreds!”

“How nice,” Angelica answered primly.

“My lord,” said the Duchess, “these good people did not come here to discuss the theatre.”

“Maybe, maybe,” the Duke said, with an impatient, eager wave of his large hand. “But while they’re here, I might as well ask them about that too. Mightn’t I?” he said, diving at Old Niccolo.

Old Niccolo showed great presence of mind. He smiled. “Of course, Your Grace. No trouble at all. After we’ve discussed the State business we came for, we shall be happy to take orders for any stage effects you want.”

“So will we,” said Guido Petrocchi, with a sour glance at the air over Old Niccolo.

The Duchess smiled graciously at Old Niccolo for backing her up, which made Old Guido look sourer than ever, and fixed the Duke with a meaning look.

It seemed to get through to the Duke at last. “Yes, yes,” he said. “Better get down to business. It’s like this, you see—”

The Duchess interrupted, with a gentle fixed smile. “Refreshments are laid out in the small Conference Room. If you and the adults like to hold your discussion there, I will arrange something for the children here.”

Guido Petrocchi saw a chance to get even with Old Niccolo. “Your Grace,” he barked stiffly, “my daughters are as loyal to Caprona as the rest of my house. I have no secrets from them.”

The Duke flashed him a glistening smile. “Quite right! But they won’t be half as bored if they stay here, will they?”

Quite suddenly, everyone except Paolo and Tonino and the two Petrocchi girls was crowding away through another door behind the red hangings. The Duke leaned back, beaming. “I tell you what,” he said, “you must come to my pantomime, all of you. You’ll love it! I’ll send you tickets. Coming, Lucrezia.”

The four children were left standing under the ceiling full of wrestling angels.

After a moment, the Petrocchi girls walked to the chairs against the wall and sat down. Paolo and Tonino looked at one another. They marched to the chairs on the opposite side of the room and sat down there. It seemed a safe distance. From there, the Petrocchi girls were dark blurs with thin white legs and foxy blobs for heads.

“I wish I’d brought my book,” said Tonino.

They sat with their heels hooked into the rungs of their chairs, trying to feel patient. “I think the Duchess must be a saint,” said Paolo, “to be so patient with the Duke.”

Tonino was surprised Paolo should think that. He knew the Duke did not behave much like a duke should, while the Duchess was every inch a duchess. But he was not sure it was right, the way she let them know how patient she was being. “Mother dashes about like that,” he said, “and Father doesn’t mind. It stops him looking worried.”

“Father’s not a Duchess,” said Paolo.

Tonino did not argue because, at that moment, two footmen appeared, pushing a most interesting trolley. Tonino’s mouth fell open. He had never seen so many cakes together in his life before. Across the room, there were black gaps in the faces of the Petrocchi girls. Evidently they had never seen so many cakes either. Tonino shut his mouth quickly and tried to look as if he saw such sights every day.

The footmen served the Petrocchi girls first. They were very cool and seemed to take hours choosing. When the trolley was finally wheeled across to Paolo and Tonino, they found it hard to seem as composed. There were twenty different kinds of cake. They took ten each, with greedy speed, so that they had one of every kind between them and could swap if necessary. When the trolley was wheeled away, Tonino just managed to spare a glance from his plate to see how the Petrocchis were doing. Each girl had her white knees hooked up to carry a plate big enough to hold ten cakes.

They were rich cakes. By the time Paolo reached the tenth, he was going slowly, wondering if he really cared for meringue as much as he had thought, and Tonino was only on his sixth. By the time Paolo had put his plate neatly under his chair and cleaned himself with his handkerchief, Tonino, sticky with jam, smeared with chocolate and cream and infested with crumbs, was still doggedly ploughing through his eighth. And this was the moment the Duchess chose to sit smiling down beside Paolo.

“I won’t interrupt your brother,” she said, laughing. “Tell me about yourself, Paolo.” Paolo did not know what to answer. All he could think of was the mess Tonino looked. “For instance,” the Duchess asked helpfully, “does spell-making come easily to you? Do you find it hard to learn?”

“Oh no, Your Grace,” Paolo said proudly. “I learn very easily.” Then he was afraid this might upset Tonino. He looked quickly at Tonino’s pastry-plastered face and found Tonino staring gravely at the Duchess. Paolo felt ashamed and responsible. He wanted the Duchess to know that Tonino was not just a messy staring little boy. “Tonino learns slowly,” he said, “but he reads all the time. He’s read all the books in the Library. He’s almost as learned as Uncle Umberto.”

“How remarkable,” smiled the Duchess.

There was just a trace of disbelief in the arch of her eyebrows. Tonino was so embarrassed that he took a big bite out of his ninth cake. It was a great pastry puff. The instant his mouth closed round it, Tonino knew that, if he opened his mouth again, even to breathe, pastry would blow out of it like a hailstorm, all over Paolo and the Duchess. He clamped his lips together and chewed valiantly.

And, to Paolo’s embarrassment, he went on staring at the Duchess. He was wishing Benvenuto was there to tell him about the Duchess. She muddled him. As she bent smiling over Paolo, she did not look like the haughty, rigid lady who had been so patient with the Duke. And yet, perhaps because she was not being patient, Tonino felt the rank strength of the unsaintly thoughts behind her waxy smile, stronger than ever.

Paolo willed Tonino to stop chewing and goggling. But Tonino went on, and the disbelief in the Duchess’s eyebrows was so obvious, that he blurted out, “And Tonino’s the only one who can talk to Benvenuto. He’s our boss cat, Your—” He remembered the Duchess did not like cats. “Er – you don’t like cats, Your Grace.”

The Duchess laughed. “But I don’t mind hearing about them. What about Benvenuto?”

To Paolo’s relief, Tonino turned his goggle eyes from the Duchess to him. So Paolo talked on. “You see, Your Grace, spells work much better and stronger if a cat’s around, and particularly if Benvenuto is. Besides Benvenuto knows all sorts of things—”

He was interrupted by a thick noise from Tonino. Tonino was trying to speak without opening his mouth. It was clear there was going to be a pastry-storm any second. Paolo snatched out his jammy, creamy handkerchief and held it ready.

The Duchess stood up, rather hastily. “I think I’d better see how my other guests are getting on,” she said, and went swiftly gliding across to the Petrocchi girls.

The Petrocchi girls, Paolo noticed resentfully, were ready to receive her. Their handkerchiefs had been busy while the Duchess talked to Paolo, and now their plates were neatly pushed under their chairs too. Each had left at least three cakes. This much encouraged Tonino. He was feeling rather unwell. He put the rest of the ninth cake back beside the tenth and laid the plate carefully on the next chair. By this time, he had managed to swallow his mouthful.

“You shouldn’t have told her about Benvenuto,” he said, hauling out his handkerchief. “He’s a family secret.”

“Then you should have said something yourself instead of staring like a dummy,” Paolo retorted. To his mortification both Petrocchi girls were talking merrily to the Duchess. The bulge-headed Angelica was laughing. It so annoyed Paolo that he said, “Look at the way those girls are sucking up to the Duchess!”

“I didn’t do that,” Tonino pointed out.

As Paolo wanted to say he wished Tonino had, he found himself unable to say anything at all. He sat sourly watching the Duchess talking to the girls across the room, until she got up and went gliding away. She remembered to smile and wave at Paolo and Tonino as she went. Paolo thought that was good of her, considering the asses they had made of themselves.

Very soon after that, the curtains swung aside and Old Niccolo came back, walking slowly beside Guido Petrocchi. After them came the two gowned great-uncles, and Domenico came after that. It was like a procession. Everyone looked straight ahead, and it was plain they had a lot on their minds. All four children stood up, brushed crumbs off, and followed the procession. Paolo found he was walking beside the elder girl, but he was careful not to look at her. In utter silence, they marched to the great Palace door, where the carriages were moving along to receive them.

The Petrocchi carriage came first, with its black horses patched and beaded with rain. Tonino took another look at its coachman, rather hoping he had made a mistake. It was still raining and the man’s clothes were soaked. His red Petrocchi hair was brown with wet under his wet hat. He was shivering as he leant down, and there was a questioning look on his pale face, as if he was anxious to be told what the Duke had said. No, he was real all right. The Montana coachman behind stared into space, ignoring the rain and his passengers equally. Tonino felt that the Petrocchis had definitely come out best.

CHAPTER FOUR (#u8bb0f7ee-043a-575e-b2b1-f412da8ddde9)

When the coach was moving, Old Niccolo leaned back and said, “Well, the Duke is very good-natured, I’ll say that. Perhaps he’s not such a fool as he seems.”

Uncle Umberto answered, with deepest gloom, “When my father was a boy, his father went to the Palace once a week. He was received as a friend.”

Domenico said timidly, “At least we sold some stage effects.”

“That,” said Uncle Umberto crushingly, “is just what I’m complaining of.”

Tonino and Paolo looked from one to the other, wondering what had depressed them so.

Old Niccolo noticed them looking. “Guido Petrocchi wished those disgusting daughters of his to be present while we conferred with the Duke,” he said. “I shall not—”

“Oh good Lord!” muttered Uncle Umberto. “One doesn’t listen to a Petrocchi.”

“No, but one trusts one’s grandsons,” said Old Niccolo. “Boys, old Caprona’s in a bad way, it seems. The States of Florence, Pisa and Siena have now united against her. The Duke suspects they are paying an enchanter to—”

“Huh!” said Uncle Umberto. “Paying the Petrocchis.”

Domenico, who had been rendered surprisingly bold by something, said, “Uncle, I could see the Petrocchis were no more traitors than we are!”

Both old men turned to look at him. He crumpled.

“The fact is,” Old Niccolo continued, “Caprona is not the great State she once was. There are many reasons, no doubt. But we know, and the Duke knows – even Domenico knows – that each year we set the usual charms for the defence of Caprona, and each year we set them stronger, and each year they have less effect. Something – or someone – is definitely sapping our strength. So the Duke asks what else we can do. And—”

Domenico interrupted with a squawk of laughter. “And we said we’d find the words to the Angel of Caprona!”

Paolo and Tonino expected Domenico to be crushed again, but the two old men simply looked gloomy. Their heads nodded mournfully. “But I don’t understand,” said Tonino. “The Angel of Caprona’s got words. We sing them at school.”

“Hasn’t your mother taught you—?” Old Niccolo began angrily. “Ah, no. I forgot. Your mother is English.”

“One more reason for careful marriages,” Uncle Umberto said dismally.

By this time, what with the rain ceaselessly pattering down as well, both boys were thoroughly depressed and alarmed. Domenico seemed to find them funny. He gave another squawk of laughter.

“Be quiet,” said Old Niccolo. “This is the last time I take you where brandy is served. No, boys, the Angel has not got the right words. The words you sing are a makeshift. Some people say that the glorious Angel took the words back to Heaven after the White Devil was vanquished, leaving only the tune. Or the words have been lost since. But everyone knows that Caprona cannot be truly great until the words are found.”

“In other words,” Uncle Umberto said irritably, “the Angel of Caprona is a spell like any other spell. And without the proper words, any spell is only at half force, even if it is of divine origin.” He gathered up his gown as the coach jerked to a stop outside the University. “And we – like idiots – have pledged ourselves to complete what God left unfinished,” he said. “The presumption of man!” He climbed out of the coach, calling to Old Niccolo, “I’ll look in every manuscript I can think of. There must be a clue somewhere. Oh this confounded rain!”

The door slammed and the coach jerked on again.

Paolo asked, “Have the Petrocchis said they’ll find the words too?”

Old Niccolo’s mouth bunched angrily. “They have. And I should die of shame if they did it before we did. I—” He stopped as the coach lurched round the corner into the Corso. It lurched again, and jerked. Sprays of water flew past the windows.

Domenico leaned forward. “Not driving so well, is he?”

“Quiet!” said Old Niccolo, and Paolo bit his tongue in a whole succession of jerks. Something was wrong. The coach was not making the right noise.

“I can’t hear the horses’ hooves,” Tonino said, puzzled.

“I thought that was it!” Old Niccolo snapped. “It’s the rain.” He let down the window with a bang, bringing in a gust of watery wind, and, regardless of faces staring up at him from under wet umbrellas, he leaned out and bellowed the words of a spell. “And drive quickly, coachman! There,” he said, as he pulled the window up again, “that should get us home before the horses turn to pulp. What a blessing this didn’t happen before Umberto got out!”

The noise of the horses’ hooves sounded again, clopping over the cobbles of the Corso. It seemed that the new spell was working. But, as they turned into the Via Cardinale, the noise changed to a spongy thump-thump, and when they came to the Via Magica the hooves made hardly a sound. And the lurching and jerking began again, worse than ever. As they turned to enter the gate of the Casa Montana, there came the most brutal jerk of all. The coach tipped forward, and there was a crash as the pole hit the cobbles. Paolo got his window open in time to see the limp paper figure of the coachman flop off the box into a puddle. Beyond him, two wet cardboard horses were draped over their traces.

“That spell,” said Old Niccolo, “lasted for days in my grandfather’s time.”

“Do you mean it’s that enchanter?” Paolo asked. “Is he spoiling all our spells?”

Old Niccolo stared at him, full-eyed, like a baby about to burst into tears. “No, lad. I fancy not. The truth is, the Casa Montana is in as bad a way as Caprona. The old virtue is fading. It has faded generation by generation, and now it is almost gone. I am ashamed that you should learn it like this. Let’s get out, boys, and start dragging.”

It was a wretched humiliation. Since the rest of the family were all either asleep or at work on the Old Bridge, there was no one to help them pull the coach through the gate. And Domenico was no use. He confessed afterwards that he could not remember getting home. They left him asleep in the coach and dragged it in, just the three of them. Even Benvenuto dashing through the rain did not cheer Tonino much.

“One consolation,” panted their grandfather. “The rain. There is no one about to see Old Niccolo dragging his own coach.”

Paolo and Tonino did not find much consolation in that. Now they understood the growing unease in the Casa, and it was not pleasant. They understood why everyone was so anxious about the Old Bridge, and so delighted when, just before Christmas, it was mended at last. They understood, too, the worry about a husband for Rosa. As soon as the bridge was repaired, everyone went back to discussing that. And Paolo and Tonino knew why everyone agreed that the young man Rosa must choose, must have, if he had nothing else, a strong talent for spells.

“To improve the breed, you mean?” said Rosa. She was very sarcastic and independent about it. “Very well, dear Uncle Lorenzo, I shall only fall in love with men who can make paper horses waterproof.”

Uncle Lorenzo blushed angrily. The whole family felt humiliated by those horses. But Elizabeth was trying not to laugh. Elizabeth certainly encouraged Rosa in her independent attitude. Benvenuto informed Tonino it was the English way. Cats liked English people, he added.

“Have we really lost our virtue?” Tonino asked Benvenuto anxiously. He thought it was probably the explanation for his slowness.

Benvenuto said that he did not know what it was like in the old days, but he knew there was enough magic about now to make his coat spark. It seemed like a lot. But he sometimes wondered if it was being applied properly.

Around this time, twice as many newspapers found their way into the Casa. There were journals from Rome and magazines from Genoa and Milan, as well as the usual Caprona papers. Everyone read them eagerly and talked in mutters about the attitude of Florence, movements in Pisa and opinion hardening in Siena. Out of the worried murmurs, the word War began to sound, more and more frequently. And, instead of the usual Christmas songs, the only tune heard in the Casa Montana, night and day, was the Angel of Caprona.

The tune was sung in bass, tenor and soprano. It was played slowly on flutes, picked out on guitars and lilted on violins. Every one of the Montanas lived in hope that he or she would be the person to find the true words. Rinaldo had a new idea. He procured a drum and sat on the edge of his bed beating out the rhythm, until Aunt Francesca implored him to stop. And even that did not help. Not one of the Montanas could begin to set the right words to the tune. Antonio looked so worried that Paolo could scarcely bear to look at him.

With so much to worry about, it was hardly surprising that Paolo and Tonino looked forward daily to being invited to the Duke’s pantomime. It was the one bright spot. But Antonio and Rinaldo went to the Palace – on foot – to deliver the special effects, and came back without a word of invitation. Christmas came. The entire Montana family went to church, in the beautiful marble-fronted Church of Sant’ Angelo, and behaved with great devotion. Usually it was only Aunt Anna and Aunt Maria who were notably religious, but now everyone felt they had something to pray for. It was only when the time came to sing the Angel of Caprona that the Montana devotion slackened. An absent-minded look came over their faces, from Old Niccolo to the smallest cousin. They sang:

“Merrily his music ringing,

See an Angel cometh singing,

Words of peace and comfort bringing

To Caprona’s city fair.

Victory that faileth never,

Friendship that no strife can sever,

Lasting strength and peace for ever,

For Caprona’s city fair.

See the Devil flee astounded!

In Caprona now is founded

Virtue strong and peace unbounded—

In Caprona’s city fair.”

Every one of them was wondering what the real words were.

They came home for the family celebrations, and there was still no word from the Duke. Then Christmas was over. New Year drew on and passed too, and the boys were forced to realise that there would be no invitation after all. Each told himself he had known the Duke was like that. They did not speak of it to one another. But they were both bitterly disappointed.

They were roused from their gloom by Lucia racing along the gallery, screaming, “Come and look at Rosa’s young man!”

“What?” said Antonio, raising his worried face from a book about the Angel of Caprona. “What? Nothing’s decided yet.”

Lucia leapt from foot to foot. She was pink with excitement. “Rosa’s decided for herself! I knew she would. Come and see!”

Led by Lucia, Antonio, Paolo, Tonino and Benvenuto raced along the gallery and down the stone stairs at the end. People and cats were streaming through the courtyard from all directions, hurrying to the room called the Saloon, beyond the dining room.

Rosa was standing near the windows, looking happy but defiant, with both hands clasped round the arm of an embarrassed-looking young man with ginger hair. A bright ring winked on Rosa’s finger. Elizabeth was with them, looking as happy as Rosa and almost as defiant. When the young man saw the family streaming through the door and crowding towards him, his face became bright pink and his hand went up to loosen his smart tie. But, in spite of that, it was plain to everyone that, underneath, the young man was as happy as Rosa. And Rosa was so happy that she seemed to shine, like the Angel over the gate. This made everyone stare, marvelling. Which, of course, made the young man more embarrassed than ever.

Old Niccolo cleared his throat. “Now look here,” he said. Then he stopped. This was Antonio’s business. He looked at Antonio.

Paolo and Tonino noticed that their father looked at their mother first. Elizabeth’s happy look seemed to reassure him a little. “Now, just who are you?” he said to the young man. “How did you meet my Rosa?”

“He was one of the contractors on the Old Bridge, Father,” said Rosa.

“And he has enormous natural talent, Antonio,” said Elizabeth, “and a beautiful singing voice.”

“All right, all right,” said Antonio. “Let the boy speak for himself, women.”