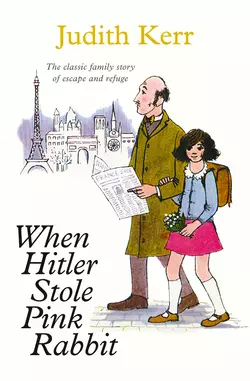

When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit

Judith Kerr

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Книги для детей

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 493.36 ₽

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 17.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Partly autobiographical, this is first of the internationally acclaimed trilogy by Judith Kerr telling the unforgettable story of a Jewish family fleeing from Germany at the start of the Second World WarSuppose your country began to change. Suppose that without your noticing, it became dangerous for some people to live in Germany any longer. Suppose you found, to your complete surprise, that your own father was one of those people.That is what happened to Anna in 1933. She was nine years old when it began, too busy with her schoolwork and toboganning to take much notice of political posters, but out of them glared the face of Adolf Hitler, the man who would soon change the whole of Europe – starting with her own small life.Anna suddenly found things moving too fast for her to understand. One day, her father was unaccountably missing. Then she herself and her brother Max were being rushed by their mother, in alarming secrecy, away from everything they knew – home and schoolmates and well-loved toys – right out of Germany…